Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Intravenous magnesium did not shorten length of stay for pain crisis in children with sickle cell anemia.

Collaboration between pediatric emergency medicine and hematology allowed for successful enrollment in a sickle cell acute management trial.

Abstract

Magnesium, a vasodilator, anti-inflammatory, and pain reliever, could alter the pathophysiology of sickle cell pain crises. We hypothesized that intravenous magnesium would shorten length of stay, decrease opioid use, and improve health-related quality of life (HRQL) for pediatric patients hospitalized with sickle cell pain crises. The Magnesium for Children in Crisis (MAGiC) study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous magnesium vs normal saline placebo conducted at 8 sites within the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Children 4 to 21 years old with hemoglobin SS or Sβ0 thalassemia requiring hospitalization for pain were eligible. Children received 40 mg/kg of magnesium or placebo every 8 hours for up to 6 doses plus standard therapy. The primary outcome was length of stay in hours from the time of first study drug infusion, compared using a Van Elteren test. Secondary outcomes included opioid use and HRQL. Of 208 children enrolled, 204 received the study drug (101 magnesium, 103 placebo). Between-group demographics and prerandomization treatment were similar. The median interquartile range (IQR) length of stay was 56.0 (27.0-109.0) hours for magnesium vs 47.0 (24.0-99.0) hours for placebo (P = .24). Magnesium patients received 1.46 mg/kg morphine equivalents vs 1.28 mg/kg for placebo (P = .12). Changes in HRQL before discharge and 1 week after discharge were similar (P > .05 for all comparisons). The addition of intravenous magnesium did not shorten length of stay, reduce opioid use, or improve quality of life in children hospitalized for sickle cell pain crisis. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01197417.

Introduction

There are approximately 100 000 people in the United States with sickle cell disease, of whom 40% are children.1,2 These children experience approximately 18 000 hospitalizations and 75 000 hospitalization days annually for sickle cell pain crises.3 Much of the morbidity of the disease is a result of recurrent pain crises, which often result in emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations and adversely affect quality of life.4-7 Despite advances in the management of other comorbidities of sickle cell disease, little has changed in the management of pain crises. Intravenous (IV) opioids and the judicious use of IV fluids remain standard supportive therapy. Several multicenter trials in the setting of acute sickle cell painful crises have been closed because of inadequate enrollment, making advancements in the field difficult.8-10

Vasoconstriction and inflammation contribute to the initiation and prolongation of pain crises in sickle cell disease.11-15 Magnesium, a known vasodilator with anti-inflammatory effects, has the potential to alter the pathophysiology of pain crises.16-20 In addition to work exploring the use of magnesium administered orally to prevent pain crises,21,22 2 previous single-institution studies examining the effects of IV magnesium on acute pain crisis yielded conflicting results: one showed a shortened length of stay (LOS) from a median of 5 days to a median of 3 days compared with previous hospitalizations by the same individuals. Conversely, a randomized trial conducted in Canada with 104 children and an average LOS of more than 5 days found no decrease in length of hospitalization.23,24 These discrepant results lay the groundwork for a large randomized trial to definitely answer the question of magnesium’s efficacy. We undertook the MAGiC (Magnesium for Children in Crisis) study to determine the effect of the addition of IV magnesium to standard therapy for children hospitalized with pain crises. We developed a unique collaboration between pediatric emergency medicine physicians and pediatric hematologists to overcome enrollment barriers. We hypothesized that the addition of IV magnesium to standard therapy would shorten hospital LOS, decrease opioid use, and improve health-related quality of life (HRQL) for pediatric patients hospitalized with pain crises.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study design has been described previously.25 The MAGiC study was a multicenter, randomized, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of IV magnesium vs normal saline in addition to standard therapy for the treatment of pediatric sickle cell pain crisis. Participating centers included 8 sites (see “Acknowledgments”) within the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Collaborations between pediatric emergency medicine physicians and pediatric hematologists facilitated enrollment. Study funding was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Institutional review board approval was obtained at all participating sites, and an investigational new drug application (IND #78 057) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. A Data and Safety Monitoring Board monitored study progress and outcomes.

Participants

Children/young adults (hereafter termed “children”) aged 4 to 21 years with sickle cell anemia (including homozygous hemoglobin [Hgb]SS and HgbSβ0) were eligible if they required inpatient hospitalization after failing ED management for pain. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in full detail elsewhere.25 The genotype was reported by the parent and confirmed by either review of original electrophoresis or past hematology note. Race/ethnicity data and hydroxyurea status were obtained by parent/self-report, chosen from a standard National Institutes of Health listing of racial/ethnic categories; other demographic characteristics and past history were obtained by medical record review.

Study procedures

Children who failed ED opioids and required inpatient admission for pain were randomized in a 1:1 allocation to IV magnesium or normal saline placebo. IV magnesium was dosed at 40 mg/kg (maximum of 2.4 g) every 8 hours for a total of 6 doses or until discharge, whichever occurred first. Children randomized to placebo received an equivalent volume (1 mL/kg) of normal saline. Randomization was accomplished via a central randomization service, stratified by site, age group (4-11 vs 12-21 years), and hydroxyurea use. Hydroxyurea use was defined as patient/family-reported use within the last 3 months; no proof of compliance was assessed. The first dose of study medication was administered in the ED or after arrival on the inpatient floor and randomized within 12 hours of first ED IV opioid. A follow-up telephone call was made 8 to 10 days after discharge to collect information about HRQL and 7-day rehospitalizations. Written consent was obtained from all adult patients and from the legal guardians of all children enrolled, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Assent was obtained from all children older than 7 years; however, if the child was unable to assent because of pain or treatment, a waiver had been obtained and assent was obtained when the child was able to assent.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was length of stay from the time of first drug infusion until 12 hours after the last IV opioid dose or time of discharge, whichever occurred first.23,26,27

Secondary outcomes included opioid use, HRQL, markers of inflammation, hemolysis and endothelial activation, and adverse events. All opioid doses, whether IV or oral, were recorded and converted to IV morphine equivalents.25,28 The PedsQL generic core scales and the PedsQL multidimensional fatigue scales, which are valid and reliable for use in patients with sickle cell disease, were used to assess HRQL with the resultant total HRQL scores.29,30 The PedsQL sickle cell disease module, the only valid and reliable disease-specific measure for children with sickle cell disease, was also used.31 HRQL assessments were measured at all 8 sites by paper report (parent proxy for all patients 18 years old or younger, self-report for patients 8 years old or older, and self-report with aid of the research coordinator for patients aged 5-7 years) before the first study drug infusion, after the sixth dose of medication (or immediately before discharge if fewer than 6 doses were administered), and by telephone 8 to 10 days postdischarge. Biomarkers were measured 1 hour after the fourth dose of medication and analyzed as previously described.25 Specific adverse events, including hypotension, patient-reported feeling of warmth on infusion, and the development of acute chest syndrome were compared between the treatment groups. Patient blinding was assessed through a single question after the last administered dose, with patients asked whether they received placebo or magnesium or were unsure. Physician blinding was not assessed because of the multitude of providers involved in the care of the child.

Data analysis

We compared LOS using a Van Elteren test,32 a rank-based test that accounts for stratification, stratified by the same factors used to stratify randomization. Our modified intention-to-treat analysis excluded children who did not receive study drug, as LOS was measured from first study drug infusion and that calculation is not possible if no drug is received. Baseline characteristics are reported for all randomized patients in Table 1, but LOS and secondary outcomes only include the 98% who received study drug regardless of whether they received all protocol doses. Opioid equivalents and changes in HRQL were also compared using a Van Elteren test. To adjust for the 2 time point comparisons in HRQL, Holm’s procedure was used to determine significance. If the smallest P value was determined to be nonsignificant, the procedure stopped, and adjusted P values were not calculated. We also performed an exploratory, longitudinal analysis of HRQL scores over time, using a linear mixed-effects model to account for repeated measurements within subjects over time. Random effects were included, corresponding to each subject. As each of these HRQL outcomes is intended to measure the same general outcome, no adjustment for multiple comparisons was made. Missing HRQL data were handled per the developer’s instructions.33,34 Subjects who did not complete any HRQL measures during the study were not included in the mixed-effects model. Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Magnesium (n = 101)* | Placebo (n = 103)† |

|---|---|---|

| Sickle cell anemia type, n (%) | ||

| HgbSS | 92 (91) | 98 (95) |

| HgbSβ0 | 9 (9) | 5 (5) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 13.4 (4.6) | 13.8 (4.8) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| 4-11 y | 41 (41) | 40 (39) |

| 12-21 y | 60 (59) | 63 (61) |

| Female, n (%) | 49 (49) | 56 (54) |

| Weight, mean (SD) | 45.4 (19.2) | 46.3 (18.6) |

| Patient history, n (%) | ||

| Treated with hydroxyurea within 3 mo | 63 (62) | 60 (58) |

| History of acute chest syndrome | 74 (73) | 79 (77) |

| History of asthma | 50 (50) | 57 (55) |

| Times hospitalized for a pain crisis in past 3 y, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 8 (8) | 9 (9) |

| 1 | 10 (10) | 17 (17) |

| 2 | 21 (21) | 6 (6) |

| 3 | 14 (14) | 18 (17) |

| 4-5 | 17 (17) | 14 (14) |

| ≥6 | 30 (30) | 38 (37) |

| Days of pain before ED arrival, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 26 (26) | 21 (20) |

| 1 | 36 (36) | 43 (42) |

| 2 | 11 (11) | 14 (14) |

| ≥3 | 28 (28) | 25 (24) |

| Hours from first opioid to study drug, median (IQR) | 7.3 (4.9-11.9) | 7.5 (5.1-12.0) |

| Total opioids (IV morphine equivalents) before first study drug, median (IQR), mg/kg | 0.32 (0.20-0.51) | 0.33 (0.20-0.53) |

| Received ketorolac prior to study drug administration, n (%) | 18 (18) | 23 (22) |

| Hemoglobin, median (IQR), g/100 mL | 8.5 (7.7-9.6) | 8.5 (7.7-9.2) |

| White blood cell count, median (IQR), ×103/μL | 13.5 (9.9-16.4) | 14.0 (11.4-17.7) |

One subject in the magnesium group did not have a baseline hemoglobin value; therefore, n = 100 for that result.

One subject in the placebo group did not have a hemoglobin or white blood cell value; therefore, n = 102 for that result.

The sample size requirements reflect the primary endpoint, LOS in hours. A sample size of 91 subjects per group was necessary to detect a 20-hour difference in LOS. To account for up to 5% noncompliance and interim monitoring boundaries, the final sample size was increased to 104 participants per group, or 208 total.

Results

Study enrollment

Enrollment occurred at 8 PECARN sites, with the initial 4 sites beginning enrollment between December 2010 and June 2011 and the subsequent 4 sites starting enrollment in approximately July 2012. The last patient enrolled was in December 2013. Using the PECARN network for enrollment resulted in an average enrollment rate of 0.95 patients per site per month.

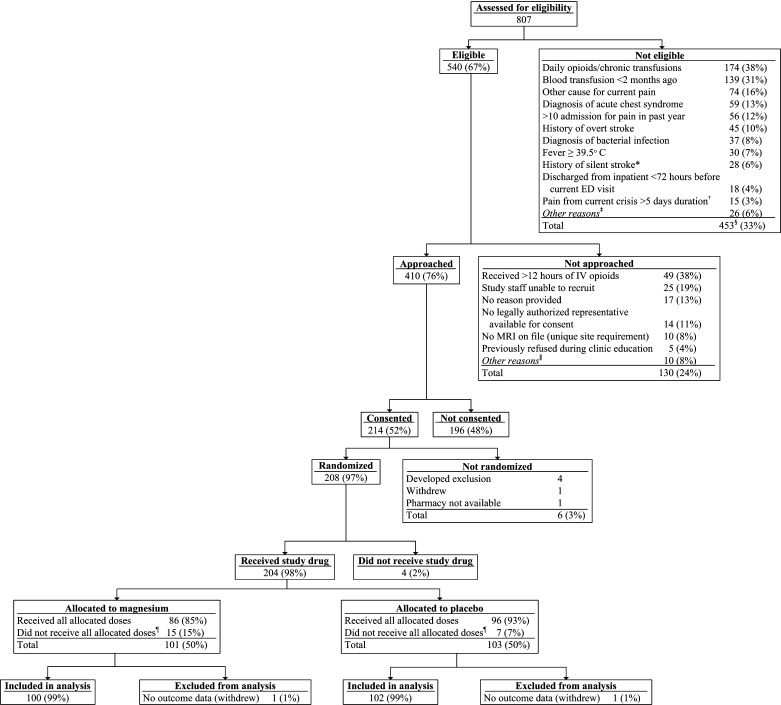

For the entire study, 410 (76%) of 540 eligible children were approached, and 214 (52%) of those approached consented to participate (Figure 1; supplemental Tables 1–3). A total of 208 children were randomized; 4 children were excluded before receipt of any study drug, resulting in 204 children eligible for analysis (101 children receiving magnesium; 103 receiving placebo). A total of 22 children did not receive all eligible infusions; the reasons were patient withdrawal (n = 5), hypotension (n = 3), physician request for study removal (n = 8), patient found to be ineligible (n = 5), and site miscommunication (n = 1). All children who received at least one dose of study drug are included in the analyses.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. *Exclusion criterion removed as a part of protocol version 1.04, dated January 11, 2012. †Exclusion criterion removed as a part of protocol version 1.03, dated July 5, 2011. ‡Exclusions with fewer than 10 occurrences included: intolerance to IV morphine and hydromorphone, known kidney/liver failure, pulmonary hypertension, pregnancy, diagnosis of hemodynamic instability or sepsis, taking oral magnesium, or current/planned use of neuromuscular blockers. §267 unique subjects; more than 1 exclusion possible on a visit; subjects may have had multiple visits. ǁReasons not approached with fewer than 5 occurrences included: physician request, inability to consent because of medical condition, language barrier, admitted to unit with untrained staff, unable to complete follow-up, research pharmacy closed, or patient refused to allow research team to speak with parents. ¶Reasons for not receiving all allocated doses included study withdrawal, hypotension, no 25-hour safety laboratory (blinded magnesium level), physician request, found to be ineligible, and site miscommunication.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 groups with respect to age, sex, genotype, weight, history of acute chest syndrome or asthma, previous hospitalizations within the past 3 years, days of pain before arrival, and treatment before study drug initiation (Table 1). More than 95% of the children were black or multiracial black, and 4% were Hispanic. Consistent with increasing hydroxyurea use clinically, approximately 60% of children had used hydroxyurea within 3 months. The median time from first ED opioid to first study drug infusion was 7.4 hours, which was similar between the 2 groups. Two children withdrew from further data collection during the study, so subsequent analyses are based on 202 children.

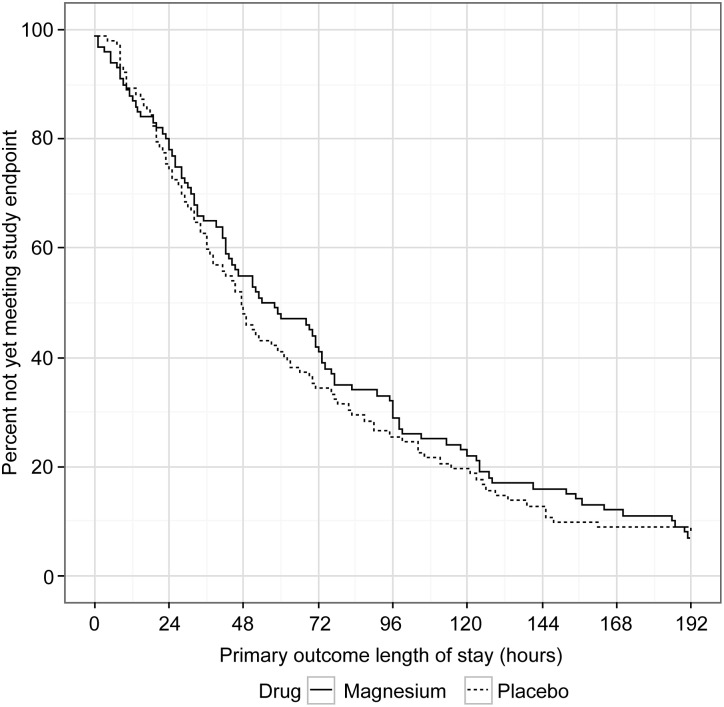

LOS

The median (IQR) LOS was 56.0 (27.0-109.0) hours in the magnesium group compared with 47.0 (24.0-99.0) hours in the placebo group (Figure 2); median LOS was not different between the groups (P = .24). When LOS was analyzed as total time until discharge from the hospital, regardless of the time of last opioid, there was again no difference in LOS between the 2 groups (magnesium, 74.5 [40-124] hours vs placebo, 60.5 [37-122] hours; P = .46). Of note, for the primary outcome, more than 50% of the participants met the study endpoint by 51 hours, and 25% by 25 hours. A post hoc subgroup subanalysis performed to evaluate whether magnesium had an effect on the primary LOS outcome if the child presented early in the course of the pain crisis (days of pain, 0 or 1 before ED visit) revealed no difference in LOS with magnesium vs placebo (magnesium, 58.0 [30.0-113.0] hours vs placebo, 47.0 [23.0-92.5] hours; P = .49). Similarly, another post hoc subgroup subanalysis based on number of hospitalizations in the past 3 years revealed no differences in LOS for those with 0 to 3, 4 to 6, and more than 6 hospitalizations (median LOS, 48, 60, and 54 hours, respectively) and no magnesium effect in any subgroup (P = .22).

Figure 2.

Magnesium vs placebo length of stay for primary outcome. Primary outcome length of stay defined as time from first study drug infusion until 12 hours after last intravenous opioid or time of discharge, whichever occurred first.

Secondary outcomes included morphine equivalents, quality-of-life scores, and markers of inflammation, hemolysis, and endothelial activation. Patients who received magnesium received a median of 1.46 mg/kg morphine equivalents compared with 1.28 mg/kg in the placebo group (P = .12). The changes in quality-of-life scores between the 2 groups were similar both at 48 hours and 8 to 10 days after discharge for all measures (Table 2). When examining HRQL data in the linear mixed-effects model, there were no differences found between treatment groups (P > .05; supplemental Table 4). Changes in markers of inflammation, hemolysis, and endothelial activation were similar between the magnesium and placebo groups (Table 3). Safety analysis revealed no differences in the development of acute chest syndrome (magnesium, 16% vs placebo, 14%; P = .78) or hypotension (magnesium, 4% vs placebo, 1%; P = .39) between the groups; however, warmth on infusion was higher in the magnesium group (26% vs 2%; P < .01). Overall, 93% of follow-up calls were completed at 8 to 10 days, and 7-day rehospitalization rates were similar between the 2 groups (magnesium, 12% vs placebo, 7%; P = .11).

Table 2.

Differences by treatment group in mean change in quality of life from ED to follow-up periods

| HRQL measure (time point) | Difference in mean change in HRQL (magnesium – placebo)* | P† |

|---|---|---|

| Child self-report total score | ||

| PedsQL Generic Scales | ||

| ED to predischarge | 1.5 | .94 |

| ED to 1-week follow-up | −2.3 | .36 |

| PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scales | ||

| ED to predischarge | 2.8 | .26 |

| ED to 1-week follow-up | −1.4 | .82 |

| PedsQL Sickle Cell Disease Module | ||

| ED to predischarge | −3.2 | .17 |

| ED to 1-week follow-up | −3.5 | .55 |

| Parent self-report total score | ||

| PedsQL Generic Scales | ||

| ED to predischarge | −5.4 | .12 |

| ED to 1-week follow-up | −2.0 | .42 |

| PedsQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scales | ||

| ED to predischarge | −2.7 | .30 |

| ED to 1-week follow-up | −0.5 | .68 |

| PedsQL Sickle Cell Disease Module | ||

| ED to predischarge | −2.4 | .06 |

| ED to 1-week follow-up | −0.4 | .59 |

Detailed sample size numbers are shown in the supplemental tables. In general, sample sizes for child report were 140 to 153 predischarge and 132 to 139 at 1 week. Parent report sample sizes were 130 to 136 both predischarge and at 1 week. Higher HRQL scores represent increased quality of life.

Mean change from HRQL score in magnesium group minus mean change from HRQL score in placebo group (eg, mean change in total HRQL for the magnesium group was 1.5 points higher between the ED and predischarge, but 2.3 points lower at 1-week follow-up).

Unadjusted P value. Using Holm’s method, a value less than .025 at any time would be considered significant. If significance at that level had been observed at any point, the next-lowest P value would be considered significant if below .05.

Table 3.

Differences by treatment group in markers of inflammation, hemolysis, and endothelial activation from ED to 25 hours of treatment

| Biomarker | Magnesium (n = 77) | Placebo (n = 85) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interferon γ, median (IQR) | 8.39 (−59.03 to 64.10) | −13.80 (−71.82 to 40.52) | .36 |

| Interleukin 1β, median (IQR) | 0.02 (−1.00 to 0.65) | −0.14 (−0.80 to 0.50) | .43 |

| Interleukin 6, median (IQR) | 2.36 (−5.05 to 11.53) | −0.65 (−9.65 to 4.72) | .25 |

| Nitrite, median (IQR) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.05) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.05) | .99 |

| Tumor necrosis factor α, median (IQR) | −0.80 (−6.93 to 2.66) | −0.28 (−4.97 to 3.17) | .94 |

| sP_selectin, median (IQR) | 1.84 (−7.31 to 11.91) | −2.65 (−11.67 to 6.00) | .07 |

| sVascular cell adhesion molecule 1, median (IQR) | 90.48 (−4.54 to 238.98) | 86.76 (−1.16 to 198.41) | .20 |

Analyzed using a Van Elteren test.

Ninety-two percent of children answered the question related to blinding. More children in the magnesium group (47% vs 21% in the placebo group) correctly identified their treatment allocation. However, the majority of children in both groups (magnesium group, 53% vs placebo group, 79%) either guessed incorrectly or stated that they did not know.

Subgroups

Prospectively defined subgroups used for randomization included age group and hydroxyurea use. No significant differential treatment effect was found across subgroups.

Discussion

The results of the MAGiC study indicate that the addition of IV magnesium to usual inpatient therapy for pediatric sickle cell pain crises does not shorten LOS, reduce opioid use, or improve HRQL. According to our pilot study, we hypothesized that magnesium would improve pediatric pain crisis. In addition, oral magnesium had been used previously to prevent pain crisis with some preliminary success, but the medication was not well tolerated.35 Despite these earlier studies suggesting possible benefit, our study shows that intravenous magnesium is not successful in treating sickle cell pain crisis.

This randomized controlled trial successfully enrolled more than 200 patients with sickle cell crisis at 8 sites within 3 years. Prior studies evaluating the management of acute sickle cell pain crises have closed prematurely because of an inability to enroll adequate numbers of subjects.8-10 These trials, despite having more sites than the MAGiC study, all enrolled fewer than 40 patients into their primary trials. They reported difficulty with patient/parent consent and were unable to approach potential subjects for recruitment outside of normal clinic hours, so parents were frequently no longer available, and the time from arrival to study initiation was significantly increased. We overcame this difficulty through collaboration between pediatric emergency medicine physicians and pediatric hematologists. The PECARN, a highly successful research network of 18 pediatric EDs across the United States, provided the essential infrastructure in which to conduct the study. Although the majority of the study drug-related procedures occurred on the inpatient unit, real-time screening, consent, randomization, and study initiation in the ED were responsible for the effective enrollment. Interventions to decrease LOS must be started early in the course of a hospitalization to have any significant effect.

Using the collaboration in this study, we successfully started study drug in less than 12 hours for 75% of children, even though consent and enrollment could not be performed until a decision was made to admit. Decreasing LOS with an effective disease-modifying drug is difficult to demonstrate if treatment is delayed for 24 hours, as one-fourth of children met the study endpoint by 25 hours and half met endpoint criteria by 51 hours after first study drug infusion. The total LOS in the study are similar to those from our institution before the trial.

We hypothesized that IV magnesium would be a safe and effective treatment of sickle cell pain crisis. IV magnesium sulfate has been shown to be safe and effective for other pediatric conditions, including for the ED treatment of asthma.36,37 Magnesium can cause vasodilation through both endothelial-dependent and endothelial-independent mechanisms, and vascular function is impaired in sickle cell disease.11,12,38 Magnesium can also alter inflammation; magnesium deficiency is associated with increased levels of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor α and increased expression of endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1.19,39,40 Because previously published data were conflicting,23,24 and magnesium could potentially alter vascular function and inflammation, a large multicenter study was needed to definitively answer the question of whether IV magnesium was effective, which we were able to do in this study. We were not able to show a differential effect on markers of inflammation, hemolysis, or endothelial activation in our study. This study also only evaluated IV magnesium, and thus is not generalizable to oral magnesium and does not address the potential benefits of oral magnesium, which have been studied in the prevention of painful crises, not the treatment of acute painful crises.

We chose to define LOS using a composite outcome: 12 hours after the last IV opioid dose or time of actual discharge, whichever occurred first. We chose this endpoint to most closely match what is normally the main discharge criteria for pain crises: the ability of the patient to control pain with orally administered opioids. This criterion has been used previously to ensure that hospitalizations prolonged for reasons not related to pain medication use, in particular transportation difficulties and social situations, did not count toward total LOS for sickle cell painful crises.27 However, when we simply compared time until discharge, there was no difference between groups. In addition, we measured the amount of opioid used to control pain during the hospitalization. Opioid medication use is a proxy for overall pain level, as the need for more pain medication is correlated with increased pain ratings by patients.41 A limitation of our study was measurement of opioid use, rather than pain scores. Although the clinical utility of pain scores is clear, the variability in pain scores throughout the day and the criticism that the timing of opioid treatments could significantly affect timed pain scores resulted in our decision to focus our secondary outcome on pain medication use.

Our study was also limited by the fact that more children in the magnesium group correctly identified their randomization group. However, the most of the children in each group were either incorrect or not sure when asked about their treatment group, and it seems unlikely that child knowledge of treatment group would have decreased the likelihood of magnesium being efficacious.

In conclusion, intravenous magnesium does not shorten LOS, lessen opioid use, or improve HRQL in children who require hospitalization for sickle cell pain crisis. Close collaboration between pediatric emergency medicine physicians and pediatric hematologists allows for the successful, efficient enrollment of large numbers of children in an acute intervention trial for children with sickle cell anemia.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following research staff members for their work on the project: Joanna Westerfield, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, Duke Wagner, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI; Jason Czachor, Wayne State University/Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, MI; Laura Turner, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Ashley Woodford, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA; Kathleen Calabro, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA; Karina Soto-Ruiz, Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX; Virginia Koors, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO; and Marie Kay, Heather Gramse, Sally Jo Zuspan, Casey Evans, Jun Wang, Tim Simmons, and Angie Webster, University of Utah/Data Coordinating Center, Salt Lake City, UT. This concept and proposal was approved by the members of the PECARN Steering Committee, and all work was reviewed by the Data Coordinating Center and the PECARN subcommittees: Grants and Publications, Protocol Review and Development, Feasibility and Budget and Quality Assurance. Finally, we thank those who served on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board: Kathleen Neville Maria Mori Brooks, Walt Schalick III, Cage Johnson, Lalit Bajaj, and David Schoenfeld.

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under Award Number 5R01HD062347-01 and Administrative Supplement Number 3R01HD062347-03S, as well as the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under Award Number 1R01HL103427-01A1. Further support was provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Emergency Medical Services for Children Network Development Demonstration Program for PECARN under cooperative agreement number U03MC00008, and is partially supported by Maternal and Child Health Bureau cooperative agreements: U03MC00001, U03MC00003, U03MC00006, U03MC00007, U03MC22684, U03MC22685. The information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the US government.

Footnotes

Presented as an oral abstract at the 56th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Francisco, CA, December 7, 2014.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: D.C.B., J.P.S., C.A.H., J.A.P., J.M.D., and T.C.C. designed the research project; D.C.B., J.P.S., O.B.-M., D.S.D., C.E.C., G.E.A., A.M.E., K.S.-W., P.M., S.A.S., J.L., M.L.H., E.C.P., R.I.L., R.H., L.K., C.A.H., M.N., and J.A.P. performed research and collected data; D.C.B., J.A.P., T.C.C., and L.J.C. analyzed and interpreted data; D.C.B., J.A.P., T.C.C., and L.J.C. performed statistical analyses; D.C.B. and J.A.P. wrote the first version of the manuscript; D.C.B., J.P.S., O.B.-M., D.S.D., C.E.C., G.E.A., A.M.E., K.S.-W., P.M., S.A.S., T.C.C., L.J.C., J.M.D., J.L., M.L.H., E.C.P., R.I.L., R.H., L.K., C.A.H., M.N., and J.A.P. edited the manuscript; and D.C.B., M.N., J.A.P., and J.M.D. ensured regulatory compliance.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David C. Brousseau, Children’s Corporate Center, Ste C550, 999 N 92nd St, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: dbrousse@mcw.edu.

References

- 1.Brousseau DC, Panepinto JA, Nimmer M, Hoffmann RG. The number of people with sickle-cell disease in the United States: national and state estimates. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(1):77–78. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S512–S521. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panepinto JA, Brousseau DC, Hillery CA, Scott JP. Variation in hospitalizations and hospital length of stay in children with vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44(2):182–186. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Platt OS, Thorington BD, Brambilla DJ, et al. Pain in sickle cell disease. Rates and risk factors. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(1):11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107043250103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, Panepinto JA, Steiner CA. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2010;303(13):1288–1294. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panepinto JA, Pajewski NM, Foerster LM, Sabnis S, Hoffmann RG. Impact of family income and sickle cell disease on the health-related quality of life of children. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):5–13. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar SM, Arbogast PG, Mitchel E, Cooper WO, Wang WC, Griffin MR. Medical care utilization and mortality in sickle cell disease: a population-based study. Am J Hematol. 2005;80(4):262–270. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dampier CD, Smith WR, Wager CG, et al. Sickle Cell Disease Clinical Research Network (SCDCRN) IMPROVE trial: a randomized controlled trial of patient-controlled analgesia for sickle cell painful episodes: rationale, design challenges, initial experience, and recommendations for future studies. Clin Trials. 2013;10(2):319–331. doi: 10.1177/1740774513475850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Styles L, Wager CG, Labotka RJ, et al. Sickle Cell Disease Clinical Research Network (SCDCRN) Refining the value of secretory phospholipase A2 as a predictor of acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease: results of a feasibility study (PROACTIVE). Br J Haematol. 2012;157(5):627–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters-Lawrence MH, Bell MC, Hsu LL, et al. Sickle Cell Disease Clinical Research Network (SCDCRN) Clinical trial implementation and recruitment: lessons learned from the early closure of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(2):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aslan M, Ryan TM, Adler B, et al. Oxygen radical inhibition of nitric oxide-dependent vascular function in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(26):15215–15220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221292098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):886–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(23):1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solovey A, Lin Y, Browne P, Choong S, Wayner E, Hebbel RP. Circulating activated endothelial cells in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(22):1584–1590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathare A, Kindi SA, Daar S, Dennison D. Cytokines in sickle cell disease. Hematology. 2003;8(5):329–337. doi: 10.1080/10245330310001604719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Z-W, Gebrewold A, Nowakowski M, Altura BT, Altura BM. Mg(2+)-induced endothelium-dependent relaxation of blood vessels and blood pressure lowering: role of NO. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278(3):R628–R639. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.3.R628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teragawa H, Matsuura H, Chayama K, Oshima T. Mechanisms responsible for vasodilation upon magnesium infusion in vivo: clinical evidence. Magnes Res. 2002;15(3-4):241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teragawa H, Kato M, Yamagata T, Matsuura H, Kajiyama G. Magnesium causes nitric oxide independent coronary artery vasodilation in humans. Heart. 2001;86(2):212–216. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rochelson B, Dowling O, Schwartz N, Metz CN. Magnesium sulfate suppresses inflammatory responses by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HuVECs) through the NFkappaB pathway. J Reprod Immunol. 2007;73(2):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weglicki WB, Phillips TM. Pathobiology of magnesium deficiency: a cytokine/neurogenic inflammation hypothesis. Am J Physiol. 1992;263(3 Pt 2):R734–R737. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.3.R734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W, Brugnara C, Snyder C, et al. The effects of hydroxycarbamide and magnesium on haemoglobin SC disease: results of the multi-centre CHAMPS trial. Br J Haematol. 2011;152(6):771–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankins JS, Wynn LW, Brugnara C, Hillery CA, Li CS, Wang WC. Phase I study of magnesium pidolate in combination with hydroxycarbamide for children with sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(1):80–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brousseau DC, Scott JP, Hillery CA, Panepinto JA. The effect of magnesium on length of stay for pediatric sickle cell pain crisis. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(9):968–972. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldman RD, Mounstephen W, Kirby-Allen M, Friedman JN. Intravenous magnesium sulfate for vaso-occlusive episodes in sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):e1634-1641. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Badaki-Makun O, Scott JP, Panepinto JA, et al. Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) Magnesium in Sickle Cell Crisis (MAGiC) Study Group. Intravenous magnesium for pediatric sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis: methodological issues of a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(6):1049–1054. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin TC, McIntire D, Buchanan GR. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone therapy for pain in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(11):733–737. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403173301101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orringer EP, Casella JF, Ataga KI, et al. Purified poloxamer 188 for treatment of acute vaso-occlusive crisis of sickle cell disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(17):2099–2106. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruddock B. Chronic pain: switching to an alternate opioid analgesic. Can Pharm J. 2005;138(1):44–45. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panepinto JA, Pajewski NM, Foerster LM, Hoffmann RG. The performance of the PedsQL generic core scales in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30(9):666–673. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31817e4a44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panepinto JA, Torres S, Bendo CB, et al. PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in sickle cell disease: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(1):171–177. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panepinto JA, Torres S, Bendo CB, et al. PedsQL™ sickle cell disease module: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(8):1338–1344. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Elteren PH. On the combination of independent two-sample tests of Wilcoxon. Bull Inst Int Statist. 1960;37(3):351–361. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Varni JW. The PedsQLTM 4.0 Measurement Model for the Pediatric Quality of Life InventoryTM Version 4.0: Administration Guidelines. Available at: http://www.pedsql.org/pedsqladmin.html. Accessed January 6, 2015.

- 34. Varni JW. The PedsQLTM Scoring Algorithm: Scoring the Pediatric Quality of Life InventoryTM. Available at: http://pedsql.org/score.html. Accessed January 6, 2015.

- 35.De Franceschi L, Bachir D, Galacteros F, et al. Oral magnesium pidolate: effects of long-term administration in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2000;108(2):284–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciarallo L, Brousseau D, Reinert S. Higher-dose intravenous magnesium therapy for children with moderate to severe acute asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(10):979–983. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.10.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowe BH, Bretzlaff JA, Bourdon C, Bota GW, Camargo CA., Jr Magnesium sulfate for treating exacerbations of acute asthma in the emergency department. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD001490. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nath KA, Katusic ZS, Gladwin MT. The perfusion paradox and vascular instability in sickle cell disease. Microcirculation. 2004;11(2):179–193. doi: 10.1080/10739680490278592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maier JA, Malpuech-Brugère C, Zimowska W, Rayssiguier Y, Mazur A. Low magnesium promotes endothelial cell dysfunction: implications for atherosclerosis, inflammation and thrombosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1689(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weglicki WB, Phillips TM, Freedman AM, Cassidy MM, Dickens BF. Magnesium-deficiency elevates circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines and endothelin. Mol Cell Biochem. 1992;110(2):169–173. doi: 10.1007/BF02454195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacob E, Miaskowski C, Savedra M, Beyer JE, Treadwell M, Styles L. Quantification of analgesic use in children with sickle cell disease. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(1):8–14. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210938.58439.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]