Abstract

The University of Cincinnati (UC) has been active in the National Library of Medicine's Integrated Advanced Information Management Systems (IAIMS) program since IAIMS' inception in 1984. UC received IAIMS planning and modeling grants in the 1980s, spent the 1990s practicing its own form of “iaims” and refining its vision, and, in May 2003, received an IAIMS operations grant in the first round of awards under “the next generation” program. This paper discusses the history of IAIMS at UC and describes the goals, methods, and strategies of the current IAIMS program. The goals of UC's IAIMS program are to: improve teaching effectiveness by improving the assessment of health professional students and residents in laboratory and clinical teaching and learning environments; improve the ability of researchers, educators, and students to acquire and apply the knowledge required to be more productive in genomic research and education; and increase the productivity of researchers and administrators in the pre-award, post-award, and compliance phases of the research lifecycle.

INTRODUCTION

The University of Cincinnati (UC) Medical Center campus is home to the colleges of medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and allied health sciences. Academic Information Technology and Libraries (AIT&L) supports these colleges, providing a full suite of library services, training and education services, instructional technology support, desktop computer support, server and security support, Website development, and administrative, academic, and research systems development. The University of Cincinnati Office of Information Technology (UCit) planned, installed, and maintains the university's gigabit network for data, voice, and university email systems; negotiates institutional licenses for hardware and software; develops and maintains university-wide administrative systems; provides technology support and training for employees and students; and, in partnership with academic units, provides information policy leadership.

UC has been active in the National Library of Medicine's Integrated Advanced Information Management Systems (IAIMS) program since its inception in 1984. UC received IAIMS planning and modeling grants in the 1980s, spent the 1990s practicing its own form of “iaims” and refining its vision, and, in May 2003, received an IAIMS operations grant in the first round of awards under “the next generation” program. The goals of the current, funded IAIMS program are to improve teaching effectiveness, improve the application of knowledge in genomic research, and increase the productivity of researchers.

BACKGROUND

1984–1991

The UC Medical Center embarked on an IAIMS preplanning process, led by Nancy Lorenzi, that resulted in the award of an IAIMS planning grant in 1984. With that grant (1984–1986), the medical center completed a strategic information management planning process. The first IAIMS strategic plan was published in 1986 shortly after Donald C. Harrison was appointed the senior vice president and provost for health affairs. In 1987, the medical center received an IAIMS modeling grant, for which Gregory W. Rouan, professor and associate chair for medical education, Department of Internal Medicine, and president of the Health Alliance of Greater Cincinnati's physicians organization, was clinical director. Also in 1987, John J. Hutton became dean of the College of Medicine and joined Dr. Harrison in supporting the IAIMS initiative. They brought with them a keen sense of the importance of information technology to academic medical centers and a strong belief that information technology was a strategic investment for the future of the UC Medical Center. From 1987 to 1990, IAIMS modeling efforts focused on the development of a clinician's workstation prototype. The UC Medical Center was not funded for IAIMS implementation grants in 1990 and 1991.

1992–2000

During the early 1990s, the UC Medical Center underwent tremendous organizational change and unprecedented growth. During this same period, information technology was developing at an accelerated rate and had become part of everyday life. Ohio's universities took a major leap forward with the statewide implementation of OhioLINK,† a consortium of 84 academic libraries that licenses 100 databases (including MEDLINE and 18 other health or life sciences databases) and more than 5,600 full-text electronic journals. OhioLINK makes 39 million books, media, and journals available to individuals, regardless of location, within two days.

Until 1995, UC Medical Center libraries and information technology operations were independent, largely uncoordinated units. In 1995 and 1996, University Hospital was separated from university ownership and became a member of the Health Alliance of Greater Cincinnati. The medical center information technology units and libraries were merged into a single organization, AIT&L. Roger Guard was named assistant senior vice president of AIT&L. Dr. Hutton assigned AIT&L the responsibility of providing information technology customer support, training, and Web development services to the college of medicine and appointed Mr. Guard chief information officer for the college of medicine.

Under the leadership of Dr. Harrison, Dr. Hutton, and Mr. Guard, the UC Medical Center began a strategic planning process that resulted in a vision for information technology and libraries and included an annual review process. Four strategic planning retreats—1996, 1999, 2001, and 2003—of UC Medical Center leaders, faculty, and students have been held to assess information technology and information management needs and to set priorities and direction. To meet the medical center's growing information technology needs, a decision was made to seek investment from multiple sources, including federal and state agencies and private organizations.

In 1996, Dr. Harrison formed and chaired the Integrated Information Systems Committee to coordinate and integrate infrastructure, systems, and services. By 1997, this committee—whose members include representatives from the medical center, the university (including the vice president for information technology and a representative from the office of the senior vice president and provost for baccalaureate and graduate education), and the Health Alliance of Greater Cincinnati—had developed information technology standards spanning several jurisdictions that provided the foundation for greater efficiency and improved functionality across these jurisdictions in the areas of networking and communications, relational databases, email, voicemail, desktop and server platforms, and operating systems.

In late 1994, the US Department of Commerce awarded AIT&L a $375,000 grant to develop NetWellness,‡ a consumer health information service that was one of the first health sites on the Web. NetWellness reached out to many organizations, private and public, to form over 40 external partnerships. In addition, internal partnerships with departments and colleges engaged faculty to provide “Ask an Expert” services. Currently, 250 faculty volunteer their time to answer questions on hundreds of health topics posed by NetWellness visitors. Faculty have answered more than 22,000 questions since 1995. The State of Ohio funded NetWellness from 1995 to 2001. In 1997, Case Western Reserve University and The Ohio State University, Ohio's other Carnegie I research universities, joined NetWellness as full partners. Faculty from all three universities collaborated to provide Ask an Expert services for a growing number of health topics. In 2002 and 2003, the US Department of Health and Human Services awarded grants to NetWellness to continue its development. NetWellness has also served as a research and development laboratory for testing new systems and tools. Medical center and IAIMS databases, middleware, Web design, and project management talent were developed in this laboratory. NetWellness continues to provide a unique development and testing environment.

In all these developments, UC was practicing its own form of “iaims.” Multi-institutional collaborations, grassroots participation from faculty and students, integration of systems and infrastructure, and broad agreements on technology standards reflect basic IAIMS precepts. The region's Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center joined the Integrated Information Steering Committee for initiatives including email directories and network standards. Also in 1997, development of an integrated database, which began in 1995, gained traction. The integrated database, built on a central, shared core of user information and applications, underpins all new applications. The initial database served as a data repository for faculty who participated in NetWellness, but its purposes quickly expanded as more applications were built to take advantage of this shared core data. Today, all new applications are developed using this core data.

The 1997 information technology standards defined a vision for integrated information systems through 2003 and the standards necessary to attain the vision. Much progress has been made toward that vision, particularly in the growth of solid infrastructure services that provide access and support. These services, developed under the leadership of UCit, included network, email, help desk, institutional software and hardware licenses, information policies, and instructional technology. In 1997, UC also enhanced its connection to the Internet by becoming an Internet2 charter member. Progress in delivering these services enabled parallel growth in integrated database development, Web development, training, and technology support services at the UC Medical Center. The 1997 vision targeted knowledge management for 2003, after access, support, and database development were in place. These developments set the stage for the 2002 IAIMS proposal focused on developing knowledge management tools, systems, and services.

An outgrowth of this organizational emphasis on intra- and extra-institutional collaboration, best represented by the Integrated Information Steering Committee and NetWellness, was a flourishing of partnerships across the UC Medical Center. In 1999, the Distributive Learning Collaboratory, a partnership of the medical center's four colleges and AIT&L, began to develop a digital curriculum across the four colleges. Under the leadership of William K. Fant, assistant dean for clinical and external affairs, associate professor, College of Pharmacy, and an IAIMS co-investigator, the collaboratory secured a grant from the Ohio Board of Regents to provide the tools (servers, development software, and network) to enable faculty to develop Web-based courses that have broad application throughout the medical center.

In 1998, key offices responsible for grants facilitation and administration began to collaborate on a vision for increasing extramural funding through more productive grants administration. The associate dean for research and graduate education for the college of medicine had provided Web-based services to medical center researchers for several years. The college's office of research Website§ has grown to include current funding opportunities, promotion of core facilities, expertise matching, literature resources, and research assistant applications. The medical center's associate senior vice president for administrative services and finance and the college of medicine's associate dean for management and finance, with AIT&L as his developer, began to convert the medical center's administrative and finance operations from a paper-based to a digital system. Together, these offices have built a solid foundation of research administration applications that are tightly linked to the medical center's integrated database. Through this collaborative development process, these offices have developed a shared vision of a comprehensive suite of integrated digital services for research administration.

In 2000, the four colleges of the UC Medical Center and AIT&L again came together to form the IT Partnership, whose initial purpose was limited to server technologies and strategies. These purposes included consolidating college servers, eliminating server redundancy, ensuring regular backup, providing a secure and regulated environment, and providing direct connections to the university's network backbone. The IT Partnership also established a common email standard for the faculty, staff, and students of the UC Medical Center.

Also in 2000, the college of medicine, with AIT&L as project manager, began the development of the Center for Competency Development and Assessment (CCDA), which utilizes a digital media-acquisition and asset-management system to capture and store the interactions between medical students and standardized patients in sixteen separate examination rooms in which multiple testing scenarios are conducted. The CCDA system also indexes data for review and evaluation, provides a method of annotation, and provides off-line archival storage. The system is activated by medical students using their UC identification cards to access the medical center's integrated database.

2001–2003

By 2001, the major information technology “utilities” were state-of-the-art; a collaborative organizational culture was well rooted throughout the UC Medical Center; and virtually all information technology and library initiatives were “iaims.” But the 1997 vision for knowledge management was still not a reality. Medical center leaders began to assess the value of restarting the IAIMS program to boost the development needed to achieve the vision. During the spring of 2001, they arranged meetings and discussions with various faculty, staff, and student groups throughout the UC Medical Center to assess needs and levels of interest. The participants concluded that an IAIMS steering committee should be formed and that a broad-based, grassroots planning process should begin, building on past IAIMS experiences. Because of the previous IAIMS work of the 1980s and action-focused culture, IAIMS planning began immediately without grant support, in preparation for submitting an operations grant proposal in 2002.

Two groups key to the planning process were the Distributive Learning Collaboratory and the IT Partnership. Both had expanded to multi-unit collaborations. In 2001, the collaboratory, under the leadership of John R. Kues, the IAIMS evaluation coordinator, successfully secured a second Ohio Board of Regents grant, titled “Students on the Move.” The project delivers curricular materials, library and information resources, assessment tools, and the Internet to students (and faculty and staff) via wireless or synchronized personal digital assistants. Also in 2001, the IT Partnership expanded its efforts to include creating the architecture of Active Directory Services for the UC Medical Center in collaboration with the rest of the university, implementing a three-tier network security model, coordinating Web development and database design, and expanding the uses of the integrated database. The IT Partnership agreed to a common design for college and medical center Websites (currently 50 sites), creating a consistent brand, providing common site organizational features, and creating appropriate links among sites.** The IT Partnership also recognized the need to expand the use of the integrated database to all applications and systems developed at the UC Medical Center and helped to expand the specifications for this master database. The integrated database has been modified to meet the emerging eduPerson and MedMid standards promulgated by EDUCAUSE, Internet2, and the Association of American Medical Colleges.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI'S OBJECTIVES

Based on UC's vision for knowledge management and needs, the following long-term objectives have been identified. Information and knowledge management are key to achieving them. These objectives are crucial to the medical center's fulfilling its mission.

Improve teaching effectiveness by improving the assessment of health professional students and residents in laboratory and clinical teaching and learning environments.

Improve the ability of researchers, educators, and students to acquire and apply the knowledge required to be more productive in genomic research and education.

Increase the productivity of researchers and administrators in the pre-award, post-award, and compliance phases of the research lifecycle.

These objectives are crucial to the medical center's fulfilling its mission. The specific aims of UC's IAIMS program are to develop and implement the following three projects:

a digital multimedia record documenting that students and residents acquire the knowledge, attitude, and clinical skills required for awarding degrees and credentialing by accrediting or licensing agencies

a coordinated bioinformatics program with a focus on digital tools for filtering and organizing genomics information and for educating researchers and students about the fundamental principles of bioinformatics

an efficient, effective, and comprehensive digital research administration service that converts stand-alone systems and isolated processes into integrated digital services throughout the university; portals to digital research administration information will be created by user profiles that represent the professional roles and interests of the different individuals in the institution.

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT

During the past decade, challenges related to the management of data and information in academic health centers have shifted [1, 2]. In the 1980s, the challenge was to provide access to information where no convenient access existed. Today, access is nearly ubiquitous. The information environment of students, researchers, practitioners, and administrators is saturated with data and information of widely varying quality and overwhelming quantity. Today, the most significant challenge is the transformation of data and information into knowledge [3]. The UC Medical Center's immediate opportunity is to develop tools that enable individuals to manage the information overload, so that they can create and take advantage of new knowledge [4–6].

Our vision for knowledge management sees individuals having reliable, secure access to information that is filtered, organized, and highly relevant for specific tasks and needs defined by personal profiles. Smart tool sets and portals [7–13] help individuals transform data and information into knowledge in support of their roles at the UC Medical Center [14, 15]. Smart tool sets will evolve to become the next generation knowledge management applications that we call smart digital services.

During the next five years, we will progress toward our knowledge management vision by beginning to design, implement, and test smart digital services, building on our technical strengths and our knowledge management model [16–21]. Our strengths include: a culture and organization that encourages collaboration among individuals in colleges and other key units, high-speed network infrastructure with universal access, outstanding digital health information via OhioLINK and UC libraries, successful development of an institutional integrated database, and talent in advanced middleware programming, design, and project management.

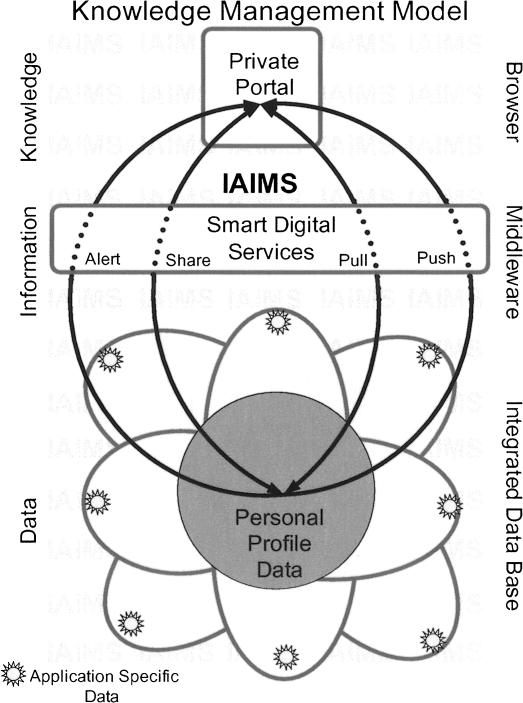

Our challenge over the next ten years is to develop smart tools sets and sophisticated knowledge applications that allow us to manage the information overload [22]. We are living in a period of disruptive and transformational change where information is expanding at an unprecedented pace [23, 24]. To be successful, organizations must be able to rapidly adjust to change and to develop tools that enable individuals to manage information and to transform context-appropriate information into knowledge [25]. To meet this need, the medical center has developed a Knowledge Management Model (Figure 1) for the development of smart digital services, beginning with smart tool sets and evolving to sophisticated knowledge applications. The key building blocks incorporate the following:

Figure 1.

Knowledge Management Model

an integrated database with a “people core,” that is, a core of shared data and a flexible, progressive “petal” design in which applications can add to and share the central data;

“smart forms” that reduce data entry, errors, and turnaround time;

personal profiles that match and link relevant information in a portal environment;

digital forms routing that replaces paper, saves time, and reduces costs;

reusable software components that save time and money and reduce costs;

data standards, such as MeSH and the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) [26–28] for biomedical vocabulary and the developing eduPerson [29] and MedMid standards for “people”; and

single login and password authentication across all systems.

The three projects selected for our IAIMS program will be built using our Knowledge Management Model. These projects, in addition to addressing institutional long-term objectives, are built on our practical talents and tools and are integrated at several levels.

DEVELOPING BUILDING BLOCKS

Our knowledge management vision is built on four building blocks: our integrated database, development of personal profiles, advanced applications architecture, and smart digital services and information portals. These building blocks will enable the UC Medical Center to transform repositories of interrelated data primarily intended for back office use into a knowledge management system that uses the network to provide everyone at the UC Medical Center with context-appropriate information. Information will be relevant to an individual's work and will be organized for effective use, with a minimum of irrelevant material. In this vision, each person will have a personal profile that smart digital services will use to push relevant information and literature resources, alert to important events, enable requests of specific information (pull), and facilitate effective interaction (share) with other individuals [30].

The integrated database: people, objects, and security

The integrated database provides a mechanism for managing both personal and administrative data. Using a common “person core” linking data with people facilitates the sharing of information among different applications. We maintain the basic organization of the integrated database, as a person core surrounded by petals corresponding to groups of objects (Figure 1). We will expand on the types of data that are stored in, or are accessible from, the integrated database, to include a wide variety of media. In fact, the ability to catalog digital video, digital images, and digital audio associated with clinical skills training is an essential ingredient of two of our IAIMS projects, portfolio credentialing and research administration.

To start the transition from the current system (oriented toward back office activities) to a knowledge management system, we will add functionality to the integrated database to allow it to automatically maintain customer interest profiles. Biomedical vocabulary standards such as MeSH and UMLS will be the basis for building such profiles. An individual profile will determine which information is provided to an individual. The integrated database will also provide the basis for user authentication and security. Users will be provided with database access based on a set of dynamically developed and applied rule sets.

Profile management

Stronger profile management functionality will be added to the current integrated database and middleware environments. Standards such as MeSH and UMLS will be used for keyword matching. When we combine this functionality with smart digital services, these projects will deliver to individuals exactly the information and literature resources they need, organized as they prefer to meet their individual priorities.

The activities of people at the UC Medical Center are related to their jobs, the roles they play, the location of their work, and the positions they hold. For example, a professor of internal medicine (job), who works part time in a research lab (location) and who is a member of an the Institutional Review Board (IRB) Review Committee (position), is the principal investigator on a research project overseen by IRB that involves the use of radioactive material (role). The integrated database contains the “jobs,” “roles,” “position,” and “location” data, by individual, for administrative systems, such as the IRB and Radiation Safety Systems.

The integrated database will automatically maintain a personal profile for each person at the UC Medical Center. It will identify basic information that is easily accessible by that person, based on his or her activities. For example, the professor of internal medicine above works with radioactive materials. He is therefore referenced in the Radiation Safety System. As a result, his personal profile indicates that he should be notified of training opportunities related to radiation safety. Similarly, because he is a principal investigator on a protocol administered by the IRB office, his personal profile allows him to have access to IRB office data for all the protocols for which he is a principal investigator or coinvestigator. All individuals at the medical center will have the ability to easily modify their personal profiles to add or remove information, to make the entire “system” more useful in their daily activities. Authorized administrators will also be able to modify profiles to ensure that alerts such as training notices and announcements reach the appropriate people.

Applications architecture

An application's architecture is built on Web applications constructed of rich Internet-based components that can span multiple applications, data sources, and media [31]. This architecture provides people with access to just the particular parts of a larger system that they actually need.

All new applications developed at the medical center share a common design, in which application data is stored in an SQL Server database and individuals use Web applications to access this data [32]. Data are linked to individuals via references to the person core of the integrated database. A security module, which we will make Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant, provides role and authorization information for each system user. Web services (components) are used to provide equivalent functionality across multiple Web applications. Data in the integrated database correspond to “objects” (for example, a university form or research protocol) managed by the Web applications. This design is modular: each object corresponds to its own section of the database, so changes in handling of one object will not affect the handling of other objects. The design is easily expandable: adding new functionality is accomplished by adding sections to the integrated database, without any effect on existing functionality. The design is also readily scalable: system load can be managed by configuring the back-end SQL Server database and application server environments, and, because access is Web-based, new users can be added easily.

Smart digital services and information portals

Smart digital services are Web-based components that provide context-appropriate, custom-organized access to information in the integrated database, in designated external databases such as MEDLINE and other literature databases and in designated Websites. They are designed to filter out irrelevant information, so that individuals see exactly the information they need, organized for effective use. The first smart digital service that we will develop is the Consultant, which will use the information in a personal profile to push to a customer the information they need.

The use of smart digital services will allow us to change the paradigm for delivery of information from “Figure out what you need and go get it” to “here is the information you need” on a customized portal, a “My UC” page. Smart digital services will increase the effectiveness of people at the UC Medical Center by allowing them to concentrate on doing the work rather than on figuring out how to find the information needed to do the work.

When people log onto the UC network, they can open their private portal, which is dynamically created, based on the data in the individual's personal profile, including positions, jobs, authentication, and role information in the security module, and by data added by the individual on self-identification pages. Information on the My UC page will be determined by information in the personal profile. The role of the Consultant smart digital service will be to dynamically create each person's My UC page from the personal profile.

We will develop other smart digital services to enable individuals retrieve the information they need, organized for easy use. In addition to the Consultant, we will develop the Requestor, which will enable an individual to request (pull) specific information; the Alerter, which will alert a person of items of especially high interest; and the Expert, which will let customers “share” data with others on the network.

THE VALUE OF INTEGRATED ADVANCED INFORMATION MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI

The IAIMS operations grant will provide a boost toward the development of our knowledge management vision. In the data-information-knowledge continuum, IAIMS will help to accelerate our pace in migrating from a system that provides access to data and information to a program that develops smart tool sets for managing information and knowledge. We will initially focus on developing and integrating smart tools sets, building on our experience developing smart forms and personal profiling. Concurrently, we will prototype more sophisticated applications for filtering information, provide single login and authentication, and offer advanced alerting of critical information.

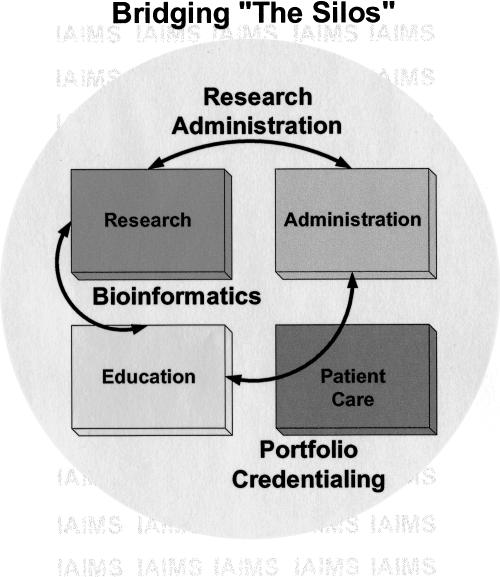

Our IAIMS projects not only bridge the traditional “silos” of education, research, patient care, and administration (Figure 2) but also fill major gaps in the medical center's ability to achieve its mission and strategic vision more effectively. Faculty and students will have more time to devote to educating, learning, researching, and practicing and will spend less time and effort sifting through irrelevant information and correcting data and processes that could have been validated at the time of entry [33].

Figure 2.

Bridging “The Silos”

The portfolio-based credentialing project will address the challenge of providing the rich communication and documentation necessary for optimal student learning. Students, residents, and faculty will have access to a complete multimedia record of the student's or resident's performance, with real-time feedback and remediation. The portfolio will also serve as a mechanism for conducting curricular review.

The bioinformatics project will coordinate our disparate bioinformatics programs, provide knowledge management tools, and provide focused training in bioinformatics applications used in genomic research to students, educators, and researchers. The medical center has invested heavily in genomic research as a strategic focus and aspires to be a national leader. Developing the proposed bioinformatics program is crucial to that success.

The research administration project will enable researchers to improve their productivity by developing grant proposals more efficiently and effectively, with compliance requirements built into the process [34]. Administrators will have access to all context-appropriate information to facilitate the medical center's overall research enterprise. To fulfill the medical center's Millennium Plan for doubling its extramural research funding in five years, this project is essential.

These projects will serve the medical center's mission of improving “the quality of health for people everywhere.” In this context, the medical center will build, test, and scale tools, processes, and systems that will have broader application and impact. Our goal is to develop a model for IAIMS that can serve the university and other institutions for years to come.

CONCLUSION

IAIMS began at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center in 1984, and, whether writ large or small, its principles have guided the development of information technology planning and priorities. Key premises underpinning the official IAIMS planning process that resumed in 2001 and resulted in the award of an IAIMS operations grant in May 2003 were:

The IAIMS proposal would be a medical center–wide strategic endeavor, reflecting the known and projected priority information needs of the medical center, that is, a five-year plan and investment.

IAIMS would accelerate the development of priorities and projects.

AIT&L would be the main resource for labor.

The IAIMS Steering Committee recommended using existing, seasoned AIT&L staff on the grant. New staff would be hired to backfill for the daily workload AIT&L performs for the medical center. This approach would increase the likelihood that the project pace would be accelerated and that basic ongoing services would not deteriorate.

Projects would cross the service domains of education, research, and patient care and the political domains represented by four colleges and many other units.

UC's IAIMS projects would be replicable and shared with the academic health care community.

Footnotes

* This program is supported by NIH Grant no. G08 LM 7853 from the National Library of Medicine.

† The OhioLINK Website may be viewed at http://www.ohiolink.edu.

‡ The NetWellness Website may be viewed at http://netwellness.org.

§ The University of Cincinnati College of Medicine's Office of Research Website may be viewed at http://www.med.research.uc.edu.

** The University of Cincinnati Medical Center Website may be viewed at http://medcenter.uc.edu.

Contributor Information

J. Roger Guard, Email: Roger.Guard@uc.edu.

Ralph F. Brueggemann, Email: Ralph.Brueggemann@uc.edu.

William K. Fant, Email: Bill.Fant@uc.edu.

John J. Hutton, Email: John.Hutton@cchmc.org.

John R. Kues, Email: John.Kues@uc.edu.

Stephen A. Marine, Email: Stephen.Marine@uc.edu.

Gregory W. Rouan, Email: Greg.Rouan@uc.edu.

Leslie C. Schick, Email: Leslie.Schick@uc.edu.

REFERENCES

- Blue Ridge Academic Health Group. Into the 21st century: academic health centers as knowledge leaders. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Health System, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JA. Basic principles of information technology organization in health care institutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997 Mar–Apr. 4(2 Suppl):S31–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead WW. It's the information that's important, not the technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998 Jan–Feb. 5(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krill P. Overcoming information overload. InfoWorld. 2000 Jan 10. 22(2):63. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MT, Nohria N, and Tierney T. What's your strategy for managing knowledge? Harv Bus Rev. 1999 Mar–Apr. 77(2):106–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson NW. Things to come: postmodern digital knowledge management and medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1995 Mar–Apr. 2(2):73–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox P. Portals can open array of services. Computerworld. 2002 Mar 4. 36(10):24–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kontzer T. Portals transform into a strategic collaboration asset. Informationweek. 2002 Mar 18. 880:86–8. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien D. Portals combat information overload. I/S Analy. 2002 Mar. 41(3):2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Pelz-Sharpe A, Harris-Jones C, and Ashenden A. The need for portals. KMWorld. 2001 Nov–Dec. 10(10):12. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Vizard M, Moore C, and Sullivan T. Portals pack integration punch. InfoWorld. 2002 Jan 28. 24(4):17. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell F, Gilbert M, Hayward S, Logan D, and Lundy J. New focus on knowledge and collaboration begins in 2002. [Web document]. Stamford, CT: Gartner, 2002. [cited 30 May 2003]. <http://www.gartner.com>. [Google Scholar]

- Stunden A. Portals: the lady or the tiger? EDUCAUSE Rev. 2002 May–Jun. 37(3):58–9. [Google Scholar]

- SSR Abidi. Knowledge management in healthcare: towards ‘knowledge-driven’ decision-support services. Int J Med Inf. 2001 Sep. 63(1–2):5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty V. Knowledge is about people, not databases. Ind Commer Train. 1999 Dec. 31(7):262–6. [Google Scholar]

- MED Koenig. The third stage of KM emerges. KMWorld. 2002 Mar. 11(3):20–1. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B. On-demand KM: a two-tier architecture. IT Pro. 2002 Jan–. Feb;4. 1:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Raisinghani MS. Knowledge management: a cognitive perspective on business and education. Am Bus Rev. 2000 Jun. 18(2):105–12. [Google Scholar]

- Strawser CL. Building effective knowledge management solutions. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2000 Spring. 14(1):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson I. Dollar$ & $en$e, part VI: knowledge management: the state of the art. Clin Leadersh Manag Rev. 2001 May–Jun. 15(3):187–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. Practical issues in knowledge management. IT Pro. 2002 Jan–Feb. 4(1):35–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala M. Drowning in a sea of information? Econtent. 2002 Jun. 25(6):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Strachan PA. Managing transformational change: the learning organization and teamworking. Team Perform Manage. 1996 Feb. 2(2):32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Horak BJ. Dealing with human factors and managing change in knowledge management: a phased approach. Top Health Inf Manage. 2001 Feb. 21(3):8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart TA. The wealth of knowledge. New York, NY: Currency Books, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg DA, Humphreys BL, and McCray AT. The Unified Medical Language System. Methods Inf Med. 1993 Aug. 32(4):281–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys BL, Lindberg DA, Schoolman MH, and Barnett GO. The Unified Medical Language System: an informatics research collaboration. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998 Jan–Feb. 5(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle MS, Cole WG, Sherertz DD, and Nelson SJ. Navigating to knowledge. Methods Inf Med. 1995 Mar. 34(1–2):214–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Educause/Internet2. eduPerson object class. [Web document]. Washington, DC: EDUCAUSE, 2002. [cited 30 May 2003]. <http://www.educause.edu/eduperson/>. [Google Scholar]

- Weidner D. Using connect and collect to achieve the KM endgame. IT Pro. 2002 Jan–Feb. 4(1):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. Surveying portal paths. InfoWorld. 2002 Apr 29. 24(17):1– 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Frost JP. Web technologies for information management. Inf Manag J. 2001 Oct. 35(4):34–7. [Google Scholar]

- Stead WW, Miller RA, Musen MA, and Hersh WR. Integration and beyond: linking information from disparate sources and into workflow. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000 Mar–. Apr;7. 2:135–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T. Portals lower cost and increase productivity. Plant Eng. 2002 Jan. 56(1):24–8. [Google Scholar]