1. Introduction

Redox reactions play important roles in almost all biological processes, including photosynthesis and respiration, which are two essential energy processes that sustain all life on earth. It is thus not surprising that biology employs redox-active metal ions in these processes. It is largely the redox activity that makes metal ions uniquely qualified as biological cofactors and makes bioinorganic enzymology both fun to explore and challenging to study.

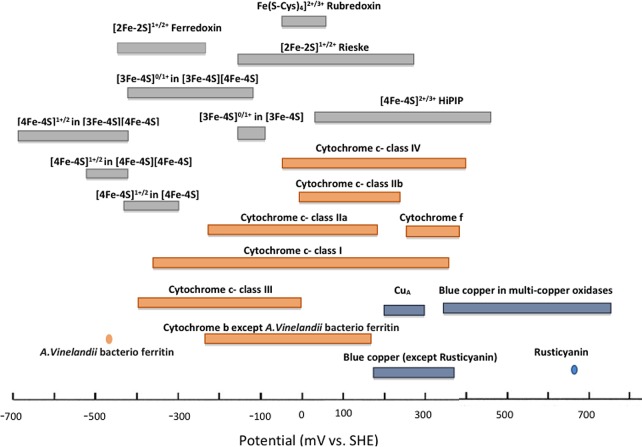

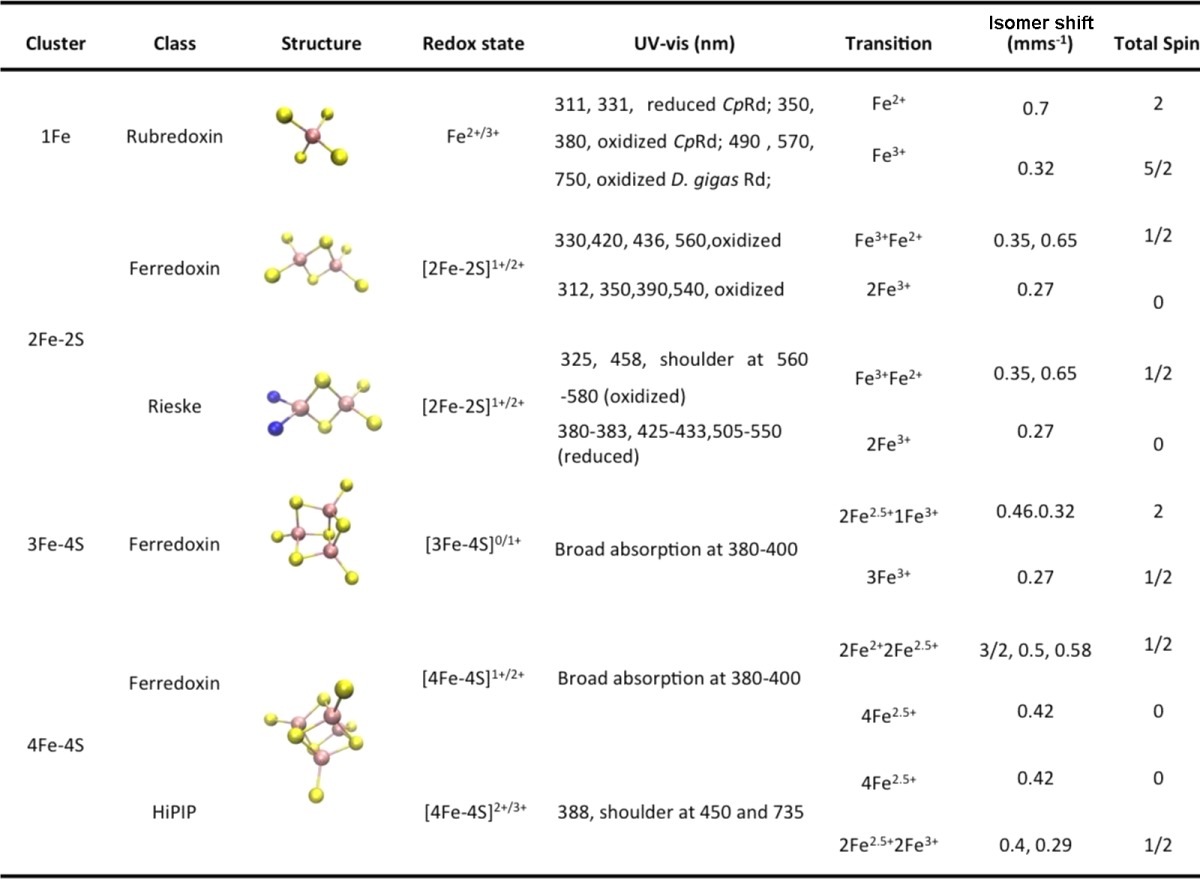

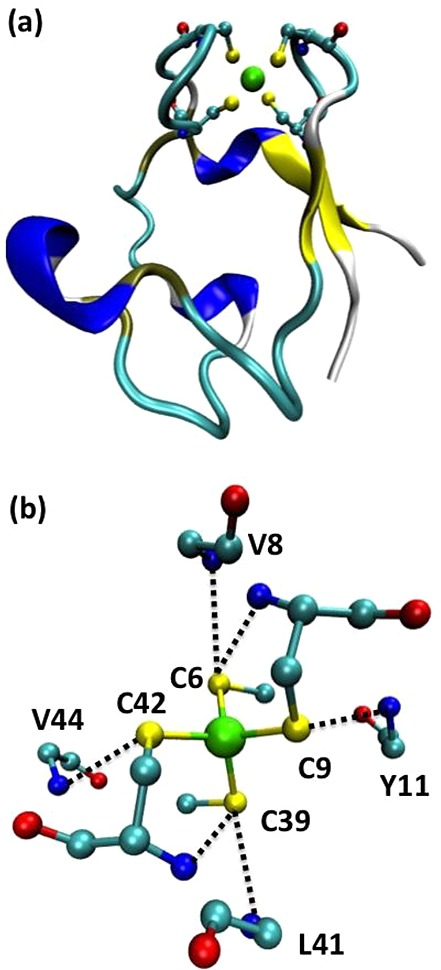

Even though most metal ions are redox active, biology employs a surprisingly limited number of them for electron transfer (ET) processes. Prominent members of redox centers involved in ET processes include cytochromes, iron–sulfur clusters, and cupredoxins. Together these centers cover the whole range of reduction potentials in biology (Figure 1). Because of their importance, general reviews about redox centers1−77 and specific reviews about cytochromes,8,24,78−90 iron–sulfur proteins,91−93 and cupredoxins94−104 have appeared in the literature. In this review, we provide both classification and description of each member of the above redox centers, including both native and designed proteins, as well as those proteins that contain a combination of these redox centers. Through this review, we examine structural features responsible for their redox properties, including knowledge gained from recent progress in fine-tuning the redox centers. Computational studies such as DFT calculations become more and more important in understanding the structure–function relationship and facilitating the fine-tuning of the ET properties and reduction potentials of metallocofactors in proteins. Since this aspect has been reviewed extensively before,105−110 and by other reviews in this thematic issue,2000,2001,2002 it will not be covered here.

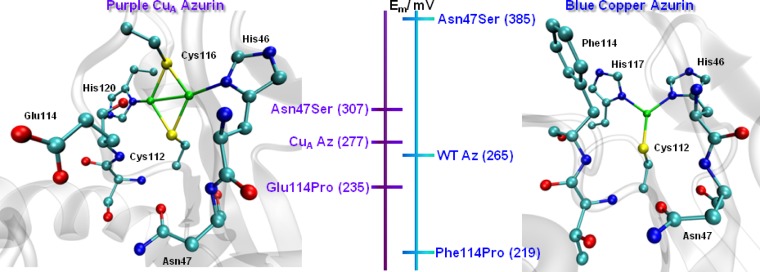

Figure 1.

Reduction potential range of redox centers in electron transfer processes.

2. Cytochromes in Electron Transfer Processes

2.1. Introduction to Cytochromes

Cytochromes are a major class of heme-containing ET proteins found ubiquitously in biology. They were first described in 1884 as respiratory pigments (called myohematin or histohematin) to explain colored substances in cells.81,111 These colored substances were later rediscovered in 1920 and named “cytochromes”, or cellular pigments.112 The intense red color combined with relatively high thermodynamic stability makes cytochromes easy to observe and to purify. As of today, more than 70 000 cytochromes have been discovered.78 In addition, due to their small size, high solubility, and well-folded helical structure and the presence of the heme chromophore, cytochromes are one of the most extensively studied classes of proteins spanning several decades.79

Cytochromes are present mostly in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotic organisms and are also found in a wide variety of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.113,114 Cytochromes play crucial roles in a number of biological ET processes associated with many different energy metabolisms. Additionally, cytochromes are involved in apoptosis in mammalian cells.115 Further description of the latter role of cytochromes is beyond the scope of this review, which is solely focused on the role of cytochromes in ET. For a similar reason, another family of cytochromes, the cyts P450 (CYP), which catalyze the oxidation of various organic substrates such as metabolites (lipids, hormones, etc.) and xenobiotic substances (drugs, toxic chemicals, etc.), will not be discussed in this review either.

A number of books and reviews have appeared in the literature describing the role of cytochromes as ET proteins.8,24,78−90 Here we summarize studies on both native and designed cytochromes and their roles in biological ET processes.

2.2. Classification of Cytochromes

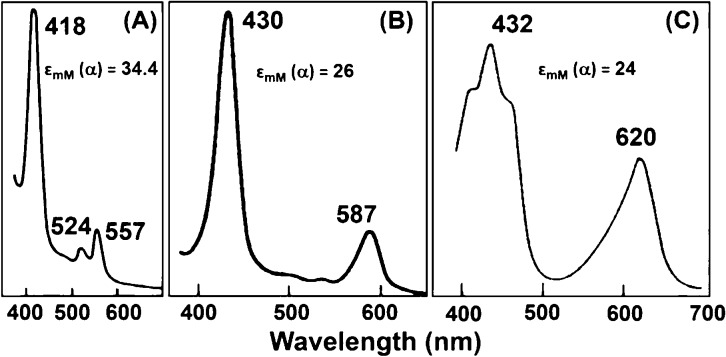

Cytochromes are classified on the basis of the electronic absorption maxima of the heme macrocycle, such as a, b, c, d, f, and o types of heme. More specifically, these letter names represent characteristic absorbance maxima in the UV–vis electronic absorption spectrum when the heme iron is coordinated with pyridine in its reduced (ferrous) state, designated as the “pyridine hemochrome” spectrum (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Representative pyridine hemochromogen spectra of hemin cofactors: (A) heme b, (B) heme a, and (C) heme d1. The spectrum of pyridine ferrohemochrome c is similar to that of heme b. Reprinted with permission from ref (116). Copyright 1992 Springer-Verlag.

Table 1 shows the maximum peak positions and their corresponding extinction coefficients of the pyridine hemochrome spectra of various classes of cytochromes. These differences arise from different substituents at the β-pyrrole positions on the periphery of the heme.

Table 1. UV–Vis Spectral Parameters of Pyridine Hemochrome Spectra of Various Types of Cytochromesa.

| pyridine hemochromogen |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| heme | position of α peak (nm) | εmM (at α peak) | α peak (nm) of reduced protein | example | ref |

| protoheme IX (b) | 557 | 34.4 | 557–563 | cyt b6f complex | (117) |

| heme c | 550 | 29.1 | 549–561 | cyt c | (118) |

| heme a | 587 | 26 | 587–611 | cyt aa3 oxidase | (117) |

| heme d | 613 | 630–635 | cyt bd oxidase | (116) | |

| heme d1 | 620 | 24 | 625 | cyt cd1 nitrite reductase | (116) |

| heme o | 553 | 560 | cyt bo3 oxidase | (119) | |

Adapted with permission from ref (116). Copyright 1992 Springer-Verlag.

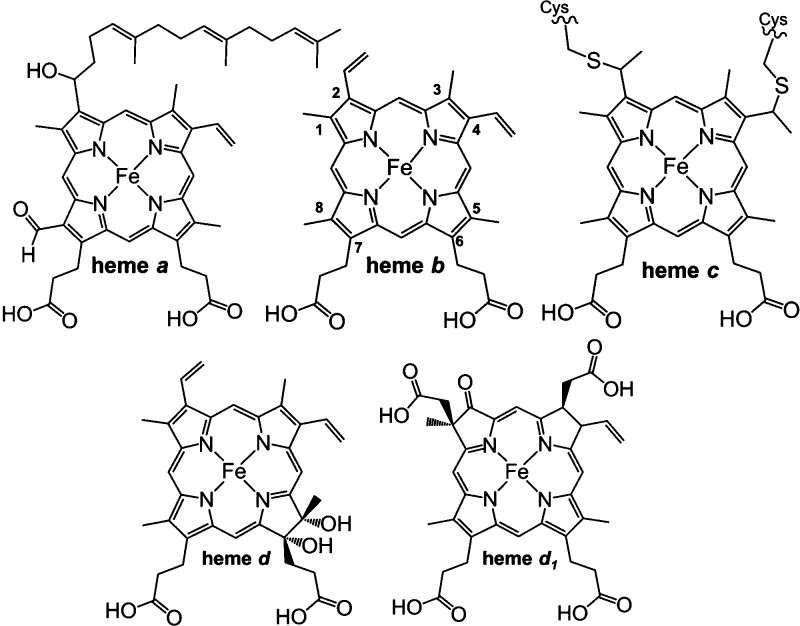

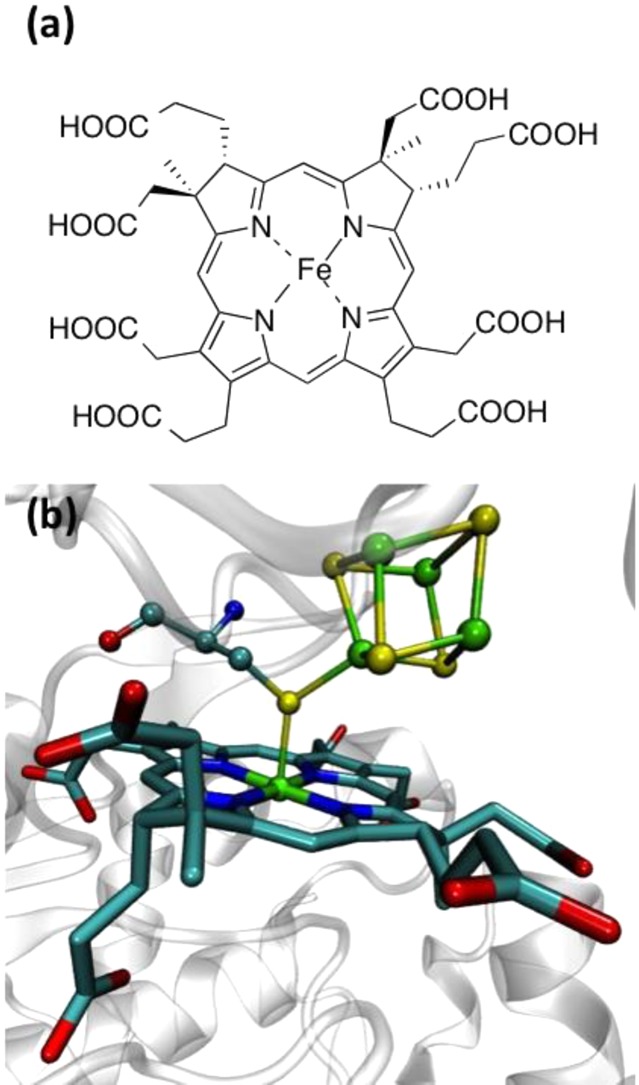

The word “heme” specifically describes the ferrous complex of the tetrapyrrole macrocyclic ligand called protoporphyrin IX (Figure 3).81 It is the precursor to various types of cytochromes through different peripheral substitutions. Figure 3 shows a schematic of these various types of hemes.

Figure 3.

Different types of heme found in cytochromes.

The b-type cytochromes have four methyl substitutions at positions 1, 3, 5, and 8, two vinyl groups in positions 2 and 4, and two propionate groups at positions 6 and 7, resulting in a 22-π-electron porphyrin. Hemes a and c are biosynthesized as derivatives of heme b. In heme a, the vinyl group at position 2 of the porphyrin ring of heme b is replaced by a hydroxyethylfarnesyl side chain while the methyl group at position 8 is oxidized to a formyl group. These substituents make heme a more hydrophobic as well as more electron-withdrawing than heme b due to the presence of farnesyl and formyl groups, respectively. Covalent cross-linking of the vinyl groups at β-pyrrole positions 2 and 4 of heme b with Cys residues from the protein yields heme c, where the vinyl groups of heme b are replaced by thioether bonds.

The covalent cross-linking of the two Cys residues from the protein to the porphyrin ring occurs at the highly conserved -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- sequences (Xxx=any amino acid). This cross-linking covalently attaches heme c to the protein. The histidine residue in the conserved sequence serves as an axial ligand to the heme iron. In heme d, two cis-hydroxyl groups are inserted at positions 5 and 6 on the β-pyrrole, which renders heme d as a 20-π-electron chlorin. Heme d1 contains two ketone groups in place of the vinyl groups at positions 2 and 4, while two acetate groups are added to positions 1 and 3 of the tetrapyrrole macrocycle, resulting in 18-π-electron isobacteriochlorins. The hemes f is similar to heme c, with the difference in the ligands that coordinate to the heme iron at the axial position (called axial ligands) make hemes c and f spectroscopically distinct.

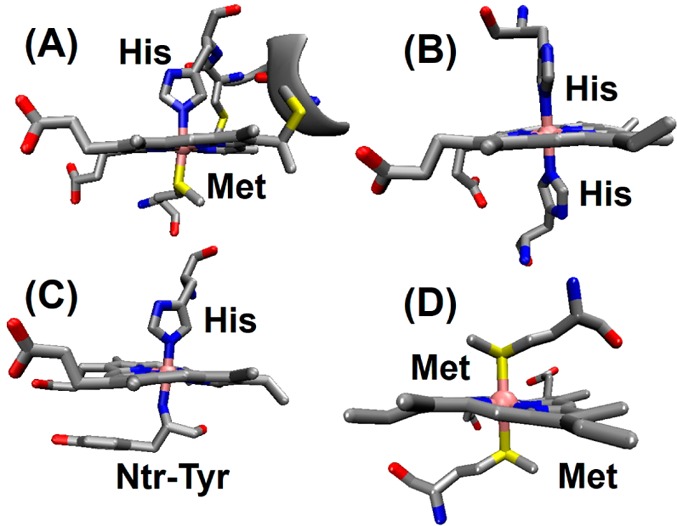

Common axial ligands found in cytochromes are shown in Figure 4. With the exception of cytochromes c′ (cyts c′), all cytochromes with ET function contain 6-coordinate low-spin (6cLS) hemes axially ligated to amino acids such as His or an N-terminal amine group. Two axial His residues act as ligands to the heme iron in b-type cytochromes. The only example of bis-Met axial coordination to heme b is observed in the iron storage protein bacterioferritin.120,121 A common axial His ligand is found in all cyts c, where the axial His is a part of the conserved -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- sequence, through which the heme is covalently attached to the protein. The most commonly encountered second axial ligand in c-type cytochromes is Met with the exception of multiheme c-type cytochromes, which generally display bis-His axial ligation of the heme iron (section 2.3.6).80 In most cases, the His ligands are coordinated to the heme iron by their Nε atom. However, an example of Nδ coordination has been reported.122 The f-type cytochromes contain the same type of heme with one axial His ligand, as in cyts c; the only exception is in the nature of the second axial ligation in that the second axial ligand is the NH2 group of an N-terminal tyrosine instead of the most commonly found Met or His as the second axial ligand.123 Not surprisingly, the variation in the axial ligation makes each heme type electronically unique, resulting in different out-of-plane distortions of the heme iron from the heme plane (Figure 4) as well as different spectroscopic features (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Commonly found heme axial ligands in various cytochromes. (A) Class I cyts c (PDB ID 3CYT) uses His/Met axial ligation. (B) Cyts b and multiheme cyts c contain bis-His ligation (bovine liver cyt b5, PDB ID 1CYO). (C) An unusual His/amine ligation is found only in cyt f (PDB ID 1HCZ). (D) Bis-Met ligation is encountered in bacterioferritin (PDB ID 1BCF). For c-type cytochromes the conserved -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- ligation and its covalent linkage to the heme via Cys residues are shown.

2.3. Native Cytochromes c

2.3.1. Functions of Cytochromes c

Cytochromes c are involved in biological ET processes in both aerobic and anaerobic respiratory chains. In aerobic respiration, they are involved in the mitochondrial respiratory chain to produce the energy currency ATP by transferring electrons from the transmembrane bc1 complex to cyt c oxidase.85,86 In addition, cyts c have also been recently discovered to play a crucial role in programmed cell death (apoptosis), where they activate the protease involved in cell death, caspase 3.124−126 Other examples where c-type cytochromes are involved in ET include the reduction of sulfate to hydrogen sulfide, conversion of nitrogen to ammonia in nitrogen fixation, reduction of nitrate to dinitrogen in denitrification, in phototrophs that use light energy to carry out various cellular processes, and in methylotrophs that use methane or methanol as the carbon source for their growth. Detailed descriptions of the roles of cyts c in these cases will be discussed in the following sections.

As cyts c are involved in numerous crucial biological processes, they have been used extensively as a hallmark system to study biological ET by site-directed mutagenesis, which have elucidated the regions of the protein that are critical for their ET properties as well as fine-tuning the reduction potentials.87,127−131 In addition, various inorganic redox couples have been covalently appended to surface sites of cyts c to study intraprotein ET pathways.24,132,133 Various complexes of cyts c with other protein partners have also been prepared to study interprotein ET pathways.134−149

2.3.2. Classifications of Cytochromes c

Cytochromes c generally contain ∼100–120 amino acids. Biosynthesis of cyts c involves the formation of two thioether bonds between two Cys residues and the two vinyl groups of heme b by post-translational modification.150,151 Primary amino acid sequence alignment shows that the residue identity of cyts c is 45–100% among eukaryotes. The electronic spectra of cyts c are dominated by the allowed porphyrin π → π* transitions that are mixed together with interelectronic repulsions that give rise to an intense band at ∼410 nm (called the Soret or γ band) and two weaker signals in the 500–600 nm range (the α and β bands). The reduced form of the protein shows a Soret band at 413 nm and sharp α and β bands at 550 nm (ε = 29.1 mM–1 cm–1) and 521 nm (ε = 15.5 mM–1 cm–1), respectively, with a ratio of α to β bands of 1.87 (Table 1). The electronic spectra of cyts c from other sources are very similar to that of horse heart cyt c. Originally classified by Ambler,89,152 cyts c have been divided into four major classes on the basis of the number of hemes, position and identity of the axial iron ligands, and reduction potentials (Table 2).

Table 2. Axial Ligand Types and Reduction Potentials of Various Cytochromesa.

| cytochrome | axial ligand | heme type | E (mV)b | mutant | E (mV) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrosomonas europaea diheme cyt c peroxidase | His/Met | class I | 450 | (153, 154) | ||

| Rhodocyclus tenuis THRC cyt c | class IV | 420 | (155) | |||

| HP1 | His/Met | 420 | ||||

| HP2 | His/Met | 110 | ||||

| LP1 | bis-His | 60 | ||||

| LP2 | His/Met | |||||

| Rhodopseudomonas viridis THRC cyt c | class IV | 380 | (156,157) | |||

| H1 (c559) | His/Met | 330 | ||||

| H3 (c556) | His/Met | 20 | ||||

| H2 (c552) | bis-His | –60 | ||||

| H4 (c554) | His/Met | |||||

| Rhodobacter capsulatas cyt c2 | His/Met | class I | 373 | Gly29Ser | 330 | (158−160) |

| Pro30Ala | 258 | |||||

| Tyr67Cys | 348 | |||||

| Tyr67Phe | 308 | |||||

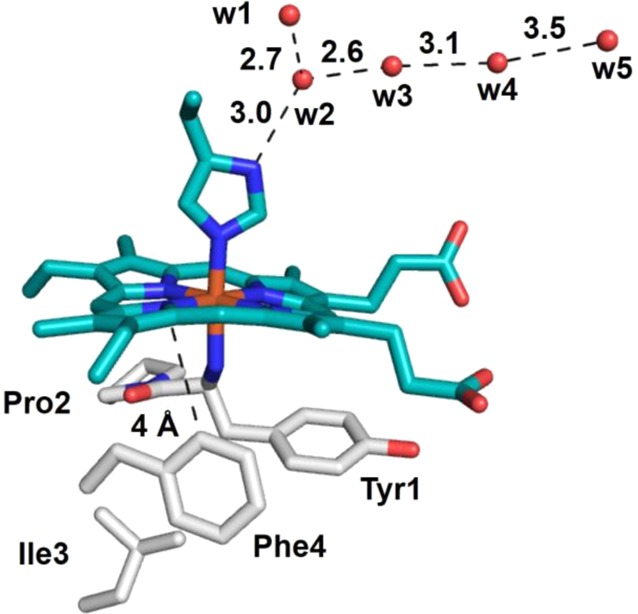

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cyt f | His/Ntr-Tyr | cyt f | 370 | Tyr1Phe | 369 | (161) |

| Tyr1Ser | 313 | |||||

| Val3Phe | 373 | |||||

| Phe4Leu | 348 | |||||

| Phe4Trp | 336 | |||||

| Tyr1Phe/Phe4Tyr | 370 | |||||

| Tyr1Ser/Phe4Leu | 289 | |||||

| Val3Phe/Phe4Trp | 342 | |||||

| Rhodospirillum rubrum cyt c2 | His/Met | class I | 324 | (156) | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa cyt c nitric oxide reductase | His/Met | class I | 310 | (162) | ||

| bis-His | cyt b | 345 | ||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa cyt c peroxidase | His/Met | class I | 320 | (163) | ||

| Arthrospira maxima cyt c6 | His/Met | class I | 314 | (164) | ||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae iso-2-cyt c | His/Met | class I | 288 | Asn52Ile | 243 | (130) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae iso-1-cyt c | His/Met | class I | 272 | Arg38Lys | 249 | (131, 165−173) |

| 285 | Arg38His | 245 | ||||

| 290 | Arg38Gln | 242 | ||||

| Arg38Asn | 238 | |||||

| Arg38Leu | 231 | |||||

| Arg38Ala | 225 | |||||

| Asn52Ala | 257 | |||||

| Asn52Ile | 231 | |||||

| Tyr67Phe | 234 | |||||

| Phe82Leu | 286 | |||||

| Phe82Tyr | 280 | |||||

| Phe82Ile | 273 | |||||

| Phe82Trp | 266 | |||||

| Phe82Ala | 260 | |||||

| Phe82Ser | 255 | |||||

| Phe82Gly | 247 | |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa cyt c551 | His/Met | class I | 276 | (156) | ||

| horse cyt c | His/Met | class I | 262 | Met80Ala | 82 | (158, 174) |

| Met80His | 41 | |||||

| Met80Leu | –42 | |||||

| Met80Cys | –390 | |||||

| rat cyt c | His/Met | class I | 260 | Pro30Ala | 258 | |

| Pro30Val | 261 | |||||

| Tyr67Phe | 224 | |||||

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris cyt c556 | His/Met | class II | 230 | (80) | ||

| Escherichia coli cyt b562 | His/Met | cyt b (class II) | 168 | Phe61Gly | 90 | (175, 176) |

| Phe65Val | 173 | |||||

| Phe61Ile/Phe65Tyr | 68 | |||||

| His102Met | 240 | |||||

| Arg98Cys/His102Met | 440 | |||||

| Alicycliphilus denitrificans cyt c′ | His/Met | class II | 132 | (80) | ||

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris cyt c′ | His/Met | class II | 102 | (80) | ||

| cytochrome b5 | bis-His | cyt b | form A | 80 | (177) | |

| form B | –26 | |||||

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris cyt c553 | His/Met | class I | 37 | Met23Cys | 29 | (156, 178) |

| 20 ± 5 | Gly51Cys | 28 | ||||

| Met23Cys/Met23Cys | 88 | |||||

| Gly51Cys/Gly51Cys | 105 | |||||

| bovine liver microsomal cyt b5 | bis-His | cyt b | 3 | protoheme IX dimethyl ester | 70 | (179) |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyt b2 | bis-His | cyt b | –3 | (156) | ||

| Chromatium vinosum cyt c′ | His | class II | –5 | (80) | ||

| rat liver microsomal cyt b5 | bis-His | cyt b | –7 ± 1 | (129, 180) | ||

| Rhodospirillum rubrum cyt c′ | His/Met | class I | –8 | (80) | ||

| tryptic bovine hepatic cyt b5 | His/Met | class I | –10 ± 3 | Val61Lys | 17 | (181) |

| Val61His | 11 | |||||

| Val61Glu | –25 | |||||

| Val61Tyr | –33 | |||||

| Allochromatium vinosum triheme cyt c | bis-His | class III | –20 | (182) | ||

| His/Met | –200 | |||||

| His-Cys/Met | –220 | |||||

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides cyt c′ | His/Asn | cyt c | –22 | (183) | ||

| cyt b6f complex | bis-His | cyt b | –45 | (184) | ||

| –150 | ||||||

| Thermosynechococcus elongates PS cyt c550 | His/Met | class I | –80 | in the absence of mediators | 200 | (185) |

| MamP magnetochrome | His/Met | class I | –76 | (186) | ||

| rat liver OM cyt b5 | bis-His | cyt b | –102 | His63Met | 110 | (187, 188) |

| Val45Leu/Val61Leu | –148 | |||||

| protoheme IX dimethyl ester | –36 | |||||

| Desulfovibrio desulfuricans Norway cyt c3 | bis-His | class III | –132 | (78) | ||

| bis-His | –255 | |||||

| bis-His | –320 | |||||

| bis-His | –360 | |||||

| Chlorella nitrate reductase cyt b557 | bis-His | cyt b | –164 | (189, 190) | ||

| Ectothiorhodospira shaposhnikovii cyt b558 | bis-His | cyt b | –210 | (191) | ||

| Azotobacter vinelandii bacterioferritin | bis-His | cyt b | –225 | (192) | ||

| (in the presence of a nonheme iron core) | –475 | |||||

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough cyt c3 | bis-His | class III | –280 | (192, 193) | ||

| bis-His | –320 | |||||

| bis-His | –350 | |||||

| bis-His | –380 | |||||

| Synechocystis sp. cyt c549 | bis-His | –250 | (78) | |||

| Arthrospira maxima cyt c549 | His/Met | –260 | (164) |

Adapted with permission from ref (78). Copyright 2004 Elsevier.

All reduction potentials listed in this review are versus standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) or normal hydrogen electrode (NHE).

The class I cyts c include small (8–120 kDa) soluble proteins containing a single 6cLS heme moiety and display a range of reduction potentials from −390 to +450 mV versus standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) (Table 2).78 On the basis of sequence and structural alignments, class I cyts c have further been partitioned into 16 different subclasses.88 The majority of the subclasses include mitochondrial cyts c and purple bacterial cyts c. Examples of other subclasses represent a wide variety of different sources, including cyts c551, cyts c4, cyts c5, and cyts c6 from Pseudomonas, Chlorobium cyt c555, Desulfovibrio (Dv.) cyts c553, c550 from cyanobacteria and algae, Ectothiorhodospira cyts c551, flavocytochromes c, methanol dehydrogenase-associated cyt c550 or cL, cyt cd1 nitrite reductase, the cyt subunit associated with alcohol dehydrogenase, nitrite reductase-associated cyt c from Pseudomonas, and cyt c oxidase subunit II from Bacillus.78

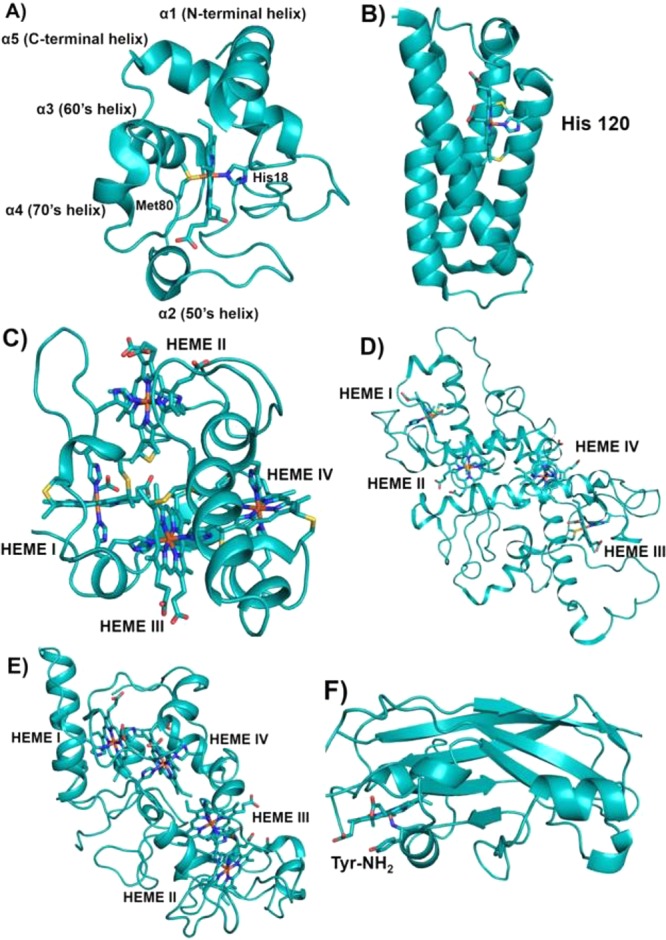

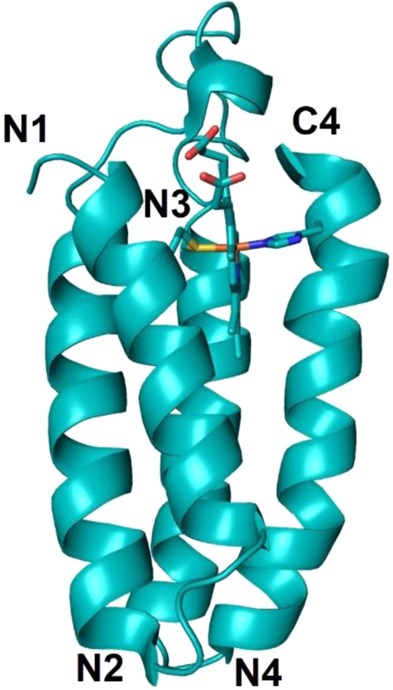

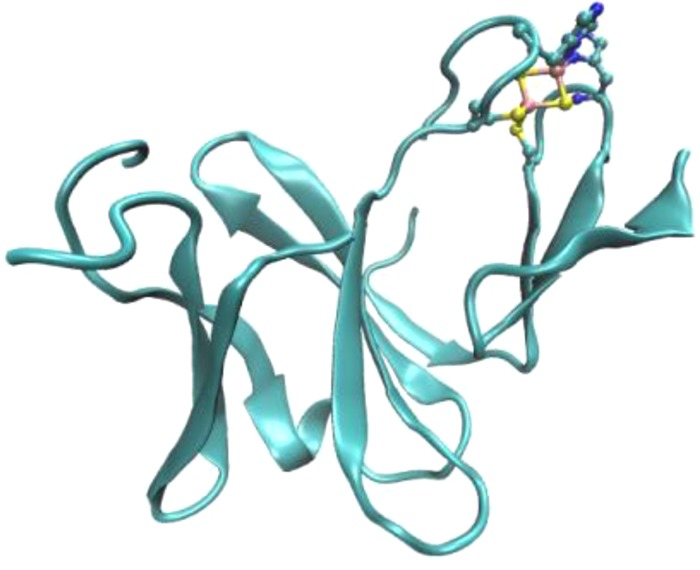

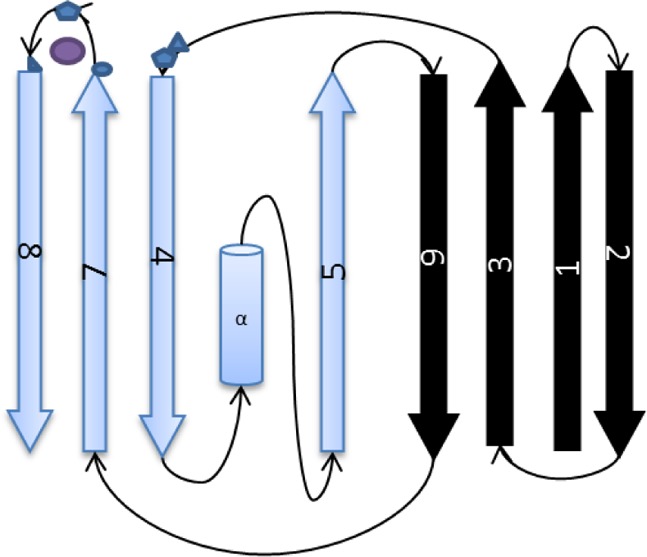

Class I cyt c domains are characterized by their signature cyt c fold and the presence of an N-terminal conserved -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- sequence containing cysteines for covalent cross-linking of the heme to the protein and the His, which acts as the axial ligand to the heme iron. The class I cyt c fold is recognized as having a total of five α-helices arranged in a unique tertiary structure. There are two helices, one each at the N- and C-termini, represented as α1 and α5, respectively. In between, there is a small helix, α3 (also called the 50s helix in mitochondrial cyts c), followed by two other helices, α4 and α5, which are known as the 60s helix and 70s helix, respectively, in mitochondrial cyts c. The 70s helix precedes a loop toward the C-terminus that contains the second axial ligand, Met, to the heme iron. There are examples where the second axial ligand is a residue other than Met, e.g., Asn or His, or is even absent.79 In many cases, this core cyt c domain can be found fused to other membrane proteins. General features of the class I cyt c fold are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic representations of various classes of cyts c. (A) Class I cyt c fold with His/Met heme axial ligands (PDB ID 3CYT). Mitochondrial designation of the helices is also shown. (B) Four-helix bundle cyt c′ belongs to class II cyt c having a 5c heme with His120 as the sole axial ligand (PDB ID 1E83). (C) Tetraheme cyt c3 belongs to class III cyt c with bis-His ligation to all four hemes (PDB ID 1UP9). Hemes I and III are attached to the protein via the highly conserved -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- sequence, whereas hemes II and IV are covalently bound to the protein by a -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- motif. In (A)–(C) the covalent attachment of the heme to the protein via Cys residues is shown. (D) Tetraheme cyt c from the photosynthetic reaction center (RC) belongs to class IV cyt c. Hemes I, II, and III have His/Met axial ligands, while heme IV has bis-His axial ligation to the heme iron (PDB ID 2JBL). (E) Cyt c554 from Nitrosomonas europaea belongs to a class of its own. Hemes I, III, and IV have bis-His-ligated heme iron, whereas heme II is 5c with His as the only axial ligand (PDB ID 1BVB). Heme numbering in (C)–(E) is according to their attachment occurring along the protein’s primary sequence. (F) Cyt f from chloroplast is unique from all other classes of cytochromes in that it mostly contains β-sheets and the heme is 6c with a His and N-terminal backbone NH2 group of a Tyr residue (PDB ID 1HCZ). It has been included as a subclass of cyt c because the heme is covalently bound to the protein via the highly conserved -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- signature motif for heme attachment ubiquitously found in c-type cytochromes.

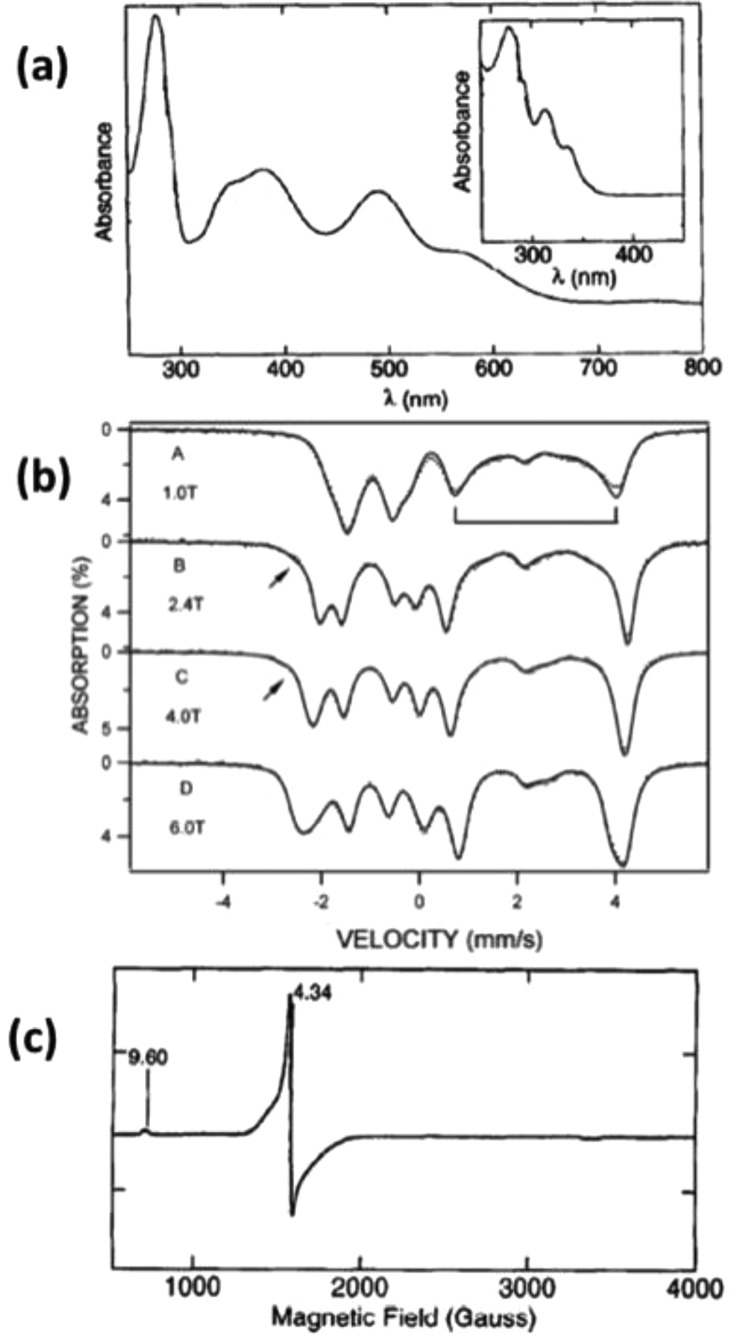

The class II cyts c consist of a c-type heme covalently attached to the highly conserved C-terminal -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- sequence, as in class I cyts c, with the Cys residues and the His as one of the axial ligands.80 Four α-helices and a left-handed twisted overall structure represent this subclass of cyts c (Figure 5). The second axial ligand to the heme iron is variable.194,195 The subclass cyt c′ is axially coordinated to a single His imidazole ligand, lacks the second axial ligand, and has a relatively small range of reduction potentials ranging from approximately −200 to +200 mV.8,84,90 Members from this subclass represent a wide range of sources that include photosynthetic, denitrifying, nitrogen-fixing, methanotrophic, and sulfur oxidizing bacteria. This class has two subclasses based on the distinct spin states displayed by the heme. Subclass IIa of cyt c′ displays high-spin (HS) ferrous [Fe(II), S = 2] electronic configurations, while the ferric form shows either a HS S = 5/2 state or S = 3/2, S = 5/2 mixture of spin states.196−202 The subclass IIa proteins, isolated from Rhodopseudomonas palustris, Rhodobacter (Rb.) capsulatus, and Chromatium (Ch.) vinosum, display a large amount of the S = 3/2 ground state in the spin-state admixture, ranging from 40% to 57% as determined from electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) simulations.196,201,203 The second subclass, IIb, includes cyt c556 from Rp. palustris,204Rb. sulfidophilus,205 and Agrobacterium tumefaciens(80) and cyt c554 from Rb. sphaeroides,206 which contain heme in the low-spin (LS) configuration. This subclass of proteins has a second axial ligand to the heme iron which is a Met residue located close to the N-terminus. Class II cyts display reduction potentials ranging from −5 to +230 mV (Table 2).

Class III cyts c include proteins containing multiple hemes with bis-His ligation and display reduction potentials in the range of −20 to −380 mV (Table 2).80,88,152,207−212 In some cases this class of cytochromes have up to 16 heme cofactors and display no structural similarity with other classes of cyts c. They are found as terminal electron donors in bacteria involved in sulfur metabolism.213 These bacteria utilize sulfur or oxidized sulfur compounds as terminal electron acceptors in their respiratory chain. One of the best studied proteins in this class is cyt c3 (∼13 kDa) (Figure 5) from Desulfovibrio, which acts as a natural electron acceptor and donor in hydrogenases and ferredoxins.214 The overall protein fold containing two β-sheets and three to five α-helices is conserved among the known structures of cyts c3 as well as the orientation of the four hemes which are located in close proximity to each other, with each of the heme planes being nearly perpendicular to the others.88 Each heme displays a distinct reduction potential spanning a range from −200 to −400 mV.215−219 Cyt c555.1, also known as cyt c7 (∼9 kDa, 70 amino acids), from Desulfuromonas acetoxidans is another class III cyt c that contains three hemes.220 These proteins have been proposed to be involved in ET to elemental sulfur as well as in the coupled oxidation of acetate and dissimilatory reduction of Fe(III) and Mn(IV) as an energy source in these bacteria.221 In cyt c7, two of the hemes have a reduction potential of −177 mV and the third heme has a reduction potential of −102 mV.222

Class IV cyts c fall into the category of large molar mass (∼35–40 kDa) cytochromes that contain other prosthetic groups in addition to c-type hemes such as flavocytochromes c and cyts cd.152 One example of class IV cyts c is revealed by the X-ray structure of the photosynthetic reaction center (RC) from Rhodpseudomonas viridis, where light energy is harvested and converted to chemically useful energy. The cyt c in the RC consists of four c-type heme moieties covalently bound to subunit C of the RC. Three of the hemes have His/Met axial ligation, while the fourth heme is bis-His-ligated. The four hemes are oriented in two types of pairs. The porphyrin planes of hemes I/III and II/IV are orientated parallel to each other, while the porphyrin planes of each pair of hemes are mutually perpendicular to each pair’s porphyrin planes (Figure 5).223

Cyt c554 is another tetraheme cytochrome that is involved in the ET pathway of the biological nitrogen cycle in the oxidation of ammonia in Nitrosomonas europaea.122,224 This family of cytochromes does not fall into either class III or class IV cytochromes and has been proposed to belong to a class of its own. A pair of electrons are passed from hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) to two molecules of cyt c554 upon oxidation of hydroxylamine to nitrite. One of the hemes is HS, and the other three are 6cLS with reduction potentials of +47, +47, −147, and −276 mV, respectively. Porphyrin planes of hemes III and IV are oriented almost perpendicular to each other, while the heme pairs I/III and II/IV have parallel orientation (Figure 5). The sets of parallel hemes overlap at an edge, and such heme orientation has been observed in HAO and cyt c nitrite reductase.

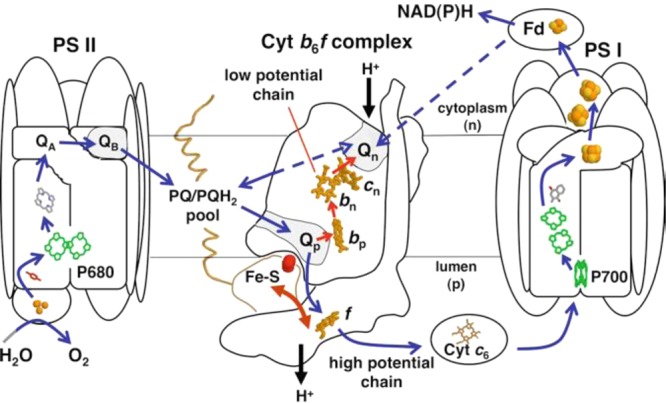

Cyt f is a high-potential (Table 2) electron acceptor of the chloroplast cyt b6f complex involved in oxygenic photosynthesis by passing electrons from photosystem II to photosystem I of the RC.123,225 Cyt f accepts electrons from a Rieske-type iron–sulfur cluster and passes electrons to the copper protein plastocyanin. Cyt f consists of two domains primarily of β-sheets and is anchored to the membrane by a transmembrane segment, while most of the protein is located on the lumen side of the thylakoid membrane. The heme is also located on the lumen side at the interface of the two domains and is covalently attached to the protein via the signature sequence of cyts c, -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His-. The β-sheet fold has not been observed in any other families of cytochromes and is thus unique to cyts f. Intriguingly, this family of cytochromes also contains an unusual second axial ligation to the heme iron, an N-terminal −NH2 group of a Tyr residue (Figure 5).

Quite uniquely, the only exception to the bis-Cys covalent attachment of the c-type hemes via the conserved -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- motif in cyt c is found in eukaryotes from the phylum Euglenozoa, including trypanosome and Leishmania parasites. In the mitochondrial cyt c of these organisms, the heme is attached to the protein via a single Cys residue from the heme binding motif -Ala (Ala/Gly)-Gln-Cys-His-.226−228

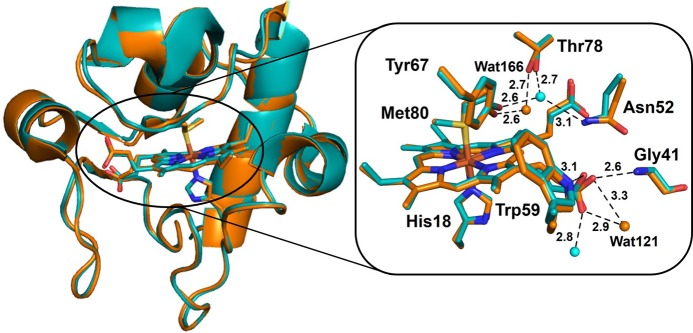

2.3.3. Conformational Changes in Class I Cytochromes c Induced by Changes in the Heme Oxidation State

Many structural studies have been undertaken to determine whether there is any effect on the protein structure associated with different oxidation states of the heme iron. These studies include X-ray and NMR structures of oxidized and reduced cyts c from various sources,229−235 which indicate that the oxidation state of the heme iron has a minimal effect on the tertiary structures of the proteins (Figure 6). The major changes are observed in the conformation of some amino acid residues located close to the heme pocket. Among these residues, Asn52, Tyr67, Thr78, and a conserved water (wat166) molecule show maximal changes in conformations depending on the oxidation state of the heme iron. These conserved residues,236 along with the conserved water molecule, the axial ligand Met80, and heme propionate 7, form a hydrogen-bonding network around the heme site. The high-resolution X-ray structure of yeast iso-1-cytochrome c shows that in the reduced state the heme is significantly distorted from planarity into a saddle shape. The degree of heme distortion in the oxidized state is even more pronounced compared to that of the reduced state, suggesting that the planarity of the heme group is dependent on the oxidation state of the iron. The major change in the bond length of the heme iron ligands is observed in the case of axial Met80, which increases from 2.35 to 2.43 Å in going from the reduced to the oxidized state. On the contrary, the other axial ligand, His18, shows a minute change of 0.02 Å, from 1.99 to 2.01 Å.230

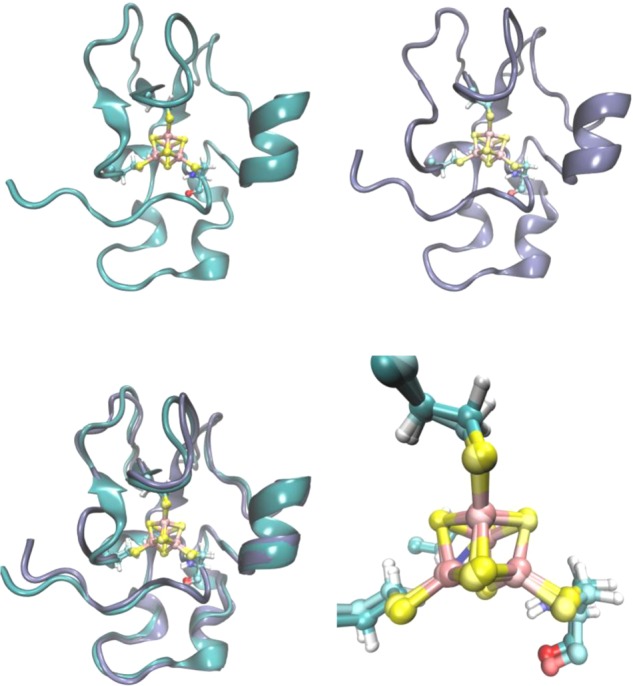

Figure 6.

Overall structural overlay of the reduced (cyan, PDB ID 1YCC) and oxidized (orange, PDB ID 2YCC) iso-1-cyt c (left). A close look at the heme site and the nearby residues is shown on the right along with some hydrogen bond interactions.

In the reduced state of iso-1-cytochrome c, the conserved water molecule is hydrogen bonded to Asn52, Tyr67, and Thr78 (Figure 6). Upon oxidation wat166 undergoes a 1.7 Å displacement toward the heme, which results in the loss of the hydrogen bond to Asn52, but interactions with Tyr67 and Thr78 are retained. Figure 6 shows an overlay of the residues near the heme pocket between the reduced and oxidized states of iso-1-cytochrome c.87

Further analysis suggested that wat166 plays a key role in stabilizing both oxidation states of the heme iron by reorienting the dipole moment, by changing the heme iron–wat166 distance, and by variations in the nearby H-bonding network. Another noticeable change is observed in the H-bonding between a conserved water, wat121, and heme propionate 7. In the reduced state, wat121 and Trp59 are hydrogen-bonded to O1A and the O2A oxygen of propionate 7, respectively. In the oxidized state, interaction between Trp59 and O2A of the heme propionate weakens, while that of O2A and the conserved Gly41 increases. Additionally, wat121 moves by 0.5 Å and causes a bifurcated hydrogen bond between both O1A and O2A of the propionate.230 Thus, it appears that there are three major regions that show significant changes in conformation between the two oxidation states: heme propionate 7, wat166, and Met80. A conserved region that does not show mobility between oxidation states is the region encompassing residues 73–80 in iso-1-cytochrome c, which is linked to the three major regions of conformation change through Thr78. On the basis of this observation, it has been suggested that region 73–80 acts as a contact point with redox partners and triggers the necessary conformational changes in other parts of the protein that are required to stabilize both oxidation states of cyt c.230 A contrasting observation from NMR studies is that wat166 moves 3.7 Å away from the heme iron when going from the reduced to the oxidized state, rather than moving toward the heme iron.237,238

Similar to the changes of heme propionate observed in eukaryotes, cyts c2(160,239−242) and c6(220,243,244) from some prokaryotes also display conformational changes in the heme propionate between the reduced and oxidized states of the protein. In the cases of cyt cH (reduces methanol oxidase in methylotropic bacteria) from Methylobacterium extorquens and cyt c552(245−247) (electron donor to a ba3–cytochrome c oxidase) from T. thermophilus, there is no conserved water molecule in the heme pocket, suggesting that the water-mediated H-bonding network is not a critical requirement for ET.248−250

2.3.4. Cytochromes c as Redox Partners to Other Enzymes

In the following sections we summarize some specific examples of native enzymes that use cyts c as the native electron donor for performing various biochemical processes.

2.3.4.1. Cytochrome c as a Redox Partner to Cytochrome c Peroxidases

Cytochrome c peroxidases (CcPs) are a family of enzymes that catalyze the conversion of H2O2 to water and are found in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Eukaryotic CcPs are located in the inner mitochondrial membrane and contain a single heme cofactor, heme b, while prokaryotic CcPs are located in the periplasmic space and contain two covalently bound c-type hemes,251,252 one of which is a low-potential (lp) heme and the other is a high-potential (hp) heme. In general, the physiological electron donors to bacterial CcPs are monoheme cyts c, although other donors such as azurin (Az) or pseudoazurin have also been found in some bacteria.253 The hp heme is located at the C-terminal domain and has a more positive reduction potential than cyt c as it accepts electrons from cyt c. The reduction potential for the hp heme varies depending on the organism; e.g., the Ps. aeruginosa CcP hp site has a reduction potential of +320 mV,163 the Rb. capsulatus CcP hp site a reduction potential of +270 mV,254 and the N. europaea CcP hp site a reduction potential of +130 mV.154 The electrons are then transferred from the hp heme to the lp heme of CcP. In some organisms, e.g., Ps. aeruginosa and Rb. capsulatus, the hp heme should be in the ferrous state for the enzyme to be active,254,255 whereas in other cases the enzyme is fully functional even with the ferric state of the hp heme, e.g., in N. europaea.154 The axial ligands for the hp heme are a His and a Met, similar to most c-type cytochromes. The lp heme is the site for H2O2 reduction. It is located at the N-terminal domain and has two His residues as axial ligands. The lp heme also displays a wide range of reduction potentials from as low as −330 mV in Ps. aeruginosa(163) to as high as +70 mV in N. europaea CcP.154 Electron transfer between the hp and lp hemes, which are 10 Å apart, is thought to occur through tunneling.255

Cyts c interact with CcP at a small surface patch of the enzyme which has a hydrophobic center and a charged periphery.256 The small size of the surface patch suggests that the interaction of the enzyme with the electron donor is transient, but at the same time is highly specific, which ensures complex formation due to desolvation of the surface waters and binding of cyt c. The charged periphery has been shown to be important to guide the donor toward the surface site, but it does not increase the specificity of the interactions or the ET rate.257 Mutagenesis studies in Rb. capsulatus CcP have shown that the interface at which the enzyme interacts with its electron donor cyt c2 involves nonspecific salt bridge interactions, as the extent of the interaction is dependent on the ionic strength of the solution.258 In contrast, in Ps. nautica CcP, the interaction surface between the enzyme and the electron donor cyt c is highly hydrophobic on the basis of studies which showed that the enzyme was active across a wide range of ionic strength of the solution.259 Studies from Pa. denitrificans CcP have shown that two molecules of horse heart cyt c are able to bind to the enzyme surface.260 Binding of an “active” and “waiting” cyt c in a ternary complex with the enzyme has been proposed to improve the ET rate. Structural studies of Pa. denitrificans CcP with the monoheme cyt c has shown that the heme of the donor binds above the hp heme of CcP, while the two molecules of horse heart cyts c bind between the two hemes of the enzyme.261

2.3.4.2. Cytochrome c as a Redox Partner to Denitrifying Enzymes: Nitrite, Nitric Oxide, and Nitrous Oxide Reductases

Denitrification is a stepwise process in the biological nitrogen cycle where nitrogen oxides act as electron acceptors and are sequentially reduced from nitrate to nitrite, nitrite to nitric oxide, nitric oxide to nitrous oxide, and finally nitrous oxide to nitrogen. These four steps of the nitrogen cycle are catalyzed by a diverse family of enzymes, viz., nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, nitric oxide reductase, and nitrous oxide reductase, all of which are induced under anoxic conditions.262−264 Various cyt c domains act as electron donors in the denitrification process. Reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide is catalyzed by one of the two structurally diverse enzymes that also have different catalytic sites: (a) cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase (cyt cd1 NiR)265,266 and (b) multicopper nitrite reductase (CuNiR).267,268 Cyt cd1 NiRs are periplasmic, soluble heterodimeric enzymes containing an ET cyt c domain and a catalytic cyt d1 domain in each subunit, while multicopper nitrite reductases are homotrimeric enzymes containing T1Cu as an ET site and T2Cu as a catalytic site. Cyts c552 are the putative electron donors of cyt cd1.269 Multicopper nitrite reductases have cupredoxin-like folds and use azurins and pseudoazurins as their biological redox partner, and as such are not expected to have cyt c domains. Contrary to this expectation, two instances have been found where a fusion of multicopper nitrite reductase and cyt c domains was discovered in the genomes of Chromobacterium violaceum and Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, where in both cases the cytochrome c domain is present at the end of a ∼500-residue-long sequence.79 These cyt c sequences are similar to those of the caa3 oxidase sequences.

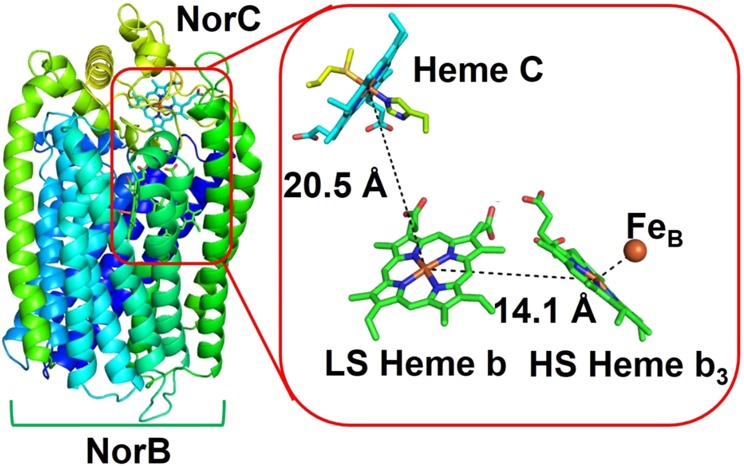

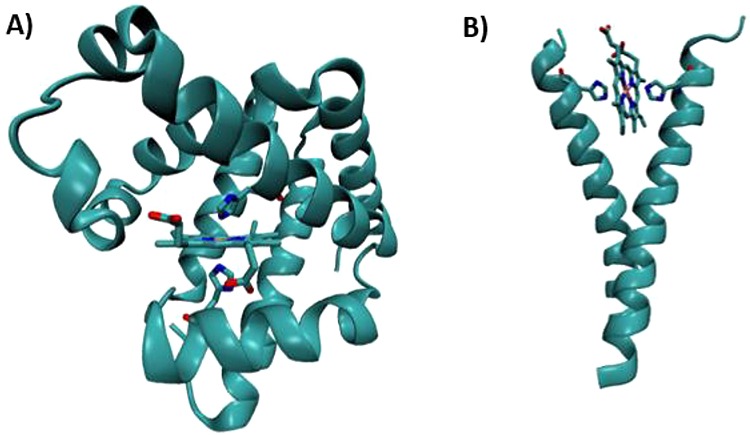

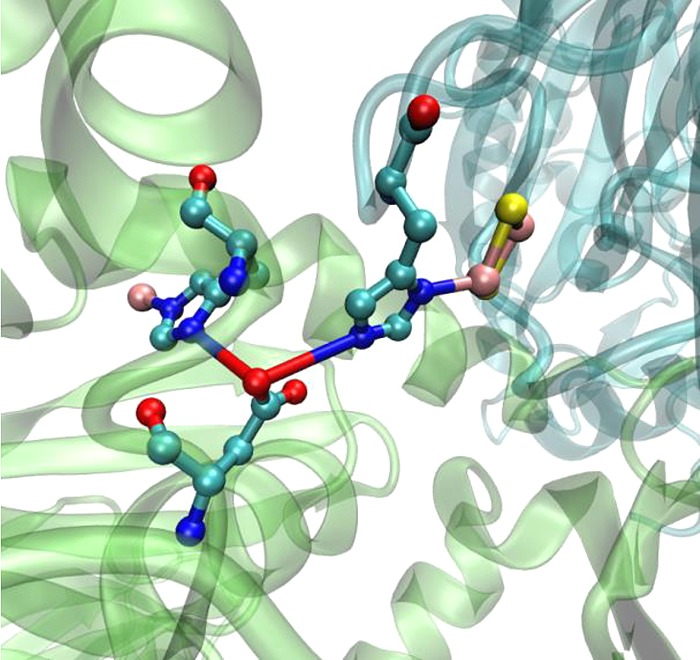

Nitric oxide reductases (NORs) are integral membrane proteins that catalyze the two-electron reduction of nitric oxide to nitrous reductase.270,271 A recent X-ray structure of the Gram-negative bacterium Ps. aeruginosa cyt c-dependent NOR (cNOR) (Figure 7) shows that the enzyme consists of two subunits.272 The NorB subunit is the transmembrane subunit and contains the binuclear active site consisting of an HS heme b3 and a nonheme iron (FeB) site. It also houses an LS ET cofactor heme b. NorC is a membrane-anchored cyt c and contains a c-type heme. Electrons are received from cyt c552 or azurin to the heme c, which then passes the electrons to LS heme b and then to HS heme b3 of the catalytic binuclear active site. The reduction potentials are +310, +345, +60, and +320 mV for heme c, heme b, heme b3, and the FeB sites, respectively.162

Figure 7.

X-ray structure of cyt c-dependent NOR (cNOR) (PDB ID 3O0R) from Ps. aeruginosa.

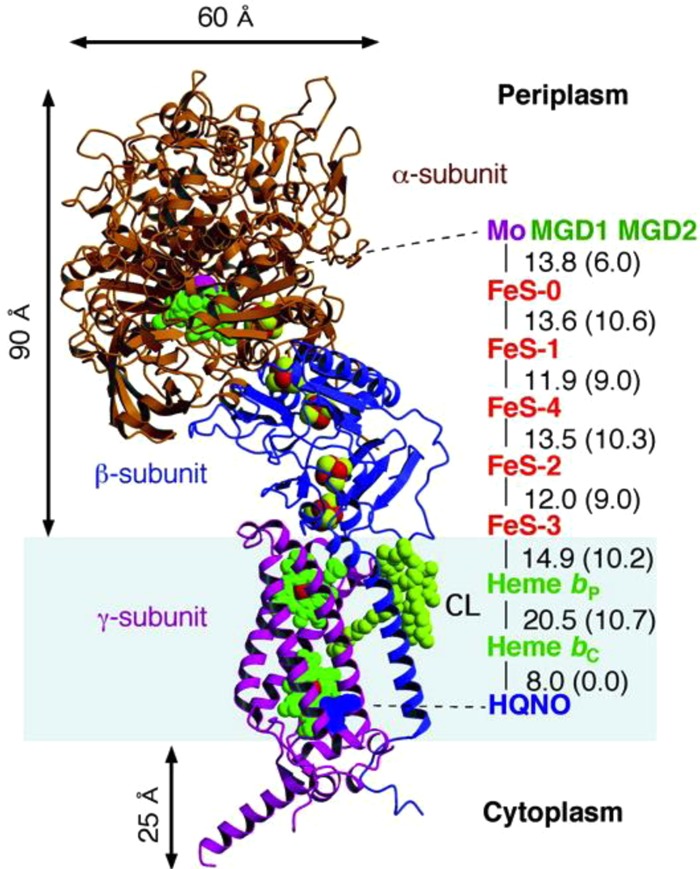

2.3.4.3. Cytochromes c as Redox Partners to Molybdenum-Containing Enzymes

Mononuclear molybdenum-containing enzymes constitute a group of enzymes that catalyze a diverse set of reactions and are found in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes.273,274 The general function of these groups of enzymes is to catalytically transfer an oxygen atom to and from a biological donor or acceptor molecule, and these enzymes are thus referred to as molybdenum oxotransferases. These enzymes possess a Mo=O unit at their active site and an unusual pterin cofactor which coordinates to the metal via its dithiolene ligand moiety. These Mo-containing enzymes are generally classified into three families depending on their structures and the reactions that they catalyze. The first one is xanthine oxidase from cow’s milk, which has an LMoVIOS(OH) (L = pterin) catalytic core and generally catalyzes the hydroxylation of carbon centers. The second family includes sulfite oxidase from avian or mammalian liver with a core coordination consisting of an LMoVIO2(S–Cys) moiety that catalyzes the transfer of an oxygen atom to or from the substrate’s lone pair of electrons. The third family of oxotransferases shows diversity in both structure and function and uses two pterin ligands instead of only one used by the first two classes. The reaction occurs at the active site core containing L2MoVIO(X), where X could be Ser as in DMSO reductase or Cys as in assimilatory nitrate reductase.

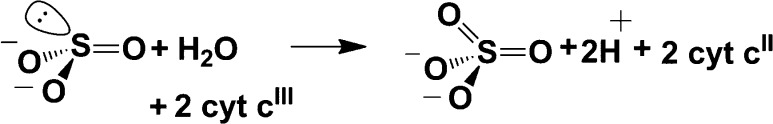

Xanthine oxidases have been reported to be coexpressed with three cyt c domains in Bradyrhizobium japonicum, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Ps. aeruginosa, and Ps. putida; however, the exact cause of this association is not well understood as these enzymes use flavins as their redox partners.79 Sulfite oxidase catalyzes the oxidation of sulfite to sulfate using 2 equiv of oxidized cyt c as physiological oxidizing substrates (Scheme 1).273 The molybdenum is reduced from the VI to the IV oxidation state, and the reducing equivalents are then transferred sequentially to the cyt c in the oxidative half-reaction. The assimilatory nitrate reductases (NRs) are found in algae, bacteria, and higher plants which uptake and utilize nitrate.273 These enzymes contain a cyt b557 and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) in addition to the Mo center. Electrons flow from FAD to cyt b557 to the Mo center under physiological conditions. The midpoint reduction potentials for FAD and cyt b557 from Chlorella NR have been determined to be −288 and −164 mV, respectively.189,190,275 The Mo center displays reduction potentials of +15 mV for the MoVI/V couple and −25 mV for the MoV/IV couple. These reduction potentials indicate that the physiological direction of electron flow is thermodynamically favorable. The cyt b557 domain of NR is homologous to the mammalian cyt b5, yeast flavo-cyt b2, and cyt b domain of sulfite oxidase.276

Scheme 1. Scheme Showing the Oxidation of Sulfite to Sulfate by Cyt c in Sulfite Oxidase.

Reprinted from ref (273). Copyright 1996 American Chemical Society.

The DMSO reductase family consists of a number of enzymes from bacterial and archaeal sources that display remarkable sequence similarity. Respiratory DMSO reductases are periplasmic and use membrane-anchored multiheme cyts c as electron donors that transfer electrons from the quinine pool to the periplasmic space. These cytochromes are about 400 amino acids long and are encoded in the same operon as the enzyme. In some γ-proteobacteria, the tetraheme cyts c occur as a fusion to the C-terminal cyt c binding domain of the enzyme. On the other hand, in some ε-proteobacteria single-domain cyts c have been coexpressed with the DMSO reductase and act as electron donors to the enzyme. Nonetheless, the cyt c sequences from both types of proteobacteria are clustered together, suggesting that even though the mechanism of ET is different, they are functionally similar.79 Even though these ET proteins in DMSO reductases are referred to as cyts c because they contain c-type hemes, their structural folds do not fall into the uniquely defined category of cyt c folds as mentioned in section 2.3.2.

2.3.4.4. Cytochrome c as a Redox Partner to Alcohol Dehydrogenase

The type II quinohemoprotein alcohol dehydrogenases are periplasmic enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes and transfer electrons from substrate alcohols first to the pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) cofactor, which subsequently transfers electrons to an internal heme group that is found in a cyt c domain.277 This cyt c domain of about 100 residues contains three α-helices in the core cytochrome domain and is similar to the cyt c domain in p-cresol methylhydroxylase (PCMH) from Ps. putida(278) and the cyt c551i from Pa. denitrificans.279

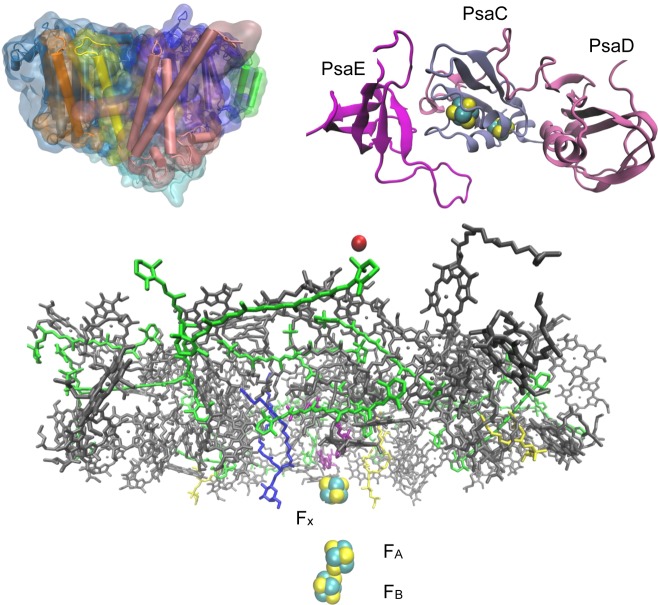

2.3.4.5. Involvement of Cytochromes c in Photosynthetic Systems

Photosynthesis involves the conversion of light energy to useful chemical forms of energy, which is accomplished by two large membrane protein complexes, photosystem I (PSI) and photosystem II (PSII).280 The catalytic cores of the two PSs are referred to as the reaction centers, which have [4Fe−4S] clusters and quinines as terminal electron acceptors for PSI and PSII, respectively. Like algae and higher plants, cyanobacteria also use PSI and PSII to convert light energy to chemical forms by producing oxygen from water oxidation. Even though cyanobacteria have a bis-His-coordinated PS-C550 cyt subunit in their PSII, apparently there is no redox role of this cytochrome.281,282 Being located at the lumenal surface of the enzyme, PS-C550 cytochrome acts as an insulator of the catalytic core from reductive attack and contributes to structural stabilization of the complex.283,284 The low midpoint reduction potentials of the soluble protein from −250 to −314 mV exclude any redox role of this class of cytochromes.285−288 When complexed with PSII, more positive values of reduction potentials have been determined.288,289 A reduction potential of +200 mV in PS-C550 cytochrome from Thermosynechococcus elongates has recently been reported,185 which suggests a possible role of this cytochrome in ET in PSII, despite a long distance (∼22 Å) between the PS-C550 cytochrome and its nearest redox center, the Mn4Ca cluster.290

In cyanobacteria, cyt c6 is known to act interchangeably with the copper protein plastocyanin as an electron donor to PSI, depending on the availability of copper,291−293 while in higher plants plastocyanin is the exclusive electron donor. On the basis of this observation, it has been proposed that cyt c6 is the older ancestor, which has been replaced by plastocyanin during evolution due to the shortage of iron in the environment.294

Another cytochrome, cyt cM, is found exclusively in cyanobacteria, but its role is ambiguous. It has been shown to be expressed under stress-induced conditions such as intense light or cold temperatures where the expression of both cyt c6 and plastocyanin is suppressed.295 Thus, it would be tempting to believe that cyt cM is a third electron donor to PSI in cyanobacteria under stress conditions, but experimental evidence goes against this hypothesis.296

2.3.4.6. Cytochrome c as a Single-Domain Oxygen Binding Protein

Sphaeroides heme protein (SHP) is an unusual c-type cytochrome which was discovered in Rb. sphaeroides.183 SHP (∼12 kDa) has a single HS heme with a reduction potential of −22 mV and an unusual His/Asn axial heme coordination in the oxidized form. SHP is spectroscopically distinct from cyts c′, which also have a HS heme. SHP was shown to bind oxygen transiently during slow auto-oxidation of the heme. The Asn axial ligand was shown to swing away upon reduction of the heme or binding of small molecules such as cyanide or nitric oxide. The distal pocket of SHP shows marked resemblance to other heme proteins that bind gaseous molecules.297 It has been suggested that SHP could be involved as a terminal electron acceptor in an ET pathway to reduce small ligands such as peroxide or hydroxylamine.297

2.3.5. Cytochrome c Domains in Magnetotactic Bacteria

Magnetotactic bacteria consist of a group of taxonomically and physiologically diverse bacteria that can align themselves with the geomagnetic field.298 The unique property of these bacteria is due to the presence of iron-rich crystals inside their lipid vesicles forming an organelle, referred to as the magnetosome. From sequence analysis, three proteins, MamE, MamP, and MamT, in the Gram-negative bacterium Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1 that contribute to the formation of the magnetosome have been discovered to contain a double -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- motif, characteristic of cyts c.186 All three proteins were expressed and purified in E. coli. Subsequent characterization of these proteins confirmed that MamE, MamP, and MamT indeed belong to c-type cytochromes, and they have been designated as “magnetochromes”. Midpoint reduction potentials were determined to be −76 and −32 mV for MamP and MamE, respectively. The presence of cyts c proteins in magnetotactic bacteria is intriguing and suggests that these proteins take part in ET, although the exact nature of their ET partners is not known. It has been hypothesized that the magnetochromes can either donate electrons to Fe(III) and participate in magnetite [mixture of Fe(III) and Fe(II)] formation or accept electrons from magnetite to maintain a redox balance, or they can act as redox buffers to maintain a proper ratio of maghemeite (all ferric irons) and magnetite.

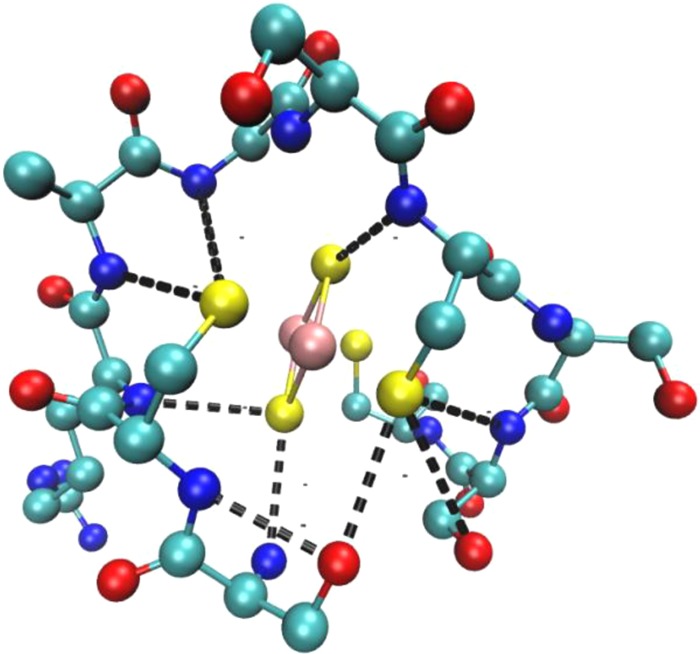

2.3.6. Multiheme Cytochromes c

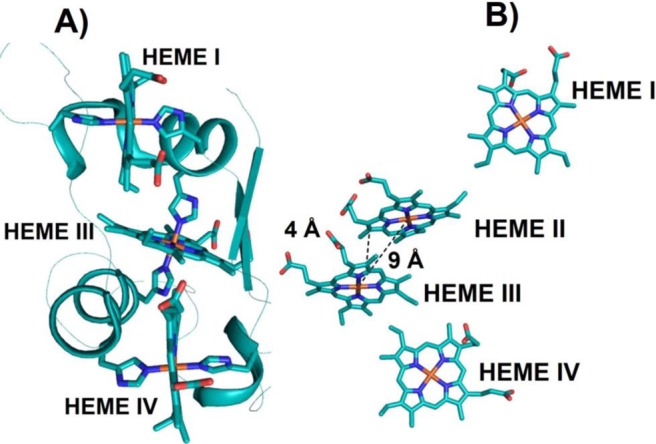

Multiheme cyts c occur as both soluble and membrane-anchored ET proteins in many enzymes across diverse functionalities.79,299 Triheme cyts c7 from Geobacter sulfurreducens and Dm. acetoxidans are involved in ET for Fe(III) respiration,207,300−303 although their exact roles are not known. These proteins have conserved secondary structural elements consisting of double-stranded β-sheet at the N-terminus followed by several α-helices. The protein displays a miniaturized version of the cyt c3 fold where heme II and the surrounding protein environment are missing (Figure 8). The arrangement of hemes is conserved in cyts c7 in terms of the distances between heme iron atoms and the angles between heme planes. Hemes I and IV are almost parallel to each other and are mutually perpendicular to heme III, which is in close contact with hemes I and IV. NMR and docking experiments suggest that heme IV is the region of interaction with similar physiological partners, while the other interacting partner would most likely interact through the region near hemes I and III. Such differences in interaction surfaces might play a role in choosing the right redox partners to perform different physiological functions.

Figure 8.

(A) X-ray structure of triheme cyt c7 (PDB ID 1HH5). All the hemes are bis-His-ligated. Cyt c7 is a minimized version of cyt c3 where heme II is missing. (B) Spatial arrangement of the four hemes in flavocytochrome c3 fumarate reductase (PDB ID IQO8). The heme irons of the heme pair II and III are in close proximity at 9 Å from each other, and the heme edges are 4 Å away.

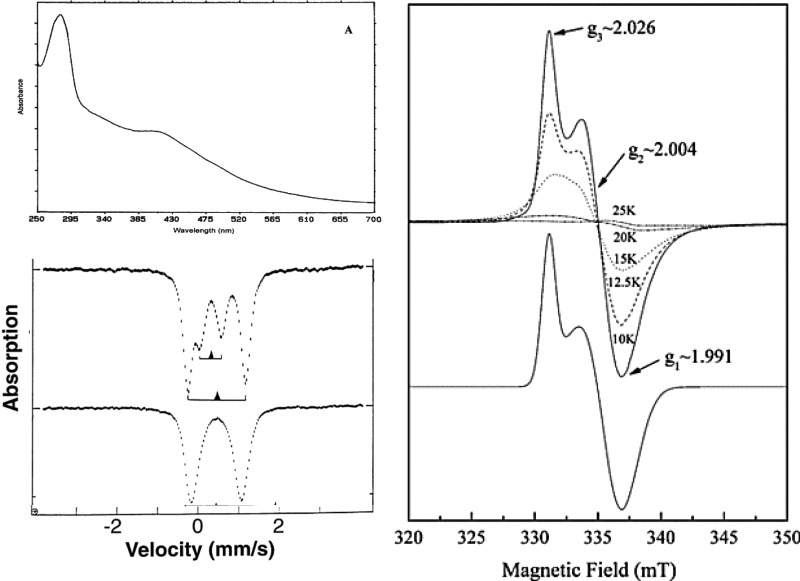

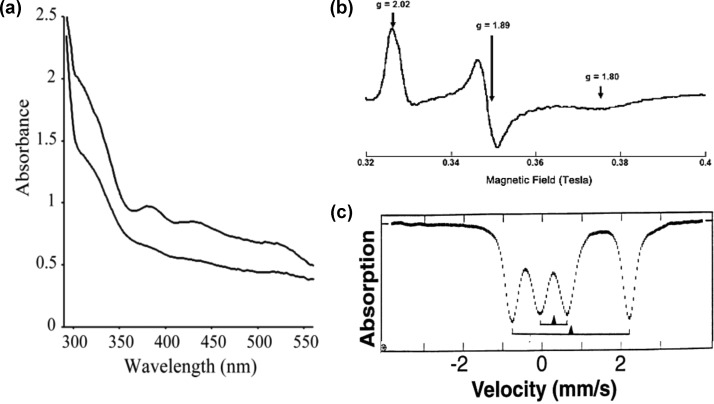

An unusual triheme cyt c is DsrJ from the purple sulfur bacterium Allochromatium vinosum that is a part of a complex involved in sulfur metabolism.182,304 Sequence analysis suggested the presence of three distinct c-type hemes containing bis-His, His/Met, and a very unusual His/Cys axial ligation, respectively. Subsequent cloning and expression of DsrJ in E. coli indeed confirmed the presence of three hemes, and EPR data showed the presence of partial His/Cys coordination to one of the hemes (His/Met is another possibility). From redox titrations, reduction potentials of the hemes were determined to be −20, −200, and −220 mV, respectively. Although the exact role of DsrJ is still unknown, its involvement in catalytic functions rather than in ET has been hypothesized.182

Other examples of multiheme cyts c include a tetraheme cyt c (NapC) involved in nitrate reductase from Pa. denitrificans,305 an Fe(III)-induced tetraheme flavocytochrome c3 (Ifc3)306 in fumarate reductase (Fcc3) from Sh. frigidimarina, an HAO containing eight heme groups for hydroxylamine oxidation in N. europaea,307 and a pentaheme nitrite reductase (NrfA) for nitrite reduction in Sulfurospirillum deleyianum.308,309 A periplasmic flavocytochrome c3 which is an isozyme of the soluble Fcc3 is also induced by Fe(III).310−312 The X-ray structure of this protein shows that the tetraheme arrangement in Fcc3 includes an intriguing heme pair where the two irons are only 9 Å from one another and the closest heme edges are within 4 Å (Figure 8).

The four hemes from Ifc3 and Fcc3 can be superimposed on four of the eight hemes in HAO.307 All four hemes of Ifc3 overlay on four of the hemes from the pentaheme NrfA,308 and all five hemes from NrfA overlay on five of the HAO hemes. Lastly, two hemes from Ifc3 overlay on two of the four hemes of cyt c554(122) from N. europaea, all four hemes of which overlay on four hemes from HAO. Despite such similarities in heme arrangement, there is no resemblance in the primary sequence of these enzymes. Nevertheless, such similar heme arrangements in these proteins suggest that they share a common ancestor, but have evolved divergently to perform four different reactions, viz., Fe(III) reduction, fumarate reduction, hydroxylamine reduction, and nitrite reduction.313 Some membrane-bound multiheme cytochromes, belonging to the NapC/NirT family, contain four heme binding sequences that have evolved due to gene duplication of diheme domains.314 In NapC and CymA all four hemes are 6cLS with bis-His axial ligation and display reduction potentials of +10 and −235 mV, respectively.305,313

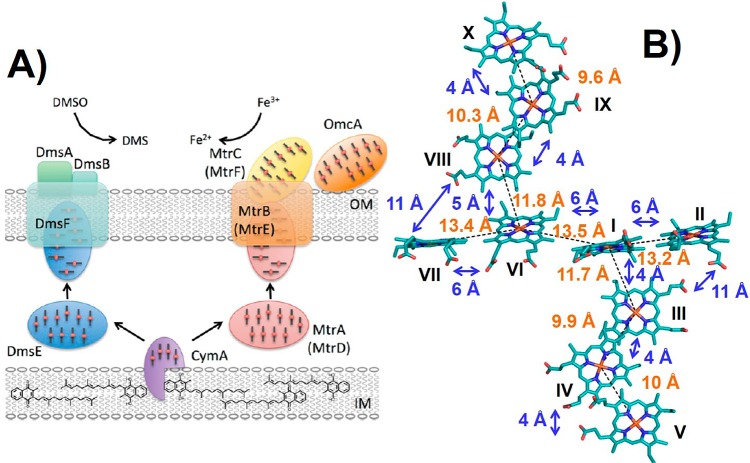

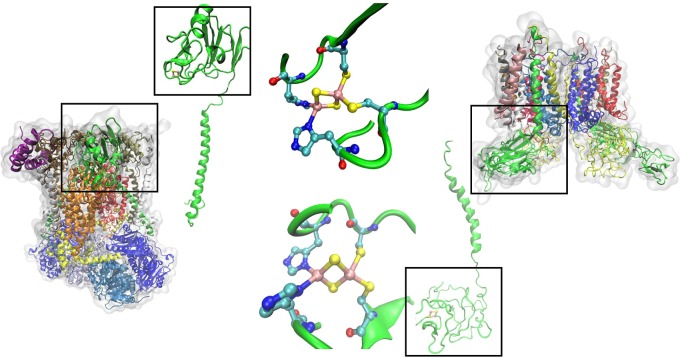

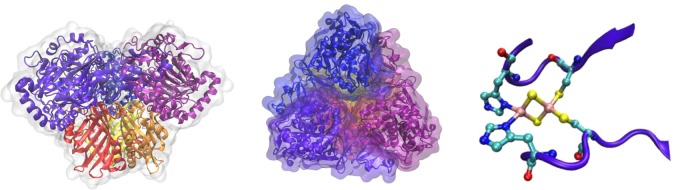

Sh. oneidensis MR-1 is a facultative anaerobe that is capable of using many terminal electron acceptors such as DMSO or metal oxides such as ferrihydrite and manganese dioxide outside the outer cell membrane, accepting electrons from the quinol pool and the tetraheme protein CymA.317−325 Electron transfer in Sh. oneidensis MR-1 is facilitated by two periplasmic decaheme cyts c, DmsE, which supplies electrons to DMSO, and MtrA, which is involved in ET to metal oxides (Figure 9). Both of these decaheme proteins have been proposed to be involved in a long-range ET across a ∼300 Å “gap” 326 (∼230 Å periplasmic gap and ∼40–70 Å thick outer membrane). Using protein film voltammetry, a potential window between −90 and −360 mV and an ET rate of ∼122 mV s–1 were measured for DmsE at pH 6.315 The measured reduction potential window for DmsE is shifted ∼100 mV lower than what was observed in MtrA,327−329 although the rate of ET is similar in both proteins. Although the MtrA and DmsE families of decaheme proteins facilitate long-range ET in Sh. oneidensis, it is not clear how ET is feasible across a 300 Å gap, especially given the fact that MtrA spans only 105 Å in length.330 Clearly, the arrangement of hemes must play a crucial role; however, the exact mechanism of this ET process is yet to be determined. A recent NMR study proposes the presence of two independent redox pathways by which the ET occurs from the cytoplasm to electron acceptors on the cell surface across the periplasmic gap in MtrA,331 one involving small tetraheme cyt c (STC) and the other involving FccA (flavocytochrome c). Both of these proteins interact with their redox partners CymA (donor) and MtrA (acceptor) through a single heme and show a large dissociation constant for protein–protein complex formation. Together, these facts suggest that a stable multiprotein redox complex spanning the periplasmic space does not exist. Instead, ET across the periplasmic gap is facilitated through the formation of transient protein–protein redox complexes.

Figure 9.

(A) Schematic model for DMSO reduction by DmsEFAB and iron reduction by MtrABC(DEF). Flows of electrons are shown with arrows. DmsE and MtrA(D) are proposed to accept electrons from the menaquinone pool via CymA. Multiheme groups in CymA, MtrACDF, and DmsE are shown. IM = inner membrane, and OM = outer membrane. (B) “Staggered-cross” orientation of the hemes in outer membrane decaheme MtrF (PDB ID 3PMQ). Heme numbering is shown as Roman numerals, heme–iron distances are shown in orange, and distances between heme edges are shown in blue. (A) Reprinted with permission from ref (315). Copyright 2012 Biochemical Society. (B) Adapted from ref (316) Copyright 2011 National Academy of Sciences.

MtrF is a decaheme c-type cytochrome found in the outer membrane of Sh. oneidensis MR-1 (Figure 9) which has been proposed to transfer electrons to solid substrates through the outer membrane, like its homologue MtrC, with the help of periplasmic MtrA and a membrane barrel protein, MtrE, that facilitates ET by forming contact between MtrA and MtrF.332,333 A recent crystal structure of MtrF shows that the protein consists of four domains, domains I and III containing β-sheets and domains II and IV being α-helices.316 The arrangement of the 10 bis-His-ligated hemes is like a “staggered cross” where four hemes (I, II, VI, VII) are almost coplanar with each other and are almost perpendicular to a group of three hemes (III, IV, V and VIII, IX, X) that are parallel to each other (Figure 9).

The reduction potentials of the hemes in MtrF lie in the range of 0 to −312 mV as determined by both solvated and protein film voltammetry. Unfortunately, reduction potentials of individual hemes have not been possible to assign due to their similar chemical nature. Molecular dynamics simulations show an almost symmetrical free energy profile for ET. Additionally, the computed reorganization energy range from 0.75 to 1.1 eV is consistent for partially solvent exposed heme cofactors capable of overcoming the energy barrier for ET.334,335 Further molecular details of ET in MtrF are unknown.

Multiheme cyts c also act as ET agents in the Fe(III)-respiring genus Shewanella.299 However, due to the fact that Fe(III) is soluble only at pH < 2, these organisms face the problem of moving electrons from the cytoplasm across two cell membranes to the extracellular space to reduce the insoluble extracellular species. It has been proposed that these organisms circumvent this problem by employing a number of tetraheme and decaheme cyts c which act as “wires” to transfer electrons between the inner and outer membranes.313,336

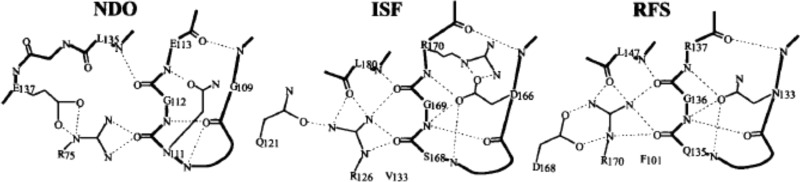

For tetraheme cyts c3, hemes I and III are covalently attached to the protein segment by a conserved -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His- sequence, while hemes II and IV are linked to the protein with the two Cys residues occurring in the sequence -Cys-Xxx-Xxx-Xxx-Xxx-Cys-His-.337,338 Although the overall orientation of hemes is conserved, the order of heme oxidation varies from source to source.217,339,340 The hemes in cyts c3 display redox cooperativity, such that the reduction potential of one heme is dependent on the oxidation state of the other hemes. The reduction potentials of the hemes in cyts c3 are also dependent on the pH, called the redox-Bohr effect,340−342 due to the interactions of the heme propionates in the H-bonding network and/or electrostatic interactions with the residues in the vicinity.341,343−345

Type I cyts c3 are soluble, periplasmic proteins and contain a patch of positively charged residues close to heme IV which have been proposed to interact with its partners.346 This class of cyts c3 mediate ET between periplasmic hydrogenases and transmembrane ET complexes where the electron acceptor is thought to be type II cyts c3. Type II cyts c3 are structurally similar to those of type I, but lack the lysine patch.347 It was proposed that type I cyts c3 receive electrons from hydrogenase and deliver them to type II cyts c3. Recent experimental evidence shows that these two types of cyts c3 form a complex with each other and are indeed physiological partners, but type I cyts c3 transfer only one electron to type II cyts c3 in solution.348,349

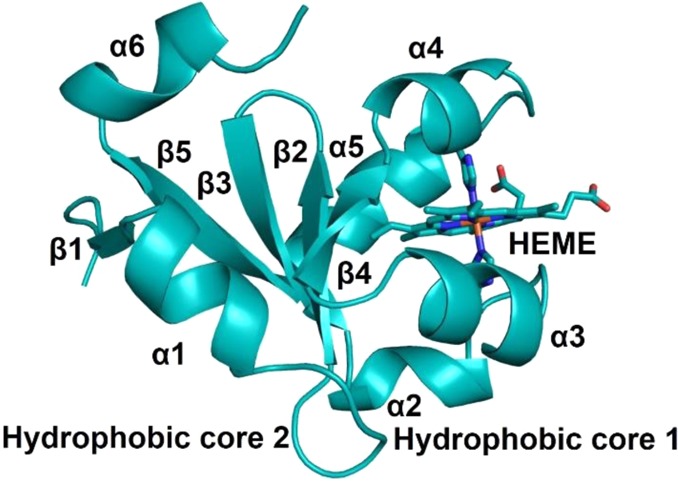

2.3.7. Cytochromes b5

Cyts b5 are ET hemoproteins containing bis-His-ligated b-type hemes and are found ubiquitously in bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals. Cyts b5 display reduction potentials that span a range of ∼400 mV.350−353 Mitochondrial and microsomal cyts b5 are membrane-bound, while those from bacteria and erythrocytes are soluble. In addition, there are various cyt b5-like proteins that act as redox partners in various enzymes such as flavocytochrome b2 (l-lactate dehydrogenase), sulfite oxidase, assimilatory nitrate reductase, and cyt b5/acyl lipid desaturase fusion proteins. The structures of cyts b5 from various sources reveal that there are two hydrophobic cores on each side of a β-sheet that belong to the α + β class (Figure 10).350 The larger hydrophobic core contains the heme binding crevice, while the smaller hydrophobic core is proposed to have only a structural role. About 3% of deoxyhemoglobin in adults is oxidized to inactive methemoglobin.354 Soluble cyts b5 in erythrocytes reduce methemoglobin to the functionally reduced deoxy form that binds oxygen. For this reaction electrons are transferred from NADH to methemoglobin via NADH cyt b5 reductase and cyt b5.355 Microsomal cyts b5 are found in the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum anchored to the membrane by a stretch of 22 hydrophobic residues.353 Microsomal cyts b5 are known to function by transferring electrons in fatty acid desaturation, cholesterol biosynthesis, and hydroxylation reactions involving cyts P450.356

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the X-ray structure of bovine cyt b5 that belongs to the α + β class (PDB ID 1CYO). Two hydrophobic core domains, six α-helices, five β-strands, and 6c bis-His-ligated heme are shown. Adapted from ref (357). Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

Two different forms of cyt b5 have been detected in rat hepatocyte; one is associated with the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (microsomal, or Mc, cyt b5), while the other is anchored to the outer membrane of liver mitochondria (OM cyt b5).358−362 These two types of cyt b5 display a reduction potential difference of 100 mV (−107 mV for OM cyt b5,187,363 −7 mV for Mc cyt b5).180 The rat OM cyt b5 is involved in the reduction of cytosolic ascorbate radical using NADH as the electron source.364,365 The mammalian OM cyt b5 and Mc cyt b5 have three different domains, an N-terminal hydrophilic domain that binds the heme, an intermediate hydrophobic domain, and a C-terminal hydrophilic domain. The N-terminal heme binding domains for both types of cyts b5 have very similar structural folds consisting of six α-helices and four β-strands. The heme is bound in a pocket formed by four α-helices and a β-sheet formed by two of the β-strands.141,366 Studies relating to the complex formation and ET rates between cyts b5 and its redox partners suggest that the nature of interactions between two proteins is primarily electrostatic and the heme edges of cyts b5 make contacts with electron donors and acceptors.350 Within this general area, there are multiple overlapping sites with which cyts b5 interact with its various partners.

A gene encoding a cyt b5-type heme from the protozoan intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia was recently cloned into E. coli as a soluble protein.367 The spectroscopic properties of this cloned cyt b5 are similar to those of the microsomal cyts b5, and homology modeling suggests the presence of a bis-His-ligated heme. Residues near the heme binding core from Giardia cyt b5 are comprised of charged amino acids and differ from those of other families of cyt b5. The reduction potential of the heme was determined to be −165 mV.

2.3.7.1. Heme Orientation Isomers in Cytochromes b5

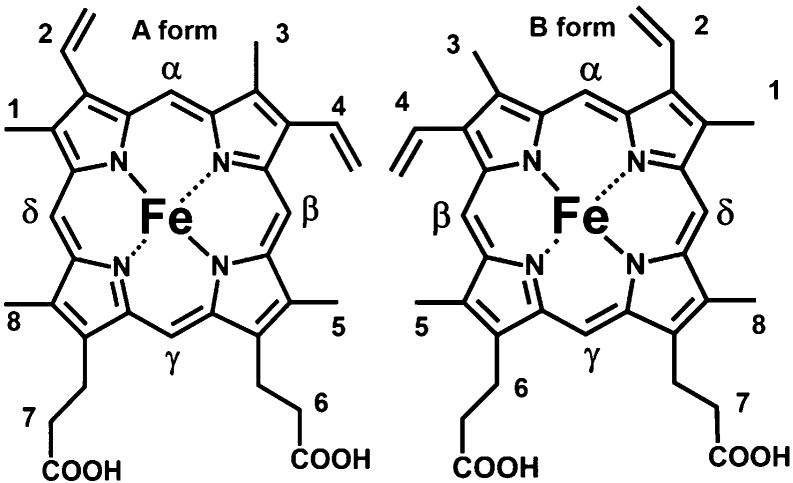

Solution NMR studies of the soluble fragment of cyt b5 suggested the coexistence of two different species that contained two orientation isomers (forms A and B, Figure 11) of heme that are related by a 180° rotation about an axis through the heme α,γ-meso-carbon atoms.368−372

Figure 11.

Two orientation isomers (A and B forms) of heme observed in solution studies of the soluble fragment of cyt b5. The two isomers are related by a 180° rotation around the α,γ-meso-carbon atoms.

The relative population of the two isoforms A and B varies from species to species. In bovine and rabbit, the A/B ratio is ∼10/1,177,368,370,373 20/1 in chicken cyt b5,374 6/4 in rat Mc cyt b5,374 and 1/1 in the OM cyt b5.375 Even though reconstitution of apo cyt b5 with heme resulted in the initial formation of a 1/1 ratio of species A and B, they converted back to the proportion found in the thermodynamically stable native state after some time.370,373 Reduction potentials of +0.8 and −26.2 mV were calculated for isoforms A and B, respectively, from spectroelectrochemical titrations.177 Interaction between the 2-vinyl group and side chains of residues 23 and 25 was initially thought to be the driving factor that dictated the heme orientation isomers.368,374,376 This theory was disputed in later studies.375 It is now generally accepted that the heme itself can adapt to the surrounding environment by a rotation of the porphyrin plane around an axis perpendicular to the iron, which is proposed to be the determining factor that caused the different heme orientation in species A and B.376−378 Several studies have indicated that residue His39 is the major determining factor of the electronic state that orients the molecular orbitals for easy ET through the exposed pyrrole ring III and meso-carbon heme edge.370,379,380

2.3.8. Cytochrome b562

Cyt b562 is a 106-residue monomeric heme protein of unknown function found in the periplasm of E. coli. It is a four-helix bundle protein where the helices are oriented antiparallel to each other (Figure 12).381,382

Figure 12.

NMR structure of the antiparallel four-helix bundle cyt b562 (PDB ID 1QPU). His/Met axial coordination to the heme iron is shown.

The protein has a noncovalently bound 6cLS heme with His102 and Met7 axial ligands, even though this protein is structurally homologous to cyt c′ that contains a covalently bound 5cHS c-type heme. In the oxidized unfolded state, the heme of cyt b562 is converted to 5cHS with His102 as the only axial ligand.383 The folding properties of this protein are highly dependent on the pH. At pH 7 the reduction potential of the heme in the folded state is 189 mV, while that of the unfolded state is −150 mV, suggesting that the reduced state has a greater driving force for folding than the oxidized state.176,384−387 Unfolding of the oxidized state of the protein occurs reversibly with a midpoint GuHCl concentration of 1.8 M, while the reduced state shows irreversible unfolding at >5 M GuHCl due to heme dissociation. Folding of the reduced state has been shown to be triggered by photoinduced ET to the oxidized form of the protein under 2–3 M GuHCl concentrations. A folding rate of 5 μs was extrapolated in the absence of denaturant, which is similar to the intrachain diffusion time scale of the polypeptide.388

2.4. Designed Cytochromes

In addition to studying native systems by a top-down approach, in recent decades, many groups have adopted a bottom-up approach of building minimal functional proteins that mimic natural ones. The theoretical simplicity and ubiquity of cytochromes has made them appealing targets for design, and a number of artificial cytochrome-mimicking proteins have been engineered, with varying levels of sophistication. In this issue of Chemical Reviews, Pecoraro and co-workers give a thorough review of protein design strategies and successes, including designed heme ET proteins.3000 Here, we give a brief account focusing on the redox properties of designed 6-coordinate heme proteins mimicking ET cytochromes.

2.4.1. Designed Cytochromes in de Novo Designed Protein Scaffolds

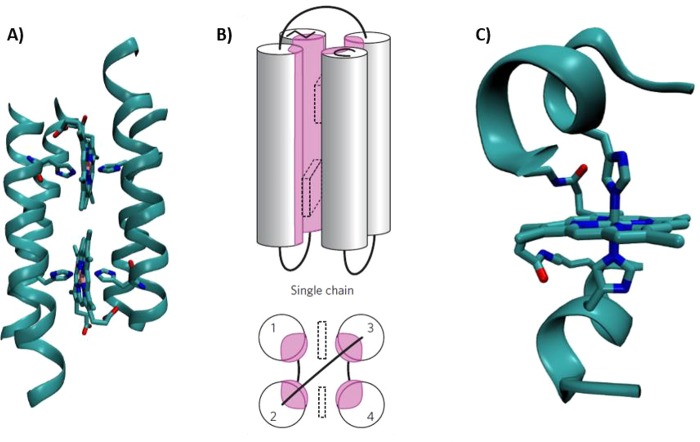

Two de novo heme proteins called VAVH25(S–S) and retro(S–S)389 were designed to bind heme in a bis-His coordination, by strategically engineering His residues into the de novo cystine-cross-linked, homodimeric four-helix bundle called α2.390−392 Both sequences yielded artificial cytochromes with dissociation constants for heme in the submicromolar range, and spectroscopic properties of these proteins were consistent with low-spin bisimidazole-ligated heme, with reduction potentials of −170 and −220 mV for each of the proteins. Although these potentials are nearly unchanged from the potentials of bisimidazole heme in aqueous solution, the success of incorporation demonstrated the power of rational de novo design and set the stage for rapid development of more complex and nativelike structures. Using an alternative tetrameric protein scaffold, consisting of two pairs of disulfide linked α-helices, a series of proteins mimicking the heme b domain of cytochrome bc1 were also designed by strategic placement of histidine residues. The designed proteins incorporated either two or four hemes per bundle,393 with potentials of the individual sites reported to range from −230 to −80 mV in the tetraheme construct. More impressively, the sites showed cooperative redox properties, with the presence of a second ferric heme site proposed to raise the potential of the first by ∼115 mV through electrostatic interactions (vide infra).393,394 In a systematic study of the electronic properties of this scaffold, varying the heme, pH, and local charge could achieve a potential range of 435 mV (−265 to +170 mV),395 over half the 800 mV range covered by native cytochromes. Interestingly, investigation of the more natural mutation of one of the His ligands with a Met resulted in only a 30 mV increase in reduction potential, and substitution of heme b with heme c gave no significant change.396 Rational mutagenesis of several core residues, as well as incorporation of helix–turn–helix and asymmetric disulfide bonds, further improved the structural rigidity and uniqueness of the designed scaffolds.397,398 Subsequently, this maquette system was extended in a variety of ways to achieve coupling to electrode surfaces,399 incorporation of non-natural amino acid ligands,400 and binding of two different hemes—which mimics the structure of ba3 oxidases.401 Particularly exciting is the demonstration of coupling of ET and protonation of carboxylate residues on the protein,402−404 which is relevant for understanding and engineering proton pumping.

On the basis of recent developments in structural understanding of cytochrome bc1 and improvements in computational modeling, Ghirlanda et al. investigated designing a more structurally unique mimic of the bc1 complex. The structure of the heme b binding portion of bc1 was modeled as a coiled coil, and secondary coordination sphere interactions to the coordinating histidines, such as conserved Gly, Thr, and Ala residues, were added to stabilize the orientation of the His ligand and tune its electronic properties (Figure 13A).405 The potentials were measured by cyclic voltammetry (CV) as −76 and −124 mV in the oxidative and reductive directions, respectively, at pH 8, significantly higher than the potential of aqueous bisimidazole heme and earlier bis-His-ligated designed proteins. The hysteresis in the potentials is attributed to conformational reorganization of the ligating His residues between the oxidized and reduced forms. The model was further improved by linking and expression as a single chain for more efficient structure determination studies,408 as well as incorporation into a membrane.409

Figure 13.

Structural models of designed cytochrome models in de novo scaffolds. (A) A design model for a homodimeric four-helix tetraheme binding protein inspired by cyt bc1. Remade from coordinates courtesy of G. Ghirlanda and W. F. DeGrado.405 (B) Schematic representation of monomeric four-α-helix maquettes used to mimic ET cytochromes. Reprinted with permission from ref (406). Copyright 2013 Macmillan Publishers Ltd. (C) Crystal structure of Co(II) mimichrome IV (PDB 1PYZ).407

Most recently, Dutton and co-workers have reported the design and thorough characterization of a monomeric, single-chain four-α-helix bundle maquette protein, which can bind up to two hemes (Figure 13B). It is particularly noteworthy for the subject of this review that the redox properties of this scaffold as a function of charge distribution were systematically analyzed. By raising the total charge uniformly from −16 to +11, the reduction potential of both hemes changed from −290 to −150 mV, as expected. Furthermore, the potentials of the hemes could be changed individually by only increasing the charge at one end of the protein; the potentials of the individual hemes were −240 and −150 mV. Finally, it was demonstrated that the reduced negatively charged protein could transfer an electron to native cytochrome c with rate constants approaching those of native photosynthetic and respiratory electron transport chains. Such a single-chain four-helix bundle was also used to build an artificial oxygen binding cytochrome c with an intramolecular B-type ET heme with a 60 mV lower reduction potential, mimicking a natural ET chain.410

More rational computational protein design algorithms have also been brought to bear on the de novo design of artificial cytochromes. Xu and Farid used the algorithm named CORE411 to design a nativelike four (27 amino acid)-helix bundle that binds two to four hemes in a bis-His fashion.412 The α-helical character was confirmed by circular dichroism (CD), and the binding affinity for the first 2 equiv was determined to be in the micromolar range, while, due to negative cooperativity, the remaining sites had Kd > 3 mM. The measured potentials for the diheme and tetraheme protein were −133 to −91 and −190 to −0110 mV, respectively.

While the rationally guided design strategies described above have been very successful, the lack of a priori knowledge about the necessary structural features for design of functional metalloproteins limits the scope of sequence and structure space that is probed by the strategy. As a complementary approach, Hecht and co-workers have utilized a semirational “binary code” library generation method to produce 15 74-residue sequences that formed helical bundles and bound heme,413 one with submicromolar affinity. Extending this scaffold further produced five 102-residue sequences with higher stabilities and more “nativelike” structures.414 Analysis of a handful of these proteins revealed spectroscopic features typical of low-spin heme proteins and reduction potentials ranging from −112 to −176 mV.415 Furthermore, it was demonstrated that at least one construct was electrically competent on an electrode.416 A similar semirational combinatorial approach was utilized by Haehnel and co-workers, who combined it with template-assisted synthetic protein (TASP) methods, in which two sets of antiparallel helices are templated onto a polypeptide ring, to design and screen an impressive library of 399 cytochrome b mimicking four-helix bundles.417,418 Using a colorimetric screen, the potentials were estimated to range from −170 to −90 mV. It was also demonstrated that the proteins could be incorporated onto electrodes419,420 and achieved estimated ET rate constants comparable to those of native cytochromes.

A number of smaller, water-soluble peptide-based cytochrome mimics have also been developed, utilizing one or two short α-helical peptides. Two groups independently developed heme compounds with covalently attached, short α-helix-forming peptides, with His ligands. In one case, peptide-sandwiched mesoheme (PSM) compounds were prepared by covalently attaching a 12-mer peptide to each of the two propionate groups of the heme via amide bonds with lysine groups on the peptide.421 Although the helicity of the free peptide was low, upon ligatation of the heme, the helicity was seen by CD to increase to ∼50%, and the electronic spectra were consistent with bis-His heme ligation, similar to b-type cytochromes.421,422 Further work suggested that aromatic side chain interaction with the heme, such as Phe and Trp, improves helix stability and heme binding,423 and covalent linkage of the peptide termini via disulfide bonds resulted in further stabilization.424 Studies of the redox properties of a PSM and a mutant with an Ala to Trp mutation, (called PSMW), highlight the importance of stability in determining reduction potential, with more stable helix binding in PSMW lowering the reduction potential by 56 mV (−281 to −337 mV), due to the increased ability of the His ligands to stabilize the Fe(III) state.425 The authors propose that this effect may also explain the difference in potential between mitochondrial and microsomal cyts b5.

Similarly, short α-helical peptides, based on the heme binding peptide fragment of myoglobin, have been covalently attached to deuterohem by a similar amide-bond attachment strategy, yielding compounds known as mimochromes.426 It is noteworthy that the peptides retained their α-helical character even in the absence of heme binding.426,427 The stability of the model was further improved in later revisions by enhancing the intramolecular interpeptide interactions through extending the peptide (mimochrome II)428 or rational mutagenesis (mimochrome IV).429 A crystal structure of the Co(II) derivative of mimochrome IV has been obtained and substantiates the designed structure (Figure 13C).407 The reduction potential of Fe mimochrome (IV) at pH 7 is −80 mV, though it exhibits strong pH dependence over the range of pH from 2 to 10 (∼+30 to −170 mV).429 The low-pH dependence is attributed to the His ligands unbinding from the heme, while the high-pH transition is proposed to be caused by deprotonation of a nearby arginine; however, this is surprising due to the 4 orders of magnitude higher apparent acidity and requires further investigation to be proven. Still, it is exciting that this simple mimic is well folded enough to be crystallized and has a potential in the range of those of native cytochromes.

Intermediate between these covalently attached heme–peptide models and full polyhelical bundles described above, heme protein complexes consisting of heme ligated by designed short peptides that are not covalently attached have also been developed.430−434 Studies on the binding of a variety 15-mer peptides showed a strong correlation between peptide–heme affinity and reduction potential (−304 to −218 mV), with lower potentials for more stable complexes, consistent with the results of studies on PSMs.425,431 The overall low potential was attributed to the inability of the small peptides to reduce the strong dielectric constant of the solvent, as native proteins do (vide infra). To further improve the stability, two peptides were covalently linked at both ends by disulfide ligands, resulting in a series of cyclic dipeptide heme binding motifs, with reduction potentials ranging from −215 to −252 mV.433

Interestingly, in a step away from the helix bundle paradigm, Isogai and co-workers were able to rationally design a series of de novo proteins that would fold into a globin fold, but with only ∼25% sequence identity to sperm whale myoglobin.435,436 Although the proteins were designed for a 5-coordinate myoglobin-like heme binding site, the resulting proteins were consistent with 6-coordinate bis-His-ligated heme. In these scaffolds, the reduction potential was in the range of −170 to −200 mV, similar to that of aqueous bis-Im heme, which was attributed to higher solvent access to the heme due to the molten-globular state of the proteins. This was further supported by the re-engineering of a nonheme globin protein, phycocyanin, into a heme binding protein (vide infra), which had a more unique, hydrophobic, and nativelike core structure and 50 mV higher reduction potential.437

2.4.2. Designed Cytochromes in Natural Scaffolds