Abstract

Humoral immunity is characterized by the generation of Ab-secreting plasma cells and memory B cells that can more rapidly generate specific Abs upon Ag exposure than their naive counterparts. To determine the intrinsic differences that distinguish naive and memory B cells and to identify pathways that allow germinal center B cells to differentiate into memory B cells, we compared the transcriptional profiles of highly purified populations of these three cell types along with plasma cells isolated from mice immunized with a T-dependent Ag. The transcriptional profile of memory B cells is similar to that of naive B cells, yet displays several important differences, including increased expression of activation-induced deaminase and several antiapoptotic genes, chemotactic receptors, and costimulatory molecules. Retroviral expression of either Klf2 or Ski, two transcriptional regulators specifically enriched in memory B cells relative to their germinal center precursors, imparted a competitive advantage to Ag receptor and CD40-engaged B cells in vitro. These data suggest that humoral recall responses are more rapid than primary responses due to the expression of a unique transcriptional program by memory B cells that allows them to both be maintained at high frequencies and to detect and rapidly respond to antigenic re-exposure.

The acquisition of lifelong resistance to pathogens following resolution of the primary infection has been observed and documented for over 2 millennia (1). After centuries of research, it has become clear that the basis for this resistance is so-called immunological memory, in which Ag-specific B and T cells are maintained at higher frequencies than in the naive host, sometimes for the lifetime of the organism. Particular subsets of these Ag-specific memory B cells can rapidly respond to Ag re-exposure in a T cell-dependent manner (2, 3), thus generating a humoral recall response that is more rapid than the primary response. Furthermore, the Abs generated in the recall response tend to be of higher affinity to foreign Ags than those generated in the early phases of the primary response (4–8). Although there is a general consensus that the Ag-specific B cell precursor frequency is substantially increased in recall responses, there is considerable debate as to the mechanisms by which these increased frequencies are maintained. Several studies have concluded that Ag must persist to maintain and perpetually activate naive and memory B cells to maintain protective concentrations of neutralizing Abs (9, 10), whereas others have demonstrated that neither the immunizing Ag nor Ag-trapping immune complexes must be present to maintain memory B cells or long-lived plasma cells (11–14). Coupled with the findings that memory B cells return to a state of relative quiescence after surviving the germinal center reaction (15), the latter studies imply that B cell-intrinsic differences at least in part underlie the differences between primary and recall responses. However, the extent to which cell-intrinsic alterations in memory B cells are responsible for the increased Ag-specific B cell precursor frequencies and for the global differences between primary and recall responses is largely unknown.

Following the initial encounter with foreign protein Ags, Ag-specific naive B cells can differentiate within secondary lymphoid tissues into short-lived low-affinity Ab-secreting plasma cells or undergo a rapid proliferative phase known as the germinal center reaction, a T cell-dependent phase in which somatic hypermutation of the variable regions and Ig isotype switching occur (16, 17). A small fraction of these germinal center B cells survives the reaction (18) and proceeds to form either memory B cells or long-lived high-affinity Ab-secreting plasma cells, which are radioresistant and reside primarily within the bone marrow (13, 14, 19). Although the B cells are in the phase of antigenic stimulation, germinal center cells and early memory B cells temporarily lose homing receptors for lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches, but memory B cells later regain these homing receptors (L-selectin and integrin α4β7), and therefore regain the ability to survey these sites of new Ag deposition and presentation (20). Importantly, the early phases of mouse Ag-dependent differentiation are accompanied by the expression of unique combinations of surface markers that allow for the ready isolation of naive, plasma, and germinal center B cells. For example, naive follicular B cells, which are the major, but not exclusive (21, 22), source of precursors for memory B cells, express high levels of B220, CD23, and IgD, but low levels of IgM (23). Plasma cells express high levels of syndecan-1 (also known as CD138) and low levels of B220 (24), whereas germinal center B cells express high levels of B220 and low levels of surface Ig, and bind peanut agglutinin (PNA)3 (25). In contrast, whereas human memory B cells are identifiable through their expression of CD27 and several recent studies have examined the global gene expression profiles of these cells (26–28), the isolation of mouse memory B cells is more challenging in large part due to the absence of unequivocally characteristic markers. Many memory B cells have undergone Ig class switching and express isotypes other than IgM and IgD (16), but perhaps the best method to identify and purify homogenous preparations of memory B cells is through immunization with defined Ags and isolation of B cells specific for the immunizing Ag at time periods long after the germinal center reaction has ceased (29). This is an approach uniquely available to studies performed with animal models of Ag-dependent B cell differentiation.

We hypothesized that the differences between primary and recall humoral responses could be explained by distinct abilities of naive and memory B cells to detect Ags at sites of entry and/or distinct abilities to generate specific Abs upon antigenic encounter. To obtain evidence for or against this hypothesis, we compared the transcriptional programs of highly purified naive follicular, short-lived plasma, germinal center, and memory B cells. Our data suggest that memory B cells express a transcriptional program that allows for the maintenance of increased Ag-specific precursor cell frequencies, but also to efficiently survey peripheral sites of infection and rapidly obtain T cell help upon antigenic re-exposure.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the International Animal Care and Use Committee and Stanford University’s Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care. C57BL/Ka-Thy1.2 and Bmi1-deficient (30) mice were derived and maintained in our laboratory. Mist1-deficient mice were derived as previously described (31).

B cell purification

B cell purification was performed previously (32). To reiterate, male C57BL6/Ka mice (4–8 wk old) were immunized i.p. with 100 μg of hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl (NP)-chicken γ-globulin (CGG) (Biosearch Technologies) precipitated in 10% aluminum potassium sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich). Splenic plasma cells were harvested 7 days after immunization, germinal center B cells were sorted 14 days after immunization, and memory B cells were harvested 10–12 wk postimmunization. Naive cells were harvested from spleens of unimmunized mice. Splenocytes were first stained with unconjugated rat anti-mouse CD138 (BD Pharmingen) for plasma cells, biotinylated PNA for germinal center cells, or purified anti-Igλ for memory cells, and enriched using magnetically conjugated anti-rat or streptavidin beads (Miltenyi Biotec), followed by separation on AutoMacs columns (Miltenyi Biotec). The following Abs were used to stain cells as appropriate before FACS: anti-rat PE-Texas Red (Caltag Laboratories), anti-mouse Igλ FITC (BD Pharmingen), NP-PE (Biosearch Technologies), Cy5PE-conjugated lineage Abs (anti-mouse CD3, CD4, CD8, CD11b, Gr-1, and Ter119; eBiosciences), anti-mouse IgM allophycocyanin (BD Pharmingen), biotin-conjugated PNA (Sigma-Aldrich), streptavidin-Cy7PE (eBiosciences), anti-IgD FITC (eBiosciences), and anti-IgD biotin (eBiosciences). Cells were double sorted on a BD-FACS Aria directly into TRIzol (Invitrogen Life Technologies) before RNA amplification. Throughout the procedure, cells were maintained on ice and in 0.01% sodium azide.

B cell RNA processing and amplification

RNA isolation and amplification were performed in previous studies (32). Briefly, RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol and linear polyacrylamide (Ambion), according to manufacturer’s instructions (32). RNA was subjected to two rounds of amplification using Arcturus RiboAmp kits. After the second round of cDNA synthesis, Affymetrix IVT Labeling kits were used to generate biotin-labeled cRNA. Fragmented cRNA (10 μg) was hybridized to Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 microarrays.

Statistical analysis

Background subtraction and quantiles-based normalization were performed on previously obtained raw data (32) using the GCRMA algorithm (33), available fromwww.bioconductor.org. Normalized data sets for all transcripts with unlogged expression values above 20 were compared using the 2-class unpaired test with 100 permutations and the k-nearest neighbor imputer of Significance Analysis of Microarrays version 3.0 (34). All raw .CEL dataset files are available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession GSE4142).

DNA constructs

All cDNAs were cloned upstream of the internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) in murine stell cell virus (MSCV)-IRES-GFP (35). Klf2 cDNA was a gift from M. Jain (Harvard University, Boston, MA), Klf3 cDNA was a gift from M. Crossley (University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia), Klf9 was a gift from R. Simmen (University of Arkansas, Little Rock, AR), and Ski cDNA was a gift from K. Luo (University of California, Berkeley, CA). NF-κB1 and RelA retroviral constructs have been described previously (35), and NF-κB1-RelA fusion proteins were generated by insertion of 10 copies of an in-frame SerGly4 cassette downstream of NF-κB1 and upstream of RelA.

Retroviral production

Phoenix-eco cells (a gift from G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA) were plated to 60–80% confluency and transfected using calcium phosphate coprecipitation with 10 μg of control MSCV-IRES-GFP or MSCV-cDNA-IRES-GFP constructs. Medium was changed 6 h after transfection, and retroviral supernatant was harvested 48 h after transfection.

Retroviral transductions

Splenocytes were harvested from C57BL/Ka mice layered over a Histopaque 1077 gradient (Sigma-Aldrich), and spun for 20 min, room temperature, at 2000 × g. The interface was collected, washed, and stained with purified Abs against CD3 (2C11), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD5 (53-7.3), Gr-1 (8C5), CD11b (M1/70), Ter119, CD138 (281-2; BD Pharmingen), Ly77 (GL7; BD Pharmingen), and subsaturating doses of CD21/CD35 (7G6; BD Pharmingen). Stained splenocytes were depleted using sheep anti-rat Dynalbeads (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and the remaining cells were cultured for 24 h in freshly prepared B cell medium (RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) + 10% FCS (Omega Scientific) + 50 μM 2-ME + 10 mM HEPES + 10 μg/ml anti-IgM F(ab′)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) + 10 μg/ml anti-CD40 (1C11)) at 2 × 106 cells/ml/well of a 24-well plate. Cells were then resuspended in 2.5 ml of retroviral supernatant containing 4 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich), plated in 1 well of a 6-well plate, and spun at 2000 × g at room temperature for 1.5 h. Cells were washed and resuspended in 2 ml of B cell medium plated at 1 ml/well of a 12-well plate. LPS stimulations and infections were performed, as previously described (35). For division-tracking experiments, purified splenic B cells were resuspended at 107 cells/ml in PBS and labeled with 1 μM CellTrace Far Red DDAO-SE (Invitrogen Life Technologies) for 15 min at 37°C, according to manufacturer’s instructions, before stimulation with anti-IgM and anti-CD40. For annexin V experiments, cells were resuspended at 107 cells/ml in annexin V-binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2), stained with 20 μl/ml biotin-conjugated annexin V (Invitrogen Life Technologies) for 15 min at 4°C, washed, stained for 5 min with 1 μl/107 cells streptavidin Qdot 605 (Invitrogen Life Technologies), washed twice, and resuspended in annexin V-binding buffer containing 200 ng/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich).

ELISA

Mice were immunized i.p. with 100 μg of NP-CGG precipitated in 10% aluminum potassium sulfate as before. NP-specific ELISAs were performed with serum obtained 1 wk after immunization on high-protein-binding 96-well plates coated with 5 μg of NP-BSA (Biosearch Technologies). Wells were developed with anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Southern Biotechnology Associates), followed by 1 mg/ml ABTS reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), and the reactions were stopped by the addition of 0.1% sodium azide. Absorbance was read at a wavelength of 405 nm.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Cells were double sorted directly into TRIzol reagent, and RNA was prepared, as described above. cDNA was synthesized using the Superscript III kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies), according to manufacturer’s instructions, using random hexamers. Amplifications were performed using SYBR Green PCR core reagents (Applied Biosystems), and ~100 cell equivalents and transcript levels were quantified using an ABI 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences are as follows: β-actin, 5′-GTCTGAGGCCTCCCTTTTT-3′ and 5′-GGGAGACCAAAGCCTTCATA-3′; Aicda, 5′-GGGAAAGTGGCATTCACCTA-3′ and 5′-GAACCCAATTCTGGCTGTGT-3′; Bcl2, 5′-CCTGGCTGTCTCTGAAGACC-3′ and 5′-CTCACTTGTGGCCCAGGTAT-3′; Bcl6, 5′-CTGCAGATGGAGCATGTTGT-3′ and 5′-CGGCTGTTCAGGAACTCTTC-3′; Bcl-xL, 5′-ATCGTGGCCTTTTTCTCCTT-3′ and 5′-TGCAATCCGACTCACCAATA-3′; Bmi1, 5′-ATGAGTCACCAGAGGGATGG-3′ and 5′-AAGAGGTGGAGGGAACACCT-3′; Irf4, 5′-CTGAGTGGCTGTATGC CAGA-3′ and 5′-ATCAGCAATGGGAAAGTTCG-3′; Jun, 5′-TAACAGTGGGTGCCAACTCA-3′ and 5′-CGCAACCAGTCAAGTTCTCA-3′; Klf2, 5′-GCCTGTGGGTTCGCTATAAA-3′ and 5′-TTTCCCACTTGGGATACAGG-3′; Klf3, 5′-CTAGAAGGCGTGGCTGAAAG-3′ and 5′-GTA ATTCGACGGGAAGGACA-3′; Mist1, 5′-AGCTGTTGTCCCTCTGTGCT-3′ and 5′-GATGGAGGTGAGGAGGATCA-3′; Prdm1, 5′-CCCCTCATCGGTGAAGTCTA-3′ and 5′-CTGGAATAGATCCGCCAAAA-3′; Ski, 5′-AAAAGCCCTCCGCTCTAGTC-3′ and 5′-GACGTCAGGGCTTAGCAGTC-3′.

Results

Memory B cells are more similar to naive than germinal center B cells

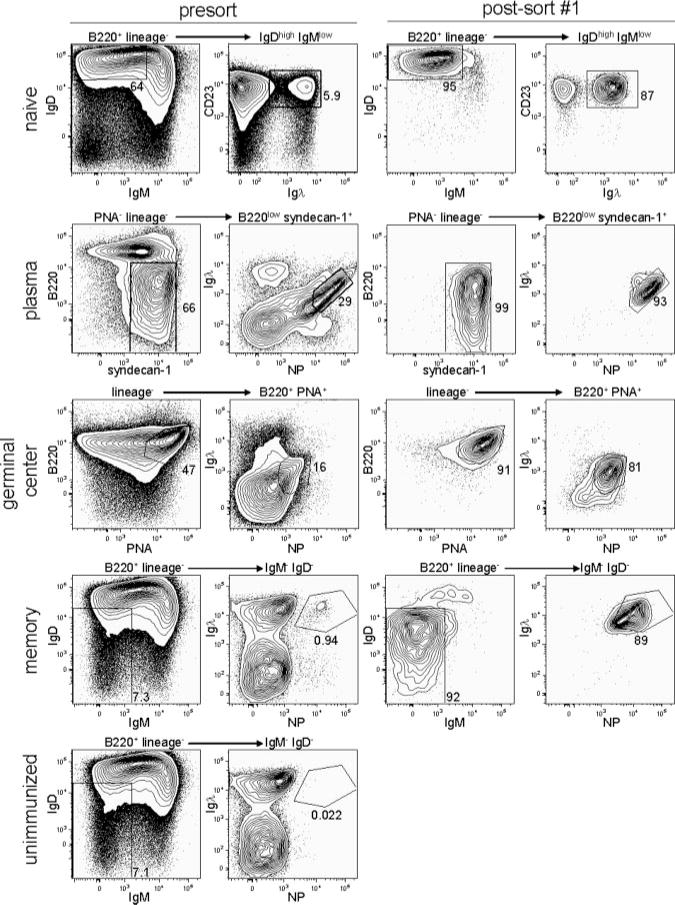

Naive follicular B cells from unimmunized mice or short-lived plasma, germinal center, and memory B cells from mice immunized with alum-precipitated NP-CGG were sorted, and microarray RNA hybridizations were performed in previous studies in which we compared the transcriptional profiles of self-renewing memory B and T lymphocytes with those of hemopoietic stem cells (32). Additional examples of gating strategies and postsort purities are shown in Fig. 1. In all cases, propidium iodide+ nonviable cells were excluded from the sorts. Purities following the first sort were typically 80–90%, and these cells were again sorted directly into lysis buffer before RNA amplification to ensure homogeneity of the starting population. Only isotype-switched IgM−IgD− memory B cells were considered in this study because the background frequencies of NP-binding B cells in this subpopulation in unimmunized mice were very low, usually <5% of that observed in immunized animals (Fig. 1, bottom row). Consistent with previous descriptions (36), these cells were uniformly CD38high, whereas only ~15% of germinal center B cells expressed CD38 (data not shown). Typically, we were able to isolate 500–2000 NP-specific memory B cells per spleen. These Ag-specific memory B cells were almost exclusively of the IgG1 isotype (data not shown). Adoptive transfer of 750–1000 of these memory B cells alongside primed T cells into RAG2−/− mice, followed by immunization with NP-CGG, led to clearly measurable recall responses, whereas detectable, but smaller recall responses could be observed by transfer of as few as 150 memory B cells (32).

FIGURE 1.

Naive follicular and Ag-specific plasma, germinal center, and memory B cells can be highly purified from wild-type mice. Gating strategies and purities of the starting populations are shown in the left panels. Plasma cells, germinal center cells, and memory B cells were harvested from spleens 7, 14, or >70 days, respectively, after immunization with 100 μg of NP-CGG. Unimmunized mice were injected with only alum. Cells were analyzed after the first sort, shown in the right panels, and sorted again directly into TRIzol to ensure further purity. Plasma and germinal center B cells were enriched using magnetic enrichment of syndecan-1+ or PNA-binding cells, respectively, before FACS.

cRNA was amplified from these four B cell populations and hybridized to Affymetrix 430 2.0 Arrays, as previously described (32). Background subtraction and normalization of the resulting data were performed using the GCRMA algorithm (33). Genes with median expression values <20 in all four B cell populations were not considered to be differentially expressed because we have been unable to consistently obtain RT-PCR products for transcripts at these levels (our unpublished observations). Significance analysis of microarrays (34) was then used for pairwise comparisons of all transcripts with median expression values >20 in at least one of the B cell populations, and genes differentially expressed by at least 2-fold and with a q value of <10 were identified. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed on 12 genes (Aicda, Bcl2, Bcl6, Bcl-xL, Bmi1, Irf4, Jun, Klf2, Klf3, Mist1, Prdm1, and Ski) to confirm the relative expression levels obtained by microarray analysis. These data revealed no false positives or negatives with respect to significant gene expression differences between the four populations, but did show that fold changes were on average underestimated by 1.5-fold in the microarray experiments relative to quantitative RT-PCR (data not shown), consistent with previous observations (32). Interestingly, naive and memory B cells showed differential expression of only 2904 of a total of 45,101 transcripts analyzed, demonstrating a ~94% overlap in their transcriptional profiles (Supplemental Table I).4 In contrast, the transcriptional profile of germinal center B cells showed 85% overlap with that of memory B cells (Supplemental Table II). These data demonstrate that, consistent with studies performed on human CD27+ tonsillar B cells (26), mouse memory B cells acquire a transcriptional profile that is more similar to that of naive B cells than that of germinal center B cells. Nevertheless, clear cell-intrinsic differences do exist between naive and memory B cells that may explain the changes in the kinetics and magnitude between primary and recall responses to Ag.

Importantly, the expression of a number of genes induced by Ag receptor signaling (37), such as Spred2, Umpk, Pigr, Slc31a1, and Tgfβ3, remained relatively low (less than a value of 100) in both naive and memory B cells (Supplemental Table VII). Conversely, the expression of a number of genes repressed by Ag receptor signaling (37), such as Hck, Ptch1, Acp5, Hist1h1c, and Adrbk1, remained relatively high (greater than a value of 100) in both naive and memory B cells (Supplemental Table VII). These data demonstrate that the process of purification using Ig-specific reagents did not meaningfully alter the endogenous gene expression profiles of these B cell subsets.

Although our data are largely consistent with previous experiments, several notable differences were apparent. Whereas human memory B cells express the proapoptotic molecules Bik and Fas at levels similar to those in germinal center B cells (26), mouse memory B cells expressed lower relative levels of these molecules, more similar to those in naive B cells than in germinal center B cells (Supplemental Table VII). In addition, unlike human memory B cells (26), mouse memory B cells did not express detectable levels of IL-2Rβ or CD27 (Supplemental Table VII). Moreover, c-jun expression was very low in mouse, but not human, naive, and memory B cells (26, 28).

Transcriptional regulators influence memory B cell formation and plasma cell function

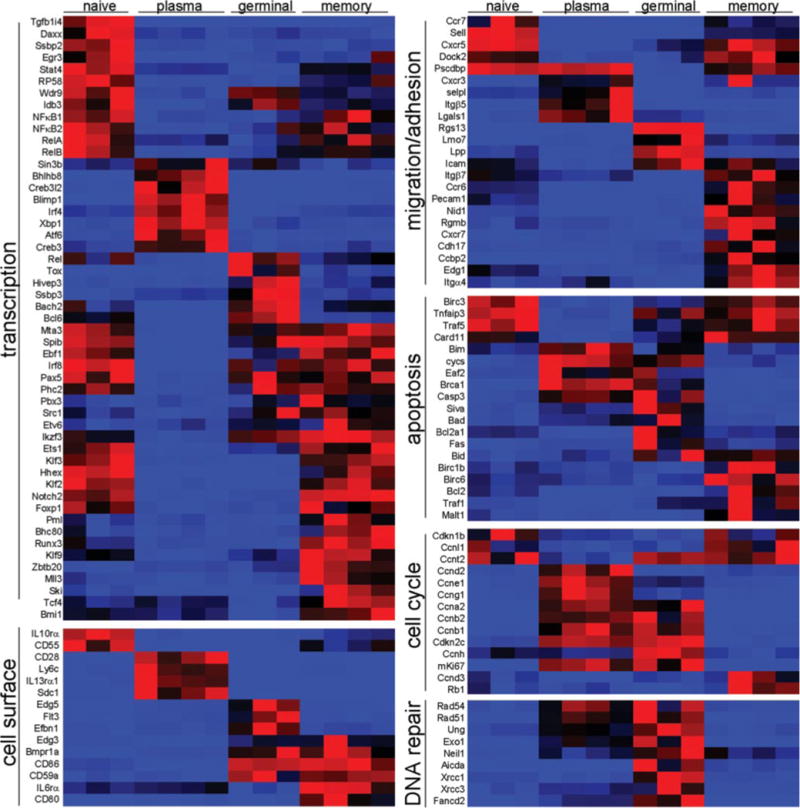

To identify factors that are involved in the generation of memory B cells from the germinal center reaction and in distinguishing primary and recall B cell responses, we assigned functional categories, based on Gene Ontology classifications (38) and evaluations of the relevant literature, to selected genes that were differentially expressed during Ag-dependent B cell differentiation. Because much of the work to date regarding cell-intrinsic control of B cell responses has focused on transcriptional regulators, we first examined this functional category of genes in the heatmap shown in Fig. 2. Numerical fold changes between the different populations and absolute expression values are listed in Supplemental Tables I–VI and Supplemental Table VII, respectively. Importantly, factors that have been demonstrated to influence the germinal center reaction, such as Bcl6 (39) and Bach2 (40), as well as genes that regulate plasma cell fate decisions, such as Prdm1 (also known as Blimp-1) (41, 42) and Xbp1 (43), were differentially expressed by the appropriate lineages (Fig. 2). Similar to human memory B cells generated in vitro (28), the levels of Bcl6 transcripts were lower in mouse memory B cells relative to both germinal center and naive B cells (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table VII). These data are consistent with recent studies that demonstrate an inhibitory role of Bcl6 in memory formation (28), but are inconsistent with other studies that suggest Bcl6 expression promotes self-renewal and memory formation (44, 45). Consistent with previous studies (46), we found that Irf4 transcript levels were very highly expressed in plasma cells, but not in germinal center B cells (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table VII), despite the observation that Irf4 is required for efficient Ig isotype switching (47). It is possible that the 3–10% of germinal center cells that do express Irf4 (46) are the only ones destined for isotype switching.

FIGURE 2.

Cell-intrinsic differences between naive follicular, plasma, germinal center, and memory B cells. Selected genes with statistically significant transcriptional differences between at least two of the analyzed B cell populations are shown in heatmap form. Functional categories were assigned based on a combination of Gene Ontology categorization and literature searches. Red represents high relative levels of expression, and blue represents low relative transcript levels.

Relatively few transcription factors were uniquely expressed in naive B cells; however, a number of transcription factors were commonly enriched in naive and memory B cells, such as Ets1, Klf2, Klf3, Hhex, FoxP1, and Notch2 (Fig. 2). Given the prolonged lifespans and proliferative quiescence of both naive and memory B cells (15, 48, 49), these factors may play roles in the prevention of apoptosis and/or in the prevention of cellular division. Indeed, such a functional role has been proposed for Klf2 in the survival and maintenance of quiescence in naive and memory T cells (50, 51).

A number of transcriptional regulators were specifically up-regulated in memory B cells, including Klf9 (also known as Bteb1), Ski, Mll3, Pml, Tcf4, and Bmi1. Interestingly, several of these factors were also enriched in hemopoietic stem cells relative to their more differentiated progeny, suggesting that they may play a functional role in the maintenance and self-renewal of memory B cells (32).

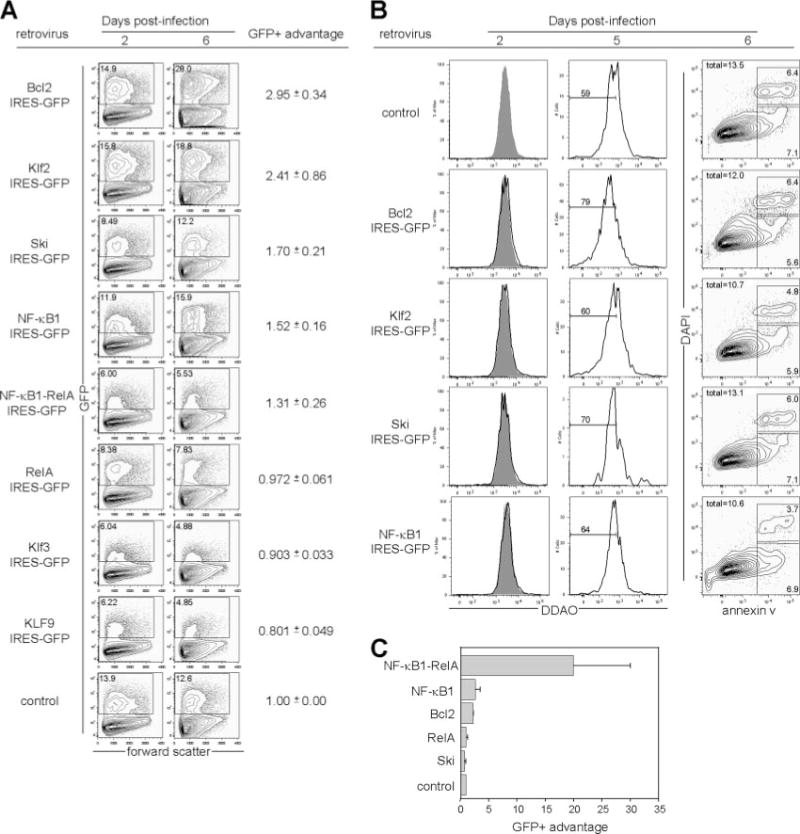

Although transgenic expression of Bcl2 can significantly enhance the proportion of memory B cells that survives the germinal center reaction, it does not provide absolute protection (18, 52). Moreover, we did not find Bcl-x (also known as Bcl2l1), the transgenic expression of which can protect germinal center B cells (53), to be differentially regulated among the different B cell populations (Supplemental Table VII). To identify additional factors that can impart a competitive advantage to germinal center B cells, we retrovirally transduced naive splenic B cells stimulated with anti-IgM and anti-CD40, which mimic certain aspects of the germinal center reaction (54, 55), with several of the differentially regulated transcription factors and suspected antiapoptotic genes specifically enriched in memory B cells relative to germinal center B cells. Cultures were then analyzed at 2 and 6 days after infection to determine whether cells retrovirally transduced with these genes were overrepresented relative to control virus-transduced cells using a previously described formula (56). Cells retrovirally transduced with Bcl2, Klf2, Ski, or NF-κB1 (57) showed a clear and consistent increase in representation at day 6 relative to the starting percentage at day 2 (Fig. 3A). Retroviral expression of Klf3 and Klf9 did not measurably enhance the number of Ag receptor and CD40-engaged B cells in this assay.

FIGURE 3.

B cells use unique mechanisms to survive T-dependent and T-independent responses. A, Retroviral expression of Klf2, Ski, or NF-κB1 provides a competitive advantage to anti-IgM- plus anti-CD40-stimulated B cells. Naive splenic follicular B cells were purified through depletion of non-B lineage and syndecan-1+, GL-7+, and CD21high cells; stimulated with anti-IgM and anti-CD40; and transduced with the indicated retrovirus. The percentage of GFP+ cells was quantified at 2 and 6 days postinfection. The GFP+ advantage was quantified as follows: ((% GFP + day 6)(% GFP − day 2))/((% GFP + day 2)(% GFP − day 6)), and normalized to the control virus for each experiment. Representative plots from one experiment are shown, and the mean ± SEM values are displayed to the right for four independent experiments. B, Retroviral expression of Bcl2, Ski, and NF-κB1, but not Klf2, extends the number of divisions that B cells undergo. Cells were labeled with Far Red DDAO, stimulated, and infected as above, and DDAO expression levels in GFP+ cells were monitored at 2 and 5 days postinfection. Gray-shaded histograms in the day 2 plots represent control virus-transduced cells, and overlaid unfilled histograms represent cells transduced by the indicated retrovirus. The percentage of GFP+ cells that had undergone 7 or more divisions, calculated by dilution of DDAO signal relative to day 0, is shown in the day 5 plots. In a separate experiment, cells were stained at day 6 postinfection with annexin V and DAPI to quantify apoptotic cells within the GFP+ population. C, Retroviral expression of NF-κB heterodimers and Bcl2, but not Klf2 or Ski, protects LPS-stimulated B cells. LPS-stimulated splenic follicular B cells purified as above were transduced with the indicated retroviruses, and GFP+ advantage was calculated as above. Mean ± SEM values from three independent experiments are shown.

To determine the proliferative effects of the genes that led to this increased representation after infection, we labeled B cells with Far Red DDAO-SE, a division tracking dye. At 2 and 3 days postinfection (Fig. 3B, left column, and data not shown), no difference in the rate of proliferation between control virus-transduced cells and cells transduced with Bcl2, Klf2, Ski, or NF-κB1 was observed. By day 5, however, a significantly higher proportion of cells transduced with Bcl2, Ski, or NF-κB1 had undergone 7 or more divisions than cells transduced with a control virus, as measured by dilution of DDAO signal (Fig. 3B, middle column). In contrast, little difference was seen in the divisional profile between control-transduced and Klf2-transduced cells. These data suggest that whereas these genes may not influence the rate of B cell proliferation at early timepoints in culture, retroviral expression of Bcl2, Ski, or NF-κB1 can extend the number of divisions that B cells can undergo in vitro.

To determine the antiapoptotic effects of these genes, we stained cells in a separate experiment 6 days after infection with annexin V (58) and DAPI to identify preapoptotic and recently apoptotic cells. Retroviral expression of Bcl2 led to a ~10% reduction in the percentage of annexin V+ cells relative to control virus-transduced cells, whereas retroviral expression of Klf2 or NF-κB1 led to ~20% reductions in the percentage of annexin V+ cells (Fig. 3B, right column). In contrast, the percentage of annexin V+ cells in Ski-transduced cells was similar to that of control virus-infected cells (Fig. 3B, right column). Although these reductions in apoptosis were modest and thus somewhat surprising in the case of Bcl2, it is worth noting that GFP is retained for only short periods of time in apoptotic cells (59) and that these data provide at most a snapshot of a continuous process. A 10–20% survival advantage applied continuously over the course of the 6-day experiment might well contribute to the competitive advantage observed in cells transduced with Bcl2, Klf2, and NF-κB1. In contrast, retroviral expression of Ski appears to impart a competitive advantage over control virus-transduced cells solely by extending the number of divisions that B cells can undergo.

Surprisingly, despite well-described roles for RelA in the prevention of apoptosis (60), retroviral expression of RelA or a covalently linked dimer of NF-κB1 and RelA, which behaves similarly to cotransfections of NF-κB1 and RelA in transcriptional reporter assays (data not shown), did not measurably protect cells (Fig. 3A), suggesting that NF-κB1-containing dimeric complexes other than the canonical NF-κB1-RelA heterodimer may be involved in preventing apoptosis of Ag receptor and CD40-engaged B cells. In contrast, retroviral expression of the NF-κB1-RelA heterodimer provided protection to LPS-treated B cells at a significantly higher level than that provided even by retroviral expression of Bcl2 (Fig. 3B). Additionally, retroviral expression of Ski did not affect the survival of LPS-stimulated cells (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that, as others have also found (61, 62), B cells use distinct mechanisms to survive T-dependent and T-independent reactions.

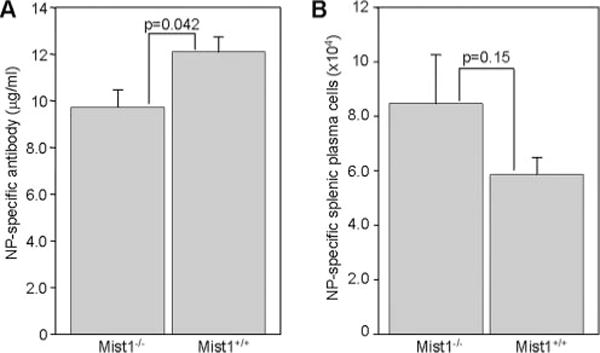

Transcription factors such as Blimp-1 drive differentiation to the Ab-secreting plasma cell fate in part through the transcriptional repression of germinal center-associated factors such as Bcl6 (63). Other factors involved in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response such as Xbp1 have also been shown to be important for plasma cell differentiation (43). We identified several other transcription factors, including the basic helix-loop-helix protein 8, more commonly known as Mist1 (64), as having very similar expression patterns to Blimp-1, Xbp1, and Irf4 (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Figs. 4–6). Because Mist1 is required for proper granule organization in both pancreatic and gastrointestinal exocrine cells (31, 65), we hypothesized that this gene may be important for plasma cell generation and/or function. Serum levels of NP-specific Ab were modestly, but statistically significantly decreased in NP-CGG-immunized Mist1−/− animals relative to wild-type control mice (Fig. 4A). However, no significant difference was observed in the numbers of splenic plasma cells that were generated 7 days after immunization of Mist1−/− mice (Fig. 4B), suggesting that Mist1 expression may affect the function, but not the generation of short-lived plasma cells.

FIGURE 4.

Mist1 expression affects the function, but not the formation of short-lived plasma cells. Mist1−/− or age-matched wild-type controls were immunized with NP-CGG, and serum (A) and spleens (B) were harvested 7 days later. Serum titers of NP-specific Abs (A) and the total number of splenic B220low syndecan-1+ NP+ cells (B) are shown. Mean ± SEM values are shown from a total of 10 Mist1−/− and 9 Mist+/+ mice analyzed in two independent experiments.

Bmi1 is highly expressed in hemopoietic stem cells and is critical for their self-renewal (66, 67). Because memory B cells express 13-fold higher levels of Bmi1 than do their germinal center precursors (Supplemental Fig. 2), we hypothesized that Bmi1 may also be important for the generation or self-renewal of memory B cells. To address this issue, Bmi1-deficient (30) or control littermates were immunized with NP-CGG and spleens were harvested 4 wk after injection. NP-binding memory B cells were clearly apparent in Bmi1−/− mice, indicating that Bmi1 expression is not essential for the formation of memory B cells (Fig. 5). Although the absolute numbers of memory B cells were decreased by 10-fold in Bmi1−/− spleens, the total number of naive B cells from which memory B cells arise was also decreased by ~10-fold in unimmunized animals relative to wild-type mice (data not shown). Thus, no B cell-intrinsic requirement for Bmi1 expression exists for the formation of memory cells. Because, however, Bmi1-deficient animals rarely survived past 8 wk of age, we were unable to determine whether Bmi1 is required for the long-term maintenance of the memory B cell compartment in this study. Future studies using conditional deletions of Bmi1 will most likely be required to address this question.

FIGURE 5.

Bmi1 is not required for the generation of memory B cells. Bmi1−/− or wild-type littermates were immunized with NP-CGG, and spleens were harvested 4 wk after immunization. Plots show only B220+ Igλ+ cells, and memory cells are identified as IgD− NP+ cells.

Unique combinations of homing receptors and costimulatory molecules are expressed by memory B cells

Germinal center B cells do not have the capacity to home effectively to secondary lymphoid tissues from the vasculature in part due to expression of chemotaxis-attenuating molecules such as Rgs13 and repression of adhesion molecules such as L-selectin (68 –71). In contrast, memory B cells reacquire expression of several of the receptors involved in both homing and egress to and from secondary lymphoid tissues such as L-selectin (Fig. 2), consistent with previous observations (20, 68). Memory B cells also reacquire expression of Edg1 (also known as sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) (Fig. 2), a molecule that is critical for lymphocyte egress from the thymus and secondary lymphoid tissues (72, 73). Interestingly, however, memory B cells express slightly lower levels of L-selectin than naive B cells (Figs. 2 and 6B), but comparable levels of S1P1 (Fig. 2). These data suggest that memory B cells may have a shorter extravascular residence time than their naive counterparts. In addition, transcripts for the chemokine receptor CCR6, normally associated with homing to mucosal sites (74), were enriched in memory B cells relative to naive follicular, plasma, and germinal center B cells.

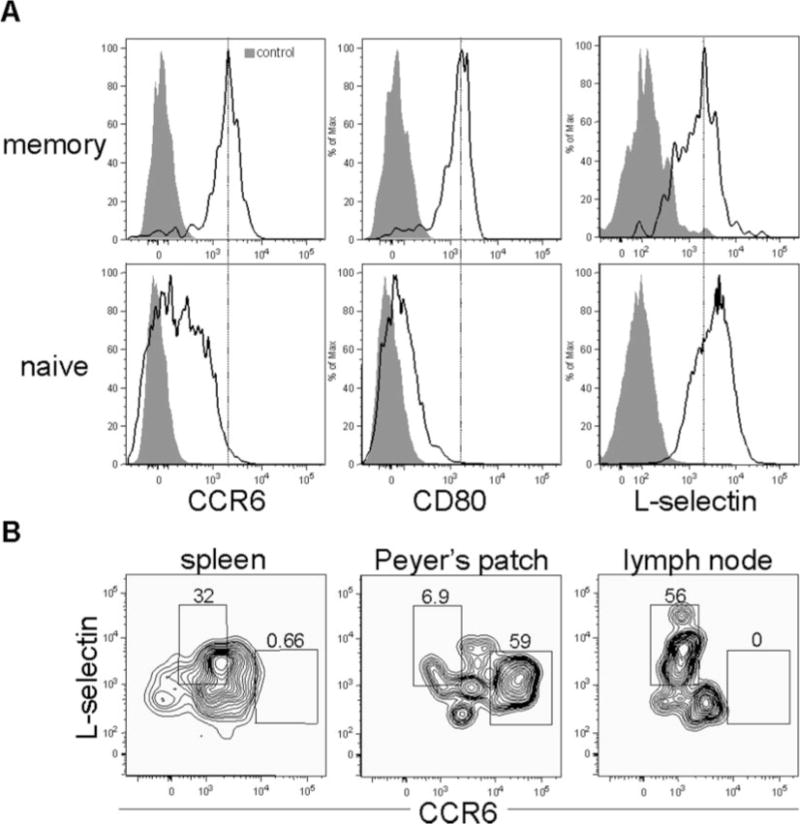

FIGURE 6.

Memory B cells simultaneously express molecules associated with both lymph node and mucosal homing. A, Splenic memory and naive B cells express differential levels of CCR6, CD80, and L-selectin. Naive follicular (B220+ IgMlow IgDhigh Igλ+ NP−) and memory B cells (B220+ IgM− IgD− Igλ+ NP+) were analyzed for expression of CD80 and CCR6. Mice were immunized 10 wk before analysis. Gray shaded plots represent fluorescence minus one controls (92), and black unfilled histograms represent cells stained with anti-CCR6, anti-CD80, or anti-L-selectin. B, Differential expression of CCR6 and L-selectin between memory B cells in spleen, Peyer’s patch, and peripheral lymph nodes. Expression of L-selectin and CCR6 was analyzed on B220+ IgM− IgD− Igλ+ NP+ memory B cells isolated from the spleen, Peyer’s patch, and brachial and axillary lymph nodes isolated from mice immunized 12 wk beforehand with NP-CGG.

In addition, memory B cells also displayed enhanced expression levels of certain cell surface markers relative to naive follicular B cells such as the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table Ia). The increased expression of CD80 and CD86 suggests that memory B cells have enhanced abilities to elicit T cell help upon Ag re-exposure (75). The above data suggest that humoral recall responses occur more quickly than primary responses because memory B cells can rapidly detect foreign Ag by surveying peripheral mucosal sites and, upon encountering foreign Ag, expeditiously elicit T cell help through constitutive expression of the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. To determine what fraction of splenic memory B cells exhibits properties consistent with these hypotheses, we stained these cells for surface expression of CCR6, CD80, and L-selectin. Splenic memory B cells expressed uniformly high cell surface levels of both CD80 and CCR6 and clearly expresssed L-selectin as well, although at slightly lower levels than naive B cells (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the expression of CD80 and CCR6 in naive B cells was heterogeneous and weaker than that of memory B cells (Fig. 6A). A recent study found more heterogeneous expression of CD80 in memory B cells than we observed in this study, with the CD80− cells representing cells that had undergone minimal somatic hypermutation (76). The reason for these differences is not clear, but may relate to the use of BCR H chain transgenic mice in their study, which have a relatively high precursor frequency of Ag-specific B cells, vs wild-type mice used in our study, which may have a higher selective pressure to expand high-affinity somatically hypermutated B cell clones.

The functional purpose of high levels of CCR6 expression on splenic memory B cells is unclear, because CCR6 is not required for homing to the spleen or for proper splenic architecture (74). We hypothesized that the high basal levels of CCR6 expression may allow for splenic memory B cells to migrate to mucosal sites more rapidly than naive cells through relatively modest changes in CCR6 surface expression. To test this hypothesis, we compared CCR6 and L-selectin expression levels on memory B cells isolated from the spleen, Peyer’s patch, and brachial and axillary lymph nodes. Memory B cells isolated from the Peyer’s patch expressed significantly higher levels of CCR6 than their splenic or lymph node counterparts, whereas memory B cells isolated from the peripheral lymph nodes expressed considerably less CCR6 than their splenic or Peyer’s patch counterparts (Fig. 6B). The level of CCR6 expression of naive Peyer’s patch B cells was similar to that of Peyer’s patch memory B cells (data not shown). Thus, the difference in surface expression levels of CCR6 between naive splenic and naive Peyer’s patch B cells appears to be much greater than the difference between splenic memory and Peyer’s patch memory B cells.

Expression of activation-induced deaminase (AID) is maintained in memory B cells

Consistent with previous studies, AID (77, 78), a gene involved in both isotype switching and somatic hypermutation, was highly expressed in germinal centers (Fig. 2). Unexpectedly, although memory B cells had 9-fold lower transcript levels relative to germinal center B cells (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table IIb), they retained 53-fold higher levels of AID expression than did naive follicular B cells (Supplemental Table Ia), suggesting that they may either be poised to rapidly undergo additional rounds of isotype switching and somatic hypermutation upon Ag re-exposure, or in fact are undergoing low levels of somatic mutation to diversify the affinity profile of the memory B cell pool. The detection of AID transcripts in the memory B cell population is unlikely to result solely from contamination with germinal center B cells, which express low levels of CD38 (36), because we observed high levels of CD38 expression on >99% of our sorted memory B cells. In contrast, to achieve the level of AID expression in memory B cells that we detected, contamination by germinal center B cells would have had to approach 10%. Importantly, continued AID expression in human memory B cells has also been independently observed (28, 79). Thus, conventional memory B cells appear to differ with respect to AID expression relative to the blood-borne NP-binding B cells that appear at short timepoints after immunization (80). Similarly, whereas memory B cells expressed 57-fold lower levels of the proliferation marker mKi67 than germinal center B cells (Supplemental Table II), they expressed 20-fold higher levels of mKi67 than naive B cells (Supplemental Table I), consistent with their ability to self renew.

Discussion

The ability to generate lasting immunity to harmful pathogens underlies the basis for successful vaccinations. To date, the success of such vaccines has depended upon the generation of protective humoral responses to the immunizing Ags (81). Humoral immunity is thought to consist of two components, the production of neutralizing Abs by plasma cells (13, 19, 82) and the maintenance of memory B cells that can generate rapid and high-affinity recall responses upon re-exposure to the foreign Ag. In this study, we have examined the cell-intrinsic basis for the difference between primary and recall Ab responses using global gene expression analysis. Our data demonstrate that memory B cells adopt a transcriptional program that may allow them not only to survive the germinal center reaction, but to persist long after the germinal center reaction has ceased, thereby maintaining an increased Ag-specific precursor pool than that which is observed before the initial response. This increased Ag-specific B cell precursor frequency alone might be sufficient to increase the rate at which foreign Ag is detected as well as the rate at which T cell help is recruited after such detection (83). Nevertheless, we also found evidence that memory B cells express high levels of chemotactic molecules generally associated with trafficking to mucosal sites such as the Peyer’s patch. Moreover, memory B cells constitutively express costimulatory molecules that most likely aid in rapidly activating cognate Th cells.

B cells express a multitude of chemotactic receptors and cell surface adhesion molecules that allow them to traffic to and from secondary lymphoid organs through the blood and lymph (84). Evidence that distinct subsets of B cells express unique combinations of organ-specific homing molecules first came from work demonstrating that lymphocytes isolated from the Peyer’s patch adhere more efficiently to high endothelial venules within the Peyer’s patch than lymphocytes isolated from axillary and brachial lymph nodes (85). Moreover, lymphocytes from peripheral lymph nodes homed more efficiently back to peripheral lymph nodes than did lymphocytes isolated from the Peyer’s patch after i.v. injection (85). Further work demonstrated that L-selectin was essential for homing to peripheral lymph nodes, but not to the Peyer’s patch (68). Consistent with the importance of L-selectin in extravasation and homing to peripheral lymphoid tissues, germinal center B cells lack expression of L-selectin and thus cannot home effectively upon adoptive transfer (71). Our data demonstrate that memory B cells that survive the germinal center reaction reacquire expression of not only L-selectin (20), although to lower levels than is observed in naive B cells, but also of S1P1, a receptor demonstrated to be critical for lymphoid egress from secondary lymphoid tissues into the blood (72, 73). Surprisingly, these splenic memory B cells also express uniformly high levels of receptors associated with homing to mucosal sites such as CCR6 (74). The simultaneous expression on memory B cells of receptors important for egress into the blood as well as for homing to both lymph nodes and the Peyer’s patch suggests that these cells are poised to rapidly migrate out of the spleen to potential sites of infection. Although splenic memory B cells express lower levels of CCR6 than memory B cells within the Peyer’s patch (Fig. 6B), this difference is relatively minor when compared with the difference in naive B cells in these two tissues. Thus, relatively subtle cues or stochastic signals may direct splenic memory B cells to relocalize to mucosal sites, and thus, the spleen may act as a repository for migratory memory B cells. These same subtle cues may not be sufficient to relocalize naive splenic B cells, which express much lower starting levels of CCR6. Because recent studies have clearly shown that B cells can directly take up Ag within minutes of administration without exposure to dendritic cells (86), our data suggest that the facile ability of memory B cells to home to multiple secondary lymphoid organs would increase the likelihood that foreign Ags are detected and responded to rapidly.

Upon antigenic encounter, memory B cells appear poised to more rapidly respond than naive B cells to foreign pathogens. Consistent with the previous studies performed on human tonsillar memory B cells (26, 75), murine memory B cells express constitutively high levels of CD80 and CD86. Because both primary and recall responses to protein Ags depend upon the presence of T cells (2, 3), the constitutive expression of costimulatory molecules most likely allows memory B cells to more rapidly obtain T cell help than naive B cells upon contact with cognate T cells. Moreover, the constitutive expression of genes such as AID indicates that memory B cells remain poised to undergo additional rounds of Ig isotype switching and somatic hypermutation upon antigenic encounter. Alternatively, it is also possible that low levels of somatic hypermutation continue in memory B cells, even after Ag has presumably been cleared, to diversify the Ab repertoire and guard against secondary exposure to escape variants. Several recent studies have also shown that engagement of IgG1 Ag receptors produces more calcium influx than is produced by engagement of IgM receptors (37, 87), whereas other reports have shown that human memory B cells can more easily respond to TLR stimuli than naive B cells (88), thus providing additional potential molecular mechanisms by which recall responses differ from primary responses.

Interestingly, we also found differences between naive and memory B cells with respect to several antiapoptotic genes such as Bcl2 and Birc6. Through the expression of higher levels of antiapoptotic factors, memory B cells may persist longer than naive B cells, possibly maintaining themselves for life. This hypothesis is consistent with the finding that transgenic Bcl2 expression reduces the rate of B cell turnover (89). Coupled with our earlier findings that memory lymphocytes may share certain aspects of a transcriptional program of self-renewal with hemopoietic stem cells (32), these data suggest that memory B cells maintain themselves at higher frequencies than their Ag-specific naive counterparts through a cell-intrinsic transcriptional program specifically adapted for this purpose.

Importantly, the expression of a number of factors appears to be restricted exclusively to memory B cells, suggesting that memory B cells are a discrete entity and cannot be simply characterized as existing in an intermediate state between germinal center and naive B cells. It is important to note, however, that our study focused only on isotype-switched memory B cells. As previous studies have suggested, memory B cells that continue to express the IgM isotype may represent a distinct entity altogether (90), a portion of which may be derived from B1 and marginal zone B cells (21, 22). Indeed, one study has found that a portion of IgM+ Ag-binding memory B cells is localized to the splenic marginal zone in rats (91). In contrast, our data suggest that isotype-switched memory B cells are unlikely to be sessile in nature.

Although a significant amount of work has been performed to identify factors that regulate plasma and germinal center fate decisions, relatively little is known about the intrinsic differences that are important for directing memory B cell differentiation from germinal center precursors. The memory B cell-enriched genes identified in this study serve as excellent candidates in directing the transition from germinal center to memory B cells. For example, two of the factors we found to be specifically enriched in memory B cells relative to their germinal center precursors, Ski and Klf2, imparted a competitive advantage to anti-IgM- and anti-CD40-stimulated B cells, suggesting a role in memory B cell differentiation. Thus, our study establishes a basis for the identification of genes differentially regulated during Ag-dependent B cell differentiation and for the assignment of functional roles to these factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Jerabek for laboratory management, C. Muscat for Ab production, J. Dollaga and D. Escoto for animal care, and L. Herzenberg for helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01DK053074 (to I.L.W.). D.B. was supported by a fellowship from the Cancer Research Institute and from the National Institutes of Health (T32AI0729022), C.B.F. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the National Science Foundation, and N.H. was supported by a fellowship from the Japanese Society of Promotion of Science, Yamada Memorial Foundation, and Mitsubishi Pharma Research Foundation.

Abbreviations used in this paper: PNA, peanut agglutinin; AID, activation-induced deaminase; CGG, chicken γ-globulin; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; IRES, internal ribosomal entry site; MSCV, murine stem cell virus; NP, hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl; S1P1, sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor 1.

The on-line version of this article contains supplemental material.

Disclosures

Affiliations that might be perceived to have biased this work are as follows: Irving L. Weissman was a member of the scientific advisory board of Amgen and owns significant Amgen stock; and Irving L. Weissman co-founded and consulted for Systemix, is a cofounder and director of Stem Cells, and recently cofounded Cellerant. All other authors do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raff MC. Role of thymus-derived lymphocytes in the secondary humoral immune response in mice. Nature. 1970;226:1257–1258. doi: 10.1038/2261257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell GF, Chan EL, Noble MS, Weissman IL, Mishell RI, Herzenberg LA. Immunological memory in mice. 3. Memory to heterologous erythrocytes in both T cell and B cell populations and requirement for T cells in expression of B cell memory: evidence using immunoglobulin allotype and mouse alloantigen markers with congenic mice. J Exp Med. 1972;135:165–184. doi: 10.1084/jem.135.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bothwell AL, Paskind M, Reth M, Imanishi-Kari T, Rajewsky K, Baltimore D. Somatic variants of murine immunoglobulin light chains. Nature. 1982;298:380–382. doi: 10.1038/298380a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffiths GM, Berek C, Kaartinen M, Milstein C. Somatic mutation and the maturation of immune response to 2-phenyl oxazolone. Nature. 1984;312:271–275. doi: 10.1038/312271a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berek C, Griffiths GM, Milstein C. Molecular events during maturation of the immune response to oxazolone. Nature. 1985;316:412–418. doi: 10.1038/316412a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meffre E, Catalan N, Seltz F, Fischer A, Nussenzweig MC, Durandy A. Somatic hypermutation shapes the antibody repertoire of memory B cells in humans. J Exp Med. 2001;194:375–378. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gowans JL, Uhr JW. The carriage of immunological memory by small lymphocytes in the rat. J Exp Med. 1966;124:1017–1030. doi: 10.1084/jem.124.5.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray D, Skarvall H. B-cell memory is short-lived in the absence of antigen. Nature. 1988;336:70–73. doi: 10.1038/336070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ochsenbein AF, Pinschewer DD, Sierro S, Horvath E, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Protective long-term antibody memory by antigen-driven and T help-dependent differentiation of long-lived memory B cells to short-lived plasma cells independent of secondary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13263–13268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230417497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maruyama M, Lam KP, Rajewsky K. Memory B-cell persistence is independent of persisting immunizing antigen. Nature. 2000;407:636–642. doi: 10.1038/35036600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson SM, Hannum LG, Shlomchik MJ. Memory B cell survival and function in the absence of secreted antibody and immune complexes on follicular dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:4515–4519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, Ahmed R. Humoral immunity due to long-lived plasma cells. Immunity. 1998;8:363–372. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manz RA, Lohning M, Cassese G, Thiel A, Radbruch A. Survival of long-lived plasma cells is independent of antigen. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1703–1711. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schittek B, Rajewsky K. Maintenance of B-cell memory by long-lived cells generated from proliferating precursors. Nature. 1990;346:749–751. doi: 10.1038/346749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraal G, Weissman IL, Butcher EC. Germinal centre B cells: antigen specificity and changes in heavy chain class expression. Nature. 1982;298:377–379. doi: 10.1038/298377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacob J, Kelsoe G, Rajewsky K, Weiss U. Intraclonal generation of antibody mutants in germinal centres. Nature. 1991;354:389–392. doi: 10.1038/354389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith KG, Weiss U, Rajewsky K, Nossal GJ, Tarlinton DM. Bcl-2 increases memory B cell recruitment but does not perturb selection in germinal centers. Immunity. 1994;1:803–813. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manz RA, Thiel A, Radbruch A. Lifetime of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nature. 1997;388:133–134. doi: 10.1038/40540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraal G, Weissman IL, Butcher EC. Memory B cells express a phenotype consistent with migratory competence after secondary but not short-term primary immunization. Cell Immunol. 1988;115:78–87. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song H, Cerny J. Functional heterogeneity of marginal zone B cells revealed by their ability to generate both early antibody-forming cells and germinal centers with hypermutation and memory in response to a T-dependent antigen. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1923–1935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alugupalli KR, Leong JM, Woodland RT, Muramatsu M, Honjo T, Gerstein RM. B1b lymphocytes confer T cell-independent long-lasting immunity. Immunity. 2004;21:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldschmidt TJ, Conrad DH, Lynch RG. The expression of B cell surface receptors. I. The ontogeny and distribution of the murine B cell IgE Fc receptor. J Immunol. 1988;140:2148–2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanderson RD, Lalor P, Bernfield M. B lymphocytes express and lose syndecan at specific stages of differentiation. Cell Regul. 1989;1:27–35. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose ML, Birbeck MS, Wallis VJ, Forrester JA, Davies AJ. Peanut lectin binding properties of germinal centres of mouse lymphoid tissue. Nature. 1980;284:364–366. doi: 10.1038/284364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein U, Tu Y, Stolovitzky GA, Keller JL, Haddad J, Jr, Miljkovic V, Cattoretti G, Califano A, Dalla-Favera R. Transcriptional analysis of the B cell germinal center reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2639–2644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437996100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basso K, Liso A, Tiacci E, Benedetti R, Pulsoni A, Foa R, Di Raimondo F, Ambrosetti A, Califano A, Klein U, et al. Gene expression profiling of hairy cell leukemia reveals a phenotype related to memory B cells with altered expression of chemokine and adhesion receptors. J Exp Med. 2004;199:59–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo TC, Shaffer AL, Haddad J, Jr, Choi YS, Staudt LM, Calame K. Repression of BCL-6 is required for the formation of human memory B cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 2007;204:819–830. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHeyzer-Williams MG, Nossal GJ, Lalor PA. Molecular characterization of single memory B cells. Nature. 1991;350:502–505. doi: 10.1038/350502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosen N, Yamane T, Muijtjens M, Pham K, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Bmi-1-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-knock-in mice reveal the dynamic regulation of Bmi-1 expression in normal and leukemic hematopoietic cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1635–1644. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pin CL, Rukstalis JM, Johnson C, Konieczny SF. The bHLH transcription factor Mist1 is required to maintain exocrine pancreas cell organization and acinar cell identity. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:519–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luckey CJ, Bhattacharya D, Goldrath AW, Weissman IL, Benoist C, Mathis D. Memory T and memory B cells share a transcriptional program of self-renewal with long-term hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3304–3309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511137103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Z, Irizarry RA, Gentleman RC, Martinez-Murillo F, Spencer F. A model-based background adjustment for oligonucleotide expression arrays. J Am Stat Assoc. 2004;99:909–917. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhattacharya D, Lee DU, Sha WC. Regulation of Ig class switch recombination by NF-κB: retroviral expression of RelB in activated B cells inhibits switching to IgG1, but not to IgE. Int Immunol. 2002;14:983–991. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridderstad A, Tarlinton DM. Kinetics of establishing the memory B cell population as revealed by CD38 expression. J Immunol. 1998;160:4688–4695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horikawa K, Martin SW, Pogue SL, Silver K, Peng K, Takatsu K, Goodnow CC. Enhancement and suppression of signaling by the conserved tail of IgG memory-type B cell antigen receptors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:759–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology: The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukuda T, Yoshida T, Okada S, Hatano M, Miki T, Ishibashi K, Okabe S, Koseki H, Hirosawa S, Taniguchi M, et al. Disruption of the Bcl6 gene results in an impaired germinal center formation. J Exp Med. 1997;186:439–448. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muto A, Tashiro S, Nakajima O, Hoshino H, Takahashi S, Sakoda E, Ikebe D, Yamamoto M, Igarashi K. The transcriptional programme of antibody class switching involves the repressor Bach2. Nature. 2004;429:566–571. doi: 10.1038/nature02596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turner CA, Jr, Mack DH, Davis MM. Blimp-1, a novel zinc finger-containing protein that can drive the maturation of B lymphocytes into immunoglobulin-secreting cells. Cell. 1994;77:297–306. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shapiro-Shelef M, Lin KI, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Liao J, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Calame K. Blimp-1 is required for the formation of immunoglobulin secreting plasma cells and pre-plasma memory B cells. Immunity. 2003;19:607–620. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reimold AM, Iwakoshi NN, Manis J, Vallabhajosyula P, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Gravallese EM, Friend D, Grusby MJ, Alt F, Glimcher LH. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412:300–307. doi: 10.1038/35085509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shvarts A, Brummelkamp TR, Scheeren F, Koh E, Daley GQ, Spits H, Bernards R. A senescence rescue screen identifies BCL6 as an inhibitor of anti-proliferative p19(ARF)-p53 signaling. Genes Dev. 2002;16:681–686. doi: 10.1101/gad.929302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheeren FA, Naspetti M, Diehl S, Schotte R, Nagasawa M, Wijnands E, Gimeno R, Vyth-Dreese FA, Blom B, Spits H. STAT5 regulates the self-renewal capacity and differentiation of human memory B cells and controls Bcl-6 expression. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:303–313. doi: 10.1038/ni1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Falini B, Fizzotti M, Pucciarini A, Bigerna B, Marafioti T, Gambacorta M, Pacini R, Alunni C, Natali-Tanci L, Ugolini B, et al. A monoclonal antibody (MUM1p) detects expression of the MUM1/IRF4 protein in a subset of germinal center B cells, plasma cells, and activated T cells. Blood. 2000;95:2084–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klein U, Casola S, Cattoretti G, Shen Q, Lia M, Mo T, Ludwig T, Rajewsky K, Dalla-Favera R. Transcription factor IRF4 controls plasma cell differentiation and class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:773–782. doi: 10.1038/ni1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forster I, Rajewsky K. The bulk of the peripheral B-cell pool in mice is stable and not rapidly renewed from the bone marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4781–4784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crotty S, Felgner P, Davies H, Glidewell J, Villarreal L, Ahmed R. Cutting edge: long-term B cell memory in humans after smallpox vaccination. J Immunol. 2003;171:4969–4973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuo CT, Veselits ML, Leiden JM. LKLF: a transcriptional regulator of single-positive T cell quiescence and survival. Science. 1997;277:1986–1990. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schober SL, Kuo CT, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L, Leiden JM, Jameson SC. Expression of the transcription factor lung Kruppel-like factor is regulated by cytokines and correlates with survival of memory T cells in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;163:3662–3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith KG, Light A, O’Reilly LA, Ang SM, Strasser A, Tarlinton D. bcl-2 transgene expression inhibits apoptosis in the germinal center and reveals differences in the selection of memory B cells and bone marrow antibody-forming cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:475–484. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahashi Y, Cerasoli DM, Dal Porto JM, Shimoda M, Freund R, Fang W, Telander DG, Malvey EN, Mueller DL, Behrens TW, Kelsoe G. Relaxed negative selection in germinal centers and impaired affinity maturation in Bcl-xL transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:399–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu YJ, Joshua DE, Williams GT, Smith CA, Gordon J, MacLennan IC. Mechanism of antigen-driven selection in germinal centres. Nature. 1989;342:929–931. doi: 10.1038/342929a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galibert L, Burdin N, de Saint-Vis B, Garrone P, Van Kooten C, Banchereau J, Rousset F. CD40 and B cell antigen receptor dual triggering of resting B lymphocytes turns on a partial germinal center phenotype. J Exp Med. 1996;183:77–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhattacharya D, Logue EC, Bakkour S, DeGregori J, Sha WC. Identification of gene function by cyclical packaging rescue of retroviral cDNA libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8838–8843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132274799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sen R, Baltimore D. Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell. 1986;46:705–716. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koopman G, Reutelingsperger CP, Kuijten GA, Keehnen RM, Pals ST, van Oers MH. Annexin V for flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on B cells undergoing apoptosis. Blood. 1994;84:1415–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitchell TC, Hildeman D, Kedl RM, Teague TK, Schaefer BC, White J, Zhu Y, Kappler J, Marrack P. Immunological adjuvants promote activated T cell survival via induction of Bcl-3. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:397–402. doi: 10.1038/87692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-κB. Nature. 1995;376:167–170. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vinuesa CG, Cook MC, Cooke MP, Maclennan IC, Goodnow CC. Analysis of B cell memory formation using DNA microarrays. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;975:33–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb05939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Obukhanych TV, Nussenzweig MC. T-independent type II immune responses generate memory B cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:305–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaffer AL, Lin KI, Kuo TC, Yu X, Hurt EM, Rosenwald A, Giltnane JM, Yang L, Zhao H, Calame K, Staudt LM. Blimp-1 orchestrates plasma cell differentiation by extinguishing the mature B cell gene expression program. Immunity. 2002;17:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lemercier C, To RQ, Swanson BJ, Lyons GE, Konieczny SF. Mist1: a novel basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor exhibits a developmentally regulated expression pattern. Dev Biol. 1997;182:101–113. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johnson CL, Kowalik AS, Rajakumar N, Pin CL. Mist1 is necessary for the establishment of granule organization in serous exocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract. Mech Dev. 2004;121:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park IK, Qian D, Kiel M, Becker MW, Pihalja M, Weissman IL, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:302–305. doi: 10.1038/nature01587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lessard J, Sauvageau G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukemic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:255–260. doi: 10.1038/nature01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gallatin WM, Weissman IL, Butcher EC. A cell-surface molecule involved in organ-specific homing of lymphocytes. Nature. 1983;304:30–34. doi: 10.1038/304030a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shi GX, Harrison K, Wilson GL, Moratz C, Kehrl JH. RGS13 regulates germinal center B lymphocytes responsiveness to CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL)12 and CXCL13. J Immunol. 2002;169:2507–2515. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Butcher EC, Reichert RA, Coffman RL, Nottenburg C, Weissman IL. Surface phenotype and migratory capability of Peyer’s patch germinal center cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1982;149:765–772. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-9066-4_106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reichert RA, Gallatin WM, Weissman IL, Butcher EC. Germinal center B cells lack homing receptors necessary for normal lymphocyte recirculation. J Exp Med. 1983;157:813–827. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.3.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Quackenbush E, Xie J, Milligan J, Thornton R, Shei GJ, Card D, Keohane C, et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296:346–349. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cook DN, Prosser DM, Forster R, Zhang J, Kuklin NA, Abbondanzo SJ, Niu XD, Chen SC, Manfra DJ, Wiekowski MT, et al. CCR6 mediates dendritic cell localization, lymphocyte homeostasis, and immune responses in mucosal tissue. Immunity. 2000;12:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu YJ, Barthelemy C, de Bouteiller O, Arpin C, Durand I, Banchereau J. Memory B cells from human tonsils colonize mucosal epithelium and directly present antigen to T cells by rapid up-regulation of B7-1 and B7-2. Immunity. 1995;2:239–248. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Anderson SM, Tomayko MM, Ahuja A, Haberman AM, Shlomchik MJ. New markers for murine memory B cells that define mutated and unmutated subsets. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2103–2114. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Muramatsu M, Sankaranand VS, Anant S, Sugai M, Kinoshita K, Davidson NO, Honjo T. Specific expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a novel member of the RNA-editing deaminase family in germinal center B cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18470–18476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell. 2000;102:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shi Y, Agematsu K, Ochs HD, Sugane K. Functional analysis of human memory B-cell subpopulations: IgD+ CD27+ B cells are crucial in secondary immune response by producing high affinity IgM. Clin Immunol. 2003;108:128–137. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crouch EE, Li Z, Takizawa M, Fichtner-Feigl S, Gourzi P, Montano C, Feigenbaum L, Wilson P, Janz S, Papavasiliou FN, Casellas R. Regulation of AID expression in the immune response. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1145–1156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Protective ‘immunity’ by pre-existent neutralizing antibody titers and preactivated T cells but not by so-called ‘immunological memory’. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:310–319. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Slifka MK, Matloubian M, Ahmed R. Bone marrow is a major site of long-term antibody production after acute viral infection. J Virol. 1995;69:1895–1902. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1895-1902.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Freer G, Burkhart C, Rulicke T, Ghelardi E, Rohrer UH, Pircher H, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Role of T helper cell precursor frequency on vesicular stomatitis virus neutralizing antibody responses in a T cell receptor chain transgenic mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1410–1416. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gowans JL, Knight EJ. The route of re-circulation of lymphocytes in the rat. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1964;159:257–282. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1964.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Butcher EC, Scollay RG, Weissman IL. Organ specificity of lymphocyte migration: mediation by highly selective lymphocyte interaction with organ-specific determinants on high endothelial venules. Eur J Immunol. 1980;10:556–561. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830100713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pape KA, Catron DM, Itano AA, Jenkins MK. The humoral immune response is initiated in lymph nodes by B cells that acquire soluble antigen directly in the follicles. Immunity. 2007;26:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Waisman A, Kraus M, Seagal J, Ghosh S, Melamed D, Song J, Sasaki Y, Classen S, Lutz C, Brombacher F, Nitschke L, Rajewsky K. IgG1 B cell receptor signaling is inhibited by CD22 and promotes the development of B cells whose survival is less dependent on Igα/β. J Exp Med. 2007;204:747–758. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–2202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O’Reilly LA, Harris AW, Tarlinton DM, Corcoran LM, Strasser A. Expression of a bcl-2 transgene reduces proliferation and slows turnover of developing B lymphocytes in vivo. J Immunol. 1997;159:2301–2311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pape KA, Kouskoff V, Nemazee D, Tang HL, Cyster JG, Tze LE, Hippen KL, Behrens TW, Jenkins MK. Visualization of the genesis and fate of isotype-switched B cells during a primary immune response. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1677–1687. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu YJ, Oldfield S, MacLennan IC. Memory B cells in T cell-dependent antibody responses colonize the splenic marginal zones. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:355–362. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roederer M. Spectral compensation for flow cytometry: visualization artifacts, limitations, and caveats. Cytometry. 2001;45:194–205. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20011101)45:3<194::aid-cyto1163>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.