ABSTRACT

Microbial conversion of carbon dioxide to organic commodities via syngas metabolism or microbial electrosynthesis is an attractive option for production of renewable biocommodities. The recent development of an initial genetic toolbox for the acetogen Clostridium ljungdahlii has suggested that C. ljungdahlii may be an effective chassis for such conversions. This possibility was evaluated by engineering a strain to produce butyrate, a valuable commodity that is not a natural product of C. ljungdahlii metabolism. Heterologous genes required for butyrate production from acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) were identified and introduced initially on plasmids and in subsequent strain designs integrated into the C. ljungdahlii chromosome. Iterative strain designs involved increasing translation of a key enzyme by modifying a ribosome binding site, inactivating the gene encoding the first step in the conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetate, disrupting the gene which encodes the primary bifunctional aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase for ethanol production, and interrupting the gene for a CoA transferase that potentially represented an alternative route for the production of acetate. These modifications yielded a strain in which ca. 50 or 70% of the carbon and electron flow was diverted to the production of butyrate with H2 or CO as the electron donor, respectively. These results demonstrate the possibility of producing high-value commodities from carbon dioxide with C. ljungdahlii as the catalyst.

IMPORTANCE

The development of a microbial chassis for efficient conversion of carbon dioxide directly to desired organic products would greatly advance the environmentally sustainable production of biofuels and other commodities. Clostridium ljungdahlii is an effective catalyst for microbial electrosynthesis, a technology in which electricity generated with renewable technologies, such as solar or wind, powers the conversion of carbon dioxide and water to organic products. Other electron donors for C. ljungdahlii include carbon monoxide, which can be derived from industrial waste gases or the conversion of recalcitrant biomass to syngas, as well as hydrogen, another syngas component. The finding that carbon and electron flow in C. ljungdahlii can be diverted from the production of acetate to butyrate synthesis is an important step toward the goal of renewable commodity production from carbon dioxide with this organism.

INTRODUCTION

Acetogenic microorganisms are attractive catalysts for the conversion of syngas or carbon monoxide to organic commodities (1–7) and also have the ability to convert carbon dioxide to organic products with electrons derived from an electrode in a process known as microbial electrosynthesis (5, 8, 9). An attractive feature favoring the use of acetogens in these processes is that the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, which is naturally present in acetogens, provides the most effective known pathway for converting carbon dioxide to organic compounds that are then excreted from the cell (5, 10).

Acetogens typically produce acetate as their primary end product, but other natural products include ethanol, 2,3-butanediol, butyrate, and butanol (1–3, 6, 7, 11–13). Furthermore, under the appropriate conditions, products other than acetate may predominate. For example, modifying growth conditions permitted Clostridium ljungdahlii and Clostridium autoethanogenum (C. D. Mihalcea, J. M. Y. Fung, B. Al-Sinawi, and L. P. Tran, U.S. patent application publication no. US/0230894 A1) to produce ethanol as the dominant product from syngas metabolism and allowed Butyribacterium methylotrophicum adapted for growth on carbon monoxide to produce butyrate at molar levels comparable with those of acetate (14).

Genetic engineering is another approach to enhance the production of commodities other than acetate (1). Transient production of butanol was achieved by expressing genes required for butanol production on a plasmid introduced into C. ljungdahlii (15). Expression of heterologous genes for acetone in C. ljungdahlii diverted carbon and electron flow to this product (16). Moorella thermoacetica was genetically manipulated to produce lactate (17). However, in none of these studies was production of the target commodity optimized with additional genetic modifications, such as deletion of genes for competing pathways. Much more impressive yields of multicarbon products from Clostridium strains were reported in studies by researchers at Syngas Biofuels Energy, Inc., but the validity of these results is doubtful (1).

An improved array of tools for genetic manipulation of C. ljungdahlii (16, 18) and a steadily improving understanding of its physiology (11, 15, 19–23) suggested that C. ljungdahlii might be an effective acetogen chassis for the construction of strains that produce organic products with more than two carbons from carbon dioxide with high yields.

We chose butyrate for proof-of-concept studies. Butyrate is a food supplement that benefits colon function (24, 25) and is also used in food flavorings (26, 27). Butyrate is a feedstock for production of cellulose acetate butyrate (28), which is a thermoplastic that has a wide range of applications, such as paints (29) and polymers, such as poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)/cellulose acetate butyrate (30). Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) was synthesized from butyrate using an engineered strain of Ralstonia eutropha (31). Furthermore, butyrate is a precursor to butanol, which has value as a fuel (32, 33).

Current industrial production of butyrate relies on chemical synthesis from petroleum. Another potential biological route is fermentation of sugars (34–38). Several strains naturally produce high titers of butyrate from sugars, and butyrate production has been enhanced with genetic engineering or adaptation approaches (37–45).

However, producing butyrate from carbon dioxide with waste gases (1) or renewable electricity (5) as the energy source may be more environmentally sustainable and does not consume high-quality biomass feedstocks that may be more appropriately consumed as food. Therefore, we evaluated the possibility of engineering C. ljungdahlii to produce butyrate from carbon dioxide.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Initial engineering of C. ljungdahlii for butyrate production: strain B1.

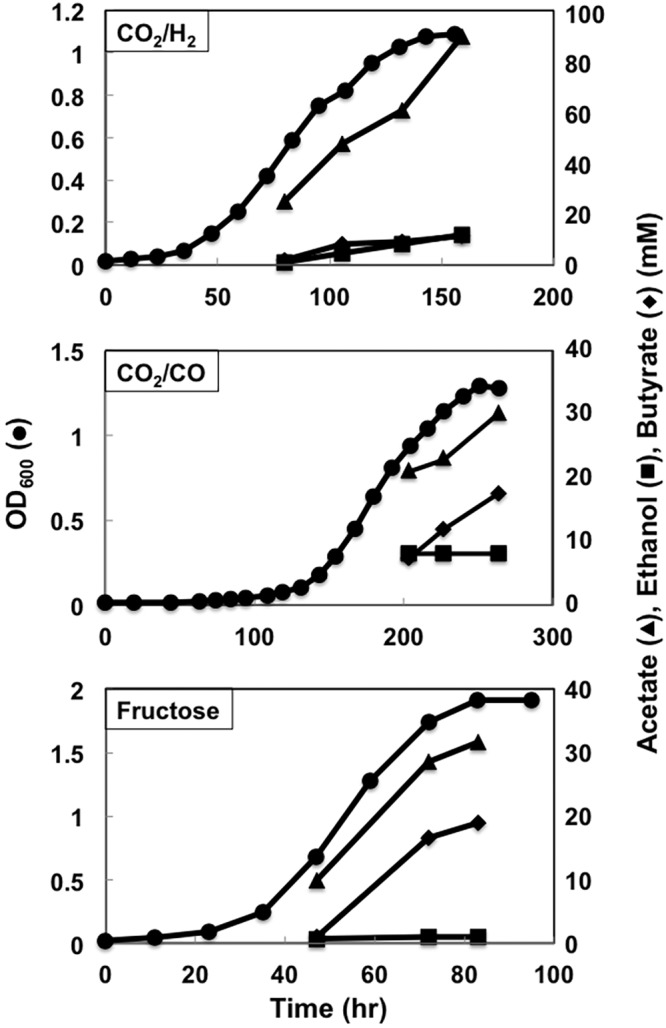

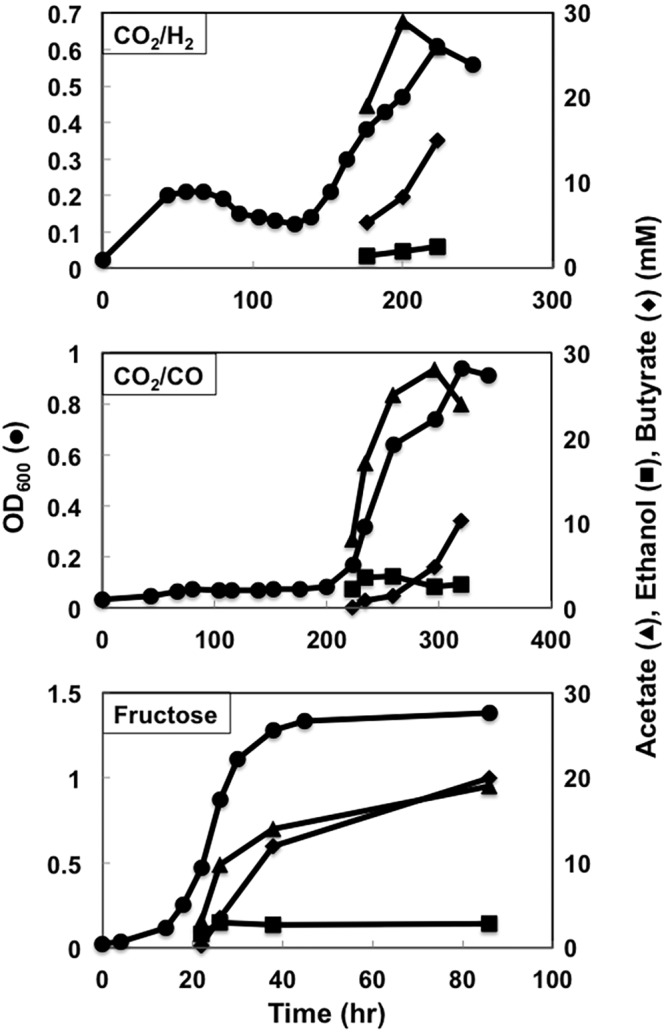

As previously reported (46, 47), wild-type cells grew with either H2, CO, or fructose as the electron donor, with acetate as the primary end product (Fig. 1 and 2). Growth rates and yields were highest with fructose, intermediate with CO, and lowest with H2.

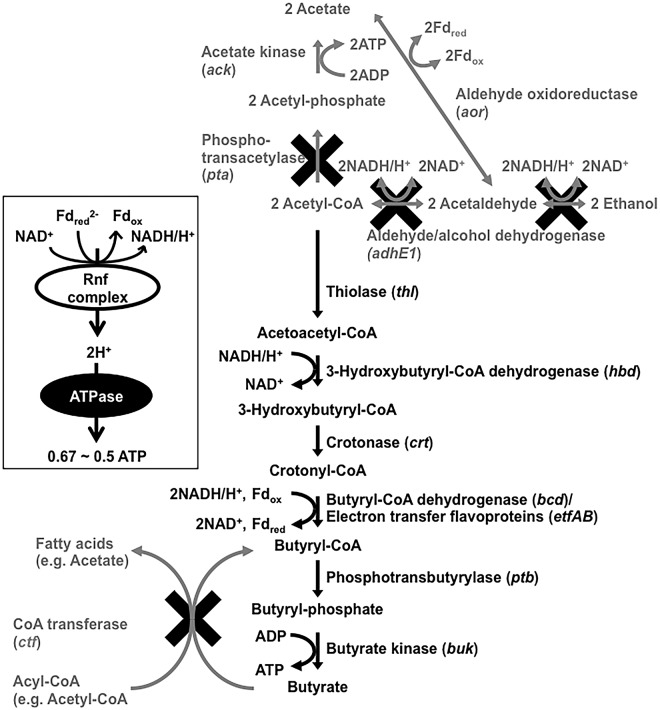

FIG 1 .

Engineering a pathway for butyrate synthesis. The C. ljungdahlii native pathways for acetate and ethanol formation are indicated in grey. The added butyrate pathway is in black. Genes encoding enzymes are in parentheses. The thick black “x” indicates pathways that were disrupted in this study.

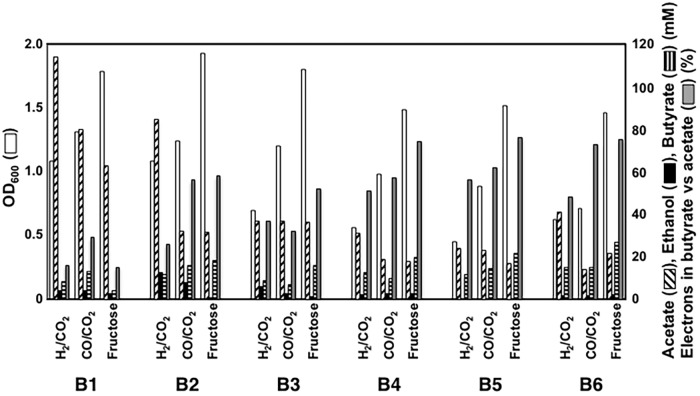

FIG 2 .

Growth profiles of the C. ljungdahlii wild-type strain. Data are representative of duplicate cultures.

In order to redirect carbon and electron flow to the production of butyrate, the following genes from Clostridium acetobutylicum were introduced into C. ljungdahlii: thl, which encodes thiolase for the synthesis of acetoacetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) from acetyl-CoA; hbd, which encodes 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase for the synthesis of 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA from acetoacetyl-CoA; crt, which encodes crotonase for the synthesis of crotonyl-CoA from 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA; bcd, which encodes butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase for the synthesis of butyryl-CoA from crotonyl-CoA; etfA and etfB, which encode electron transfer flavoproteins that form an enzyme complex with butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase for the synthesis of butyryl-CoA; ptb, which encodes phosphotransbutyrylase for the synthesis of butyryl phosphate from butyryl-CoA; and buk, which encodes butyrate kinase for synthesis of butyrate from butyryl phosphate (Fig. 1). The genes thl, crt, bcd, etfA, etfB, and hbd were on one plasmid, and the genes ptb and buk were on a second plasmid (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). The expression of all eight genes was under the control of the putative promoter of the pta gene from C. ljungdahlii, which is considered to be highly expressed under a diversity of conditions. This strain was designated B1.

Both acetate synthesis via the Pta/Ack pathway and butyrate synthesis via the Ptb/Buk pathway result in ATP production (Fig. 1). The conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetate is expected to yield 1 ATP via substrate-level phosphorylation, whereas only 0.5 ATP is expected to be derived from each acetyl-CoA converted to butyrate (Fig. 1). However, the conversion of crotonyl-CoA to butyryl-CoA catalyzed by the complex of Bcd and EtfAB is considered to be coupled with energy generation via the Rnf complex and ATP synthase (Fig. 1) to yield ca. 0.5 ATP (48, 49), but the stoichiometry of the proton gradient and ATP generation has not been clarified for C. ljungdahlii. Butyrate synthesis from acetyl-CoA requires additional reducing equivalents in the form of NADH for Hbd to reduce acetoacetyl-CoA to 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA (50) and for Bcd to reduce crotonyl-CoA to butyryl-CoA (51).

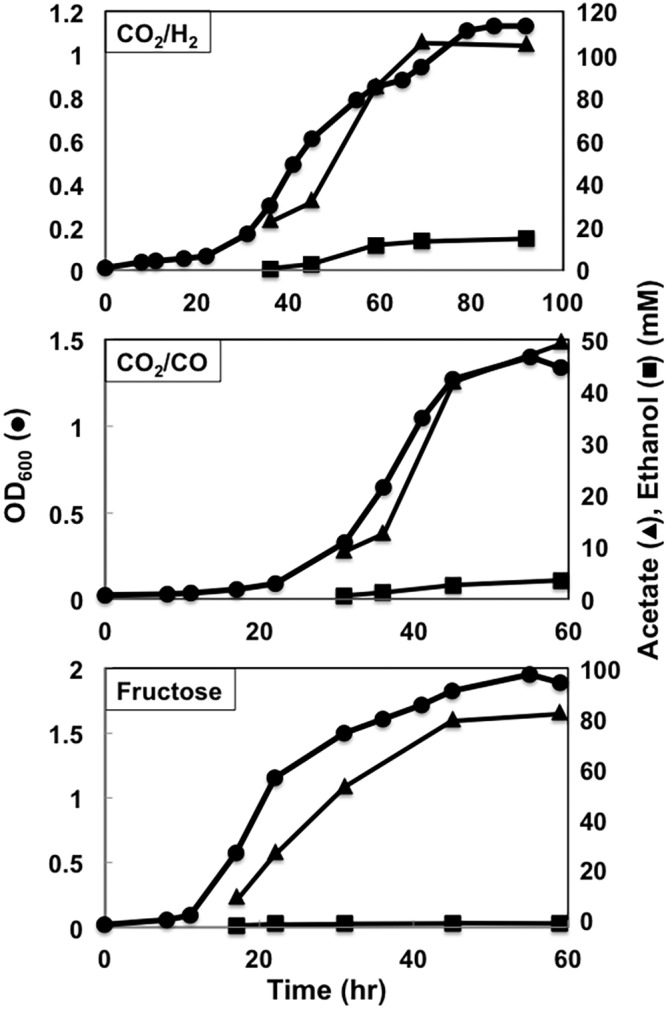

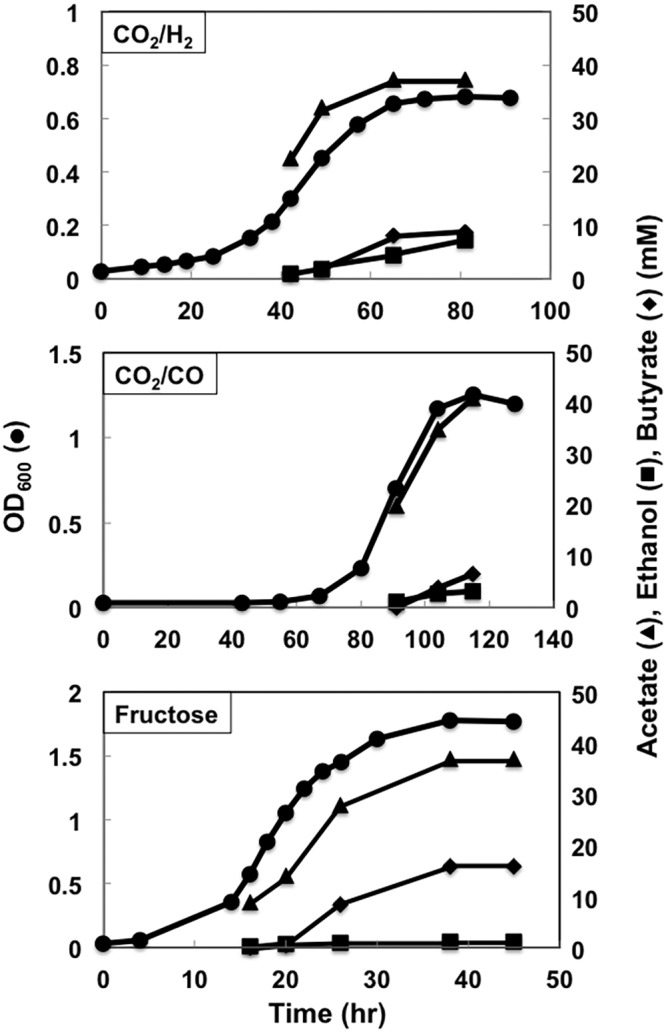

When grown with H2 as the electron donor, strain B1 produced butyrate as well as acetate and ethanol over time (Fig. 3 and 4). Acetate remained the primary product, with minor production of ethanol, but the butyrate produced (8.5 mM) accounted for 13% of the carbon and 16% of the electrons appearing in acetate. More butyrate was produced with CO as the electron donor than with H2 (Fig. 3 and 4), and the proportion of carbon and electrons in butyrate compared to that in acetate, 25% and 29%, respectively, was also greater. Butyrate production was lowest during growth on fructose, with only slightly more butyrate than ethanol produced (Fig. 3 and 4). When grown with H2 or CO as the electron donor, strain B1 had longer lag periods and lower growth rates than the wild-type strain, but the final cell yields were comparable to those of the wild-type strain with all three substrates.

FIG 3 .

Growth profiles of strain B1. Data are representative of duplicate cultures.

FIG 4 .

Summary of yields of biomass (OD600), acetate (mM), ethanol (mM), butyrate (mM), and electrons appearing in butyrate versus acetate (%). Data are means from duplicate cultures.

Enhancing Crt expression through ribosome binding site modification: strain B2.

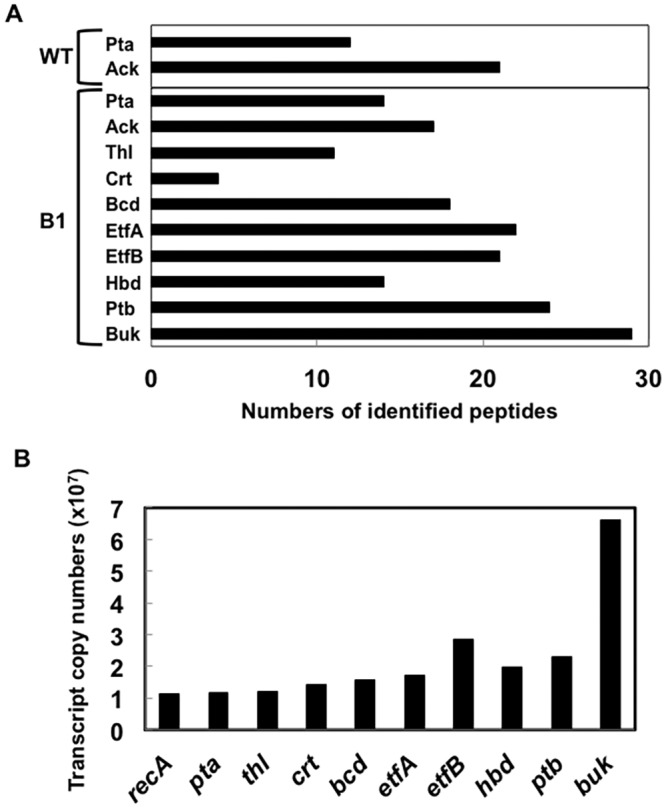

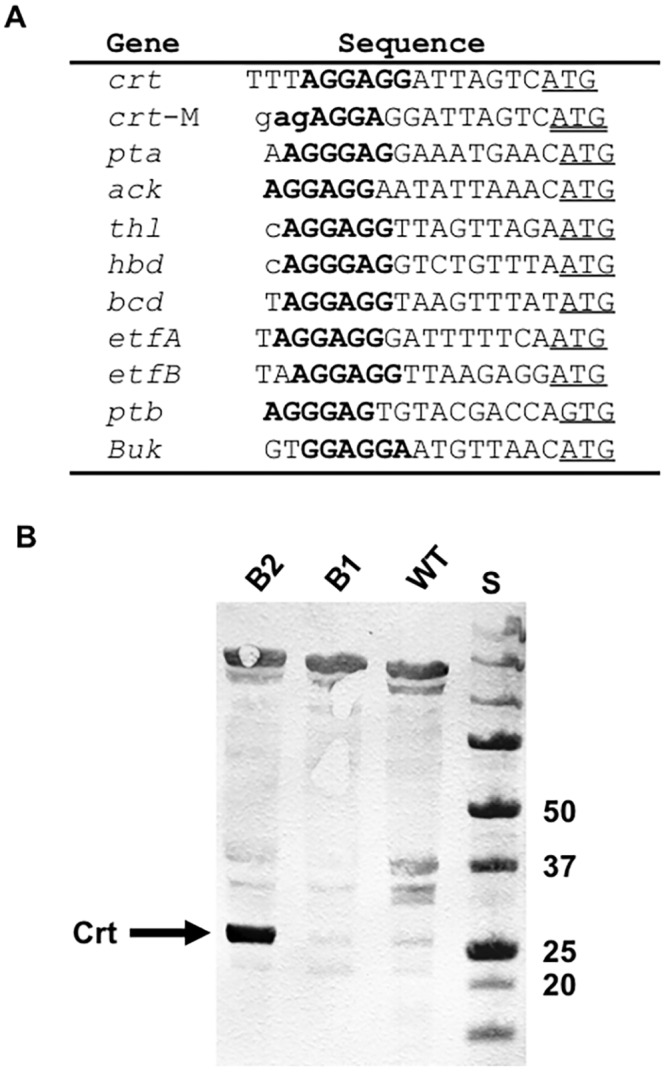

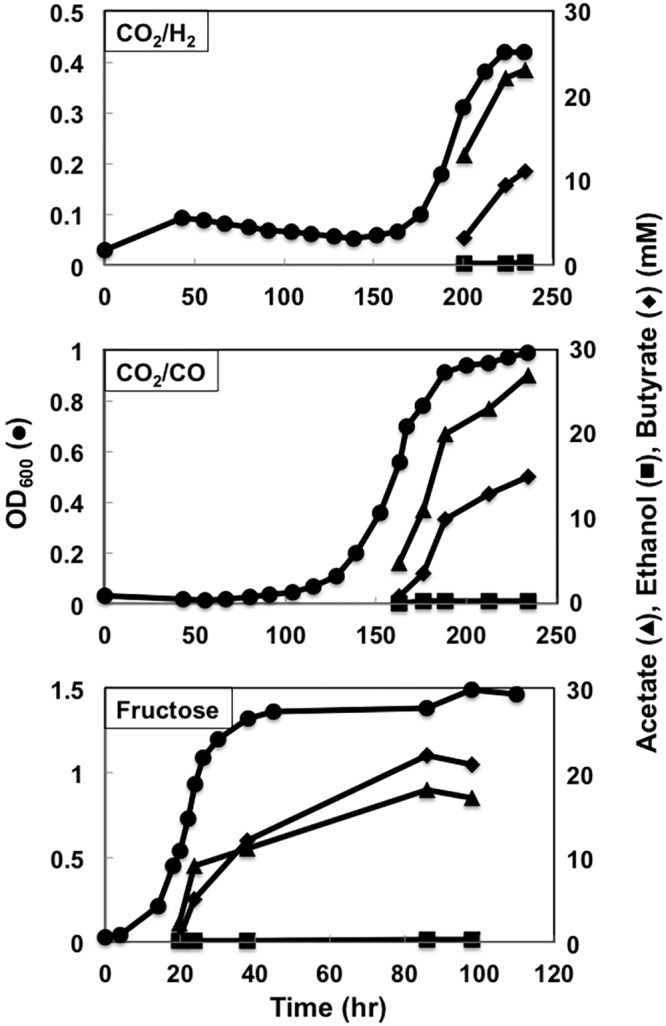

Proteomic analysis demonstrated that with the exception of crotonase (Crt), all of the heterologous enzymes were expressed at levels comparable to those for highly expressed native proteins, such as phosphotransacetylase (Pta) and acetate kinase (Ack) (Fig. 5A). However, the transcript abundance of crt was comparable to that of other heterologous genes (Fig. 5B). These results suggested that the low abundance of the Crt protein resulted from inefficient translation of crt transcripts. The distance between the putative ribosome binding site (RBS) and translation initiation codon of crt was shorter than those for the other heterologous genes (Fig. 6A). Therefore, a crt sequence in which the length between the putative RBS and translation initiation codon was increased and substituted for the original crt sequence in constructing strain B2. Western blot analysis revealed that strain B2 produced substantially more Crt than strain B1 (Fig. 6B). Strain B2 produced more butyrate with all three electron donors (Fig. 4 and 7), suggesting that the low level of Crt was a bottleneck in butyrate production in strain B1.

FIG 5 .

Proteomic and transcriptomic analyses of strain B1. (A) Proteomic analysis. Numbers of identified peptides are shown. The wild type (WT) and strain B1 were analyzed. (B) Transcriptomic analysis. Transcript abundance in strain B1 is presented as transcript copy numbers (×107).

FIG 6 .

Modification of the ribosomal binding site (RBS) of the crt gene. (A) Comparison of putative RBSs. Putative RBSs are indicated in bold. Putative translation initiation codons are underlined. Lowercase indicates sequence from restriction sites used for cloning. “crt-M” represents the modified sequence used in strain B2. (B) Western blot analysis for the Crt protein. Cell extracts prepared from the wild-type strain (WT), strain B1, and strain B2 were analyzed using an antibody against Crt. “S” represents protein standards, whose sizes are shown in kDa.

FIG 7 .

Growth profiles of strain B2. Data are representative of duplicate cultures.

Integration of butyrate pathway genes into chromosome: strain B3.

Chromosomal integration of the genes for butyrate synthesis may be preferable to maintaining the genes on plasmids, to avoid the need to add antibiotics to retain plasmids and to reduce the cellular metabolic burden (52, 53). A fragment containing the genes ptb and buk was integrated at the adhE1 locus on the chromosome with double-crossover homologous recombination, but a longer fragment containing thl-crt-bcd-etfB-etfA-hbd could not be integrated in this manner (data not shown). However, the DNA fragment of thl-crt-bcd-etfB-etfA-hbd-ptb-buk (crt with the modified RBS), under the control of the putative pta promoter region, was successfully integrated into the putative pta promoter region via single-crossover homologous recombination (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

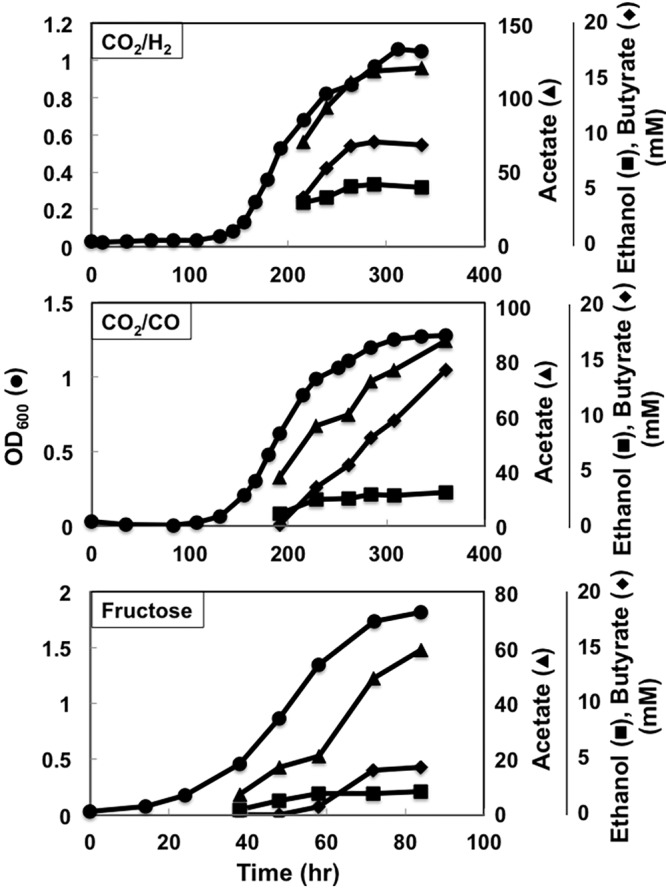

Compared with strain B2, which had the same genes expressed on plasmids, strain B3 grew faster but with a lower final biomass yield when H2 was the electron donor, (Fig. 8). A final butyrate yield by strain B3 was slightly lower than that by strain B2, but butyrate production compared to acetate production was improved (Fig. 4). In contrast, strain B3 grew faster than strain B2 with a similar final biomass yield on CO, and butyrate production was lower than that of strain B2. With fructose as the substrate, strain B3 grew faster than strain B2, but yields of biomass, acetate, and butyrate were comparable. In addition to acetate and butyrate, strain B3 produced ethanol at lower levels under all growth conditions (Fig. 8).

FIG 8 .

Growth profiles of strain B3. Data are representative of duplicate cultures.

Inactivating Pta-dependent acetate synthesis: strain B4.

In an attempt to further enhance the diversion of carbon and electron flux from acetate production to butyrate synthesis, Pta, which is thought to catalyze the first step in the conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetate (Fig. 1), was disrupted with a single-crossover homologous recombination, which simultaneously integrated the butyrate pathway genes (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The Cre-lox system, which allows reuse of an antibiotic resistance gene (54), was applied to C. ljungdahlii strain engineering (see Fig. S5, S6, and S7). This strain was designated B4.

Strain B4 grew slower than strain B3 with H2 as the electron donor but with a comparable final cell yield (Fig. 9). Surprisingly, strain B4 produced acetate at amounts comparable to those for strain B3 (Fig. 4), despite the fact that the expected primary route for acetate synthesis was disrupted. Strain B4 produced slightly more butyrate and less acetate than strain B3 during growth with CO or fructose (Fig. 4 and 9), but acetate production remained substantial (Fig. 4 and 9), suggesting that there are one or more unknown pathways for acetate synthesis in C. ljungdahlii.

FIG 9 .

Growth profiles of strain B4. Data are representative of duplicate cultures.

Inactivating Pta-dependent acetate synthesis and AdhE1-dependent ethanol synthesis: strain B5.

In an attempt to divert the NAD(P)H being consumed for ethanol production toward the production of butyrate, the ethanol pathway in strain B4 was inactivated by disrupting the adhE1 gene, which was shown (18) to encode the major bifunctional aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase for ethanol production, via single-crossover homologous recombination (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S8 in the supplemental material), creating strain B5. Strain B5 produced significantly less ethanol than strain B4, slightly improving butyrate production during growth on CO or fructose but not H2 (Fig. 4 and 10).

FIG 10 .

Growth profiles of strain B5. Data are representative of duplicate cultures.

Inactivating Pta-dependent acetate synthesis and CoA transferase: strain B6.

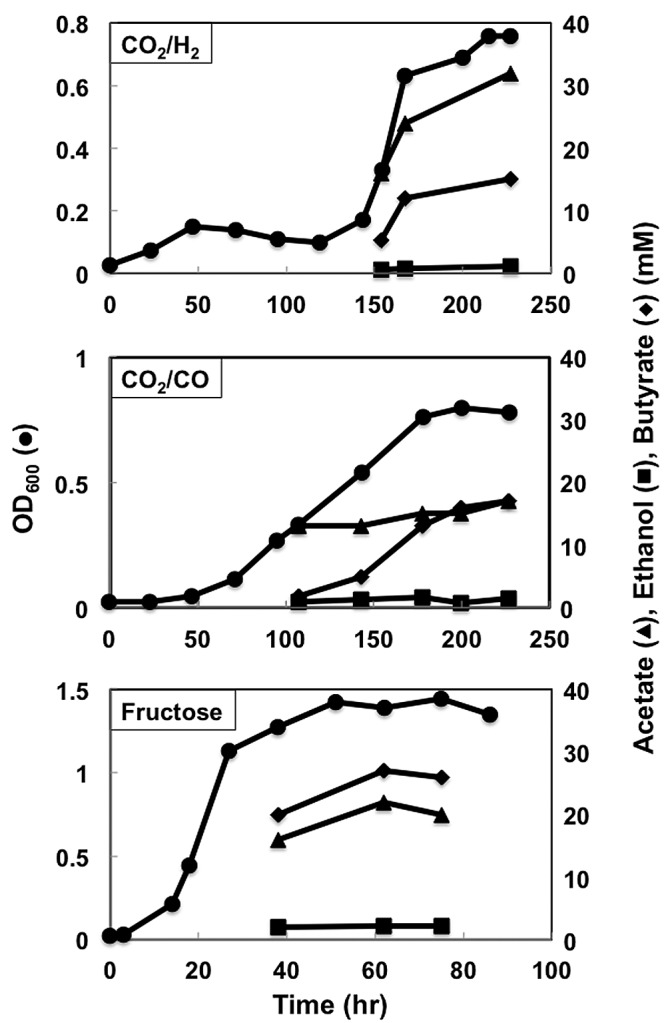

It was considered that a CoA transferase might convert butyrate back to butyryl-CoA with simultaneous production of acetate or other fatty acids (Fig. 1). In an attempt to avoid this possibility, the gene Clju_c39430, which encodes a homolog of CoA transferases, was disrupted via single-crossover homologous recombination (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material) in strain B4, yielding strain B6. Acetate continued to be produced in strain B6, but this strain was the best butyrate-producing strain in terms of butyrate yield under all three growth conditions tested (Fig. 4 and 11). Carbon and electron yields in butyrate were 42% and 48% (H2), 68% and 73% (CO), and 71% and 75% (fructose), respectively.

FIG 11 .

Growth profiles of strain B6. Data are representative of duplicate cultures.

Implications.

The results demonstrate that it was possible through genetic manipulation to redirect carbon and electron flow to the production of butyrate from carbon dioxide in C. ljungdahlii. However, further genetic manipulation will be required before the goal of producing butyrate as the sole product of metabolism will be achieved.

The continued production of acetate when pta is disrupted was previously observed in C. acetobutylicum, which has a fermentative metabolism (55). A potential alternative route for acetate production in C. ljungdahlii, even during autotrophic growth, is conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetate via an acetaldehyde intermediate (15). This could yield energy to support cell growth and maintenance through the Rnf complex and ATP synthase. Conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetaldehyde and acetaldehyde to acetate is thought to proceed with oxidation of NADH to NAD+ and reduction of ferredoxin, respectively (Fig. 1) (15). Proton gradients generated with the reactions coupled with the reduction of NAD+ and the oxidation of ferredoxin via the Rnf complex result in ATP synthesis by ATP synthase (48, 49). Therefore, net ATP synthesis may be possible via this route of acetate production. ATP generated in this manner would yield ca. 0.5 ATP, which would be comparable to ATP generation via butyrate production (Fig. 1).

A previous study demonstrated that deleting adhE1, which encodes a bifunctional aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase, prevented ethanol formation from acetyl-CoA, presumably by eliminating acetaldehyde formation (18). However, strain B5, in which both the pta gene and the adhE1 gene were inactivated, still produced acetate. There are other homologs for aldehyde dehydrogenase in the C. ljungdahlii genome (Clju_c11960, Clju_c39730, and Clju_c39840). Therefore, deletion of one or more of these genes may be required in order to completely eliminate acetate production. Deletion of many genes in the same strain is currently not possible because there are only three antibiotic resistance markers that have been identified, severely limiting the number of genes that can be deleted if they are not colocalized on the chromosome. We adopted the Cre-lox system in order to permit simultaneous disruption of three genes, but this method leaves the recombination site on the chromosome, and thus they can be used only once in a strain. Negative- or counterselection markers, such as pyrF (56), galK (57), and mazF (58), which can be used repeatedly and have been applied to other Clostridium species, would be useful, but attempts to apply them to C. ljungdahlii have not yet been successful (unpublished data).

Another possibility for the unexpected acetate production is that the enzyme phosphotransbutyrylase (Ptb) introduced in the synthetic butyrate pathway may also act on acetyl-CoA, as previously described for the Ptb purified from C. acetobutylicum (59). The specificity for acetyl-CoA was only 1.6% of that for butyryl-CoA, but even low reactivity with acetyl-CoA, which is likely to be a more abundant metabolite, could be significant. Acetate production via this pathway could be favored because it would yield more ATP and have lower reducing equivalent demands than the desired production of butyrate. When the appropriate tools are available, deleting ack may eliminate this possibility because acetate kinase is essential for this potential pathway. Substituting bukII, which encodes another butyrate kinase that is more specific for butyrate synthesis (37), for buk in the ptb-buk operon might also improve butyrate yields.

These and previous (16, 18) findings that carbon and electron flow associated with the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway in C. ljungdahlii can be genetically redirected suggest that C. ljungdahlii may be an effective chassis for the production of organic commodities from carbon monoxide-containing waste gases (11, 15) or from carbon dioxide via electrosynthesis (9). Further development of the genetic tools needed to accomplish this goal is under way.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

C. ljungdahlii DSM 13528 (ATCC 55383) from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures was the parent strain for butyrate production engineering. When fructose served as the carbon and energy source, cultures were grown in PETC 1754 medium (100% CO2 in the headspace) with 28 mM fructose as described previously (18). For growth with CO as the electron donor, the fructose was omitted from the PETC 1754 medium and CO was added to the headspace at 20 lb/in2. When H2 served as the electron donor, the cells were grown in DSMZ medium 879 with the fructose omitted and with a headspace of H2-CO2 (80%/20%). H2-CO2 (80%/20%) was further added to the headspace at 20 lb/in2. DSMZ medium 879 was used to maintain the CO2 partial pressure since the original contains N2-CO2 (80%/20%) in the headspace. Cultures were grown in anaerobic pressure tubes (27 ml) containing either 10 ml (fructose grown) or 5 ml (CO or H2 grown) of medium. Cultures grown on CO or H2 were shaken at 100 rpm.

Escherichia coli NEB 5-alpha and NEB Express (New England Biolabs) were used for plasmid preparation and grown as instructed.

Construction of butyrate pathway genes in plasmids (strains B1 and B2).

C. acetobutylicum genes necessary for synthesis of butyrate from acetyl-CoA (Fig. 1) were amplified by PCR. The amplified genes were thl (NCBI GenBank; CA_C2873), crt (NCBI GenBank; CA_C2712), bcd (NCBI GenBank; CA_C2711), etfB (NCBI GenBank, CA_C2710), etfA (NCBI GenBank; CA_C2709), hbd (NCBI GenBank; CA_C2708), buk (NCBI GenBank; CA_C3075), and ptb (NCBI GenBank; CA_C3076). Primers used for the PCR are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Life Technologies). The NdeI-PstI DNA fragment containing etfA was cloned at the NdeI (in etfB) and PstI sites in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO containing bcd and etfB. The KpnI-XhoI DNA fragment containing thl was cloned at the KpnI and XhoI sites in pBluescript II KS(−) (Stratagene). Then, the XhoI-EcoRI DNA fragment containing crt was cloned at the XhoI and EcoRI sites in pBluescript II KS(−) containing thl. The EcoRI-PstI DNA fragment containing bcd, etfB, and etfA was cloned at the EcoRI and PstI sites in pBluescript II KS(−) containing thl and crt. The PstI-BamHI DNA fragment containing hbd was cloned at the PstI and BamHI sites in pBluescript II KS(−) containing thl, crt, bcd, etfB, and etfA (see Fig. S1A). The KpnI-BamHI DNA fragment containing thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, and hbd was cloned at the KpnI and BamHI sites in an expression vector, pJe-p (see Fig. S2). The BamHI-SalI DNA fragment containing ptb and buk was cloned at the BamHI and SalI sites in pM6-p (see Fig. S2). pJe-p and pM6-p were constructed by placing the putative promoter for the pta gene from C. ljungdahlii in pJe (16) and pMTL82151 (a gift from N. P. Minton) (60), respectively. pJe is a derivative of pCL2 (18) and contains an erythromycin resistance gene instead of the chloramphenicol resistance gene. The putative pta promoter was prepared by PCR using primers listed in Table S1. PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. The EcoRI-KpnI DNA fragment containing the putative pta promoter was cloned at the EcoRI-KpnI sites in these vectors. Transformation of these plasmids was conducted as described previously (18).

Integration of butyrate pathway genes on chromosome (strain B3).

The BamHI DNA fragment from pCR-Blunt II-TOPO containing ptb and buk as described above (a BamHI site is located downstream of buk in the vector) was cloned at the BamHI site of pBluescript II KS(−) containing thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, and hbd (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). The crt gene with the modified RBS was used. The SalI site remains at the 3′ end of buk upstream of the BamHI site. A resultant plasmid containing ptb and buk in the same direction with thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, and hbd was used for subsequent plasmid preparation. The ermC gene was amplified by PCR with primers listed in Table S1 and pCL1 (18). PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. The SpeI-NotI fragment containing ermC was cloned at the SpeI and NotI sites in pBluescript II KS(−) containing thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, hbd, ptb, and buk (see Fig. S2). The resultant plasmid was used to integrate the butyrate pathway genes at the pta promoter region on the chromosome (see Fig. S2).

Construction of Cre-lox system for C. ljungdahlii.

A loxP cassette was constructed as follows. Oligonucleotides loxP1-T and lox-P1-B (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were phosphorylated, annealed, and cloned at the EcoRI site in the plasmid pNEB193 (New England Biolabs). A resultant plasmid with the loxP1 sequence in the proper orientation was used for cloning the phosphorylated and annealed oligonucleotides loxP2-T and loxP2-B at the HindIII site. A resultant plasmid with the loxP2 sequence in the proper orientation was used for the subsequent cloning. The catP gene was amplified by PCR with primers listed in Table S1 and pMTL82151 (60). PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. The BglII-SacII DNA fragment of the catP gene was cloned at the BglII and SacII sites in pNEB containing loxP1 and loxP2. Then, the ermC gene was amplified by PCR with primers listed in Table S1 and pCL1 (18). PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. The SphI-HindIII DNA fragment of ermC was cloned at the SphI and HindIII sites in pNEB containing loxP1, loxP2, and catP (see Fig. S4).

A cre gene with codon usage optimized for Clostridium was synthesized by GenScript (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). The KpnI-BamHI DNA fragment of cre was cloned at the KpnI and BamHI sites in an expression vector, pJKe-p. For the construction of pJKe-p, a kanamycin resistance gene (kan) with codon usage optimized for Clostridium was synthesized by GenScript (see Fig. S6). The kan gene was fused with the putative promoter region of ermB (PermB) from pQexp (61). PermB-kan was amplified by PCR with primers listed in Table S1. PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. The ClaI-HpaI DNA fragment of PermB-kan replaced the ClaI-HpaI DNA fragment including catP in pJIR750ai (Sigma). pJKe-p was constructed by placing the pta promoter at the EcoRI-KpnI sites in the resultant plasmid, pJKe, as described above.

Inactivation of pta gene and integration of butyrate pathway genes (strain B4).

The KpnI-SalI DNA fragment containing thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, hbd, ptb and buk from the pBluescript II KS(−) containing thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, hbd, ptb, and buk as described above was cloned at the KpnI-SalI sites in pNEB containing loxP1, loxP2, catP, and ermC as described above. The internal region of the pta-coding sequence (pta-int) was amplified by PCR with primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. The SpeI-KpnI DNA fragment of pta-int was cloned at the SpeI and KpnI sites in the pNEB containing loxP1, loxP2, catP, ermC, and the butyrate pathway genes (see Fig. S4). The resultant plasmid was used to integrate the butyrate pathway genes at the internal region of the pta-coding sequence on the chromosome, which resulted in disruption of pta (see Fig. S4).

After integration of the above plasmid on the chromosome DNA, the vector region and catP were excised by Cre (see Fig. S4 and S7 in the supplemental material). Competent cells of this strain were prepared as described previously (18) and transformed with the plasmid containing cre with the following modification. After electroporation and subsequent outgrowth in the presence of erythromycin, kanamycin was added to the outgrowth culture at the final concentration of 20 µg/ml and further incubated overnight to facilitate recombination at the loxP sites by Cre. The outgrowth cultures were then plated normally in the presence of erythromycin and kanamycin. Absence of the vector region and catP and presence of the butyrate genes were verified by PCR analysis (see Fig. S7).

Inactivation of adhE1 gene (strain B5).

The adhE1 gene was disrupted by single-crossover homologous recombination at the internal region of the adhE1-coding sequence (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). The internal region of the adhE1-coding sequence (adhE1-int) was amplified by PCR using primers listed in Table S1. PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. The SpeI-KpnI DNA fragment of adhE1-int was cloned at the SpeI and KpnI sites in the pNEB containing catP. The resultant plasmid was used to disrupt adhE1 on the chromosome of strain B4, in which pta was inactivated by inserting the butyrate pathway genes at the internal region of the pta-coding sequence on the chromosome.

Inactivation of ctf gene (strain B6).

The ctf gene (Clju_c39430) was disrupted as described for adhE1 (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). The internal region of the ctf-coding sequence (ctf-int) was amplified by PCR with primers listed in Table S1. PCR products were cloned in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO. The SpeI-KpnI DNA fragment of ctf-int was cloned at the SpeI and KpnI sites in pNEB containing catP. The resultant plasmid was used to disrupt ctf on the chromosome of strain B4.

Proteomic analysis.

Protein expression profiles of C. ljungdahlii wild-type and B1 strains grown on fructose were analyzed at the Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of Massachusetts Medical School. Cells were harvested from cultures at a log phase. Each protein sample (5 µg) was run in to a gel. The gel slice was cut out, washed thoroughly, and digested with trypsin. Each digested sample was analyzed in triplicate by using nano-liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (nano-LC-MS/MS).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR).

Total RNA was prepared from the fructose-grown B1 strain by using the RiboPure-Bacteria kit (Life Technologies) as instructed. cDNA was prepared with random nonamers by using the Enhanced Avian RT First Strand synthesis kit (Sigma) as instructed. PCR was conducted with primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material as described previously (62).

Western blot analysis.

Cell extracts were prepared from the fructose-grown wild-type, B1, and B2 strains by disruption with sonication. Cell extracts were loaded on an SDS-PAGE gel. Western blot analysis was carried out with an antibody against the peptide DISEMKEMNTIERG, from amino acid residues 67 to 80 of the Crt protein. The peptide and the antibody were prepared by GenScript.

Analytical techniques.

Growth of cells was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Acetate and butyrate were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (9), and ethanol was measured by gas chromatography (63).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Plasmids used for the butyrate pathway genes. (A) Assembly of thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, and hbd. (B) Assembly of thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, hbd, ptb, and buk. Download

Plasmid vectors used for expression of the butyrate pathway genes in C. ljungdahlii to create strains B1 and B2. Download

Construction of strain B3. The butyrate pathway genes were integrated at the pta promoter region on the chromosome DNA. Download

Construction of strain B4. The pta gene was disrupted by inserting the butyrate pathway genes at the internal region of the pta gene on the chromosome. The pta gene was truncated into two incomplete segments. Download

Sequence of the synthesized cre gene. The ribosome binding site is underlined. The translation initiation codon (ATG) and stop codon (TAA) are indicated in bold. Download

Sequence of the synthesized PermB-kan gene. The ribosome binding site is underlined. The translation initiation codon (ATG) and stop codon (TAA) are indicated in bold. Download

Deletion of the vector from the chromosome DNA by using the Cre-lox system. Disruption of the pta gene and absence of the vector region were verified by PCR. Primers specific to the pta gene or the catP gene were used for PCR analysis. Three independent colonies after the Cre-lox recombination (-pta-v) were analyzed. Download

Construction of strains B5 and B6. The adhE1 or ctf gene was disrupted in strain B4. The adhE1 or ctf gene was truncated into two incomplete segments. The adhE1 or ctf gene is presented as X. Download

Primers used in this study

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), U.S. Department of Energy (DE-AR0000159).

We thank N. P. Minton for pMTL82151. We are grateful to P. M. Shrestha, C. Leang, J. Ward, M. Sharma, O. Snoeyenbos-West, J. Izbicki, R. Delgado, and C. Gillis for technical support.

Footnotes

Citation Ueki T, Nevin KP, Woodard TL, Lovley DR. 2014. Converting carbon dioxide to butyrate with an engineered strain of Clostridium ljungdahlii. mBio 5(5):e01636-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01636-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bengelsdorf FR, Straub M, Dürre P. 2013. Bacterial synthesis gas (syngas) fermentation. Environ. Technol. 34:1639–1651. 10.1080/09593330.2013.827747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Daniell J, Kopke M, Simpson SD. 2012. Commercial biomass syngas fermentation. Energies 5:5372–5417. 10.3390/en5125372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Henstra AM, Sipma J, Rinzema A, Stams AJ. 2007. Microbiology of synthesis gas fermentation for biofuel production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18:200–206. 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lovley DR, Nevin KP. 2011. A shift in the current: new applications and concepts for microbe-electrode electron exchange. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22:441–448. 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lovley DR, Nevin KP. 2013. Electrobiocommodities: powering microbial production of fuels and commodity chemicals from carbon dioxide with electricity. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24:385–390. 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mohammadi M, Najafpour GD, Younesi H, Lahijani P, Uzir MH, Mohamed AR. 2011. Bioconversion of synthesis gas to second generation biofuels: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 15:4255–4273. 10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Munasinghe PC, Khanal SK. 2010. Biomass-derived syngas fermentation into biofuels: Opportunities and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 101:5013–5022. 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.12.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nevin KP, Woodard TL, Franks AE, Summers ZM, Lovley DR. 2010. Microbial electrosynthesis: feeding microbes electricity to convert carbon dioxide and water to multicarbon extracellular organic compounds. mBio 1(2):e00103-10. 10.1128/mBio.00103-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nevin KP, Hensley SA, Franks AE, Summers ZM, Ou J, Woodard TL, Snoeyenbos-West OL, Lovley DR. 2011. Electrosynthesis of organic compounds from carbon dioxide is catalyzed by a diversity of acetogenic microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2882–2886. 10.1128/AEM.02642-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fast AG, Papoutsakis ET. 2012. Stoichiometric and energetic analyses of non-photosynthetic CO2-fixation pathways to support synthetic biology strategies for production of fuels and chemicals. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 1:380–395. 10.1016/j.coche.2012.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Köpke M, Mihalcea C, Liew F, Tizard JH, Ali MS, Conolly JJ, Al-Sinawi B, Simpson SD. 2011. 2,3-Butanediol production by acetogenic bacteria, an alternative route to chemical synthesis, using industrial waste gas. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:5467–5475. 10.1128/AEM.00355-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ukpong MN, Atiyeh HK, De Lorme MJ, Liu K, Zhu X, Tanner RS, Wilkins MR, Stevenson BS. 2012. Physiological response of Clostridium carboxidivorans during conversion of synthesis gas to solvents in a gas-fed bioreactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 109:2720–2728. 10.1002/bit.24549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bruant G, Lévesque MJ, Peter C, Guiot SR, Masson L. 2010. Genomic analysis of carbon monoxide utilization and butanol production by Clostridium carboxidivorans strain P7. PLoS One 5:e13033. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Worden RM, Grethlein AJ, Zeikus JG, Datta DR. 1989. Butyrate production from carbon monoxide by Butyribacterium methylotrophicum. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 20-21:687–698. 10.1007/BF02936517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Köpke M, Held C, Hujer S, Liesegang H, Wiezer A, Wollherr A, Ehrenreich A, Liebl W, Gottschalk G, Dürre P. 2010. Clostridium ljungdahlii represents a microbial production platform based on syngas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:13087–13092. 10.1073/pnas.1004716107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Banerjee A, Leang C, Ueki T, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2014. Lactose-inducible system for metabolic engineering of Clostridium ljungdahlii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80:2410–2416. 10.1128/AEM.03666-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kita A, Iwasaki Y, Sakai S, Okuto S, Takaoka K, Suzuki T, Yano S, Sawayama S, Tajima T, Kato J, Nishio N, Murakami K, Nakashimada Y. 2013. Development of genetic transformation and heterologous expression system in carboxydotrophic thermophilic acetogen Moorella thermoacetica. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 115:347–352. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leang C, Ueki T, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2013. A genetic system for Clostridium ljungdahlii: a chassis for autotrophic production of biocommodities and a model homoacetogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:1102–1109. 10.1128/AEM.02891-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tan Y, Liu J, Chen X, Zheng H, Li F. 2013. RNA-seq-based comparative transcriptome analysis of the syngas-utilizing bacterium Clostridium ljungdahlii DSM 13528 grown autotrophically and heterotrophically. Mol. Biosyst. 9:2775–2784. 10.1039/c3mb70232d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tan Y, Liu J, Liu Z, Li F. 2013. Characterization of two novel butanol dehydrogenases involved in butanol degradation in syngas-utilizing bacterium Clostridium ljungdahlii DSM 13528. J. Basic Microbiol. 53:1–9. 10.1002/jobm.201100335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu J, Tan Y, Yang X, Chen X, Li F. 2013. Evaluation of Clostridium ljungdahlii DSM 13528 reference genes in gene expression studies by qRT-PCR. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 116:460–464. 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tremblay PL, Zhang T, Dar SA, Leang C, Lovley DR. 2012. The Rnf complex of Clostridium ljungdahlii is a proton-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase essential for autotrophic growth. mBio 4(1):e00406-12. 10.1128/mBio.00406-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nagarajan H, Sahin M, Nogales J, Latif H, Lovley DR, Ebrahim A, Zengler K. 2013. Characterizing acetogenic metabolism using a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of Clostridium ljungdahlii. Microb. Cell Fact. 12:118. 10.1186/1475-2859-12-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. El Aidy S, Van den Abbeele P, Van de Wiele T, Louis P, Kleerebezem M. 2013. Intestinal colonization: how key microbial players become established in this dynamic process: microbial metabolic activities and the interplay between the host and microbes. Bioessays 35:913–923. 10.1002/bies.201300073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Louis P, Flint HJ. 2009. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 294:1–8. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01514.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharpell FHJ. 1985. Microbial flavors and fragrances, p 965–979. In Blanch HW, Drew S, Wang DIC. (ed), Comprehensive biotechnology. Pergamon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armstrong DW, Yamazaki H. 1986. Natural flavors production—a biotechnological approach. Trends Biotechnol. 4:264–268. 10.1016/0167-7799(86)90190-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Playne MJ. 1985. Propionic and butyric acids, p 731–759. In Moo-Young M. (ed), Comprehensive biotechnology. Pergamon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 29. Posey-Dowty JD, Seo KS, Walker KR, Wilson AK. 2002. Carboxymethylcellulose acetate butyrate in water-based automotive paints. Surf. Coat. Int. B Coat. Trans. 85:203–208. 10.1007/BF02699510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scandola M, Ceccorulli G, Pizzoli M. 1992. Miscibility of bacterial poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) with cellulose esters. Macromolecules 25:6441–6446. 10.1021/ma00050a009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jeon JM, Brigham CJ, Kim YH, Kim HJ, Yi DH, Kim H, Rha C, Sinskey AJ, Yang YH. 2014. Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (P(HB-co-HHx)) from butyrate using engineered Ralstonia eutropha. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98:5461–5469. 10.1007/s00253-014-5617-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baba S, Tashiro Y, Shinto H, Sonomoto K. 2012. Development of high-speed and highly efficient butanol production systems from butyric acid with high density of living cells of Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum. J. Biotechnol. 157:605–612. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Perez JM, Richter H, Loftus SE, Angenent LT. 2013. Biocatalytic reduction of short-chain carboxylic acids into their corresponding alcohols with syngas fermentation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 110:1066–1077. 10.1002/bit.24786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dwidar M, Park JY, Mitchell RJ, Sang BI. 2012. The future of butyric acid in industry. ScientificWorldJournal 2012:471417. 10.1100/2012/471417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang C, Yang H, Yang F, Ma Y. 2009. Current progress on butyric acid production by fermentation. Curr. Microbiol. 59:656–663. 10.1007/s00284-009-9491-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zigová J, Šturdík E. 2000. Advances in biotechnological production of butyric acid. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24:153–160. 10.1038/sj.jim.2900795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jang YS, Im JA, Choi SY, Lee JI, Lee SY. 2014. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium acetobutylicum for butyric acid production with high butyric acid selectivity. Metab. Eng. 23:165–174. 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jang YS, Woo HM, Im JA, Kim IH, Lee SY. 2013. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium acetobutylicum for enhanced production of butyric acid. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97:9355–9363. 10.1007/s00253-013-5161-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jiang L, Wang J, Liang S, Cai J, Xu Z, Cen P, Yang S, Li S. 2011. Enhanced butyric acid tolerance and bioproduction by Clostridium tyrobutyricum immobilized in a fibrous bed bioreactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 108:31–40. 10.1002/bit.22927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vandák D, Tomáška M, Zigová J, Sturdík E. 1995. Effect of growth supplements and whey pretreatment on butyric acid production by Clostridium butyricum. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 11:363. 10.1007/BF00367124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fayolle F, Marchal R, Ballerini D. 1990. Effect of controlled substrate feeding on butyric-acid production by Clostridium-Tyrobutyricum. J. Ind. Microbiol. 6:179–183. 10.1007/BF01577693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Canganella F, Wiegel J. 2000. Continuous cultivation of Clostridium thermobutyricum in a rotary fermentor system. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24:7–13. 10.1038/sj.jim.2900752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu XG, Zhu Y, Yang ST. 2006. Butyric acid and hydrogen production by Clostridium tyrobutyricum ATCC 25755 and mutants. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 38:521–528. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lehmann D, Radomski N, Lütke-Eversloh T. 2012. New insights into the butyric acid metabolism of Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 96:1325–1339. 10.1007/s00253-012-4109-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jang YS, Lee JY, Lee J, Park JH, Im JA, Eom MH, Lee J, Lee SH, Song H, Cho JH, Seung DY, Lee SY. 2012. Enhanced butanol production obtained by reinforcing the direct butanol-forming route in Clostridium acetobutylicum. mBio 3(5):e00314-12. 10.1128/mBio.00314-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tanner RS, Miller LM, Yang D. 1993. Clostridium ljungdahlii sp. nov., an acetogenic species in clostridial rRNA homology group I. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:232–236. 10.1099/00207713-43-2-232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Phillips JR, Clausen EC, Gaddy JL. 1994. Synthesis gas as substrate for the biological production of fuels and chemicals. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 45-46:145–157 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Buckel W, Thauer RK. 2013. Energy conservation via electron bifurcating ferredoxin reduction and proton/Na(+) translocating ferredoxin oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827:94–113. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Biegel E, Schmidt S, González JM, Müller V. 2011. Biochemistry, evolution and physiological function of the Rnf complex, a novel ion-motive electron transport complex in prokaryotes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68:613–634. 10.1007/s00018-010-0555-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Colby GD, Chen JS. 1992. Purification and properties of 3-hydroxybutyryl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase from Clostridium beijerinckii (“Clostridium butylicum”) NRRL B593. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3297–3302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li F, Hinderberger J, Seedorf H, Zhang J, Buckel W, Thauer RK. 2008. Coupled ferredoxin and crotonyl coenzyme A (CoA) reduction with NADH catalyzed by the butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase/Etf complex from Clostridium kluyveri. J. Bacteriol. 190:843–850. 10.1128/JB.01417-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Diaz Ricci JC, Hernández ME. 2000. Plasmid effects on Escherichia coli metabolism. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 20:79–108. 10.1080/07388550008984167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Silva F, Queiroz JA, Domingues FC. 2012. Evaluating metabolic stress and plasmid stability in plasmid DNA production by Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Adv. 30:691–708. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sauer B. 1987. Functional expression of the cre-lox site-specific recombination system in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:2087–2096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Green EM, Boynton ZL, Harris LM, Rudolph FB, Papoutsakis ET, Bennett GN. 1996. Genetic manipulation of acid formation pathways by gene inactivation in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Microbiology 142(Part 8):2079–2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tripathi SA, Olson DG, Argyros DA, Miller BB, Barrett TF, Murphy DM, McCool JD, Warner AK, Rajgarhia VB, Lynd LR, Hogsett DA, Caiazza NC. 2010. Development of pyrF-based genetic system for targeted gene deletion in Clostridium thermocellum and creation of a pta mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:6591–6599. 10.1128/AEM.01484-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nariya H, Miyata S, Suzuki M, Tamai E, Okabe A. 2011. Development and application of a method for counterselectable in-frame deletion in Clostridium perfringens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:1375–1382. 10.1128/AEM.01572-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Al-Hinai MA, Fast AG, Papoutsakis ET. 2012. Novel system for efficient isolation of Clostridium double-crossover allelic exchange mutants enabling markerless chromosomal gene deletions and DNA integration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:8112–8121. 10.1128/AEM.02214-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wiesenborn DP, Rudolph FB, Papoutsakis ET. 1989. Phosphotransbutyrylase from Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 and its role in acidogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:317–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Heap JT, Pennington OJ, Cartman ST, Minton NP. 2009. A modular system for Clostridium shuttle plasmids. J. Microbiol. Methods 78:79–85. 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tolonen AC, Chilaka AC, Church GM. 2009. Targeted gene inactivation in Clostridium phytofermentans shows that cellulose degradation requires the family 9 hydrolase Cphy3367. Mol. Microbiol. 74:1300–1313. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06890.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rotaru AE, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Ueki T, Nevin K, Summers ZM, Lovley DR. 2012. Interspecies electron transfer via hydrogen and formate rather than direct electrical connections in cocultures of Pelobacter carbinolicus and Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:7645–7651. 10.1128/AEM.01946-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Morita M, Malvankar NS, Franks AE, Summers ZM, Giloteaux L, Rotaru AE, Rotaru C, Lovley DR. 2011. Potential for direct interspecies electron transfer in methanogenic wastewater digester aggregates. mBio 2(4):e00159-00111. 10.1128/mBio.00159-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Plasmids used for the butyrate pathway genes. (A) Assembly of thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, and hbd. (B) Assembly of thl, crt, bcd, etfB, etfA, hbd, ptb, and buk. Download

Plasmid vectors used for expression of the butyrate pathway genes in C. ljungdahlii to create strains B1 and B2. Download

Construction of strain B3. The butyrate pathway genes were integrated at the pta promoter region on the chromosome DNA. Download

Construction of strain B4. The pta gene was disrupted by inserting the butyrate pathway genes at the internal region of the pta gene on the chromosome. The pta gene was truncated into two incomplete segments. Download

Sequence of the synthesized cre gene. The ribosome binding site is underlined. The translation initiation codon (ATG) and stop codon (TAA) are indicated in bold. Download

Sequence of the synthesized PermB-kan gene. The ribosome binding site is underlined. The translation initiation codon (ATG) and stop codon (TAA) are indicated in bold. Download

Deletion of the vector from the chromosome DNA by using the Cre-lox system. Disruption of the pta gene and absence of the vector region were verified by PCR. Primers specific to the pta gene or the catP gene were used for PCR analysis. Three independent colonies after the Cre-lox recombination (-pta-v) were analyzed. Download

Construction of strains B5 and B6. The adhE1 or ctf gene was disrupted in strain B4. The adhE1 or ctf gene was truncated into two incomplete segments. The adhE1 or ctf gene is presented as X. Download

Primers used in this study