Abstract

Here, we constructed stable, chromosomal, constitutively expressed, green and red fluorescent protein (GFP and RFP) as reporters in the select agents, Bacillus anthracis, Yersinia pestis, Burkholderia mallei, and Burkholderia pseudomallei. Using bioinformatic approaches and other experimental analyses, we identified P0253 and P1 as potent promoters that drive the optimal expression of fluorescent reporters in single copy in B. anthracis and Burkholderia spp. as well as their surrogate strains, respectively. In comparison, Y. pestis and its surrogate strain need two chromosomal copies of cysZK promoter (P2cysZK) for optimal fluorescence. The P0253-, P2cysZK-, and P1-driven GFP and RFP fusions were first cloned into the vectors pRP1028, pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T-Km, pmini-Tn7-gat, or their derivatives. The resultant constructs were delivered into the respective surrogates and subsequently into the select agent strains. The chromosomal GFP- and RFP-tagged strains exhibited bright fluorescence at an exposure time of less than 200 msec and displayed the same virulence traits as their wild-type parental strains. The utility of the tagged strains was proven by the macrophage infection assays and lactate dehydrogenase release analysis. Such strains will be extremely useful in high-throughput screens for novel compounds that could either kill these organisms, or interfere with critical virulence processes in these important bioweapon agents and during infection of alveolar macrophages.

Keywords: GFP, RFP, fluorescent tagging, select agents, Bacillus anthracis., Yersinia pestis, Burkholderia mallei, Burkholderia pseudomallei

Introduction

The bacterial pathogens Bacillus anthracis, Yersinia pestis, Burkholderia mallei, and Burkholderia pseudomallei are the etiologic agents of the diseases anthrax, plague, glanders, and melioidosis, respectively. These organisms are listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as high-priority biological agents that pose a risk to national security because they (i) can be easily disseminated or transmitted; (ii) result in high mortality rates and have the potential for major public health impact; (iii) may elicit public panic and social disruption; and (iv) require special action for public health preparedness. Based on how easily they can be spread and the severity of illness they cause, B. anthracis, Y. pestis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei are classified as Tier 1 select agents.

The horrific events of 11 September 2001 and the subsequent anthrax attacks that caused illness and several deaths have demonstrated that the world needs to be prepared for an increasing number of terrorist attacks, which may include the use of potential biological warfare agents. Many U.S. agencies such as APHIS, CDC, NIAID, DTRA, and HHS started an initiative intended to better understand the pathogenic mechanisms of these organisms and to promote public health and safety by providing effective vaccines and new treatment options. Among research tools to achieve these goals, high-throughput screening (HTS) is a valuable assay to discover compounds that have antimicrobial properties using commercially available chemical compound libraries. In addition, intramacrophage survival assays using genome-wide bacterial mutants are critical to unravel the mechanism of pathogenesis of the aforementioned organisms. However, both HTS analysis and large scale of intramacrophage survival measurements require a rapid, accurate, and reproducible reporting system.

Since the gene encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish (Aequorea victoria) was cloned and expressed in both prokaryotic (Escherichia coli) or eukaryotic (Caenorhabditis elegans) cells (Chalfie et al. 1994), fluorescent proteins have been powerful investigative tools in deciphering biological processes and thus have been widely used as marker systems for prokaryotic organisms (Parker and Bermudez 1997; Valdivia and Falkow 1997; Bumann 2001; Poschet et al. 2001). One of important applications of fluorescent proteins was bacterial tagging, which enables tracking of bacteria in complex environments, including cellular infection, especially by intracellular pathogens. To obtain the highest levels of fluorescence, most researchers have employed relatively facile and efficient means to utilize a replicative plasmid-borne fluorescent reporter to label and track the bacteria in vitro or in vivo (e.g., within macrophages). However, the stability and proper maintenance of the reporter plasmids in these bacteria and the antibiotic resistance conferred by the plasmids within the host can become highly problematic because some antibiotics that are approved for use in select agents such as B. anthracis Ames, Y. pestis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei research do not enter human cells. In addition, the restricted use of antibiotic markers in select agents and the inherent antibiotic resistance of these organisms add another level of complexity to the fluorescent tagging of these species. Hence, it is preferable to tag the bacterial cells with a marker gene that is stably integrated into the bacterial chromosome in order to reduce the risk of marker loss or marker transfer to other species. To date, chromosomally GFP- or RFP-tagged Y. pestis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei have been described (Choi et al. 2005; Norris et al. 2010; Bland et al. 2011). However, due to the weakness of promoter driving the expression of GFP and RFP in these respective organisms, they are not suitable for high-throughput analyses, which require less than ∼200 msec exposure time. Thus, the lack of fluorescent B. anthracis, Y. pestis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei appropriate for rapid, large scale, HTS analysis necessitates further improvement.

In this report, we demonstrate the generation of stable, constitutively expressed, chromosomal transcriptional GFP and RFP fusions in each of the four aforementioned strains that allow for evaluation of fluorescence using the statistical minimum of a 200 msec exposure time. Such strains will be extremely valuable reagents for researchers around the world to screen candidate compounds and/or chemical libraries for antibacterial activity in the event of a bioterrorist attack and/or a developing trend toward increased antibiotic resistance in virulent strains.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth media

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table1. All cloning was conducted in E. coli DH5α, DH5α λpir, or EPmax10B (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA.). Escherichia coli was routinely grown at 37°C in Luria–Bertani broth (LB, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA.) or 1× M9 minimal medium plus 20 mmol/L glucose (MG medium). When necessary, diaminopimelate (DAP) was supplemented at a final concentration of 200 μg/mL. All work with the type A virulent strains B. anthracis Ames, Y. pestis CO92, Burkholderia pseudomallei K96243, B. mallei NBL7, and their derivatives were performed in a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) facility using standard BSL-3 practices, procedures, and containment equipment that was approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University of Cincinnati (UC). UC is registered with the USDA and the CDC and Prevention to work with these highly virulent pathogens. The surrogate strains of the aforementioned select agents were B. anthracis Sterne, Yersina pseudotuberculosis (ATCC 11960), and B. thailandensis (ATCC 700388), respectively. Bacillus anthracis sp. and their derivatives were grown aerobically at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA.). Yersina pseudotuberculosis, Y. pestis, and their derivatives were cultured aerobically at 37°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Difco). Burkholderia thailandensis, B. pseudomallei, B. mallei, and their derivatives were grown at 37°C in LB or MG medium. Antibiotics and nonantibiotic antibacterial compounds were added at the following concentrations when required. For E. coli strains: kanamycin, 50 μg/mL; ampicillin, 100 μg/mL; erythromycin, 300 μg/mL; and glyphosate (GS, primary active ingredient of the herbicide Roundup™ containing 50.2% glyphosate, purchased from local hardware store), 0.3%; for B. anthracis: erythromycin, 5 μg/mL; tetracycline, 10 μg/mL; kanamycin, 20 μg/mL; and spectinomycin, 250 μg/mL; for Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis: kanamycin, 20 μg/mL; chloramphenicol, 35 μg/mL; for B. thailandensis: GS, 0.04%; for B. pseudomallei: GS, 0.3%; for B. mallei: GS, 0.2%.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

| Strain | Description (relevant genotype or phenotype) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− Φ80dlacZΔM15 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 | Invitrogen |

| DH5α λpir | λpir lysogen of DH5α | Laboratory strain |

| S17-1 | Pro− Res− Mod+ recA; integrated RP4-Tet::Mu-Kan::Tn7, Mob+ | Simon et al. (1983) |

| S17-1 λpir | λpir lysogen of S17-1 | Laboratory strain |

| SS1827 | Helper strain for conjugation | Stibitz and Carbonetti (1994) |

| GM2163 | dam dcm strain, deficient in adenine and cytosine methylation | Fermentas |

| RHO3 | Kms; SM10(λpir) Δasd::FRT ΔaphA::FRT | Lopez et al. (2009) |

| EPMax10B-lacIq/pir/leu+ (E1889) | F−λ− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlaX74 deoR endA1 recA1galU galK rpsL nupG 9 lacIq-FRT8 pir-FRT4 | Norris et al. (2009) |

| EPMax10B-pir116Δasd/Δtrp::Gmr/mob-Km+ (E1354) | Gmr Kmr F−λ− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlaX74 deoR endA1 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL nupG Tn-pir116-FRT2Δasd::wFRT Δtrp::Gmr-FRT5 mob [recA::RP4-2 Tc::Mu-Kmr] | Norris et al. (2009) |

| EPMax10B-ΔdapA:: lacIq-pir-Gmr/mob-Km+/leu+ (E2072) | Gmr Kmr F−λ− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlaX74 deoR endA1 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL nupG ΔdapA::pir-lacIq-Gmr-FRT8 mob [recA::RP4-2 Tc::Mu-Kmr] leu+ | Zarzycki-Siek et al. (2013) |

| Bacillus anthracis strains | ||

| Sterne | Surrogate strain, pXO1+/pXO2− | B. E. I. Resources NR-1400 |

| Ames | Virulent type A B. anthracis strain, pXO1+/pXO2+ | B. E. I. Resources NR-411, Little and Knudson (1986) |

| Sterne::Pntr-gfp | Δbla1::pntr-gfp, chromosomal GFP-tagged Sterne | This study |

| Sterne::Pntr-rfp | Δbla1::pntr-rfp, chromosomal RFP-tagged Sterne | This study |

| Sterne::P0253-gfp | Δbla1::p0253-gfp, chromosomal GFP-tagged Sterne | This study |

| Sterne::P0253-rfp | Δbla1::p0253-rfp, chromosomal RFP-tagged Sterne | This study |

| Ames::P0253-gfp | Δbla1::p0253-gfp, chromosomal GFP-tagged Ames | This study |

| Ames::P0253-rfp | Δbla1::p0253-rfp, chromosomal RFP-tagged Ames | This study |

| Burkholderia strains | ||

| B. pseudomallei K96243 | Sequenced prototype virulent strain, clinical isolate | B. E. I. Resources NR-4073, Holden et al. (2004) |

| B. mallei NBL7 | Virulent B. mallei strain China 7, derived from ATCC 23344 | B. E. I. Resources NR-4071 |

| B. thailandensis | Surrogate strain E264, ATCC 700388 | ATCC |

| B. thailandensis::P1-gfp | P1 integron promoter-driven gfp reporter fusion inserted at the chromosomal glmS1 att-Tn7 site of B. thailandensis | This study |

| B. thailandensis::P1-rfp | P1 integron promoter-driven rfp reporter fusion inserted at the chromosomal glmS1 att-Tn7 site of B. thailandensis | This study |

| B. mallei::P1-gfp | P1 integron promoter-driven gfp reporter fusion inserted at the chromosomal glmS1 att-Tn7 site of B. mallei | This study |

| B. mallei::P1-rfp | P1 integron promoter-driven rfp reporter fusion inserted at the chromosomal glmS1 att-Tn7 site of B. mallei | This study |

| B. pseudomallei::P1-gfp | P1 integron promoter-driven gfp reporter fusion inserted at the chromosomal glmS1 att-Tn7 site of B. pseud mallei | This study |

| B. pseudomallei::P1-rfp | P1 integron promoter-driven rfp reporter fusion inserted at the chromosomal glmS1 att-Tn7 site of B. pseudomallei | This study |

| Yersinia strains | This study | |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis | Wild-type strain, ATCC# 11960 (Pfeiffer) | ATCC |

| Y. pestis CO92 | Biovar Orientalis, pMT1+, pCD1+, pPCP1+ | B. E. I. Resources NR-641, (Parkhill et al. 2001) |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis::cysZK-gfp | cysZK-driven gfp reporter fusion integrated into the chromosomal att-Tn7 site of Y. pseudotuberculosis | This study |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis::cysZK-rfp | cysZK-driven rfp reporter fusion integrated into the chromosomal att-Tn7 site of Y. pseudotuberculosis | This study |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis::2cysZK-gfp | Two copies of cysZK-driven gfp reporter fusion integrated into the chromosomal att-Tn7 site of Y. pseudotuberculosis | This study |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis::2cysZK-rfp | Two copies of cysZK-driven rfp reporter fusion integrated into the chromosomal att-Tn7 site of Y. pseudotuberculosis | This study |

| Y. pestis::2cysZK-gfp | Two copies of cysZK-driven gfp reporter fusion integrated into the chromosomal att-Tn7 site of Y. pestis CO92 | This study |

| Y. pestis::2cysZK-rfp | Two copies of cysZK-driven rfp reporter fusion integrated into the chromosomal att-Tn7 site of Y. pestis CO92 | This study |

DNA manipulations

Plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Tables2 and 3, respectively. Genomic DNA isolation, PCR, restriction enzyme digestion, ligation, cloning, and DNA electrophoresis were performed according to standard techniques (Maniatis et al. 1982). All oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by integrated DNA technologies (IDT). PCR was performed using either Choice Taq Mastermix (Denville Scientific, Inc. South Plainfield, NJ, USA) or Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Plasmids were prepared using a QIAprep Spin miniprep kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA.) as recommended by the manufacturer. DNA fragments were purified using either a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) or a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). All cloned inserts were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing performed at the DNA Core Facility of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Plasmids were introduced into E. coli by CaCl2-mediated transformation and into Bacillus sp., Yersinia sp., and Burkholderia sp. by electroporation or conjugation.

Table 2.

Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pBluescript SK+ | High-copy cloning vector; Apr | Invitrogen |

| pBKJ258 | TmS allelic-exchange vector; Emr | Lee et al. (2007) |

| pBKJ223 | I-SceI expression vector; Tcr, Apr | Janes and Stibitz (2006) |

| pRP1028 | TmS allelic-exchange vector; Spr | Dr. Scott Stibitz |

| pRP1028m | turbo-rfp-minus pRP1028; Spr | This study |

| pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T-Km | Apr; Kmr on mini-Tn7T; R6K replicon and oriT | Choi et al. (2005) |

| pTNS2 | Apr; R6K replicon; encodes the TnsABC+D specific transposition pathway | Choi et al. (2005) |

| pTNS3-asdEc | Helper plasmid containing asdEc for Tn7 site-specific transposition system | Kang et al. (2009) |

| pFLP2 | Apr/Cbr; Flp recombinase expression vector | Becher and Schweizer (2000) |

| pBKJΔbla1 | 2 kb flanking sequences of bla1 were cloned between NotI-SacII sites of pBKJ258; Emr | This study |

| pBKJΔbla1::pntr-gfp | Promoter pntr-driven Superfolder gfp cloned into pBKJΔbla1; Emr | This study |

| pBKJΔbla1::p0253-gfp | Promoter p0253-driven Superfolder gfp cloned into pBKJΔbla1; Emr | This study |

| pBKJΔbla1::pntr-rfp | Promoter pntr-driven TurboRed rfp cloned into pBKJΔbla1; Emr | This study |

| pBKJΔbla1::p0253-rfp | Promoter p0253-driven TurboRed rfp cloned into pBKJΔbla1; Emr | This study |

| pRP1028Δbla1::p0253-gfp | Promoter p0253-driven Superfolder GFP cloned into pRP1028; Spr | This study |

| pRP1028m−Δbla1::p0253-rfp | Promoter p0253-driven TurboRed RFP cloned into pRP1028rfp−; Spr | This study |

| pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-gfp | Promoter cysZK-driven gfp reporter fusion cloned between SmaI and ApaI sites of pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T-Km | This study |

| pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-rfp | Promoter cysZK-driven rfp reporter fusion cloned between SmaI and ApaI sites of pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T-Km | This study |

| pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-gfp | Second copy of cysZK-driven gfp reporter fusion cloned between ApaI and KpnI sites of pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-gfp | This study |

| pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-rfp | Second copy of cysZK-driven rfp reporter fusion cloned between ApaI and KpnI sites of pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-rfp | This study |

| pmini-Tn7-gat | mini-Tn7 integration vector based on gat | Norris et al. (2009) |

| pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-gfp | Integron promoter P1-driven egfp reporter fusion cloned between HindIII and EcoRI sites of pmini-Tn7-gat | This study |

| pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-rfp | Integron promoter P1-driven rfp reporter fusion cloned between HindIII and EcoRI sites of pmini-Tn7-gat | This study |

Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Emr, erythromycin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Spr, spectinomycin resistance.

Table 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Restriction site |

|---|---|---|

| Ubla1/Not5′ | AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCATACATGTTCCAGAC | NotI |

| Ubla1/Sm3′ | TCCCCCGGGACTAGGCTTGTAATAC | SmaI |

| Dbla1/Sm5′ | TCCCCCGGGTATCGTTTGGCCACC | SmaI |

| Dbla1/Sac5′ | TCCCCGCGGACCTGTTAACGCTGC | SacII |

| gfp/Pst5′ | AACTGCAGATGCGTAAAGGAGAAGAATTA | PstI |

| gfp/ApaI3′ | GGAATTCGGGCCCTTACTATTTGTATAA | ApaI |

| gfp/Sm3′ | TCCCCCGGGTTACTATTTGTATAATTC | SmaI |

| egfp/Pst5′ | AACTGCAGTGATTAACTTTATAAGGAGGAAAAACATATGAGTAAAGGAGAAG | PstI |

| egfp/Eco3′ | CGGAATTCTTATTTGTATAGTTCATCC | EcoRI |

| Turbo rfp/Pst5′ | AACTGCAGATGAGCGAACTAATAAAG | PstI |

| Turbo rfp/Eco3′ | GGAATTCGTCGACCCGGGCTATTAACGGTGCCCTAATTTG | PstI |

| Turbo rfp/Sm3′ | TCCCCCGGGCTATTAACGGTGCCCTAATTTG | SmaI |

| Burk rfp/Pst5′ | AACTGCAGTGATTAACTTTATAAGGAGGAAAAACATATGAGCGAGCTGATC | PstI |

| Burk rfp/Eco3′ | CGGAATTCTCACCGGTGCCCCAGCTTG | EcoRI |

| Pntr/Sma5′ | TCCCCCGGGGATCTGATCA CTGAGTTGGA | SmaI |

| Pntr/Pst3′ | AACTGCAGCATCATAATTCCCTCCAATTG | PstI |

| P0253/Sma5′ | TCCCCCGGGAAGGTAGTATGATTTGC | SmaI |

| P0253/Pst3′ | AACTGCAGCAAAAATACACCTCCACCGTC | PstI |

| cysZK/Sm5′ | TAACCCGGGAATAAAGTCGATAACTTGCAATTCGG | SmaI |

| cysZK/Pst3′ | AACTGCAGAACTCTATGAAAATGTAGGGAACG | PstI |

| cysZK/Apa5′ | TCCGGGCCCAATAAAGTCGATAACTTGC | ApaI |

| P1/Hind5′ | CCCAAGCTTACTAGTGAACACGAAC | HindIII |

| P1/Pst3′ | AACTGCAGTCGAATCCTTCTTGTGAATC | PstI |

| YPatt5′ | 5′-GCCACATGTCGAAGAAATTATTGC | |

| YPatt3′ | 5′-TTGTAAAAAATTCAGCGTATCAG | |

| PTn7L | 5′-ATTAGCTTACGACGCTACACCC | |

| PTn7R | 5′-CACAGCATAACTGGACTGATTTC | |

| Pla5′ | 5′-ATAACTATTCTGTCCGGGAGTGC | |

| Pla3′ | 5′-TCAGAAGCGATATTGCAGACCC | |

| Ymt5′ | 5′-ATGACTGAAGTACTGCGGAATTCGC | |

| Ymt3′ | 5′-CCAAGCACTCACGAGATCTTGCTGTG | |

| LcrV5′ | 5′-GACGTGTCATCTAGCAGACG | |

| LcrV3′ | 5′-ATGATTAGAGCCTACGAACAAAACCC | |

| BTglmS1 | 5′-GTTCGTCGTCCACTGGGATCA | |

| BTglmS2 | 5′-AGATCGGATGGAATTCGTGGAG | |

| BPglmS1 | 5′-GAGGAGTGGGCGTCGATCAAC | |

| BPglmS2 | 5′-ACACGACGCAAGAGCGGAATC | |

| BPglmS3 | 5′-CGGACAGGTTCGCGCCATGC | |

| BMglmS1 | 5′-ACACGACGCAAAAGCGGAATC | |

| BMglmS2 | 5′-AGTGGGCGTCGATCAACGCG |

Bioinformatic analyses

Several gene expression datasets (Liu et al. 2004; Rodrigues et al. 2006; Sebbane et al. 2006; Bergman et al. 2007; Vadyvaloo et al. 2010) (NCBI GEO database and/or ArrayExpress database) were used, respectively, to identify three groups of B. anthracis, Y. pestis, and B. pseudomallei gene transcripts that exhibited on average throughout the time series, high, medium, and moderately low expression based on RMA (Robust Multi-array Analysis)-normalized Affymetrix probe set intensity levels. Each of these groups was then ranked for those transcripts that had the least variance as a function of time during macrophage infection. Of the transcripts that were identified in each tier, their relative position was used on the genome to identify those that were most likely in the 5′ most position of a potential operon, and the sequence upstream of that was used to test for potential promoter activity that could drive high-, medium-, or low-level GFP expression, respectively (refer to Tables S1–S3).

Macrophage preparation and bacterial infection

The human monocytic cell line, THP-1, was generously provided from William Miller (University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Department of Molecular Genetics, Biochemistry and Microbiology). THP-1 cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium supplemented with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum at 37°C in 5% CO2. Freshly propagated cells were seeded in 384 well plates at a density of 20,000 cells per well and incubated at 37°C to differentiate into macrophages following exposure to 80 nmol/L phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 3 days. Differentiated THP-1 cells were infected with 50 MOI of GFP-tagged B. mallei, B. pseudomallei, Y. pestis, and B. anthracis and phagocytized for 90 min. After infection, cells were washed thrice and treated with RPMI containing gentamicin (50 μg/mL) for Y. pestis and B. anthracis or kanamycin (250 μg/mL) for B. mallei, B. pseudomallei to kill extracellular bacteria. Cells were processed for various analyses including microscopic imaging, bacterial load determination (as CFU), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays at different time points (0, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h).

Infection kinetics

At each time point, cells were harvested and lysed with 0.1% SDS. Differential bacterial load was determined by enumeration of colony forming units (CFU) at different time points.

Cytotoxicity assays

Cytotoxicity was measured based on release of LDH by following CytoTox-ONE homogenous membrane integrity assay kit instruction manual (Promega, Madison, WI). Supernatant from different time points was used to measure cytotoxicity. Fluorescence was measured using an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm following 10 sec of shaking. The results are presented as relative fluorescence units (RFU), which was then calculated as percentage of dead cells as compared to lysed cells.

Image analysis

At each time point, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% para-formaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 30 min. Cell images were captured at different magnifications using GFP (green 485/524 nm excitation/emission) filter and phase contrast (no filter) microscopy. Fluorescence of bacterial colonies on plates was examined with a LEICA Fluorescence Zoom Stereo Microscope. Images were captured at 7× magnification with a color camera.

Results

Objectives

Tag B. anthracis, Y. pestis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei surrogate genomes with constitutively expressed GFP/RFP in vitro and within macrophages to allow high-content analysis and screening of intracellular microbes. Proven constructs success will then allow engineering of their respective virulent select agent strains for commencement of compound and siRNA screens, and will serve as fluorescent background organisms for insertions of specific targetrons.

Identification of constitutive and strong bacterial promoters

With the genetic tools that are available for engineering, the select agents B. anthracis Ames, Y. pestis CO92, B. pseudomallei K96243, B. mallei NBL7, and their respective surrogate strains B. anthracis Sterne, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and B. thailandensis (Choi et al. 2005; Janes and Stibitz 2006; Norris et al. 2009) as well as the ability to construct stable, constitutively expressed, chromosomal fluorescent transcriptional fusions, we first required the identification of constitutive and potent bacterial promoters of the aforementioned strains. We would expect such promoters to (i) drive maximum expression of the fusion reporters, (ii) such expression would not be deleterious to the bacterial host, and (iii) do not affect the genetic stability or virulence of such organism. To achieve this goal, we combined extensive literature searches and bioinformatic analyses for specific promoter identification in each of the aforementioned organisms. The promoter candidates were screened for expression of GFP in E. coli and the surrogate strains first and those with the strongest signal were then tested for activity in the surrogate and select agent strains.

Genomic integrants marked with “Superfolder” green and TurboRed fluorescent proteins

Bacillus anthracis Ames strains (select agent) and B. anthracis Sterne (surrogate)

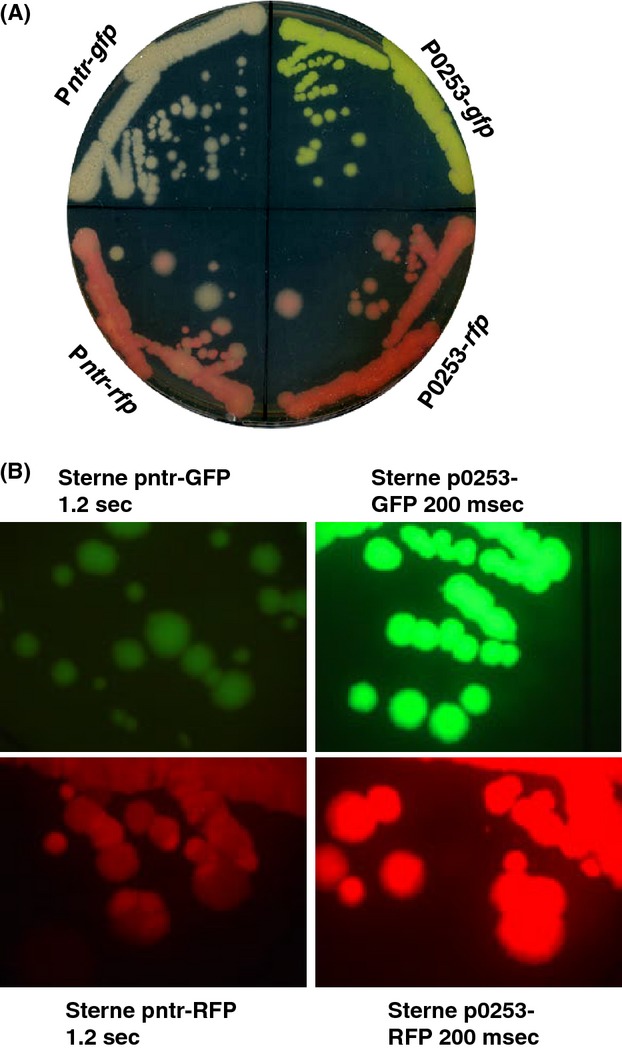

Gat et al. (2003) reported the most potent B. anthracis promoter, Pntr, which was isolated by the use of a promoter trap system via screening of a chromosomal-DNA library of B. anthracis fused to the fluorescent biotracer GFP. The 271-bp Pntr was found to be 500 times more potent than the native pagA promoter and 70 times more potent than the α-amylase promoter (Pamy). Thus, the promoter Pntr was selected for the present study. In addition, Bergman et al. (2007) reported a genome-wide analysis of B. anthracis gene expression during infection of host phagocytes, and used custom B. anthracis microarrays to characterize the expression patterns occurring within intracellular bacteria throughout infection of the phagocytes. Hence, the highly informative microarray data described in the literature were screened using a bioinformatic approach for the top ∼3% of highly expressed genes (Table S1). Of these 11 genes that were invariant across all conditions tested were chosen for further analysis. We cloned Superfolder GFP under the control of promoters of GBAA_0253, GBAA_4533, and GBAA_5722, respectively; the promoter of GBAA 0253 (P0253)-driven GFP revealed bright and consistent fluorescence in host strains and was, therefore, selected for further study (Fig.2 and data not shown).

Figure 2.

(A) Chromosomally tagged Bacillus anthracis Sterne strains were streaked out on a BHI agar plate. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 24 h and recorded by scanning. The bacteria in each quadrant were Sterne::Pntr-gfp (top left), Sterne::Pntr-rfp (bottom left), Sterne::P0253-gfp (top right), and Sterne::P0253-rfp (bottom right). (B) Fluorescence microscopy of bacteria in each quadrant on the same plate described in (A). Fluorescence images were taken with an exposure time of 1.2 sec for the strains Sterne::Pntr-gfp (top left) and Sterne::Pntr-rfp (bottom left), and with an exposure time of 200 msec for the strains Sterne::P0253-gfp (top right) and Sterne::P0253-rfp (bottom right).

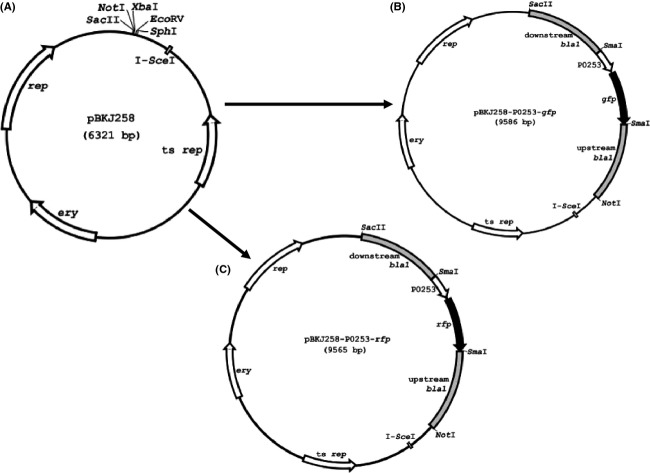

We elected to use the allelic-exchange plasmid, pBKJ258, and helper plasmid, pBKJ223, developed by Janes and Stibitz (2006) and Lee et al. (2007) for chromosomal tagging of B. anthracis with GFP and RFP reporter fusions. The advantage of such a system was that it generated markerless mutations in B. anthracis that facilitated the downstream genetic manipulation with the reporter-tagged strains, especially the select agent B. anthracis Ames, which has very few approved antibiotics as selection markers. To generate a gene replacement construct for integration into the B. anthracis chromosome by homologous recombination, ∼1 kb of upstream and downstream fragments of the bla1 gene (GBAA_2507, encoding β-lactamase) was cloned between the NotI and SacII sites of pBKJ258 (Fig.1A) (Janes and Stibitz 2006), creating pBKJ258Δbla1. The p0253 promoter (or Pntr promoter)-driven Superfolder gfp or TurboRed rfp were then inserted into the unique SmaI site generated at the juncture of flanking sequences of the bla1 gene within pBKJΔbla1. The resulting reporter constructs, pBKJ258-Pntr-gfp, pBKJ258-Pntr-rfp, pBKJ258-P0253-gfp (Fig.1B), and pBKJ258-P0253-rfp (Fig.1C) were confirmed by DNA sequencing. We next introduced the above constructs into B. anthracis Sterne via conjugation or electroporation at room temperature. Plasmid integrants were isolated by a shift to the replication-nonpermissive temperature while maintaining selection for erythromycin resistance. The double crossover, homologous recombination event was achieved by the introduction of a second plasmid, pBKJ223, which was then lost spontaneously following screening by PCR and DNA sequencing for the desired replacement of the bla1 gene with P0253 (or Pntr)-driven gfp or rfp reporter fusions. The allelic-exchange procedure performed here has previously been described in detail (Janes and Stibitz 2006). The chromosomal GFP- and RFP-tagged B. anthracis Sterne strains were streaked out on BHI agar plates and examined by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figure2A, the greenish or reddish colonies of GFP- or RFP-tagged bacteria appeared on BHI agar and could be observed very easily with the naked eye. However, the bacteria tagged with Pntr-gfp or Pntr-rfp emitted weaker fluorescence (Fig.2A, top and bottom left quadrants) than bacteria tagged with P0253-gfp or P0253-rfp (Fig.2A, top and bottom right quadrants). As expected, all bacterial cultures streaked on the same plate were fluorescent using fluorescence microscopy (Fig.2B). Bacillus anthracis Sterne tagged with P0253-gfp or P0253-rfp exhibited a much brighter fluorescent signal, even with an exposure time of 200 msec than bacteria marked with Pntr-gfp or Pntr-rfp with an exposure time of 1.2 sec (Fig.2B), indicating that the P0253 promoter was much stronger than that of Pntr in B. anthracis. Therefore, we selected the P0253 promoter-driven reporters only for tagging the Ames select agent strain.

Figure 1.

(A) Plasmid maps of pBKJ258, (B) pBK258-P0253-gfp, and (C) pBK258-P0253-rfp, respectively.

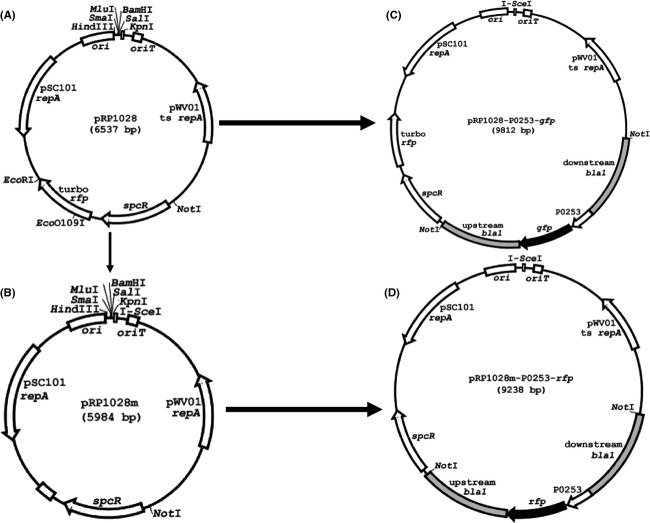

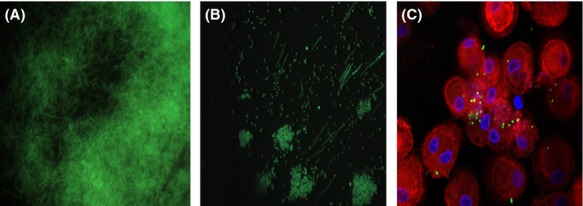

Since the erythromycin resistance marker (ery) in pBKJ258 and the tetracycline resistance marker (tet) in pBKJ223 were not approved for use in the select agent B. anthracis Ames strain, we acquired another gene replacement plasmid, pRP1028 (Fig.3A), and helper plasmid, pSS4332. Plasmids pRP1028 and pSS4332 were used as improvements to the previously published system (Janes and Stibitz 2006), and served the same functions of pBKJ258 and pBKJ223, respectively. Plasmid pRP1028 carries a spectinomycin resistance selectable marker (spcR) and pSS4332 harbors a kanamycin resistance selectable marker (kan), respectively. Both antibiotic resistance markers were appropriate for use in select agent strains. Considering that the presence of an rfp gene in the plasmid backbone of pRP1028 (a feature facilitating a direct visual screen for plasmid loss following introduction of pSS4332 to promote recombination) could interfere with the RFP tagging of the Ames strain, we modified pRP1028 by EcoRI and EcoOI091 digestion to remove 552 bp internal sequence of the turbo rfp gene, thereby creating pRP1028m (Fig.3B). Next, a 3029-bp fragment containing Δbla1::P0253-gfp or -rfp from pBKJ258-P0253-gfp (Fig.1B) and pBKJ258-P0253-rfp (Fig.1C) was PCR amplified and cloned into the unique NotI site of pRP1028 and pRP1028m, respectively. The resultant allelic-exchange reporter constructs, pRP1028-P0253-gfp (Fig.3C) and pRP1028-P0253-rfp (Fig.3D), were verified by DNA sequencing and introduced into the Ames strain. Plasmid integrants were isolated following a temperature shift while maintaining selection for spectinomycin resistance (Janes and Stibitz 2006). Introduction of pSS4332 into the integrant led to I-SceI-mediated cleavage of the integrated plasmid, stimulating the second crossover event. Loss of all engineered plasmids used for chromosomal integration was demonstrated by a concomitant loss of antibiotic resistance. The presence of the virulence plasmids pXO1 and pXO2, and the desired chromosomal replacement of bla1 gene with P0253-gfp or -rfp reporter fusions in the Ames strain was confirmed by PCR and sequencing. The GFP- and RFP-marked Ames strains were finally validated by fluorescence microscopy. Figure4 showed the fluorescence microscopic analyses of vegetative cells (Fig.4A) and spores (Fig.4B) of the GFP-tagged B. anthracis Ames as well as THP-1 macrophages infected with GFP-tagged spores derived from the Ames strain (Fig.4C).

Figure 3.

(A) Plasmid maps of pRP1028, (B) pRP1028m, (C) pRP1028-P0253-gfp, and (D) pRP1028m-P0253-rfp, respectively.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence micrographs of (A) Bacillus anthracis vegetative cells, (B) B. anthracis spores, and (C) B. anthracis spore expressing GFP within monocyte-derived macrophages.

Yersina pestis strains CO92 (select agent) and Yersina pseudotuberculosis (surrogate)

Bland et al. (2011) identified a strong, likely constitutive promoter, PcysZK, in Y. pestis by screening a library of Y. pestis KIM D27 DNA fragments fused to a promoterless DsRed. PcysZK was reported to drive expression of the fluorescent protein in laboratory media or during macrophage infection, permitting detection by confocal laser scanning microscopy in single copy. Therefore, PcysZK was chosen as the primary strong promoter candidate for the Yersinia strains. We also analyzed the whole-genome microarray data of the Y. pestis in vivo transcriptome in infected fleas reported by Vadyvaloo et al. (2010), and categorized Y. pestis promoters into three promoter expression groups: 54 low, 36 medium, and 48 high (Table S2). We chose six promoters (PrplJ(YPO3749), PrelC(YPO3751), PrplN(YPO0220), PnusE(YPO0209), PrpsM(YPO0231), and PrplU(YPO3712)) as a high-expression group along with PcysZK for promoter activity studies.

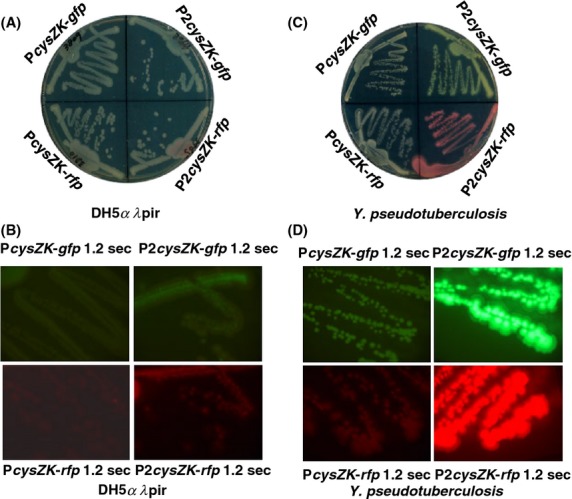

Next, we elected to tag Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis using a Tn7-based, broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system reported by Choi et al. (2005). The system, consisting of a mini-Tn7 vector and a helper plasmid pTNS2 encoding the site-specific TnsABC+D transposition pathway, allows the engineering of diverse genetic traits into bacteria, including Y. pestis, at a single attTn7 site downstream of the glmS gene (Choi et al. 2005). The Yersinia promoters pcysZK, PrplJ, PrelC, PrplN, PnusE, PrpsM, and PrplU were first PCR amplified using genomic DNA of Y. pestis CO92 as the template, restricted with SmaI and PstI, and ligated with Superfolder gfp or TurboRed rfp digested with PstI and ApaI. The reporter fusions were then cloned between SmaI and ApaI sites of the mini-Tn7 vector, pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T-Km (Fig.5A), respectively. The resultant constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing and mobilized into Y. pseudotuberculosis by triparental mating using E. coli conjugation strain RHO3 (Lopez et al. 2009) and helper plasmid pTNS2. Kanamycin-resistant conjugants with chromosomal Tn7 insertions in Y. pseudotuberculosis were verified by PCR analysis using primer pair YPatt5′ and YPatt3′, and primer pair PTn7L and PTn7R. The kanamycin resistance marker was removed by Flp recombinase-mediated excision via plasmid pFLP2, which was then cured by sucrose counterselection. All GFP- and RFP-tagged Y. pseudotuberculosis strains were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Unexpectedly, strains marked with PrplJ-, PrelC-, PrplN-, PnusE-, PrpsM-, or PrplU-driven reporter fusions exhibited very weak fluorescent signals (data not shown) and were therefore not pursued further. Consistent with the previous study (Bland et al. 2011), PcysZK showed strong promoter strength in Yersinia strains. As shown in Figure6, E. coli DH5α λpir harboring mini-Tn7 construct (pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-gfp) or (pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-rfp) grown on LB plates (Fig.6A, top and bottom left quadrants) displayed fluorescent signals using fluorescence microscopy with an exposure time of 1.2 sec (Fig.6B, top and bottom left quadrants). In contrast, the chromosomal PcysZK-gfp- or PcysZK-rfp-tagged Y. pseudotuberculosis strains cultured on LB plates (Fig.6C, top and bottom left quadrants) exhibited brighter fluorescence (Fig.6D, top and bottom left quadrants) than DH5α λpir (pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-gfp) or DH5α λpir (pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-rfp), respectively. Considering the presence of multiple copies of plasmid in E. coli, PcysZK was much more active in Yersinia strains.

Figure 5.

Plasmid maps of (A) pUC18R6KT-mini-Tn7T-Km, (B) pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-gfp, and (C) pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-rfp, respectively.

Figure 6.

(A) Escherichia coli DH5α λpir strains harboring reporter plasmid construct pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-gfp, pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-rfp, pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-gfp, or pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-rfp were struck on LB-agar plates. (B) Colony fluorescence microscopy of bacteria in each quadrant on the same plate described in (A). (C) Chromosomally integrated Yersina pseudotuberculosis strains were also struck out on L-agar plates and colony micrographs demonstrating GFP and RFP fluorescence are shown in (D).

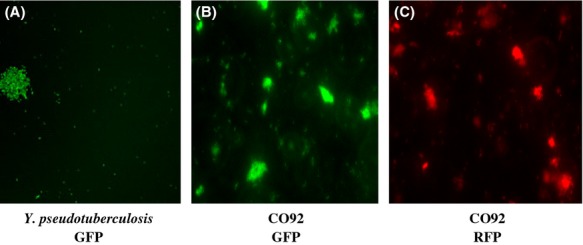

The success of tagging surrogate and fluorescent Y. pseudotuberculosis next led us to the goal of marking the virulent select agent strain, Y. pestis CO92, with PcysZK-gfp and PcysZK-rfp following the identical procedure described above. The tagged CO92 strain fluoresced well originally with an exposure time of 200 msec. Unfortunately, the fluorescent signal of the tagged strain became dimmer in subsequent experiments and thus was deemed inappropriate for HTS analyses. Hence, we elected to enhance fluorescence by tagging Yersinia strains chromosomally with two copies of the fusions. Therefore, a second copy of PcysZK-gfp or PcysZK-rfp was cloned between the ApaI and KpnI sites of pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-gfp or pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-rfp in the same orientation of the first copy of the fusion, creating pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-gfp (Fig.5B) and pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-rfp (Fig.5C), respectively. Following the same steps described above, two copies of reporter fusions 2PcysZK-gfp and 2PcysZK-rfp were successfully inserted at the chromosomal Tn7 site of surrogate strain Y. pseudotuberculosis and the select agent, Y. pestis CO92. The resultant strains were then validated by fluorescence microscopy. The difference between one copy of each reporter construct versus two copies were apparent in terms of the fluorescence signal emitted as demonstrated in Figure6. Escherichia coli DH5α λpir(pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-gfp) or DH5α λpir(pUC18R6KT-2PcysZK-rfp) cultured on an LB plate (Fig.6A, top and bottom right quadrants) emitted brighter fluorescence (Fig.6B, top and bottom right quadrants) than DH5α λpir(pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-gfp) or DH5α λpir(pUC18R6KT-PcysZK-rfp) (Fig.6A and B, top and bottom left quadrants) with the same exposure time. As expected, Y. pseudotuberculosis tagged with 2PcysZK-gfp or 2PcysZK-rfp reporters produced greenish or reddish colonies on LB plates (Fig.6C, top and bottom right quadrants) and yielded a far brighter fluorescence signal (Fig.6D, top and bottom right quadrants) than Y. pseudotuberculosis tagged with one copy of the reporter fusions (Fig.6C and D, top and bottom left quadrants). Bacterial cells of 2PcysZK-gfp- or 2PcysZK-rfp-tagged Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis CO92 from planktonic cultures fluoresced well with an exposure time of 200 msec (Fig.7A–C). In addition, the presence of three important natural virulence plasmids pCP1, pMT1, and pCD1 in the tagged CO92 strains were confirmed by PCR analysis with primer pair Pla5′ and Pla3′ (specific to pla gene in pCP1, encoding the plasminogen activator; McDonough and Falkow 1989), Ymt5′ and Ymt3′ (specific to ymt gene in pMT1, encoding a murine toxin phospholipase D; Rudolph et al. 1999), and LcrV5′ and LcrV3′ (specific to lcrV gene in pCD1, encoding a major protective antigen; Titball and Williamson 2001) (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Fluorescence micrographs of (A) Yersina pseudotuberculosis GFP, (B) Y. pestis CO92 GFP, and (C) Y. pestis CO92 RFP strains with the fusions inserted into the chromosomal Tn7 site.

Burkholderia mallei NBL and pseudomallei strains K96243 (select agent) and B. thailandensis (surrogate)

Yu and Tsang (2006) described the use of the ribosomal rpsL promoter PCS12 from Burkholderia cenocepacia LMG16656 and from B. cepacia MBA4 for efficient expression of a functional transporter protein in E. coli. Norris et al. (2010) utilized the enhanced GFP (eGFP) and other optimized fluorescent protein genes driven by the rpsL promoter PS12 of B. pseudomallei to achieve stable, site-specific fluorescent labeling of B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis. A constitutive broad-host-range P1 integron promoter showed potency to drive the expression of Tn7-site-specific transposase and the lux operon for bioluminescent imaging in Burkholderia spp. (Choi et al. 2008; Massey et al. 2011). Therefore, we selected PS12 and P1 as good promoter candidates for further study. In addition, based on a proteome reference map and protein abundance of B. pseudomallei during the stationary growth phase (Wongtrakoongate et al. 2007), promoters of genes encoding chaperonin GroES, the heat shock protein (GrpE) and phasin-like protein (PhaP), were also considered. Based on microarray data derived from B. pseudomallei K96243 (Rodrigues et al. 2006), our bioinformatic analysis predicted 63 genes that were highly expressed, which were also on the promoter candidate list (Table S3).

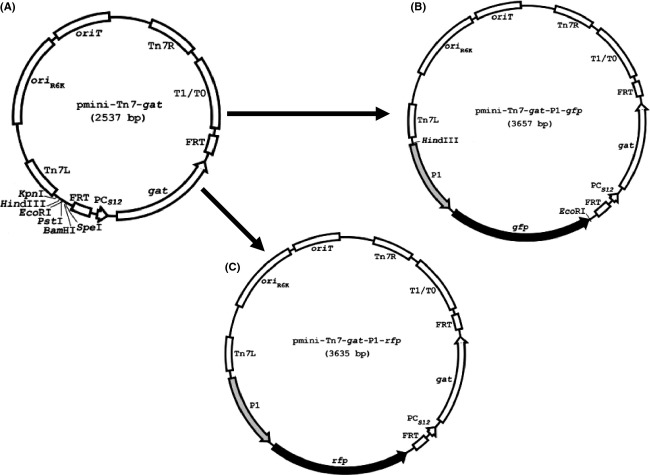

The use of specific selectable antibiotics resistance cassettes in both B. pseudomallei and B. mallei is strictly regulated. Only a few antibiotics, including gentamicin, kanamycin, and zeocin, are currently approved for use in these bacteria, but wild-type strains are highly resistant to these antibiotics (Schweizer and Peacock 2008). Norris et al. (2009) reported glyphosate (the active ingredient in the herbicide, Round-Up™) resistance as a novel select-agent-compliant, nonantibiotic-selectable marker for Burkholderia select-agent species, and developed several mini-Tn7 vectors for stable, site-specific fluorescent tagging of B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis based on the gat gene, which encodes glyphosate acetyltransferase and confers resistance to the common herbicide, glyphosate (Norris et al. 2010). Hence, we elected to use gat as a selectable marker and chose the site-specific transposon pmini-Tn7-gat (Norris et al. 2009, Fig.8A) as the vector to deliver the reporter fusions into the genomes of Burkholderia spp. Since the constructs mini-Tn7-gat-gfp and mini-Tn7-gat-rfp, in which both egfp and optimized rfp were driven by the PS12 promoter, and the relevant E. coli strains for fluorescent labeling of Burkholderia spp. were already available, we tagged B. thailandensis with PS12-gfp and PS12-rfp at the chromosomal attTn7 sites using the above constructs following previously described procedures (Norris et al. 2010). The tagged surrogates fluoresced with an exposure time of 2 sec, but the fluorescent signal was not detectable with an exposure time of 200 msec (data not shown). Thus, the reporter fusions PS12-gfp and PS12-rfp were not suitable for high-throughput screening. Therefore, for further studies to proceed, a search for promoters stronger than PS12 in Burkholderia spp. was required.

Figure 8.

Plasmids maps of (A) pmini-Tn7-gat, (B) pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-gfp, and (C) pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-rfp, respectively.

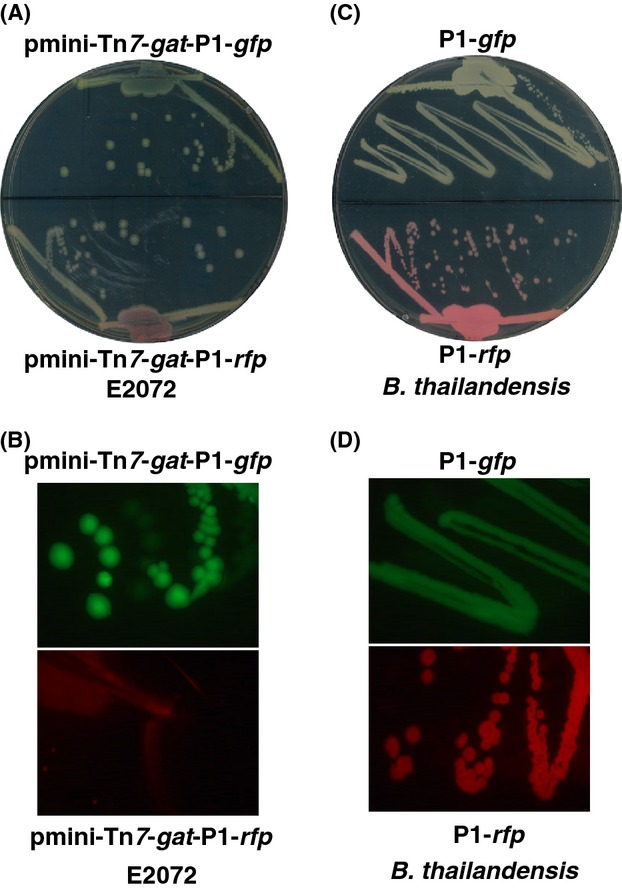

Next, Burkholderia promoters PgroES, PgrpE, and Pphap and the integron promoter P1 were assayed for their strength to drive the expression of each reporter. Specifically, promoters PgroES, PgrpE (GrpE), and Pphap were PCR amplified using genomic DNA of B. pseudomallei as templates. Promoter P1 was amplified by PCR using pTNS3-asdEc as template. The reporters egfp and the optimized rfp for Burkholderia spp. were PCR amplified from mini-Tn7-gat-gfp and mini-Tn7-gat-rfp, respectively. All amplified promoter fragments were digested with HindIII and PstI, and ligated with PstI and EcoRI-restricted egfp and rfp. The promoter-reporter fusions were then cloned between HindIII and EcoRI sites of pmini-Tn7-gat (Fig.8A). The resultant constructs, pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-gfp (Fig.8B), pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-rfp (Fig.8C), and others were confirmed by DNA sequencing and transformed into the E. coli donor strain, E2072. Each fluorescent tag was then introduced into the surrogate strain B. thailandensis by triparental mating using E. coli helper strain E1354 (pTNS3-asdEc) as previously described (Norris et al. 2009). Burkholderia thailandensis containing the inserted transposon was selected on 1× M9 minimal glucose medium containing 0.3% glyphosate. Insertion at the chromosomal glmS1 or glmS2 att-Tn7 sites of B. thailandensis was verified by PCR as previously described (Choi et al. 2008; Kang et al. 2009; Norris et al. 2009), utilizing two primers BTglmS1 and BTglmS2 in combination with primer Tn7L. All tagged strains with insertion at glmS1 att-Tn7 site were then examined by fluorescence microscopy. Burkholderia thailandensis labeled with PgroES-, PgrpE-, Pphap-gfp, or -rfp produced very weak fluorescent signals (data not shown) and thus were not used for the further study. In contrast, the P1 integron promoter demonstrated much stronger promoter activity to drive the expression of fluorescent proteins in both E. coli and B. thailandensis. As shown in Figure9, E. coli E2072 harboring plasmid construct pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-gfp or pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-rfp struck on an LB plate (Fig.9A) displayed fluorescent signal using low-magnification microscopy (Fig.9B). Burkholderia thailandensis labeled with P1-gfp or P1-rfp produced greenish or reddish colonies on an LB plate (Fig.9C), and exhibited a bright fluorescent signal with an exposure time of 200 msec (Fig.9D, 10A and B). As the surrogate strain B. thailandensis was successfully labeled with P1-gfp or P1-rfp, and yielded a high fluorescent signal, we subsequently tagged the select agents B. mallei NBL and B. pseudomallei strain K96243 genomes with P1-gfp or P1-rfp following the same procedure as described above. The genomic DNA of both GFP- and RFP-tagged select agent strains was isolated and PCR analysis using the following primers confirmed the reporter insertion at the chromosomal att-Tn7 sites as previously described (Choi et al. 2006, 2008; Norris et al. 2009). For B. mallei, the two PCR primers BMglmS1 and BMglmS2 were used to determine Tn7 insertion downstream of either glmS1 or glmS2 in combination with primer Tn7L. For B. pseudomallei, insertions at the glmS1, glmS2, and glmS3 att-Tn7 sites were verified utilizing primers BPglmS1, BPglmS2, and BPglmS3 in combination with primer Tn7L. Examination by fluorescence microscopy demonstrated that B. pseudomallei and B. mallei cells tagged with P1-gfp or P1-rfp at the glmS1 att-Tn7 sites generated bright fluorescent signals (Fig.10 B–D and data not shown).

Figure 9.

(A) Escherichia coli E2072 (pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-gfp) (top of plate) and E. coli E2072(pmini-Tn7-gat-P1-rfp) (bottom of plate) struck out on LB-agar plates. (B) Fluorescence microscopy of the E. coli strains described in (A). (C) Chromosomal glmS1 att-Tn7 site-integrated B. thailandensis Tn7-P1-gfp (top of plate) and B. thailandensis Tn7-P1-rfp (bottom of plate) that struck out on LB-agar plates. (D) Fluorescence microscopy of the B. thailandensis strains described in (C).

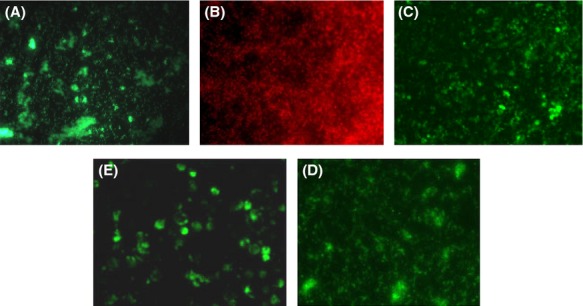

Figure 10.

Fluorescence microscopy of chromosomal glmS1 att-Tn7 site-integrated Burkholderia GFP and RFP fusion strains. (A) Burkholderia thailandensis GFP, (B) B. thailandensis RFP, (C) B. mallei GFP, (D) B. pseudomallei GFP, and (E) B. mallei expressing GFP within THP-1 macrophages.

Bacterial growth and LDH release in macrophages upon infection with GFP-tagged B. anthracis, Y. pestis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei

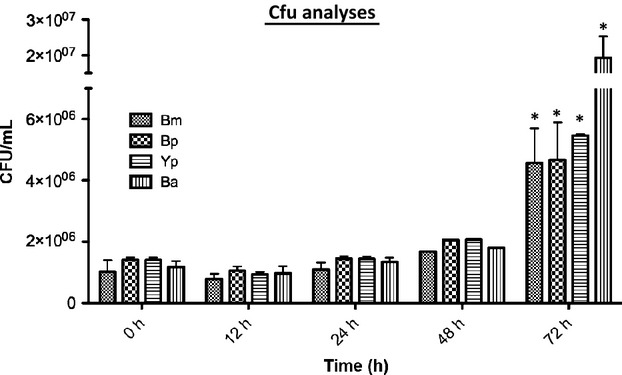

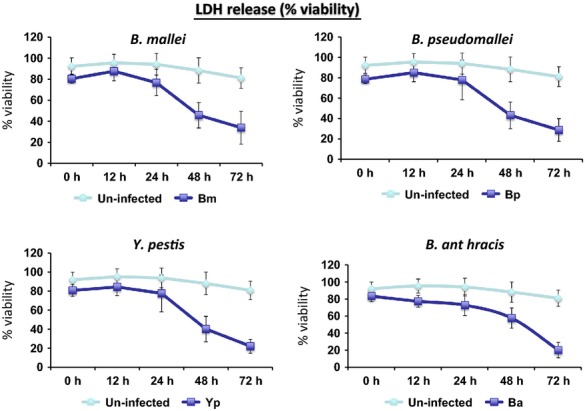

Upon completion of all above fluorescent tagging work on these bacteria, we next used four GFP-tagged select agents, B. anthracis Ames, Y. pestis CO92, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei to infect differentiated human monocytic THP-1 cells and performed image analysis, bacterial load determinations, and LDH assays over time. As shown in Figure1, compared to the initial bacterial load at the zero time point, no increase in CFU counts were observed for all strains within macrophages at 12 and 24 h postinfection. At 48 h postinfection, bacterial density increased only slightly. In contrast, CFU counts of all strains rose dramatically within macrophage at 72 h postinfection with nearly 20 times increase for B. anthracis Ames, 3.5 times for Y. pestis CO92, and 2–3 times for B. pseudomallei and B. mallei, respectively. In parallel, our LDH assays indicated that Y. pestis-, B. mallei-, and B. pseudomallei-infected macrophages retained 80% viability during the first 24 h postinfection, but dropped significantly to approximate 40% at 48 h postinfection. Viability continued to drop by 20% at 72 h postinfection (Fig.2). In contrast, the viability of B. anthracis-infected macrophages dropped continuously at each time point, albeit 20% viability was reached at 72 h postinfection (Fig.2). The above kinetics of bacterial propagation within macrophages and the release of LDH, a biomarker for cellular cytotoxicity and cytolysis, indicated that the engineered GFP tags were useful to track the select agents B. anthracis Ames, Y. pestis CO92, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei, respectively.

Figure 11.

Time course of colony forming unit analysis of GFP-tagged B. anthracis (Ba), Y. pestis (Yp), B. mallei (Bm), and B. pseudomallei (Bp) after phagocytosis by THP-1 macrophages (n = 3). The stars (*) above the bars at the 72 h time point indicate a significance level of P < 0.05.

Figure 12.

LDH release over a period of 3 days from THP-1 macrophages infected with GFP-tagged B. anthracis, Y. pestis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei (infected, dark blue line) versus uninfected (light blue line) (n = 3).

Discussion

In this study, we constructed chromosomal, constitutively expressed GFP and RFP fusions in B. anthracis Ames, Y. pestis, B. mallei, B. pseudomallei, and their surrogates B. anthracis Sterne, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and B. thailandensis, respectively. Considering the potential use of these tagged strains in large-scale high-throughput chemical compound screening, siRNA screening, genome-wide mutant construction and subsequent macrophage survival assays, the fluorescent strains were anticipated to meet the following criteria with regard to the GFP or RFP reporter (i) in cis, chromosomal integration, (ii) stable maintenance, (iii) constitutive expression, (iv) wild-type virulence fitness, and (v) less than 200 msec exposure time required in a high-throughput chemical screening analyses. This last feature (v) is likely the most relevant for future use and was the greatest challenge, since the equipment used for our fluorescent measurements required <200 msec exposure, and none of the reported GFP and RFP reporters at the single-copy level can meet such a short exposure time requirement. Thus, we present here the demonstration of the completion of this challenging genomic tagging work in the aforementioned highly virulent strains and their surrogates. Due to the strict requirements and high expenses for handling the select agents, all reporter fusions were validated in their respective surrogates prior to delivery into the human-virulent, select agent strains. The respective GFP and RFP tagging would facilitate bacterial coinfection or competitive infection assays where two strains/mutants expressing different colors could be located or tracked.

To achieve our goal of obtaining stable, chromosomal, constitutive GFP/RFP reporters in these highly virulent select agents and their surrogates, we first needed to select gfp and rfp reporter genes adapted to use in the aforementioned organisms. The wild-type gfp and rfp have been mutated or optimized based on codon usage preferred by bacteria to improve detection and expression of the fluorescent protein in prokaryotes (Heim et al. 1995; Cormack et al. 1996; Miller and Lindow 1997; Norris et al. 2010). We chose the GFP Superfolder and RFP TurboRed (Su et al. 2013) as fluorescent proteins for B. anthracis, Y. pestis, and Y. pseudotuberculosis, and the eGFP and optimized RFP (Norris et al. 2010) for B. mallei and B. pseudomallei, which have been utilized successfully in fluorescent tagging of Francisella spp. (Su et al. 2013) and Burkholderia spp. (Norris et al. 2010). Second, a bioinformatic approach coupled with exhaustive literature searches were used to predict the strongest, constitutive bacterial promoters suitable for our purposes. Two B. anthracis promoters were selected based on both techniques and preliminary screening. The first, P0253 was rated “hot and invariant” using the bioinformatic search, a rating that was considered the highest possible using the programed algorithm (see Materials and Methods section and Table S1). The second, Pntr, was identified by a promoter trap system to be most potent B. anthracis promoter, 10 times more potent than the very strong Psaplong promoter and 70 times more efficient than Pamy in eliciting GFP expression in B. anthracis (Gat et al. 2003). While both promoters were capable of driving expression of gfp and rfp at the single copy in the surrogate strain B. anthracis Sterne, P0253 exhibited much more stronger promoter strength than Pntr by approximately 30-fold as demonstrated by the fluorescence intensity (Fig.3). Hence, only P0253 was selected for use in B. anthracis Ames, and its fluorescence in the select agent was indistinguishable from that of its surrogate strain. Fortunately, both vegetative cells and spores of B. anthracis were fluorescently tagged (Fig.4), indicating the promoter P0253 was continuously on from vegetative growth phase to the sporulation stages, in all cell forms of the organism. Pntr is a nitroreductase promoter (Gat et al. 2003). P0253 was located at the upstream promoter region of a gene (GBAA_0253) encoding a hypothetical protein comprising of 95 amino acids. The protein could be one of the most abundant proteins in the organism because the promoter P0253 was constitutive and robust, most likely the strongest promoter in B. anthracis so far to the best of our knowledge. It is noteworthy that characterization of function of the gene (GBAA_0253) should be performed for future studies.

Choi et al. (2005) described “GFP tagging” Y. pestis by utilizing a mini-Tn7 construct expressing GFP from the neo promoter (Pneo) followed integration into the Y. pestis A1122 chromosome, and determined the distribution of GFP-expressing bacteria within mouse peritoneal exudate cells. However, the fluorescent signal delivered by such a reporter fusion was too weak to be detectable with an exposure time of 200 msec (data not shown). In agreement with the report by Bland et al. (2011), our study also showed that promoter PcysZK (YPO2992) supported the highest level of fluorescence expression in single copy in Y. pestis. cysZ is a conserved, nonessential gene that encodes an inner membrane sulfate transporter protein (Parra et al. 1983), which would be highly abundant as this is a key nutrient for cells during all phases of growth (Bland et al. 2011). Despite the fact that the promoter PcysZK was not a “hit” in our bioinformatics search, it displayed experimentally much stronger promoter activity to drive the reporter expression than those predicted to be high, including as PrplJ-, PrelC-, PrplN-, PnusE-, PrpsM-, or PrplU. Unexpectedly, we observed fluorescence instability with PcysZK-gfp/rfp-tagged Y. pestis, which fluoresced brighter initially but the fluorescent signal became weaker in the subsequent experiments. We reasoned a mutation might occur in either the promoter or the reporter gene during bacterial propagation after integration of the reporter fusion into the genome, but sequencing analysis ruled out this possibility. Introduction of a second copy of the PcysZK-gfp/rfp reporter fusion into the Yersinia genome not only stabilized the fluorescence but also significantly increased the fluorescence signal (Fig.6).

Norris et al. (2010) constructed and demonstrated the use of several vectors for stable and site-specific fluorescent tagging of B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis. These tools employed the rpsL promoter PS12 to drive the expression of egfp and other optimized fluorescent protein genes (cyan, red, and yellow) to achieve chromosomal labeling of Burkholderia spp. (Norris et al. 2010). However, the fluorescent signal intensity of the above chromosomal fusions PS12-egfp and PS12-rfp in B. thailandensis was not high enough to be detected with an exposure time of 200 msec, neither were the fusions PgroES-, PgrpE-, Pphap-gfp, or -rfp (data not shown). During the screening for other potent promoter candidates, the P1 integron promoter-driven reporter fusions yielded the strongest fluorescence in single copy in the surrogate strain with an exposure time of 200 msec and was further demonstrated in B. pseudomallei and B. mallei (Figs. 9, 10). The relative strength of P1 integron promoter in plasmid R388 and in transposon Tn1696 was first characterized to be six times more efficient in E. coli than the depressed tac promoter (Levesque et al. 1994). The P1 integron promoter was mostly associated with antibiotic resistance cassettes naturally and was also shown to be active in Burkholderia spp. It had been cloned and used as a common promoter to drive the expression of antibiotic-resistant elements or transposase in many broad-host-range vectors (DeShazer and Woods 1996; Choi et al. 2008). Unexpectedly, in this study, we revealed that P1 was the strongest exogenous promoter in B. thailandesis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei to date.

When applicable, the mini-Tn7 transposon system is a convenient and most efficient delivery tool for site-specific genomic tagging of bacteria in which the tagging DNA is stably inserted at a unique and neutral chromosomal site. So far we have utilized different vectors based on such system to make the fluorescent labeling in gram-negative bacteria F. tularensis Schu S4 and LVS (Su et al. 2013), Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, B. thailandensis, B. pseudomallei, and B. mallei. Despite the Tn7 transposition has not yet been documented in gram-positive bacteria, the markerless allelic exchange system developed by Janes and Stibitz (2006) also worked efficiently in tagging both Sterne and Ames strains of B. anthracis, a gram-positive bacteria. As the transcription of the bla1 gene encoding the β-lactamase was silent in the Sterne strain (Chen et al. 2003) coupled with our anticipation of using β-lactam antibiotics as a potential selectable marker, we chose the bla1 locus as the gene replacement target for fluorescent tagging of the B. anthracis.

In summary, what is the importance and utility of such GFP or RFP constitutively expressed strains? Undoubtedly, they will be beneficial for fundamental microbiological studies and can be applied to a variety of important and very revealing types of new and important information. These include (i) high-throughput compound screening (especially requiring at least a 200 msec time frame for HTS microscopy), (ii) virulence studies, (iii) vaccine development, (iv) in vivo animal models, (v) infective indices experiments, (vi) intramacrophage survival studies, as well as (vii) siRNA screening.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the United States Defense Threats Reduction Agency INSIGHTS Program. We wish to thank Scott Stibitz (Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, FDA, Bethesda, MD), Herbert P. Schweizer (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO), and Tung T. Hoang (University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii) for generously providing us strains, plasmids, and technical advice. We also thank Chet Closson (Live Microscopy Core, Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) for assistance with fluorescent microscopy.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Genes of Bacillus anthracis Ames identified by bioinformatic analysis to be expressed at high, medium, or moderately low levels with minimal variation during culture or macrophage infection. The analysis was based on affymetrix data sets http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/ (accession number E-MEXP-1036) (Bergman et al. 2007), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE840 (Liu et al. 2004), and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GPL370. See Materials and Methods section for details.

Table S2. Genes of Yersinia pestis CO92 identified by bioinformatic analysis to be expressed at high, medium, or moderately low levels with minimal variation during culture or macrophage infection. The analysis was based on affymetrix data sets http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE3793 (Sebbane et al. 2006), and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE16493 (Vadyvaloo et al. 2010). See Materials and Methods section for details.

Table S3. Genes of Burkholderia pseudomallei K96243 identified by bioinformatic analysis to be expressed at high, medium, or moderately low levels with minimal variation during culture or macrophage infection. The analysis was based on affymetrix data sets http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GPL4078,http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE5495 (Rodrigues et al. 2006), http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/arrays/A-MEXP-206/, and http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/experiments/E-MEXP-334/files/. See Materials and Methods section for details.

References

- Becher A. Schweizer HP. Integration-proficient Pseudomonas aeruginosa vectors for isolation of single-copy chromosomal lacZ and lux gene fusions. Biotechniques. 2000;29:952. doi: 10.2144/00295bm04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman NH, Anderson EC, Swenson EE, Janes BK, Fisher N, Niemeyer MM, et al. Transcriptional profiling of Bacillus anthracis during infection of host macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:3434–3444. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01345-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland DM, Eisele NA, Keleher LL, Anderson PE. Anderson DM. Novel genetic tools for diaminopimelic acid selection in virulence studies of Yersinia pestis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumann D. In vivo visualization of bacterial colonization, antigen expression, and specific T-cell induction following oral administration of live recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:4618–4626. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4618-4626.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW. Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Succi J, Tenover FC. Koehler TM. β-lactamase genes of the penicillin-susceptible Bacillus anthracis Sterne strain. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:823–830. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.823-830.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Gaynor JB, White KG, Lopez C, Bosio CM, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, et al. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nmeth765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, DeShazer D. Schweizer HP. mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with multiple glmS-linked attTn7 sites: example Burkholderia mallei ATCC 23344. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:162–169. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Mima T, Casart Y, Rholl D, Kumar A, Beacham IR, et al. Genetic tools for select-agent-compliant manipulation of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:1064–1075. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02430-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack BP, Valdivia RH. Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShazer D. Woods DE. Broad-host-range cloning and cassette vectors based on the R388 trimethoprim resistance gene. Biotechniques. 1996;20:762–764. doi: 10.2144/96205bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gat O, Inbar I, Aloni-Grinstein R, Zahavy E, Kronman C, Mendelson I, et al. Use of a promoter trap system in Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus subtilis for the development of recombinant protective antigen-based vaccines. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:801–813. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.801-813.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R, Cubitt AB. Tsien RY. Improved green fluorescence. Nature. 1995;373:663–664. doi: 10.1038/373663b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden MT, Titball RW, Peacock SJ, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Atkins T, Crossman LC, et al. Genomic plasticity of the causative agent of melioidosis, Burkholderia pseudomallei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:14240–14245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403302101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes BK. Stibitz S. Routine markerless gene replacement in Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:1949–1953. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1949-1953.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Norris MH, Barrett AR, Wilcox BA. Hoang TT. Engineering of tellurite-resistant genetic tools for single-copy chromosomal analysis of Burkholderia spp. and characterization of the Burkholderia thailandensis betBA operon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:4015–4027. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02733-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Janes BK, Passalacqua KD, Pfleger BF, Bergman NH, Liu H, et al. Biosynthetic analysis of the petrobactin siderophore pathway from Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:1698–1710. doi: 10.1128/JB.01526-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque C, Brassard S, Lapointe J. Roy PH. Diversity and relative strength of tandem promoters for the antibiotic-resistance genes of several integrons. Gene. 1994;142:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SF. Knudson GB. Comparative efficacy of Bacillus anthracis live spore vaccine and protective antigen vaccine against anthrax in the guinea pig. Infect. Immun. 1986;52:509–512. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.509-512.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Bergman NH, Thomason B, Shallom S, Hazen A, Crossno J, et al. Formation and composition of the Bacillus anthracis endospore. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:164–178. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.1.164-178.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez CM, Rholl DA, Trunck LA. Schweizer HP. Versatile dual-technology system for markerless allele replacement in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:6496–6503. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01669-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch EF. Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Massey S, Johnston K, Mott TM, Judy BM, Kvitko BH, Schweizer HP, et al. In vivo Bioluminescence Imaging of Burkholderia mallei Respiratory Infection and Treatment in the Mouse Model. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:174. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough KA. Falkow S. A Yersinia pestis-specific DNA fragment encodes temperature-dependent coagulase and fibrinolysin-associated phenotypes. Mol. Microbiol. 1989;3:767–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WG. Lindow SE. An improved GFP cloning cassette designed for prokaryotic transcriptional fusions. Gene. 1997;191:149–153. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris MH, Kang Y, Lu D, Wilcox BA. Hoang TT. Glyphosate resistance as a novel select-agent-compliant, non-antibiotic-selectable marker in chromosomal mutagenesis of the essential genes asd and dapB of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:6062–6075. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00820-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris MH, Kang Y, Wilcox B. Hoang TT. Stable, site-specific fluorescent tagging constructs optimized for Burkholderia species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:7635–7640. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01188-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AE. Bermudez LE. Expression of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in mycobacterium avium as a tool to study the interaction between Mycobacteria and host cells. Microb. Pathog. 1997;22:193–198. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J, Wren BW, Thomson NR, Titball RW, Holden MT, Prentice MB, et al. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague. Nature. 2001;413:523–527. doi: 10.1038/35097083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra F, Britton P, Castle C, Jones-Mortimer MC. Kornberg HL. Two separate genes involved in sulphate transport in Escherichia coli K12. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1983;129:357–358. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-2-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poschet JF, Boucher JC, Tatterson L, Skidmore J, Van Dyke RW. Deretic V. Molecular basis for defective glycosylation and Pseudomonas pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13972–13977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241182598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues F, Sarkar-Tyson M, Harding SV, Sim SH, Chua HH, Lin CH, et al. Global map of growth-regulated gene expression in Burkholderia pseudomallei, the causative agent of melioidosis. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:8178–8188. doi: 10.1128/JB.01006-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AE, Stuckey JA, Zhao Y, Matthews HR, Patton WA, Moss J, et al. Expression, characterization, and mutagenesis of the Yersinia pestis murine toxin, a phospholipase D superfamily member. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11824–11831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer HP. Peacock SJ. Antimicrobial drug selection markers for Burkholderia pseudomallei and B. mallei. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14:1689–1692. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.080431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebbane F, Lemaitre N, Sturdevant DE, Rebeil R, Virtaneva K, Porcella SF, et al. Adaptive response of Yersinia pestis to extracellular effectors of innate immunity during bubonic plague. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11766–11771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601182103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R, Priefer U. Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-Negative bacteria. Bio-Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- Stibitz S. Carbonetti NH. Hfr mapping of mutations in Bordetella pertussis that define a genetic locus involved in virulence gene regulation. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:7260–7266. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7260-7266.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Saldanha R, Pemberton A, Bangar H, Kawamoto SA, Aronow B, et al. Characterization of stable, constitutively expressed, chromosomal green and red fluorescent transcriptional fusions in the select agent bacterium, Francisella tularensis Schu S4 and the surrogate type B live vaccine strain (LVS) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97:9029–9041. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titball RW. Williamson ED. Vaccination against bubonic and pneumonic plague. Vaccine. 2001;19:4175–4184. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadyvaloo V, Jarrett C, Sturdevant DE, Sebbane F. Hinnebusch BJ. Transit through the flea vector induces a pretransmission innate immunity resistance phenotype in Yersinia pestis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000783. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia RH. Falkow S. Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science. 1997;277:2007–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongtrakoongate P, Mongkoldhumrongkul N, Chaijan S, Kamchonwongpaisan S. Tungpradabkul S. Comparative proteomic profiles and the potential markers between Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia thailandensis. Mol. Cell. Probes. 2007;21:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M. Tsang JS. Use of ribosomal promoters from Burkholderia cenocepacia and Burkholderia cepacia for improved expression of transporter protein in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 2006;49:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycki-Siek J, Norris MH, Kang Y, Sun Z, Bluhm AP, McMillan IA, et al. Elucidating the Pseudomonas aeruginosa fatty acid degradation pathway: identification of additional fatty acyl-CoA synthetase homologues. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Genes of Bacillus anthracis Ames identified by bioinformatic analysis to be expressed at high, medium, or moderately low levels with minimal variation during culture or macrophage infection. The analysis was based on affymetrix data sets http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/ (accession number E-MEXP-1036) (Bergman et al. 2007), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE840 (Liu et al. 2004), and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GPL370. See Materials and Methods section for details.

Table S2. Genes of Yersinia pestis CO92 identified by bioinformatic analysis to be expressed at high, medium, or moderately low levels with minimal variation during culture or macrophage infection. The analysis was based on affymetrix data sets http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE3793 (Sebbane et al. 2006), and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE16493 (Vadyvaloo et al. 2010). See Materials and Methods section for details.

Table S3. Genes of Burkholderia pseudomallei K96243 identified by bioinformatic analysis to be expressed at high, medium, or moderately low levels with minimal variation during culture or macrophage infection. The analysis was based on affymetrix data sets http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GPL4078,http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE5495 (Rodrigues et al. 2006), http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/arrays/A-MEXP-206/, and http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/experiments/E-MEXP-334/files/. See Materials and Methods section for details.