Abstract

Background

The majority of commercial cotton varieties planted worldwide are derived from Gossypium hirsutum, which is a naturally occurring allotetraploid produced by interspecific hybridization of A- and D-genome diploid progenitor species. While most cotton species are adapted to warm, semi-arid tropical and subtropical regions, and thus perform well in these geographical areas, cotton seedlings are sensitive to cold temperature, which can significantly reduce crop yields. One of the common biochemical responses of plants to cold temperatures is an increase in omega-3 fatty acids, which protects cellular function by maintaining membrane integrity. The purpose of our study was to identify and characterize the omega-3 fatty acid desaturase (FAD) gene family in G. hirsutum, with an emphasis on identifying omega-3 FADs involved in cold temperature adaptation.

Results

Eleven omega-3 FAD genes were identified in G. hirsutum, and characterization of the gene family in extant A and D diploid species (G. herbaceum and G. raimondii, respectively) allowed for unambiguous genome assignment of all homoeologs in tetraploid G. hirsutum. The omega-3 FAD family of cotton includes five distinct genes, two of which encode endoplasmic reticulum-type enzymes (FAD3-1 and FAD3-2) and three that encode chloroplast-type enzymes (FAD7/8-1, FAD7/8-2, and FAD7/8-3). The FAD3-2 gene was duplicated in the A genome progenitor species after the evolutionary split from the D progenitor, but before the interspecific hybridization event that gave rise to modern tetraploid cotton. RNA-seq analysis revealed conserved, gene-specific expression patterns in various organs and cell types and semi-quantitative RT-PCR further revealed that FAD7/8-1 was specifically induced during cold temperature treatment of G. hirsutum seedlings.

Conclusions

The omega-3 FAD gene family in cotton was characterized at the genome-wide level in three species, showing relatively ancient establishment of the gene family prior to the split of A and D diploid progenitor species. The FAD genes are differentially expressed in various organs and cell types, including fiber, and expression of the FAD7/8-1 gene was induced by cold temperature. Collectively, these data define the genetic and functional genomic properties of this important gene family in cotton and provide a foundation for future efforts to improve cotton abiotic stress tolerance through molecular breeding approaches.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-014-0312-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Chilling tolerance, Cotton, Drought, Fatty acid desaturase, Gossypium, Linolenic acid, Omega-3 fatty acid

Background

Cotton is an important crop worldwide, providing the majority of fiber to the textile industry and a significant amount of oilseed for food, feed, and biofuel purposes. The most commonly grown cotton species for commercial production is Gossypium hirsutum, an allotetraploid species with a remarkable evolutionary history. The cotton genus (Gossypium) originated approximately 12 million years ago (MYA) [1] and underwent rapid radiation and adaptation to many arid or seasonally arid tropical or subtropical regions of the world [2,3]. Despite a wide range of morphological phenotypes, including trees and bushes, cytogenetic and karyotyping analyses revealed that the majority of plants can be categorized as having 1 of 8 distinct types of diploid genomes (n = 13) [3]. The A, B, E, and F genome-containing plants are found in Africa and Arabia, the C, G, and K genomes are common to Australian plants, and the D genome-containing species are found in Mesoamerica. G. hirsutum is an AD tetraploid also found predominantly in Mesoamerica, which suggests that this species arose by trans-oceanic dispersal of A-type seed from Africa, followed by chance interspecific hybridization with a D-containing progenitor species in the New World [3,4]. Molecular systematics studies suggest that the A and D diploid species evolved separately for approximately 5–10 million years before being reunited in the same nucleus approximately 1–2 MYA [5]. G. hirsutum (the source of upland cotton) was subsequently domesticated for fiber production in the last few thousand years in the New World, and as such, is an interesting model system not only for use in the study of genome evolution, but also for studying the role of polyploidy in crop development and domestication [6].

Given that G. hirsutum is native to the tropics and subtropics, it is adapted to the warm temperatures of arid and semi-arid climates [7,8]. In the US, upland cotton is planted at various times throughout the year and the beginning and end of the growing seasons often include sub-optimal growth temperatures and environmental conditions. For instance, heat and drought can cause significant reductions in crop yield during the latter parts of the growing season [9,10]. Exposure of cotton to sudden episodes of cold temperature during the early parts of the growing season, moreover, can cause significant damage to cotton seedlings and the plants may not fully recover [11-15]. Development of upland cotton varieties with improved tolerance to low temperature stress could thus improve the agronomic performance of the crop and thereby significantly impact the cotton industry [12,14].

The adaptation of plants to low temperature is a complex biological process that involves changes in expression of many different genes and alteration in many different metabolites [16-19]. One of the common biochemical responses in plants to cold temperature is an increase in relative content of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) [20-23]. Polyunsaturated fatty acids have a lower melting temperature than saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, and their increased accumulation is thought to help maintain membrane fluidity and cellular integrity at cold temperatures [24]. For instance, cold temperature treatment of cotton seedlings has been shown to induce the accumulation of PUFAs [15,25], and inclusion of an inhibitor of PUFA biosynthesis during the treatment rendered the seedlings more susceptible to cold temperature damage [15]. By contrast, warm temperatures were inversely associated with PUFA content and changed during leaf expansion, and this impacted photosynthetic performance of cotton plants in the field [26]. Thus, gaining a better understanding of the genes that regulate PUFA production in cotton represents a first step in improving cold and thermotolerance in upland cotton germplasm.

The metabolic pathways for PUFA production in plants are generally well understood and have been elucidated primarily by studying various fatty acid desaturase, or fad mutants, of Arabidopsis that are blocked at various steps of lipid metabolism [27]. Briefly, fatty acid biosynthesis occurs in the plastids of plant cells, with a successive concatenation of 2 carbon units resulting in production of the 16- or 18-carbon long fatty acids that predominate in cellular membranes. A soluble fatty acid desaturase is present in the plastid stroma for conversion of 18:0 into 18:1, where the number before the colon represents the total number of carbons in the fatty acid chain and the number after the colon indicates the number of double bonds. The 18:1 fatty acid is subsequently available for further desaturation by one of two parallel pathways operating in either the plastid or endoplasmic reticulum (ER). For instance, 18:1 may be converted to 18:2 in plastids by a membrane-bound fatty acid desaturase called FAD6, or the 18:1 may be exported from the plastids to the ER for conversion to 18:2 by a structurally related enzyme called FAD2. The FAD2 and FAD6 enzymes are similar at the polypeptide sequence level, with the exception that the FAD6 protein contains a longer N-terminal sequence that is characteristic of a chloroplast transit peptide. In a similar fashion, 18:2 may be converted into 18:3 in plastids by the FAD7 or FAD8 enzymes, which are encoded by two closely related genes in Arabidopsis, or can be exported to the ER for conversion to 18:3 by the FAD3 enzyme. This latter group of enzymes (FAD7/FAD8 and FAD3) are referred to as omega-3 fatty acid desaturases, since they introduce a double bond at the omega-3 position of the fatty acid structure. Thus the FAD6 and FAD2 enzymes, which produce 18:2, and the FAD7/FAD8 and FAD3 enzymes, which produce 18:3, all play central roles in production of the PUFAs that are present in all plant species.

Knowledge of the FAD genes encoding these enzymes has permitted more detailed analyses of the role of these genes, and their fatty acid products, in plant lipid metabolism and abiotic stress response. For instance, omega-3 fatty acids are known to increase in plants in response to both drought [28,29] and cold temperature [20-23], and over-expression of omega-3 desaturases in various transgenic plants has been shown to improve both drought and chilling tolerance [30-35]. The ER-localized desaturases FAD2 and FAD3 are also involved in production of PUFA components of seed oils [27], and given the importance of these fatty acids to human nutrition, and to determining stability of oils during cooking or other food applications, molecular markers for these genes have been developed for evaluating germplasm and identifying oilseed varieties with improved oil compositions [36-39].

Given the prominent role of PUFAs in chilling and drought adaptation of plants, and the susceptibility of cotton seedlings to both of these environmental conditions, we sought to identify and characterize the genes involved in PUFA synthesis in cotton. Since several FAD2 genes have been previously reported and characterized in cotton [40-46], we chose instead to focus on the analysis of the omega-3 FAD gene family, of which no members have been previously studied. Here we describe the complete omega-3 gene family in both tetraploid G. hirsutum as well as extant A and D diploid progenitor species (G. herbaceum and G. raimondii, respectively), which allowed clear assignment of all homoeologous genes. We also describe organ and cell-type specific gene expression patterns, and identify a single FAD7/FAD8-type gene that is inducible by both drought as well as cold-temperature exposure of cotton seedlings. Collectively, these data define the content and functional genomic properties of this important gene family in commercial upland cotton.

Results and discussion

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of the omega-3 FAD gene family in cotton

The omega-3 FAD-type genes in G. hirsutum (AD1 allotetraploid), G. herbaceum (A1 diploid), and G. raimondii (D5 diploid) were cloned and sequenced using a combination of database mining, degenerate primer-based PCR screening, genome resequencing, and gene-specific PCR-based cloning, as described in the Methods. All cloning, DNA sequencing, and RT-PCR primer sequences are provided in Additional files 1, 2, and 3, respectively. During the cloning process, the genome sequence of G. raimondii (D5) was released [47], which confirmed the identity of omega-3 genes we had identified in this organism. The perfect match between our cloned gene sequences and the genes in the genome database provided a useful check for the fidelity of the cloning process employed here. More recently, a draft of the genome sequence of G. arboreum (A2) was released [48], which will enable future studies aimed at comparing gene sequences between A genome-containing species.

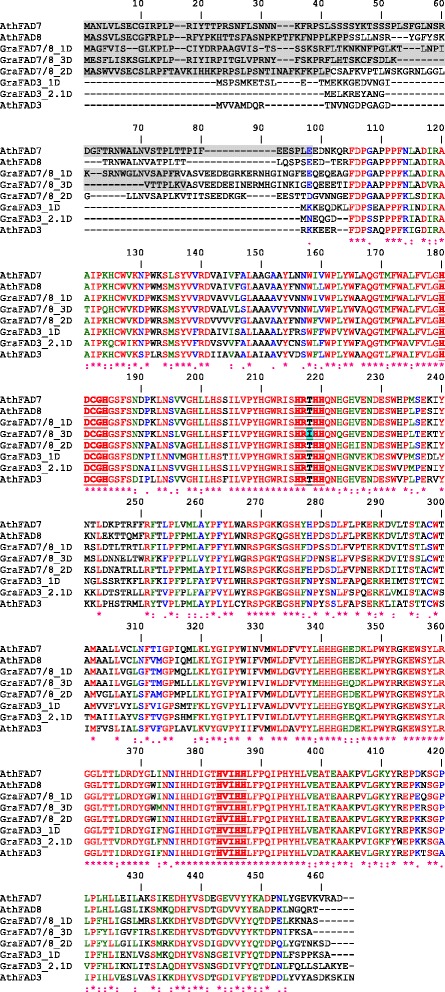

Five distinct omega-3 FAD-type genes were identified, and all of the genes were present in each of the three cotton species studied, which allowed for unambiguous assignment of each homoeolog in G. hirsutum (Table 1; see Additional file 4 for GenBank accession numbers and Additional files 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 for gene alignments). Two of the genes encode FAD3-type enzymes localized in the ER (FAD3-1 and FAD3-2) and three genes encode FAD7/8-type enzymes in the chloroplast (FAD7/8-1, FAD7/8-2, FAD7/8-3) (Figure 1; only the encoded polypeptide sequences from G. raimondii are shown for clarity). The latter group of polypeptides contained longer N-terminal sequences predicted to serve as chloroplast targeting peptides (Figure 1). All of the omega-3 FADs shared conserved regions of polypeptide sequence, including three “histidine boxes” that are involved in binding two iron atoms at the enzyme active site (Figure 1; [49]). Notably, the enzyme encoded by FAD7/8-3 harbored a threonine to isoleucine substitution within the second histidine box (Figure 1), which is typically not observed in FAD7/8-type sequences (Figure 1 and [50]), and this substitution was detected in all FAD7/8-3 sequences in the three cotton species (data not shown). Given the highly conserved nature of the histidine box sequences in various FAD7/8-type enzymes [50], and that alterations to these regions are known to disrupt or alter enzyme activity [51], these data suggest that the FAD7/8-3 gene of cotton might encode an enzyme with reduced or altered enzyme activity.

Table 1.

Summary of omega-3 FAD genes cloned from cotton

| Omega-3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAD gene | G. herbaceum | G. raimondii | G. hirsutum | Type |

| FAD3-1 | GheFAD3-1A* | GraFAD3-1D | GhiFAD3-1A, GhiFAD3-1D | ER |

| FAD3-2 | GheFAD3-2.1A | GraFAD3-2.1D | GhiFAD3-2.1A, GhiFAD3-2.1D | ER |

| GheFAD3-2.2A | --- | GhiFAD3-2.2A | --- | |

| --- | ||||

| FAD7/8-1 | GheFAD7/8-1A | GraFAD7/8-1D | GhiFAD7/8-1A, GhiFAD7/8-1D | Chloroplast |

| FAD7/8-2 | GheFAD7/8-2A | GraFAD7/8-2D | GhiFAD7/8-2A, GhiFAD7/8-2D | Chloroplast |

| FAD7/8-3 | GheFAD7/8-3A | GraFAD7/8-3D | GhiFAD7/8-3A, GhiFAD7/8-3D | Chloroplast |

*Gene nomenclature includes the first three letters of the plant genus and species, followed by the gene name, and ending with the genome designation (A for G. herbaceum or the A subgenome of G. hirsutum, or D for G. raimondii or the D subgenome of G. hirsutum). The FAD3-2 gene is duplicated in both G. herbaceum and G. hirsutum, and the paralogs are designated FAD3-2.1 and FAD3-2.2. The coding sequence of FAD3-2.2 contains multiple in-frame stop codons and a frame-shift mutation and thus is likely a pseudogene. The single FAD3-2 gene within G. raimondii is designated FAD3-2.1 for clarity to indicate that it is more similar to the FAD3-2.1 sequence in the A genome-containing species. GenBank accession numbers are provided in Additional file 4.

Figure 1.

Alignment of encoded omega-3 FAD polypeptide sequences from G. raimondii (Gra) and Arabidopsis thaliana (Ath). Polypeptide sequences were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm with default parameters (npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr; [52]). Each polypeptide sequence was evaluated using ChloroP (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/; [53]) to identify putative chloroplast transit peptides, which are highlighted grey. Identical amino acids are highlighted in red, and the three conserved “histidine boxes” known to be involved in binding two iron atoms at the active site [49] are bolded and underlined. Note the substitution of a threonine residue with isoleucine in the FAD7/8-3 sequence of the second histidine box, which is highlighted blue.

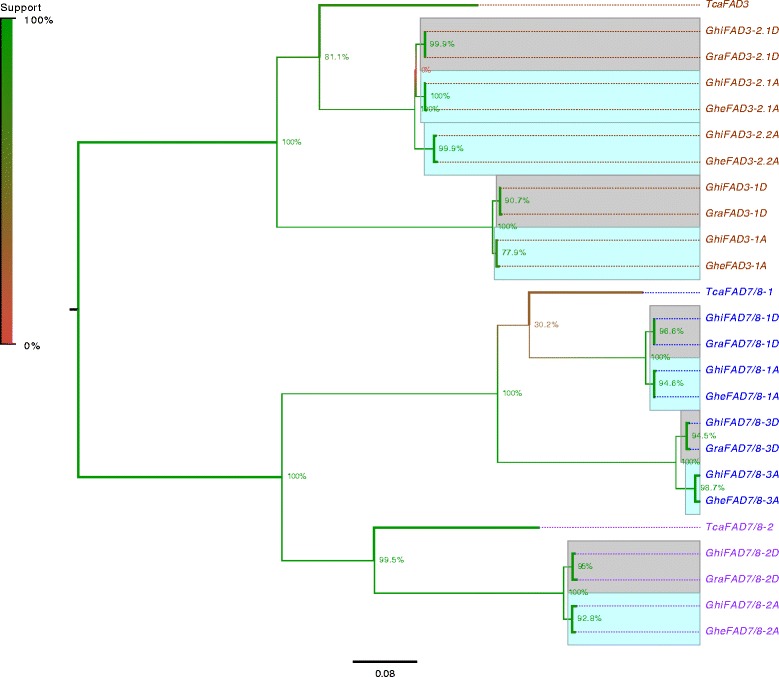

To gain insight to the evolution and function of the omega-3 FAD gene family in cotton, the omega-3 sequences in the three species were compared with the sequences of Theobroma cacao, which is a close relative of cotton in the Malvaceae family and whose genome has been sequenced [54]. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the omega-3 FADs in these species separated into three well defined monophyletic groups, each of them containing one cacao and several cotton genes (Figure 2). The establishment of these three groups thus predates the divergence of cotton and cacao approximately 60 MYA [47]. In cotton, the gene family underwent further expansion after divergence from T. cacao but before divergence of the A and D genome species circa 6–7 MYA [55], with duplicated gene pairs observed for FAD3-type (FAD3-1 and FAD3-2.1) and FAD7/8-type (FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-3) genes in two of the three monophyletic groups (Figure 2; Table 1). These duplications are consistent with the genome duplication events that occurred in the cotton lineage shortly after its divergence from cacao [47]. Moreover, the FAD3-2.1 gene underwent further duplication in the A genome species (G. herbaceum), but not in the D genome species (G. raimondii), and this further duplication persists in tetraploid G. hirsutum. These data indicate that the latter duplication event happened after the split of the diploid progenitor species, but before the interspecific hybridization event that gave rise to tetraploid G. hirsutum circa 1–2 MYA [4]. The FAD3-2.2 gene is likely a pseudogene, because the coding sequence contains several in-frame stop codons and a frame-shift mutation that are present in both G. herbaceum and G. hirsutum sequences (Additional file 6). Taken together, these data reveal that the omega-3 FAD gene family underwent rapid expansion during cotton speciation, with additional elaboration in A genome species prior to interspecific hybridization.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of omega-3 FAD genes from G. raimondii (Gra), G. herbaceum (Ghe), G. hirsutum (Ghi) , and T. cacao (Tca). Gene name abbreviations correspond to those in Table 1. Branches are color-coded based on phylogenetic support, and support for individual nodes is indicated on the figure. Taxon names are color-coded based on the three major monophyletic groups: Clade 1 (brown), Clade 2 (blue), and Clade 3 (purple). Cotton A and D genome genes are highlighted in cyan and grey respectively, and dotted lines are used to indicate the terminal branches corresponding to the right-justified labels.

RNA-seq analysis of gene expression patterns

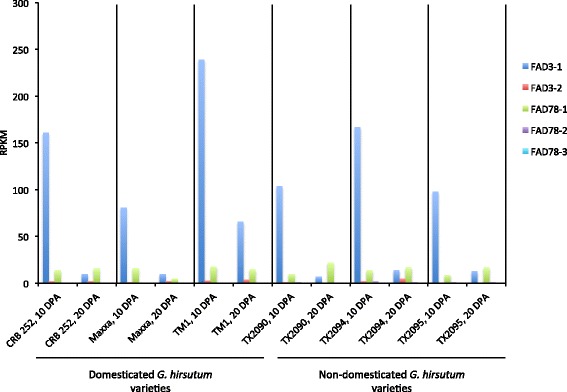

To gain insight to the function of the omega-3 FAD genes, the expression patterns in various cotton organs, cell types and treatments were evaluated based on RNA-seq experiments. A recent transcriptomic study of developing cotton fibers in wild and domesticated G. hirsutum lines revealed that the domestication process resulted in massive reprogramming of fiber gene expression, with over 5,000 genes showing significant changes in expression between wild and domesticated species [56]. Wild cotton fibers are short and brown, while domesticated fibers are longer and white. Two developmental stages were studied, including 10 days post anthesis (DPA), which represents primary cell wall growth, and 20 DPA, representing the transition to secondary cell wall synthesis [56]. Analysis of RNA-seq data for the omega-3 FAD gene family revealed that the FAD3-1 gene was predominantly expressed during primary cell wall synthesis, and was reduced during secondary wall synthesis (Figure 3). All other omega-3 FAD genes were expressed at very low levels. This pattern was consistently observed in both wild and domesticated G. hirsutum varieties (Figure 3), suggesting that FAD3-1 expression is involved in a shared, and not domestication-specific, aspect of fiber production. Notably, linolenic acid is the most abundant fatty acid in elongating cotton fibers [57], and a separate study of gene expression in 1 vs. 7 DPA fibers in G. hirsutum showed strong induction of a FAD3-type gene during primary cell wall synthesis [57]. Comparison of the gene fragment identified in that study with the sequences described here showed that the gene fragment corresponded to the FAD3-1D homoeolog of G. hirsutum (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that the FAD3-1 gene plays an important role in directing synthesis of high levels of omega-3 fatty acids present in elongating cotton fibers.

Figure 3.

Expression of omega-3 FAD genes in developing cotton fibers. Cotton fibers were harvested at 10 and 20 DPA, which represents primary and secondary cell wall synthesis, respectively, and RNA-seq analysis was performed as described [56]. Transcripts were quantified as “reads per kilobase per million mapped reads” (RPKM). For simplicity, data for A and D homoeologous sequences were combined. Plant varieties are listed along the bottom and include Coker315 and TM1, which represent domesticated cotton G. hirsutum varieties, and TX2090 and TX2094, which are wild G. hirsutum varieties.

Analysis of transcript levels in adjacent, developing seed tissues of domesticated G. hirsutum showed a very different gene expression profile than fibers, with low levels of all omega-3 gene family members observed at each time point (Figure 4A). This likely explains the very low level of linolenic acid found in cottonseed oil, which accounts for ~0.2% of seed oil fatty acid composition [58]. Analysis of transcripts in petals, however, showed relatively high levels of expression for both FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-2 (Figure 4B). Analysis of cotton leaves showed a somewhat similar pattern, but FAD7/8-1 levels were reduced (Figure 4C). Notably, similar gene expression patterns were detected in fibers, seeds, petals and leaves of other cotton varieties and species, suggesting that the mechanisms of omega-3 FAD gene regulation were anciently established (Additional file 10). Taken together, these data reveal conserved, and differential gene expression patterns in various tissues and organs in cotton.

Figure 4.

Expression of omega-3 FAD genes in G. hirsutum seeds, petals and leaves. (A) Developing cottonseeds were harvested from G. hirsutum plants at the indicated times, then RNA-seq analysis was performed as described. Transcripts were quantified as “reads per kilobase per million mapped reads” (RPKM). For simplicity, data for A and D homoeologous sequences were combined. RNA-seq was also performed on cotton petals (B) as well as cotton leaves (C), as described [59,60]. Values represent average and standard deviation of three biological replicates. For data presented in panels (B) and (C), student’s t-test was used for comparison of FAD7/8-1 to FAD7/8-2, and * denotes p <0.05.

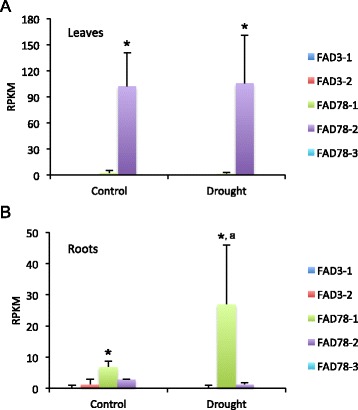

RNA-seq analysis was also performed on cotton plants subjected to drought treatment. The G. hirsutum cultivar Siokra L-23 was used for this analysis since it was previously selected for enhanced water-deficit tolerance [61]. Examination of omega-3 FAD transcript levels in control and drought treated cotton leaves confirmed that FAD7/8-2 was predominantly expressed in leaves, and furthermore that expression of this gene did not change appreciably in response to drought (Figure 5A). Analysis of gene expression in root tissues, however, revealed that the FAD7/8-1 gene was predominantly expressed, and expression was moderately induced by drought treatment (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Expression of omega-3 FAD genes in drought-treated G. hirsutum plants. The G. hirsutum cultivar Siokra L-23 was subjected to drought treatment, then gene expression in cotton leaves (A) or roots (B) was analyzed by RNA-seq analysis, as described [61]. Transcripts were quantified as “reads per kilobase per million mapped reads” (RPKM). For simplicity, data for A and D homoeologous sequences were combined. Values represent average and standard deviation of three biological replicates. Student’s t-test was used for comparison of FAD7/8-1 to FAD7/8-2, and * denotes p <0.05. A comparison was also made between FAD7/8-1 in control and drought treated plants, and the “a” denotes p <0.10.

Taken together, these data define organ and cell-type specific gene expression patterns for various members of the omega-3 fatty acid desaturase gene family in G. hirsutum, with FAD3-1 expressed predominantly in fibers, FAD7/8-2 in leaves, and FAD7/8-1 induced by drought treatment in cotton roots.

FAD7/8-1 expression is induced in cotton seedlings in response to cold temperature

To investigate gene expression patterns in cold-treated G. hirsutum seedlings, we first developed gene-specific PCR primers capable of distinguishing each omega-3 FAD homoeolog. We chose to develop PCR-based strategies rather than RNA-seq for monitoring gene expression since the PCR primers developed herein can be used also for future candidate gene association mapping studies. The goal of such mapping studies is to test whether sequence variants (e.g., single-nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) at candidate genes are statistically associated with a particular trait (e.g., chilling tolerance) in a panel of diverse lines [62,63]. To develop homoeolog-specific primers, we first aligned the respective omega-3 FAD genes to identify SNPs and insertions-deletions (indels) that were specific to each gene (Additional files 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9). Our general strategy for designing primers was that each primer pair should amplify a fragment of approximately 500 bp from mRNA, and the 3′-most nucleotide of each primer should be unique to each homoeolog. The specificity of each primer set was tested and optimized using gradient PCR annealing conditions and plasmid DNA templates containing either the target homoeolog, or the most closely related sequence. In some cases, the primers amplified both homoeologs and needed redesigning for improved specificity. The final sets of primers capable of distinguishing each homoeolog are listed in Additional file 3. Primer optimization experiments for FAD3-type genes are presented in Additional file 11, and FAD7/8-type genes are shown in Additional file 12.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of transcript levels in fully expanded cotyledons (Additional file 12B) and 13-day-old leaves of seedlings (Figure 6A) showed that the FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-2 genes were each expressed, and homoeologous transcripts for each gene could be detected. Notably, the sizes of all RT-PCR products corresponded to the sizes expected from amplification of the respective homoeologous cDNAs (Additional files 11 and 12), and not from genomic DNA, and no PCR products were detected in Actin control reactions that did not include the reverse transcription step (Figure 6). The presence of relatively similar levels of FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-2 RT-PCR products in cotyledons and leaves, however, was somewhat unexpected, given the relatively higher level of FAD7/8-2 expression detected by RNA-seq analysis of cotton leaves (Figure 4C). Since the latter experiments were performed on the 7th true leaf [59], we also measured omega-3 FAD transcript levels in leaves of this age, and observed a similar expression pattern as in the younger leaves and cotyledons (Figure 6B). While the reasons for the differences in relative expression levels measured by the two techniques are currently unknown, the results of the two approaches are at least consistent in that both reveal measurable levels of expression for both FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-2 genes. Possible explanations for the differences in gene expression include sensitivities of the two techniques employed (such as differences in primer amplification efficiencies that are not accounted for during semi-quantitative RT-PCR) and/or differences in plant growth conditions (chamber vs. greenhouse).

Figure 6.

Detection of omega-3 FAD transcripts in G. hirsutum leaves using semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The G. hirsutum cultivar TM-1 was grown in a growth chamber at 30°C with 12 h light/12 h dark cycles, then the first true leaves were collected on the 13th day after germination (A), or plants were grown until the 7th fully expanded leaf could be collected (B). Leaf samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored prior to use. RT-PCR analysis of cDNA was performed as described in the Methods, and samples were analyzed by DNA gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The target gene of each PCR reaction is listed along the top, and Actin reactions without reverse transcription were included as a negative control. M – DNA ladder, with positions of markers (in kbp) listed on the left. Note the similar expression of FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-2 genes in the 13-day-old leaves (A) and the 7th leaf (B).

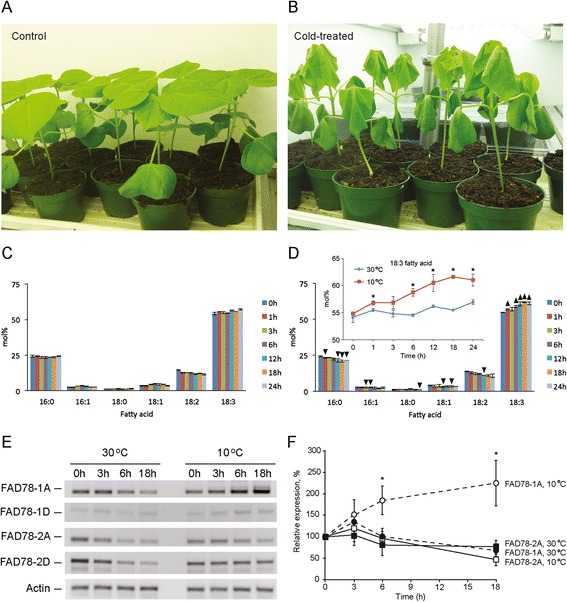

To determine whether any of the omega-3 fatty acid desaturase genes were induced in G. hirsutum seedlings in response to cold temperature, cotton seeds were germinated in pots in a growth chamber at 30°C with a 12 h/12 h day/night cycle and seedlings allowed to establish for 13 days. On the morning of the 14th day, a portion of the plants were moved to a different growth chamber held at 10°C, then leaf samples were collected from both control and cold-treated plants at various time points and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to use. As shown in Figure 7A and B, cotton seedlings exhibited pronounced wilting after just 6 hours of cold temperature exposure, which is similar to what had been observed previously [13]. Biochemical analysis of leaf fatty acid composition during cold temperature adaptation showed an increase in omega-3 fatty acids (18:3) and decrease in omega-6 fatty acids (18:2) in cold treated plants (Figure 7C and D), which is consistent with enhanced omega-3 FAD enzyme activity [25]. Measurement of omega-3 FAD gene expression patterns in control and cold-treated plants using RT-PCR revealed that the FAD7/8-1 gene expression increased significantly at 6 and 18 hours (Figure 7E and F), which generally correlated with the temporal increase in 18:3 fatty acids (compare Figure 7D and F). While FAD7/8-2 was not as dramatically induced, the expression level did appear to be somewhat altered by cold temperature treatment in comparison to the control. Notably, the patterns of gene expression for FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-2 were observed for both A and D subgenomic copies, suggesting relatively ancient, predominant establishment of FAD7/8-1 as a cold-responsive gene in cotton.

Figure 7.

Cold-temperature treatment of G. hirsutum seedlings. Plants were grown in a growth chamber at 30°C for 13 days, then a portion of the plants were transferred at the beginning of the 14th day to a similar chamber held at 10°C and the first true leaves were sampled for 24 hours for fatty acid and gene expression analysis. Images of plants grown at either 30°C (Control) (A) or 10°C (Cold-treated) (B) for 6 hours showed significant wilting of plant leaves at 10°C (B). Fatty acid composition of control (C) or cold-treated (D) plants was determined over a 24-hour period. Values represent the average and standard deviation of three biological replicates. Student’s t-test was used to compare percentages of each fatty acid between control and cold-treated samples. Solid, upward pointing arrowheads in panel (D) represent a statistically significant increase in fatty acid composition (p <0.05) in response to cold, while down arrowheads represent a decrease in response to cold (p <0.05). The inset in panel (D) shows a line graph of 18:3 fatty acid content at either 30 or 10°C (*, p <0.05). (E) Representative semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis showing prominent cold-induced expression of the FAD7/8-1 gene at 10°C (right side) compared to the 30°C control samples (left side). (F) Quantitative analysis of band intensities in panel (E) relative to t = 0 for the same temperature treatment revealed a statistically significant induction of FAD7/8-1A expression at 10°C (open circles, dashed line) in comparison to 30°C (closed circles, dashed line), while FAD7/8-2A was not induced by cold temperature (open squares, solid line) in comparison to the control (closed squares, solid line). Values represent the average and standard deviation of three biological replicates, and student’s t-test was used for comparison of the same gene at different temperatures. * denotes p <0.05.

Conclusions

Five omega-3 FAD-type genes were identified in cotton, two of which encode ER-localized enzymes (FAD3-1 and FAD3-2) and three that encode chloroplast-type enzymes (FAD7/8-1, FAD7/8-2 and FAD7/8-3) (Table 1; Figure 1). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the genes could be grouped into three major clades (Figure 2), the first of which contained all FAD3-type genes. Functional analysis revealed that the FAD3-1 gene is predominantly expressed in elongating cotton fibers (Figure 3) and likely contributes to the synthesis of linolenic acid, the most abundant fatty acid in fibers. The FAD3-2 gene is expressed at a relatively low level in all conditions examined here, and is duplicated in the A genome of G. herbaceum and A subgenome of G. hirsutum. This latter paralog also contains several in-frame stop codons (Additional file 6). Given the low expression of FAD3-2 compared to FAD3-1, it seems likely that FAD3-1 plays a more dominant role in production of linolenic acid in the ER of cotton cells. Clade 2 contains the FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-3 genes (Figure 2), and RNA-seq and semi-quantitative RT-PCR showed that FAD7/8-1 is induced by abiotic stress, including drought treatment in roots (Figure 5B), and cold treatment in cotton leaves (Figure 7E and F). The FAD7/8-3 gene is expressed at a relatively low level in all experiments described here and includes a substitution mutation in a highly conserved region of the encoded polypeptide sequence (Figure 1). The third clade includes the FAD7/8-2 gene, which likely serves more of a housekeeping role for production of 18:3 in cotyledons (Additional file 12B), leaves (Figure 4 and Additional file 10D), and petals (Figure 4 and Additional file 10C). Unlike FAD7/8-1, the FAD7/8-2 gene did not show pronounced induction by abiotic stress in response to either drought (Figure 5A) or cold temperature treatment (Figure 7E and F). Notably, the Arabidopsis FAD7 and FAD8 genes also show differential response to chilling treatment, with FAD7 expression unaffected by cold temperature [64] while FAD8 expression is induced at low temperature [65]. Taken together, these data define the evolutionary and functional properties of the omega-3 FAD gene family in cotton and identify specific members of the gene family associated with fiber biogenesis and abiotic stress response.

Methods

Gene cloning and annotation

For the initial search of omega-3 FAD genes in cotton, we employed several different approaches including i) BLAST analysis of extant Gossypium sequences in various genome databases (e.g., NCBI, CottonDB, Phytozome) using Arabidopsis thaliana omega-3 desaturases as queries; ii) PCR-based screening of cotton genomic DNA and cDNA libraries using “degenerate” PCR primers corresponding to conserved regions of omega-3 fatty acid polypeptide sequences; and iii) PCR amplification using gene-specific primers (see Additional file 1 for primer sequences). Genomic DNA from G. herbaceum, G. raimondii, G. hirsutum, and G. barbadense was used as templates in PCR reactions. Additional insight to the omega-3 FAD gene family was obtained with the release of the genome sequence for the diploid progenitor G. raimondii [47].

Our preliminary analysis identified five different omega-3 desaturase genes in cotton, including two genes encoding putative endoplasmic reticulum-localized enzyme (FAD3-1 and FAD3-2), and three genes encoding putative chloroplast-localized enzymes (FAD7/8-1, FAD7/8-2, FAD7/8-3). Each of the five genes was subsequently cloned and sequenced from two progenitor-type cotton species, G. herbaceum (A genome; PI 175456) and G. raimondii (D genome; PI 530901), as well as from modern upland cotton, G. hirsutum TM1 (AD tetraploid; PI 662944 MAP; [66]). To ensure fidelity of cloned gene sequences, the following strategy was employed. Gene-specific PCR primers were designed to hybridize in the 5′ and 3′ UTR regions near the start and stop codons, respectively, and used in PCR reactions containing genomic DNA isolated from a single plant from each species. The PCR reaction was divided into three aliquots that were each subjected to PCR amplification using a gradient of annealing temperatures, and extension times appropriate for each gene. The high fidelity polymerase “Phusion” (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) was used for amplification. PCR products were resolved on DNA gels and bands of expected size were extracted and purified using the GeneClean kit (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) and ligated into appropriate plasmid vectors. In some cases, blunt-ended PCR products were subcloned into pZero-Blunt (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), while in other cases, unique restrictions sites were added to the 5’ and 3’ ends of gene-specific primers to allow for directional subcloning into pUC19.

Ten individual plasmids derived from each of the three initial PCR reactions for a single gene (30 plasmids total), were subject to DNA sequencing (Retrogen, Inc., San Diego, CA), with DNA sequences determined in both the forward and reverse directions (see Additional file 2 for sequencing primers). Full-length gene sequences were assembled using the ContigExpress module of Vector NTI (v 11.0; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The sequences of all thirty plasmids representing a single gene target were aligned to help identify sequencing artifacts, PCR-based artifacts, and gene sequences resulting from PCR-based recombination. The latter artifact is quite common when amplifying a gene from a polyploid plant, such as G. hirsutum [67], and involves essentially random crossing over of homoeologous sequence templates during PCR amplification. Knowledge of the omega-3 FAD gene sequences from the diploid progenitor species was essential for helping to determine the homoeologous gene sequences in tetraploid G. hirsutum. Intron/exon assignments were determined by aligning the genomic sequences with cotton FAD cDNAs or ESTs, if available, or predicting splice sites using algorithms available at www.softberry.com and comparison to well characterized sequences of Arabidopsis omega-3 desaturases. All of the gene sequences, as well as putative mRNA sequences, from G. herbaceum, G. raimondii, and G. hirsutum were deposited in GenBank and accession numbers are provided in Additional file 4.

Phylogenetic analysis

The 22 full-length omega-3 FAD gene sequences identified in this study, as well as 3 homologous sequences from the T. cacao genome (Additional file 4) were aligned with T-Coffee (v10.0; [68]) using default parameters. The multiple sequence alignment was subsequently cleaned using Gblocks [69] to remove poorly aligned and predominantly gap-containing regions, using the following parameters: a minimum of 15 sequences were required for a conserved position and a flank position, no limit was placed on the number of contiguous nonconserved positions, at least two nucleotides were required for a conserved block, and gaps were allowed in at most 14 taxa at a given position. An unrooted phylogenetic tree was generated using the maximum likelihood method implemented in the online version of the PhyML program (http://www.atgc-montpellier.fr/phyml v3.0; [70]) using a BioNJ [71] initial tree and a GTR + gamma nucleotide substitution model with parameters inferred from the data. Branch support was estimated using the aLRT method [72]. The tree was visualized and annotated using FigTree (v1.4; http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree). For visualization purposes, the tree was mid-point rooted.

Evaluation of gene expression using RNA-seq and semi-quantitative RT-PCR

RNA-seq measurements of gene expression were mined from several cotton RNA-seq studies [56,59,60] that sampled fiber, leaf, and petal tissues. RNA-seq expression levels of the FAD genes in developing seeds were obtained from R. Hovav and J. Wendel (personal communication). RNA-seq data for the drought experiment were obtained from [61]. The omega-3 FAD genes identified in this study were aligned against the D-genome reference sequence [47] using GSNAP [73] in order to identify the corresponding gene models, and RPKM (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads) measurements corresponding to the appropriate gene model were extracted from the published data.

For semi-quantitative RT-PCR, gene-specific primers were designed by aligning the homoeologous sequences of omega-3 desaturases from G. hirsutum to identify SNPs and indels that were specific to each gene (see Additional files 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9). The specificity of primer binding was then evaluated using PCR and plasmid templates harboring either the target gene or the closest related homoeolog. Optimal annealing temperatures for each primer pair were determined using gradient annealing PCR conditions. In some cases, amplification was observed using both plasmid templates, at all annealing temperatures, and primers were subsequently re-designed to bind to other gene-specific regions and specificity tested. All final primer sets showed homoeolog-specific amplification from plasmid DNA templates at the indicated optimal annealing temperatures (see Additional files 11 and 12).

To evaluate transcript abundance using RT-PCR, total RNA was extracted from frozen leaf tissue using the Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) then cDNA was constructed using 1 μg of total RNA and the iScript kit, as described by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Additional reactions were set up with iScript RT supermix, but without reverse transcriptase, to control for potential genomic DNA contamination. Semi-quantitative PCR was conducted using Extract-N-Amp PCR Ready Mix (Sigma-Aldrich) programmed with 1 μl of cDNA template (corresponding to 50 ng of RNA/cDNA) and each FAD gene primer pair, or 0.1 μl of cDNA template (corresponding to 5 ng of RNA/cDNA) and actin gene primers. These amounts of plasmid DNA template, as well as number of cycles, were determined empirically for each gene to ensure that amplification was within the linear range. The PCR included the following program conditions: initial hold at 98°C for 30 sec, then 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 sec, annealing at the appropriate Tm for each primer pair (determined as described above) for 30 sec, then extension at 72°C for the period determined for each PCR product. After the 30th cycle, reactions were incubated at 72°C for an additional 5 min to complete extension then held at 4°C, followed by storage at −20°C. Four μl of 6X loading dye was added to the 20 μl PCR reactions, then 10 μl of each sample was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Gel images were captured using a FUJI LAS-4000 imaging system and band intensities were quantified using MultiGauge V3.1 software.

Plant growth conditions and sample collections

Cotton seeds were planted in damp soil in 24×16×16 plastic pots (1 seed per pot), covered with a plastic dome, and placed in a growth chamber programmed with a 12 h/12 h day/night cycle at 30°C, 60% relative humidity, and 2.14 Kfc light intensity. Plants were watered twice a week, and fertilized with 20-20-20 once a week. 13-day-old plants were subjected to chilling treatment (10°C) at the beginning of the 14th light/dark cycle. The control group of plants remained at 30°C for the 14th cycle. The first true leaf was collected at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 h after the start of the cold treatment for both treatment and control groups and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until used. Three biological reps were collected for each time point.

Lipid extraction and GC/FID analysis

Total lipids were extracted from the leaf tissues using a modified Bligh and Dyer method [74]. Briefly, frozen leaves were placed in a glass tube with 3 ml of preheated (75°C) isopropanol and incubated for 15 min. After the samples cooled to room temperature, 1.5 ml of chloroform and 0.6 ml of water were added. The samples were vigorously shaken, and the lipids were extracted for 1 h at RT. The extracts were transferred to clean glass tubes. To these, 1.5 ml of chloroform and 1.5 ml of 1 M KCl were added, and the samples were vigorously shaken. After centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 3 min the upper phase was discarded and the organic phase was washed once with 2 ml of water. After centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 3 min the organic (bottom) phase was transferred to a clean tube, dried down under a gentle stream of nitrogen and used for FA transmethylation. 1 ml of methanol HCl (1.25 M) was added to the dried lipid extract. Samples were vortexed and incubated at 80°C for 1 h. Tubes were allowed to cool to room temperature and reactions were terminated with 1 ml of 0.9% NaCl aqueous solution. After addition of 1 ml of hexane the samples were shaken, then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 1 min to facilitate the phase separation. The upper phase (organic) containing FAMEs was transferred to GC vials. FAME samples were analyzed using an Agilent HP 6890 Series GC system equipped with 7683 Series Injector and autosampler. FAME samples were injected on BPX70 (SGE Analytical Science, Ringwood Victoria, Australia) capillary column (10 m × 0.1 mm × 0.2 um) with 50:1 split ratio and separated with constant pressure 25 psi and a temperature program: hold at 145°C for 5 min, 145–175°C at 2°C/min, hold 175°C for 1 min, 175–250°C at 30°C/min. Integration events were detected between 9 and 20 min and identified by comparing to GLC-10 FAME standard mix (Sigma).

Accession numbers

All accession numbers for genes described in this study are provided in Additional file 4.

Availability of supporting data

The sequence data supporting the results of this article are available in the GenBank [GenBank; Gossypium species: KF460111-KF460114, KF460117-KF460154, KF572120-KF572121; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/] and Phytozome [Phytozome; Arabidopsis thaliana: AT2G29980.1, AT3G11170.1, AT5G05580.1; Theobroma cacao: Thecc1EG041603t1, Thecc1EG021677t1, Thecc1EG042487t1; http://www.phytozome.net/] repositories. The phylogenetic datasets are available at the LabArchives repository [http://dx.doi.org/10.6070/H4WS8R7Q].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, BER Division (Grant No. DE-FG02-09ER64812/DE-SC0000797) to KDC and JMD, USDA-NIFA/DOE Biomass Research and Development Initiative (BRDI) Grant No. 2012–10006 to MAG and MAJ, NSF (0817707) and Cotton Inc. (09–559) grants to JAU, and Cotton Inc. grant 12–157 to JMD. The authors thank Saumya Bollam, T.J. Lentz, Judy Nguyen, and Lauren Tomlin for assistance with gene cloning.

Additional files

Gene cloning primers.

DNA sequencing primers.

RT-PCR primers used for measuring homoeologous gene expression in G. hirsutum.

GenBank accession numbers.

Alignment of FAD3-1 gene sequences from G. herbaceum (A diploid), G. raimondii (D diploid), and G. hirsutum (AD tetraploid). The sequences of each gene were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/; [75]). The start and stop codons are highlighted in bold, and exons are underlined. Gene cloning primers are highlighted in yellow, and in some cases, restriction sites, highlighted in magenta, were included in the sequence to help facilitate subcloning. The name of each forward primer is provided between the gene name and start of the nucleotide sequence, and reverse primers are listed immediately after the end of the nucleotide sequence. The primers used for RT-PCR analysis of gene expression are highlighted green for the A homoeolog of G. hirsutum, while the D homoeolog primers are highlighted in blue. The names of all RT-PCR primers are listed above the highlighted sequence, and the arrows indicate whether they are forward or reverse primers. The nucleotide sequences highlighted for all reverse primers correspond to their forward sequence positions. The actual nucleotide sequence of all primers, listed 5’ to 3’, is provided in Additional files 1 and 2.

Alignment of FAD3-2 gene sequences from G. herbaceum (A diploid), G. raimondii (D diploid), and G. hirsutum (AD tetraploid). The sequences of each gene were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/; [75]). The start and stop codons are highlighted in bold, and exons are underlined. The in-frame stop codons in FAD3-2.2 genes are highlighted in red. Gene cloning primers are highlighted in yellow, and in some cases, restriction sites, highlighted in magenta, were included in the sequence to help facilitate subcloning. The name of each forward primer is provided between the gene name and start of the nucleotide sequence, and reverse primers are listed immediately after the end of the nucleotide sequence. The primers used for RT-PCR analysis of gene expression are highlighted green for the A homoeolog of G. hirsutum, while the D homoeolog primers are highlighted in blue. The names of all RT-PCR primers are listed above the highlighted sequence, and the arrows indicate whether they are forward or reverse primers. The nucleotide sequences highlighted for all reverse primers correspond to their forward sequence positions. The actual nucleotide sequence of all primers, listed 5’ to 3’, is provided in Additional files 1 and 2.

Alignment of FAD7/8-1 gene sequences from G. herbaceum (A diploid), G. raimondii (D diploid), and G. hirsutum (AD tetraploid). The sequences of each gene were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/; [75]). The start and stop codons are highlighted in bold, and exons are underlined. Gene cloning primers are highlighted in yellow, and in some cases, restriction sites, highlighted in magenta, were included in the sequence to help facilitate subcloning. The name of each forward primer is provided between the gene name and start of the nucleotide sequence, and reverse primers are listed immediately after the end of the nucleotide sequence. The primers used for RT-PCR analysis of gene expression are highlighted green for the A homoeolog of G. hirsutum, while the D homoeolog primers are highlighted in blue. The names of all RT-PCR primers are listed above the highlighted sequence, and the arrows indicate whether they are forward or reverse primers. The nucleotide sequences highlighted for all reverse primers correspond to their forward sequence positions. The actual nucleotide sequence of all primers, listed 5’ to 3’, is provided in Additional files 1 and 2.

Alignment of FAD7/8-2 gene sequences from G. herbaceum (A diploid), G. raimondii (D diploid), and G. hirsutum (AD tetraploid). The sequences of each gene were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/; [75]). The start and stop codons are highlighted in bold, and exons are underlined. Gene cloning primers are highlighted in yellow, and in some cases, restriction sites, highlighted in magenta, were included in the sequence to help facilitate subcloning. The name of each forward primer is provided between the gene name and start of the nucleotide sequence, and reverse primers are listed immediately after the end of the nucleotide sequence. The primers used for RT-PCR analysis of gene expression are highlighted green for the A homoeolog of G. hirsutum, while the D homoeolog primers are highlighted in blue. The names of all RT-PCR primers are listed above the highlighted sequence, and the arrows indicate whether they are forward or reverse primers. The nucleotide sequences highlighted for all reverse primers correspond to their forward sequence positions. The actual nucleotide sequence of all primers, listed 5’ to 3’, is provided in Additional files 1 and 2.

Alignment of FAD7/8-3 gene sequences from G. herbaceum (A diploid), G. raimondii (D diploid), and G. hirsutum (AD tetraploid). The sequences of each gene were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/; [75]). The start and stop codons are highlighted in bold, and exons are underlined. Gene cloning primers are highlighted in yellow, and in some cases, restriction sites, highlighted in magenta, were included in the sequence to help facilitate subcloning. The name of each forward primer is provided between the gene name and start of the nucleotide sequence, and reverse primers are listed immediately after the end of the nucleotide sequence. The primers used for RT-PCR analysis of gene expression are highlighted green for the A homoeolog of G. hirsutum, while the D homoeolog primers are highlighted in blue. The names of all RT-PCR primers are listed above the highlighted sequence, and the arrows indicate whether they are forward or reverse primers. The nucleotide sequences highlighted for all reverse primers correspond to their forward sequence positions. The actual nucleotide sequence of all primers, listed 5’ to 3’, is provided in Additional files 1 and 2.

RNA-seq analysis of omega-3 FAD gene expression in cotton fiber, seeds, petals and leaves. (A) Fibers were harvested from the indicated cotton varieties at 10 and 20 DPA, which represents primary and secondary cell wall synthesis, respectively, then RNA-seq analysis was performed as described [56]. Cotton varieties are indicated along the bottom. (B) Developing seeds were harvested from the indicated cotton varieties at 10, 20, 30, or 40 DPA then RNA-seq analysis was performed as described. Similar RNA-seq analyses were performed on cotton petals (C) and leaves (D), from the indicated plant lines [59,60]. Transcripts were quantified as “reads per kilobase per million mapped reads” (RPKM). For simplicity, data for A and D homoeologous sequences were combined. Values represent average and standard deviation of three biological replicates. For data presented in panels (C) and (D), student’s t-test was used for comparison of FAD7/8-1 to FAD7/8-2, and * denotes p <0.05.

Primer optimization for FAD3-type genes in G. hirsutum. The gene targets and primer pairs are listed on the left. Primer sequences are described in Additional file 3. PCR reactions were programmed with plasmid DNA containing either the target gene or the closest related homoeolog (listed beneath each gel picture). A gradient of annealing temperatures, with values listed above each gel, was used during the PCR reactions, then an equal volume of each reaction was analyzed by DNA gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The optimal anneal temperature for each primer pair, where DNA fragments can be detected for the target gene, but not the homoeolog, is reported to the right. Also listed on the right are the expected sizes of PCR fragments amplified from either genomic DNA or mRNA. Note that the plasmid DNA templates contained genomic copies of each gene, and bands of expected sizes were obtained for all PCR reactions (DNA ladder not shown).

Primer optimization for FAD7/8-type genes in G. hirsutum. (A) The gene targets and primer pairs are listed on the left. Primer sequences are described in Additional file 3. PCR reactions were programmed with plasmid DNA containing either the target gene or the closest related homoeolog, as indicated above each column of gel pictures. A gradient of annealing temperatures, with values listed immediately above the gel pictures, was used during the PCR reactions, then an equal volume of each reaction was analyzed by DNA gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The optimal anneal temperature for each primer pair, where DNA fragments could be detected for the target gene, but not the homoeolog, is reported to the right. Also listed are the expected sizes of PCR fragments amplified from either genomic DNA or mRNA. Note that the plasmid DNA templates contained genomic copies of each gene, and bands of expected sizes were obtained for all PCR reactions (DNA ladder not shown). (B) RT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from 12-day-old G. hirsutum cotyledons, showing that FAD7/8-1 and FAD7/8-2 genes, from both subgenomes, are predominantly expressed. Bands of expected sizes, as amplified from cDNA and not genomic DNA, were detected, and no bands were observed in the actin control when PCR reactions were programmed with RNA that was not subjected to reverse transcription (no RT).

Footnotes

Olga P Yurchenko and Sunjung Park contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

OPY carried out cold-temperature analysis of cotton plants including biochemical analysis of plant lipids and measurement of gene expression. SP, JJI and JCM performed all gene cloning and DNA sequence analysis. DCI performed evolutionary analysis. ZL, JTP, and JAU conducted RNA-seq analysis. MAJ, KDC and MAG participated in design and coordination of experiments and helped draft the paper. JMD conceived the study, coordinated the project, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Olga P Yurchenko, Email: Olga.Yurchenko@ars.usda.gov.

Sunjung Park, Email: Sunjung.Park@ars.usda.gov.

Daniel C Ilut, Email: dci1@cornell.edu.

Jay J Inmon, Email: bluebass86@gmail.com.

Jon C Millhollon, Email: jon.millhollon@gmail.com.

Zach Liechty, Email: zliechty@gmail.com.

Justin T Page, Email: jtpage68@gmail.com.

Matthew A Jenks, Email: majenks@mail.wvu.edu.

Kent D Chapman, Email: chapman@unt.edu.

Joshua A Udall, Email: jaudall1@gmail.com.

Michael A Gore, Email: mag87@cornell.edu.

John M Dyer, Email: John.Dyer@ars.usda.gov.

References

- 1.Wendel JF, Brubaker CL, Seelanan T. The origin and evolution of Gossypium. In: Stewart JM, Oosterhuis DM, Heitholt JJ, Mauney JR, editors. Physiology of Cotton. Netherlands: Springer; 2010. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendel JF, Brubaker C, Alvarez I, Cronn R, Stewart JM. Evolution and Natural History of The Cotton Genus. In: Paterson AH, editor. Genetics and Genomics of Cotton. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendel JF, Cronn RC. Polyploidy and the evolutionary history of cotton. Adv Agron. 2003;78:139–186. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(02)78004-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wendel JF. New World tetraploid cottons contain Old World cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:4132–4136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wendel JF, Albert VA. Phylogenetics of the cotton genus (Gossypium): character-state weighted parsimony analysis of chloroplast-DNA restriction site data and its systematic and biogeographic implications. Syst Bot. 1992;17:115–143. doi: 10.2307/2419069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hovav R, Chaudhary B, Udall JA, Flagel L, Wendel JF. Parallel domestication, convergent evolution and duplicated gene recruitment in allopolyploid cotton. Genetics. 2008;179:1725–1733. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.089656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gipson JR. Temperature effects on growth, development and fiber properties. In: Mauney JR, Stewart JM, editors. Cotton Physiology. Memphis, TN: The Cotton Foundation; 1986. pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warner DA, Holaday AS, Burke JJ. Response of carbon metabolism to night temperature in cotton. Agron J. 1995;87:1193–1197. doi: 10.2134/agronj1995.00021962008700060026x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradow JM, Davidonis GH. Effects of Environment on Fiber Quality. In: Stewart JM, Oosterhuis DM, Heitholt JJ, Mauney JR, editors. Physiology of Cotton. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2010. pp. 229–245. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cothren J. Physiology of the Cotton Plant. In: Smith CW, Cothren J, editors. Cotton: Origin, History, Technology, and Production. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. pp. 207–268. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bange MP, Milroy SP. Impact of short-term exposure to cold night temperatures on early development of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Aust J Agric Res. 2004;55:655–664. doi: 10.1071/AR03221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradow JM. Cotton cultivar responses to suboptimal postemergent temperatures. Crop Sci. 1991;31:1595–1599. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1991.0011183X003100060043x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeRidder BP, Crafts-Brandner SJ. Chilling stress response of postemergent cotton seedlings. Physiol Plantarum. 2008;134:430–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesketh JD, Low AJ. The effects of temperature on components of yield and fibre quality of cotton varieties of diverse origins. Cotton Grow Rev. 1968;45:243–257. [Google Scholar]

- 15.St John JB, Christiansen MN. Inhibition of linolenic acid synthesis and modification of chilling resistance in cotton seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1976;57:257–259. doi: 10.1104/pp.57.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guy C, Kaplan F, Kopka J, Selbig J, Hincha DK. Metabolomics of temperature stress. Physiol Plantarum. 2008;132:220–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iba K. Acclimative response to temperature stress in higher plants: approaches of gene engineering for temperature tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:225–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100201.160729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight MR, Knight H. Low-temperature perception leading to gene expression and cold tolerance in higher plants. New Phytol. 2012;195:737–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu J, Dong CH, Zhu JK. Interplay between cold-responsive gene regulation, metabolism and RNA processing during plant cold acclimation. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guschina IA, Harwood JL. Mechanisms of temperature adaptation in poikilotherms. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5477–5483. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martz F, Kiviniemi S, Palva TE, Sutinen ML. Contribution of omega-3 fatty acid desaturase and 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase II (KASII) genes in the modulation of glycerolipid fatty acid composition during cold acclimation in birch leaves. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:897–909. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishida I, Murata N. Chilling sensitivity in plants and cyanobacteria: the crucial contribution of membrane lipids. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:541–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams JP, Khan MU, Mitchell K, Johnson G. The effect of temperature on the level and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids in diacylglycerols of Brassica napus leaves. Plant Physiol. 1988;87:904–910. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.4.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hazel JR, Williams EE. The role of alterations in membrane lipid composition in enabling physiological adaptation of organisms to their physical environment. Prog Lipid Res. 1990;29:167–227. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(90)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rikin A, Dillwith JW, Bergman DK. Correlation between the circadian rhythm of resistance to extreme temperatures and changes in fatty acid composition in cotton seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:31–36. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall TD, Chastain DR, Horn PJ, Chapman KD, Choinski JS., Jr Changes during leaf expansion of PhiPSII temperature optima in Gossypium hirsutum are associated with the degree of fatty acid lipid saturation. J Plant Physiol. 2014;171:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohlrogge J, Browse J. Lipid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:957–970. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin BA, Schoper JB, Rinne RW. Changes in soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.) glycerolipids in response to water stress. Plant Physiol. 1986;81:798–801. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.3.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torres-Franklin M-L, Repellin A, Huynh V-B, d'Arcy-Lameta A, Zuily-Fodil Y, Pham-Thi A-T. Omega-3 fatty acid desaturase (FAD3, FAD7, FAD8) gene expression and linolenic acid content in cowpea leaves submitted to drought and after rehydration. Environ Exp Bot. 2009;65:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dominguez T, Hernandez ML, Pennycooke JC, Jimenez P, Martinez-Rivas JM, Sanz C, Stockinger EJ, Sanchez-Serrano JJ, Sanmartin M. Increasing omega-3 desaturase expression in tomato results in altered aroma profile and enhanced resistance to cold stress. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:655–665. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.154815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khodakovskaya M, McAvoy R, Peters J, Wu H, Li Y. Enhanced cold tolerance in transgenic tobacco expressing a chloroplast omega-3 fatty acid desaturase gene under the control of a cold-inducible promoter. Planta. 2006;223:1090–1100. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kodama H, Hamada T, Horiguchi G, Nishimura M, Iba K. Genetic enhancement of cold tolerance by expression of a gene for chloroplast [omega]-3 fatty acid desaturase in transgenic tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:601–605. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kodama H, Horiguchi G, Nishiuchi T, Nishimura M, Iba K. Fatty acid desaturation during chilling acclimation is one of the factors involved in conferring low-temperature tolerance to young tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:1177–1185. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.4.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu C, Wang HS, Yang S, Tang XF, Duan M, Meng QW. Overexpression of endoplasmic reticulum omega-3 fatty acid desaturase gene improves chilling tolerance in tomato. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009;47:1102–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang M, Barg R, Yin M, Gueta-Dahan Y, Leikin-Frenkel A, Salts Y, Shabtai S, Ben-Hayyim G. Modulated fatty acid desaturation via overexpression of two distinct omega-3 desaturases differentially alters tolerance to various abiotic stresses in transgenic tobacco cells and plants. Plant J. 2005;44:361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bocianowski J, Mikolajczyk K, Bartkowiak-Broda I. Determination of fatty acid composition in seed oil of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) by mutated alleles of the FAD3 desaturase genes. J Appl Genet. 2012;53:27–30. doi: 10.1007/s13353-011-0062-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu X, Sullivan-Gilbert M, Gupta M, Thompson SA. Mapping of the loci controlling oleic and linolenic acid contents and development of fad2 and fad3 allele-specific markers in canola (Brassica napus L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2006;113:497–507. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian E, Zeng F, MacKay K, Roslinsky V, Cheng B. Detection and molecular characterization of two FAD3 genes controlling linolenic acid content and development of allele-specific markers in yellow mustard (Sinapis alba) PLoS One. 2014;9:e97430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Q, Fan C, Guo Z, Qin J, Wu J, Li Q, Fu T, Zhou Y. Identification of FAD2 and FAD3 genes in Brassica napus genome and development of allele-specific markers for high oleic and low linolenic acid contents. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:715–729. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1863-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kargiotidou A, Deli D, Galanopoulou D, Tsaftaris A, Farmaki T. Low temperature and light regulate delta 12 fatty acid desaturases (FAD2) at a transcriptional level in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) J Exp Bot. 2008;59:2043–2056. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Q, Brubaker CL, Green AG, Marshall DR, Sharp PJ, Singh SP. Evolution of the FAD2-1 fatty acid desaturase 5' UTR intron and the molecular systematics of Gossypium (Malvaceae) Am J Bot. 2001;88:92–102. doi: 10.2307/2657130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Q, Singh SP, Brubaker CL, Sharp PJ, Green AG, Marshall DR. Molecular cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding a microsomal w-6 fatty acid desaturase from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) Aust J Agric Res. 1999;26:101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Q, Singh SP, Green AG. High-stearic and high-oleic cottonseed oils produced by hairpin RNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene silencing. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1732–1743. doi: 10.1104/pp.001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pirtle IL, Kongcharoensuntorn W, Nampaisansuk M, Knesek JE, Chapman KD, Pirtle RM. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the gene for a cotton Delta-12 fatty acid desaturase (FAD2) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1522:122–129. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(01)00312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sunikumar G, Campbell LM, Hossen M, Connell JP, Hernandez E, Reddy AS, Smith CW, Rathore KS. A comprehensive study of the use of a homologous promoter in antisense cotton lines exhibiting a high seed oleic acid phenotype. J Plant Biotechnol. 2005;3:319–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2005.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang D, Pirtle IL, Park SJ, Nampaisansuk M, Neogi P, Wanjie SW, Pirtle RM, Chapman KD. Identification and expression of a new delta-12 fatty acid desaturase (FAD2-4) gene in upland cotton and its functional expression in yeast and Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009;47:462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paterson AH, Wendel JF, Gundlach H, Guo H, Jenkins J, Jin D, Llewellyn D, Showmaker KC, Shu S, Udall J, Yoo MJ, Byers R, Chen W, Doron-Faigenboim A, Duke MV, Gong L, Grimwood J, Grover C, Grupp K, Hu G, Lee TH, Li J, Lin L, Liu T, Marler BS, Page JT, Roberts AW, Romanel E, Sanders WS, Szadkowski E, et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature. 2012;492:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature11798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li F, Fan G, Wang K, Sun F, Yuan Y, Song G, Li Q, Ma Z, Lu C, Zou C, Chen W, Liang X, Shang H, Liu W, Shi C, Xiao G, Gou C, Ye W, Xu X, Zhang X, Wei H, Li Z, Zhang G, Wang J, Liu K, Kohel RJ, Percy RG, Yu JZ, Zhu YX, Wang J, et al. Genome sequence of the cultivated cotton Gossypium arboreum. Nature Genet. 2014;46:567–572. doi: 10.1038/ng.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shanklin J, Whittle E, Fox BG. Eight histidine residues are catalytically essential in a membrane-associated iron enzyme, stearoyl-CoA desaturase, and are conserved in alkane hydroxylase and xylene monooxygenase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12787–12794. doi: 10.1021/bi00209a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabetta W, Blanco A, Zelasco S, Lombardo L, Perri E, Mangini G, Montemurro C. Fad7 gene identification and fatty acids phenotypic variation in an olive collection by EcoTILLING and sequencing approaches. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013;69:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Broadwater JA, Whittle E, Shanklin J. Desaturation and hydroxylation. Residues 148 and 324 of Arabidopsis FAD2, in addition to substrate chain length, exert a major influence in partitioning of catalytic specificity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15613–15620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, von Heijne G. ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Protein Sci. 1999;8:978–984. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.5.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Argout X, Salse J, Aury JM, Guiltinan MJ, Droc G, Gouzy J, Allegre M, Chaparro C, Legavre T, Maximova SN, Abrouk M, Murat F, Fouet O, Poulain J, Ruiz M, Roguet Y, Rodier-Goud M, Barbosa-Neto JF, Sabot F, Kudrna D, Ammiraju JS, Schuster SC, Carlson JE, Sallet E, Schiex T, Dievart A, Kramer M, Gelley L, Shi Z, Bérard A, et al. The genome of Theobroma cacao. Nature Genet. 2011;43:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ng.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Senchina DS, Alvarez I, Cronn RC, Liu B, Rong J, Noyes RD, Paterson AH, Wing RA, Wilkins TA, Wendel JF. Rate variation among nuclear genes and the age of polyploidy in Gossypium. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:633–643. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoo MJ, Wendel JF. Comparative evolutionary and developmental dynamics of the cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) fiber transcriptome. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qin YM, Hu CY, Pang Y, Kastaniotis AJ, Hiltunen JK, Zhu YX. Saturated very-long-chain fatty acids promote cotton fiber and Arabidopsis cell elongation by activating ethylene biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3692–3704. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dowd MK, Boykin DL, Meredith WR, Jr, Campbell BT, Bourland FM, Gannaway JR, Glass KM, Zhang J. Fatty acid profiles of cottonseed genotypes from the national cotton variety trials. J Cotton Sci. 2010;14:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoo MJ, Szadkowski E, Wendel JF. Homoeolog expression bias and expression level dominance in allopolyploid cotton. Heredity. 2013;110:171–180. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2012.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rambani A, Page JT, Udall JA. Polyploidy and the petal transcriptome of Gossypium. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bowman MJ, Park W, Bauer PJ, Udall JA, Page JT, Raney J, Scheffler BE, Jones DC, Campbell BT. RNA-Seq transcriptome profiling of upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) root tissue under water-deficit stress. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Myles S, Peiffer J, Brown PJ, Ersoz ES, Zhang Z, Costich DE, Buckler ES. Association mapping: critical considerations shift from genotyping to experimental design. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2194–2202. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu C, Gore M, Buckler ES, Yu J. Status and prospects of association mapping in plants. Plant Gen. 2008;1:5–20. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2008.02.0089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iba K, Gibson S, Nishiuchi T, Fuse T, Nishimura M, Arondel V, Hugly S, Somerville C. A gene encoding a chloroplast omega-3 fatty acid desaturase complements alterations in fatty acid desaturation and chloroplast copy number of the fad7 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24099–24105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gibson S, Arondel V, Iba K, Somerville C. Cloning of a temperature-regulated gene encoding a chloroplast omega-3 desaturase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1615–1621. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gore MA, Percy RG, Zhang J, Fang DD, Cantrell RG. Registration of the TM-1/NM24016 cotton recombinant inbred mapping population. J Plant Reg. 2012;6:124–127. doi: 10.3198/jpr2011.06.0334crmp. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cronn R, Cedroni M, Haselkorn T, Grover C, Wendel JF. PCR-mediated recombination in amplification products derived from polyploid cotton. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;104:482–489. doi: 10.1007/s001220100741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gascuel O. BIONJ: an improved version of the NJ algorithm based on a simple model of sequence data. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:685–695. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu TD, Nacu S. Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:873–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]