Abstract

We have developed a simple and accurate HPLC method for measurement of fecal bile acids using phenacyl derivatives of unconjugated bile acids, and applied it to the measurement of fecal bile acids in cirrhotic patients. The HPLC method has the following steps: 1) lyophilization of the stool sample; 2) reconstitution in buffer and enzymatic deconjugation using cholylglycine hydrolase/sulfatase; 3) incubation with 0.1 N NaOH in 50% isopropanol at 60°C to hydrolyze esterified bile acids; 4) extraction of bile acids from particulate material using 0.1 N NaOH; 5) isolation of deconjugated bile acids by solid phase extraction; 6) formation of phenacyl esters by derivatization using phenacyl bromide; and 7) HPLC separation measuring eluted peaks at 254 nm. The method was validated by showing that results obtained by HPLC agreed with those obtained by LC-MS/MS and GC-MS. We then applied the method to measuring total fecal bile acid (concentration) and bile acid profile in samples from 38 patients with cirrhosis (17 early, 21 advanced) and 10 healthy subjects. Bile acid concentrations were significantly lower in patients with advanced cirrhosis, suggesting impaired bile acid synthesis.

Keywords: extraction, esterified bile acids, bile acid 24-phenacyl ester, derivatization, liver cirrhosis, high-performance liquid chromatography, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, routine analysis

The composition of circulating bile acids in humans is a complex mixture of primary and secondary bile acids. In humans, primary bile acids are chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) and cholic acid (CA), each secreted into bile in mostly N-acyl amidated form, i.e., conjugated with glycine or taurine in an amide linkage (1–3). In the distal intestine, bile acids are modified by bacterial enzymes. Major modifications include deconjugation followed by dehydroxylation at C-7, by which CA is converted to deoxycholic acid (DCA) and CDCA is converted to lithocholic acid (LCA). Other bacterial modifications include epimerization at C-3 to form iso bile acids, oxidation of any of the hydroxyl groups, and desaturation of the side chain. The epimerization of the C-7 hydroxyl group of CDCA results in the formation of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). Secondary bile acids are absorbed from the intestine to a varying degree, and are extracted by the hepatocyte where they may undergo additional modifications such as epimerization of iso bile acids to 3α-hydroxy bile acids, as well as reconjugation. LCA is also sulfated in part in addition to being N-acylamidated so that about half of the lithocholyl amidates are sulfated at C-3 (4). In humans, UDCA is not epimerized during hepatocyte transport, and most people have a few percent of UDCA in their biliary bile acids that has been formed in the intestine (1). Daily bile acid excretion to the feces is 300–600 mg/day in health (3), and under steady state conditions is equal to bile acid synthesis from cholesterol.

Bile acids play important roles in digestion, modulation of gut microbiota, and regulation of pathways necessary for cholesterol, lipid, and glucose homeostasis (3, 5). Therefore, evaluation of bile acid levels in healthy as well as diseased individuals is essential. Cirrhosis represents a particularly important clinical condition, in which the synthetic organ for bile acids, the liver, is damaged, and progression of disease is modulated by altered gut microbiota that can also impact bile acid metabolism (6, 7).

A variety of methods have been reported for bile acid analysis in biological fluids, such as bile, plasma, urine, and stool (1, 8). Analysis of fecal bile acids is by far the most difficult because of the multiplicity of fecal bile acids as well as the great range of polarity of fecal bile acids. For the quantification of individual bile acids, GC, HPLC, and their combination with MS are commonly utilized. Of these analytical methods, HPLC-MS is currently the most technically advanced. It allows screening of bile acid profiles without tedious prior sample purification. A number of reports based on this method have been published (1, 8). However, despite these advantages, the extraction of bile acids from feces has not been clearly described in prior studies. In addition, such methods have high overhead costs, limiting their routine use. Therefore, development of a simple and accurate HPLC method for fecal bile acids would be a useful advancement.

In the present paper, we report the development of a simple and accurate HPLC method for measurement of fecal bile acids using phenacyl derivatives, and its application to samples from healthy controls and patients with cirrhosis. Unconjugated bile acids, in contrast to conjugated bile acids, do not have appreciable absorbance at 205 nm (2, 8, 9), explaining our use of phenacyl derivatives that have a strong absorbance at 254 nm. Our method provides nearly identical results to those obtained by LC-MS as well as those obtained by GC-MS, provided the bile acid content is sufficient.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and reagents

Abbreviations used for bile acids in this paper are based on the nomenclature recommendations reported by Hofmann et al. (10) with a few exceptions: We have used semi-trivial nomenclature for the Δ1-3-one, Δ4-3-one, and Δ4,6-3-one derivatives of the common bile acids by using the abbreviation for the saturated compound. The 3-oxo-5β-cholanoic acid is expressed as LCA-3-one (see Appendix). CA, glycocholic acid (GCA), taurocholic acid (TCA), CDCA, glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDCA), taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA), UDCA, glycoursodeoxycholic acid (GUDCA), tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), LCA, glycolithocholic acid (GLCA), taurolithocholic acid (TLCA), DCA, glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA), taurodeoxycholic acid (TDCA), and hyocholic acid (HCA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). isoDCA, isoLCA, allo-isoLCA, and norDCA were purchased from Steraloids Inc. (Newport, RI). The [2,2,4,4-d4]CA (d4-CA) was obtained from CDD Isotopes Inc. (Quebec, Canada). Unsaturated bile acids with the Δ4-3-one and Δ4,6-3-one configuration in the steroid nucleus for CA and CDCA, as well as sulfated bile acids were kindly donated by Professor Takashi Iida (Nihon University, Tokyo, Japan); methods for their synthesis have been reported (11–15). All other bile acids such as 1β-, 2β-, 4β-, 6α-hydroxylated, Δ5 unsaturated, and C27 bile acids (DHChA and THChA) were from our collection (H.N. and T.K.’s laboratories). The reagents and enzymes, 2-bromoacetophenone, triethylamine (TEA), cholylglycine hydrolase (Clostridium welchii), and sulfatase (type H-1) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All other chemicals used were of the highest grade obtainable except for water and methanol, which were of HPLC grade.

Human subjects

After informed consent was obtained, fecal samples were obtained from three groups of subjects, early cirrhosis, advanced cirrhosis, and age-matched healthy controls. Cirrhotics were diagnosed using biopsy, radiological, or endoscopic evidence. Thirty-eight cirrhotic patients (age 54 ± 3 years, 30 men) and 10 age-matched healthy controls (age 54 ± 3 years, 8 men) provided fresh fecal samples.

Early cirrhotics (n = 17) were Child class A without history of decompensation while advanced cirrhotics (n = 21) had experienced portal hypertensive complications (hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic hydrothorax) or were Child class B or C. The mean model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was 12.4 ± 6.5 and the etiology of cirrhosis was mostly hepatitis C (66%) or alcoholic liver disease (16%). Patients who had been abusing alcohol/illicit drugs over the past 3 months, those currently receiving absorbable antibiotics, subjects having coexisting inflammatory bowel disease or diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome, or subjects currently receiving UDCA therapy were excluded. After collection, stool was thoroughly mixed, and was snap-frozen at −80°C until analysis. The specimen was lyophilized before use.

HPLC method

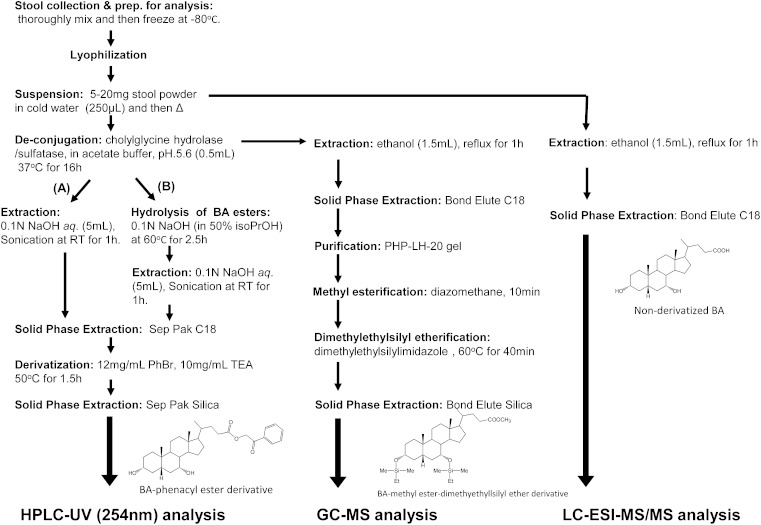

Steps in the extraction and derivatization procedures for the three different methods of fecal bile acid analysis are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Steps in the sample preparation procedures for the three different methods of fecal bile acid analysis.

Extraction and enzymatic deconjugation

Method A: without alkaline hydrolysis step.

The lyophilized stool was thoroughly crushed to a powder before use. Powdered stool (10–20 mg, weighed exactly) was suspended in cold water (250 μl) and heated at 90°C in a screw-capped glass tube for 10 min. If any large particle was still left after heating, it was fragmented using the ultra-sonic bath. Sodium acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 5.6; 250 μl) containing 15 units of cholylglycine hydrolase and 150 units of sulfatase was added, and the solution was incubated at 37°C for 16 h. To stop the reaction, isopropanol (250 μl) was added and the mixture was heated at 90°C for 10 min. An internal standard (IS), 50 nmol of norDCA, and 0.1 N NaOH (3 ml) were added. The bile acids were extracted from the fecal matrix by ultra-sonication in a Branson type B-220 ultra-sonic bath (Danbury, CT) at room temperature for 1 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a glass test tube, and the pellet was washed with 0.1 N NaOH (2 ml). The combined extract was applied to a Waters Sep Pak tC18 cartridge (500 mg sorbent), which had been primed with methanol (10 ml) and water (10 ml). The cartridge was successively washed by water (5 ml), 15% acetone (4 ml), and water (5 ml). Retained bile acids were eluted with methanol (6 ml) and evaporated to dryness under an N2 stream below 40°C.

Method B: with alkaline hydrolysis step.

After the step of cholylglycine hydrolase/sulfatase treatment (see method A), isopropanol (500 μl) and 1 N NaOH (100 μl) were added, and the solution was incubated at 60°C for 2.5 h. An IS, 50 nmol of norDCA, and 0.1 N NaOH (3 ml) were added, and the bile acids were extracted in the same manner as above.

Derivatization of bile acids

Extracted unconjugated bile acids (either by method A or B) were derivatized to their 24-phenacyl esters (16) as follows: to the dried extract, 10 mg/ml of TEA in acetone (150 μl) and 12 mg/ml of phenacyl bromide (2-acetobromophenone) in acetone (150 μl) were added, and the mixture was heated at 50°C with ultra-sonication in a screw-capped glass tube for 1.5 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with acetone (2 ml) and applied to a Waters Sep-Pak® silica cartridge (500 mg sorbent), which had been primed with acetone (5 ml). To elute the bile acid 24-phenacyl esters completely, the column was eluted with acetone (4 ml), and all the collected effluent was dried under an N2 stream.

HPLC analysis

The obtained residue was resuspended in 82% methanol (200 μl), filtered through 0.45 μm filter, and an aliquot (20 μl) was injected to the HPLC instrument: The apparatus used was a Waters Alliance® series 2695 separation module equipped with 2487 dual λ absorbance detector, which was controlled by Empower Pro software. Waters Nova-Pak C18 column (300 mm × 3.9 mm inner diameter (id), particle size 4 μm) fitted with a guard column (20 mm × 3.9 mm id) was used for the separation, which was kept at 32°C during the analysis. Methanol (82%) was used as the mobile phase and its flow rate was kept constant at 0.65 ml/min. Individual bile acid 24-phenacyl esters were detected by monitoring their absorption at 254 nm.

Validation of the HPLC method

For the preparation of standard stock solutions, unconjugated bile acids were dissolved in 90% ethanol at a concentration of 200 μg/ml (500 nmol/ml). The sample was then diluted to the concentrations of 250, 50, 25, and 5 nmol/ml using 90% ethanol. IS stock solution containing norDCA (500 nmol/ml) was also prepared in 90% ethanol. In the calibration study, a 100 μl aliquot of each standard solution or stock solution was mixed with 100 μl of IS solution. A mixture of 500 μl stock solution and 100 μl of IS solution was also prepared. After evaporation under an N2 stream below 40°C, the bile acid mixture was subjected to the derivatization reaction as above. Each concentration of bile acid phenacyl ester mixture was dissolved in 200 μl of 90% methanol and a 20 μl aliquot was injected to the HPLC. Calibration curves were constructed by the peak-area ratio of each bile acid to the IS. For the recovery rate test, 100 μl aliquots of 50 or 500 nmol/ml stock solutions were spiked into the dried stool and the samples were subjected to the above entire clean-up and derivatization process (method A, without alkaline hydrolysis). The recovery (percent ± SD) was calculated as [observed concentration/(unspiked concentration + spiked concentration)] × 100 (n = 5).

In order to check the deconjugation rate of the N-acylamidated bile acids, 500 nmol/ml of selected glycine and taurine amidated bile acid standard mixtures were also prepared, as above. A 100 μl aliquot of the respective stock solutions was spiked into the dried stool (10 mg). After incubation with cholylglycine hydrolase, the sample was processed and derivatizated (method A, without alkaline hydrolysis). The deconjugation rate was defined as the analytical recovery (percent) in the same manner as above (n = 4 for each sample).

Analysis of fecal bile acids by LC-ESI-MS/MS

The LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis was conducted based on our previous method (17) with modification: 5.0 mg of lyophilized stool (see HPLC method A) was suspended in 50 mM cold sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.6, 0.5 ml) and then refluxed with ethanol (1.5 ml) for 1 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was diluted four times with water and applied to a Bond Elute C18 cartridge (500 mg/6 ml; Varian, Harbor City, CA). The cartridge was then washed with 25% ethanol (5 ml) and bile acids were eluted with ethanol (5 ml). After the solvent was evaporated, the residue was dissolved in 1 ml of 50% ethanol. To an aliquot (100 μl) of this solution, 0.9 ml of 50% ethanol and 1 ml of IS ([2,2,4,4-d4]CA, 200 pmol/ml in 50% ethanol) was added. Precipitated solids were removed by filtration through a 0.45 μm Millipore filter (Millex®-LG; Billerica, MA). A 10 μl aliquot of the filtrate was injected into the LC-ESI-MS/MS system. The LC-ESI-MS/MS system consisted of a TSQ Quantum Discovery Max mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) equipped with an ESI probe and Surveyor HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). InertSustain C18 column (150 mm × 2.1 mm id, 3 μm particle size; G and L Science, Tokyo, Japan) was employed at 40°C. A mixture of 5 mM ammonium acetate, ethanol, and methanol was used as the eluent, and the separation was carried out by linear gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. The mobile phase composition of ethanol and methanol was gradually changed as follows: ammonium acetate-ethanol (8:2, v/v) for 0–3 min, ammonium acetate-methanol (8:2, v/v) at 3.1 min, ammonium acetate-methanol (2:98, v/v) for 3.1–42 min, ammonium acetate-methanol (2:98, v/v) for 42–46 min; the column was reequilibrated for 4 min. The total run time was 50 min. To operate the LC-ESI-MS/MS, the spray voltage and vaporizer temperature were set at 3,500 V and 330°C, respectively. The sheath and auxiliary gas (nitrogen) pressure were set at 50 and 10 arbitrary units, respectively, and the ion transfer capillary temperature was carried out at 330°C. The collision gas (argon) pressure and the collision energy were kept at 1.3 mm Torr and 27–55 eV, respectively, all in the negative ion mode.

Analysis of fecal bile acids by GC-MS

Lyophilized stool powder (5.0 mg, weighed exactly) was heated with water, and then incubated with cholylglycine hydrolase/sulfatase for 16 h as described in the HPLC section. Ethanol (1.5 ml) was added and the solution was refluxed for 1 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was evaporated under an N2 stream. The extracted bile acids were resuspended in 1 ml of 90% aqueous ethanol and applied to a piperidinohydroxypropyl Sephadex LH-20 (PHP-LH-20) (18) column (30 × 6 mm id) which had been primed with 90% aqueous ethanol. The column was washed with 90% ethanol (4 ml) and the unconjugated bile acids were eluted with 0.1 N acetic acid in 90% ethanol (5 ml). After evaporation, the purified bile acids were derivatizated to their corresponding methyl ester-dimethylethylsilyl ether derivatives as previously described (15). GC-MS was performed with a Hewlett Packard 5890 gas chromatograph and Hewlett Packard 5973 mass selective detector instrument (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) using a DB-5MS gas chromatographic column (30 m × 0.25 mm id, and a 0.25 μm-film-fused silica capillary column (Agilent). The column temperature was programmed to rise from 170°C to 230°C/min at 10°C/min, from 230°C to 300°C at 5°C/min, and to remain at 300°C at 20 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas with the flow rate of 1.4 ml/min. The mass spectra were recorded at an ionization energy of 70 eV with an ion source temperature of 250°C.

RESULTS

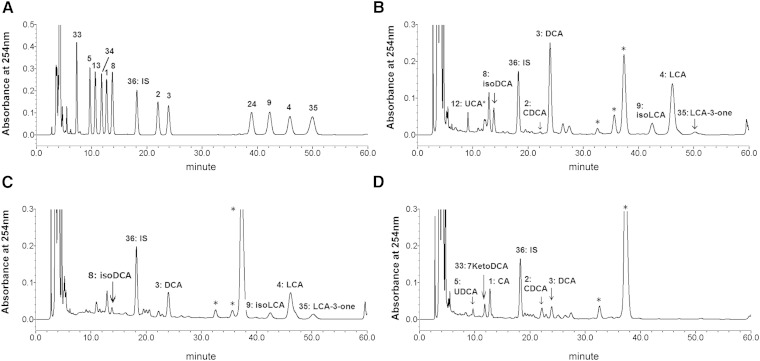

A chromatogram using bile acid standards is shown in Fig. 2A. The retention times, calibration curves, and quantification and detection limits of each bile acid are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The calibration curves showed excellent linearity for a 500-fold dynamic range for all bile acids that were examined (correlation coefficient >0.999 for most bile acids). The detection [signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) > 3] and quantification (S/N > 10) limits were 1.2–1.5 pmol and 2.4–7.3 pmol applied to the column, respectively, depending on the bile acid species. The assay validation in Table 3 shows excellent recovery of seven dominant fecal bile acids from the fecal matrix. The assay accuracy, which was defined as analytical recovery of calibration standards at nominal bile acid levels (5 and 50 nmol), was satisfactory, ranging from 85 to 102% (except for UDCA which was 72%). The recoveries of the taurine and glycine conjugated bile acids by the cholylglycine hydrolase treatment are also shown in Table 3. The deconjugation reaction was almost quantitative (90–104%) for most conjugated bile acids except GUDCA, which was 82%.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of HPLC chromatographic patterns of the bile acid 24-phenacyl esters. Typical HPLC chromatogram of the standard bile acid phenacyl esters (A), and the representative chromatographic patterns of the healthy control (B), early cirrhosis (C), and advanced cirrhosis (D). The analytical conditions are detailed in the Experimental Procedures. The number on each peak represents the compound number in the appendix: 1, CA; 2, CDCA; 3, DCA; 4, LCA; 5, UDCA; 8, isoDCA; 9, isoLCA; 11, HCA; 24, isoLCA-Δ5 ; 33, 7KetoDCA; 34, 7KetoLCA; 36, norDCA (IS); 35, LCA-3-one. *Unknown peaks but not bile acids confirmed by the GC-MS and LC-MS analysis.

TABLE 1.

Retention data of bile acid 24-phenacyl esters

| CA (1) | CDCA (2) | DCA (3) | LCA (4) | UDCA (5) | isoDCA (8) | isoLCA (9) | isoLCA-Δ5 (24) | 7Keto-DCA (33) | 7Keto-LCA (34) | LCA-3-one (35) | norDCA (IS) (36) | |

| Retention time (min) | 12.70 ± 0.03 | 22.05 ± 0.06 | 23.98 ± 0.06 | 46.08 ± 0.12 | 9.68 ± 0.03 | 13.76 ± 0.04 | 42.39 ± 0.12 | 39.07 ± 0.11 | 7.27 ± 0.02 | 11.78 ± 0.03 | 50.14 ± 0.14 | 18.21 ± 0.05 |

| Relative retention time to IS | 0.70 ± 0.00 | 1.21 ± 0.00 | 1.32 ± 0.00 | 2.53 ± 0.00 | 0.53 ± 0.00 | 0.76 ± 0.00 | 2.33 ± 0.00 | 2.15 ± 0.00 | 0.40 ± 0.00 | 0.65 ± 0.00 | 2.75 ± 0.00 | — |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 7). Abbreviations of bile acids and their compound numbers in parentheses are given in the Appendix.

TABLE 2.

Calibration curve, limit of detection, and limit of quantification for selected bile acids

| Equation | Correlation Coefficient (r2) | LOD (pmol) | LOQ (pmol) | |

| CA (1) | y = 0.3380x + 0.0045 | 0.9999 | 1.22 | 2.44 |

| CDCA (2) | y = 0.3471x − 0.0027 | 0.9999 | 1.34 | 2.68 |

| DCA (3) | y = 0.3122x − 0.0038 | 0.9999 | 1.27 | 5.08 |

| LCA (4) | y = 0.3646x − 0.0098 | 0.9996 | 1.33 | 5.31 |

| UDCA (5) | y = 0.3842x − 0.0028 | 0.9999 | 1.28 | 2.56 |

| isoDCA (8) | y = 0.3704x − 0.0034 | 0.9999 | 1.34 | 2.68 |

| isoLCA (9) | y = 0.3756x − 0.0121 | 0.9995 | 1.46 | 7.30 |

Limit of detection (LOD), S/N > 3; limit of quantification (LOQ), S/N > 10 (on column). Abbreviations of bile acids and their compound numbers in parentheses are given in the Appendix.

TABLE 3.

Recovery of selected bile acids

| 5 nmol |

50 nmol |

|||||

| Added (nmol) | Found (nmol) | Recovery (%) | Added (nmol) | Found (nmol) | Recovery (%) | |

| Unconjugated bile acids | ||||||

| CA (1) | 4.9 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 99.9 ± 10.1 | 49.0 | 49.9 ± 3.2 | 102.0 ± 6.4 |

| CDCA (2) | 5.3 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 100.0 ± 8.2 | 53.5 | 51.8 ± 1.1 | 96.8 ± 1.9 |

| DCA (3) | 5.1 | 4.7 ± 0.81 | 91.9 ± 17.1 | 50.9 | 51.8 ± 4.0 | 102.1 ± 7.7 |

| LCA (4) | 5.3 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 89.7 ± 9.3 | 53.1 | 52.3 ± 4.0 | 98.5 ± 7.6 |

| UDCA (5) | 5.1 | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 72.1 ± 18.3 | 50.9 | 36.9 ± 2.3 | 72.3 ± 5.0 |

| isoDCA (8) | 5.4 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 93.3 ± 4.9 | 53.4 | 45.6 ± 1.1 | 85.3 ± 2.1 |

| isoLCA (9) | 5.9 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 92.2 ± 9.8 | 58.4 | 56.6 ± 2.1 | 96.8 ± 3.6 |

| N-acylamidated bile acids | ||||||

| GCA (39) | — | — | — | 51.3 | 49.2 ± 1.1 | 96.0 ± 2.2 |

| GCDCA (40) | — | — | — | 55.1 | 53.0 ± 2.6 | 96.1 ± 4.7 |

| GUDCA (41) | — | — | — | 54.1 | 44.4 ± 2.5 | 82.2 ± 4.6 |

| GDCA (42) | — | — | — | 54.1 | 55.3 ± 1.5 | 102.2 ± 2.7 |

| TCA (44) | — | — | — | 47.4 | 42.7 ± 2.0 | 90.1 ± 4.3 |

| TCDCA (45) | — | — | — | 49.8 | 48.2 ± 2.8 | 96.6 ± 5.6 |

| TUDCA (46) | — | — | — | 49.4 | 45.0 ± 2.5 | 104.2 ± 5.2 |

| TDCA (47) | — | — | — | 47.9 | 46.8 ± 2.4 | 97.6 ± 5.1 |

Results are expressed as percent ± SD; n = 5 for unconjugated bile acids, n = 4 for conjugated bile acids. Abbreviations of bile acids and their compound numbers in parentheses are given in the Appendix.

HPLC analysis of nonesterified fecal bile acids in healthy and cirrhotic subjects

Method A.

The method was then applied to the determination of fecal bile acid concentration in samples from patients with cirrhosis (17 early and 21 advanced) and from 10 healthy controls. The major fecal bile acids in the healthy subjects consisted predominantly of secondary bile acids (i.e., LCA and DCA) and their stereoisomers (i.e., isoLCA, alloLCA, isoDCA, and alloDCA), as expected (19–23). The composition of fecal bile acids in stools from cirrhotic patients differed in both concentration and profile (7). In cirrhotic fecal bile acids, some samples contained conjugated bile acids, explaining the necessity of adding the enzymatic deconjugation step (taurine-conjugated bile acids do not form phenacyl esters). Therefore, after heating at 90°C with water for 10 min (to kill bacteria which could change bile acid profile), the stool was incubated with 15 units of cholylglycine hydrolase and 150 units of sulfatase in 50 mM NaOAc (pH 5.6) buffer overnight. The deconjugated bile acids were then extracted with 0.1 N NaOH at room temperature, and applied to the C18 solid-phase extraction column. The obtained unconjugated bile acids were derivatized to the 24-phenacyl esters as described in the Experimental Procedures. The representative chromatograms of a healthy control, a patient with early cirrhosis, and a patient with advanced cirrhosis are shown in .

The assay results for all 48 samples are also summarized in Table 4. In addition to total bile acid concentrations (sum of all examined bile acids), the sum of CA, CDCA, DCA, LCA, isoDCA, isoLCA, UDCA, and HCA (subtotal), which were common bile acids examined by three different methods, are also presented for comparison. Total bile acids were significantly lower in the advanced cirrhosis group. The median concentrations of total bile acids in healthy (n = 10), early cirrhosis (n = 17), and advanced cirrhosis (n = 21) were 6.7, 4.0, and 1.3 μmol/g of dried feces, respectively. In fecal bile acids from healthy subjects, the main bile acids (mean ± SD percent) were DCA (61 ± 15%) and LCA (21 ± 12%), followed by 3β-hydroxy isomers of DCA and LCA (5 ± 2% and 4 ± 3%, respectively). In samples from advanced cirrhotic patients, the main bile acids were CA (29 ± 19%) and CDCA (18 ± 16%), followed by DCA and LCA (19 ± 23% and 13 ± 24%, respectively).

TABLE 4.

Median concentrations of individual bile acids obtained by the HPLC method without alkaline hydrolysis (method A)

| Control (n = 10) (μmol/g) | Early (n = 17) (μmol/g) | Advanced (n = 23) (μmol/g) | |

| Totala | 6.69 | 3.98 | 1.30 |

| Subtotalb | 6.61 | 3.81 | 1.14 |

| CA (1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.24 |

| CDCA (2) | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

| DCA (3) | 3.84 | 0.89 | 0.08 |

| LCA (4) | 1.46 | 0.78 | 0.00 |

| UDCA (5) | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| isoDCA (8) | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| isoLCA (9) | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| HCA (11) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| HDCA (13) | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| isoLCA-Δ5 (24) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 7ketoLCA (33) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 7ketoDCA (34) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| LCA-3-one (35) | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

Sum of all the bile acid species examined by this method.

Sum of CA, CDCA, DCA, LCA, isoDCA, isoLCA, UDCA, and HCA which are common bile acid species examined by three different methods. Abbreviations of bile acids and their compound numbers in parentheses are given in the Appendix.

Method B.

Some fecal bile acids have been reported to be present in esterified form, i.e., ethyl esters of LCA and isoLCA (24), long-chain fatty acid esters of LCA (25), polyesters of DCA (26), or undefined esters of DCA and isoDCA (27). These esterified bile acids could constitute up to 25% of total fecal bile acids (20, 27).

To estimate the proportion of this fraction, we optimized a mild hydrolysis procedure using two synthetic standards, ethyl lithocholate and ethyl lithocholyl stearate. By method A, in which aqueous 0.1 N NaOH was utilized, these two esters were not cleaved, probably due to their insolubility. To obtain complete hydrolysis using methanolic 0.1 N NaOH, a higher temperature and/or prolonged incubation was required. When 0.1 N NaOH in 50% isopropanol (containing 50% water) was used, these two bile acid esters were efficiently cleaved at 60°C in 2 h (supplementary Figs. III, IV). Based on the results, we included this hydrolysis procedure in the steps shown in Fig. 1, and reanalyzed all the 48 samples (12 healthy and 38 cirrhotic specimens). The result was compared with those obtained without hydrolysis (see Table 5). In samples from both healthy subjects and cirrhotic patients, the observed total bile acid concentration was significantly higher compared with those observed without hydrolysis. The total concentrations were 9.4 μmol/g (28% increased), 7.7 μmol/g (48% increased), and 1.9 μmol/g (31% increased) in control, early, and advanced cirrhosis, respectively. These results suggest that the alkaline hydrolysis step was necessary to include, despite being time-consuming.

TABLE 5.

Median concentrations of individual bile acids obtained by the HPLC method with alkaline hydrolysis (method B)

| Control (n = 10) (μmol/g) | Early (n = 17) (μmol/g) | Advanced (n = 21) (μmol/g) | |

| Totala | 9.36 (28.5)c | 7.72 (48.4) | 1.9 (31.6) |

| Subtotalb | 8.51 (22.3) | 7.16 (46.7) | 1.9 (40.0) |

| CA (1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.62 (61.3) |

| CDCA (2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.18 (33.3) | 0.35 (57.1) |

| DCA (3) | 4.18 (8.1) | 1.75 (49.1) | 0.21 (61.9) |

| LCA (4) | 2.07 (29.5) | 2.5 (68.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| UDCA (5) | 0.07 (85.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.08 (100) |

| isoDCA (8) | 0.6 (31.7) | 0.2 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| isoLCA (9) | 0.29 (24.1) | 0.35 (74.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| HCA (11) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| HDCA (13) | 0.3 (13.3) | 0.04 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| isoLCA-Δ5 (24) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 7ketoLCA (33) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 7ketoDCA (34) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| LCA-3-one (35) | 0.05 (0.0) | 0.09 (44.4) | 0 (0.0) |

Sum of all the bile acid species examined by this method.

Total of CA, CDCA, DCA, LCA, isoDCA, isoLCA, UDCA, and HCA which are common bile acid species examined by three different methods; Abbreviations of bile acids and their compound numbers in parentheses are given in the Appendix.

The numbers in the parentheses are percent increasing from the values obtained without hydrolysis (Table 4).

LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of fecal bile acids in healthy and cirrhotic subjects

In order to validate our new HPLC method, we compared it with LC-ESI-MS/MS by our recently developed technique (17) with modification (see Experimental Procedures). LC-MS and GC-MS methods in this study did not include an ester hydrolysis step. Therefore, we used these data to compare three analytical procedures in nonesterified bile acids. The quantification results of the 10 healthy and 38 (17 early and 21 advanced) cirrhotic subjects are shown in Table 6. The 36 variants of C24 bile acids, which included the unconjugated, N-acylamidates conjugated with glycine or taurine at C-24 in the side chain, as well as the C-3 sulfated bile acids, were examined. The retention times and transitions used in the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) for the examined bile acids were shown in our previous report (17). The primary bile acids in the advanced cirrhotic subjects presented not only unconjugated forms but conjugated forms. The conjugated bile acids included N-acylamidate (conjugated with glycine or taurine) forms, with 3-sulfated and doubly conjugated bile acids (N-acylamidate-sulfates). The percent (mean ± SD) of these conjugated bile acids in total bile acid was 19 ± 27% in advanced cirrhosis. In the control and early cirrhosis group, such conjugated bile acid levels were much smaller, 2.6 ± 4.8% and 2.7 ± 4.3%, respectively.

TABLE 6.

Median concentrations (μmol/g) of all the tested BAs obtained by the LC-MS method

| Control (n = 10) (μmol/g) | Early (n = 17) (μmol/g) | Advanced (n = 23) (μmol/g) | ||

| Totala | 4.47 | 4.50 | 1.05 | |

| Subtotalb | 4.47 | 4.50 | 1.05 | |

| Unconjugated bile acids | ||||

| 1 | CA | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| 2 | CDCA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| 3 | DCA | 1.87 | 1.05 | 0.01 |

| 4 | LCA | 1.48 | 0.91 | 0.00 |

| 5 | UDCA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 8 | isoDCA | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.00 |

| 9 | isoLCA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 10 | allo-iso-LCA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 11 | HCA | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| Total unconjugated | 4.44 | 3.91 | 1.05 | |

| Percent total unconjugated (mean ± SD) | 97.4 ± 4.8 | 97.4 ± 4.3 | 81.2 ± 27.6 | |

| N-acylamidated (glycine and taurine) bile acids | ||||

| 39–48c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Total amidated | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Percent total amidated (mean ± SD) | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 2.4 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | |

| Sulfated bile acids | ||||

| 52 | DCA3S | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 49–51,53c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Total sulfated | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.07 | |

| Percent total sulfated (mean ± SD) | 2.5 ± 4.7 | 1.7 ± 3.4 | 16.3 ± 25.6 | |

| Double conjugated bile acids | ||||

| 54–63c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Total double conjugated | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Percent total double conjugated (mean ± SD) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.17 | 2.1 ± 6.4 | |

| Total conjugated | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.08 | |

| Percent total conjugated (Mean ±SD) | 2.6 ± 4.8 | 2.7 ± 4.3 | 18.6 ± 27.3 |

Sum of all the bile acid species examined by this method.

Total of CA, CDCA, DCA, LCA, isoDCA, isoLCA, UDCA, HCA and their conjugated forms, which are common bile acid species examined by three different methods.

Bile acids denoted by the compound numbers are given in the Appendix.

GC-MS analysis of fecal bile acids in healthy and cirrhotic subjects

We analyzed these 48 stools by the validated GC-MS method. The main advantage of the GC-MS method is that the separations on the capillary GC column are superior to those obtained in liquid-phase separations. Therefore, the 33 variants of structurally different unconjugated bile acids, which included abnormal unsaturated bile acids (i.e., Δ5-bile acids), uncommon trihydroxy and tetrahydroxy bile acids (i.e., 1β-hydroxy-CA, 4β-hydroxy-CDCA), and C27 bile acids (THChA and DHChA), could be detected. The quantifications of these bile acids in the 48 healthy and cirrhosis specimens are shown in Table 7. Although small amounts of Δ5-bile acids (i.e., isoLCA-Δ5 and isoDCA-Δ5) were detected in samples from cirrhotic patients; these bile acids were detected in some control samples, as well. There were no significant differences in their amounts between the control group and the cirrhosis group. Also, trace amounts of an unusual bile acid, DCA-1β-ol were detected; however, the differences were not significant between groups. These unusual bile acids were less than 2% of total bile acids and were not deemed selective for cirrhosis.

TABLE 7.

Median concentrations of all the examined bile acids obtained by the GC-MS method

| Control (n = 10) | Early (n = 17) | Advanced (n = 23) | ||

| μmol/g |

||||

| Totala | 4.93 | 3.63 | 1.18 | |

| Subtotalb | 4.77 | 3.53 | 0.85 | |

| Usual bile acids | ||||

| 1 | CA | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| 2 | CDCA | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| 3 | DCA | 3.25 | 1.27 | 0.01 |

| 4 | LCA | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| 5 | UDCA | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 8 | isoDCA | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| 9 | isoLCA | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| 11 | HCA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 6, 7, 10, 12c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Unsaturated bile acids | ||||

| 15–22c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 24 | isoLCA-Δ5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| 23 | isoDCA-Δ5 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Hydroxylated bile acids | ||||

| 25–31c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 32 | DCA-1β-ol | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| C27 bile acids | ||||

| 37, 38c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

Sum of all the bile acid species examined by this method.

Total of CA, CDCA, DCA, LCA, isoDCA, isoLCA, UDCA, and HCA which are common bile acid species examined by three different methods.

Bile acids denoted by the compound numbers are given in the appendix.

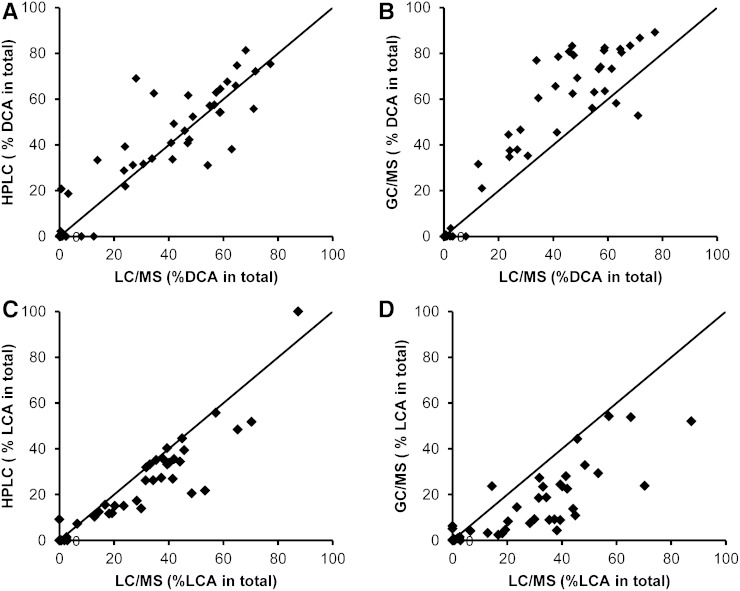

Comparison of the three methods in fecal bile acid quantifications in cirrhosis

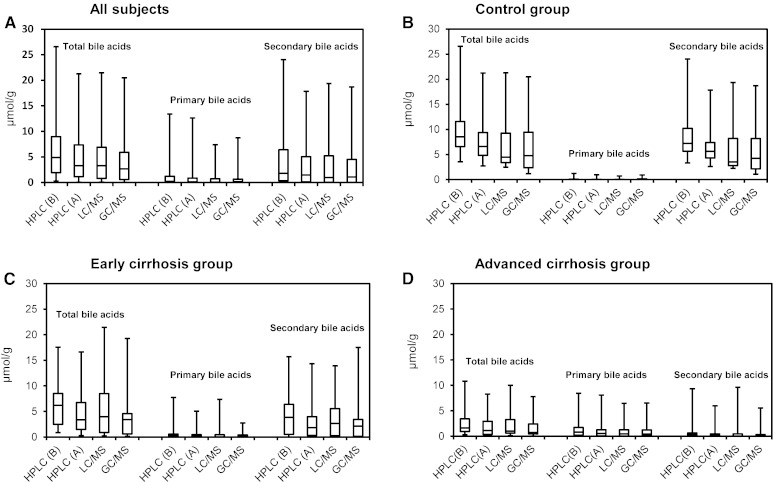

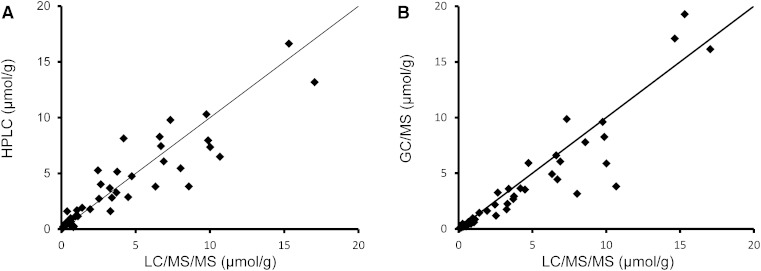

In Fig. 3A–D, the distribution of total bile acid concentrations as well as primary (CA and CDCA) and secondary (DCA and LCA) bile acid concentrations in all subjects, controls, early and advanced cirrhotic specimens obtained by three different methods were compared. These median values as well as ratios of primary to secondary bile acids are also shown in Table 8. Because the LC-MS and GC-MS methods in this study did not include an ester hydrolysis step, these data were directly comparable to those of HPLC obtained by method A. Although the solvents used for the extraction of bile acids were different (0.1 N NaOH or ethanol), their extraction efficiencies were essentially the same, as confirmed by analysis of selected samples (supplementary Table I). The concentrations of each bile acid obtained by LC-MS are expressed as unconjugated forms combined with their conjugated forms (sulfates and N-acylamidates). In the control group, the total bile acid value obtained by HPLC (6.6 μmol/g) was slightly higher than those obtained by LC-MS (4.5 μmol/g) and GC-MS (4.8 μmol/g). This overestimation in HPLC was probably due to the overlapping of the bile acid peaks with matrix components or possibly to partial hydrolysis of esterified bile acids in the 0.1 N NaOH (or both). In addition, matrix components could have influenced values obtained by LC-MS and GC-MS (ion suppression effect). However, these differences were much smaller (or not seen) within the cirrhosis group: in early cirrhosis 3.8 (HPLC) versus 4.5 (LC-MS) and 3.5 (GC-MS); in advanced cirrhosis, 1.1 (HPLC) versus 1.1 (LC-MS) and 0.9 (GC-MS) μmol/g. Figure 4 plots the correlations of total bile acid concentrations in the individual 48 subjects between three methods. In Fig. 5A–D, the percent of two major fecal bile acids, DCA and LCA, in individual subjects obtained by the HPLC and GC-MS were plotted against those obtained by LC-MS/MS. The percent of primary bile acids (CA + CDCA) and secondary bile acids (DCA + LCA) in total bile acid agreed well between the three methods. The percentages of primary bile acids (mean ± SD) obtained in the control group were 1.2 ± 3.0% (HPLC), 1.2 ± 3.0% (LC-MS), and 1.9 ± 2.6% (GC-MS), respectively. These percent values in early cirrhosis were 13.7 ± 27.4% (HPLC), 14.6 ± 30.8% (LC-MS), and 11.7 ± 19.4% (GC-MS); and in advanced cirrhosis were 47.4 ± 31.0% (HPLC), 51.9 ± 38.9 (LC-MS), and 45.7 ± 34.9% (GC-MS). The percentages of secondary bile acids in the control group were 82.8 ± 5.9% (HPLC), 86.1 ± 6.1% (LC-MS), and 86.7 ± 6.2%(GC-MS); in early cirrhosis were 63.7 ± 29.6% (HPLC), 69.0 ± 33.2% (LC-MS), and 66.4 ± 33.3% (GC-MS); and in advanced cirrhosis were 15.6 ± 37.4% (HPLC), 8.1 ± 39.9 (LC-MS), and 7.9 ± 34.3% (GC-MS).

Fig. 3.

Box plots for the comparisons of different methods in total, primary (CA + CDCA), and secondary (DCA + LCA) bile acid concentrations: all subjects (n = 48) (A), healthy controls (n = 10) (B), early cirrhosis (n = 17) (C), and advanced cirrhosis (n = 21) (D).

TABLE 8.

Comparison of median primary and secondary bile acid levels obtained by three different methods

| HPLC (Method A without Hydrolysis) (μmol/g) |

HPLC (Method B with Hydrolysis) (μmol/g) |

LC/MS (μmol/g) |

GC/MS (μmol/g) |

|||||||||

| Ct | Erly | Adv | Ct | Erly | Adv | Ct | Erly | Adv | Ct | Erly | Adv | |

| Totala | 6.61 | 3.81 | 1.14 | 8.51 | 7.16 | 1.90 | 4.47 | 4.50 | 1.05 | 4.77 | 3.53 | 0.85 |

| Primary bile acids | ||||||||||||

| CA | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| CDCA | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.15b | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.35b | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.17b | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.16b |

| CA + CDCA | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.54b | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.95b | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.54b | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.49b |

| Secondary bile acids | ||||||||||||

| DCA | 3.84 | 0.89 | 0.08b | 4.18 | 1.75 | 0.21b | 1.88 | 1.05 | 0.02b | 3.25 | 1.27 | 0.01b |

| LCA | 1.46 | 0.78 | 0.00b | 2.07 | 2.50 | 0.00b | 1.48 | 0.91 | 0.01b | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.02b |

| DCA + LCA | 5.64 | 2.22 | 0.16b | 7.21 | 4.06 | 0.32b | 3.51 | 2.88 | 0.04b | 4.25 | 2.29 | 0.03b |

| Ratios of primary and secondary bile acids | ||||||||||||

| DCA/CA | — | 0.55 | 0.00b | — | 0.79 | 0.03b | 116.49 | 13.17 | 0.05b | 111.48 | 27.52 | 3.47b |

| LCA/CDCA | 10.29 | 5.41 | 0.00b | 12.93 | 7.63 | 0.00b | 16.74 | 4.12 | 0.01b | 15.81 | 7.84 | 0.26b |

| DCA + LCA/CA + CDCA | 48.62 | 17.30 | 0.01b | 58.12 | 14.59 | 0.04b | 149.91 | 14.41 | 0.04b | 77.04 | 29.65 | 0.05b |

Total bile acids, total and individual secondary bile acids, and secondary/primary bile acid ratios were significantly lower while total primary bile acids especially CDCA were significantly higher in advanced cirrhosis compared with the rest of the groups using all three methods. CA levels were not different between groups using any of the techniques.

P < 0.05 using Kruskal Wallis test.

Fig. 4.

Correlations of total bile acid concentrations between the methods: present HPLC/UV and LC/MS (A) and GC/MS and LC/MS (B).

Fig. 5.

Correlations of secondary bile acid compositions (percent) between the methods: HPLC versus LC/MS in DCA (A), GC/MS versus LC/MS in DCA (B), HPLC versus LC/MS in LCA (C), and GC/MS versus LC/MS in LCA (D).

Comparison of healthy versus cirrhotic patients

The total bile acid concentration was significantly lower in advanced cirrhotics compared with the other groups (Table 8). The concentration of secondary bile acids was highest in controls and lowest in advanced cirrhosis. The ratios of all secondary to primary bile acids, and specifically of DCA/CA and LCA/CDCA, were also lowest in advanced cirrhosis. This significant change was consistent across all three methodologies (Fig. 3A–D). This increase of secondary bile acids in cirrhosis is due to changes in the intestinal microbial flora, and the finding agrees with our recently published results (7) as well as an older study by Vlahcevic et al. (28).

DISCUSSION

We have developed an accurate but simple method for routine fecal bile analysis in healthy and cirrhotic patients using conventional HPLC-UV. In addition, we have compared our new HPLC method with LC-ESI-MS/MS and GC-MS. When available, LC-MS is the most reliable method for the quantification of bile acids (2). However, its high running cost, required technical expertise, and accessibility are frequent issues, particularly when considering it for routine use. Therefore, these issues necessitate simpler methods for routine fecal bile acid analysis.

The UV detection of unconjugated bile acids, the form in which bile acids predominate in fecal bile acids, is impossible because of their poor UV absorbance (2, 8, 9). Also, enzymatic methods using 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (29, 30) do not detect iso (3β-hydroxy) bile acids, which can be a major component of fecal bile acids (19–22, 31). Therefore, introduction of an UV-absorbing group into the bile acid molecule is necessary for the sensitive and selective detection of unconjugated bile acids in the complex fecal matrix. Among various kinds of derivatization reagents (8), phenacyl ester derivatization to the carboxyl group at C-24 (16) was judged by us to be the most suitable for the present purpose for the following reasons: 1) The reaction was quantitative with a very simple procedure; bile acids were simply mixed with TEA and 2-acetobromophenone in acetone, and the reaction was complete in 1.5 h at 50°C. 2) The resulting bile acid 24-phenacyl esters were well-separated on a C18 column with a simple neutral mobile phase, 82% aqueous methanol. 3) The absorbance of bile acid-phenacyl esters at 254 nm is excellent, providing high sensitivity; and in addition, there is little interference by non-bile acid constituents at this wavelength.

In our HPLC method, total bile acids were derivatized to their corresponding 24-phenacyl esters after deconjugation of conjugated bile acids and hydrolysis of esterified bile acids. The procedure was simple as well as accurate especially for samples containing >2 μmol/g. The whole procedure can be completed in a day after the enzymatic deconjugation (overnight incubation) and alkaline hydrolysis of esterified bile acids (2.5 h incubation). This includes extraction, derivatization, and HPLC running time, and importantly, multiple samples can be processed simultaneously. Although highly simplified methods for extraction of fecal bile acids have been proposed, many of them are not suitable for the fecal analysis in conditions such as cirrhosis where conjugated bile acids are present in appreciable proportions (2). Furthermore, these methods often neglect esterified bile acids and omit a weak alkaline hydrolysis step. Recently, representative extraction methods were compared by Humbert et al. (23), and this group also concluded that using 0.1 N NaOH with heating was the most efficient for fecal bile acid extraction.

We have also reported a simplified LC-MS method for the quantification of bile acids in human urine (17), and that technique was modified for fecal bile acids as reported here. The advantage of this technique compared with the HPLC technique herein reported is that the former provides information on a variety of conjugated bile acids that can be present. These include not only N-acylamidates (glycine and taurine), but also sulfates and sulfated amidates (double conjugates).

GC-MS is the traditional method for measurement of fecal bile acids, as first reported by Grundy, Ahrens, and Mietinnen (32). The advantage of GC-MS is that the separation of bile acids on the capillary GC column is superior to that obtained in liquid-phase separations. In addition, the electron impact mass spectra provide more structural information than can be obtained in the LC-ESI-MS/MS method. We included GC-MS in our study to determine whether there were any unusual fecal bile acids in patients with cirrhosis. We examined 33 structurally different unconjugated bile acids, which included unsaturated bile acids (i.e., Δ5-bile acids), abnormal hydroxylated bile acids (i.e., 1β-hydroxylated CA and 4β-hydroxylated CDCA), and C27 bile acids (THChA and DHChA). However, these abnormal bile acids were not found in any significant amounts in the spectra in healthy or cirrhotic patients. The information obtained from this was similar to that obtained by the HPLC method, but the GC-MS method requires more time-consuming deconjugation, purification, and precolumn derivatization steps prior to analysis, an obvious disadvantage.

Thus, we have developed a simple, economical, and accurate method for determining total bile acids and the bile acid profile in fecal samples. We have compared our method with the index methods of LC-MS and GC-MS and summarized the strengths and weakness of each method. We have applied our method to clinical samples that span the gamut from healthy controls through advanced cirrhosis and found that this technique was able to detect varying concentrations of total, conjugated, and unconjugated bile acids consistent with LC-MS and GC-MS.

APPENDIX

Abbreviations and trivial names of unconjugated, N-acylamidated (with glycine or taurine), and sulfated bile acids used in this study

| Abbreviations | Trivial Names | |

| Saturated bile acids | ||

| 1 | CA | Cholic acid |

| 2 | CDCA | Chenodeoxycholic acid |

| 3 | DCA | Deoxycholic acid |

| 4 | LCA | Lithocholic acid |

| 5 | UDCA | Ursodeoxycholic acid |

| 6 | alloCA | 3α,7α,12α-Trihydroxy-5α-cholan-24-oic acid |

| 7 | alloCDCA | 3α,7α-Dihydroxy-5α-cholan-24-oic acid |

| 8 | isoDCA | 3β,12α-Dihydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid |

| 9 | isoLCA | 3β-Hydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid |

| 10 | allo-isoLCA | 3β-Hydroxy-5α-cholan-24-oic acid |

| 11 | HCA | Hyocholic acid |

| 12 | UCA | Ursocholic acid |

| 13 | HDCA | Hyodeoxycholic acid |

| 14 | MDCA | Murideoxycholic acid |

| Unsaturated bile acids | ||

| 15 | CA-Δ1-3-one | 7α,12α,-Dihydroxy-3-oxo-1-cholen-24-oic acid |

| 16 | CA-Δ4-3-one | 7α,12α,-Dihydroxy-3-oxo-4-cholen-24-oic acid |

| 17 | CA-Δ4,6-3-one | 7α,12α,-Dihydroxy-3-oxo-4,6-choladien-24-oic acid |

| 18 | CDCA-Δ4-3-one | 7α-Hydroxy-3-oxo-4-cholen-24-oic acid |

| 19 | CDCA-Δ4,6-3-one | 7α-Hydroxy-3-oxo-4,6-choladien-24-oic acid |

| 20 | isoCA-Δ5 | 3β,7α,12α-Trihydroxy-5-cholen-24-oic acid |

| 21 | isoCDCA-Δ5 | 3β,7α-Dihydroxy-5-cholen-24-oic acid |

| 22 | isoUDCA-Δ5 | 3β,7β-Dihydroxy-5-cholen-24-oic acid |

| 23 | isoDCA-Δ5 | 3β,12α-Dihydroxy-5-cholen-24-oic acid |

| 24 | isoLCA-Δ5 | 3β-Hydroxy-5-cholen-24-oic acid |

| Hydroxylated bile acids at uncommon position | ||

| 25 | CA-1β-ol | 1β,3α,7α,12α-Tetrahydroxy-5β-cholan 24-oic acid |

| 26 | CA-2β-ol | 2β,3α,7α,12α-Tetrahydroxy-5β-cholan 24-oic acid |

| 27 | isoCA-4β-ol | 3β,4β,7α,12α-Tetrahydroxy-5β-cholan 24-oic acid |

| 28 | CA-6α-ol | 3α,6α,7α,12α-Tetrahydroxy-5β-cholan 24-oic acid |

| 29 | CDCA-1β-ol | 1β,3α,7α-Trihydroxy-5β-cholan 24-oic acid |

| 30 | CDCA-2β-ol | 2β,3α,7α-Trihydroxy-5β-cholan 24-oic acid |

| 31 | CDCA-4β-ol | 3α,4β,7α-Trihydroxy-5β-cholan 24-oic acid |

| 32 | DCA-1β-ol | 1β,3α,12α-Trihydroxy-5β-cholan 24-oic acid |

| Keto-bile acids | ||

| 33 | 7-KetoDCA | 3α,12α-Dihydroxy-7-oxo-5β-cholan-24-oic acid |

| 34 | 7-KetoLCA | 3α-Hydroxy-7-oxo-5β-cholan-24-oic acid |

| 35 | LCA-3-one | 3-Oxo-5β-cholan-24-oic acid |

| Short or long side chain bile acids | ||

| 36 | norDCA | 3β-Hydroxy-5β-cholan-23-oic acid |

| 37 | THChA | 3α,7α,12α-Trihydroxy-5β-cholestan-27-oic acid |

| 38 | DHChA | 3α,7α-Dihydroxy-5β-cholestan-27-oic acid |

| N-acylamidated bile acids | ||

| 39 | GCA | Glycocholic acid |

| 40 | GCDCA | Glycochenodeoxycholic acid |

| 41 | GUDCA | Glycoursodeoxycholic acid |

| 42 | GDCA | Glycodeoxycholic acid |

| 43 | GLCA | Glycolithocholic acid |

| 44 | TCA | Taurocholic acid |

| 45 | TCDCA | Taurochenodeoxycholic acid |

| 46 | TUDCA | Tauroursodeoxycholic acid |

| 47 | TDCA | Taurodeoxycholic acid |

| 48 | TLCA | Taurolithocholic acid |

| Sulfated bile acids | ||

| 49 | CA3S | Cholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 50 | CDCA3S | Chenodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 51 | UDCA3S | Ursodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 52 | DCA3S | Deoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 53 | LCA3S | Lithocholic acid 3-sulfate |

| Double conjugated bile acids | ||

| 54 | GCA3S | Glycocholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 55 | GCDCA3S | Glycochenodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 56 | GUDCA3S | Glycoursodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 57 | GDCA3S | Glycodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 58 | GLCA3S | Glycolithocholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 59 | TCA3S | Taurocholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 60 | TCDCA3S | Taurochenodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 61 | TUDCA3S | Tauroursodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 62 | TDCA3S | Taurodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate |

| 63 | TLCA3S | Taurolithocholic acid 3-sulfate |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ms. Dalila Marques and Ms. Patricia Cooper for their able technical assistance. The authors are grateful to Dr. Takashi Iida for his kind gift of bile acid standards.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- CA

- cholic acid

- CDCA

- chenodeoxycholic acid

- DCA

- deoxycholic acid

- GCA

- glycocholic acid

- GCDCA

- glycochenodeoxycholic acid

- GDCA

- glycodeoxycholic acid

- GLCA

- glycolithocholic acid

- GUDCA

- glycoursodeoxycholic acid

- HCA

- hyocholic acid

- IS

- internal standard

- LCA

- lithocholic acid

- TCA

- taurocholic acid

- TCDCA

- taurochenodeoxycholic acid

- TDCA

- taurodeoxycholic acid

- TEA

- triethylamine

- TLCA

- taurolithocholic acid

- TUDCA

- tauroursodeoxycholic acid

- UDCA

- ursodeoxycholic acid

This work was partly supported by grant U01AT004428 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, grant RO1AA020203 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, grant RO1DK087913 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and Veterans Affairs Merit Review funding.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of four figures and one table.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hofmann A. F., Hagey L. R. 2008. Bile acids: chemistry, pathochemistry, biology, pathobiology, and therapeutics. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65: 2461–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths W. J., Sjövall J. 2010. Bile acids: analysis in biological fluids and tissues. J. Lipid Res. 51: 23–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hylemon P. B., Zhou H., Pandak W. M., Ren S., Gil G., Dent P. 2009. Bile acids as regulatory molecules. J. Lipid Res. 50: 1509–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer R. H. 1971. Bile acid sulfates. II. Formation, metabolism, and excretion of lithocholic acid sulfates in the rat. J. Lipid Res. 12: 680–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trauner M., Claudel T., Fickert P., Moustafa T., Wagner M. 2010. Bile acids as regulators of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism. Dig. Dis. 28: 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj J. S., Hylemon P. B., Ridlon J. M., Heuman D. M., Daita K., White M. B., Monteith P., Noble N. A., Sikaroodi M., Gillevet P. M. 2012. Colonic mucosal microbiome differs from stool microbiome in cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy and is linked to cognition and inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 303: G675–G685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kakiyama G., Pandak W. M., Gillevet P. M., Hylemon P. B., Heuman D. M., Daita K., Takei H., Muto A., Nittono H., Ridlon J. M., et al. 2013. Modulation of the fecal bile acid profile by gut microbiota in cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 58: 949–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roda A., Francesco P., Mario B. 1998. Separation techniques for bile salts analysis. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 717: 263–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roda A., Cerrè C., Simoni P., Polimeni C., Vaccari C., Pistillo A. 1992. Determination of free and amidated bile acids by high-performance liquid chromatography with evaporative light-scattering mass detection. J. Lipid Res. 33: 1393–1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann A. F., Sjövall J., Kurz G., Radominska A., Schteingart C. D., Tint G. S., Vlahcevic Z. R., Setchell K. D. R. 1992. A proposed nomenclature for bile acids. J. Lipid Res. 33: 599–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iida T., Momose T., Nambara T., Chang F. C. 1986. Potential bile acid metabolism X. Syntheses of stereoisomeric 3,7-dihydroxy-5alpha-cholanic acid. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo). 34: 1929–1933. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iida T., Momose T., Chang F. C., Nambara T. 1986. Potential bile acid metabolism XI. Syntheses of stereoisomeric 7,12-dihydroxy-5alpha-cholanic acids. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo). 34: 1934–1938. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Björkhem I., Danielsson H., Issidorides C., Kallner A. 1965. On the synthesis and metabolism of cholest-4-en-7alpha-ol-3-one. Bile acids and steroids 156. Acta Chem. Scand. 19: 2151–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto J., Kato H., Hasegawa F., Nambara T. 1979. Synthesis of monosulfates of unconjugated and conjugated bile acids. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo). 27: 1402–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki M., Murai T., Yoshimura T., Kimura A., Kurosawa T., Tohma M. 1997. Determination of 3-oxo-delta4- and 3-oxo-delta4,6-bile acids and related compounds in biological fluids of infants with cholestasis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 693: 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stellaard F., Hachey D. L., Klein P. D. 1978. Separation of bile acids as their phenacyl esters by high-pressure liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 87: 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muto A., Takei H., Unno A., Murai T., Kurosawa T., Ogawa S., Iida T., Ikegawa S., Mori J., Ohtake A., et al. 2012. Detection of Δ4-3-oxo-steroid 5β-reductase deficiency by LC–ESI-MS/MS measurement of urinary bile acids. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 900: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goto J., Hasegawa H., Kato H., Nambara T. 1978. A new method for simultaneous determination of bile acids in human bile without hydrolysis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 87: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann A. F., Loening-Baucke V., Lavine J. E., Hagey L. R., Steinbach J. H., Packard C. A., Griffin T. L., Chatfield D. A. 2008. Altered bile acid metabolism in childhood functional constipation: inactivation of secretory bile acids by sulfation in a subset of patients. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 47: 598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korpela J. T., Fotsis T., Adlercreutz H. 1986. Multicomponent analysis of bile acids in faeces by anion exchange and capillary column gas-liquid chromatography: application in oxytetracycline treated subjects. J. Steroid Biochem. 25: 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batta A. K., Salen G., Rapole K. R., Batta M., Batta P., Alberts D., Earnest D. 1999. Highly simplified method for gas-liquid chromatographic quantitation of bile acids and sterols in human stool. J. Lipid Res. 40: 1148–1154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setchell K. D. R., Lawson A. M., Tanida N., Sjövall J. 1983. General methods for the analysis of metabolic profiles of bile acids and related compounds in feces. J. Lipid Res. 24: 1085–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humbert L., Maubert M. A., Wolf C., Duboc H., Mahé M., Farabos D., Seksik P., Mallet J. M., Trugnan G., Masliah J., et al. 2012. Bile acid profiling in human biological samples: comparison of extraction procedures and application to normal and cholestatic patients. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 899: 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelsey M. I., Sexton S. A. 1976. The biosynthesis of ethyl esters of lithocholic acid and isolithocholic acid by rat intestinal microflora. J. Steroid Biochem. 7: 641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelsey M. I., Molina J. E., Huang S-K. S., Hwang K-K. 1980. The identification of microbial metabolites of sulfolithocholic acid. J. Lipid Res. 21: 751–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benson G. M., Haskins N. J., Eckers C., Moore P. J., Reid D. G., Mitchell R. C., Waghmare S., Suckling K. E. 1993. Polydeoxycholate in human and hamster feces: a major product of cholate metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 34: 2121–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman A. 1964. Faecal excretion products of cholic acid in man. Br. J. Nutr. 18: 173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vlahcevic Z. R., Buhac I., Bell C. C., Jr, Swell L. 1970. Abnormal metabolism of secondary bile acids in patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 11: 420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okuyama S., Kokubun N., Higashidate S., Uemura D., Hirata Y. 1979. A new analytical method of individual bile acids using high-performance liquid chromatography and immobilized 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in column form. Chem. Lett. 8: 1443–1446. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porter J. L., Fordtran J. S., Ana C. A. S., Emmett M., Hagey L. R., Macdonald E. A., Hofmann A. F. 2003. Accurate enzymatic measurement of fecal bile acids in patients with malabsorption. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 141: 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller S., Jahreis G. 2004. Determination of underivatised sterols and bile acid trimethyl silyl ether methyl esters by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry-single ion monitoring in faeces. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 813: 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grundy S. M., Ahrens E. H., Jr, Mietinnen T. A. 1965. Quantitative isolation and gas-liquid chromatographic analysis of total faecal bile acids. J. Lipid Res. 6: 397–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.