Abstract

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) affects nearly 150,000 patients per year in the US, and is associated with high mortality (≈40%) and suboptimal options for patient care. Mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation are limited to short-term use due to ventilator-induced lung injury and poor bio-compatibility, respectively. In this report, we describe the development of a biohybrid lung prototype, employing a rotating endothelialized microporous hollow fiber (MHF) bundle to improve blood biocompatibility while MHF mixing could contribute to gas transfer efficiency. MHFs were surface modified with radio frequency glow discharge (RFGD) and protein adsorption to promote endothelial cell (EC) attachment and growth. The MHF bundles were placed in the biohybrid lung prototype and rotated up to 1,500 revolutions per minute (rpm) using speed ramping protocols to condition ECs to remain adherent on the fibers. Oxygen transfer, thrombotic deposition, and EC p-selectin expression were evaluated as indicators of biohybrid lung functionality and biocompatibility. A fixed aliquot of blood in contact with MHF bundles rotated at either 250 or 750 rpm reached saturating pO2 levels more quickly with increased rpm, supporting the concept that fiber rotation would positively contribute to oxygen transfer. The presence of ECs had no effect on the rate of oxygen transfer at lower fiber rpm, but did provide some resistance with increased rpm when the overall rate of mass transfer was higher due to active mixing. RFGD followed by fibronectin adsorption on MHFs facilitated near confluent EC coverage with minimal p-selectin expression under both normoxic and hyperoxic conditions. Indeed, even subconfluent EC coverage on MHFs significantly reduced thrombotic deposition adding further support that endothelialization enhances, blood biocompatibility. Overall these findings demonstrate a proof-of-concept that a rotating endothelialized MHF bundle enhances gas transfer and biocompatibility, potentially producing safer, more efficient artificial lungs.

Keywords: endothelialization, biocompatibility, oxygenator, surface modification

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is an inflammatory lung condition associated with a variety of diseases such as pneumonia, shock, sepsis, or trauma, and may result from direct physical or toxic injury to the lungs (Kollef and Schuster, 1995; Ware and Matthay, 2000). ARDS affects nearly 150,000 patients per year in the US, with a high mortality rate (40%) and many surviving patients suffering debilitating and permanent sequelae including pulmonary fibrosis (Leaver and Evans, 2007; Notler et al., 2005; Peter et al., 2008). Treatment consists primarily of palliative therapies including mechanical ventilation, supplemental oxygenation, and circulatory support. Iatrogenic injuries (ventilator-induced lung injury; hyperoxic lung injury) due to these efforts are well known and the most significant recent improvement in patient outcome for ARDS has been the use of low tidal volume ventilation (Barry and Crapo, 1985; Gonzalvo et al., 2007; Hopkins et al., 1999; Kazzaz et al., 1996; Kollef and Schuster, 1995; Peter et al., 2008; Ruffini et al., 2001; Ware and Matthay, 2000; Welty et al., 1993).

In advanced ARDS, ventilators become inadequate, potentially leading to the addition of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). ECMO utilizes an external circuit consisting of a blood pump, an oxygenator, a heat exchanger, and several feet of tubing. The oxygenators contain microporous hollow fibers (MHFs), across which patient blood is passed for artificial oxygenation, giving the patient’s lungs time to heal (Ko et al., 2006). ECMO circuits were primarily designed for open-heart surgical procedures (4–8 h), and require high levels of anticoagulation. MHFs are functionally limited by plasma “weeping” across the membrane to the gas side, and biocompatibility issues associated with thrombosis and/or bleeding (Lund et al., 1998; Nasu et al., 1984). Recent progress in artificial lung technology has yielded fibers more resistant to plasma weeping, but biocompatibility still remains a key limitation (Sato et al., 2007). Sustained use in ARDS patients leads to increasing complications, making the treatment no more favorable than mechanical ventilation (Go and Macchiarini, 2008; Peek et al., 2006; Zwischenberger and Alpard, 2002).

Endothelialized MHFs have been suggested as a means to improve ECMO biocompatibility (Ohata et al., 1998; Sawa et al., 1998, 2000; Takagi et al., 2003). This approach seeks to mimic the in vivo function of vascular endothelial cells (ECs) to yield a biocompatible surface, actively inhibiting platelet activation and deposition (Colman, 1995; Paszkowiak and Dardik, 2003; Watson, 2009). Since MHFs are selected, in part, due to resistance to cell adhesion, surface modifications have been utilized to promote cell attachment (Takagi et al., 2003). While surface treatment and endothelialization of MHFs may produce a more biocompatible surface, gas diffusion across the membrane surface may be limited by deposited protein and cellular material. Although diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide readily occurs across the alveolar–capillary barrier in the native lung, it is not clear what the impact of endothelialization would be on gas transfer in the MHF system. Augmenting the velocity of passing blood to reduce the boundary layer thickness either by rotation or pulsation, has been shown to improve gas diffusion and is being proposed in new oxygenator designs (Budilarto et al., 2005; Eash et al., 2005, 2006, 2007; Mueller et al., 2002; Svitek et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009). Such mixing may act to offset gas transport limitations by the addition of an endothelial layer, but the effects of the increased shear stresses on ECs under such rotational mixing are not clear.

The biohybrid artificial lung prototype reported in this article employs active mixing produced by rotation of a surface modified and endothelialized MHF bundle, shown in Figure 1. The novel aspects of the biohybrid artificial lung design are an endothelialized layer on the outer lumen of the MHFs to present a more biocompatible blood-contacting surface, while the rotation of this fiber bundle should increase the effective gas transport per surface area. Beyond presenting the design of this device, our objective in this report was to evaluate approaches to achieve a high level of endothelialization on the MHF bundle and the ability to maintain endothelialization under MHF bundle rotation. Furthermore, we evaluated the resistance of these endothelialized MHFs to thrombotic deposition and other features of EC phenotype, and oxygen transfer with and without MHF endothelialization and mixing.

Figure 1.

Microporous hollow fiber mat potted around a titanium core: (A) side view, (B) front view of the core, (C) magnified view of the core showing fiber terminations (D) custom made seeding tube with a permeable transparent membrane cap (E) assembled biohybrid artificial lung prototype filled with culture medium in an incubator. The two tubes extending from the top of the reactor portion are for gas monitoring.

Materials and Methods

Surface Modification of MHFs to Support Endothelial Cell Growth

Mats of Celgard polymethylpentene (PMP) MHFs with nylon support fibers (a gift from Membrana) were cut into patches of 30 fibers (2.5 cm × 1.2 cm). Six MHF patches were affixed with polycin/vorite glue (60% Polycin, 40% Vorite by mass, Cas Chem) in a 50mL conical tube. PMP MHFs were chosen due to an asymmetric geometry, which is attractive for its resistance to plasma weeping and would theoretically not experience increased plasma weeping if made hydrophilic by surface modification to support cell adhesion (Khoshbin et al., 2005; Lawson and Holt, 2007; Toomasian et al., 2005). Select groups of fiber patches were exposed to radio frequency glow discharge (RFGD; March Plasma Systems, Concord, CA) treatment while in the conical tube (0.3 Torr vacuum and ammonia gas for 60 s at 100 W). Contact angle measurements were made with a goniometer (Advanced Surface Technology, Billerica, MA) to verify an increase in hydrophilicity after RFGD. All fiber groups were sterilized with ethylene oxide. Select groups received additional surface treatment with 10 µg/mL type I collagen, 0.2% gelatin, or 5 µg/mL fibronectin (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Unmodified fiber patches served as controls.

Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs, Cambrex, Rutheford, NJ) were cultured in endothelial growth medium (EGM™MV, Cambrex) until confluent before being seeded onto MHFs. After surface modification, 5 × 105 BAECs in 10 mL of culture medium were added to the patch-containing tubes and placed on a hematology mixer overnight, followed by removal and transfer of the patches to six-well tissue culture plates for static culture. Cell number was indirectly quantified with methylthiazolyl diphenyl-tetrazolium (MTT, Sigma) at days 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 using a calibration curve with known cell numbers. The percent cell coverage was calculated using the surface area of the fibers and an estimated surface area of an EC (Schneider et al., 1997).

Blood Biocompatibility of Endothelialized Patches

The blood biocompatibility of endothelialized MHF patches was evaluated by examining thrombotic deposition from bovine blood under protocols approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Citrated blood collected from the jugular vein of adult female Holstein cows was mixed with 0.6 U/mL of un-fractionated heparin (Baxter, Deerfield, IL), and re-calcified with a 1M CaCl2 solution to a final concentration of 2–3mM calcium and balanced to a pH of 7.4 with a 1M NaOH solution. All blood was refrigerated and used within 24 h of collection. For each experiment, 5mL of prewarmed blood was added to a siliconized Vacutainer® tube with no additives (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing an endothelialized MHF patch and was placed on a hematology mixer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for 2 h at 37°C MHF patches were removed, rinsed in a heparin/saline solution (10 U/mL heparin), and imaged with a digital camera on a dissecting microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, SMZ660) at 6× total magnification. A threshold was applied for the red thrombus in each image, and the percentage of the image covered by the thrombus was computed in Photoshop CS (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Two unmodified, non-endothelialized MHF patches not exposed to culture medium were utilized for control purposes.

Biohybrid Artificial Lung Prototype Design and Development

Raw materials used to create the biohybrid artificial lung included a cast acrylic housing, removable Teflon housing caps (RT Dygert, Niles, IL), and a central titanium shaft (Grade 2, ASTM B265) treated with diamond-like carbon coating (Anatech Ltd., Union City, CA), and stainless steel bearings assembled using titanium screws mounted to a titanium module base. Oxygen (Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark) and carbon dioxide (Lazar, Los Angeles, CA) probes attached through ports in the housing were used to monitor gas partial pressures within the biohybrid artificial lung (Fig. 1).

To provide active mixing, the fiber bundle was rotated within the medium, with gas flow through the lumen of MHFs during rotation. A continuous duty servo-brushless motor and power supply provided the rotational speed in small increments from 1 to > 1,500 rpm (Parker, Cleveland, OH). Custom made Teflon seals were utilized to support the high levels of torque required for steady rotation of the MHF bundle. Seals made from nitrile or vyton (Chicago Rawhide, Salt Lake City, UT), were found to be unsuitable due to leakage and wear debris. Room temperature air was directed onto the housing to compensate for heat generation.

Endothelialization of MHF Bundles

MHF mats were wrapped three times around a titanium core and potted with the polycin/vorite glue to form a concentric, three-layer fiber bundle (Fig. 1A–C). MHF bundles were surface modified with RFGD followed by fibronectin adsorption that provided optimal cellular growth and thrombo-resistance from the MHF patch studies. Surface modified MHF bundles were seeded with 15 × 106 BAECs in 10 mL of medium in acrylic seeding tubes with a permeable fluoro-ethylene based polymer membrane to allow for improved gas transfer, shown in Figure 1D. Seeding tubes containing BAECs and MHF bundles were placed on a hematology rocker (Fisher Scientific) for 12–24 h in an incubator prior to static culture. Near confluent cell growth was achieved 1–2 weeks after seeding, with daily media exchange.

Rotation of Endothelialized MHF Bundles

After near-confluence was achieved in static culture, endothelialized MHF bundles were transferred to the biohybrid artificial lung prototype and left in static culture for 1 h. Rotation was initiated at 20 rpm and increased in increments of 30–50 rpm every 2–10 h (overnight) until the desired speed (250–1,500 rpm) was achieved and maintained for 12 h. This strategy resulted in BAEC adherence at physiologic outer fiber wall shear rates tested (up to 26 dyn/ cm2 corresponding to rotation at 1,500 rpm). Because the wall shear stress in each layer was expected to be both a function of distance from the core, as well as the more complex flow phenomenon resulting from fluid moving through a porous medium, each layer of the fiber bundle was analyzed separately.

Medium was exchanged daily through ports in the device. At the end of each experiment, the rotation speed was decreased (50–200 rpm/h depending on final rotational speed), and the MHF bundle removed, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. The BAECs were permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS and labeled with rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, 1:250) and DRAQ5 (Biostatus Limited, Leicestershire, United Kingdom, 1:2,000) for 1 h to label F-actin and nuclei, respectively. The samples were visualized with confocal microscopy (Fluoview 1000, Olympus, Center Valley, CA) and image stacks reconstructed with MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Oxygen Transport to Blood in the Biohybrid Artificial Lung Prototype

To determine potential gas transport limitations by the presence of BAECs as well as assess the effect of hyperoxia on BAEC biocompatibility, 95% O2 and 5% CO2 was passed through the lumen of the fiber bundle at 0.05 L/min for 24 h following attainment of the desired rotation speed (250 or 750 rpm). The O2/CO2 gas mixture was briefly turned off as heparinized bovine blood (1 U/mL heparin) was flushed through the rotating system to replace the culture media. The gas flow was restored, and 0.4mL blood samples were collected in gas tight syringes (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, 81320) at 1, 3, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, and 60 min to measure pO2 (ABL5, Radiometer Copenhagen, n = 3 for each speed). Non-endothelialized, unmodified PMP MHF bundles rotated at the target speed of 250 or 750 rpm served as controls.

Biocompatibility of Endothelialized MHF Bundles Following Hyperoxia and Blood Exposure

Following blood incubation MHF bundles were removed, rinsed in PBS with heparin (10 U/mL), and cut lengthwise for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging and flow cytometric evaluation. For SEM imaging, the bundle was fixed in 2.5% gluteraldehyde for 1 h. Samples were then placed in 1% OsO4 (Sigma) for 1 h and washed in PBS followed by graded alcohol dehydration and critical point drying using an Emscope CPD 750 (Emscope Lab, Ashford, United Kingdom). Samples were sputter coated with a 2nm layer of gold–palladium (Cressington 108 sputter coater, Cressington, Watford, United Kingdom) and visualized with a JEM-6335F field emission gun SEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

For flow cytometry, HEPES-buffered saline, trypsin/ EDTA, and trypsin neutralizing solution (Cambrex) were used to remove the BAECs from the fiber bundle. The BAECs were labeled with 0.1 mg/100 µL anti-human p-selectin (Takara BIO, Shiga, Japan) or mouse IgG1 isotype control (Caltag Laboratories, Bangkok, Thailand) for 20 min. The labeled BAECs were centrifuged at 220g and incubated with 1.5mg/mL goat-anti-mouse IgG (Pierce, Rockford, IL) FITC for 20 min, washed, and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for flow cytometric evaluation (FACScan, Becton Dickinson). The p-selectin antibody used has previously been shown by our group to be cross-reactive to bovine activated platelets. However, to verify the adequacy of our approach to use it as a marker for “activated” or inflamed BAECs, we performed flow cytometry on BAECs maintained in static culture in tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) flasks and incubated with inflammatory stimulators tissue necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) or interleukin-1 beta (IL-β) or a vehicle control.

Statistics

All results are displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean. For BAEC growth and thrombotic deposition, repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s testing was used to compare surface modifications and time points, respectively. To evaluate pO2 levels and flow cytometry results, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s testing was used to compare different test conditions (e.g., speed of rotation, normoxia, and hyperoxia). Significance was defined at P<0.05.

Results

Surface Modification of MHF Patches and Endothelialization of Fiber Bundles

To encourage BAEC attachment, various surface modification techniques, including RFGD with or without additional protein adsorption (collagen, gelatin, or fibronectin), were evaluated. BAEC coverage increased significantly with time and varied with surface modification (P<0.001). RFGD+fibronectin and RFGD+gelatin resulted in the highest level of BAEC coverage onto MHF patches over time (P<0.001). By day 7 of culture, levels approaching near BAEC confluence were achieved on PMP MHFs treated with RFGD+gelatin (70 ± 9.8%) and RFGD+fibronectin (84 ± 18%) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Bovine aortic endothelial cell coverage on surface modified MHF patches increased significantly with culture time (P<0.05): *P<0.05 compared to RFGD+fibronectin, †P<0.05 compared to RFGD+gelatin.

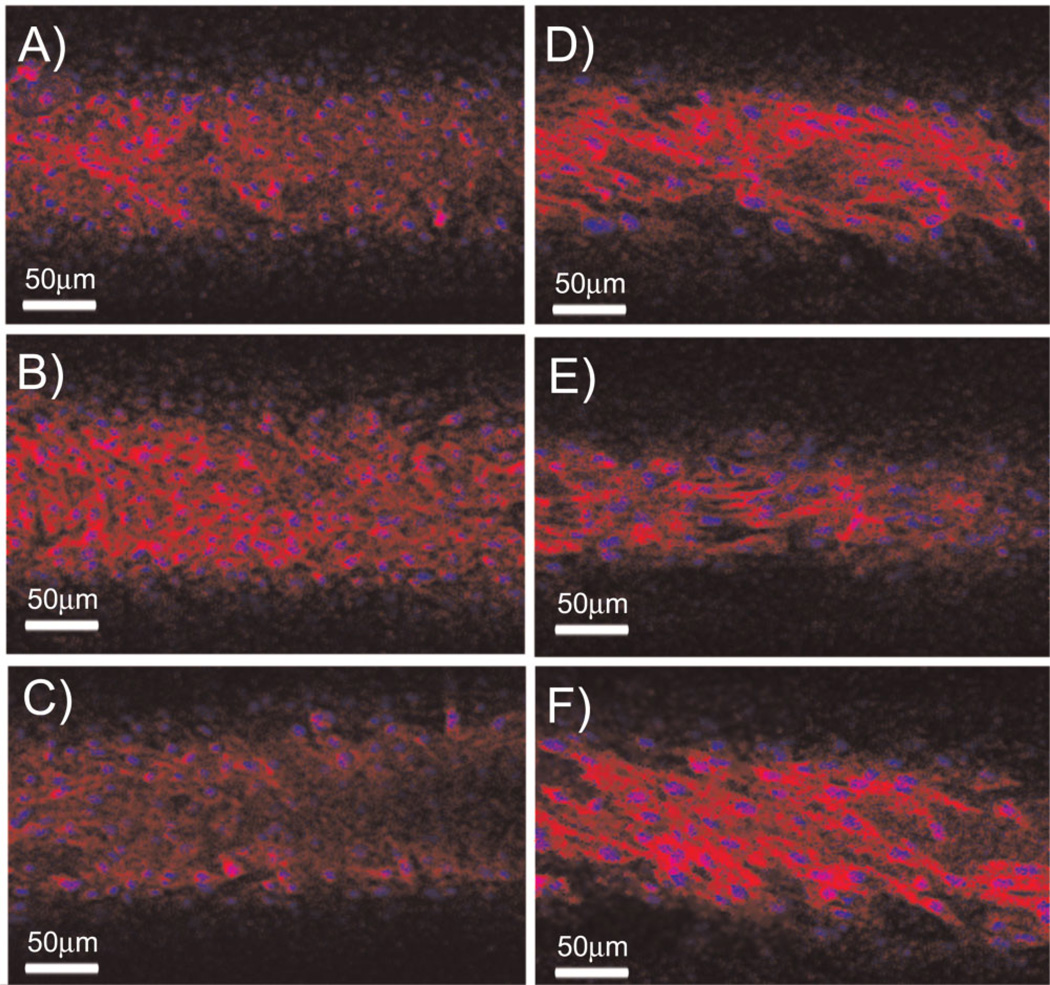

BAEC confluence on MHF bundles treated with RFGD+fibronectin was achieved within 1 week of culture. Dynamic culture of 12–24 h using the hematology rocker, followed by static culture, was required for cell adherence and growth. Confluence could not be achieved without a static period of culture. BAEC coverage is shown on MHFs prior to rotation in Figure 3A–C using fluorescent labeling with rhodamine–phalloidin and DRAQ5.

Figure 3.

Endothelialized microporous hollow fiber bundles labeled with DRAQ5 and rhodamine–phalloidin, (A and D) inner fiber layer (B and E) middle fiber layer (C and F) outer fiber layer with no rotation (A–C) or rotated at 250 rpm (D–F).

BAECs rotated at speeds up to 1,500 rpm appeared morphologically different from statically cultured BAECs in the MHF bundle (Fig. 3D–F). Rotated BAECs were qualitatively fewer in number, with a larger, more spread cell body consistent with cultured BAECs following exposure to shear stress (Levesque and Nerem, 1985). Spatially uniform BAEC coverage was qualitatively found throughout the top, middle, and bottom layers of MHF bundles. Although the BAEC density varied across the MHF bundle, it did not appear to be related to the bundle rotation speed. The only effect noted with bundle rotation speed was that BAECs on the outer fibers appeared to become more spread and aligned parallel to the direction of fiber rotation as the rotation rate increased (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Outer layer of endothelialized microporous hollow fiber bundles labeled with DRAQ5 and rhodamine–phalloidin tend to increasingly align with rotational speed: (A) 500 rpm, (B) 750 rpm, (C) 1,000 rpm, and (D) 1,500 rpm.

Blood Biocompatibility of Endothelialized MHF Patches

Thrombotic deposition on PMP fiber patches was diminished with BAEC culture time (P<0.001) (Fig. 5). The lowest deposition was observed with RFGD+fibronectin adsorption and 5 days of culture, as evidenced by the lack of thrombotic deposition in the light microscopy image (Fig. 5C), compared with a non-modified MHF patch (Fig. 5B). MHF patches treated with RFGD+collagen, on the other hand, had significantly more thrombotic deposition than RFGD, RFGD+gelatin, and RFGD+fibronectin treated MHF patches across time (P<0.05).

Figure 5.

A: Thrombotic deposition on endothelialized MHF patches of varying surface modifications at days 1–7 of BAEC growth (N=20 at each time point; N=2 for untreated, no EC control). Deposition significantly decreased with BAEC culture time (note that the untreated no EC control experienced no culture time). *P<0.05 compared to RFGD+collagen; †P< 0.05 compared with RFGD+fibronectin. B: Non-modified, non-endothelialized MHF patch; (C) non-modified, endothelialized MHF patch (5 days of culture) covered with thrombotic deposition, (D) RFGD+fibronectin endothelialized MHF patch (5 days of culture) with minimal thrombotic deposition.

Oxygen Transport to Blood in the Biohybrid Artificial Lung Prototype

Oxygen transport in the blood for MHF bundles with or without BAECs rotated at 250 and 750 rpm is plotted in Figure 6. MHF bundles rotated at 750 rpm, with both endothelialized and control fibers, increased blood pO2 levels more quickly than MHF bundles rotated at 250 rpm (P<0.05). At 250 rpm, there was no difference in pO2 between endothelialized and control MHF bundles at any time point. However, at 750 rpm non-endothelialized MHF bundles increased blood pO2 more quickly than endothelialized MHF bundles for the first 3 min (P<0.05), and were statistically equivalent thereafter.

Figure 6.

Oxygen buildup curves in blood. *P<0.05 compared to BAEC coated fibers rotating at 750 rpm. Fibers rotated at 750 rpm increased O2 content more quickly than fibers rotated at 250 rpm, regardless of the presence of BAECs.

Biocompatibility of Endothelialized MHF Bundles Following Hyperoxia and Blood Exposure

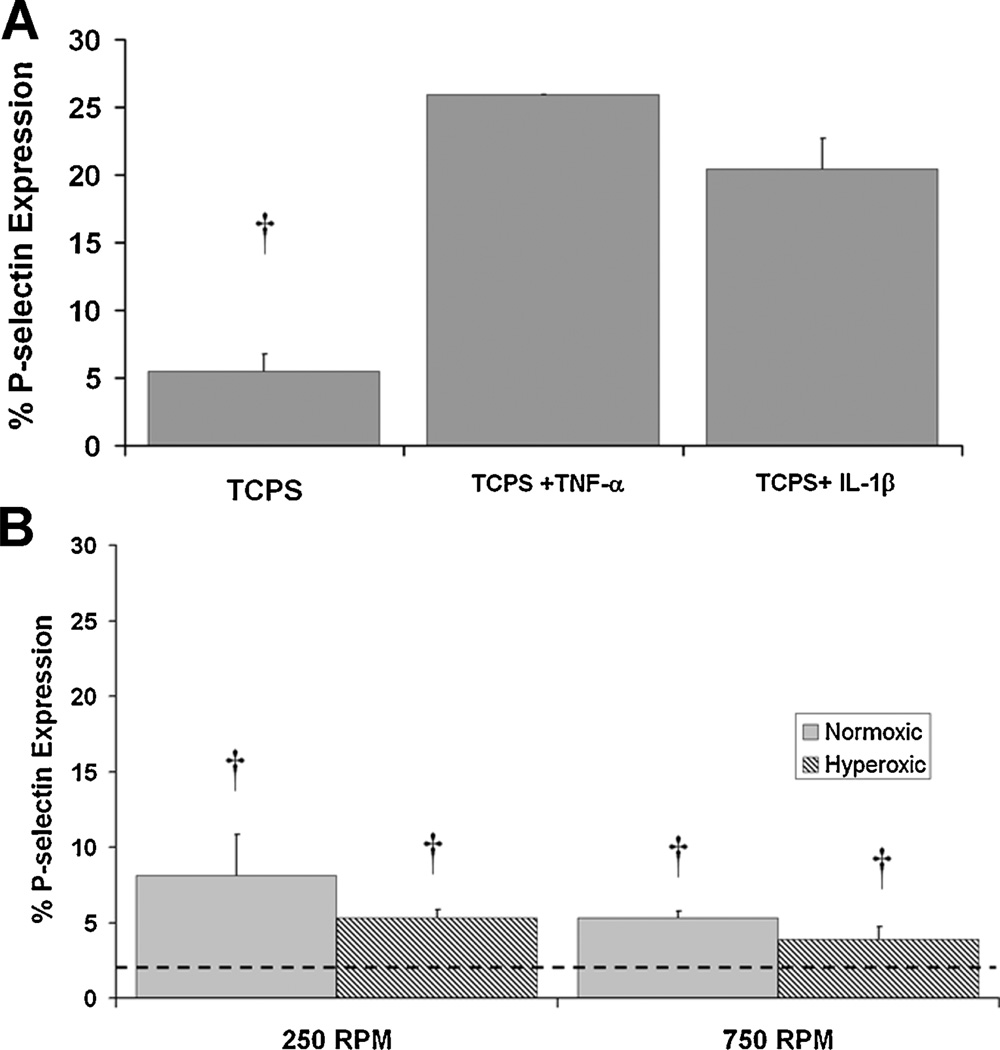

A key determinant as to whether an endothelialized surface is non-thrombogenic is the EC phenotype. As shown in Figure 7A, BAECs maintained in static culture in TCPS flasks and incubated with inflammatory stimulators produced an increase in the percent BAECs expressing p-selectin from 5% for vehicle control to >20% with stimulation. We did not attempt to further optimize this confirmatory test, but proceeded to rotational studies.

Figure 7.

A: P-selectin expression in control BAECs from tissue culture flasks with and without stimulation by TNF-α or IL-1β. B: P-selectin expression on BAECs from endothelialized MHF bundles surface modified with RFGD+fibronectin adsorption, following rotation in bovine blood at normoxic and hyperoxic conditions at rotation speeds of 250 and 750 rpm. The dashed line denotes the cutoff point for the isotype control in the flow cytometry analysis. †P<0.05 versus TNF-α and IL-1β stimulation.

P-selectin expression on BAECs from MHF bundles surface modified with RFGD and coated with adsorbed fibronectin rotated at 250 and 750 rpm was significantly lower than with BAECs in static culture exposed to inflammatory agonists; however, there was no difference with BAECs from static culture exposed to a vehicle control. There was a trend toward reduced p-selectin expression in BAECs under rotation under hyperoxic conditions versus normoxic conditions, but the difference was not significant under the conditions tested. Electron micrographs of thrombotic deposition on non-endothelialized/non-surface modified MHF bundles exposed to hyperoxia and endothelialized/surface modified MHF bundles exposed to hyperoxia, all rotated at 250 or 750 rpm are shown in Figures 8 and 9, respectively. SEM was used to qualitatively analyze thrombotic deposition, which was not readily visible and precluded the use of the quantification technique utilized for the MHF patches to determine a suitable coating. On the inner fiber layer (panels A and D) thrombotic deposition was found to be comparable between the groups. On the middle (panels B and E) and outer fiber layer (panels C and F) endothelialized MHFs appeared to experience equivalent or less thrombotic deposition than non-endothelialized MHFs. These trends qualitatively appear to be similar for both rotational speeds tested.

Figure 8.

SEMs of MHF modules rotated at 250 rpm exposed to bovine blood. Images progress from inner to outer layer from top to bottom: (A–C) control without surface modification or endothelialization, with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (inner, middle, outer MHF layer), (D–F) surface modified with RFGD+fibronectin and endothelialization, with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. White arrowheads indicate thrombus deposition and the white arrows indicate red blood cells.

Figure 9.

SEMs of MHF modules rotated at 750 rpm exposed to bovine blood. Images progress from inner to outer layer from top to bottom: (A–C) control without surface modification or endothelialization, with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (inner, middle, outer MHF layer), (D–F) surface modified with RFGD+fibronectin adsorption endothelialization, with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. White arrowheads indicate thrombus deposition.

Discussion

A biohybrid artificial lung prototype was designed and constructed to employ rotating endothelialized MHF bundles to improve biocompatibility and gas transfer performance. Key features of this modular design included exchangeable MHF bundles, controlled bundle rotation, separation of the gas–liquid interface, and the ability to sample and exchange medium. Pilot studies on MHF patches demonstrated BAEC attachment and confluence was obtained more quickly through surface modification with RFGD and fibronectin or gelatin adsorption. These surface treatments provided an effective means to quickly enhance cell attachment and growth and have been shown to heighten cell retention (Mathur et al., 2003; Pratt et al., 1988; Takagi et al., 2003). Although we examined EC growth over a 7-day period on these surfaces, confluence might be achieved more rapidly by a higher cell seeding density. This approach might be feasible in a clinical application, where a preparation period < 1 week would be desirable.

Both the type of surface modification and the amount of EC coverage directly influenced thrombotic deposition on MHF patches. At low levels of BAEC coverage, roughly 10% or less, thrombotic deposition was relatively high for all surface types, and deposition diminished with increased BAEC coverage, in the range of 22–84%. MHF pretreatment with RFGD and collagen adsorption was a notable exception, resulting in significantly higher thrombotic deposition than all groups except the untreated endothelialized fibers as well as the untreated controls that contained no ECs. This was not unanticipated, considering that type I collagen is a known platelet agonist (Fuglsang et al., 2002). RFGD with fibronectin or RFGD with gelatin treatment appeared to be the two most attractive surfaces since they supported the best EC growth, and both had superior thromboresistance compared to unmodified fibers. The use of fibronectin as a growth promoting surface for endothelialization of PMP fibers has previously been shown to reduce concentrations of inflammatory molecules in a rat cardiopulmonary bypass model (Takagi et al., 2003). While fibronectin and gelatin may be relatively attractive compared to type I collagen to promote EC adhesion, ideally a protein that did not support platelet adhesion or act as a platelet agonist would be utilized. Examples of such agents would include the REDV peptide (Massia and Hubbell, 1992), elastic gelatin (Kanayama et al., 2008; Nagai et al., 2008), or a combination of r-hirudin and fibronectin (Kong et al., 2002).

We anticipated that gas transfer across an endothelialized MHF might be slightly decreased due to the additional thickness of the EC layer. Although BAECs are quite permeable (Dumas et al., 1999; Randall et al., 1997), they share a similar thickness (0.2–0.4 µm) to synthetic coatings, such as siloxane, which have demonstrated decreased mass transfer (Eash et al., 2004; Kanamori et al., 2000; Niimi et al., 1997). In order to improve mass transfer in the biohybrid artificial lung, the fiber bundles were rotated to provide more efficient mixing. Other gas exchange devices such as the Hemolung™ (Eash et al., 2007; Svitek et al., 2005), the chronic artificial lung (Borovetz et al., 1997; Wu et al., 2005), and a pediatric pump-oxygenator (Fill et al., 2008; Pantalos et al., 2009) have been designed to augment gas exchange by inducing fiber bundle rotation at a set fluid flow rate. By disturbing the boundary layer and increasing local advection, the blood flow rate across these types of devices with smaller fiber surface areas can be maintained at low levels and still provide clinically significant CO2 removal, a major focus of chronic support devices for disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema (Pesenti et al., 2009). This appears to also hold true for our biohybrid artificial lung prototype, as demonstrated in Figure 6. Our assessment of oxygen transfer from endothelialized versus control hollow fibers was based on an unsteady state experiment in which the fiber modules where within a closed system. In this experiment, the pO2 within the liquid medium surrounding the fibers would always reach the same level (approximately equal to the pO2 in the gas flowing through the fibers), but the rate of increase in pO2 would be affected by the rotation rate of the fibers and any transport resistance afforded by the endothelial layer. At lower rotation rates, when the overall rate of mass transfer is lower and closer to that of passive oxygenators, the ECs negligibly affect the rate of oxygen transfer. At higher rotation rates, however, when active mixing enhances mass transfer, the ECs did reduce the rate of oxygen transfer, but this could be compensated by increasing the overall fiber surface area. This will be an important area of design optimization where tradeoffs in size and portability will occur with increasing surface area. However, more work is necessary to determine the effects of design parameters such as fiber spacing and layout, as well as overall device design and operational parameters on gas transfer.

As a consequence of the fiber rotation, the amount of shear stress that BAECs could tolerate in the device was examined. Near EC confluence was maintained at 1,500 rpm. The shear rate for the outer layer of fibers in a MHF bundle rotating at the highest level of bundle rotation examined (1,500 rpm), provided approximately 26 dyn/cm2 wall shear stress for outer fiber surfaces. Numerous studies have documented that ECs align, flatten, and remodel under shear stress through cytoskeletal rearrangement to spread the stress over greater surface area as well as increase substratum adherence through focal contacts (Ballermann et al., 1998; Chien, 2008; Nerem et al., 1998; Paszkowiak and Dardik, 2003; Reneman et al., 2006). This response depends on both magnitude and flow pattern (Lin et al., 2000). In addition, cell function, morphology, and gene expression are also altered with fluid shear (Ueda et al., 2004). In the biohybrid lung, alignment frequently appeared perpendicular to the rotational direction in the inner portions of the MHF bundle, and was more parallel in the outer portions, especially at higher rpm. This may be a function of complex flow around the inner portions of the MHF bundle, while the outer portion experienced more predictable cross-fiber flow.

The expression of p-selectin, a marker of EC inflammation (Blann et al., 2003), on ECs throughout the bundle following exposure to bovine blood was no greater than ECs in standard tissue culture. In fact, there appeared to be a trend of decreasing p-selectin with increased fiber rotation, which is in agreement with the protective role of physiologic shear stress on ECs (Lin et al., 2000; Ni et al., 2003). P-selectin expression has previously been evaluated as a marker for platelet activation in other artificial lung devices (Cook et al., 2002). While the shear in the outer portions of the fiber bundles is higher than that recommended by Cook et al. for maintaining low p-selectin expression (11.6 dyn/cm2) by platelets, we did not find significant increases in p-selectin by ECs on the fiber bundles. However, this may also be a function of the original source of the ECs. It is well documented that ECs from different vascular beds behave differently upon exposure to shear stress (Resnick et al., 2003), and this may need further consideration and evaluation for determining the EC harvest site. It is also likely that the shear within the middle and inner layers of the MHF bundles was below 12 dyn/cm2, reducing the overall percent of BAECs expressing p-selectin. P-selectin expression demonstrated a non-significant correlation with oxygen tension; however, more experiments would be required to establish the significance of the effect of oxygen concentration on BAECs. A low level of inflammation may be tolerable provided ECs maintain a phenotype that does not switch toward pro-thrombotic, as would be the case in a marked inflammatory state. Gene transfection for proteins such as IL-10, have been utilized in other endothelialized oxygenators and shown great promise as anti-inflammatory surfaces (Ohata et al., 1998; Sawa et al., 2000). Such techniques could potentially be applied to this biohybrid artificial lung, although this approach may extend the period between cell isolation and support of the patient.

Thrombotic deposition following exposure to bovine blood with fiber bundle rotation and high oxygen tension was also evaluated by electron microscopy. At both rotational speeds, 250 and 750 rpm, thrombotic deposition on endothelialized MHF bundles appeared to be equivalent or less than thrombotic deposition on non-endothelialized MHF bundles. Hyperoxic conditions at both speeds further seem to have diminished thrombotic deposition, providing further evidence that the biohybrid artificial lung may provide superior biocompatibility in an in vivo setting.

Although the idea of incorporating ECs in blood-contacting surfaces to improve biocompatibility has been around for several decades (Hirko et al., 1987; Lindblad et al., 1986), the application of this approach to oxygenator technology is relatively new and underdeveloped. To our knowledge, two other studies have attempted to incorporate ECs onto MHFs for improved biocompatibility. Both incorporated ECs onto a standard MHF oxygenator for reducing inflammation from bypass surgery. The approaches included transfection of ECs with IL-10 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (Ohata et al., 1998) and modification of the fiber surface to promote EC attachment (Takagi et al., 2003). The results of the modification experiments by Takagi et al. concurred with our finding that fibronectin coating enhanced EC attachment. While these two studies demonstrated a reduction in systemic inflammatory markers (TNF-α) and increases in anti-inflammatory molecules (NO and IL-10) in vivo, the issue of biocompatibility was not addressed. The biohybrid artificial lung developed in this article combines the biocompatibility advantage potentially provided by EC seeding with the enhanced transport capability of a rotating fiber bundle. We demonstrate that ECs were associated with improved biocompatibility (as indicated by qualitative and quantitative analysis of thrombus deposition and p-selectin expression) and do not appear to substantially impede oxygen transfer. These results in conjunction with the potential benefits of systemic reduction of inflammation (Ohata et al., 1998; Takagi et al., 2003) provide impetus for further studies based on our technology. These previous studies were conducted with conventional oxygenator designs and static conditions; whereas, the rotating fiber bundle we developed permits a reduction in the MHF surface area required to achieve sufficient gas exchange to support an adult human. Thus, the combination of improved biocompatibility, reduced fiber surface area, and enhanced gas exchange characteristics could lead to a substantially improved gas exchange device for the treatment of acute lung failure.

Several limitations of this study are worth noting. More comprehensive characterization of EC phenotype in response to conditions imposed by the device, using parameters in addition to p-selectin would permit a more conclusive evaluation of the status of the ECs and their antithrombotic potential. Although we were able to quantify thrombotic deposition in the MHF patches, we were only able to do this in a qualitative manner for the rotated fiber bundles using electron microscopy due to less acute thrombus deposition with fiber rotation and higher anticoagulation levels. A more quantitative and expanded analysis would be warranted for a more complete understanding of fiber biocompatibility. Further investigation of spatial distribution of EC phenotype, computational fluid dynamic based optimization of flow patterns within the biohybrid artificial lung, and other refinements (fiber spacing, fiber layering, fiber orientation, etc.) would be useful for scaling the prototype to the appropriate size for use in a large animal model. In a refined and scaled-up version of this prototype, patient ECs would be harvested and cultured on the MHF bundle prior to connection with the device. A suitable source of ECs may be microvascular ECs from adipose tissue but their response to the flow fields in the device may be different than those seen in the BAECs in this study. A larger harvest of ECs would reduce the time to confluence by increasing the seeding density, which would be attractive for more rapid deployment, although advances in cell and genetic engineering may soon permit development of a ubiquitous non-autologous cell source. Finally, quantitative mass transfer studies would beneficial to determine whether CO2 clearance rates are at an adequate level for the treatment of ARDS patients.

Conclusions

A biohybrid artificial lung prototype was developed to support rotation of an endothelialized MHF bundle perfused with oxygen. MHFs were surface modified to support EC attachment and growth for improved surface–blood contact within the device. Surface modification of MHFs with RFGD+gelatin and RFGD+fibronectin adsorption increased EC adherence and growth, as well as reduced thrombotic deposition. Oxygen transfer increased with rotation speed, and was affected by the presence of the ECs at the higher rotation speed when active mixing appears to be playing a larger role in the overall mass transfer. An increase in surface area may compensate for this effect, but more work is necessary to determine whether other design parameters may provide a better route for optimization. Thrombotic deposition on endothelialized MHF bundles exposed to 95% hyperoxia was equivalent to or less than thrombotic deposition on non-endothelialized MHF bundles. This data in combination with low levels of p-selectin expression from BAECs support the feasibility of oxygenation of a biohybrid lung for advanced respiratory conditions, such as ARDS.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of Michael Audette, Bradley Lomago, Brian Frankowski, and the McGowan Center for Preclinical Studies, as well as Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for funding.

References

- Ballermann BJ, Dardik A, Eng E, Liu A. Shear stress and the endothelium. Kidney Int. 1998;(Suppl 67):S100–S108. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry BE, Crapo JD. Patterns of accumulation of platelets and neutrophils in rat lungs during exposure to 100% and 85% oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132(3):548–555. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blann AD, Nadar SK, Lip GY. The adhesion molecule P-selectin and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(24):2166–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovetz HS, Gartner MJ, Litwak P, Reeder GD University of Pittsburgh, assignee. Membrane Apparatus with Enhanced Mass Transfer and Pumping Capabilities Via Active Mixing. 6,106,776. USA patent. 1997 Apr 11;

- Budilarto SG, Frankowski BJ, Hattler BG, Federspiel WJ. Flow visualization study of a pulsating respiratory assist catheter. ASAIO J. 2005;51(6):673–680. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000187393.79866.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on endothelial cells. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36(4):554–562. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman RW. Hemostatic complications of cardiopulmonary bypass. Am J Hematol. 1995;48(4):267–272. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830480412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KE, Maxhimer J, Leonard DJ, Mavroudis C, Backer CL, Mockros LF. Platelet and leukocyte activation and design consequences for thoracic artificial lungs. ASAIO J. 2002;48(6):620–630. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas D, Latger V, Viriot ML, Blondel W, Stoltz JF. Membrane fluidity and oxygen diffusion in cholesterol-enriched endothelial cells. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 1999;21(3–4):255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eash HJ, Jones HM, Hattler BG, Federspiel WJ. Evaluation of plasma resistant hollow fiber membranes for artificial lungs. ASAIO J. 2004;50(5):491–497. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000138078.04558.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eash HJ, Frankowski BJ, Hattler BG, Federspiel WJ. Evaluation of local gas exchange in a pulsating respiratory support catheter. ASAIO J. 2005;51(2):152–157. doi: 10.1097/01.MAT.0000153648.11692.D0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eash HJ, Budilarto SG, Hattler BG, Federspiel WJ. Investigating the effects of random balloon pulsation on gas exchange in a respiratory assist catheter. ASAIO J. 2006;52(2):192–195. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000199752.89066.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eash HJ, Mihelc KM, Frankowski BJ, Hattler BG, Federspiel WJ. Evaluation of fiber bundle rotation for enhancing gas exchange in a respiratory assist catheter. ASAIO J. 2007;53(3):368–373. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318031af3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fill B, Gartner M, Johnson G, Horner M, Ma J. Computational fluid flow and mass transfer of a functionally integrated pediatric pump-oxygenator configuration. ASAIO J. 2008;54(2):214–219. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3181648d80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglsang J, Stender M, Zhou J, Moller J, Falk E, Ravn HB. Platelet activity and in vivo arterial thrombus formation in rats with mild hyperhomocysteinaemia. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2002;13(8):683–689. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go T, Macchiarini P. Artificial lung: Current perspectives. Minerva Chir. 2008;63(5):363–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalvo R, Marti-Sistac O, Blanch L, Lopez-Aguilar J. Bench-to-bedside review: Brain-lung interaction in the critically ill—A pending issue revisited. Crit Care. 2007;11(3):216. doi: 10.1186/cc5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirko MK, Schmidt SP, Hunter TJ, Evancho MM, Sharp WV, Donovan DL. Endothelial cell seeding improves 4mm PTFE vascular graft performance in antiplatelet medicated dogs. Artery. 1987;14(3):137–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Pope D, Orme JF, Bigler ED, Larson LV. Neuropsychological sequelae and impaired health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(1):50–56. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9708059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori T, Niwa M, Kawakami H, Mori Y, Nagaoka S, Haraya K, Shinbo T. Estimate of gas transfer rates of an intravascular membrane oxygenator. ASAIO J. 2000;46(5):612–619. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200009000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama T, Nagai N, Mori K, Munekata M. Application of elastic salmon collagen gel to uniaxial stretching culture of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2008;105(5):554–557. doi: 10.1263/jbb.105.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazzaz JA, Xu J, Palaia TA, Mantell L, Fein AM, Horowitz S. Cellular oxygen toxicity. Oxidant injury without apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(25):15182–15186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshbin E, Westrope C, Pooboni S, Machin D, Killer H, Peek GJ, Sosnowski AW, Firmin RK. Performance of polymethyl pentene oxygenators for neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A comparison with silicone membrane oxygenators. Perfusion. 2005;20(3):129–134. doi: 10.1191/0267659105pf797oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko WJ, Hsu HH, Tsai PR. Prolonged extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105(5):422–426. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollef MH, Schuster DP. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(1):27–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501053320106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Grabitz RG, van Oeveren W, Klee D, van Kooten TG, Freudenthal F, Qing M, von Bernuth G, Seghaye MC. Effect of biologically active coating on biocompatibility of Nitinol devices designed for the closure of intra-atrial communications. Biomaterials. 2002;23(8):1775–1783. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DS, Holt D. Insensible water loss from the Jostra Quadrox D oxygenator: An in vitro study. Perfusion. 2007;22(6):407–410. doi: 10.1177/0267659108091337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaver SK, Evans TW. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ. 2007;335(7616):389–394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39293.624699.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque MJ, Nerem RM. The elongation and orientation of cultured endothelial cells in response to shear stress. J Biomech Eng. 1985;107(4):341–347. doi: 10.1115/1.3138567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Hsu PP, Chen BP, Yuan S, Usami S, Shyy JY, Li YS, Chien S. Molecular mechanism of endothelial growth arrest by laminar shear stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(17):9385–9389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170282597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblad B, Burkel WE, Wakefield TW, Graham LM, Stanley JC. Endothelial cell seeding efficiency onto expanded polytetrafluorethy-lene grafts with different coatings. Acta Chir Scand. 1986;152:653–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund LW, Hattler BG, Federspiel WJ. Is condensation the cause of plasma leakage in microporous hollow fiber membrane oxygenators. J Membr Sci. 1998;147:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Massia SP, Hubbell JA. Vascular endothelial cell adhesion and spreading promoted by the peptide REDV of the IIICS region of plasma fibronectin is mediated by integrin alpha 4 beta 1. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(20):14019–14026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur AB, Truskey GA, Reichert WM. Synergistic effect of high-affinity binding and flow preconditioning on endothelial cell adhesion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;64(1):155–163. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller XM, Jegger D, Augstburger M, Horisberger J, Godar G, von Segesser LK. A new concept of integrated cardiopulmonary bypass circuit. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21(5):840–846. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai N, Kubota R, Okahashi R, Munekata M. Blood compatibility evaluation of elastic gelatin gel from salmon collagen. J Biosci Bioeng. 2008;106(4):412–415. doi: 10.1263/jbb.106.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasu M, Miyamura K, Shikano K. Evaluation of membrane oxygenator during long term ECMO: Silicone hollow fiber and polypropylene hollow fiber membrane oxygenator. Jpn J Artif Organs. 1984;13:586–588. [Google Scholar]

- Nerem RM, Alexander RW, Chappell DC, Medford RM, Varner SE, Taylor WR. The study of the influence of flow on vascular endothelial biology. Am J Med Sci. 1998;316(3):169–175. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni CW, Hsieh HJ, Chao YJ, Wang DL. Shear flow attenuates serum-induced STAT3 activation in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(22):19702–19708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niimi Y, Ueyama K, Yamaji K, Yamane S, Tayama E, Sueoka A, Kuwana K, Tahara K, Nose Y. Effects of ultrathin silicone coating of porous membrane on gas transfer and hemolytic performance. Artif Organs. 1997;21(10):1082–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1997.tb00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notler RH, Finkelstein JN, Holm BA. Lung injury mechanisms, pathophysiology and therapy. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis Group; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ohata T, Sawa Y, Takagi M, Inoue T, Yoshida T, Kogaki S, Matsuda H. Hybrid artificial lung with interleukin-10 and endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase gene transfected endothelial cells attenuates inflammatory reactions induced by cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation. 1998;98(19):II269–II274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantalos GM, Horrell T, Merkley T, Sahetya S, Speakman J, Johnson G, Gartner M. In vitro characterization and performance testing of the ension pediatric cardiopulmonary assist system. ASAIO J. 2009;55(3):282–286. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3181909d76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszkowiak JJ, Dardik A. Arterial wall shear stress: Observations from the bench to the bedside. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2003;37(1):47–57. doi: 10.1177/153857440303700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek GJ, Clemens F, Elbourne D, Firmin R, Hardy P, Hibbert C, Killer H, Mugford M, Thalanany M, Tiruvoipati R, Truesdale A, Wilson A. CESAR: Conventional ventilatory support vs. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:163. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesenti A, Zanella A, Patroniti N. Extracorporeal gas exchange. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15(1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283220e1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter JV, John P, Graham PL, Moran JL, George IA, Bersten A. Corticosteroids in the prevention and treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in adults: Meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7651):1006–1009. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39537.939039.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt KJ, Jarrell BE, Williams SK, Carabasi RA, Rupnick MA, Hubbard FA. Kinetics of endothelial cell-surface attachment forces. J Vasc Surg. 1988;7(4):591–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall D, Burggren W, French K, Eckert R. Eckert animal physiology mechanisms and adaptations. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reneman RS, Arts T, Hoeks AP. Wall shear stress—An important determinant of endothelial cell function and structure—In the arterial system in vivo. Discrepancies with theory. J Vasc Res. 2006;43(3):251–269. doi: 10.1159/000091648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick N, Yahav H, Shay-Salit A, Shushy M, Schubert S, Zilberman LC, Wofovitz E. Fluid shear stress and the vascular endothelium: For better and for worse. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;81(3):177–199. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(02)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffini E, Parola A, Papalia E, Filosso PL, Mancuso M, Oliaro A, Actis-Dato G, Maggi G. Frequency and mortality of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome after pulmonary resection for bronchogenic carcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20(1):30–36. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00760-6. discussion 36-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Hall CM, Lafayette NG, Pohlmann JR, Padiyar N, Toomasian JM, Haft JW, Cook KE. Thirty-day in-parallel artificial lung testing in sheep. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84(4):1136–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa Y, Ohata T, Takagi M, Matsuda H. Hybrid artificial lung: Current status and perspective. Jpn J Artif Organs. 1998;27(5):765–768. [Google Scholar]

- Sawa Y, Ohata T, Takagi M, Suhara H, Matsuda H. Development of hybrid artificial lung with gene transfected biological cells. J Artif Organs. 2000;3(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SW, Yano Y, Sumpio BE, Jena BP, Geibel JP, Gekle M, Ober-leithner H. Rapid aldosterone-induced cell volume increase of endothelial cells measured by the atomic force microscope. Cell Biol Int. 1997;21(11):759–768. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1997.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitek RG, Frankowski BJ, Federspiel WJ. Evaluation of a pumping assist lung that uses a rotating fiber bundle. ASAIO J. 2005;51(6):773–780. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000178970.00971.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Shiwaku K, Inoue T, Shirakawa Y, Sawa Y, Matsuda H, Yoshida T. Hydrodynamically stable adhesion of endothelial cells onto a polypropylene hollow fiber membrane by modification with adhesive protein. J Artif Organs. 2003;6(3):222–226. doi: 10.1007/s10047-003-0218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomasian JM, Schreiner RJ, Meyer DE, Schmidt ME, Hagan SE, Griffith GW, Bartlett RH, Cook KE. A polymethylpentene fiber gas exchanger for long-term extracorporeal life support. ASAIO J. 2005;51(4):390–397. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000169111.66328.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda A, Koga M, Ikeda M, Kudo S, Tanishita K. Effect of shear stress on microvessel network formation of endothelial cells with in vitro three-dimensional model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287(3):H994–H1002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00400.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson SP. Platelet activation by extracellular matrix proteins in haemostasis and thrombosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(12):1358–1372. doi: 10.2174/138161209787846702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welty SE, Rivera JL, Elliston JF, Smith CV, Zeb T, Ballantyne CM, Montgomery CA, Hansen TN. Increases in lung tissue expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 are associated with hyperoxic lung injury and inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;9(4):393–400. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/9.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZJ, Gartner M, Litwak KN, Griffith BP. Progress toward an ambulatory pump-lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(4):973–978. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Cheng G, Koert A, Zhang J, Gellman B, Yankey GK, Satpute A, Dasse KA, Gilbert RJ, Griffith BP, Wu ZJ. Functional and biocompatibility performances of an integrated Maglev pump-oxygenator. Artif Organs. 2009;33(1):36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2008.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwischenberger JB, Alpard SK. Artificial lungs: A new inspiration. Perfusion. 2002;17(4):253–268. doi: 10.1191/0267659102pf586oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]