Abstract

Background and Purpose

Ginsenosides are bioactive saponins derived from Panax notoginseng roots (Sanqi) and ginseng. Here, the molecular mechanisms governing differential pharmacokinetics of 20(S)-protopanaxatriol-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 and 20(S)-protopanaxadiol-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd were elucidated.

Experimental Approach

Interactions of ginsenosides with human and rat hepatobiliary transporters were characterized at the cellular and vesicular levels. A rifampin-based inhibition study in rats evaluated the in vivo role of organic anion-transporting polypeptide (Oatp)1b2. Plasma protein binding was assessed by equilibrium dialysis. Drug–drug interaction indices were calculated to estimate potential for clinically relevant ginsenoside-mediated interactions due to inhibition of human OATP1Bs.

Key Results

All the ginsenosides were bound to human OATP1B3 and rat Oatp1b2 but only the 20(S)-protopanaxatriol-type ginsenosides were transported. Human multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP)2/breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)/bile salt export pump (BSEP)/multidrug resistance protein-1 and rat Mrp2/Bcrp/Bsep also mediated the transport of the 20(S)-protopanaxatriol-type ginsenosides. Glomerular-filtration-based renal excretion of the 20(S)-protopanaxatriol-type ginsenosides was greater than that of the 20(S)-protopanaxadiol-type counterparts due to differences in plasma protein binding. Rifampin-impaired hepatobiliary excretion of the 20(S)-protopanaxatriol-type ginsenosides was effectively compensated by the renal excretion in rats. The 20(S)-protopanaxadiol-type ginsenosides were potent inhibitors of OATP1B3.

Conclusion and Implications

Differences in hepatobiliary and in renal excretory clearances caused markedly different systemic exposure and different elimination kinetics between the two types of ginsenosides. Caution should be exercised with the long-circulating 20(S)-protopanaxadiol-type ginsenosides as they could induce hepatobiliary herb–drug interactions, particularly when patients receive long-term therapies with high-dose i.v. Sanqi or ginseng extracts.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| Transporters | |

| BCRP, breast cancer resistance protein, ABCG2 | |

| BSEP, bile salt export pump, ABCB11 | |

| MDR1, multidrug resistance protein, ABCB1 | |

| MRP2, multidrug resistance-associated protein, ABCC2 | |

| OATP1B1, organic anion-transporting polypeptide, SLCO1B1 | |

| OATP1B3, organic anion-transporting polypeptide, SLCO1B3 |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| Oestrone-3-sulfate |

| Rifampin |

| MTX, methotrexate |

| TCA, taurocholic acid |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

The root of Panax notoginseng (Sanqi in Chinese) is a clinically important cardiovascular herb. It is extensively used both alone and in combination with other herbs, such as the root of Salvia miltiorrhiza (Danshen), for patients with coronary artery disease (Ng, 2006; Jia et al., 2012; Shang et al., 2013). Ginsenosides are pharmacologically relevant to Sanqi therapies because they have multiple bioactivities, including vasodilatation, hypolipidaemic effects, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties (Lü et al., 2009; Karmazyn et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2013). Ginsenosides (including notoginsenoside R1) are dammarane triterpene saponins and are classified by structure into two types: 20(S)-protopanaxatriol-type (ppt-type) and 20(S)-protopanaxadiol-type (ppd-type). Despite their extensive clinical use, Sanqi therapies remain to be optimized. In this context, pharmacokinetic (PK) information of ginsenosides is crucial to the link between the individual ginsenosides' bioactivities and the Sanqi therapies. Although therapeutic advantages may exist in the Sanqi-based combination therapy, PK herb–herb interactions, including ginsenoside-based interactions, should be addressed. Because the use of medicinal herbal products is prevalent among patients who are taking synthetic drugs, PK studies that help to address the possible interactions between ginsenosides and synthetic drugs are also necessary.

Like Sanqi, herbs of other Panax species, such as P. quinquefolius roots (American ginseng) and P. ginseng roots (Asian ginseng), have their pharmacological properties, which are also ascribed to ginsenosides. Coronary artery disease is the most common cause of heart failure, which is a devastating condition with limited options for treatment (Tamargo and López-Sendón, 2011). Recently, Guo et al. (2011) and Moey et al. (2012) found that a ginsenoside extract from American ginseng could prevent and reverse cardiac hypertrophy, myocardial remodelling and heart failure in vitro and in vivo. However, these researchers were unable to determine which of the ginsenosides present accounted for the observed salutary effects. Dysfunctional blood vessel formation is a major problem in heart failure and therapeutic angiogenesis may be a suitable treatment option (Taimeh et al., 2013). Intriguingly, the ppt-type ginsenosides Rg1 and Re may be useful as non-peptide-based angiotherapeutic agents for tissue regeneration (Leung et al., 2006; 2007a; 2011,,). However, the coexisting ppd-type ginsenoside Rb1 has antiangiogenic properties and the ratio of the concentrations of the two types of ginsenosides can alter angiogenic properties (Sengupta et al., 2004; Leung et al., 2007b). Although there is a predominance of ppt-type ginsenosides in Sanqi (Li et al., 2005), it is unclear whether dosing a patient with the herbal extract via conventional oral and intravenous routes can enhance angiogenesis in the failing heart. To this end, a key step in moving forward is to determine the levels and durations of systemic exposure to ginsenosides and their intestinal absorption and heart disposition and to investigate the factors governing the pharmacokinetics that may affect their antihypertrophic, anti-remodelling, cardioprotective and angiogenic properties.

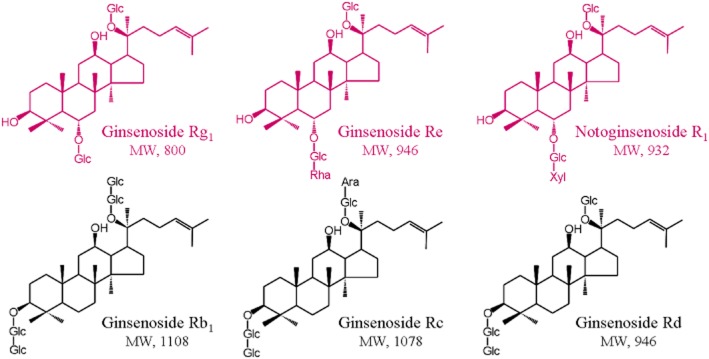

Recent PK studies of ginsenosides from aqueous Sanqi extracts in rat and human subjects indicated that both the ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 and ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1 and Rd were present in the blood stream after dosing (Liu et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2013). However, the two types of ginsenosides had markedly different elimination kinetics and hence significantly different levels and durations of systemic exposure despite their similar chemical structures (Figure 1). The ppt-type ginsenosides were primarily eliminated via rapid hepatobiliary excretion, but the ppd-type ginsenosides were slowly excreted into the bile (Liu et al., 2009). Transporter-mediated hepatobiliary excretion is a major determinant of plasma pharmacokinetics of many drugs and is therefore a likely target for possible PK drug–drug interactions. The current study was designed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the relevant elimination processes, which caused different pharmacokinetics of the ginsenosides. The data were analysed to derive further information about possible herb–drug and herb–herb interactions associated with the ginsenosides.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of ginsenosides. Ara, α-L-arabinopyranosyl; Glc, β-D-glucopyranosyl; Rha, α-L-rhamnopyranosyl and Xyl, β-D-xylopyranosyl.

Methods

A detailed description of experimental procedures and materials is provided in the Supporting Information Appendix S1, which is available online.

Cellular transport assays

HEK293 cells were grown in a DMEM fortified with 10% fetal calf serum in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. The human organic anion-transporting polypeptide (OATP)1B1, OATP1B3 and rat Oatp1b2 expression plasmids and the empty vector were introduced separately into the HEK293 cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Before use, the cells transfected with human OATP1B1, human OATP1B3 or rat Oatp1b2 plasmid were functionally characterized by measuring the protein expressing of transporters (Supporting Information Appendix S2) and uptake of oestradiol-17β-D-glucuronide (E217βG). Transport studies were carried out in 24-well poly-D-lysine-coated plates with the transfected cells 48 h after transfection. After pre-incubation, Krebs-Henseleit buffer was replaced by the same buffer fortified with the test compound or the prototypical substrate to initiate transport. The incubation was stopped at the designated time by aspirating the buffer from the well. After washing three times with ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit buffer, the cells were lysed and the resulting cellular lysates were analysed by LC-MS/MS. The transport rate of test compound in pmol·min−1 per mg protein was calculated using the following equation:

| Table 1 |

where CL represents the concentration of test compound in the cellular lysate (μM), VL is the volume of the lysate (μL), T is the incubation time (10 min) and WL is the measured cellular protein amount of each well (mg). Differential uptake between the transfected cells (TC) and the mock cells (MC) was defined as a net transport ratio (TransportTC/TransportMC ratio) and net transport ratio greater than three suggested a positive result. Kinetics of human OATP1B3- and rat Oatp1b2-mediated cellular uptakes of ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 were assessed with respect to Km and maximum velocity (Vmax) and the incubation time was set at 5 min to ensure that the assessment was performed under linear uptake conditions (Supporting Information Appendix S3). The inhibitory effect of rifampin on the activity of human OATP1B3 or rat Oatp1b2 that mediated transport of ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 was further measured in terms of inhibition constant (Ki). The inhibitory effects of ginsenosides on the activity of human OATP1B3- and OATP1B1-mediated transport of E217βG were measured in terms of half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and rifampin was used as positive control.

Vesicular transport assays

Inside-out membrane vesicles expressing human multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP)2, breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP), bile salt export pump (BSEP) or multidrug resistance protein (MDR)1 transporters or rat Mrp2, Bcrp or Bsep transporter were tested with the ginsenosides using a rapid filtration method according to a modified version of the manufacturer’s protocol. ATP was used as energy source to transport the test compounds across vesicle membrane and AMP was used for negative control. The quantity of compounds trapped inside the vesicles was measured by LC-MS/MS.

The transport rate of test compound in pmol·min−1 per mg protein was calculated using the following equation:

| Table 2 |

where CV represents the concentration of the compound in the vesicular lysate supernatant (μM), VV is the volume of the lysate (μL), T is the incubation time (10 min) and WV is the amount of vesicle protein amount per well (0.05 mg). Positive results for ATP-dependent transport were defined as a net transport ratio (TransportATP/TransportAMP ratio) greater than three. Kinetics of human MRP2-, BCRP-, BSEP- and MDR1- and rat Mrp2-, Bcrp- and Bsep-mediated vesicular transports of ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 were assessed with respect to Km and Vmax. The inhibitory effects of 100 μM ginsenosides on the activity of human MRP2, BCRP and BSEP that mediated transport of E217βG, methotrexate (MTX) and taurocholate acid (TCA), respectively, were also assessed.

Rat studies

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the Guidance for Ethical Treatment of Laboratory Animals (The Ministry of Science and Technology of China, 2006; www.most.gov.cn/fggw/zfwj/zfwj2006) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica (Shanghai, China). All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). A total of 243 animals were used in the experiments described here.

Male Sprague Dawley rats (230–300 g) were obtained from the Sino-British SIPPR/BK Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The femoral arteries of rats were cannulated for blood sampling and other rats underwent bile duct cannulation for bile collection (Chen et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2013). Three rat studies were performed with the rodents treated with or without rifampin (i.v., 20 mg·kg−1). For each rat study, rats were randomly assigned to nine groups to receive a bolus i.v. dose of ginsenosides Rg1, Re, Rb1 (using rifampin-free rats only), Rc (using rifampin-free rats only), Rd (using rifampin-free rats only) or notoginsenoside R1 at 2.5 μmol·kg−1. In the first rat study, serial blood samples (60 μL; 0, 5, 15, 30 min, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 24 h) were collected after dosing and heparinized. The plasma fractions were prepared by centrifugation. In the second rat study, bile samples were collected from rats between 0–2, 2–6, 6–12 and 12–24 h after dosing and were weighed. A sodium taurocholate solution (1.5 mL·h−1; pH 7.4) was infused into the duodenum during the day of bile collection. In the third rat study, urine samples were collected at 0–8 and 8–24 h after dosing and were weighed. The rats were housed singly in metabolic cages and the collection tubes containing their urine were frozen at −15°C during sample collection. All rat samples were stored at −70°C until analysis. Each rat study was repeated twice.

Determination of plasma protein binding

Equilibrium dialysis was used to assess the fraction of plasma protein-unbound compound (fu) (Guo et al., 2006). The test compounds were individually added into blank plasma to generate nominal concentrations of 5 μM for ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 and 50 μM for ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd. The fu value was calculated using the following equation:

| Table 3 |

where Cd represents the concentration in the dialysate (μM) after completion of dialysis and Cp is the corresponding concentration in the plasma (μM).

LC-MS/MS-based bioanalytical assays

Validated LC-MS/MS-based bioanalytical methods were used to measure test compounds [including the ginsenosides, rifampin, oestrone-3-sulfate (E1S), E217βG, TCA and MTX] in a variety of biomatrices. A TSQ Quantum mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) was interfaced via an electrospray ionization probe with a LC (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany).

Data processing

GraFit software (version 5.0; Erithacus Software, Surrey, UK) was used to determine the Km, Vmax, Ki and IC50 values. The calculation of Ki value was based on the following equation:

| Table 4 |

where v represents the difference in the transport of compound transported by transfected cells and the mock cells pmol·min−1 per mg protein, I and S are the concentration of inhibitor (μM) and substrate (μM) respectively. The IC50 for inhibition of transport activity obtained from a plot of percentage activity remaining (relative to control) versus log10 inhibitor concentration. Plasma PK parameters were estimated by non-compartmental analysis using Thermo Kinetica software package (version 5.0; InnaPhase, Philadelphia, PA, USA). The hepatobiliary excretory clearance (CLB) or the renal excretory clearance (CLR) was calculated by dividing the cumulative amount excreted into bile (Cum.Ae-B,0–t) or urine (Cum.Ae-U,0–t), respectively, by the plasma AUC0–t. The drug–drug interaction index (DDI index) was calculated using the following equation (Giacomini et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013):

| Table 5 |

where unbound Cmax represents the maximal plasma unbound concentration after therapeutic dosing (μM), IC50 represents the half maximal inhibitory concentration (μM) and R is the accumulative factor. R was calculated according to the following equation:

| Table 6 |

where k represents the elimination rate constant (0.693/t1/2) and τ is the dosing interval (h).

All data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Software (version 19.0; IBM, Somers, NY, USA). Data reported in the current study were assumed to describe a normal standard distribution and comparisons between two groups were performed by means of Student’s unpaired t-test. A value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be the minimum level of statistical significance.

Materials

Ginsenosides Rg1, Re, Rb1, Rc and Rd and notoginsenoside R1 were obtained from Tauto Biotech (Shanghai, China) and their purity exceeded 98%. Rifampin, E1S, E217βG, TCA, MTX, poly-D-lysine hydrobromide (70 000–150 000 Da) and ATP were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used for in vitro studies. Rifampin for injection (Huapont Pharmaceutical, Chongqing, China; with a China Food and Drug Administration ratification number of GuoYaoZhunZi-H20041320) that was used in the animal studies was freeze-dried solid and was available in a sterile parenteral dosage form for i.v. injection. HEK293 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Human OATP1B1 (NM_006446) and OATP1B3 (NM_019844) cDNA clones (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were subcloned into pcDNA3.1 expression plasmid by Invitrogen Life Technologies (Shanghai, China). The open reading frame of rat Oatp1b2 (NM_031650) was synthesized and subcloned into pcDNA3.1 expression plasmid by Invitrogen Life Technologies. Inside-out membrane vesicle suspensions that expressed human MRP2, MDR1, BCRP, BSEP or rat Mrp2, Bcrp or Bsep were obtained from Genomembrane (Kanazawa, Japan). Inside-out membrane vesicle suspensions that expressed rat Mdr1a or rat Mdr1b were obtained from BD Gentest (Woburn, MA, USA).

Results

In vitro interactions of ginsenosides with human hepatobiliary transporters

The ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 were found to be substrates of human OATP1B3, rather than those of human OATP1B1; the relevant net transport ratios are shown in Table 1. Ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd were not transported by OATP1B3 and OATP1B1 (Table 1). The OATP1B3-mediated uptakes of ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 were saturable with Km, Vmax and intrinsic clearance (CLint) values, as shown in Table 2 and were competitively inhibited by rifampin (Table 2 and Supporting Information Appendix S4). Although the OATP1B transporters did not transport ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd, these ppd-type ginsenosides inhibited the uptake of E217βG in a concentration-dependent manner with IC50 values of less than 1 μM for OATP1B3 and, for OATP1B1, of between 1 and 5 μM (Table 3). The ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 exhibited weak inhibitory properties towards the OATP1B transporters (IC50 values > 39 μM; Table 3).

Net transport ratios of in vitro transports of ginsenosides by various human and rat hepatic transporters

| Hepatic transporter | Positive control (10 μM) | Ppt-type | Ppd-type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginsenoside Rg1 (50 μM) | Ginsenoside Re (50 μM) | Notoginsenoside R1 (50 μM) | Ginsenoside Rb1 (50 μM) | Ginsenoside Rc (50 μM) | Ginsenoside Rd (50 μM) | ||

| Human hepatic SLC transporters | |||||||

| OATP1B1 | 97.7 ± 7.1 (E217βG) | 1.11 ± 0.02 | 1.20 ± 0.04 | 1.29 ± 0.06 | 1.04 ± 0.12 | 1.02 ± 0.14 | 0.914 ± 0.077 |

| OATP1B3 | 73.2 ± 10.9 (E217βG) | 15.1 ± 0.8 | 107 ± 15 | 37.2 ± 4.1 | 0.921 ± 0.135 | 0.892 ± 0.044 | 0.922 ± 0.006 |

| OATP2B1 | 88.6 ± 5.2 (E1S) | 0.918 ± 0.036 | 0.844 ± 0.021 | 1.02 ± 0.16 | 0.933 ± 0.266 | 1.14 ± 0.06 | 1.03 ± 0.19 |

| Human hepatic ABC transporters | |||||||

| MRP2 | 10.2 ± 0.9 (E217βG) | 10.9 ± 1.8 | 16.8 ± 2.3 | 23.9 ± 3.0 | 1.20 ± 0.20 | 0.921 ± 0.087 | 0.911 ± 0.075 |

| BCRP | 12.1 ± 1.4 (MTX) | 6.81 ± 0.8 | 4.12 ± 1.11 | 6.72 ± 0.22 | 1.51 ± 0.14 | 0.833 ± 0.074 | 1.04 ± 0.15 |

| BSEP | 4.22 ± 0.12 (TCA) | 3.12 ± 0.09 | 5.13 ± 0.45 | 5.31 ± 0.15 | 1.82 ± 0.08 | 0.842 ± 0.050 | 0.907 ± 0.078 |

| MDR1 | 4.67 ± 0.57 (VER) | 5.91 ± 0.17 | 5.99 ± 0.56 | 22.0 ± 1.3 | 1.49 ± 0.07 | 1.40 ± 0.23 | 1.24 ± 0.23 |

| Rat hepatic SLC transporters | |||||||

| Oatp1a1 | 7.61 ± 1.1 (E217βG) | 1.13 ± 0.00 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | 0.614 ± 0.005 | 1.11 ± 0.10 | 1.03 ± 0.01 | 0.916 ± 0.092 |

| Oatp1b2 | 63.0 ± 7.4 (E217βG) | 10.9 ± 1.44 | 9.92 ± 1.19 | 5.50 ± 0.23 | 0.912 ± 0.123 | 1.02 ± 0.03 | 1.17 ± 0.05 |

| Ntcp | 21.9 ± 3.9 (TCA) | 1.21 ± 0.37 | 0.927 ± 0.201 | 0.836 ± 0.023 | 0.813 ± 0.106 | 1.11 ± 0.12 | 1.03 ± 0.26 |

| Rat hepatic ABC transporters | |||||||

| Mrp2 | 13.1 ± 3.2 (E217βG) | 12.5 ± 0.12 | 10.2 ± 2.00 | 19.8 ± 4.1 | 1.21 ± 0.29 | 1.39 ± 0.06 | 1.11 ± 0.04 |

| Bcrp | 43.0 ± 7.6 (MTX) | 4.03 ± 0.32 | 4.01 ± 0.79 | 3.31 ± 0.24 | 1.03 ± 0.07 | 1.41 ± 0.08 | 1.21 ± 0.01 |

| Bsep | 10.5 ± 0.7 (TCA) | 5.91 ± 0.27 | 3.93 ± 0.14 | 4.32 ± 0.67 | 0.923 ± 0.105 | 1.22 ± 0.16 | 1.03 ± 0.00 |

| Mdr1a | 4.23 ± 0.06 (VER) | 1.52 ± 0.12 | 1.32 ± 0.07 | 1.52 ± 0.09 | 0.912 ± 0.012 | 1.20 ± 0.01 | 1.41 ± 0.09 |

| Mdr1b | 3.60 ± 0.04 (VER) | 1.22 ± 0.07 | 1.28 ± 0.04 | 1.28 ± 0.06 | 1.11 ± 0.13 | 0.922 ± 0.065 | 1.03 ± 0.04 |

E217βG, oestradiol-17β-D-glucuronide; E1S, oestrone-3-sulfate; MTX, methotrexate; TCA, taurocholic acid; VER, verapamil. The functions of human MDR1, rat Mdr1a and rat Mdr1b were verified with veripamil by ATPase assay according to the manufacturers' protocols and using the ratio of vesicular transport in the absence of sodium vanadate to that in the presence of sodium vanadate. Values represent the means ± SDs (n = 3). For those with net transport ratios greater than three, the differences between TransportTC and TransportMC or between TransportATP and TransportAMP were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of kinetic parameters for transports of ginsenosides by human and rat hepatic transporters

| Compound | Km | Vmax | CLint | Ki of rifampin (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μM) | (pmol·min−1 per mg protein) | (μL·min−1 per mg protein) | ||

| Human OATP1B3 | ||||

| Positive control (E217βG) | 12.5 ± 3.7 | 9.74 ± 0.72 | 0.779 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 45.4 ± 29.1 | 12.3 ± 6.2 | 0.270 | 0.725 ± 0.039 |

| Ginsenoside Re | 14.3 ± 4.2 | 21.5 ± 1.8 | 1.51 | 0.647 ± 0.043 |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 73.4 ± 33.6 | 12.3 ± 4.9 | 0.168 | 0.851 ± 0.062 |

| Human MRP2 | ||||

| Positive control (E217βG) | 18.2 ± 3.9 | 30.1 ± 3.0 | 1.65 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 93.5 ± 21.5 | 190 ± 21 | 2.03 | — |

| Ginsenoside Re | 89.3 ± 21.8 | 39.9 ± 4.5 | 0.447 | — |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 108 ± 22 | 119 ± 12 | 1.10 | — |

| Human BCRP | ||||

| Positive control (E1S) | 37.8 ± 15.4 | 130 ± 19 | 3.44 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 221 ± 110 | 38.1 ± 9.3 | 0.172 | — |

| Ginsenoside Re | 175 ± 69 | 33.9 ± 7.7 | 0.194 | — |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 208 ± 98 | 24.4 ± 6.9 | 0.117 | — |

| Human BSEP | ||||

| Positive control (TCA) | 8.09 ± 4.22 | 26.5 ± 4.5 | 3.28 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 113 ± 52 | 33.4 ± 7.3 | 0.296 | — |

| Ginsenoside Re | 106 ± 30 | 25.5 ± 3.1 | 0.241 | — |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 74.6 ± 34.9 | 23.1 ± 4.04 | 0.310 | — |

| Human MDR1 | ||||

| Positive control (VER) | 12.2 ± 1.0 | 45.3 ± 3.1 | 3.71 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 42.4 ± 7.9 | 113 ± 8 | 2.67 | — |

| Ginsenoside Re | 9.69 ± 7.05 | 4.09 ± 0.76 | 0.422 | — |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 38.4 ± 16.1 | 47.4 ± 6.4 | 1.23 | — |

| Rat Oatp1b2 | ||||

| Positive control (E217βG) | 20.7 ± 2.5 | 184 ± 7 | 8.89 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 72.6 ± 20.4 | 62.8 ± 7.6 | 0.864 | 0.681 ± 0.041 |

| Ginsenoside Re | 64.8 ± 24.0 | 131 ± 70 | 2.01 | 0.866 ± 0.047 |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 122 ± 37 | 41.7 ± 16.4 | 0.342 | 0.713 ± 0.031 |

| Rat Mrp2 | ||||

| Positive control (E217βG) | 22.2 ± 6.2 | 36.3 ± 4.1 | 1.64 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 19.7 ± 5.8 | 32.6 ± 2.5 | 1.65 | — |

| Ginsenoside Re | 68.6 ± 20.6 | 54.1 ± 7.4 | 0.789 | — |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 42.9 ± 11.2 | 36.9 ± 3.0 | 0.860 | — |

| Rat Bcrp | ||||

| Positive control (E1S) | 19.2 ± 9.1 | 166 ± 28 | 8.65 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 172 ± 68 | 41.8 ± 7.1 | 0.243 | — |

| Ginsenoside Re | 101 ± 73 | 20.7 ± 6.2 | 0.205 | — |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 248 ± 83 | 78.5 ± 17.4 | 0.317 | — |

| Rat Bsep | ||||

| Positive control (TCA) | 23.1 ± 11.9 | 134 ± 26 | 5.80 | — |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 126 ± 43 | 94.3 ± 13.6 | 0.748 | — |

| Ginsenoside Re | 181 ± 33 | 61.1 ± 12.9 | 0.338 | — |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 149 ± 76 | 34.2 ± 11.1 | 0.230 | — |

The positive control compounds used were E217βG, oestradiol-17β-D-glucuronide; E1S, oestrone-3-sulfate; TCA, taurocholic acid; VER, verapamil. The function of human MDR1 was verified with verapamil by ATPase assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol and using the ratio of vesicular transport in the absence of sodium vanadate to that in the presence of sodium vanadate. The Vmax for stimulation of human MDR1 ATPase activity by verapamil is in pmol Pi·min−1 per mg protein. Values represent the means ± SDs (n = 3, except for the values for human OATP1B3- and rat Oatp1b2-mediated transports of the ppt-type ginsenosides for which n = 9).

Table 3.

Comparative IC50 values for ginsenosides on human OATP1B3 and OATP1B1 activities (mediating transport of E217βG) and associated DDI indices

| Compound | IC50 | Unbound Cmax | t1/2 | R | DDI index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μM) | (μM) | (h) | |||

| OATP1B3 | |||||

| Rifampin | 1.63 ± 0.25 | 1.84–3.45 | 1.00–4.40 | 1.00–1.02 | 1.13–2.16 |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 43.1 ± 3.0 | 0.789–5.00 | 1.27–2.01 | 1.00 | 0.0183–0.116 |

| Ginsenoside Re | 39.4 ± 3.5 | 0.210–0.226 | 0.59–0.88 | 1.00 | 0.00533–0.00574 |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 332 ± 29 | 0.812 | 1.41 | 1.00 | 0.00245 |

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | 0.467 ± 0.051 | 0.085–0.242 | 40.1–48.0 | 2.95–3.41 | 0.540–1.77 |

| Ginsenoside Rc | 0.208 ± 0.030 | — | — | — | — |

| Ginsenoside Rd | 0.235 ± 0.022 | 0.005 | 36.6 | 2.74 | 0.0583 |

| OATP1B1 | |||||

| Rifampin | 3.79 ± 0.28 | 1.84–3.45 | 1.00–4.40 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.485–0.928 |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 70.4 ± 9.9 | 0.789–5.00 | 1.27–2.01 | 1.00 | 0.0112–0.0710 |

| Ginsenoside Re | 133 ± 15 | 0.210–0.226 | 0.59–0.88 | 1.00 | 0.00158–0.00170 |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 359 ± 101 | 0.812 | 1.41 | 1.00 | 0.00226 |

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | 4.60 ± 0.75 | 0.085–0.242 | 40.1–48.0 | 2.95–3.41 | 0.0545–0.179 |

| Ginsenoside Rc | 2.72 ± 0.26 | — | — | — | — |

| Ginsenoside Rd | 1.42 ± 0.12 | 0.005 | 36.6 | 2.74 | 0.00965 |

The clinical Cmax and t1/2 values of rifampin at the therapeutic dose of 600 mg per day (p.o. administration) were from reported human data (Acocella, 1978; Loos et al., 1985). The clinical Cmax and t1/2 values of ginsenosides were from our PK data of human subjects receiving XueShuanTong (a ginsenoside injection prepared from Sanqi; details pending publication elsewhere) and from the reported human PK data for ShenMai injection and ShengMai injection by Li et al. (2011). The drug–drug interaction index (DDI index = unbound Cmax·R/IC50) were calculated for the transporter-ginsenoside couples. R is the accumulative factor that is calculated using the equation R = 1/(1 − e−kτ), where k is the elimination rate constant (0.693/t1/2) and τ is the dosing interval (24 h). A DDI index value greater than 0.1 indicates the potential for DDIs and the need for an in vivo DDI study. Values represent the means ± SDs (n = 6, except for the values for rifampin for which n = 3).

In addition to the preceding solute carrier (SLC) transporters, human hepatic efflux transporters also exhibited in vitro transport activities for the ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 with net transport ratios for MRP2, BCRP, BSEP and MDR1 shown in Table 1. However, these ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters exhibited little or no activity towards the transports of the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd (Table 1). The Km Vmax and CLint values for the MRP2-, BCRP-, BSEP- and MDR1-mediated transports of the ppt-type ginsenosides are shown in Table 2. The ppd-type ginsenosides did not exhibit any significant inhibitory activity towards these ABC transporters. This was indicated by 100 μM ginsenosides producing only 7.3–21.3% inhibition of transport activities of MRP2 (E217βG), BCRP (MTX) and BSEP (TCA).

In vitro transports of ginsenosides by rat hepatobiliary transporters

The rat hepatic uptake transporter Oatp1b2 (Slco1b2) is the closest orthologue of human OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 (Cattori et al., 2000; Kullak-Ublick et al., 2001). Rat Oatp1b2 also preferentially transported the ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1, but it did not have any significant transport activity for the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd (Table 1). The Km values of the ppt-type ginsenosides for rat Oatp1b2 were slightly greater than those for human OATP1B3 (Table 2). The Oatp1b2-mediated uptake of the ppt-type ginsenosides was also inhibited competitively by rifampin (Table 2 and Supporting Information Appendix S4). The rat ABC transporters Mrp2, Bcrp and Bsep exhibited transport activities for the ppt-type ginsenosides (Table 1), with Km Vmax and CLint values shown in Table 2. These ABC transporters did not exhibit any significant activity towards the transports of the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd (Table 1).

Rifampin-induced disruption of Oatp1b2 altered the levels of rat systemic exposure to ppt-type ginsenosides but their elimination kinetics were still significantly different from those of ppd-type ginsenosides

Rifampin is an OATP/Oatp inhibitor and substrate (Vavricka et al., 2002; Zaher et al., 2008). As shown in Supporting Information Appendix S4, the plasma level of rifampin declined with a mean t1/2 of 3.3 h in rats after an i.v. dose of 20 mg·kg−1. Rifampin was moderately bound to rat plasma protein (fu, 23.1%). Accordingly, the unbound plasma concentrations of rifampin (1.1–9.8 μM) during 0–8 h after dosing exceeded its Ki values for inhibition of rat Oatp1b2-mediated transports of the ppt-type ginsenosides (0.7–0.9 μM).

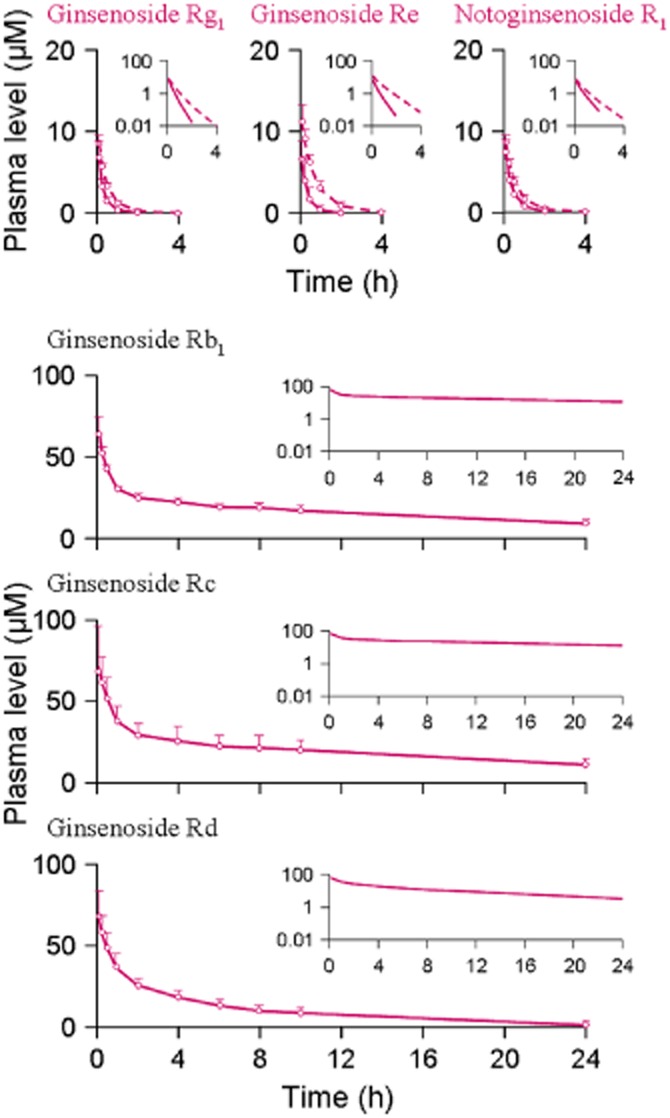

There were significant differences between the ppt-type ginsenosides (ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1) and the ppd-type ginsenosides (ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd) in the systemic exposure and elimination kinetics after i.v. dosing with the individual compounds at 2.5 μmol·kg−1 (Figures 2 and 3 and Table 4). This was shown by the plasma AUC0–∞ and t1/2 values of the latter, which were 105–368 times and 26–88 times, respectively, greater than those of the former. The total plasma clearance (CLtot,p) values of the ppd-type ginsenosides were only 0.3–1.1% of those of the ppt-type ginsenosides. To determine the role of the rapid hepatobiliary excretion of the ppt-type ginsenosides in the preceding differences relative to their ppd-type counterparts, rats were treated with rifampin. The rifampin treatment led to slowed biliary excretion of the ppt-type ginsenosides (Figure 3 and Table 4). This was indicated by the CLB values of the ppt-type ginsenosides in the rifampin-treated rats, which were only 3.1–10.6% of those in the control rats. The plasma AUC0–∞ of the ppt-type ginsenosides in the rifampin-treated rats were 1.6–2.9-fold higher than those in control rats and the t1/2 values were 1.7–2.3-fold greater (P < 0.01 for all). The increased levels of systemic exposure (in plasma AUC0–∞) to these ppt-type ginsenosides induced with rifampin were associated with increased levels of tissue exposure (1.7–2.5-fold greater for the heart, 1.4–2.6-fold greater for the lung, 1.2–1.7-fold greater for the brain and 1.6–2.6-fold greater for the kidneys relative to the respective control organ tissues; P < 0.05 for all), except for the liver levels (only 37.5–39.9% of those in the control rats; P, 0.0005–0.02) (Supporting Information Appendix S5). However, even after the rifampin-induced increases, the levels of systemic exposure to ppt-type ginsenosides, as assessed by plasma AUC0–∞, were still significantly lower than those of ppd-type ginsenosides (Figures 2 and 3 and Table 4). The rifampin treatment did not considerably change the elimination kinetics of the ppt-type ginsenosides. This was indicated by their increased t1/2 values (0.5–0.6 h), which were still significantly shorter than those of the ppd-type ginsenosides (8.3–20.6 h).

Figure 2.

Plasma concentrations of the ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 and the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd over time after a bolus i.v. dose of individual compound at 2.5 μmol·kg−1 in normal rats (solid lines for both types of ginsenosides) and rifampin-treated rats (dashed lines for the ppt-type ginsenosides only). The data represent means and SDs from three independent experiments where each rat group was assayed in triplicate.

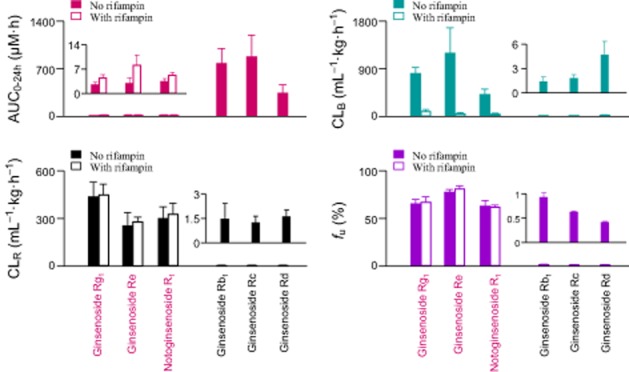

Figure 3.

Different levels of systemic exposure (AUC), hepatobiliary excretory clearance (CLB), renal excretory clearance (CLR) and plasma protein-unbound fraction (fU) of the ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 and the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd after a bolus i.v. dose of individual compound at 2.5 μmol·kg−1 in normal rats (No rifampin) and rifampin-treated rats. The data represent means and SDs from three independent experiments where each rat group was assayed in triplicate.

Table 4.

PK parameters of ginsenosides after i.v. administration at 2.5 μmol·kg−1 in rats treated with and without rifampin (20 mg·kg−1)

| PK parameter | Ppt-type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | Ginsenoside Re | Notoginsenoside R1 | ||||

| (−) Rifampin | (+) Rifampin | (−) Rifampin | (+) Rifampin | (−) Rifampin | (+) Rifampin | |

| Plasma data | ||||||

| C5min (μM) | 6.80 ± 1.98 | 8.56 ± 1.12* | 6.63 ± 2.40 | 11.3 ± 2.34*** | 7.07 ± 1.30 | 8.23 ± 0.79* |

| AUC0–∞ (h·μM) | 2.38 ± 0.66 | 4.30 ± 0.91*** | 2.77 ± 1.63 | 8.11 ± 2.88*** | 3.19 ± 0.63 | 5.19 ± 0.73*** |

| t1/2 (h) | 0.235 ± 0.017 | 0.450 ± 0.047*** | 0.236 ± 0.071 | 0.537 ± 0.083*** | 0.316 ± 0.049 | 0.552 ± 0.063*** |

| VSS (mL·kg−1) | 332 ± 108 | 316 ± 87 | 287 ± 82 | 216 ± 50 | 308 ± 29 | 286 ± 27 |

| CLtot,p (mL·h−1·kg−1) | 1148 ± 399 | 624 ± 163** | 1238 ± 684 | 320 ± 88** | 786 ± 172 | 471 ± 89*** |

| Bile data | ||||||

| Cum.Ae-B,0–24h (nmol·kg−1) | 1680 ± 261 | 325 ± 130*** | 2319 ± 277 | 248 ± 65*** | 1281 ± 211 | 139 ± 71*** |

| fe-B (%) | 67.9 ± 9.7 | 12.7 ± 5.0*** | 94.6 ± 11.7 | 10.5 ± 3.3*** | 52.3 ± 8.7 | 5.69 ± 2.80*** |

| CLB (mL·h−1·kg−1) | 810 ± 117 | 85.7 ± 42.6*** | 1208 ± 587 | 37.6 ± 18.1*** | 403 ± 70 | 25.2 ± 13.1*** |

| Urine data | ||||||

| Cum.Ae-U,0–24h (nmol·kg−1) | 932 ± 301 | 1808 ± 497*** | 535 ± 236 | 1928 ± 316*** | 954 ± 225 | 1775 ± 369*** |

| fe-U (%) | 36.9 ± 12.7 | 75.6 ± 16.0*** | 21.8 ± 9.2 | 81.1 ± 17.5*** | 41.9 ± 12.1 | 75.8 ± 22.4** |

| CLR (mL·h−1·kg−1) | 434 ± 93 | 447 ± 71 | 251 ± 87 | 277 ± 63 | 300 ± 72 | 322 ± 72 |

| PK parameter | Ppd-type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | Ginsenoside Rc | Ginsenoside Rd | ||||

| (−) Rifampin | (−) Rifampin | (−) Rifampin | ||||

| Plasma data | ||||||

| C5min (μM) | 61.5 ± 9.4 | 69.1 ± 25.9 | 66.9 ± 16.3 | |||

| AUC0–∞ (h·μM) | 773 ± 210 | 875 ± 311 | 336 ± 116 | |||

| t1/2 (h) | 19.2 ± 2.4 | 20.6 ± 4.7 | 8.31 ± 2.64 | |||

| VSS (mL·kg−1) | 92.7 ± 20.4 | 97.7 ± 56.0 | 80.4 ± 20.2 | |||

| CLtot,p (mL·h−1·kg−1) | 3.54 ± 1.17 | 3.28 ± 1.31 | 8.34 ± 3.11 | |||

| Bile data | ||||||

| Cum.Ae-B,0–24h (nmol·kg−1) | 540 ± 241 | 738 ± 195 | 1165 ± 248 | |||

| fe-B (%) | 21.6 ± 9.6 | 29.1 ± 8.3 | 45.0 ± 9.4 | |||

| CLB (mL·h−1·kg−1) | 1.29 ± 0.54 | 1.71 ± 0.39 | 4.54 ± 1.68 | |||

| Urine data | ||||||

| Cum.Ae-U,0–24h (nmol·kg−1) | 554 ± 255 | 509 ± 106 | 422 ± 101 | |||

| fe-U (%) | 21.3 ± 9.0 | 20.0 ± 4.7 | 16.2 ± 4.4 | |||

| CLR (mL·h−1·kg−1) | 1.45 ± 1.00 | 1.22 ± 0.42 | 1.59 ± 0.42 | |||

(+) Rifampin, rat group treated with rifampin. (-) Rifampin, rat group not treated with rifampin. C5min, concentration at 5 min after dosing; AUC0–∞, area under concentration-time curve from zero to infinity; t1/2, elimination half-life; VSS, distribution volume at steady state; CLtot,p, total plasma clearance; fe-B, fractional biliary excretion; Cum.Ae-B,0–24h, cumulative amount excreted into bile; CLB, hepatobiliary excretory clearance; fe-U, fractional urinary excretion; Cum.Ae-U,0–24h, cumulative amount excreted into urine; CLR, renal excretory clearance. The data represent means ± SDs from three independent experiments where each rat group was performed in triplicate (total n = 9). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; significantly different from the values in rats not treated with rifampin).

Plasma protein binding and renal excretion of ginsenosides

Dramatic differences in CLR were also observed between the ppt-type ginsenosides (ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1) and the ppd-type ginsenosides (ginsenosides Rb1, Rc, and Rd) in rats (Figure 3 and Table 4). This was most clearly indicated by the CLR values, which were more than 150-fold greater for the former group than for the latter. Despite these differences, the renal excretion of all these ginsenosides appeared to primarily involve passive glomerular filtration, rather than active tubular secretion. This was indicated by the CLR values of all the ginsenosides, none of which exceeded the products of the reported average glomerular filtration rate of Sprague Dawley rats (624 mL·h−1·kg−1; Yu et al., 2007) and the measured plasma fu values (Table 5). The rifampin treatment did not significantly affect the CLR values of the ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 (Figure 3 and Table 4). This was because rifampin did not affect the glomerular-filtration-based renal excretion, for example by changing the plasma protein binding of the ppt-type ginsenosides (Figure 3). However, the fractions of administered ginsenosides that were excreted into urine in the rifampin-treated rats (fe-U, 75.6%, 81.1% and 75.8% for ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1, respectively) were significantly higher than the fe-U values for the control rats (36.9%, 21.8% and 41.9%, respectively) (P < 0.01 for all).

Table 5.

Fractions of plasma protein-unbound ginsenosides

| Compound | fu (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Human plasma | Rat plasma | ||

| Male | Female | Male | |

| Ppt-type ginsenoside | |||

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | 78.1 ± 2.6 | 71.5 ± 5.8 | 64.8 ± 4.2 |

| Ginsenoside Re | 77.9 ± 5.9 | 66.8 ± 9.2 | 77.1 ± 2.7 |

| Notoginsenoside R1 | 69.4 ± 2.3 | 77.1 ± 5.0 | 62.3 ± 5.7 |

| Ppd-type ginsenoside | |||

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | 0.891 ± 0.110 | 0.921 ± 0.019 | 0.912 ± 0.089 |

| Ginsenoside Rc | 0.612 ± 0.012 | 0.597 ± 0.012 | 0.611 ± 0.011 |

| Ginsenoside Rd | 0.392 ± 0.022 | 0.390 ± 0.032 | 0.402 ± 0.024 |

The fu values were measured with drug-free human plasma and rat plasma fortified with the ppt-type ginsenosides at 5 μM and the ppd-type ginsenosides at 50 μM individually. The blank human plasma was obtained from a human study with freeze-dried XueShuanTong for injection (ChiCTR-ONRC-13003905; http://www.guidetopharmacology.org). Values represent the means ± SDs (n = 3).

Discussion and conclusions

Both ppd-type and ppt-type ginsenosides present in Sanqi exhibit cardiovascular properties. However, PK studies in rats and humans indicated that the two types of ginsenosides had markedly different elimination kinetics and hence significantly different levels and durations of systemic exposure after dosing with a Sanqi extract (Liu et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2013). These PK differences of ginsenosides are expected to affect the outcomes of Sanqi therapies. Studying the elimination of ginsenosides at the molecular level facilitates better understanding of these PK differences. The difference in elimination kinetics, observed in rats, involves a significant discrepancy in CLB between the two types of ginsenosides. Such a CLB discrepancy most probably also occurs in humans. Hepatobiliary excretion of various endogenous and xenobiotic compounds is often accomplished in two steps: (i) SLC transporter-mediated cellular uptake from blood through the sinusoidal membrane to the hepatocytes and (ii) ABC transporter-mediated efflux from the hepatocytes into bile across the canalicular membrane (Pfeifer et al., 2014).

In the current study, the ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 were found to be substrates of the human hepatobiliary SLC transporter OATP1B3 (SLCO1B3) and the human hepatobiliary ABC transporters MRP2 (ABCC2), BCRP (ABCG2), BSEP (ABCB11) and MDR1 (ABCB1). Although the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd were also bound to OATP1B3, they were not transported. These ppd-type ginsenosides were also not transported by the preceding ABC transporters. Based on this and on their poor membrane permeability (Liu et al., 2009), it was concluded that the circulating ppd-type ginsenosides in the bloodstream were very slowly transported into bile via human hepatocytes. This suggested that there was a significant CLB discrepancy between the two types of ginsenosides in humans. Similarly, although all the ginsenosides were bound to the rat SLC transporter Oatp1b2 (Slco1b2), only the ppt-type ginsenosides were transported. The ppt-type ginsenosides were also substrates of the rat ABC transporters Mrp2 (Abcc2), Bcrp (Abcg2) and Bsep (Abcb11). Despite their poor membrane permeability, multiple ABC transporters working in concert resulted in short half-lives of the ppt-type ginsenosides in the livers of rats (t1/2, 0.2–0.4 h; Supporting Information Appendix S5) and prevented their accumulation in the organs. In contrast, the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd were not the substrates of the rat ABC transporters. The liver t1/2 values of these ppd-type ginsenosides were long (10.8–16.4 h; Supporting Information Appendix S5). A similar scenario is expected in humans, including the interactions of the human ABC transporters with the ginsenosides and the differences in liver disposition between the two types of the ginsenosides. Therefore, rats were used to delineate and extrapolate the in vivo relevance of the human hepatobiliary transporters to the levels of systemic exposure to the ginsenosides.

Neither the ppt-type ginsenosides nor the ppd-types ginsenosides are significantly eliminated via metabolism by rat enterohepatic enzymes (Liu et al., 2009). The markedly different elimination kinetics between the two types of ginsenosides in rats mainly resulted from the differences in both transporter-mediated CLB and glomerular-filtration-based CLR. For the ppt-type ginsenosides, the two excretion pathways worked in concert but competed with each other; their roles in the elimination of the compounds depended on the sizes of the CLB (810, 1208 and 403 mL·h−1·kg−1 for ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1, respectively) and CLR (434, 251 and 300 mL·h−1·kg−1 respectively) (Table 4). The rifampin-induced disruption of rat hepatobiliary excretion resulted in 1.8-, 2.9- and 1.6-fold increases in plasma AUC0–∞ levels of ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 respectively. However, the elevated exposure levels were still significantly lower than the exposure levels of the ppd-type ginsenosides (Figures 2 and 3 and Table 4). Although rifampin could impair the hepatobiliary excretion with respect to CLB, it did not change the CLR of the ppt-type ginsenosides. This is because rifampin did not change the plasma protein binding of these ginsenosides and in turn the associated glomerular filtration. The impairment of hepatobiliary excretion reduced the total clearance (CLtot,p). This, in turn, increased plasma concentrations of the ppt-type ginsenosides and their concentration-dependent rates of renal excretion. The effect of rifampin could also be viewed from another angle. The impairment of hepatobiliary excretion considerably reduced competition with the alternate pathway renal excretion for eliminating the ppt-type ginsenosides. Under the given i.v. dose of the ppt-type ginsenoside 2.5 μmol·kg−1, this led to the renal excretion having longer time to eliminate these ginsenosides than it did when the hepatobiliary excretion worked normally. This is indicated by the rifampin-affected t1/2 (0.5, 0.5 and 0.6 h, for ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1, respectively), which were longer than those in the rats not treated with rifampin (0.2, 0.2 and 0.3 h, respectively; P < 0.001). Taken together, both the increased rate of renal excretion (due to the increased plasma concentrations) and the prolonged time for renal excretion (due to the decreased competition from the hepatobiliary excretion) resulted in the increased urinary Cum.Ae-U,0–t and fe-U of the ppt-type ginsenosides in the rats treated with rifampin (Table 4). Because of the compensation by renal excretion, the drug-induced impairment of hepatobiliary excretion did not alter considerably the differential elimination kinetics between the two types of ginsenosides in rats. Similar mechanisms governing differential Pharmacokinetics of ginsenosides is expected in humans. In rats, the difference in CLB mainly resulted from the ppt-type ginsenosides that were transported by Oatp1b2. The ppd-type ginsenosides were not transported. In humans, the difference in CLB mainly resulted from the ppt-type ginsenosides that were transported by OATP1B3. The ppd-type ginsenosides were not transported. In rats, the difference in CLR resulted from the ppd-type ginsenosides extensively bound to plasma protein (fu values, 0.4–0.9%). The fu values of the ppt-type ginsenosides were 62.3–77.1%. In humans, the difference in CLR resulted from the ppd-type ginsenosides extensively bound to plasma protein (0.4–0.9%). The fu values of the ppt-type ginsenosides were 66.8–78.1%. Like rats, metabolic elimination of unchanged ginsenosides is negligible in humans (Hu et al., 2013).

The use of medicinal herbal products is prevalent among patients who are taking synthetic drugs. All substances from the administered drugs and herbs can interact with each other (Fugh-Berman, 2000; Tachjian et al., 2010; Shi and Klotz, 2012). In the practice of Chinese traditional medicine, herb combination therapy (‘fangji peiwu’ in Chinese) is often used to therapeutic advantage either because the beneficial effects are synergistic or additive or because therapeutic effects can be achieved with fewer herb-specific side effects by using submaximal doses of herbs in concert. However, herb combination therapy can give rise to PK herb–herb interactions. PK herb–drug and herb–herb interactions are relevant because they can be a source of variability in drug and herb responses. This may complicate the dosing of long-term medications. Because of their function and broad substrate specificity, OATP1B transporters are very likely to be targets for drug interactions in the liver (Kallioloski and Niemi, 2009; König et al., 2013).

In the current study, the propensity of the ginsenosides to cause OATP1B-related herb–drug and herb–herb interactions was determined. Notably, the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd showed rather high affinity for OATP1B3 (IC50 values, 0.2–0.5 μM for inhibition of E217βG transport) and high affinity for OATP1B1 (1.4–4.6 μM for inhibition of E217βG transport). The affinity of the ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 for OATP1B transporters was lower than that of the ppd-type ginsenosides. Their IC50 values for OATP1B3 and OATP1B1 (both for inhibition of E217βG transport) were 39.4–332.0 and 70.4–358.6 μM respectively. To assess the clinical relevance of these findings, the knowledge on plasma concentrations of ginsenosides in humans are essential, particularly the unbound plasma concentrations. The ppd-type ginsenosides had extremely high plasma protein binding (fu values, 0.4–0.9%). The fu values of the ppt-type ginsenosides were 66.8–78.1%. Ginsenosides had poor intestinal absorption, their unbound plasma concentrations after p.o. dosing with Sanqi extract and ginseng preparations in humans were in the low nanomolar range (Ji et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2013), which was much lower than the IC50 values. Oral ginsenosides had little propensity to act as inhibitory agents in OATP1B-based interactions. In China, an herbal injection prepared from Sanqi (freeze-dried XueShuanTong for injection) and those containing red Asian ginseng (including ShenMai injection, ShengMai injection and ShenFu injection) are extensively used, which are sterile, non-pyrogenic parenteral dosage forms for i.v. injection. Unlike the situation with the oral dosage forms, the plasma concentrations of the ginsenosides are quite high after i.v. administration of these herbal injections in human. Based on our own human data and clinical reports by others, the range of Cmax of ginsenoside Rb1 was 26.3 ± 2.6 μM after i.v. administration of a therapeutic dose of XueShuanTong (details pending publication elsewhere), 14.9 ± 10.6 μM after i.v. administration of a therapeutic dose of ShenMai injection and 9.5 ± 8.1 μM after i.v. administration of a therapeutic dose of ShengMai injection (Li et al., 2011). Although ginsenoside Rb1 was extensively bound to human plasma protein, the unbound Cmax ranged from 0.1 to 0.2 μM after a single i.v. dose of the herbal injections. In addition, a long t1/2 of 40.1–48.0 h in humans indicated that multiple doses of the herbal injections would lead to accumulation of this ppd-type ginsenoside in plasma and the unbound Cmax could increase to 0.3–0.8 μM. Accordingly, the ginsenoside Rb1-based DDI indices were calculated as 0.54–1.77 for OATP1B3 and 0.05–0.18 for OATP1B1 (Table 3). ShenMai injection and ShengMai injection also contained comparable amounts of ginsenosides Rc and Rd to ginsenoside Rb1 (Supporting Information Appendix S6). It is worth mentioning that all these ppd-type ginsenosides from the herbal injections probably have additive inhibitory effect on OATP1B transporters. Ginsenoside Rg1 represented the most abundant ppt-type ginsenosides in freeze-dried XueShuanTong for injection. The ginsenoside Rg1-based DDI indices were 0.02–0.12 for OATP1B3 and 0.01–0.07 for OATP1B1 (Table 3). Clinically important drugs, including telmisartan and paclitaxel, have been identified as substrates of OATP1B3 (Smith et al., 2005; Ishiguro et al., 2006). The clinically relevant herb–drug interactions may be caused by inhibition of OATP1B3-mediated uptake of these drugs in the liver by the ppd-type ginsenosides from the herbal injections.

The ppt-type ginsenoside Rg1, ginsenoside Re and notoginsenoside R1 were found to be weak in vitro inhibitors of the hepatic efflux transporters MRP2, BCRP and BSEP with the IC50 values > 100 μM. Therefore, the ppt-type ginsenosides tended not to alter the liver concentrations of other drugs and herbal compounds. Multiple ABC transporters appeared to mediate the efflux of the ppt-type ginsenosides from the hepatocytes into bile. Although the individual contributions of these transporters to the overall hepatobiliary efflux has not been characterized, alteration of the efflux of the ppt-type ginsenosides via drug interaction might involve affecting the concerted action of multiple transporters, rather than affecting function of a single transporter. The ppd-type ginsenosides did not interact with the ABC transporters either as substrates or as inhibitors.

Saponins are the bioactive constituents of many medicinal herbs (Francis et al., 2002; Sparg et al., 2004). They are amphiphilic glycosides containing one or more sugar chains linked to a non-polar triterpene or steroid aglycone skeleton. Rapid and extensive hepatobiliary excretion represents an important route of elimination for many saponins and can affect their oral bioavailability and Pharmacokinetics (Yu et al., 2012). Several saponins have been found to interact with the human OATP1B transporters. Ismair et al. (2003) reported that glycyrrhizin inhibited OATP1B1-mediated uptake of [3H]E1S into Xenopus laevis oocytes (Ki, 15.9 μM) and OATP1B3-mediated uptake of [35S]bromosulfophthalein (12.5 μM). Recently, Wu et al. (2012) assessed the effects of multiple herbal compounds, including several saponins, on the function of OATP1B1. Here, the ppd-type ginsenosides Rb1, Rc and Rd were found to have high inhibitory activities towards OATP1B3. Besides triterpene saponins, the steroid saponin dioscin was also found to be a substrate of OATP1B3 (Km, 2 μM) rather than that of OATP1B1 (Zhang et al., 2013). So far, a limited number of saponin compounds have been investigated with respect to their interactions with OATP1B transporters. Multiple hepatobiliary ABC transporters were found to have transport activities for the ppt-type ginsenosides. However, there are gaps regarding the manner in which the ABC transporters interact with other medicinal saponins. It is necessary to examine more medicinal saponins.

The most important findings from the current study include the following. (i) Both the types of ginsenosides were bound to human OATP1B3/rat Oatp1b2 transporters, but only the ppt-type ginsenosides were transported. This explained their markedly different CLB values. (ii) Multiple ABC transporters mediated the efflux of the ppt-type ginsenosides from the hepatocytes into bile. This led to their short half-lives in the rat livers and a similar scenario is expected in humans. (iii) Unlike the ppt-type ginsenosides, the ppd-type counterparts were extensively bound to plasma protein. This caused their significant differences in glomerular-filtration-based CLR. (iv) The hepatobiliary excretion and renal excretion of the ppt-type ginsenosides worked in concert and competed with each other in normal rats. (v) The ppd-type ginsenosides had high inhibitory potency towards OATP1B3. Caution should be exercised with these long circulating saponins which could induce herb-drug interactions, especially when patients receive long-term therapies with high-dose i.v. Sanqi or ginseng extracts. The results reported here have implications for translation of many promising findings regarding ginsenosides from the laboratory to the clinical settings and for safety assessment of Sanqi and ginseng therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Fund of China for Distinguished Young Scholars (30925044), the National Science & Technology Major Project of China ‘Key New Drug Creation and Manufacturing Program’ (2009ZX09304-002) and the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB518403). This work was presented in part as a poster presentation at the CPSA, Shanghai, China, April 25–28, 2012: Jiang R-R et al. Hepatic SLC and ABC transporters mediating biliary excretion of ginsenoside Rg1 and their impact on rat systemic exposure to the saponin. We are grateful for Dr Satoshi Senda (Genomembrane Co., Ltd., Kanazawa, Japan) for kindly providing the mRNA level data of transporter-expressing vesicles (Supporting Information Appendix S2). We are also grateful for Dr Min Tan for technical assistance on western blotting analysis.

Glossary

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- BCRP/Bcrp

breast cancer resistance protein

- BSEP/Bsep

bile salt export pump

- CLB

hepatobiliary excretory clearance

- CLint

intrinsic clearance

- CLR

renal excretory clearance

- CLtot,p

total plasma clearance

- Cum.Ae-B

cumulative amount excreted into bile

- Cum.Ae-U

cumulative amount excreted into urine

- DDI

drug–drug interaction

- E1S

oestrone-3-sulfate

- E217βG

oestradiol-17β-D-glucuronide

- fe-B

fractional biliary excretion

- fe-U

fractional urinary excretion

- fu

fraction of plasma protein-unbound compound

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- Km

Michaelis constant

- Ki

inhibition constant

- MDR/Mdr

multidrug resistance protein

- MRP/Mrp

multidrug resistance-associated protein

- OATP/Oatp

organic anion-transporting polypeptide

- SLC

solute carrier

- t1/2

elimination half-life

- Vmax

maximum transport velocity

Author contributions

C. L. and R. J. participated in research design, performed the data analysis and wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript. R. J., J. D., X. L., F. D., W. J., F. X., F. W., J. Y. and W. N. conducted the experiments.

Conflict of interest

There are no competing interests to declare.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Appendix S1 Supplemental methods.

Appendix S2 Protein expression of OATP1B1, OATP1B3 and Oatp1b2 in transfected HEK293 cells and mRNA levels of MRP2, BCRP, BSEP, MDR1, Mrp2, Bcrp and Bsep in membrane vesicles.

Appendix S3 Time courses for accumulation of the ppt-type ginsenosides in HEK293 cells expressing human OATP1B3 or rat Oatp1b2.

Appendix S4 Rifampin inhibition of human OATP1B3- and rat Oatp1b2-mediated uptake of the ppt-type ginsenosides, plasma pharmacokinetics of rifampin in rats and rifampin-mediated drug–drug interactions.

Appendix S5 Rat tissue distribution of ginsenosides.

Appendix S6 Content levels of ginsenosides in herbal injections.

References

- Acocella G. Clinical pharmacokinetics of rifampicin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1978;3:108–127. doi: 10.2165/00003088-197803020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Transporters. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1706–1796. doi: 10.1111/bph.12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattori V, Hagenbuch B, Hagenbuch N, Stieger B, Ha R, Winterhalter KE, et al. Identification of organic anion transporting polypeptide 4 (Oatp4) as a major full-length isoform of the liver-specific transporter-1 (rlst-1) in rat liver. FEBS Lett. 2000;474:242–245. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01596-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Li L, Xu F, Sun Y, Du F-F, Ma X-T, et al. Systemic and cerebral exposure to and pharmacokinetics of flavonols and terpene lactones after dosing standardized Ginkgo biloba leaf extracts to rats via different routes of administration. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:440–457. doi: 10.1111/bph.12285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Liu X-W, Du F-F, Li M-J, Xu F, Wang F-Q, et al. Sensitive assay for measurement of volatile borneol, isoborneol, and the metabolite camphor in rat pharmacokinetic study of Borneolum (Bingpian) and Borneolum syntheticum (synthetic Bingpian) Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:1337–1348. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis G, Kerem Z, Makkar HPS, Becker K. The biological action of saponins in animal systems: a review. Br J Nutr. 2002;88:587–605. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugh-Berman A. Herb-drug interactions. Lancet. 2000;355:134–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini KM, Huang S-M, Tweedie DJ, Benet LZ, Brouwer KLR, Chu X-Y, et al. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:215–236. doi: 10.1038/nrd3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Li C, Wang G-J, Chen L-S. Rapid and direct measurement of free concentrations of highly protein-bound fluoxetine and its metabolite norfluoxetine in plasma. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:39–47. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Gan X-T, Haist JV, Rajapurohitam V, Zeidan A, Faruq NS, et al. Ginseng inhibits cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and heart failure via NHE-1 inhibition and attenuation of calcineurin activation. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:79–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.957969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z-Y, Yang J-L, Cheng C, Huang Y-H, Du F-F, Wang F-Q, et al. Combinatorial metabolism notably affects human systemic exposure to ginsenosides from orally administered extract of Panax notoginseng roots (Sanqi) Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:1457–1469. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.051391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro N, Maeda K, Kishimoto W, Saito A, Harada A, Ebner T, et al. Predominant contribution of OATP1B3 to the hepatic uptake of telmisartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:1109–1115. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.009175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismair MG, Stanca C, Ha HR, Renner EL, Meier PJ, Kullak-Ublick GA. Interactions of glycyrrhizin with organic anion transporting polypeptides of rat and human liver. Hepatol Res. 2003;26:343–347. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(03)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji HY, Lee HW, Kim HK, Kim HH, Chang SG, Sohn DH, et al. Simultaneous determination of ginsenoside Rb1 and Rg1 in human plasma by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2004;35:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y-L, Huang F-Y, Zhang S-K, Leung S-W. Is danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) dripping pill more effective than isosorbide dinitrate in treating angina pectoris? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Inter J Cardiol. 2012;157:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallioloski A, Niemi M. Impact of OATP transporters on pharmacokinetics. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:693–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmazyn M, Moey M, Gan XT. Therapeutic potential of ginseng in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Drugs. 2011;71:1989–2008. doi: 10.2165/11594300-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König J, Muller F, Fromm MF. Transporters and drug-drug interactions: important determinants of drug disposition and effects. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:944–966. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.007518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullak-Ublick GA, Ismair MG, Stieger B, Landmann L, Huber R, Pizzagalli F, et al. Organic anion-transporting polypeptide B (OATP-B) and its functional comparison with three other OATPs of human liver. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:525–533. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung K-W, Ng H-M, Tang MKS, Wong CCK, Wong RNS, Wong AST. Ginsenoside-Rg1 mediates a hypoxia-independent upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a to promote angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2011;14:515–522. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9235-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Cheng Y-K, Mak NK, Chan KKC, Fand TPD, Wong RNS. Signaling pathway of ginsenoside-Rg1 leading to nitric oxide production in endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3211–3216. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Leung FP, Huang Y, Mak NK, Wong RNS. Non-genomic effects of ginsenoside-Re in endothelial cells via glucocorticoid receptor. FEBS Lett. 2007a;581:2423–2428. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Cheung LWT, Pon YL, Wong RNS, Mak NK, Fan T-PD, et al. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibits tube-like structure formation of endothelial cells by regulating pigment epithelium-derived factor through the oestrogen β receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2007b;152:207–215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G-X, Jiang C-M, Xia S-X, Tang S, Zhang S-L, Wang Y-M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of Shengmai and Shenmai injection in healthy volunteers. Chin J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:432–434. [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhang J-L, Sheng Y-X, Guo D-A, Wang Q, Guo H-Z. Simultaneous quantification of six major active saponins of Panax notoginseng by high-performance liquid chromatography-UV method. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2005;38:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H-F, Yang J-L, Du F-F, Gao X-M, Ma X-T, Huang Y-H, et al. Absorption and disposition of ginsenosides after oral administration of Panax notoginseng extract to rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2290–2298. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.029819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos U, Musch E, Jensen JC, Mikus G, Schwabe HK, Eichelbaum M. Pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous rifampicin during chronic administration. Klin Wochenschr. 1985;63:1205–1211. doi: 10.1007/BF01733779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü J-M, Yao Q, Chen C. Ginseng compounds: an update on their molecular mechanisms and medical applications. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2009;7:293–302. doi: 10.2174/157016109788340767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moey M, Gan XT, Huang CX, Rajapurohitam V, Martinez-Abundis E, Lui EM, et al. Ginseng reverses established cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and postmyocardial infarction-induced hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:504–514. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.967489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TB. Pharmacological activity of sanchi ginseng (Panax notoginseng. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006;58:1007–1019. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.8.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer ND, Hardwick RN, Brouwer KL. Role of hepatic efflux transporters in regulating systemic and hepatocyte exposure to xenobiotics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;54:24.1–24.27. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-140021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Toh S-A, Sellers LA, Skepper JN, Koolwijk P, Leung H-W, et al. Modulating angiogenesis: the yin and the yang in ginseng. Circulation. 2004;110:1219–1225. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140676.88412.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Q-H, Xu H, Liu Z-L, Chen K-J, Liu J-P. Oral Panax notoginseng preparation for coronary heart disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2013/940125. ; article ID 940125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S-J, Klotz U. Drug interactions with herbal medicines. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51:77–104. doi: 10.2165/11597910-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NF, Acharya MR, Desai N, Figg WD, Sparreboom A. Identification of OATP1B3 as a high-affinity hepatocellular transporter of paclitaxel. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:815–818. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.8.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparg SG, Light ME, Staden JV. Biological activities and distribution of plant saponins. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;94:219–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Xiao J, Sun X-B, Wu Y. Notoginsenoside R1 attenuates cardiac dysfunction in endotoxemic mice: an insight into oestrogen receptor activation and PI3K/Akt signaling. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:1758–1770. doi: 10.1111/bph.12063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachjian A, Maria V, Jahangir A. Use of herbal products and potential interactions in patients with cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taimeh Z, Loughran J, Briks EJ, Bolli R. Vascular endothelial growth factor in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:519–530. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamargo J, López-Sendón J. Novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of heart failure. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:536–555. doi: 10.1038/nrd3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavricka SR, Montfoort JV, Ha HR, Meier PJ, Fattinger K. Interactions of rifamycin SV and rifampicin with organic anion uptake systems of human liver. Hepatology. 2002;36:164–172. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Pan X-L, Sweet DH. The anthraquinone drug rhein potently interferes with organic anion transporter-mediated renal elimination. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-X, Guo C-X, Qu Q, Yu J, Chen W-Q, Wang G, et al. Effects of natural products on the function of human organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1. Xenobiotica. 2012;42:339–348. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2011.623796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Chen F, Li C. Absorption, disposition, and pharmacokinetics of saponins from Chinese medicinal herbs: what do we know and what do we need to know more? Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13:577–598. doi: 10.2174/1389200211209050577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W-M, Sandoval R-M, Molitoris B-A. Rapid determination of renal filtration function using an optical ratiometric imaging approach. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1873–F1880. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00218.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaher H, zu Schwabedissen HEM, Tirona RG, Cox ML, Obert LA, Agrawal N, et al. Targeted disruption of murine organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1b2 (Oatp1b2/Slco1b2) significantly alters disposition of prototypical drug substrates pravastatin and rifampin. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:320–329. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A-J, Wang C-Y, Liu Q, Meng Q, Peng J-Y, Sun H-J, et al. Involvement of organic anion-transporting polypeptides in the hepatic uptake of dioscin in rats and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:994–1003. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.049452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Supplemental methods.

Appendix S2 Protein expression of OATP1B1, OATP1B3 and Oatp1b2 in transfected HEK293 cells and mRNA levels of MRP2, BCRP, BSEP, MDR1, Mrp2, Bcrp and Bsep in membrane vesicles.

Appendix S3 Time courses for accumulation of the ppt-type ginsenosides in HEK293 cells expressing human OATP1B3 or rat Oatp1b2.

Appendix S4 Rifampin inhibition of human OATP1B3- and rat Oatp1b2-mediated uptake of the ppt-type ginsenosides, plasma pharmacokinetics of rifampin in rats and rifampin-mediated drug–drug interactions.

Appendix S5 Rat tissue distribution of ginsenosides.

Appendix S6 Content levels of ginsenosides in herbal injections.