Abstract

Alcohol consumption contributes to increased incidence and severity of traumatic injury. Compared with patients who do not consume alcohol, alcohol-consuming patients have higher rates of long-term morbidity and mortality during recovery from injury. This can be attributed in part to an impaired immune response in individuals who consume alcohol. Acute and chronic alcohol use can affect both the innate and adaptive immune defense responses within multiple organ systems; the combination of alcohol use and injury results in increased susceptibility to bacterial and viral pathogens. This review examines the major deleterious effects of alcohol on immunity following tissue damage or traumatic injury, with a focus on alcohol’s influence on the ability of the immune and major organ systems to fight disease and to repair damaged tissues following injury.

Keywords: Alcohol consumption; alcohol use, abuse, and dependence; chronic alcohol use; acute alcohol use; injury; traumatic injury; morbidity; mortality; immune response; impaired immune response; bacterial pathogens; viral pathogens; tissue; organs; disease

The incidence of traumatic injury in alcohol-intoxicated individuals continues to escalate. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012a), more than 38 million American alcohol users consume 5 or more drinks on the same occasion (i.e., binge drink) and do so about 4 times per month. This behavior is highly conducive to unintentional or accidental traumatic injury, which according to the National Vital Statistics Reports is the leading cause of years of potential life lost (YPLL) before age 45. Unintentional injury causes more YPLL than that attributed to cancer, intentional injuries, heart disease, and HIV individually (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009). Data from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, as well as data derived from prospective and retrospective studies, show that up to 40 percent of victims of traumatic injury have positive blood alcohol concentrations (BAC), with 35 percent presenting with blood alcohol levels above the legal limit of intoxication (Beech and Mercadel 1998).

The severity of trauma, reduced blood flow and oxygen delivery (i.e., hemorrhagic shock, referred to as shock in this article), and tissue injury is greater in intoxicated victims than in sober victims, resulting in higher mortality rates in the alcohol-consuming patient population (Pories et al. 1992). Although immediate mortality from traumatic injury has improved significantly as a result of aggressive resuscitation, long-term morbidity and mortality continue to be unacceptably high during the recovery period. The prevalence of morbidity and mortality is particularly attributable to the altered immune response among impaired patients to subsequent challenges, such as surgery or infection, leading to multiple organ failure (Roumen et al. 1993; Sauaia et al. 1994). Acute alcohol intoxication complicates the initial management of trauma victims and is associated with greater incidences of pneumonia and respiratory distress, requiring ventilator assistance during hospitalization (Gurney et al. 1992; Jurkovich et al. 1992). In addition, major complications including tracheobronchitis, pneumonia, pancreatitis, and sepsis are significantly increased in patients with high levels of carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT), a marker for alcoholism (Spies et al. 1998). European studies show that, compared with nonalcoholics, alcoholics more frequently develop major complications and require a significantly prolonged stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) following trauma (Spies et al. 1996a).

Excessive acute and chronic alcohol consumption has significant effects at multiple cellular levels, affecting both innate and adaptive immune mechanisms (Molina et al. 2010). Both chronic and acute patterns of alcohol abuse lead to impaired immune responses, resulting in increased susceptibility to infectious diseases caused by bacterial and viral pathogens (Brown et al. 2006). Clinical and preclinical studies show that the combined effects of alcohol and injury result in greater immune disruption than either insult alone (Messingham et al. 2002). This article reviews the current understanding of the burden of alcohol on the immune response to three specific traumatic events: burn, shock, and traumatic brain injury (TBI). The major pathophysiological consequences of these injuries on other major organ systems— including the cardiovascular system, pulmonary system, and gastrointestinal tract—are highlighted with emphasis on the contribution of alcohol-induced immunomodulation to postinjury morbidity.

Reestablishment of homeostasis after a traumatic insult involves activation of host defense mechanisms for self-protection against toxic inflammatory processes and tissue repair. Trauma victims frequently are subjected to necessary invasive procedures, such as surgery and anesthesia. In addition, trauma victims frequently are exposed to subsequent challenges, particularly infection. These additional stresses to an already compromised inflammatory and neuroendocrine milieu further contribute to morbidity and mortality in this patient population. Traumatic injury and hemorrhagic shock produce a temporal pattern with early upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine1 gene product expression and with later suppression of stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine release (Hierholzer et al. 1998; Molina et al. 2001). Together, these alterations lead to generalized immunosuppression, ultimately resulting in an increased susceptibility to infection (Abraham 1993; Ertel et al. 1993).

Alcohol has been shown to affect multiple aspects of the host immune response, contributing to pathological processes (Szabo 1998). For example, alcohol alters the expression and processing of cytokines and a type of cytokine known as chemokines (D’Souza et al. 1989; Standiford and Danforth 1997), the expression of adhesion molecules (Zhang et al. 1999), inflammatory cell recruitment (Patel et al. 1996; Shellito and Olariu 1998) and accumulation, and oxidative capacity of macrophages (Nilsson and Palmblad 1988). The monocyte/macrophage production of cytokines and chemokines, in particular interleukin (IL)-8 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), is critical in the regulation of the acute inflammatory host response to infectious challenge. The combined inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine production and neutrophil activation and migration to a site of infection has been suggested to contribute to the enhanced susceptibility to infection in alcoholic individuals (Nelson et al. 1991) and to the increased risk of trauma- and burn-related infections associated with alcohol intoxication (Arbabi et al. 1999). Several lines of evidence show that these alcohol-mediated alterations in host defense following injury lead to increased morbidity and mortality from infections during the recovery period (Faunce et al. 2003; Messingham et al. 2002; Zambell et al. 2004). In addition, considerable evidence suggests that the severity of disease processes is greater in intoxicated trauma victims than in nonintoxicated counterparts (Spies et al. 1996a,b, 1998). In particular, immunoparalysis characterized by inhibition of stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine release (Angele et al. 1999) and alterations of both cellular and humoral immunity (Napolitano et al. 1995; Wichmann et al. 1998) have been identified as risk factors for infection and progression to organ injury during the posttraumatic injury period (Abraham 1993; Ertel et al. 1993).

The systemic response to injury is associated with marked activation of neuroendocrine pathways that contribute to cardiovascular adaptation to blood loss, injury, and pain but also exert immunomodulatory effects (Molina 2005). Catecholamines (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine), and drugs that mimic their effects (i.e., adrenergic agonists), are especially known to exert important regulatory functions on macrophages as well as on B- and T-lymphocyte cytokine production, proliferation, and antibody secretion; dendritic cell function; cytokine and chemokine release; and nitric oxide (NO) production (Madden et al. 1995). The relevance of these control mechanisms and the implications of their dysregulation have been demonstrated by the high incidence of infection in patients who experience elevated temperature, increased heart rate, and perspiration (i.e., “sympathetic storm”) following acute brain trauma and myocardial infarction (Woiciechowsky et al. 1998). Alcohol intoxication produces marked disruption of several neuroendocrine pathways. Disruption of the homeostatic neuroendocrine counterregulatory response to shock impairs hemodynamic stability and recovery, contributing to compromised blood flow and increased end-organ injury (Molina et al. 2013). Specifically, binge alcohol use blunts central neuroendocrine and autonomic activation, and this seems to result from alcohol-accentuated NO production in the periventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus (Whitaker et al. 2010). Alcohol-mediated impairment of neuroendocrine counterregulatory responses to traumatic injury not only exacerbates low blood pressure (i.e., hypotension) during hemorrhage but also attenuates blood pressure recovery during fluid resuscitation, leading to significant alterations in blood flow redistribution and notably affecting circulation in the gastrointestinal tract (Wang et al. 1993). Studies have shown that alcohol-intoxicated animals have greater reduction of blood flow to the liver, kidney, and small and large intestines than nonintoxicated animals, following shock and fluid resuscitation (Sulzer et al. 2013). These macro- and microcirculatory changes during trauma and hemorrhage have been implicated in the subsequent development of sepsis and multiple organ failure (Peitzman et al. 1995) and contribute to an increased host susceptibility to infection and tissue injury during recovery (Mathis et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2002). People who abuse alcohol, including both binge and chronic drinkers, have a higher incidence of traumatic injury such as burn, shock, and TBI. The host response to these diverse insults is markedly affected by both patterns of alcohol abuse and some systems—including gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and pulmonary— are more affected than others according to the specific injury.

Alcohol and Burn Injury

Burn injury is a common type of traumatic injury that affects thousands of people in the United States every year (Bessey et al. 2014). Approximately 50 percent of burn-injured patients have detectable blood alcohol levels at the time of hospital admission (Haum et al. 1995; McGwin et al. 2000), and these patients have more complications, require longer hospital stays, and have greater mortality rates than those with a similar degree of injury who are not intoxicated at the time of injury (McGill et al. 1995). Most morbidity and mortality among patients who survive initial injury is attributed to complications stemming from infection (Baker et al. 1980). Therefore, the pre-burn immunological condition of injured patients affects susceptibility to infection and survival. Several mechanisms contribute to infection in burn patients, including loss of barrier function, changes in normal flora, wound ischemia, and cellular immunosuppression resulting from pro-inflammatory processes. Neutrophil, helper T-cell, and macrophage dysfunction; increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production; and enhanced production of immunosuppressive factors have all been shown to contribute to the pathophysiological response to burn injury (Faunce et al. 1998; Messingham et al. 2000). The mechanisms that contribute to infection in burn patients are influenced by acute and chronic alcohol intoxication and will be discussed below (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Salient gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and metabolic pathophysiological consequences of alcohol abuse prior to, or at the time of, burn injury. The decrease in gut barrier function leads to increased permeability and bacterial translocation that enhances the risk for bacterial infections and lung injury. Marked alterations in metabolic responses, characterized by altered adipokine profile consistent with increased insulin resistance, collectively contribute to greater morbidity and mortality post–burn injury.

Research by Kovacs and colleagues (2008) has offered insight into the combined effects of burn injury and alcohol intoxication on immunity (Bird and Kovacs 2008). Chronic alcohol abuse alone increases the risk for lung infection (Baker and Jerrells 1993), impairs the phagocytic activity of alveolar macrophages and clearance of infectious particles from the airways, and impairs oxidant radicals, chemokine, and cytokine release that are required for microbial killing (Brown et al. 2007; Mehta and Guidot 2012; Molina et al. 2010). Acute alcohol intoxication prior to burn injury significantly suppresses the immune response relative to the insult alone (Faunce et al. 1997) and causes greater suppression of T-cell proliferation and response, reduced IL-2 production, and increased IL-6 production and circulating levels (Choudhry et al. 2000; Faunce et al. 1998). The T-cell and cytokine impairment caused by the combined effect of alcohol and burn injury may further suppress cell-mediated immunity, resulting in even greater susceptibility to infection than burn alone. Alcohol-mediated immunomodulation contributes to tissue injury in target organs as described below.

Gastrointestinal Tract

A multitude of studies have demonstrated that the gut is a reservoir for pathogenic bacteria, which may contribute to increased susceptibility to infections following traumatic injury (Deitch 1990). The intestinal mucosal barrier serves a major role in the local defense against bacterial entry and the translocation of endotoxin to the systemic circulation (Xu et al. 1997). Increased permeability and immune dysfunction indicate the compromised state of the intestinal mucosal barrier to bacterial translocation following trauma (Deitch et al. 1990; Willoughby et al. 1996). Increased intestinal permeability enhances bacterial and endotoxin translocation from the intestinal tract to the systemic circulation, triggering a systemic inflammatory response (Xu et al. 1997). Activated macrophages and lymphocytes release pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, thereby contributing to tissue injury (Fink 1991). Studies have determined that chronic alcohol consumption disrupts intestinal barrier function and induces gut leak (Li et al. 2008; Tang et al. 2009). In addition, reports have shown a loss of intestinal barrier function followed by an increase in endotoxin and bacterial translocation to the systemic circulation following burn injury alone (Carter et al. 1990; Deitch and Berg 1987; Horton 1994), alcohol intoxication alone (Keshavarzian et al. 1994; Tabata et al. 2002), and burn injury with alcohol intoxication (Choudhry et al. 2002; Kavanaugh et al. 2005; Napolitano et al. 1995). Acute alcohol intoxication at the time of burn injury enhances bacterial growth in the intestine and is reflected in a proportional increase in mesenteric lymph node bacterial count (Kavanaugh et al. 2005). Acute alcohol intoxication also modulates intestinal immune defense by suppressing T-cell proliferation and increasing bacterial accumulation in mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, and blood, which suggests that T-cell suppression may play a role in bacterial translocation from the lumen of the gut (Choudhry et al. 2002). Moreover, studies have shown that following shock, trauma, or burn injury, the gut leaks bacteria and pro-inflammatory factors that are carried by the mesenteric lymphatic system, which contributes to acute lung injury (ALI) (Magnotti et al. 1999). The possibility that alcohol exacerbates toxin delivery to the systemic circulation through the lymphatics is supported by studies demonstrating that alcohol regulates the contractile cycle of mesenteric lymphatic vessels modulating the driving force of lymph flow (Keshavarzian et al. 1994; Souza-Smith et al. 2010). Thus, the contribution of gut–lymph to end-organ damage following burn injury and alcohol intoxication may be significant.

Collectively, studies indicate that alcohol consumption preceding burn injury (1) increases gut permeability; (2) enhances intestinal bacterial growth, translocation, and systemic accumulation; and (3) suppresses T-cell proliferation. Further, research supports the concept that the intestine is not only a source of infection but also the site of the initial immune perturbation leading to the development of multiple organ dysfunction or organ failure.

Cardiovascular System

Immediately following a burn injury, the cardiovascular system responds with a decrease in cardiac output (Cuthbertson et al. 2001) as a result of low blood volume and reduced venous return (Kramer et al. 2007). This phase is associated with decreased cardiac contractility, mediated by the release of vasoactive and pro-inflammatory mediators (Williams et al. 2011). Subsequently, there is a surge in counterregulatory neuroendocrine mediators (catecholamines, glucagon, and cortisol) that contribute to the development of a hyperdynamic cardiovascular state—characterized by increased heart rate and cardiac output—and is associated with increased myocardial oxygen consumption and myocardial hypoxia (Williams et al. 2011). These pathophysiological processes enhance oxidative metabolism and increase the risk for free-radical generation, further exacerbating the pro-oxidative environment that has been proposed to contribute to impaired wound healing in burn patients (Herndon and Tompkins 2004). Chronic binge alcohol consumption also has been shown to promote a pro-oxidative and pro-inflammatory milieu (Rashbastep et al. 1993), and these factors may further impede wound healing in patients consuming alcohol prior to experiencing burn injury. Additional research is needed to better understand immunomodulation effects following the combined insults of alcohol and burn injury and the mechanisms underlying the more severe outcome of burn injury with alcohol abuse.

Pulmonary System

Adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a frequent cause of death in burn patients. The lungs are one of the first organs to fail following traumatic injury (Turnage et al. 2002). Chronic and acute alcohol abuse impair pulmonary host defense to infection, thus increasing the risk of bacterial infection and acute lung injury (Boe et al. 2009; Happel and Nelson 2005). Lung injury as a result of the combination of alcohol intoxication and burn injury may be attributed to the delicate architecture of the lungs combined with other alcohol-related factors, such as bacterial and endotoxin leakage from the gut and a higher risk of contact with pathogens from the circulation and airways (Bird and Kovacs 2008; Li et al. 2007). Previous studies show that the combined insult of acute alcohol consumption and burn injury in mice leads to increased infiltration of the lungs by white blood cells, called neutrophils, and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression of IL-6 (Chen et al. 2013). Systemic and pulmonary IL-6 reflect the inflammatory state of the host and have been shown to be decreased in the absence of Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (Bird et al. 2010). The role of IL-6 in lung injury has been demonstrated in studies in IL-6 knockout mice or following neutralization of IL-6, both of which result in significantly reduced lung inflammation (Chen et al. 2013). Studies also have shown that acute alcohol intoxication at the time of burn injury induces an upregulation of IL-18 production and neutrophil infiltration within the lung compartment, all leading to pulmonary edema (Li et al. 2007).

Metabolism

The post-burn period is characterized by a hypermetabolic state (Pereira and Herndon 2005) consisting of increased oxygen consumption; increased breakdown of glycogen, fats, and proteins; elevated resting energy expenditure and glucose synthesis; and reduced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake into skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (Gauglitz et al. 2009). Previous studies suggest that development of this hypermetabolic state during the post-burn period occurs as a consequence of (1) increased plasma catecholamine and corticosteroid concentrations (Jeschke et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2009; Wilmore and Aulick 1978), (2) increased systemic pro-inflammatory mediator expression, favoring processes that release energy (i.e., catabolic) over those that store energy (i.e., anabolic) (Jeschke et al. 2004), and (3) increased adipose tissue mRNA (Zhang et al. 2008) and protein (Yo et al. 2013) expression of uncoupling protein-1 (UCP-1), enhancing heat production and metabolism. Further, circulating levels of TNF-α, a known anti-insulin cytokine, are increased (Keogh et al. 1990), and the post-burn period can be described as a state of marked insulin resistance (IR) (Gauglitz et al. 2009). Insulin sensitivity has been reported to be decreased by more than 50 percent at 1-week post–burn injury in pediatric patients (Cree et al. 2007) as well as in rodent models of burn injury (Carter et al. 2004). The relevance of insulin levels to overall outcome from burn injury is supported by results from clinical studies showing that exogenous insulin therapy in pediatric burn patients decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines, increased anti-inflammatory cytokines, and increased serum concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3). Together, these changes could help to preserve organ function and better promote anabolic processes during the post-burn hypermetabolic state (Jeschke et al. 2004). Chronic alcohol consumption decreases insulin responsiveness and can alter insulin signaling through various mechanisms, including increased hepatic protein expression of the gene phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN), which directly inhibits insulin signaling through the phosphatidylinositol-5,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathway (de la Monte et al. 2012). In addition to the negative regulation of the pathway by PTEN proteins, the enzyme protein tyrosine phosphatase dephosphorylates and decreases activity of important molecules involved in the insulin signaling cascade, potentially contributing to impaired insulin action (Gao et al. 2010; Koren and Fantus 2007). In addition, Lang and colleagues (2014) demonstrated that chronic alcohol consumption reduces Akt and AS160 phosphorylation, reduces membrane localization of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT-4) protein, and increases serine phosphorylation at serine-307 of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), all of which will attenuate insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle glucose uptake and other insulin-mediated anabolic effects (Lang et al. 2014). These negative effects on insulin signaling occurred in conjunction with sustained increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 following chronic alcohol exposure (Lang et al. 2014). Thus, both burn injury and chronic alcohol exposure alter metabolic pathways—favoring catabolic and opposing anabolic pathways—possibly resulting in long-lasting alterations in metabolic processes. The metabolic dysregulation following burn injury is likely to produce more severe consequences in chronic alcohol burn victims. Previous studies assessing nutritional status of alcoholic patients have been discordant, with some studies suggesting that increased alcohol consumption increases the prevalence of malnutrition in alcoholic patients (Hillers and Massey 1985), whereas other studies do not show a role for excessive, or chronic, alcohol consumption in malnutrition (Nicolas et al. 1993; Urbano-Marquez et al. 1989). A study assessing the influences of aging and chronic alcohol feeding in mice on protein synthesis demonstrated that chronic alcohol feeding decreases gastrocnemius muscle protein synthesis, which provides a mechanism for loss of lean body mass (Korzick et al. 2013; Lang et al. 2014). Decreased anabolism during the post-burn period, which itself is a state of heightened catabolic processes, could significantly impair recovery for these alcoholic patients experiencing burn injury. Further, the hypermetabolic state of the post-burn period is thought to contribute to delayed or impaired wound healing, increased susceptibility to infections, and erosion of lean body mass (Pereira and Herndon 2005). Moreover, both binge alcohol consumption (Pravdova and Fickova 2006; You and Rogers 2009) and burn injury (Venkatesh et al. 2009; Wade et al. 2013) can contribute to dysregulation of cytokines secreted by adipose tissue (i.e., adipokines). Recent studies show that mice exposed to a single alcohol binge prior to burn injury have a dramatic increase in pro-inflammatory response and a decrease in anti-inflammatory response in adipose tissue (Qin et al. 2014). The heightened pro-inflammatory response during the post-burn period would be predicted to modulate leptin levels. Thus, recovery from burn injury is likely to be severely impaired in alcoholic individuals as a result of a greater disruption in metabolic processes as well as impairment of host defense mechanisms, leading to greater morbidity and health care costs associated with the management of these patients. Therefore, further investigation is warranted to understand the modulation of the immune system by the combined effect of alcohol and burn that might result in dysregulation of adipose tissue and altered metabolism.

Alcohol and Hemorrhagic Shock

Studies from several investigators have provided evidence that traumatic injury and hemorrhagic shock produce an immediate upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine gene product expression (Ayala et al. 1991; Hierholzer et al. 1998). The early pro-inflammatory response is later followed by suppression of stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine release (Angele et al. 1999; Xu et al. 1998) and alterations of both cellular and humoral immunity (Napolitano et al. 1995; Wichmann et al. 1998), leading to generalized immunosuppression, which ultimately results in an increased susceptibility to infection (Abraham 1993; Ertel et al. 1993). Along with marked alterations in hemodynamic homeostasis and neuroendocrine regulation, immunological derangements and subsequent infections are also a major cause of increased morbidity and mortality following hemorrhagic shock (Livingston and Malangoni 1988; Phelan et al. 2002).

Studies focused on the immune modulatory effects of alcohol exposure following hemorrhagic shock have demonstrated that even 24 hours after the post-hemorrhagic shock, alcohol-intoxicated animals had a marked suppression in cytokine release to an inflammatory challenge (Greiffenstein et al. 2007), affecting the ability to fight secondary infectious challenges. Conversely, findings observed at the tissue level determined that alcohol intoxication enhanced the pro-inflammatory milieu following hemorrhagic shock, priming tissues for injury. The burden of alcohol and hemorrhagic shock on specific target organ systems is discussed below and summarized in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Salient gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and neuroendocrine pathophysiological consequences of alcohol abuse prior to, or at the time of, hemorrhagic shock. The decreased hemodynamic counterregulatory response leads to decreased tissue perfusion, accentuated oxidative stress, and enhanced tissue injury. In addition, the alcohol/hemorrhaged host shows greater susceptibility to secondary infections leading to increased morbidity and mortality during the post-injury period.

Gastrointestinal Tract

Hemorrhagic shock produces similar alterations in gut barrier function to those resulting from burn injury. Alcohol intoxication at the time of hemorrhagic shock further exacerbates hemorrhagic injury-induced gut permeability and leakage (Sulzer et al. 2013). Chronic alcohol consumption has been shown to disrupt intestinal barrier function and induce gut leak (Li et al. 2008; Tang et al. 2009). The combination of greater hypotension and inadequate tissue blood flow (i.e., hypoperfusion) observed in alcohol-intoxicated animals and the increased gut leak observed in alcohol-intoxicated hemorrhaged animals are speculated to contribute to increased host susceptibility to infection and tissue injury during recovery (Molina et al. 2013). Alcohol-intoxicated, hemorrhaged animals have been shown to have greater reduction in hepatic, renal, and intestinal blood flow than that observed in nonintoxicated animals (Sulzer et al. 2013). This reduction in critical organ blood flow was associated with enhanced tissue damage. An additional mechanism that could contribute to tissue injury in the alcohol-intoxicated, hemorrhaged host is the disruption of gut-associated lymphoid tissue function, which has been shown to play a role in other disease states.

Cardiovascular System

Studies using a rodent model of binge-like alcohol consumption prior to hemorrhagic shock have shown that acute alcohol intoxication decreases basal mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), exacerbates hypotension, and attenuates blood pressure recovery during fluid resuscitation (Mathis et al. 2006; Phelan et al. 2002). Following fixed-volume hemorrhage, alcohol-intoxicated animals were significantly more hypotensive throughout the hemorrhage and resuscitation periods (Mathis et al. 2006). In response to a fixed-pressure (40 mmHg) hemorrhage, a significantly lesser amount of blood was removed from the alcohol-intoxicated animals than controls (Phelan et al. 2002). Similarly, McDonough and colleagues, using a guinea pig model of ethanol exposure prior to hemorrhagic shock (loss of 60% blood volume) and resuscitation, demonstrated that a low dose of ethanol (1 g/kg) decreases MABP and heart rate and exacerbates the metabolic effects of hemorrhagic shock, as shown by increased glucose and lactate concentrations (McDonough et al. 2002). Despite the plethora of previous studies that have examined functional cardiovascular consequence of hemorrhagic shock and hemorrhage with alcohol intoxication, few studies have examined the combined effects of alcohol, hemorrhagic shock, and immune dysfunction on the cardiovascular system. However, exacerbation of pre-existing cardiovascular disease and prolonged recovery are anticipated outcomes of the combined effects of alcohol and hemorrhagic shock, all leading to an impaired immune response.

Pulmonary System

As mentioned previously, alcohol intoxication produces significant dysregulation of the host defense mechanism during the post-injury period. Lung IL-6 and TNF-α are suppressed, while granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF) mRNA is increased in alcohol-intoxicated, hemorrhaged animals (Mathis et al. 2006; Ono et al. 2004). Moreover, isolated pleural cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from alcohol-intoxicated, hemorrhaged animals display suppressed TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 release following lipopolysaccharide stimulation (Greiffenstein et al. 2007), suggesting greater impairment of humoral immune response than that resulting from hemorrhagic shock alone. The importance of these alterations in host defense mechanisms was demonstrated in animals inoculated with Klebsiella pneumonia following hemorrhagic shock. These studies showed suppressed neutrophil response, decreased phagocytic activity, and increased neutrophil apoptosis in hemorrhaged animals that were alcohol intoxicated at the time of injury (Zambell et al. 2004). This was associated with greater lung bacterial counts and prolonged elevation in TNF-α and IL-6 levels (18 h) post-infection. Furthermore, only 30 percent of alcohol-intoxicated, hemorrhaged animals survived compared with 70 percent survival of dextrose/hemorrhage animals (Zambell et al. 2004). In addition to cytokine dysregulation, alcohol impairs innate barrier functions of the lung by increasing epithelial cell permeability and altering the function of the ciliated epithelium (Elliott et al. 2007; Molina et al. 2010).

Neuroendocrine System

The pathophysiology of traumatic-hemorrhagic injury involves decreased blood volume (i.e., hypovolemia) and hypoperfusion, which results in signaling to central cardiovascular centers aimed at restoring hemodynamic stability through activation of descending autonomic neuroendocrine pathways (Molina 2005). Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for the increased hypotension and impaired hemodynamic stability observed with alcohol intoxication, with one proposed mechanism being blunted neuroendocrine activation. Studies demonstrated that acute alcohol intoxication at the time of injury results in significant attenuated release of counterregulatory hormones and potent vasoconstrictors such as arginine vasopressin (AVP), epinephrine, and norepinephrine in response to fixed-pressure hemorrhage (Phelan et al. 2002). A disruption in the neuroendocrine response with alcohol intoxication at the time of injury is associated with enhanced expression of lung and spleen TNF-α as well as suppression of circulating neutrophil function, which would be expected to enhance the risk for tissue injury (Whitaker et al. 2010). Conversely, Sato and colleagues (2013) demonstrated that alcohol aggravates hemorrhagic shock in a dose-dependent manner not by triggering an immune response but by suppressing hormonal and neuro-humoral responses, thereby inhibiting hemodynamic auto-regulation and shortening the survival interval. Thus, both alcohol and hemorrhagic shock have detrimental effects on neuroendocrine responses that are likely to modulate the host immune system in addition to impacting on hemodynamic stability and recovery and accentuating tissue hypoperfusion and end-organ injury.

Alcohol and Traumatic Brain Injury

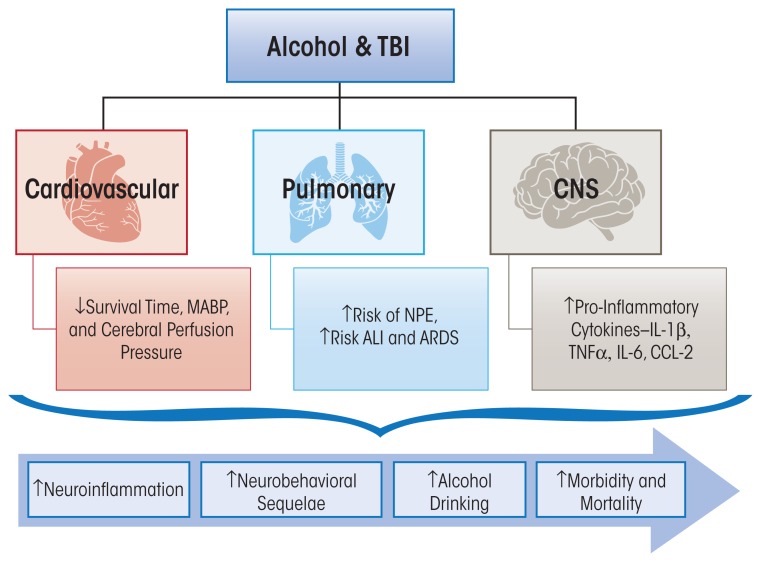

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) accounts for approximately 50 percent of all trauma-related mortality (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012b). TBI affects multiple sectors of the population, and young males have the highest rates of hospital visits and death (Faul et al. 2010). Falls are the first leading cause of TBI, followed by motor vehicle accidents and unintentional trauma sustained during sports activities such as football or boxing. TBI can be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe, and the majority of TBIs sustained in the United States are in the mild category (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012b). In addition to the physical dysfunction caused by injury, TBI patients frequently experience lingering psychological symptoms, such as heightened anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances, and pain hypersensitivity (Whyte et al. 1996). These symptoms have been implicated in increased alcohol intake following TBI in humans (Adams et al. 2012). Furthermore, it is well accepted that alcohol consumption increases the risks of sustaining a TBI (Corrigan 1995; Hurst et al. 1994). Nevertheless, a comprehensive understanding of the influences of alcohol on TBI-induced inflammation, recovery from injury, and long-term damage currently is limited and is summarized in the following section (see figure 3).

Figure 3.

Salient cardiovascular, pulmonary, and central nervous system pathophysiological consequences of alcohol abuse prior to, or at the time of, traumatic brain injury (TBI). The disruption in hemodynamic homeostasis resulting from TBI contributes to decreased cerebral perfusion pressure. The lung is affected through neurogenic mechanisms leading to neuropulmonary edema (NPE) and associated risk for acute lung injury (ALI) and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). In the brain (CNS), alcohol accentuates neuroinflammation, which is associated with neurobehavioral dysfunction that can potentially promote alcohol drinking. Together, these pathophysiological consequences increase morbidity and mortality from TBI.

Neuroinflammation

The pathophysiology of TBI involves a primary mechanical injury followed by a secondary tissue injury resulting from neuroinflammation (Werner and Engelhard 2007). A large percentage of TBI victims show signs of further deterioration following the event (Sauaia et al. 1995). This suggests the induction of a secondary brain injury and immune activation as the key cascades contributing to the pathophysiological processes of the secondary damage (Cederberg and Siesjo 2010). After TBI, a series of events occurs, including the activation of resident immune cells such as astrocytes and microglia, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules, and recruitment and activation of blood-derived leukocytes across the disrupted blood brain barrier (Feuerstein et al. 1998; Morganti-Kossmann et al. 2001; Ransohoff 2002). An increase in the levels of TNF-α in the serum or cerebrospinal fluid in victims of TBI also has been detected in rodents following closed head injury (Goodman et al. 1990; Ross et al. 1994; Shohami et al. 1994). IL-1β is released after TBI (Fan et al. 1995) and induces nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κ B), a key transcription factor that regulates the expression of genes encoding cytokines, as well as inducible NO synthase (iNOS), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (Blanco and Guerri 2007; Woodroofe et al. 1991; Ziebell and Morganti-Kossmann 2010). Following the rise of early cytokines, the release of IL-6 is associated with increased acute-phase proteins, as well as blood–brain barrier disruption (Kossmann et al. 1995; Shohami et al. 1994; Woodcock and Morganti-Kossmann 2013) and sustained elevation of chemokines such as chemokine (C-C motif) ligand-2 (CCL-2) in the cerebrospinal fluid for as long as 10 days post-injury (Semple et al. 2010). Although early cytokine release is essential in mediating the reparative processes after injury (Ziebell and Morganti-Kossmann 2010), sustained elevation of pro-inflammatory mediators has been increasingly recognized to play a role in neuropathological changes associated with long-term degenerative diseases (Fan et al. 1995; Lyman et al. 2014). Accordingly, the additional risks of alcohol as a factor contributing to the alterations of TBI-induced neuroinflammatory processes may affect the overall recovery.

Alcohol exerts a profound impact on neuroinflammation. Although there are some conflicting reports in the literature about the role of alcohol on recovery, the major findings are summarized here. Some animal studies suggest that acute alcohol administration prior to TBI leads to an early reduction in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the injured cortex, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, as well as in the serum shortly after TBI (Goodman et al. 2013; Gottesfeld et al. 2002). Recent studies also have confirmed that acute alcohol intoxication at the time of TBI does not exacerbate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines at 6 hours post-injury. However, results obtained at a later time point (24 hours) show a sustained mRNA expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and CCL-2 following a lateral fluid percussion injury in rodents that were alcohol-intoxicated at the time of TBI (Teng and Molina 2014). Overall, some preclinical studies suggest that acute alcohol treatment prior to TBI may lead to a suppressed release of pro-inflammatory mediators during the early phase post-injury. Thus, the temporal pattern of neuroinflammatory responses and the impact of alcohol intoxication on neuroinflammatory responses are factors to consider when drawing conclusions on the role of alcohol in modulating the outcome from TBIs.

Because the literature surrounding the relationship between acute alcohol intoxication and response to trauma is conflicting, it is important to consider the pattern of alcohol abuse and the model used in different studies. In general, reports in the literature indicate that chronic alcohol exposure produces immune activation in the brain, inducing an enhanced pro-inflammatory state, as evidenced by the presence of CCL-2 and microglial activation in postmortem brains of human alcoholics (He and Crews 2008). Animal studies show that chronic, intermittent binge alcohol administration to rodents results in increased microglial activation and inflammatory cytokine expression in the cortex and hippocampus (Zhao et al. 2013). In addition, Crews and colleagues (2004) have found that chronic alcohol treatment induces expression of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, which further activates resident glial cells to secrete additional pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, resulting in an increased immune activation in the brain. The overall pro-inflammatory effects of alcohol also have been shown by Guerri and colleagues (2007) who reported alcohol-mediated stimulation of TLR-4 and IL-1 receptor signaling pathways, including extracellular regulated-kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), as well as the expression of NF-kB, activator protein-1 (AP-1), iNOS, and COX-2 in cultured glial cells (Alfonso-Loeches et al. 2010; Fernandez-Lizarbe et al. 2009). The role of TLR4 has been identified in studies where 5 months of chronic alcohol administration increased glial activation and levels of caspase-3, iNOS, COX-2, and cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6) in the cerebral cortex of wild-type mice but not in the TLR-4–deficient mice (Alfonso-Loeches et al. 2010). Another mediator of alcohol-mediated neuroinflammation is high-mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1), which has been reported to be increased along with TLR-2, TLR-3, and TLR-4 in postmortem brains of human alcoholics (Alfonso-Loeches et al. 2010). Despite a substantial amount of evidence showing increased neuroinflammatory responses to chronic alcohol exposure, there have not been sufficient preclinical studies performed to determine the combined effect of chronic alcohol consumption and TBI on neuroimmune activation. Because both TBI and alcohol can induce inflammation in the brain, we speculate that the combination of the two events would further accentuate neuroinflammation.

Retrospective studies have revealed that outside of the central nervous system, peripheral organ damage can contribute to the increased mortality rate among TBI patients as a result of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and endocrine dysfunction (Gennarelli et al. 1989; Shavelle et al. 2001). More specifically, TBI patients have an increased incidence of ALI, pulmonary infection, neuroendocrine alterations, and cardiovascular dysfunction during the post-injury period (Vermeij et al. 2013). Although the combined effects of alcohol and TBI and the role of local or systemic immune responses in peripheral organs are understudied, the current knowledge is summarized below (figure 3).

Pulmonary System

ALI, one of the most common nonneurologic complications following TBI, results from acute pulmonary edema and inflammation and can lead to ARDS (Holland et al. 2003; Johnson and Matthay 2010). ALI is characterized by hypoxemia, loss of lung compliance, and bilateral chest infiltrates (Dushianthan et al. 2011). Development of ALI post-TBI has been associated with increased inpatient mortality following injury and worse long-term neurologic outcome in survivors of TBI (Bratton and Davis 1997; Holland et al. 2003). Post-TBI medical interventions including induced systemic hypertension and mechanical ventilation can result in nonneurogenic ALI (Contant et al. 2001; Lou et al. 2013). Development of neurogenic pulmonary edema (NPE) occurs minutes to hours following TBI and typically resolves within days (Bratton and Davis 1997). The possible underlying factors in NPE are the severity of injury leading to increased intracranial pressure and the subsequent increased circulating catecholamines (Demling and Riessen 1990). TBI also is associated with greater incidence of pulmonary infections than that seen following major surgeries, burn injury, and polytrauma (Dziedzic et al. 2004). Clinical reports indicate that over 40 percent of TBI patients with artificial ventilation develop pneumonia and are four times more likely to die from pneumonia (Harrison-Felix et al. 2006). The increased risk of developing pneumonia post-TBI is potentially attributed in part to a systemic immune response syndrome (SIRS) characterized by increased circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) (Keel and Trentz 2005; Kossmann et al. 1995).

The combined impact of alcohol and TBI on pulmonary infections has been minimally investigated. Although, epidemiological studies have shown that in trauma patients, chronic alcohol abuse can independently increase the risk of ALI and ARDS two- to fourfold (Guidot and Hart 2005). In a prospective study of traumatic injury patients with evidence of acute alcohol intoxication or chronic alcohol abuse, chronic alcohol was associated with increased incidence of pneumonia or respiratory failure as a result of its immunosuppressive effects. However, no significant increase in incidence of pneumonia or respiratory failure and mortality was observed in patients with acute alcohol intoxication with BAC above 100mg/dL (De Guise et al. 2009; Jurkovich et al. 1993). The importance of length and amount of pre-existing alcohol intake and TBI severity may be the key factors in determining a patient’s risk for pneumonia. Taken together, the potential effects of chronic alcohol abuse and TBI could potentiate and further increase immunosuppression or immune dysfunction, thus leading to greater susceptibility for pneumonia, ARDS, and ultimately death.

Neuroendocrine System

TBI can lead to a variety of neuroendocrine abnormalities, such as gonadotropin deficiency, growth hormone deficiency, corticotrophin deficiency, and vasopressin alterations (Behan and Agha 2007; Powner and Boccalandro 2008). As a result of the mechanical compression to the pituitary gland or disruption of the pituitary stalk, hypopituitarism can occur and corticotrophin insufficiency is commonly observed after TBI (Agha et al. 2004; Cohan et al. 2005). Excessive alcohol use also has been reported to be associated with neuroendocrine dysfunction, notably in the form of altered regulation of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA), resulting in a decreased corticotrophin release (Behan and Agha 2007; Helms et al. 2014). Therefore, it is possible that the combination of alcohol and TBI-induced HPA dysfunction can lead to a dampened cortisol release, which may have an impact on the immune system. Interestingly, a hyperadrenergic state marked by elevated levels of catecholamines can occur after TBI, and alcohol intoxication at the time of TBI has been shown to blunt the sympatho-adrenal activation in a dose-dependent manner (Woolf et al. 1990). Vasopressin has been suggested to play a role in blood brain barrier disruption, edema formation, and the production of pro-inflammatory mediators after TBI (Szmydynger-Chodobska et al. 2010). Vasopressin abnormalities leading to diabetes insipidus or the syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone (SIADH) frequently are observed after TBI (Behan and Agha 2007), and acute alcohol intoxication is known to alter AVP release (Taivainen et al. 1995). Whether alcohol intoxication at the time of TBI or during the recovery period from TBI further dysregulates these neuroendocrine mechanisms remains to be examined.

Cardiovascular System

Cardiovascular complications including slow heart rate (i.e., bradycardia), hypotension, electrocardiographic changes, arrhythmias, and increased circulating cardiac enzymes have been reported following TBI (Bourdages et al. 2010; Wittebole et al. 2005). Chronic alcohol abuse alone can lead to alcoholic cardiomyopathy and potentially heart failure (Skotzko et al. 2009), and the underlying etiology has been reviewed (Lang et al. 2005). Several studies by Zink and colleagues (1998a,b, 2006) focused on the combined effects of acute alcohol intoxication on hemorrhagic shock and TBI in swine, showing decreased survival time, lowered MABP, and reduced cerebral perfusion pressure, which may worsen secondary brain injury. These studies did not investigate alterations in immune function or expression and levels of immune modulators or their actions on cardiovascular function. Overall, the post-TBI cardiovascular complications, including vascular function, have been understudied in both clinical and experimental models of TBI. More specifically, the combined impact of alcohol, TBI, and immune alterations on cardiovascular dysfunction and disease progression has not been examined. A possible prediction is that chronic alcohol-induced immunosuppression would worsen post-TBI cardiovascular complications; and in chronic alcoholics, dilated cardiomyopathy may compound TBI-related cardiovascular complications increasing morbidity and mortality.

Summary

The deleterious effects of alcohol on the immune system in three traumatic injuries are discussed in this review and are summarized in figures 1, 2, and 3. It is evident that, independently, acute or chronic alcohol consumption and traumatic injury negatively modulate the immune system, and the end result is an uncontrolled release of inflammatory mediators. The most important message of this review is the accumulation of evidence that alcohol combined with traumatic injury can significantly affect morbidity and mortality through disruption in host immune responses. Following burn injury, for instance, the risk for infection is greatly increased because of increased gut permeability and increased pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in the lungs (figure 1). Alcohol use following hemorrhage can increase inflammation and oxidative stress in the gut while decreasing lung barrier function and subsequently increasing susceptibility to infection (figure 2). In the central nervous system, alcohol use following TBI can increase neuroinflammation and prolong the recovery period (figure 3). Overall this information is important, because it provides a wealth of evidence that alcohol combined with trauma is a dramatic and preventable cause of increased morbidity and mortality following injury. Mechanistically, two common pro-inflammatory cytokines that are consistently upregulated in all burn injury, hemorrhagic shock, and TBI are TNF-α and IL-6. A fuller understanding of their temporal pattern of expression and downstream effects requires further investigation. Although the studies described in this review have generated important information on the impact of alcohol combined with different types of traumatic injury, and the resultant adverse effects on the immune system, further preclinical and clinical studies to dissect the complex cascade of immunomodulation following injury are necessary. Specifically, further investigation is warranted to determine the underlying mechanisms involved in immune modulation by acute or chronic alcohol intake and the effects on (1) metabolism and the cardiovascular system following burn, (2) the neuroendocrine system following hemorrhagic shock, and (3) neuroinflammation and the neuroendocrine system following traumatic injury. The responses of the immune system to these inflammatory stimuli are variable and appear to be dependent on the severity of the injury, comorbidities, and the level of alcohol intoxication. Thus, it is necessary to systemically address these variables for translational research to identify potential therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, therapeutic targets for immunomodulation and attenuation of tissue injury in intoxicated and injured patients are likely to reduce morbidity and mortality and improve post-injury quality of life among these patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Liz Simon for her intellectual contribution to this review and Rebecca Gonzales for her editorial support.

Footnotes

Cytokines are proteins involved in cell signaling. They are produced by a variety of cells including immune cells and regulate the immune response.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- Abraham E. T- and B-cell function and their roles in resistance to infection. New Horizons. 1993;1(1):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, et al. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: Pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(7):848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agha A, Rogers B, Mylotte D, et al. Neuroendocrine dysfunction in the acute phase of traumatic brain injury. Clinical Endocrinology. 2004;60(5):584–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso-Loeches S, Pascual-Lucas M, Blanco AM, et al. Pivotal role of TLR4 receptors in alcohol-induced neuroinflammation and brain damage. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(24):8285–8295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0976-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angele MK, Knoferl MW, Schwacha MG, et al. Hemorrhage decreases macrophage inflammatory protein 2 and interleukin-6 release: A possible mechanism for increased wound infection. Annals of Surgery. 1999;229(5):651–660. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199905000-00007. discussion 660–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbabi S, Garcia I, Bauer GJ, Maier RV. Alcohol (ethanol) inhibits IL-8 and TNF: Role of the p38 pathway. Journal of Immunology. 1999;162(12):7441–7445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala A, Wang P, Ba ZF, et al. Differential alterations in plasma IL-6 and TNF levels after trauma and hemorrhage. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260(1 Pt 2):R167–R171. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.1.R167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CC, Oppenheimer L, Stephens B, et al. Epidemiology of trauma deaths. American Journal of Surgery. 1980;140(1):144–150. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(80)90431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RC, Jerrells TR. Recent developments in alcoholism: Immunological aspects. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 1993;11:249–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ, Mercadel R. Correlation of alcohol intoxication with life-threatening assaults. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1998;90(12):761–764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan LA, Agha A. Endocrine consequences of adult traumatic brain injury. Hormone Research. 2007;68(Suppl 5):18–21. doi: 10.1159/000110466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessey PQ, Phillips BD, Lentz CW, et al. Synopsis of the 2013 annual report of the National Burn Repository. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2014;35(Suppl 2):S218–S234. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird MD, Kovacs EJ. Organ-specific inflammation following acute ethanol and burn injury. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;84(3):607–613. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird MD, Morgan MO, Ramirez L, et al. Decreased pulmonary inflammation after ethanol exposure and burn injury in intercellular adhesion molecule-1 knockout mice. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2010;31(4):652–660. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181e4c58c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco AM, Guerri C. Ethanol intake enhances inflammatory mediators in brain: Role of glial cells and TLR4/IL-1RI receptors. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2007;12:2616–2630. doi: 10.2741/2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boe DM, Vandivier RW, Burnham EL, Moss M. Alcohol abuse and pulmonary disease. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2009;86(5):1097–1104. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdages M, Bigras JL, Farrell CA, et al. Cardiac arrhythmias associated with severe traumatic brain injury and hypothermia therapy. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2010;11(3):408–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratton SL, Davis RL. Acute lung injury in isolated traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(4):707–712. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199704000-00009. discussion 712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Cook RT, Jerrells TR, et al. Acute and chronic alcohol abuse modulate immunity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(9):1624–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Ping XD, Harris FL, Gauthier TW. Glutathione availability modulates alveolar macrophage function in the chronic ethanol-fed rat. American Journal of Physiology Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2007;292(4):L824–L832. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00346.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EA, Burks D, Fischman AJ, et al. Insulin resistance in thermally-injured rats is associated with post-receptor alterations in skeletal muscle, liver and adipose tissue. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2004;14(4):653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EA, Tompkins RG, Schiffrin E, Burke JF. Cutaneous thermal injury alters macromolecular permeability of rat small intestine. Surgery. 1990;107(3):335–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederberg D, Siesjo P. What has inflammation to do with traumatic brain injury? Child’s Nervous System. 2010;26:221–226. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-1029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System 2009. Atlanta: CDC; 2009. [Accessed March 3, 2015]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_2012-a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC—Chronic Disease—Excessive Alcohol Use—At a Glance. Atlanta: CDC; 2012a. [Accessed March 3, 2015]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC—Statistics—Injury Prevention & Control: Traumatic Brain Injury. Atlanta: CDC; 2012b. [Accessed March 3, 2015]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/ [Google Scholar]

- Chen MM, Bird MD, Zahs A, et al. Pulmonary inflammation after ethanol exposure and burn injury is attenuated in the absence of IL-6. Alcohol. 2013;47(3):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry MA, Fazal N, Goto M, et al. Gut-associated lymphoid T cell suppression enhances bacterial translocation in alcohol and burn injury. American Journal of Physiology Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2002;282(6):G937–G947. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00235.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry MA, Messingham KA, Namak S, et al. Ethanol exacerbates T cell dysfunction after thermal injury. Alcohol. 2000;21(3):239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohan P, Wang C, McArthur DL, et al. Acute secondary adrenal insufficiency after traumatic brain injury: A prospective study. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33(10):2358–2366. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181735.51183.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contant CF, Valadka AB, Gopinath SP, et al. Adult respiratory distress syndrome: A complication of induced hypertension after severe head injury. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2001;95(4):560–568. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.4.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD. Substance abuse as a mediating factor in outcome from traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1995;76(4):302–309. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80654-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cree MG, Zwetsloot JJ, Herndon DN, et al. Insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function are improved in children with burn injury during a randomized controlled trial of fenofibrate. Annals of Surgery. 2007;245(2):214–221. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250409.51289.ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Collins MA, Dlugos C, et al. Alcohol-induced neurodegeneration: When, where and why? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(2):350–364. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000113416.65546.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson DP, Angeles Valero, Zanuy MA, León Sanz ML. Post-shock metabolic response, 1942. Nutrición Hospitalaria. 2001;16(5):176–182. discussion 175–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Guise E, Leblanc J, Dagher J, et al. Early outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury, pre-injury alcohol abuse and intoxication at time of injury. Brain Injury. 2009;23(11):853–865. doi: 10.1080/02699050903283221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Monte S, Derdak Z, Wands JR. Alcohol, insulin resistance and the liver-brain axis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;27(Suppl 2):33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitch EA. The role of intestinal barrier failure and bacterial translocation in the development of systemic infection and multiple organ failure. Archives of Surgery. 1990;125(3):403–404. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410150125024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitch EA, Berg R. Bacterial translocation from the gut: A mechanism of infection. Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation. 1987;8(6):475–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitch EA, Morrison J, Berg R, Specian RD. Effect of hemorrhagic shock on bacterial translocation, intestinal morphology, and intestinal permeability in conventional and antibiotic-decontaminated rats. Critical Care Medicine. 1990;18(5):529–536. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demling R, Riessen R. Pulmonary dysfunction after cerebral injury. Critical Care Medicine. 1990;18(7):768–774. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza NB, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, et al. Acute alcohol infusion suppresses endotoxin-induced serum tumor necrosis factor. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1989;13(2):295–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dushianthan A, Grocott MP, Postle AD, Cusack R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Postgraduate Medicine Journal. 2011;87(1031):612–622. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2011.118398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziedzic T, Slowik A, Szczudlik A. Nosocomial infections and immunity: Lesson from brain-injured patients. Critical Care. 2004;8:266–270. doi: 10.1186/cc2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MK, Sisson JH, Wyatt TA. Effects of cigarette smoke and alcohol on ciliated tracheal epithelium and inflammatory cell recruitment. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2007;36(4):452–459. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0440OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertel W, Singh G, Morrison MH, et al. Chemically induced hypotension increases PGE2 release and depresses macrophage antigen presentation. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264(4 Pt 2):R655–R660. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.4.R655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Young PR, Barone FC, et al. Experimental brain injury induces expression of interleukin-1 beta mRNA in the rat brain. Brain Research Molecular Brain Research. 1995;30(1):125–130. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00287-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths 2002–2006. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010. [Accessed March 3, 2015]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/blue_book.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Faunce DE, Garner JL, Llanas JN, et al. Effect of acute ethanol exposure on the dermal inflammatory response after burn injury. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27(7):1199–1206. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000075833.92139.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Kovacs EJ. Acute ethanol exposure prior to thermal injury results in decreased T-cell responses mediated in part by increased production of IL-6. Shock. 1998;10(2):135–140. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199808000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Kovacs EJ. Effects of acute ethanol exposure on cellular immune responses in a murine model of thermal injury. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1997;62(6):733–740. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lizarbe S, Pascual M, Guerri C. Critical role of TLR4 response in the activation of microglia induced by ethanol. Journal of Immunology. 2009;183(7):4733–4744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein GZ, Wang X, Barone FC. The role of cytokines in the neuropathology of stroke and neurotrauma. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1998;5(3–4):143–159. doi: 10.1159/000026331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink MP. Gastrointestinal mucosal injury in experimental models of shock, trauma, and sepsis. Critical Care Medicine. 1991;19(5):627–641. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Zhang X, Wang FR, et al. Chronic ethanol consumption up-regulates protein-tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP1B) expression in rat skeletal muscle. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2010;31(12):1576–1582. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauglitz GG, Herndon DN, Kulp GA, et al. Abnormal insulin sensitivity persists up to three years in pediatric patients post-burn. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;94(5):1656–1664. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennarelli TA, Champion HR, Sacco WJ, et al. Mortality of patients with head injury and extracranial injury treated in trauma centers. Journal of Trauma. 1989;29(9):1193–1201. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198909000-00002. discussion 1201–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JC, Robertson CS, Grossman RG, Narayan RK. Elevation of tumor necrosis factor in head injury. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 1990;30(2):213–217. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(90)90105-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MD, Makley AT, Campion EM, et al. Preinjury alcohol exposure attenuates the neuroinflammatory response to traumatic brain injury. Journal of Surgical Research. 2013;184(2):1053–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesfeld Z, Moore AN, Dash PK. Acute ethanol intake attenuates inflammatory cytokines after brain injury in rats: A possible role for corticosterone. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2002;19(3):317–326. doi: 10.1089/089771502753594882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiffenstein P, Mathis KW, Stouwe CV, Molina PE. Alcohol binge before trauma/hemorrhage impairs integrity of host defense mechanisms during recovery. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(4):704–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidot DM, Hart CM. Alcohol abuse and acute lung injury: Epidemiology and pathophysiology of a recently recognized association. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 2005;53(5):235–245. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.53506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney JG, Rivara FP, Mueller BA, et al. The effects of alcohol intoxication on the initial treatment and hospital course of patients with acute brain injury. Journal of Trauma. 1992;33(5):709–713. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199211000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happel KI, Nelson S. Alcohol, immunosuppression, and the lung. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2005;2(5):428–432. doi: 10.1513/pats.200507-065JS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Felix C, Whiteneck G, Devivo MJ, et al. Causes of death following 1 year postinjury among individuals with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2006;21(1):22–33. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haum A, Perbix W, Hack HJ, et al. Alcohol and drug abuse in burn injuries. Burns. 1995;21(3):194–199. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)80008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Crews FT. Increased MCP-1 and microglia in various regions of the human alcoholic brain. Experimental Neurology. 2008;210(2):349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms CM, Park B, Grant KA. Adrenal steroid hormones and ethanol self-administration in male rhesus macaques. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2014;231(17):3425–3436. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3590-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon DN, Tompkins RG. Support of the metabolic response to burn injury. Lancet. 2004;363(9424):1895–1902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hierholzer C, Kalff JC, Omert L, et al. Interleukin-6 production in hemorrhagic shock is accompanied by neutrophil recruitment and lung injury. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275(3 Pt 1):L611–L621. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.3.L611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillers VN, Massey LK. Interrelationships of moderate and high alcohol consumption with diet and health status. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1985;41(2):356–362. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland MC, Mackersie RC, Morabito D, et al. The development of acute lung injury is associated with worse neurologic outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of Trauma. 2003;55(1):106–111. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000071620.27375.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JW. Bacterial translocation after burn injury: The contribution of ischemia and permeability changes. Shock. 1994;1(4):286–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst PM, Harte D, Frith WJ. The Grand Rapids dip revisited. Accident: Analysis and Prevention. 1994;26(5):647–654. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke MG, Barrow RE, Herndon DN. Extended hypermetabolic response of the liver in severely burned pediatric patients. Archives of Surgery. 2004;139(6):641–647. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.6.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, et al. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Annals of Surgery. 2008;248(3):387–401. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ER, Matthay MA. Acute lung injury: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Journal of Aerosol Medicine and Pulmonary Drug Delivery. 2010;23(4):243–252. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Gurney JG, et al. The effect of acute alcohol intoxication and chronic alcohol abuse on outcome from trauma. JAMA. 1993;270(1):51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Gurney JG, et al. Effects of alcohol intoxication on the initial assessment of trauma patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1992;21(6):704–708. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82783-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh MJ, Clark C, Goto M, et al. Effect of acute alcohol ingestion prior to burn injury on intestinal bacterial growth and barrier function. Burns. 2005;31(3):290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel M, Trentz O. Pathophysiology of polytrauma. Injury. 2005;36(6):691–709. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh C, Fong Y, Marano MA, et al. Identification of a novel tumor necrosis factor alpha/cachectin from the livers of burned and infected rats. Archives of Surgery. 1990;125(1):79–84. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410130085011. discussion 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzian A, Fields JZ, Vaeth J, Holmes EW. The differing effects of acute and chronic alcohol on gastric and intestinal permeability. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1994;89(12):2205–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S, Fantus IG. Inhibition of the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B: Potential therapy for obesity, insulin resistance and type-2 diabetes mellitus. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2007;21(4):621–640. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzick DH, Sharda DR, Pruznak AM, Lang CH. Aging accentuates alcohol-induced decrease in protein synthesis in gastrocnemius. American journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2013;304(10):R887–R898. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00083.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossmann T, Hans VH, Imhof HG, et al. Intrathecal and serum interleukin-6 and the acute-phase response in patients with severe traumatic brain injuries. Shock. 1995;4(5):311–317. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199511000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer GC, Lund T, Beckum O. Pathophysiology of burn shock and burn edema. In: Herndon DN, editor. Total Burn Care. 3rd ed. London: Saunders; 2007. pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lang CH, Derdak Z, Wands JR. Strain-dependent differences for suppression of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal and cardiac muscle by ethanol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(4):897–910. doi: 10.1111/acer.12343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang CH, Frost RA, Summer AD, Vary TC. Molecular mechanisms responsible for alcohol-induced myopathy in skeletal muscle and heart. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2005;37(10):2180–2195. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Kovacs EJ, Schwacha MG, et al. Acute alcohol intoxication increases interleukin-18-mediated neutrophil infiltration and lung inflammation following burn injury in rats. American Journal of Physiology Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2007;292(5):L1193–L1201. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00408.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. Acute alcohol intoxication potentiates neutrophil-mediated intestinal tissue damage after burn injury. Shock. 2008;29(3):377–383. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31815abe80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston DH, Malangoni MA. Interferon-gamma restores immune competence after hemorrhagic shock. Journal of Surgery Research. 1988;45(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(88)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou M, Chen X, Wang K, et al. Increased intracranial pressure is associated with the development of acute lung injury following severe traumatic brain injury. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2013;115(7):904–908. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman M, Lloyd DG, Ji X, et al. Neuroinflammation: The role and consequences. Neuroscience Research. 2014;79:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KS, Sanders VM, Felten DL. Catecholamine influences and sympathetic neural modulation of immune responsiveness. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1995;35:417–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnotti LJ, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Gut-derived mesenteric lymph: A link between burn and lung injury. Archives of Surgery. 1999;134(12):1333–1340. discussion 1340–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis KW, Zambell K, Olubadewo JO, Molina PE. Altered hemodynamic counter-regulation to hemorrhage by acute moderate alcohol intoxication. Shock. 2006;26(1):55–61. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000215320.06866.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough KH, Giaimo ME, Miller HI, Gentilello LM. Low-dose ethanol alters the cardiovascular, metabolic, and respiratory compensation for severe blood loss. Journal of Trauma. 2002;53(3):541–548. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200209000-00024. discussion 548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill V, Kowal-Vern A, Fisher SG, et al. The impact of substance use on mortality and morbidity from thermal injury. Journal of Trauma. 1995;38(6):931–934. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199506000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGwin G, Jr, Chapman V, Rousculp M, et al. The epidemiology of fire-related deaths in Alabama, 1992–1997. Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation. 2000;21(1 Pt 1):75–83. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200021010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AJ, Guidot DM. Alcohol abuse, the alveolar macrophage and pneumonia. American Journal of the Medical Science. 2012;343(3):244–247. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31823ede77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messingham KA, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Alcohol, injury, and cellular immunity. Alcohol. 2002;28(3):137–149. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messingham KA, Fontanilla CV, Colantoni A, et al. Cellular immunity after ethanol exposure and burn injury: Dose and time dependence. Alcohol. 2000;22(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina PE. Neurobiology of the stress response: Contribution of the sympathetic nervous system to the neuroimmune axis in traumatic injury. Shock. 2005;24(1):3–10. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000167112.18871.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina PE, Bagby GJ, Stahls P. Hemorrhage alters neuroendocrine, hemodynamic, and compartment-specific TNF responses to LPS. Shock. 2001;16(6):459–465. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina PE, Happel KI, Zhang P, et al. Focus on: Alcohol and the immune system. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(1):97–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina PE, Sulzer JK, Whitaker AM. Alcohol abuse and the injured host: Dysregulation of counterregulatory mechanisms review. Shock. 2013;39(3):240–249. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318285b86d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morganti-Kossmann MC, Rancan M, Otto VI, et al. Role of cerebral inflammation after traumatic brain injury: A revisited concept. Shock. 2001;16(3):165–177. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200116030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano LM, Koruda MJ, Zimmerman K, et al. Chronic ethanol intake and burn injury: Evidence for synergistic alteration in gut and immune integrity. Journal of Trauma. 1995;38(2):198–207. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S, Bagby G, Andresen J, et al. The effects of ethanol, tumor necrosis factor, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on lung antibacterial defenses. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1991;288:245–253. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5925-8_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]