Abstract

Nanomedicine results from nanotechnology where molecular scale minute precise nanomotors can be used to treat disease conditions. Many such biological nanomotors are found and operate in living systems which could be used for therapeutic purposes. The question is how to build nanomachines that are compatible with living systems and can safely operate inside the body? Here we propose that it is of paramount importance to have a workable base model for the development of nanomotors in nanomedicine usage. The base model must placate not only the basic requirements of size, number, and speed but also must have the provisions of molecular modulations. Universal occurrence and catalytic site molecular modulation capabilities are of vital importance for being a perfect base model. In this review we will provide a detailed discussion on ATP synthase as one of the most suitable base models in the development of nanomotors. We will also describe how the capabilities of molecular modulation can improve catalytic and motor function of the enzyme to generate a catalytically improved and controllable ATP synthase which in turn will help in building a superior nanomotor. For comparison, several other biological nanomotors will be described as well as their applications for nanotechnology.

1. Introduction

Biological motors are molecular machines found in living systems. These nanomachines are designed to carry out specific functions. In order to perform their designated jobs they use energy and convert it to mechanical work. The majority of protein based molecular nanomotors use chemical energy ATP to perform mechanical work [1]. Molecular size nanomotors are commonly divided into two categories: (I) biological and (II) nonbiological. In this review we will focus on biological nanomotors, particularly ATP synthase. Biological nanomotors are incredible molecular machines which drive fundamental processes of life. In addition to F1F0 ATP synthase bacterial flagella, kinesin, dynein, myosin, actin, microtubule, dynamin, RNA polymerase, DNA polymerase, helicases, topoisomerases, and viral DNA packaging motors are some other prominent biological nanomotors.

In recent years many laboratories [2–10] have been trying to create synthetic or nonbiological nanomotors, which is not the topic of this review. However, before discussing the biological nanomotors it would be helpful to briefly go over nonbiological nanomotors too. The purpose of creating nonbiological nanomotors by mimicking the biological nanomotors is to get the desired physiological function done within the living systems. Interestingly, the nonnatural nanodevices generally happen to be less efficient compared to their biological counterparts. Scientists in the field of nanotechnology are continuously reconnoitering the possibility of creating molecular motors de novo. These synthetic molecular motors currently suffer many limitations that confine their use to the research laboratory only. However, many of these deficiencies can easily be dealt with comprehensive knowledge of known biological nanomotors. Thus, the answer to the valid question of how to manage the functional capabilities of the nanomotors which could be used inside the living system can be found in the naturally occurring biological nanomotors. In this review we advocate that it is of paramount importance to have a base model in order to develop nanomotors for nanomedicine usage. We also suggest that ATP synthase best exemplifies the nanomotor for a right size base model.

2. F1F0 ATP Synthase

Among all known biological nanomotors, ATP synthase stands alone for being the universal nanomotor found in all living systems from bacteria to man. Ability of molecular modifications of ATP synthase catalytic sites is of additional advantage. In order to synthesize ATP, the cell's energy currency, ATP synthase uses a mechanical rotation mechanism to utilize the energy generated by oxidation of foodstuffs. ATP synthase enzyme is critical to human health and is likely to contribute to new therapies for multiple diseases, such as cancer, bacterial infections, and obesity, that affect both people and animals [11–15].

2.1. General Features

Figure 1 shows the general structural and functional aspects of ATP synthase in its simplest form found in Escherichia coli with a total molecular size of ~530 kDa and contains eight different subunits, namely, α 3 β 3 γδεab2c10–15. F1 corresponds to α 3 β 3 γδε and F0 to ab2c10–15. In chloroplast and mitochondria the general structure is similar to E. coli except that there are two isoforms and 7–9 additional subunits, respectively. It is also known that as a complex they contribute only to a small fraction of additional mass and may have regulatory roles [16–18]. F1F0-ATP synthase is the smallest known biological nanomotor, found in almost all living organisms including plants, animals, and bacteria. This enzyme is responsible for ATP synthesis by oxidative or photophosphorylation in membranes of bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts. Thus, ATP synthase is the central means of cell energy production in animals, plants, and almost all microorganisms. A typical 70 kg human with a relatively sedentary lifestyle will generate around 2.0 million kg of ATP from ADP and Pi (inorganic phosphate) in a 75-year lifespan. Present understanding of the F1F0 structure and mechanism can be found in references [4, 11, 14, 19–41].

Figure 1.

Escherichia coli F1F0 ATP synthase structure: E. coli ATP synthase in the simplest form contains water soluble F1 and membrane bound F0 sectors. Catalytic activity ensues at the α/β interface of F1 sector. Many inhibitors also bind to the F1 sector which comprises five subunits (α 3 β 3 γδε). The proton pumping occurs at the F0 sector comprising three subunits (ab2c). This structure of E. coli F1F0 ATP synthase is reproduced from Weber [27] with permission; copyright Elsevier.

ATP hydrolysis and synthesis occur on three catalytic sites at the interface of α/β subunit in the F1 sector, whereas proton transport occurs through the membrane embedded F0 sector. Proton gradient-driven clockwise rotation of γ (as viewed from the membrane) leads to ATP synthesis and anticlockwise rotation of γ results in ATP hydrolysis [15]. The γεcn forms the part of rotor, while b2 δ is the part of stator in ATP synthase [38, 42–44].

The production of ATP reaction in the three catalytic sites ensues sequentially. In this reaction mechanism, the three catalytic sites have altered affinities for nucleotides at any moment, and each undergoes conformational transitions which results in the direction of substrate (ADP + Pi) binding→ATP synthesis→ATP release. In other words catalysis requires sequential involvement of three catalytic sites where each catalytic site changes its binding affinity for substrates and products as it proceeds through the cyclical mechanism known as “binding change mechanism” initially proposed by Boyer [45–51].

Proton motive force is converted in F0 to mechanical rotation of the rotor shaft, which drives conformational changes of the catalytic domains in F1 to synthesize ATP. Conversely, hydrolysis of ATP induces reverse conformational changes and consequently reverses rotation of the shaft. Rotation of γ subunit in isolated α 3 β 3 γ subcomplex has been observed directly by Yoshida, Kinosita, and colleagues in Japan and subsequently by several other labs [4, 25, 36, 52–58]. The reaction mechanism of ATP hydrolysis and synthesis in F1F0 and their relationship to the γ-subunit mechanical rotation is a fundamental question, has relevance to nanotechnology, and applies to many ATPases and GTPases [59, 60].

2.2. Nature and Modulation of the Catalytic Site Residues

Experimental data shows that modulations of catalytic sites can result in enhanced catalytic and motor functions of ATP synthase [61, 62]. For the purpose of catalytic site modifications of ATP synthase it is important to understand the terms associated with catalytic sites and the residues involved in it. According to X-ray crystallographers the three catalytic sites of ATP synthase are βTP for ATP, βDP for ADP, and βE the empty state to which Pi (inorganic phosphate) binds [63–65]. Also, in active cells, the cytoplasmic concentrations of ATP and Pi are approximately in the 2–5 mM range, whereas that of ADP is at least 10–50-fold lower. Equilibrium binding assays have established that both ADP and ATP bind to catalytic sites with relatively similar binding affinities [66–69]. During ATP synthesis, proton gradient-driven rotation of subunits drives βE the empty catalytic site to bind Pi tightly, thus stereochemically precluding ATP binding and therefore selectively favoring ADP binding [28].

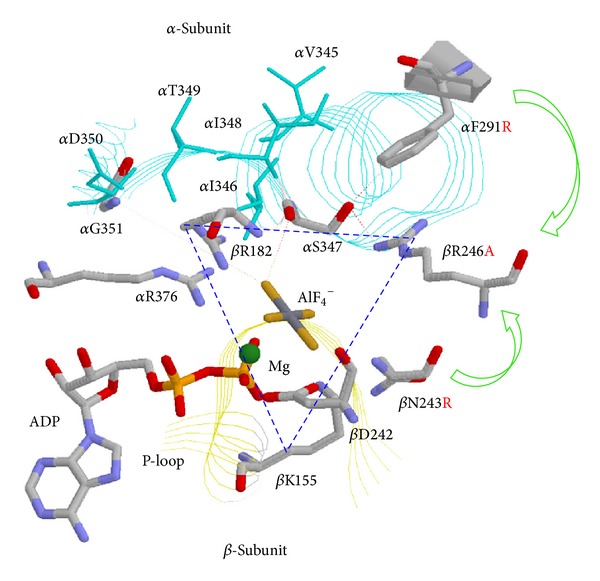

Physical and chemical properties of amino acids in general and positive charges in particular play critical role in the catalytic sites. Positively charged arginine residues are known to occur with high propensity in Pi binding sites of proteins generally and in the Pi binding site of βE catalytic site of ATP synthase specifically [70]. Earlier [22, 33, 61, 62, 71–75] it was found that removal of positive charge from the catalytic site Pi binding subdomain abrogates Pi binding and Pi binding was restored by replacing a nonpositive neighboring residue with positively charged arginine (see Figure 2). This study signifies the importance of modulation of charge in the phosphate binding site of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. It was found that by inserting positive charges in incremental order in specific positions in the catalytic site, it is possible not only to restore Pi binding but also to enhance the catalytic activity of the enzyme. This possibility of catalytic modification is of high value in the creation of a catalytically controllable, superior biological nanomotor.

Figure 2.

Catalytic sites X-ray structure of ATP synthase depicting spatial relationship between α and β-subunit residues. The βDP site in the AlF4 −-inhibited enzyme structure is taken from [63]. E. coli residue numbering is used. It can be seen that removal of arginine from βR246 can be compensated by introduction of arginine in the neighboring residues αF291 or βN243. Dotted triangle shows the residues βLys-155, βArg-182, βArg-246, αArg-376, and αSer-347, forming a triangular Pi binding site. Figure was modified from the originally published figure in [75]. RasMol molecular visualization software was used to generate the figure.

2.3. Role in Disease Conditions

Normal functioning of ATP synthase is indispensable to human health. Although failure of the ATP synthase complex is implicated in wide variety of diseases but simultaneously this enzyme may also be used as a therapeutic drug target in the treatment of many disease conditions such as cancer, tuberculosis, obesity, Alzheimer's, and microbial infections [14, 15, 21, 76, 77]. Subunit malfunctions in ATP synthase are the cause of many diseases; for example, the c-subunit of ATP synthase is involved in neuro degenerative Battens disease [78]. Buildup of α-subunit and reduction of β-subunit in the cytosol is seen in Alzheimer's disease patients [79, 80]. Subunit F6 has been associated with hypertension [81, 82]. Occurrence of ATP synthase on the multiple animal cell surfaces is linked with many cellular processes, for example, angiogenesis, intracellular pH regulation, and programmed cell death [83–91]. Moreover, the inhibition of nonmitochondrial ATP synthase was found to cause the inhibition of cytosolic lipid droplet buildup making ATP synthase an appropriate molecular target for antiobesity drugs [92].

2.4. Potential Molecular Drug Target

So far approximately twelve binding sites for a variety of natural and synthetic inhibitors have been identified on ATP synthase. Thus the use of ATP synthase as a potential molecular drug target seems straight forward. Recently the role of dietary polyphenols and peptides as antimicrobial and antitumor molecules targeting ATP synthase came to prominence [15, 21, 93–97]. Defense against dental cavities caused by the microbe Streptococcus mutans presents an amazing example for this potential. Inhibition of S. mutans ATP synthase provides a prophylactic effect against S. mutans metabolism by arresting biofilm formation and acid production [98, 99]. Another valuable example comes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis ATP synthase, where two mutations (D32V and A63P) in its c-subunit cause resistance to the tuberculosis drug diarylquinoline [100, 101]. The importance of ATP synthase as a promising target for drug development is also evident from the fact that many antibiotics such as efrapeptins, aurovertins, and oligomycins inhibit its function [21, 102–106].

2.5. ATP Synthase as a Nanomotor

It's noteworthy that ATP synthase has been widely studied by many laboratories using biochemical, biophysical, genetic, and molecular biology techniques. X-ray crystallographic studies have clarified the detailed subunit composition. The coupling between the mechanical force generated by rotation of subunits and chemical reactions of ATP synthase has also been elucidated [107–109]. The smallest known single molecule of F1-ATPase acting as a rotary motor by direct observation of its motion was observed first time in 1997 by Noji et al. [36]. They suggested that the γ-subunit of F1-sector rotates within the α/β interface. This speculation has been supported by structural, biochemical, and spectroscopic studies. They attached a fluorescent actin filament to the γ-subunit and detected the motion directly. In the presence of ATP, the F1 rotated for more than 100 revolutions. The single-molecule measurements of rotation catalyzed by the F1F0 ATP synthase from Frasch lab [4] have provided new insights into the molecular mechanisms of the F1F0 molecular nanomotors. Finally universal presence of ATP synthase makes it more fascinating than other known biological nanomotors which are restricted to certain species, cells, or tissues. This enzyme can also work both in forward and reverse directions.

3. Bacterial Flagella

3.1. General Features

Flagellum is an attachment that overhangs from the body of some eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. The established role of the flagellum is propulsion but it is also sensitive to chemicals and temperatures outside the cell, thus functioning as a sensory organelle. However, while both prokaryotic and eukaryotic flagella are used for swimming, they vary significantly in protein composition, structure, and mechanism of propulsion [110, 111]. The bacterial flagellum is made up of the protein flagellin and is driven by a protein rotary engine (the Mot complex), located at the flagellum's anchor point on the inner cell membrane. The flagellum is powered by a proton motive force. H+ ions move across the cell due to a concentration gradient. Some bacterial species flagella are driven by a sodium ion pump rather than a proton pump [112].

3.2. Rotatory Properties

The rotary action transports protons across the membrane. Although the rotor part itself can operate at ~6–15 K rpm, flagella filament typically attain a maximum speed of 200–1000 rpm. The tubular shape of flagella is suited to movement of microscopic organisms, where the viscosity of the surrounding water is much more important than its mass or inertia [113]. The intensity of proton motive force controls the rotational speed of flagella which in turn permits extraordinary speed in proportion to their size. Some bacteria can achieve up to 60 times to their cell length per second [114–116].

3.3. Structural and Functional Properties

Structurally bacterial flagellar nanomotors consist of a nonrotating stator part composed of MotA and MotB proteins and rotor made of FliG, FliM, and FliN proteins. The stator complex couples ion flow to rotation through cyclical conformational changes in MotB protein. The rotor complex is also referred to as “switch complex” because it can mediate counterclockwise to clockwise (CCW to CW) reversals. The switch complex forms a large cylindrical ring (C-ring) comprised of multimeric rings of FliG, FliM, and FliN proteins. Chemotactic protein phospho-CheY binds to FliM to signal a direction switch through FliG. A CCW to CW switch occurs with a conformational change in FliG subunit [117]. Interestingly, a three-amino acid deletion mutant of FliG has been studied which is locked in the CW direction [118].

3.4. The Base Model Question

The question of paramount importance is whether or not bacterial flagella can be used as a base model in the development of nanomotors in nanomedicine usage. Since it would be difficult to reconstitute flagellar motors from isolated motor proteins, most work in this area employs intact cells with preassembled motors. The attendant problem of limited cell lifetime could be best overcome if “old” cells could be swapped out with new cells. One application for nanotechnology of the flagellar nanomotor is as a living fluid mixer [119]. A tethered flagellum allows rotation of E. coli cells at about 240 rpm to drive local solution mixing. Construction of a hybrid microrotary motor driven by Mycoplasma mobile cells was achieved by Hiratsuka et al. [120]. Although gliding bacteria differ in mechanism from bacteria flagellar motors, mechanical walking of rod-like structures driven by motors is believed to be involved. In these studies continuous rotation of 20 μm SiO2 fabricated rotors at about 2 rpm was observed. This was the first example of “flagellar motors” driving microfabricated structures. Microdevices which employ bacterial flagellar motors for fluid transport or mixing have been fabricated [121]. Patterning of attached bacteria in these microdevices showed linear velocities of microspheres up to 150 μms−1. Motile bacteria which exhibit magnetotaxis, such as strain MC-1, a marine coccus, are being developed as drug targeting vehicles [122]. Advantages for these motile organisms are in vivo steerability and external control by MRI systems favors this type of “nanorobot”. Technical hurdles, such as bacterial navigation in large blood vessels, still need to be overcome. MRI imaging of these motile bacteria truly sets this system apart and bodes well for near future applications in medicine.

4. Kinesins

4.1. General Features

A kinesin is another motor protein found in eukaryotic cells. Kinesins are ATPases which require ATP hydrolysis for their movement along the microtubule filaments. Several cellular tasks such as mitosis, meiosis, and transport of cellular cargo, for example, axonal transport are achieved by active movement of kinesins. The kinesins are responsible for anterograde or outward transport of cargo from the cell center. Primarily, kinesins were discovered as microtubule based anterograde intracellular transport nanomotors [123]. In recent years as the kinesin superfamily became very large a variety of naming patterns started floating around, leading to duplication and confusions. To address this and other issues that were in the classification, American Society for Cell Biology meeting in 2003 formulated a standardized kinesin nomenclature based on 14-family designations [124–126].

4.2. Overall Structure

The overall structure of kinesin superfamily members differs but the exemplary kinesin-1 consists of heavy (KHCs) and light chains (KLCs), thus forming a heterotetramer. The motor domain or the globular head of the KHC at the amino terminal end is connected to the stalk, a long alpha-helical coiled-coil domain, which ends in a carboxy terminal tail domain and in turn is associated with the light-chains. The stalks of two KHCs intertwine to form a coiled-coil that directs dimerization of the two KHCs. Mostly transported cargo binds to the KLC but in some cases cargo can also bind to the KHC c-terminal domains [127].

4.3. Motor Domain

Amino acid sequence of the globular head domain is highly conserved among various kinesins. The globular head has two discrete binding sites for the microtubule and for ATP. ATP binding → ATP hydrolysis → ADP release causes the conformational changes in the microtubule-binding domains that result in the movement of the kinesin. Kinesins are structurally related to G proteins, which hydrolyze GTP instead of ATP. Nanomotor proteins such as kinesins transport large cargo by unidirectional walking along the microtubule tracks by hydrolyzing one ATP molecule at each step [128]. Multiple kinesin nanomotors are also known to cooperatively transport the cargoes in-vivo [129–132]. The detailed discussion on ATP powered step-wise movement of kinesin head along with microtubules can be found in the references [133, 134].

4.4. Applicability in Nanomedicine

Applications of kinesin nanomotors to nanotechnology continue to evolve. Two basic configurations for kinesin motors are fixing of kinesins to fluidic channels to propel microtubules or microtubule immobilization for kinesin tracking. Steering of microtubules has been achieved by application of an electric field perpendicular to kinesin coated microfluidic channels [135]. By reversing the electric field, sorting of red or green labeled microtubules to left and right collecting reservoirs was achieved. One goal for kinesin nanomotors is the development of microfluidic devices which can deliver specific analytes from cargo loading chambers to detector ports, thus achieving sorting and concentration functions. A major drawback for the use of kinesins for nanotechnology is a deficiency of specific docking systems of the cargo.

5. Dyneins

Like kinesins dyneins are also cytoskeletal type of molecular motor proteins, which require the energy from ATP to perform mechanical work. In contrast to the kinesins, which transport the cellular cargo from the center of the cell towards the periphery, the plus-end dyneins transport cellular cargo towards the cell center, the minus-end of the microtubule. Thus dyneins and kinesins are named minus-end and plus-end directed nanomotors, respectively.

Dynein walks in such a way that at any given time one of its stalks is continuously attached to the microtubule. This allows the dynein to move a substantial distance along the microtubule without detaching. Cytoplasmic dynein helps transport cargo needed for cell functions and is also involved in the movement of chromosomes and positioning the mitotic spindles for cell divisions [136]. Dynein as a motor is a complex protein assembly composed of many smaller polypeptide subunits.

Dynein has a molecular mass of about 1.5 MDa and comprises nearly twelve polypeptide subunits. Two of them are identical heavy chains of ~520 kDa containing the ATPase activity and are thus responsible for generating movement along the microtubule. Two are 74 kDa intermediate chains which are thought to attach the dynein to its cargo; four are ~56 kDa intermediate chains; and the rest are less known light chains. Also, another multisubunit protein dynactin (dynein activator complex), essential for mitosis, regulates the activity of dynein. Dynein gets activated by binding to dynactin which in turn facilitates cargo attachment to dynein [137]. Due to the more complex structure of dyneins compared to the kinesins, applications to nanotechnology have yet to be developed.

6. Myosin

Myosin is a family of ATP-dependent motor proteins and is mainly involved in muscle contraction. Structurally myosin molecule is composed of two large polypeptide heavy chains and four smaller light chains. Both heavy and light chain polypeptides combine to form two globular heads, while only heavy chains intertwine to form the tail part. The myosin molecules makeup the core of thick filament and remain oriented in opposite directions. Each globular head contains two binding sites one for actin and other for ATP. Overall muscle contraction requires involvement of another thin filament protein actin. In essence myosin provides actin-based motility [138–140].

As far as myosin's role in nanomedicine is concerned investigations into use of contractile cell grafts for myocardial regeneration have begun [141]. Also, the transport of liposome tethered to bundled actin over myosin coated surfaces has also been examined [142]. The applications of myosin-actin in nanomedicine are still in infancy stages and are just emerging.

While detailed structural and functional aspects of F1F0 ATP synthase are available to use for its role in nanomedicine for other nanomotors it still seems a long way to go. Analysis of all biological nanomotors shows that many nanomotor proteins link catalytic ATP utilization to linear, unidirectional force generation. More is known of the kinesins and myosins than dyneins, primarily due to the greater molecular complexity of the latter type. Kinesins are microtubule motors which consist of 45 members in the mammalian kinesin superfamily. Kinesins are involved in cargo transport in cells by tethering different cargo vesicles to divergent tail domains. Most kinesins track processively along microtubules towards the plus end with a few members of the family tracking to the minus end [143]. Force production of kinesins, and structurally related myosins, involves conformational changes in motor proteins converting strain relieving recoil into force generation [144]. A kinesin force-producing conformational change within the motor protein, upon ATP binding, results in altered motor to filament interaction. Processive movement of the kinesin is believed to be due to chemical gating which requires communication between the two motor headpieces. Conserved motifs within the kinesins are the nucleotide binding P-loop and switch I and II loops [145]. During the nucleotide catalytic cycle small movements of the loop regions are transmitted to movement of the neck linker segment.

In this review we have focused on nanomotors that have shown some promise of being applicable in nanomedicine. Many biological nanomotors such as myosin, actin, microtubule, dynamin, RNA polymerase, DNA polymerase, helicases, topoisomerases, and viral DNA packaging motors currently have few nanomedicine applications; therefore they are subject of a separate future review article.

7. Conclusions

Being relatively new nanobiology or nanobiotechnology covers a variety of related technologies. This is basically a merger of molecular biology with technology that covers nanodevices, nanoparticles, protein motors, and other nanoscale phenomenon in the living cells. One of the objectives behind nanobiology is to apply nanotools to solve relevant medical/biological problems. Developing new tools and refining them for delivering better health care is another principal objective of nanotechnology [146].

Overall rotatory motor functions and universal presence makes F1F0 ATP synthase a front runner base model in the development of nanomotors for nanomedicine usage. Moreover, the first tentative steps in nanotechnology with biological nanomotors have begun. It will be of great interest to see the development of hybrid technologies which link microfabrication to various biological nanomotors. The realization of the full potential in this exciting area will begin to occur when useful devices driven by nanomotors appear.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant no. GM085771 to ZA.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Bustamante C, Chemla YR, Forde NR, Izhaky D. Mechanical processes in biochemistry. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2004;73:705–748. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J. Cargo-towing synthetic nanomachines: towards active transport in microchip devices. Lab on a Chip. 2012;12:1944–1950. doi: 10.1039/c2lc00003b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennadam SS, Firman K, Alexander C, Górecki DC. Protein-polymer nano-machines. Toward synthetic control of biological processes. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2004;2, article 8 doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hornung T, Martin J, Spetzler D, Ishmukhametov R, Frasch WD. Microsecond resolution of single-molecule rotation catalyzed by molecular motors. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2011;778:273–289. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-261-8_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreyfus R, Baudry J, Roper ML, Fermigier M, Stone HA, Bibette J. Microscopic artificial swimmers. Nature. 2005;437(7060):862–865. doi: 10.1038/nature04090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallouk TE, Sen A. Powering nanorobots: catalytic engines enable tiny swimmers to harness fuel from their environment and overcome the weird physics of the microscopic world. Scientific American. 2009;300(5):72–77. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0509-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paxton WF, Kistler KC, Olmeda CC, et al. Catalytic nanomotors: autonomous movement of striped nanorods. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126(41):13424–13431. doi: 10.1021/ja047697z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier-Bidoz S, Arsenault AC, Manners I, Ozin GA. Synthetic self-propelled nanorotors. Chemical Communications. 2005;(4):441–443. doi: 10.1039/b414896g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mei Y, Solovev AA, Sanchez S, Schmidt OG. Rolled-up nanotech on polymers: from basic perception to self-propelled catalytic microengines. Chemical Society Reviews. 2011;40(5):2109–2119. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00078g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibele M, Mallouk TE, Sen A. Schooling behavior of light-powered autonomous micromotors in water. Angewandte Chemie. 2009;48(18):3308–3312. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen PL. Transport ATPases into the year 2008: a brief overview related to types, structures, functions and roles in health and disease. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2007;39:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedersen PL. The cancer cell’s “power plants” as promising therapeutic targets: an overview. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2007;39:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen PL. Transport ATPases: structure, motors, mechanism and medicine: a brief overview. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2005;37:349–357. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong S, Pedersen PL. ATP synthase and the actions of inhibitors utilized to study its roles in human health, disease, and other scientific areas. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2008;72:590–641. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad Z, Laughlin TF. Medicinal chemistry of ATP synthase: a potential drug target of dietary polyphenols and amphibian antimicrobial peptides. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;17(25):2822–2836. doi: 10.2174/092986710791859270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senior AE. ATP synthesis by oxidative phosphorylation. Physiological Reviews. 1988;68(1):177–231. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karrasch S, Walker JE. Novel features in the structure of bovine ATP synthase. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;290(2):379–384. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devenish RJ, Prescott M, Roucou X, Nagley P. Insights into ATP synthase assembly and function through the molecular genetic manipulation of subunits of the yeast mitochondrial enzyme complex. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1458(2-3):428–442. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senior AE. Two ATPases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:30049–30062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.X112.402313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senior AE. ATP Synthase: motoring to the Finish Line. Cell. 2007;130(2):220–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad Z, Okafor F, Azim S, Laughlin TF. ATP synthase: a molecular therapeutic drug target for antimicrobial and antitumor peptides. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;20:1956–1973. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320150003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad Z, Okafor F, Laughlin TF. Role of charged residues in the catalytic sites of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. Journal of Amino Acids. 2011;2011:12 pages. doi: 10.4061/2011/785741.785741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker JE. The ATP synthase: the understood, the uncertain and the unknown. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2013;41:1–16. doi: 10.1042/BST20110773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamoto RK, Baylis Scanlon JA, Al-Shawi MK. The rotary mechanism of the ATP synthase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2008;476(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishmukhametov R, Hornung T, Spetzler D, Frasch WD. Direct observation of stepped proteolipid ring rotation in E. coli F1F0-ATP synthase. EMBO Journal. 2010;29(23):3911–3923. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blum DJ, Ko YH, Pedersen PL. Mitochondrial ATP synthase catalytic mechanism: a novel visual comparative structural approach emphasizes pivotal roles for Mg2+ and P-loop residues in making ATP. Biochemistry. 2012;51(7):1532–1546. doi: 10.1021/bi201595v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber J. ATP synthase: subunit-subunit interactions in the stator stalk. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1757:1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber J, Senior AE. ATP synthase: what we know about ATP hydrolysis and what we do not know about ATP synthesis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1458:300–309. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Senior AE, Nadanaciva S, Weber J. The molecular mechanism of ATP synthesis by F1F0-ATP synthase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2002;1553(3):188–211. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Senior AE, Nadanaciva S, Weber J. Rate acceleration of ATP hydrolysis by F1F0-ATP synthase. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2000;203(1):35–40. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frasch WD. The participation of metals in the mechanism of the F1-ATPase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1458(2-3):310–325. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamoto RK, Ketchum CJ, al-Shawi MK. Rotational coupling in the F0F1 ATP synthase. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 1999;28:205–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. Identification of phosphate binding residues of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2005;37:437–440. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noji H, Yoshida M. The rotary machine in the cell, ATP synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(3):1665–1668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan S. Rotary chemiosmotic machines. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1997;1322:86–105. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(97)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noji H, Yasuda R, Yoshida M, Kinosita K., Jr. Direct observation of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Nature. 1997;386(6622):299–302. doi: 10.1038/386299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinosita K, Jr., Yasuda R, Noji H, Adachi K. A rotary molecular motor that can work at near 100% efficiency. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2000;355:473–489. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Itoh H, Takahashi A, Adachi K, et al. Mechanically driven ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase. Nature. 2004;427(6973):465–468. doi: 10.1038/nature02212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinosita K., Jr. F1-ATPase: a prototypical rotary molecular motor. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2012;726:5–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0980-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capaldi RA, Aggeler R. Mechanism of the F1F0-type ATP synthase, a biological rotary motor. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2002;27(3):154–160. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)02051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandt K, Muller DB, Hoffmann J. Functional production of the Na+F1F0 ATP synthase from Acetobacterium woodii in Escherichia coli requires the native AtpI. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2013;45:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9474-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diez M, Zimmermann B, Börsch M, et al. Proton-powered subunit rotation in single membrane-bound F0F1-ATP synthase. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2004;11(2):135–141. doi: 10.1038/nsmb718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkens S, Borchardt D, Weber J, Senior AE. Structural characterization of the interaction of the δ and α subunits of the Escherichia coliF1F0-ATP synthase by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2005;44(35):11786–11794. doi: 10.1021/bi0510678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senior AE, Muharemagić A, Wilke-Mounts S. Assembly of the stator in Escherichia coli ATP synthase. Complexation of α subunit with other F1 subunits is prerequisite for δ subunit binding to the N-terminal region of α . Biochemistry. 2006;45(51):15893–15902. doi: 10.1021/bi0619730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyer PD. A perspective of the binding change mechanism for ATP synthesis. FASEB Journal. 1989;3(10):2164–2178. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.10.2526771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boyer PD. A research journey with ATP synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(42):39045–39061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.X200001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyer PD. Catalytic site occupancy during ATP synthase catalysis. FEBS Letters. 2002;512(1–3):29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boyer PD. New insights into one of nature’s remarkable catalysts, the ATP synthase. Molecular Cell. 2001;8(2):246–247. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyer PD. Catalytic site forms and controls in ATP synthase catalysis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1458:252–262. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boyer PD. What makes ATP synthase spin? Nature. 1999;402(6759):247–249. doi: 10.1038/46193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyer PD. ATP synthase—past and future. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1998;(1365):3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yasuda R, Noji H, Kinosita K, Jr., Yoshida M. F1-ATPase is a highly efficient molecular motor that rotates with discrete 120° steps. Cell. 1998;93(7):1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kinosita K, Jr., Yasuda R, Noji H, Ishiwata S, Yoshida M. F1-ATPase: a rotary motor made of a single molecule. Cell. 1998;93(1):21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishizaka T, Oiwa K, Noji H, et al. Chemomechanical coupling in F1-ATPase revealed by simultaneous observation of nucleotide kinetics and rotation. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2004;11(2):142–148. doi: 10.1038/nsmb721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshida M, Muneyuki E, Hisabori T. ATP synthase—a marvellous rotary engine of the cell. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2001;2(9):669–677. doi: 10.1038/35089509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Senior AE, Weber J. Happy motoring with ATP synthase. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology . 2004;11:110–112. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0204-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bilyard T, Nakanishi-Matsui M, Steel BC, et al. High-resolution single-molecule characterization of the enzymatic states in Escherichia coli F1-ATPase. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2013;368 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0023.20120023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Düser MG, Zarrabi N, Cipriano DJ, et al. 36° step size of proton-driven c-ring rotation in F0F1-ATP synthase. EMBO Journal. 2009;28(18):2689–2696. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitesides GM. The “right” size in nanobiotechnology. Nature Biotechnology. 2003;21(10):1161–1165. doi: 10.1038/nbt872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Firoz A, Malik A, Joplin KH, Ahmad Z, Jha V, Ahmad S. Residue propensities, discrimination and binding site prediction of adenine and guanine phosphates. BMC Biochemistry. 2011;12(1, article 20) doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. Modulation of charge in the phosphate binding site of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(30):27981–27989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brudecki LE, Grindstaff JJ, Ahmad Z. Role of αPhe-291 residue in the phosphate-binding subdomain of catalytic sites of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2008;471(2):168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Menz RI, Walker JE, Leslie AGW. Structure of bovine mitochondrial F1-ATPase with nucleotide bound to all three catalytic sites: implications for the mechanism of rotary catalysis. Cell. 2001;106(3):331–341. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Braig K, Menz RI, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. Structure of bovine mitochondrial F1-ATPase inhibited by Mg2+ADP and aluminium fluoride. Structure. 2000;8(6):567–573. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Orriss GL, Leslie AGW, Braig K, Walker JE. Bovine F1-ATPase covalently inhibited with 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan: the structure provides further support for a rotary catalytic mechanism. Structure. 1998;6(7):831–837. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weber J, Wilke-Mounts S, Lee RS-F, Grell E, Senior AE. Specific placement of tryptophan in the catalytic sites of Escherichia coli F1-ATPase provides a direct probe of nucleotide binding: maximal ATP hydrolysis occurs with three sites occupied. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(27):20126–20133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Löbau S, Weber J, Senior AE. Catalytic site nucleotide binding and hydrolysis in F1F0-ATP synthase. Biochemistry. 1998;37(30):10846–10853. doi: 10.1021/bi9807153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weber J, Hammond ST, Wilke-Mounts S, Senior AE. Mg2+ coordination in catalytic sites of F1-ATPase. Biochemistry. 1998;37(2):608–614. doi: 10.1021/bi972370e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dou C, Fortes PAG, Allison WS. The α3(βY341W)3γ subcomplex of the F1-ATpase from the thermophilic Bacillus PS3 fails to dissociate ADP when MgATP is hydrolyzed at a single catalytic site and attains maximal velocity when three catalytic sites are saturated with MgATP. Biochemistry. 1998;37(47):16757–16764. doi: 10.1021/bi981717q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Copley RR, Barton GJ. A structural analysis of phosphate and sulphate binding sites in proteins estimation of propensities for binding and conservation of phosphate binding sites. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1994;242(4):321–329. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. Mutagenesis of residue β-Arg-246 in the phosphate-binding subdomain of catalytic sites of Escherichia coli F1-ATPaSe. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:31505–31513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. Role of βAsn-243 in the phosphate-binding subdomain of catalytic sites of Escherichia coli F1-ATPase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(44):46057–46064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. Involvement of ATP synthase residues αArg-376, βArg-182, and βLys-155 in Pi binding. FEBS Letters. 2005;579(2):523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. Inhibition of the ATPase activity of Escherichia coli ATP synthase by magnesium fluoride. FEBS Letters. 2006;580(2):517–520. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li W, Brudecki LE, Senior AE, Ahmad Z. Role of α-subunit VISIT-DG sequence residues Ser-347 and Gly-351 in the catalytic sites of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(16):10747–10754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809209200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. How the regulatory protein, IF1, inhibits F1-ATPase from bovine mitochondria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(40):15671–15676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Mechanism of inhibition of bovine F1-ATPase by resveratrol and related polyphenols. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(34):13632–13637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706290104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Palmer DN, Fearnley IM, Walker JE, et al. Mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit c storage in the ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease) American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1992;42(4):561–567. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schagger H, Ohm TG. Human diseases with defects in oxidative phosphorylation—2. F1F0 ATP-synthase defects in Alzheimer disease revealed by blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1995;227(3):916–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sergeant N, Wattez A, Galván-Valencia M, et al. Association of ATP synthase α-chain with neurofibrillary degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2003;117(2):293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00747-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Osanai T, Magota K, Tanaka M, et al. Intracellular signaling for vasoconstrictor coupling factor 6: novel function of β-subunit of ATP synthase as receptor. Hypertension. 2005;46(5):1140–1146. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000186483.86750.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Osanai T, Okada S, Sirato K, et al. Mitochondrial coupling factor 6 is present on the surface of human vascular endothelial cells and is released by shear stress. Circulation. 2001;104(25):3132–3136. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.100832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arakaki N, Nagao T, Niki R, et al. Possible role of cell surface H+-ATP synthase in the extracellular ATP synthesis and proliferation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Molecular Cancer Research. 2003;1(13):931–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Berger K, Winzell MS, Mei J, Erlanson-Albertsson C. Enterostatin and its target mechanisms during regulation of fat intake. Physiology and Behavior. 2004;83(4):623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Champagne E, Martinez LO, Collet X, Barbaras R. Ecto-F1F0 ATP synthase/F1 ATPase: metabolic and immunological functions. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2006;17:279–284. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000226120.27931.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kenan DJ, Wahl ML. Ectopic localization of mitochondrial ATP synthase: a target for anti-angiogenesis intervention? Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2005;37:461–465. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moser TL, Kenan DJ, Ashley TA, et al. Endothelial cell surface F1F0 ATP synthase is active in ATP synthesis and is inhibited by angiostatin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(12):6656–6661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131067798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang WJ, Ma Z, Liu YW, et al. A monoclonal antibody (Mc178-Ab) targeted to the ecto-ATP synthase β-subunit-induced cell apoptosis via a mechanism involving the MAKase and Akt pathways. Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 2012;12:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s10238-011-0133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moser TL, Stack MS, Asplin I, et al. Angiostatin binds ATP synthase on the surface of human endothelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(6):2811–2816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burwick NR, Wahl ML, Fang J, et al. An inhibitor of the F1 subunit of ATP synthase (IF1) modulates the activity of angiostatin on the endothelial cell surface. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(3):1740–1745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405947200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chi SL, Wahl ML, Mowery YM, et al. Angiostatin-like activity of a monoclonal antibody to the catalytic subunit of F1F0 ATP synthase. Cancer Research. 2007;67(10):4716–4724. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Arakaki N, Kita T, Shibata H, Higuti T. Cell-surface H+-ATP synthase as a potential molecular target for anti-obesity drugs. FEBS Letters. 2007;581(18):3405–3409. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dadi PK, Ahmad M, Ahmad Z. Inhibition of ATPase activity of Escherichia coli ATP synthase by polyphenols. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2009;45(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chinnam N, Dadi PK, Sabri SA, Ahmad M, Kabir MA, Ahmad Z. Dietary bioflavonoids inhibit Escherichia coli ATP synthase in a differential manner. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2010;46(5):478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Laughlin TF, Ahmad Z. Inhibition of Escherichia coli ATP synthase by amphibian antimicrobial peptides. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2010;46:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ahmad Z, Ahmad M, Okafor F, et al. Effect of structural modulation of polyphenolic compounds on the inhibition of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2012;50(3):476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zheng J, Ramirez VD. Inhibition of mitochondrial proton F1F0-ATPase/ATP synthase by polyphenolic phytochemicals. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;130(5):1115–1123. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Percival RS, Devine DA, Duggal MS, Chartron S, Marsh PD. The effect of cocoa polyphenols on the growth, metabolism, and biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis . European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2006;114(4):343–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Duarte S, Gregoire S, Singh AP, et al. Inhibitory effects of cranberry polyphenols on formation and acidogenicity of Streptococcus mutans biofilms. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2006;257(1):50–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Andries K, Verhasselt P, Guillemont J, et al. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Science. 2005;307(5707):223–227. doi: 10.1126/science.1106753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cole ST, Alzari PM. TB—a new target, a new drug. Science. 2005;307(5707):214–215. doi: 10.1126/science.1108379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Abrahams JP, Buchanan SK, Van Raaij MJ, Fearnley IM, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. The structure of bovine F1-ATPase complexed with the peptide antibiotic efrapeptin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(18):9420–9424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Van Raaij MJ, Abrahams JP, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. The structure of bovine F1-ATPase complexed with the antibiotic inhibitor aurovertin B. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(14):6913–6917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wolvetang EJ, Johnson KL, Krauer K, Ralph SJ, Linnane AW. Mitochondrial respiratory chain inhibitors induce apoptosis. FEBS Letters. 1994;339:40–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mills KI, Woodgate LJ, Gilkes AF, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial function in HL60 cells is associated with an increased apoptosis and expression of CD14. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1999;263(2):294–300. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Symersky J, Osowski D, Walters DE, Mueller DM. Oligomycin frames a common drug-binding site in the ATP synthase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:13961–13965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207912109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wada Y, Sambongi Y, Futai M. Biological nano motor, ATP synthase F1F0: from catalysis to γε c 10-12 subunit assembly rotation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1459(2-3):499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bronzino JD. The Biomedical Engineering Handbook. 3rd edition. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC/Taylor & Francis; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Adachi K, Oiwa K, Nishizaka T, et al. Coupling of rotation and catalysis in F1-ATPase revealed by single-molecule imaging and manipulation. Cell. 2007;130(2):309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang Q, Suzuki A, Mariconda S, Porwollik S, Harshey RM. Sensing wetness: a new role for the bacterial flagellum. EMBO Journal. 2005;24(11):2034–2042. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Silflow CD, Lefebvre PA. Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii . Plant Physiology. 2001;127(4):1500–1507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Atsumi T, McCarter L, Imae Y. Polar and lateral flagellar motors of marine Vibrio are driven by different ion-motive forces. Nature. 1992;355(6356):182–184. doi: 10.1038/355182a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dusenbery DB. Living at Micro Scale: The Unexpected Physics of Being Small. Cambridge, Mass, USA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lele PP, Hosu BG, Berg HC. Dynamics of mechanosensing in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:11839–11844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305885110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu B, Powers TR, Breuer KS. Force-free swimming of a model helical flagellum in viscoelastic fluids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(49):19516–19520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113082108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Magariyama Y, Ichiba M, Nakata K, et al. Difference in bacterial motion between forward and backward swimming caused by the wall effect. Biophysical Journal. 2005;88(5):3648–3658. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sarkar MK, Paul K, Blair D. Chemotaxis signaling protein CheY binds to the rotor protein FliN to control the direction of flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(20):9370–9375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000935107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Togashi F, Yamaguchi S, Kihara M, Aizawa S-I, Macnab RM. An extreme clockwise switch bias mutation in fliG of Salmonella typhimurium and its suppression by slow-motile mutations in motA and motB. Journal of Bacteriology. 1997;179(9):2994–3003. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2994-3003.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Al-Fandi M, Jaradat MAK, Fandi K, Beech JP, Tegenfeldt JO, Yih TC. Nano-engineered living bacterial motors for active microfluidic mixing. IET Nanobiotechnology. 2010;4(3):61–71. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2010.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hiratsuka Y, Miyata M, Tada T, Uyeda TQP. A microrotary motor powered by bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(37):13618–13623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604122103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kaehr B, Shear JB. High-throughput design of microfluidics based on directed bacterial motilityY. Lab on a Chip. 2009;9(18):2632–2637. doi: 10.1039/b908119d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Martel S, Felfoul O, Mohammadi M, Mathieu JB. Interventional procedure based on nanorobots propelled and steered by flagellated magnetotactic bacteria for direct targeting of tumors in the human body. Proceedings of the Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2008; pp. 2497–2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vale RD. The molecular motor toolbox for intracellular transport. Cell. 2003;112(4):467–480. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lawrence CJ, Dawe RK, Christie KR, et al. A standardized kinesin nomenclature. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;167(1):19–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hirokawa N. Kinesin and dynein superfamily proteins and the mechanism of organelle transport. Science. 1998;279(5350):519–526. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.McDonald HB, Stewart RJ, Goldstein LSB. The kinesin-like ncd protein of Drosophila is a minus end-directed microtubule motor. Cell. 1990;63(6):1159–1165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hirokawa N, Pfister KK, Yorifuji H, Wagner MC, Brady ST, Bloom GS. Submolecular domains of bovine brain kinesin identified by electron microscopy and monoclonal antibody decoration. Cell. 1989;56(5):867–878. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90691-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schnitzer MJ, Block SM. Kinesin hydrolyses one ATP per 8-nm step. Nature. 1997;388(6640):386–390. doi: 10.1038/41111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gross SP, Vershinin M, Shubeita G. Cargo transport: two motors are sometimes better than one. Current Biology. 2007;17(12):R478–R486. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kunwar A, Vershinin M, Xu J, Gross SP. Stepping, strain gating, and an unexpected force-velocity curve for multiple-motor-based transport. Current Biology. 2008;18(16):1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Klumpp S, Lipowsky R. Cooperative cargo transport by several molecular motors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(48):17284–17289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507363102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hancock WO. Intracellular transport: kinesins working together. Current Biology. 2008;18(16):R715–R717. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Vale RD, Milligan RA. The way things move: looking under the hood of molecular motor proteins. Science. 2000;288(5463):p. 88. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mather WH, Fox RF. Kinesin’s biased stepping mechanism: amplification of neck linker zippering. Biophysical Journal. 2006;91(7):2416–2426. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.van den Heuvel MGL, de Graaff MP, Dekker C. Molecular sorting by electrical steering of microtubules in kinesin-coated channels. Science. 2006;312(5775):910–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1124258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kiyomitsu T, Cheeseman IM. Chromosome-and spindle-pole-derived signals generate an intrinsic code for spindle position and orientation. Nature Cell Biology. 2012;14(3):311–317. doi: 10.1038/ncb2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Karp G. Cell and Molecular Biology: Concepts and Experiments. 2nd edition. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley and Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Spudich JA, Huxley HE, Finch JT. Regulation of skeletal muscle contraction—II. Structural studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1972;72:619–632. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sellers JR, Goodson HV. Motor proteins 2: myosin. Protein Profile. 1995;2(12):1323–1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Swank DM, Knowles AF, Suggs JA, et al. The myosin converter domain modulates muscle performance. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4(4):312–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Wang H, Zhou J, Liu Z, Wang C. Injectable cardiac tissue engineering for the treatment of myocardial infarction. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2010;14(5):1044–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Takatsuki H, Tanaka H, Rice KM, et al. Transport of single cells using an actin bundle-myosin bionanomotor transport system. Nanotechnology. 2011;22(24) doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/24/245101.245101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Bananis E, Murray JW, Stockert RJ, Satir P, Wolkoff AW. Microtubule and motor-dependent endocytic vesicle sorting in vitro. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;151(1):179–186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Heuston E, Bronner CE, Kull FJ, Endow SA. A kinesin motor in a force-producing conformation. BMC Structural Biology. 2010;10, article 19 doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kull FJ, Endow SA. Force generation by kinesin and myosin cytoskeletal motor proteins. Journal of Cell Science. 2013;126:9–19. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Mashaghi S, Jadidi T, Koenderink G, Mashaghi A. Lipid nanotechnology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14:4242–4282. doi: 10.3390/ijms14024242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]