ABSTRACT

Copper is an essential micronutrient used as a metal cofactor by a variety of enzymes, including cytochrome c oxidase (Cox). In all organisms from bacteria to humans, cellular availability and insertion of copper into target proteins are tightly controlled due to its toxicity. The major subunit of Cox contains a copper atom that is required for its catalytic activity. Previously, we identified CcoA (a member of major facilitator superfamily transporters) as a component required for cbb3-type Cox production in the Gram-negative, facultative phototroph Rhodobacter capsulatus. Here, first we demonstrate that CcoA is a cytoplasmic copper importer. Second, we show that bypass suppressors of a ccoA deletion mutant suppress cbb3-Cox deficiency by increasing cellular copper content and sensitivity. Third, we establish that these suppressors are single-base-pair insertion/deletions located in copA, encoding the major P1B-type ATP-dependent copper exporter (CopA) responsible for copper detoxification. A copA deletion alone has no effect on cbb3-Cox biogenesis in an otherwise wild-type background, even though it rescues the cbb3-Cox defect in the absence of CcoA and renders cells sensitive to copper. We conclude that a hitherto unknown functional interplay between the copper importer CcoA and the copper exporter CopA controls intracellular copper homeostasis required for cbb3-Cox production in bacteria like R. capsulatus.

IMPORTANCE

Copper (Cu) is an essential micronutrient required for many processes in the cell. It is found as a cofactor for heme-copper containing cytochrome c oxidase enzymes at the terminus of the respiratory chains of aerobic organisms by catalyzing reduction of dioxygen (O2) to water. Defects in the biogenesis and copper insertion into cytochrome c oxidases lead to mitochondrial diseases in humans. This work shows that a previously identified Cu transporter (CcoA) is a Cu importer and illustrates the link between two Cu transporters, the importer CcoA and the exporter CopA, required for Cu homeostasis and Cu trafficking to cytochrome c oxidase in the cell.

INTRODUCTION

Copper (Cu) is an essential transition metal required as a cofactor for many enzymes involved in various biological processes, including cellular energy production, protection against oxidative damage, iron acquisition, and nutritional immunity for restricting pathogen invasion (1, 2). The redox properties of Cu make it a suitable cofactor to carry out electron transfer reactions. However, these properties also render Cu toxic when present in excess amounts, as it can generate reactive oxygen species (e.g., ˙OH radicals) that damage cellular components (1, 3). It is thought that no free Cu is available in cells (4). Elaborate pathways with high-affinity and low-affinity transporters, metallochaperones, and specific assembly factors and transcriptional regulators handle Cu from its arrival into the cytoplasm to its insertion into cuproproteins (5).

In eukaryotes, the Ctr-type transporters are known to import Cu into the cytoplasm, and the P1B-type Cu-ATPases are important integral membrane proteins that hydrolyze ATP to extrude Cu out of the cytoplasm to maintain homeostasis. The Ctr-type Cu importers are found exclusively in eukaryotes but not in bacteria, whereas the P1B-type Cu-ATPases are major Cu exporters to control its toxicity in a wide range of organisms (6). In humans, defective P1B-type Cu-ATPases ATP7A and ATP7B lead to Menkes and Wilson’s diseases (7) and are associated with Alzheimer’s disease and resistance to chemotherapy (8, 9). Bacteria contain at least two kinds of P1B-type Cu-ATPases with different physiological roles in exporting Cu out of the cytoplasm (10, 11). Of these exporters, Pseudomonas aeruginosa CopA1 (CopA in Rhodobacter capsulatus) has a fast Cu efflux rate and is involved in Cu detoxification, whereas CopA2 (CcoI in R. capsulatus [12]) has a slow Cu efflux rate and is required for bacterial cytochrome c oxidase (Cox) biogenesis (10). R. capsulatus mutants lacking CcoI are unable to produce active Cox and are neither sensitive to, nor phenotypically corrected by, exogenous Cu2+ addition (12).

The enzymatic activity of Cox relies on its Cu cofactors (13, 14). Cox has a universally conserved binuclear center composed of Cu and iron of heme (heme-Cu center CuB) in subunit I. In addition, there are at least 2 or 3 additional subunits in bacterial aa3-type Cox and up to 13 subunits in mitochondrial aa3-type Cox (13). Subunit II of the aa3-type Cox harbors an additional binuclear Cu center (CuA) that acts as the primary electron acceptor. The facultative phototrophic Gram-negative bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus contains a single Cox of the cbb3-Cox type and has only the CuB (and no CuA) center (15). cbb3-Cox is composed of at least four subunits, encoded by the ccoNOQP operon. Of these subunits, CcoN contains the CuB center that is common to all heme-Cu oxidases (4, 13, 14).

Recently, we identified a novel gene (ccoA), which encodes a major facilitator superfamily (MFS) type transporter, and showed that its product (CcoA) is required for cbb3-Cox production in R. capsulatus (16). Mutants lacking CcoA contain less Cu than a wild-type strain and produce very small amounts of cbb3-Cox, unless supplemented with exogenous Cu2+ (~5 µM) (16). In this study, we show that the Cu uptake ability of a strain lacking CcoA is much lower than its isogenic wild-type parent and that a ccoA deletion mutant frequently acquires suppressor mutations that bypass the need for CcoA in cbb3-Cox production. These suppressor strains contain large amounts of cellular Cu and are hypersensitive to exogenous Cu2+ (Cus). Their molecular analyses by using the next-generation sequencing (NGS) and genome-wide comparisons with wild-type and ΔccoA strains identified single-base-pair insertion/deletion (indel) mutations in copA, which encodes the R. capsulatus P1B-type Cu-ATPase CopA (homologue of P. aeruginosa CopA1 [10]). These frameshift mutations occur at a hot spot formed of 10 consecutive cytosine base pairs and inactivate CopA. Construction of a genomic copA deletion mutation in the wild type and in ΔccoA backgrounds demonstrated that both the Cus phenotype and restoration of Cox production in the absence of CcoA are due to the inactivation of CopA. The Cus phenotype and increased cellular Cu amounts in the absence of CopA fully support a role of CopA in copper export (10). Restoration of the cbb3-Cox deficiency due to the absence of CcoA by the inactivation of CopA reveals a hitherto unknown link between two copper transport systems in bacteria. CcoA imports the required Cu, and CopA exports excess Cu via a cytoplasmic intermediate(s) to maintain cellular homeostasis and safe delivery of Cu to target cuproproteins such as Cox.

RESULTS

CcoA is a cytoplasmic Cu importer.

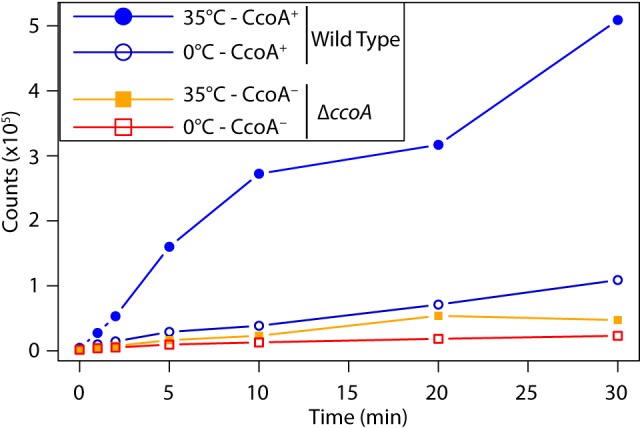

Previously we showed that a mutant lacking CcoA (ΔccoA mutant [strain SE8]) contained less cellular Cu than a wild-type strain and had almost no cbb3-Cox unless the growth medium was supplemented with micromolar amounts of Cu2+, pointing to a defect in Cu acquisition (16). Considering that CcoA is homologous to MFS-type transporters (16), which are well-established integral cytoplasmic membrane proteins, kinetics of radioactive 64Cu uptake by whole cells of a mutant lacking CcoA and its isogenic parental strain (MT1131) were examined (Fig. 1). Wild-type (MT1131) cells showed vigorous 64Cu uptake in a time-dependent manner at 35°C but not at 0°C, indicative of catalyzed 64Cu uptake. In contrast, under the same assay conditions, the ΔccoA mutant showed greatly reduced 64Cu uptake rates at both 35°C and 0°C. These data, together with our recent finding that R. capsulatus CcoA can complement the Cu import defect of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe Ctr-less mutant (17) establish that CcoA is a cytoplasmic Cu importer. Absence of CcoA abolishes Cu import required for normal cbb3-Cox production in R. capsulatus.

FIG 1 .

CcoA is required for 64Cu uptake in R. capsulatus. Radioactive 64Cu uptake assay by R. capsulatus cells was done as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were incubated for 10 min at 0°C or 35°C, 64Cu was added at time zero, and aliquots were taken at 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min, and accumulated cellular radioactivity (cpm/7 × 107 cells) was determined. Each assay was carried out at least three times using independently grown cells, and typical results are shown.

ΔccoA revertants are indel mutations in copA.

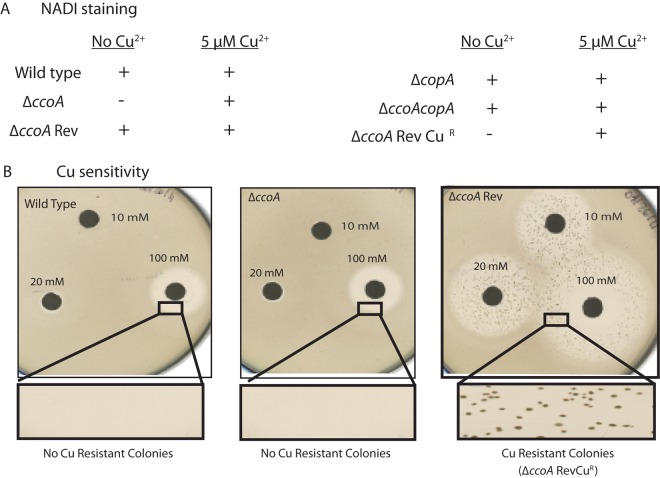

We observed earlier that ΔccoA mutants reverted frequently (~10−4) to regain the ability to produce cbb3-Cox activity (i.e., the Cox+/NADI+ phenotype) in the absence of Cu2+ supplementation (16) (Fig. 2A, left). These ΔccoARev revertants (SE8Ri, i = 1, 2, 3…) also became Cus and accumulated larger amounts of cellular Cu than a ΔccoA mutant or a wild-type strain in the presence and absence of Cu2+ supplementation (16) (Fig. 2B, right). Furthermore, upon growth in the presence of 5 µM Cu2+, their colony morphology on solid medium changed from typical R. capsulatus smooth (shiny/mucoid) to rough (dry/textured) colonies. In liquid medium, these cultures displayed a reddish color (unlike the usual green color of our laboratory wild-type R. capsulatus). Importantly, in these strains, the gain of Cox+/NADI+ and Cus phenotypes as well as increased cellular Cu contents occurred concomitantly, suggesting that the reversion mutation(s) affected cellular Cu homeostasis (16).

FIG 2 .

NADI/Cox and Cu2+ resistance or sensitivity phenotypes of R. capsulatus mutants. (A) NADI staining. Wild type (MT1131), ΔccoA (SE8), ΔccoARev (SE8R1or SE8R2), ΔcopA (SE24), ΔccoA ΔcopA (SE25), ΔccoARevCuR (SE8R1CuR or SE8R2CuR) strains were grown under aerobic respiratory conditions at 35°C on enriched MPYE medium (44) alone or supplemented with 5 µM CuSO4. NADI/Cox-positive (i.e., colonies turn blue immediately [<0.5 min] when exposed to NADI stain) and NADI/Cox-negative (i.e., colonies do not turn blue over a long period of time [over 10 min]) phenotypes are indicated with + and −, respectively. (B) Cu sensitivity. Cu2+ response phenotypes of wild-type R. capsulatus (MT1131), ΔccoA mutant (SE8), and its revertant ΔccoARev (SE8R1 or SE8R2) were determined by plate growth assays using filter paper disks (soaked in 10 mM, 20 mM, or 100 mM of Cu2+ solutions) placed on top of solidified top agar containing the appropriate strains.

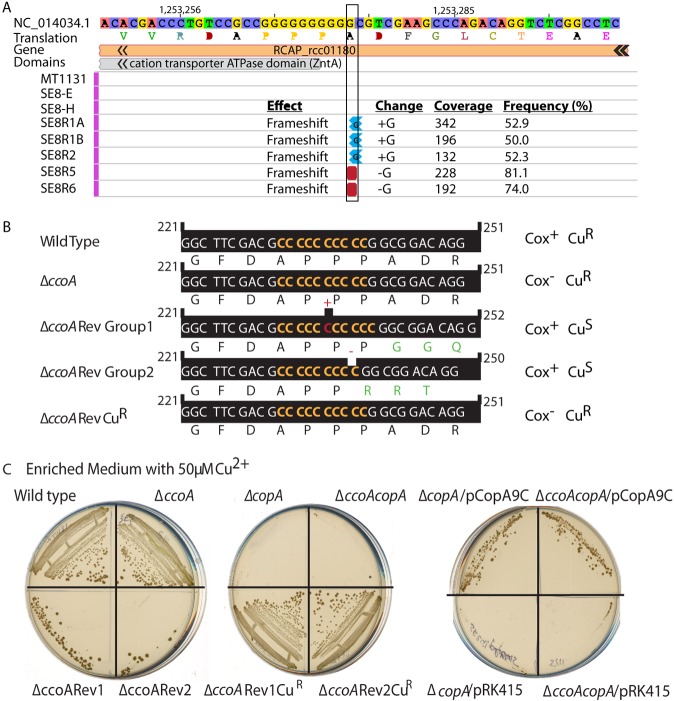

In order to uncover the molecular mechanism underlying the restoration of Cox+ activity in the ccoA revertants, we used next-generation sequencing (NGS) for a whole-genome comparison approach. As our ccoA mutant and its revertants were derived from our laboratory strain MT1131, the whole-genome sequence of MT1131 together with a ccoA mutant and four independent ccoA revertants (SE8R1, -2, -5, and -6) were determined and pairwise compared. High genome-wide coverage of analyzed samples (12 to 15 million 100-bp paired-end reads with ~300× coverage) allowed identification of candidate genes that differed from each other by a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Inclusion of two independent cultures of ΔccoA (strain SE8) and ΔccoARev1 (strain SE8R1) also monitored possible genome changes that could arise during strain construction and propagation. Strain MT1131 is thought to be derived from strain SB1003 (18) and carries a mutation inactivating the carotenoid biosynthesis gene crtD. Whole-genome sequence comparisons between strain MT1131 and the previously sequenced SB1003 strain (19) indeed defined the crtD121 mutation (C-to-T change at position 753,947 in crtD121 [RCC00683]) in R. capsulatus MT1131 and also revealed the presence of ~1,260-bp deletion (from positions 3,211,370 to 3,212,630) next to a transposase gene, as well as ~385 SNPs and indels across the whole genome (see Table S3 in the supplemental material and http://networks.systemsbiology.net/rcaps/). As expected, the genetically constructed deletion-insertion (starting at position 2,366,510) to knock out ccoA was present in SE8 and SE8Ri genomes. Pairwise comparison of the SNPs between all strains showed only one difference for SE8R2 (in the intergenic region upstream of RCC02563-hypothetical protein), SE8R5 (in RCC01565) and SE8R6 (in RCC01100) (Table S3). However, when the indels were compared, a single difference in the RCC01180 gene (at position 1,253,275) annotated as “copA, copper translocating P-type ATPase” was found between the wild type (MT1131) and the ΔccoA mutants (SE8E/SE8H) versus the ccoA revertants (SE8R1, -2, -5, and 6) (Fig. 3A). This indel corresponded to an addition of a single cytosine residue in SE8R1A/B and SE8R2 (copA11C ΔccoARev group 1), and a deletion of a single cytosine residue in SE8R5 and SE8R6 (copA9C ΔccoARev group 2), in the same stretch of 10 consecutive cytosine residues between base pairs 231 to 241 of RCC01180 (called copA hereafter) (Fig. 3B). PCR amplification of this region from the genomic DNA from appropriate strains combined with sequencing validated these findings and established that in all ΔccoA revertants, the copA11C-copA9C indel induced a frameshift mutation that inactivated the copA gene product (between amino acids at positions 78 to 81).

FIG 3 .

The ΔccoA revertants contain a single cytosine indel mutation in the copA gene that inactivates CopA protein. (A) NGS results show the R. capsulatus genome region that contains the RCC01180 (copA) gene encoding CopA. The strains are listed to the left. MT1131 is the wild-type strain. SE8-E and SE8-H are two different isolates of SE8 (ΔccoA). SE8R1A and SE8R1B are two different isolates of SE8R1 (ΔccoARev1). SE8R2 (ΔccoARev2), SE8R5 (ΔccoARev5), and SE8R6 (ΔccoARev6) strains are shown last. The whole genomes of the strains were sequenced and compared. The base pair changes and their effects and the related statistical data (coverage and frequency) are shown on the right. (B) The nucleotide sequence of copA between positions 221 and 251, together with the encoded amino acid sequence are shown for the wild type (MT1131), ΔccoA (SE8E or -H), ΔccoARev group 1 (SE8R1A or -B or SE8R2), ΔccoARev group 2 (SE8R5 or SER6) and ΔccoARev Cur (SE8R1CuR or SE8R2CuR) strains. The same sequence and reading frame are found in the wild-type, ΔccoA, and ΔccoARevCuR strains, which contain a wild-type copA allele with 10 consecutive cytosines. An insertion of one cytosine in ΔccoARev group 1 (e.g., SE8R1) and a deletion of one cytosine in ΔccoARev group 2 (e.g., SE8R5), resulting in 11 or 9 consecutive cytosines, respectively, and the frameshift mutations are also shown. (C) Cur and Cus phenotypes of wild-type (MT1131), ΔccoA (SE8), ΔcopA (SE24), ΔccoA ΔcopA (SE25), ΔccoARev1 (SE8R1), ΔccoARev2 (SE8R2), ΔccoARev1CuR (SE8R1CuR), and ΔccoARev2CuR (SE8R2CuR) strains were determined by their ability to grow on enriched MPYE medium supplemented with 50 µM CuSO4. Under these conditions, Cus strains are unable to form colonies. Among the Cus strains, the ΔccoARev1 (SE8R1) and ΔccoARev2 (SE8R2) strains frequently yield Cur derivatives, whereas ΔcopA (SE24) and ΔccoA ΔcopA (SE25) strains do not (compare the bottom of the left plate to the top of the middle plate). Similarly, the ΔcopA/pCopA9C and ΔcopA ΔccoA/pCopA9C strains yield Cur derivatives, whereas the same strains with a plasmid lacking a copA allele (pRK415) do not yield any Cur derivatives (right plate).

ΔccoA ΔcopA double mutants produce cbb3-Cox and are Cus.

A chromosomal deletion-insertion allele of copA (ΔcopA) was constructed to demonstrate that its inactivation restored the production of cbb3-Cox in a strain lacking ccoA. Introduction of this allele into the wild-type (MT1131) and ΔccoA (SE8) strains yielded ΔcopA (SE24) and ΔcopA ΔccoA (SE25) mutants, respectively. Like the ΔccoA revertants (SE8Ri), the ΔcopA ΔccoA double mutant (SE25) produced wild-type-like cbb3-Cox (determined by NADI staining [described under “Strains and culture conditions” in Materials and Methods]) on all media regardless of Cu2+ addition (Fig. 2A, right). It was also Cus to 50 µM CuSO4, an amount that does not affect the growth of a wild-type strain or a ΔccoA mutant (Fig. 3C, left). Moreover, introduction of a wild-type copy of copA carried by a transferable plasmid (pRK415_CopA) into a ΔcopA ΔccoA mutant (SE25) reversed its Cox+ and Cus phenotypes back to those (Cox− and Cur) of the ΔccoA mutant (SE8). Therefore, inactivation of CopA in the absence of CcoA restored the production of active cbb3-Cox at the expense of forfeiting cellular Cu tolerance.

ΔcopA single mutants are Cus but proficient for cbb3-Cox production.

An R. capsulatus ΔcopA mutant (SE24) produced wild-type-like cbb3-Cox but was as Cus as the ΔcopA ΔccoA double mutant (SE25) or the ΔccoA revertants (SE8Ri) (Fig. 3C). Thus, the Cus phenotype correlated with the absence of CopA. In agreement with this fact, complementation of a ccoA revertant (e.g., SE8R1) by a wild-type copy of ccoA (pSE3) also restored cbb3-Cox production but not its Cus phenotype (data not shown).

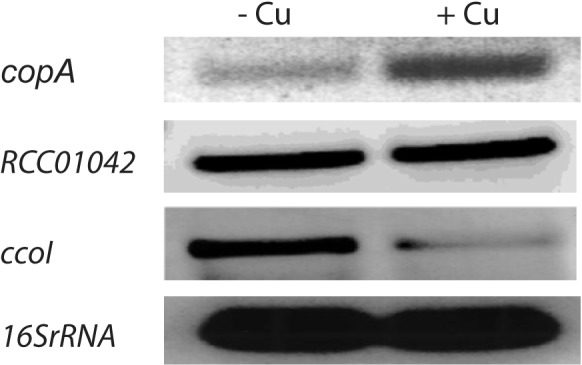

If CopA is indeed involved in Cu detoxification, then the expression of copA should respond to the addition of Cu2+, which was monitored by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). Total RNA was isolated from wild-type cells grown in enriched medium under respiratory conditions after incubation for 1 h with 1 µM CuSO4. RNA samples were probed via RT-PCR using copA- and 16S rRNA (control)-specific primers. Semiquantitative image analyses indicated that incubation with Cu2+ induced copA expression (~3- to 4-fold), in agreement with its role in Cu detoxification, while 16S rRNA levels remained unchanged (Fig. 4). For further control, the expression of two other R. capsulatus P1B-type ATPases, RCC01042 with an unknown role (see below) and ccoI required for cbb3-Cox production (12) were also analyzed in response to Cu2+ addition. While RCC01042 expression was unchanged, ccoI expression decreased (~2- to 3-fold) in response to Cu2+ addition.

FIG 4 .

Transcriptional response of copA, ccoI, and RCC01042 genes to Cu2+ supplementation. RT-PCR data using total RNA extracted from a wild-type R. capsulatus strain (MT1131) grown under respiratory conditions in MPYE medium not supplemented with CuSO4 (− Cu) or supplemented with 1 µM CuSO4 (+ Cu) are shown. copA (RCC01180), RCC01042, and ccoI expression are shown together with the 16S rRNA expression, which is unaffected by the addition of Cu2+. Note that copA expression is increased, whereas ccoI expression is decreased by Cu supplementation.

Cur derivatives of ΔccoA revertants switch back to wild-type copA and lose their ability to produce cbb3-Cox.

Upon exposure to exogenous Cu2+ (50 to 100 µM), spontaneous Cox+ ΔccoA revertants (SE8Ri) that carried the copA11C-copA9C indel mutations frequently yielded Cu-resistant (Cur) colonies that concomitantly lost their ability to produce cbb3-Cox (Fig. 2B, right). DNA sequence analysis of two such derivatives (SE8R1Cu100 and SE8R2Cu100) revealed that in these strains, the mutant copA11C allele reverted back to the wild type by deletion of one cytosine residue at the same 10-cytosine repeat where the initial indel inactivating copA was located (Fig. 3B). Similarly, exposure to 50 µM Cu2+ of the ΔcopA (SE24) and ΔcopA ΔccoA (SE25) strains harboring a plasmid with a mutant copA9C allele (pRK415_CopA9C) yielded Cur colonies (Fig. 3C, right). Sequencing of the plasmid-borne copA locus from these Cur colonies indicated that they switched back to a wild-type copA allele with the 10-cytosine repeat. Thus, the ΔccoA suppressors (SE8Ri) could switch back and forth between the Cox+ Cus and Cox− Cur phenotypes depending on growth conditions, indicating that CcoA-CopA interplay controls both cbb3-Cox production and Cu detoxification.

Other R. capsulatus paralogs of copA cannot substitute for its functions.

Besides copA and ccoI, three other genes (RCC01042, RCC02064, and RCC02190) in the R. capsulatus genome are annotated as “copper or heavy metal translocating P-type ATPase.” Their subgrouping based on ion selectivity determinants (20) suggested that RCC02190 and RCC02064 are not involved in Cu transport (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). RCC01042 could not be placed readily in any P1B subgroup, even though it is annotated as a “copper-translocating P-type ATPase copA.” Its role was probed by constructing an insertion-deletion allele ΔRCC01042, which was introduced into the wild-type (MT1131) and ΔccoA (SE8) strains to obtain SE26 and SE27, respectively. A mutant lacking RRC01042 (ΔRCC01042 [SE26]) had no effect on Cus or Cox+ phenotypes. Moreover, the ΔccoA ΔRCC02190 (SE31), ΔccoA ΔRCC01042 (SE27), and ΔccoA ΔccoI (SE13) double mutants were Cur and Cox−, indicating that none of these P1B-type ATPases could functionally substitute for copA to suppress the cbb3-Cox defect due to the absence of CcoA. We concluded that R. capsulatus contained only one CopA (i.e., RCC01180), which is involved in Cu detoxification, and also in cbb3-Cox production when CcoA was absent.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we identified the MFS-type cytoplasmic membrane transporter CcoA as a component required for cbb3-Cox production and showed that cellular Cu content decreased in its absence (16). Our findings indicated that CcoA is involved in Cu transport and trafficking into cbb3-Cox. In this work, we obtained direct evidence by monitoring cellular 64Cu uptake that the absence of CcoA affects Cu acquisition by R. capsulatus cells. We have also shown recently that R. capsulatus CcoA can complement the Cu import defect of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe Ctr-less mutant (17). Together, these data establish that CcoA is a cytoplasmic Cu importer. In a wild-type strain, 64Cu uptake occurred more efficiently at a higher temperature (35°C versus 0°C), suggesting that CcoA-mediated Cu import may be energy dependent, which is consistent with the properties of MFS-type transporters (21).

The molecular basis of the ΔccoA bypass suppressors was sought to gain insight into the link(s) between CcoA-mediated Cu import and cbb3-Cox production. Initially, we used a genetic approach by constructing genomic libraries and transferring them into appropriate strains (ΔccoA and ΔccoARev), as done earlier (16). In this case, screening for transconjugants with expected Cox phenotypes to identify the suppressors was greatly hampered by the high frequency of spontaneous suppressors of ΔccoA. To circumvent this difficulty, we used NGS technology-based whole-genome comparisons. In all cases examined, we found that ΔccoA suppression was due to single-base-pair indel mutations located in a hot spot of consecutive 10 cytosines. The frameshift mutations located between amino acids at positions 78 to 81 of CopA inactivated this Cu exporter and rendered cells Cus. Interestingly, upon exposure to external Cu2+, this same hot spot switched back to the wild type, reactivating CopA and rendering cells Cur but abolishing cbb3-Cox production. Stretches of identical nucleotide repeats form mutational hot spots due to errors in DNA replication, referred to as “DNA polymerase slippage” (22–24), which frequently generates indels during the replication of repeats (25). In R. capsulatus, there are two repeats of 10 cytosines in copA and in hemolysin d (RCC03392), as well as one repeat of 12 cytosines in RCC03033 encoding a formate dehydrogenase subunit. It is currently unknown whether the occurrence of such repeats has any physiological role by forming hot spots for reversible activation/inactivation of genes via DNA polymerase slippage. Conceivably, the lack of cbb3-Cox production due to the absence of CcoA could provide a selective advantage (e.g., in the natural habitat of R. capsulatus, the cbb3-Cox activity is critical for anoxygenic photosynthesis) for inactivation of CopA at the expense of Cus. Similarly, elevated levels of external Cu could confer a selective advantage for reactivation of CopA to restore Cu tolerance when CcoA is inactive. Any link between the occurrence of these indels and the growth fitness due to cbb3-Cox activity or the presence of Cu remains to be seen.

Suppression of the cbb3-Cox deficiency induced by the absence of CcoA via the inactivation of the P1B-type ATPase copA at the expense of rendering cells Cus is novel. CopA homologues are integral membrane proteins that export Cu from the cytoplasm to the periplasm and play a major role against Cu toxicity (6). R. capsulatus CopA is 806 amino acids long, is predicted to form eight transmembrane helices, with an essential CPC motif in its sixth transmembrane helix and three (A, P, and N) domains common to all P-type ATPases. As observed in Bradyrhizobium japonicum (26) and P. aeruginosa (10), inactivation of R. capsulatus copA also rendered cells Cus without affecting cbb3-Cox production. Thus, the Cus phenotype of the ΔccoA suppressors originated from the inactivation of CopA, which establishes for the first time that CopA is indirectly involved in cbb3-Cox production when cells face cytoplasmic Cu shortage due to the absence of CcoA activity.

P1B-type ATPases are divided into five subgroups based on their ion selectivity determinants (20), with the R. capsulatus genome containing five such transporters (RCC01180, RCC01042, RCC01163, RCC02064, and RCC02190). CopA (RCC01180) has the MXXSS motif specific for the P1B-1-type subgroup for Cu+/Ag+, whereas CcoI (RCC01163) has the MSTS motif specific for the P1B-3-type subgroup for Cu2+/Cu+/Ag+ in their eight transmembrane helices (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Whether these structural differences between CopA and CcoI are the basis of their different efflux rates and whether the substrate redox states (20) are related to their physiological roles in Cu detoxification and cbb3-Cox production is unknown. Of the remaining R. capsulatus P1B-type ATPases, RCC02190 belongs to the P1B-2 subgroup involved in transporting Zn2+/Cd2+/Pb2+, and RCC02064 shows the characteristics of the P1B-4 subgroup that transports Co2+. RCC01042 cannot be placed readily in any P1B subgroup. The data obtained in this work with RCC01042, and previously with RCC02190 (16), indicate that these transporters are not involved in Cu homeostasis or cbb3-Cox production in R. capsulatus.

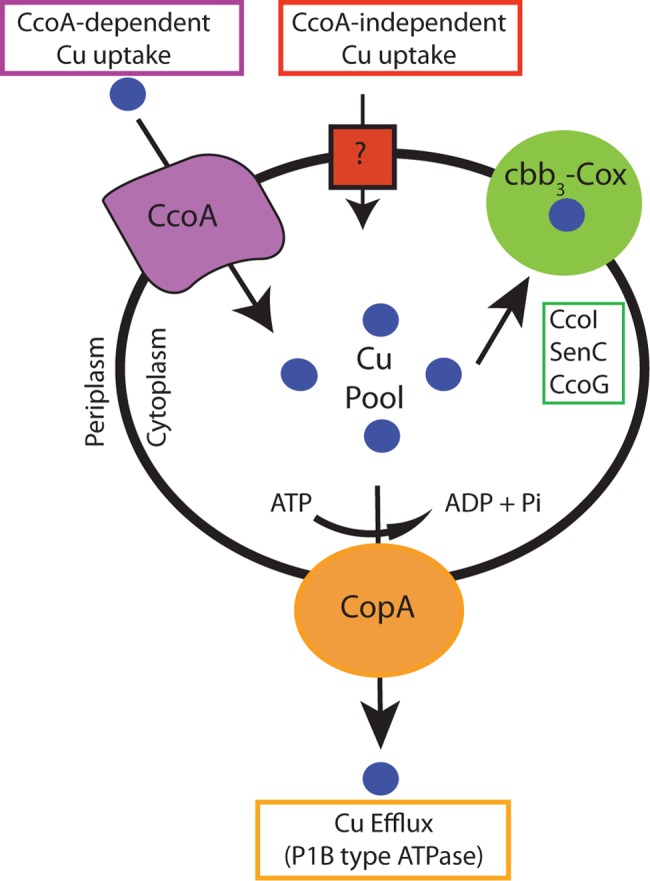

A major finding of this study is the functional interplay between CcoA and CopA that indirectly controls cbb3-Cox production via cellular Cu homeostasis. Assuming that CcoA and CopA proteins are unlikely to interact physically, their interplay may be via a cytoplasmic Cu pool, which is replenished by CcoA and depleted by CopA (Fig. 5). Accordingly, a decrease in the size of this pool due to the absence of CcoA would render cells unable to produce cbb3-Cox, whereas its increase due to the absence of CopA would restore cbb3-Cox production while forfeiting a major Cu detoxification mechanism. These predictions are in agreement with our findings that homeostasis of the cytoplasmic Cu pool via the CcoA-CopA interplay is critical for growth fitness (i.e., cbb3-Cox production) and survival (i.e., Cu toxicity) of bacterial cells (Fig. 5).

FIG 5 .

Model for Cu trafficking in R. capsulatus. The MFS-type transporter CcoA is required for high-affinity import into the cytoplasm of exogenous Cu, which is then delivered and inserted into cbb3-Cox with the help of CcoI (the low-efflux P1B-type Cu ATPase), SenC, and CcoG. CopA (the high-efflux P1B-type Cu ATPase) extrudes Cu from the cytoplasm to the periplasm to avoid toxicity. A low-affinity Cu uptake system (indicated by ?) of unknown molecular nature is postulated to provide Cu to cbb3-Cox in the absence of CcoA and in the presence of a high level (e.g., 5 µM) of exogenous Cu2+. In a wild-type cell, the interplay between CcoA and CopA is proposed to occur via a cytoplasmic Cu pool to maintain cellular Cu homeostasis and efficient cbb3-Cox production.

Earlier, the occurrence of a Cu pool in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast and mouse mitochondrial matrix was described. Cu is liganded to a nonproteinaceous small molecule (CuL) (27) required for Cox biogenesis (28). The non-Cu-liganded form of this molecule (apoCuL) was also seen in the cytoplasm of these eukaryotic cells. These findings suggested that Cu-loaded CuL might be imported into the matrix via an inner membrane transporter in mitochondria (29). Somewhat similarly, a Cu chelator (CuL1) to neutralize Cu toxicity is excreted by some marine cyanobacteria (30). However, neither the chemical nature(s) of the mitochondrial or cyanobacterial CuL nor their roles in Cu acquisition are clear. So far, the methanobactins produced by methanotrophs are the only known small molecules involved in cellular Cu uptake (31). Recently, active-transport-dependent uptake of a Cu-methanobactin complex was shown in Methylosinus trichosporium, but how this process occurs is not yet known (31). MFS-type transporters are known to deliver iron-chelating siderophores (32, 33), which are reminiscent of methanobactins. Whether R. capsulatus produces a chalcophore is unknown, but the possibility that CcoA could import such a molecule into the cytoplasm is enticing. Finally, if a cytoplasmic Cu pool exists in R. capsulatus (Fig. 5), then how Cu is trafficked from this pool to CopA for detoxification and to CcoI for cbb3-Cox production needs further studies.

In bacteria, Cu efflux proteins are mostly well identified and characterized, but less is known about Cu importers (34, 35). It has been thought for a long time that cells would not import Cu because of its toxic nature. However, well-conserved high-affinity (i.e., Ctr1/3) and low-affinity (i.e., Fet4/Smf1) Cu transporters exist in eukaryotes (36, 37). The Ctr-type high-affinity transporters located in the plasma membrane are well studied, but no such transporter has been identified in bacteria. Furthermore, how Cu is imported into the mitochondria is also not known (29, 38). Indeed, our work demonstrates that CcoA is the first example of a bacterial MFS-type transporter that imports Cu (16). Whether similar Cu importers also exist in other bacteria and may be involved in the biogenesis of various Cox proteins and other cuproproteins is unknown. Currently, the only other known MFS-type Cu transporter is Mfc1 located in the forespore membranes of Schizosaccharomyces pombe yeast (39). Excitingly, recent heterologous expression of R. capsulatus CcoA in S. pombe lacking its own Ctr-type Cu importers showed that CcoA is functionally similar to these transporters in respect to their cytoplasmic Cu import ability (17).

In summary, this work provides the first identification of a homeostatic interplay between the Cu importer CcoA and the Cu exporter CopA that occurs in bacteria via a cytoplasmic Cu pool of vital importance for both Cu detoxification and biogenesis of major cuproproteins like Cox. Future studies addressing the chemical nature of this pool and the contributing partners trafficking Cu to cellular targets will be invaluable for our understanding of Cu homeostasis in bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

R. capsulatus strains (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were grown on enriched medium (MPYE) (44), or Sistrom’s minimal medium A, supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (spectinomycin [Spe], 10 µg ml−1; kanamycin [Kan], 10 µg ml−1; rifampin [Rif], 70 µg ml−1; tetracycline [Tet], 2.5 µg ml−1) at 35°C chemoheterotrophically (aerobic respiration) or photoheterotropically (anaerobic photosynthesis) in anaerobic jars with H2- plus CO2-generating gas packs (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, MD) (40). As needed, the MPYE medium was supplemented with desired amounts of CuSO4. Escherichia coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin [Amp], 100 µg ml−1; Spe, 50 µg ml−1; Kan, 50 µg ml−1; Tet, 12.5 µg ml−1) as described earlier (40). Colonies producing an active Cox enzyme (Cox+) were revealed via NADI staining prepared by mixing at a 1:1 (vol/vol) ratio 35 mM α-naphthol and 30 mM N,N,N′,N′-dimethyl-p-phenylene diamine (DMPD) dissolved in ethanol and water, respectively (41).

Molecular genetic techniques.

Standard molecular genetic techniques were performed as described previously (42). The gene transfer agent (GTA) (43) of R. capsulatus was used to construct chromosomal knockout alleles of desired genes as described earlier (44). Genomic DNA was extracted from 10-ml cultures of the wild type (MT1131), ΔccoA mutant (SE8), and its Cox+ revertants (SE8Ri with i = 1 to 6) that were grown in MPYE medium by using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen Inc.). The quality and quantity of the isolated genomic DNA were analyzed by using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer and by agarose gel electrophoresis prior to library preparations for NGS.

To construct a deletion-insertion allele of copA (R. capsulatus RCC01180, initially annotated as copA), a DNA fragment encompassing ~500 bp 5′ upstream and 3′ downstream of copA, including its promoter region, was PCR amplified using wild-type (MT1131) chromosomal DNA as a template, and the primers CopAFwd (Fwd stands for forward) and CopARev (Rev stands for reverse) containing 5′ SacI and 3′ KpnI sites, respectively (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). This DNA fragment was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes and cloned into the respective sites of pBluescript II-KS+ and pRK415 to yield the plasmids pBS_CopA and pRK415_CopA, respectively (Table S1). Starting with pBS_CopA, ~1,100 bp of copA was deleted by using the primers CopAdelfwd2 (del stands for deletion) and CopAdelrev2 (Table S2), which amplified the remaining flanking regions of copA and the vector. A Kanr cassette from plasmid pKD4 (45) was ligated between the two flanking regions of copA to yield pBS_ΔcopA carrying the Δ(copA::kan) allele. The SacI-KpnI fragment of pBS_ΔcopA was cloned into the respective sites of plasmid pRK415 to yield pRK415_ΔcopA. The latter plasmid was used to obtain the ΔcopA knockout mutants SE24 and SE25 by GTA crosses with the wild type (MT1131) and a ΔccoA (SE8) mutant, respectively, as the recipients (Table S1).

To construct a deletion-insertion allele of R. capsulatus copA paralog RCC01042 (initially also annotated as copA), a DNA fragment encompassing this open reading frame, including its promoter region, was PCR amplified using the primers RCC01042Fwd and RCC01042Rev (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) and cloned into the SacI and KpnI sites of pBluescript II-KS+ and pRK415 as described above, yielding plasmids pBS_CopA1 and pRK415_CopA1. Starting with pBS_CopA1, a knockout allele Δ(RCC01042::gen) was constructed as described above, by deleting the ~1100 bp of RCC01042 using primers RCC01042delF and RCC01042delR (Table S2) and ligating a gentamicin resistance cassette, which was PCR amplified from R. capsulatus B10S-T7 strain (46), between the two flanking regions of RCC01042 to obtain pBS_ΔRCC01042. The SacI-KpnI DNA fragment of pBS_ΔRCC01042 was cloned into pRK415 to yield pRK415_RCC01042, which was used to construct the SE26 and SE27 mutants by GTA crosses with the wild-type (MT1131) and ΔccoA (SE8) strains, respectively, as the recipients (Table S1).

RT-PCR analyses.

For reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses, appropriate R. capsulatus strains were grown in MPYE medium to mid-log phase (optical density at 685 nm [OD685] of 0.8 to 1.0). An amount of culture corresponding to ~109 cells was centrifuged, and the cells were incubated in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 mM EDTA [pH 7.0]) containing 10 mg/ml lysozyme for 15 min at 37°C and passed five times through a 0.8-mm needle into RNase-free tubes. Total RNA was isolated using the GE Healthcare Mini Spin kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two to five micrograms of total RNA was treated with DNase I for 30 min at 25°C in the presence of RNase inhibitor RNasin. Fifty to 200 ng of DNA and RNase-free RNA was used for RT-PCR reaction with the OneStep RT-PCR Qiagen kit. A 25-µl total reaction mixture volume consisted of 5 µl reaction buffer, 1 µl deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.1 nmol of each appropriate primer (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), and 1 µl of enzyme mix (reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase) and water up to 25 µl. Similar PCR reactions with the same primers and RNA amounts were performed as controls for the absence of genomic DNA contamination by using the PHUSION PCR kit (NEB Inc., MA), and samples were analyzed using a 1.2% agarose gel.

Cu2+ sensitivity assays.

Strains to be tested for their Cu sensitivity were grown to exponential phase (OD630 of ~0.5) in enriched MPYE medium under respiratory growth conditions. Approximately 2 × 107 cells were mixed with 4 ml MPYE medium containing 0.7% top agar and poured on top of 10-ml MPYE plates. After solidification of agar, Whatman 3MM paper disks (3-mm diameter) soaked with 8 µl of the desired concentrations of CuSO4 solutions were placed on agar surfaces. The plates were incubated for 2 days at 35°C under respiratory growth conditions and scanned. CuSO4 toxicity responses of the strains were determined by measuring the size of growth incubation zones around the Cu2+-containing paper disks (16).

Radioactive 64Cu uptake assay.

Cu uptake by whole cells was measured using radioactive 64Cu obtained from Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University Medical School (effective specific activity [ESA] of ~1.84 × 104 mCi/µmol at noon of the shipping day; half-life, ~12 h). Appropriate strains were grown overnight in 15 ml MPYE medium and harvested at mid-exponential or late exponential phase (OD630 of ~0.6 to 0.8), centrifuged, washed once with 5 ml fresh MPYE medium, and resuspended in ~1 ml. The total numbers of cells were determined spectrophotometrically (1 OD630 unit = 7.5 × 108 cells/ml), and all cultures were normalized to the same number of cells per milliliter of MPYE medium. The 64Cu uptake assay mixture contained ~7 × 108 cells (added as ~100 to 200 µl of MPYE medium), a volume of 64Cu corresponding to a total of ~107 cpm, and completed to a total volume of 500 µl with citrate buffer (50 mM sodium citrate, 5% glucose [pH 6.5]). One set was incubated at 0°C in an ice bath, and another set was incubated at 35°C in a water bath. The uptake reaction was started by the addition of a volume of 64CuCl2 corresponding to ~107 cpm determined immediately before use. At each time point (0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min), 50-µl aliquots were transferred to ice-cold Eppendorf tubes containing 50 µl of 1 mM CuCl2 and 50 µl of 50 mM EDTA (pH 6.5) to terminate the uptake reaction. Samples were kept on ice until the end of the assay and centrifuged for 3 min at 10,000 rpm, supernatants were discarded, and pellets were washed twice with 100 µl of ice-cold 50 mM EDTA solution, resuspended in 1 ml scintillation liquid, and counted by using a scintillation counter with a wide open window.

Next-generation genome sequencing and analysis.

The NGS of the genomes of eight R. capsulatus strains, the wild type (MT1131), two independent isolates of a ΔccoA mutant (SE8H and SE8E), and four ΔccoA revertant (two independent isolates of SE8R1 [SE8R1A and SE8R1B], SE8R2, SE8R5, SE8R6) mutants (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) was performed by Covance Genomics Laboratory LLC, Seattle, WA. The use of multiple replicates of the same strains in our experimental design allowed ready accounting of both experimental artifacts and biological variability that otherwise could significantly affect final analyses. Genomic DNA was sheared by using a Covaris Adaptive Focused Acoustics system (Covaris, Woburn, MA), and genomic DNA libraries with insert size between 200 and 300 bp were prepared by using Illumina TrueSeq DNA sample prep kit for paired-end sequencing, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina Inc.). The resulting genomic DNA libraries were sequenced by using an Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencing machine to yield 12 to 15 million reads of 100-bp lengths. All reads were aligned to the R. capsulatus SB1003 reference genome (GenBank accession no. CP001312.1 and CP001313.1) by using the bow tie alignment algorithm (47), and SNP and indels were identified by using SAMtools (48). Illumina standard quality check and filtering conditions were used. Sequence reads obtained with the laboratory wild-type strain MT1131 were aligned against the R. capsulatus SB1003 reference genome, and the SNPs and indels that it contained were defined (Table S3). Then, the sequence reads obtained with the ΔccoA mutants (SE8E and SE8H) and revertants (SE8R1A, SE8R1B, SE8R2, SE8R5, and SE8R6) were aligned against the reference genome, and they were also compared with MT1131 sequence reads to define the SNPs and indels that all strains contained using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software (49). All NGS analyses, whole-genome comparisons, and defined SNP and indel data are available at http://networks.systemsbiology.net/rcaps/.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Strains and plasmids used in this work.

Primers used in this work, including those used to sequence the genomic copA allele.

SNPs in R. capsulatus strain MT1131 compared to reference strain SB1003.

R. capsulatus P1B-type ATPases and their roles in Cu toxicity and cbb3-Cox production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy through grant DE-FG02-91ER20052 and NIH GM 38237 to F.D. and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG-GRK1478 to H.G.K. and DFG-FOR 929 to H.G.K.) and from the German-French-University (DFH) PhD College on “Membranes and Membrane Proteins” grants to H.G.K.

Footnotes

Citation Ekici S, Turkarslan S, Pawlik G, Dancis A, Baliga NS, Koch H-G, Daldal F. 2014. Intracytoplasmic copper homeostasis controls cytochrome c oxidase production. mBio 5(1):e01055-13. doi:10.1128/mBio.01055-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Banci L, Bertini I, McGreevy KS, Rosato A. 2010. Molecular recognition in copper trafficking. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27:695–710. 10.1039/b906678k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Samanovic MI, Ding C, Thiele DJ, Darwin KH. 2012. Copper in microbial pathogenesis: meddling with the metal. Cell Host Microbe 11:106–115. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Macomber L, Imlay JA. 2009. The iron-sulfur clusters of dehydratases are primary intracellular targets of copper toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:8344–8349. 10.1073/pnas.0812808106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rae TD, Schmidt PJ, Pufahl RA, Culotta VC, O’Halloran TV. 1999. Undetectable intracellular free copper: the requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science 284:805–808. 10.1126/science.284.5415.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luk E, Jensen LT, Culotta VC. 2003. The many highways for intracellular trafficking of metals. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 8:803–809. 10.1007/s00775-003-0482-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Argüello JM, Eren E, González-Guerrero M. 2007. The structure and function of heavy metal transport P1B-ATPases. Biometals 20:233–248. 10.1007/s10534-006-9055-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Bie P, Muller P, Wijmenga C, Klomp LW. 2007. Molecular pathogenesis of Wilson and Menkes disease: correlation of mutations with molecular defects and disease phenotypes. J. Med. Genet. 44:673–688. 10.1136/jmg.2007.052746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zheng Z, White C, Lee J, Peterson TS, Bush AI, Sun GY, Weisman GA, Petris MJ. 2010. Altered microglial copper homeostasis in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 114:1630–1638. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06888.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leonhardt K, Gebhardt R, Mössner J, Lutsenko S, Huster D. 2009. Functional interactions of Cu-ATPase ATP7B with cisplatin and the role of ATP7B in the resistance of cells to the drug. J. Biol. Chem. 284:7793–7802. 10.1074/jbc.M805145200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. González-Guerrero M, Raimunda D, Cheng X, Argüello JM. 2010. Distinct functional roles of homologous Cu+ efflux ATPases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 78:1246–1258. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07402.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raimunda D, González-Guerrero M, Leeber BW, III, Argüello JM. 2011. The transport mechanism of bacterial Cu+-ATPases: distinct efflux rates adapted to different function. Biometals 24:467–475. 10.1007/s10534-010-9404-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koch HG, Winterstein C, Saribas AS, Alben JO, Daldal F. 2000. Roles of the ccoGHIS gene products in the biogenesis of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase. J. Mol. Biol. 297:49–65. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pereira MM, Sousa FL, Veríssimo AF, Teixeira M. 2008. Looking for the minimum common denominator in haem-copper oxygen reductases: towards a unified catalytic mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777:929–934. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cobine PA, Pierrel F, Winge DR. 2006. Copper trafficking to the mitochondrion and assembly of copper metalloenzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763:759–772. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gray KA, Grooms M, Myllykallio H, Moomaw C, Slaughter C, Daldal F. 1994. Rhodobacter capsulatus contains a novel cb-type cytochrome c oxidase without a CuA center. Biochemistry 33:3120–3127. 10.1021/bi00176a047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ekici S, Yang H, Koch HG, Daldal F. 2012. Novel transporter required for biogenesis of cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase in Rhodobacter capsulatus. mBio 3(1):293–311. 10.1128/mBio.00293-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beaudoin J, Ekici S, Daldal F, Ait-Mohand S, Guérin B, Labbé S. 2013. Copper transport and regulation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41:1679–1686. 10.1042/BST2013089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zannoni D, Prince RC, Dutton PL, Marrs BL. 1980. Isolation and characterization of a cytochrome c2-deficient mutant of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. FEBS Lett. 113:289–293. 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80611-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strnad H, Lapidus A, Paces J, Ulbrich P, Vlcek C, Paces V, Haselkorn R. 2010. Complete genome sequence of the photosynthetic purple nonsulfur bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus SB 1003. J. Bacteriol. 192:3545–3546. 10.1128/JB.00366-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Argüello JM. 2003. Identification of ion-selectivity determinants in heavy-metal transport P1B-type ATPases. J. Membr. Biol. 195:93–108. 10.1007/s00232-003-2048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reddy VS, Shlykov MA, Castillo R, Sun EI, Saier MH., Jr. 2012. The major facilitator superfamily (MFS) revisited. FEBS J. 279:2022–2035. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08588.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baumann B, Potash MJ, Köhler G. 1985. Consequences of frameshift mutations at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus of the mouse. EMBO J. 4:351–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Strauss BS. 1999. Frameshift mutation, microsatellites and mismatch repair. Mutat. Res. 437:195–203. 10.1016/S1383-5742(99)00066-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Streisinger G, Owen J. 1985. Mechanisms of spontaneous and induced frameshift mutation in bacteriophage T4. Genetics 109:633–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dieringer D, Schlötterer C. 2003. Two distinct modes of microsatellite mutation processes: evidence from the complete genomic sequences of nine species. Genome Res. 13:2242–2251. 10.1101/gr.1416703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Preisig O, Zufferey R, Hennecke H. 1996. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum fixGHIS genes are required for the formation of the high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase. Arch. Microbiol. 165:297–305. 10.1007/s002030050330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cobine PA, Ojeda LD, Rigby KM, Winge DR. 2004. Yeast contain a non-proteinaceous pool of copper in the mitochondrial matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 279:14447–14455. 10.1074/jbc.M312693200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cobine PA, Pierrel F, Bestwick ML, Winge DR. 2006. Mitochondrial matrix copper complex used in metallation of cytochrome oxidase and superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 281:36552–36559. 10.1074/jbc.M606839200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vest KE, Leary SC, Winge DR, Cobine PA. 2013. Copper import into the mitochondrial matrix in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is mediated by Pic2, a mitochondrial carrier family protein. J. Biol. Chem. 288:23884–23892. 10.1074/jbc.M113.470674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moffett JW, Brand LE. 1996. Production of strong, extracellular Cu chelators by marine cyanobacteria in response to Cu stress. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41:388–395. 10.4319/lo.1996.41.3.0388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Balasubramanian R, Kenney GE, Rosenzweig AC. 2011. Dual pathways for copper uptake by methanotrophic bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 286:37313–37319. 10.1074/jbc.M111.284984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Franza T, Mahé B, Expert D. 2005. Erwinia chrysanthemi requires a second iron transport route dependent of the siderophore achromobactin for extracellular growth and plant infection. Mol. Microbiol. 55:261–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Furrer JL, Sanders DN, Hook-Barnard IG, McIntosh MA. 2002. Export of the siderophore enterobactin in Escherichia coli: involvement of a 43 kDa membrane exporter. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1225–1234. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02885.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hood MI, Skaar EP. 2012. Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:525–537. 10.1038/nrmicro2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim BE, Nevitt T, Thiele DJ. 2008. Mechanisms for copper acquisition, distribution and regulation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4:176–185. 10.1038/nchembio.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dancis A, Haile D, Yuan DS, Klausner RD. 1994. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae copper transport protein (Ctr1p). Biochemical characterization, regulation by copper, and physiologic role in copper uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 269:25660–25667 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu XF, Culotta VC. 1999. Mutational analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Smf1p, a member of the Nramp family of metal transporters. J. Mol. Biol. 289:885–891. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Festa RA, Thiele DJ. 2011. Copper: an essential metal in biology. Curr. Biol. 21:877–883. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beaudoin J, Ioannoni R, López-Maury L, Bähler J, Ait-Mohand S, Guérin B, Dodani SC, Chang CJ, Labbé S. 2011. Mfc1 is a novel forespore membrane copper transporter in meiotic and sporulating cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286:34356–34372. 10.1074/jbc.M111.280396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jenney FE, Jr, Daldal F. 1993. A novel membrane-associated c-type cytochrome, cyt cy, can mediate the photosynthetic growth of Rhodobacter capsulatus and Rhodobacter sphaeroides. EMBO J. 12:1283–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marrs B, Gest H. 1973. Genetic mutations affecting the respiratory electron-transport system of the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Bacteriol. 114:1045–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yen HC, Hu NT, Marrs BL. 1979. Characterization of the gene transfer agent made by an overproducer mutant of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Mol. Biol. 131:157–168. 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90071-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Daldal F, Cheng S, Applebaum J, Davidson E, Prince RC. 1986. Cytochrome c2 is not essential for photosynthetic growth of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:2012–2016. 10.1073/pnas.83.7.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Myllykallio H, Zannoni D, Daldal F. 1999. The membrane-attached electron carrier cytochrome cy from Rhodobacter sphaeroides is functional in respiratory but not in photosynthetic electron transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:4348–4353. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Katzke N, Arvani S, Bergmann R, Circolone F, Markert A, Svensson V, Jaeger KE, Heck A, Drepper T. 2010. A novel T7 RNA polymerase dependent expression system for high-level protein production in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. Protein Expr. Purif. 69:137–146. 10.1016/j.pep.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10:R25. 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup 2009. The Sequence Alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29:24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Strains and plasmids used in this work.

Primers used in this work, including those used to sequence the genomic copA allele.

SNPs in R. capsulatus strain MT1131 compared to reference strain SB1003.

R. capsulatus P1B-type ATPases and their roles in Cu toxicity and cbb3-Cox production.