Introduction

In their 1943 study, Luria and Delbrück (156) demonstrated that mutations arise in bacterial cultures before the cells are exposed to selective pressure, thus establishing the dogma that every cell in a culture has a constant probability of acquiring a mutation and that this probability is independent of any advantage that the mutation confers. This dogma was further supported by another influential study in 1952 by the Lederbergs showing that non-selected mutants were localized in spatially distinct populations that arose from the clonal expansion of a single, non-selected mutant progenitor cell (147). In 1964, Herman Müller described a process now known as Müller’s Ratchet (172). As the metaphorical ratchet turns, deleterious mutations accumulate in a small population, ultimately leading to the demise of the lineage. Thus, Müller’s Ratchet exerts a selective pressure on mutation rates, resulting in the evolution of mechanisms to maintain them as low as possible (62). Such mechanisms include base selectivity and proofreading during DNA replication and a plethora of post-replication DNA repair pathways. In fact, it is widely assumed that in the absence of external forces, spontaneous mutation rates in microorganisms are constant. This orthodoxy was essentially unquestioned until it was realized that most selections used to detect mutations were lethal and thus precluded the possibility of detecting mutations that might occur in response to selection (45, 101, 224). Subsequent experiments seemed to show that mutations could, in fact, be induced by selection, the most famous and well-characterized example of which is “adaptive mutation” in Escherichia coli (43, 45). In this module we summarize the data demonstrating that E. coli and Salmonella respond to diverse stressful conditions by increasing their potential for mutation. By so doing, they increase the likelihood that beneficial mutations arise that can relieve the selective pressure. We also describe several experimental systems that have provided insight into what appears to be stress-induced mutagenesis. Finally, we present and comment on arguments for and against stress-induced mutagenesis. We suggest that stress-induced mutagenesis is a general phenomenon, that it is not a laboratory artifact, and that it is not confined to E. coli and Salmonella. Continued investigation into the mechanisms of stress-induced mutagenesis will provide insight into the basic forces underlying adaptive evolution, and will delineate the contribution that non-proliferating cells can make to these processes.

DNA synthesis in non-dividing cells

DNA damage can occur in starved, non-dividing cells due to a variety of environmental and endogenous factors. While extensive DNA replication does not occur under these conditions, a number of early studies showed that some DNA is synthesized in starving E. coli cells, a necessary precursor if the DNA damage is to lead to mutations (53, 99, 103, 174, 213, 214). In fact, the phenomenon of stationary-phase mutation was first described in the late 1960s and attributed to repair DNA synthesis (98). A study published in 1979 by Tang and colleagues (245) demonstrated that when stationary-phase E. coli cells were suspended in buffer lacking nitrogen and carbon sources but containing tritium-labeled thymidine, about 2% of their DNA became labelled over a period of about six hours. However, during this period, there was no net change in the amount of DNA. Because DNA polymerase I (Pol I, encoded by the polA gene) was required for incorporation, the authors concluded that the DNA was being continuously degraded and then resynthesized by Pol I. More recent studies have implicated various mechanisms by which DNA synthesis can be stimulated in quiescent cells (reviewed in references 30, 32). Taken together, these data demonstrate that DNA metabolism with the capacity to produce mutations occurs in non-dividing cells, a requirement for many of the processes that are discussed in the following sections.

Stress Responses Increase Mutagenic Potential

The SOS Response to DNA Damage

Cells are constantly exposed to DNA damage from both endogenous and exogenous sources. As maintenance of genetic integrity is critical for life, cells have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to minimize the deleterious effects of these damaging agents. One example of such a mechanism is the SOS response. The SOS response is covered in detail in Eco-Sal III Module 5.4.3. “The SOS Regulatory Network, and Module 7.2.8. “The SOS Response”, and so only a brief description is included here. The initial signal for the induction of the SOS response is the formation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) that is then bound by the RecA recombinase, forming a nucleoprotein complex. When in the nucleoprotein complex RecA is “activated” and promotes the autocleavage of the SOS repressor, LexA, resulting in the derepression of the genes of the SOS regulon. At least 30 genes are regulated by LexA (54, 70, 120). Although the functions of the SOS proteins are diverse, most promote cell recovery from DNA damage by participating in pathways for DNA repair or recombination, or by modulating DNA replication to cope with lesions that block the replication fork.

The most obvious stress that induces the SOS response is exposure to DNA damaging agents. Bulky lesions in the DNA, as well as single- and double-strand breaks, are acted upon by various repair functions that produce the SOS-inducing signal, single-stranded DNA. In addition, single-stranded DNA can be formed by a variety of intracellular processes such as failed chromosome segregation, defects in DNA replication and recombination, defects in nucleotide metabolism, and DNA damage from metabolic intermediates (178). During conjugal transfer of the F plasmid, single-strand DNA enters the recipient cell and, after forming a complex with RecA, can induce the SOS response; however, F also encodes an inhibitor of SOS induction, PsiB, which limits the SOS response during conjugal transfer (9). In addition to conjugation, loss of the double-stranded F plasmid can also induce the SOS response because the plasmid-encoded CcdB toxin inhibits DNA gyrase, leading to double strand breaks (55).

External forces and environmental conditions that do not obviously damage the DNA can also induce the SOS response. For example, exposure to high hydrostatic pressure induces the SOS response via the DNA double-strand break repair pathway (1-3). While the initial trigger is external, the double strand breaks are caused by a cryptic endonuclease encoded on the E. coli chromosome; processing of the double-strand breaks by RecBCD produces the SOS-inducing single-stranded DNA. Changes in nutrient availability can also induce the SOS response. For example, when cells starved for a required amino acid are allowed to resume growth with glycerol as a carbon source, the SOS response can be induced via a cyclic-AMP-dependent pathway (117). Finally, cell wall stress, particularly exposure to certain antibiotics, can induce the SOS regulon through the DpiBA two-component system (167).

While the RecA-ssDNA complex is typically required for LexA cleavage and induction of the SOS response, this requirement is relaxed under conditions that destabilize LexA independently of DNA damage. LexA becomes unstable under weakly alkaline conditions in vitro (150) an effect that could help cells cope with DNA damage caused by alkaline environments. LexA is also inactivated in aging colonies (244) and in liquid cultures as they reach saturation (63).

Role of error-prone DNA polymerases in stress-induced mutagenesis (also see Eco-Sal III Module 7.2.2. “Translesion DNA Synthesis.”)

Because single-stranded DNA can arise from a variety of conditions, the SOS response may serve as a mechanism to introduce genetic variability in addition to helping cells to recover from DNA damage. E. coli’s two error-prone DNA polymerases, DNA polymerase IV (Pol IV, encoded by the dinB gene) and DNA polymerase V (Pol V, encoded by the umuDC genes), which are upregulated as part of the SOS response, may provide such a function. A third DNA polymerase, DNA polymerase II (Pol II, encoded by the polB gene), is also induced as part of the SOS response and is capable of coping with various types of DNA damage (115); however, with the exception of error-prone synthesis past certain DNA lesions (175), Pol II is generally error-free. Pol IV and Pol V belong to the conserved Y-family of DNA polymerases, members of which are characterized by low processivity and low fidelity even when the template DNA is undamaged. Both polymerases have the ability to replicate past DNA lesions, although they differ in the spectrum of lesions that they can accommodate. Pol IV can also extend DNA synthesis from misaligned or mispaired primer/template termini, a property that may allow Pol IV to participate in replication restart. Replication restart is also likely to be the underlying role of Pol IV in adaptive mutation (which is discussed below).

Pol IV interacts with the replication-associated DNA helicase Rep, and this interaction enhances both Pol IV’s polymerase activity and Rep’s helicase activity (226). In addition, Rep is required for normal levels of Pol IV-dependent adaptive mutation (see below). Given the known role that Rep plays in replication restart, these results suggest that Rep assists in loading Pol IV on the DNA after replication has been stalled (226, 235).

In cells that are growing exponentially in rich medium when the SOS regulon is not induced, Pol V is undetectable (263); consequently, loss of Pol V has little effect on spontaneous mutation rates (133). In contrast, in uninduced cells there are about 250 copies of Pol IV (124), a relatively high copy number compared to the 10-20 copies of Pol III (267). Despite its abundance, under normal growth conditions Pol IV also makes little contribution to spontaneous mutation rates, at least on the chromosome. In contrast, Pol IV is responsible for many of the mutations that occur in stationary phase cells (discussed below). These properties suggest that the mutagenic activity of Pol IV is tightly regulated or targeted in normally growing cells, but becomes activated in non-growing cells. Table 1 lists several factors that have been shown to regulate the amount, stability, or activity of Pol IV. Since these factors are involved in various stress responses, their regulation of Pol IV will be discussed in more detail below. In addition, data have been presented that Pol IV’s activity is controlled by direct interactions with RecA and UmuD (94).

Table 1.

Stress-response Regulation of Pol IV

| Factor | Stress-response | Type of Regulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RecA/LexA | SOS | Transcriptional activation/repression | (121, 123) |

| RpoS | General stress response | Direct transcriptional activation | (145) |

| GroE | Heat-shock response | Enhancement of protein levels | (146) |

| Ppk | Nutritional deprivation | Probably direct; required for full mutagenic activity and translesion bypass | (238) |

| HU | Growth phase; nutrient limitation; cold-shock | Indirect, Huαβ heterodimer required for full mutagenic activity | (260) |

| Rep DNA helicase | None known | Probably direct; enhances polymerase activity, required for full mutagenic activity | (52, 226) |

Non-induced levels of Pol IV can contribute to mutation on extra-chromosomal elements. For example, Pol IV is required for untargeted mutagenesis of λ phage in UV irradiated E. coli cells (37). In normally growing cells, Pol IV made a significant (about 4-fold) contribution to mutation rates of a lac reporter on the F′128 episome (133). Part of this effect was because the cells carried two copies of the dinB gene, one on the chromosome and one on the F′ episome; but, mutation rates of chromosomal genes were not affected by the extra copy of dinB (133). In a separate study, deletion of the dinB gene from both the chromosome and the episome caused a 3-fold reduction of the reversion rate of a mutant tetA gene located on the episome (235).

Upon induction of the SOS response, the levels of Pol IV and Pol V increase dramatically, to about 2000 and 200 molecules per cell, respectively (124, 263). By using E. coli strains constitutive for the SOS response, the effects of up-regulation of Pol IV and Pol V on the “SOS mutator activity” can be evaluated independently of DNA damage. In one study, loss of Pol IV resulted in 50 to 70% fewer base substitution mutations in a lac reporter, whereas loss of Pol V completely abolished the SOS mutator activity (132). Competition between E. coli’s five DNA polymerases was examined by determining their individual and joint mutational spectra in an rpoB reporter (which scores mutation to rifampicin resistance) (56). Pol IV and Pol V were required for most transversion mutations, while transition mutations mostly required Pol I. Interestingly, the presence of Pol IV or Pol II altered mutation by Pol I at a specific site in the rpoB target, suggesting that the different polymerases compete for substrates and can modulate the other’s activities. Competition could occur at the point of base-insertion, or at the point of extension from a mispaired terminus.

While expression of Pol IV from the F′ episome and other low copy plasmids has a mild (2-to 10- fold) mutagenic effect (132, 133), overexpression of Pol IV from a high copy plasmid typically increases spontaneous mutation frequencies up to 200- fold (257, 260, 262), and, in one case, 1000-fold (123). The actual degree of enhancement depends not only on the plasmid used, but also on whether the target is on the chromosome or on the episome and whether the mutation is a base substitution or a frameshift.

Pol V’s translesion bypass activity requires that the polymerase subunit, UmuC, is in a complex with two proteolytically processed copies of UmuD, called UmuD′, and that this heterotrimer interacts with a RecA-ssDNA filament (179). These complex requirements limit measurements of Pol V-dependent mutagenesis using simple overexpression studies. However, Pol V homologs with simpler requirements are found on naturally occurring genetic elements, and these polymerases can be used as proxies for Pol V. The IncJ conjugal transposon R391 encodes a Pol V homolog, RumAB, and a more mutagenic form of RumAB, RumA′B, was engineered to model UmuD′C (242). In a strain lacking umuDC, constitutive for the SOS response, and carrying the recA718 allele, which encodes a RecA protein that is constitutively activated (261), overexpression of RumA′B from a low copy plasmid increased the spontaneous mutation frequency in E. coli cells 3- to 12-fold more than expressing UmuD′C from the same plasmid (164). But strains carrying the R394 plasmid, which also encodes a Pol V homolog, have low mutation rates after MMS exposure (128). These observations suggest that the mutagenic potential of these Pol V-like proteins may be relevant only under novel conditions, and/or that the intact plasmids carry inhibitors of the mutagenic activity of the polymerases (128).

The General Stress Response

When E. coli and Salmonella are subjected to nutrient limitation, a complex and sophisticated cascade of events is induced. Because this response is not specific to a particular environmental condition (such as depletion of a specific amino acid), it has been called the “general” stress response (for a reviews, see reference 13, Eco-Sal III Section 5.3. “Sensing and Responding to Nutrient Availability” and Section 5.6. “Physiological and Genetic Adaptation to Growth Arrest”). The central regulator of the general stress response is the sigma factor RpoS (also known as KatF, σ38, and σS). Sigma factors are the subunits of RNA polymerase (RNAP) that target the transcription machinery to specific promoters. (The RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing a specific sigma factor, e.g. σ70 or σ38, is indicated as Eσ70 or Eσ38). During exponential growth, most RNA polymerase molecules contain the vegetative sigma factor σ70σ(RpoD), and the amount and activity of σ38 is tightly controlled. Under stressful conditions, both the amount and the activity of σ38 is upregulated and Eσ38 becomes prevalent, resulting in the transcription of genes encoding proteins that promote survival. Over 200 genes are directly or indirectly regulated by Eσ38; these are collectively known as the Eσ38 or RpoS regulon (59, 142, 180, 190, 256, 259). The general stress response is linked to two mechanisms that can increase mutation rates: induction of Pol IV, and down-regulation of mismatch repair.

Approximately ten hours after the onset of stationary phase, the level of Pol IV increases 3-fold in wild-type cells but declines precipitously in rpoS mutant cells, so that after 48 hours in stationary phase there is a 25- to 50- fold difference in Pol IV levels between wild-type and rpoS mutant cells (145). This effect appears to be mostly or entirely due to direct transcription of dinB by Eσ38 (145, 234). As mentioned above, the SOS response may be partially induced in stationary-phase cells, but regulation of dinB by RpoS is independent of the SOS response (145). The roles that Pol IV may play in stationary phase are not fully understood. RpoS-dependent upregulation of Pol IV is required for adaptive Lac+ reversion (discussed below). In addition, when stationary phase cells are incubated for extended periods of time, cells lacking Pol IV compete poorly with wild-type cells in mixed populations (270). This loss of “growth advantage in stationary phase (GASP)” also occurs in cells missing Pol V or Pol II, suggesting that these polymerases have important functions during prolonged starvation. For example, they may be required for the repair of DNA damage occuring in stationary phase cells, or error-prone DNA synthesis may be required to generate the mutations that lead to the GASP phenotype.

In stationary-phase cells the proteins involved in mismatch repair (MMR) decline (for a review of MMR see reference 136 and Eco-Sal III Module 7.2.5. “Mismatch Repair”). Normally MMR is active in stationary-phase cells (75, 193); however, the levels of two MMR proteins, MutS (the mismatch binding protein) and MutH (the endonuclease that initiates repair by incising the nascent DNA strand) decline via an RpoS-dependent mechanism (69, 254). The degree to which this decline is responsible for increased mutations in stationary-phase cells is disputed. That the frequency of mutations in stationary phase cells declines when MMR proteins are over-expressed (24, 81, 88, 104, 275) supports the hypothesis that MMR is limiting in at least some stationary-phase cells. However, which specific MMR proteins are limiting is unclear. Three studies found that over-expression of MutS reduces stationary-phase mutations (24, 75, 275), one study found that over-expression of MutS and MutL together had the maximum effect (75), whereas two studies found that over-expression of MutL alone was sufficient (88, 104). However, overproduction of one or more of these proteins also reduced mutation frequencies in growing cells (75), suggesting that MMR is no more limiting in stationary-phase cells than in exponential-phase cells.

That decline of MMR in stationary phase cells can increase mutation frequencies is also supported by a phenomenon known as “mutagenesis in aging colonies,” or MAC, (24). During seven days of incubation, the mutant frequencies in aging colonies appeared to increase by two orders of magnitude. However, a mutS mutant strain had a similar mutant frequency on day one as the wild-type strain had after seven days of incubation; furthermore, the mutant frequency of the mutS mutant strain did not increase with aging. The simplest explanation for this result is that a decline in MMR is responsible for the increased mutation rate in the aging colonies. However, this conclusion has been questioned (264). Other experiments with MMR defective cells support the relevance of MMR in stationary-phase mutation. During adaptive mutation experiments, a subpopulation of the cells is in a state of hypermutation (200, 253). While loss of MMR (via mutation of mutL) caused a large increase in the mutation rate of the cells overall, it had no effect on the mutation rate of the hypermutating subpopulation (200). This result suggests that the increased mutation rate in the hypermutating subpopulation was due to a decline in MMR (or in another pathway that requires MutL). However, it must be emphasized that a decline in MMR cannot cause new mutations, but can only increase the probability that errors made by some other process will be preserved as mutations. The high mutation rate in some stationary phase cells may be due to an additive effect of errors made by DNA polymerases, such as Pol IV, and their preservation as mutations due to reduced MMR activity. These observations demonstrate the potentially complex interplay between various RpoS-regulated processes in stationary phase cells.

In addition to nutrient deprivation, several other stress conditions can affect the stability of the RpoS protein, and thus potentially influence mutation rates via the RpoS regulon. When complexed with the adaptor protein RssB (MviA in Salmonella), RpoS is degraded by the ClpXP protease (14, 171, 187, 276, 277). Several anti-adapters that interact with and block the function of RssB can stabilize RpoS under specific stress conditions (27, 28). These anti-adapters include IraP, which is induced by phosphate starvation, IraD, which is induced by exposure to hydrogen peroxide, and IraM, which is induced by magnesium deficiency. Thus the extent to which RpoS acts as a central regulator of mutagenic potential under various conditions is yet to be fully elucidated.

In addition to the fairly straightforward functions for RpoS in stress-induced mutagenesis described above, several less well-characterized activities of RpoS may also influence mutagenic pathways. RpoS impacts stationary-phase adaptive mutation by regulating the abundance of Pol IV, but dinB and rpoS mutations are not epistatic (145). Thus, RpoS has an unknown Pol IV-independent function in adaptive mutation. After prolonged incubation (greater than five days), amplification of the mutant lac allele makes a significant contribution to adaptive mutation, and RpoS is required for this amplification via an unknown mechanism (153). RpoS, among other host factors, has also been shown to be required for formation of araB-lacZ fusions under aerobic, carbon-limiting conditions (95). These fusions are the result of chromosomal rearrangements mediated by the Mu phage inserted between the two genes (224). While the mechanisms of these mutagenic pathways are clearly different, they occur under nutrient-limiting conditions, supporting the hypothesis that RpoS is a central regulator of mutagenesis occurring during nutrient deprivation.

Polyphosphate-Mediated Response to Nutrient Limitation

Although it was first reported in the literature over 100 years ago, inorganic polyphosphate (polyP) remains one of nature’s most enigmatic molecules (see reference 191 for a review). The importance of polyP appears to be primal and universal, as it occurs in bacteria, archaea, plants, and animal cells (39, 134, 135, 170, 216, 273, 274). PolyP is a polymer of orthophosphates that can be tens to hundreds of residues long, each residue linked by a high-energy phosphoanhydride bond. It is synthesized by a highly-conserved enzyme, polyphosphate kinase (Ppk, encoded by the ppk gene in E. coli) that transfers the gamma phosphate from ATP to the growing polyP polymer. In some cells, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, polyP serves primarily as a storage molecule, but the levels of polyP in E. coli and its relatives are far too low (100 uM in E. coli versus 120mM in S cerevisiae, although levels vary widely depending on nutritional status) to provide a source of energy (131). Rather, polyP, which accumulates under various conditions of nutritional stress, appears to be an indicator of the nutritional state of the cell.

In E. coli, polyP accumulates when cells are starved for amino acids, nitrogen, or subjected to sudden osmotic stress. During amino acid starvation exopolyphosphatase (Ppx), the enzyme that degrades polyP, is inhibited by the molecular alarmones guanosine tetra- and penta-phosphate (ppGpp and pppGpp) (138) (ppGpp and pppGpp are discussed below and in Eco-Sal III Module 5.3.5 “Amino Acids and the Stringent Response”). The molecular pathways leading to polyP accumulation during other stresses are not as well studied. Levels of polyP also transiently spike when E. coli is shifted from rich to minimal medium and as cells growing in rich medium enter stationary phase (131). If, however, E. coli is grown with phosphate concentrations in excess of 30mM (as in most minimal media), levels of polyP stay elevated for at least 72 hours in stationary phase (220). PolyP is required for proper expression of rpoS in stationary phase cells (225). How this regulatory role is exerted is not understood; however, polyP can bind to RNA polymerase and direct transcription to specific promoters (139). As discussed above, RpoS levels also respond to a variety of nutritional stresses, such as amino acid deficiencies and nitrogen limitation. Thus polyP may channel the RpoS-regulated pathways for mutagenesis to more specific stress conditions.

Poly P levels may regulate SOS genes independently of DNA damage or of the RecA-LexA regulon. Overexpression of Ppx in E. coli, which reduces polyP levels, increased sensitivity to DNA damage and blocked the induction of recA and umuDC by DNA damaging agents (255). Conversely, overexpression of Ppk, which results in elevated polyP levels, induced recA gene expression, and this induction was independent of DNA damage and RecA (255). Thus polyP may induce the SOS functions, including SOS-dependent mutagenesis, in response to stresses other than DNA damage.

PolyP also has a direct role in regulating mutagenesis (238). Three widely-used assays for measuring Pol IV activity in vivo are: stationary phase adaptive mutation (see below), growth-dependent mutagenesis when Pol IV is overexpressed (123, 238, 262), and resistance to a few DNA damaging agents (148), particularly 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide (118). In a ppk mutant E. coli strain, all three of these Pol IV-dependent activities are decreased but the amount of Pol IV is not affected, indicating that polyP (or possibly Ppk itself) regulates the activity of Pol IV (238). This regulation is independent of both RecA and RpoS, so the regulatory pathways described above are not involved. Pol V-dependent mutagenesis following exposure to UV light is also reduced in ppk mutants (238), but in this case a negative effect on the expression of RecA, an essential cofactor for Pol V activity, has not been ruled out.

Other known activities of polyP may provide insight into its role in these Pol IV- and Pol V-dependent phenotypes. polyP regulates the proteolytic activity of Lon, an important ATP-dependent protease (137, 177). Lon binds to DNA (47), which regulates its proteolytic activity, perhaps by sequestering it away from its substrates (231). PolyP competes with DNA for Lon’s DNA-binding site, stimulating Lon’s proteolytic activity; thus when polyP levels increase during nutrient limitation, it stimulates Lon to degrade proteins for nutrients (137). Similarly, polyP could modulate the activities of DNA polymerases by competing with them for DNA binding. By differentially affecting the activities of high fidelity and low fidelity polymerases, poly P could regulate mutagenesis. In support of this hypothesis, polyP that co-purified with DNA from the fungus Colletotrichum inhibited DNA replication by Taq polymerase in vitro (199). Whatever the mechanism, the accumulation of polyP during stationary phase and under nutrient limiting conditions enhances the activities of both Pol IV and Pol V.

The Stringent Response

The stringent response, which is induced by amino acid limitation, is covered in detail in Eco-Sal III Module 5.3.5. “Amino Acids and the Stringent Response”. Briefly, when cells are starved for amino acids or phosphorous, production of the alarmone (p)ppGpp is stimulated. (p)ppGpp, in association with the accessory protein DksA, binds to RNA polymerase (RNAP), blocks transcription of ribosomal and transfer RNAs (stable RNAs) and directs active RNAP to genes that help the cell to cope with nutrient limitation. One gene that is up-regulated by (p)ppGpp is rpoS (91); this regulation is complex, involving both direct and indirect pathways (28, 38, 141, 143). In addition, many RpoS-regulated genes also require (p)ppGpp for efficient expression (141). Thus, the stringent response, mediated by (p)ppGpp, is intimately intertwined with the general stress response controlled by RpoS, linking the mutagenic processes regulated by RpoS (described above) to the additional stress factors that regulate (p)ppGpp. Microarray analysis has shown that several genes of the SOS regulon are also induced during the stringent response, suggesting that LexA is inactivated (65). Thus the mutagenic potential associated with SOS functions may also be upregulated during amino acid starvation.

In E. coli and B. subtilis (p)ppGpp acts as a replication checkpoint, linking DNA replication to the availability of nutrients that support growth and cell division (97). In E. coli, (p)ppGpp inhibits replication initiation (219), whereas in B. subtilis it inhibits replication elongation (8, 258). At least in the case of B. subtilis, the integrity of the replication fork is not affected and DNA repair proteins are not recruited. Since error-prone DNA polymerases may participate in replication restart (114), (p)ppGpp-induced replication restart may increase the potential for mutations.

Another link between (p)ppGpp and mutagenesis occurs at the level of transcription. Actively transcribed genes have been shown to have increased spontaneous mutation rates in E. coli (15, 16, 125, 126, 266), B. subtilis (212), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (57), and mammalian stem cells (111). Thus transcription-coupled mutagenesis is, at least to some extent, a general phenomenon. Indeed, it has been argued that transcription “directs” mutations to genes whose products are most relevant under adverse conditions (58, 71, 194, 265), and that the selective transcriptional activation of genes is a driving force of evolution (265). In some cases transcription-dependent increases in mutation rates require active RelA (which synthesizes (p)ppGpp), and thus are linked to the stringent response (194, 212). Actively transcribed genes may have higher mutation rates because transcription produces a bubble of single-stranded DNA, and single-stranded DNA is intrinsically more susceptible to DNA damage than is double-stranded DNA (149). In support, recent results suggest that the nontranscribed DNA strand, which forms a loop during transcription, is more susceptible to mutagenesis than the transcribed strand, which is hybridized to RNA (125). To cope with the effect of DNA damage on transcription, E. coli and other organisms have evolved a mechanism, called transcription-coupled repair (TCR), that recruits DNA repair enzymes, particularly the proteins of the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway, to stalled transcription complexes (for more details see reference 165 and Eco-Sal III Module 7.2.4. “DNA Damage Reversal and Excision Repair”). Mfd, the transcription coupling factor in bacteria, is required for stationary-phase mutation in B. subtilis, suggesting that the recruited repair synthesis is responsible for mutations (205). However, Mfd was found not to be necessary for at least one stress-induced mutational pathway in E. coli (33), and loss of Mfd even has a mild mutator phenotype for some mutational targets (125).

A role for transcription in stress-induced mutagenesis is not universal. Adaptive mutation to Lac+ during stationary phase was not increased by inducing transcription of the lac operon with the gratuitous inducer IPTG (80). In another study, reversion to Trp+ in E. coli increased during tryptophan deprivation even in the absence of transcription of the target gene (12). Error-prone DNA synthesis has been linked to transcription in a pathway called transcription-coupled translesion synthesis (51). An interaction between the RNAP-associated protein NusA and DNA Pol IV has been proposed to recruit the polymerase when RNAP is blocked by a gap in the transcribed strand opposite a replication-blocking lesion in the non-transcribed strand. One of the translesion polymerases, DNA Pol II, IV or V could then fill in the gap, allowing transcription to continue. Because of the error-prone activity of Pol IV or Pol V, this process could be mutagenic (52).

The heat- and cold-shock responses

Because bacteria have no mechanism for internal temperature homeostasis, they rely on global responses to temperature shifts called the heat-shock and cold-shock responses. The heat shock response is mainly regulated by the alternative sigma factor RpoH (σ32 or σH), although the extracytoplasmic stress sigma factor, RpoE (σ24 or σE), can also respond to extreme temperature shifts (see references 100, 201, 271, and Eco-Sal III Module 5.4.7 “Envelope Stress Responses”). The RpoH regulon is also induced by carbon source or amino acid starvation, heavy metal exposure, antibiotics, DNA damage, oxidative stress, and bacteriophage infection.

One of the proteins induced as part of the heat shock response is the highly conserved GroE chaperone (the E. coli HSP60). GroE aids in the proper folding and stability of many proteins and is essential even at normal temperatures. GroE is required for the normal levels of both of E. coli’s error-prone polymerases. GroE interacts with the UmuC subunit of Pol V and protects it from proteolytic degradation; thus, when levels of GroE are reduced, UV mutagenesis, which is a function of Pol V, is abolished (60, 61, 151). Likewise, the amount of Pol IV is reduced by 90% in GroE deficient mutant strains. GroE probably directly interacts with Pol IV; the large subunit of GroE (GroEL) was recovered from E. coli whole cell lysates passed over a DinB column (94), and both the large and small subunits co-purified with affinity purified DinB (226). That Pol IV and Pol V levels are stabilized by GroE suggests that the error-prone polymerases may have important functions during exposure to high temperature or other stress conditions that induce the RpoH regulon. In addition, when levels of GroE are low, stationary phase adaptive mutation is reduced even in the absence of Pol IV, suggesting that GroE has some additional mutagenic function (146).

A connection between cold shock and mutagenesis is suggested by the temperature-dependent regulation of the E. coli small histone-like protein, HU, and the transcription factor NusA. (for more information about cold shock see Eco-Sal III Module 5.4.2 “The Cold Shock Response”). In E. coli, HU has two homologous subunits, HUα and HUβ (encoded by the paralogous genes hupA and hupB), and exists in three dimeric forms: HUα2, HUβ2, and HUαβ (211). The relative levels of these forms vary during the cell cycle and under certain stress conditions (50). HUα2 and HUα andβ have higher affinities for most of their substrates than does HUβ2 (184) and are usually the most abundant of the three forms (50). However, the expression of hupB but not of hupA increases after exposure to low temperatures, thus increasing the relative amounts of HUαβ and HUβ2 (92). Cold-shock also results in increased levels of NusA; indeed NusA is one of the most highly induced proteins after temperature downshift (249). Both the HUββ heterodimer (260) and NusA (52) are required for maximum stationary phase adaptive mutation in E. coli (see below). Although the pathways may be different, increased levels of these two factors at low temperatures may facilitate mutagenesis and may account for the observed temperature dependence of adaptive mutation (52, 79).

Other Factors That Affect Mutagenesis

Antibiotics that induce the SOS response

In E. coli and other bacteria, antibiotic treatment can induce the SOS response, resulting in increased mutagenesis that may facilitate the development of resistance (49, 159, 167, 230). Quinolone antibiotics target two essential enzymes involved in DNA replication: DNA gyrase, a type II topoisomerase that releases positive supercoils ahead of the replication fork; and topoisomerase IV, another type II topoisomerase that decatanates intertwined daughter chromosomes (as well as releasing negative supercoils (64, 272). The quinolone antibiotics inhibit topoisomerase activity after DNA cleavage but before the DNA is rejoined, resulting in double strand breaks that induce the SOS response (64, 122). Resistance to quinolone antibiotics is conveyed by point mutations in the chromosomal genes encoding DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, and SOS induction increases the probability of these mutations. In a mouse model system, the quinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin accelerated the development of resistance of pathogenic E. coli (48). In reconstruction experiments the mutations required for ciprofloxacin resistance were dependent on RecA, RecBCD, and the SOS-induced DNA polymerases Pol II, Pol IV, and Pol V (48), genetic requirements similar to adaptive mutation. Also like adaptive mutation, resistant mutants appeared steadily over the course of two weeks when E. coli cells were incubated on medium containing sub-lethal concentrations of ciprofloxacin. In a similar study of infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, deletion of the SOS-regulated polymerase DnaE2 reduced both the virulence of the bacteria and the frequency at which mutations conferring rifampicin resistance arose (26). One possible explanation is that the polymerase simply increases fitness of the bacteria in the mouse; a more stimulating hypothesis is that mutations caused by DnaE2-dependent DNA synthesis enhance adaptation to the host immune response as well as development of antibiotic resistance (26).

Antibiotics can also induce the SOS response independently of DNA damage (167). The sulA (also known as sfiA) gene is one of the most highly up-regulated genes of the SOS regulon (54, 188) and is a potent inhibitor of cell division. β-lactam antibiotics bind to and inactivate penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), a class of proteins involved in cell wall biosynthesis (157). This binding induces the SOS response via the DpiBA two-component signal transduction system; expression of SulA inhibits cell division, rendering the cells temporarily resistant to the antibiotic (167). At the same time, SOS induction of Pol V and Pol IV would lead to an increased mutation rate and a higher probability of mutations rendering the cell resistant to the antibiotic. In particular, Pol IV-dependent mutations are induced by exposure to β-lactam antibiotics, and the induction of the dinB gene after exposure to β-lactam antibiotics is partially independent of RecA/LexA control (182).

Interference with the mechanisms by which the SOS response is induced by antibiotics is a potential target for new classes of antimicrobial agents (230). Likewise, proteins for recombination and DNA repair are potential targets. Because these proteins are conserved (67, 239), such therapeutic agents may have broad antimicrobial applications.

Translation errors caused by antibiotics

In bacteriostatic concentrations, aminoglycoside antibiotics that inhibit translation, such as streptomycin, cause a SOS-independent mutator state known as “translational stress-induced mutagenesis” (11, 195). These antibiotics can affect the fidelity of amino acid incorporation into growing polypeptides (10, 206) potentially altering the activities of proteins involved in DNA replication and repair. Such mistakes during translation were predicted to produce a transient mutator state (176). For example, cells carrying a mutation in the glyV tRNA gene (mutA), which results in glycine being inserted for aspartic acid during translation, are mutators because they express a mutant proofreader subunit of DNA Pol III (5, 6, 228, 229).

Plasmid addiction modules

To ensure their maintenance and propagation in a population, low-copy plasmids, including conjugal plasmids such F, commonly encode plasmid addiction or post-segregational killing systems. The F plasmid carries the Ccd system encoded by the ccdA and ccdB genes (112). CcdB is a potent inhibitor of DNA gyrase and induces the SOS regulon by the same mechanism as do quinolone antibiotics (18, 19, 55). Because the antitoxin CcdA is also being produced, CcdB is not active in cells carrying F under most circumstances. However, a recent study showed that the levels of both CcdA and CcdB increase when cells enter stationary phase (4). The stoichiometry of CcdA and CcdB under various conditions is not known, but if the amount of CcdB exceeds CcdA, SOS induction could occur. Thus, F-encoded functions could gratuitously activate the SOS response, increasing mutation rates without any exogenous DNA damage. As proof of this principle, overexpression of CcdB from a plasmid resulted in a modest increase in adaptive reversion to Lac+ of an F′ encoded lac allele (4).

Specific Systems for the Study of Stress-Induced Mutagenesis

As described above, states of transient genetic instability can be induced by a number of environmental factors. In most of these cases, the stimuli are linked to the resulting genetic instability via complex pathways; thus, these mutator states do not provide tractable systems for the study of stress-induced mutation. However, several genetic systems have been developed that allow the investigation of changes in mutation rates in response to well-defined conditions. The examples presented below are not exhaustive and other systems exist for E. coli and other organisms (113, 116, 119, 130, 217, 246, 248); however, these examples are representative of the types of model systems used to study stress-induced mutagenesis.

Mutagenesis due to spontaneous DNA damage

As a bacterial population exhausts its resources, metabolic and local environmental conditions can result in spontaneous DNA damage. As discussed above, such damage can result in induction of the SOS response and a general increase in mutation rates. In other cases, specific pre-mutagenic lesions can cause mutations independently of SOS functions. A number of experimental systems have been devised to provide insight into these pathways.

Oxidative damage appears to be a significant factor leading to DNA damage and mutation in both growing cells (20, 169, 215) and in nutritionally deprived cells (17, 21, 31, 34-36, 66). Reactive oxygen species are the normal products of metabolism in aerobic environments, but unless controlled, reactive oxygen species are destructive to many cellular components, including DNA. One particularly mutagenic consequence of oxidative damage is the formation of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanine (8-oxoG), which causes predominantly G:C to T:A transversion mutations (166). Using an experimental system that discriminates between mutations occurring in dividing and non-dividing cells, Bharatan and colleagues (2004) found that MutY (a glycosylase that removes adenines paired with 8-oxoG) (166), MutT (an 8-oxoGTP hydrolase) (166), and glycosylases that remove oxidized pyrimidines, prevented mutations in stationary phase cells (21), supporting the importance of oxidative damage in nutritionally deprived cells.

Various mutant alleles of the trp genes (encoding tryptophan biosynthetic enzymes) revert to Trp+ only by specific mutational events (268, 269), and thus can be used to study how conditions influence these events. E. coli strains carrying some of these mutant trp alleles continuously revert to Trp+ during about ten days of incubation on minimal medium lacking tryptophan. In one study, reversion to Trp+ occurred via A:T to T:A and A:T to C:G transversions, required SOS functions and Pol V, and was enhanced by the plasmid-encoded MucAB homolog of Pol V (20). In contrast, in a separate study of a mutY mutant strain, most Trp+ revertants were due to Pol V-dependent G:C to C:G mutations, although some SOS- and Pol V- independent reversion was also detected (250). Because the mutY defect resulted in a large increase in stationary-phase mutations (35), the authors concluded that 8-oxoG, the substate of MutY, is an important pre-mutagenic lesion in nutritionally starved cells, but that damage leading to A:T transversions also must occur. However, why the loss of MutY would result in G:C to C:G mutations instead of the expected G:C to T:A mutations is unclear, although the authors suggest that MutY can act on 8-oxoG incorrectly paired with G, resulting in the G:C to C:G mutations in the next round of replication (250).

Starved cells are also subject to mutagenic alkylation damage (221). A likely source of such damage is endogenous alkylating agents formed by nitrosation of amides and related compounds (247). Most cells, including E. coli, have several enzymatic activities to repair this type of damage. The Ada and Ogt proteins remove alkyl groups from the O6 position of guanine and the O4 position of thymine (222). In strains lacking one or both of these proteins, the rate of spontaneous mutation in non-growing cells measured at several mutational targets was notably increased (21, 80, 158, 192). Whereas Ogt is constitutively expressed in E. coli, Ada is induced in response to alkylation damage and in stationary-phase cells under RpoS control (247). DNA Pol IV, which is also regulated in stationary-phase cells by RpoS (145), is involved in tolerance of alkylation damage, presumably because it can bypass alkylated bases in the DNA (23). The existence of multiple mechanisms to minimize the deleterious effects of alkylation damage in non-growing cells suggests that this type damage is a particularly potent mutagenic force. The regulation of both Ada and Pol IV in stationary-phase cells by RpoS further suggests that cells have evolved a coordinated system for combating alkylation damage during nutritional limitation.

Mutagenesis on solid surfaces I: Resting organisms in a structured environment (ROSE)

By placing a reporter gene (the gal operon) under control of the λ phage genetic switch (inactivation of the CI repressor), Taddei and colleagues showed that the SOS response is induced in aging colonies without the need for any exogenous stimulus (244). SOS induction under these conditions required RecA and RecB, implying that RecBCD processing of double strand ends was required to produce the SOS initiating signal. While RpoS was dispensable, adenylate cyclase, the enzyme responsible for cAMP production, was required. Since intracellular concentrations of cAMP increase dramatically in nutritionally limited cells (40), these results suggest that SOS was being induced by DNA double-strand breaks occurring as consequence of starvation. Taddei and colleagues found a 9-fold increase in the frequency of rifampicin resistant (RifR) mutants in seven-day old colonies relative to one-day old colonies, suggesting that SOS induction leads to increased mutagenesis in starving cells. Interestingly, while a similar induction of the SOS response occurred in liquid cultures, no change in mutation frequency was detected. Thus the special conditions pertaining to growth in a colony on a solid substrate appeared to be required for this mutagenic effect (243). This mutational phenomenon was called ROSE mutagenesis, for “resting organisms in a structured environment.” In subsequent studies ROSE mutagenesis was shown to require uvrB (a component of nucleotide excision repair), and DNA polymerase I (Pol I), but not Pol V (Pol IV was not tested), suggesting that the mutations arise during nucleotide excision repair (243).

Why growth in a colony is required for this type of starvation-induced mutagenesis is not obvious. As discussed above, other studies have shown that inactivation of the enzymes that repair oxidative DNA damage results in significant increases in mutation rates in cells aging on solid media (17, 21, 31, 34, 36, 158, 192). That ROSE requires SOS functions, nucleotide excision repair, double-strand break repair, and Pol I, suggest that cells in colonies experience DNA damage by agents unique to this growth condition.

Mutagenesis on solid surfaces II: Mutagenesis in aging colonies

Most studies of stress-induced mutagenesis have used laboratory strains of E. coli, thus it is possible that genetic changes accompanying domestication have influenced the observed mutagenic processes. To address this issue Bjedov and colleagues (24) collected 787 natural isolates of commensal and pathogenic E. coli over a wide geographical range and from diverse environmental niches. They compared the frequency of RifR mutant cells in one- and seven-day old colonies and called the ratio MAC, for “mutagenesis in aging colonies”. Among all the isolates the average increase in the frequency of RifR mutant cells was seven-fold, slightly higher than that of the laboratory strain, MG1655. Over the same period there was, on average, less than a twofold increase in the number of cells in the colonies. About 3% of the isolates were constitutive mutators (high RifR frequency on day one). Among the other isolates, the ratio of day seven to day one frequencies ranged widely (up to 100-fold). Pathogenic strains were more frequently constitutive mutators, whereas commensal strains typically had higher MAC. Interestingly, there was a negative correlation between the MAC phenotype and the constitutive mutator phenotype, suggesting that the two are mutually exclusive. Using ten randomly chosen isolates, Bjedov (24) further showed that MAC required carbon-source starvation on solid medium (like ROSE, see above) and aerobic conditions. In one strain with a particularly strong MAC phenotype, MAC was found to require RpoS, cyclic-AMP, the cAMP receptor protein (CAP), and RecA, but not LexA inactivation. The latter result suggests a requirement for recombination but not for other SOS functions. MAC was reduced by overproduction of MutS, suggesting that a decline in mismatch repair contributes to the mutagenesis. While MAC and ROSE share a number of features, they differ in that MAC requires DNA Pol II, rather than Pol I, and does not require nucleotide excision repair.

A subsequent report argued that the MAC phenotype is not due to increased mutation rates in aging cells, but is, instead, a consequence of growth advantages conferred by mutations in the rpoB gene that that confer RifR (264). In support of this hypothesis, Wrande and colleagues (264) demonstrated that RifR mutants were localized in defined regions of colonies and RifR cells from the same region had the same mutations, suggesting that clones of RifR cells grew from an early arising mutant. Also, the increase of RifR mutant frequency measured over 28 days could be fit to a logarithmic curve, suggesting that the RifR mutants were growing, not appearing as a result of independent mutational events. Finally, reconstruction experiments showed that certain RifR mutants did, in fact, have an apparent growth advantage in aging colonies. While these data appear to be compelling, they are not conclusive since they do not address a number of points in the original study. In reconstruction experiments with a number of different rpoB mutants, Bjedov and colleagues (24) showed that the number of added RifR cells in aging colonies remained constant or slightly declined. When constitutive mutator strains (such as mutS or mutT mutants) were incubated for seven days, their initial high frequencies of RifR mutants did not further increase, as would be expected if RifR mutants were selectively advantaged. Finally, among isolates there was a positive correlation between mutation to LacI- and mutation to RifR (24), implying that mutagenesis in aging colonies is not restricted to the rpoB gene. If the MAC phenomenon is ultimately substantiated, then it is the most general example to date of stress-induced genetic variability.

Adaptive mutation in E. coli strain FC40

Adaptive mutation has been most widely studied using the Foster-Cairns system for detecting stress-induced mutations, which relies on a Lac- strain of E. coli called FC40. When FC40 is incubated with lactose as the sole carbon and energy source, revertants to Lac+ appear over the course of several days (Fig. 1) (43). The Lac+ mutations arise in the static population and have unique genetic requirements, suggesting novel mechanisms specific to nutriotionally starved cells. This phenomenon, now called adaptive mutation (43), was originally called “directed mutation” because it was interpreted to be a mechanism by which mutations could be directed to the specific genes that would relieve the selective pressure. While this interpretation was not substantiated by subsequent experimentation, adaptive mutation remains an intriguing phenomenon. Despite extensive data, a consensus has not yet been reached regarding the mechanism and significance of adaptive mutation. Here we summarize the data and discuss the controversies and implications of the alternative models.

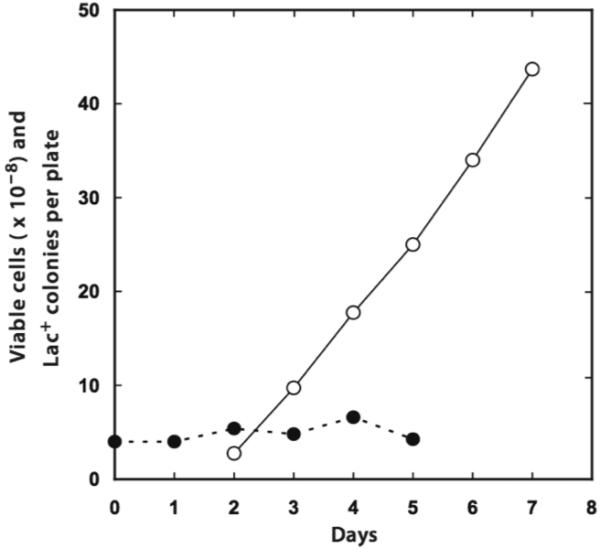

Figure 1.

Adaptive mutation to Lac+ in E. coli strain FC40. Six cultures of FC40 were grown to saturation in liquid M9-glycerol medium. Aliquots containing 3 X 108 FC40 cells were mixed with 109 scavenger cells and spread on M9-lactose plates. On each day, small circular samples were removed from one of each set of six plates (avoiding any visible Lac+ colonies) and were vortexed with 1 ml M9; the viable titer of FC40 in these suspensions was assayed on rifampicin-peptone plates (filled circles). The Lac+ colony counts (open circles) are the averages for 23 plates. (Reproduced with permission from The Genetics Society of America [43].)

Genetic properties of strain FC40 (see Fig. 2)

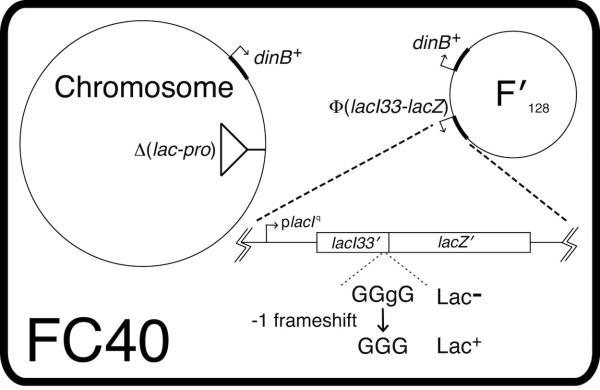

Figure 2.

The genetic structure of E. coli strain FC40. FC40 is deleted for the (lac-pro) region of the chromosome. A region of chromosomal DNA on the F′128 episome, which includes the Φ(lacI33-lacZ) allele, complements this deletion. The Φ(lacI33-lacZ) allele is a fusion of lacI to lacZ and is expressed from the constitutive lacIq promoter. This fusion normally encodes a functional β-galactosidase protein; however, FC40 is Lac- due to insertion of an extra guanine residue in the lacI region of the fusion. Adaptive Lac+ reversions occur when a -1 frameshift restores the normal reading frame in the Φ(lacI33-lacZ) allele (see text for additional details).

The most studied case of adaptive mutation occurs in E. coli strain FC40 (43). Adaptive Lac+ reversion in FC40 depends on a number genetic features specific to the strain, and these present an ideal dove-tailing of genetic elements on the chromosome and the F′128 episome that it carries. FC40 is a rifampicin-resistant descendent of the strain P90C, which is also known as CSH142 (168). P90C has a deletion of approximately 2.5 minutes of its chromosome including the lac and proAB operons. While dinB (the gene encoding DNA Pol IV) is linked to this region, it is not deleted (124, 236). The deletion, originally known as Δ(lac-pro)XIII but now known as Δ(gptlac)5, is complemented by the F′128 episome, which carries almost three minutes of the E. coli chromosome, including the lac region, proAB, and dinB (129). The lac allele on the episome carried by FC40Φ(lacI33-lacZ), has three mutations: the lacIq mutation that increases transcription from the lacI promoter (218); a deletion that fuses lacI to lacZ, removing the entire lac operon regulatory region and putting the operon under control of the constitutive lacIq promoter (29, 173); and, a +1 frameshift mutation in lacI, lacI33, changing a run of three G:C basepairs to four (46). The lacI33 mutation is polar on lacY, making FC40 defective for the lactose permease. Because of the way that F′128 was formed, dinB is closer to lac on the episome than it is in its normal position on the chromosome (129). While FC40 is phenotypically Lac-, some residual β-galactosidase activity (about 2 Miller units) is present, probably as a consequence of ribosomal frameshifting. Because the lacIq promoter is weaker than the lac promoter, a true Lac+ revertant of FC40 makes about 200 Miller units of β-galactosidase instead of the 1000 Miller units produced by fully induced wild-type strains. Because of this low level of β-galactosidase activity, Lac+ revertants of FC40 take two days to produce Lac+ colonies on lactose (43, 77).

Measurement of adaptive mutation

Measurement of adaptive mutation requires that lactose be the only carbon source available for metabolism by FC40. When incubated in liquid minimal lactose medium, the number of Lac- cells is constant for several days (77); however, when FC40 is plated on solid minimal lactose medium the cells can double several times in the first few days after plating due to impurities in the agar (43). To limit this growth, FC40 is plated with an excess of Lac- “scavenger cells” that can neither revert to Lac+ nor recombine with FC40 to produce Lac+ recombinants (43). For a typical adaptive mutation experiment, FC40 cells are grown to saturation in minimal glycerol medium, mixed with a 10-fold excess of scavenger cells, and plated on minimal lactose plates. The plates are incubated for five days and the newly arising colonies are scored each day after the second day. During this period, Lac+ colonies appear at a constant rate, but after five days the rate typically accelerates. This acceleration is due to: (1) growth of Lac- cells on nutrients excreted by early arising colonies (crossfeeding), and possibly, on the products of lactose breakdown; and (2) an increasing number phenotypically Lac+ colonies that are due to amplification of the lac region (see below).

Phenomenology of adaptive mutation

The extensive study of Lac+ adaptive mutation in FC40 has produced the following observations:

During growth under non-selective conditions, the reversion rate to Lac+ is about one per 109 cells per generation. When cells are under lactose selection, the mutation rate is 20-50 Lac+ revertants per 108 cells per day (43, 77).

With lactose as the only carbon source, adaptive mutations to Lac+ occur in liquid cultures at about the same rate as on solid plates (77). Thus, in contrast to the MAC phenotype described above, Lac+ reversion does not require a structured environment (although in liquid medium, cells can settle to the bottom of the culture vessel.)

Lac+ reversion does not occur when FC40 is incubated in the absence of any carbon source. However, upon addition of lactose, the reversion rate to Lac+ follows the normal kinetics (43, 77). Thus, starvation alone is not sufficient for adaptive mutation. Because the lac allele is somewhat leaky, it appears that some energy is required for adaptive mutations to occur, most likely to allow a small amount of DNA synthesis (see below).

The reversion rate to Lac+ is constant for about five days; during this time the number of Lac- cells on the plate is stable (43, 77).

During lactose selection Lac- cells accumulate non-selected mutations, disproving the hypothesis that mutations to Lac+ are “directed” by the selective pressure (41, 76, 77, 183). The rate of accumulation of non-selected mutations is higher on the episome than on the chromosome (41, 76, 77), possibly due to more frequent episomal replication and recombination.

The accumulation of non-selected mutations is 20- to 100- fold higher in Lac+ adaptive revertants than in the Lac- population (200, 253). Upon re-testing, Lac+ revertants with non-selected mutations do not have increased mutation rates, i.e. they are not genetic mutators. Thus, at least some cells exhibit a transient hypermutator phenotype while under lactose selection (discussed below).

The unreverted lac allele can amplify during lactose selection, producing phenotypically Lac+ colonies. During the five days of a normal adaptive mutation experiment, only about 2% of the Lac+ colonies consist of cells with lac- amplifications (77, 81); however, after ten days of incubation on lactose plates, up to 60% of the Lac+ colonies are due to cells with amplifications of the lac- allele (108, 186). One model of adaptive Lac+ mutation postulates that amplification is a precursor to true Lac+ reversion (see below).

Genetic requirements of adaptive mutation

Extensive genetic analysis has led to a significant, although not complete, understanding of the mechanism of Lac+ adaptive mutation in strain FC40. The genetic requirements described here and summarized in Table 2 demonstrate that adaptive mutation is a distinct and genetically independent process from growth-dependent mutation.

Table 2.

Genetic characteristics of adaptive mutation in FC40

| Gene | Gene product | Inducing stress response | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genes Required for Adaptive Mutation | |||

| recA+ | DNA recombinase | SOS | (43, 74) |

| recBC+ | DNA double-strand end exonuclease | Extracytoplasmic stressa | (82, 106, 196) |

| ruvAB+ and ruvC+ | Holiday-junction resolvase | SOS | (86, 107) |

| priA+ | Replication-restart primosome | None known | (79) |

| nusA | Transcription factor | Cold-shock | (52, 249) |

| Genes Required for the Maximum Rate of Adaptive Mutation | |||

| recF+ | DNA single-strand and double-strand binding | SOS | (79, 162) |

| dinB+ | Error-prone DNA Pol IV | SOS, general stress | (72, 163) |

| Conjugal functions | Conjugal replication and transfer | Growth phase | (84, 85, 90, 189) |

| rpoS+ | Transcription specificity factor | General stress | (145, 153) |

| rpoE | Transcription specificity factor | Extracytoplasmic stress | (93) |

| groE+ | Protein chaperone | Heat-shock | (146) |

| ppk+ | Polyphosphate Kinase | Nutritional deprivation | (238) |

| hupA, hupB | Histone-like protein HU | Growth phase, nutrient limitation, cold-shock | (260) |

| Defects that Enhance Adaptive Mutation | |||

| recG | Holiday-junction resolvase; helicase | SOS | (86, 107) |

| polA1 | DNA polymerase I | None known | (79) |

| recD | 5’ to 3’ helicase subunit of RecBCD | Extracytoplasmic stressa | (82, 106) |

| mutS, mutL | Mismatch repair | General Stress | (80, 83, 154, 204) |

| polB | DNA Pol II | SOS | (68) |

The recB and recD genes are in an operon that is regulated by RpoE, the extracytoplasmic stress sigma factor (82, 106, 196). The recC gene is not in the same operon and is not known to be regulated by RpoE. Thus, it is not clear if extracytoplasmic stress increases the levels of active RecBC or RecBCD enzyme.

1. Types of mutations

One of the most important features that differentiates adaptive mutation from growth-dependent mutation is the type of mutation that occurs. Because the activity of the lacI region of the lacI-lacZ fusion protein is irrelevant, any mutation that restores the reading frame within a 130 base-pair target will revert the Φ(lacI33-lacZ) allele. In growing cells, mutation to Lac+ can occur by a number of events that restore the reading frame, most commonly duplications, deletions, and large frameshifts (83, 204). In contrast, adaptive Lac+ mutations are almost exclusively -1 base pair frameshifts in runs of G:C base pairs. Runs of iterated base pairs are hotspots for frameshift mutations because during DNA replication, the 3′ terminus of the growing strand can slip backwards forming a normal base pair with another complementary base in the iterated sequence (237). Frameshifts are normally repaired by MMR in E. coli, which led to the hypothesis that the shift in the spectrum of mutations during adaptive mutation was due to a decline in MMR (83, 154, 204). And, indeed, two MMR proteins do decline in nutritionally deprived cells (105, 254). However, the MMR activity that remains is sufficient to correct 99% of the errors that produce Lac+ adaptive mutations (75). A better-supported hypothesis it that the mutational shift is due to increased activity of DNA Pol IV (see below).

2. Dependence on the F′ episome

Maximum adaptive mutation in FC40 requires that the lac allele is carried on the episome. When the same allele is in its normal position on the chromosome, the rate of adaptive mutation falls 100-fold (84, 189) and this low rate of reversion does not require the recombination functions that are required for adaptive mutation on the episome (84, 90). The maximal level of adaptive mutation on the episome also requires the expression of the F conjugal functions (the tra operon); however, actual conjugation is not required (84). In the absence of conjugal functions, adaptive mutation falls 10-fold, but recombination functions are still required (84). Several models of adaptive mutation predict that the required conjugal factor is TraI, the enzyme that nicks the conjugal origin to initiate conjugal DNA replication (84, 90, 140, 185, 198, 202). However, selective inactivation of several tra genes, including traI, induce the same 10-fold reduction in adaptive mutation (84, 90). This is probably because conjugation requires a large multi-protein complex and inactivation of any one gene may disrupt the entire machine (144).

3.Dependence on DNA polymerases

Loss of DNA Pol IV reduces adaptive mutation 50% to 80% (72, 163). E. coli’s other error-prone DNA polymerase, Pol V, makes little or no contribution (43, 162), probably because Pol V does not readily produce the frameshifts that revert the Lac- allele in FC40. The role of E. coli’s third inducible DNA polymerase, Pol II (polB), is not so simple. Pol II is active under the conditions used to measure adaptive mutation, but, because of its high fidelity, it produces few Lac+ mutants unless its proofreading function is inactivated (68, 81). The residual Pol IV-independent Lac+ adaptive mutations seen in a dinB mutant strain are reduced about 20 to 50% if Pol II is also missing (72, 109). However, if only Pol II is missing, the rate of adaptive mutation increases about 3-fold and all of these extra mutations are due to Pol IV (68, 72, 109). Thus, Pol II limits the mutagenic potential of Pol IV during lactose selection, possibly by competing with it for substrates or other shared factors (such as access to the β sliding clamp). In addition, polB mutant cells overproduce Pol IV, most likely because loss of Pol II results in partial induction of the SOS response (145) (although this interpretation is disputed; see reference 109). Interesting, whether or not the other polymerases are present, Lac+ adaptive mutations are reduced by the presence of the dnaE915 allele, which encodes an antimutator version of the polymerase subunit of Pol III. This result suggests that the DnaE915-containing Pol III is an antimutator because it limits the access of less accurate polymerases to the DNA (72, 109).

As mentioned above, FC40 and other P90C-derived strains carrying the F′128 episome have copies of dinB on the chromosome and on the episome. For unknown reasons, expression of dinB, as well as other genes, is higher on the episome, so that the amount of Pol IV in such F′ cells can be as much as 4-fold greater that in F- cells (124). This is clearly a factor contributing to FC40’s high rate of adaptive mutation (see below).

4.Influence of specific stress responses

As summarized in Table 1, five separate global stress responses impact the levels or activities of Pol IV and, consequently, also impact adaptive mutation. However, with the possible exception of the SOS response (89), it is unlikely that an effect on Pol IV is the only way these stress responses affect adaptive mutation. As discussed above, both loss of the general stress response sigma factor, RpoS (145, 153), and reduction in the levels of heat shock chaperone GroE (146), reduce adaptive Lac+ reversion about 10-fold. Much of this decrease is due to reduced levels of Pol IV, but in each case there is an additional Pol IV-independent effect (145, 146, 153). Interestingly, the Pol IV-independent effect of GroE is only seen a recG mutant strain (146). Likewise, Ppk, the enzyme that makes polyP, is required for maximal Pol IV activity, but Ppk also makes a small Pol IV-independent contribution to adaptive mutation (238). Thus, these stress responses have more complex roles in adaptive mutation than simple Pol IV regulation.

5.DNA repair and recombination functions

Recombination functions

The genes and their products that have been demonstrated to influence adaptive mutation are listed in Table 2. Adaptive mutation in FC40 depends on DNA repair and recombination pathways, indicating that, although not dividing, starved cells are not inert for DNA metabolism. In the absence of the RecA recombinase and the RecBCD end-processing complex, adaptive mutation in FC40 is nearly eliminated (43, 106). Thus, adaptive mutation requires the recombination pathway that repairs DNA double strand breaks. In addition, the RuvABC Holliday junction-processing machine is required (86, 107). In the absence of the RecG, a Holliday junction-processing helicase, adaptive mutation increases up to 100-fold (86, 107), and the extra mutations are due to Pol IV (145). Cells lacking RecG are partially induced for the SOS response (152, 160) and have 3- to 4-fold more Pol IV than wild-type cells (145). The helicase activity of RecG may also have a direct role in adaptive mutation, which is normally obscured by the effect of excess Pol IV in recG mutant cells (see below).

That a 3- to 4-fold increase in Pol IV could produce a 100-fold increase in mutation rate in a recG mutant requires some explanation. One possibility is that the extra DNA polymerase errors produced by Pol IV saturate the capacity of the MMR system, and so more mismatches are uncorrected and become mutations. And, indeed, the extra Lac+ mutations in a recG mutant strain are relatively insensitive to loss of MMR but are extraordinarily sensitive to overproduction of MMR proteins (86). A second, nonexclusive possibility is that DNA Pol II normally may compete with and limit the mutagenic activity of Pol IV (72). Both Pol II and Pol IV are induced as part of the SOS response, but the level of Pol IV induction, at least after UV irradiation, is about 4-fold higher than that of Pol II (54). Thus, the SOS induction in a recG mutant strain may allow Pol IV to out-compete Pol II. This last hypothesis could also apply to other factors that limit Pol IV’s mutagenic activity.

Loss of the RecD subunit of RecBCD eliminates the nuclease but not the helicase activity of the complex. FC40 recD mutant strains have a 10- to 30-fold increase in adaptive mutation (106). recD mutant strains are hyper-recombinogenic and have greatly elevated plasmid copy numbers (22, 110, 155, 197, 223). The F′ episome is not immune to this effect and its copy number steadily increased when the recD mutant derivative of FC40 was incubated on lactose (82). The resulting higher number of copies of the leaky Φ(lacI33-lacZ) allele resulted in sufficient β-galactosidase to allow the Lac- cells to weakly grow on the lactose medium and produce increasing numbers of Lac+ revertants. Because the rate of Lac+ reversion was driven by cell proliferation and increasing numbers of the lac mutational target, in this special case the appearance of new Lac+ mutants increased exponentially, not linearly as observed when the cells are not dividing (82). The ability to differentiate an exponential increase from a linear increase in the numbers of Lac+ mutants in these different genetic backgrounds supports the conclusion that normal Lac+ adaptive reversion is, in fact, constant with time.

Mismatch repair

MMR monitors and repairs the DNA polymerase errors that lead to adaptive Lac+ revertants. Adaptive mutation increases 100-fold when MMR is inactivated, (80) or when the strand discrimination ability of MMR is thwarted by overexpressing the Dam methylase (86). Adaptive mutation decreases when MMR proteins (particularly MutS and MutL, or both in combination) are overexpressed (75, 81, 105). However, overproduction of MMR proteins also decreases the mutation rate in growing cells, which implies that MMR capacity is limited both when cells are growing and when they are starved (75, 81) (although the implications of these results are disputed; see references 75, 104). Additionally, loss of mismatch repair has no effect on the frequency of non-selected mutations in Lac+ cells, suggesting that mismatch repair is inactive in hypermutating cells (200) (see below).

HU

The small histone-like protein HU is required for maximum adaptive mutation (260). HU is involved in a number of recombination and repair pathways and is regulated as part of several stress responses (see above and Table 2). In E. coli, HU consists of two closely related subunits: α and β, and exists in the cell as three forms: the two homodimers and the heterodimer. HUα2 is prevalent during exponential phase but HUαβ becomes more prevalent in stationary phase (50). The absence of either subunit, while having little effect on survival, decreases adaptive mutation about 70%, indicating that the heterodimer is required for maximum levels of adaptive mutation (260). This effect has both Pol IV-dependent and Pol IV-independent components and is independent of the sigma factor, RpoS, which HU is known to regulate. However, loss of the heterodimer has no effect in a recG mutant strain. One hypothesis to explain this result is that the heterodimer, but not either homodimer, helps to channel recombination intermediates for resolution via a RuvABC-dependent mutagenic pathway instead of a RecG-dependent non-mutagenic pathway (260).

As mentioned above, when E. coli is subjected to cold shock, expression of HUβ is up-regulated and expression of HUα is blocked, resulting in increased levels of HUαβ2 (92). This effect, plus the intrinsic instability of DNA Pol IV at normal temperatures and its stabilization by GroE (see above), as well as the increased levels of NusA at low temperatures (see above), may account for the observed increase in adaptive mutation at lower temperatures (52, 79).

NusA

Maximum levels of adaptive mutation require the activity of the transcription factor NusA (52). As mentioned above, NusA interacts with Pol IV physically, and overexpression of either Pol IV or Pol V suppresses the temperature sensitivity of a nusA mutant allele (51). These results have led to the hypothesis that NusA recruites Pol IV to rescue RNA polymerase stalled at a gap in the transcribed strand opposite a lesion on the non-transcribed strand (51). This process, called “transcription–coupled translesion synthesis”, could be the source of adaptive mutations (52). However, an alternative explanation is that loss of NusA activity simply reduces the level of transcription of the genes that encode proteins required for adaptive mutation, including lacZ itself (207).

Models for adaptive mutation

Two main models for Lac+ adaptive mutation in FC40 have emerged. The first, recombination-dependent mutation (RDM), postulates that Lac+ adaptive mutations occur in non-dividing cells (78). The second model, amplification-dependent mutation (ADM), postulates that Lac+ mutations occur in a small sub-population of cells that are proliferating during incubation on lactose (210). While these models are not entirely mutually exclusive, their validities are highly disputed among researchers (see references 73, 203, 208).

Recombination-dependent model (see Fig. 3 and reference 78)

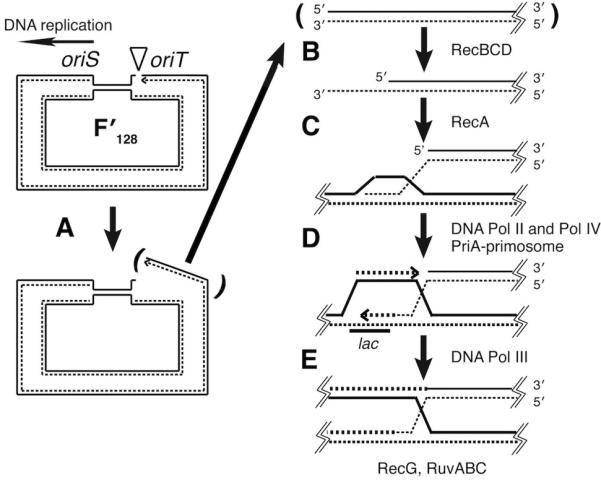

Figure 3.

The recombination-dependent model for adaptive mutation to Lac+. A replication fork initiated at the vegetative origin, oriS, on F′128 collapses when it arrives at a nick at the conjugal origin, oriT. A. Collapse of the replication fork creates a double-strand end. B. RecBCD processes the double-strand end to form a 3′ single-strand end. C. RecA catalyzes the invasion of the 3′ single-strand end into a homologous region of duplex DNA. D. PriA-dependent DNA synthesis is initiated from the invading 3′′end by DNA Pol IV or Pol II and a Holliday junction is formed. E. A normal replication fork is re-established with DNA Pol III. The Holliday junction is processed and resolved by RuvABC. Adaptive Lac+ reversions occur when error-prone DNA synthesis extends into the lac region on the episome and introduces a -1 frameshift.

The F plasmid tra functions are required for maximum levels of adaptive mutation. Even when cells are not conjugating, the TraI nickase nicks at the episomal conjugal origin, oriT (87). According to the RDM model, this persistent nick initiates the recombination pathway leading to adaptive mutation. While the episome copy-number is stable during lactose selection (82), the low level of lactose metabolism in Lac- cells permits the occasional firing of one of the episome’s vegetative origins of replication. If the resulting replication fork encounters the persistent nick at the conjugal origin, a DNA double-strand break results that initiates recombinational double strand break repair. The RecBCD complex processes the double strand break to generate a 3′ single-strand overhang, which the RecA recombinase uses to invade the homologous duplex DNA, either on the same episome or on another copy of the episome. The 3′ endogenous of this invading strand serves as the primer for PriA-mediated, origin-independent, replication to restart the failed replication fork (for a review, see reference 161).

The RDM postulates that Lac+ mutations arise as a result of the DNA synthesis initiated during this replication restart. Pol II and Pol IV compete for the 3′ terminus (72, 114). Pol II is an accurate polymerase, so if it gains access to the 3′ terminus, few Lac+ mutations result. But if error-prone Pol IV gains access, strand slippage followed by extension results in the Lac+ frameshift mutations. A possible alternative mechanism is that Pol II, or Pol III, makes a slip and that Pol IV is recruited to extend the misaligned primer-template, a known activity of Pol IV (127). Nonselected mutations, either frameshifts or base substitutions, occur on the episome by the same mechanism. The recombination step results in a Holliday junction, which is translocated and resolved by RuvABC or RecG.

According to the RDM model, the high rate of Lac+ reversion on the episome is due to its tendency to initiate replication, the frequency of double-strand breaks, and their recombinational repair. The requirement for Pol IV connects RDM to nutritional stress. Since the mutation rate is dependent on the amount of Pol IV in the cell, stress induced induction or activation of Pol IV increases the adaptive mutation rate to Lac+.

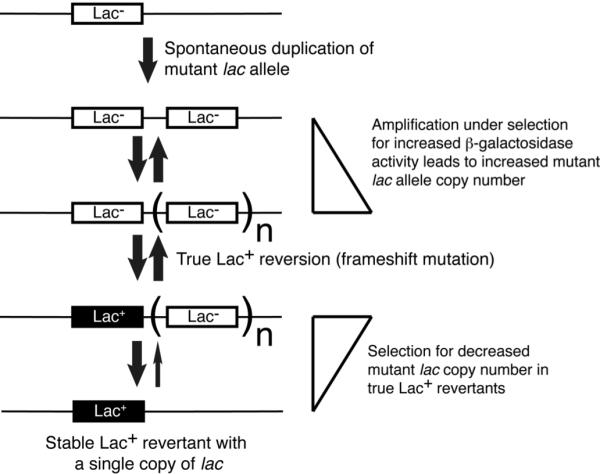

Amplification-dependent model (Fig. 4 and reference 210)

Figure 4.