Abstract

Vasculogenesis/angiogenesis is one of the earliest processes that occurs during embryogenesis. ETV2 and SOX7 were previously shown to play a role in endothelial development; however, their mechanistic interaction has not been defined. In the present study, concomitant expression of Etv2 and Sox7 in endothelial progenitor cells was verified. ETV2 was shown to be a direct upstream regulator of Sox7 that binds to ETV2 binding elements in the Sox7 upstream regulatory region and activates transcription. We observed that SOX7 over-expression can mimic ETV2 and increase endothelial progenitor cells in embryonic bodies (EBs), while knockdown of Sox7 is able to block ETV2-induced increase in endothelial progenitor cell formation. Angiogenic sprouting was increased by ETV2 over-expression in EBs, and it was significantly decreased in the presence of Sox7 shRNA. Collectively, these studies support the conclusion that ETV2 directly regulates Sox7, and that ETV2 governs endothelial development by regulating transcriptional networks which include Sox7.

Introduction

Vasculogenesis is one of the earliest processes to occur during embryogenesis [1–3]. Vascular development in the murine embryo begins in the yolk sac mesoderm with the formation of blood islands and progresses with the development of primitive vascular networks by embryonic day E8.5 [4,5]. In the embryo proper at approximately E8.0, angioblasts migrate into the pericardial area and form a vascular plexus adjacent to the developing myocardium. These lineages continue to develop into the two-layered heart tube, the inner endocardium, and the outer myocardium [6–8]. The linear heart tube initiates looping morphogenesis at approximately E8.25. The beating of the heart begins at E8.5, and looping terminates with the emergence of a four-chambered structure by E10.5 [9–13]. In concert with the endocardial tube formation, angioblasts aggregate and form the dorsal aorta and cardinal veins, while other vascular plexuses develop and remodel to form the framework for fetal circulation, which is established by day E9.5 [4].

The Ets gene family was shown to have essential roles in diverse biological processes, including angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, hematopoiesis, neurogenesis, and myocardial development [14–19]. In situ hybridization and RT-PCR techniques demonstrated that Etv2 expression is restricted to the endocardium/endothelium of the E8.5 and E9.5 embryo, and that this expression is extinguished by E11.5 [14]. The Etv2 homozygous mutant embryos were lethal by E9.5, and lacked the endocardial/endothelial lineage [14]. Recent in vivo and in vitro results further support the hypothesis that ETV2 is a critical factor for the specification of the endocardial/endothelial and hematopoietic lineages [15,20–23].

The Sry-related HMG box (Sox) gene family encodes transcription factors that regulate specification and differentiation of various developmental processes. Sox7, Sox17, and Sox18 comprise the Sox-F family, which was shown to play a critical role in formation of the endodermal lineage, hematopoietic stem cell regulation, cardiovascular development, and, more recently, arterial specification [5,24–30]. All three Sox-F members were shown to be expressed in vascular endothelial cells [24,25,27,31,32]. Sox18-null mice were not viable after significant back-crossing onto a pure C57BL6 background and died at E14.5 [33]. Other reports showed that point mutations in Sox18 in both humans and mice cause syndromes with cardiovascular and hair follicle defects; however, previously generated Sox18-null mice were viable and display no obvious cardiovascular defects [34]. These results may be due to the generation of a dominant negative protein by the point mutations, while defects in the Sox18-null mice may be rescued by the compensatory action of other Sox-F members [5,27,34–36]. Previously described redundancy of Sox17 and Sox18 as well as Sox7 and Sox18 in vascular development, arterial-venous identity, and cardiovascular development further support this theory [5,27,34–36]. SOX7 was recently shown to be involved in the transcriptional regulation of the hemogenic endothelium [37], and it has been implicated in human cardiovascular development [38]. Although the downstream effects of the Sox-F family have begun to be elucidated, the upstream regulation of the Sox-F family members has yet to be defined.

In the present study, we demonstrate that ETV2 regulates the expression of Sox7 by directly binding to its upstream regulatory region. We further establish that the Etv2 developmental pathway results in the formation of endothelial progenitor cells, and it increases angiogenic potential of embryonic bodies (EBs). Collectively, these studies enhance our understanding of molecular networks that govern discrete stages of early endothelial development.

Materials and Methods

Generation of embryonic stem cell lines

Standard techniques were used for isolation and propagation of embryonic stem (ES) clones [39]. Etv2 mutant ES cells were derived from day 3 Etv2 mutant and WT blastocysts as previously described [40]. ES cells (A2loxCre) with doxycycline-inducible expression of Etv2 or Sox7-Myc were generated as previously described [41]. Briefly, the expressing vector pLox was integrated into the X chromosome of the Ainv15 ES cells placing the cDNA under the control of tetracycline-responsive element (TRE). In this system, the addition of doxycycline (dox) causes the reverse tetracycline transactivator to bind to TRE, resulting in over-expression.

EB culture and expression profiles

EBs were prepared using the hanging drop technique and the appropriate mES cell lines, and then cultured in suspension on a rotating plate beginning on day 2. Dox (1 μg/mL final concentration) was added to the culture at designated time points to induce protein expression [41]. Gene expression at each time point was analyzed using quantitative RT-PCR using 7900 Applied Biosystems sequence detection system (Foster City, CA). All Taqman gene expression assays were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Taqman gene expression assays included Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1), Etv2 (Mm 00468389_m1), Sox7 (Mm00776876_m1), Cdh5 (Mm00486938_m1), Pecam1 (Mm00476702_m1), and Tek (Mm01256904_m1).

Single-cell qRT-PCR

EBs were prepared using the hanging drop technique with control mES cells (A172lox), and then cultured in suspension on a rotating plate beginning on day 2. Day 5 EBs were harvested and dissociated as previously described [41]. Briefly, EBs were incubated in Collagenase Type I (17100-017; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and triturated multiple times over a 10 min interval. Cells were washed, filtered, and stained with anti-Flk1-PE (12-58212-83; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and anti-Cdh5-APC (17-1441-80; eBioscience). Double positive (Flk1+/Cdh5+) were sorted on an FACSAria (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Sorted cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD viability/cytotoxicity kit (L-3224; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and loaded on a 10–17 μm Auto Prep Integrated Fluidic Circuit (IFC; Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA) to capture single cells using the C1 Single cell Auto Prep System (Fluidigm).

Cells were loaded at 250,000 cells/mL according to the manufacturer's protocol. The IFC was imaged on a Nikon Tie Deconvolution microscope system to determine capture efficiency before proceeding to cDNA synthesis using the Ambion single cell to CT kit (PN 4458237; Life Technologies), and targeted amplification was performed for 18 cycles on a C1 Single Cell Auto Prep system (Fluidigm) with Taqman gene expression assays Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1), Etv2 (Mm 00468389_m1), and Sox7 (Mm00776876_m1). Fourty live cells were selected to load on a Dynamic Array IFC 48.48 chip (Fluidigm), and Etv2, Sox7, and Gapdh were quantified in quadruplicates on a Biomark HD system (Fluidigm) using Taqman Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (4352042; Applied Biosysystems, Austin, TX) according to the standard manufacturer's protocol, using the same Taqman probe used in the preamplification. The data were analyzed using Fluidigm's real-time PCR analysis software.

Protein analysis by western blot

Protein expression was determined by western blot analysis as previously described [42]. Antibodies used were anti-human Sox7 (AF2766; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), anti-PECAM-1 (M-20) (sc-1506; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-CDH5 (C-19) (sc-6458; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-SOX17 (S-20) (sc-17355; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-SOX18 (H-140) (sc-20100), anti-α-tubulin (T5168; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and anti-c-myc (Cat #11667149001; Roche, Indianapolis, IN).

Chromatin immuno-precipitation assays

EBs were prepared as described earlier using ETV2-HAX3 over-expressing cells and maintained in differentiation medium. Over-expression was induced by dox at day 3.0, and EBs were harvested at day 4.0. Chromatin DNA isolation from EBs and protein-DNA complex immuno-precipitation using anti-HA antibody (Y-11, sc-805×) or rabbit IgG as control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were performed as previously described [43]. SYBR Green qRT-PCR was performed using PCR master mix from Applied Biosystems (Cat #4309155) and primers specific to the mouse Sox7 upstream regions: Region I Fwd 5′ CGCTCCTCACCCAAATGTAT 3′, Region I Rev 5′ AAGAATGACTGGGTCAAGGAAA 3′; Region II Fwd 5′ TGAGACCTAGGGAGCTGATGC 3′, Region II Rev 5′ GTTGCTATTGGCTTGCTCCAC 3′; Region III Fwd 5′ TATCGCCGGGTTTTAGGATTA 3′, Region III Rev 5′ GCTTTAGACACACCCCACTGT 3′; Gapdh Fwd 5′ TGACGTGCCGCCTGGAGAAA 3′, and Gapdh Rev 5′ AGTGTAGCCCAAGATGCCCTTCAG 3′.

Electrophoretic mobility shift and transcriptional assays

The electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed using the Gel Shift assay Core Kit (E3050; Promega, Madison, WI). HA-tagged Etv2 protein was in vitro translated by TNT-coupled transcription rabbit reticulocyte translation system (L5010; Promega). HA-ETV2 was incubated with 32P-labeled synthetic oligonucleotides containing putative EBE (Etv2 binding element) sequences at room temperature for 10 min, and separated on a 4% acrylamide nondenaturing gel in Tris/Borate/EDTA buffer. For the supershift assays, anti-HA antibody (sc-805; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to the reaction for 20 min at room temperature after the formation of the protein-DNA complex. Synthetic nucleotides generated were as follows: EBE-1: 5′ CTGAGACTTCCTGAAGTT 3′, EBE-2: 5′ TCCTCTGGGAAATGGCCC 3′, EBE-3: 5′ CCTGGACTTCCT 3′, EBE-1mut: 5′ CTGAGACcggcTGAAGTT 3′, EBE-2mut: 5′ TCCTCTGgtccATGGCCC 3′, EBE-3mut: 5′ CCTGGACcggcT 3′.

Recombinant reporter constructs and cell transfection

The recombinant reporter gene construct was obtained by cloning a PCR-amplified 241 bp fragment Region II of the Sox7 promoter (Fwd: 5′ CCATTTGATTTCAGCGTCCAGGC, Rev: 5′ CCACCTACAGGAAGTCCAGGATGAGC 3′) into the SacI and XhoI sites of the pGLT vector (pGL3basic; Promega, with hsp70 TATA boxes inserted at the HindIII site). Mutation of the EBEs was performed by site-directed mutagenesis. Luciferase constructs and increasing amounts of HA-tagged-Etv2, Ets1, or Erg expression vectors were transfected into C2C12 myoblasts using the Lipofectamine/Plus reagent method according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and incubated for 24 h. Cells were then harvested in passive lysis buffer and assayed using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (E2920; Promega).

Quantification of endothelial progenitor cells by flow cytometry

Day 6 EBs were harvested and dissociated as previously described [41]. Briefly, EBs were incubated in Collagenase Type I (17100-017; Gibco) and triturated multiple times over a 10 min interval. Cells were washed, filtered, and stained with anti-Flk1-PE (12-58212-83; eBioscience) and anti-Cdh5-APC (17-1441-80; eBioscience). Stained cells were analyzed on an FACSAria (BD Biosciences) to quantify double positive (Flk1+/Cdh5+) endothelial progenitors cells (EPCs) [41].

ShRNA knockdown of Sox7

The shRNA vector pLKO.1 containing the mouse Sox7-specific RNAi sequence 5′ CCTGGCTTTGACACCTTGGAT 3′ (TRCN0000086052) was introduced into the Etv2 over-expressing mES cells mentioned earlier by lentiviral transduction after replacement of the puromycin resistance gene in pLKO.1 with eGFP. Infected mES cells were sorted twice while selecting for GFPbright cells, resulting in an mES cell line with constitutive Sox7 shRNA expression and inducible Etv2 over-expression.

EB culture in Type I Collagen gel for endothelial sprouting assessment

EBs were prepared by the hanging drop method using the indicated mES lines, and cultured in suspension on a rotating plate for 7 days. After 7 days, the EBs were transferred to Collagen Type I-containing medium (1.25 mg/mL, catalog #354249; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) at a concentration of 150–200 EBs per p30 Petri dish, according to the protocol described by Feraud et al. [44]. EBs were dosed with vascular endothelial growth factor (rhVEGF, catalog #293-VE; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a concentration of 50 ng/mL, incubated for 72 h, and scored for sprouting.

Statistical analysis

All P-values were calculated using Student's t-test analysis.

Results

Etv2 and Sox7 expression patterns in EBs

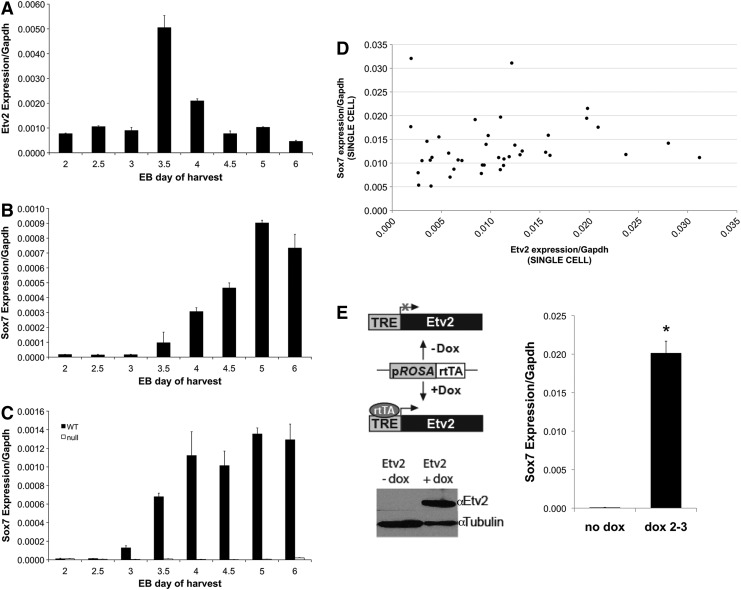

Transcriptome analysis performed on E8.5 Etv2-mutant embryos compared with wild-type littermates revealed decreased expression of Sox-F family transcription factors in the Etv2 mutant embryo [45]. To further assess the temporal relationship between Etv2 and Sox7, gene expression patterns were followed in developing EBs, beginning on day 2 until day 6. Etv2 mRNA expression had a narrow window of induction peaking at day 3.5 followed by rapid downregulation to baseline levels by EB day 4.5 (Fig. 1A). Sox7 expression was initiated at day 3.5 with a gradual increase through EB day 6 (Fig. 1B). The onset of Sox7 mRNA after Etv2 upregulation corroborates the hypothesis that Sox7 is a potential direct downstream target of ETV2. In addition, analysis of EBs from ES cells generated from Etv2-mutant and WT-littermate blastocysts showed complete absence of Sox7 mRNA in the Etv2-mutant EBs (Fig. 1C); while the pattern of Sox7 mRNA expression in EB differentiation assays of the WT littermate cells was similar to the Ainv18 ES cell line (Fig. 1B), and it simply shifted 0.5 days due to a variation in embryonic staging and ES cell derivation. Although both Etv2 and Sox7 have previously been described in the EPC population, to confirm that Etv2 and Sox7 were present in the same cell, single-cell qRT-PCR was performed using FLK1+/CDH5+ EPCs derived from EBs harvested at day 5. This demonstrated that Sox7 and Etv2 were co-expressed in all 40 cells assayed (Fig. 1D). Finally, a dox-inducible ETV2 over-expressing ES cell line was utilized to show that over-expression of ETV2 in EBs before the appearance of endogenous ETV2 resulted in significant induction of Sox7 mRNA compared with the control EBs (Fig. 1E). Over-expression of Etv2 in engineered ES cells, after induction with dox, was observed at the mRNA level (data not shown) and at the protein level by western blot analysis (Fig. 1E).

FIG. 1.

Etv2 and Sox7 expression patterns in embryonic bodies (EBs). (A) Etv2 mRNA expression in EBs prepared using A2lox-Cre mES cells. EBs were cultured and harvested at indicated time points. (B) Sox7 mRNA expression in EBs prepared using A2lox-Cre mES cells. EBs were cultured and harvested at specific time points. Etv2 and Sox7 mRNA expression was determined using qRT-PCR and normalized to Gapdh expression. (C) Sox7 mRNA expression in EBs prepared using mES derived from Etv2-null blastocysts and their wild-type littermates. (D) Etv2 versus Sox7 mRNA expression in single EPCs (n=40) derived from EBs harvested on day 5 and sorted for FLK1+/CDH5+. (E) Schematic of the reverse tetracycline transactivator (rtTA)/tetracycline-responsive element (TRE) dox-inducible Etv2 over-expression system. Dox-inducible ETV2 over-expression for 24 h (day 2–3) was confirmed using western blot analysis. Sox7 mRNA expression was determined in EBs harvested on day 3 by qRT-PCR. Induction of ETV2 revealed significantly increased expression of Sox7 mRNA (*P<0.05, n=3).

ETV2 binds and activates the Sox7 promoter

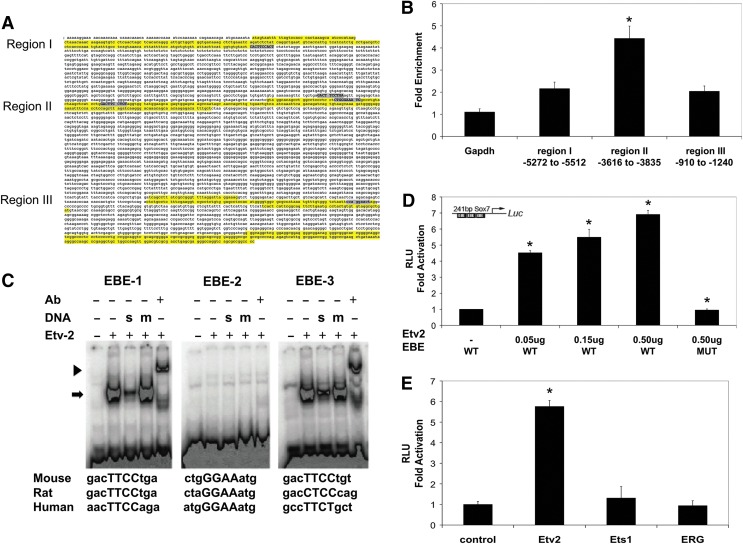

The 10 kb upstream regions of the mouse, human, and rat Sox7 gene were aligned, and conserved regions between species were identified. In addition to the homology of the proximal promoter, three additional upstream regions had conserved sequences: region I (−5272 to −5512 bp from the transcriptional start site), region II (−3616 to −3835), and region III (−910 to −1240). Putative EBEs corresponding to the sequence G/C C/G C/a G A G/a T/c [46] were identified in all three regions, (Fig. 2A). All three regions of the Sox7 upstream region were tested for ETV2 binding using the chromatin immuno-precipitation (ChIP) technique from cells expressing HA epitope-tagged ETV2. Enrichment of each region, after immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody, was determined by qRT-PCR and compared with a Gapdh control (Fig. 2B). The fragment containing three putative EBEs, from −3616 to −3835 upstream of the transcriptional start site, was significantly enriched 4.4±0.6-fold, suggesting that ETV2 binds to this region of the Sox7 promoter. EMSA revealed that ETV2 binds to two of the three putative EBEs identified in region II of the Sox7 promoter (Fig. 2C). This binding could be supershifted with an HA antibody that recognized the ETV2-HA fusion construct, and it could be competed with WT synthetic oligonucleotide but not with mutated synthetic oligonucleotide (Fig. 2C). The ability of this regulatory fragment of Sox7 to confer ETV2-dependent transcriptional activation was tested by fusing the 241 bp fragment containing the three EBE sequences (−4002 bp to −3761 bp) to the luciferase reporter and performing transcriptional assays in C2C12 myoblasts. As shown in Fig. 2D, co-transfection of the reporter plasmid with increasing amounts of ETV2-expressing vector resulted in a dose-dependent activation of luciferase activity (4.38±0.13-fold, 4.92±0.50-fold, and 6.63±0.26-fold (P<0.05, n=3)) compared with the control (no ETV2-expressing plasmid). Moreover, the reporter plasmid in which all three EBE sequences were mutated had no activation, even with maximal amounts of ETV2 (1.03±0.07-fold change; P<0.05, n=3; Fig. 2D). Transcriptional assays using expression plasmids for ETS1 and ERG (ETS-family proteins expressed during endothelial development) showed that the 241 bp region containing the EBE sequences specifically responded to ETV2 but not to other closely related proteins (Fig. 2E). In combination, these data show that ETV2 binds two EBEs of the Sox7 promoter (EBE-1: −3936 to −3926 and EBE-3: −3778 to −3768), and it confers ETV2-dependent activation. Based on these data, we conclude that Sox7 is a direct downstream target of ETV2.

FIG. 2.

ETV2 binds and activates the Sox7 promoter. (A) Alignment of 10 kb upstream region of the mouse, rat, and human Sox7 gene sequence revealed conservation of the proximal promoter and three additional regions highlighted in yellow: region I (−5272 to −5512 bp from the transcriptional start site), region II (−3616 to −3835), and region III (−910 to −1240). Putative EBEs were identified in all three regions (shaded gray). (B) ChIP assay using chromatin isolated from ETV2 over-expressing EBs (dox treatment for day 3–4, harvested at day 4) showed significant enrichment of the Sox7 upstream region II by ETV2 (*P<0.05, n=6). (C) Putative EBEs were tested for ETV2 binding using EMSA. Radiolabeled probes containing the putative binding sites, as shown, were incubated with in vitro synthesized HA-ETV2 protein to form a specific complex with EBE-1 and EBE-3, but not EBE-2 (arrow). Addition of specific synthetic oligonucleotide (s) was able to compete the complex, but not the mutated oligonucleotide (m). Antibody to the HA-tag supershifted the complex (arrowhead), indicating specificity of the complex. (D) A 241 bp fragment of region II containing the three putative EBEs was fused to a luciferase (luc) reporter gene and transfected into C2C12 myoblast cells with increasing amounts of the Etv2 expressing plasmid. Luciferase activity was normalized to activity in the absence of ETV2. Mutation of the EBEs (Mut) resulted in significantly reduced activity for the Sox7 promoter (*P<0.05, n=3). (E) A 241 bp fragment of region II containing the three putative EBEs was fused to a luciferase (luc) reporter gene and transfected into C2C12 myoblast cells with Etv2, Ets1, Erg, or control expression plasmids (0.5 μg). Luciferase activity was normalized to activity with control plasmids. Reporter activity was specific to the ETV2 receptor but not to other family members (*P<0.05, n=6).

Sox7 increases EPCs in EBs

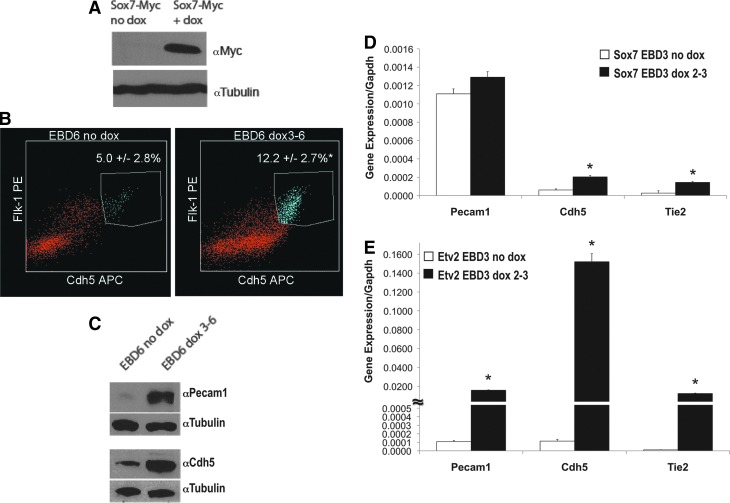

Etv2 is essential for the development of the endothelial lineage [14]; we, thus, hypothesized that ETV2 functions through a SOX7-dependent pathway in endothelial development. The effect of SOX7 over-expression on the production of FLK1+/CDH5+ EPCs was assessed in EBs harvested at day 6 [42,45,47]. Induction of SOX7-MYC for 72 h (day 3–6, Fig. 3A) significantly increased FLK1+/CDH5+ EPCs as compared with the control (12.2%±2.7% vs. 5.0%±2.8%, P<0.05, n=9; Fig. 3B); however, the fold increase was consistently lower compared with the changes seen with ETV2 over-expression (twofold vs. threefold) (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd), suggesting that SOX7 alone could not completely replicate the actions of ETV2. In addition to increasing the number of EPCs, SOX7 over-expression also increased protein expression of the endothelial proteins PECAM1 and CDH5 as evidenced by western blot analysis (Fig. 3C). Next, we addressed whether Sox7 could induce the endothelial lineage before the onset of Etv2 expression. SOX7 was over-expressed before endogenous expression of ETV2 in EBs by inducing with dox on days 2–3, and a significant increase in mRNA for the endothelial genes Cdh5 and Tie2 was detected (3.30±0.13-fold and 4.01±0.10-fold respectively, P<0.05, n=3; Fig. 3D). However, the levels of expression of these genes and the fold increase were much less than those observed in EBs with ETV2 over-expression at the same timing (Cdh5 1327±83-fold, Tie2 1070±40-fold, and Pecam1 145±4-fold; Fig. 3E). This observation is consistent with the notion that SOX7 functions downstream of ETV2.

FIG. 3.

SOX7 over-expression results in increased levels of endothelial progenitors cells (EPCs) and endothelial gene expression. (A) EBs were prepared using SOX7-MYC over-expressing mES cells and cultured for 6 days. Dox was added for 72 h (days 3–6). SOX7-MYC over-expression was confirmed by western blot analysis. (B) FACS analysis of FLK1+/CDH5+ double-positive EPCs derived from EBs at day 6 showed a significant increase in SOX7 over-expressing EBs (*P<0.05, n=7). (C) SOX7 over-expression for 72 h (day 3–6) increased expression of the endothelial genes PECAM1 and CDH5 in EBs at day 6 as shown by western blot analysis. (D) Induction of SOX7 with dox for 24 h (days 2–3) in EBs harvested on day 3, before the onset of endogenous Etv2, revealed increased expression of endothelial transcripts by qRT-PCR (*P<0.05, n=3). (E) Induction of ETV2 with dox for 24 h (days 2–3) in EBs harvested on day 3, before the onset of endogenous Etv2, revealed increased expression of endothelial transcripts by qRT-PCR. Note the level of induction is higher with ETV2 (E) compared with SOX7 (D) over-expressing cells.

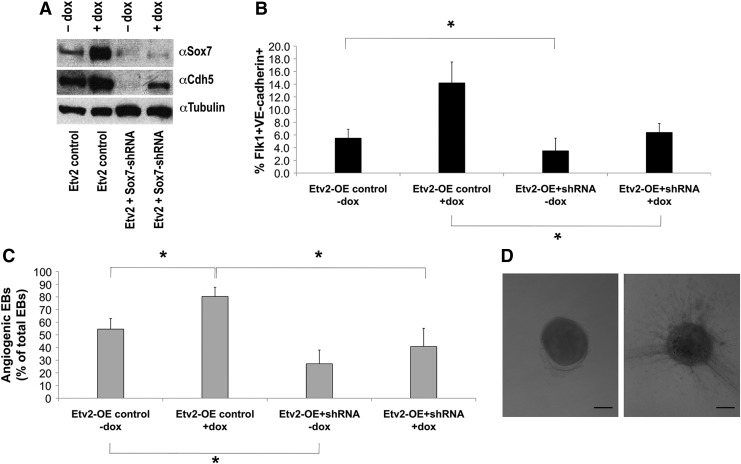

The role of SOX7 in the ETV2 pathway was further investigated by engineering cells in which ETV2 could be over-expressed in the presence of Sox7 inhibition. ShRNA technology was combined with the dox-inducible over-expressing ES-system to obtain such an mES cell line, and the ability to produce EPCs in EBs was assessed. EBs were made using hanging drop technology and cultured in suspension for 6 days. ETV2 was over-expressed with dox from day 3 to 6, and shRNA for Sox7 was constitutively expressed. To show that knockdown by Sox7 shRNA was effective, protein levels were analyzed by western blot. SOX7 and CDH5 a downstream target of Sox7 [37], protein levels were induced by dox in control cells (in the absence of shRNA), and clearly decreased in the presence of Sox7 shRNA. However, the closely related Sox-F family members SOX17 and SOX18 did not show changes in protein levels in the presence of Sox7 shRNA, indicating knockdown specificity of the Sox7 shRNA to Sox7 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Having validated our system, EBs were collected on day 6 and FLK1+/CDH5+ cells were quantified. ETV2 over-expressing EBs containing control pLKO.1 vector had percentages of FLK1+/CDH5+ cells similar to those previously observed in ETV2 over-expressing cells not infected with lentivirus with a threefold increase in double-positive cells on over-expression (no dox: 5.5%±1.4%, dox: 14.2%±3.3%, P<0.05, n=6; Fig. 4B). In the presence of Sox7 shRNA, the ETV2 over-expressing cells had a significantly lower percentage of FLK1+/CDH5+ cells when compared with ETV2 over-expressing cells containing the control pLKO.1 vector (6.4%±1.4% vs. 14.2%±3.3%, P<0.05, n=6; Fig. 4B). Sox7 inhibition significantly decreased the level of FLK1+/CDH5+ in un-induced cells (5.5%±1.4% vs. 3.5%±2.0%, P<0.05, n=10, Fig. 4B). To further examine the effects on mesodermal commitment, we analyzed FLK1+ cells in EBs collected at day 4 (Table 1). The data indicate that while ETV2 over-expression increases the FLK1+ cells at day 4 (66.5%±3.5% vs. 90.5%±5.5%, P<0.05, n=4), these cells were significantly decreased in SOX7 over-expressing cells (73.1%±6.1% vs. 60.2%±5.5%, P<0.05, n=4). Knockdown of Sox7 generated some variability in the responses and resulted in statistically insignificant differences in the day 4 FLK1+ population.

FIG. 4.

Sox7 shRNA decreases endothelial progenitor cell production and angiogenic sprouting in ETV2 over-expressing EBs. (A) EBs were prepared using ETV2 over-expressing mES cells containing lentivirus constitutively expressing shRNA for Sox7 or control. Dox was added for 72 h (days 3–6) and EBs cultured for 6 days. Western blot analysis in EBs collected on day 6 shows successful knockdown of SOX7 and CDH5 proteins by Sox7 shRNA. (B) EBs were prepared using ETV2 over-expressing mES cells containing lentivirus constitutively expressing shRNA for Sox7 or control. Dox was added for 72 h (days 3–6) and EBs cultured for 6 days. FACS analysis of FLK1+/CDH5+ double-positive EPCs derived from EBs at day 6 showed a significant increase in EPCs in cells over-expressing ETV2. A significant decrease in EPCs is observed in the presence of Sox7 shRNA (*P<0.05, n=6). (C) EBs were prepared using ETV2 over-expressing mES cells containing lentivirus constitutively expressing shRNA for Sox7 or control vector. Dox was added for 96 h (days 3–7) and EBs cultured in media for 7 days. On day 7, EBs were transferred to a collagen secondary culture (1.25 mg/mL Collagen Type I) and incubated for another 72 h, at which point the EBs were scored for sprouting. ETV2 significantly increased angiogenic sprouting (*P<0.05, n=4 experiments with ∼150–200 EBs scored per condition per experiment). There were significantly fewer angiogenic EBs when Sox7 shRNA was present in both ETV2 over-expressing and not over-expressing EBs (*P<0.05, n=4 experiments with ∼150–200 scored per condition per experiment). Inhibition of endogenous Sox7 (no dox) significantly decreased angiogenic EBs compared with EBs without Sox7 shRNA (*P<0.05, n=4 experiments with ∼150–200 scored per condition per experiment). (D) Representative brightfield images of angiogenic and nonangiogenic EBs after 72 h in collagen. Size bar=50 μm.

Table 1.

Quantitation of Mesodermal Flk1+ Cells in Embryonic Bodies Collected at Day 4 After Induction with dox for 24 h

| %Flk1+ cells | |

|---|---|

| ETV2-OE−dox | 65.5±3.5a |

| ETV2-OE+dox | 90.5±5.5a |

| SOX7-OE−dox | 73.1±6.1b |

| SOX7-OE+dox | 60.2±5.5b |

| ETV2-OE+shRNA−dox | 74.6±13.6, ns |

| ETV2-OE+shRNA+dox | 78.2±12.2, ns |

P<0.05, n=4.

P<0.05, n=4.

ns=not significant.

Functional role of Sox7 in the ETV2 pathway

Having established an ETV2-Sox7 pathway in progenitor cells, an angiogenic assay was performed to further define the functional role of SOX7 in the ETV2 pathway in vascular development. EBs were prepared using the hanging drop technique and mES with inducible Etv2 with or without Sox7 shRNA. EBs were cultured in suspension for 7 days, before transfer to secondary collagen culture for 72 h in medium containing rhVEGF. Over-expression of ETV2 significantly increased angiogenic sprouting in EBs from 54.6%±8.4% to 80.4%±7.2% (P<0.05, n=4; Fig. 4C, D), and these values were consistent with previously observed values [48]. Sox7 knockdown significantly decreased the number of sprouting EBs to 27.2%±10.8% and 40.9%±14.3% in EBs with or without ETV2 over-expression, respectively (P<0.05, n=4; Fig. 4C), further supporting the hypothesis that ETV2 regulates transcriptional networks which include Sox7 to carry out its functions during vascular development.

Discussion

It was previously demonstrated that Etv2 is expressed early during embryogenesis in the endocardial/endothelial lineage and that Etv2-deficient embryos are lethal, lacking endocardial/endothelial and hematopoietic lineages [14,21,23,45]. In the zebrafish model system, Etv2 has also been shown to be important for vascular development, initially for EPC specification, and later in hemogenic endothelial cells [49,50]. Genetic fate mapping analysis utilizing an Etv2-cre transgenic mouse model confirmed that ETV2-expressing cells give rise to both hematopoietic and endothelial lineages [45].

The Sox-F family members (Sox7, Sox17, and Sox18) have been shown to be important in the formation of the endodermal lineages, regulation of hematopoietic cells, and cardiovascular development [24,27,31,32,35,36,51]. In the endothelial system, recent studies have implicated Sox7 as an important factor in hematopoietic specification in addition to its importance in endothelial precursors [52]. Zebrafish studies also demonstrated that Sox7 and Sox18 were expressed predominately in the vasculature, and reduced expression of both genes resulted in defective vasculature development [25,36,53]. Gandillet et al. have shown that knockdown of Sox7 in EB differentiation assays severely affected both endothelial and hematopoietic precursors [54]. Recently, it was shown that continued enforced expression of SOX7 in hemangioblast-derived blast colonies resulted in sustained expression of endothelial markers while impairing hematopoietic differentiation [37]. This same study implicated Cdh5, a gene known to be downstream of ETV2, as a direct downstream target of SOX7 [21,55]. Although there is significant overlap of Etv2 and Sox7 function in early endothelial and hematopoietic development, as well as apparent overlap of transcriptional pathways, a direct linkage between Etv2 and Sox7 has not previously been described.

Given that the Sox-F family of genes is known to be expressed in the endothelial lineage, and that previous studies have established that Etv2 is required for the establishment of hemangiogenic mesoderm and the induction of early endothelial progenitor cells [15,20–23], our finding of the downregulation of the Sox-F family of genes in the absence of Etv2 could have been predicted (in situ hybridization data not shown). However, it was quite striking that the expression of Sox7, but not all Sox-F family members, was completely abolished in the absence of Etv2. Single-cell expression analysis confirmed that Etv2 and Sox7 are co-expressed in EPCs. These findings supported our initial data revealing that Sox7 could be a direct downstream target of ETV2, and that the Sox-F family members have specific roles in endothelial development. The upstream regulation of Sox7 is poorly understood. Research in cancer biology has implicated both p38MAPK and β-catenin/Wnt pathways as regulators of Sox7 expression [56]. However, the developmental regulation of Sox7 has not been previously described. Our findings from rigorous promoter analysis and protein-DNA interaction, gel shift, and transcriptional assays confirm that ETV2 directly activates Sox7. It is important to note, however, that Sox7 alone does not seem to induce the early endothelial lineage as efficiently as Etv2. This is not surprising given the critical role of Etv2. It is likely that Etv2 also contributes to endothelial induction through Sox7-independent pathways. However, a functional role of this newly described ETV2-Sox7 activation was also substantiated. Reduction of Sox7 in the presence of ETV2 activation significantly reduced both the percentage of endothelial progenitors and the angiogenic potential of embryoid bodies. Furthermore, perturbation of Sox7 expression at even basal levels of Etv2 expression also significantly reduced the angiogenic capacity of embryoid bodies, further confirming that Etv2 regulates endothelial development via transcriptional pathways which include Sox7. These results from our current studies provide further insights into the transcriptional pathways of the endothelial lineage.

Initial work focused on the role of the Sox-F family members in cardiogenesis and angiogenesis and demonstrated that the family largely has redundant roles in these systems [5,24–28,32,34,35]. Although there are areas of overlap in the family member's functional roles, studies have begun to focus on the identification of the unique aspects of the developmental pathways of each individual member. Recent work has shown that each member also possesses specific functions as illustrated by the importance of Sox18 in lymphangiogenesis, the role of Sox17 in fetal hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and definitive endoderm formation, and the requirement of Sox7 for primitive endoderm formation [57]. In the present study, we also highlight the individual role of Sox7 in endothelial development. Additional studies will be necessary to completely define the comprehensive role of each Sox-F family member in endothelial development.

In this article, a previously unknown direct link between ETV2 and Sox7 is established. We provide evidence that Sox7 is one of the targets of ETV2 necessary to regulate the endothelial pathway, resulting in endothelial progenitor cell upregulation and increased angiogenic sprouting. Since the role of Sox7 in endothelial development is generating intense interest, future studies that investigate downstream targets of Sox7 and their role in endothelial development will further illuminate the importance of this pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Kyba for providing the Tet-on inducible Ainv18 ES cell line. They also acknowledge Michelina Iacovino and Alessandro Magli for critical discussions and technical assistance. They recognize the University of Minnesota Genomic Center for the single-cell capture qRT-PCR work. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K08 HL102157-01).

Part of this work was presented at the American Heart Association (AHA) 2012 Scientific Sessions, Los Angeles, CA.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Coultas L, Chawengsaksophak K. and Rossant J. (2005). Endothelial cells and VEGF in vascular development. Nature 438:937–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drake CJ. and Fleming PA. (2000). Vasculogenesis in the day 6.5 to 9.5 mouse embryo. Blood 95:1671–1679 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson JE, 3rd, Kelley RW. and Patterson C. (2005). Mechanisms of endothelial differentiation in embryonic vasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:2246–2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGrath KE, Koniski AD, Malik J. and Palis J. (2003). Circulation is established in a stepwise pattern in the mammalian embryo. Blood 101:1669–1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakamoto Y, Hara K, Kanai-Azuma M, Matsui T, Miura Y, Tsunekawa N, Kurohmaru M, Saijoh Y, Koopman P. and Kanai Y. (2007). Redundant roles of Sox17 and Sox18 in early cardiovascular development of mouse embryos. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 360:539–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway SJ, Kruzynska-Frejtag A, Kneer PL, Machnicki M. and Koushik SV. (2003). What cardiovascular defect does my prenatal mouse mutant have, and why?. Genesis 35:1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris IS. and Black BL. (2010). Development of the endocardium. Pediatr Cardiol 31:391–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misfeldt AM, Boyle SC, Tompkins KL, Bautch VL, Labosky PA. and Baldwin HS. (2009). Endocardial cells are a distinct endothelial lineage derived from Flk1+ multipotent cardiovascular progenitors. Dev Biol 333:78–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fishman MC. and Olson EN. (1997). Parsing the heart: genetic modules for organ assembly. Cell 91:153–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey RP. (2002). Patterning the vertebrate heart. Nat Rev Genet 3:544–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson EN. and Schneider MD. (2003). Sizing up the heart: development redux in disease. Genes Dev 17:1937–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson EN. and Srivastava D. (1996). Molecular pathways controlling heart development. Science 272:671–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parmacek MS. and Epstein JA. (2005). Pursuing cardiac progenitors: regeneration redux. Cell 120:295–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferdous A, Caprioli A, Iacovino M, Martin CM, Morris J, Richardson JA, Latif S, Hammer RE, Harvey RP, et al. (2009). Nkx2-5 transactivates the Ets-related protein 71 gene and specifies an endothelial/endocardial fate in the developing embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:814–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lammerts van Bueren K. and Black BL. (2012). Regulation of endothelial and hematopoietic development by the ETS transcription factor Etv2. Curr Opin Hematol 19:199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lelievre E, Lionneton F, Soncin F. and Vandenbunder B. (2001). The Ets family contains transcriptional activators and repressors involved in angiogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 33:391–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lie-Venema H, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, van Empel LJ, Boot MJ, Kerkdijk H, de Kant E. and DeRuiter MC. (2003). Ets-1 and Ets-2 transcription factors are essential for normal coronary and myocardial development in chicken embryos. Circ Res 92:749–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharrocks AD. (2001). The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2:827–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wernert N, Raes MB, Lassalle P, Dehouck MP, Gosselin B, Vandenbunder B. and Stehelin D. (1992). c-ets1 proto-oncogene is a transcription factor expressed in endothelial cells during tumor vascularization and other forms of angiogenesis in humans. Am J Pathol 140:119–127 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kataoka H, Hayashi M, Nakagawa R, Tanaka Y, Izumi N, Nishikawa S, Jakt ML. and Tarui H. (2011). Etv2/ER71 induces vascular mesoderm from Flk1+PDGFRalpha+ primitive mesoderm. Blood 118:6975–6986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koyano-Nakagawa N, Kweon J, Iacovino M, Shi X, Rasmussen TL, Borges L, Zirbes KM, Li T, Perlingeiro RC, Kyba M. and Garry DJ. (2012). Etv2 is expressed in the yolk sac hematopoietic and endothelial progenitors and regulates Lmo2 gene expression. Stem Cells 30:1611–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee D, Kim T. and Lim DS. (2011). The Er71 is an important regulator of hematopoietic stem cells in adult mice. Stem Cells 29:539–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee D, Park C, Lee H, Lugus JJ, Kim SH, Arentson E, Chung YS, Gomez G, Kyba M, et al. (2008). ER71 acts downstream of BMP, Notch, and Wnt signaling in blood and vessel progenitor specification. Cell Stem Cell 2:497–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fawcett SR. and Klymkowsky MW. (2004). Embryonic expression of Xenopus laevis SOX7. Gene Expr Patterns 4:29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herpers R, van de Kamp E, Duckers HJ. and Schulte-Merker S. (2008). Redundant roles for sox7 and sox18 in arteriovenous specification in zebrafish. Circ Res 102:12–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Asakura M, Inoue H, Nakamura T, Sano M, Niu Z, Chen M, Schwartz RJ. and Schneider MD. (2007). Sox17 is essential for the specification of cardiac mesoderm in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:3859–3864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsui T, Kanai-Azuma M, Hara K, Matoba S, Hiramatsu R, Kawakami H, Kurohmaru M, Koopman P. and Kanai Y. (2006). Redundant roles of Sox17 and Sox18 in postnatal angiogenesis in mice. J Cell Sci 119:3513–3526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang C, Basta T. and Klymkowsky MW. (2005). SOX7 and SOX18 are essential for cardiogenesis in Xenopus. Dev Dyn 234:878–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corada M, Orsenigo F, Morini MF, Pitulescu ME, Bhat G, Nyqvist D, Breviario F, Conti V, Briot A, et al. (2013). Sox17 is indispensable for acquisition and maintenance of arterial identity. Nat Commun 4:2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sacilotto N, Monteiro R, Fritzsche M, Becker PW, Sanchez-Del-Campo L, Liu K, Pinheiro P, Ratnayaka I, Davies B, et al. (2013). Analysis of Dll4 regulation reveals a combinatorial role for Sox and Notch in arterial development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:11893–11898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pennisi D, Gardner J, Chambers D, Hosking B, Peters J, Muscat G, Abbott C. and Koopman P. (2000). Mutations in Sox18 underlie cardiovascular and hair follicle defects in ragged mice. Nat Genet 24:434–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takash W, Canizares J, Bonneaud N, Poulat F, Mattei MG, Jay P. and Berta P. (2001). SOX7 transcription factor: sequence, chromosomal localisation, expression, transactivation and interference with Wnt signalling. Nucleic Acids Res 29:4274–4283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francois M, Caprini A, Hosking B, Orsenigo F, Wilhelm D, Browne C, Paavonen K, Karnezis T, Shayan R, et al. (2008). Sox18 induces development of the lymphatic vasculature in mice. Nature 456:643–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pennisi D, Bowles J, Nagy A, Muscat G. and Koopman P. (2000). Mice null for sox18 are viable and display a mild coat defect. Mol Cell Biol 20:9331–9336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cermenati S, Moleri S, Cimbro S, Corti P, Del Giacco L, Amodeo R, Dejana E, Koopman P, Cotelli F. and Beltrame M. (2008). Sox18 and Sox7 play redundant roles in vascular development. Blood 111:2657–2666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pendeville H, Winandy M, Manfroid I, Nivelles O, Motte P, Pasque V, Peers B, Struman I, Martial JA. and Voz ML. (2008). Zebrafish Sox7 and Sox18 function together to control arterial-venous identity. Dev Biol 317:405–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa G, Mazan A, Gandillet A, Pearson S, Lacaud G. and Kouskoff V. (2012). SOX7 regulates the expression of VE-cadherin in the haemogenic endothelium at the onset of haematopoietic development. Development 139:1587–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wat MJ, Shchelochkov OA, Holder AM, Breman AM, Dagli A, Bacino C, Scaglia F, Zori RT, Cheung SW, Scott DA. and Kang SH. (2009). Chromosome 8p23.1 deletions as a cause of complex congenital heart defects and diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet A 149A:1661–1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryja V, Bonilla S. and Arenas E. (2006). Derivation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Protoc 1:2082–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen TL, Martin CM, Walter CA, Shi X, Perlingeiro R, Koyano-Nakagawa N. and Garry DJ. (2013). Etv2 rescues Flk1 mutant embryoid bodies. Genesis 51:471–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iacovino M, Hernandez C, Xu Z, Bajwa G, Prather M. and Kyba M. (2009). A conserved role for Hox paralog group 4 in regulation of hematopoietic progenitors. Stem Cells Dev 18:783–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin CM, Ferdous A, Gallardo T, Humphries C, Sadek H, Caprioli A, Garcia JA, Szweda LI, Garry MG. and Garry DJ. (2008). Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha transactivates Abcg2 and promotes cytoprotection in cardiac side population cells. Circ Res 102:1075–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi X. and Garry DJ. (2010). Myogenic regulatory factors transactivate the Tceal7 gene and modulate muscle differentiation. Biochem J 428:213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feraud O, Prandini MH. and Vittet D. (2003). Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis from in vitro differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Methods Enzymol 365:214–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasmussen TL, Kweon J, Diekmann MA, Belema-Bedada F, Song Q, Bowlin K, Shi X, Ferdous A, Li T, et al. (2011). ER71 directs mesodermal fate decisions during embryogenesis. Development 138:4801–4812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown TA. and McKnight SL. (1992). Specificities of protein-protein and protein-DNA interaction of GABP alpha and two newly defined ets-related proteins. Genes Dev 6:2502–2512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iacovino M, Chong D, Szatmari I, Hartweck L, Rux D, Caprioli A, Cleaver O. and Kyba M. (2010). HoxA3 is an apical regulator of haemogenic endothelium. Nat Cell Biol 13:72–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feraud O, Cao Y. and Vittet D. (2001). Embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies development in collagen gels recapitulates sprouting angiogenesis. Lab Invest 81:1669–1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ren X, Gomez GA, Zhang B. and Lin S. (2010). Scl isoforms act downstream of etsrp to specify angioblasts and definitive hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 115:5338–5346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sumanas S. and Lin S. (2006). Ets1-related protein is a key regulator of vasculogenesis in zebrafish. PLoS Biol 4:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Downes M. and Koopman P. (2001). SOX18 and the transcriptional regulation of blood vessel development. Trends Cardiovasc Med 11:318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Costa G, Kouskoff V. and Lacaud G. (2012). Origin of blood cells and HSC production in the embryo. Trends Immunol 33:215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chung MI, Ma AC, Fung TK. and Leung AY. (2011). Characterization of Sry-related HMG box group F genes in zebrafish hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol 39:986–998e985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gandillet A, Serrano AG, Pearson S, Lie ALM, Lacaud G. and Kouskoff V. (2009). Sox7-sustained expression alters the balance between proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors at the onset of blood specification. Blood 114:4813–4822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wareing S, Mazan A, Pearson S, Gottgens B, Lacaud G. and Kouskoff V. (2012). The Flk1-Cre-mediated deletion of ETV2 defines its narrow temporal requirement during embryonic hematopoietic development. Stem Cells 30:1521–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou X, Huang SY, Feng JX, Gao YY, Zhao L, Lu J, Huang BQ. and Zhang Y. (2011). SOX7 is involved in aspirin-mediated growth inhibition of human colorectal cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol 17:4922–4927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Francois M, Koopman P. and Beltrame M. (2010). SoxF genes: Key players in the development of the cardio-vascular system. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:445–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.