Abstract

To understand how the molecular chaperone Hsp90 participates in conformational maturation of the estrogen receptor (ER), we analyzed the interaction of immobilized purified avian Hsp90 with mammalian cytosolic ER. Hsp90 was either immunoadsorbed to BF4 antibody–Sepharose or GST-Hsp90 fusion protein (GST.90) was adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose. GST.90 was able to retain specifically ER, similarly to immunoadsorbed Hsp90. When cells were treated with estradiol and the hormone treatment was maintained during cell homogenization, binding, and washing steps, GST.90 still interacted efficiently with ER, suggesting that ER may form complexes with Hsp90 even after its activation by hormone and salt extraction from nuclei. The GST.90-ER interaction was consistently reduced in the presence of increasing concentrations of potassium chloride or when cytosolic ER-Hsp90 complexes were previously stabilized by molybdate, indicating that GST.90-ER complexes behave like cytosolic Hsp90-ER complexes. A purified thioredoxin-ER fusion protein was also able to form complexes with GST.90, suggesting that the presence of other chaperones is not required. ER was retained only by GST.90 deletion mutants bearing an intact Hsp90 N-terminal region (1–224), the interaction being more efficient when the charged region A was present in the mutant (1–334). The N-terminal fragment 1–334, devoid of the dimeric GST moiety, was also able to interact with ER, pointing to the monomeric N-terminal adenosine triphosphate binding region of Hsp90 (1–224) as the region necessary and sufficient for interaction. These results contribute to understand the Hsp90-dependent process responsible for conformational competence of ER.

INTRODUCTION

The estrogen signal is mediated by the estrogen receptor (ER), which is a ligand-inducible transcription factor of the nuclear receptor superfamily. In the absence of estradiol, ER predominantly localized in the nucleus (King and Greene 1984) is found in the cytosolic fraction of cell homogenate as part of a 9S, highly dynamic, multiprotein complex consisting of a dimer of the Hsp90 chaperone, the p23 cochaperone, and one of several large immunophilins, such as Cyp40 or FKBP52 (Joab et al 1984; Pratt and Toft 1997; Smith et al 2000). It is known that molybdate stabilizes the interaction between Hsp90 and steroid receptors, leading to a 9S receptor form that is not able to bind to DNA. It is also known that the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), when dissociated from Hsp90, differently from other receptors, rapidly lose the capacity to bind hormone (Bresnick et al 1988; Rafestin-Oblin et al 1992). These results have suggested a dual role for Hsp90, a negative one in maintaining the receptor in a repressed form and a positive one in facilitating the hormone binding. Indeed Hsp90 is essential for effective ligand-dependent gene expression by all steroid receptors, even though ER displays some activity at low Hsp90 level (Picard et al 1990).

The chaperone function of Hsp90 toward nonspecific and specific targets has been recently established as dependent on its adenosine triphosphatase activity (Obermann et al 1998; Panaretou et al 1998; Scheibel et al 1998; Grenert et al 1999). The participation of Hsp90 in steroid-induced signal transduction has been also investigated using geldanamycin, a compound that specifically interacts with the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site of Hsp90 and interferes with its functions (Prodromou et al 1997a; Stebbins et al 1997). Geldanamycin drastically inhibited the induction of glucocorticoid-specific gene and severely compromised the hormone binding by 4 steroid receptors, including ER (Segnitz and Gehring 1997). Even though in vitro ER has been reported as less dependent on Hsp90 than GR or MR (Pratt and Toft 1997), a genetic approach has recently strongly suggested that ER requires Hsp90 both for efficient hormone binding and transcriptional activity (Fliss et al 2000).

In vitro studies have shown that an ER 9S complex, displaying the same properties as the native cytosolic one, can be reconstituted with purified Hsp90 and ER and is able to modulate the binding of ER to its responsive element (ERE) (Inano et al 1990, 1992; Sabbah et al 1996). Although the ligand binding domain (LBD) of most steroid receptors is sufficient for Hsp90 binding (Pratt and Toft 1997), ER requires additional amino acids (251–271) near the DNA binding domain, including a nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Chambraud et al 1990; Ylikomi et al 1992).

Studies with Hsp90 deletion mutants showed that a large C-terminal region (380–728) is sufficient for reconstitution of a complex with the progesterone receptor (PR) (Sullivan and Toft 1993). Moreover, 2 internal deletion mutants, ΔB (charged region) and ΔZ (leucine zipper), still interacted with GR, ER, or MR, whereas the deletion of the charged A region (221–290) precluded complex formation, indicating that this region stabilizes the 9S receptor form (Cadepond et al 1993; Binart et al 1995). Nevertheless, in a nuclear cotranslocation assay, ΔA Hsp90 interacted in vivo with ER (Meng et al 1996). Thus, a clear picture of the regions of Hsp90 required for the association with steroid receptors is still lacking.

To characterize Hsp90 domains sufficient to bind ER as a first step to understand how Hsp90 participates in conformational competence of the receptor, we have analyzed the interaction of ER with wild-type or truncated Hsp90 immobilized on resins via antibodies or N-terminal fusion with GST and investigated the effect of salts, molybdate, estradiol, and ATP. We have found that the monomeric N-terminal ATP binding region of Hsp90 was sufficient and necessary for complex formation with ER bound or not bound to estradiol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ER containing cellular extracts

ERC3 cells were grown at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide (Kushner et al 1990) in phenol red–free Dulbecco modified Eagel medium containing 10% steroid-free fetal calf serum and were treated or not with 10−7 M estradiol for 1 hour. The cells were collected in phosphate-buffered saline, centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 minutes, and then homogenized with a Teflon-glass potter in cytosol buffer (1.5 vol), pH 7.4 (20 mM Tris, 15% glycerol, 1 mM ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid tris glycerol EDTA (TGE), 1 mM dithioerythritol, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and antiproteases cocktail). Cells treated with estradiol were homogenized in the same buffer containing 0.4 M potassium chloride (KCl) and saturating amount of estradiol to obtain whole cell extracts. Homogenates in low- or high-salt buffer were centrifuged for 45 minutes at 105 000 × g, and the supernatant was used for binding experiments. All operations were performed at 4°C.

Plasmid constructs

pGEX vectors were from Amersham Pharmacia; pSVK3 chicken Hsp90α constructs (Meng et al 1996) and the bacterial expression plasmid pGEX90 (GST.90) have been previously described (Kang et al 1999). pGEX N1C1 was obtained by substituting the KpnI-SalI Hsp90 complementary DNA (cDNA) fragment of pGEX90 with the KpnI-SalI cDNA fragment of pSVK3N1C1. pGEX N1C2 was obtained by EcoRI digestion of pGEX90 to eliminate the C-terminal fragment of the Hsp90 cDNA and religation of the vector bearing the N-terminal Hsp90 cDNA region. pGEX N1C3 was constructed by substituting the KpnI-SalI coding fragment of pGEX90 with the KpnI-XhoI cDNA fragment from pSVK3NC4. pGEX N2C was constructed by inserting the cDNA fragment SmaI-XhoI of pSVK3N2C at the same sites of pGEX4T1 vector. pGEX N4C was obtained by insertion of the EcoRI-XhoI cDNA fragment of pSVK3N4C5 at the same sites of pGEX4T1 vector. The control plasmid was pGEX2T (GST alone). The predicted cDNA sequences encoding GST fusion proteins were confirmed by automated sequencing. The constructs were transformed into Epicurian Coli Bl21-Gold (DE3) pLys S Competent cells (Stratagene).

GST.90 and GST.90 mutants bacterial expression

Bacterial cells bearing the pGEX constructs were grown overnight in 500 mL of Luria broth (LB) medium at 37°C. The expression of fusion proteins was induced with 1 mM isoprophylthio-β-D-galactoside (IPTG) for 3 hours. Subsequently, cells were lysed by sonication in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris hydrochloride pH 8, 100 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid, 0.5% NP40); the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 10 minutes and stored at −20°C. Coomassie blue staining of an aliquot of each lysate, separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), was used to determine the relative level of expression of each fusion protein.

BF4-Hsp90 resin

The purified immunoglobulin G fraction from BF4 ascites fluid (Joab et al 1984), an antibody that recognizes specifically avian Hsp90α (Meng, unpublished results), was coupled to divinylsulfone-activated Sepharose 4B as described (Chadli et al 1999). Chicken Hsp90α was obtained by 1-step immunoaffinity purification on BF4 resin (Radanyi et al 1989). This procedure, using as starting material a chicken embryo cytosol, gave a homogenous Hsp90 preparation (purity >95%) on the basis of SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue or silver staining followed by gel scanning densitometry (Chadli et al 1999). A total of 100 μL of BF4 resin after immunoadsorption of purified Hsp90 was used for binding experiments.

Purified ER

A thioredoxin (TRX)–ER (D-E regions of ER, residues 302–552) fusion protein of 48 kDa, a gift from Marc Ruff, was produced with the pET Thiofusion System 32 (Novagen) and purified from Escherichia coli in the absence or presence of estradiol (Gangloff et al 2001). Liganded and unliganded ER was in Tris maleate (pH 8) buffer, 50 mM sodium chloride, and 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, with or without 35 μM estradiol. The antibody used for TRX-ER detection was a rabbit antihistidine tag.

GST.90-ER complex and salt treatment

After centrifugation, bacterial lysate containing GST or GST.90 was adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia) preequilibrated with lysis buffer. After washing, 200 μL of Sepharose beads containing almost equal molar amounts of GST or GST.90 were incubated with cytosolic or whole cell extracts of ERC3 (600 μg of protein at 2–3 mg/mL) in the absence or presence of KCl (150 and 400 mM) for 1 hour at 4°C. After this, the complexes were stabilized with 50 mM sodium molybdate. Sepharose gel was washed 3 times with 5 volumes of the same buffer containing sodium molybdate.

Gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis

Proteins interacting with GST, GST.90, or GST.90 mutants fixed on glutathione-Sepharose were solubilized in SDS Laemmli buffer by heating at 100°C for 5 minutes. The amounts of solubilized interacting proteins and of total input indicated in the legend of Figures were analyzed on a 10% denaturing gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. That comparable quantities of GST, GST90, and GST.90 mutants were adsorbed to gluthatione-Sepharose was verified by staining with Ponceau red. Membranes were saturated 1 hour in 10% nonfat milk in phosphate-buffered saline and 0.05% Tween 20, incubated with the specific antibodies, washed, and revealed using the ECL system. The signal corresponding to ER was analyzed using BioImage Software Station (Millipore). The range of arbitrary integrated optical densities between 0.01 and 10 was linear when using increasing amounts of loaded proteins.

Thrombin cleavage

To remove GST, 10 μg of GST.90 and GST.N1C2 were cleaved with 0.5 U thrombin overnight at 4°C in 300 μL of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) buffer. Hsp90 and N1C2 fragments, after retention of GST on affinity resin, were then fixed to BF4 resin and incubated with ER containing cellular extracts.

Antibodies

Antibodies used were C.311 (Santa Cruz), directed against residues 495–595 of ER C-terminal region and BF4, which recognizes an epitope in the charged A region of avian Hsp90α (Meng et al 1996).

RESULTS

Interaction of ER with immobilized Hsp90

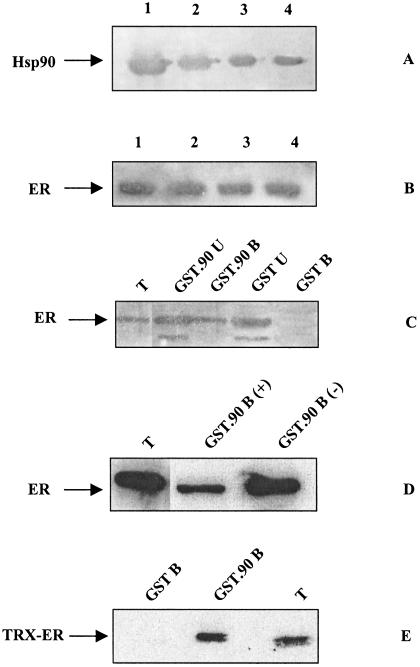

Previous reports have demonstrated that Hsp90-ER complexes can be reconstituted in solution from crude or purified components, leading to the detection of a 9S heterocomplex composed at least of Hsp90 and ER moieties (Inano et al 1990, 1992; Sabbah et al 1996). To map the minimal region of Hsp90 able to interact with ER, the reconstitution of the complex was first assessed using purified avian Hsp90 immunoimmobilized on BF4 antibody-Sepharose or GST fusion protein (GST.90) adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose beads. Hsp90 immunoadsorbed to BF4 resin was incubated with an ER-containing cytosolic extract from ERC3 cells, a CHO-derived cell line that expresses high levels of ER (Kushner et al 1990). Hsp90 and associated proteins were eluted from the resin with a pH 10.5 buffer; then Hsp90 and ER were detected with specific antibodies. As shown in Figure 1 A,B, both proteins were detected in the first 4 eluted fractions, indicating that immunoimmobilized Hsp90 interacts with ER, retaining roughly more than 30% of cytosolic ER (not shown). Moreover, since the BF4 antibody is specific for avian Hsp90α, retention of ER by the resin was not dependent on the adsorption of ERC3 cytosolic mammalian Hsp90 by the immobilized antibody. Neither signal was present when the ERC3 cytosol was incubated with the BF4 resin alone (not shown). Next, the interaction between cytosolic ER and Hsp90 was investigated using GST.90 fusion protein or GST alone immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose. GST beads did not retain ER (Fig 1C, lane GST B), thus excluding nonspecific interactions between ER and Sepharose 4B or GST. In contrast, about 30–40% of the cytosolic ER input (lane T) was bound to GST.90 beads (lane GST.90 B).

Fig. 1.

Interaction between Hsp90 and cytosolic ER. (A, B) Immunoadsorbed Hsp90 and cytosolic ER. Purified Hsp90 was immobilized on a specific BF4 immunoadsorbent resin to which the ER-containing cytosolic extract was applied. After washing, the elution of bound proteins was performed at pH 10.5 followed by neutralization. The eluted fractions (lanes 1–4) were tested by Western blot for the presence of Hsp90 (A) and ER (B) using BF4 and C.311 antibodies. (C) GST.90 and cytosolic ER. GST.90 and GST beads were incubated with cytosolic ER. After washing, bound proteins were recovered by boiling in Leammli sample buffer. The indicated aliquots of each sample were analyzed by Western blot using C.311 antibody. Lane T: one-tenth of total input; lane GST.90 U: one-fifth of GST.90 unbound ER; lane GST.90 B: one-third of GST.90 bound ER; lane GST U: one-fifth of GST unbound ER; lane GST B: one-third of GST bound ER. (D) Effect of molybdate on GST.90-ER interaction. Cytosolic ER supplemented or not with 50 mM molybdate was incubated with GST.90 beads. Total and bound samples were analyzed by Western blot. Lane T: one-tenth of total input; lane GST.90 B (+): one-third of GST.90 bound ER (+mo); lane GST.90 B (−): one-third of GST.90-bound ER (−mo). (E) GST.90 and purified TRX-ER. TRX-ER was produced and purified from E coli in presence of estradiol. One-third of TRX-ER bound to GST (lane GST B) or GST.90 beads (lane GST.90 B) and one-tenth (6 μg of TRX-ER) of total input (lane T) were analyzed by Western blot using an antihistidine tag antibody

It is known that steroid receptor–Hsp90 interaction is stabilized against dissociation by the presence of oxyanions such as molybdate and vanadate (Pratt and Toft 1997). Therefore, in the experiments reported herein, the molybdate was introduced at the end of the interaction between GST.90 and ER preparations to stabilize the formed complex. Moreover, we tested whether GST.90-ER complex formation is decreased by the prior stabilization of the Hsp90-ER complex in ERC3 cytosol by molybdate. It was found that the binding of ER to GST.90 was consistently reduced by more than 50% by the presence of molybdate in ERC3 cytosol (Fig 1D, compare GST.90 B [+] and GST.90 B [−]).

It is known that besides Hsp90 other chaperones and auxiliary proteins are required for conformational competence of steroid receptors; however, it is not clear whether the physical Hsp90-ER interaction depends on the presence of all those proteins. This issue was investigated by incubating GST.90 beads with highly purified histidine-tagged TRX-ER (ER LBD containing D and E regions) fusion protein prepared in the continuous presence of estradiol. Figure 1E shows that more than 30% of the purified TRX-ER (lane T) was bound to GST.90 (lane GST.90 B) and not to GST (lane GST B). Therefore, the presence of other chaperones was not required for interaction. Since incubation of purified TRX-ER with GST.90 beads and the subsequent washing steps were not supplemented with estradiol, it can be concluded that prior hormone binding does not preclude ER from interacting with Hsp90. The same pattern of interaction was obtained with TRX-ER purified in the absence of ligand, although with lower efficiency (less than 30% of ER binding, data not shown).

The GST.90-ER interaction is estradiol independent and inhibited by high salt concentrations

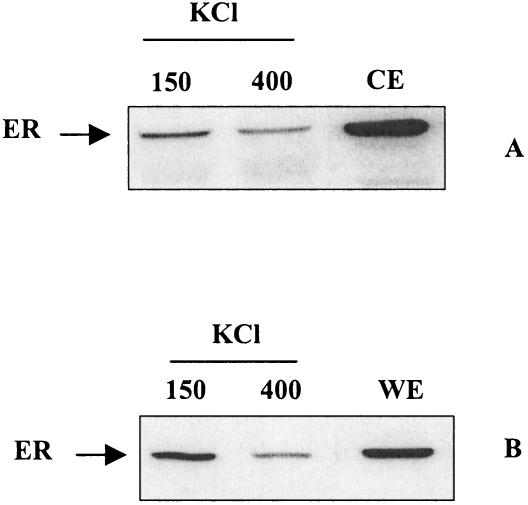

When ER is activated in vivo by estradiol, it binds tightly to chromatin structures from which it can be, to a large part, solubilized by high-salt treatment. To investigate to what extent GST.90-ER interaction was dependent on the presence of a high salt concentration, GST.90 beads were incubated with a low-salt cytosolic ER extract supplemented with KCl (150 or 400 mM). The usual 30–40% of ER binding to GST.90 in the absence of KCl was reduced to 15% with 150 mM KCl and further decreased with 400 mM KCl (Fig 2A) in agreement with the known dissociation of 9S complexes by salts.

Fig. 2.

Effects of KCl and estradiol on GST.90-ER interaction. (A) ER-containing cytosolic extract (CE) was supplemented with KCl to obtain the indicated concentrations and incubated with GST.90 beads. (B) Estradiol-treated, ER-containing whole cell extract (WE) (400 mM KCl) was diluted with or without KCl to obtain the indicated concentrations and incubated with GST.90 beads. One-twelfth of CE, one-tenth of WE, and one-tenth of ER bound to GST.90 were detected by Western blot

We then examined the ability of liganded ER to interact with GST.90. The high-salt ERC3 whole cell extract recovered from estradiol-treated cells was diluted to obtain 150 mM KCl or to maintain 400 mM KCl (Fig 2B). It was further incubated with and washed from GST.90 beads in the continuous presence of a saturating amount of hormone. The ER signal per milligram of protein recovered from whole cell extract was always lower than ER signal from low-salt cytosol (compare CE and WE, Fig 2A). However, the GST.90 bound fraction, which again decreased with increasing KCl concentrations, was higher compared with that of cytosolic extract. These results suggest that in vitro the continuous presence of estradiol does not abolish GST.90-ER interaction.

Delimitation of Hsp90 domains able to interact with ER

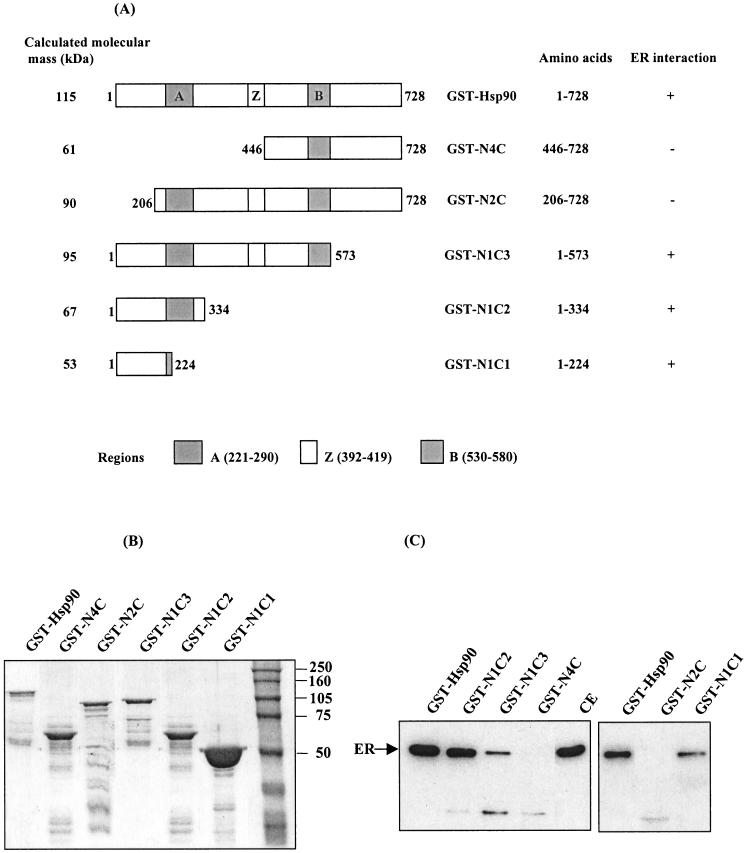

To test which domains of Hsp90 are responsible for interaction with ER, N- and C-terminal Hsp90 truncation mutants were generated and expressed in frame with GST. The GST.90 wild type and mutants are schematically represented in Figure 3A; the migration of the corresponding fusion proteins in denaturing gel is shown in Figure 3B. GST.90 wild type and mutants adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose beads were incubated with ER-containing cytosolic extracts, and interaction with ER was assessed as in Figure 1. Figure 3C shows that GST.N1C2 (1–334) interacted with ER to an extent comparable to GST.90 (1–728), whereas GST.N1C1 (1–224) and GST.N1C3 (1–573) were less efficient in ER binding. GST.N4C (446–728) and GST.N2C (206–728) did not interact with cytosolic ER. However, these 2 mutants seem to retain a degradation fragment of ER of approximately 30 kDa, indicating that, during the binding step, ER is less protected against proteolysis and an ER binding site may exist in the C-terminal region of Hsp90. These results indicate that full-length ER may only interact with Hsp90 wild type or mutants bearing an intact N-terminal region, and the interaction is more efficient when the charged A region is present in the mutant.

Fig. 3.

Interaction of GST.90 wild type and mutants with cytosolic ER. (A) Schematic representation of Hsp90 wild type, N-terminal or C-terminal deletion mutants, fused to GST. The calculated molecular mass (kDa) of fusion proteins, the Hsp90 amino acid sequence fused to GST, and the interaction with ER are indicated. The charged A and B regions and the leucin-zipper (LZ) region are also represented. (B) Analysis of GST.90 wild type and mutants. GST.90 and mutants were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining after binding to glutathione-Sepharose beads. (C) Cytosolic ER was incubated with GST.90 wild type and mutants adsorbed on glutathione-Sepharose beads. One-tenth of ER from total input (T) or bound to beads (one-third) was analyzed by Western blot. The ER degradation fragment had a molecular mass of approximately 30 kDa

It is worth noting that the Hsp90 N-terminal region (1–224) necessary and sufficient for interaction with ER bears the ATP-geldanamycin binding site. The presence of ATP (15 mM) during the incubation and washing steps did not change the interaction with the ER (data not shown).

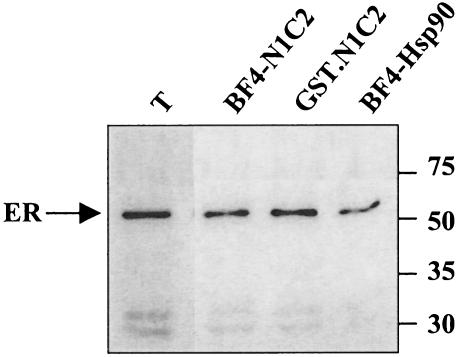

N-terminal Hsp90 dimerization is not required for interaction with ER

It is known that dimeric GST imposes a dimeric structure on a monomeric fused protein moiety (Nemoto et al 1995; Zabel et al 1999). In solution, the Hsp90 1–224 fragment behaves as a monomer even though the same region crystallizes either as a monomer or as a dimer (Prodromou et al 1997b). The Hsp90 dimer is held by contacts near the C-termini, leaving the N-terminal regions at some distance (Maruya et al 1999). However, elevated temperature or ATP has been described as inducing structural changes in the Hsp90 dimer so that the N-terminal regions of Hsp90 are repositioned to be in close proximity (Maruya et al 1999). Thus, to determine whether the interaction of GST.N1C2 (1–334) with ER was dependent on the dimeric structure of the fusion protein, the monomeric N-terminal fragment (N1C2) recovered after thrombin cleavage of the GST moiety, retained on glutathione-Sepharose, was immunoadsorbed to the BF4 resin and tested for its ability to interact with cytosolic ER. Results shown in Figure 4 indicate that the GST-dependent dimerization of the N-terminal portion of Hsp90 is not required for interaction with ER.

Fig. 4.

GST moiety does not contribute to N1C2-ER interaction. Fusion proteins GST.90 and GST.N1C2 were produced in E coli purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads and cleaved with thrombin. Hsp90 wild type and N1C2 fragments immunoadsorbed to BF4 resin were incubated with cytosolic ER. ER from cytosol or bound to resins was revealed by Western blot. Lane T: total input (ER from cytosolic extract); lane BF4-N1C2: ER bound to BF4-N1C2; lane GST.N1C2: ER bound to GST.N1C2; lane BF4-Hsp90: ER bound to BF4-Hsp90

DISCUSSION

ER, unlike other steroid receptors, retains its estradiol binding properties once dissociated from Hsp90; however, its in vivo dependence on the Hsp90 chaperone machinery has been unequivocally established (Fliss et al 2000). Although the minimal region of ER needed for complex formation with Hsp90 has been described (Chambraud et al 1990), it was not known whether isolated domains of Hsp90 directly interact with ER.

We investigated the molecular details of Hsp90-ER complex reconstitution using purified chicken Hsp90 or GST.90 fixed to Sepharose resins and found that both Hsp90 forms were able to bind efficiently ER, despite the presence of cytosolic mammalian Hsp90. Moreover, the interaction between GST.90 and ER was decreased by high salt concentrations, indicating that salts, beside favoring dissociation of cytosolic Hsp90-ER complexes, inhibit GST.90-ER complex formation. As expected, the presence of molybdate in ER-containing cytosol, by shifting the equilibrium between Hsp90-ER complex and free components toward complex stabilization, decreased ER-GST.90 interaction. Thus, GST.90-ER complexes display salt and molybdate-dependent properties similar to native 9S complexes.

Reconstitution experiments performed with highly purified TRX-ER fusion protein, in the presence or absence of estradiol, first demonstrated that the GST.90-ER interaction does not require the presence of other chaperones from vertebrates. Second, they indicated that, after transient hormone binding, ER still possesses or reacquires the ability to interact with Hsp90. Finally, since the TRX-ER construct does not include the NLS sequence needed for Hsp90-ER complex formation, its interaction with GST.90 suggests that the N-terminal TRX extension may substitute for the NLS sequence, as also reported for an extension constituted of β-galactosidase (Scherrer et al 1993). Alternatively, GST.90 fixed to resin may favor an interaction that was not detectable in cytosolic extracts containing ER LBD (Chambraud et al 1990).

It is generally thought that hormone induces dissociation of Hsp90 from steroid receptors. Indeed, estradiol disrupted the Hsp90-ER interaction detected in the absence of hormone by a partial nuclear cotranslocation of cytoplasmic Hsp90 (Devin-Leclerc et al 1998). However, in the experiments reported herein, the continuous presence of estradiol did not affect the GST.90-ER interaction, indicating that estradiol is not switching ER to a conformation unable to bind Hsp90. In agreement with this result, hormone-induced conformational changes of GR and MR have been observed within the 9S complexes (Couette et al 1996; Roux et al 1999). It is possible that, besides the hormone, a temperature of 37°C and/or the ER binding to ERE and coactivators are needed in vitro to observe a significant decrease of GST.90-ER interaction. ERE and ER coactivators may inhibit Hsp90 binding to ER, not necessarily by competing for the same sites but possibly by steric hindrance. We suggest, therefore, that in vivo, during and after estradiol stimulation, ER may transiently interact with Hsp90 for recycling, pointing to an Hsp90 function in steroid signaling not only before but also after receptor activation (Kang et al 1999). This suggestion is consistent with recent studies demonstrating Hsp90-dependent nuclear recycling of GR (Liu and DeFranco 1999). Thus, steroid receptor–chaperone complexes do not seem to be restricted solely to the cytoplasm. A small but significant fraction (3%) of the abundant cytoplasmic Hsp90 is found within nuclei, where it might continuously assemble receptors for recycling into competent heteromeric complexes (Csermely et al 1998).

The results obtained with GST.90 deletion mutants demonstrate that the N-terminal region 1–224 is necessary and sufficient for interaction with ER, although the interaction was less important than with wild-type GST.90. The same region was sufficient for GR binding (not shown). Comparatively, GST.N1C2 (1–334) interacts with ER as well as GST.90, possibly because it bears the charged A region. Several studies have suggested that this region has a regulatory function in the protein binding activity of Hsp90, since its presence improves the chaperone activity of the N-terminal domain (Scheibel et al 1999). Moreover, the same charged region, which is dispensable for viability in yeast when limited to residues 211–259 (Louvion et al 1996) or for ATP-dependent p23 binding (Chadli et al 2000), is required for luciferase refolding (Johnson et al 2000). With respect to ER, the deletion of the Hsp90 A region precluded detection of cytosolic 9S complexes (Binart et al 1995), but allowed complex formation when the Hsp90-ER interaction was tested by a nuclear cotranslocation assay (Meng et al 1996). In conclusion, this region may contribute to stabilizing the interaction between ER and the Hsp90 1–224 fragment. GST.90 constructs lacking the N-terminal region were not able to retain wild-type ER; however, a C-terminal degradation product of approximately 30 kDa was bound to some extent. The same fragment was also present in the fraction bound to GST.N1C3, indicating that some constructs during interaction may favor ER proteolysis even in the presence of appropriate inhibitors. Since this C-terminal degradation product of ER was in part retained by large C-terminal Hsp90 regions, the possibility cannot be excluded that this region possesses a second site for interaction with ER. In fact, immunoadsorbed PR was able to interact with a large C-terminal fragment of Hsp90 (Sullivan and Toft 1993). It has been recently reported that the target of molybdate is the C-terminal Hsp90 region that, in the presence of transition metal oxyanions, is protected against proteolysis (Hartson et al 1999; Soti et al 1998). This C-terminal change of conformation may directly participate in or indirectly stabilize the Hsp90-ER interaction.

The N-terminal monomeric ATP binding region of Hsp90 devoid of the GST moiety was sufficient for binding full-length ER. This finding differs from the recently reported requirement of transient dimerization or vicinity of the N-terminal Hsp90 regions in the dimer for adenosine triphosphatase activity or ATP-dependent p23 binding (Chadli et al 2000; Prodromou et al 2000), suggesting that the chaperone undergoes different conformational transitions during its multistep cycle.

In conclusion, we have established that the mere Hsp90-ER binding step does not necessitate other chaperone and auxiliary proteins nor is it hindered by hormone binding to the receptor. Finally, it does not require vicinity or interaction between N-terminal regions of Hsp90 dimer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marc Ruff (Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Strasbourg) for kindly providing purified TRX-ER and Virginie Aiello and Jocelyne Leclerc-Devin for assistance with some constructs. Ilham Bouhouche-Chatelier was a fellow of Société de Secours des Amis des Sciences, Institut Electricité Santé, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale. This work was supported by the CNRS and grants from the Association pour la Recherche Contre le Cancer and La Ligue Contre le Cancer (Indre and Paris Sections) to M.G.C.

REFERENCES

- Binart N, Lombes M, Baulieu EE. Distinct functions of the 90 kDa heat-shock protein (hsp90) in oestrogen and mineralocorticosteroid receptor activity: effects of hsp90 deletion mutants. Biochem J. 1995;311:797–804. doi: 10.1042/bj3110797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnick EH, Sanchez ER, Pratt WB. Relationship between glucocorticoid receptor steroid-binding capacity and association of the Mr 90,000 heat shock protein with the unliganded receptor. J Steroid Biochem. 1988;30:267–269. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(88)90104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadepond F, Binart N, Chambraud B, Jibard N, Schweizer-Groyer G, Segard-Maurel I, Baulieu EE. Interaction of glucocorticosteroid receptor and wild-type or mutated 90-kDa heat shock protein coexpressed in baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10434–10438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadli A, Bouhouche I, Sullivan W, Stensgard B, McMahon N, Catelli MG, Toft DO. Dimerization and N-terminal domain proximity underlie the function of the molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12524–12529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220430297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadli A, Ladjimi MM, Baulieu EE, Catelli MG. Heat-induced oligomerization of the molecular chaperone Hsp90: inhibition by ATP and geldanamycin and activation by transition metal oxyanions. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4133–4139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambraud B, Berry M, Redeuilh G, Chambon P, Baulieu EE. Several regions of human estrogen receptor are involved in the formation of receptor-heat shock protein 90 complexes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20686–20691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couette B, Fagart J, Jalaguier S, Lombes M, Souque A, Rafestin-Oblin ME. Ligand-induced conformational change in the human mineralocorticoid receptor occurs within its hetero-oligomeric structure. Biochem J. 1996;315:421–427. doi: 10.1042/bj3150421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P, Schnaider T, Soti C, Prohaszka Z, Nardai G. The 90-kDa molecular chaperone family: structure, function, and clinical applications: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79:129–168. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devin-Leclerc J, Meng X, Delahaye F, Leclerc P, Baulieu EE, Catelli MG. Interaction and dissociation by ligands of estrogen receptor and Hsp90: the antiestrogen RU 58668 induces a protein synthesis-dependent clustering of the receptor in the cytoplasm. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:842–854. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.6.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliss AE, Benzeno S, Rao J, Caplan AJ. Control of estrogen receptor ligand binding by Hsp90. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;72:223–230. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangloff M, Ruff M, Eiler S, Duclaud S, Wurtz JM, and Moras D 2001 Crystal structure of a mutant hER alpha LBD reveals key structural features for the mechanism of partial agonism. J Biol Chem 276: 15059–15065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenert JP, Johnson BD, Toft DO. The importance of ATP binding and hydrolysis by hsp90 in formation and function of protein heterocomplexes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17525–17533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartson SD, Thulasiraman V, Huang W, Whitesell L, Matts RL. Molybdate inhibits hsp90, induces structural changes in its C-terminal domain, and alters its interactions with substrates. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3837–3849. doi: 10.1021/bi983027s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inano K, Haino M, Iwasaki M, Ono N, Horigome T, Sugano H. Reconstitution of the 9 S estrogen receptor with heat shock protein 90. FEBS Lett. 1990;267:157–159. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inano K, Ishida T, Omata S, Horigome T. In vitro formation of estrogen receptor-heat shock protein 90 complexes. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1992;112:535–540. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joab I, Radanyi C, Renoir M, Buchou T, Catelli MG, Binart N, Mester J, Baulieu EE. Common non-hormone binding component in non-transformed chick oviduct receptors of four steroid hormones. Nature. 1984;308:850–853. doi: 10.1038/308850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Chadli A, Felts SJ, Bouhouche I, Catelli MG, Toft DO. Hsp90 chaperone activity requires the full-length protein and interaction among its multiple domains. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32499–32507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang KI, Meng X, Devin-Leclerc J, Bouhouche I, Chadli A, Cadepond F, Baulieu EE, Catelli MG. The molecular chaperone Hsp90 can negatively regulate the activity of a glucocorticosteroid-dependent promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1439–1444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WJ, Greene GL. Monoclonal antibodies localize oestrogen receptor in the nuclei of target cells. Nature. 1984;307:745–747. doi: 10.1038/307745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner PJ, Hort E, Shine J, Baxter JD, Greene GL. Construction of cell lines that express high levels of the human estrogen receptor and are killed by estrogens. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1465–1473. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-10-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, DeFranco DB. Chromatin recycling of glucocorticoid receptors: implications for multiple roles of heat shock protein 90. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:355–365. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.3.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvion JF, Warth R, Picard D. Two eukaryote-specific regions of Hsp82 are dispensable for its viability and signal transduction functions in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13937–13942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruya M, Sameshima M, Nemoto T, Yahara I. Monomer arrangement in HSP90 dimer as determined by decoration with N and C-terminal region specific antibodies. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:903–907. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Devin J, Sullivan WP, Toft D, Baulieu EE, Catelli MG. Mutational analysis of Hsp90 alpha dimerization and subcellular localization: dimer disruption does not impede “in vivo” interaction with estrogen receptor. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1677–1687. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Ota M, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Kaneko M. Identification of dimeric structure of proteins by use of the glutathione S-transferase-fusion expression system. Anal Biochem. 1995;227:396–399. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermann WM, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU. In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:901–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaretou B, Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. ATP binding and hydrolysis are essential to the function of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone in vivo. EMBO J. 1998;17:4829–4836. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard D, Khursheed B, Garabedian MJ, Fortin MG, Lindquist S, Yamamoto KR. Reduced levels of hsp90 compromise steroid receptor action in vivo. Nature. 1990;348:166–168. doi: 10.1038/348166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Toft DO. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Panaretou B, and Chohan S. et al. . 2000 The ATPase cycle of hsp90 drives a molecular ‘clamp’ via transient dimerization of the N-terminal domains. EMBO J. 19:4383–4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell. 1997a;90:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Roe SM, Piper PW, Pearl LH. A molecular clamp in the crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of the yeast Hsp90 chaperone. Nat Struct Biol. 1997b;4:477–482. doi: 10.1038/nsb0697-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radanyi C, Renoir JM, Sabbah M, Baulieu EE. Chick heat-shock protein of Mr = 90,000, free or released from progesterone receptor, is in a dimeric form. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2568–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafestin-Oblin ME, Lombes M, Couette B, Baulieu EE. Differences between aldosterone and its antagonists in binding kinetics and ligand-induced hsp90 release from mineralocorticosteroid receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41:815–821. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90430-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux S, Terouanne B, Couette B, Rafestin-Oblin ME, Nicolas JC. Conformational change in the human glucocorticoid receptor induced by ligand binding is altered by mutation of isoleucine 747 by a threonine. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10059–10065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah M, Radanyi C, Redeuilh G, Baulieu EE. The 90 kDa heat-shock protein (hsp90) modulates the binding of the oestrogen receptor to its cognate DNA. Biochem J. 1996;314:205–213. doi: 10.1042/bj3140205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel T, Siegmund HI, Jaenicke R, Ganz P, Lilie H, Buchner J. The charged region of Hsp90 modulates the function of the N-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1297–1302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel T, Weikl T, Buchner J. Two chaperone sites in Hsp90 differing in substrate specificity and ATP dependence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1495–1499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer LC, Picard D, Massa E, Harmon JM, Simons SS, Yamamoto KR, Pratt WB. Evidence that the hormone binding domain of steroid receptors confers hormonal control on chimeric proteins by determining their hormone-regulated binding to heat-shock protein 90. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5381–5386. doi: 10.1021/bi00071a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segnitz B, Gehring U. The function of steroid hormone receptors is inhibited by the hsp90-specific compound geldanamycin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18694–1701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Wolford RG, O'Neill TB, Hager GL. Characterization of transiently and constitutively expressed progesterone receptors: evidence for two functional states. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:956–971. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.7.0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soti C, Radics L, Yahara I, Csermely P. Interaction of vanadate oligomers and permolybdate with the 90-kDa heat-shock protein, Hsp90. Eur J Biochem. 1998;255:611–617. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins CE, Russo AA, Schneider C, Rosen N, Hartl FU, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent. Cell. 1997;89:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan WP, Toft DO. Mutational analysis of hsp90 binding to the progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20373–20379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylikomi T, Bocquel MT, Berry M, Gronemeyer H, Chambon P. Cooperation of proto-signals for nuclear accumulation of estrogen and progesterone receptors. EMBO J. 1992;11:3681–3694. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel U, Hausler C, Weeger M, Schmidt HH. Homodimerization of soluble guanylyl cyclase subunits. Dimerization analysis using a glutathione s-transferase affinity tag. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18149–18152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]