Abstract

In order to investigate the conformational dynamics of human DNA polymerase κ (hpol κ), we generated two mutants, Y50W (N-clasp region) and Y408W (linker between the thumb and little finger domains), using a Trp-null mutant (W214Y/W392H) of the hpol κ catalytic core enzyme. These mutants retained catalytic activity and similar patterns of selectivity for bypassing the DNA adduct 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxoG), as judged by the results of steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic experiments. Stopped-flow kinetic assays with hpol κ Y50W and T408W revealed a decrease in Trp fluorescence with the template G:dCTP pair but not for any mispairs. This decrease in fluorescence was not rate-limiting and is considered to be related to a conformational change necessary for correct nucleotidyl transfer. When a free 3′-hydroxyl was present on the primer, the Trp fluorescence returned to the baseline level at a rate similar to the observed kcat, suggesting that this change occurs during or after nucleotidyl transfer. However, polymerization rates (kpol) of extended-product formation were fast, indicating that the slow fluorescence step follows phosphodiester bond formation and is rate-limiting. Pyrophosphate formation and release were fast and are likely to precede the slower relaxation step. The available kinetic data were used to fit a simplified minimal model. The extracted rate constants confirmed that the conformational change after phosphodiester formation was rate-limiting for hpol κ catalysis with the template G:dCTP pair.

Keywords: DNA polymerase, translesion synthesis, DNA replication, enzyme kinetics, conformational change

Introduction

DNA is subjected to constant damage from both endogenous and exogenous sources, with an estimated 50,000–100,000 modifications per cell each day [1, 2]. Cells have several mechanisms that impart a protective effect, including >100 genes involved in DNA repair [3], a complex series of downstream DNA damage response cascades to stop replication [4], and a battery of specialized DNA polymerases to navigate replication past sites of damage [5]. This latter group, the so-called translesion (TLS) DNA polymerases, has been intensively studied following their discovery 15 years ago [3, 5].

The TLS DNA polymerases were first studied in bacterial systems [6], ultimately leading to an understanding of the SOS adaptive response [3, 7–11]. These polymerases function in copying past sites of damaged DNA, and their significance is clearly demonstrated by the finding that a human disease xeroderma pigmentosum variant is related to a deficiency in pol η [12]. The TLS pols enable bypass of lesions, but inherently they have low fidelity and cannot copy long regions of DNA without introducing errors [2]. Many of the “bypass” events involving “switching” of the replicative and TLS DNA polymerases are still unclear. Further, the catalytic selectivity of TLS polymerases for DNA lesions, their cellular regulation, and protein expression levels in individual cells remain largely unexplored.

Human DNA polymerase kappa (hpol κ) was first reported to be a homologue of the dinB gene of Escherichia coli [13] (first termed pol θ in that work, later changed to pol κ). hpol κ accommodates DNA lesions during catalysis [14, 15], including a series of N2-alkyl guanine derivatives ranging in size from methyl to methylene-benzo[a]pyrenyl [16]. Interestingly, dCTP is inserted with good fidelity in all of these cases. Notably, recent experiments monitoring plasmid replication in human cells have shown that hpol κ contributes to the error-prone DNA bypass of 8-oxoG [17], one of the most prevalent endogenous DNA modifications in cells [1]. In vitro kinetic studies have shown that recombinant hpol κ preferentially inserts dATP opposite 8-oxoG [18, 19]. Crystal structures of hpol κ bound to 8-oxoG-containing templates revealed that the lesion is stabilized in the syn orientation through interactions with Leu-508, forming a Hoogsteen-like base pair with the incoming dATP [19]. Moreover, hpol κ lacks electrostatic contacts in the little finger domain to stabilize 8-oxoG in the anti conformation, as observed for other Y-family pols, including Sulfolobus solfataricus Dpo4 [20, 21].

A minimal kinetic model has been proposed for general DNA polymerase catalysis (Scheme 1) [22–26]. The model Y-family DNA polymerase S. solfataricus Dpo4 has been extensively studied and is thought to adopt additional kinetic steps beyond the minimal kinetic scheme to accommodate different DNA damage structures [27, 28]. The catalytic mechanism of hpol κ is assumed to follow the general course developed mainly with a series of viral, bacterial, and archaebacterial DNA polymerases [27, 29]. However, limited studies on the kinetics and mechanisms of mammalian DNA polymerases have been done and many questions remain. Do mammalian TLS polymerases use an induced-fit mechanism? Are conformational changes involved? Which step is rate-limiting? How are these mechanisms perturbed by DNA adducts?

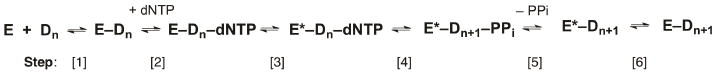

Scheme 1.

Minimal kinetic model for DNA polymerase catalysis.

One powerful approach to understand the polymerase conformational dynamics is the use of fluorescence to monitor structural changes. Different fluorescent tags have been used to label DNA or polymerases and used to gain mechanistic insights [30–32]. A number of studies have utilized fluorescence labels in the nucleoside triphosphate or oligonucleotide (e.g. 2-aminopurine) [33–36]. Others have used artificial fluorophores covalently linked to proteins, usually at Cys residues [23]. The former has a disadvantage in that they may not be reporting changes in the protein, instead reflecting base pairing, base stacking, etc. The latter approach for protein modification usually involves organic solvents, which may cause the loss of enzyme activity, and thus requires further protein purification. We have preferred to substitute smaller Trp residues at strategic sites in DNA polymerases. Previously we generated Trp mutants for Dpo4 and successfully observed a fast conformational change prior to the nucleotidyl transfer and a slow conformational relaxation following the phosphodiester bond formation [27], despite the fact that this approach may require considerable effort to screen mutants to identify those that maintain proper catalytic activities. Here we used similar strategies to probe the conformational dynamics of hpol κ. We generated two catalytic active Trp mutants Y50W (N-clasp region) and Y408W (linker between the thumb and little finger domains) using a Trp-null mutant (W214Y/W392H) of the hpol κ catalytic core enzyme (Fig. 1). We demonstrated that these mutants resemble WT hpol κ in catalytic efficiencies and fidelity using a series of steady-state and pre-steady-state experiments. These mutants were then utilized in stopped-flow fluorescence experiments to extract microscopic rates and rate constants pertaining to hpol κ conformational changes. The obtained data were globally fit to a kinetic model to extract several constants that were experimentally difficult to measure. A slow conformational change after the nucleotidyl transfer was found to be the rate-limiting step for hpol κ catalysis, providing the first evidence that a conformational change, as rate-limiting step, happens during human translesion DNA polymerase catalysis.

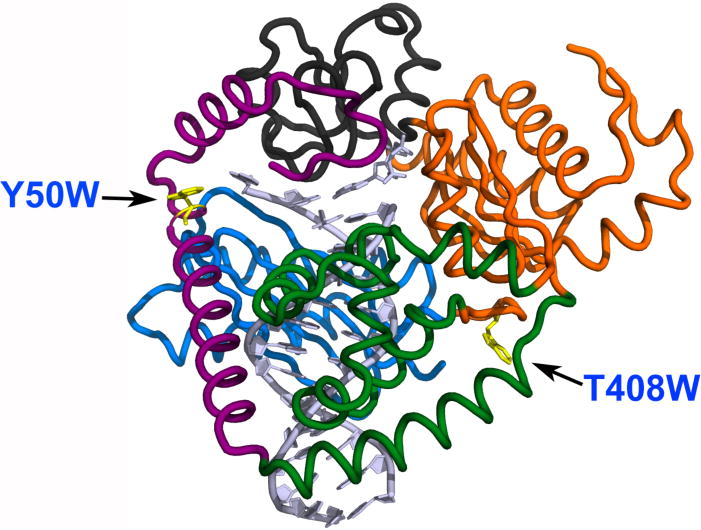

Fig. 1.

Structure of hpol κ (adapted from PDB: 2W7P)[19] with mutated residues indicated. The two mutations, Y50W (located in the N-clasp domain) and T408W (located at the linker region between the thumb and palm domains), are shown as yellow residues.

Results

Construction of hpol κ Trp mutants

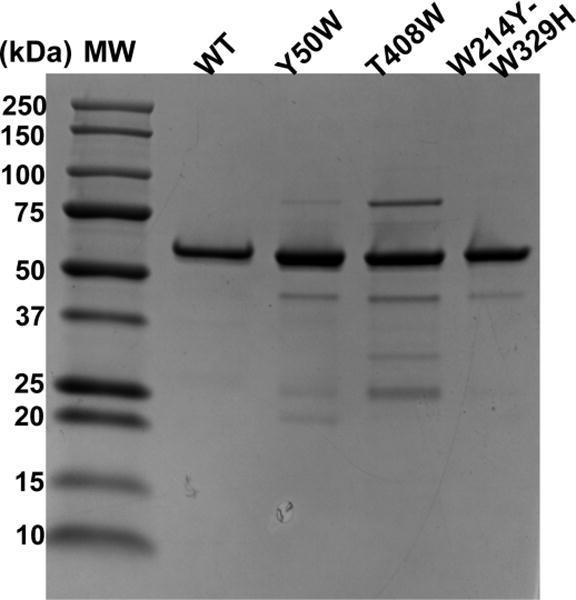

In order to elucidate hpol κ conformational dynamics, we constructed a series of Trp mutants for stopped-flow fluorescence measurements, as successfully used with Dpo4 [27]. Wild-type hpol κ19–526 contains only two Trp residues, i.e. Trp-214 and Trp-392, located in the palm and thumb domains, respectively. To determine if these Trp residues could be eliminated without affecting the catalytic function of hpol κ, we first constructed a mutant without any Trp residues—W214Y/W392H—to avoid fluorescence signal complications from multiple Trp residues. This mutant W214Y/W392H was expressed in E. coli and purified, and showed similar catalytic efficiency in steady-state kinetic and pre-steady-state burst kinetic analyses (vide infra). Based on the positions of the two Trp residues, Trp-214 and Trp-392, in existing crystal structures [19], we further introduced single Trp residues to each mutant using W214Y/W392H as a background, and expressed and purified several mutants, i.e. L21W, L31W, Y50W, and T408W. The Trp residues in the first three mutants are located in the N-clasp domain and for T408W, the Trp is located at the linker region between the thumb and palm domains (Fig. 1). Of these mutants, Y50W and T408W possessed similar catalytic performance compared to WT hpol κ, as demonstrated using a series of steady-state and pre-steady-state experiments, and were chosen for further stopped-flow fluorescence investigations (vide infra). The WT hpol κ and mutant enzymes were ≥ 85% pure as judged by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis of purified WT hpol κ and mutant enzymes. Mr: molecular mass standards.

Steady-state kinetics

Steady-state kinetic assays were performed to compare the catalytic efficiencies of WT hpol κ and the mutants using 36-mer templates containing either G or the DNA adduct 8-oxoG (oligonucleotide sequences summarized in Table 1). For dCTP insertion opposite template G, WT hpol κ and the three mutants showed similar specificities (kcat/Km within a factor of 3.7, Table 2), indicating that eliminating (W214Y/W392H) or introducing Trp (Y50W and T408W) at the indicated positions did not have a major effect on the catalytic specificity of hpol κ. However, two other Trp mutants (L21W and L31W, data not shown) made on the W214Y/W392H background did not yield acceptable specificities and were not pursued further. Both full-length hpol κ and core hpol κ (residues 19–526) are known to replicate through 8-oxoG in an error-prone fashion, mis-inserting dATP up to 10-fold more efficiently than the correct dCTP [19, 37, 38]. To confirm that mutants preserved the same pattern for translesion synthesis, we compared nucleotide incorporations opposite 8-oxoG using both WT hpol κ and mutants. For the change of specificity of inserting dCTP opposite 8-oxoG compared to inserting dCTP opposite unmodified G, the mutants W214Y/W392H, Y50W, and T408W, showed 30-, 15-, and 26-fold attenuation, respectively, whereas WT hpol κ showed an 8-fold decrease (Table 2). No appreciable changes in specificity were observed for the incorrect base dATP incorporation, i.e. about 3-fold attenuation for three mutants and WT hpol κ. Two mutants used in further studies, Y50W and T408W, showed similar trends in specificity constants as WT hpol κ (Table 2), in the order G:dCTP > 8-oxoG:dATP > 8-oxoG:dCTP, with the ratio of the latter two efficiencies being in the range of 6 to 7, compared to 3 for WT hpol κ. Thus, the two mutants Y50W and T408W maintained a similar fidelity pattern compared to WT pol κ

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in the current study. X denotes 2′-deoxyguanosine (G) or 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxoG).

| Name | Sequences |

|---|---|

| 24-mer (primer) | 5′–GCCTCGAGCCAGCCGCAGACGCAC–3′ |

| 36-mer (template) | 5′–TCGGCGTCCTAXGTGCGTCTGCGGCTGGCTCGAGGC–3′ |

| 13-mer-Cdd (primer) | 5′–GGGGGAAGGATTCdd–3′ |

| 18-mer (template) | 5′–TCACGGAATCCTTCCCCC–3′ |

Table 2.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of hpol κ and mutant-catalyzed single-base insertion opposite the base X in a 24/36-mer duplex (see Table. 1 for sequence)

| hpol κ | Template: dNTP pair |

kcat (s−1) |

Km,dNTP (μM) |

kcat/Km,dNTP (μM−1 s−1) |

Change of specificity relative to G:C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | G:C | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 0.52 ± 0.37 | 0.019 | – |

| 8-oxoG:C | 0.0076 ± 0.0008 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 0.0024 | 8-fold lower | |

| 8-oxoG:A | 0.012 ± 0.002 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.0071 | 3-fold lower | |

|

| |||||

| W214Y/W392H | G:C | 0.017 ± 0.003 | 1.7 ± 0.05 | 0.010 | – |

| 8-oxoG:C | 0.010 ± 0.002 | 33 ± 16 | 0.00033 | 30-fold lower | |

| 8-oxoG:A | 0.0125 ± 0.0017 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 0.0038 | 2.6-fold lower | |

|

| |||||

| Y50W | G:C | 0.025 ± 0.002 | 0.67 ± 0.20 | 0.037 | – |

| 8-oxoG:C | 0.0092 ± 0.0005 | 3.8 ± 0.94 | 0.0024 | 15-fold lower | |

| 8-oxoG:A | 0.010 ± 0.003 | 0.81 ± 0.33 | 0.012 | 3.1-fold lower | |

|

| |||||

| T408W | G:C | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 1.3 ± 0.34 | 0.013 | – |

| 8-oxoG:C | 0.0040 ± 0.0003 | 7.4 ± 2.4 | 0.0005 | 26-fold lower | |

| 8-oxoG:A | 0.0042 ± 0.0003 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.0038 | 3.4-fold lower | |

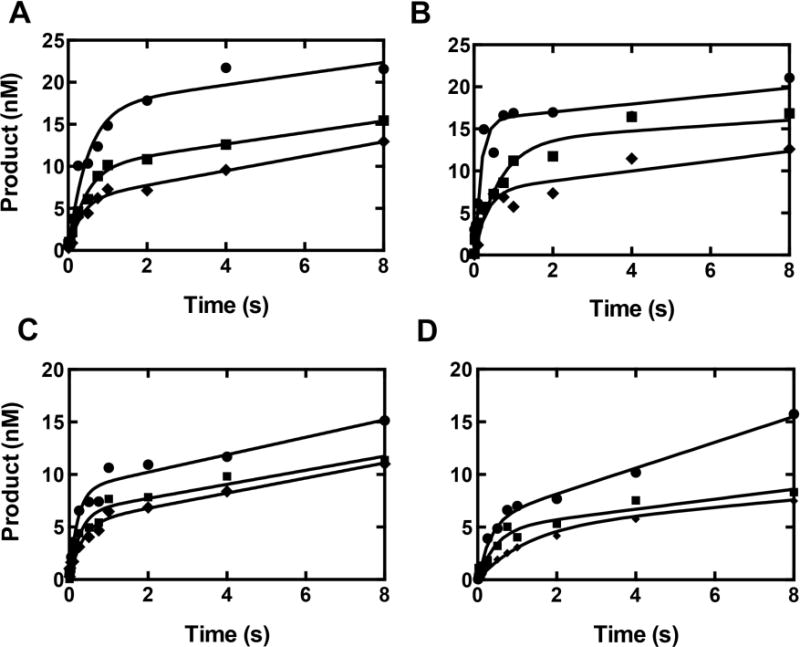

Pre-steady-state burst kinetics

Kinetic parameters obtained by steady-state analysis are complex functions of rate constants of multiple steps leading to products (Scheme 1). On the other hand, pre-steady-state kinetic techniques are powerful in dissecting complex mechanisms and measuring kinetics of an individual step (or several steps combined) along the pathway [22, 39]. Pre-steady-state burst kinetics under enzyme-limiting conditions reveal the transient concentration of a kinetically active ternary complex [24]. We examined burst kinetics for WT hpol κ and three mutants using 24/36-mer duplexes containing G or 8-oxoG (see Table 1 for sequences). For insertion of dCTP opposite unmodified G, WT and W214Y/W392H hpol κ exhibited burst amplitudes of 68% and 64%, respectively, similar to (a previous study with purified) full-length hpol κ and its catalytic core (Fig. 2 and Table 3) [16, 19, 40]. Although mutants Y50W and T408W showed slightly lower burst amplitudes than WT hpol κ (i.e., 57% for Y50W and 41% for T408W) possibly due to the small decrease in enzyme activity or the presence of non-productive complexes, the burst and steady-state rates were similar for WT and the mutants for insertion of dCTP opposite G (within a factor of two), indicating that the catalytically active components of two mutants have similar efficiencies replicating through unmodified G. In the case of error-free insertion of dCTP opposite 8-oxoG, WT hpol κ and W214Y/W392H showed 2- to 3-fold lower amplitudes compared to the corresponding template G:dCTP pair, suggesting the presence of non-processive enzyme-DNA complexes in the case of translesion synthesis through 8-oxoG [41]. Minor decreases in amplitudes were observed for Y50W and T408W compared to G:dCTP pair by these two mutants. The burst amplitudes for mis-insertion of dATP opposite 8-oxoG were almost two-fold higher than those for the G:dCTP pair with WT and W214Y/W392H hpol κ and were equal or slightly higher for Y50W and T408W. Regardless of the change in product amplitudes, burst and steady-state rates were comparable for all three mutants compared to WT hpol κ for each base pair, in agreement with the similar kcat values seen in steady-state kinetic results (Table 2).

Table 3.

Summary of pre-steady-state burst kinetics results for hpol κ and mutants. Each reaction was performed under enzyme-limiting conditions by rapid mixing of 100 nM 24/36-mer DNA substrate and hpol κ with 1 mM dNTP in the presence of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 3 mM DTT, 50 μg BSA ml−1, and 5% (v/v) glycerol at 23 °C. The final enzyme concentrations after mixing for each set of reaction were 25 nM for WT hpol κ, 25 nM for W214Y/W392H, 15 nM for Y50W, and 14 nM for T408W. Results were obtained by fitting data to Eq. 1. (see Fig. 2)

| hpol κ | Template base:dNTP pair |

kobs s−1 |

kss s−1 |

Aa nM |

[pol-DNA]active/[pol]total% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | G:C | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 0.027 ± 0.012 | 17 ± 2 | 68 |

| 8-oxoG:C | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 0.034 ± 0.004 | 6 ± 1 | 24 | |

| 8-oxoG:A | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 0.028 ± 0.006 | 10 ± 1 | 40 | |

|

| |||||

| W214Y/W392H | G:C | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 0.019 ± 0.002 | 16 ± 1 | 64 |

| 8-oxoG:C | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 0.024 ± 0.002 | 8 ± 1 | 32 | |

| 8-oxoG:A | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.014 ± 0.004 | 14 ± 1 | 56 | |

|

| |||||

| Y50W | G:C | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 0.033 ± 0.005 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 57 |

| 8-oxoG:C | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 0.029 ± 0.004 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 36 | |

| 8-oxoG:A | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 0.027 ± 0.005 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 42 | |

|

| |||||

| T408W | G:C | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 0.048 ± 0.004 | 5.7± 0.5 | 41 |

| 8-oxoG:C | 0.82 ± 0.14 | 0.014 ± 0.001 | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 34 | |

| 8-oxoG:A | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0.019 ± 0.005 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 34 | |

A is the product amplitude.

Determination of Kd,dNTP and kpol for Insertion Opposite G and 8-oxoG

To estimate the maximal rate of nucleotide incorporation (kpol) and the apparent constant for nucleotide dissociation from the kinetically active ternary complex (Kd,dNTP,app), Y50W was examined and compared with WT hpol κ reported previously. The experimentally determined kpol contains contributions from the rate of both the conformational change (before phosphodiester bond formation) and the nucleotidyl transfer itself (steps 3 and 4 in Scheme 1) [24, 42]. For Y50W, kpol values for incorporation of C opposite G, C opposite 8-oxoG, and A opposite 8-oxoG were 1.4 (± 0.1) s−1, 1.3 (± 0.2) s−1, and 1.6 (± 0.2) s−1, respectively, obtained from conventional data analysis (Table 4). Actual curves are shown in Fig. 9C (vide infra). We observed decreases in the kpol and Kd,dNTP,app values compared to those previously reported for WT hpol κ (Table 4) [19]. The ratio of kpol/Kd,dNTP,app, often defined as catalytic efficiency, was determined from these experiments. Notably, despite the lower absolute values of kpol and Kd,dNTP,app seen for Y50W compared to WT hpol κ, Y50W yielded overall higher catalytic efficiencies. Consistent with the aforementioned steady-state and pre-steady-state burst analyses, Y50W mis-inserted dATP opposite 8-oxoG with a similar efficiency compared to the efficiency of insertion of dCTP opposite G, whereas correct dCTP incorporation occurred approximately 20-fold less efficiently, which is the same pattern observed for WT hpol κ. Together, Y50W showed similar or slightly higher catalytic efficiencies replicating through G or 8-oxoG.

Table 4.

Pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of single-turnover DNA polymerase assays under enzyme excess conditions. Data were obtained by rapid mixing of 1.5 μM Y50W, 50 nM 24/36-mer DNA substrate, 3 mM DTT, 50 μg BSA ml−1, and 5% (v/v) glycerol with dNTP concentrations from 0.1 to 200 μM. Actual results are shown in Fig. 7C. Data were fit to Eq. 2 to extract the maximal rate constant for single nucleotide incorporation (kpol) and the apparent constant of nucleotide dissociation from kinetically active ternary complex (Kd,dNTP,app).

| hpol κ | Template base:dNTP pair |

kpol s−1 |

Kd,dNTP,app μM |

kpol/ Kd,dNTP,app μM−1 s−1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTa | G:C | 10 ± 1 | 36 ± 14 | 0.28 | |

| 8-oxoG:C | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 90 ± 35 | 0.0044 | ||

| 8-oxoG:A | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 13 ± 3 | 0.63 | ||

|

| |||||

| Y50W | G:C | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.5 | |

| 8-oxoG:C | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 17 ± 7 | 0.076 | ||

| 8-oxoG:A | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.81 ± 0.39 | 2.0 | ||

Data were from ref. [19].

Fig. 9.

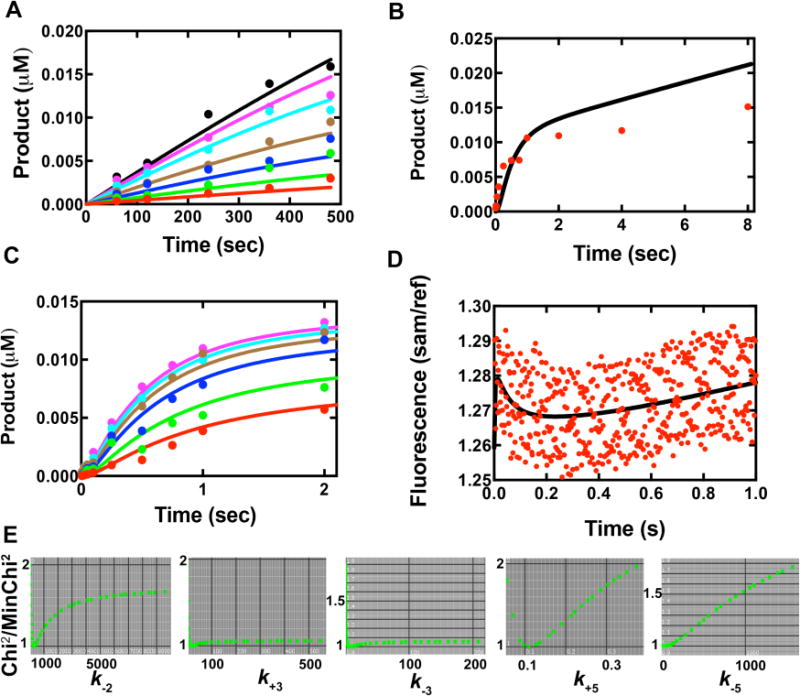

Global fit of multiple data sets to the simplified kinetic model in Scheme 2. Colored dots represent actual data and curves are from global fitting. (A) Steady-state kinetic results of Y50W inserting dCTP opposite template G. The concentrations of dCTP in different sets were 0.1 μM (red), 0.2 μM (green), 0.4 μM (blue), 0.8 μM (brown), 2 μM (cyan), 4 μM (purple) and 8 μM (black). (B) Pre-steady-state burst kinetics of Y50W under enzyme limiting conditions. The reaction contained 0.05 μM DNAG and 0.025 μM Y50W with 500 μM dCTP. (C) Concentration dependence of dCTP incorporation under single turnover conditions. Data were from rapid quench data, acquired using 0.025 μM DNA and 0.75 μM Y50W at varying dCTP concentrations, i.e. 0.5 μM (red), 1.0 μM (green), 2.5 μM (blue), 5.0 μM (brown), 10 μM (cyan), and 25 μM (purple). (D) Stopped-flow fluorescence changes of Y50W (1 μM) upon dCTP (10 μM) binding in the presence of 24-/36-mer duplex (1.05 μM). (E) 1-D FitSpace evaluation of kinetic simulation. Chi2 threshold limit 2; resolution of grid 20; parameter multiple minimum (lower bound) 0.0001; parameter multiple maximum (upper bound) 32.

Determination of Kd,DNA and koff,DNA

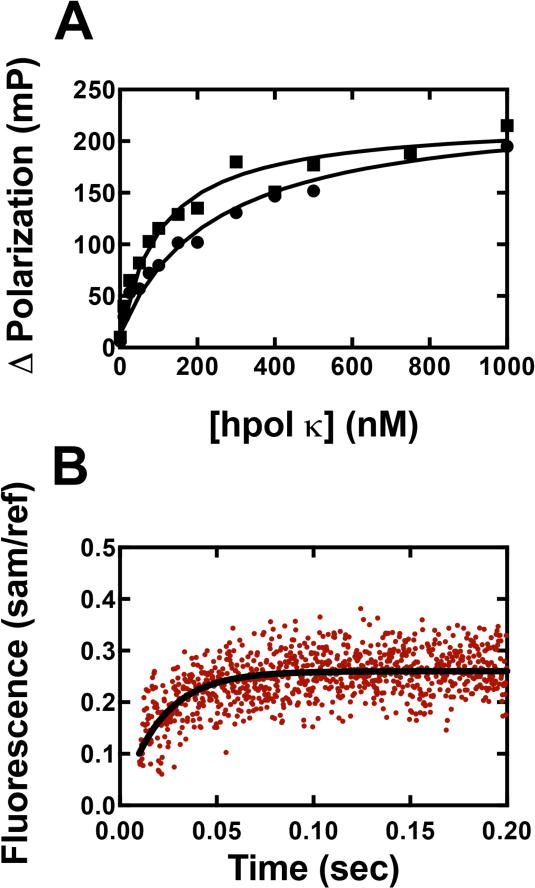

Fluorescence anisotropy assays were performed to estimate the dissociation constants of hpol κ-DNA complexes. We obtained Kd,DNA values of 100 (±20) and 240 (±30) nM for Y50W and WT hpol κ, respectively (Fig. 4A). The latter value for WT hpol κ (residues 19–526) is in agreement with a reported value of 168 (±9) nM [43]. The off-rate for enzyme dissociation from the hpol κ-DNA complex was estimated using a 24-/36-mer duplex containing G in the template and a fluorescein label on the primer mixed with an excess amount of unmodified 24-/36-mer duplex. The fluorescence change was recorded upon mixing the two solutions using a stopped-flow apparatus, and the resulting fluorescence change (Fig. 4B) was a fit to a single-exponential equation (Eq. 2) to obtain a koff,DNA (k−1, Scheme 2) value of 48 (±2) s−1. Thus kon,DNA (k1, Scheme 2) can be calculated using koff,DNA/Kd,DNA, which gives kon,DNA = 4.8 × 108 M−1 s−1, a typical value for a diffusion–limited process.

Fig. 4.

Determination of Kd,DNA and koff,DNA. (A) Fluorescence anisotropy experiments for determination of Kd,DNA. A FAM-labeled 24-/36-mer duplex (2 nM) was incubated with varying concentrations of hpol κ or Y50W (0 to 1 μM), and fluorescence polarization was measured. All titrations were performed in 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1 mg mL−1 BSA. Results were analyzed using eq. 4 and eq. 5 to obtain 100 (± 20) μM and 240 (± 30) for Y50W (■) and WT hpol κ (●), respectively. (B) Fluorescence change (red dots) measured (stopped-flow) upon mixing a pre-formed complex of WT hpol κ (2 μM):FAM-labeled 24-/36-mer duplex (0.4 μM) with a regular 24-/36-mer duplex (2 μM) (used as a trap). Experiments were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8 at 25 °C) containing 50 mM NaCl and 5 mM DTT. The excitation wavelength was 485 nm with an emission wavelength 515 nm cutoff (long-pass) filter (Newport, Irvine, CA) and a 1 mm slit width. The resulted fluorescence change was fitted to a single exponential equation (fit shown with black curve) to obtain koff,DNA = 48 (±2) s−1.

Scheme 2.

A simplified minimal kinetic model for human DNA polymerase κ catalysis.

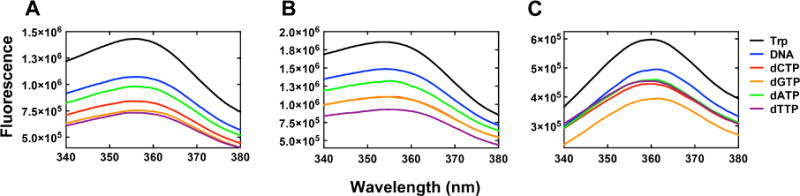

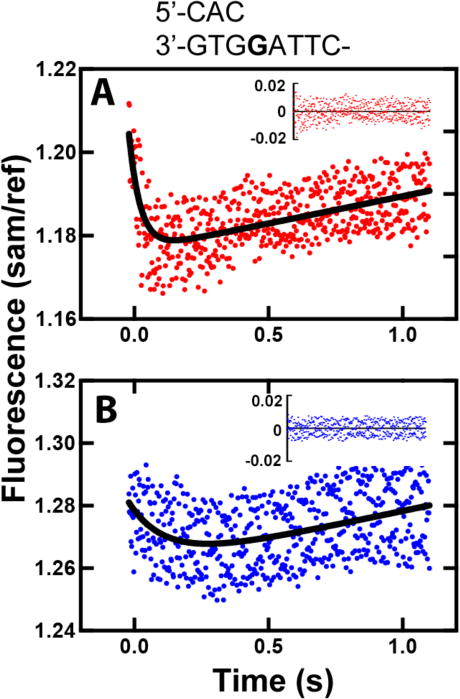

Stopped-flow measurement of hpol κ conformational changes

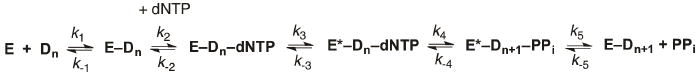

Monitoring Trp fluorescence changes using stopped-flow techniques has been proven to be useful in extracting information from microscopic steps pertaining to protein conformational changes. Single Trp residue in Y50W or T408W can serve as a fluorescence probe to understand hpol κ conformational dynamics. We first collected steady-state fluorescence spectra for the two Trp mutants using a DNA duplex containing a dideoxy-terminated primer (Table 1, 13-mer-Cdd/18-mer) to avoid complications from changes occurring during polymerization. The fluorescence intensity decreased upon addition of the oligonucleotide and further decreased upon addition of dNTPs with both mutants (Fig. 5A and 5B). This decrease in fluorescence may be the result of an inner filter effect because (i) all of the four dNTPs caused some attenuation of fluorescence and (ii) similar decreases were seen when the oligonucleotides and dNTPs were added to the free amino acid tryptophan (Fig. 5C). Because inner filter effects are immediate and not time-dependent, we examined the selectivity using stopped-flow kinetics (Fig. 6). Both Y50W and T408W showed a time-dependent fluorescence decrease only in the presence of correct base pair formation (Fig. 6A and 6E), indicating that the fluorescence decrease observed in the stopped-flow experiment was not attributable to an inner filter effect. The fluorescence changes were approximately one-half of those observed with Dpo4 [27]. The smaller changes observed here with hpol κ may be due to the inherent rigidity of the enzyme.

Fig. 5.

Steady-state fluorescence spectra for 1 μM Y50W (A) or 1 μM T408W (B) mutants, titrating with a 1 μM double-stranded oligonucleotide containing a dideoxy-termininated primer (Table 1, 13-mer-Cdd/18-mer) and 250 μM of each dNTP in 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5 at 23 °C). (C) Spectra for free amino acid tryptophan titrated with DNA duplex (Table 1, 13-mer-Cdd/18-mer) and dNTPs at concentrations indicated above.

Fig. 6.

Fluorescence changes of hpol κ mutants T408W and Y50W observed upon dCTP binding to a 13-mer-Cdd/18-mer duplex. Stopped-flow fluorescence measurements were done using an excitation wavelength of 290 nm and an Oriel 350 nm bandpass filter to examine the specificity of the fluorescence changes occurring upon dNTP addition to a pre-formed enzyme-oligonucleotide duplex complex. (A–D) Mutant Y50W; (E–H) mutant Y408W. In each case the DNA polymerase (2 μM hpol κ, in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5) was mixed with an equal volume of either the same buffer alone (blank, black trace) or containing a 25 μM concentration of the indicated dNTP. (A, E): dCTP (red); (B, F): dGTP (yellow); (C, G): dATP (green); (D, H): dTTP (purple).

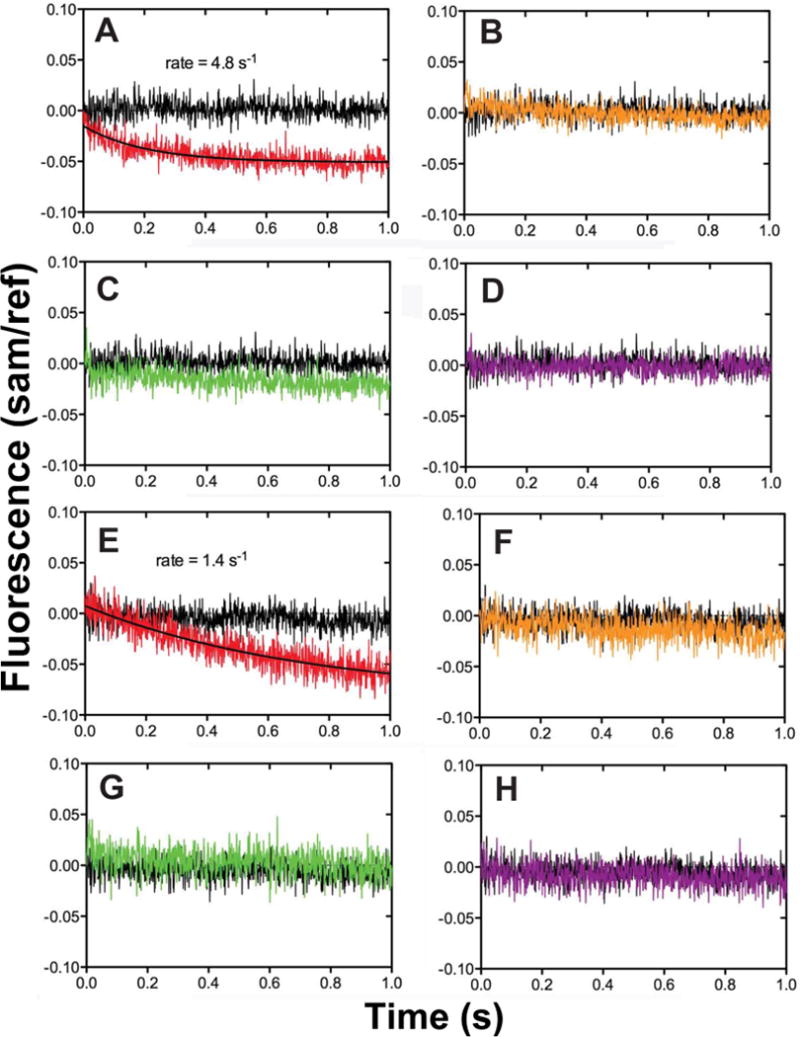

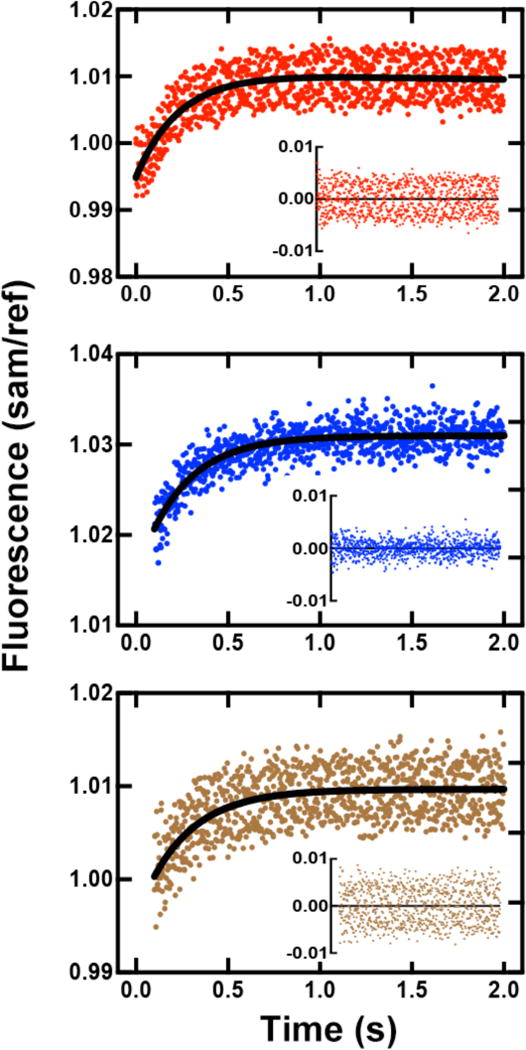

In the presence of nucleotidyl transfer, a fast decrease in fluorescence intensity was observed, followed by a slow return to the baseline fluorescence intensity, for both Y50W and T408W (Fig. 7), upon mixing of a pre-formed binary complex of hpol κ mutant and 24-/36-mer duplex with various concentrations of dCTP. By fitting data to a double-exponential model in OLIS Global Works, we estimated the fast-phase rate constants to be 6.7 (± 1) s−1 for Y50W and 23 (± 1) s−1 for T408W. Rate constants of the slow phase were 0.014 (± 0.002) s−1 for Y50W, and 0.011 (± 0.001) s−1 for T408W, on the order of the kcat (describing a summation of individual rate constants reflecting an overall rate of catalysis). We attribute the fast decrease to conformational changes associated with nucleotide binding (step 3 in Scheme 1), because such a decrease with a similar rate (4.8 s−1 for Y50W, Fig. 4A) was also observed without the nucleotidyl transfer. The slow increase was only seen in the presence of nucleotidyl transfer (steps 4 and onwards in Scheme 1), and the rates of this slow increase for both Y50W and T408W were similar to the observed kcat in steady-state kinetics, which together suggest that this change occurs during or after nucleotidyl transfer. However, under single turn-over conditions (vide supra), a kpol value of 1.4 (± 0.1) s−1 for template G:dCTP for Y50W reports the rate of the slowest step up to and including chemistry (steps 3 and 4 in Scheme 1), and was much higher than the rate of the slow increase (0.014 ± 0.002 s−1), suggesting that a step after the phosphoryl transfer (i.e. step 4 in Scheme 1), instead of that chemistry itself, is rate-limiting. Notably, the similar fluorescence profiles seen with both mutants suggest an overall “global” conformational change rather than localized changes in specific domains, e.g. the N-clasp region of hpol κ, as suggested by others with Dpo4 [31].

Fig. 7.

Fluorescence changes of hpol κ mutants T408W and Y50W observed upon dCTP binding to a pre-formed 24-/36-mer duplex-hpol κ complex (X is G). Fluorescence changes were recorded upon mixing of a pre-formed mixture of 1 μM Y50W and 1.1 μM DNA duplex with 100 μM dCTP in the presence of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM NaCl at 23 °C (final concentrations after mixing). Data were fit to a double-exponential model in OLIS Global Works (black curve). (A) T408W-DNA was mixed with 100 μM dCTP; fast and slow phase rates were 23 ± 1 s−1 and 0.011 ± 0.001 s−1, respectively. (B) Y50W-DNA was mixed with 10 μM dCTP; fast and slow phase rates were 6.7 ± 1 s−1 and 0.014 ± 0.002 s−1, respectively. Residuals are shown in the insets.

Stopped-flow measurement of PPi release

Based on work with Dpo4 [24], we hypothesized that PPi release is too fast to be rate-limiting. To further investigate whether this is the case with hpol κ, we utilized a previously developed system to measure the rate of PPi release by monitoring the fluorescence change resulted from hydrolyzed PPi (to Pi) binding to PBP-MDCC using stopped-flow methods [27, 44]. Upon mixing of a pre-formed binary complex of Y50W and 24-/36-mer duplex with dCTP, PPi was released (due to catalysis by Y50W) and then rapidly hydrolyzed by an excess of PPase. The resulting Pi bound to PBP-MDCC, causing a rapid conformational change, can be monitored fluorimetrically, as evidenced by the rapid fluorescence increase seen in Fig. 8. The observed rate for the fluorescence change indicative of Pi binding was 4.7 (± 0.4) s−1 (for the template G:dCTP pair, Fig. 6A). This value can be compared to the burst rate of 4.7 (± 1.0) s−1 for product formation obtained under similar conditions (Table 2). Although the actual rate of PPi release (step 5 in Scheme 1) was not revealed in such experiments, an estimated a lower limit on the rate of PPi release can be set at approximately 25 s−1, 5-fold higher than the observed rate [45], indicating that PPi release cannot be rate-limiting. For Y50W catalyzed incorporation of dATP or dCTP opposite 8-oxoG, similar rates were obtained: 4.0 (± 0.3) s−1 for 8-oxoG:dCTP (Fig. 6B) and 3.7 (± 0.6) s−1 for 8-oxoG:dATP (Fig. 6C). These values are also comparable to burst rates in Table 3, indicating that PPi release is not the rate-limiting step during tranlesion synthesis across 8-oxoG.

Fig. 8.

Estimation of rates of PPi formation and release as detected with PBP-MDCC. The DNA duplex was 24-/36-mer DNA duplex (X is G or 8-oxoG). Fluorescence changes were observed upon mixing of a pre-formed mixture of 2.0 μM Y50W, 2.1 μM DNA, and 1.0 mM DTT with 1.0 μM PBP-MDCC plus 100 μM dCTP at room temperature. Both syringes contained 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM NaCl, 0.005 Unit μL−1 PPase, and a phosphate “mop” (0.2 mM N7-methylguanosine and 0.2 U PNPase mL−1). Data were fit to a single-exponential model in OLIS Global Works to estimate the rates. (A) Y50W and DNA (x is 8-oxoG) mixed with 100 μM dCTP and PBP-MDCC, rate 4.7 ± 0.4 s−1. (B) Y50W and DNA8-oxoG mixed with 100 μM dCTP, rate 4.0 ± 0.3 s−1. (C) Y50W and DNA8-oxoG mixed with 100 μM dATP, rate 3.7 ± 0.6 s−1. Residuals are shown in the insets.

Kinetic simulation of multiple data sets

To estimate rate constants that are difficult to determine experimentally, e.g. k−2, k3, k−3, k5 and k−5, kinetic data defining nucleotide incorporation and conformational changes of Y50W were fit globally to a simplified model (Scheme 2). Due to the lack of data available to constrain the PPi release rate and post-catalytic conformational change rates, the steps after nucleotidyl transfer (steps 5 and 6 in Scheme 1) were simplified to one step (step 5 in Scheme 2). Data from the Y50W-catalyzed dCTP incorporation opposite G from steady-state kinetics (Fig. 9A), pre-steady state burst experiments (Fig. 9B), pre-steady state kinetics under single-turnover conditions (Fig. 9C), and a stopped-flow fluorescence trace (Fig. 9D) were fit to the kinetic model in Scheme 2. Measured kinetic constants, literature values, and simulated values are summarized in Table 5. The rate constant for nucleotide binding (k2) was assumed to be diffusion-limited (k2, 1×108 M−1 s−1) [46], and a simulated value of k−2 = 300 (± 47) s−1 was obtained, which gives the thermodynamic dNTP dissociation constant Kd,dCTP = 3 μM. This value is comparable to but not equal to the Kd,dCTP,app value of 1.0 μM found in the single-turnover polymerase assays, because Kd,dNTP,app equals the thermodynamic dNTP dissociation constant only when rapid-equilibrium dNTP binding (step 3 in Schemes 1 and 2) is followed directly by a rate-limiting and virtually irreversible step [24], which is obviously not the case for hpol κ. The rate constant k4 was calculated using a previously suggested approach, k4 = k3kpol/(k3−kpol) = 1.5 s−1 [23], and k−4 was set at 1 s−1 [27]. The simulated rate constants for the forward and reverse conformational changes upon nucleotide binding were 17 (± 4) s−1 and 6.5 (± 2) s−1, respectively. The simplified k5 is a function of both PPi release (step 5 in Scheme 1) and post-catalytic conformational change (step 6 in Scheme 1). A simulated value of 0.11 (± 0.01) s−1 is indicative that a slow and rate-limiting conformational change step occurs after chemistry. Standard deviations in Table 5 from global fitting reflect standard errors based on established algorithms for nonlinear regression from Kinetic Explorer®; however, these values can sometimes underestimate the results if they are not well-constrained when a model is overly complex [47]. We used FitSpace® to evaluate whether simulated results were unique and well constrained (Tables 5 and 6, Fig. 9E). Results show that k2 and k5 are well constrained, whereas k3, k−3, and k−5 are not well constrained. However, lower bounds for k3 and k−3 are 5.6 and 1.1 s−1, respectively, indicating the forward conformational change prior to nucleotidfyl transfer, although not uniquely defined with regard to rate, can not be rate-limiting. Since the rate of PPi release is at least 25 s−1, it is reasonable to place the PPi release step before the slow conformational relaxation, a common feature for hpol κ and Dpo4 [27]. Together, we conclude that the conformational change following nucleotidyl transfer is rate-limiting.

Table 5.

Summary of kinetic constants shown in Scheme 2. k1 and k−1 were derived from fluorescence anisotropy and stopped-flow measurements (data shown in Fig. 3). k2 was assumed to be diffusion-limited, and was set at 1×108 M−1 s−1. k4 was from k4 = k3kpol/(k3−kpol) = 1.5 s−1 as previously suggested [23], and k−4 was fixed at 1 s−1 [27]. Other values were from KinTek Global Kinetic Explorer simulation (Chi2/DoF = 1.64). Values with asterisk were not well constrained evaluated by FitSpace (Chi2 threshold at boundary 1.2), the lower bound for k3, k−3, and k−5 was 5.6 s−1, 1.1 s−1, and 1.8 × 10−7 M−1 s−1, respectively. Complete FitSpace results shown in Table S1 and Fig. S3.

|

k1 M1 s−1 |

k−1 s−1 |

k2 M−1 s−1 |

k−2 s−1 |

k3 s−1 |

k−3 s−1 |

k4 s−1 |

k−4 s−1 |

k5 s−1 |

k−5 M−1 s−1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | 4.8×108 | 48 | 1×108 | 1.5 | 1 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Simulated | 300 | 17* | 6.5* | 0.11 | 49* | |||||

| ±47 | ±4 | ±2 | ±0.01 | ±47 | ||||||

Table 6.

FitSpace® evaluation computed parameter boundaries. Chi2 threshold at boundary 1.2.

| Parameter | Lower bound | Upper bound |

|---|---|---|

| k−2 (s−1) | 120 | 910 |

| k3 (s−1) | 5.6 | 540 |

| k−3 (s−1) | 1.1 | 260 |

| k5 (s−1) | 0.087 | 0.17 |

| k−5 (M−1 s−1) | 1.8 × 10−7 | 360 |

Discussion

Detailed investigation of non-covalent steps in the catalytic cycle of Y-family DNA pols has proven to be challenging. In order to analyze the detailed dynamics of the important TLS DNA polymerase hpol κ, we used Trp as an internal probe of conformational changes. The two Trp residues in the catalytic core could be removed without affecting catalytic properties (Table 2), and new single Trp residues (positions 50 or 408, Fig. 1) were added while maintaining the characteristic coding properties for hpol κ for both G and 8-oxoG. Kinetic studies with the two Trp mutants of hpol κ allowed for separation of the conformational steps, i.e. following dNTP binding and phosphodiester bond formation (Scheme 2, Table 5).

The evidence indicates that the hpol κ mutants Y50W and T408W reflect the G and 8-oxoG bypass events of the WT enzyme. The patterns of steady-state catalytic efficiency were G:dCTP > 8-oxoG:dATP > 8-oxoG:dCTP for all three mutants (Table 2). In the pre-steady-state burst analysis, a similar order was observed for the burst amplitudes, except for T408W (Fig. 3, Table 3). Further pre-steady-state investigations were done with (only) the Y50W mutant, and the order of kpol/Kd,dNTP,app was 8-oxoG:dATP ≥ G:dCTP > 8-oxoG:dCTP (Table 4), as reported earlier for WT hpol κ [19].

Fig. 3.

Pre-steady-state burst kinetics of hpol κ and mutants under enzyme-limiting conditions. Each reaction was performed by rapid mixing of a pre-formed 100 nM 24-/36-mer DNA duplex (X: G or 8-oxoG)-hpol κ mixture with 1.0 mM dNTP in the presence of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 3 mM DTT, 50 μg BSA mL−1, and 5% (v/v) glycerol at 23 °C. Reactions were quenched with 0.5 M EDTA. (A) WT hpol κ (25 nM); (B) W214Y/W392H (25 nM); (C) Y50W (15 nM); (D) T408W (14 nM). The different base pairs are: G:dCTP (●), 8-oxoG:dATP (■), and 8-oxoG:dCTP (◆). Results were fit to the burst equation (Eq. 1).

Fluorescence tags provide a sensitive means of monitoring transient conformational changes in proteins. In the case of hpol κ, we were particularly interested in the N-clasp region, a section peculiar to pol κ and contributes to DNA binding [48], and placed a Trp residue there (Y50W). The fluorescence changes observed with Y50W were also seen with T408W (located at the linker between the thumb and little finger domains), and we interpret these to mean that the conformational changes we ascribe to hpol κ are rather global in nature and not restricted to the N-clasp region [31]. We utilized both mutants, which maintained catalytic properties of WT pol κ, to analyze the conformational dynamics of this Y-family DNA polymerase. The fluorescence changes observed in these experiments were highly reproducible, though the magnitude of fluorescence changes was less than half of that observed for Dpo4 [27], presumably due to differences in intrinsic properties of the two enzymes and possibly the positions of the Trp introduced. When phophodiester bond formation could occur during catalysis (G:dCTP), a biphasic fluorescence profile was observed upon mixing the pre-formed Y50W…DNA complex with dCTP, i.e. a fast decrease followed by a slower increase (Fig. 5). The fast decrease was observed regardless of whether nucleotidyl transfer could occur or not, i.e. with or without a dideoxy-terminated primer (Figs. 6 and 7), whereas similar changes were not seen for mispairs (Fig. 6). We thus attribute the initial fluorescence decrease to a correct dNTP-binding induced conformational change (step 3 in Scheme 2). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time a pre-catalytic conformational change has been directly observed for a Y-family mammalian DNA polymerase. Although a large finger domain motion upon dNTP binding has been shown for several DNA polymerases [49, 50] to provide evidence for the induced-fit hypothesis, similar changes for Y-family DNA polymerase have not been observed in crystallographic structures [19, 43, 51]. Such changes for Y-family DNA polymerases are considered to be subtle, but protium-deuterium exchange and fluorescence kinetics studies have clearly established that these occur [21, 27, 31, 46].

Upon nucleotidyl transfer, the fluorescence signal returned slowly to the ground state level (Fig. 7), whereas this gradual increase was not observed in the absence of phosphodiester bond formation (Fig. 6). The rate of the slow phase (0.014 (± 0.002) s−1) was comparable to kcat (0.025 (± 0.002) s−1) and was not dependent on dNTP concentration. This phase is considered to be associated with catalysis (steps 4 and 5 in Scheme 2), in that (i) it was only seen when phosphodiester bond formation could occur, (ii) it was fast enough to be associated with catalysis in the first reaction cycle (~ kcat), and (iii) because it was much smaller than kpol, 1.4 (± 0.1) s−1, (Table 4), it must occur after nucleotidyl transfer.

Many catalytic schemes for DNA polymerase show PPi release as the last step, following the relaxation of the conformational changes. Vaisman et al. speculated that PPi release might be a slow step with S. solfataricus Dpo4 [51]. However, our own measurements with a PBP system indicated that PPi release from Dpo4 is very fast, and accordingly we placed the step prior to the conformational relaxation step [27]. We used a similar approach in this work and concluded that PPi formation and release (which is required for binding to the PBP protein and its change in fluorescence) is too fast to be rate-limiting and is after the nucleotidyl transfer step.

We developed a simplified minimal kinetic model (Scheme 2) using KinTek Explorer® and FitSpace® to globally fit multiple data sets (Fig. 9) [47, 52]. Several points can be made about this model. The DNA binding event is considered fast, which was seen with the value of k1 4.8 × 108 M−1 s−1 derived from fluorescence anisotropy and stopped-flow measurements (Fig. 4). The binding of dNTP was assumed to be diffusion-limited and was set at 1.0×108 M−1 s−1 [27, 46]. The lower bound of rate of conformational change before the phosphodiester bond formation suggests that it is too fast to be rate-limting. The slow fluorescence step (Fig. 7) following the nucleotidyl transfer step is rate-limiting with the template G:dCTP pair, controlling kcat, and is part of step 5 in our simplified minimal kinetic model (Scheme 2). Due to lack of data to constrain the PPi release rate, we present a simplified step 5, which could be composed of at least PPi release and the slow conformational change steps. However, because of a much slower conformational relaxation (that can still be accommodated by kcat) and the lower limit of PPi release step, we place the slower conformation change after the PPi release step for hpol κ, similar to Dpo4 [27]. Although the kinetic model may not be unique in explaining all of the results, it does accommodate all of our experimental observations and provides a framework for further hypothesis generation and testing.

The approach we applied here and the conclusions derived from the results permit a considerable degree of understanding of the conformational dynamics of hpol κ with normal pairing and with the adduct 8-oxoG. This information is augmented by the availability of multiple X-ray crystal structures (WT hpol κ with G:C and 8-oxoG pairing) [19, 43]. We propose that similar structural and kinetic approaches might be applied to other human TLS DNA polymerases, e.g. pol η and pol ι, in order to better understand their mechanisms, in that TLS DNA polymerases have been shown to vary considerably in terms of their catalytic specificities [15].

Material and methods

Materials

All reagents were of the highest quality commercially available. Unlabeled dNTPs and T4 polynucleotide kinase were from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). [γ-32P]ATP (specific activity 3×103 Ci mmol−1) was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). Oligonucleotides were synthesized and HPLC-purified by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Primer and template sequences used are summarized in Table 1.

Expression and Purification of hpol κ

Recombinant wild-type hpol κ (residues 19–526) was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) Rosetta 2 cells (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA) as an N-terminally tagged MBP:hpol κ fusion protein. The W214Y/W392H, L21W, L31W, Y50W, and T408W hpol κ mutants were expressed from BL21 Gold (DE3) cells (Stratagene) as N-terminal (His)6-tagged GST:hpol κ fusion proteins from the vector pBG101. Both MBP and GST affinity tags were excised with PreScission Protease at a cleavage site (LEVLFQ/G) between the tag and the hpol κ sequence. The PreScission Protease recognition sequences and hpol κ coding sequences were verified by nucleotide sequence analysis in the Vanderbilt facility. Cells were grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.5. After induction with 1.0 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, the cells were allowed to grow for 15 h at 18 °C. Cell extracts were prepared by sonication. The MBP:hpol κ fusion protein was bound to a 3-mL Amylose column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and the GST:hpol κ fusion protein was bound to a 5-ml NTA-Ni2+ column (GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT. The MBP:hpol κ fusion protein was cleaved directly on the column by the addition of PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare, 2 units mL−1) and incubation at 4 °C for 12–48 h. The eluted fraction containing hpol κ was collected and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal concentrator (Millipore, Billerica, MA). For the GST:hpol κ fusion proteins, a step-wise imidazole gradient was used to elute the full-length fusion proteins from the NTA-Ni2+ column, and PreScission Protease was added to the solution which was then incubated at 4 °C for 12–48 h. The cleaved GST:hpol κ protein was loaded onto a 1-mL GSTrap HP column (GE Healthcare), and the flow-through fraction containing purified hpol κ was collected and concentrated. Glycerol was added to 50% (v/v) to the purified hpol κ, which was stored at −80 °C. A280 measurements (ε280: 27,390 M−1 cm−1 (WT); ε280: 17,880 M−1 cm−1 (W214Y/W392H); ε280: 21,890 M−1 cm−1 (Y50W); ε280: 23,380 M−1 cm−1 (T408W)) were used for the estimation of protein concentrations using the Expasy ProtParam Tool (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/).

Steady-state kinetics

All the kinetic and fluorescence assays were measured at 23 °C. The steady-state kinetic assays were performed following published procedures [53, 54]. Specifically, the 24-mer primer was 5[γ-32P]ATP end-labeled and annealed to a 36-mer template containing G or 8-oxoG at the insertion site. Reactions were started by adding various concentrations of a dNTP to a mixture of 133 nM DNA duplex, 1 to 9 nM polymerase (for different reactions), 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 5 mM DTT, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 μg BSA mL−1, and 5% glycerol (v/v), with 1- to 10-min incubation times. A 1.5-μL reaction aliquot was added to 9 µl of 20 mM EDTA (pH 9.0) in 95% formamide (v/v) to quench the reaction. Products were separated using 18% acrylamide (w/v)/7.5 M urea gels, and results were visualized using a phosphorimaging system (Bio-Rad, Molecular Imager® FX) and analyzed by Quantity One software. Data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation to obtain kcat and Km by non-linear regression using the program Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Rapid Quench Analysis

A KinTek RQF-3 model chemical quench-flow apparatus (KinTek Corp., Austin, TX) was used to perform the pre-steady-state kinetics. Burst kinetic experiments were carried out under enzyme-limiting conditions with rapid mixing of 100 nM 24-/36-mer deplux containing G or 8-oxoG at the insertion site and 50 nM polymerase with 1 mM dNTP in the presence of 3 mM DTT, 50 μg BSA mL−1, and 5% glycerol (v/v). Both syringes contained 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and 5 mM MgCl2. Individual reactions proceeded for set times (5 ms to 8 s) and were quenched with the addition of 0.5 M EDTA. Reaction products were analyzed as described above, and data were fit to a burst equation (Eq. 1, vide infra). The extrapolated maximal rate constant for single nucleotide incorporation (kpol) and the apparent constant of nucleotide dissociation from kinetically active ternary complex (Kd,dNTP,app) were measured in the presence of excess enzyme (e.g., 0.75 μM polymerase and 25 nM DNA duplex, final concentrations after mixing) using a series of concentrations of dNTP. Time-dependent product formation at each dNTP concentration was fit to Eq. 2 (data analysis section) to obtain the kobs, which was then plotted as a function of dNTP concentration and fit to a hyperbolic equation (Eq. 3, data analysis section).

Steady-state Spectroscopy

UV spectra were recorded using a Cary 14-OLIS spectrophotometer (On-Line Instrument Systems, Bogart, GA). Fluorescence measurements were made with an OLIS DM-45 instrument.

Stopped-flow Fluorescence Measurements

Y50W conformational changes following dNTP binding

An OLIS RSM-1000 spectrofluorimeter was used in all stopped-flow fluorescence measurements [27]. For measurement of Y50W conformational changes, optimal signal/noise ratios were obtained using 1.24-mm slits (nominal 8 nm bandwidth) along with a >324 nm long-pass filter (Newport, Irvine, CA) attached to the sample photomultiplier tube. Fluorescence was measured upon mixing 2.1 μM DNA duplex, 2.0 μM polymerase, 5 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT in one syringe with dNTP in another. Both syringes contained 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and 5 mM MgCl2. Fluorescence changes when phosphodiester bond formation could occur were obtained by using DNAG as the substrate for Y50W and T408W; DNA duplex (13-mer-Cdd/18-mer) with a dideoxy-terminated primer was used for experiments in the absence of phosphodiester bond formation. Fluorescence traces were fit to a double-exponential model using OLIS Global Works software.

Kinetics of DNA-hpol κ binding

The dissociation rate of a DNA duplex from hpol κ was measured using stopped-flow techniques. Specifically, one of the two syringes contained a pre-formed complex of WT hpol κ (2 μM) and a FAM-labeled 24-/36-mer duplex (0.4 μM) in the presence of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8 at 25 °C) containing 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT. The second syringe contained an unmodified 24-/36-mer duplex (2 μM) to trap the enzyme that dissociated from the polymerase-oligonucleotide complex. The excitation wavelength was at set at 485 nm with a 515 nm emission cutoff (long-pass) filter (Newport, Irvine, CA) and a 1-mm slit width. The resulting fluorescence change was fitted to a single exponential equation (Eq. 2).

Kinetics of PPi release

To measure the fluorescence changes of MDCC-PBP upon PPi binding, 1.24-mm slits and a >455 nm long-pass filter (Oriel, Stratford, CT) were used in the stopped-flow experiments as described previously [44, 45]. E. coli PBP (A197C mutation) was a generous gift from K. D. Raney (Univ. Arkansas Medical School, Little Rock, AR) and was labeled with MDCC and purified following a previously described protocol [27, 55, 56]. In a typical experiment, one syringe contained 1.0 μM PBP-MDCC and 100 μM dCTP. The other syringe contained 2.0 μM hpol κ mutant (Y50W), 2.1 μM DNA duplex, and 1 mM DTT. Both syringes contained a Pi “mop” (0.2 mM N7-methylguanosine, 0.2 U ml−1 PNPase), 0.005 U μL−1 PPase, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2.

Determination of Kd,DNA using fluorescence anisotropy

Experimental conditions and data analysis were similar to previous work [57]. Specifically, a FAM-labeled 24-/36-mer duplex (2 nM) was incubated with varying concentrations of hpol κ or Y50W (0 to 1 μM), and fluorescence polarization was measured in a Biotek SynergyH4 plate reader using filter sets, λex 485 ± 20 nm and λem 525 ± 20 nm. All titrations were performed in 50 mM potassium HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ZnCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1 mg mL−1 BSA. Results were analyzed using Eq. 4 and Eq. 5 as explained below.

Conventional data analysis

Burst kinetics results were fit to equation 1,

| (Eq. 1) |

where A is the amplitude of product formation following the first binding event, kobs is the rate of polymerization, kss is steady-state rate of nucleotide incorporation, and t is time. To estimate kpol and Kd, dNTP,app under enzyme excess conditions, data were fit to equation 2,

| (Eq. 2) |

where A is the amplitude of product formation associated with the first binding event, kobs is the rate of polymerization, and t is time. Kinetic parameters obtained using Equation 2 were fit to a hyperbolic function to describe the concentration dependence in equation 3,

| (Eq. 3) |

In fluorescence anisotropy experiments, polarization was determined using equation 5:

| (Eq. 4) |

where Fp is the fluorescence intensity parallel to the excitation, and Fv is the fluorescence intensity perpendicular to the excitation plane. The resulting changes in polarization were plotted against protein concentration and fit to a quadratic equation 6:

| (Eq. 5) |

where P is the measured change in fluorescence polarization, Etotal is the concentration of enzyme, DNAtotal is the concentration of FAM-labeled 24-/36-mer, and Kd is the measured equilibrium dissociation constant for DNA-enzyme binding. The binding curves were fit such that DNAtotal was fixed to be constant between curves.

Global data fitting

Steady-state, pre-steady state burst, pre-steady state nucleotide concentration-dependent, and stopped-flow fluorescence data were fit to a minimal kinetic model using the program KinTek Explorer® (v.4.0) and FitSpace® [47, 52]. Rate constants derived experiments were: k−1, 48 s−1; k1, 4.8×108 M−1 s−1 (from k−1/Kd,DNA); k4, 1.5 s−1. Estimated values for k2 were set at 1 ×108 M−1 s−1 (diffusion-limited collision) and at 1 s−1 for k−4 [27, 45]. The rest of the rate constants (k−2, k3, k−3, k5, and k−5) were allowed to fluctuate, and their values were estimated by global fitting to four different data sets.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. D. Raney for providing PBP. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 ES010375 (to FPG), T32 ES007028 (to FPG, MGP), R00 GM084460 (to RLE), and Central Michigan University start-up funds (to LZ).

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DTT

dithiotheitol

- FAM

fluorescein amidite

- GST

glutathione transferase

- hpol κ

human DNA polymerase κ (catalytic core containing residues 19–526)

- MBP

maltose binding protein

- MDCC

N-2-(1-maleimidyl)ethyl]-7-(diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxamide

- 8-oxoG

7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine

- PBP

phosphate-binding protein

- PNPase

purine nucleoside phosphorylase

- pol

DNA polymerase

- Pi

phosphate

- PPase

(yeast) pyrophosphatase

- PPi

pyrophosphate

- TLS

translesion synthesis

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Author contributions: FPG and RLE conceived the idea and provided resources. MGP optimized and purified the mutant enzymes, and performed some of the fluorescence measurements. RLE measured the Kd,DNA and koff,DNA. LZ conducted most of the kinetic experiments and analyzed data. LZ and FPG wrote the manuscript. SY and CAF assisted with pre-steady-state analysis and enzyme purification, respectively. All authors commented on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Swenberg JA, Lu K, Moeller BC, Gao L, Upton PB, Nakamura J, Starr TB. Endogenous versus exogenous DNA adducts: their role in carcinogenesis, epidemiology, and risk assessment. Toxicol Sci. 2011;120(Suppl 1):S130–45. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hübscher U, Maga G. DNA replication and repair bypass machines. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leman A, Noguchi E. The replication fork: understanding the eukaryotic replication machinery and the challenges to genome duplication. Genes. 2013;4:1–32. doi: 10.3390/genes4010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sale JE, Lehmann AR, Woodgate R. Y-family DNA polymerases and their role in tolerance of cellular DNA damage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:141–152. doi: 10.1038/nrm3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang M, Bruck I, Eritja R, Turner J, Frank EG, Woodgate R, O’Donnell M, Goodman MF. Biochemical basis of SOS-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli: recontitution of in vitro lesion bypass dependent on the UmuD’2C mutagenic complex and RecA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9755–9760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witkin EM. Mutation-proof and mutation-prone modes of survival in derivatives of Escherichia coli B differing in sensitivity to ultraviolet light. Brookhaven Sympos Biol. 1967;20:495–503. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKenzie GJ, Harris RS, Lee PL, Rosenberg SM. The SOS response regulates adaptive mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6646–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120161797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedberg EC, Wagner R, Radman M. Specialized DNA polymerases, cellular survival, and the genesis of mutations. Science. 2002;296:1627–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1070236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodgate R. A plethora of lesion-replicating DNA polymerases. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2191–2195. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bridges BA. Error-prone DNA repair and translesion DNA synthesis. II: The inducible SOS hypothesis. DNA Repair. 2005;4:725–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.12.009. 739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Yamada A, Dohmae N, Yokoi M, Yuasa M, Araki M, Iwai S, Takio K, Hanaoka F. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase eta. Nature. 1999;399:700–704. doi: 10.1038/21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L. The human DINB1 gene encodes the DNA polymerase pol theta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3838–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hübscher U, Maga G. DNA replication and repair bypass machines. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:627–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh JM, Ippoliti PJ, Ronayne EA, Rozners E, Beuning PJ. Discrimination against major groove adducts by Y-family polymerases of the DinB subfamily. DNA Repair. 2013;12:713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi J-Y, Angel KC, Guengerich FP. Translesion synthesis across bulky N2-alkylguanine DNA adducts by human DNA polymerase κ. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21062–21072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamiya H, Kurokawa M. Mutagenic bypass of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-hydroxyguanine) by DNA polymerase κ in human cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:1771–1776. doi: 10.1021/tx300259x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haracska L, Prakash L, Prakash S. Role of human DNA polymerase κ as an extender in translesion synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16000–16005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252524999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irimia A, Eoff RL, Guengerich FP, Egli M. Structural and functional elucidation of the mechanism promoting error-prone synthesis of human DNA polymerase κ opposite the 7,8-dihydro-8-oxodeoxyguanosine adduct. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22467–22480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zang H, Irminia A, Choi J-Y, Angel KC, Loukachevitch LV, Egli M, Guengerich FP. Efficient and high fidelity incorporation of dCTP opposite 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-deoxyguanosine by Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA polymerase Dpo4. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2358–2372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eoff RL, Irimia A, Angel K, Egli M, Guengerich FP. Hydogen bonding of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxodeoxyguanosine with a charged residue in the little finger domain determines miscoding events in Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA polymerase Dpo4. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19831–19843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SS, Wong I, Johnson KA. Pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of processive DNA replication including complete characterization of an exonuclease-deficient mutant. Biochemistry. 1991;30:511–525. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai YC, Johnson KA. A new paradigm for DNA polymerase specificity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9675–87. doi: 10.1021/bi060993z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roettger MP, Bakhtina M, Kumar S, Tsai M-D. 8.10 – Catalytic mechanism of DNA polymerases. In: Liu H-W, Mander L, editors. Comprehensive Natural Products II. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2010. pp. 349–383. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahlberg ME, Benkovic SJ. Kinetic mechanism of DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment): identification of a second conformational change and evaluation of the internal equilibrium constant. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4835–43. doi: 10.1021/bi00234a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong I, Patel SS, Johnson KA. An induced-fit kinetic mechanism for DNA replication fidelity: direct measurement by single-turnover kinetics. Biochemistry. 1991;30:526–537. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beckman JW, Wang Q, Guengerich FP. Kinetic analysis of nucleotide insertion by a Y-Family DNA polymerase reveals conformational change both prior to and following phosphodiester bond formation as detected by tryptophan fluorescence. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36711–36723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806785200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maxwell BA, Suo Z. Recent insight into the kinetic mechanisms and conformational dynamics of Y-Family DNA polymerases. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2804–2814. doi: 10.1021/bi5000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiala KA, Suo Z. Mechanism of DNA polymerization catalyzed by Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 DNA polymerase IV. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2116–2125. doi: 10.1021/bi035746z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kellinger MW, Johnson KA. Nucleotide-dependent conformational change governs specificity and analog discrimination by HIV reverse transcriptase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7734–7739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913946107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu C, Maxwell BA, Brown JA, Zhang L, Suo Z. Global conformational dynamics of a Y-Family DNA polymerase during catalysis. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunlap CA, Tsai M-D. Use of 2-aminopurine and tryptophan fluorescence as probes in kinetic analyses of DNA polymerase β. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11226–11235. doi: 10.1021/bi025837g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subuddhi U, Hogg M, Reha-Krantz LJ. Use of 2-aminopurine fluorescence to study the role of the beta hairpin in the proofreading pathway catalyzed by the phage T4 and RB69 DNA polymerases. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6130–6137. doi: 10.1021/bi800211f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stivers JT. 2-aminopurine fluorescence studies of base stacking interactions at abasic sites in DNA: metal-ion and base sequence effects. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3837–3844. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.16.3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frey MW, Sowers LC, Millar DP, Benkovic SJ. The nucleotide analog 2-aminopurine as a spectroscopic probe of nucleotide incorporation by the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli polymerase I and bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9185–9192. doi: 10.1021/bi00028a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fidalgo da Silva E, Mandal SS, Reha-Krantz LJ. Using 2-aminopurine fluorescence to measure incorporation of incorrect nucleotides by wild type and mutant bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40640–40649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaloszynski P, Ohashi E, Ohmori H, Nishimura S. Error-prone and inefficient replication across 8-hydroxyguanine (8-oxoguanine) in human and mouse ras gene fragments by DNA polymerase κ. Genes Cells. 2005;10:543–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Silverstein TD, Lone S, Swan MK, Choudhury JR, Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L, Aggarwal AK. Structure of human DNA polymerase kappa inserting dATP opposite an 8-oxoG DNA lesion. PloS one. 2009;4:e5766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joyce CM. Techniques used to study the DNA polymerase reaction pathway. BBA – Proteins Proteom. 2010;1804:1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pence MG, Blans P, Zink CN, Fishbein JC, Perrino FW. Bypass of N2-ethylguanine by human DNA polymerase κ. DNA Repair. 2011;10:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furge LL, Guengerich FP. Explanation of pre-steady-state kinetics and decreased burst amplitude of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase at sites of modified DNA bases with an additional non-productive enzyme-DNA-nucleotide complex. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4818–4825. doi: 10.1021/bi982163u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furge LL, Guengerich FP. Analysis of nucleotide insertion and extension at 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine by replicative T7 polymerase exo− and human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase using steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6475–6487. doi: 10.1021/bi9627267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lone S, Townson SA, Uljon SN, Johnson RE, Brahma A, Nair DT, Prakash S, Prakash L, Aggarwal AK. Human DNA polymerase kapa encircles DNA: implications for mismatch extension and lesion bypass. Mol Cell. 2007;25:601–614. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanes JW, Johnson KA. Real-time measurement of pyrophosphate release kinetics. Anal Biochem. 2008;372:125–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanes JW, Johnson KA. A novel mechanism of selectivity against AZT by the human mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6973–83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kellinger MW, Johnson KA. Role of induced fit in limiting discrimination against AZT by HIV reverse transcriptase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5008–5015. doi: 10.1021/bi200204m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson KA, Simpson ZB, Blom T. FitSpace Explorer: An algorithm to evaluate multidimensional parameter space in fitting kinetic data. Anal Biochem. 2009;387:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uljon SN, Johnson RE, Edwards TA, Prakash S, Prakash L, Aggarwal AK. Crystal structure of the catalytic core of human DNA polymerase κ. Structure. 2004;12:1395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu EY, Beese LS. The structure of a high fidelity DNA polymerase bound to a mismatched nucleotide reveals an “ajar” intermediate conformation in the nucleotide selection mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19758–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doublié S, Sawaya MR, Ellenberger T. An open and closed case for all polymerases. Structure. 1999;7:R31–R35. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaisman A, Ling H, Woodgate R, Yang W. Fidelity of Dpo4: effect of metal ions, nucleotide selection and pyrophosphorolysis. EMBO J. 2005;24:2957–2967. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson KA, Simpson ZB, Blom T. Global Kinetic Explorer: A new computer program for dynamic simulation and fitting of kinetic data. Anal Biochem. 2009;387:20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boosalis MS, Petruska J, Goodman MF. DNA polymerase insertion fidelity: gel assay for site-specific kinetics. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:14689–14696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao L, Christov PP, Kozekov ID, Pence MG, Pallan PS, Rizzo CJ, Egli M, Guengerich FP. Replication of N2,3-ethenoguanine by DNA polymerases. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:5466–5469. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Webb MR. A fluorescent sensor to assay inorganic phosphate. In: Johnson KA, editor. Kinetic Analysis of Macromolecules A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2003. pp. 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brune M, Hunter JL, Howell SA, Martin SR, Hazlett TL, Corrie JE, Webb MR. Mechanism of inorganic phosphate interaction with phosphate binding protein from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10370–80. doi: 10.1021/bi9804277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ketkar A, Zafar MK, Maddukuri L, Yamanaka K, Banerjee S, Egli M, Choi J-Y, Lloyd RS, Eoff RL. Leukotriene biosynthesis inhibitor MK886 Iimpedes DNA polymerase activity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26:221–232. doi: 10.1021/tx300392m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]