Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to test the utility of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) as a resource for collecting data on patient-reported outcomes (PRO) within academic health centers at a chiropractic college; and, to describe changes in PRO following pragmatic chiropractic care incorporating instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization (IASTM) on pain symptoms.

Methods

This was a pre-post intervention design without a control group (case series) involving 25 patients (14 females and 11 males; 40.5 ± 16.39 years, range 20-70 years) who completed their chiropractic care and their baseline and post-treatment pain assessments. The pragmatic chiropractic care intervention included both spinal manipulation and IASTM to treat pain symptoms. PRO’s were collected using PROMIS to measure pain behavior, pain interference and pain intensity.

Results

The average pre-post assessment interval was 33 ± 22.5 days (95% CI, 23-42 days). The durations of treatments ranged from one week to 10 weeks. The median number of IASTM treatments was six. Pre-post decreases in T-scores for pain behavior and pain interference were 55.5 to 48.4 and 57.7 to 48.4, respectively (P < .05). Only 12 patients had a baseline T-score for pain intensity greater than 50. The pre-post decrease in pain intensity T-scores for these 12 patients was from 53.4 to 40.9.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of a case series design, these data provide initial evidence on the utility of PROMIS instruments for clinical and research outcomes in chiropractic patients.

Key indexing terms: Manual therapy, Connective tissue, Manipulation, Spinal, Chiropractic

Introduction

Instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization (IASTM) may enhance the ability of clinicians to effectively break down scar tissue and fascial restrictions. Preliminary data suggested that IASTM treatments may effectively alleviate the clinical symptoms of various cumulative trauma disorders.1–5 For example, in the case of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), IASTM may be used to provide a precise method of manipulating the myofascia of the forearm, wrist and palm of the hand to alleviate compression directly over the pathway of the median nerve. A pilot study provided evidence that manual therapy, including IASTM, increased range of motion and grip strength in wrists affected by CTS.1 Preliminary data also indicated that chiropractic manipulations—of the cervical spine, shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints—physiotherapy procedures, stretching exercises, and/or myofascial release techniques were effective in relieving clinical symptoms and functional loss in CTS patients who were candidates for surgical interventions.6–9 These preliminary studies also showed improvements in sensory and motor conduction latencies of the median nerve and increases in anatomical dimensions of the carpal tunnel as revealed by electrodiagnosis studies and MRI, respectively.8,9 These clinical improvements support the theory that IASTM may increase myofascial mobility; thereby, increasing blood flow within the vasa nervorum, which in turn, alleviates local ischemic effects that may contribute to pain generation and impairments of muscle and nerve function.

There are also case reports that describe clinical outcomes with IASTM treatments. An athlete presented with chronic ankle pain, reduced range of motion, fibrotic lesions surrounding the ankle joint, and a medical history including recurrent ankle sprains, two arthroscopic surgeries, and physiotherapy.3 The athlete reported no pain, increased range of motion, and improved physical function following six to eight weeks of IASTM treatments.3 Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not reveal any anatomical changes to the ankle, the athlete did stop taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications.3 After 8 weeks of IASTM treatments and stretching exercises for palmar adhesions due to Dupuytren’s contracture, there were increases in active (11.5% and 57.1%) and passive (77.8% and 30.0%) ranges of motion of the 4th and 5th digits, respectively; photographic evidence of decreased contractures; and subjective improvements in hand function.10 There are numerous case reports on the inclusion of IASTM in multimodal rehabilitative programs for treating post-surgical anterior cruciate ligament or patellar tendon repairs,11,12 Achilles or high hamstring tendinopathy,13–17 anterior chest pain and midthoracic stiffness associated with acute costochondrities,18 lower back pain,19,20 and various other musculoskeletal injuries of the upper and lower extremities.21–31 These case reports suggested that IASTM may promote faster recovery times, alleviate pain, and facilitate improvements in joint and muscle function to “optimal” levels. However, comparative clinical studies were inconclusive on the independent or additive therapeutic benefits of IASTM.1,32

Despite the data presented above and a small number of mechanistic studies on IASTM using animal models,33–36 clinical indications and treatment protocols for using IASTM remain theory-driven. ConnecTX Therapy is a recent development in the field of IASTM that uses a single, double-beveled, convex and concave, instrument with long and short radius surfaces to treat the various shapes and curves of soft tissue structures of the body.37 ConnecTX Therapy protocols reflect meticulous contributions of time and energy by clinical academicians to provide evidence-informed recommendations underlying treatment protocols.37 However, data are still needed to substantiate, modify, or refute these evidence-informed recommendations for treating patients with ConnecTX Therapy protocols.

Randomized trials with control groups and blinding are the gold standard of clinical research to address treatment effectiveness. Randomized trials are expensive to implement and their external validity depends upon adequately defining: (1) hypotheses; (2) recruitment strategies; (3) sampling of patient populations to include eligibility criteria, sample size and randomization procedures; (4) therapeutic and control interventions with procedures to monitor treatment adherence and adverse events; (5) blinding; (6) primary and secondary outcome measures; and (7) appropriate statistical procedures.38 Thus, there is growing emphasis on the development of reliable and valid patient-reported outcomes (PRO) that may be used to facilitate the interpretation and comparison of clinical research.39–42 PRO instruments that are reliable, precise, and valid within a “real world” clinical setting would provide another source of data for conducting rigorous clinical research.43–45 Towards this end, the National Institutes of Health funded Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is developing reliable and valid PRO instruments and a data management system that are readily available to compare how various treatments might affect what patients are able to do and the symptoms they experience across medical conditions and relative to the US population.39,41–44,46,47

Comparing PRO across musculoskeletal diagnoses requires a valid, reliable and precise PRO instrument that assumes a generic latent trait that is common across musculoskeletal diagnoses.48,49 It may be debated that the manifestation of pain symptoms in the well-defined domains of intensity, behavior and interference are condition specific and the use of Neck Disability Index, Roland Morris Disability, Oswestry Disability Index and numeric rating scales for pain intensity are examples of legacy instruments that meet criteria of valid, reliable and precise PRO instruments.48–58 However, we deemed it important to compare PRO across musculoskeletal diagnosis to substantiate, refute or modify our current evidence-informed ConnecTX Therapy protocols that vary by spinal region. ConnecTX Therapy Protocols vary by spinal regions of the body with respect to handholds or grips, instrument edges and surface radius, and treatment angles, directions, and maneuvers.37 In addition, IASTM techniques with and without spinal manipulation or extraspinal joint manipulations were proposed to address a multitude of soft tissue symptoms involving all spinal segments and lower and upper extremities as reported in the clinical literature above.

As global health outcomes, PROMIS instruments assess physical health, mental health and social health within well-defined domains that allow for comparisons of PRO across clinical research studies and diseases.39–42 The selections of PROMIS instruments to measure pain intensity, pain interference and pain behavior were aligned with using a heterogeneous sample of patients with various painful musculoskeletal conditions that typically present for care at an academic health center of a chiropractic college. The purpose of this study was to test the utility of PROMIS as a resource for collecting data on PRO within academic health centers at a chiropractic college. The specific aim was addressed by describing changes in PRO following pragmatic chiropractic care incorporating IASTM on pain symptoms.

Methods

Study Design

This was a prospective case series describing changes in pain symptoms after pragmatic chiropractic care incorporating IASTM in patients presenting with musculoskeletal disorders related to the spine. The assessment time points were: (1) baseline and (2) at completion of care.

Participants

The inclusion criteria were patients aged 20 to 70 years regardless of gender and ethnicity with a diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorder of the spine and their treatment plan included ConnecTX Therapy. Patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. A sample size of 25 to 30 subjects was deemed appropriate based upon the assumption of normality and the central limit theorem underlying the mathematics of inferential statistics.59 We recruited patients presenting themselves for care at academic health centers of a chiropractic college (December 2012 to September 2013). The patients were financially responsible for their treatment costs at the academic health centers. There was no compensation for completing the assessment instruments.

The New York Chiropractic College Institutional Review Board approved the research project and the use of an electronic informed consent document. At the baseline assessment time point, the clinician reviewed the electronic informed consent document on an iPad (Apple, Cupertino, CA) with the patient. The electronic informed consent document required patients to use a checkmark to agree to participate in the study, instead of their written signature. The electronic informed consent document was endorsed by all patients. The principal investigator retrieved the informed consent data from the Assessment Center which included the date and time when consent was endorsed by each patient enrolled in the study. After endorsing the electronic informed consent document, the patient was given the iPad to complete the PROMIS survey instruments. The electronic informed consent process and data collection occurred in the treatment room and the clinician did not assist the patient with completing the PROMIS survey instruments.

Intervention

Documentation of pragmatic chiropractic care and ConnecTX Therapy was provided to the investigator by the treating chiropractor through their electronic health records. A summary of patient care documented: (1) primary diagnosis, e.g. region of segmental dysfunction; (2) the frequency of treatments—eg, number per week for the duration of treatments; and (3) delivery of spinal and/or extraspinal manipulations; (4) treatment site for ConnecTX Therapy; and (5) a list of side effects per treatment visit including none related to ConnecTX Therapy. The treating chiropractors received training in ConnecTX Therapy treatment protocols as described in the ConnecTX Therapy Technique Manual.37

Outcomes

While in the treatment room and without assistance, patients completed three electronic surveys from a secure website using an iPad. Age, gender, ethnicity, doctor’s name and their first and last names were also collected. The three PROMIS electronic surveys were: Pain Behavior, Pain Interference and Pain Intensity. The item stems described a pain behavior or an activity that pain may limit (pain interference). The Pain Interference instrument had five response options from which the subject selects their one response (1 = Not at all, 2 = A little bit, 3 = Somewhat, 4 = Quite a bit, 5 = Very much). Pain Behavior instrument included a sixth response option to allow the subject to report “no pain”. The Pain Intensity PROMIS instrument required patients to rate their pain as no pain, mild, moderate, severe or very severe within the following context: In the past seven days at its worst; In the past seven days on average and right now.

The principal investigator retrieved the data from the Assessment Center. Assessments of patient’s pain behavior and pain interference used computerized adaptive testing (CAT) that required responses on 4 to12 items. Parameters of CAT PROMIS instruments were set to achieve a standard error less than .30 after a minimum of four items, which corresponded to reliability greater than .90. The item selection method was maximum posterior weighted information.

The clinician reported harms for the ConnecTX Therapy treatments related to pain, bruising, petechiae, swelling and irritation and reddening of the skin. The clinicians rated the harms as none, mild, moderate, severe or extreme. The clinician used a paper document with a body diagram to rate ConnecTX Therapy harms. The clinician sent all of their ConnecTX Therapy treatment harms documents to the principal investigator at the completion of care.

Statistical Methods

Outcomes of the PROMIS survey instruments are expressed as T-scores with the score of 50 ± 10 being the average ± standard deviation for the United States general population. Although scoring of PROMIS survey instruments use item-level calibrations to increase accuracy of scoring, analyses of pain intensity at its worst, on average and right now as ordinal scale data were also conducted. Minimally important differences for PROMIS survey instruments are currently being developed.60 In our exploratory research project, we defined clinical improvement as having a T-score at baseline that was greater than 50 and showing a pre-post decrease in the T-score. Paired comparisons using repeated measures ANOVA models (2 levels of time) for T-scores and Wilcoxon signed ranked tests for ordinal data were used to describe changes in pain symptoms from baseline to after chiropractic care. SPSS, version 19.0 was the statistical package. The level of significance was .05.

Results

Study Population and Chiropractic Care

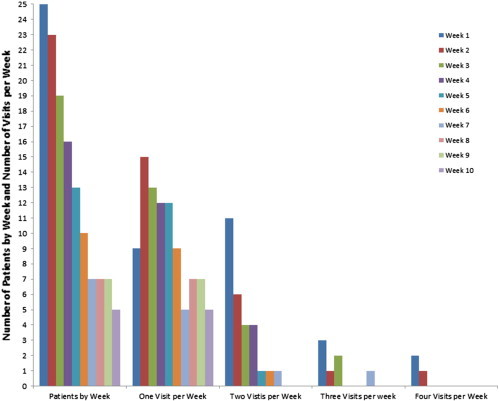

Twenty-five patients (14 females and 11 males; 40.5 ± 16.39 years, range 20-70 years) completed their chiropractic care and their baseline and post-treatment pain assessments. Treatment areas for segmental dysfunction were as follows: cervical region (n = 9), thoracic region (n = 3), thoraco-lumbar region (n = 2), lumbar region (n = 6), and lumbo-sacral region (n = 2). Chiropractic care consisted of a combination of spinal manipulation and ConnecTX Therapy. Bilateral carpal tunnel with wrist joint manipulations (n = 1) and forearm pain (n = 1) and bilateral knee pain (n = 1) without any form of joint/spinal manipulation were also treated with ConnecTX Therapy. The durations of treatments ranged from one week to 10 weeks. Fifty percent of the patients received chiropractic care during a five week period. The median number of ConnecTX Therapy treatments was six. Multiple treatment visits per week occurred mainly in the first four weeks with one visit per week occurring mainly from week five to week 10 of chiropractic care. The Figure summarizes the number of patients receiving chiropractic care per week and the number of patient visits per week.

Fig.

Summary of the number of patients receiving chiropractic care by week and the number of patient visits by week.

The average pre-post assessment interval of the 25 subjects completing the study protocol was 33 ± 22.5 days (95% CI, 23-42 days). Table summarizes outcomes data at baseline and after chiropractic care. Nine patients withdrew from the study (3 females and 6 males, 45.6 ± 13.57 years, range 29 to 66 years). Eight subjects were lost to follow-up while the other subject did not want to continue with ConnecTX Therapy. Treatment areas for segmental dysfunction were as follows: cervical region (n = 5), thoracic region (n = 1), and lumbar region (n = 3). The mean baseline assessment T-scores of these nine subjects were 52.1 ± 4.41 (95% CI, 48.7-55.4) for pain intensity, 58.0 ± 2.81 (95% CI, 55.8-60.7) for pain behavior, and 60.9 ± 7.26 (95% CI, 55.3-66.4) for pain interference.

Table.

Outcomes at Baseline and After Chiropractic Care (T-Scores ± Standard Deviations, 95% CIs, n = 25)

| Outcomes | Baseline | After Chiropractic Care |

|---|---|---|

| Pain Intensity | 49.5 ± 4.86 (47.5-51.6) | 40 5 ± 6.93 (37.6-43.4) |

| Pain Behavior | 55.5 ± 2.85 (54.3-56.6) | 48.4 ± 9.15 (44.6-52.2) |

| Pain Interference | 57.7 ± 7.13 (54.8-60.6) | 48.4 ± 7.88 (45.1-51.6) |

Pain Intensity

Only 12 patients had a baseline T-score for pain intensity greater than 50. The pre-post decrease in T-scores for these 12 patients from 53.4 to 40.9 was significantly greater than the pre-post decrease from 45.9 to 40.2 for the other 13 patients with baseline T-scores less than 50 (F(1, 23) Group x Time = 6.32, P < .05). When analyzing pain intensity on the ordinal scale for pain at its worst, on average and at the time of treatment, there were significant shifts in the distributions from moderate and severe rankings at baseline to no pain and mild rankings after chiropractic care (Wilcoxon signed ranked tests, P < .05). At baseline, rankings of pain into moderate and severe categories were 88% at its worst and 72% on average with the remaining patients reporting mild pain. After chiropractic care, rankings of pain shifted into no pain and mild categories: 76% at its worst and 88% for on average. At the time of the treatment, 56% of baseline rankings were in the no pain and mild pain categories while 96% of rankings at the last chiropractic visit were in the no pain and mild pain categories.

Pain Behavior

With the exception of one patient (T-score = 49.7), baseline T-scores for pain behavior were greater than 50. T-scores for three other patients did not decrease from baseline to after chiropractic care. Pre-post decreases in T-scores were − 8.1 ± 8.01 for patients showing clinical improvement (n = 21), 55.9 ± 2.57 to 47.8 ± 8.95. Overall (n = 25), T-scores decreased from 55.5 at baseline to 48.4 after chiropractic care with chiropractic care accounting for 43% of the variance of pre-post differences (Table, F(1,24) Time = 17.92, P < .05).

Pain Interference

With the exception of one patient (T-score = 38.6), baseline T-scores for pain interference were greater than 50. T-scores for three other patients did not decrease from baseline to after chiropractic care. These were the same four patients that did not show clinical improvement on the pain behavior outcome. Pre-post decreases in T-scores were -11.5 ± 8.37 for patients showing clinical improvement (n = 21), 59.4 ± 5.88 to 47.9 ± 7.84. Overall (n = 25), T-scores decreased from 57.7 at baseline to 48.4 after chiropractic care with chiropractic care accounting for 52% of the variance of pre-post differences (Table, F(1,24) Time = 25.62, P < .05).

Harms

Mild swelling, mild bruising and mild petechiae occurred in 16% of the treatments with ConnecTX Therapy and in 10, 13 and 12 of the 25 patients, respectively. Mild swelling, mild bruising, and mild petechiae occurred across all treatment visits with ConnecTX Therapy. Mild irritation and reddening of the skin occurred in 75% of the treatments with ConnecTX Therapy with all subjects experiencing this harm. In addition, clinicians reported moderate irritation and reddening of the skin within the first two treatments of three patients and within the first four treatments of two other patients. No pain, mild pain, moderate pain, and severe pain occurred in 53%, 25%, 12% and 11% of treatments with ConnecTX Therapy, respectively. The reports of severe treatment pain intensity were limited to four patients with six patients reporting their treatment pain intensity as moderate. Five patients reported no pain and 10 patients reported their pain intensity as mild during treatments with ConnecTX Therapy. These pain responses occurred across all visits with ConnecTX Therapy.

Discussion

Within the limitations of a case series design, these data provide initial evidence on the utility of PROMIS instruments for clinical and research outcomes in chiropractic patients. As the intervention involved both spinal manipulation and IASTM and did not include a control arm, the data is only descriptive and lacks generalizability. However, mild to moderate pain symptoms at baseline is representative of a chiropractic patient base.61–63 Preliminary evidence on minimally important differences (MID) for PROMIS instruments indicated that T-score MID range from 4 to 6 for pain interference.60 Changes in T-scores from baseline to after chiropractic care met this criterion for T-score MIDs. Although beyond the scope of this preliminary study, calculations of MID’s for PROMIS instruments as applied to chiropractic populations and sub-populations are feasible based upon scoring metrics for PROMIS instruments.

In the current study, up to eight to ten weeks of IASTM treatments were similar to treatment frequencies reported in previous clinical studies on IASTM (cf. Introduction). IASTM may facilitate improvements in joint and muscle function by breaking down fibrotic lesions and increasing myofascial mobility.2–5 Similarly, therapeutic effects of spinal manipulations may increase joint motion by breaking down fibrous adhesions in zygapophyseal (Z) joints as a result of separation or gapping of the Z joint articular surfaces and/or improve muscle function by altering afferent-efferent discharge patterns to reduce hypertonicity.64–67 Reductions in pain symptoms after interventions of spinal/joint manipulations and ConnecTX Therapy are consistent with these underlying mechanisms.1,12,17–19,25,64

Frictional massage and myofascial release techniques, besides "breaking down" adherent scar tissue, may involve augmentation of the inflammatory process by inducing macrotrauma to soft tissues (cf. Refs 23,33,68). This augmentation of the inflammatory process is theorized to promote proliferation and remodeling processes that may be important for the cascade of the healing process (cf. Refs. 33,35,68). In fact, the resorption of excessive fibrosis and repair and realignment of collagen fibers by immune/reparative processes may improve joint function and modulate pain responses (cf. Refs. 3,23,33,35).

It is also important to note that engaging clinicians’ perceptions related to patient-centered outcomes research is a critical factor underlying its successful implementation. Our academic clinicians had different preferences for legacy instruments and preferred to use numeric rating scales to document patient symptoms. However, patients with chronic disabling conditions reported that asking them to report symptom intensity using numeric rating scales does not capture the experience of their symptoms.69 Testing the utility of PROMIS instruments for clinical and research outcomes in chiropractic patients was important to engage our academic health center clinicians in evidence-informed discussions on valid, reliable and precise PRO instruments. Harms associated with ConnecTX Therapy were adequately documented by our clinicians.

Limitations

The case series design and the small sample size limit generalizability. Construct validity and differential item functioning (DIF) of PROMIS instruments in chiropractic patients are unknown. MID’s of PROMIS instruments are unknown. Sample size and absence of legacy instruments prevented us from addressing construct validity, DIF and MID in the current study. However, construct validity and DIF of PROMIS instruments in patients with chronic pain have been shown to be adequate.70–72

PROMIS instruments in the domain of pain allowed us to compare PRO across musculoskeletal diagnoses that that are typically treated at an academic health center of a chiropractic college. However, documenting PRO and pragmatic chiropractic care required collecting data from multiple sources. The use of Assessment Center as our data collection system required our clinicians to use a separate electronic health record for research documentation than was being used for their clinical practice documentation. The electronic health records provided limited data on the implementation of the ConnecTX Therapy, e.g. handholds or grips, instrument edges and surface radius, and treatment angles, directions, and maneuvers. Extracting information on musculoskeletal diagnoses from the electronic health records was limited to primary segmental dysfunction. Data collection of ConnecTX Therapy treatment harms required clinicians to send paper documents to the principal investigator at the completion of care.

Future Studies

ConnecTX Therapy is an adjunct modality to spinal manipulation for treating musculoskeletal disorders of the spine.37 Thus, intervention arms of future clinical trials may include spinal manipulation with and without ConnecTX Therapy for neck pain or lower back pain.73–76 The purpose of these randomized controlled trials would be to determine the additive therapeutic benefit of ConnecTX Therapy to spinal manipulative therapy. Randomized controlled trials to address the effectiveness of ConnecTX Therapy as an intervention for mild to moderate CTS would also be appropriate.77 The use of PROMIS instruments and legacy instruments for neck pain, lower back pain and CTS would allow these RCT’s to address construct validity of PROMIS instruments in chiropractic patients.

A prospective case series is being implemented among private practice chiropractors trained in ConnecTX Therapy. Documentation of interventions and harms is now a custom-made instrument (Clinician Instrument) developed within the Assessment Center for use by the private practice chiropractors. Completion of the interventions and harms documentation by chiropractors takes less than five minutes while completion of the PROMISinstruments by patients is approximately 5 minutes. Feedback from private practice chiropractors was an integral part of developing the Clinician Instrument to ensure that the time-stamp was adequate.

Within the Academic Health Centers of a Chiropractic College, PROMIS instruments in the domains of pain and physical function are now the standards for documenting PRO with ConnecTX Therapy; while, the Clinician Instrument is the standard for documenting ConnecTX Therapy and its harms. The Clinician Instrument will allow us to more precisely link the documentation of the musculoskeletal diagnoses and implementation of ConnecTX Therapy to PRO and eliminate the use of paper research records for documenting harms in future studies. External validity of PROMIS instruments for clinical and research outcomes in chiropractic patients may be assessed by comparing PRO between the academic health centers and private practice offices. Furthermore, implementation of point of care randomization within our Academic Health Centers in future studies will allow us to remove bias and confounding by indication from our observational experimental design and increase external validity.78,79

In summary, “real world” clinical settings provide another source of data for conducting rigorous clinical research.43–45 Logistic regression may be used to model factors impacting clinical outcomes, e.g. age, gender, treatment sites, diagnoses, frequency of treatments, etc. DIF and construct validity of the PROMIS instruments in chiropractic patients may be assessed (eg, 71,72). A more powerful electronic database management system that goes beyond spreadsheet capabilities is also necessary to meet our future goals of patient-centered outcomes research and ConnecTX Therapy (eg, 80).

Conclusion

Within the limitations of a case series design, the findings of this study provide initial evidence on the utility of PROMIS instruments for clinical and research outcomes in chiropractic patients.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References

- 1.Burke J., Buchberger D.J., Carey-Loghmani M.T., Dougherty P.E., Greco D.S., Dishman J.D. A pilot study comparing two manual therapy interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler S., Wilson J.K., Sevier T.L. Innovative approach for the treatment of cumulative trauma disorders. Work. 2000;15:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melham T.J., Sevier T.L., Malnofski M.J., Wilson J.K., Helfst R.H., Jr. Chronic ankle pain and fibrosis successfully treated with a new noninvasive augmented soft tissue mobilization technique (ASTM): a case report. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:801–804. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sevier T.L., Gehlsen G.M., Wilson J.K., Stover S.A., Helfst R.H. Traditional physical therapy vs graston augmented soft tissue mobilization in treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(Suppl. 5):S52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sevier T.L., Wilson J.K. Treating lateral epicondylitis. Sports Med. 1999;28:375–380. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199928050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller A.S., Miller J. A rehabilitative approach to carpal tunnel syndrome. Chiropr Prod. 1997;3:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiottz-Christensen B., Mooney V., Azad S., Selstad D., Gulick J., Bracker M. The role of active release manual therapy for upper extremity overuse syndromes—a preliminary report. J Occup Rehabil. 1999;9:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sucher B.M. Myofascial manipulative release of carpal tunnel syndrome: documentation with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1993;93:1273–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valente R., Gibson H. Chiropractic manipulation in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17:246–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christie W.S., Puhl A.A., Lucaciu O.C. Cross-frictional therapy and stretching for the treatment of palmar adhesions due to Dupuytren's contracture: a prospective case study. Man Ther. 2012;17:479–482. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black D.W. Treatment of knee arthrofibrosis and quadriceps insufficiency after patellar tendon repair: a case report including use of the graston technique. Int J Ther Massage Bodyw. 2010;3:14–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solecki T.J., Herbst E.M. Chiropractic management of a postoperative complete anterior cruciate ligament rupture using a multimodal approach: a case report. J Chiropr Med. 2011;10:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormack J.R. The management of mid-portion achilles tendinopathy with astym(R) and eccentric exercise: a case report. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7:672–677. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCormack J.R. The management of bilateral high hamstring tendinopathy with ASTYM(R) treatment and eccentric exercise: a case report. J Man Manip Ther. 2012;20:142–146. doi: 10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miners A.L., Bougie T.L. Chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a case study of treatment incorporating active and passive tissue warm-up, Graston Technique, ART, eccentric exercise, and cryotherapy. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2011;55:269–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papa J.A. Conservative management of Achilles Tendinopathy: a case report. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56:216–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White K.E. High hamstring tendinopathy in 3 female long distance runners. J Chiropr Med. 2011;10:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aspegren D., Hyde T., Miller M. Conservative treatment of a female collegiate volleyball player with costochondritis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammer W.I., Pfefer M.T. Treatment of a case of subacute lumbar compartment syndrome using the Graston technique. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papa J.A. Conservative management of a lumbar compression fracture in an osteoporotic patient: a case report. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56:29–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayliss A.J., Klene F.J., Gundeck E.L., Loghmani M.T. Treatment of a patient with post-natal chronic calf pain utilizing instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization: a case study. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19:127–134. doi: 10.1179/2042618611Y.0000000006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daniels C.J., Morrell A.P. Chiropractic management of pediatric plantar fasciitis: a case report. J Chiropr Med. 2012;11:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammer W.I. The effect of mechanical load on degenerated soft tissue. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2008;12:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howitt S., Wong J., Zabukovec S. The conservative treatment of Trigger thumb using Graston Techniques and Active Release Techniques. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2006;50:249–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howitt S., Jung S., Hammonds N. Conservative treatment of a tibialis posterior strain in a novice triathlete: a case report. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009;53:23–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudes K. Conservative management of a case of medial epicondylosis in a recreational squash player. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2011;55:26–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawson G.E., Hung L.Y., Ko G.D., Laframboise M.A. A case of pseudo-angina pectoris from a pectoralis minor trigger point caused by cross-country skiing. J Chiropr Med. 2011;10:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Looney B., Srokose T., Fernandez-de-las-Penas C., Cleland J.A. Graston instrument soft tissue mobilization and home stretching for the management of plantar heel pain: a case series. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papa J.A. Conservative management of De Quervain's stenosing tenosynovitis: a case report. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56:112–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papa J.A. Two cases of work-related lateral epicondylopathy treated with Graston Technique(R) and conservative rehabilitation. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56:192–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slaven E.J., Mathers J. Management of chronic ankle pain using joint mobilization and ASTYM(R) treatment: a case report. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19:108–112. doi: 10.1179/2042618611Y.0000000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaefer J.L., Sandrey M.A. Effects of a 4-week dynamic-balance-training program supplemented with Graston instrument-assisted soft-tissue mobilization for chronic ankle instability. J Sport Rehabil. 2012;21:313–326. doi: 10.1123/jsr.21.4.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson C.J., Ganion L.R., Gehlsen G.M., Verhoestra B., Roepke J.E., Sevier T.L. Rat tendon morphologic and functional changes resulting from soft tissue mobilization. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:313–319. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199703000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gehlsen G.M., Ganion L.R., Helfst R. Fibroblast responses to variation in soft tissue mobilization pressure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:531–535. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199904000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loghmani M.T., Warden S.J. Instrument-assisted cross-fiber massage accelerates knee ligament healing. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:506–514. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loghmani M.T., Warden S.J. Instrument-assisted cross fiber massage increases tissue perfusion and alters microvascular morphology in the vicinity of healing knee ligaments. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:240. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mollin H. New York Chiropractic College; Seneca Falls: 2012. ConnecTX therapy technique manual. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moher D., Hopewell S., Schulz K.F. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:e1–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cella D., Yount S., Rothrock N. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45:S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeWalt D.A., Rothrock N., Yount S., Stone A.A. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45:S12–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reeve B.B., Hays R.D., Bjorner J.B. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45:S22–S31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riley W.T., Rothrock N., Bruce B. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1311–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9694-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cella D., Riley W., Stone A. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gershon R.C., Rothrock N., Hanrahan R., Bass M., Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas. 2010;11:304–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gershon R., Rothrock N.E., Hanrahan R.T., Jansky L.J., Harniss M., Riley W. The development of a clinical outcomes survey research application: Assessment Center. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:677–685. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9634-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu H., Cella D., Gershon R. Representativeness of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Internet panel. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rothrock N.E., Hays R.D., Spritzer K., Yount S.E., Riley W., Cella D. Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deshpande P.R., Rajan S., Sudeepthi B.L., Abdul Nazir C.P. Patient-reported outcomes: a new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2:137–144. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.86879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fries J.F., Krishnan E. What constitutes progress in assessing patient outcomes? J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:779–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chapman J.R., Norvell D.C., Hermsmeyer J.T. Evaluating common outcomes for measuring treatment success for chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:S54–S68. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822ef74d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cleland J.A., Childs J.D., Whitman J.M. Psychometric properties of the Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with mechanical neck pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fairbank J.C., Pynsent P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine. 2000;25:2940–2952. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geere J.H., Geere J.A., Hunter P.R. Meta-analysis identifies Back Pain Questionnaire reliability influenced more by instrument than study design or population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacDermid J.C., Walton D.M., Avery S. Measurement properties of the neck disability index: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:400–417. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roland M., Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine. 2000;25:3115–3124. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schellingerhout J.M., Verhagen A.P., Heymans M.W., Koes B.W., de Vet H.C., Terwee C.B. Measurement properties of disease-specific questionnaires in patients with neck pain: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:659–670. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9965-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young B.A., Walker M.J., Strunce J.B., Boyles R.E., Whitman J.M., Childs J.D. Responsiveness of the Neck Disability Index in patients with mechanical neck disorders. Spine J. 2009;9:802–808. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young I.A., Cleland J.A., Michener L.A., Brown C. Reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness of the neck disability index, patient-specific functional scale, and numeric pain rating scale in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89:831–839. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181ec98e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sprinthall R.C. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2007. Basic statistical analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yost K.J., Eton D.T., Garcia S.F., Cella D. Minimally important differences were estimated for six Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nyiendo J., Haas M., Goldberg B., Sexton G. Patient characteristics and physicians' practice activities for patients with chronic low back pain: a practice-based study of primary care and chiropractic physicians. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:92–100. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2001.112565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nyiendo J., Haas M., Goldberg B., Sexton G. Pain, disability, and satisfaction outcomes and predictors of outcomes: a practice-based study of chronic low back pain patients attending primary care and chiropractic physicians. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharma R., Haas M., Stano M., Spegman A., Gehring R. Determinants of costs and pain improvement for medical and chiropractic care of low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cramer G.D., Cambron J., Cantu J.A. Magnetic resonance imaging zygapophyseal joint space changes (gapping) in low back pain patients following spinal manipulation and side-posture positioning: a randomized controlled mechanisms trial with blinding. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36:203–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dishman J.D., Burke J. Spinal reflex excitability changes after cervical and lumbar spinal manipulation: a comparative study. Spine J. 2003;3:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(02)00587-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dishman J.D., Dougherty P.E., Burke J.R. Evaluation of the effect of postural perturbation on motoneuronal activity following various methods of lumbar spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2005;5:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dishman J.D., Weber K.A., Corbin R.L., Burke J.R. Understanding inhibitory mechanisms of lumbar spinal manipulation using H-reflex and F-wave responses: A methodological approach. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;210:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perle S.M., Lawson G. Stimulating healing by initiating inflammatory response. Can Chiropr. 2004;9:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yorkston K.M., Johnson K., Boesflug E., Skala J., Amtmann D. Communicating about the experience of pain and fatigue in disability. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:243–251. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9572-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chung H., Kim J., Cook K.F., Askew R.L., Revicki D.A., Amtmann D. Testing measurement invariance of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system pain behaviors score between the US general population sample and a sample of individuals with chronic pain. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:239–244. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0463-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cook K.F., Bamer A.M., Amtmann D., Molton I.R., Jensen M.P. Six patient-reported outcome measurement information system short form measures have negligible age- or diagnosis-related differential item functioning in individuals with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1289–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khanna D., Maranian P., Rothrock N. Feasibility and construct validity of PROMIS and "legacy" instruments in an academic scleroderma clinic. Value Health. 2012;15:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bronfort G., Evans R., Anderson A.V., Svendsen K.H., Bracha Y., Grimm R.H. Spinal manipulation, medication, or home exercise with advice for acute and subacute neck pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:1–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bronfort G., Maiers M.J., Evans R.L. Supervised exercise, spinal manipulation, and home exercise for chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine J. 2011;11:585–598. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Evans R., Bronfort G., Schulz C. Supervised exercise with and without spinal manipulation performs similarly and better than home exercise for chronic neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:903–914. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31823b3bdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mieritz R.M., Hartvigsen J., Boyle E., Jakobsen M.D., Aagaard P., Bronfort G. Lumbar motion changes in chronic low back pain patients. Spine J. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.038. [Epub ahead of print March 6, 2014] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Page M.J., O'Connor D., Pitt V., Massy-Westropp N. Exercise and mobilisation interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD009899. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.D'Avolio L., Ferguson R., Goryachev S. Implementation of the Department of Veterans Affairs' first point-of-care clinical trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19:e170–e176. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sica G.T. Bias in research studies. Radiology. 2006;238:780–789. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2383041109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]