Abstract

Plants are constantly exposed to potentially pathogenic microbes present in their surrounding environment. Due to the activation of the pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) response that largely relies on accurate detection of pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular patterns by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), plants are resistant to the majority of potential pathogens. However, adapted pathogens may avoid recognition or repress plant PTI and resulting diseases significantly affect crop yield worldwide. PTI provides protection against a wide range of pathogens. Reinforcement of PTI through genetic engineering may thus generate crops with broad-spectrum field resistance. In this review, new approaches based on fundamental discoveries in PTI to improve crop immunity are discussed. Notably, we highlight recent studies describing the interfamily transfer of PRRs or key regulators of PTI signaling.

Keywords: innate immunity, pattern-triggered immunity, pattern-recognition receptor, leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase, lectin receptor kinase, pathogen, microbe

INTRODUCTION

Monocultures of highly fertilized crops that are typical of intensive agriculture practices are very sensitive to disease by adapted pathogens (Bruce, 2012). The development of resistant crops is thus critical for better yields. Although prone to disease, plants have evolved diverse defense mechanisms to cope with potential pathogens. To sense invaders, plants are equipped with surveillance machineries such as plasma membrane surface-localized proteins called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which detect foreign (non-self) pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs or MAMPs; Boller and Felix, 2009; Bohm et al., 2014; Zipfel, 2014), as well as self-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs; Boller and Felix, 2009; Newman et al., 2013; Zipfel, 2014). MAMPs are evolutionarily conserved across a certain class of microbes and are essential for the microbial lifestyle. Some examples of bacterial MAMPs and their corresponding PRRs include flagellin/FLAGELLIN SENSING2 (FLS2; Gómez-Gómez and Boller, 2000), EF-Tu/EF-Tu RECEPTOR (EFR; Zipfel et al., 2006), Xanthomonas eMAX/RECEPTOR OF eMAX (ReMAX; Jehle et al., 2013) and peptidoglycan (PGN)/LYSIN-MOTIF1 (LYM1) and LYM3 (Willmann et al., 2011). Fungal MAMPs/PRRs pairs are exemplified by chitin/CHITIN ELICITOR RECEPTOR KINASE1 (CERK1; Miya et al., 2007; Wan et al., 2008), xylanase/ETHYLENE INDUCING XYLANASE2 (Eix2; Ron and Avni, 2004), and avirulence gene Ave1/VERTICILIUM1 (Ve1; de Jonge et al., 2012). DAMPs are endogenous molecules released upon cell damage or pathogen recognition. The known DAMPs/PRRs pairs include Pep peptides/PEP1 RECEPTOR 1 (PEPR1) and PEPR2 (Huffaker et al., 2006; Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Krol et al., 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2010), cell wall fragment oligogalacturonides (OGs)/WALL-ASSOCIATED KINASE 1 (Brutus et al., 2010), and extracellular ATP (eATP)/DOES NOT RESPOND TO NUCLEOTIDES 1 (DORN1; Choi et al., 2014).

The recognition of MAMPs or DAMPs by PRRs activates the pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) response (Tsuda and Katagiri, 2010). Increased cellular Ca2+ concentration, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades are considered as early PTI responses, whereas callose deposition and marker gene up-regulation are observed later during PTI (Boller and Felix, 2009; Zipfel and Robatzek, 2010; Tena et al., 2011). These first layers of defense are believed to be sufficient to prevent the invasion of a wide range of pathogens. Functional PRRs are crucial for the success of PTI, as a defective recognition system makes plants more vulnerable to their surrounding environment. Notably, loss-of-function mutations in FLS2 impair Arabidopsis thaliana resistance against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) DC3000 bacteria (Zipfel et al., 2004) and Arabidopsis efr mutants show increased susceptibility to Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Zipfel et al., 2006). Similarly, Arabidopsis cerk1 mutants display enhanced sensitivity to fungal pathogens (Miya et al., 2007; Wan et al., 2008), and Arabidopsis pepr1 pepr2 plants are more susceptible than wild-type plants to Pst DC3000, Botrytis cinerea, and Colletotrichum higginsianum (Ma et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2014). In addition to PRRs, other regulators are required for full activation of PTI (Macho and Zipfel, 2014). For example, BRI1-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE/SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE3 (BAK1/SERK3) acts as a co-receptor for the conserved 22-amino acid epitope flg22 of the bacterial flagellin, and forms a complex with FLS2 upon flg22 perception (Chinchilla et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2013). BOTRYTIS-INDUCED KINASE1 (BIK1) is also critical for flg22-mediated signal transduction from the FLS2/BAK1 receptor complex (Lu et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). Accordingly, loss-of-function mutants of BAK1 or BIK1 display impaired flg22-induced responses (Chinchilla et al., 2007; Heese et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). Recent studies showed that L-type lectin receptor kinases (LecRKs) modulate the PTI response (Singh and Zimmerli, 2013). LecRK-I.9, also known as DORN1, is necessary for eATP recognition, and is required for MAMP-induced callose deposition (Bouwmeester et al., 2011a; Choi et al., 2014). In addition, LecRK-V.5 negatively regulates MAMP-induced ROS burst in guard cells (Desclos-Theveniau et al., 2012), and LecRK-VI.2 associates with FLS2 and positively modulates PTI upstream of MAPK signaling (Singh et al., 2012a; Huang et al., 2014a).

Though PTI is sufficient to limit the proliferation of a wide variety of microbes, successful pathogens often break plant resistance via delivering virulence molecules called effectors into the apoplast or host cells to suppress PTI (Dou and Zhou, 2012). As a counter measure, plants deploy resistance (R) proteins that generally perceive directly or indirectly perturbations of effectors to mount another layer of defense called effector-triggered immunity (ETI; Jones and Dangl, 2006; Dodds and Rathjen, 2010). ETI is characterized by the induction of a strong and transient immune response often correlated with localized cell death to restrict pathogen spread (Jones and Dangl, 2006). However, rapidly evolving pathogens are able to overcome ETI via frequent mutations in effectors, escaping host R protein detection (Gassmann et al., 2000; Jones and Dangl, 2006; Huang et al., 2014b).

It is a slow process to generate disease resistant crop varieties via traditional breeding, which involves crossing between different varieties and multiple backcrossing to select progenies with the most positive and least negative traits. With the advances in genetic engineering, novel basic knowledge on plant immunity can be applied successfully toward the rapid development of disease resistant crops. To combat crop diseases, relevant defense-related genes can be transferred from one plant species to another. Interspecies or interfamily gene transfer has been shown to be feasible with heterologous genes remaining functional after transfer (Wulff et al., 2011; Dangl et al., 2013). Detailed molecular mechanisms are however not yet well understood. The compatibility of gene transfer across plant species/families suggests that components of defense signaling pathways are conserved between species. In agreement with this, MAPK cascades are crucial for various defense responses in Arabidopsis, tomato, Nicotiana benthamiana, and rice (Rodriguez et al., 2010; Meng and Zhang, 2013). Similarly, the plant ROS burst represents a general hallmark of pathogen recognition and defense activation (Torres, 2010).

With the increasing number of plant defense regulators identified, many examples have been established to test the efficacy of heterologous gene transfer on enhancing disease resistance. In this review, we discuss recent findings on improving plant immunity via transfer of defense-related genes, with a special focus on approaches exploiting PTI to confer broad-spectrum resistance.

RATIONALES FOR PTI-BASED BIOENGINEERING

Strategies to improve crop immunity via transfer of R genes were extensively used in the past decades (Wulff et al., 2011; Dangl et al., 2013). However, the durability of R gene-mediated resistance can be greatly hampered by the rapid evolution of pathogen effectors, which are only partially critical for pathogen fitness and virulence (Gassmann et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2007; Ayliffe et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2014b). Moreover, effectors are species, race, or strain specific, making it difficult to combat diverse pathogens with a single R gene transfer (Chisholm et al., 2006; Jones and Dangl, 2006; Bent and Mackey, 2007; Thomma et al., 2011). By contrast, MAMPs, which are conserved within a class of microbes, are less likely to adopt mutations since they are crucial for the fitness and survival of microbes. For example, the MAMP flagellin from bacterial flagella is critical for bacterial motility, and peptidoglycans are inherent of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria (Felix et al., 1999; Nürnberger et al., 2004; Zipfel and Felix, 2005; Gust et al., 2007; Erbs et al., 2008). Similarly, DAMPs, which serve as common danger signals released from stressed-cells, induce plant immune responses against a large variety of pathogens (Huffaker et al., 2006; Yamaguchi et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2013). Accordingly, approaches exploiting PTI may stand a better chance in engineering crops with durable resistance against diverse pathogens.

GAIN OF NEW MAMP PERCEPTION CAPABILITIES

Recognition of MAMPs by PRRs is the first step in PTI activation and consequently, plants defective in MAMP recognition are more susceptible to pathogens. Conversely, the introduction of a new PRR to a given plant species may boost PTI responses via additional PTI activation signaling from the new MAMP/PRR recognition system. This experimental hypothesis was demonstrated to be feasible through the interfamily transfer of EFR, a bacterial EF-Tu receptor (Lacombe et al., 2010). EF-Tu is one of the most abundant, widely conserved, and slow-evolving protein in bacteria (Lathe and Bork, 2001; Kunze et al., 2004; Lacombe et al., 2010). Recognition of EF-Tu (or its eliciting epitope elf18) is Brassicaceae specific (Kunze et al., 2004; Zipfel et al., 2006) and Solanaceous plants such as N. benthamiana and tomato do not possess EFR (Kunze et al., 2004). Remarkably, N. benthamiana and tomato plants with stable expression of EFR gain responsiveness to elf18 as illustrated by the accumulation of ROS and PTI-responsive mRNAs (Lacombe et al., 2010). Moreover, heterologous expression of EFR in N. benthamiana and tomato greatly increases resistance toward a wide range of pathogens carrying the eliciting EF-Tu (Lacombe et al., 2010). Transgenic expression of EFR in N. benthamiana and tomato does not result in constitutive defense responses or defects in growth and development when assessed in laboratory conditions (Lacombe et al., 2010), fulfilling basic agronomical requirements. Theoretically, host co-evolved pathogens are unlikely to possess effectors that target the new PRR signaling originally absent from the host (Lacombe et al., 2010), making PRR genetic engineering a promising tool in agricultural biotechnology. Similarly, N. benthamiana plants lacking ReMAX, the PRR for perception of the MAMP eMAX respond to eMAX treatment when a chimeric receptor engineered from ReMAX and the tomato Eix2 is transiently expressed (Jehle et al., 2013). It would be interesting to test whether stable transformation of N. benthamiana with ReMAX could confer resistance to a wide range of Xanthomonas bacteria. Xanthomonas bacteria are indeed known to cause serious diseases in major crops, and effective strategies are required to control such diseases (Ryan et al., 2011). Bacterial blight of rice, caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) is one of the most devastating disease in rice (Nino-Liu et al., 2006). Transfer of the potential PRR XA21 (Song et al., 1995) from wild rice Oryza longistaminata to the susceptible rice cultivar (Oryza sativa subsp. japonica var. Taipei 309) confers resistance to multiple isolates of Xoo (Wang et al., 1996), suggesting that XA21 can be used as a tool to control rice blight. Similarly, Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum (Xcm) causes banana Xanthomonas wilt (BXW) and has a huge impact on banana yield (Tripathi et al., 2009). Comparative genomic analysis between Xoo and Xcm revealed a conserved set of bacterial genes required for the activation of XA21-mediated immunity, suggesting that XA21 can be used for engineering resistance against Xcm (Tripathi et al., 2014). This hypothesis was confirmed by the evaluation of transgenic banana plants expressing Xa21 for BXW resistance (Tripathi et al., 2014). After inoculation of Xcm, non-transgenic banana plants display typical BXW symptoms such as yellow ooze in pseudostem, spreading of Xcm, and complete wilting, whereas transgenic banana plants expressing Xa21 show only few or no symptoms, indicating enhanced resistance (Tripathi et al., 2014). Like in tomato plants expressing EFR, growth is not altered in banana plants expressing Xa21 (Tripathi et al., 2014). Interestingly, transfer of XA21 to dicot plants such as sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) or tomato also confers resistance against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri and Ralstonia solanacearum, respectively (Mendes et al., 2010; Afroz et al., 2011). XA21 thus stands as a promising candidate for engineering resistance against diverse pathogens in different plant species.

BOOSTING THE PTI RESPONSE

LecRKs belong to a class of receptor kinases characterized by an extracellular lectin domain, and are involved in plant development and stress responses (Bouwmeester and Govers, 2009; Vaid et al., 2012; Singh and Zimmerli, 2013). Although the lectin motif is suggested to bind to oligosaccharides or small hydrophobic ligands (Barre et al., 2002; Andre et al., 2005; Bouwmeester and Govers, 2009), a recent study showed that Arabidopsis LecRK-I.9/DONR1 acts as a PRR for the DAMP eATP (Cao et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2014). In mammalian cells, abnormal or uncontrolled increase of eATP represents a danger signal from damaged or stressed cells, and is involved in activating the innate immune system (Hanley et al., 2004). Similarly, plant eATP is increased upon various stresses and is proposed to play a central role in regulating plant immunity (Tanaka et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2014; Choi et al., 2014). Importantly, Arabidopsis lecrk-I.9/dorn1 displays impaired ATP-triggered PTI responses, such as Ca2+ influx, activation of MAPK, and up-regulation of stress-induced genes (Choi et al., 2014). LecRK-I.9/DONR1 was initially identified as a target of the Phytophthora infestans RXLR-dEER effector IPI-O (Gouget et al., 2006). LecRK-I.9/DONR1 also contributes to Arabidopsis resistance against Phytophthora brassicae, and is important for maintaining cell wall (CW)-plasma membrane (PM) continuum (Bouwmeester et al., 2011a). Ectopic expression of LecRK-I.9/DONR1 in Solanaceous potato and N. benthamiana plants results in enhanced resistance against Phytophthora infestans (Bouwmeester et al., 2014). The CW-PM continuum is hypothesized to be critical for guarding pathogen invasion, and virulent pathogens destabilize through effector action the CW-PM continuum to facilitate colonization (Bouwmeester et al., 2011a,b). The enhanced resistance observed in transgenic potato and N. benthamiana may thus be the result of a strengthening of CW-PM adhesions by ectopic expression of LecRK-I.9/DONR1 (Bouwmeester et al., 2011a,b, 2014). Alternatively, heterologous expression of LecRK-I.9/DONR1 may trigger an enhanced PTI response via perception of eATP released from pathogen-stressed cells (Choi et al., 2014). When grown in greenhouse condition, stable transgenic potato lines expressing LecRK-I.9/DONR1 display aberrant plant development including wrinkled leaves, decreased leaflet separation, and malformed tuber (Bouwmeester et al., 2014). The strengthening of CW-PM adhesion by heterologous expression of LecRK-I.9/DONR1 may disrupt normal plant development (Bouwmeester et al., 2014).

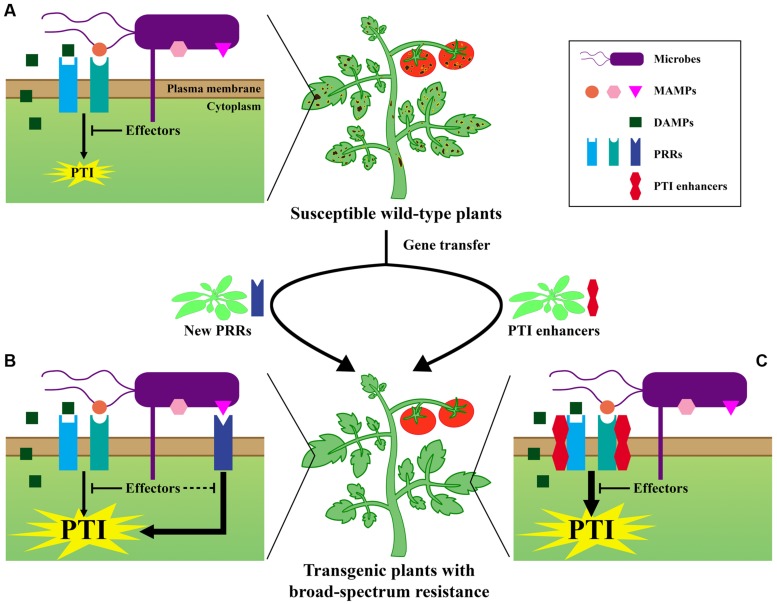

Arabidopsis LecRK-VI.2 was first identified as being involved in ABA inhibition of seed germination (Xin et al., 2009), and was later shown to be a component of the FLS2 complex positively regulating PTI (Singh et al., 2012a; Huang et al., 2014a). Arabidopsis plants over-expressing LecRK-VI.2 demonstrate a constitutively activated PTI, and display significant resistance against hemi-biotrophic Pst DC3000 and necrotrophic Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp. carotovorum (Pcc) SCC1 bacteria (Singh et al., 2012a). Arabidopsis plants over-expressing LecRK-VI.2 demonstrate a dwarf phenotype (Singh et al., 2012a), as already observed in plants with constituve defense responses (Bowling et al., 1994; Li et al., 2001). LecRK-VI.2-mediated resistance in the Brassicaceae plant Arabidopsis can be extended to the Solanaceous family, as heterologous expression of Arabidopsis LecRK-VI.2 in N. benthamiana enhances wild tobacco resistance against two strains of hemi-biotrophic Pseudomonas bacteria and to necrotrophic Pcc SCC1 bacteria (Huang et al., 2014a). Remarkably, even 2 weeks after inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci 11528, N. benthamiana plants expressing LecRK-VI.2 harbor only weak disease symptoms and normal development of flowers, whereas wild-type (WT) and empty Vector control plants are extremely stunted, and display severe necrotic symptoms with no flowering (Huang et al., 2014a). In line with what is observed in Arabidopsis (Singh et al., 2012b), LecRK-VI.2 protective effect in N. benthamiana is bacteria specific (Huang et al., 2014a). However, heterologous expression of LecRK-VI.2 in N. benthamiana does not directly activate, but only potentiates flg22-induced PTI responses. Priming of PTI may explain the observed enhanced resistance in transgenic N. benthamiana plants (Conrath et al., 2006; Conrath, 2011; Huang et al., 2014a). These emerging examples of heterologous expression of PRRs or of modulators of PRRs that can confer broad-spectrum resistance through a potentiated PTI response represent an interesting proof of concept approach that suggest feasibility for future applications to engineer resistant crops through primed PTI (Figure 1; Lacombe et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2014a). Similarly to transgenic expression of EFR (Lacombe et al., 2010), N. benthamiana plants expressing Arabidopsis LecRK-VI.2 demonstrate a WT growth pattern under laboratory conditions (Huang et al., 2014a). The WT-like growth phenotype in N. benthamiana as opposed to the stunted phenotype observed in Arabidopsis may result from partial conservation of downstream PTI signaling in N. benthamiana (Huang et al., 2014a).

FIGURE 1.

Pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) mediated strategies to deploy broad-spectrum pathogen resistance in crops: a conceptual representation. (A) Perception of MAMPs and/or DAMPs by PRRs activates the PTI response. Adapted, virulent pathogens deliver effectors to suppress PTI, rendering wild-type plants susceptible to infection. (B) Interfamily or interspecies transfer of foreign PRRs improves MAMPs recognition and further enhances PTI. Host co-evolved pathogens are unlikely to possess effectors targeting PRRs from other plant species. (C) Heterologous expression of PTI enhancers/positive regulators boosts PTI signaling. Effectors may thus not be sufficient anymore to efficiently repress PTI.

In Arabidopsis, LecRK-VI.2 is crucial for the up-regulation of PTI marker genes responsive to numerous bacterial MAMPs such as flg22, elf18, PGN, and lipopolysaccharide (Singh et al., 2012a), that are recognized by different PRRs (Gómez-Gómez and Boller, 2000; Zipfel et al., 2006; Willmann et al., 2011). In addition to associate with the PRR FLS2 (Huang et al., 2014a), LecRK-VI.2 may thus prime the PTI response through association and positive action at additional, different PRR complexes. Therefore, heterologous expression of LecRK-VI.2 is likely to confer broad-spectrum resistance in other plant species via targeting of multiple PRRs. Therefore, Arabidopsis LecRK-VI.2 or LecRK-VI.2 orthologs and possibly other LecRKs stand as promising candidates in the development of crops with durable, wide-range resistance.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVES

Unlike R protein-mediated resistance that possesses narrow specificity, PTI is broad-spectrum and thus stands as a potential tool for engineering crops with enhanced immunity. Notably, interfamily transfer of genes encoding PRRs or key regulators of PTI enhances resistance of the recipient plant species against a broad range of virulent pathogens (Figure 1; Lacombe et al., 2010; Bouwmeester et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2014a; Tripathi et al., 2014). However, in some cases, such heterologous expression may lead to undesirable changes in growth and development (Bouwmeester et al., 2014). The emerging examples of interfamily transfer of PTI-related gene to confer broad-spectrum resistance is encouraging for the future development of resistant crops, but the durability and efficacy of this approach in the field is yet to be determined. In natural conditions, pathogens are constantly evolving to cope with host immunity (McDonald and Linde, 2002), and some pathogens acquire modified MAMPs to avoid recognition (Felix et al., 1999; Kunze et al., 2004; Lacombe et al., 2010). To achieve durable disease resistance, genetic-engineering should be used wisely, perhaps through stacking multiple PTI- and ETI-related genes, and proper field management should be deployed. The use of novel fundamental discoveries in PTI will definitively help the burgeoning of novel practical approaches to increase crop resistance to deleterious pathogens.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Catinot for critical reading. This work was supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan grants 99-2628-B-002-053-MY3 and 102-2628-B-002-011-MY3 to Laurent Zimmerli.

REFERENCES

- Afroz A., Chaudhry Z., Rashid U., Ali G. M., Nazir F., Iqbal J., et al. (2011). Enhanced resistance against bacterial wilt in transgenic tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) lines expressing the Xa21 gene. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. 104 227–237 10.1007/s11240-010-9825-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andre S., Siebert H. C., Nishiguchi M., Tazaki K., Gabius H. J. (2005). Evidence for lectin activity of a plant receptor-like protein kinase by application of neoglycoproteins and bioinformatic algorithms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1725 222–232 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayliffe M., Singh R., Lagudah E. (2008). Durable resistance to wheat stem rust needed. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11 187–192 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barre A., Herve C., Lescure B., Rouge P. (2002). Lectin receptor kinases in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 21 379–399 10.1080/0735-260291044287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bent A. F., Mackey D. (2007). Elicitors, effectors, and R genes: the new paradigm and a lifetime supply of questions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 45 399–436 10.1146/annurev.phyto.45.062806.094427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm H., Albert I., Fan L., Reinhard A., Nurnberger T. (2014). Immune receptor complexes at the plant cell surface. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 20 47–54 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller T., Felix G. (2009). A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60 379–406 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester K., De Sain M., Weide R., Gouget A., Klamer S., Canut H., et al. (2011a). The lectin receptor kinase LecRK-I.9 Is a Novel Phytophthora resistance component and a potential host target for a RXLR effector. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1001327 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester K., Meijer H. J. G., Govers F. (2011b). At the frontier; effectors crossing the Phytophthora-host interface. Front. Plant Sci. 2:75 10.3389/fpls.2011.00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester K., Govers F. (2009). Arabidopsis L-type lectin receptor kinases: phylogeny, classification, and expression profiles. J. Exp. Bot. 60 4383–4396 10.1093/jxb/erp277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester K., Han M., Blanco-Portales R., Song W., Weide R., Guo L.-Y., et al. (2014). The Arabidopsis lectin receptor kinase LecRK-I.9 enhances resistance to Phytophthora infestans in Solanaceous plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12 10–16 10.1111/pbi.12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling S. A., Guo A., Cao H., Gordon A. S., Klessig D. F., Dong X. I. (1994). A mutation in Arabidopsis that leads to constitutive expression of systemic acquired-resistance. Plant Cell 6 1845–1857 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce T. J. (2012). GM as a route for delivery of sustainable crop protection. J. Exp. Bot. 63 537–541 10.1093/jxb/err281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutus A., Sicilia F., Macone A., Cervone F., De Lorenzo G. (2010). A domain swap approach reveals a role of the plant wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) as a receptor of oligogalacturonides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 9452–9457 10.1073/pnas.1000675107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Tanaka K., Nguyen C. T., Stacey G. (2014). Extracellular ATP is a central signaling molecule in plant stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 20 82–87 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla D., Zipfel C., Robatzek S., Kemmerling B., Nurnberger T., Jones J. D., et al. (2007). A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature 448 497–500 10.1038/nature05999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm S. T., Coaker G., Day B., Staskawicz B. J. (2006). Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 124 803–814 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J., Tanaka K., Cao Y., Qi Y., Qiu J., Liang Y., et al. (2014). Identification of a plant receptor for extracellular ATP. Science 343 290–294 10.1126/science.343.6168.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U. (2011). Molecular aspects of defence priming. Trends Plant Sci. 16 524–531 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U., Beckers G. J. M., Flors V., García-Agustín P., Jakab G., Mauch F., et al. (2006). Priming: getting ready for battle. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19 1062–1071 10.1094/MPMI-19-1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl J. L., Horvath D. M., Staskawicz B. J. (2013). Pivoting the plant immune system from dissection to deployment. Science 341 746–751 10.1126/science.1236011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge R., Van Esse H. P., Maruthachalam K., Bolton M. D., Santhanam P., Saber M. K., et al. (2012). Tomato immune receptor Ve1 recognizes effector of multiple fungal pathogens uncovered by genome and RNA sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 5110–5115 10.1073/pnas.1119623109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desclos-Theveniau M., Arnaud D., Huang T.-Y., Lin G. J.-C., Chen W.-Y., Lin Y.-C., et al. (2012). The Arabidopsis lectin receptor kinase LecRK-V.5 represses stomatal immunity induced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002513 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P. N., Rathjen J. P. (2010). Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11 539–548 10.1038/nrg2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou D., Zhou J. M. (2012). Phytopathogen effectors subverting host immunity: different foes, similar battleground. Cell Host Microbe 12 484–495 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbs G., Silipo A., Aslam S., De Castro C., Liparoti V., Flagiello A., et al. (2008). Peptidoglycan and muropeptides from pathogens Agrobacterium and Xanthomonas elicit plant innate immunity: structure and activity. Chem. Biol. 15 438–448 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix G., Duran J. D., Volko S., Boller T. (1999). Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. Plant J. 18 265–276 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann W., Dahlbeck D., Chesnokova O., Minsavage G. V., Jones J. B., Staskawicz B. J. (2000). Molecular evolution of virulence in natural field strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J. Bacteriol. 182 7053–7059 10.1128/JB.182.24.7053-7059.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Gómez L., Boller T. (2000). FLS2: an LRR receptor–like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 5 1003–1011 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80265-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouget A., Senchou V., Govers F., Sanson A., Barre A., Rouge P., et al. (2006). Lectin receptor kinases participate in protein-protein interactions to mediate plasma membrane-cell wall adhesions in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 140 81–90 10.1104/pp.105.066464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust A. A., Biswas R., Lenz H. D., Rauhut T., Ranf S., Kemmerling B., et al. (2007). Bacteria-derived peptidoglycans constitute pathogen-associated molecular patterns triggering innate immunity in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 282 32338–32348 10.1074/jbc.M704886200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley P. J., Musset B., Renigunta V., Limberg S. H., Dalpke A. H., Sus R., et al. (2004). Extracellular ATP induces oscillations of intracellular Ca2+ and membrane potential and promotes transcription of IL-6 in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 9479–9484 10.1073/pnas.0400733101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heese A., Hann D. R., Gimenez-Ibanez S., Jones A. M. E., He K., Li J., et al. (2007). The receptor-like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 12217–12222 10.1073/pnas.0705306104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. Y., Yeh Y. H., Liu A. C., Cheng C. P., Zimmerli L. (2014a). The Arabidopsis LecRK-VI.2 associates with the pattern-recognition receptor FLS2 and primes Nicotiana benthamiana pattern-triggered immunity. Plant J. 79 243–255 10.1111/tpj.12557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Si W., Deng Q., Li P., Yang S. (2014b). Rapid evolution of avirulence genes in rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. BMC Genet. 15:45 10.1186/1471-2156-15-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffaker A., Pearce G., Ryan C. A. (2006). An endogenous peptide signal in Arabidopsis activates components of the innate immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 10098–10103 10.1073/pnas.0603727103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jehle A. K., Lipschis M., Albert M., Fallahzadeh-Mamaghani V., Furst U., Mueller K., et al. (2013). The receptor-like protein ReMAX of Arabidopsis detects the microbe-associated molecular pattern eMax from Xanthomonas. Plant Cell 25 2330–2340 10.1105/tpc.113.110833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. D. G., Dangl J. L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444 323–329 10.1038/nature05286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol E., Mentzel T., Chinchilla D., Boller T., Felix G., Kemmerling B., et al. (2010). Perception of the Arabidopsis danger signal peptide 1 involves the pattern recognition receptor AtPEPR1 and its close homologue AtPEPR2. J. Biol. Chem. 285 13471–13479 10.1074/jbc.M109.097394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze G., Zipfel C., Robatzek S., Niehaus K., Boller T., Felix G. (2004). The N terminus of bacterial elongation factor Tu elicits innate immunity in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell 16 3496–3507 10.1105/tpc.104.026765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe S., Rougon-Cardoso A., Sherwood E., Peeters N., Dahlbeck D., Van Esse H. P., et al. (2010). Interfamily transfer of a plant pattern-recognition receptor confers broad-spectrum bacterial resistance. Nat. Biotech. 28 365–369 10.1038/nbt.1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathe W. C., III., Bork P. (2001). Evolution of tuf genes: ancient duplication, differential loss and gene conversion. FEBS Lett. 502 113–116 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02639-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Clarke J. D., Zhang Y., Dong X. (2001). Activation of an EDS1-mediated R-gene pathway in the snc1 mutant leads to constitutive, NPR1-independent pathogen resistance. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 14 1131–1139 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.10.1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Wu Y., Yang F., Zhang Y., Chen S., Xie Q., et al. (2013). BIK1 interacts with PEPRs to mediate ethylene-induced immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 6205–6210 10.1073/pnas.1215543110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D., Wu S., Gao X., Zhang Y., Shan L., He P. (2010). A receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase, BIK1, associates with a flagellin receptor complex to initiate plant innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 496–501 10.1073/pnas.0909705107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Walker R. K., Zhao Y., Berkowitz G. A. (2012). Linking ligand perception by PEPR pattern recognition receptors to cytosolic Ca2+ elevation and downstream immune signaling in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 19852–19857 10.1073/pnas.1205448109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho A. P., Zipfel C. (2014). Plant PRRs and the activation of innate immune signaling. Mol. Cell 54 263–272 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B. A., Linde C. (2002). The population genetics of plant pathogens and breeding strategies for durable resistance. Euphytica 124 163–180 10.1023/A:1015678432355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes B. M. J., Cardoso S. C., Boscariol-Camargo R. L., Cruz R. B., Mourao F. A. A., Bergamin A. (2010). Reduction in susceptibility to Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri in transgenic Citrus sinensis expressing the rice Xa21 gene. Plant Pathol. 59 68–75 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2009.02148.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Zhang S. (2013). MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51 245–266 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miya A., Albert P., Shinya T., Desaki Y., Ichimura K., Shirasu K., et al. (2007). CERK1, a LysM receptor kinase, is essential for chitin elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 19613–19618 10.1073/pnas.0705147104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M. A., Sundelin T., Nielsen J. T., Erbs G. (2013). MAMP (microbe-associated molecular pattern) triggered immunity in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 4:139 10.3389/fpls.2013.00139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nino-Liu D. O., Ronald P. C., Bogdanove A. J. (2006). Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars: model pathogens of a model crop. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7 303–324 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00344.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger T., Brunner F., Kemmerling B., Piater L. (2004). Innate immunity in plants and animals: striking similarities and obvious differences. Immunol. Rev. 198 249–266 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M. C., Petersen M., Mundy J. (2010). Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61 621–649 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron M., Avni A. (2004). The receptor for the fungal elicitor ethylene-inducing xylanase is a member of a resistance-like gene family in tomato. Plant Cell 16 1604–1615 10.1105/tpc.022475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A., Yamada K., Hiruma K., Yamashita-Yamada M., Lu X., Takano Y., et al. (2014). The Arabidopsis PEPR pathway couples local and systemic plant immunity. EMBO J. 33 62–75 10.1002/embj.201284303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R. P., Vorholter F. J., Potnis N., Jones J. B., Van Sluys M. A., Bogdanove A. J., et al. (2011). Pathogenomics of Xanthomonas: understanding bacterium-plant interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9 344–355 10.1038/nrmicro2558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Kuo Y. C., Mishra S., Tsai C. H., Chien C. C., Chen C. W., et al. (2012a). The lectin receptor kinase-VI.2 is required for priming and positively regulates Arabidopsis pattern-triggered immunity. Plant Cell 24 1256–1270 10.1105/tpc.112.095778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Chien C.-C., Mishra S., Tsai C.-H., Zimmerli L. (2012b). The Arabidopsis LECTIN RECEPTOR KINASE-VI.2 is a functional protein kinase and is dispensable for basal resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Signal. Behav. 8:e22611 10.4161/psb.22611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Zimmerli L. (2013). Lectin receptor kinases in plant innate immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 4:124 10.3389/fpls.2013.00124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W.-Y., Wang G.-L., Chen L.-L., Kim H.-S., Pi L.-Y., Holsten T., et al. (1995). A receptor kinase-like protein encoded by the rice disease resistance gene, Xa21. Science 270 1804–1806 10.1126/science.270.5243.1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Li L., Macho A. P., Han Z., Hu Z., Zipfel C., et al. (2013). Structural basis for flg22-induced activation of the Arabidopsis FLS2-BAK1 immune complex. Science 342 624–628 10.1126/science.1243825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Gilroy S., Jones A. M., Stacey G. (2010). Extracellular ATP signaling in plants. Trends Cell Biol. 20 601–608 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena G., Boudsocq M., Sheen J. (2011). Protein kinase signaling networks in plant innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14 519–529 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma B. P., Nurnberger T., Joosten M. H. (2011). Of PAMPs and effectors: the blurred PTI-ETI dichotomy. Plant Cell 23 4–15 10.1105/tpc.110.082602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M. A. (2010). ROS in biotic interactions. Physiol. Plant 138 414–429 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi J. N., Lorenzen J., Bahar O., Ronald P., Tripathi L. (2014). Transgenic expression of the rice Xa21 pattern-recognition receptor in banana (Musa sp.) confers resistance to Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12 663–673 10.1111/pbi.12170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi L., Mwangi M., Abele S., Aritua V., Tushemereirwe W. K., Bandyopadhyay R. (2009). Xanthomonas wilt: a threat to banana production in East and Central Africa. Plant Dis. 93 440–451 10.1094/PDIS-93-5-0440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K., Katagiri F. (2010). Comparing signaling mechanisms engaged in pattern-triggered and effector-triggered immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13 459–465 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaid N., Pandey P. K., Tuteja N. (2012). Genome-wide analysis of lectin receptor-like kinase family from Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 80 365–388 10.1007/s11103-012-9952-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J., Zhang X. C., Neece D., Ramonell K. M., Clough S., Kim S. Y., et al. (2008). A LysM receptor-like kinase plays a critical role in chitin signaling and fungal resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20 471–481 10.1105/tpc.107.056754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. L., Song W. Y., Ruan D. L., Sideris S., Ronald P. C. (1996). The cloned gene, Xa21, confers resistance to multiple Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae isolates in transgenic plants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 9 850–855 10.1094/MPMI-9-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmann R., Lajunen H. M., Erbs G., Newman M. A., Kolb D., Tsuda K., et al. (2011). Arabidopsis lysin-motif proteins LYM1 LYM3 CERK1 mediate bacterial peptidoglycan sensing and immunity to bacterial infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 19824–19829 10.1073/pnas.1112862108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff B. B. H., Horvath D. M., Ward E. R. (2011). Improving immunity in crops: new tactics in an old game. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14 468–476 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Z., Wang A., Yang G., Gao P., Zheng Z.-L. (2009). The Arabidopsis A4 subfamily of lectin receptor kinases negatively regulates abscisic acid response in seed germination. Plant Physiol. 149 434–444 10.1104/pp.108.130583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Huffaker A., Bryan A. C., Tax F. E., Ryan C. A. (2010). PEPR2 is a second receptor for the Pep1 and Pep2 peptides and contributes to defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22 508–522 10.1105/tpc.109.068874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Pearce G., Ryan C. A. (2006). The cell surface leucine-rich repeat receptor for AtPep1, an endogenous peptide elicitor in Arabidopsis, is functional in transgenic tobacco cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 10104–10109 10.1073/pnas.0603729103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Li W., Xiang T. T., Liu Z. X., Laluk K., Ding X. J., et al. (2010). Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases integrate signaling from multiple plant immune receptors and are targeted by a Pseudomonas syringae effector. Cell Host Microbe 7 290–301 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou E., Jia Y., Singh P., Correll J. C., Lee F. N. (2007). Instability of the Magnaporthe oryzae avirulence gene AVR-Pita alters virulence. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44 1024–1034 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C. (2014). Plant pattern-recognition receptors. Trends Immunol. 35 345–351 10.1016/j.it.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C., Felix G. (2005). Plants and animals: a different taste for microbes? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8 353–360 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C., Kunze G., Chinchilla D., Caniard A., Jones J. D. G., Boller T., et al. (2006). Perception of the bacterial PAMP EF-Tu by the receptor EFR restricts Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Cell 125 749–760 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C., Robatzek S. (2010). Pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered immunity: veni, vidi…? Plant Physiol. 154 551–554 10.1104/pp.110.161547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C., Robatzek S., Navarro L., Oakeley E. J., Jones J. D. G., Felix G., et al. (2004). Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature 428 764–767 10.1038/nature02485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]