Abstract

Phospholipase C-zeta (PLCζ) is a sperm-specific protein believed to cause Ca2+ oscillations and egg activation during mammalian fertilization. PLCζ is very similar to the somatic PLCδ1 isoform but is far more potent in mobilizing Ca2+ in eggs. To investigate how discrete protein domains contribute to Ca2+ release, we assessed the function of a series of PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeras. We examined their ability to cause Ca2+ oscillations in mouse eggs, enzymatic properties using in vitro phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) hydrolysis and their binding to PIP2 and PI(3)P with a liposome interaction assay. Most chimeras hydrolyzed PIP2 with no major differences in Ca2+ sensitivity and enzyme kinetics. Insertion of a PH domain or replacement of the PLCζ EF hands domain had no deleterious effect on Ca2+ oscillations. In contrast, replacement of either XY-linker or C2 domain of PLCζ completely abolished Ca2+ releasing activity. Notably, chimeras containing the PLCζ XY-linker bound to PIP2-containing liposomes, while chimeras containing the PLCζ C2 domain exhibited PI(3)P binding. Our data suggest that the EF hands are not solely responsible for the nanomolar Ca2+ sensitivity of PLCζ and that membrane PIP2 binding involves the C2 domain and XY-linker of PLCζ. To investigate the relationship between PLC enzymatic properties and Ca2+ oscillations in eggs, we have developed a mathematical model that incorporates Ca2+-dependent InsP3 generation by the PLC chimeras and their levels of intracellular expression. These numerical simulations can for the first time predict the empirical variability in onset and frequency of Ca2+ oscillatory activity associated with specific PLC variants.

Keywords: sperm, PLC-zeta, calcium oscillations, egg activation, fertilization

Introduction

Egg activation is the first and most crucial step that initiates embryo development after fertilization (Runft et al., 2002). Compelling evidence indicates that sperm-specific phospholipase C-zeta (PLCζ) represents the sole physiological stimulus for egg activation and subsequent embryonic development during mammalian fertilization (Cox et al., 2002; Saunders et al., 2002; Kouchi et al., 2004; Knott et al., 2005; Yoon et al., 2008). Upon sperm–egg fusion, PLCζ is delivered from the fertilizing sperm into the egg cytoplasm, triggering the Ca2+ oscillations that are responsible for causing all the major events of egg activation, such as cortical granule exocytosis to block polyspermy, resumption of second meiotic division and initiation of the first mitotic cell cycle (Nomikos et al., 2012). Sperm-delivered PLCζ catalyzes the hydrolysis of its membrane-bound phospholipid substrate, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), thus generating intracellular Ca2+ oscillations via the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) signaling pathway (Nomikos et al., 2012). The importance of PLCζ in mammalian fertilization has been further highlighted by a number of clinical reports that directly link defects or deficiencies in human PLCζ with documented cases of male infertility (Yoon et al., 2008; Heytens et al., 2009; Nomikos et al., 2011a; Kashir et al., 2012). In addition, it has been recently demonstrated that recombinant human PLCζ can phenotypically rescue failed activation of mouse eggs caused by dysfunctional PLCζ, leading to efficient blastocyst formation in a prototype of male factor infertility (Nomikos et al., 2013).

PLCζ is the smallest with the most elementary domain organization among all identified mammalian PLC isoforms. PLCζ exhibits a typical PLC domain structure consisting of four tandem EF hand domains at the N-terminus, the characteristic X and Y catalytic domains in the center followed by a single C-terminal C2 domain, all of which are common to the other PLC isoforms (β, γ, δ, ɛ and η; Nomikos et al., 2012; Swann and Lai, 2013). The XY catalytic domain is the most highly conserved region of PLC compared with other regulatory domains. The PLCζ XY domain shows a 60% sequence similarity to that of all PLC isoforms (Saunders et al., 2007). Mutagenesis of conserved active site residues within the catalytic domain of PLCζ leads to a total loss of enzymatic function and thus Ca2+ oscillation-inducing ability of PLCζ (Nomikos et al., 2012; Swann and Lai, 2013). Interestingly, mutations within the catalytic domain of PLCζ have been associated with loss of function in human sperm from an infertile male (Heytens et al., 2009; Kashir et al., 2011; Nomikos et al., 2011a, 2013). The X and Y catalytic domains are separated by an unstructured linker region. In PLCζ, a part of this linker region that is proximal to the Y domain contains a distinctive cluster of basic amino acid residues not found in the homologous region of any of the other PLC isoforms. In these somatic PLC isoforms, it has been demonstrated that the XY-linker confers potent inhibition of enzymatic activity, suggesting that this region may play a common auto-regulatory role (Hicks et al., 2008; Gresset et al., 2010). In contrast, the XY-linker of PLCζ does not confer enzymatic auto-inhibition, but conversely appears to be required for maximal enzymatic activity (Nomikos et al., 2011b).

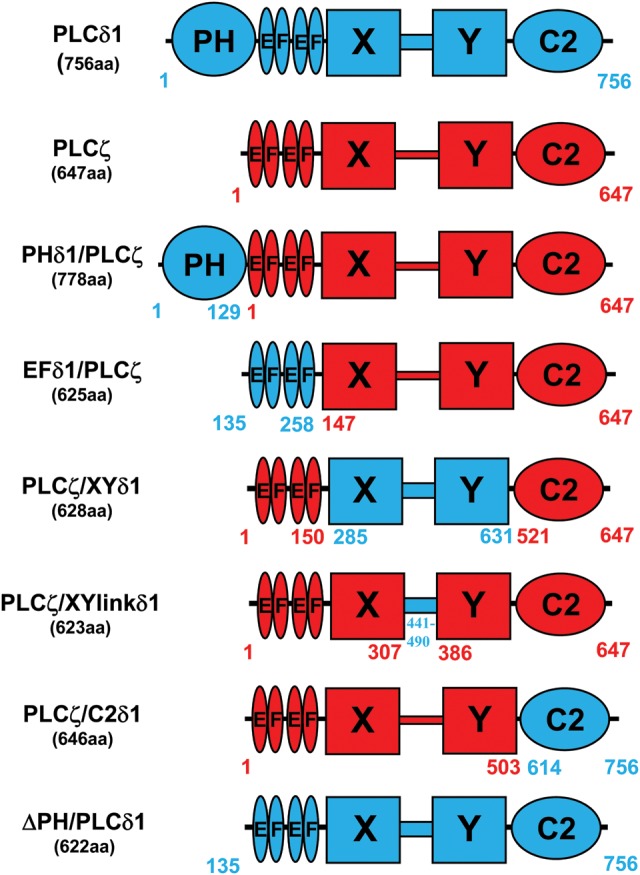

Sequence alignment analysis revealed that PLCζ has the greatest homology with PLCδ1 (47% similarity, 33% identity; Saunders et al., 2002, 2007; Nomikos et al., 2012). However, a major difference which distinguishes PLCζ from PLCδ1 and other somatic PLC isoforms is the absence of a PH domain at the N-terminus (Fig. 1). PH domains are well-defined structural modules of ∼120 amino acid residues that mediate the membrane binding of somatic PLC isoforms (Lomasney et al., 1996; Bae et al., 1998; Falasca et al., 1998; Singh and Murray, 2003). PLCδ1 binds strongly to biological membranes through its PH domain, which displays high binding affinity and specificity to the membrane-bound PLC substrate, PIP2 (Lomasney et al., 1996). The notable lack of a PH domain makes it unclear how the sperm PLCζ would interact with membranes. We have recently suggested that PLCζ may interact with its membrane-bound substrate via the electrostatic interaction of a cluster of positively charged residues that are present between the X and Y catalytic domains (i.e. the XY-linker region) with the negatively charged PIP2 (Nomikos et al., 2007, 2011c). Interestingly, we have also demonstrated that whilst PLCδ1 targets PIP2 in the plasma membrane, PLCζ appears to target intracellular PIP2 stores on distinct vesicular structures within the egg cytoplasm (Yu et al., 2012). These findings that PLCζ induces Ca2+ mobilization by hydrolyzing internal stores of PIP2 suggests the presence of a novel phosphoinositide signaling pathway during mammalian fertilization.

Figure 1.

Construction of various PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeras. Schematic linear representation of the domain structure of PLCζ (red), PLCδ1 (blue), ΔPH/PLCδ1 and their corresponding PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeras; PHδ1/PLCζ, EFδ1/PLCζ, PLCζ/XYlinkδ1, PLCζ/XYδ1 and PLCζ/C2δ1. The various amino acid lengths and respective coordinates are indicated for each construct.

Another unique feature of PLCζ compared with somatic PLC isoforms is its high Ca2+ sensitivity. PLCζ is 100-fold more sensitive to Ca2+ than PLCδ1, with an EC50 of 80 nM. This is within the range of the reported resting Ca2+ concentrations in mammalian eggs, explaining why PLCζ is active when it is introduced from the sperm cytosol into the ooplasm (Kouchi et al., 2004; Nomikos et al., 2005). The aim of this study is to investigate the specific role of PLCζ domains to help us understand the novel regulatory mechanism of this enzyme. A number of hybrid PLC proteins, i.e. ‘chimeras’ of PLCζ incorporating specific PLCδ1 structural domains were designed and constructed (Fig. 1), then their Ca2+ oscillation-inducing properties were experimentally tested relative to wild-type PLCζ by microinjection of cRNA into unfertilized mouse eggs. The various chimeric PLC constructs were then expressed as recombinant fusion proteins and their enzymatic properties were analyzed by in vitro PIP2 hydrolysis and their binding properties to PIP2 and PI(3)P were examined using a liposome binding assay. Our studies suggest that only the addition of the PH domain of PLCδ1 or replacement of EF hands of PLCζ with those of PLCδ1 could form a functional PLC enzyme within mouse eggs. Furthermore, we have developed and used a simple mathematical model to show that the Ca2+ sensitivity of these chimeras provides the basis for their ability to cause Ca2+ oscillations in eggs. In contrast, replacement of the PLCζ XY catalytic domain, XY-linker or C2 domain with the corresponding domains of PLCδ1, completely abolished the ability to trigger Ca2+ release in mouse eggs by abrogating their membrane interaction with either PIP2 or PI(3)P.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeric constructs

The PHδ1/PLCζ-luc construct was cloned into pCR3 vector by using a three step cloning strategy. The PH domain of rat PLCδ1(1–129aa) (GenBank™ accession number M20637) was amplified by PCR using Phusion polymerase (Finnzymes) and appropriate primers in order to incorporate a 5′-KpnI site and a 3′-EcoRI site and the product was cloned into the pCR3 vector. Full-length mouse PLCζ (1–647aa) was then amplified from the original cDNA clone (GenBank™ accession number AF435950) with the appropriate primers to incorporate a 5′-EcoRI site and a 3′-NotI site in which the stop codon had been removed, and the product was cloned into the pCR3-PLCδ11–129 plasmid. Finally, the firefly luciferase open reading frame was amplified from pGL2 (Promega) with primers incorporating NotI sites and the product was cloned into the NotI site of the pCR3-PLCδ11–129–PLCζ1–647 plasmid, thus creating pCR3-PLCδ11–129–PLCζ1–647-luciferase (PHδ1/PLCζ-luc; Fig. 1).

The EFδ1/PLCζ-luc and PLCζ/C2δ1-luc chimeras were cloned into the pCR3 vector by using a three step overlapping PCR reaction approach. First, primers were designed to amplify the regions of interest from mouse PLCζ and rat PLCδ1 and also to contain an overlapping sequence to link both inserts at a later stage. For EFδ1/PLCζ-luc, the EF hands of PLCδ1 (135–258aa) were amplified containing a 3′-end sequence corresponding to the 5′-end of ΔEF/PLCζ (147–647aa), while ΔEF/PLCζ was amplified containing the 5′-end sequence designed to overlap the 3′-end sequence of the amplified EF hands (Fig. 1).

For PLCζ/C2δ1-luc, the C2 domain of PLCδ1 (614–756aa) was amplified to contain the 5′-end sequence of the 3′-end sequence of PLCζ/ΔC2 (1–503aa); and PLCζ/ΔC2 sequence was amplified containing the 3′-end sequence designed to overlap the 5′-end sequence of the amplified C2 domain. Once these constructs had been amplified, an overlapping reaction was carried out in order to link the corresponding inserts and produce the EFδ1/PLCζ and PLCζ/C2δ1 (Fig. 1). These were cloned into pCRXL TOPO and then subcloned into the pCR3 vector. Luciferase was then cloned into pCR3-EFδ1/PLCζ and pCR3-PLCζ/C2δ1 plasmids in the same fashion as described above, resulting in the same short linker sequence CAAA between the PLCζ and luciferase. This strategy enabled creation of pCR3-PLCδ1135–258–PLCζ147–647-luciferase (EFδ1/PLCζ-luc) and pCR3-PLCζ1-503–PLCδ1614-756-luciferase (PLCζ/C2δ1).

The PLCζ/XYδ1-luc and PLCζ/XYlinkδ1-luc constructs were cloned into pCR3 vector by using a four step cloning strategy. For PLCζ/XYδ1-luc, PLCζ(1–150aa), was amplified by PCR with primers to incorporate a 5′-KpnI site and a 3′-EcoRI site and then cloned into the pCR3 vector. The XY domain of PLCδ1(285–631aa) was then amplified from the original cDNA clone with primers to incorporate a 5′-EcoRI site and a 3′-EcoRV site and cloned into the pCR3-PLCζ1-150 plasmid. Then, PLCζC2 domain (521–647aa) was amplified with appropriate primers to incorporate a 5′-EcoRV site and a 3′-NotI site and cloned into the pCR3-PLCζ1–150-PLCδ1285–631 plasmid. Finally, luciferase was amplified from pGL2 with primers incorporating NotI sites and the product was cloned into the NotI site of the pCR3-PLCζ1–150–PLCδ1285–631–PLCζ521–647 plasmid to create PLCζ/XYδ1 (Fig. 1). The same strategy was followed for the PLCζ/XYlinkδ1-luc construct but the corresponding constructs that sequentially amplified and cloned using the same restriction enzymes were PLCζ(1–307aa), PLCδ1(441–490aa) and PLCζ(386–647aa), respectively, thus creating PLCζ/XYlinkδ1.

The ΔPH/PLCδ1-luc construct was cloned into pCR3 vector by using a two-step cloning strategy. PLCδ1(135–756aa) was amplified using the appropriate primers to incorporate a 5′-EcoRV site and a 3′-NotI site in which the stop codon had been removed and cloned into the pCR3 vector. Then luciferase was amplified as above and the product was cloned into the NotI site of the pCR3-PLCδ1135–756 plasmid to generate ΔPH/PLCδ1 (Fig. 1).

All the above chimeric constructs, except without the C-terminus luciferase portion, were amplified from the pCR3 vector with the appropriate primers to incorporate a 5′-SalI site and a 3′-NotI site and the product was cloned into the pETMM60 vector to enable bacterial protein expression. Each of the above expression vector constructs was confirmed by dideoxynucleotide sequencing (Prism Big Dye kit; ABI Prism® 3100 Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK).

cRNA synthesis

Following linearization of wild-type and chimeric PLC plasmids, cRNA was synthesized using the mMessage Machine T7 kit (Ambion) and then was polyadenylated using the poly(A) tailing kit (Ambion), as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Preparation and handling of gametes

Experiments were carried out with mouse eggs in Hepes-buffered media (H-KSOM) as previously described (Nomikos et al., 2005, 2011b, c). All compounds were from Sigma unless stated otherwise. Female mice were superovulated and eggs were collected 13.5–14.5 h after injection of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) and maintained in droplets of M2 media (Sigma) or H-KSOM under mineral oil at 37°C. Microinjection of the eggs was carried out 14.5–15.5 h after the hormone injection. Eggs were obtained from mice using standard procedures that have been approved by the UK Home Office.

Microinjection and measurement of intracellular Ca2+ and luciferase expression

Mouse eggs were washed in M2 media and microinjected with cRNA diluted in injection buffer (120 mM KCl, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4). The volume injected was estimated from the diameter of cytoplasmic displacement caused by the bolus injection. All injections were 3–5% of the egg volume. Eggs were microinjected with the appropriate cRNA, mixed with an equal volume of 1 mM Oregon Green BAPTA dextran (Molecular Probes) in the injection buffer. Eggs were then maintained in H-KSOM with 100 μM luciferin and imaged on a Nikon TE2000 or Zeiss Axiovert 100 microscope equipped with a cooled intensified CCD camera (Photek Ltd, UK). Ca2+ was monitored in these eggs for 4 h after injection by measuring the fluorescence of Oregon Green BAPTA dextran (OGBD) with low level excitation light from a halogen lamp. The OGBD fluorescence was collected intermittently (10 s every 20 s), and the light measured in the intervals between fluorescence excitation taken as the luminescence due to luciferase. Hence we could monitor both cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration changes and recombinant luciferase protein luminescence over the same time period in eggs as they expressed each of the various PLC-luc constructs. The fluorescence signals were typically 100 times greater than the luminescence signals. Ca2+ measurements for an egg were further analyzed only if the same egg was also luminescent during the experiment. The luminescence from eggs was converted into an amount of luciferase using a standard calibration plot that was generated by placing eggs in a luminometer that had been previously calibrated by microinjection with known amounts of luciferase protein (Sigma) (Nomikos et al., 2005; 2011b, c; Swann et al., 2009).

Protein expression and purification

For bacterial expression of NusA-6His-tagged PLC chimera fusion proteins, Escherichia coli [Rosetta (DE3) cells, Novagen] was transformed with the appropriate pETMM60-PLC plasmid construct and cultured at 37°C until the A600 reached 0.6, and then protein expression was induced for 18 h at 16°C with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (Promega). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6000g for 10 min, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4·7H2O, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 2 mM dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science), and then sonicated four times for 15 s on ice. After 15 min of centrifugation at 15 000g, 4°C, soluble 6xHis-tagged protein was purified by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) and eluted with 250 mM imidazole. Eluted proteins were dialyzed overnight (Pierce; SnakeSkin 10 000 molecular weight cutoff) at 4°C against 4 l of PBS, and concentrated with centrifugal concentrators (Sartorius; 10 000 MWCO).

Assay of PLC activity

PIP2 hydrolytic activity of recombinant wild-type and chimeric PLC proteins was assayed as described elsewhere (Nomikos et al., 2005; 2011b, c). The final volume of the assay mixture was 50 μl containing 100 mM NaCl, 0.4% sodium cholate (w/v), 2 mM CaCl2, 4 mM EGTA, 20 μg of bovine serum albumin, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 6.8. The final concentration of PIP2 in the reaction mixture was 220 μM, containing 0.05 μCi of [3H]PIP2. The assay conditions were optimized for linearity, requiring a 10-min incubation of 20 pmol of PLC protein sample at 25°C. Reactions were stopped by addition of 0.25 ml of chloroform/methanol/concentrated HCl (100:100:0.6 v/v) followed by 0.075 ml of concentrated HCl. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 2000g for 2 min, and then 0.2 ml of the upper aqueous phase was removed and added to 10 ml of Optiphase ‘Hisafe 3’ scintillation mixture (Wallac), and the radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrofluorimetry (Packard Tri-Carb 2100TR). In assays to determine dependence on PIP2 concentration, 0.05 μCi of [3H]PIP2 was admixed with cold PIP2 to give the appropriate final concentration. In assays examining the Ca2+ sensitivity, Ca2+ buffers were prepared by EGTA/CaCl2 admixture, as previously described (Nomikos et al., 2005).

Liposome preparation and binding assay

Unilamellar liposomes were prepared as previously described (Nomikos et al., 2011c) by the extrusion method using a laboratory extruder (LiposoFast-Pneumatic, Avestin Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada) with lipids purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL). In a typical experiment requiring a 2 ml dispersion of liposomes, 0.038 mmol (1910–3 M) of 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 0.019 mmol (9.5 × 10–3 M) of cholesterol (molar ratio DPPC:CHOL 2:1), 0.0095 mmol (4.8 × 10–3 M) 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DMPE) (molar ratio DPPC:DMPE 4:1) and 1 or 5% of total lipids [16:50:38] phosphatidylcholine/phosphatidylinositol (PCPI) were dissolved in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) for the formation of lipid films. The film was hydrated with 2 ml of PBS and the resultant suspension was extruded through two-stacked polycarbonate filters of 100 nm pore size. Twenty-five cycles of extrusion were applied at 50°C. For the control experiments, unilamellar liposomes without PCPI were prepared in an analogous manner. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was employed to determine the size of the liposomes, which used a light scattering apparatus (AXIOS-150/EX, Triton Hellas) with a 30 mW laser source and an Avalanche photodiode detector set at a 900 angle. DLS measurements of the extruded lipid preparation showed a narrow monomodal size distribution with average liposome diameter of 100 nm and a polydispersity index of 0.20–0.25. For protein binding studies the liposomes (100 µg of 4:2:1 DMPC:CHOL:DMPE) containing 0–1% PI(4,5)P2 or 5% PI(3)P were incubated with 1 µg of recombinant protein for 30 min at RT and centrifuged for 6 h at 4°C. The supernatant and pellet were then analyzed by SDS–PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining as previously described (Nomikos et al., 2011c).

SDS–PAGE and western blotting

Recombinant proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE as previously described (Nomikos et al., 2011b,c). Separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore) using a semi-dry transfer system (Trans-Blot SD; Bio-Rad) in buffer (48 mM Tris, 39 mM glycine, 0.0375% SDS) at 22 V for 4 h (Mackrill et al., 1997). The membrane incubated overnight at 4°C in Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) containing 5% non-fat milk powder, and probed with anti-NusA monoclonal antibody (1:25 000 dilution). Detection of horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody was achieved using enhanced chemiluminescence detection (ECL; Amersham Biosciences).

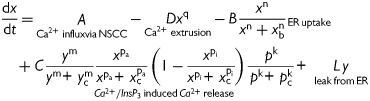

Mathematical modeling of Ca2+ dynamics

The mathematical model (see Appendix for details) consists of a system of three differential equations, which account for time-dependent fluctuations in the inter-dependent variables of InsP3 concentration (p), concentration of free cytosolic Ca2+ (x) and Ca2+ sequestered in the endoplasmic reticulum (y). Equations describing the balance of free and sequestered Ca2+ have been adapted from a previously developed mathematical model used in the study of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) from intracellular stores, which was shown to accurately reproduce experimental observations under various pharmacological conditions (Parthimos et al., 1999). A variant model was developed more recently to study differences between CICR and InsP3-induced Ca2+ release (IICR) from intracellular stores (Parthimos et al., 2007). The differential equation describing fluctuations in InsP3 concentration assumes a general form with Ca2+-dependent InsP3 production upon PIP2 hydrolysis by the PLC isoforms and a decay term proportional to current InsP3 concentrations. Similar approaches have been previously employed in modeling InsP3 production in a variety of somatic cells including eggs (Atri et al., 1993; Politi et al., 2006). Numerical simulations were run in parallel on code written in C++ and MATLAB software (Mathworks).

Results

Ca2+ oscillation-inducing activity of PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeras expressed in unfertilized mouse eggs

To investigate the regulatory role of the distinct PLCζ domains on the in vivo Ca2+ oscillation-inducing activity and the in vitro biochemical properties of this enzyme, a series of chimeric constructs of PLCζ with various PLCδ1 domains were designed. To generate these chimeric plasmids, PLCζ served as the template and then discrete domains of PLCζ were replaced by the corresponding domain of PLCδ1 (Fig. 1). Five chimeric constructs were generated; PLCζ containing either the N-terminal PH domain (PHδ1/PLCζ), the EF hands domain (EFδ1/PLCζ), the XY catalytic domain (PLCζ/XYδ1), the XY-linker (PLCζ/XYlinkδ1) or the C2 domain (PLCζ/C2δ1) of PLCδ1 (Fig. 1). In addition to the wild-type PLCζ and PLCδ1 constructs that served as controls for our studies, a further control construct generated was PLCδ1 lacking the PH domain (ΔPH/PLCδ1). This construct provides a domain organization precisely matching with PLCζ. In order to test the ability of these eight constructs to trigger Ca2+ oscillations and to verify their expression upon microinjection of the corresponding cRNA into mouse eggs, each construct was tagged at the C-terminus with luciferase. This strategy enables real-time monitoring of relative recombinant protein expression in live cells by luminescence quantification (Swann et al., 2009; Nomikos et al., 2013).

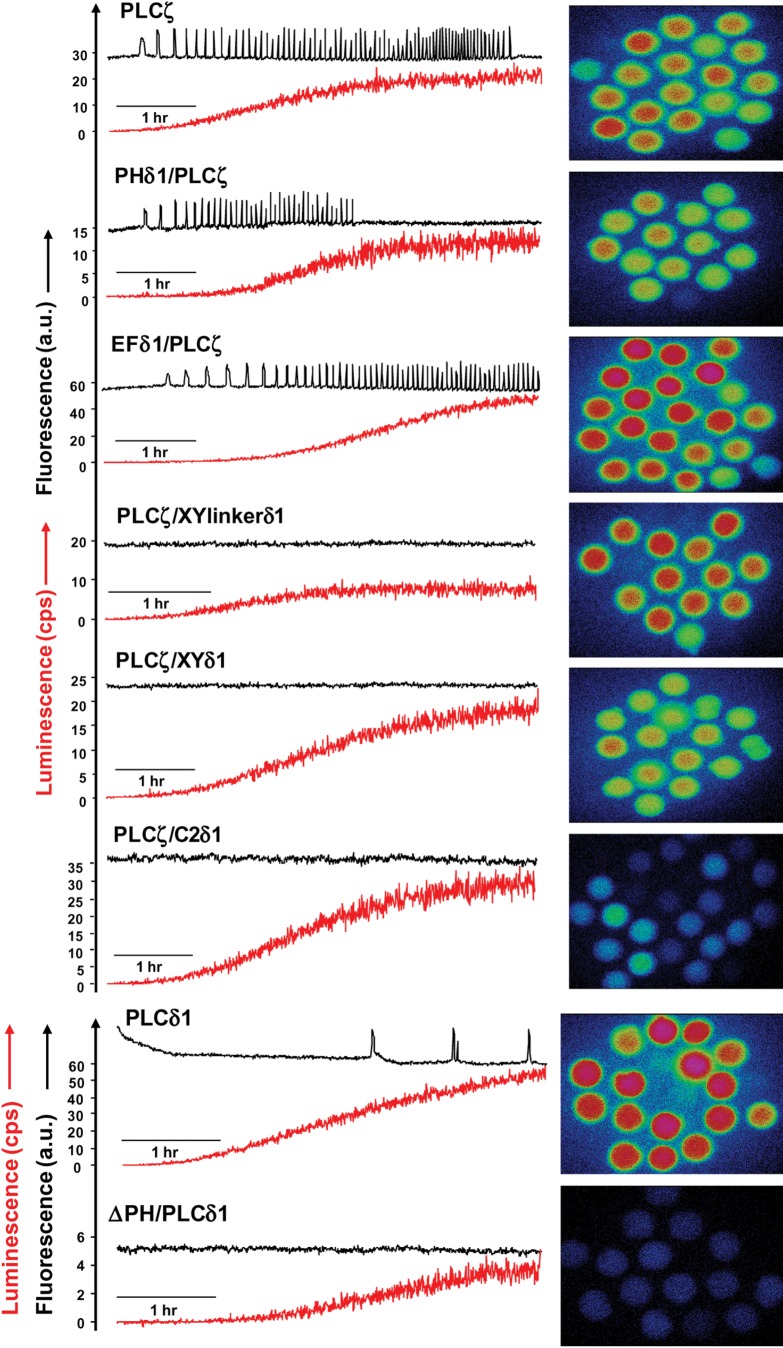

Figure 2 and Table I summarize the results of the wild-type PLCζ, PLCδ1, ΔPH/PLCδ1 and chimeric PLCζ/PLCδ1-luciferase cRNA microinjection experiments. Consistent with our previous studies, prominent Ca2+ oscillations (∼28 spikes/2 h) were observed in the wild-type PLCζ cRNA-injected eggs, with the first Ca2+ spike appearing at a relative luminescence value (‘protein expression level’) of 0.53 cps (Fig. 2, Table I). Microinjection of cRNA encoding PHδ1/PLCζ and EFδ1/PLCζ chimeras also triggered Ca2+ oscillations in mouse eggs (∼21 and ∼17 spikes/2 h, respectively) exhibiting a slightly lower frequency relative to wild-type PLCζ, with the first Ca2+ spike detected at a luminescence of 0.21 and 0.50 cps, respectively. In contrast, microinjection of the PLCζ/XYδ1, PLCζ/XYlinkδ1, PLCζ/C2δ1 chimeras or ΔPH/PLCδ1 failed to cause any Ca2+ release, even after relatively high levels of protein expression in mouse eggs (Fig. 2, Table I). Microinjection of cRNA corresponding to wild-type PLCδ1 induced very-low-frequency Ca2+ oscillations (∼2 spikes/2 h) that commenced only after PLCδ1 protein expression to 20.3 cps was achieved. This is consistent with our previous observations of injected cRNA encoding wild-type PLCδ1 into mouse eggs (Nomikos et al., 2011b). These data indicate that substitution of the XY catalytic domain, XY-linker or C2 domain of PLCζ with the corresponding domain of PLCδ1 completely abolishes Ca2+ oscillation-inducing activity in mouse eggs. In addition, deletion of the PH domain alone from PLCδ1 to give it a PLCζ-like structural organization does not confer the truncated PLCδ1 isoform with oscillogenic activity.

Figure 2.

Expression of PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeras in unfertilized mouse eggs. Fluorescence and luminescence recordings reporting the Ca2+ changes (black traces; Ca2+) and luciferase expression [red traces; Lum, in counts per second (cps)], respectively, in unfertilized mouse eggs following microinjection of cRNA encoding luciferase-tagged PLCζ, PHδ1/PLCζ, EFδ1/PLCζ, PLCζ/XYlinkδ1, PLCζ/XYδ1, PLCζ/C2δ1, PLCδ1 and ΔPH/PLCδ1 proteins. Panels on the right display representative integrated luminescence image of individual mouse eggs following cRNA microinjection of each PLC construct (see Table I).

Table I.

Properties of PLCζ-luciferase chimeras expressed in mouse eggs.

| PLCζ-luciferase injected | Number of eggs | Ca2+ oscillations (spikes/2 h) | Peak luminescence (cps) | Luminescence at first spike (cps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLCζ | 17 | 27.9 ± 1.20 | 19.1 ± 1.20 | 0.53 ± 0.03 |

| PHδ1/PLCζ | 13 | 20.7 ± 1.10 | 11.4 ± 0.50 | 0.21 ± 0.04 |

| EFδ1/PLCζ | 20 | 16.5 ± 1.20 | 45.3 ± 2.50 | 0.50 ± 0.11 |

| PLCζ/XYlinkδ1 | 26 | 0 | 6.6 ± 0.46 | 0 |

| PLCζ/XYδ1 | 21 | 0 | 18.5 ± 1.00 | 0 |

| PLCζ/C2δ1 | 19 | 0 | 16.4 ± 1.00 | 0 |

| PLCδ1 | 17 | 1.8 ± 0.12 | 45.0 ± 1.76 | 20.3 ± 0.30 |

| ΔPH/PLCδ1 | 14 | 0 | 4.0 ± 0.44 | 0 |

Ca2+ oscillation-inducing activity (Ca2+ spike number in 2 h) and luciferase luminescence levels (peak luminescence; luminescence at first spike) are summarized for mouse eggs microinjected with each of the PLC-luciferase constructs; PLCζ, PHδ1/PLCζ, EFδ1/PLCζ, PLCζ/XYlinkδ1, PLCζ/XYδ1, PLCζ/C2δ1, PLCδ1 and ΔPH/PLCδ1 (see Figs 1 and 2). The data are expressed to two significant figures, with means ± SEM.

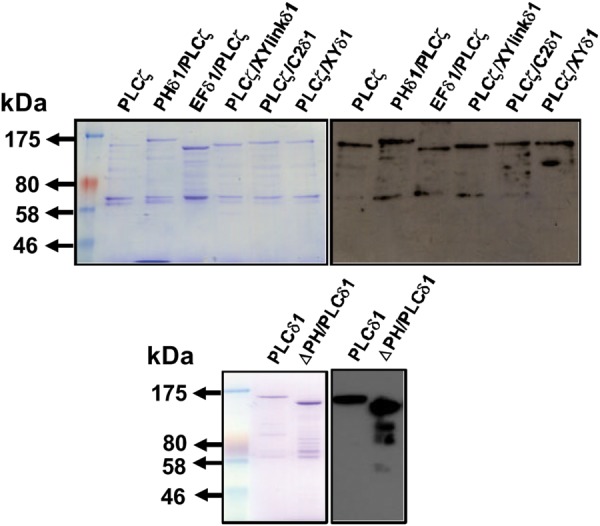

Expression and enzymatic characterization of PLCζ chimeras

PLCδ1, ΔPH/PLCδ1 and all the chimeric PLCζ constructs were subcloned into the pETMM60 vector and purified as NusA-6His-tagged fusion proteins. We have recently demonstrated that NusA is the most efficient fusion partner for PLCζ, significantly increasing the expression of soluble PLCζ protein in a bacterial host, E. coli, as well as enhancing the enzymatic stability of the purified protein (Nomikos et al., 2013). As described in ‘Experimental Procedures’, optimal protein production for all NusA-tagged PLCζ/PLCδ1 constructs required induction of protein expression with 0.1 mM IPTG for 18 h at 16°C. Following induced expression in E. coli and isolation by affinity chromatography, the purified PLC protein samples were characterized. Figure 3 shows wild-type NusA-tagged PLCζ, PLCδ1, ΔPH/PLCδ1 and the five PLCζ chimeras analyzed by SDS–PAGE (left panels) and immunoblot detection with an anti-NusA monoclonal antibody (right panels). The major protein band with mobility corresponding to the predicted molecular mass for each construct was present for all the samples and these major bands were also confirmed by the anti-NusA antibody after immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3). For some constructs, fainter low molecular weight bands could be observed, which were also detected by the anti-NusA antibody, and are probably the result of protease degradation occurring during the stages of protein isolation.

Figure 3.

Expression of recombinant NusA-tagged PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeric proteins. Affinity-purified, NusA-6His-PLC fusion proteins (1 μg) were analyzed by 7% SDS–PAGE followed by either Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (left-hand side panels) or immunoblot analysis using the anti-NusA monoclonal antibody at 1:25 000 dilution (right-hand side panels).

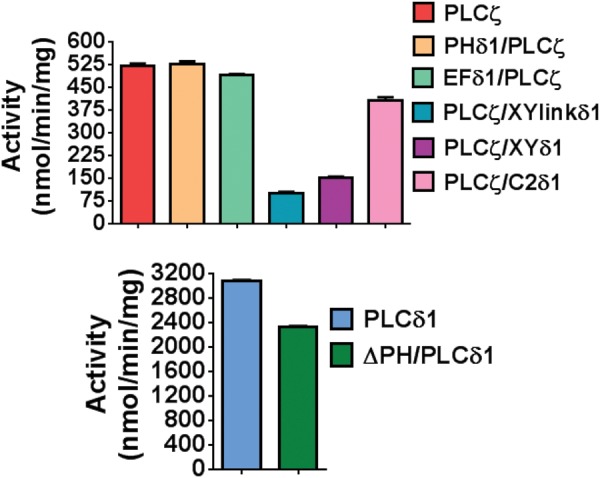

The specific PIP2 hydrolytic enzyme activity for each recombinant protein was determined using the standard in vitro [3H]PIP2 hydrolysis assay (Nomikos et al., 2005). The histogram of Fig. 4 and Table II summarizes the enzyme-specific activity values obtained for each protein and reveals that the wild-type PLCζ, PHδ1/PLCζ and EFδ1/PLCζ chimeras exhibited similar enzymatic activities, while PLCζ/C2δ1 chimera showed a slightly reduced enzymatic activity (∼20%) compared with wild-type PLCζ protein. Interestingly, the PLCζ/XYlinkδ1 and PLCζ/XYδ1 chimeric proteins showed a dramatic reduction in their enzymatic activities, retaining only ∼20 and ∼30% activity of wild-type PLCζ protein, respectively (Fig. 4). Finally, the ΔPH/PLCδ1-truncated construct retained 75% of wild-type PLCδ1 activity (2325 ± 25 versus 3070 ± 38 nmol/min/mg) but notably displayed a ∼4.5-fold higher in vitro enzymatic activity compared with wild-type PLCζ (2325 ± 25 versus 521 ± 11 nmol/min/mg).

Figure 4.

Enzyme activity of PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeras. PIP2 hydrolysis enzyme activities of the purified NusA-6His-PLC fusion proteins (20 pmol) were determined in vitro with the standard [3H]PIP2 cleavage assay, n = 3 ± SEM, using three different preparations of recombinant protein and with each experiment performed in duplicate. In control experiments with NusA protein alone, there was no specific PIP2 hydrolysis activity observed (data not shown).

Table II.

In vitro enzymatic properties of NusA-tagged PLCζ chimeras.

| NusA-fusion PLC protein | PIP2 hydrolysis enzyme activity (nmol min−1 mg−1) | Km (µM) | Ca2+-dependence EC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLCζ | 521 ± 11 | 100 | 68 |

| PHδ1/PLCζ | 528 ± 21 | 96 | 84 |

| EFδ1/PLCζ | 493 ± 12 | 120 | 690 |

| PLCζ/XYlinkδ1 | 100 ± 8 | 3602 | 490 |

| PLCζ/XYδ1 | 152 ± 13 | 2431 | 538 |

| PLCζ/C2δ1 | 409 ± 24 | 106 | 105 |

| PLCδ1 | 3070 ± 38 | 76 | 4200 |

| ΔPH/PLCδ1 | 2325 ± 25 | 747 | 2000 |

To compare the enzyme kinetics of wild-type PLCζ and the PLCζ chimeras, as well as of wild-type PLCδ1 and ΔPH/PLCδ1 recombinant proteins, the Michaelis–Menten constant, Km for the PIP2 substrate was calculated (Table II). The Km value obtained for wild-type PLCζ (100 µM), PHδ1/PLCζ (96 µM), EFδ1/PLCζ (120 µM) and PLCζ/C2δ1 (106 µM) chimeras were nearly identical. In contrast, the Km for PLCζ/XYlinkδ1 and PLCζ/XYδ1 was ∼36-fold (3602 μM) and ∼24-fold (2431 μM) higher than that of wild-type PLCζ, respectively (Table II). These results indicate that replacement of the entire XY catalytic domain or the short XY-linker of PLCζ with that of PLCδ1 dramatically reduces the in vitro affinity of PLCζ for PIP2. In addition, the Km for ΔPH/PLCδ1 protein (746 μM) was ∼10-fold higher than that of wild-type PLCδ1 (76 μM), indicating that absence of the N-terminal PH domain reduces the in vitro affinity of PLCδ1 for its substrate, PIP2.

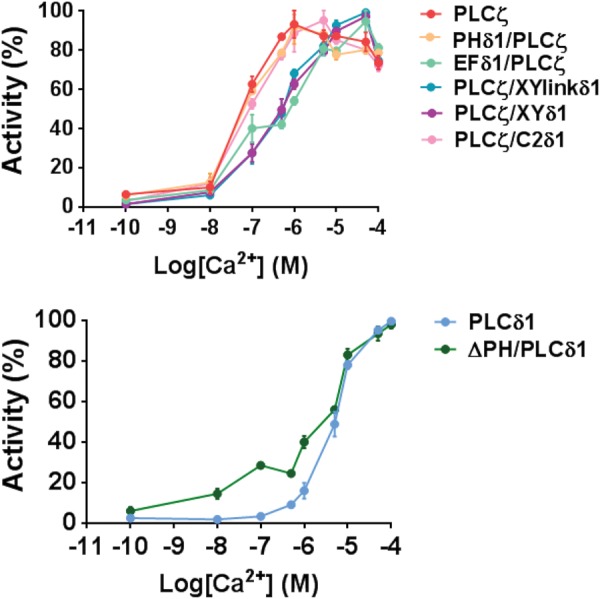

To investigate the effect of these domain replacements on the Ca2+ sensitivity of PLCζ enzyme activity, we assessed the ability of wild-type PLCζ and chimeric PLCζ fusion proteins to hydrolyze [3H]PIP2 at different Ca2+ concentrations ranging from 0.1 nM to 0.1 mM (Fig. 5). The resulting EC50 value obtained for wild-type PLCζ (68 nM), PHδ1/PLCζ (84 nM) and PLCζ/C2δ1 (105 nM) were all very similar (Table II). Replacement of EF hands of PLCζ with those from PLCδ1 increased the EC50 value ∼10-fold (690 nM), while replacement of XY domain or XY-linker increased the EC50 ∼8 and ∼7-fold, respectively (538 and 490 nM; Fig. 5, Table II). Interestingly, deletion of the PH domain from PLCδ1 increased the sensitivity of this enzyme to Ca2+, reducing the EC50 value from 4200 nM (PLCδ1) to 2000 nM (ΔPH/PLCδ1).

Figure 5.

Ca2+-dependent enzyme activity of PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeras. Effect of varying [Ca2+] on the normalized activity of NusA-6His-tagged, wild-type PLCζ, PLCδ1, ΔPH/PLCδ1 and PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeric fusion proteins; PHδ1/PLCζ, EFδ1/PLCζ, PLCζ/XYlinkδ1, PLCζ/XYδ1 and PLCζ/C2δ1. For these assays n = 2 ± SEM, using three different batches of recombinant proteins and with each experiment performed in duplicate. Color used for each construct matches the corresponding construct in Fig. 4.

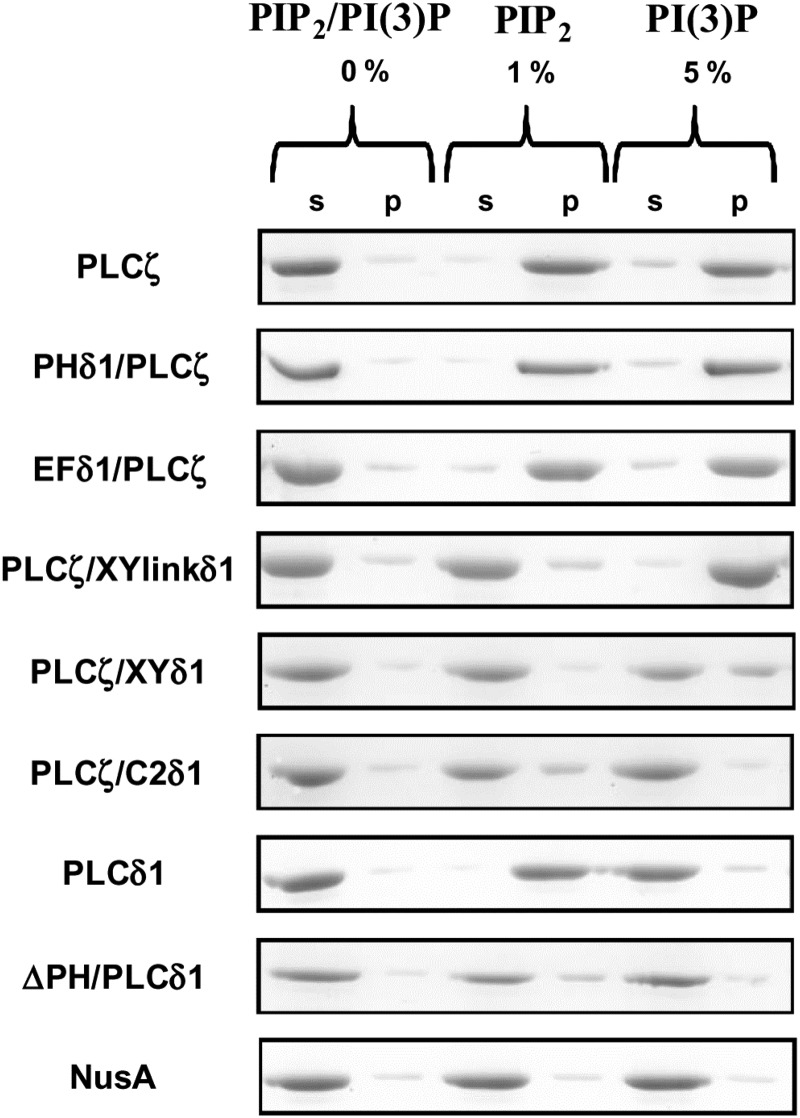

Binding of PLCζ chimeras to PIP2 and PI(3)P

To examine the binding properties of wild-type PLCζ and chimeras to PIP2 and PI(3)P, we employed a liposome binding assay. For this study, we made unilamellar liposomes composed of PC:CHOL:PE (4:2:1) with incorporation of either 0, 1% PIP2 or 5% PI(3)P. In order to diminish any non-specific protein binding to highly charged lipids, the liposome binding assays were performed in the presence of a near-physiological concentration of MgCl2 (0.5 mM). For the binding assay, wild-type PLCδ1 and PLCζ provided the positive controls, while the NusA moiety was the negative control. NusA did not exhibit any specific liposome binding in the absence or presence of PIP2 and PI(3)P, whereas PLCζ displayed robust binding only to liposomes containing either 1% PIP2 or 5% PI(3)P (Fig. 6). As expected, PLCδ1 bound strongly to liposomes containing 1% PIP2 and remained in the supernatant in the absence of PIP2 or in the presence of PI(3)P, while deletion of its PH domain led to loss of the binding to liposomes containing 1% PIP2. The binding properties of PHδ1/PLCζ and EFδ1/PLCζ chimeras were very similar to wild-type PLCζ, with binding strongly only to liposomes containing either 1% PIP2 or 5% PI(3)P. For PLCζ/XYlinkδ1, the majority (∼90%) of this protein was detected in the supernatant of liposomes containing 0 or 1% PIP2, while showing strong binding to liposomes containing 5% PI(3)P (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the PLCζ/XYδ1 chimera similar to PLCζ/XYlinkδ1, did not bind to liposomes containing 0 or 1% PIP2 but its binding to liposomes containing PI(3)P was much reduced (∼40%). Finally, PLCζ/C2δ1 did not bind to liposomes containing 0 or 5% PI(3)P, while showing a much reduced binding level (∼25%) to liposomes containing 1% PIP2. These data suggest that the XY-linker may provide the major contribution to the physiological interaction of PLCζ with PIP2, while interaction of PLCζ with PI(3)P in liposomes requires the C2 domain.

Figure 6.

In vitro binding of wild-type PLCζ, PLCδ1, ΔPH/PLCδ1 and PLCζ/PLCδ1 chimeras to PIP2 and PI(3)P. Liposome ‘pull-down’ assay of various PLC constructs. Unilamellar liposomes comprising PtdCho:CHOL:PtdEtn (4:2:1) with or without 1% PIP2 or 5% PI(3)P were incubated in the presence of 0.5 mM Mg2+ with the various purified PLC recombinant proteins. Following centrifugation, both the supernatant (s) and liposome pellet (p) were subjected to SDS–PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining.

Computational model of Ca2+ oscillations

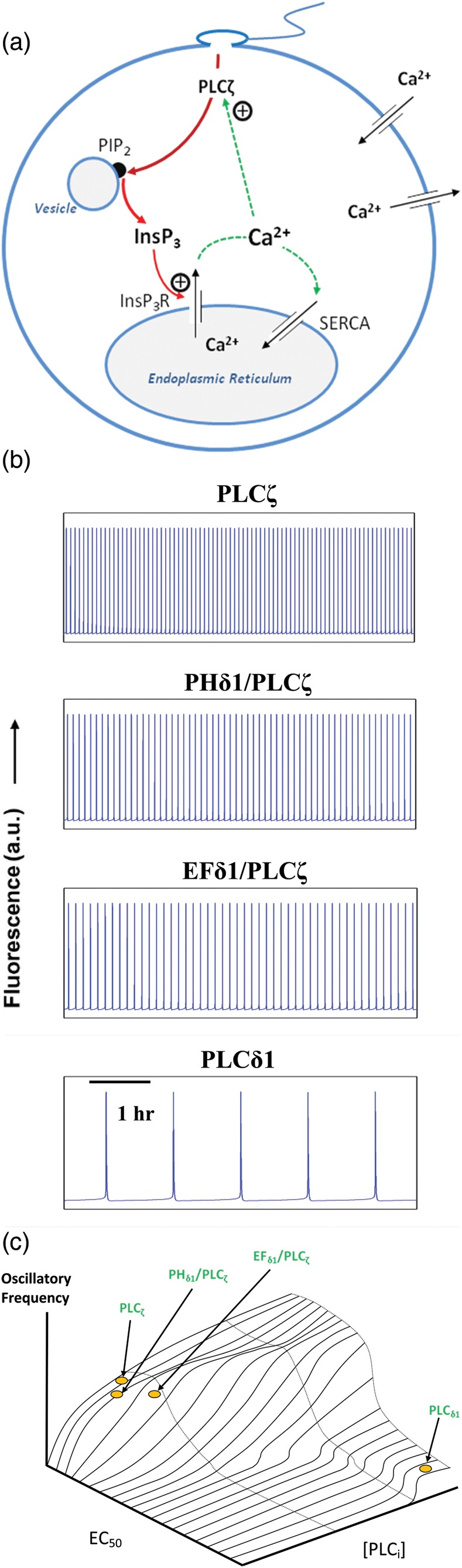

A simple model of Ca2+ oscillations in eggs was constructed based upon previous generic models to simulate Ca2+ dynamics (Parthimos et al., 1999; Politi et al., 2006). The findings summarized in Tables I and II and Figs 2 and 5 confirm the well-described link between levels of the various PLC constructs, InsP3 expression and the cytosolic Ca2+ handling apparatus in mammalian eggs. A schematic representation of the basic model beginning with InsP3 production due to Ca2+-dependent hydrolysis of PIP2 by a PLC isoform, to the InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum is illustrated in Fig. 7a. Individual steps have been incorporated in the modeling scheme outlined in the Appendix (Equations 1–3). The aim is to establish a quantifiable relationship between the experimentally measured parameters describing InsP3 production and the observed oscillatory Ca2+ frequency. Simulations for the four chimeras that induce oscillatory activity in Fig. 2 are presented in Fig. 7b, with frequencies closely matching the values calculated in Table I. This was achieved purely by assigning the corresponding Ca2+ activation constants (the EC50) from Table II to each of the PLC chimeras. The experimental findings (summarized in Table I) demonstrate that the level of expression of each PLC isoform/chimera required for the onset of oscillatory was variable. Notably, PLCδ1 required ∼40-fold higher levels of expression to initiate low-frequency oscillations. In order to establish a generalized theoretical prediction, we simulated egg Ca2+ oscillations for a broad range of Ca2+ sensitivities (EC50S) and PLC expression values. The resulting response plots are presented in Fig. 7c and provide a global view of the Ca2+ dynamics. These results support the experimental observation that an increased EC50 is associated with lower oscillatory frequency and a delayed onset of Ca2+ oscillations. Note that the onset of PLCδ1-mediated oscillatory activity is subject to a relatively sharp threshold and associated with a prolonged steady state of low-frequency oscillations.

Figure 7.

Mechanisms of PLCζ, InsP3 and Ca2+ regulation in the egg cytosol during mammalian fertilization and associated numerical simulations of intracellular Ca2+ oscillations. (a) Simplified schematic to illustrate the interactions occurring between the PLCζ, InsP3 and Ca2+ pathways within the egg cytosol. Following sperm–egg fusion, PLCζ diffuses from the sperm head into the egg cytosol and targets a distinct vesicular PIP2-containing endomembrane. PLCζ-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2 produces InsP3 which stimulates Ca2+ release through binding to endoplasmic reticulum InsP3 receptors. This mode of InsP3-stimulated Ca2+ release forms the basis of the intracellular Ca2+ oscillations at fertilization, which ultimately lead to egg activation and embryo development. The model allows for Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ extrusion across the plasma membrane. (b) Numerical simulations of Ca2+ oscillations in the egg cytosol closely match experimental traces presented in Fig. 2 for corresponding parametric conditions. Individual simulations of oscillatory activity associated with PLCζ, PHδ1/PLCζ, EFδ1/PLCζ and PLCδ1 are generated with the following pairs of PLC and EC50 (xp) values: 0.88 μM s−1/0.068 μM, 0.35 μM s−1/0.084 μM, 0.83 μM s−1/0.69 μM and 33.8 μM s−1/4.2 μM, in agreement with experimental values presented in Tables I and II. (c) Contour plot mapping the oscillatory frequency of Ca2+ oscillations throughout the physiological range of PLC sensitivity to Ca2+ (EC50) and PLC protein expression levels. The operating points of PLCζ, PHδ1/PLCζ, EFδ1/PLCζ and PLCδ1 proteins are indicated by circles/arrows. The nanomolar Ca2+ sensitivity of PLCζ enables the enzyme to be active at resting Ca2+ levels (nM). In contrast, the relatively low, micromolar Ca2+ sensitivity of PLCδ1 leads to low-frequency oscillations even at much higher protein expression levels.

Most previously developed mathematical models of egg fertilization have focused on specific aspects of the process, such as modes of cell activation and intracellular wave formation (Atri et al., 1993), the relation of Ca2+ dynamics and various biochemical pathways, e.g. involving growth factors or calmodulin-dependent kinase II activation (Diaz et al., 2005; Dupont et al., 2010), and modeling of InsP3 receptors as multi-state processes or non-uniformly distributed units (Ullah et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2008). In this study, we have maintained a minimal approach since our overall aim was to elucidate causal links between PLC-mediated InsP3 generation and egg Ca2+ oscillations. This approach was, nevertheless, able to closely replicate the experimental findings for the onset and frequency of Ca2+ oscillations during fertilization. The activation contour presented in Fig. 7c reveals an apparent resonance at low EC50 values, which is evident as a prolonged hump in the plot. This band of heightened activity may account for the apparent increased sensitivity of the PHδ1/PLCζ chimera observed experimentally.

Our modeling approach assumed a purely concentration-dependent InsP3 decay. However, InsP3 degradation occurs via a phosphorylation pathway which is [Ca2+] independent and a dephosphorylation pathway which is stimulated by Ca2+. Employing both these components in Equation (3) produced subtle variations in the oscillatory amplitude (simulations not shown) but did not provide any further advantage over the simple decay term employed in this study.

Discussion

Numerous studies support the notion that sperm PLCζ is the sole physiological agent responsible for mammalian oocyte activation, by initiating Ca2+ release from intracellular stores via the activation of the IP3/receptor signaling pathway (Ito et al., 2011; Nomikos et al., 2012; Swann and Lai, 2013). Sperm-specific PLCζ is the smallest known PLC, with the simplest domain organization of all PLC isoforms identified to date. Thus, PLCζ could be considered a prototypic mammalian PLC isoform, which would also be consistent with the pivotal physiological role that this gamete-derived PLCζ is proposed to play in the first steps of mammalian fertilization. Notably, our recent studies suggest that sperm PLCζ has a unique regulatory mechanism that is highly distinctive from the regulatory mechanism that operates in the other mammalian somatic cell PLC isoforms (Phillips et al., 2011; Nomikos et al., 2011b; Yu et al., 2012). PLCζ shares the greatest homology with the PLCδ1 isoform, but it lacks the PH domain present at the N-terminus of PLCδ1 (Fig. 1). The PH domain is essential for the interaction of PLCδ1 with its phospholipid substrate PIP2 in the plasma membrane. We find that attachment of the PH domain of PLCδ1 to the N-terminus of PLCζ (PHδ1/PLCζ) does not alter its in vitro biochemical properties and consequently its ability to trigger Ca2+ oscillations in unfertilized mouse eggs (Figs 2 and 4, Tables I and II). This observation suggests that there may be a unique targeting mechanism of PLCζ involving determinants other than a PH domain. This may via a potential interaction with either another membrane phospholipid or an egg-specific protein, because even PH domain addition does not localize PHδ1/PLCζ to the plasma membrane PIP2 but instead it targets distinct vesicular structures inside the egg cortex, as we had previously observed for the wild-type PLCζ (Yu et al., 2012).

PI(3)P might represent a potential physiological ligand for PLCζ since previous experimental evidence suggested that the C2 domain of PLCζ binds in vitro with significant affinity to PI(3)P and with lower affinity to PI(5)P (Kouchi et al., 2005; Nomikos et al., 2011c). PI(3)P is a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase product whose localization is restricted to the limiting membranes of early endosomes and to the internal vesicles of multivesicular bodies (Gillooly et al., 2003). PI(3)P helps to recruit a range of proteins, many of which are involved in protein trafficking, to these membranes. To further investigate whether full-length PLCζ binds PI(3)P, and to determine which domain(s) mediates this interaction and the interaction with the substrate PIP2, we employed a liposome binding assay (Fig. 6). Our current observations suggest that PLCζ binds strongly to liposomes containing PIP2 and PI(3)P and that the EF hand domains of PLCζ are not involved in these interactions (Fig. 7a).

We have previously proposed that the EF hand domains play a vital role in the Ca2+ sensitivity of PLCζ activity, because deletion of both EF hands dramatically changed the EC50 of PLCζ Ca2+ sensitivity from 82 nM to 30 μM (Nomikos et al., 2005). In the present study, replacement of the EF hand domains of PLCζ with the corresponding domain from PLCδ1 (EFδ1/PLCζ), resulted in a ∼10-fold decrease in the Ca2+ sensitivity of PLCζ, without affecting its in vivo enzymatic activity or affinity for its substrate, PIP2 (Fig. 5, Table II). We have also now shown that the reduction in Ca2+ sensitivity of a PLC chimera can be used in a simple model to explain the different frequencies of Ca2+ oscillations recorded in eggs. Our model does not simulate all aspects of the oscillations occurring at fertilization, but does include the important feature of Ca2+-dependent positive feedback of InsP3 production (Swann and Lai, 2013). Our empirical data and mathematical model together provide a strong indication that the exquisite Ca2+ sensitivity of PLCζ, largely mediated by its EF hand domain, is a major factor in explaining why the sperm-specific PLCζ isoform is so much more effective at triggering high-frequency Ca2+ oscillations than the somatic cell PLCδ1 isoform.

Replacement of the XY-linker (PLCζ/XYlinkδ1) or the entire XY domain of PLCζ (PLCζ/XYδ1) with the corresponding region of PLCδ1 dramatically decreased the in vitro enzymatic activity and also the affinity of PLCζ for PIP2 (Fig. 4, Table II). These two chimeras also exhibited an increased EC50 value for Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 5), which suggests the involvement of these regions in Ca2+ regulation of PLCζ activity. Importantly, the replacement of the XY-linker or XY domain of PLCζ completely abolished the binding of this enzyme to PIP2-containing liposomes (Fig. 6). While PLCζ/XYlinkδ1 bound strongly to PI(3)P-containing liposomes, it is interesting that PLCζ/XYδ1 showed a significantly reduced binding, which suggests that the XY catalytic domain may play a role by contributing to the interaction of PLCζ with PI(3)P. The in vitro liposome binding data concurs with the lack of in vivo Ca2+ oscillation-inducing activity of these two chimeras in mouse eggs. Furthermore, these observations are consistent with previous findings suggesting that the XY-linker plays a central role in the regulation of PLCζ enzyme activity and its ability to interact with PIP2 (Nomikos et al., 2007, 2011b, c).

PLCζ contains a cluster of basic residues in the XY linker region proximal to the Y catalytic domain. These positively charged amino acids in the XY-linker might assist the anchoring PLCζ to membranes by enhancing the local PIP2 concentration adjacent to the XY catalytic domain via electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged PIP2. Notably, none of the somatic PLC isozymes possesses such a highly positively charged XY-linker region (Saunders et al., 2007). In contrast, PLCβ, δ and ε contain a highly negatively charged, mostly disordered XY linker region, which has been suggested to mediate auto-inhibition of PLC activity, preventing PIP2 access to the active site, by a combination of steric exclusion and electrostatic repulsion of negatively charged membranes (Hicks et al., 2008). Surprisingly, the XY-linker is the most non-conserved region of the PLCζ domain sequences determined from different species, except for the presence of positively charged residues. This suggests that the sequence divergence within this region may explain the species-specific patterns of Ca2+ oscillations observed for various mammalian PLCζs as well as their disparate relative potency when expressed in mouse eggs.

Our previous and current investigations suggest that the C2 domain of PLCζ is distinct from that of PLCδ1 and plays a vital role in PLCζ function. Replacement of the C2 domain of PLCζ with the corresponding domain of PLCδ1 (PLCζ/C2δ1) completely abolished the Ca2+ oscillation-inducing activity of PLCζ in mouse eggs (Fig. 2, Table I), although the Ca2+ sensitivity and affinity of the enzyme for PIP2 was unaffected (Figs 4 and 5, Table II). This is in agreement with previous observations where deletion of C2 domain from PLCζ led to inability of the C2-truncated protein to trigger Ca2+ oscillation in mouse eggs, although PIP2 hydrolytic enzyme activity and Ca2+ sensitivity was retained (Nomikos et al., 2005). Despite the fact that most C2 domains bind Ca2+, a critical determinant for the activities of their enzymes, there are some C2 domains that do not bind Ca2+ ions and these bind to phospholipids with relatively low affinity and specificity (Nalefski and Falke, 1996; Hurley and Misra, 2000). The C2 domain of PLCδ1 interacts with the membrane phospholipid, phosphatidylserine (PS), forming a C2–Ca2+–PS complex, which enhances the activity of the enzyme (Lomasney et al., 1999). There is currently no evidence for binding of the C2 domain to PS or other membrane phospholipids. However, if interaction of PLCζ with PI(3)P plays a role in targeting of PLCζ to the corresponding intracellular PIP2-containing vesicle, then the C2 domain may be mediating this interaction, as the PLCζ/C2δ1 chimera exhibited complete lack of binding to PI(3)P-containing liposomes. This potential intracellular phospholipid-targeting interaction role might explain why the C2 domain is essential for the Ca2+ oscillation-inducing activity in intact eggs (Nomikos et al., 2005).

Another hypothesis that can be proposed to explain the intracellular targeting of PLCζ is that it interacts primarily through the C2 domain with a specific, cytosolic egg protein which is responsible for localizing the sperm PLCζ to discrete endomembrane vesicles and not to the plasma membrane (Fig. 7a). In addition, if the PLCζ C2 domain-binding moiety is an egg-specific protein this might explain why PLCζ is so effective in eggs but not in other somatic cell types (Phillips et al., 2011). However, egg-specific PLCζ binding protein partners have not yet been identified (Fig. 7). In future, it will be important to identify the exact intracellular organelle that PLCζ targets. In addition, structural determination of the full-length PLCζ or its single C2 domain could possibly help to reveal the critical ion and lipid/protein binding sites in the PLCζ protein, providing a useful advance in understanding the complex regulatory mechanism of this vital enzyme.

Authors' roles

All authors contributed to experimental design, data analysis and manuscript preparation and approval. M.T., M.N., J.R.G.G. and B.L.C. constructed expression vectors and performed protein purification; K.E. conducted egg luminescence imaging; Z.S. prepared phospholipid liposomes; D.P. developed mathematical simulations; G.N., K.S. and F.A.L. provided experimental strategy.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (080701 to F.A.L. and K.S.). M.T. and K.E. hold research scholarships from NCSR Demokritos and the Libyan Government, respectively.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that no direct conflict of interest exists.

Acknowledgements

We thank Matilda Katan (University College London) for providing the rat PLCδ1 clone.

Appendix

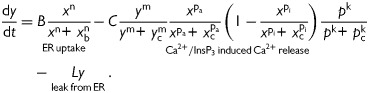

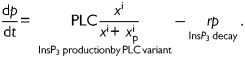

The series of three coupled non-linear differential equations describing mammalian egg Ca2+ oscillations accounts for:

Cytosolic free Ca2+:

|

(1) |

[Ca2+] in the endoplasmic reticulum:

|

(2) |

[Insp3] in the cytosol:

|

(3) |

Equation (1) accounts for variations in the free cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations. Cytosolic Ca2+ is modulated by fluxes across the cell membrane and fluxes across the cytosol-endoplasmic reticulum interface. Influx through the cellular membrane has been modeled as a constant, whereas efflux is modeled as an exponential function of cytosolic [Ca2+]. Uptake into the endoplasmic reticulum via the SERCA pump has been modeled as a sigmoidal function of cytosolic [Ca2+], while the release of Ca2+ via the InsP3 receptor channels is modeled as a product of Ca2+ activation and inactivation terms and a sigmoidal [InsP3] activation function. This formulation is in agreement with experimental evidence on the Ca2+ and InsP3 sensitivity of the InsP3 receptor channel open probability (Mak et al., 1998). Equation (3) describes the fundamentals of InsP3 generation by PLC-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2, a process that is Ca2+-activated. The degradation of InsP3 through phosphorylation or de-phosphorylation is described by a simple decay term.

The various coefficients and parameters are described in Table AI.

Table AI.

Parameters and coefficients of the mathematical model.

| Parameter | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

| A | Ca2+ influx through non-specific cation channels | 9.10−3 μM s−1++ |

| D | Rate constant for Ca2+ extrusion by the ATPase pump | 0.2 μM(1−q) s−1 |

| q | Exponent for x dependence of Ca2+ extrusion | 2 |

| B | ER uptake rate constant | 6.67 μM s−1 |

| Xb | Half-point of the ER ATPase activation sigmoidal | 4.4 μM |

| N | Hill coefficient for x dependence of ER uptake | 4 |

| C | InsP3- mediated release from InsP3-sensitive stores (IICR) | 100 μM s−1 |

| Yc | Half-point of the IICR Ca2+ efflux sigmoidal | 8.9 μM |

| M | Hill coefficient for y dependence of IICR | 2 |

| xca | Half-point of the IICR Ca2+ activation sigmoidal | 0.9 μM |

| pa | Hill coefficient for Ca2+ activation of IICR | 2 |

| xci | Half-point of the IICR Ca2+ inactivation sigmoidal | 2 μM |

| pi | Hill coefficient for Ca2+ inactivation of IICR | 3 |

| pc | Half-point of the IICR InsP3 activation sigmoidal | 0.1 µM |

| k | Hill coefficient for InsP3 activation of IICR | 2 |

| L | Leak from SR rate constant | 4.10−4 s−1 |

| PLC | Concentration of PLC isoform | μM·s−1 |

| xp | Half-point of the Ca2+ activation sigmoidal of InsP3 production | μM |

| i | Hill coefficient for Ca2+ activation of InsP3 production | 3.8 |

| r | Rate of InsP3 decay | 0.016 s−1 |

Description and numerical values of parameters employed in the mathematical model (Equations 1–3). Values of PLC and xp for specific simulations are given in the legend of Fig. 7.

References

- Atri A, Amundson J, Clapham D, Sneyd J. A single-pool model for intracellular calcium oscillations and waves in the Xenopus laevis oocyte. Biophys J. 1993;65:1727–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81191-3. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YS, Cantley LG, Chen CS, Kim SR, Kwon KS, Rhee SG. Activation of phospholipase C-gamma by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4465–4469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4465. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.8.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LJ, Larman MG, Saunders CM, Hashimoto K, Swann K, Lai FA. Sperm phospholipase Czeta from humans and cynomolgus monkeys triggers Ca2+ oscillations, activation and development of mouse oocytes. Reproduction. 2002;124:611–623. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240611. doi:10.1530/rep.0.1240611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dıaz J, Pastor N, Martinez-Mekler G. Role of a spatial distribution of IP3 receptors in the Ca2+ dynamics of the Xenopus embryo at the mid-blastula transition stage. Devel Dyn. 2005;232:301–312. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20238. doi:10.1002/dvdy.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont G, Heytens E, Leybaert L. Oscillatory Ca2+ dynamics and cell cycle resumption at fertilization in mammals: a modelling approach. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:655–665. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082845gd. doi:10.1387/ijdb.082845gd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falasca M, Logan SK, Lehto VP, Baccante G, Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Activation of phospholipase C gamma by PI 3-kinase-induced PH domain-mediated membrane targeting. EMBO J. 1998;17:414–422. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.414. doi:10.1093/emboj/17.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillooly DJ, Raiborg C, Stenmark H. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate is found in microdomains of early endosomes. Histochem Cell Biol. 2003;120:445–453. doi: 10.1007/s00418-003-0591-7. doi:10.1007/s00418-003-0591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresset A, Hicks SN, Harden TK, Sondek J. Mechanism of phosphorylation-induced activation of phospholipase C-gamma isozymes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35836–35847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.166512. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.166512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heytens E, Parrington J, Coward K, Young C, Lambrecht S, Yoon SY, Fissore RA, Hamer R, Deane CM, Ruas M, et al. Reduced amounts and abnormal forms of phospholipase C zeta (PLCzeta) in spermatozoa from infertile men. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2417–2428. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep207. doi:10.1093/humrep/dep207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks SN, Jezyk MR, Gershburg S, Seifert JP, Harden TK, Sondek J. General and versatile autoinhibition of PLC isozymes. Mol Cell. 2008;31:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.018. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JH, Misra S. Signaling and subcellular targeting by membrane-binding domains. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:49–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.49. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J, Parrington J, Fissore RA. PLCζ and its role as a trigger of development in vertebrates. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78:846–853. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21359. doi:10.1002/mrd.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashir J, Jones C, Lee HC, Rietdorf K, Nikiforaki D, Durrans C, Ruas M, Tee ST, Heindryckx B, Galione A, et al. Loss of activity mutations in phospholipase C zeta (PLCζ) abolishes calcium oscillatory ability of human recombinant protein in mouse oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:3372–3387. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der336. doi:10.1093/humrep/der336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashir J, Konstantinidis M, Jones C, Lemmon B, Lee HC, Hamer R, Heindryckx B, Deane CM, De Sutter P, Fissore RA, et al. A maternally inherited autosomal point mutation in human phospholipase C zeta (PLCζ) leads to male infertility. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:222–231. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der384. doi:10.1093/humrep/der384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott JG, Kurokawa M, Fissore RA, Schultz RM, Williams CJ. Transgenic RNA interference reveals role for mouse sperm phospholipase Czeta in triggering Ca2+ oscillations during fertilization. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:992–996. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.036244. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.104.036244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi Z, Fukami K, Shikano T, Oda S, Nakamura Y, Takenawa T, Miyazaki S. Recombinant phospholipase Czeta has high Ca2+ sensitivity and induces Ca2+ oscillations in mouse eggs. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10408–10412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313801200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M313801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi Z, Shikano T, Nakamura Y, Shirakawa H, Fukami K, Miyazaki S. The role of EF-hand domains and C2 domain in regulation of enzymatic activity of phospholipase Czeta. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21015–21021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412123200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M412123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomasney JW, Cheng HF, Wang LP, Kuan Y, Liu S, Fesik SW, King K. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding to the pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-delta1 enhances enzyme activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25316–25326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25316. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.41.25316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomasney JW, Cheng HF, Roffler SR, King K. Activation of phospholipase C delta1 through C2 domain by a Ca(2+)-enzyme-phosphatidylserine ternary complex. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21995–22001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21995. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.31.21995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackrill JJ, Challiss RA, O'Connell DA, Lai FA, Nahorski SR. Differential expression and regulation of ryanodine receptor and myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels in mammalian tissues and cell lines. Biochem J. 1997;327:251–258. doi: 10.1042/bj3270251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak DD, McBride S, Foskett JK. Inositol 1,4,5-tris-phosphate activation of inositol tris-phosphate receptor Ca2+ channel by ligand tuning of Ca2+ inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15821–15825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15821. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.26.15821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalefski EA, Falke JJ. The C2 domain calcium-binding motif: structural and functional diversity. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2375–2390. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051201. doi:10.1002/pro.5560051201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Blayney LM, Larman MG, Campbell K, Rossbach A, Saunders CM, Swann K, Lai FA. Role of phospholipase C-zeta domains in Ca2+-dependent phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis and cytoplasmic Ca2+ oscillations. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31011–31018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500629200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M500629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Mulgrew-Nesbitt A, Pallavi P, Mihalyne G, Zaitseva I, Swann K, Lai FA, Murray D, McLaughlin S. Binding of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-zeta (PLC-zeta) to phospholipid membranes: potential role of an unstructured cluster of basic residues. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16644–16653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701072200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M701072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Elgmati K, Theodoridou M, Calver BL, Cumbes B, Nounesis G, Swann K, Lai FA. Male infertility-linked point mutation disrupts the Ca2+ oscillation-inducing and PIP(2) hydrolysis activity of sperm PLCζ. Biochem J. 2011a;434:211–217. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101772. doi:10.1042/BJ20101772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Elgmati K, Theodoridou M, Georgilis A, Gonzalez-Garcia JR, Nounesis G, Swann K, Lai FA. Novel regulation of PLCζ activity via its XY-linker. Biochem J. 2011b;438:427–432. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110953. doi:10.1042/BJ20110953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Elgmati K, Theodoridou M, Calver BL, Nounesis G, Swann K, Lai FA. Phospholipase Cζ binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2 requires the XY-linker region. J Cell Sci. 2011c;124:2582–2590. doi: 10.1242/jcs.083485. doi:10.1242/jcs.083485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Swann K, Lai FA. Starting a new life: sperm PLC-zeta mobilizes the Ca2+ signal that induces egg activation and embryo development: an essential phospholipase C with implications for male infertility. Bioessays. 2012;34:126–134. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100127. doi:10.1002/bies.201100127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomikos M, Yu Y, Elgmati K, Theodoridou M, Campbell K, Vassilakopoulou V, Zikos C, Livaniou E, Amso N, Nounesis G, et al. Phospholipase Cζ rescues failed oocyte activation in a prototype of male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.035. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthimos D, Edwards DH, Griffith TM. Minimal model of arterial chaos generated by coupled intracellular and membrane Ca2+ oscillators. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H1119–H1144. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthimos D, Haddock RE, Hill CE, Griffith TM. Dynamics of a three-variable nonlinear model of vasomotion: comparison of theory and experiment. Biophys J. 2007;93:1534–1556. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.106278. doi:10.1529/biophysj.107.106278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SV, Yu Y, Rossbach A, Nomikos M, Vassilakopoulou V, Livaniou E, Cumbes B, Lai FA, George CH, Swann K. Divergent effect of mammalian PLCζ in generating Ca2+ oscillations in somatic cells compared with eggs. Biochem J. 2011;438:545–553. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101581. doi:10.1042/BJ20101581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi A, Gaspers LD, Thomas AP, Hofer T. Models of IP3 and Ca2+ oscillations: frequency encoding and identification of underlying feedbacks. Biophys J. 2006;90:3120–3133. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072249. doi:10.1529/biophysj.105.072249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runft LL, Jaffe LA, Mehlmann LM. Egg activation at fertilization: where it all begins. Dev Biol. 2002;245:237–254. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0600. doi:10.1006/dbio.2002.0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders CM, Larman MG, Parrington J, Cox LJ, Royse J, Blayney LM, Swann K, Lai FA. PLC Zeta: a sperm-specific trigger of Ca(2+) oscillations in eggs and embryo development. Development. 2002;129:3533–3544. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders CM, Swann K, Lai FA. PLCzeta, a sperm-specific PLC and its potential role in fertilization. Biochem Soc Symp. 2007;74:23–36. doi: 10.1042/BSS0740023. doi:10.1042/BSS0740023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SM, Murray D. Molecular modeling of the membrane targeting of phospholipase C pleckstrin homology domains. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1934–1953. doi: 10.1110/ps.0358803. doi:10.1110/ps.0358803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K, Lai FA. PLCζ and the initiation of Ca(2+) oscillations in fertilizing mammalian eggs. Cell Calcium. 2013;53:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann K, Campbell K, Yu Y, Saunders C, Lai FA. Use of luciferase chimaera to monitor PLCzeta expression in mouse eggs. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;518:17–29. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-202-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah G, Jung P, Machaca K. Modeling Ca2+ signaling differentiation during oocyte maturation. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.01.010. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GSB, Molinelli EJ, Smith GD. Modeling local and global intracellular calcium responses mediated by diffusely distributed inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. J Theor Biol. 2008;253:170–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.02.040. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SY, Jellerette T, Salicioni AM, Lee HC, Yoo MS, Coward K, Parrington J, Grow D, Cibelli JB, Visconti PE, et al. Human sperm devoid of PLC, zeta 1 fail to induce Ca(2+) release and are unable to initiate the first step of embryo development. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3671–3681. doi: 10.1172/JCI36942. doi:10.1172/JCI36942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Nomikos M, Theodoridou M, Nounesis G, Lai FA, Swann K. PLCζ causes Ca(2+) oscillations in mouse eggs by targeting intracellular and not plasma membrane PI(4,5)P(2) Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:371–380. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-08-0687. doi:10.1091/mbc.E11-08-0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]