The patterns of care and clinical outcomes of metastatic breast cancer patients receiving first-line trastuzumab-based therapy after previous trastuzumab therapy were evaluated. Trastuzumab-based therapy was an effective first-line treatment for patients with relapse after previous trastuzumab therapy. Various factors, such as trastuzumab-free interval, type of first site of disease relapse, and hormone receptor status, should be considered in the choice of the best first-line treatment option for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients.

Keywords: Retreatment, Metastatic breast cancer, HER2+, Neoadjuvant/adjuvant trastuzumab, Trastuzumab-free interval

Abstract

Background.

We evaluated the patterns of care and clinical outcomes of metastatic breast cancer patients treated with first-line trastuzumab-based therapy after previous (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab.

Materials and Methods.

A total of 416 consecutive, HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients who had received first-line trastuzumab-based therapy were identified at 14 Italian centers. A total of 113 patients had presented with de novo stage IV disease and were analyzed separately. Dichotomous clinical outcomes were analyzed using logistic regression and time-to-event outcomes using Cox proportional hazards models.

Results.

In the 202 trastuzumab-naïve patients and 101 patients with previous trastuzumab exposure, we observed the following outcomes, respectively: overall response rate, 69.9% versus 61.3% (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.62; p = .131), clinical benefit rate, 79.1% versus 72.5% (adjusted OR, 0.73; p = .370), median progression-free survival (PFS), 16.1 months versus 12.0 months (adjusted hazards ratio [HR], 1.33; p = .045), and median overall survival (OS), 52.2 months versus 48.2 months (adjusted HR, 1.18; p = .404). Patients with a trastuzumab-free interval (TFI) <6 months, visceral involvement, and hormone receptor-negative disease showed a worse OS compared with patients with a TFI of ≥6 months (29.5 vs. 48.3 months; p = .331), nonvisceral involvement (48.0 vs. 60.3 months; p = .270), and hormone receptor-positive disease (39.8 vs. 58.6 months; p = .003), respectively.

Conclusion.

Despite the inferior median PFS, trastuzumab-based therapy was an effective first-line treatment for patients relapsing after (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab. Previous trastuzumab exposure and the respective TFI, type of first site of disease relapse, and hormone receptor status should be considered in the choice of the best first-line treatment option for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients.

Implications for Practice:

A paucity of data is available outlining the clinical outcomes of patients who receive trastuzumab as a part of their (neo)adjuvant treatment and then resume trastuzumab-based therapy in the metastatic setting. In the present study, despite an inferior median progression-free survival, trastuzumab-based therapy was shown to be an effective first-line treatment for patients relapsing after (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab. Previous trastuzumab exposure, the respective trastuzumab-free interval, the type of first site of disease relapse, and hormone receptor status should be considered in choosing the best first-line treatment option for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients.

Introduction

Trastuzumab is a milestone for the systemic therapy of HER2-positive breast cancer. According to international guidelines, most patients diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer are candidates to receive (neo)adjuvant treatment with the combination of chemotherapy and trastuzumab [1–3]. The introduction of trastuzumab in the early setting shifted the prognosis of HER2-positive tumors such that the survival outcomes have been similar between women with HER2-positive disease receiving trastuzumab and those with HER2-negative disease [4]. However, approximately 5%–25% of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer who received (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab will develop recurrent disease [5]. As recently shown in a joint analysis of two large North American randomized trials in early-stage high-risk breast cancer patients, despite the disease-free survival improvement associated with the introduction of adjuvant trastuzumab, nearly 25% of women still developed a relapse [6]. Outside clinical trials, the percentage of patients who develop recurrent disease is approximately 17% in women with node-positive disease at diagnosis and less than 3% in those without nodal involvement [7].

Currently, most patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer have been treated with previous (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab and are candidates to undergo first-line treatment with anti-HER2 agents. Despite several trials that have evaluated the role of trastuzumab and other anti-HER2 agents (e.g., lapatinib, pertuzumab, trastuzumab emtansine [T-DM1]) as first-line treatment, a paucity of data is available outlining the clinical outcomes of patients who received trastuzumab as a part of their (neo)adjuvant treatment and then resumed trastuzumab-based therapy in the metastatic setting [5].

The present study evaluated the patterns of care and clinical outcomes of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer patients treated with first-line trastuzumab-based regimens and assessed the impact on these outcomes of previous exposure to trastuzumab in the early setting (adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection

The present study was a retrospective cohort study conducted at 14 Italian centers affiliated with the Gruppo Italiano Mammella (Italian Breast Cancer Study Group) that evaluated the patterns of care and clinical outcomes of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients treated with first-line trastuzumab-based therapy after previous (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab treatment.

Consecutive patients diagnosed with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer from January 2000 to December 2013 and treated with at least one infusion of anti-HER2 single-agent trastuzumab as first-line therapy were eligible for the present study. We excluded patients with HER2-negative disease, those without treatment with anti-HER2 agents in the first-line setting, and those who had received first-line treatment with an anti-HER2 agent other than trastuzumab (i.e., lapatinib, pertuzumab, TDM1, neratinib) or a combination of anti-HER2 agents (i.e., trastuzumab plus lapatinib, trastuzumab plus pertuzumab, pertuzumab plus T-DM1) or a combination of other targeted agents (i.e., trastuzumab plus bevacizumab, trastuzumab plus everolimus). Furthermore, patients who developed locoregional relapse and/or oligometastatic disease who had undergone radical treatment (surgery followed or not by radiotherapy and/or systemic therapies) and were afterward considered disease free were not eligible for the present study.

Previous exposure to (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab was the criteria used to distinguish between two cohorts of patients: cohort A (patients with no previous treatment with [neo]adjuvant trastuzumab) and cohort B (patients previously treated with [neo]adjuvant trastuzumab).

Treatment and Study Procedures

For all eligible patients, their medical records were retrieved and anonymized data entered into a database. The following information was retrieved: demographic, clinical, pathologic and molecular features, (neo)adjuvant therapies received (chemotherapy, endocrine treatment, targeted agents, radiotherapy), sites and number of organs involved at the diagnosis of recurrent disease, details of first-line and subsequent lines of treatment for metastatic disease (drugs received, best response and its duration, date of progression, brain as the site of disease progression), and date of death or last follow-up examination.

For patients who developed relapse in more than one organ, the first site of distant metastasis was defined by prespecified importance in the following order: brain, liver, lung, bone, and other. The category “other” included skin, lymph node, soft tissue, pleura, and other rarer sites of relapse. Patients with bone, skin, lymph node, and soft tissue lesions were considered to have nonvisceral disease; all other patients were considered to have visceral disease.

HER2 and hormone receptor assessments were performed by the pathologists of the participating centers. Positivity of estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status was defined as immunostaining in ≥1% of invasive tumor cells. HER2 was considered positive when the staining intensity was graded 3+ by immunohistochemistry or 2+ with gene amplification using fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis. The primary tumors were staged according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria [8]. Patients were followed according to the practice guidelines in place at the time.

The institutional review boards of participating centers approved the study protocol and the retrospective review of the patients’ medical records for the present study.

Objectives and Endpoint Assessment

The primary objectives of the present analysis were to evaluate the activity and effectiveness of first-line trastuzumab-based therapy in the two cohorts of patients. The primary endpoints were the objective response rate (ORR), clinical benefit rate (CBR), progression-free survival (PFS) to first-line treatment, and overall survival (OS). Patients with the following characteristics were considered not evaluable for the treatment response and were thus excluded from the response analyses: lack of response data, nonmeasurable disease (isolated metastasis to bone, pleura, or skin only), radiotherapy before or during first-line medical treatment, and brain metastases as the only site of relapse treated with whole-brain radiotherapy or surgery. As secondary objectives, we also assessed whether the time interval from the end of (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab to the start of metastatic treatment (trastuzumab-free interval [TFI]) influenced OS. The TFI was divided into two categories: relapse during or within 6 months from the end of (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab and relapse ≥6 months after such therapy. The 6-month cutoff point was based on the observation that most phase III trials that included HER2-positive patients treated in the first-line setting had used this time point as a criterion for patient eligibility. In addition, we evaluated whether the first site of distant metastatic disease, defined as nonvisceral or visceral, influenced OS. We further evaluated the pattern of disease relapse and OS of patients according to hormone receptor status. Finally, we deepened these secondary analyses by stratifying them by previous treatment with (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab. Patients with de novo stage IV disease were not included in the main analyses; all the specified analyses were then repeated to include this group of patients.

Other Definitions

The treatment response was assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.0 [9]. ORR was defined as a complete or partial response, and CBR as a complete or partial response or stable disease for at least 6 months. PFS was computed as the difference between the date of documented progression or death and the date of diagnosis of metastatic disease. OS was defined as the difference between the date of death from any cause and the diagnosis of metastatic disease.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed using Pearson’s chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using logistic regression. Cumulative survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and univariate analysis of differences between survival rates was performed to test for significance using the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis for survival was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Departures from the proportional hazards assumption were assessed based on the Schoenfeld residuals. All tests were two-sided, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p < .05 was considered significant. All data were analyzed using Stata, version 12.3 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, http://www.stata.com).

Results

A total of 416 consecutive HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients treated at 14 Italian centers over 13 years were identified (supplemental online Fig. 1). Of these 416 patients, 113 presented with de novo stage IV disease and were analyzed separately. Thus, for the main analysis, 303 patients were included, of whom 202 were trastuzumab-naïve (cohort A) and 101 had had previous trastuzumab exposure (cohort B).

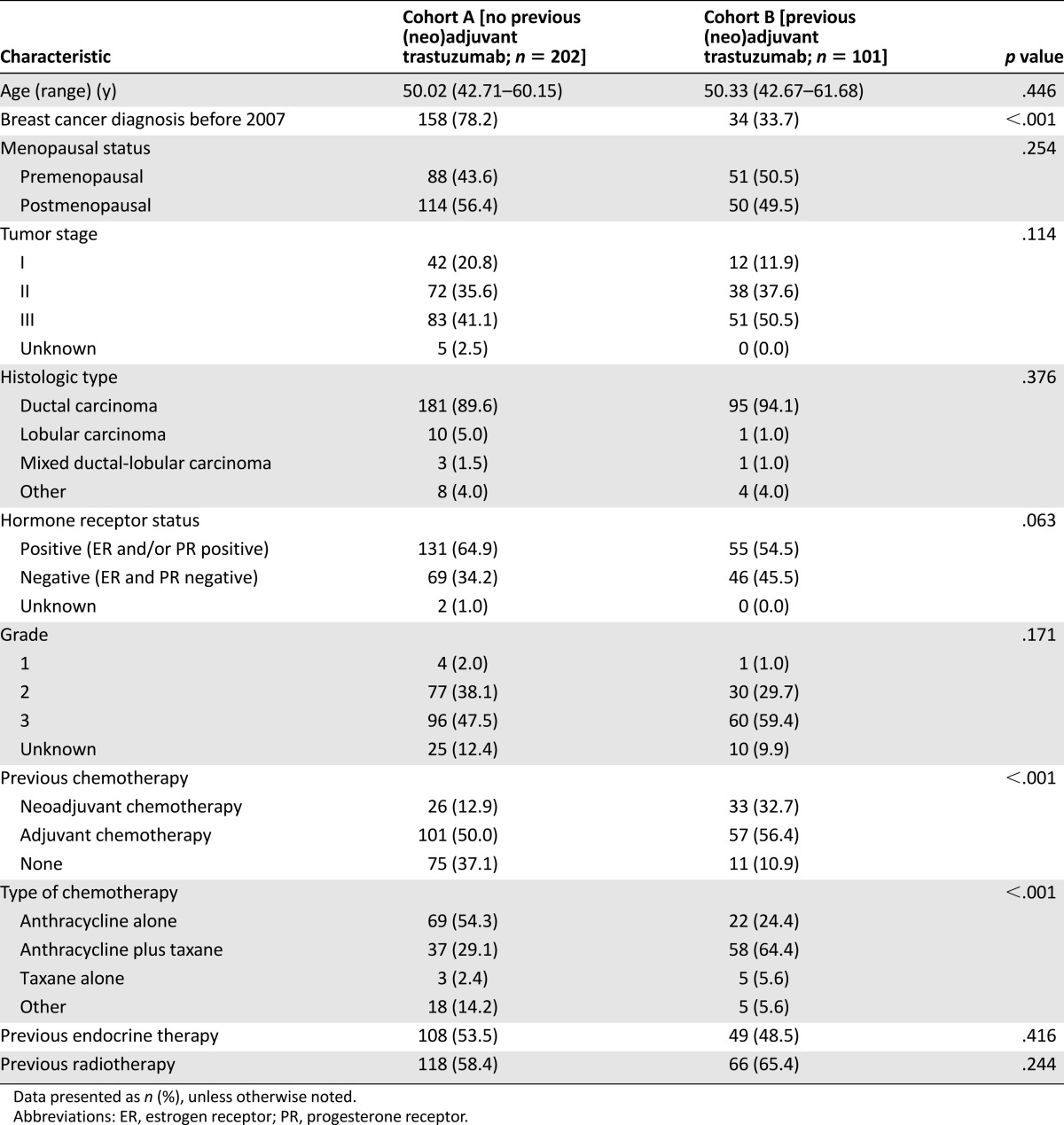

Most of the patient and tumor baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 cohorts (Table 1). In cohort A, 64.9% of the patients had coexpression of hormone receptors compared with 54.5% in cohort B. As expected, more patients in cohort A had been diagnosed with breast cancer before 2007 (the year in which adjuvant trastuzumab became widely available in Italy) compared with patients in cohort B. The patients in cohort B had been more commonly treated with chemotherapy, mostly in the neoadjuvant setting and using an anthracycline- and taxane-based regimen. The baseline characteristics of the patients who presented with de novo stage IV disease have been reported separately in supplemental online Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at breast cancer diagnosis

Patterns of Care of First-Line Treatment

At the present analysis, the median follow-up time from the diagnosis of metastatic disease was 2.59 years (interquartile range [IQR], 1.55–4.38) overall. Of the 149 patients who were still alive at the last follow-up visit, the median follow-up time was 2.75 years (IQR, 1.61–5.15). The median interval from the time of the diagnosis of metastatic disease and the initiation of first-line trastuzumab-based therapy was 0.84 month (IQR, 0.33–1.57) in cohort A and 0.92 month (IQR, 0.33–1.57) in cohort B (p = .946).

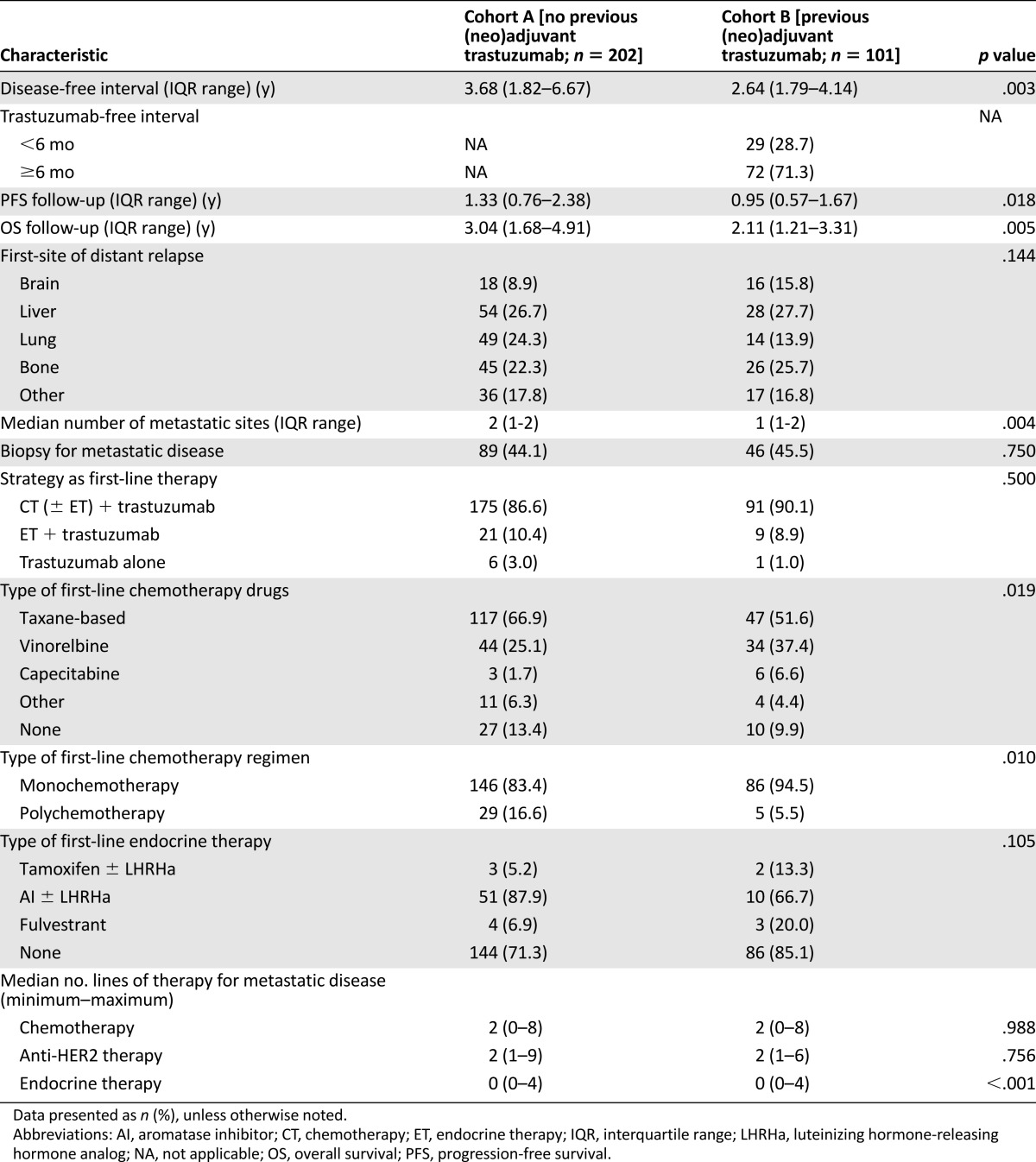

Overall, no significant difference in the site of first metastasis was observed between the two cohorts (Table 2). Patients with hormone receptor-positive disease showed a trend toward a lower incidence of visceral involvement (66.1% vs. 73.9%; p = .156) and brain metastases (9.1% vs. 14.8%; p = .133) but presented with a higher incidence of bone metastases (26.9% vs. 18.3%; p = .087; supplemental online Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics at diagnosis of recurrent disease and patterns of care to first-line treatment

A total of 135 patients (44.6%) had a biopsy of 1 metastatic site at the time of disease relapse. In 17 patients (12.6%), the hormone receptor status was discordant: 14 patients had hormone receptor-positive breast cancer at diagnosis and hormone receptor-negative at relapse, and 3 patients had early-stage hormone receptor-negative breast cancer and receptor-positive metastatic disease. The HER2 status was discordant in 17 patients (12.6%), changing from negative at the time of diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer to positive at the time of relapse.

When comparing the type of combination therapy, no significant differences were found between the two cohorts: most patients (n = 266; 87.8%) received trastuzumab combined with chemotherapy. In cohort B, more patients received single-agent first-line chemotherapy than in cohort A. Vinorelbine was more commonly used in cohort B, and more patients in cohort A received taxane-based chemotherapy. Patients in both cohorts received a median number of 2 chemotherapy lines (range, 0–8), 2 anti-HER2 therapy lines (range, 1–9), and 0 endocrine therapy lines (range, 0–4). The characteristics of the patients with de novo stage IV disease and their patterns of care of first-line treatment are reported in supplemental online Table 3.

Activity of First-Line Trastuzumab-Based Therapy

Of the 303 patients included in the main analysis, 243 (80.2%) were evaluable for the treatment response (supplemental online Fig. 1). As reported in supplemental online Table 4, patients in cohort A showed a trend toward a higher ORR (69.9% vs. 61.3%) compared with patients in cohort B. After controlling for age, disease-free interval, menopausal status, baseline tumor characteristics, and center size, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) was 0.62 (95% CI, 0.34–1.15; p = .131). No significant difference in CBR was observed (79.1% in cohort A vs. 72.5% in cohort B), with an adjusted OR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.37–1.46; p = .370).

The same analyses were repeated, including the 113 patients who presented with de novo stage IV disease in cohort A (supplemental online Table 5). Similar results were observed (ORR: adjusted OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.34–1.10; p = .104; CBR: adjusted OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.41–1.49; p = .455).

Effectiveness of First-Line Trastuzumab

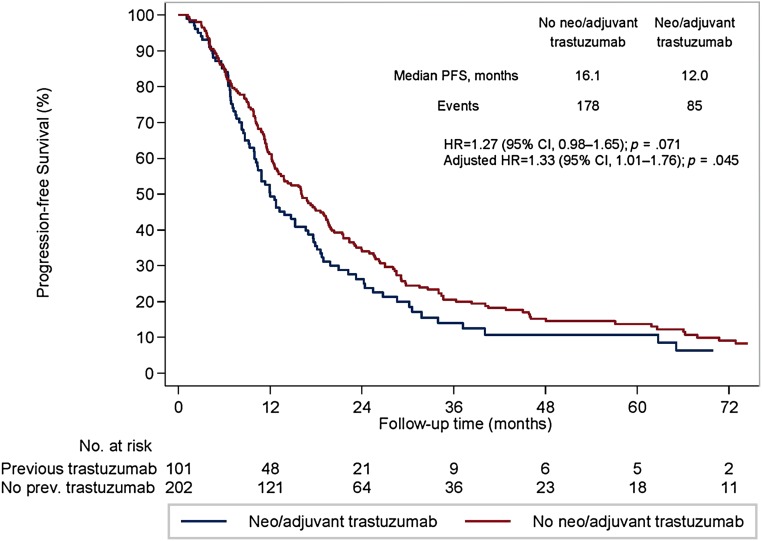

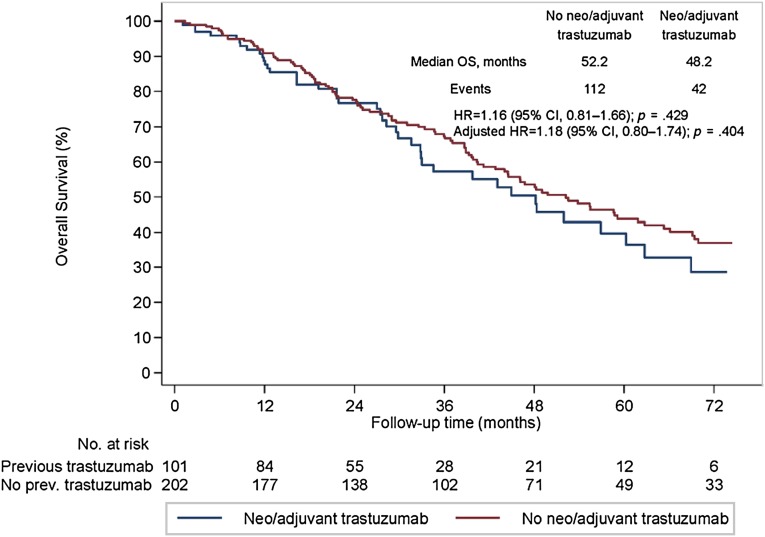

All 303 eligible patients were included in the survival analyses. The median PFS to first-line trastuzumab-based therapy was 16.1 months in cohort A and 12.0 months in cohort B (univariate hazard ratio [HR], 1.27; 95% CI, 0.98–1.65; p = .071; Fig. 1). A significant difference between the 2 cohorts was observed at the multivariate analysis (adjusted HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.01–1.76; p = .045). No difference was observed between the 2 cohorts in terms of OS (median OS, 52.2 months in cohort A and 48.2 months in cohort B; univariate HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.81–1.66; p = .429; Fig. 2). Likewise, no significant difference was noted after controlling for relevant clinical and pathological variables (adjusted HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.80–1.74; p = .404).

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival after a metastatic diagnosis in patients undergoing first-line trastuzumab-based therapy.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PFS, progression-free survival; prev, previous.

Figure 2.

Overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer undergoing first-line trastuzumab-based therapy.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

Similar results were obtained when the analyses were repeated to include the patients who had presented with de novo stage IV disease. The adjusted HR for PFS was 1.32 (95% CI, 1.01–1.73; p = .041) and the adjusted HR for OS was 1.19 (95% CI, 0.82–1.74; p = .355).

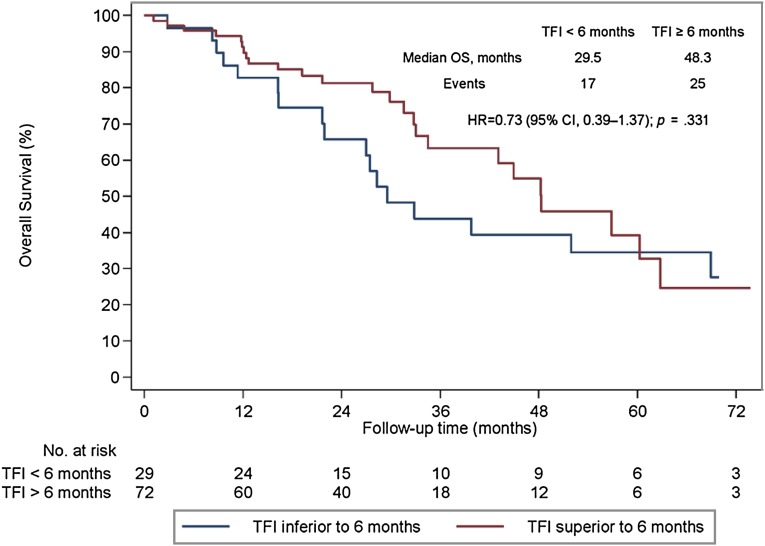

Secondary Analyses

We analyzed the prognostic effect of TFI, type of first metastatic site, and hormone receptor status. For the TFI, 29 patients (28.7%) developed a relapse during or within 6 months from the end of (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab and 72 (71.3%) after 6 months. A trend for prognostic significance of TFI was found. Patients with a TFI of <6 months had a median OS of 29.5 months and those with a TFI of >6 months had a median OS of 48.3 months (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.39–1.37; p = .331; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer undergoing first-line trastuzumab-based therapy stratified by trastuzumab-free interval (<6 months vs. ≥6 months).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; TFI, trastuzumab-free interval.

Type of First Metastatic Site

Patients with visceral disease at relapse showed a trend toward a shorter median OS (48.0 months) than did patients with nonvisceral lesions (60.3 months; p = .270). When restricting the analysis to patients with visceral involvement, previous trastuzumab exposure seemed to impair OS (33.0 months vs. 52.2 months in cohort A; p = .056; supplemental online Fig. 2). No effect was shown for patients who presented with nonvisceral metastases (median OS of 49.8 months vs. 68.9 months for patients in cohort B; p = .246; supplemental online Fig. 2).

A total of 34 patients (11.2%) had brain metastases at the time of disease relapse. These patients had the worst median OS (28.5 months; IQR, 13.5–44.0). At the time of disease progression to first-line treatment, 36 more patients (23.1%) had developed brain metastases.

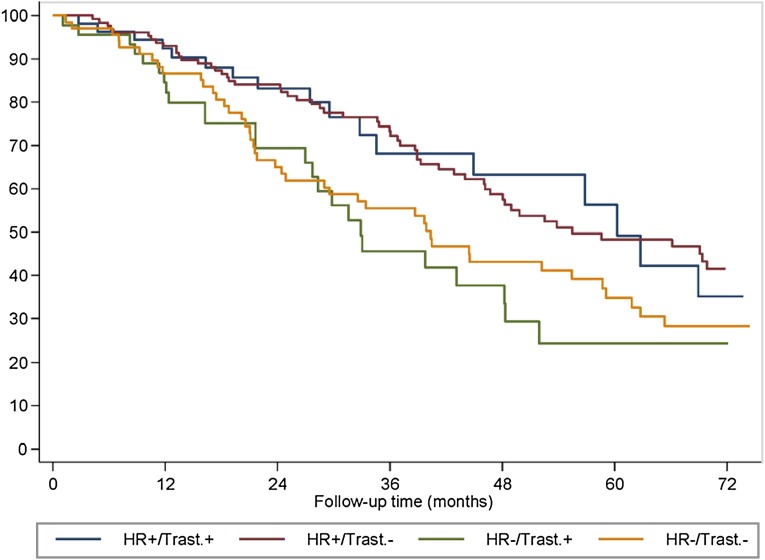

Hormone Receptor Status

Patients with hormone receptor-positive disease had statistically significant better OS than did patients with hormone receptor-negative tumors (58.6 months vs. 39.8 months; p = .003). No effect of previous exposure to (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab was found according to hormone receptor status (Fig. 4). Patients with hormone receptor-negative disease had a median OS of 40.3 months in cohort A and 32.9 months in cohort B (p = .590). Those with hormone receptor-positive tumors presented with a median OS of 55.5 months in cohort A and 60.3 months in cohort B (p = .997).

Figure 4.

Overall survival (OS) by hormone receptor status (positive vs. negative) and previous trastuzumab exposure in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer undergoing first-line trastuzumab-based therapy.

Abbreviations: HR+/Trast.+, patients with hormone receptor positive disease and previous trastuzumab exposure; HR+/Trast.−, patients with hormone receptor positive disease and without previous trastuzumab exposure; HR−/Trast.+, patients with hormone receptor-negative disease and previous trastuzumab exposure; HR−/Trast.−, patients with hormone receptor-negative disease and without previous trastuzumab exposure.

Discussion

Our study, aiming to evaluate the benefits of trastuzumab retreatment, presents the largest cohort of patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer treated with first-line trastuzumab-based therapy after previous exposure to the same biologic agent in the (neo)adjuvant setting. Compared with trastuzumab-naïve patients, those with previous exposure to trastuzumab had a statistically significantly worse median PFS (12.0 months vs. 16.1 months) and a trend toward a worse ORR (61.3% vs. 69.9%) but no significant difference in terms of CBR (79.1% vs. 72.5%) and OS (52.2 months vs. 48.2 months). Patients with a TFI of <6 months, visceral involvement, and hormone receptor-negative disease had worse OS than did patients with a TFI of ≥6 months (29.5 vs. 48.3 months), nonvisceral involvement (48.0 vs. 60.3 months), and hormone receptor-positive disease (39.8 vs. 58.6 months), respectively.

To date, a paucity of data is available on the clinical outcomes of patients previously treated in the (neo)adjuvant setting with trastuzumab who then develop recurrence and receive trastuzumab-based regimens as first-line treatment (Table 3) [10–14]. We have confirmed that disease recurrence after the use of trastuzumab in the early setting is associated with a lower likelihood of prolonged PFS to first-line trastuzumab-based regimen in the metastatic setting [15]. In the Clinical Evaluation of Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab (CLEOPATRA) study, patients with previous trastuzumab exposure derived similar benefits from first-line therapy with docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab as did trastuzumab-naïve patients. However, women with no previous trastuzumab exposure had a longer PFS in both the control (10.4 months vs. 12.4 months) and the experimental (16.9 months vs. 18.5 months) arms [10].

Table 3.

Retreatment with trastuzumab in the first-line setting in patients relapsing after (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab-based therapy

Nevertheless, trastuzumab-based therapy can be considered an effective first-line therapy also for patients exposed to (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab, because no difference in OS has been reported in the available studies. Murthy et al. showed that patients who did not receive previous trastuzumab had better median OS (36 months vs. 28 months) than those previously exposed to trastuzumab [13]. However, the result was nonsignificant after controlling for relevant clinical and pathological variables [13]. More recently, Negri et al. showed a similar 2-year OS in trastuzumab-naïve patients compared with those with previous exposure (59.5% vs. 60.0%) [14].

Although Murthy et al. reported a significantly better CBR in patients without previous exposure to trastuzumab (71% vs. 39%) [13], we could not find any difference. In our study, patients previously exposed to (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab showed a CBR of 72.5%. Similar results were reported in the Retreatment After Herceptin Adjuvant (RHEA) study (CBR in patients previously treated with trastuzumab, 70.7%) [11] and in the study by Krell et al. (CBR, 73.3%) [12].

Thanks to the development of newer therapies targeting HER2 and their availability in the clinical practice, the life expectancy of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer patients has increased significantly [16]. For this reason, the selection and sequencing of HER2-targeted treatments has acquired an increasing importance and has become more challenging for medical oncologists. According to the current available evidence, previous trastuzumab exposure should be considered in the choice of the best first-line treatment option. The European School of Oncology-European Society for Medical Oncology international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer recommends further anti-HER2 therapy, if not contraindicated, in all patients, including those with relapse after adjuvant trastuzumab [17, 18]. The relapse-free interval and the country-specific availability of drugs should be considered key factors in the choice of the anti-HER2 agent to use in the first-line setting [17, 18]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend the use of first-line taxane, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab in patients with recurrence more than 12 months after the completion of (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab, and T-DM1 should be used in patients with recurrence during (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab therapy or within 6 months of its completion (in accordance with the EMILIA study inclusion criteria) [19]. Nevertheless, the guidelines further extrapolate the indication for TDM-1 use in those patients relapsing within 12 months of (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab completion. To date, no data are available to guide the choice of the best first-line therapy in patients with a TFI between 6 and 12 months. In our study, the 6-month cutoff of TFI seemed to have an important prognostic effect; however, this result was not statistically significant, probably because of the low number of patients and events in the analysis and therefore requires further evaluation.

The type of metastatic involvement and hormone receptor status might be considered two other important factors to be considered in the choice of the best first-line treatment option. As recently shown in the registHER study, a large multicenter, prospective cohort study in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, both nonvisceral metastases (in particular, node and local sites) and hormone receptor positivity are factors associated with long-term survival [20].

In our study, irrespective of previous trastuzumab exposure, patients with visceral involvement showed a shorter OS (48.0 months) than did patients with nonvisceral lesions (60.3 months). In the study by Murthy et al., the median OS ranged from 17 to 32 months in patients with visceral metastases and from 46 to 87 months in patients with nonvisceral lesions [13]. In the CLEOPATRA study, patients with nonvisceral disease seemed to be the only subgroup who did not derive any benefit from the addition of pertuzumab to a trastuzumab-based therapy in both PFS (HR, 0.96) [10] and OS (HR, 1.11) [16]. Similarly, in the EMILIA trial, no additional benefit in PFS was shown with the use of T-DM1 in patients with nonvisceral involvement (HR, 0.96) [21]. In contrast, T-DM1 also added a substantial PFS benefit in these patients when used in more advanced lines (HR, 0.41) [22].

Among visceral metastases, HER2-positive disease is a known risk factor for the development of brain lesions [23, 24]. In our study, a total of 34 patients (11.2%) presented with brain lesions as the first site of disease relapse and 70 patients (23.1%) had brain metastases at the time of progression to first-line therapy. Higher percentages were reported by the registHER study, with 19.9% and 57.6% of patients with brain lesions at diagnosis and at the first disease progression, respectively [25]. Patients with brain metastases as the first site of relapse showed the worst OS in both our study (28.5 months) and the study by Murthy et al. (17 months); intermediate OS data were shown in the registHER study (20.3 months) [25].

Hormone receptor-positive (luminal B, HER2-positive) and hormone receptor-negative (HER2-positive, nonluminal) subgroups define two distinct biologic subsets within the group of HER2-positive tumors with different patterns of recurrence and survival [26]. Patients with HER2-positive, nonluminal tumors are less likely to experience a first recurrence in bone and more likely to develop recurrence in the brain and have a significantly increased hazard of early death [27]. Similar findings were shown in our study; patients with nonluminal HER2-positive tumors showed a greater incidence of visceral and brain lesions and a worse median OS (39.8 months) compared with patients with luminal B, HER2-positive disease, who had a higher incidence of bone metastases and a better median OS (58.6 months). Hormone receptor status, irrespective of previous exposure to (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab, might have potential therapeutic implications in the choice of the best first-line treatment. The combination of endocrine therapy and trastuzumab or lapatinib is today an available first-line therapeutic option in patients with luminal B, HER2-positive metastatic tumors [5]. In our study, approximately 10% of patients were treated with first-line trastuzumab and endocrine therapy; this approach has been used in a similar proportion of patients (9.8%) in the registHER study [28].

To interpret the plausibility of our findings, some limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective design made the study prone to bias and confounding. The patients were treated over a relatively long period of time in different institutions and with different first-line trastuzumab-based approaches and regimens. Also, despite the availability of adjuvant trastuzumab since 2007, the patient population was relatively small. The two cohorts differed in some patient and tumor characteristics at both baseline and the time of diagnosis of metastatic disease. The first site of distant metastasis for patients who presented with multiple sites was classified into one group based on an arbitrary prespecified order of importance. Some outcomes were not universally assessed (e.g., for 60 patients, the response was not evaluable). However, despite these limitations, the study has some important strengths. It is the study with the largest cohort of patients treated with first-line trastuzumab-based therapy after previous exposure with the same biologic agent in the (neo)adjuvant setting. It was a multicenter study performed at three centers with longstanding experience in the treatment of breast cancer and at smaller institutions; hence, the study results can give a point estimate for expected benefit from anti-HER2 therapies in the metastatic setting in common clinical practice. Furthermore, the results in terms of ORR, CBR, and PFS are in line with those available in the published data, demonstrating the accuracy of the collected data and that patients were treated according to standard guidelines. Moreover, the favorable results in terms of median OS reflect the high quality of care provided to patients in a common clinical practice setting.

Conclusion

In our study, we observed that trastuzumab-based therapy is an effective first-line therapy for patients exposed to (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab. However, trastuzumab-naïve patients showed a better PFS and a trend toward a better response rate to first-line trastuzumab-based therapy than did patients with previous exposure to (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab. Furthermore, the TFI, type of metastatic involvement, and hormone receptor status should be considered relevant prognostic indicators for the choice of the best first-line treatment option. The results of the MARIANNE [29] and PERUSE [30] trials are awaited for a better understanding of the impact of previous trastuzumab exposure on the clinical outcomes of first-line therapy and to expand the options available for the first-line treatment of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. The incorporation of tissue-based correlatives studies into prospective trial design are needed for a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms causing sensitivity and resistance to targeted therapies to optimize the use of anti-HER2 agents and to allow a more personalized approach to the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following investigators who contributed to the study: Paolo Pronzato, Simona Pastorino, and Claudia Bighin, Department of Medical Oncology, U.O. Oncologia Medica 2, IRCCS AOU San Martino-IST, Genova, Italy; Chiara Dellepiane and Mario Roberto Sertoli, Department of Medical Oncology, Clinica di Oncologia Medica, IRCCS AOU San Martino-IST, Genova, Italy; Alfredo Falcone, Ilaria Bertolini, and Sara Fancelli, UO Oncologia 2 Universitaria, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana, Istituto Toscano Tumori, Pisa, Italy; Elena Collova’ and Antonella Ferzi, UO Oncologia Medica, AO Ospedale Civile di Legnano, Legnano, Italy; Pasqua Cito and Simona Vallarelli, U.O. Oncologia Medica-Policlinico, Bari, Italy; Federico Cappuzzo, Department of Medical Oncology, Istituto Tumori Toscano, Civil Hospital of Livorno, Livorno, Italy; Paolo Pedrazzoli, Medical Oncology, IRCCS San Matteo University Hospital Foundation, Pavia, Italy; Giuseppe Naso, Department of Radiology, Oncology and Human Pathology, Oncology Unit B, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy; Paolo Marchetti, Oncology Unit, Sant’Andrea Hospital, “Sapienza” University of Rome, Rome, Italy; Maria Giuseppa Sarobba, Medical Oncology, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Sassari, Sassari, Italy; Marco Benasso and Tiziana Catzeddu, Medical Oncology, Ospedale San Paolo, Savona, Italy; Antonio Pazzola, Medical Oncology, Ospedale Santissima Annunziata, Sassari, Italy; and Federico Sottotetti, Medical Oncology, IRCCS Fondazione Maugeri, Pavia, Italy.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Matteo Lambertini, Lucia Del Mastro

Provision of study material or patients: Matteo Lambertini, Francesca Poggio, Fabio Puglisi, Antonio Bernardo, Filippo Montemurro, Elena Poletto, Emma Pozzi, Valentina Rossi, Emanuela Risi, Antonella Lai, Elisa Zanardi, Valentina Sini, Serena Ziliani, Gabriele Minuti, Silvia Mura, Donatella Grasso, Andrea Fontana, Lucia Del Mastro

Collection and/or assembly of data: Matteo Lambertini, Arlindo R. Ferreira, Francesca Poggio, Elena Poletto, Emma Pozzi, Valentina Rossi, Emanuela Risi, Antonella Lai, Elisa Zanardi, Valentina Sini, Serena Ziliani, Gabriele Minuti, Silvia Mura, Donatella Grasso, Andrea Fontana

Data analysis and interpretation: Matteo Lambertini, Arlindo R. Ferreira, Filippo Montemurro, Lucia Del Mastro

Manuscript writing: Matteo Lambertini, Arlindo R. Ferreira, Francesca Poggio, Fabio Puglisi, Antonio Bernardo, Filippo Montemurro, Elena Poletto, Emma Pozzi, Valentina Rossi, Emanuela Risi, Antonella Lai, Elisa Zanardi, Valentina Sini, Serena Ziliani, Gabriele Minuti, Silvia Mura, Donatella Grasso, Andrea Fontana, Lucia Del Mastro

Final approval of manuscript: Matteo Lambertini, Arlindo R. Ferreira, Francesca Poggio, Fabio Puglisi, Antonio Bernardo, Filippo Montemurro, Elena Poletto, Emma Pozzi, Valentina Rossi, Emanuela Risi, Antonella Lai, Elisa Zanardi, Valentina Sini, Serena Ziliani, Gabriele Minuti, Silvia Mura, Donatella Grasso, Andrea Fontana, Lucia Del Mastro

Disclosures

Fabio Puglisi: Roche (C/A); Filippo Montemurro: Hoffmann-La Roche, AstraZeneca (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi7–vi23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, et al. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: Highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2206–2223. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Breast Cancer - breast.pdf. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/breast.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- 4.Musolino A, Ciccolallo L, Panebianco M, et al. Multifactorial central nervous system recurrence susceptibility in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer: Epidemiological and clinical data from a population-based cancer registry study. Cancer. 2011;117:1837–1846. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Mastro L, Lambertini M, Bighin C, et al. Trastuzumab as first-line therapy in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12:1391–1405. doi: 10.1586/era.12.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: Planned joint analysis of overall survival from NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3744–3752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vici P, Pizzuti L, Natoli C, et al. Outcomes of HER2-positive early breast cancer patients in the pre-trastuzumab and trastuzumab eras: A real-world multicenter observational analysis. The RETROHER study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147:599–607. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3133-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer Staging Manual AJCC. Available at http://www.springer.com/medicine/surgery/book/978-0-387-88440-0. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- 9.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baselga J, Cortés J, Kim S-B, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109–119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Láng I, Bell R, Feng FY, et al. Trastuzumab retreatment after relapse on adjuvant trastuzumab therapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: Final results of the Retreatment after HErceptin Adjuvant trial. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2014;26:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krell J, James CR, Shah D, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer relapsing post-adjuvant trastuzumab: Pattern of recurrence, treatment and outcome. Clin Breast Cancer. 2011;11:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murthy RK, Varma A, Mishra P, et al. Effect of adjuvant/neoadjuvant trastuzumab on clinical outcomes in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1932–1938. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Negri E, Zambelli A, Franchi M, et al. Effectiveness of trastuzumab in first-line HER2+ metastatic breast cancer after failure in adjuvant setting: A controlled cohort study. The Oncologist. 2014;19:1209–1215. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaz-Luis I, Seah D, Olson EM, et al. Clinicopathological features among patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor-2-positive breast cancer with prolonged clinical benefit to first-line trastuzumab-based therapy: A retrospective cohort study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2013;13:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim S-B, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:724–734. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L, et al. ESO-ESMO 2nd international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC2)†. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1871–1888. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L, et al. ESO-ESMO 2nd international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC2) Breast. 2014;23:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giordano SH, Temin S, Kirshner JJ, et al. Systemic therapy for patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2078–2099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yardley DA, Tripathy D, Brufsky AM, et al. Long-term survivor characteristics in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer from registHER. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2756–2764. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1783–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krop IE, Kim S-B, González-Martín A, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine versus treatment of physician’s choice for pretreated HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (TH3RESA): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:689–699. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabos Z, Sinha R, Hanson J, et al. Prognostic significance of human epidermal growth factor receptor positivity for the development of brain metastasis after newly diagnosed breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5658–5663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyland-Jones B. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer and central nervous system metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5278–5286. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brufsky AM, Mayer M, Rugo HS, et al. Central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: Incidence, treatment, and survival in patients from registHER. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4834–4843. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alqaisi A, Chen L, Romond E, et al. Impact of estrogen receptor (ER) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) co-expression on breast cancer disease characteristics: Implications for tumor biology and research. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148:437–444. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaz-Luis I, Ottesen RA, Hughes ME, et al. Impact of hormone receptor status on patterns of recurrence and clinical outcomes among patients with human epidermal growth factor-2-positive breast cancer in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: A prospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R129. doi: 10.1186/bcr3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tripathy D, Kaufman PA, Brufsky AM, et al. First-line treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in patients with HER2-positive and hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer from registHER. The Oncologist. 2013;18:501–510. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A Study of Trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1) Plus Pertuzumab/Pertuzumab Placebo Versus Trastuzumab [Herceptin] Plus a Taxane in Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer (MARIANNE) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01120184?term=MARIANNE+trastuzumab&rank=1. Accessed March 23, 2015.

- 30.A Study of Pertuzumab in Combination With Herceptin (Trastuzumab) and A Taxane in First-Line Treatment in Patients With HER2-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer (PERUSE) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01572038?term=PERUSE+trastuzumab&rank=1. Accessed March 23, 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.