Abstract

Methane-oxidising bacteria (methanotrophs) require large quantities of copper for the membrane-bound (particulate) methane monooxygenase (pMMO)1,2. Certain methanotrophs are also able to switch to using the iron-containing soluble MMO (sMMO) to catalyse methane oxidation, with this switchover regulated by copper3,4. MMOs are Nature’s primary biological mechanism for suppressing atmospheric levels of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Furthermore, methanotrophs and MMOs have enormous potential in bioremediation and for biotransformations producing bulk and fine chemicals, and in bioenergy, particularly considering increased methane availability from renewable sources and hydraulic fracturing of shale rock5,6. We have discovered and characterised a novel copper storage protein (Csp1) from the methanotroph Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b that is exported from the cytosol, and stores copper for pMMO. Csp1 is a tetramer of 4-helix bundles with each monomer binding up to 13 Cu(I) ions in a previously unseen manner via mainly Cys residues that point into the core of the bundle. Csp1 is the first example of a protein that stores a metal within an established protein-folding motif. This work provides a detailed insight into how methanotrophs accumulate copper for the oxidation of methane. Understanding this process is essential if the wide-ranging biotechnological applications of methanotrophs are to be realised. Cytosolic homologues of Csp1 are present in diverse bacteria thus challenging the dogma that such organisms do not use copper in this location.

Biology exploits copper to catalyse a range of important reactions, but use of this metal has been influenced by its availability and potential toxicity7-9. In eukaryotes, excess copper is safely stored by cytosolic Cys-rich metallothioneins (MTs)10-12. Prokaryotic cytosolic copper-requiring enzymes are not currently known, with most prokaryotes thought not to possess copper storage proteins. Copper-binding MTs, like those in eukaryotes, have been identified in pathogenic mycobacteria where they help detoxify Cu(I) 13. Methanotrophs are Gram negative bacteria that produce specialised membranes to harbour pMMO, which could either be discrete from or connected to the plasma membrane1,14,15. These organisms have the typical machinery for copper efflux from the cytosol7,9, but also possess the only currently characterised prokaryotic copper-uptake system; secreted modified peptides called methanobactins (mbtins)4,16, which bind Cu(I) with high affinity17,18, localise to the cytoplasm19, and are involved in sMMO to pMMO switchover20.

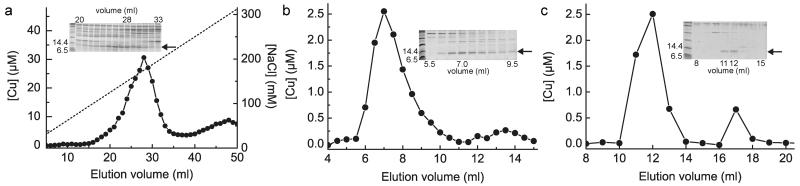

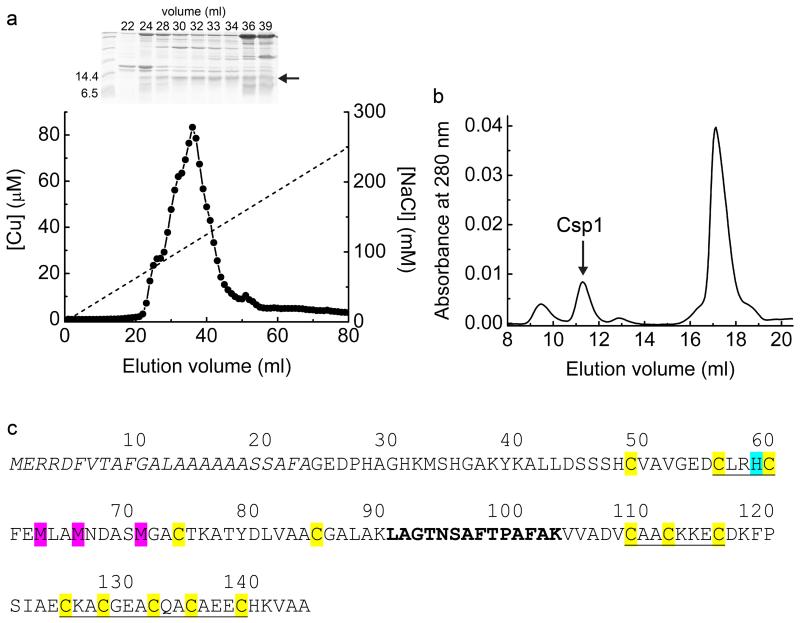

Whilst searching for internalised Cu(I)-mbtin in the switchover methanotroph M. trichosporium OB3b, large amounts of soluble, protein-associated copper were detected. This was unexpected as bioinformatics predicts the transcriptional activator CueR as the only soluble copper protein 21. To identify the copper-binding proteins in the most abundant copper pool, soluble extracts from cells grown under elevated copper were separated by anion-exchange and gel-filtration chromatography. Copper peaks match the intensity profiles of a protein band just below the 14.4 kDa marker (Fig. 1a, b), which has been purified to near homogeneity (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b and Fig. 1c). This band was excised (Fig. 1b, c) and identified by peptide mass fingerprinting as an uncharacterised conserved hypothetical protein (herein Csp1, Extended Data Fig. 1c). The mature protein (122 amino acids) contains 13 Cys residues with a predicted molecular weight of 12591.4 Da consistent with its migration on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Identification and purification of Csp1 from M. trichosporium OB3b.

a, Copper content of anion-exchange fractions (NaCl gradient shown as a dashed line) of extract from M. trichosporium OB3b cells and the sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis of fractions 20 to 33. b, Copper content and SDS-PAGE analysis of the purification of the fraction containing the highest copper concentration (fraction 28) from (a) on a G100 gel-filtration column. A similar anion-exchange fraction (Extended Data Fig. 1a) was purified on a Superdex 75 column (Extended Data Fig. 1b), with the copper content and SDS-PAGE analyses of eluted fractions shown in (c). The band of interest that migrates below the 14.4 kDa marker is indicated in each panel with an arrow, and protein identification was performed on the bands from the 7.0 (b) and 12.0 (c) mL fractions.

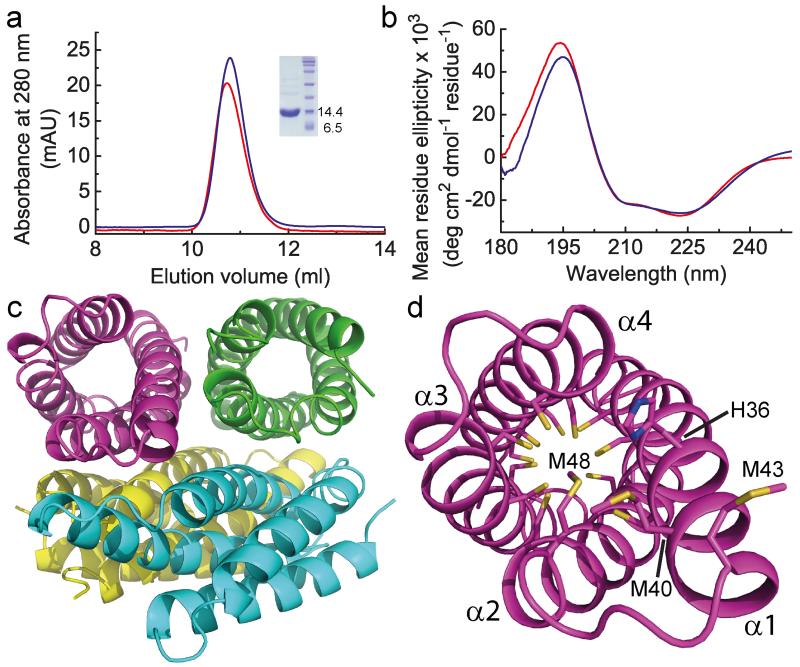

Recombinant apo-Csp1 (12589.8 Da) elutes from a gel filtration column with an apparent molecular weight of ~50 kDa (Fig. 2a), indicating a tetramer in solution (the native protein elutes at a similar volume, compare Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 1b, demonstrating the same quaternary structure). The far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectrum of Csp1 (Fig. 2b) reveals predominantly α-helical (~ 80%) secondary structure22. The asymmetric unit in the crystal structure of apo-Csp1 (Extended Data Table 1) consists of a tetramer of 4-helix bundles (~ 75% α-helix), involving two sets of adjacent monomers aligned in an anti-parallel manner, with pairs of monomers rotated by ~55° (Fig. 2c). The major contact areas between monomers are ~750 to ~820 Å2, consistent with the crystallographic tetramer being present in solution. All 13 Cys residues of apo-Csp1 point into the core of the 4-helix bundle and none are involved in disulfide bonds (Fig. 2d). One end of the bundle, at which the N- and C-termini are found, is relatively hydrophobic whilst some Cys residues appear accessible at the opposite end of the molecule (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. The structure of apo-Csp1.

a, Analytical gel-filtration chromatograms of apo-Csp1 (red line) and protein to which 14.0 molar equivalents of Cu(I) were added (blue line) for samples (100 μM when injected) in 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (Hepes) pH 7.5 containing 200 mM NaCl. The absorbance was monitored at 280 nm with the values for Cu(I)-Csp1 divided by 10 (see Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). The inset shows SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified protein. b, Far-UV CD spectra of apo-Csp1 (red line) and Csp1 plus 14.0 equivalents of Cu(I) (blue line) at 39.6 and 35.7 μM respectively in 100 mM phosphate pH 8.0. c, The tetrameric arrangement in the asymmetric unit of the crystal structure of apo-Csp1, with the side-chains of the Cys residues that point into the core of the 4-helix bundle shown as sticks for one monomer in (d). The opening into the core of the 4-helix bundle is facing out in (d), and involves His36, Met40, Met43 (on the extended α1) and Met48.

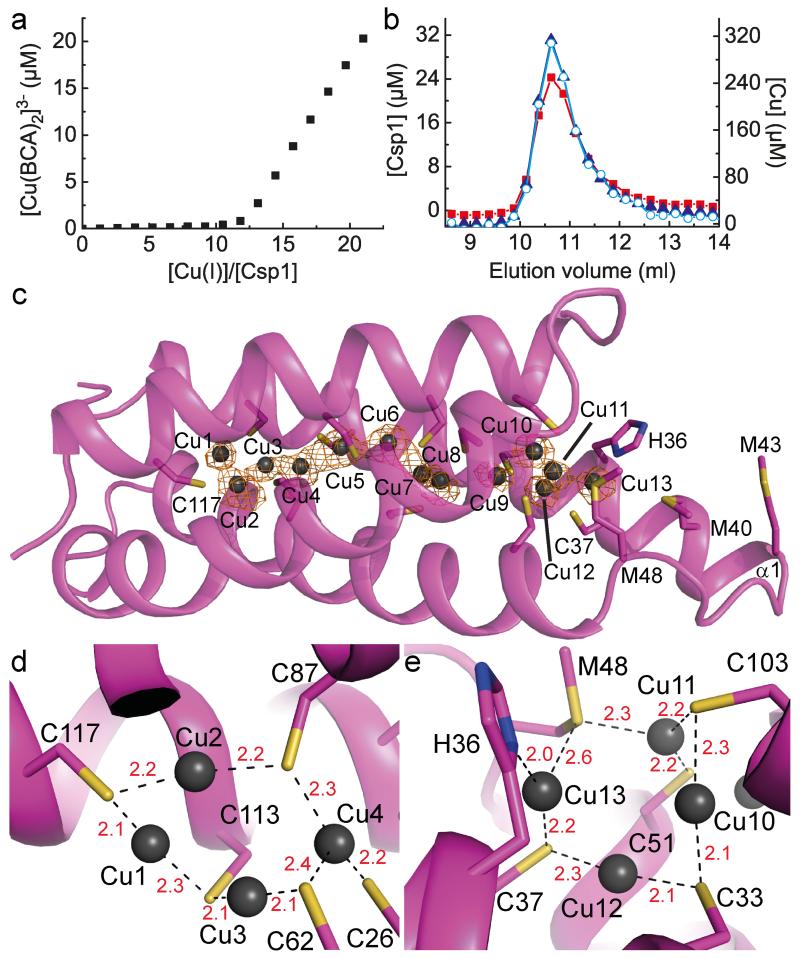

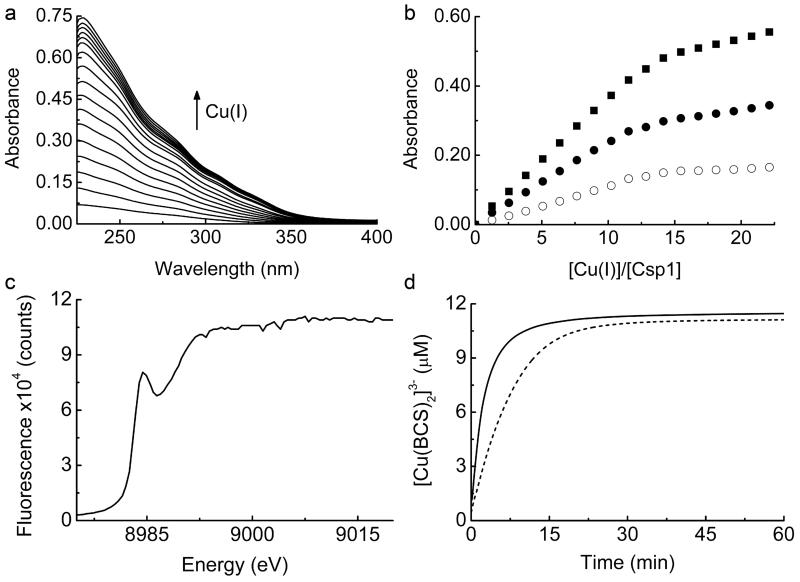

Csp1 is isolated from M. trichosporium OB3b with copper bound (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1a), which along with the arrangement of the Cys residues in the structure of the apo-protein (Fig. 2d), indicates a function in Cu(I) storage. To test this hypothesis, Cu(I) binding was analysed in vitro by monitoring the appearance of (S)Cys→Cu(I) charge transfer bands (Extended Data Fig. 2a)10,23,24, giving a stoichiometry of ~ 11-15 Cu(I) equivalents per Csp1 monomer (Extended Data Fig. 2b). In the presence of relatively low concentrations of the high affinity chromophoric Cu(I) ligand bicinchoninic acid (BCA; logβ2 = 17.7 (ref. 25)) apo-Csp1 binds all Cu(I) until ~ 12-14 equivalents have been added (for example Fig. 3a). Furthermore, an apo-Csp1 sample incubated with ~ 25 equivalents of Cu(I) elutes from a gel-filtration column with ~ 12-13 equivalents of Cu(I) (Fig. 3b). The binding of Cu(I) has no significant effect on either the secondary or quaternary structure (Fig. 2a, b). The crystal structure of Cu(I)-Csp1 is shown in Fig. 3c (Extended Data Table 1). The anomalous difference density for data collected just below the copper-edge identifies 13 copper ions within the core of the 4-helix bundle (Fig. 3c), bound predominantly by the 13 Cys residues. The oxidation state of copper in Csp1 crystals was analysed using X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (Extended Data Fig. 2c). A well-defined peak at 8984 eV, due to the Cu 1s→4p transition, is consistent with 2/3-coordinate Cu(I)26.

Figure 3. Cu(I)-binding by Csp1.

a, Plot of [Cu(BCA)2]3− concentration against the [Cu(I)]/[Csp1] ratio upon titrating Cu(I) into apo-Csp1 (2.43 μM) in the presence of 103 μM BCA (same buffer as for Fig. 2a). [Cu(BCA)2]3− starts forming after ~ 12 equivalents of Cu(I) are added. b, Analytical gel-filtration chromatogram of Csp1 (116 μM) mixed with ~ 25 equivalents of Cu(I) in the same buffer. Csp1 (Bradford, red squares), copper (atomic absorption spectroscopy, blue triangles) and Cu(I) (bathocuproine disulfonate (BCS) in the presence of 7.6 M urea, open cyan circles) concentrations are shown. The main Csp1-containing fractions bind 11.8 to 12.9 equivalents of Cu(I). c, The structure of Cu(I)-Csp1 (chain A) including the anomalous difference density for copper contoured at 3.5 σ (orange mesh). The copper ions (Cu1 to Cu13 correspond to A1123 to A1135 in the PDB file 5AJF) are represented as dark grey spheres and the side chains of Cys, and other key residues as sticks. The coordination of Cu(I) ions at the two ends of the 4-helix bundle are shown in (d) and (e) with bond distances (Å) in red.

The 13 Cu(I) ions are distributed throughout the core of the 4-helix bundle of Csp1 (Fig. 3c-e). Ten of the Cu(I) sites involve bis-Cys (μ2-S for all the Cys ligands) ligation with Cu(I)–S(Cys) bond lengths and S(Cys)–Cu–S(Cys) angles ranging from 2.0 to 2.3 Å and 142° to 177°, respectively (in chain A). Exceptions are Cu11 and Cu13 (Fig. 3e, see below), and also Cu4 (Fig. 3d) that has three coordinating thiolates (S(Cys)–Cu–S(Cys) angles ranging from 90° to 145°. Ten Cu(I) ions are within 2.7 Å of a neighbouring metal (2.8 Å for Cu5 and Cu13 and 2.9 Å for Cu9) with some interacting with more than one Cu(I) (notably Cu7 and Cu10). Four of the Cu(I) sites (Cu1, Cu6, Cu8 and Cu12) are coordinated by the Cys residues from CXXXC motifs (Fig. 3c-e and Extended Data Fig. 1c and 3), with the backbone carbonyl of the first Cys ligand close (2.1 to 2.3 Å) to the Cu(I) ion. At other Cu(I) sites the Cys ligands originate from adjacent α-helices (for example, Cu2, Cu3 and Cu4 in Fig. 3d and Cu10 in Fig. 3e). Cu11 involves ligation by two thiolates and Met48 (2.3 Å) with bond angles ranging from 102° to 142° (Fig. 3e). Cu13 is also coordinated (Fig. 3e) by Met48 (2.6 Å), as well as by His36 (Nδ, 2.0 Å) and Cys37 (2.2 Å). These two atypical Cu(I) sites (Cu11 and Cu13) are found at the open end of the bundle, and with the nearby Met40 and Met43 (Fig. 3c), potentially help to recruit the metal.

Metal storage within an established protein-folding motif has not previously been observed. Iron is stored by ferritins using polymeric 4-helix bundles, but with monomers forming a protein envelope that surrounds a ferric-oxide mineral core27. Storing multiple Cu(I) ions within a 4-helix bundle in Csp1 provides a stark contrast to unstructured apo-MTs that fold around metal clusters. For example, a truncated form of yeast MT binds a Cu(I)8-thiolate cluster using ten Cys residues with six 3-coordinate and two 2-coordinate sites11. A 4-helix bundle is formed upon Cu(I) addition to a synthetic peptide possessing a CXXC motif, and binds a Cu4S4 cluster28. The arrangement of the Cu(I) ions within Csp1 is unprecedented in biology and inorganic chemistry.

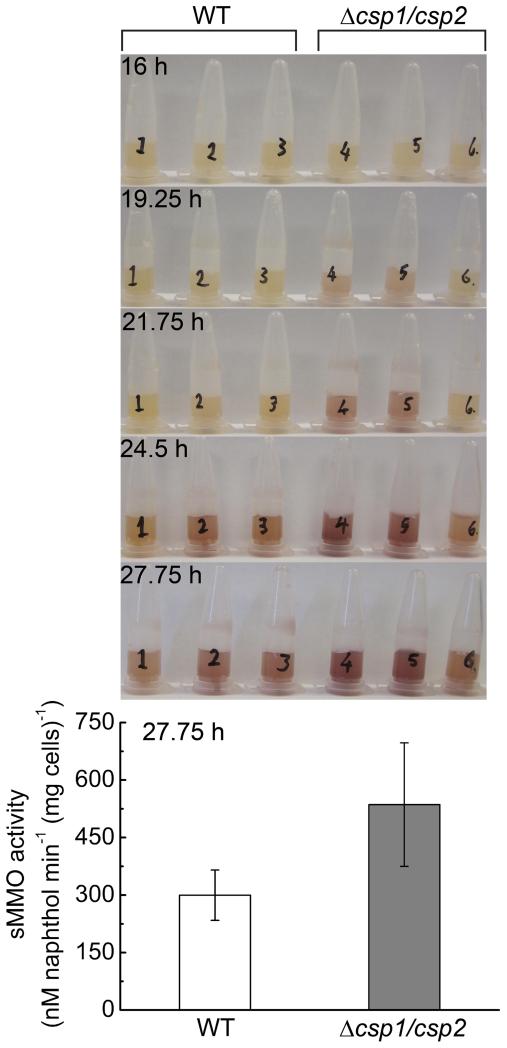

Tetrameric Csp1 is capable of binding up to 52 Cu(I) ions, consistent with a role in copper storage. The major copper requiring protein in M. trichosporium OB3b is pMMO. Regardless of the uncertainty about the structure of the specialised membranes that house pMMO, cytosolic copper must cross a membrane prior to incorporation into this enzyme. Csp1, and its closely related homologue Csp2, possess signal peptides (Extended Data Fig. 1c and 3), predicted as targeting the twin arginine translocation (Tat) machinery29, and therefore locate outside the cytosol. To test whether Csp1 and Csp2 store copper for pMMO the Δcsp1/csp2 double mutant strain of M. trichosporium OB3b was constructed. Switchover to sMMO for cells transferred from high to low copper is significantly faster in Δcsp1/csp2 than in the wild type strain and sMMO activity is 1.8 times greater in the former after almost 28 h (Extended Data Fig. 4). These data are not inconsistent with Csp1 and Csp2 storing, and potentially also chaperoning, copper for pMMO, thus allowing M. trichosporium OB3b to use this enzyme longer for growth on methane when copper becomes limiting, but this hypothesis has not been explicitly tested.

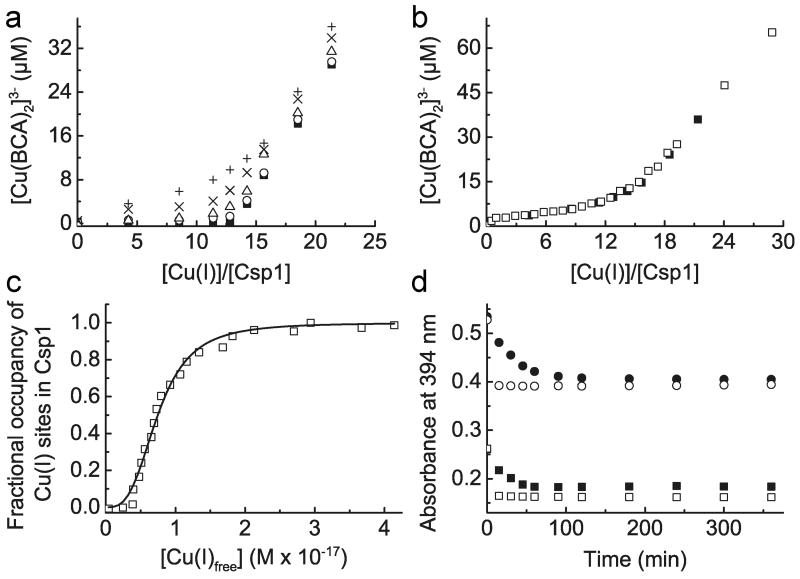

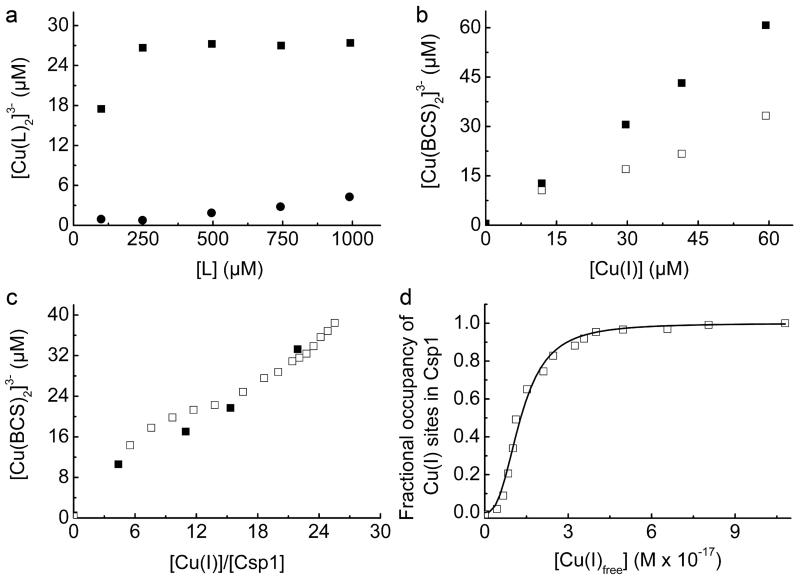

An important attribute of a metal storage protein is its metal affinity. Upon increasing the concentration of BCA Cu(I) starts to be withheld from Csp1 (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 5a-f). The buffering of free Cu(I) by ligands such as BCA and the tighter chromophoric Cu(I) ligand BCS (logβ2 = 20.8 (ref. 25), see Extended Data Fig. 6a, b) has been used to obtain an average Cu(I) affinity for Csp1 of ~ 1 × 1017 M−1 (Fig. 4b, c and Extended Data Fig. 6c, d). Mbtin, the copper-chelating ligand produced by M. trichosporium OB3b, has a much tighter Cu(I) affinity17, and stoichiometrically removes Cu(I) from Csp1 in ~1 h (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 7a-d). This high affinity makes copper removal from imported mbtin potentially problematic (for example apo-Csp1 cannot directly acquire Cu(I) from mbtin, Extended Data Fig. 7e), and Cu(I)-mbtin may need to be degraded within a cell to release its metal cargo18. Csp1 is present at elevated copper levels in M. trichosporium OB3b and sequesters the metal (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1a), whilst mbtin production is suppressed under these conditions4,16. As copper levels in the cell decrease, mbtin will be produced and could play a role in removing and utilising Csp1-bound copper.

Figure 4. Cu(I) affinity of Csp1 and Cu(I) release.

a, Plots of [Cu(BCA)2]3− concentration against the [Cu(I)]/[Csp1] ratio for mixtures of apo-Csp1 (3.57 μM) and Cu(I) in the presence of 120 (filled squares), 300 (open circles), 600 (open triangles), 900 (cross) and 1200 (plus sign) μM BCA (all data acquired after 41 h incubation). b, Plot of [Cu(BCA)2]3− concentration against the [Cu(I)]/[Csp1] ratio for mixtures of apo-Csp1 (3.61 μM) and Cu(I) in the presence of 1210 μM BCA (open squares) for 20 h, along with the data from (a) at 1200 μM BCA (filled squares). c, Fractional occupancy of Cu(I)-binding sites in Csp1 (maximum value 11.7 equivalents) at different concentrations of free Cu(I) from the data shown in (b) at 1210 μM BCA up to a [Cu(I)]/[Csp1] ratio of 19.2. The solid line shows the fit of the data to the non-linear Hill equation giving an average dissociation constant for Cu(I), KCu, of (7.5 ± 0.1) × 10−18 M (n = 3.1 ± 0.2, see Extended Data Fig. 6c, d). d, Plots of the absorbance at 394 nm (spectra in Extended Data Fig. 7a-d) against time after the addition of Cu(I)-Csp1 (1.02 μM) loaded with 13.0 equivalents of Cu(I)) to 13.4 (filled squares) and 27.4 (filled circles) μM apo-mbtin and Cu(I) (13.3 μM) to 13.4 (open squares) and 27.1 (open circles) μM apo-mbtin. All experiments were performed in the same buffer as for Fig. 2a.

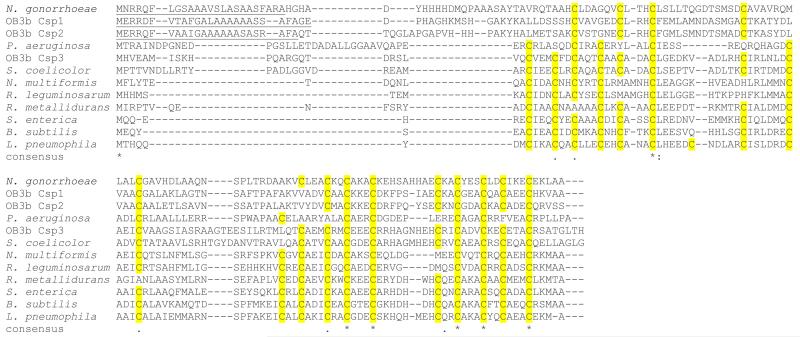

Another Csp1 homologue, Csp3, is also encoded in the M. trichosporium OB3b genome (Extended Data Fig. 3), and is widespread in bacteria (Extended Data Fig. 8). This includes the functionally uncharacterised proteins from Nitrosospira multiformis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (apo-structures are available with PDB codes 3LMF and 3KAW) that also have all Cys residues pointing to the core of 4-helix bundles. Csp3 has no signal peptide (Extended Data Fig. 3) and therefore, unlike Csp1 and Csp2, is presumably cytosolic. If Csp1 and Csp2 are exported via the Tat system they would fold in the cytosol29, perhaps to prevent disulfide formation. Tat-export might also imply copper acquisition prior to export29, allowing transport of large amounts of copper away from systems that remove this metal from the cytosol (CueR and copper-transporting ATPases) and into the same compartment housing pMMO. Csp1 (and Csp2) can store large quantities of copper for, and potentially also deliver the metal to pMMO, an enzyme of great environmental importance that has tremendous biotechnological potential for the utilisation and mitigation of methane. The prediction would be that Csp3 can store copper in the cytosol, not only in M. trichosporium OB3b but in many other bacteria. This raises the possibility that there are cytosolic copper-requiring enzymes in bacteria still to be discovered.

METHODS

Identification and purification of copper proteins from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b

M. trichosporium OB3b cultures were grown as described17 at 27 °C in a 5 L fermentor agitated at 250 rpm in nitrate minimal salts (NMS) medium supplemented with 10 μM iron and typically 5 μM copper. Cultures were analysed for sMMO activity as described17. Cells harvested at an OD600 typically between 1.1 and 2.2 were collected by centrifugation (4 °C) at 9000 g and pellets washed with 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (Hepes) pH 8.8 followed by the same buffer containing 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). The cell pellet was resuspended in 20 mM Hepes pH 8.8 and lysed by freeze grinding in liquid nitrogen30. The lysate was allowed to thaw in an anaerobic chamber (Belle Technology, [O2] << 2 ppm), prior to loading into ultracentrifuge tubes sealed in the anaerobic chamber and centrifuged at 160000 g for 1 h at 10 °C. The supernatant was recovered inside the anaerobic chamber, diluted 5-fold and loaded (either 59 or 90 mg protein from 10 and 16 L of cells, respectively) onto a 5 mL HiTrap Q HP anion-exchange column (GE Healthcare). For the purification of extracts from 10 L of cells the HiTrap column was eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (0 to 500 mM) inside the anaerobic chamber with a homemade mixing device (total volume 80 mL). For the 16 L preparation the HiTrap column was eluted on an Akta Purifier with a linear NaCl gradient (0 to 250 mM) using thoroughly degassed and nitrogen-purged buffers (total volume 80 mL). Copper content in eluted fractions (1 mL) was measured by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Thermo Electron Corp. X series). Samples were diluted 10-fold in 2% nitric acid containing 20 μg/L silver as internal standard, and analysed for 63Cu and 107Ag in standard mode (100 reads, 30 ms dwell, 3 channels, 0.02 atomic mass unit separation, in triplicate). Copper concentration was determined by comparison to matrix-matched elemental standard solutions. Copper-containing fractions were analysed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using Oriole fluorescent gel stain (Bio-Rad). All images of fluorescently-labelled gels have been inverted to make bands clearer in print.

Gel-filtration chromatography of copper-containing fractions was performed on either a Sephadex G100 (Sigma) packed column (1 × 20 cm) inside the anaerobic chamber, or on a Superdex S75 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare) column in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl (thoroughly degassed and nitrogen-purged for the Superdex 75 column that was attached to an Akta Purifier) and at flow rates of 0.35 and 0.8 mL/min respectively (fraction size 1 mL). Proteins whose intensity on SDS-PAGE gels correlated with copper concentration profiles were excised from gels and underwent peptide mass fingerprinting31. Digestion with trypsin was performed at an E:S ratio of 1:100 overnight in 50 mM NH4HCO3 pH 8. The resultant peptides were resuspended in 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid and desalted using C18 ZipTips (Millipore). Peptides were then separated on a NanoAcquity liquid chromatography system (Waters) using a 75 μm × 100 mm C18 capillary column (Waters). A linear gradient from 1 to 50% acetonitrile in 0.1% aqueous formic acid was applied over 30 min at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. Eluted peptides were detected using a linear trap quadrupole Fourier transform (LTQFT) mass spectrometer (ThermoElectron) in positive ionisation mode with scans over 300 – 1500 m/z in data-dependent mode and a FT-MS resolution setting of 50000. The top five ions in the parent scan were subjected to MS/MS analysis in the linear ion trap region. The proteins from which detected peptides originated were identified using the Mascot MS/MS ion search tool (Matrix Science) by comparison against the entire database of proteobacteria in NCBI. SignalP and TatP were used to identify putative signal sequences32.

Cloning the Csp1 gene

Csp1 without its predicted signal peptide (i.e. Gly25 to Ala144, see Extended Data Fig. 1c) was amplified from M. trichosporium OB3b genomic DNA using primers Csp1_F and Csp1_R (Extended Data Table 2) and cloned into pGEMT, which introduced a Met residue at the N-terminus. Both strands of the gene were verified by sequencing, which was subsequently cloned into the NdeI and NcoI sites of pET29a (pET29a_Csp1).

Expression and purification of Csp1

Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with pET29a_Csp1 was grown in LB media at 37 °C (100 μg/mL kanamycin) until an OD600 of ~ 0.6. Cells were induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, harvested after 6 h and stored at −20 °C. Pellets were re-suspended in 20 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris) pH 8.5 plus 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), sonicated and centrifuged at 40000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was diluted 5-fold in 20 mM Tris pH 8.5 containing 1 mM DTT and loaded onto a HiTrap Q HP column (5 mL) equilibrated in the same buffer. Proteins were eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (0-300 mM, total volume ~ 200 mL). Csp1-containing fractions, identified by SDS-PAGE, were combined, diluted 10-fold in 10 mM Tris pH 7.5 plus 1 mM DTT, applied to a HiTrap Q HP column (5 mL) equilibrated in the same buffer and eluted using a linear NaCl gradient (0-200 mM, total volume ~ 200 mL). The purest fractions, identified by SDS-PAGE, were combined and thoroughly exchanged into 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl using either a stirred cell or a centrifugal filter unit (typically with 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off membranes). Except for crystallisation of the apo-protein, Csp1 was further purified by gel-filtration chromatography on a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 containing 200 mM NaCl. The protein was found to contain no copper and zinc using atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS, with an M Series spectrometer, Thermo Electron Corp.) typically with ten standards containing up to 1.8 ppm copper and 1.0 ppm zinc in 2% HNO3 using the standard calibration method. The mass of purified Csp1 was verified both by matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight and FT ion cyclotron resonance MS. The Met residue introduced at the N-terminus during cloning is largely cleaved in the over-expression host giving a purified protein with an experimental mass of 12589.8 Da, consistent with the calculated value (12591.4 Da) for a mature protein having Gly1 and Ala122 at the N- and C-termini respectively.

Isolation, purification and quantification of methanobactin

The apo- and Cu(I)-forms of full length methanobactin (mbtin) from M. trichosporium OB3b was isolated, purified, and quantified as described previously17.

Quantification of Csp1

Apo-Csp1 was quantified by the reduction of 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB, Ellman’s reagent) in a sealed anaerobic quartz cuvette monitored at 412 nm using a λ35 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer)33. The reaction was initiated in the anaerobic chamber by the addition of apo-Csp1 (final concentration typically 0.2-4 μM) to a buffered solution of DTNB (240 to 480 μM) in the presence of urea (final concentration > 7 M). Under these conditions Csp1 rapidly unfolds, particularly at concentrations < 8 μM (Extended Data Fig. 5g, h). The buffer was typically 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, but in some cases 100 mM phosphate pH 8.0 plus 1 mM EDTA was used (the 5-10 mM DTNB stock solution was always made in 100 mM phosphate pH 8.0 plus 1 mM EDTA). After approximately 10-20 min, the absorbance at 412 nm reached a plateau and it was assumed that all 13 Cys residues of unfolded apo-Csp1 had reacted with DTNB (in the absence of urea very little reaction with DTNB occurs consistent with the structure of the apo-protein (Fig. 2d)). Apo-Csp1 (~ 4 to 23 μM) incubated overnight in the anaerobic chamber with DTT (~ 2 to 6.4 mM) and desalted on a PD10 column (GE Healthcare) was also quantified with DTNB in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and > 7 M urea (again little reaction with DTNB occurred in the absence of urea). At higher DTT concentrations samples were desalted twice to ensure all DTT had been removed. For the DTNB reaction, a molar absorption coefficient (ε value) of 14150 M−1cm−1 at 412 nm24,33,34 was verified using glutathione with and without > 7 M urea in both 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA (3 times) and also in 100 mM phosphate pH 8.0 plus 1 mM EDTA (twice). Apo-Csp1 concentrations were also determined using the Bradford assay (Coomassie Plus protein assay kit, Thermo Scientific) with BSA standards (0-1000 μg/mL). The ratio of apo-Csp1 concentration obtained using the Bradford and DTNB assays (Bradford:DTNB ratio) is 1.11 ± 0.12 (n = 27) for samples not treated with DTT and 1.03 ± 0.04 (n = 9) for samples that were reduced prior to these assays. Incubation with DTT does not have a significant effect on the thiol count and this step was excluded from all subsequent experiments as contamination of apo-Csp1 with even trace amounts of DTT would influence quantification using DTNB.

Investigating Cu(I)-binding to Csp1

Cu(I) stock solutions (50-100 mM [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6 in 100% acetonitrile) were diluted to ~ 1-12 mM in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl in the anaerobic chamber24,35. Copper concentrations were determined by AAS and Cu(I) was quantified anaerobically by UV-Vis with the chromophoric high affinity Cu(I) ligands bathocuproine disulfonate (BCS) and bicinchoninic acid (BCA) by monitoring formation of [Cu(BCS)2]3− and [Cu(BCA)2]3− at 483 nm (ε = 12500 M−1 cm−1) and 562 nm (ε = 7700 M−1 cm1) respectively35-38. Cu(I) was added to apo-Csp1 by mixing the appropriate amount of the buffered Cu(I) solution with apo-protein (~ 2 to 200 μM) that had been quantified by DTNB, in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl in the anaerobic chamber. Using DTNB in urea is a more precise method for quantifying apo-Csp1 than the Bradford assay, particularly at low protein concentrations, and was therefore used routinely. However, the DTNB assay in urea cannot be used for Cu(I)-Csp1 due to very slow unfolding (Extended Data Fig. 5i). Therefore, for most Cu(I)-Csp1 samples the number of Cu(I) equivalents quoted are based on the apo-protein concentration determined by DTNB (the Cu(I)-Csp1 concentrations take into account dilution of the sample due to the addition of Cu(I) and the number of Cu(I) equivalents quoted are those in the final sample). The [Cu(I)]/[Csp1] ratio was routinely checked using protein (Bradford assay) and copper (AAS and with 2.5 mM BCS both in the absence and presence of > 7 M urea, compared in Extended Data Fig. 2d) quantifications, with good agreement. For titrations (performed > 10 times), Cu(I) from the buffered solution was added to apo-Csp1 (~ 2 to 20 μM) in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl in a sealed anaerobic quartz cuvette using a gastight syringe (Hamilton). The immediate appearance of ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) bands, characteristic of Cu(I) coordination by thiolates10,23,24, was monitored in the UV region. Emission spectra were acquired on a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian) by exciting at 280 nm and following the emission in the 400-700 nm range using emission and excitation slits of 20 and 10 nm respectively. The concentration of the Cu(I) solution was regularly checked during titrations, usually with BCS, and replaced as required.

Competition between Csp1 and chromophoric ligands

The binding of Cu(I) by Csp1 in the presence of either BCA or BCS was investigated in a variety of ways. Additions of Cu(I) to Csp1 (~ 1.6 to 3.0 μM) were performed in the presence of ~ 90 to 110 μM BCA in 20 mM 2-(-N-morpholino)ethane-sulfonic acid (Mes) at pH 5.5 (the pKa of BCA is 3.8 (ref. 25) and its β2 value is therefore hardly affected at this pH value) and 6.5, Hepes at pH 7.5, N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid (Taps) at pH 8.5 and 2-(-N-cyclohexylamino)ethane-sulfonic acid (Ches) at pH 9.5, all plus 200 mM NaCl. [Cu(BCA)2]3− concentrations were determined under anaerobic conditions as described above. This experiment was repeated twice at pH 6.5, at least 3 and up to 6 times at other pH values, except at pH 7.5 that was performed > 10 times. Apart from at pH 5.5, equilibration typically took < 10 min (~ 20 min at ~ 11 to 15 Cu(I) equivalents). During these titrations the concentration of the Cu(I) solution was regularly checked and replaced as required. For experiments at pH 5.5 (Mes), and at higher concentrations of BCA (up to ~ 1.2 mM and using ~ 2.0 to 3.7 μM apo-Csp1), UV-Vis spectra were acquired between 4 and 48 h after mixing, to ensure equilibration had occurred (experiments at pH 6.5 and 9.5 were repeated 2 and 4 times respectively, whilst the experiment at pH 7.5 was repeated 6 times). The final pH values of samples were checked at the end of experiments and were within 0.1 pH units (0.2 at pH 5.5) of the buffer used.

A comparison of the ability of Csp1 to compete with BCA and BCS was performed at least 3 times by incubating Cu(I)-Csp1 (~ 2.4 to 2.7 μM) loaded with ~ 10 to 13 equivalents of Cu(I) with various concentrations of either ligand in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl in the anaerobic chamber. [Cu(BCS)2]3− and [Cu(BCA)2]3− concentrations were determined by UV-Vis under anaerobic conditions for mixtures incubated for various times (4 to 48 h) with very little change. Furthermore, apo-Csp1 (~ 2.5 to 2.8 μM) plus BCS (~ 100 or 250 μM) was incubated anaerobically with 0 to ~ 22 Cu(I) equivalents in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl (repeated 4 times). The absorbance at 483 nm was monitored anaerobically after 4 h and up to 43 h after mixing (no variation observed). The kinetics of Cu(I) removal from Cu(I)-Csp1 (~ 0.3 to 1.6 μM) loaded with ~ 11 to 14 equivalents of Cu(I) by ~ 2500 μM BCS was compared (5 times) in the absence and presence of > 7 M urea monitored anaerobically at 483 nm in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl.

Estimation of the average Cu(I) affinity of Csp1

The average Cu(I) affinity of Csp1 was estimated by determining the Cu(I) occupancy of Csp1 as a function of the concentration of free Cu(I) ([Cu(I)free]) buffered using either BCA or BCS39,40. Apo-Csp1 (~ 2.7 and ~ 3.6 μM respectively) in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl was mixed anaerobically with increasing Cu(I) concentrations in the presence of BCS (101 μM) or BCA (1210 and 2000 μM). Mixtures were incubated for up to 67 h. The final pH values of samples were checked at the end of experiments. The concentration of [Cu(BCA)2]3− and [Cu(BCS)2]3− ([Cu(L)2], where L = BCA or BCS) were determined as described above and the concentration of Cu(I) bound to Csp1 ([Cu(I)Csp1]) was calculated using equation (1) where [Cu(I)total] is the total concentration of Cu(I) added;

| (1) |

[Cu(I)free] was calculated using equation (2);

| (2) |

where [L’] is the total free ligand concentration ([L’] = [L] – 2[Cu(L)2]) and β2 is the affinity of either BCA or BCS for Cu(I) (logβ2 = 17.7 and 20.8 respectively25). The Cu(I) occupancy was determined by dividing [Cu(I)Csp1] obtained from equation (1) by the Csp1 concentration. The fractional Cu(I) occupancy was calculated using the maximum value observed in a particular experiment (see below) and plots against [Cu(I)free] were fitted to the non-linear form of the Hill equation (3) to obtain the average dissociation constant of Csp1 for Cu(I) (KCu) and Hill coefficient (n value).

| (3) |

The maximum calculated Cu(I) occupancies of Csp1 were 11.3 and 11.7 equivalents for the BCS and BCA experiments at 101 and 1210 μM respectively. Cu(I)-Csp1 samples with the maximum occupancy (for BCS from the titration and using samples prepared specifically for BCA) were separated from [Cu(L)2]3− and free L using a PD10 column in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl. The protein and copper content of the Cu(I)-Csp1-containing fractions were analysed with Bradford assays, and using BCS in the presence of > 7 M urea. 11.6 ± 0.6 equivalents of Cu(I) per Csp1 were determined for samples from the experiment with 101 μM BCS to which 24.2 to 25.5 equivalents of Cu(I) were added (11.0‐11.3 equivalents calculated using equation (1)), and 12.8 ± 0.7 for a Csp1 sample in the presence of 1200 μM BCA to which 18.4 equivalents of Cu(I) were added (11.3 to 11.6 equivalents calculated using equation (1)). In experiments with BCA, [Cu(I)Csp1] appeared to decrease at higher Cu(I) concentrations and this effect was much greater at higher BCA concentrations. For the data shown in Fig. 4b at 1210 μM BCA, [Cu(I)Csp1] decreased by < 10% of the maximum value when 28.9 equivalents of Cu(I) were added (~ 20% upon addition of 49.5 equivalents of Cu(I) to a separate apo-Csp1 sample). In an experiment at 2000 μM BCA, the maximum number of Cu(I) equivalents bound by Csp1 calculated using equation (1) was 9.33, achieved upon addition of 19.3 equivalents of Cu(I) and [Cu(I)Csp1] appeared to decrease by almost 50% upon addition of 49.6 equivalents of Cu(I). The fit of the data up to 19.3 Cu(I) equivalents added, to the non-linear Hill equation, gives KCu= (6.3 ± 0.1) × 10−18 M (n = 4.1 ± 0.2), consistent with the values at lower BCA concentration (see Fig. 4c). A comparable apo-Csp1 sample in the presence of 2000 μM BCA plus 59.9 equivalents of Cu(I) that gave 5.18 Cu(I) equivalents calculated using equation (1), was found to contain 11.6 ± 0.6 equivalents of Cu(I) after desalting on a PD10 column. We are currently unsure of the reason for the apparent decrease in [Cu(I)Csp1], but it could be the result of the formation of Csp1-Cu(I)-BCA adducts. Such species may contribute to the absorbance at 562 nm resulting in an apparent decrease in [Cu(I)Csp1]. However, this has little effect on the data at 1210 μM BCA and the agreement in KCu for this experiment and that at 101 μM BCS (see Extended Data Fig. 6d) is very good (a fit of a repeat of the experiment with BCS to the non-linear Hill equation gave KCu= (1.3 ± 0.1) × 10−17 M (n = 2.4 ± 0.2)).

Analytical gel-filtration chromatography of apo- and Cu(I)-Csp1

Analytical gel-filtration chromatography of apo-Csp1 (~10-100 μM) and protein (~2-120 μM) plus ~ 12 to 14 equivalents of Cu(I) was performed on a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column equilibrated in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl degassed and purged with nitrogen24. Injection volumes ranged from 100 to 350 μL, the flow rate was 0.8 mL/min and absorbance was monitored at 280 nm. Apparent molecular weights of 51 ± 3 (n = 21) and 50 ± 3 (n = 18) kDa for apo- and Cu(I)-Csp1 respectively were calculated from elution volumes by calibrating the column with a low molecular weight calibration kit (GE Healthcare)24. The gel-filtration analysis of apo-Csp1 (~70 to 150 μM) plus ~ 22 to 26 equivalents of Cu(I) was performed 3 times and the eluted fractions were quantified for protein with Bradford assays, and for copper by AAS and Cu(I) using BCS in the presence of 7.6 M urea.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra (180-250 nm) were recorded using a JASCO J-810 spectrometer36,41. Apo-Csp1 and protein plus 14.0 equivalents of Cu(I) were analysed in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl and in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 8 (buffer exchanged using a PD10 column). Protein concentrations ranged from 7.94 to 39.7 μM (0.10 to 0.50 mg/mL). The pH-stability of apo-Csp1 in 20 mM buffer pH 5.5 (Mes), 7.5 (Hepes) and 9.5 (Ches), all plus 200 mM NaCl, was monitored during 43 h incubation in the anaerobic chamber, with the final pH values of samples within 0.1 pH unit of the expected value (repeated at least twice). The α-helical content of apo- and Cu(I)-Csp1 was routinely found to be ~80 % (repeated more than 10 times). The unfolding of apo-Csp1 and protein plus 14.0 equivalents of Cu(I) was monitored after the addition of urea (final concentration > 7 M) at pH 7.5.

Cu(I) exchange between Csp1 and methanobactin

Cu(I)-Csp1 (~ 0.8 to 1.0 μM) loaded with ~ 13 equivalents of Cu(I) was added to apo-mbtin (~ 10 to 13 or ~ 20 to 27 μM). UV-Vis spectra were acquired before the addition of Cu(I)-Csp1 and up to 6 h after mixing (repeated 3 times). Controls were performed by the addition of ~ 10 to 13 μM Cu(I) to apo-mbtin (~ 10 to 13 or ~ 20 to 27 μM). The possibility of copper transfer from Cu(I)-mbtin (typically ~ 2.2 to 3.0 μM) to apo-Csp1 (from 143 to 234 μM) was investigated for up to 20 h by UV-Vis spectroscopy (repeated four times). All of the mbtin-containing samples were incubated anaerobically protected from light.

Crystallisation, data collection, structure solution and refinement

Crystals of apo-Csp1 (~ 20 mg/mL, Bradford assay) in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 were obtained aerobically at 20 °C using the hanging drop method of vapour diffusion from 1 μL of protein mixed with 1 μL of 0.1 M bis-Tris pH 6.5 plus 25% w/v PEG 3350 (500 μL well solution) and were frozen in N-Paratone oil. Cu(I)-Csp1 (~ 9.5-11 mg/mL, Bradford assay) was prepared by adding ~ 12-14 equivalents of Cu(I) to apo-protein (~ 70-80 μM, quantified by DTNB) in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl and subsequently concentrated by ultrafiltration (all performed anaerobically). Cu(I)-Csp1 prepared anaerobically was removed from the anaerobic chamber for < 20 min (Cu(I)-Csp1 shows no sign of oxidation even after incubation in air for 42 h) to allow screens to be set up with a crystallisation robot. The crystallisation trays were transferred back into the anaerobic chamber via a port that was purged with nitrogen for 3 min and were in the chamber for < 5 min prior to being sealed. Cu(I)-Csp1 crystallised at room temperature using the sitting drop method of vapour diffusion with 200 nL of protein plus 100 nL of 0.03 M MgCl2, 0.03 M CaCl2, 0.1 M Tris-Bicine pH 8.5, 12.5% v/v 2-methyl-2,4 pentanediol (racemic) plus 12.5% PEG 1000 and 12.5% PEG 3350 (80 μL well solution). The Cu(I)-Csp1 crystal for the XANES spectrum shown in Extended Data Fig. 2c was obtained as above but using 600 nL of protein plus 300 nL of 0.025 M MgCl2, 0.025 M CaCl2, 0.1 M Tris-Bicine pH 8.5, 13.5 % v/v 2-methyl-2,4 pentanediol (racemic) plus 13.5% PEG 1000 and 13.5% PEG 3350 (80 μL well solution). Crystals were frozen directly in the reservoir solution.

Diffraction data were collected at the Diamond Light Source, U.K., on beamlines I02 (apo-Csp1, λ = 0.9795 Å) and I24 (Cu(I)-Csp1, λ = 1.3777 Å) at 100 K, processed and integrated with XDS and scaled using Aimless42,43. For both datasets, space groups were determined using Pointless and later confirmed during refinement44. The phase was solved by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion using copper, but was complicated by poorly resolved low-resolution reflections. The omission of data from 44.42-10.00 Å was required for successful heavy atom location and the calculation of initial phases. Phasing, density modification and initial model building were performed using PHASER_EP45 through the CCP4 interface46, utilising SHELXD47, PARROT48 and BUCCANEER49. The model of Cu(I)-Csp1 was used as the search model for molecular replacement in Molrep50 to solve the apo-protein dataset. The first eleven residues could not be modeled in both structures (His12 is close to the open end of an adjacent monomer in the Csp1 tetramer). Solvent molecules were added using COOT and checked manually. Simple solvent scaling was used for the apo-Csp1 model and Babinet solvent scaling was used for the Cu(I)-Csp1 model. All other computing used the CCP4 suite of programs46. Five percent of observations were randomly selected for the Rfree set. The models were validated using MolProbity51 and data statistics and refinement details are reported in Extended Data Table 1. In a Ramachandran plot 100% of residues are in most favored regions for both models and chain A of apo- and Cu(I)-Csp1 overlay with an rmsd of 0.42 Å. In the structure of Cu(I)-Csp1 (5AJF) the Cu(I) ions referred to herein as Cu1 to Cu13 are numbered A1123 to A1135 in chain A and the corresponding sites in chain B are numbered B1123 to B1135.

X-ray Absorption Near Edge Spectroscopy

X-ray Absorption Near Edge spectroscopy (XANES) was conducted on beamline I24 at Diamond Light Source, U.K., using a Vortex-EX detector (Hitachi). X-ray fluorescence was measured on a fresh Cu(I)-Csp1 crystal between 8948 and 9030 eV with an acquisition time of 3 s per data point and a constant step of 0.5 eV for the spectrum shown in Extended Data Fig. 2c (measurements were made on at least two other crystals giving very similar spectra).

Construction of strain Δcsp1/csp2 of M. trichosporium OB3b

A double mutant, strain Δcsp1/csp2, was constructed by sequential deletion of csp1 followed by csp2, from M. trichosporium OB3b, using a previously described method52 with minor modifications. In each case, using genomic DNA from M. trichosporium OB3b as template, upstream and downstream regions (approximately 500 bp) of the target were amplified by PCR using primers (see Extended Data Table 2) 684AF/684AR and 684BF/684BR (for csp1) and 1592AF/1592AR and 1592BF/1592BR (for csp2). The resulting fragments were cloned into pK18mobsacB52, which was then used to transform E. coli strain S17.153. The constructs were introduced into M. trichosporium OB3b by conjugation as previously described54 except that nalidixic acid was not required to remove E. coli contamination. Single crossover mutants were selected on NMS plates containing kanamycin (12.5 μg/mL). Following cultivation in liquid medium without selection, double crossover mutants, with a deletion of the target gene, were selected by plating on NMS plates containing sucrose (7.5% w/v). Gene deletion was confirmed by PCR using primers (outside the cloned regions) 684TF/684TR2 (for csp1) and 1592TF/1592TR (for csp2) and sequencing.

sMMO activity of wild type and mutant strains of M. trichosporium OB3b

The wild type (WT) and strain Δcsp1/csp2 were grown in triplicate at 30 °C in NMS medium (50 mL), containing 6 μM copper, in 250 mL flasks supplied with 20% (v/v) methane and agitated at 150 rpm. At late exponential phase (OD540 0.8 – 1.0) cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 g for 15 min (22 °C), washed once and re-suspended in NMS copper-free medium to a density of 1.5 – 1.6 (OD540). Cell suspension (22 mL) was transferred to fresh 250 mL flasks and incubated with 20% v/v methane. Approximately every three hours, samples (1 mL) were withdrawn and used to measure culture density (OD540) and sMMO activity. After 12.75 and 19.25 h, flasks were flushed with air and re-supplied with methane. To estimate sMMO activity, cells (approximately 0.5 mL) were incubated with a few crushed crystals of naphthalene at 30 °C for 30 min before addition of 40 μL of tetrazotized o-dianisidine (10 mg/mL). Immediate development of an intense purple colour indicated sMMO activity55. To quantify sMMO activity, 150 μL of cell suspension was centrifuged at 6000 g for 10 min (22 °C) and the cell pellet re-suspended in 1 mL of 10 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.8 containing 10 mM formate. Crushed naphthalene crystals were added and the reaction initiated by addition of 25 μL of tetrazotized o-dianisidine (10 mg/mL). The mixture was shaken vigorously and the absorbance at 528 nm, corresponding to the formation of naphthol, was monitored for 15 min at 30 °C. Activities were normalised to cell density.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1 . Purification of proteins from M. trichosporium OB3b and the amino-acid sequence of Csp1.

a, The copper content of anion-exchange fractions (NaCl gradient shown as a dashed line) and the SDS-PAGE analysis of selected fractions (1 mL) from the purification of soluble extract from M. trichosporium OB3b cells. The band just below the 14.4 kDa marker, indicated with an arrow, is present. Fraction 32 was judged to have the lowest level of contaminating proteins and was further purified by gel-filtration chromatography on a Superdex 75 column (b). Csp1 is present in the peak that elutes at ~ 11 mL and contains considerable copper (see Fig. 1c). c, The amino-acid sequence of Csp1 showing the predicted Tat leader peptide (the first 24 residues of the pre-protein) in italics. The 13 Cys residues are highlighted in yellow and His36 (cyan), Met40, Met43 and Met48 (magenta) are also indicated (the numbering of these residues refers to the mature protein). The CXXXC and CXXC motifs are underlined. The region in bold corresponds to the single tryptic fragment identified on two separate occasions in MS analysis, representing 11% sequence coverage of the mature protein (Mascot search of peptide mass fingerprint, expect value = 1.9 × 10−5). The sequence of this fragment was confirmed by liquid chromatography/MS/MS (data not shown). This is the only tryptic peptide from the mature protein that would be anticipated to be readily detected by MS (due to either small mass or presence of Cys residues in all other theoretical tryptic fragments) and is unique to this protein amongst all proteobacterial protein sequences in the NCBInr database.

Extended Data Figure 2 . Cu(I) binding to Csp1.

a, UV-Vis difference spectra upon the addition of Cu(I) to apo-Csp1 (5.32 μM) showing the appearance of S(Cys)→Cu(I) LMCT bands10,23,24. b, Plots of absorbance at 250 (filled squares), 275 (filled circles), and 310 (open circles) nm against [Cu(I)]/[Csp1] ratio taken from the spectra in (a). The absorbance rises steeply until ~ 11-15 Cu(I) equivalents but continues to rise, particularly at lower wavelengths, making binding stoichiometry difficult to determine precisely with this approach. Systems that bind multiple Cu(I) ions in clusters such as those found in metallothioneins, typically give rise to luminescence at around 600 nm10,13. However, limited luminescence is observed at 600 nm during the titration of Cu(I) into Csp1 (data not shown). c, X-ray absorption near edge spectrum of a fresh crystal of Cu(I)-Csp1 at 100 K. d, Plots of [Cu(BCS)2]3− formation against time after the addition of Cu(I)-Csp1 (0.93 μM) loaded with 11.8 equivalents of Cu(I) to 2510 μM BCS either in the absence (dashed line) or presence (solid line) of 7.9 M Urea. Cu(I) is removed faster in urea and is limited by the rate of Cu(I)-Csp1 unfolding (Extended Data Fig. 5i). The presence of urea has little effect on the end point for this reaction. a, b and d were all performed in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 containing 200 mM NaCl.

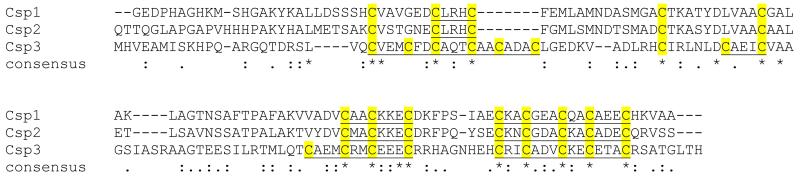

Extended Data Figure 3 . Sequence comparison of Csp1 homologues in M. trichosporium OB3b.

The M. trichosporium OB3b genome possesses two genes that code for Csp1 homologues; Csp2 and Csp3 having 58 and 19% sequence identity to Csp1, respectively. The predicted Tat leader peptides of Csp1 (MERRDFVTAFGALAAAAAASSAFA) and Csp2 (MERRQFVAAIGAAAAAASASRAFA) are omitted. The Cys residues (13 in Csp1 and Csp2 and 18 in Csp3) are highlighted in yellow with CXXXC and CXXC motifs underlined. A CXXXC motif in an α-helix allows both of the Cys residues to coordinate the same Cu(I) ion (Fig. 3d, e), which is not the case for a CXXC motif. This is consistent with the observation that a synthetic peptide containing a CXXC motif binds a Cu4S4 cluster via a 4-helix bundle made from four peptides, with coordination involving only one Cys per peptide28,56. The alignment was produced using the T-coffee alignment tool57. The * symbol indicates fully conserved sequence positions, whilst the: and. symbols indicate strongly and weakly similar sequence positions respectively.

Extended Data Figure 4 . sMMO activity of wild type M. trichosporium OB3b and the Δcsp1/csp2 strain.

Purple colour, indicating sMMO activity, is evident at 19.25 h in the Δcsp1/csp2 strain (tubes 4 – 6), but not until 24.5 h in the wild type (WT, tubes 1 – 3) when using a qualitative assay. When quantified spectrophotometrically at 27.75 h, the average sMMO activity in the Δcsp1/csp2 strain (grey) is 1.8 fold greater (p = 0.04, one-tailed t-test) than that of the WT (white), as shown in the bar chart (mean ± s.d. of three replicates).

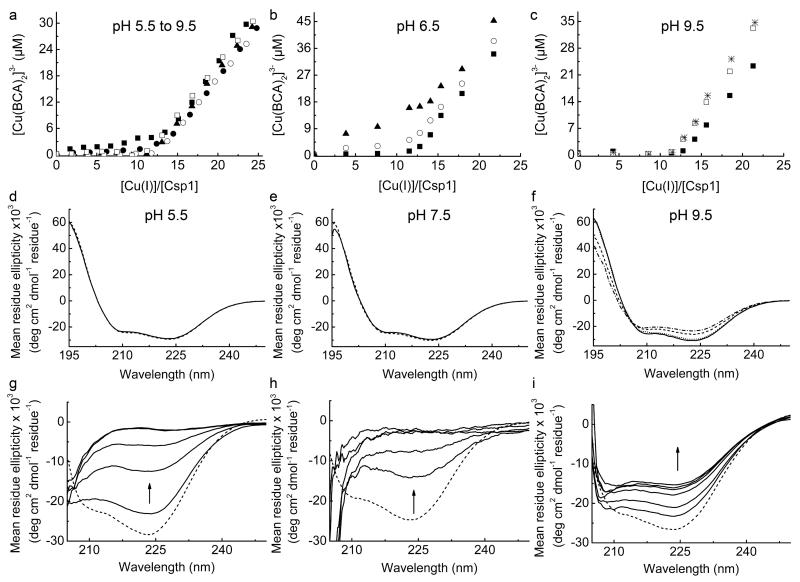

Extended Data Figure 5 . The dependence on pH of competition between Csp1 and BCA for Cu(I), and far-UV CD spectra showing pH stability and unfolding of Csp1 in urea.

a, Plots of [Cu(BCA)2]3− concentration against [Cu(I)]/[Csp1] ratio for the addition of Cu(I) to apo-Csp1 (2.38-2.56 μM) in the presence of 103 μM BCA in 20 mM buffer (see Methods) at pH 5.5 (filled squares), 6.5 (filled circles), 7.5 (filled triangles), 8.5 (open circles) and 9.5 (open squares) plus 200 mM NaCl. Equilibration is fast (< 20 min) at pH 6.5 and higher and the data shown are from titrations of Cu(I) into apo-Csp1. At pH 5.5 equilibration is slower and the data are for mixtures incubated for 21 h. Also shown are results for mixtures of Cu(I) with apo-Csp1 (3.31-3.67 μM) at pH 6.5 (b) and 9.5 (c) in the presence of 120 (filled squares), 300 (open circles), 450 (stars), 600 (filled triangles), and 900 (open squares) μM BCA, all after 15 h incubation. At lower BCA concentrations Csp1 is able to effectively compete for Cu(I) in the pH 6.5 to 9.5 range giving Cu(I) binding stoichiometries of 12-14 (see also Fig. 3a and Fig. 4a). At pH 5.5 Csp1 competes less effectively with BCA for Cu(I) most likely due to the protonation of Cys ligands37. This is consistent with greater competition by 600 μM BCA at pH 6.5 (b) compared to pH 7.5 (Fig. 4a). The stability of apo-Csp1 over the pH and time range used for experiments with BCA (and BCS) was determined using far-UV CD spectroscopy. The spectra of apo-Csp1 (solid lines) at pH (d) 5.5 (34.1 μM, 0.43 mg/mL), (e) 7.5 (36.5 μM, 0.46 mg/mL) and (f) 9.5 (32.6 μM, 0.41 mg/mL) are compared with those for samples incubated for 43 h (dashed lines), and also for 3 (dotted line) and 17 (dashed/dotted line) h at pH 9.5. At pH 9.5 and in the presence of higher BCA concentrations (c), Csp1 binds approximately one less equivalent of Cu(I) that must be due to changes in structure that are observed at this pH value (no change after 3 h but there is a decrease of ~ 15-20% α-helical content at longer incubation times, see f). However, the remaining sites bind Cu(I) more tightly (c) than at pH 7.5 (Fig. 4a) due to deprotonation of the Cys ligands37. g, Far-UV CD spectra of apo-Csp1 (19.9 μM, 0.25 mg/mL) in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 containing 200 mM NaCl at 0, 30, 60, 120, and 240 min (solid lines) after the addition of urea (7 M) compared to the spectrum for apo-Csp1 in the same buffer but with no urea (dashed line). h, Far-UV CD spectra of apo-Csp1 (7.94 μM, 0.10 mg/mL) as in (g) except that spectra were acquired at 0, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min (solid lines) after addition of urea (7 M); unfolding is significantly faster at lower protein concentrations and is consistent with the reaction with DTNB in urea being complete in 20 min at Csp1 concentrations < 4 μM. i, Far-UV CD spectra of Csp1 incubated with 14.0 equivalents of Cu(I) (19.9 μM, 0.25 mg/mL) as in (g) but at 0, 60, 240, 360, and 480 min and 24 h (solid lines) after addition of urea (7 M) compared to the spectrum for Cu(I)-Csp1 in buffer with no urea (dashed line). The arrow in g to i indicates how the spectrum changes with time.

Extended Data Figure 6 . Competition for Cu(I) between Csp1 and chromophoric ligands and the determination of the apparent average Cu(I) dissociation constant for Csp1 using BCS.

a, Plots of [Cu(L)2]3− concentration against [L] (BCA or BCS) after the incubation of Cu(I)-Csp1 (2.59 μM) loaded with 10.4 equivalents of Cu(I) with different concentrations of BCA (filled circles) and BCS (filled squares) for 17 h. b, Plots of [Cu(BCS)2]3− concentration against [Cu(I)] for apo-Csp1 (2.71 μM) in the presence of 99.2 (open squares) and 248 (filled squares) μM BCS incubated with increasing concentrations of Cu(I) (0, 4.38, 11.0, 15.3 and 21.9 equivalents; data shown after 17 h incubation). BCS competes much more effectively with Csp1 for Cu(I) than BCA and [Cu(BCS)2]3− is stoichiometrically formed at 248 μM BCS. c, Plot of [Cu(BCS)2]3− concentration against the [Cu(I)]/[Csp1] ratio for mixtures of Cu(I) plus apo-Csp1 (2.70 μM) in the presence of 101 μM BCS (open squares) for 19 h. For comparison the data from (b) (2.71 μM Csp1 in the presence of 99.2 μM BCS for 17 h) are also shown (filled squares). The data in a–c were all acquired in 20 mM Hepes plus 200 mM NaCl at pH 7.5. d, Fractional occupancy of Cu(I)-binding sites in Csp1 (maximum value is 11.3 equivalents in this experiment) at different concentrations of free Cu(I) for the experiment shown in (c). The solid line shows the fit of the data to the non-linear Hill equation giving KCu= (1.3 ± 0.1) × 10−17 M (n = 2.7 ± 0.2). Hill coefficients larger than 1 indicate positive cooperativity for Cu(I) binding by Csp1. Confirmation, and the cause, of this effect will be the subject of further studies.

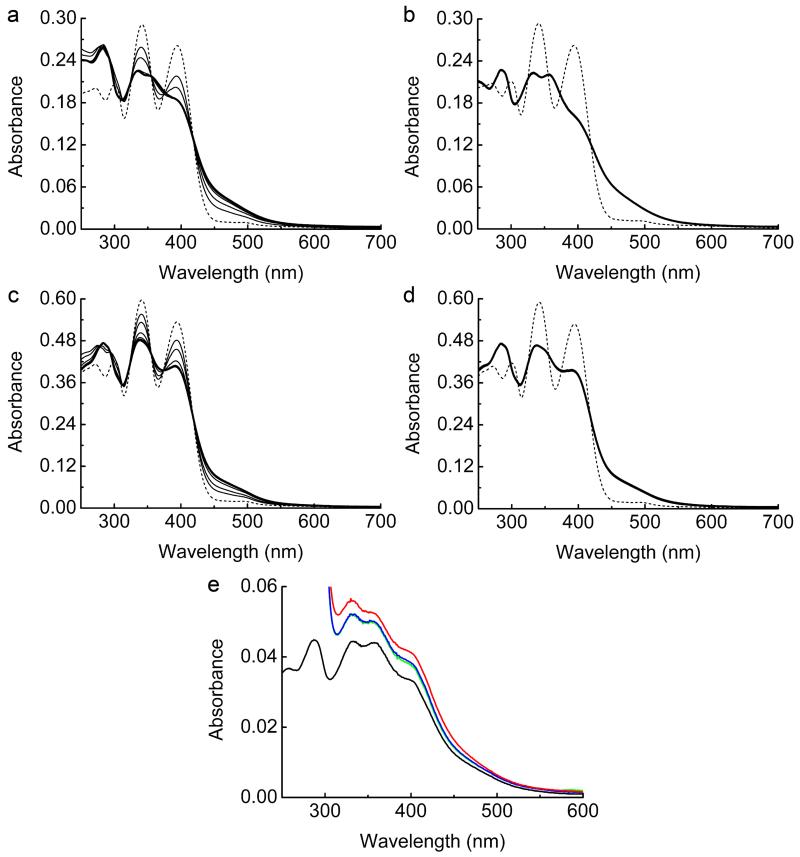

Extended Data Figure 7 . Cu(I) exchange between Csp1 and mbtin.

UV-Vis spectra of apo-mbtin (dashed lines) and at various times up to 360 min (thick lines) after the addition of either Cu(I)-Csp1 or Cu(I). Cu(I)-Csp1 (1.02 μM) loaded with 13.0 equivalents of Cu(I) was added to either 13.4 (a) or 27.4 (c) μM apo-mbtin. Cu(I) alone (13.3 μM) was added to 13.4 (b) or 27.1 (d) μM apo-mbtin. Plots of absorbance at 394 nm against time for (a) to (d) are shown in Fig. 4d. Mbtin from M. trichosporium OB3b has a Cu(I) affinity of (6-7) × 1020 M−1 at pH 7.5 (determined17 using a logβ2 value of 19.8 for [Cu(BCS)2]3−, but is an order of magnitude tighter if the more recent logβ2 value of 20.8 (25) is used) and stoichiometrically removes Cu(I) from Csp1 within 1 h. e, UV-Vis spectra of Cu(I)-mbtin (2.71 μM, black line) immediately after mixing with apo-Csp1 (234 μM, green line) and after incubation under anaerobic conditions for 1 (blue line) and 20 (red line) h. Small increases in absorbance are observed due to the absorbance of apo-Csp1 at these wavelengths and precipitation. The latter was more of a problem at longer incubation times and the sample at 20 h required filtering prior to running the spectrum shown. The small changes observed are not consistent with the formation of apo-mbtin17. All experiments were performed in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 plus 200 mM NaCl.

Extended Data Figure 8 . Sequence comparison of Csp homologues from diverse bacteria.

Homology searches show that Csp homologues are encoded in the genomes of diverse bacteria. Multiple sequence alignment of the three M. trichosporium OB3b proteins (OB3b Csp1, OB3b Csp2 and OB3b Csp3) with a selection of these proteins, including one member (from Neisseria gonorrhoeae) that also possesses a putative Tat signal sequence (underlined), shows that the Cys residues (highlighted in yellow) are highly conserved. The alignment was produced using the T-coffee alignment tool57. The * symbol indicates fully conserved sequence positions, whilst the : and . symbols indicate strongly and weakly similar sequence positions respectively. N. gonorrhoeae sequence: ORF NGAG_01502, UniProt accession C1I025; Pseudomonas aeruginosa sequence: ORF PA96_2930, UniProt accession X5E748 (PDB ID 3KAW); Streptomyces coelicolor sequence: ORF SCO3281, UniProt accession Q9X8F4; Nitrosospira multiformis sequence: ORF NmuI_A1745, UniProt accession Q2Y879 (PDB ID 3LMF); Rhizobium leguminosarum sequence: ORF RLEG_20420, UniProt accession W0IHZ3; Ralstonia metallidurans sequence: ORF Rmet_5753, UniProt accession Q1LB64; Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium sequence: ORF STM14_1521, UniProt accession D0ZVJ6; Bacillus subtilis sequence: ORF BSU10600, UniProt accession O07571; Legionella pneumophila sequence: ORF LPE509_p00081, UniProt accession M4SK87.

Extended Data Table 1 . Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Apo-Csp1 | Cu(I)-Csp1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P21 | P2 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 40.9, 105.9, 48.7 | 44.4, 41.4, 53.1 |

| α β, γ(°) | 90.0, 112.5, 90.0 | 90.0, 92.6, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 44.95-1.50 (1.53-1.50)* | 53.06-1.90 (1.95-1.90) |

| Rmerge (%) | 7.0 (50.5) | 8.7 (43.3) |

| I/σI | 10.9 (2.6) | 5.6 (2.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (99.8) | 99.1 (97.1) |

| Redundancy | 3.7 (3.7) | 2.8 (2.4) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 1.50 | 1.90 |

| No. reflections | 60896 (3056) | 15212 (990) |

| Rwork/ Rfree | 12.2/17.9 | 19.8/23.2 |

| No. atoms | ||

| Protein | 3209 | 1575 |

| Ligand/ion | 0 | 28 |

| Water | 406 | 116 |

| B-factors | ||

| Protein | 16.2 | 40.2 |

| Ligand/ion | 41.4 | |

| Water | 27.0 | 47.7 |

| R.m.s deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.020 | 0.016 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.8 | 1.6 |

Highest resolution shell is shown in parenthesis.

Extended Data Table 2 . Primers used for cloning Cspl and making the Δcsp1/csp2 M. trichosporium OB3b strain.

| Primer | Sequence (5’ to 3’)* |

|---|---|

| Csp1_F | GCGCATATGGGAGAGGATCCTCATGC |

| Cspl_R | GCGCCATGGTCAGGCGGCGACCTTATGGC |

| 684AF | ATATCCCGGGTAAGGGTGAAG ACCGCCATCAG |

| 684AR | GATCGTCGACACGACGGACGCAACCTAAAC |

| 684BF | GATCGTCGACTAAGGTCGCCGCCTGAGTTC |

| 684BR | GATCAAGCTTCGCGCTCGCGTCCGTATTC |

| 1592AF | CATCAAGCTTCGGTGCGCGACATCATCCTC |

| 1592AR | CATCCTGCAGTGGTCGTTCCTCTCGTGTTC |

| 1592BF | TAATGGATCCCAGCGCGTGTCGAGCTGAAC |

| 1592BR | ATTAGAATTCGCGGAGCCCGCGTGGAAAG |

| 684TF | CACATGCAGGCGGTAGATCG |

| 684TR2 | CGACCAGCAGGATCATCAG |

| 1592TF | ACCCTTCTCACGCAATCCC |

| 1592TR | ACGTTGATCGGCCTCACTC |

Introduced restriction sites are underlined when relevant.

Acknowledgments

We thank staff of the Diamond Light source for help with diffraction data collection, Dr. Joe Gray for performing MS studies, the School of Civil Engineering & Geosciences and Prof. David Graham for access to facilities at the very start of this work, Dr. Adriana Badarau for discussions about determining Cu(I) affinities and Dr. Susan Firbank for structural modelling at the initial stages of this project. This work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant BB/K008439/1 to C.D. and K.J.W.) and Newcastle University (part-funding of a PhD studentship for S.P.). K.J.W. was supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (098375/Z/12/Z).

Footnotes

Author information Atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes (5AJE and 5AJF) for apo- and Cu(I)-Csp1 respectively.

References

- 1.Hanson RS, Hanson TE. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;60:439–471. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.439-471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian R, et al. Oxidation of methane by a biological dicopper centre. Nature. 2010;465:115–119. doi: 10.1038/nature08992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murrell JC, McDonald IR, Gilbert B. Regulation of expression of methane monooxygenases by copper ions. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:221–225. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01739-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakemian AS, Rosenzweig AC. The biochemistry of methane oxidation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:223–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061505.175355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang H, et al. Methanotrophs: multifunctional bacteria with promising applications in environmental bioengineering. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010;49:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haynes CA, Gonzalez R. Rethinking biological activation of methane and conversion to liquid fuels. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma Z, Jacobsen FE, Giedroc DP. Coordination chemistry of bacterial metal transport and sensing. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:4644–4681. doi: 10.1021/cr900077w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Festa RA, Thiele DJ. Copper: an essential metal in biology. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:R877–R883. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Argüello JM, Raimunda D, Padilla-Benavides T. Mechanisms of copper homeostasis in bacteria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013;3:73. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poutney DL, Schauwecker I, Zarn J, Vašák M. Formation of mammalian Cu8-metallothionein in vitro: evidence for the existence of two Cu(I)4-thiolate clusters. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9699–9705. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calderone V, et al. The crystal structure of yeast copper thionein: the solution of a long-lasting enigma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:51–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408254101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland DEK, Stillman MJ. The “magic numbers” of metallothionein. Metallomics. 2011;3:444–463. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00102c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold B, et al. Identification of a copper-binding metallothionein in pathogenic bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:609–616. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies SL, Whittenbury R. Fine structure of methane and other hydrocarbon-utilising bacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1970;61:227–232. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-2-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed WM, Titus JA, Dugan PR, Pfister RM. Structure of Methylosinus trichosporium exospores. J. Bacteriol. 1980;141:908–913. doi: 10.1128/jb.141.2.908-913.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HJ, et al. Methanobactin, a copper-acquisition compound from methane-oxidizing bacteria. Science. 2004;305:1612–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.1098322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Ghazouani A, et al. Copper-binding properties and structures of methanobactins from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:1378–1391. doi: 10.1021/ic101965j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Ghazouani A, et al. Variations in methanobactin structure influence copper utilization by methane-oxidizing bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:8400–8404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112921109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balasubramanian R, Kenney GE, Rosenzweig AC. Dual pathways for copper uptake by methanotrophic bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37313–37319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.284984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semrau JD, et al. Methanobactin and MmoD work in concert to act as the ‘copper-switch’ in methanotrophs. Environ. Micobiol. 2013;15:3077–3086. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein LY, et al. Genome sequence of the obligate methanotroph Methylocystis trichosporium strain OB3b. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:6497–6498. doi: 10.1128/JB.01144-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrow CJ, Yasuda A, Kenny PTM, Zagorski MG. Solution conformations and aggregational properties of synthetic amyloid β-peptides of Alzheimer’s Disease. Analysis of circular dichroism spectra. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;225:1075–1093. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90106-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cobine PA, et al. Copper transfer from the Cu(I) chaperone, CopZ, to the repressor, Zn(II)CopY: metal coordination environments and protein interactions. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5822–5829. doi: 10.1021/bi025515c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Badarau A, Firbank SJ, McCarthy AA, Banfield MJ, Dennison C. Visualizing the metal-binding versatility of copper trafficking sites. Biochemistry. 2010;49:7798–7810. doi: 10.1021/bi101064w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bagchi P, Morgan MT, Bacsa J, Fahrni CJ. Robust Affinity Standards for Cu(I) Biochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:18549–18559. doi: 10.1021/ja408827d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kau LS, Spira-Solomon DJ, Penner-Han JE, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. X-ray absorption edge determination of the oxidation state and coordination number of copper: applications to the type 3 site in Rhus vernicifera laccase and its reaction with oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:6433–6442. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Theil EC. Ferritin protein nanocages use ion channels, catalytic sites, and nucleation channels to manage iron/oxygen chemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2011;15:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kharenko OA, Kennedy DC, Demeler B, Maroney MJ, Ogawa MY. Cu(I) luminescence from the tetranuclear Cu4S4 cofactor of a synthetic 4-helix bundle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:7678–7679. doi: 10.1021/ja042757m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer T, Berks BC. Moving folded proteins across the bacterial cell membrane. Microbiology. 2003;149:547–556. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.25900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tottey S, et al. Protein-folding location can regulate manganese-binding versus copper- or zinc-binding. Nature. 2008;455:1138–1142. doi: 10.1038/nature07340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hellman U, Wernstedt C, Gonez J, Heldin CH. Improvement of an “In-Gel” digestion procedure for the micropreparation of internal protein fragments for amino acid sequencing. Anal. Biochem. 1995;224:451–455. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, Widdick D, Palmer T, Brunak S. Prediction of twin-arginine signal peptides. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riddles PW, Blakeley RL, Zerner B. Ellman’s reagent: 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) - a re-examination. Anal. Biochem. 1979;94:75–81. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riener CK, Kada GH, Gruber J. Quick measurement of protein sulfhydryls with Ellman’s reagent and with 4,4′-dithiodipyridine. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002;373:266–276. doi: 10.1007/s00216-002-1347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen S, Badarau A, Dennison C. Cu(I) affinities of the domain 1 and 3 sites in the human metallochaperone for Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 2012;51:1439–1448. doi: 10.1021/bi201370r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Badarau A, Dennison C. Thermodynamics of copper and zinc distribution in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:13007–13012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101448108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Badarau A, Dennison C. Copper trafficking mechanism of CXXC-containing domains: insight from the pH-dependence of their Cu(I) affinities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2983–2988. doi: 10.1021/ja1091547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao Z, Donnelly PS, Zimmerman M, Wedd AG. Transfer of copper between bis(thiosemicarbazone) ligands and intracellular copper-binding proteins. Insights into mechanisms of copper uptake and hypoxia selectivity. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:4338–4347. doi: 10.1021/ic702440e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao Z, Loughlin F, George GN, Howlett GJ, Wedd AG. C-terminal domain of the membrane copper transporter Ctr1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae binds four Cu(I) ions as a cuprous-thiolate polynuclear cluster: sub-femtomolar Cu(I) affinity of three proteins involved in copper trafficking. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3081–3090. doi: 10.1021/ja0390350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banci L, et al. Affinity gradients drive copper to cellular destinations. Nature. 2010;465:645–648. doi: 10.1038/nature09018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen S, Badarau A, Dennison C. The influence of protein folding on the copper affinities of trafficking and target sites. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:3233–3239. doi: 10.1039/c2dt32166a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans PR, Murshudov GN. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013;69:1204–1214. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evans PR. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheldrick GM. Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:479–485. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909038360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cowtan K. Recent developments in classical density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:470–478. doi: 10.1107/S090744490903947X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 1):12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schäfer A, et al. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene. 1994;145:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotech. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stafford GP, Scanlan J, McDonald IR, Murrell JC. rpoN, mmoR and mmoG, genes involved in regulating the expression of soluble methane monooxygenase in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Microbiology. 2003;149:1771–1784. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brusseau GA, Tsien H-C, Hanson RS, Wackett LP. Optimization of trichloroethylene oxidation by methanotrophs and the use of a colorimetric assay to detect soluble methane monooxygenase activity. Biodegradation. 1990;1:19–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00117048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xie F, Sutherland DEK, Stillman NJ, Ogawa MY. Cu(I) binding properties of a designed metalloprotein. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010;104:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]