Abstract

Fungi belonging to the genus Trichoderma, commonly found in soil or colonizing plant roots, exert beneficial effects on plants, including the promotion of growth and the induction of resistance to disease. T. virens and T. atroviride secrete the proteins Sm1 and Epl1, respectively, which elicit local and systemic disease resistance in plants. In this work, we show that these fungi promote growth in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants. T. virens was more effective than T. atroviride in promoting biomass gain, and both fungi were capable of inducing systemic protection in tomato against Alternaria solani, Botrytis cinerea, and Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst DC3000). Deletion (KO) of epl1 in T. atroviride resulted in diminished systemic protection against A. solani and B. cinerea, whereas the T. virens sm1 KO strain was less effective in protecting tomato against Pst DC3000 and B. cinerea. Importantly, overexpression (OE) of epl1 and sm1 led to an increase in disease resistance against all tested pathogens. Although the Trichoderma WT strains induced both systemic acquired resistance (SAR)- and induced systemic resistance (ISR)-related genes in tomato, inoculation of plants with OE and KO strains revealed that Epl1 and Sm1 play a minor role in the induction of these genes. However, we found that Epl1 and Sm1 induce the expression of a peroxidase and an α-dioxygenase encoding genes, respectively, which could be important for tomato protection by Trichoderma spp. Altogether, these observations indicate that colonization by beneficial and/or infection by pathogenic microorganisms dictates many of the outcomes in plants, which are more complex than previously thought.

Keywords: Trichoderma, tomato, Sm1/Epl1, biotrophic phytopathogen, necrotrophic phytopathogen, systemic acquired resistance, induced systemic resistance

Introduction

To counteract pathogens, plants have developed several layers of immune responses, including detection of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that induce PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI). In turn, pathogens have evolved effector molecules to suppress PTI to survive and spread into the host. Facing this challenge, plants have developed resistance proteins (R) that recognize pathogen effectors and promote effector-triggered immunity (ETI) (Chisholm et al., 2006; Katiyar-Agarwal and Jin, 2010). Furthermore, plants have developed the ability to enhance their basal resistance after detection of a pathogen. This response includes systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR) that are phenotypically similar but significantly different at the genetic and biochemical levels. SAR is associated with the accumulation of salicylic acid (SA) (Durrant and Dong, 2004; Glazebrook, 2005), whereas ISR is a response to the accumulation of jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) (Ton et al., 2002). The SA-related defense response is triggered against biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens, such as Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000), which feeds on living host tissue, and is accompanied by the accumulation of pathogenesis-related proteins (PR) (Van Loon and Van Strien, 1999; Durrant and Dong, 2004; Glazebrook, 2005). The JA/ET-related defense response is boosted by necrotrophic microorganisms such as Botrytis cinerea, which kills the host tissue at early stages of the invasion (Ton et al., 2002); genes related to ISR such as PDF1.2 and LOX-2 are induced upon infection by these type of pathogens. Beneficial soilborne microorganisms such as rhizobacteria, mycorrhizae, and non-pathogenic fungi can also induce plant systemic resistance against a broad spectrum of microbial pathogens, where JA/ET have shown to be the major players (Van Wees et al., 2008).

Fungi belonging to the Trichoderma genus are free-living organisms commonly found in soil, decaying wood, or colonizing the plant root surface (Brotman et al., 2010; Druzhinina et al., 2011; Hermosa et al., 2012). Root colonization by Trichoderma provides significant beneficial effects to plants, including changes in root architecture, growth enhancement, and an increase in productivity (Baker et al., 1984; Chang et al., 1986; Harman, 2000). Activation of systemic resistance against phytopathogens by Trichoderma has been reported for both monocot (Djonovic et al., 2007; Shoresh and Harman, 2008) and dicot plants (Yedidia et al., 2003; Shoresh et al., 2005; Viterbo et al., 2005; Djonovic et al., 2006). This response was described as the closest analog of the ISR activated by rhizobacteria, and is associated with the accumulation of JA/ET, and the transcription of ISR-related genes (Bakker et al., 2003; Van Loon, 2007). Contrasting data have shown that T. longibrachiatum induces the expression of PR genes (Martinez et al., 2001). Even though SA and JA/ET pathways are mutually antagonistic, evidences of synergistic interactions have been demonstrated (Mur et al., 2006). Recently, simultaneous induction of genetic markers from the SAR and ISR pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana by Trichoderma has been reported (Contreras-Cornejo et al., 2011; Salas-Marina et al., 2011). Additional studies in more plants have shown simultaneous induction of the SA and JA/ET pathways by other Trichoderma species (Mathys et al., 2012; Perazzolli et al., 2012; Cai et al., 2013; Olmedo-Monfil and Casas-Flores, 2014). Recently, it was shown that intact JA, ET and abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathways are required for functional induction of systemic resistance in tomato plants against B. cinerea (Martínez-Medina et al., 2013).

At the beginning of plant root colonization, Trichoderma is probably recognized initially as foreign, through its microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), which lead to the induction of plant systemic resistance. Indeed, growing evidence suggests that during the plant-Trichoderma interaction a molecular dialog takes place, likely mediated by molecules produced by both the plant and Trichoderma (Pozo et al., 2005). A number of MAMPs have been characterized in these fungi, including oligosaccharides, low molecular weight compounds, proteins with enzymatic activity, swollenins, peptaibols, and cerato-platanins (Bailey et al., 1991; Baker et al., 1997; Djonovic et al., 2006; Viterbo et al., 2007; Brotman et al., 2008). Among these molecules, the Sm1 (small protein -1) from T. virens and its homologous Epl1 (eliciting plant response-like) from T. atroviride are of particular interest. They are proteinaceous non-enzymatic elicitors of plant disease resistance that belong to the cerato-platanin family, and are abundantly expressed in the absence of plants (Djonovic et al., 2006, 2007; Seidl et al., 2006). However, their expression increases in the presence of plants, and their products are secreted at the early stages of their interaction, suggesting a signaling role of such proteins during these relationships (Djonovic et al., 2006; Vargas et al., 2008). In support of this hypothesis, purified Sm1 protein was found to induce locally and systemically the cotton defense response, whereas the expression of sm1 was shown to be essential for the induction of systemic resistance in maize against the foliar pathogen Colletotrichum graminicola. The proteins Sm1 and Epl1 are produced mainly as monomer and a dimer, respectively, in the presence of maize plants, but the monomeric form is responsible for the induction of systemic resistance (Vargas et al., 2008). The protective activity of Sm1 has been associated with the induction of the JA pathway and green leaf volatile-biosynthetic genes (Djonovic et al., 2006).

The present study was conducted to investigate the effects of T. atroviride and T. virens on the growth and the induction of systemic disease resistance against different foliar pathogens in tomato plants. Furthermore, we studied the effect of the Sm1 and Epl1 elicitors on disease resistance in the same plants. For this purpose, we generated sm1 and epl1 overexpression (OE) and knockout (KO) strains of the two fungi. Then, we determined the induction of systemic disease resistance against different pathogens and measured the expression of tomato defense-related genes after inoculation with the different Trichoderma strains. These data enabled us to establish new insights into systemic disease resistance induced by Trichoderma spp. and the role of the Sm1 and Epl1 elicitors in this process.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and growth conditions

T. virens Gv29-8 (Baek and Kenerley, 1998) and T. atroviride IMI 206040 were used throughout this study. B. cinerea and A. solani strains were isolated from a tomato plant in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, and identified by PCR amplification of 18S rDNA using the oligonucleotides ITS1 and ITS4 (White et al., 1990). Fungal strains were routinely maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and hygromycin was added at 200 μg/ml when necessary. Pst DC3000 (Cuppels, 1986) was routinely grown on King's B medium (King et al., 1954). Escherichia coli Top 10 F' was routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar plates. Carbenicillin (100 μg/ml) was added to LB when necessary. E. coli Top 10 F' was used for DNA manipulations (Sambrook and Russell, 2001).

Plant-growth promotion assay

Tomato seeds were plated on 0.3× MS (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) and, 4 days after germination, seedlings were transplanted to flowerpots containing peat moss as substrate (LAMBERT™), and roots were inoculated with 20μl of 1 × 106 spores ml−1 of T. atroviride or T. virens. One day post-inoculation (dpi), flowerpots were irrigated with liquid MS (0.3×) to allow the fungus to colonize the rhizosphere. Six dpi, plants were supplied with nutrient solution HUMIFERT (Cosmocel, Monterrey, NL, Mexico) (0.3%). Twenty-one dpi with Trichoderma, control and treated plants were carefully removed from containers and roots were washed in sterile distilled water. Plant length was measured with a ruler and fresh weight was determined on an analytical scale. Then, plants were air-dried at 70°C for 72 h to further measure the dry weight on an analytical scale. Each treatment consisted of 15 plants, and the experiment was repeated three times.

Protection assay against fungal and bacterial phytopathogens induced by T. atroviride and T. virens strains

Phytopathogenic fungi were grown for 7 days on PDA at 28°C with a 12 h photoperiod. Conidia were harvested and suspended in sterile distilled water. Conidia were counted by using a hematocytometer and the spore suspension was adjusted to 1 × 106 and 1 × 105 conidia ml−1 for B. cinerea and for A. solani, respectively. Pst DC3000 was grown in King's B medium at 200 rpm for 48 h at 28°C and the suspension was adjusted to OD = 0.2. Break-Thru (Goldsmidt Chemical Corporation) was added to a final concentration of 0.1% as surfactant agent. Tomato plants used for protection assays were grown as described for plant growth promotion trials. Twenty-one dpi of tomato with the different Trichoderma strains, the plants were inoculated with B. cinerea, A. solani, or P. syringae. For each treatment, we used 8 plants. Three leaves from each plant were inoculated with 10 μl of the pathogen suspension on the adaxial side and on the mid vein of the leaf. Inoculated plants were placed in the greenhouse under controlled conditions and irrigated daily. Eight dpi with the pathogen, leaf damage area was measured with a transparent grid (4 mm2 grid squares). Percentage of leaves damage area was calculated obtaining the total leaf area and the total damaged leaf area, the ratio between these values gave the percentage of damaged area. Each experiment was repeated three times. Experimental data were subjected to analysis of variance, setting significance at P-values < 0.0001, LSD range test < 0.05.

Generation of sm1 and epl1 overexpression and deletion constructs

Total DNA from T. virens and T. atroviride was extracted as described by Raeder and Broda (1989). The sm1 and epl1 gene deletion constructs were generated through the double-joint PCR tool (Yu et al., 2004). In a first round of PCR, ~1.5 kb of each of 5′- and 3′-flanking regions for the sm1 and epl1 open reading frames were amplified from genomic DNA from T. virens and T. atroviride, respectively, using the primers enlisted in Table 1. The 1.4-kb hph cassette was PCR-amplified from the plasmid pCB1004 (Carroll et al., 1994) using primers hph-f and hph-r (Table 1). The sm1 and epl1 5′ and 3′ open reading frame flanking regions were mixed with the hph amplicon in a 1:1:3 molar ratios and the second round of PCR was performed as described elsewhere (Yu et al., 2004). For generating sm1 and epl1 overexpression strains, the primers listed in Table 1, were used to amplify the sm1 and epl1 genes (Table 1). The forward and reverse primers included the Xba I and Nsi I restriction sites, respectively. The sm1 and epl1 amplicons were double digested with Xba I and Nsi I and cloned into the pGFP-Hyg vector in their corresponding restriction sites under regulation of the pyruvate kinase gene (pki) promoter from T. reesei (Zeilinger et al., 1999; Casas-Flores et al., 2006). PCR amplification of sm1/epl1 was carried out under the following conditions (°C/t): 1 cycle 94/5 min, 25 cycles 94/30 s, 60/30 s, 72/30 s, and one final cycle of 72/10 min. The PCR products were verified by sequencing.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this work.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Gene amplified | GenBank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tasm1OE-f | GCTCTAGAATGCAACTGTCCAACATCTTCACTC | epl1 | AJ901879.1 |

| Tasm1OE-r | CCAATGCATTTAGAGACCGCAGTTCTTAACAGG | epl1 | AJ901879.1 |

| Tvsm1OE-f | GCTCTAGAATGCAGTTCTCCAGCCTCTTCAAG | sm1 | DQ121133.1 |

| Tvsm1OE-r | CCAATGCATTTAGAGGCCGCAGTTGCTCACAGC | sm1 | DQ121133.1 |

| Tasm1KO5′-f | CGGGATCCGCACTGGGTAGATGCTGGTCTG | epl1 | AJ901879.1 |

| Tasm1KO5′-r | CTCCTTCAATATCAGTTAACGTCGATCCTGAGTAGTGAAGCGAATGTGCTG | epl1 | AJ901879.1 |

| Tasm1KO3′-f | CAGCACTCGTCCGAGGGCAAAGGAATAGCGGAGCAATGTAAGCAGATCGAC | epl1 | AJ901879.1 |

| Tasm1KO3′-r | CCGCTCGAGCCTTACTGCAAAGGGTCTGGATGC | epl1 | AJ901879.1 |

| Tvsm1KO5′-f | GCTCTAGAACAATGCCGGTAGTACACCGTTCG | sm1 | DQ121133.1 |

| Tvsm1KO5′-r | CTCCTTCAATATCAGTTAACGTCGATCGGGTACAGCAAACTGACTCGTCAC | sm1 | DQ121133.1 |

| Tvsm1KO3′-f | CAGCACTCGTCCGAGGGCAAAGGAATAGCGACCAGTAAACCGCCATTCATCG | sm1 | DQ121133.1 |

| Tvsm1KO3′-r | CCGCTCGAGGGACTTGTCGAATTTCCCATCTCG | sm1 | DQ121133.1 |

| Ta-TEF-1-Fw | AGGCCGAGCGTGAGCGTGGTAT | ef-1 alpha | ID 146236 |

| Ta-TEF-1-Rv | ATGGGGACGAAGGCAACGGTCTT | ef-1 alpha | ID 146236 |

| hph-f | GATCGACGTTAACTGATATTGAAGGAG | hph | X03615.1 |

| hph-r | CTATTCCTTTGCCCTCGGACGAGTGCTG | hph | X03615.1 |

| GLUA-F | GTGAAGCTGGTTTGGGAAATG | SlGLUA | M80604.1 |

| GLUA-R | TTGCCAATCAACGTCATGTCTAC | SlGLUA | M80604.1 |

| PR-5-F | GGTGCCAGACTGGTGATTGTG | SlPR-5 | AY093595.1 |

| PR-5-R | TTGGTGGTTTACCCCATCCTT | SlPR-5 | AY093595.1 |

| DOX1-F | TCACACCATAGATTGGACTGTTCA | Slα-DOX1 | AY344539.1 |

| DOX1-R | GGCACGCATTCCTGCAA | Slα-DOX1 | AY344539.1 |

| CHI9-F | AACGCGGGAATTGTTCGA | SlCHI9 | Z15140.1 |

| CHI9-R | GCAGGACATGCGTCATTGTT | SlCHI9 | Z15140.1 |

| TLRP-F | TGCGGTGAAATTGGATAACG | SlTLRP | X77373.1 |

| TLRP-R | GCCATAGCCCTTGCCATAATAA | SlTLRP | X77373.1 |

| CEVI16-F | AACGGAGATGGCTCGAAGCGTG | SlCEVI16 | X94943.1 |

| CEVI16-R | CATCGGTCCACAATATCTGGTCTG | SlCEVI16 | X94943.1 |

| ACT-f | GCTGCAGGTATCCACGAGACTACC | SlTOM51 | U60481.1 |

| ACT-r | GAT TTC CTT GCT CAT ACG GTC AGC | SlTOM51 | U60481.1 |

a Restriction sites are indicated as underlined letters.

Genetic transformation of T. atroviride and T. virens protoplasts

Protoplasts of T. virens and T. atroviride were transformed with overexpression and deletion constructs, as described elsewhere (Baek and Kenerley, 1998). Stable transformants were selected by three consecutive transfers of a single colony to PDA medium plus 200 μg/ml hygromycin. To estimate the sm1 gene replacement and the copy numbers of the overexpression strains, the 2−ΔΔCt method was assessed (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Genomic DNA extracted from wild-type strains was used as calibrator, whereas ef-1 alpha gene served as housekeeping in all experiments. After validation of the method, results were expressed in N-fold changes in the target gene copies normalized to ef-1 alpha relative to the copy number of the target gene in T. virens and T. atroviride using the equation 2−ΔΔCt (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Two experiments were carried out for each sample in triplicate and the Ct was recorded. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green Fast SYBR technology on the 7500 FAST Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), following the default PCR program.

RT-qPCR analysis of the sm1 and epl1 overexpression and deletion strains

The different Trichoderma strains were grown on PDA plates overlaid with a sterile cellophane sheet, incubated for 3 days at 28°C, and mycelia were harvested for total RNA extraction using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, 2 μg of total RNA was treated with rDNase I (Ambion) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA with SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) using oligo-dT primer. The synthesized cDNAs concentration were checked in a Nanodrop spectrophometer (Thermo Scientific) and used as template for real time RT-PCR.

Expression analysis of tomato defense related genes

Fourteen-day-old plants grown in Petri dishes containing MS medium were inoculated with 10 μl of 1 × 106 conidia ml−1 of T. virens WT, TvOE2.2, TvKO2, T. atroviride WT, TaOE2.1, and TaKO9 strains. At 72 h post Trichoderma inoculation, tomato roots and leaves were separated and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted by using the Concert RNA extraction reagent (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer. Total RNA (2 μg) was DNase-treated using rDNase I (Ambion) and reverse-transcribed with SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), and used for real-time RT-PCR as described before. Six tomato genes related to different plant defense pathways were selected from a subtractive library (SlCHI9, SlTLRP, Slα-DOX1, SlPR-5, SlGLUA) (this work) and two from the GenBank database (SlCEVI16, SlTOM51) (Table 1). The subtraction was performed using total RNA from TaOE2.1-treated tomato plants against TaKO9-treated tomato plants. BLAST searches against GeneBank of selected sequences from the subtractive library were performed. The SAR-related genes were: acidic isoform class II β-1, 3-glucanase (SlGLUA), osmotin-like (SlPR-5). The ISR-related genes were: Class I basic endochitinase (SlCHI9), secreted peroxidase (SlCEVI16), α–dioxygenase (Slα-DOX1), tomato cell wall protein (SlTLRP) (related to induced systemic resistance and oxidative burst). Actin gene, SlTOM51, was selected as the housekeeping gene (Table 1). Seven primer pairs were designed, using the Primer Express 3 Software (Applied Biosystems) (Table 1).

Results

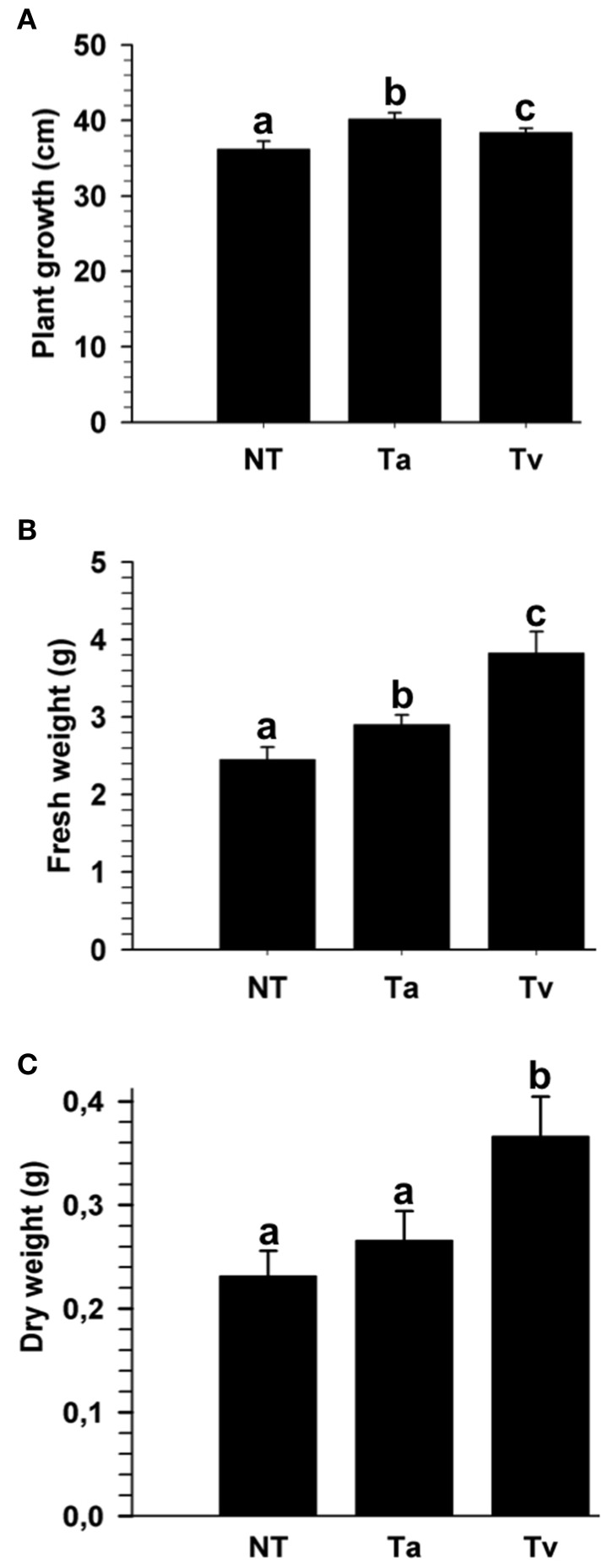

T. virens and T. atroviride promote growth in tomato (solanum lycopersicum)

Beneficial effects of several Trichoderma strains, including T. atroviride (IMI 206040) and T. virens (TvG29-8), on plants have been reported; however, to the best of our knowledge, these strains have not been tested in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). To evaluate the effect of T. atroviride and T. virens on the growth of tomato plants, 4 days old tomato seedlings were either root treated or not with a conidial suspension of one of the two fungi. After twenty-one dpi with Trichoderma, the plant growth and fresh and dry weights were determined. Seedlings treated with either Trichoderma species were higher than mock plants (Figure 1 and Figure S1). However, seedlings treated with T. virens showed a marked increase in fresh and dry weight compared to plants inoculated with T. atroviride (Figure 1 and Figure S1).

Figure 1.

T. atroviride and T. virens wild-type strains promote growth of tomato plants. Twenty-one dpi with T. atroviride (Ta) or T. virens (Tv), the entire plant length was measured (A); and fresh weight (B) and dry weight were determined (C). Non-Trichoderma inoculated (NT) results are representative of three independent experiments. Letter indicates statistically significant differences (analysis of variance, P < 0.0001, LSD range test < 0.05).

Generation of epl1 and sm1 deletion and overexpression strains

To determine if the Epl1 and Sm1 proteins play a role in the induction of systemic disease resistance in tomato, epl1- and sm1-deletion (KO) and overexpression strains (OE) were generated by gene replacement and by transformation with constructs bearing the sm1 or epl1 genes under the control of the piruvate kinase (pki) constitutive promoter from T. reesei (Zeilinger et al., 1999). Two KO candidate strains for T. atroviride (TaKO9 and TaKO11) and two for T. virens (TvKO2 and TVKO6) were selected, whereas three T. atroviride OEs transformants (TaOE1.1, TaOE2.1, and TaOE3.1) and three for T. virens (TvOE2.1, TvOE2.1, and TvOE6.2) were selected. The T. atroviride and T. virens KO, OE, and wild-type strains were grown on PDA plates for 10 days, and their phenotypes were inspected visually daily. There were no phenotypic differences on growth rate, colony appearance, or conidiation when compared with their respective wild-type strains (data not shown). Deletion and copy number of epl1 and sm1 on the T. atroviride and T. virens genomes of the transformants and wild-type strains were analyzed with qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction) (Table 2). As expected T. virens and T. atroviride KO strains lacked sm1 or epl1, whereas the TvOE2.2, TvOE2.1, and TvOE6.2 strains showed three, four, and seven copies of sm1, respectively, whilst the TaOE1.1, TaOE3.1, and TaOE2.1 strains showed three, four, and five copies of epl1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

epl1 and sm1 copy number and expression levels in the T. atroviride and T. virens OE, KO and wild type strains, calculated with the 2-ΔΔCt method.

| Strain | epl1/sm1 Copy number | epl1 relative expression | sm1 relative expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. atroviride WT | 1 | 1.0 | |

| TaOE1.1 | 3 | 14.2 | |

| TaOE2.1 | 5 | 8.5 | |

| TaOE3.1 | 4 | 4.9 | |

| TaKO9 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| TaKO11 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| T. virens WT | 1 | 1.0 | |

| TvOE2.1 | 4 | 4.6 | |

| TvOE2.2 | 3 | 8.1 | |

| TvOE6.2 | 7 | 0.5 | |

| TvKO2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| TvKO6 | 0 | 0.0 |

Gene expression analysis of epl1 and sm1 in the OE and KO strains

To test if the sm1 and epl1 copy number of the OE strains correlates with the transcription levels of sm1 and epl1, total RNA from the different strains was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-qPCR). The TaOE1.1, TaOE2.1, and TaOE3.1 strains showed 14.2-, 8.5-, and 4.9-fold (Table 2) transcript levels, whereas the TvOE2.1, TvOE2.2 and TvOE6.2 strains showed 4.6-, 8.1-, and 0.5-fold transcript levels (Table 2). Interestingly, with more than three copies of genes epl1 or sm1, transcript levels of these genes were lower than with three copies (Table 2). The KO strains showed no epl1 or sm1 transcript in the corresponding strains (Table 2).

Sm1 and epl1 differentially modulate the induction of systemic disease resistance against different pathogens in tomato plants

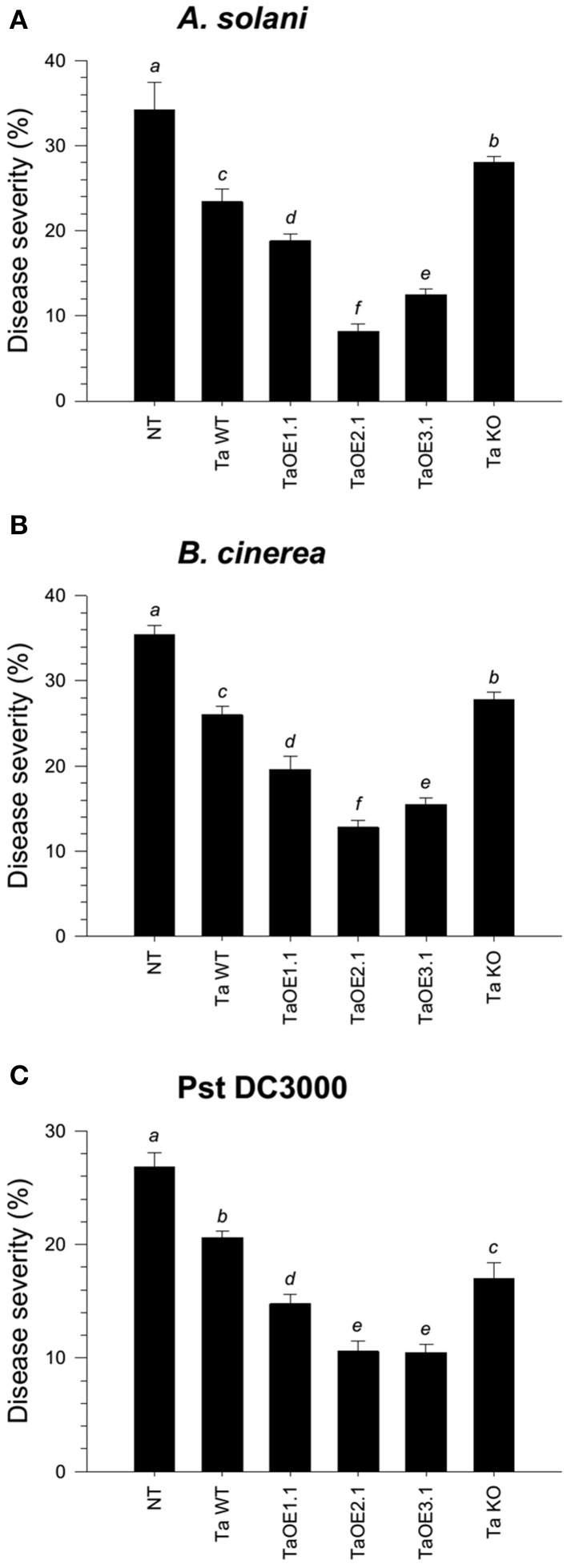

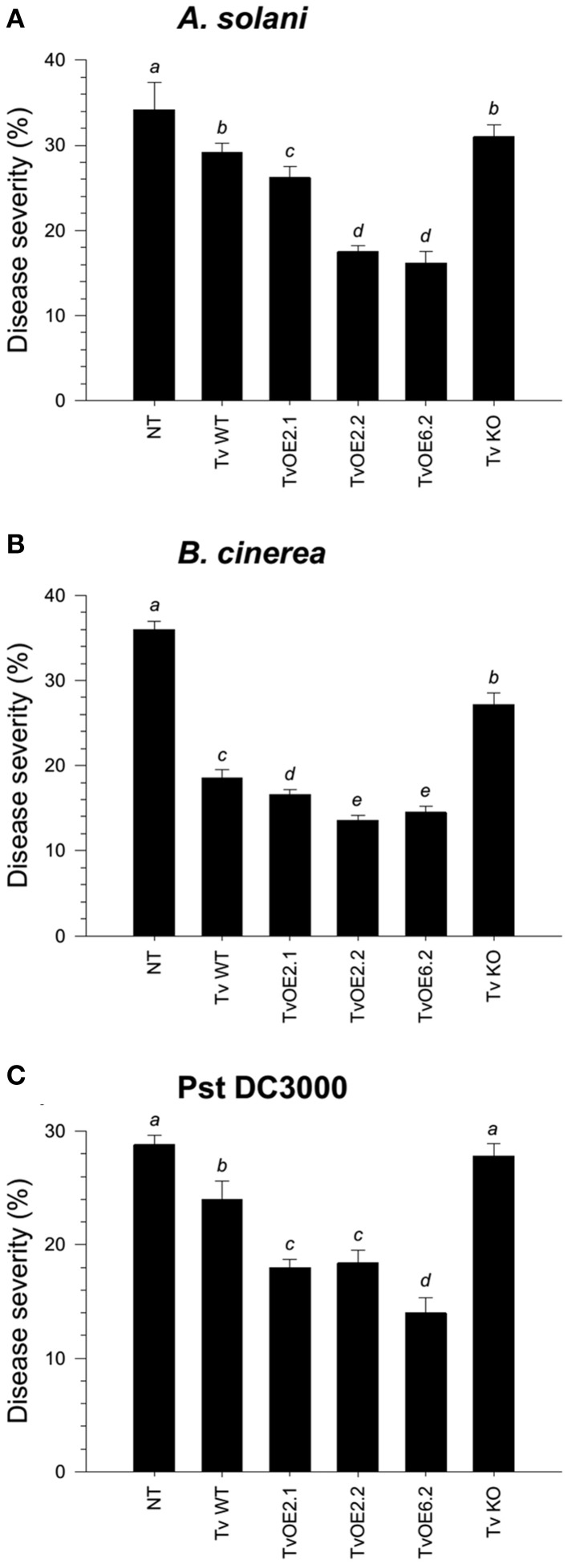

To assess the ability of the different Trichoderma strains to systemically protect tomato seedlings against three different foliar pathogens, roots of four-day-old seedlings were inoculated with the whole set of strains. Tomato leaves after twenty-one dpi with Trichoderma were infected with a conidial suspension of Alternaria solani or Botrytis cinerea, or with a bacterial suspension of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst DC3000). Disease lesions on tomato leaves were evaluated eight dpi and the mean of percentage of leaf area damaged was then calculated. The mocked seedlings, inoculated with A. solani, showed 34.2% of leaf damage, whereas the T. atroviride and T. virens wild-type strains-treated seedlings, infected with A. solani, showed 23.4% (Figure 2A and Figure S2A) and 29.2% (Figure 3A and Figure S3A) of foliar damage, respectively. The TaOE2.1 treated seedlings infected with A. solani showed only 8.2% of foliar damage followed by TaOE3.1- (12.5%) and TaOE1.1- (18.8%) treated plants (Figure 2A and Figure S2A). Seedlings pre-treated with the TaKO9 presented more damage (28%) when compared to the WT strain-treated seedlings, but did not present the same damage as the T. atroviride non-treated plants (Figure 2A and Figure S2A). The TvOE2.2- and TvOE6.2-treated seedlings showed 17.5 and 16.2% of foliar damage, followed by the TvOE2.1- and TvKO2-treated seedlings, which showed 26.2%, and 31% of foliar damage, respectively (Figure 3A and Figure S3A).

Figure 2.

Epl1 plays a major role in the induction of disease resistance against necrotrophic, but a minor role against hemibiotrophic phytopathogens in tomato. Twenty-one dpi of tomato with T. atroviride WT, TaOE1.1, TaOE2.1, TaOE3.1 and TaKO9 strains, tomato leaves were inoculated with B. cinerea (A), A. solani (B), and Pst DC3000 (C). Non-Trichoderma inoculated (NT) foliar damage was evaluated 8 dpi with the phytopathogen, taking the damaged area of three inoculated leaves from a total of eight plants. Each bar represents an average of three independent experiments given as arbitrary units. Letter indicates statistically significant differences (analysis of variance, P < 0.0001, LSD range test < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Sm1 plays a minor role in the induction of disease resistance against necrotrophic, but a major role against hemibiotrophic phytopathogens in tomato. Twenty-one dpi of tomato with T. virens WT, TvOE2.1, TvOE2.2, TvOE6.2 and TvKO2 strains, tomato leaves were inoculated with B. cinerea (A), A. solani (B), and Pst DC3000 (C). Non-Trichoderma inoculated (NT) foliar damage was evaluated 8 dpi with the phytopathogen, taking the damaged area of three inoculated leaves from a total of eight plants. Each bar represents an average of three independent experiments given as arbitrary units. Letter indicates statistically significant differences (analysis of variance, P < 0.0001, LSD range test < 0.05).

When infected with B. cinerea, the T. atroviride and T. virens wild-type strains-treated seedlings showed 26% (Figure 2B and Figure S2B) and 18.6% (Figure 3B and Figure S3B) of foliar damage, respectively. TaOE2.1 conferred high levels (12.8% of foliar damage) of protection against B. cinerea, followed by TaOE3.1 (15.5%) and TaOE1.1 (19.6%), respectively (Figure 2B and Figure S2); TvOE2.2 and TvOE6.2 conferred similar protection (~14%), followed by TvOE2.1 (16.6%) (Figure 3B and Figure S3). TaKO9-treated seedlings showed 28% of foliar damage when infected with B. cinerea (Figure 2B and Figure S2B), and TvKO2-treated seedlings showed 27.2% of foliar damage (Figure 3B and Figure S3B). However, none of the T. atroviride or T. virens KO treated plants reached the foliar damage observed in the mock plants (Figures 2B, 3B).

Control plants inoculated with P. syringae presented ~28% of leaf damage, whereas root inoculated T. atroviride (Figure 2C and Figure S2C) and T. virens (Figure 3C and Figure S3C) tomato plants showed reduced foliar damage (20.6 and 24%, respectively). The tomato foliar damage provoked by Pst DC3000 was considerably reduced with similar results (10.5%) by TaOE2.1 and TaOE3.1, followed by TaOE1.1 (14.8%) (Figure 2C and Figure S2C). Unexpectedly, the TaKO9 strain-treated plants showed less foliar damage (17%) than those treated with the T. atroviride wild-type strain (Figure 2C and Figure S2C). The TvOE6.2-treated seedlings infected with Pst DC3000 displayed 14% of foliar damage, followed by TvOE2.1 and TvOE2.2 treated plants with similar results (~18%) (Figure 3C and Figure S3C). Foliar damage of TvKO2-treated seedlings was similar (27.8%) to that of the control seedlings without Trichoderma, but inoculated with Pst DC3000 (Figure 3C and Figure S3C).

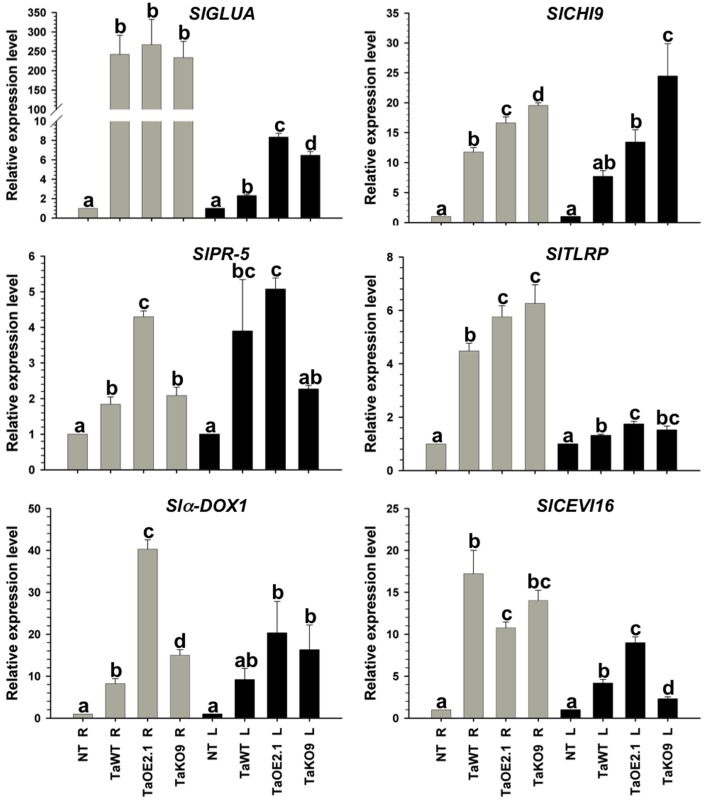

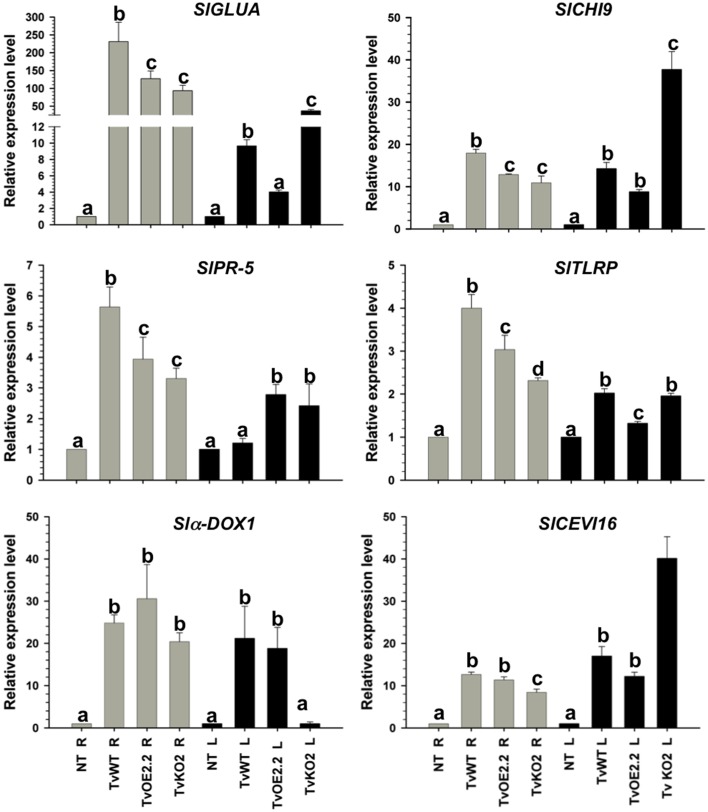

Sm1 and epl1 differentially modulate defense-related genes in tomato plants

To assign a role to the sm1 and epl1 products in the protection of tomato plants against the different pathogens tested, tomato seedlings were root inoculated with the T. atroviride wild-type, TaOE2.1, or TaKO9 strain; and the T. virens wild-type, TvOE2.2 or TvKO2 strain. Total RNA was extracted from roots and leaves 48, 72, and 96 hpi, and expression of the SAR- and ISR-related genes SlGLUA and SlCHI9, respectively, were tested by endpoint RT-PCR, detecting maximum expression at 72 hpi with all tested strains (data not shown). Consequently, the 72 hpi point was chosen to further analyze expression of the SAR- (SlGLUA and SlPR5) and ISR-related genes (SlCHI9, SlCEVI16, Slα-DOX1, and SlTLRP) by RT-qPCR, both, locally (in roots) and systemically (in leaves) (Figures 4, 5).

Figure 4.

Epl1 differentially modulates SAR and ISR-related genes in tomato but it is dispensable to induce almost all genes. Total RNA from roots (R) and leaves (L) of 14-day-old tomato plants inoculated with TaOE2.1 and TaKO9 along with the T. atroviride wild-type strain was extracted at 72 h post-inoculation and subjected to RT-qPCR. Non-Trichoderma inoculated (NT). Gray bars show relative expression in roots, whereas black bars represent relative expression in leaves. Expression profile of two tomato SAR-related genes (SlGLUA and SlPR-5), and four ISR-related genes (Slα-DOX1, SlCH19, SlTLRP, and SlCEVI16) was determined. Actin gene SlTOM51 was used as housekeeping gene. Letter indicates statistically significant differences (analysis of variance, P < 0.0001, LSD range test < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Sm1 differentially modulates SAR and ISR-related genes in tomato but it is dispensable to induce almost all genes. Total RNA from roots (R) and leaves (L) of 14-day-old tomato plants inoculated with TvOE2.2 and TaKO2 along with the T. virens wild-type strain was extracted at 72 h post-inoculation and subjected to RT-qPCR. Non-Trichoderma inoculated (NT). Gray bars show relative expression in roots, whereas black bars represent relative expression in leaves. Expression profile of two tomato SAR-related genes (SlGLUA and SlPR-5), and four ISR-related genes (Slα-DOX1, SlCHI9, SlTLRP, and SlCEVI16) was determined. Actin gene SlTOM51 was used as housekeeping gene. Letter indicates statistically significant differences (analysis of variance, P < 0.0001, LSD range test < 0.05).

Almost all selected genes were upregulated in roots of plants treated with all tested strains, whereas in leaves they were induced to a lesser extent (Figures 4, 5). The exception to this transcription pattern was the SlCHI9 gene in leaves of TaKO9- and TvKO2-treated seedlings, where these strains induced higher transcript levels than those detected for their respective wild-type and OE strains. The SlCEVI16 gene also showed higher levels of transcript in TvKO2-treated seedlings compared with its corresponding wild-type and OE strains (Figures 4, 5).

The whole set of T. atroviride strains induced highest levels of SlGLUA, SlPR-5, and Slα-DOX1 in roots and leaves of tomato seedlings compared to the mock case (Figure 4). Although no statistically significant differences were found between SlGLUA in TaOE2.1, TaKO9 and wild-type strains-treated plants in roots, and leaves (Figure 4). On the other hand, SlPR-5, and Slα-DOX1 genes showed statistically significant differences in roots and leaves of tomato seedlings treated with the same strains (Figure 4). Roots of T. atroviride TaKO9-treated plants showed the highest levels of SlCHI9 and SlTLRP transcription, followed by the TaOE2.1 and wild-type inoculated seedlings. The SlCHI9 gene displayed a similar behavior of transcription in leaves with all tested strains as compared to its expression levels in roots. However, the SlTLRP gene was marginally upregulated in leaves by the TaOE2.1, followed by the TaKO9 and the wild-type treated plants, respectively (Figure 4). The SlCEVI16 gene showed the highest levels of transcript in roots of T. atroviride wild-type strain-inoculated seedlings followed by TaKO9 and TaOE2.1, respectively. Leaves of plants treated with the TaOE2.1 strain showed the highest levels of SlCEVI16 transcript followed by the wild-type and TaKO9 strains, respectively (Figure 4).

Tomato seedlings treated with the T. virens TvKO2 strain showed the lowest levels of transcript for all tested genes in roots, following the induction by the TvOE2.2 and the wild type strains treated plants. The exception to this transcription pattern was the Slα-DOX1 gene in roots, where no statistically significant differences were found between TvOE2.2, TvKO2 and wild-type strains treated seedlings (Figure 5). Tomato plants treated with the TvOE2.2 strain showed the lowest levels of transcript for SlGLUA, SlCHI9, SlTLRP, and SlCEVI16 in leaves, sometimes following the induction by either the wild type or the TvKO2 strains treated plants (Figure 5). The Slα-DOX1 gene, presented the highest levels of transcript in leaves when tomato seedlings were inoculated with the TvOE2.2 and wild type strains, whereas, the TvKO2 was unable to induce the Slα-DOX1 gene in this tissue (Figure 5). The SlPR-5 gene showed the highest levels of transcript in leaves of plants treated with both the TvOE2.2 and the TvKO2 strains followed by the wild-type strain (Figure 5).

Discussion

T. virens and T. atroviride promote growth in tomato

The beneficial effects of some Trichoderma species on plant growth are well-established (Yedidia et al., 1999; Harman et al., 2004; Shoresh et al., 2005). In this investigation, we showed that the plant beneficial fungi T. atroviride (IMI 206040) and T. virens (TvG28-9) differentially promote growth of tomato plants. T. atroviride promoted a marginally higher plant length than T. virens. However, the latter increased significantly more fresh and dry weight than T. atroviride. These results indicated that T. virens is more effective than T. atroviride in promoting biomass gain in tomato plants. Our investigation supports the data reported for the T. atroviride and T. virens interaction with A. thaliana, where both strains induce plant growth (Contreras-Cornejo et al., 2009; Salas-Marina et al., 2011). These direct beneficial effects on plants have also been observed for other Trichoderma species interacting with canola, tomato, and maize seedlings (Yedidia et al., 1999; Harman et al., 2004; Shoresh et al., 2005; Tucci et al., 2010). In this context, Tucci et al. (2010) found some differences in plant growth in several tomato lines induced by T. harzianum T22 and T. atroviride P1, demonstrating that T22 is more effective than P1, and that this feature depends on the tomato genotype. Increasing lines of evidence have shown that the direct effect exerted by Trichoderma on plants is through the production of phytohormones, phytohormone-like molecules, volatile organic compounds, secondary metabolites, or by altering the plant phytohormone homeostasis (Gravel et al., 2007; Vinale et al., 2008; Contreras-Cornejo et al., 2009; Viterbo and Horwitz, 2010; Salas-Marina et al., 2011; Olmedo-Monfil and Casas-Flores, 2014; Sáenz-Mata et al., 2014). Trichoderma spp. posses several mechanisms to modulate plant growth and development, which, in combination with the plant genotype, could result in different plant phenotypes, indicating that the Trichoderma genotype is also important to modulate the plant phenotype.

Overexpression of epl1 and sm1 in T. virens and T. atroviride

In this work, we generated KO and OE strains of the sm1 and epl1 genes. As expected, those T. atroviride and T. virens strains with additional copies of the genes showed enhanced levels of transcript as compared to their parental strains, excluding TvOE6.2 whose copy number was 7, whereas the sm1 transcript levels was 0.5-fold. Intriguingly, as the copy number of sm1 or epl1 increased in the genome, the abundance of the corresponding transcript decreased, with the exception of TaOE2.1, which contains five copies of epl1 and showed higher levels of transcript than TaOE3.1, which contains four copies. Similar results were reported for T. virens (Djonovic et al., 2007). In this sense, it has been demonstrated that extra copies of a gene in the genome of filamentous fungi, which induce an overexpression of such gene, could lead to gene silencing (Romano and Macino, 1992). On the other hand, chromatin organization in the integration site and/or chromosomal position can affect the expression of the inserted gene.

Sm1 and epl1 differentially modulate the induction of systemic disease resistance against different pathogens in tomato plants

Several reports have shown that colonization of plant roots leads to the induction of local and systemic disease resistance against a wide range of phytopathogens (Harman et al., 2004; Shoresh et al., 2010). Accumulating evidences indicate that disease resistance induced by Trichoderma spp. is through their MAMPs (Hermosa et al., 2012). Previously, it was reported that Sm1 from T. virens induces plant defense response and provides high levels of systemic resistance to cotton plants against the foliar pathogen Colletotrichum spp. (Djonovic et al., 2006). Inoculation of maize seedlings with sm1 OE and KO strains showed that Sm1 is required for induced resistance in this plant (Djonovic et al., 2007). Here we show that T. atroviride and T. virens induced systemic resistance in tomato against A. solani, and B. cinerea, and against the hemibiotrophic bacterial pathogen Pst DC3000. Both wild-type strains protected tomato seedlings against the three pathogens, whereas T. atroviride conferred better protection against A. solani, followed by Pst DC3000, and B. cinerea, respectively, whilst T. virens protected tomato seedlings better against B. cinerea, followed by Pst DC3000 and A. solani, respectively.

Our results confirm and extend the data of Djonovic et al. (2007), since sm1 and epl1 OE induced more efficiently systemic disease resistance against the three tested foliar pathogens, compared to the wild-type strain; whereas the TvKO2 treated seedlings, infected with Pst DC3000, were unable of conferring protection to tomato plants. Furthermore, our findings in tomato plants treated with KO strains and infected with B. cinerea and A. solani clearly indicated that besides Sm1 and Epl1 there are other MAMPs. The above suggests that the Trichoderma and the pathogen genotypes are also determinant in the three-way interaction, since almost all treatments of tomato plants with the KO strains conferred less protection than those treated with the WT and OE strains, but never reached the damage observed in the non-treated control. Our results also demonstrated that the Epl1 from T. atroviride is able to induce protection against the three tested pathogens. However, it seems that Ep1 plays a minor role as compared to Sm1 from T. virens. Interestingly, plants treated with TaKO9 and infected with Pst DC3000 showed higher levels of protection than the WT strain. In this regard, other Trichoderma MAMPs, including proteins with enzymatic activity (cellulase, xylanase, endopolygalacturonase, an expansin-like protein) and peptaibols, have been reported (Ron et al., 2000; Martinez et al., 2001; Viterbo et al., 2007; Brotman et al., 2008; Morán-Diez et al., 2009). Our results suggest that Epl1 and Sm1 are not the only molecules responsible for the induction of defense responses against these foliar pathogens in tomato, and that there is more than one pathway involved in the plant defense response during the Trichoderma-plant-pathogen interaction.

Sm1 and epl1 differentially modulate defense-related genes in tomato plants

An increase in endogenous SA and the synthesis of PR proteins is one of the most common responses triggered in plants following an infection with an inducing microorganism (Van Loon and Van Strien, 1999). The local and systemic disease resistance induced by T. harzianum is accompanied by an increase in the enzymatic activity of peroxidase and chitinase, which are involved in the JA/ET and SA response, respectively (Shoresh et al., 2005). In tomato, SlGLUA, which encodes for a 35 kDa acidic isoform class III β-1, 3-glucanase, is induced by B. cinerea (Benito et al., 1998) as well as by virulent and avirulent races of Cladosporium fulvum (van Kan et al., 1992), whereas SlPR-5, which encodes for an antifungal osmotin-like protein, is induced by Fusarium oxysporum (Rep et al., 2002) and T. hamatum 382 (Alfano et al., 2007). These genes are also responsive to the SAR-inducing chemicals SA and INA (2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid) in tomato (van Kan et al., 1995). Here, we show that T. atroviride and T. virens were able to successfully induce systemic disease resistance in tomato accompanied by increased expression levels of SA defense-related genes. The expression levels of SlGLUA and SlPR-5 were locally and systemically upregulated when inoculated with all tested strains, although they were induced to a lesser extent in leaves. These results suggest that the products of SlGLUA and SlPR-5 could be involved in the local and systemic disease resistance in tomato mediated by these fungi. Our data suggest also a minor role of Epl1 in the induction of SlGLUA, whereas it seems to play a major role on the local and systemic induction of SlPR-5. The results of SlPR-5 are in agreement with the data reported for the interaction of T. hamatum 382 with tomato, in which this microorganism used for biocontrol induced three- to five-fold SlPR-5 expression in leaves (Alfano et al., 2007). On the other hand, our results indicate that the Sm1 is one of several elicitors of SlGLUA and SlPR-5 since these genes did not show a sm1 dose-response behavior in their transcription levels in both, leaves and roots. Contrasting with our data, the inoculation of tomato plants with Trichoderma harzianum T-78, did not induce the expression of SA-related gene SlPR-1a (Martínez-Medina et al., 2013). We also tested the expression of SlHMGR gene that encodes for a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase gene, whose product is related to the synthesis of sesquiterpene phytoalexin, which was not induced by any of the tested strains. A similar result was found for the SA-related SlPAL gene in tomato inoculated with T-78, in spite of an intact pathway for induced resistance is required (Martínez-Medina et al., 2013). Probably, these differences and coincidences depend on both the Trichoderma strains, as well as the tomato cultivar.

An alternative pathway in the plant response to pathogen attack is mediated by JA/ET, which is characterized by the production of a cascade of oxidative enzymes (peroxidases, polyphenol oxidases, and lipoxygenases) and the accumulation of low-molecular weight compounds (phytoalexins) (Choudhary et al., 2007). It has been reported that lipoxygenase may generate signal molecules such as JA, methyl-JA, or lipid peroxides, which coordinately amplify specific responses. Furthermore, lipoxygenase activity may also cause irreversible membrane damage, which would lead to the leakage of cellular contents and ultimately result in plant cell death (Croft et al., 1993). Treatment of cotton cotyledons with purified Sm1 resulted in plant autofluorescence and increased levels of phytoalexins as consequence of phenolic compounds oxidation (Hanson and Howell, 2004; Djonovic et al., 2006). The SlCEVI16 gene encodes for a secreted peroxidase induced by virions and ethephon, where the latter triggers ethylene production in tomato (Gadea et al., 1996). The Slα–DOX1 gene encodes for an α-dioxygenase, which is involved in the generation of lipid derivates (oxylipins), and is induced by JA and oomycetes (Tirajoh et al., 2004). Our results indicate that Epl1 from T. atroviride is more effective locally on the induction of Slα–DOX1, but dispensable for its induction, whereas Sm1 from T. virens is essential to systemically induce Slα–DOX1, but not locally, which indicates that Sm1 could be involved in ISR. Like lipoxygenases, the α-DOX enzymes catalyze the oxygenation of fatty acids to produce oxylipins, including jasmonates, which contribute to basal resistance to bacteria and other pathogens (Hamberg et al., 2005). Interestingly, SA regulates Slα–DOX1 but not JA in Arabidopsis, and whose suppression results in increased bacterial growth (Ponce de Leon et al., 2002), as well as in a diminished SAR response in distal leaves (Vicente et al., 2012). In contrast, the induction of α–DOX1 in rice plants by Xanthomonas oryzae is mediated by JA (Koeduka et al., 2005). It is possible that the systemic induction of Slα–DOX1 by Sm1 is important to produce oxylipins to counteract B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 by means of SA and/or JA pathways. In this regard, the simultaneous induction of these signal transduction pathways by T. atroviride and its effectiveness to counteract these pathogens has been reported previously (Salas-Marina et al., 2011).

SlCEVI16 was induced locally by both sets of WT, OE, and KO strains, without a correlation regarding its Epl1 or Sm1 copy number, whereas in leaves of plants treated with T. atroviride strains, the induction of SlCEVI16 agreed with the sm1 copy number. This result indicates that the Epl1 could play a major role on the systemic induction, but not locally in SlCEVI16 induction during T. atroviride-tomato interaction, and this in turn could be important to counteract soil and airborne pathogens, including B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. On the contrary, plants treated with the different T. virens strains did not show a dose-response behavior in the transcription levels of SlCEVI16 in leaves, indicating a minor role of Sm1 on the induction of this gene which could be dispensable to attack A. solani and B. cinerea. It has been demonstrated that plant peroxidases are involved in the response to pathogens mediated by JA/ET, whose activity has been related to resistance responses, including lignifications and suberization, cross-linking of cell wall proteins, generation of reactive oxygen species, and phytoalexins synthesis, the latter show antifungal activity themselves (Bolwell and Wojtaszek, 1997; Quiroga et al., 2000; Caruso et al., 2001).

The SlCHI9 and SlTLRP genes showed local and systemic induction when inoculated with all the Trichoderma strains, but did not show a correlation with the sm1 or epl1 copy number. TaOE2.1 induced marginally higher levels of SlCHI9 and SlTLRP both, locally and systemically compared to the wild-type, whereas the overexpression of sm1 leads to a negative effect on the expression of such genes. These results indicate that Sm1 does not play an important role in the induction of these genes, whilst Epl1 seems to play a role on the induction of ISR-related genes. Intriguingly, in almost all cases TvKO9 induced high levels of SlCHI9 and SlTLRP locally and systemically, whereas SlCHI9 showed high transcript levels in leaves, but not the SlTLRP when inoculated with the TvKO2. In this regard, Djonovic et al. (2007) found that SA-related genes, PR-1 and PR-5, as well as AOS and OPR7, which are related to JA in maize, were downregulated by OE strains as compared to the wild-type after challenging maize plants with C. graminicola. Interestingly, in some cases the expression levels of such genes were lower than in plants treated with the KO strain.

Our results showed that the expression levels of GLUA were higher in roots than in leaves. However, the rest of the genes selected showed, in general, marginally higher level of expression in roots than in leaves. Similar results have been obtained in similar studies using other plant species inoculated with Trichoderma spp. (Yedidia et al., 2003; Shoresh et al., 2005, 2006; Salas-Marina et al., 2011). It has also been shown that Trichoderma treated plants, when inoculated with an airborne pathogen respond very strongly, displaying much higher levels of expression of defense related genes (Viterbo et al., 2007; Mathys et al., 2012; Perazzolli et al., 2012). We hypothesized, that upon inoculation of tomato plants treated with the different Trichoderma strains with an airborne pathogen, the induction of such genes would be higher than in seedlings inoculated only with Trichoderma, due to the priming effect of Trichoderma.

Based on the systemic protection experiments, our study provides genetic evidence that the elicitors of defense response, Epl1 and Sm1, are able to induce protection against hemibiotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens, which means that they are inducing ISR and SAR. The molecular analysis of SAR- and ISR-related genes led us to conclude that the Sm1 and Epl1 proteins play a minor role in the induction of basal levels of these genes, since both T. atroviride and T. virens KO strains were able to induce five of six genes in tomato, with the exception of SlCEVI16 by TaKO9 and Slα–DOX1 by TvKO2, whose transcript levels were similar to those detected in mock plants. Taking into account that SlCEVI16 and Slα–DOX1 genes are induced by the same signal transduction pathway, indicates that each, Sm1 and Epl1, has different specific targets in the same pathway to counteract pathogens with different life style. Therefore, our work indicates that the induction of ISR by T. virens and T. atroviride could be more important than the SAR signal to counteract pathogens as demonstrated by Martínez-Medina et al. (2013). More studies need to be undertaken to clarify this proposal.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants SEP-2010-103733 and FORDECYT-2012-02-193512 to SCF and Ramón G. Guevara González, respectively. MASM and PDS are indebted to CONACYT for doctoral fellowships. The authors wish to thank Dr. Rogerio R. Sotelo-Mundo and Dr. Braulio Gutierrez Medina for helpful revision and suggestions.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fpls.2015.00077/abstract

References

- Alfano G., Lewis Ivey M. L., Cakir C., Bos J. I. B., Miller S. A., Madden L. V., et al. (2007). Systemic modulation of gene expression in tomato by Trichoderma hamatum 382. Phytopathology 97, 429–437. 10.1094/PHYTO-97-4-0429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek J. M., Kenerley C. M. (1998). The arg-2 gene of Trichoderma virens: cloning and development of a homologous transformation system. Fungal Genet. Biol. 23, 34–44. 10.1006/fgbi.1997.1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey B. A., Taylor R., Dean J. F., Anderson J. D. (1991). Ethylene biosynthesis inducing endoxylanase is tranlocated through the xylem of Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi plants. Plant Physiol. 97, 1181–1186. 10.1104/pp.97.3.1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B., Zambryski P., Staskawicz B., Dinesh-Kumar S. P. (1997). Signaling in plant-microbe interactions. Science 276, 726–733. 10.1126/science.276.5313.726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R., Elad Y., Chet I. (1984). The controlled experiment in the scientific method with special emphasis on biological control. Phytopathology 74, 1019–1021. 10.1094/Phyto-74-101912519633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker P. A. H. M., Ran L. X., Pieterse C. M. J., Van Loon C. L. (2003). Understanding the involvement of rhizobacteria mediated induction of systemic resistance in biocontrol of plant diseases. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 25, 5–9 10.1080/07060660309507043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benito E. P., ten Have A., van't Klooster J. W., van Kan J. A. L. (1998). Fungal and plant gene expression during synchronized infection of tomato leaves by Botrytis cinerea. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 104, 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell G. P., Wojtaszek P. (1997). Mechanisms for the generation of reactive oxygen species in plant defence: a broad perspective. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 51, 347–366 10.1006/pmpp.1997.0129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman Y., Briff E., Viterbo A., Chet I. (2008). Role of swollenin, an expansin-like protein from Trichoderma, in plant root colonization. Plant Physiol. 147, 779–789. 10.1104/pp.108.116293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman Y., Kapuganti J. G., Viterbo A. (2010). Trichoderma. Curr. Biol. 20, R390–R391. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai F., Yu G., Wang P., Wei Z., Fu L., Shen Q., et al. (2013). Harzianolide, a novel plant growth regulator and systemic resistance elicitor from Trichoderma harzianum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 73, 106–113. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A. M., Sweigard J. A., Valent B. (1994). Improved vectors for selecting resistance to hygromycin. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 41, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso C., Chilosi G., Leonardi L., Bertini L., Magro P., Buonocore V., et al. (2001). A basic peroxidase from wheat kernel with antifungal activity. Phytochemistry 58, 743–750. 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00226-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Flores S., Rios-Momberg M., Rosales-Saavedra T., Martínez-Hernández P., Olmedo-Monfil V., Herrera-Estrella A. (2006). Cross talk between a fungal blue-light perception system and the cyclic AMP signaling pathway. Eukaryot. Cell. 5, 499–506. 10.1128/EC.5.3.499-506.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.-C., Chang Y.-C., Baker R., Kleifeld O., Chet I. (1986). Increased growth of plants in presence of the biological control agent Trichoderma harzianum. Plant Dis. 70, 145–148 10.1094/PD-70-145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm S., Coaker G., Day B., Staskawicz B. J. (2006). Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 124, 803–814. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary K. D., Prakash A., Johri B. N. (2007). Induced systemic resistance (ISR) in plants: mechanism of action. Indian J. Microbiol. 47, 289–297. 10.1007/s12088-007-0054-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Cornejo H. A., Macías-Rodríguez L., Beltrán-Peña E., Herrera-Estrella A., López-Bucio J. (2011). Trichoderma-induced plant immunity likely involves both hormonal- and camalexin-dependent mechanisms in Arabidopsis thaliana and confers resistance against necrotrophic fungi Botrytis cinerea. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1554–1563. 10.4161/psb.6.10.17443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Cornejo H. A., Macías-Rodríguez L., Cortés-Penagos C., López-Bucio J. (2009). Trichoderma virens, a plant benefical fungus, enhances biomass production and promotes lateral root growth through an auxin-dependent mechanism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 149, 2579–1592. 10.1104/pp.108.130369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft K. P. C., Jüttner F., Slusarenko J. A. (1993). Volatile products of the lipoxygenase pathway evolved from Phaseolus vulgaris (L.) leaves inoculated with Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. Plant Physiol. 101, 13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuppels D. A. (1986). Generation and characterization of Tn5 insertion mutations in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51, 323–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djonovic S., Pozo M. J., Dangott L. J., Howell C. R., Kenerley C. M. (2006). Sm1, a proteinaceous elicitor secreted by the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma virens induces plant defense responses and systemic resistance. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19, 838–853. 10.1094/MPMI-19-0838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djonovic S., Vargas A. W., Kolomiets V. M., Horndeski M., Wiest A., Kenerley C. M. (2007). A proteinaceous elicitor sm1 from the beneficial fungal Trichoderma virens is required for induced systemic resistance in maize. Plant Physiol. 145, 875–889. 10.1104/pp.107.103689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druzhinina I. S., Seidl-Seiboth V., Herrera-Estrella A., Horwitz B. A., Kenerley C. M., Monte E., et al. (2011). Trichoderma: the genomics of opportunistic success. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 749–759. 10.1038/nrmicro2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant W. E., Dong X. (2004). Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42, 185–209. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadea J., Mayda M. E., Conejero V., Vera P. (1996). Characterization of defense-related genes ectopically expressed in viroid-infected tomato plants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 9, 409–415. 10.1094/MPMI-9-0409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J. (2005). Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43, 205–227. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravel V., Antoun V., Tweddell R. J. (2007). Growth stimulation and fruit yield improvement of greenhouse tomato plants by inoculation with Pseudomonas putida or Trichoderma atroviride: possible role of indoleacetic acid (IAA). Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 1968–1977 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.02.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberg M., Ponce de Leon I., Rodriguez M. J., Castresana C. (2005). ?–dioxygenases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 169–174. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson L. E., Howell R. C. (2004). Elicitors of plant defense responses from biocontrol strains of Trichoderma virens. Phytopathology 94, 171–176. 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.2.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman G. E. (2000). Myths and dogmas of biocontrol. Changes in perceptions derived from research on Trichoderma harzianum T22. Plant Dis. 84, 377–393 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.4.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman G. E., Howell C. R., Viterbo A., Chet I., Lorito M. (2004). Trichoderma species - Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 43–56. 10.1038/nrmicro797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermosa R., Viterbo A., Chet I., Monte E. (2012). Plant-beneficial effects of Trichoderma and of its genes. Microbiology 158, 17–25. 10.1099/mic.0.052274-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar-Agarwal S., Jin H. (2010). The role of small RNAs in the host-microbe interactions. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 225–246. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King E. O., Ward M. K., Raney D. E. (1954). Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 44, 301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeduka T., Matsui K., Hasegawa M., Akakabe Y., Kajiwara T. (2005). Rice fatty acid alpha-dioxygenase is induced by pathogen attack and heavy metal stress: activation through jasmonate signaling. J. Plant Physiol. 162, 912–920. 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C., Blanc F., LeClaire E., Besnard O., Nicole M., Baccou C. J. (2001). Salicylic acid and ethylene pathways are differentially activated in melon cotyledons by active or heat-denatured cellulase from Trichoderma longibrachiatum. Plant Physiol. 127, 334–344. 10.1104/pp.127.1.334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Medina A., Fernández I., Sánchez-Guzmán M. J., Jung S. C., Pascual J. A., Pozo M. J. (2013). Deciphering the hormonal signalling network behind the systemic resistance induced by Trichoderma harzianum in tomato. Front Plant Sci. 4:206. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathys J., De Cremer K., Timmermans P., Van Kerckhove S., Lievens B., Vanhaecke M., et al. (2012). Genome-Wide Characterization of ISR Induced in Arabidopsis thaliana by Trichoderma hamatum T382 Against Botrytis cinerea Infection. Front Plant Sci. 3:108. 10.3389/fpls.2012.00108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morán-Diez E., Hermosa R., Ambrosino P., Cardoza E. R., Gutiérrez S., Lorito M., et al. (2009). The ThPG1 endopolygalacturonase is required for the Trichoderma harzianum–plant beneficial interaction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 1021–1031. 10.1094/MPMI-22-8-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mur J. L. A., Kenton P., Atzorn R., Miersch O., Wasternack C. (2006). The outcomes of concentration-specific interactions between salicylate and jasmonate signaling include synergy, antagonism, and oxidative stress leading to cell death. Plant Physiol. 140, 249–262. 10.1104/pp.105.072348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plantarum. 15, 473–497 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo-Monfil V., Casas-Flores S. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of biocontrol in Trichoderma spp. and their applications in agriculture, in Biotechnology and Biology of Trichoderma, eds Gupta V., Schmoll M., Herrera-Estrella A., Upadhyay R., Druzhinina I., Tuohy M. (Amsterdam: Elservier; ), 429–453. [Google Scholar]

- Perazzolli M., Moretto M., Fontana P., Ferrarini A., Velasco R., Moser C., et al. (2012). Downy mildew resistance induced by Trichoderma harzianum T39 in susceptible grapevines partially mimics transcriptional changes of resistant genotypes. BMC Genomics 13, 660–678. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce de Leon I., Sanz A., Hamberg M., Castresana C. (2002). Involvement of the Arabidopsis α-DOX1 fatty acid dioxygenease protein in protection against oxidative stress and cell death. Plant J. 29, 61–72. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo M. J., Van Loon L. C., Pieterse J. M. C. (2005). Jasmonates-signals in plant-microbe interactions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 23, 211–222 10.1007/s00344-004-0031-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga M., Guerrero C., Botella M. A., Barcelo A., Amaya I., Medina M. I., et al. (2000). A tomato peroxidase involved in the synthesis of lignin and suberin. Plant Physiol. 122, 1119–1127. 10.1104/pp.122.4.1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeder U., Broda P. (1989). Rapid preparation of DNA from filamentous fungi. Lett Appl. Microbiol. 1, 17–20 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1985.tb01479.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rep M., Dekker H. L., Vossen J. H., de Boer A. D., Houterman P. M., Speijer D., et al. (2002). Mass spectrometric identification of isoforms of PR proteins in xylem sap of fungus-infected tomato. Plant Physiol. 130, 904–917. 10.1104/pp.007427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano N., Macino G. (1992). Quelling: transient inactivation of gene expression in Neurospora crassa by transformation with homologous sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 6, 3343–3353. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron M., Kantety R., Martin G. B., Avidan N., Eshed Y., Zamir D., et al. (2000). High-resolution linkage analysis and physical characterization of the EIX-responding locus in tomato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 100, 184–189 10.1007/s001220050025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz-Mata J., Salazar-Badillo F. B., Jiménez-Bremont J. F. (2014). Transcriptional regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY genes under interaction with beneficial fungus Trichoderma atroviride. Acta Physiol. Plant. 36, 1085–1093 10.1007/s11738-013-1483-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Marina M. A., Silva-Flores M. A., Uresti-Rivera E. E., Castro-Longoria E., Herrera-Estrella A., Casas-Flores S. (2011). Colonization of Arabidopsis roots by Trichoderma atroviride promotes growth and enhances systemic disease resistance through jasmonic acid/ethylene and salicylic acid pathways. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 131, 15–26 10.1007/s10658-011-9782-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Russell W. D. (2001). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl V., Marchetti M., Schandl R., Allmaier G., Kubicek C. P. (2006). Epl1, the major secreted protein of Hypocrea atroviridis on glucose, is a member of a strongly conserved protein family comprising plant defense response elicitors. FEBS J. 273, 4346–4359. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M., Gal-On A., Leibman D., Chet I. (2006). Characterization of a mitogen-activated protein kinase gene from cucumber required for Trichoderma-conferred plant resistance. Plant Physiol. 142, 1169–1179. 10.1104/pp.106.082107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M., Harman G. E. (2008). The molecular basis of shoots responses of maize seedlings to Trichoderma harzianum T22 inoculation of the root: a proteomic approach. Plant Physiol. 147, 2147–2163. 10.1104/pp.108.123810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M., Harman G. E., Matsoury F. (2010). Induced systemic resistance and plant responses to fungal biocontrol agents. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 21–43. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M., Yedidia I., Chet I. (2005). Involvement of jasmonic acid/ethylene signaling pathway in the systemic resistance induced in cucumber by Trichoderma asperellum T203. Phytopathology 95, 76–84. 10.1094/PHYTO-95-0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirajoh A., Aung T. S. T., McKay A. B., Aine L. P. (2004). Stress-responsive a-dioxygenase expression in tomato roots. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 713–723. 10.1093/jxb/eri038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton J., Van Pelt J. A., Van Loon L. C., Pieterse C. M. J. (2002). Differential effectiveness of salicylate-dependent and jasmonate/ethylene-dependent induced resistance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 15, 27–34. 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.1.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci M., Ruocco M., De Masi L., De Palma M., Lorito M. (2010). The beneficial effect of Trichoderma spp. on tomato is modulated by the plant genotype. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 341–354. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00674.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kan J. A. L., Cozijnsen T., Danhash N., de Wit P. J. G. M. (1995). Induction of tomato stress protein mRNAs by ethephon, 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid and salicylate. Plant. Mol. Biol. 27, 1205–1213. 10.1007/BF00020894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kan J. A. L., Joosten M. H. A. J., Wagemakers C. A. M., van den Berg-Velthuis G. C. M., de Wit P. J. G. M. (1992). Differential accumulation of mRNAs encoding extracellular and intracellular PR proteins in tomato induced by virulent and avirulent races of Cladosporium fulvum. Plant. Mol. Biol. 20, 513–527. 10.1007/BF00040610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon L. C. (2007). Plant responses to plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 119, 243–254 10.1007/s10658-007-9165-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon L. C., Van Strien A. E. (1999). The families of pathogenesis-related proteins, their activities, and comparative analysis of PR-1 type proteins. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 55, 85–97 10.1006/pmpp.1999.0213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wees S. C., Van der Ent S., Pieterse C. M. (2008). Plant immune responses triggered by beneficial microbes. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 11, 443–448. 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas W. A., Djonović S., Sukno S. A., Kenerley C. M. (2008). Dimerization controls the activity of fungal elicitors that trigger systemic resistance in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19804–19815. 10.1074/jbc.M802724200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente J., Cascón T., Vicedo B., García-Agustín P., Hamberg M., Castresana C. (2012). Role of 9-lipoxygenase and α-dioxygenase oxylipin pathways as modulators of local and systemic defense. Mol. Plant. 5, 914–928. 10.1093/mp/ssr105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinale F., Sivasithamparam K., Ghisalberti E. L., Marra R., Barbetti M. J., Li H., et al. (2008). A novel role for The Trichoderma–plant interaction Trichoderma secondary metabolites in the interactions with plants. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 72, 80–86 10.1016/j.pmpp.2008.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viterbo A., Harel M., Horwitz B. A., Chet I., Mukherjee P. K. (2005). Trichoderma mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling is involved in induction of plant systemic resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 6241–6246. 10.1128/AEM.71.10.6241-6246.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viterbo A., Horwitz B. A. (2010). Mycoparasitism, in Cellular and Molecular Biology of Filamentous Fungi, Vol. 42, eds Borkovich K. A., Ebbole D. J. (Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; ), 676–693. [Google Scholar]

- Viterbo A., Wiest A., Brotman Y., Chet I., Kenerley C. (2007). The 18mer peptaibols from Trichoderma virens elicit plant defence responses. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 737–746. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T. J., Brunts T., Lee S., Taylor J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. 38, 315–322 10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yedidia I., Benhamou N., Chet I. (1999). Induction of defense responses in cucumber plants (Cucumis sativus L.) by the biocontrol agent Trichoderma harzianum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedidia I., Shoresh M., Kerem Z., Benhamou N., Kapulnik Y., Chet I. (2003). Concomitant induction of systemic resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. lachrymans in cucumber by Trichoderma asperellum (T-203) and the accumulation of phytoalexins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 7343–7353. 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7343-7353.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. H., Hamari Z., Han K. H., Seo J., Reyes D. Y., Scazzocchio C. (2004). Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41, 973–981. 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilinger S., Galhaup C., Payer K., Woo S. L., Mach R. L., Fekete C., et al. (1999). Chitinase gene expression during mycoparasitic interaction of Trichoderma harzianum with its host. Fungal Genet. Biol. 26, 131–140. 10.1006/fgbi.1998.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.