Abstract

ATM-Chk2 network is critical for genomic stability, and its deregulation may influence breast cancer pathogenesis. We investigated ATM and Chk2 protein levels in two cohorts [cohort 1 (n = 1650) and cohort 2 (n = 252)]. ATM and Chk2 mRNA expression was evaluated in the Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium cohort (n = 1950). Low nuclear ATM protein level was significantly associated with aggressive breast cancer including larger tumors, higher tumor grade, higher mitotic index, pleomorphism, tumor type, lymphovascular invasion, estrogen receptor (ER)−, PR −, AR −, triple-negative, and basal-like phenotypes (Ps < .05). Breast cancer 1, early onset negative, low XRCC1, low SMUG1, high FEN1, high MIB1, p53 mutants, low MDM2, low Bcl-2, low p21, low Bax, high CDK1, and low Chk2 were also more frequent in tumors with low nuclear ATM level (Ps < .05). Low ATM protein level was significantly associated with poor survival including in patients with ER-negative tumors who received adjuvant anthracycline or cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil–based adjuvant chemotherapy (Ps < .05). Low nuclear Chk2 protein was likely in ER −/PR −/AR −; HER-2 positive; breast cancer 1, early onset negative; low XRCC1; low SMUG1; low APE1; low polβ; low DNA-PKcs; low ATM; low Bcl-2; and low TOPO2A tumors (P < .05). In patients with ER + tumors who received endocrine therapy or ER-negative tumors who received chemotherapy, nuclear Chk2 levels did not significantly influence survival. In p53 mutant tumors, low ATM (P < .000001) or high Chk2 (P < .01) was associated with poor survival. When investigated together, low-ATM/high-Chk2 tumors have the worst survival (P = .0033). Our data suggest that ATM-Chk2 levels in sporadic breast cancer may have prognostic and predictive significance.

Introduction

Ataxia–telegiectasia mutated (ATM), a member of the PI3K-like protein kinases family of serine threonine kinases, is a key player in the maintenance of genomic integrity [1], [2], [3], [4]. ATM is activated and recruited to sites of double-strand breaks through the Mre11–Rad50–NBS1 complex. Activated ATM in turn phosphorylates a number of proteins involved in cellular homeostasis [1], [2], [3], [4]. A key substrate of ATM is Chk2 whose phosphorylation at Thr68 results in activation and in turn phosphorylation of a number of substrates such as p53, breast cancer 1, early onset (BRCA1), and others [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Proficient ATM-Chk2 signaling network is therefore essential for coordination of DNA repair, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis in response to DNA damage.

Accumulating evidence provides compelling evidence that germ-line mutations in ATM[10], [11], [12], [13] and Chk2[14] may result in a predisposition to several tumors including hereditary breast cancers. In addition, in sporadic tumors, emerging data also suggest a role for ATM and Chk2 somatic mutations in cancer development [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. However, whether such somatic mutations or deregulation of protein expression has clinicopathological, prognostic, and predictive significance in sporadic breast cancer has not been clearly defined. In the current study, we have comprehensively investigated ATM and Chk2 in large cohorts of early-stage breast cancers. The data presented here suggest that impaired ATM-Chk2 pathway may influence the development of aggressive phenotypes that are associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients.

Patients and Methods

The Reporting Recommendations for Tumour Marker Prognostic Studies criteria, recommended by McShane et al. [15], were followed throughout this study. This work was approved by the Nottingham Research Ethics Committee.

Cohort 1

This is a consecutive series of 1650 patients with primary invasive breast carcinomas who were diagnosed between 1986 and 1999 and entered into the Nottingham Tenovus Primary Breast Carcinoma series. This is a well-characterized series of patients with long-term follow-up that have been investigated in a wide range of biomarker studies [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes patient demographics, and supplementary treatment data 1 summarizes the various adjuvant treatment regimens received by patients in this group.

Cohort 2

An independent series of 252 estrogen receptor (ER)-α–negative invasive breast cancers diagnosed and managed at the Nottingham University Hospitals between 1999 and 2007 was also evaluated for ATM and Chk2 expression. All patients were primarily treated with surgery, followed by radiotherapy and anthracycline chemotherapy. The characteristics of this cohort are summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

Tissue Microarray (TMA) and Immunohistochemistry

TMAs were constructed and immunohistochemically profiled for ATM, Chk2, and other biological antibodies. The optimization and specificity of the antibodies used in the current study have been described in previous publications [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27] and listed in Supplementary Table S3. A set of slides was incubated for 18 hours at 4°C with the primary mouse monoclonal anti-ATM antibody, clone Y170 (Ab32420, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), at a dilution of 1:100. A further set of slides was incubated for 60 minutes with the primary rabbit polyclonal anti-Chk2 antibody (Ab47433, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at a dilution of 1:100. To evaluate the use of TMAs for immunophenotyping, full-face sections of 40 cases were stained and protein expression levels of ATM and Chk2 were compared. The concordance between TMAs and full-face sections was excellent (k = 0.8). Positive and negative (by omission of the primary antibody and IgG-matched serum) controls were included in each run. Whole field inspection of the core was scored, and intensities of nuclear staining were grouped as follows: 0 = no staining, 1 = weak staining, 2 = moderate staining, 3 = strong staining. The percentage of each category was estimated (0-100%). H-score (range 0-300) was calculated by multiplying intensity of staining and percentage staining. X-tile (version 3.6.1; Yale University, New Haven, CT) was used to identify a cutoff for ATM protein expression. The percentage of positive cells was used, with a cut off of < 25% cells being classed as low and ≥ 25% as high for nuclear ATM protein level. For Chk2 nuclear expression level, H-score cutoff was the median, and H-score of ≥ 100 was considered high for nuclear Chk2 expression. Not all cores within the TMA were suitable for immunohistochemistry analysis as some cores were missing or lacked tumor. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression was assessed according to the new American Society of Clinical Oncology/The College of American Pathologists guidelines using chromogenic in situ hybridization [28].

Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (SPSS, version 17, Chicago, IL). Where appropriate, Pearson’s Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, χ2 for trend, Student’s t and analyses of variance one-way tests were performed using SPSS software (SPSS, version 17, Chicago, IL). Cumulative survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences between survival rates were tested for significance using the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis for survival was performed using the Cox hazard model. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using standard log-log plots. Each variable was assessed in univariate analysis as a continuous and categorical variable, and the two models were compared using an appropriate likelihood ratio test. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated for each variable. All tests were two-sided with a 95% CI. P values for each test were adjusted with Benjamini and Hochberg multiple P value adjustment, and an adjusted P value of < .05 was considered significant.

Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) Cohort for mRNA Expression

The mRNA expression was performed in the METABRIC cohort. The METABRIC study protocol, detailing the molecular profiling methodology in a cohort of 1980 breast cancer samples, is described by Curtis et al. [29]. Patient demographics are summarized in Supplementary Table S4 of supporting information. ER-positive and/or lymph node–negative patients did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. ER-negative and/or lymph node–positive patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. RNA was extracted from fresh frozen tumors and subjected to transcriptional profiling on the Illumina HT-12 v3 platform. The data were preprocessed and normalized as described previously [29], and gene expression was investigated in this data set. X-tile (version 3.6.1; Yale University, New Haven, CT) was used to identify a cutoff in gene expression values to divide the population in to high/low subgroups before analysis. Cumulative survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Breast Cancer Clines, Tissue Culture, and Western Blot Analysis

Supplementary Table S5 summarizes the molecular profile of breast cancer cells evaluated for ATM and Chk2 protein levels. MCF-7 (ER +/PR +/HER2 −, BRCA1 proficient, PTEN proficient), MDA-MB-231 (ER −/PR −/HER2 −, BRCA1 proficient, PTEN proficient), BT-549 (ER −/PR −/HER2 −, BRCA1 proficient, PTEN deficient), MDA-MB-468 (ER −/PR −/HER2 −, BRCA1 proficient, PTEN deficient), and MDA-MB-436 (ER −/PR −/HER2 −, BRCA1 deficient, PTEN deficient) were purchased from ATCC and were grown in RPMI (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231) or Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (BT-549, MDA-MB-468, and MDA-MB-436) with the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. ATM-deficient HeLa SilenciX® cells and control ATM proficient HeLa SilenciX® cells were purchased from Tebu-Bio (www.tebu-bio.com). SilenciX cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (with l-glutamine 580 mg/l, 4500 mg/l D19 glucose, with 110 mg/l sodium pyruvate) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 125 μg/ml Hygromycin B. Previously well-characterized CH lung fibroblast cells; V79 (ATM wild type), V-E5 (ATM deficient) were grown in Ham’s F-10 media (PAA, UK) [supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (PAA,UK) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin]. Cell lysates were prepared. and Western blot analysis was performed. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at room temperature [Chk2 1:250 dilution, ATM 1:1500 and β-actin 1:10,000 dilution (Abcam)]. Infrared dye-labeled secondary antibodies (Li-Cor) (IRDye 800CW Mouse Anti-Rabbit IgG and IRDye 680CW Rabbit Anti-Mouse IgG) were incubated at a dilution of 1:10,000 for 1 hour. Membranes were scanned with a Li-Cor Odyssey machine (700 and 800 nm) to determine protein expression. ATM or Chk2 expression was quantified after normalizing with β-actin.

Results

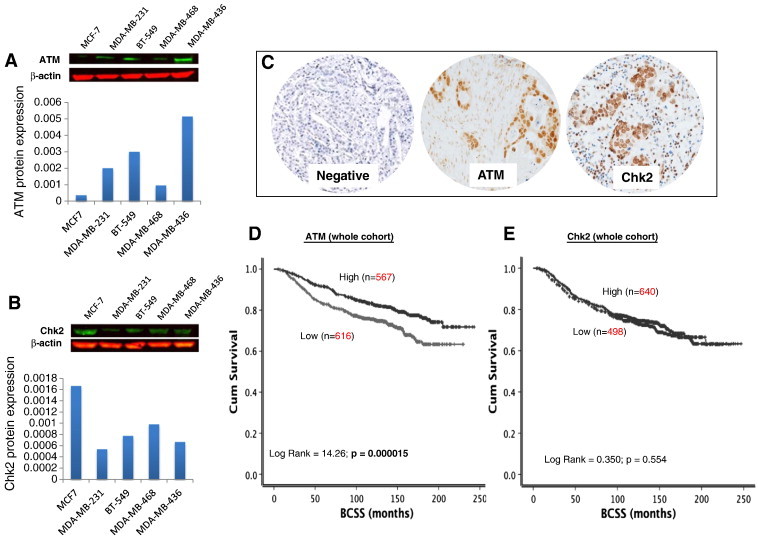

We initially profiled a panel of breast cancer cell lines for ATM and Chk2 protein expression. A wide spectrum of expression of ATM was evident across breast cancer cell lines (Figure 1A). MCF-7 has the lowest expression, whereas MDA-MB-436 has the highest ATM expression. MDA-MB-231, BT-549, and MDA-MB-468 exhibit reduced expression of ATM compared to MDA-MB-436. For Chk2 (Figure 1B), MCF7 has the highest Chk2 expression compared to MDA-MB-231, which has the lowest. BT-549, MDA-MB-436, and MDA-MB-468 have low Chk2 expression compared to MCF-7 cells. Together, the data reveal differential expression of ATM and Chk2 proteins in different breast cancer cell lines. To further evaluate the specificity of ATM antibody used in the current study, we performed Western blots in cell lysates from Chinese hamster lung fibroblasts [ATM deficient (V-E5 cells) and ATM proficient (V-79 cells)] and HeLa cells [ATM-deficient SilenciX cells where ATM has been knocked down by stable shRNA and ATM proficient control cells]. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, ATM-proficient cells have robust ATM expression, and in ATM-deficient cells, there is no/minimal ATM expression. We then conducted immunohistochemical investigation of ATM and Chk2 expression in human breast tumor samples.

Figure 1.

(A) Western blot of ATM expression in breast cancer cell lines. (B) Western blot of Chk2 expression in breast cancer cell lines. (C) Microphotograph of ATM and Chk2 negative and positive breast cancer tissue. (D) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS and ATM level. (E) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS and Chk2 level.

ATM Levels and Breast Cancer

A total of 1183 tumors were suitable for ATM analysis. High nuclear ATM level was seen in 567/1183 (48%) tumors compared to 616/1183 (52%) tumors that had low nuclear ATM level (Figure 1C) (Table 1). Low nuclear ATM level was associated with larger tumors (P = .027), higher tumor grade (P < .001), higher mitotic index (P < .001), pleomorphism (P < .001), tumor type (P < .001), and lymphovascular invasion (P = .001) (Table 1). Triple-negative (P < .001) and basal-like phenotype (P = .046) breast cancers were more commonly low nuclear ATM tumors. ER −, PR −, and AR − were also more common in low–nuclear ATM tumors (P < .001). BRCA1 negative, low XRCC1, low SMUG1, and low FEN1 were also more likely associated with low ATM level in tumors (P < .05). In addition, high MIB1, p53 mutants, low MDM2, Bcl-2 mutants, low p21, low Bax, high CDK1, and low Chk2 were likely in tumors with low nuclear ATM levels (P < .05).

Table 1.

ATM Protein Level in Sporadic Breast Cancer

| Variable | ATM Protein Expression |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low N (%) | High N (%) | ||

| A) Pathological parameters | |||

| Tumor size | .027 | ||

| < 1 cm | 87 (14.1) | 76 (13.4) | |

| > 1-2 cm | 295 (47.9) | 319 (56.3) | |

| > 2-5 cm | 218 (35.4) | 161 (28.4) | |

| > 5 cm | 16 (2.6) | 11 (1.9) | |

| Tumor stage | .273 | ||

| 1 | 399 (63.2) | 386 (67.5) | |

| 2 | 179 (28.4) | 147 (25.7) | |

| 3 | 53 (8.4) | 39 (6.8) | |

| Tumor grade*⁎ | 1.0 × 10− 6 | ||

| G1 | 75 (12.2) | 142 (25.0) | |

| G2 | 202 (32.8) | 190 (33.5) | |

| G3 | 339 (55.0) | 235 (41.4) | |

| Mitotic index | 3.0 × 10− 6 | ||

| M1 (low; mitoses < 10) | 190 (30.9) | 253 (44.6) | |

| M2 (medium; mitoses 10-18) | 116 (18.9) | 100 (17.6) | |

| M3 (high; mitosis > 18) | 308 (50.2) | 214 (37.7) | |

| Tubule formation | 1.1 × 10− 5 | ||

| 1 (> 75% of definite tubule) | 37 (6.0) | 42 (7.4) | |

| 2 (10%-75% definite tubule) | 166 (27.0) | 222 (39.2) | |

| 3 (< 10% definite tubule) | 411 (66.9) | 303 (53.4) | |

| Pleomorphism | 2.4 × 10− 5 | ||

| 1 (small-regular uniform) | 15 (2.4) | 26 (4.6) | |

| 2 (moderate variation) | 213 (34.7) | 258 (45.5) | |

| 3 (marked variation) | 386 (62.9) | 283 (49.9) | |

| Tumor type | 1.0 × 10− 4 | ||

| IDC-NST | 337 (64.7) | 271 (53.7) | |

| Tubular carcinoma | 79 (15.2) | 133 (26.3) | |

| Medullary carcinoma | 20 (3.8) | 11 (2.2) | |

| ILC | 48 (9.2) | 50 (9.9) | |

| Others | 37 (7.1) | 40 (7.9) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | .001 | ||

| No | 388 (65.2) | 417 (74.5) | |

| Yes | 207 (34.8) | 143 (25.5) | |

| B) Aggressive phenotype | |||

| Her2 overexpression | .389 | ||

| No | 506 (87.5) | 487 (89.2) | |

| Yes | 72 (12.5) | 59 (10.8) | |

| Triple-negative phenotype | 2.2x10− 4 | ||

| No | 459 (76.8) | 476 (85.3) | |

| Yes | 139 (23.2) | 82 (14.7) | |

| Basal-like phenotype | .046 | ||

| No | 494 (85.0) | 487 (89.0) | |

| Yes | 87 (15.0) | 60 (11.0) | |

| CK6 | .301 | ||

| Negative | 424 (83.3) | 404 (80.8) | |

| Positive | 87 (16.7) | 96 (19.2) | |

| CK14 | .062 | ||

| Negative | 451 (88.8) | 424 (84.8) | |

| Positive | 87 (11.2) | 76 (15.2) | |

| CK18 | 1.1 × 10− 4 | ||

| Negative | 73 (14.6) | 31 (6.8) | |

| Positive | 428 (85.4) | 424 (93.2) | |

| CK19 | 1.2 × 10− 4 | ||

| Negative | 46 (9.0) | 16 (3.2) | |

| Positive | 463 (91.0) | 480 (96.8) | |

| C) Hormone receptors | |||

| ER | 1.9 × 10− 5 | ||

| Negative | 207 (33.4) | 126 (22.3) | |

| Positive | 412 (66.6) | 440 (77.7) | |

| PgR | 7.5 × 10− 5 | ||

| Negative | 271 (48.1) | 190 (36.3) | |

| Positive | 292 (51.9) | 334 (63.7) | |

| AR | 4.6 × 10− 5 | ||

| Negative | 212 (43.5) | 144 (30.8) | |

| Positive | 275 (56.5) | 324 (69.2) | |

| D) DNA repair | |||

| BRCA1 | 3.0 × 10− 6 | ||

| Absent | 110 (24.8) | 50 (12.3) | |

| Normal | 333 (75.2) | 358 (87.7) | |

| XRCC1 | .002 | ||

| Low | 81 (19.4) | 43 (11.4) | |

| High | 336 (80.6) | 334 (88.6) | |

| FEN1 | .018 | ||

| Low | 301 (75.8) | 241 (68.1) | |

| High | 96 (24.2) | 113 (31.9) | |

| SMUG1 | 2.0 × 10− 6 | ||

| Low | 173 (47.1) | 97 (29.4) | |

| High | 194 (52.9) | 233 (70.6) | |

| APE1 | .152 | ||

| Low | 215 (52.7) | 173 (47.5) | |

| High | 193 (47.3) | 191 (52.5) | |

| PolB | .607 | ||

| Low | 178 (40.1) | 148 (38.3) | |

| High | 266 (59.5) | 238 (61.7) | |

| DNA-PKcs | .946 | ||

| Low | 138 (35.9) | 116 (35.7) | |

| High | 246 (64.1) | 209 (64.3) | |

| E) Cell cycle/apoptosis regulators | |||

| P16 | .151 | ||

| Low | 358 (83.4) | 354 (87.0) | |

| High | 71 (16.6) | 53 (13.0) | |

| P21 | .002 | ||

| Low | 274 (63.7) | 235 (53.5) | |

| High | 156 (36.3) | 204 (46.5) | |

| MIB1 | .001 | ||

| Low | 222 (44.7) | 266 (55.8) | |

| High | 275 (55.3) | 211 (44.2) | |

| P53 | .034 | ||

| Low expression | 379 (56.7) | 393 (82.2) | |

| High expression | 115 (23.3) | 85 (17.8) | |

| Bcl-2 | .002 | ||

| Negative | 209 (39.6) | 153 (30.4) | |

| Positive | 319 (60.4) | 351 (69.6) | |

| TOP2A | .238 | ||

| Low | 195 (46.9) | 161 (42.7) | |

| Overexpression | 221 (53.1) | 216 (57.3) | |

| CHK2 | .009 | ||

| Low | 329 (92.2) | 255 (85.9) | |

| High | 28 (7.8) | 42 (14.1) | |

| Bax | .010 | ||

| Low | 252 (72.2) | 189 (62.8) | |

| High | 97 (27.8) | 111 (37.2) | |

| CDK1 | .009 | ||

| Low | 204 (65.8) | 200 (75.8) | |

| High | 106 (34.2) | 64 (24.2) | |

| MDM2 | 1.0 × 10− 6 | ||

| Low | 353 (81.3) | 280 (63.3) | |

| Overexpression | 81 (18.7) | 162 (36.7) | |

Bold = statistically significant; PgR: progesterone receptor; CK: cytokeratin; Basal-like: ER −, HER2, and positive expression of either CK5/6, CK14, or EGFR; Triple negative: ER −/PgR −/HER2 −.

Grade as defined by Nottingham Grading System.

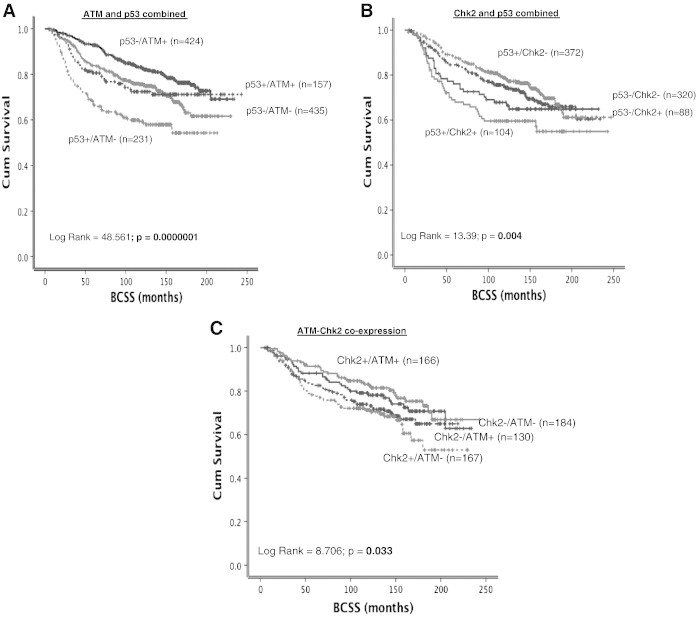

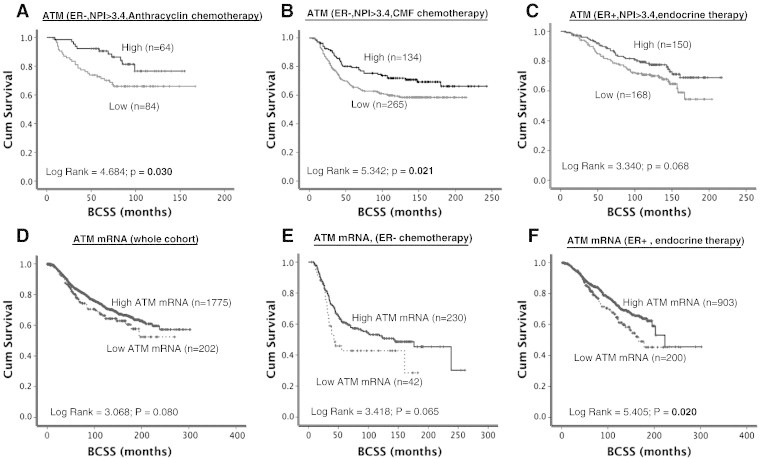

Low ATM level was associated with worse breast cancer–specific survival (BCSS) in patients (P < .0001) (Figure 1D). As ATM mediated activation and stabilization of p53 are essential for genomic stability and cell cycle response, we conducted exploratory analysis in p53 mutant and proficient tumors. p53 mutants with low ATM levels have the worst survival compared to p53 wild-type tumors with high ATM levels (P < .0001) (Figure 2A). Tumors that are p53 mutants with high ATM levels and p53 wild type with low ATM levels have intermediate prognosis. We then investigated in ER + and ER − subgroups. ER + tumors were from cohort 1. For ER-negative tumors, we combined tumors from cohort 1 and cohort 2 for the subgroup analysis. In high-risk (NPI > 3.4) ER-negative tumors that received no adjuvant chemotherapy, low ATM was associated with poor survival (P = .041) (Supplementary Figure S2A). In high-risk ER-negative tumors that received anthracycline (Figure 3A) or cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) adjuvant chemotherapy (Figure 3B), low ATM remains associated with poor survival (P = .030 and P = .021, respectively). In ER + tumors, ATM level did not significantly influence clinical outcomes (Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure S2B). At the mRNA level, low ATM was seen in 10% of tumors (202/1977). Although there was a trend, low ATM expression was not significantly associated with poor BCSS in the whole cohort (P = .080, Figure 3D) and in the ER − cohort that received chemotherapy (P = .065, Figure 3E). Interestingly, low ATM expression was significantly associated with poor BCSS in the ER + cohort that received endocrine therapy (P = .020, Figure 3F).

Figure 2.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS stratified based on p53 mutation status and ATM level. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS stratified based on p53 mutation status and Chk2 level. (C) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS stratified based on ATM and Chk2 coexpression.

Figure 3.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on ATM levels in ER − patients who received anthracycline chemotherapy. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on ATM levels in ER − patients who received CMF chemotherapy. (C) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on ATM levels in ER + patients who received endocrine therapy. (D) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on ATM mRNA expression in the whole cohort. (E) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on ATM mRNA expression in ER − patients who received chemotherapy. (F) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on ATM mRNA expression in ER + patients who received endocrine therapy.

Chk2 Levels and Breast Cancer

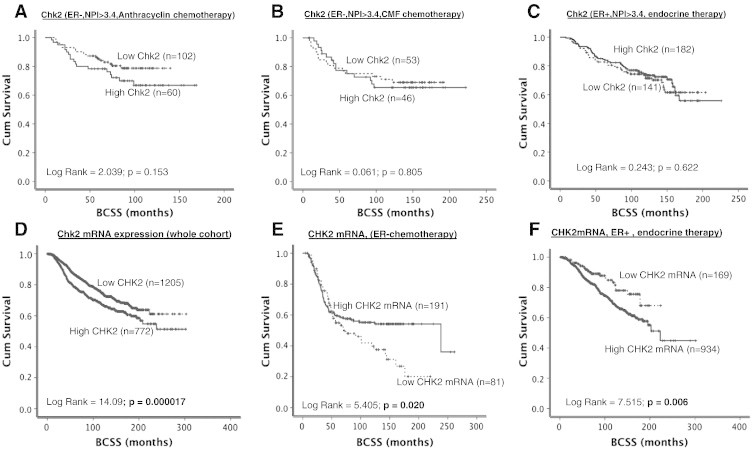

A total of 1138 tumors were suitable for Chk2 analysis. High nuclear Chk2 level was seen in 640/1138 (56%) tumors compared to 498/1138 (44%) tumors that had low nuclear Chk2 level (Figure 1C) (Table 2). Low nuclear Chk2 was likely in HER-2–overexpressing tumors. ER −/PR −/AR − tumors were also more likely in tumors with low nuclear Chk2 levels. BRCA1 negative, XRCC1 low, FEN1 low, SMUG1 low, APE1 low, polβ low, DNA-PKcs low, ATM low, Bcl-2 low, TOPO2A low, and MDM2 low tumors were more likely in tumors with low nuclear Chk2 levels (P < .05) (Table 2). In the whole cohort, there was no significant association with BCSS (Figure 1E). However, when stratified based on p53 mutation status, p53 mutants with high nuclear Chk2 appear to have poor outcome compared to p53 mutants with low nuclear Chk2 levels (P = .004) (Figure 2B). We also performed subgroup analysis based on ER status in tumors. In ER − tumors that received no adjuvant chemotherapy, high nuclear Chk2 was associated with poor survival (P = .047) (Supplementary Figure S2C). However, in ER + tumors that received no adjuvant endocrine therapy, low nuclear Chk2 was associated with poor survival (P = .014) (Supplementary Figure S2D). In patients with ER + tumors who received endocrine therapy or ER-negative tumors who received chemotherapy, nuclear Chk2 levels did not significantly influence clinical outcome (Figure 4A, B, and C). At the mRNA level, high Chk2 expression was significantly associated with poor BCSS in the whole cohort (P < .001, Figure 4D) and in the ER + cohort that received endocrine therapy (P = .006, Figure 4F). However, low Chk2 expression was significantly associated with poor BCSS in the ER − cohort that received chemotherapy (P = .020, Figure 4E).

Table 2.

Chk2 Protein Level in Sporadic Breast Cancers

| Variable | Chk2 Protein Expression |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low N (%) | High N (%) | ||

| A) Pathological parameters | |||

| Tumor size | .483 | ||

| < 1 cm | 43 (8.6) | 111 (10.1) | |

| > 1-2 cm | 250 (50.2) | 290 (48.3) | |

| > 2-5 cm | 190 (38.2) | 224 (37.5) | |

| > 5 cm | 15 (3.0) | 15 (2.5) | |

| Tumor stage | .441 | ||

| 1 | 302 (60.4) | 383 (64.2) | |

| 2 | 151 (30.2) | 163 (27.3) | |

| 3 | 47 (9.4) | 51 (8.5) | |

| Tumor grade*⁎ | .144 | ||

| G2 | 140 (28.1) | 192 (32.2) | |

| G3 | 294 (59.0) | 317 (53.1) | |

| Mitotic index | .241 | ||

| M1 (low; mitoses < 10) | 144 (29.0) | 188 (31.6) | |

| M2 (medium; mitoses 10-18) | 88 (17.7) | 120 (20.2) | |

| M3 (high; mitosis > 18) | 264 (53.2) | 286 (48.1) | |

| Tubule formation | .912 | ||

| 1 (> 75% of definite tubule) | 21 (4.2) | 23 (3.9) | |

| 2 (10%-75% definite tubule) | 153 (30.8) | 189 (31.8) | |

| 3 (< 10% definite tubule) | 322 (64.9) | 382 (64.3) | |

| Pleomorphism | .070 | ||

| 1 (small-regular uniform) | 11 (2.2) | 12 (2.0) | |

| 2 (moderate variation) | 151 (30.4) | 220 (37.1) | |

| 3 (marked variation) | 334 (67.3) | 361 (60.9) | |

| Tumor type | .235 | ||

| IDC-NST | 274 (62.7) | 325 (63.5) | |

| Tubular carcinoma | 77 (17.6) | 90 (17.6) | |

| Medullary carcinoma | 18 (4.1) | 9 (1.8) | |

| ILC | 30 (6.9) | 44 (8.6) | |

| Others | 38 (8.7) | 44 (8.6) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | .282 | ||

| No | 315 (64.3) | 397 (67.4) | |

| Yes | 175 (35.7) | 192 (32.6) | |

| B) Aggressive phenotype | |||

| Her2 overexpression | .017 | ||

| No | 410 (84.2) | 518 (89.2) | |

| Yes | 77 (15.8) | 63 (10.8) | |

| Triple-negative phenotype | .140 | ||

| No | 379 (78.0) | 475 (81.6) | |

| Yes | 107 (22.0) | 107 (18.4) | |

| Basal-like phenotype | .410 | ||

| No | 400 (85.5) | 492 (87.2) | |

| Yes | 68 (14.5) | 72 (12.8) | |

| CK6 | .970 | ||

| Negative | 353 (83.1) | 414 (83.0) | |

| Positive | 72 (16.9) | 85 (17.0) | |

| CK14 | .566 | ||

| Negative | 368 (86.6) | 434 (87.9) | |

| Positive | 57 (13.4) | 60 (12.1) | |

| CK18 | .271 | ||

| Negative | 49 (12.3) | 46 (10.0) | |

| Positive | 348 (87.7) | 415 (90.0) | |

| CK19 | .478 | ||

| Negative | 28 (6.7) | 39 (7.9) | |

| Positive | 392 (93.3) | 455 (92.1) | |

| C) Hormone receptors | |||

| ER | .008 | ||

| Negative | 163 (33.1) | 151 (25.7) | |

| Positive | 330 (66.9) | 437 (74.3) | |

| PgR | .006 | ||

| Negative | 232 (49.3) | 225 (40.7) | |

| Positive | 239 (50.7) | 328 (59.3) | |

| AR | .002 | ||

| Negative | 181 (45.5) | 165 (35.0) | |

| Positive | 217 (54.5) | 306 (65.0) | |

| D) DNA repair | |||

| BRCA1 | 2.1 × 10− 4 | ||

| Absent | 101 (27.7) | 69 (16.7) | |

| Normal | 263 (72.3) | 343 (83.3) | |

| XRCC1 | 2.2 × 10− 4 | ||

| Low | 86 (22.9) | 54 (12.9) | |

| High | 289 (77.1) | 364 (87.1) | |

| FEN1 | 2.1 × 10− 4 | ||

| Low | 287 (81.3) | 272 (69.6) | |

| High | 147 (18.7) | 119 (30.4) | |

| SMUG1 | .003 | ||

| Low | 155 (46.8) | 131 (35.6) | |

| High | 176 (53.2) | 237 (64.4) | |

| APE1 | 1.0 × 10− 6 | ||

| Low | 320 (68.7) | 220 (38.9) | |

| High | 146 (31.3) | 346 (61.1) | |

| PolB | 1.0 × 10− 6 | ||

| Low | 226 (48.9) | 173 (30.8) | |

| High | 236 (51.5) | 388 (69.2) | |

| ATM | .026 | ||

| Low | 188 (59.1) | 170 (50.4) | |

| High | 130 (40.9) | 167 (49.6) | |

| DNA-PKcs | 1.0 × 10− 6 | ||

| Low | 187 (45.2) | 134 (29.5) | |

| High | 226 (54.7) | 321 (70.5) | |

| E) Cell cycle/apoptosis regulators | |||

| P16 | .187 | ||

| Low | 294 (83.1) | 352 (86.5) | |

| High | 60 (16.9) | 55 (13.5) | |

| P21 | .192 | ||

| Low | 227 (61.5) | 238 (56.9) | |

| High | 142 (38.5) | 180 (43.1) | |

| MIB1 | .405 | ||

| Low | 164 (40.6) | 218 (43.3) | |

| High | 240 (59.4) | 285 (56.7) | |

| P53 | 0.856 | ||

| Low expression | 322 (78.5) | 373 (78.0) | |

| High expression | 88 (21.5) | 105 (22.0) | |

| Bcl-2 | .002 | ||

| Negative | 194 (43.3) | 176 (33.6) | |

| Positive | 254 (56.7) | 348 (66.4) | |

| TOP2A | 1.8 × 10− 5 | ||

| Low | 195 (53.7) | 166 (38.5) | |

| Overexpression | 168 (46.3) | 265 (61.5) | |

| Bax | .435 | ||

| Low | 200 (69.7) | 248 (72.5) | |

| High | 87 (30.3) | 94 (27.5) | |

| CDK1 | .547 | ||

| Low | 278 (69.8) | 292 (67.9) | |

| High | 120 (30.2) | 138 (32.1) | |

| MDM2 | .001 | ||

| Low | 279 (90.6) | 299 (81.7) | |

| Overexpression | 29 (9.4) | 67 (18.3) | |

Bold = statistically significant.

Grade as defined by Nottingham Grading System.

Figure 4.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on Chk2 levels in ER − patients who received anthracycline chemotherapy. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on Chk2levels in ER − patients who received CMF chemotherapy. (C) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on Chk2 levels in ER + patients who received endocrine therapy. (D) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on Chk2 mRNA expression in the whole cohort. (E) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on Chk2 mRNA expression in ER − patients who received chemotherapy. (F) Kaplan-Meier curves showing BCSS based on Chk2 mRNA expression in ER + patients who received endocrine therapy.

ATM-Chk2 Coexpression in Breast Cancer

As there was a strong positive association between ATM and Chk2 expression (see Table 1, Table 2), we investigated if coexpression would influence survival. Patients with tumors that have low ATM and high Chk2 levels have the worst survival compared to tumors that have high ATM and high Chk2 levels (P = .033) (Figure 2C). The data suggest that ATM and Chk2 together have prognostic significance in patients. We then investigated in patients who received chemotherapy or endocrine therapy. As shown in Supplementary Figure S3, although there was trend, ATM-Chk2 expression did not significantly influence survival in patients in the various subgroups.

Multivariate Analysis

To investigate whether ATM-Chk2 independently influenced survival, we proceeded to multivariate analysis. As shown in Table 3, in multivariate Cox regression analysis including other validated prognostic factors (such as stage, histological grade, tumor size, p53, MIB1, and bcl-2), Chk2 expression was an independent predictor for BCSS. ATM-Chk2 coexpression showed a trend and reached near significance (P = .056).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis

| P Value | Exp (B) | 95% CI of Exp (B) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| BCSS | ||||

| Stage | .001 | 1.810 | 1.413 | 2.320 |

| Grade | .065 | 1.402 | 0.979 | 2.009 |

| Size | .009 | 1.250 | 1.057 | 1.478 |

| ATM | .307 | 1.226 | 0.829 | 1.812 |

| Chk2 | .030 | 1.465 | 1.037 | 2.069 |

| ATM-CHK2 coexpression | .056 | 0.847 | 0.715 | 1.004 |

| p53 | .559 | 1.130 | 0.750 | 1.705 |

| Bcl-2 | .001 | 0.443 | 0.301 | 0.653 |

| ER | .371 | 1.221 | 0.788 | 1.893 |

| Her2 | .399 | 1.099 | 0.883 | 1.362 |

| MIB1 | .340 | 1.106 | 0.899 | 1.361 |

Taken together, the data provide evidence that ATM and Chk2 expression has prognostic and predictive significance in breast cancer.

Discussion

This is the largest study to investigate the clinicopathological significance of ATM-Chk2 expression in sporadic breast cancers. A low level of ATM was associated with aggressive phenotypes including high grade, high mitotic index, pleomorphisms, de-differentiation, and triple-negative and basal-like phenotypes. The association between ER negativity and low ATM in human tumors concurs with the breast cancer cell line data where ATM was found to be low in several triple-negative cell lines including MDA-MB-231, BT-549, and MDA-MB-468 cells. ATM is a key player in the maintenance of genomic integrity [1], [2], [3], [4]. Loss of ATM and the resulting genomic instability may promote a mutator phenotype which is characterized by accelerated accumulation of mutations that ultimately drive an aggressive cancerous phenotype. Herein we demonstrate that, at the protein level, low ATM expression was associated with high grade, high mitotic index, de-differentiation, and pleomorphism. The hypothesis that low ATM is associated with genomic instability is further supported by the observation that low ATM was significantly associated with low expression of other DNA repair factors including BRCA1, XRCC1, FEN1, and SMUG1. Moreover, as low ATM tumors were also more likely to be p53 mutants, we speculate that this could contribute to additional genomic instability in tumors. In addition, not only was low ATM level significantly associated with mutant p53 status, but low-ATM/p53 mutants also have the worst survival compared to p53 wild-type/high-ATM tumors. The data suggest that ATM/p53-based stratification could be useful for personalization of therapy. A previous small study in 93 breast cancers suggested that tumors with normal ATM and wild-type p53 have good prognosis, whereas tumors with low ATM and wild-type p53 have poor survival [30]. The authors described only four tumors that had both low ATM and aberrant p53, and this was associated with good survival in that study [30]. In contrast, in our study, 231 tumors were p53 mutants with low ATM, and such tumors exhibited poor survival. Interestingly, in patients who received either anthracycline-based or CMF adjuvant chemotherapy, low ATM level was associated with poor survival, implying that ATM may also predict response to chemotherapy. The data appear to be counterintuitive in that several preclinical studies have suggested that ATM-deficient cells are sensitive to cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy [1], [2], [3], [4]. However, our data would concur with a recent report in breast cancers that showed a poor survival in patients with low ATM who received adjuvant/neoadjuvant chemotherapy [31]. Similarly, Knappskog et al., also showed that low ATM predicts resistance to anthracycline chemotherapy in breast cancer [32]. To investigate whether low ATM expression is due to low mRNA expression, we investigated the METABRIC cohort and again demonstrated that low ATM mRNA expression was associated with adverse clinical outcome in patients. Whether ATM gene copy number changes, mutational changes, or posttranscriptional miRNA-mediated regulation of ATM mRNA expression contributes to the low ATM seen in our study is not known. Interestingly, Bueno et al., demonstrated that ATM copy number loss (seen in 12% of breast tumors) and miR-421 overexpression (seen in 36.5% of breast tumors) were associated with ATM loss, thereby providing some mechanistic evidence for ATM regulation [31]. In contrast, Guo et al., who investigated 296 breast tumors in Chinese patients [33] observed high ATM levels in ER − tumors. However, the authors did not describe any association between ATM level and BCSS in that study. However, two previous studies in white patients demonstrate that low ATM level may be associated with aggressive phenotype and poor survival [31], [34]. Tommiska et al., investigated in observed that low ATM was common in BRCA1/BRCA2 deficient tumors as well as ER- tumors [34]. In a further study in white patients by Bueno et al., low ATM in white tumors was shown to be associated with poor prognosis [31]. Similarly, in the current study, in white patients with breast tumors, we observed that low ATM protein level was associated with aggressive clinicopathological features and poor survival in ER − tumors. Taken together, the data suggest that, in white patients, low ATM appears to be a poor prognostic biomarker. The data presented in white tumors is in contrast to Guo et al. [33], and may be accounted by either racial differences in tumor biology or different immunohistochemical protocols used across different studies. Preclinically, Guo et al., showed that ER activates miR-18a and miR-106a, which in turn downregulate ATM in cancer cell lines as well as in ER − tumors [33]. In contrast, Bueno et al., observed that miR-421 was overexpressed and correlated to low ATM levels [31]. Together, the data suggest that the regulation of ATM expression by miRNAs may be complex in vivo. Further mechanistic studies are required to clarify the role of miRNA in the regulation of ATM expression. Moreover, the data presented would also concur with studies in colorectal cancer [35] and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [36] where low ATM level has been shown to be a poor prognostic biomarker. Taken together, the data provide compelling evidence for the role of low ATM expression in promoting aggressive breast cancer. Whether such ATM-deficient tumors can be targeted by synthetic lethality approaches has been investigated recently. In lymphoid tumors, PARP inhibition was synthetically lethal in ATM-deficient cells [37]. Similarly, in breast and gastric cancer cell line, models of synthetic lethality with PARP inhibition have been demonstrated [38], [39]. Using a similar approach, we have recently demonstrated that ATM-deficient cells are sensitive to inhibitors of APE1, a key player in base excision repair [40]. Given the recent clinical success of PARP inhibitors in BRCA1/2-deficient breast and ovarian cancers [41], whether a similar clinical approach would be feasible in ATM-deficient breast cancer clearly needs investigation in prospective clinical trials. The role of Chk2 in sporadic breast cancer appears to be more complex than ATM. In the current study, low nuclear Chk2 protein level was associated with ER −/PR −/AR − tumors. Moreover, low nuclear Chk2 level was also associated with low levels of several DNA repair factors including BRCA1, XRCC1, and APE1, implying increased genomic instability in tumors that have low nuclear Chk2. In a previous small study of 100 breast cancers, low Chk2 was reported to be associated with advanced stage but not with survival [42]. Similarly, in another study of 611 breast cancers [43], low Chk2 was reported in 21.1% of tumors and was associated with larger tumor size but again not associated with survival. In the current study, although we did not observe any correlation with stage, in ER + tumors that received no endocrine therapy, low Chk2 was associated with poor survival, suggesting that Chk2 may still have prognostic significance in ER + tumors. However, high Chk2 level was associated with poor survival in ER-negative tumors that received no chemotherapy in our study. Interestingly, p53 mutation status may influence the prognostic impact of Chk2; p53 mutants with high Chk2 have the worst survival, and p53 mutants with low Chk2 appear to have the best survival. Given that Chk2 is a key activator of p53 [44] and that combined inactivation of p53 and Chk2 has been reported in breast cancers [45], detailed mechanistic preclinical investigations are required to understand the complex functional link between Chk2 and p53 in breast tumors. Although Chk2 appeared to have prognostic significance, Chk2 protein level was not associated with survival in patients who received chemotherapy or endocrine therapy, suggesting that Chk2 is unlikely to be a predictive factor in breast cancers. To complicate the matter further, we observed the reverse at the mRNA level in breast tumors. Low Chk2 mRNA was associated with poor survival in ER-negative tumors that received chemotherapy, but high Chk2 mRNA was associated with poor survival in ER + tumors that received endocrine therapy. These new unexplained observations suggest that further studies are required to clarify the role of Chk2 in sporadic breast cancers. When ATM and Chk2 were investigated together, we found that tumors with low ATM/high Chk2 had the worst survival compared to those with high ATM/high Chk2 levels. However, limitations to our study are that it was retrospective and did not investigate the functional status of ATM-Chk2 pathway as assessed, for example, by expression of phosphorylated Chk2 and other ATM substrates.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that ATM-Chk2 pathway is a promising biomarker in breast cancer.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2014.09.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Figure Legends

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

References

- 1.Shiloh Y, Ziv Y. The ATM protein kinase: regulating the cellular response to genotoxic stress, and more Nature reviews. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:197–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marechal A, Zou L. DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012716. [pii: a012716] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrose M, Gatti RA. Pathogenesis of ataxia–telangiectasia: the next generation of ATM functions. Blood. 2013;121:4036–4045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-456897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditch S, Paull TT. The ATM protein kinase and cellular redox signaling: beyond the DNA damage response. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith J, Tho LM, Xu N, Gillespie DA. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;108:73–112. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380888-2.00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoni L, Sodha N, Collins I, Garrett MD. CHK2 kinase: cancer susceptibility and cancer therapy — two sides of the same coin? Nature reviews. Cancer. 2007;7:925–936. doi: 10.1038/nrc2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn J, Urist M, Prives C. The Chk2 protein kinase. DNA Repair. 2004;3:1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartek J, Lukas J. Chk1 and Chk2 kinases in checkpoint control and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:421–429. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGowan CH. CHK2: a tumor suppressor or not? Cell Cycle. 2002;1:401–403. doi: 10.4161/cc.1.6.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prokopcova J, Kleibl Z, Banwell CM, Pohlreich P. The role of ATM in breast cancer development. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;104:121–128. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed M, Rahman N. ATM and breast cancer susceptibility. Oncogene. 2006;25:5906–5911. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khanna KK, Chenevix-Trench G. ATM and genome maintenance: defining its role in breast cancer susceptibility. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2004;9:247–262. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000048772.92326.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angele S, Hall J. The ATM gene and breast cancer: is it really a risk factor? Mutat Res. 2000;462:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nevanlinna H, Bartek J. The CHEK2 gene and inherited breast cancer susceptibility. Oncogene. 2006;25:5912–5919. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Fatah T, Arora A, Agarwal D, Moseley P, Perry C, Thompson N, Green AR, Rakha E, Chan S, Ball G. Adverse prognostic and predictive significance of low DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) expression in early-stage breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:309–320. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdel-Fatah TM, Russell R, Albarakati N, Maloney DJ, Dorjsuren D, Rueda OM, Moseley P, Mohan V, Sun H, Abbotts R. Genomic and protein expression analysis reveals flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1) as a key biomarker in breast and ovarian cancer. Mol Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.04.009. [pii: S1574-7891(14)00092-1] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdel-Fatah TM, Russell R, Agarwal D, Moseley P, Abayomi MA, Perry C, Albarakati N, Ball G, Chan S, Caldas C. DNA polymerase beta deficiency is linked to aggressive breast cancer: a comprehensive analysis of gene copy number, mRNA and protein expression in multiple cohorts. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:520–532. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Fatah TM, Perry C, Moseley P, Johnson K, Arora A, Chan S, Ellis IO, Madhusudan S. Clinicopathological significance of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) expression in oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143:411–421. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2820-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel-Fatah TM, Albarakati N, Bowell L, Agarwal D, Moseley P, Hawkes C, Ball G, Chan S, Ellis IO, Madhusudan S. Single-strand selective monofunctional uracil-DNA glycosylase (SMUG1) deficiency is linked to aggressive breast cancer and predicts response to adjuvant therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142:515–527. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2769-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sultana R, Abdel-Fatah T, Abbotts R, Hawkes C, Albarakati N, Seedhouse C, Ball G, Chan S, Rakha EA, Ellis IO. Targeting XRCC1 deficiency in breast cancer for personalized therapy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1621–1634. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdel-Fatah TM, Perry C, Arora A, Thompson N, Doherty R, Moseley PM, Green AR, Chan SY, Ellis IO, Madhusudan S. Is there a role for base excision repair in estrogen / estrogen receptor driven breast cancers? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014 Sept 22 doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6077. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albarakati N, Abdel-Fatah TM, Doherty R, Russell R, Agarwal D, Moseley P, Perry C, Arora A, Alsubhi N, Seedhouse C. Targeting BRCA1-BER deficient breast cancer by ATM or DNA-PKcs blockade either alone or in combination with cisplatin for personalized therapy. Mol Oncol. 2014;146:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdel-Fatah TM, Perry C, Dickinson P, Ball G, Moseley P, Madhusudan S, Ellis IO, Chan SY. Bcl2 is an independent prognostic marker of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) and predicts response to anthracycline combination (ATC) chemotherapy (CT) in adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2801–2807. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdel-Fatah TM, Powe DG, Agboola J, Adamowicz-Brice M, Blamey RW, Lopez-Garcia MA, Green AR, Reis-Filho JS, Ellis IO. The biological, clinical and prognostic implications of p53 transcriptional pathways in breast cancers. J Pathol. 2010;220:419–434. doi: 10.1002/path.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdel-Fatah TM, Powe DG, Ball G, Lopez-Garcia MA, Habashy HO, Green AR, Reis-Filho JS, Ellis IO. Proposal for a modified grading system based on mitotic index and Bcl2 provides objective determination of clinical outcome for patients with breast cancer. J Pathol. 2010;222:388–399. doi: 10.1002/path.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdel-Fatah TMA, Middleton F, Arora A, Moseley P, Agarwal D, Perry C, Chan S, Green A, Ball G, Ellis IO. Untangling the ATR-Chk1 network for prognostication, prediction and therapeutic target validation in breast cancer. Mol Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.10.013. [Revision submitted] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakha EA, Starczynski J, Lee AH, Ellis IO. The updated ASCO/CAP guideline recommendations for HER2 testing in the management of invasive breast cancer: a critical review of their implications for routine practice. Histopathology. 2014;64:609–615. doi: 10.1111/his.12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G, Rueda OM, Dunning MJ, Speed D, Lynch AG, Samarajiwa S, Yuan Y. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang H, Reinhardt HC, Bartkova J, Tommiska J, Blomqvist C, Nevanlinna H, Bartek J, Yaffe MB, Hemann MT. The combined status of ATM and p53 link tumor development with therapeutic response. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1895–1909. doi: 10.1101/gad.1815309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bueno RC, Canevari RA, Villacis RA, Domingues MA, Caldeira JR, Rocha RM, Drigo SA, Rogatto SR. ATM down-regulation is associated with poor prognosis in sporadic breast carcinomas. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:69–75. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knappskog S, Chrisanthar R, Lokkevik E, Anker G, Ostenstad B, Lundgren S, Risberg T, Mjaaland I, Leirvaag B, Miletic H. Low expression levels of ATM may substitute for CHEK2/TP53 mutations predicting resistance towards anthracycline and mitomycin chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R47. doi: 10.1186/bcr3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo X, Yang C, Qian X, Lei T, Li Y, Shen H, Fu L, Xu B. Estrogen receptor alpha regulates ATM Expression through miRNAs in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4994–5002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tommiska J, Bartkova J, Heinonen M, Hautala L, Kilpivaara O, Eerola H, Aittomaki K, Hofstetter B, Lukas J, von Smitten K. The DNA damage signalling kinase ATM is aberrantly reduced or lost in BRCA1/BRCA2-deficient and ER/PR/ERBB2-triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:2501–2506. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beggs AD, Domingo E, McGregor M, Presz M, Johnstone E, Midgley R, Kerr D, Oukrif D, Novelli M, Abulafi M. Loss of expression of the double strand break repair protein ATM is associated with worse prognosis in colorectal cancer and loss of Ku70 expression is associated with CIN. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1348–1355. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossi D, Gaidano G. ATM and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: mutations, and not only deletions, matter. Haematologica. 2012;97:5–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.057109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weston VJ, Oldreive CE, Skowronska A, Oscier DG, Pratt G, Dyer MJ, Smith G, Powell JE, Rudzki Z, Kearns P. The PARP inhibitor olaparib induces significant killing of ATM-deficient lymphoid tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2010;116:4578–4587. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilardini Montani MS, Prodosmo A, Stagni V, Merli D, Monteonofrio L, Gatti V, Gentileschi MP, Barila D, Soddu S. ATM-depletion in breast cancer cells confers sensitivity to PARP inhibition. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:95. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubota E, Williamson CT, Ye R, Elegbede A, Peterson L, Lees-Miller SP, Bebb DG. Low ATM protein expression and depletion of p53 correlates with olaparib sensitivity in gastric cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:2129–2137. doi: 10.4161/cc.29212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sultana R, McNeill DR, Abbotts R, Mohammed MZ, Zdzienicka MZ, Qutob H, Seedhouse C, Laughton CA, Fischer PM, Patel PM. Synthetic lethal targeting of DNA double-strand break repair deficient cells by human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease inhibitors. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2433–2444. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yap TA, Sandhu SK, Carden CP, de Bono JS. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors: exploiting a synthetic lethal strategy in the clinic. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:31–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ribeiro-Silva A, Moutinho MA, Moura HB, Vale FR, Zucoloto S. Expression of checkpoint kinase 2 in breast carcinomas: correlation with key regulators of tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and survival. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:373–382. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kilpivaara O, Bartkova J, Eerola H, Syrjakoski K, Vahteristo P, Lukas J, Blomqvist C, Holli K, Heikkila P, Sauter G. Correlation of CHEK2 protein expression and c.1100delC mutation status with tumor characteristics among unselected breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:575–580. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stolz A, Ertych N, Bastians H. Tumor suppressor CHK2: regulator of DNA damage response and mediator of chromosomal stability. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:401–405. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan A, Yuille M, Repellin C, Reddy A, Reelfs O, Bell A, Dunne B, Gusterson BA, Osin P, Farrell PJ. Concomitant inactivation of p53 and Chk2 in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:1316–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Figure Legends

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3