Abstract

Importance

Suicide is one of the top 10 leading causes of mortality among middle-aged women. Most work in the field emphasizes the psychiatric, psychological, or biological determinants of suicide.

Objective

To estimate the association between social integration and suicide mortality.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Nurses’ Health Study, an ongoing nationwide prospective cohort study of nurses. Beginning in 1992, a population-based sample of 72 607 nurses 46 to 71 years of age were surveyed about their social relationships.

Exposures

Social integration was measured with a seven-item index that included marital status, social network size, frequency of contact, religious participation, and participation in other social groups.

Main outcomes and measures

The vital status of study participants was ascertained through June 1, 2010. The primary outcome of interest was suicide, defined as deaths classified with codes E950 to E959 from the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision.

Results

The incidence of suicide decreased with increasing social integration. In a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model, the relative hazard of suicide was lowest among participants in the highest (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 0.23 [95% CI, 0.09 to 0.58]) and second-highest (AHR, 0.26 [CI, 0.09 to 0.74]) categories of social integration. Increasing or consistently high levels of social integration were associated with a protection against suicide. These findings were robust to sensitivity analyses that accounted for poor mental health and serious physical illness.

Conclusions and Relevance

Women who were socially well-integrated had a more than 3-fold lower risk for suicide over 18 years of follow-up.

Keywords: suicide, social determinants of health, social isolation

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is one of the top 10 leading causes of mortality among middle-aged women in the U.S. (1, 2). Over the past decade, suicide rates among middle-aged women in the U.S. have increased by more than 30%, exceeding even the relative increases observed among middle-aged men, the demographic group with the highest age-adjusted rate of suicide in the U.S. (3). These trends paralleled increases in suicide rates worldwide over the past decade (4), with current projections anticipating a continued increase in its contribution to the global mortality and disease burden (5).

With the exception of a growing literature based on data from the United Kingdom and Europe correlating changes in suicide rates with macroeconomic conditions during the recent economic crisis (6-9), most work in the field emphasizes the psychiatric, psychological, or biological determinants of suicide (10, 11). There is an historical tradition of concern about the social determinants of suicide, beginning with Durkheim, who postulated that suicide varies inversely with social integration (12). More recently, Joiner (13) and Van Orden et al. (14) elaborated an interpersonal theory of suicide consistent with Durkheim’s work in which the unmet “need to belong” (15) -- one facet of the higher-order construct of social integration -- is partly responsible for the development of passive suicidal ideation. Taken together, these conceptual models of suicide and suicidal behavior suggest a need for more research on its social determinants.

Using individual-level data from the U.S. Health Professionals Follow-up Study, we recently estimated the association between social integration and suicide among middle-aged men (16), but there were two important limitations of that study. First, the dataset lacked information about participants’ mental health status. Depressive disorders may compromise social relationships (17, 18), and it has been well established that the presence of a mood disorder is a strong risk factor for suicidal behavior (19, 20). Not accounting for the potentially confounding influence of mental health status could therefore bias estimates of the relationship between social integration and suicide away from the null. Second, social relationships may exert different influences on the mental health of women compared to men. Social ties may be more draining than nurturing for women, given gendered patterning in role demands (21, 22) or empathic concern for others (23). Consistent with some of these lines of inquiry, for example, Kposowa (24) found that being married exerted a strongly protective influence against suicide among men but not among women.

In general, the “low base-rate problem” (25) (i.e., there are 36,000 suicides in the U.S., relative to a population exceeding 300 million with an average life expectancy of approximately 78 years) makes it difficult for researchers to study the social determinants of suicide prospectively. More in-depth analyses of social relationships and suicide among women have been limited by the lack of large, prospective studies that also contain detailed information about social relationships beyond the “married”/“not married” indicators that are typically available in national registries (26, 27). Consequently, most studies in this field have instead used proxy outcomes such as suicide attempts (28, 29), or have been based on populations enriched for psychiatric morbidity (e.g., persons under psychiatric care (30-33)). To address these important gaps in the literature, we used data from the U.S. Nurses’ Health Study to estimate the association between social integration and suicide among women over 18 years of follow-up.

METHODS

Study population

The Nurses’ Health Study is an ongoing prospective cohort study of women in the U.S. who were 30 to 55 years of age when the study was initiated in 1976 (34, 35). Of the 238 026 potentially eligible registered nurses who were contacted by mail at study initiation, 65 241 were excluded for having questionnaires that were returned as unforwardable and 372 died, leaving 121 701 (70.6%) who responded to the baseline questionnaire. Every two years, follow-up questionnaires are mailed to participants in order to obtain updated information on medical history, diet, lifestyle habits, and other health behaviors, with a response rate of at least 90% in each follow-up cycle. All participants provided written informed consent. The Nurses’ Health Study, and the analysis described here, was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee. Further details on the design and analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study can be obtained elsewhere (34, 35).

Mortality ascertainment

The primary outcome of interest was suicide mortality, assessed continuously during the course of the study until June 1, 2010. Deaths were identified using reports from next of kin and by searching state mortality files and the U.S. National Death Index, a method that has been shown to have 98% sensitivity and 100% specificity for ascertainment of deaths (36, 37). Physicians blinded to exposure status reviewed death certificates and hospital or pathology reports to classify individual causes of death. Deaths caused by self-inflicted injuries were classified according to the underlying causes listed on the death certificate. For the present study, we specifically examined deaths in the “Suicide and Self-Inflicted Injury” cluster (codes E950-E959) of the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8).

Exposure assessment

The primary exposure of interest was social integration, measured with a seven-item index that included questions about marital status, social network size, frequency of contact with social ties, and participation in religious or other social groups (38, 39). The responses to these seven items yield a total score from 1 to 12 that is typically analyzed as a four-level categorical variable (eTable 1). At baseline, the index demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha=0.78). Additional psychometric analyses (40) and evidence of the construct validity of the social integration index (41, 42) have been described elsewhere. Because the index was not added to the Nurses’ Health Study survey instrument until 1992 (and then again in 1996), we considered 1992 as the baseline year in our analysis. At this time point, the participants in the Nurses’ Health Study were 46 to 71 years of age.

Statistical analysis

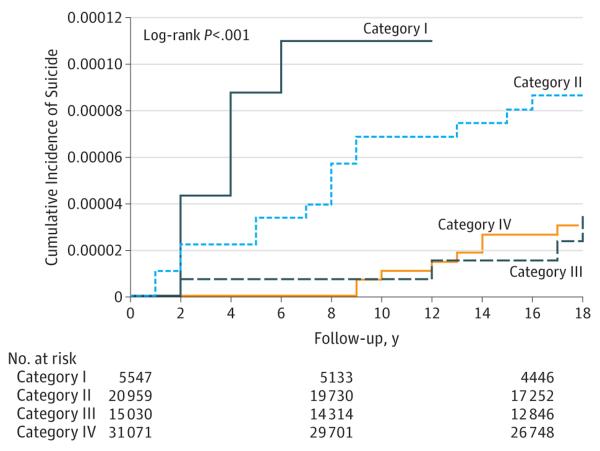

All statistical analyses were performed with the use of the SAS software package (version 9.2, SAS Institute). Each participant was followed up from the return of the 1992 questionnaire until either death or the end of follow-up (June 1, 2010), whichever occurred earlier. We plotted the cumulative incidence of suicide across different categories of social integration, using a test statistic based on the nonparametric maximum likelihood estimator of the subdistribution hazard to compare cumulative incidence across categories (43).

To estimate the association between social integration and suicide, we fit a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model to the data (44), using the independent increment model to handle time-updated variables efficiently (45). Under this data structure, a new data record was created for every questionnaire cycle at which a participant was at risk for suicide, with covariates set to their values at the time the questionnaire was returned. To adjust for potential confounding by age, calendar time, and any potential two-way interactions between these time scales, we stratified the analysis jointly by age in months at start of follow-up and calendar year of the questionnaire cycle. The time scale for the analysis was then measured in months since the start of the current questionnaire cycle. We also adjusted our estimates for the following time-updated covariates: employment status (46), family history of alcoholism, body mass index (47, 48), weekly physical activity (49), alcohol intake (50), caffeine intake (51-53), smoking status (54), and history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or hypercholesterolemia (55, 56). To test for linear trends across categories of exposure, we modeled the median values within each category of exposure.

To assess the extent to which different trajectories of social integration (57) may affect subsequent risk of suicide, we fit multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models with participants classified into one of 5 different groups based on their levels of social integration in 1992 and 1996: (a) no change in social integration, remaining in the lowest category [I] in both 1992 and 1996; (b) decline in social integration from 1992 to 1996; (c) no change in social integration, remaining in an intermediate category [II or III] in both 1992 and 1996; (d) increase in social integration from 1992 to 1996; or (e) no change in social integration, remaining in the highest category [IV] in both 1992 and 1996. In this analysis of social integration trajectories, 1996 was specified as the baseline year, and the incidence of suicide was assessed during the 14-year period between the return of the 1996 questionnaire and June 1, 2010.

Sensitivity analyses

To determine whether our findings were robust to the specific form of the social integration index that was used, we conducted sensitivity analyses specifying social integration as a continuous variable and disaggregated into its constituent components. We conducted several additional sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our estimates to additional sources of potential confounding. First, severe medical conditions have been shown to have a positive association with suicide risk (58-60), and poor health has been shown to compromise social relationships (57, 61, 62). We therefore refitted the multivariable regression models after excluding participants who at baseline had reported a history of cancer (specifically, any type of cancer with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancer) or a serious cardiovascular condition (specifically, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, or stroke). Second, poor mental health may confound the observed relationship between social integration and suicide (17, 18, 20). We therefore refitted the regression models after excluding participants who at baseline had poor mental health status, defined as a score of ≤52 on the 5-item Mental Health Inventory (63, 64). The Nurses’ Health Study also included two variables for self-reported antidepressant medication use and self-reported physician-diagnosed depression, but these two variables were not added to the survey until 1996; therefore the sensitivity analyses for these variables adopted 1996 as the baseline year. In addition, instead of excluding these participants from analysis we also conducted sensitivity analyses in which we adjusted for these conditions as baseline covariates.

RESULTS

Of 121 701 women initially enrolled into the Nurses’ Health Study, 104 064 (85.5%) remained under follow-up in 1992. Of these, 72 607 women (69.8%) responded to the social integration questions in the 1992 survey and therefore constituted the primary sample for analysis. Compared to non-responders, responders had a lower incidence of suicide during the subsequent 18 years of follow-up (4 suicides vs. 5 suicides per 100 000 person-years; Mantel-Haenszel rate ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46 to 1.27), but the difference was not statistically significant. Baseline summary statistics for the sample are provided in Table 1. The social integration index had a mean value of 6.62 (standard deviation, 3.11). The majority of participants were classified into the highest (31 071 [42.8%]) category of social integration. Socially isolated (i.e., less socially integrated) women were more likely to be employed full time, were less physically active, consumed more alcohol and caffeine, and were more likely to smoke compared with socially integrated women.

Table 1.

Adjusteda baseline sample characteristics of women in the Nurses’ Health Study, by social integration category measured in 1992

|

Social integration category

b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I (lowest) (n=5 547) |

II (n=20 959) |

III (n=15 030) |

IV (highest) (n=31 071) |

|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 57.9 (7.1) | 58.5 (7.3) | 57.8 (7.1) | 58.6 (7.1) |

| Race/ethnic white, (%) | 97.6 | 97.6 | 98.0 | 97.9 |

| Employment status,(%) | ||||

| Not employed outside the home/Retired | 23.2 | 26.4 | 29.4 | 31.8 |

| Employed part-time | 14.2 | 17.5 | 20.8 | 22.2 |

| Employed full-time | 50.0 | 44.7 | 40.1 | 36.5 |

| Missing | 12.6 | 11.3 | 9.8 | 9.5 |

| Family history of alcoholism, (%) | 23.6 | 23.1 | 21.2 | 19.9 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.2 (5.5) | 26.1 (5.2) | 25.9 (4.9) | 26.1 (4.9) |

| Physical activity, METs/wk c | 16.2 (21.8) | 17.8 (21.6) | 19.7 (24.1) | 20.4 (23.8) |

| Alcohol intake, g/day | 6.5 (12.3) | 5.5 (10.2) | 5.5 (9.4) | 4.5 (8.4) |

| Caffeine intake, g/day | 297 (234) | 275 (227) | 265 (218) | 240 (212) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 31.9 | 39.1 | 40.9 | 50.6 |

| Former | 42.6 | 43.2 | 44.7 | 39.8 |

| Current, 1-14 cigarettes/day | 8.1 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 4.6 |

| Current, 15-24 cigarettes/day | 10.6 | 7.4 | 5.8 | 3.6 |

| Current, 25 or more cigarettes/day | 6.8 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| History of hypertension, (%) | 37.1 | 35.0 | 34.6 | 33.2 |

| History of diabetes, (%) | 7.1 | 6.0 | 5.2 | 5.1 |

| History of hypercholesterolemia, (%) | 45.1 | 45.9 | 45.7 | 46.0 |

Values are means (SD) or percentages and are standardized to the age distribution of the study population.

Construction of the social integration index is described in Am J Epidemiol 1979;109:186-204.

METs/wk = metabolic equivalent of tasks per week.

Over 1 209 366 person-years of follow-up, there were 43 suicide events. The most frequently occurring means of suicide were poisoning by solid or liquid substances (21 [48.8%]), followed by firearms and explosives (8 [18.6%]) and strangulation and suffocation (6 [14.0%]). The cumulative incidence of suicide was highest among the most socially isolated women (Figure 1). Gray’s (43) test rejected the null hypothesis that the cumulative incidence functions were equal across categories (P<0.001). The same pattern was observed in estimates from the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for covariates (Table 2). The hazard of suicide was lowest among participants in the highest (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 0.23; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.59) and second-highest (AHR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.74) categories of social integration. A decreasing trend was observed across the categories (Ptrend=0.001).

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of suicide among women in the Nurses’ Health Study.

The follow-up period is 1992-2010, with estimates of suicide incidence stratified by social integration category measured in 1992.

Table 2.

Relative hazard ratios for suicide (95% CI) among women in the Nurses’ Health Study, 1992-2010, by social integration category measured in 1992

| Adjusted for age | Adjusted for age and other variables a |

|

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Social integration category b | ||

| I (lowest) | Ref | Ref |

| II | 0.43 (0.20-0.94) | 0.51 (0.23-1.16) |

| III | 0.21 (0.08-0.59) | 0.26 (0.09-0.74) |

| IV (highest) | 0.17 (0.07-0.42) | 0.23 (0.09-0.59) |

| Ptrend | <0.001 | 0.002 |

Estimates were adjusted for age; employment status (not employed outside the home or retired, employed part-time outside the home, employed full-time outside the home); family history of alcoholism (y/n); body mass index (<20, 20-24.9, 25–29.9, 30–34.9, ≥35 kg/m2); physical activity in metabolic equivalent of tasks per week (quintiles); caffeine intake (g/day); alcohol intake (g/day); smoking status (never, former, and current in categories of 1-14, 15-24, and ≥25 cigarettes per day); and baseline history of diabetes, hypertension, or hypercholesterolemia (yes/no).

Construction of the social integration index is described in Am J Epidemiol 1979;109:186-204.

For the analysis of changes in social integration from 1992 to 1996, 65 507 participants were included (Table 3). Over these 4 years, the mean change in the social integration index was −0.21 (standard deviation, 2.50); 14 231 (22.7%) participants experienced a decline in social integration, 11 068 (16.9%) participants experienced an increase in social integration, and 40 208 (61.4%) participants experienced no change. Participants who were categorized as having the highest level of social integration in both 1992 and 1996 had a reduced hazard of suicide over the subsequent 14 years of follow-up (AHR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03 to 0.65), while other trajectories of social integration were less protective; a decreasing trend across trajectory categories was observed (Ptrend=0.03).

Table 3.

Relative hazard ratios for suicide (95% CI) among women in the Nurses’ Health Study, 1996-2010, by social integration trajectory from 1992 to 1996

| Adjusted for age | Adjusted for age and other variables a | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Social integration trajectory from 1992 to 1996 b | ||

| No change, remained in lowest category (I) in 1992 & 1996 | Ref | Ref |

| Decline from 1992 to 1996 | 0.35 (0.10-1.20) | 0.37 (0.10-1.34) |

| No change, remained in intermediate category (II or III) in 1992 & 1996 | 0.22 (0.06-0.81) | 0.24 (0.06-0.97) |

| Increase from 1992 to 1996 | 0.25 (0.06-1.01) | 0.29 (0.07-1.25) |

| No change, remained in highest category (IV) in 1992 & 1996 | 0.13 (0.03-0.53) | 0.15 (0.04-0.65) |

| Ptrend | 0.01 | 0.02 |

Estimates were adjusted for all socio-demographic, health behavior, and medical history variables listed in Table 2.

Construction of the social integration index is described in Am J Epidemiol 1979;109:186-204.

The sensitivity analyses did not substantively alter our findings. When the social integration index was specified as a continuous variable, each one point difference in the index was associated with an 18% lower relative hazard of suicide (AHR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.74 to 0.92). When we disaggregate the social integration index into its constituent components, no single dimension of social integration appeared to drive our findings (eTable 2). The estimates remained qualitatively similar when we excluded participants who at baseline had poor mental health status or had a history of cancer or a serious cardiovascular condition or when we adjusted for these factors as covariates (eTables 3 and 4), or when we excluded participants who at baseline reported antidepressant medication use and/or a history of physician-diagnosed depression (or when we adjusted for these factors as covariates) (eTable 5).

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal study of 72 607 women in the U.S., we found that social integration at baseline was associated with a lower risk of suicide over 18 years of follow-up. The association was statistically significant, even stronger in magnitude than that observed in our recently published study of social integration and suicide among men (16), and robust to several sensitivity analyses. Furthermore, excluding participants with poor mental health status, as measured at baseline by several different indicators, did not overturn the observed associations.

There are a number of important strengths and weaknesses to our study. First, this analysis was based on long-term follow-up data derived from a well-characterized, nationwide, population-based cohort. However, the participants in the Nurses’ Health Study are also racially, generationally, and socioeconomically homogeneous. Second, U.S. national suicide rates exceed the incidence rate observed in our sample (1), suggesting a lower overall level of psychiatric morbidity. These two points suggest important limitations in the generalizability of our findings, given the higher socioeconomic status and lower psychiatric morbidity of the study participants relative to the general population. Third, in contrast to our previously published study on social integration and suicide mortality among men (16), these data contained multiple indicators of mental health status. Adjustment for the potentially confounding effects of poor mental health did not appreciably change our estimates. Although the 5-item Mental Health Inventory is only a screening measure, it has been shown to have excellent sensitivity and specificity for detecting major depressive disorder (63, 64). Similarly, recall for “self-reported, physician-diagnosed” chronic conditions has been shown to be accurate when compared with medical record review (55, 65, 66). Fourth, relatively few suicide events were observed, with only 43 suicides occurring in the study sample over the 18-year follow-up period, thereby limiting our ability to detect statistically significant associations in the analysis of social integration trajectories. We also attempted to disaggregate the social integration index into its individual components but were similarly limited by small cell sizes. Nonetheless, the number of events observed in our study was larger than any other previously published study of suicide among women with comparable data on social determinants (26). Fifth, although our exposure variable has been previously validated and is frequently used in the literature, the social integration index fails to capture a number of different aspects of social integration, such as relationship quality, degree of reciprocity, geographic proximity, or network density (67-73). Sixth, unobserved confounding could potentially explain the estimated associations. Even with adjustment for age, adverse health behaviors and chronic conditions were less prevalent among women who were socially well-integrated. Thus it is possible that social integration may, to a certain extent, be a proxy for good health -- which is a known protective factor against suicide (58-60).

Classically, researchers have argued that men may be more advantaged by social relationships compared with women (74-77). Although our primary finding may be interpreted as standing in contrast to this earlier body of literature, it is also possible that the social integration index used in our analysis systematically captured supportive relationships while ignoring negative aspects of these relationships (76-78) and that a scale that captures both positive and negative aspects of social relationships may have yielded more nuanced results. It is also possible that social integration may have differential associations with suicide vs. suicide ideation or attempts, and that its association with suicidal behavior overall (e.g., a composite outcome that includes suicide ideation, suicide attempts, or suicide) among women may be muted.

Our study has important implications for suicide prevention. Guidelines for clinical practice have generally focused on suicide risk screening, assessment, and treatment (79-82). Our study confirms some of the prior studies that have informed these guidelines in emphasizing the importance of social isolation as a potential risk factor for suicide. In clinical practice, asking patients about the extent of their participation in a range of social relationships may yield information useful for risk assessment or in developing tailored interventions aimed at strengthening social relationships to be more functional and satisfying. In addition to individually targeted approaches, however, our findings suggest that a public health approach to suicide prevention may also be of benefit. As Knox et al. (83) and Knox (84) have convincingly argued, based in part on the classic argument by Rose (85) for shifting the entire population distribution of disease, community-based interventions may be able to reduce the overall burden of suicide more effectively than intensive efforts focused on “high-risk” individuals. For example, health and social policy may be used to promote certain types of social ties, increase civic engagement, develop public spaces for group activities, or reduce relationship strain (86). Clearly, the “high-risk” and “population strategy” approaches each have their advantages and disadvantages, and the optimal prevention strategy likely requires a judicious mix of both (87).

CONCLUSIONS

Although it has been frequently assumed that social integration has an inverse association with poor mental health outcomes, including suicide, most evidence in support of this hypothesis has been based on aggregate data. Our study strongly suggests that social integration has a protective association against suicide risk for women, even after adjustment for multiple indicators of poor mental health. Interventions aimed at strengthening existing social network structures, or creating new ones, may be valuable programmatic tools in the primary prevention of suicide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues in the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and at Harvard Medical School for their assistance with collecting and managing the Nurses’ Health Study data and for reviewing the analysis protocol, findings, statistical code, and manuscript.

ACT and ML had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The Nurses’ Health Study was funded by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) UM1 CA186107. This analysis was additionally supported through a Seed Grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health and Society Scholars Program. The authors also acknowledge salary support from NIH K23MH096620 and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health and Society Scholars Program. The sponsors of the study had no role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributions: ACT conceived the idea for the study, designed the analysis, analyzed the results, and drafted the manuscript. ML managed the dataset, performed the statistical analysis, analyzed the results, and co-wrote the manuscript. IK interpreted the results and co-wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation have provided financial support for the submitted work; (2) no authors have relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) no authors have any non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;60(6):1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan EM, Annest JL, Luo F, Simon TR, Dahlberg LL. Suicide among adults aged 35-64 years -- United States, 1999-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(17):321–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;380(9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, Coutts A, McKee M. The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barr B, Taylor-Robinson D, Scott-Samuel A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Suicides associated with the 2008-10 economic recession in England: time trend analysis. BMJ. 2012:345e5142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang SS, Stuckler D, Yip P, Gunnell D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ. 2013:347f5239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawton K, Haw C. Economic recession and suicide. BMJ. 2013:347f5612. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein MM, Kim HM, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1152–1158. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maciejewski DF, Creemers HE, Lynskey MT, Madden PA, Heath AC, Statham DJ, et al. Overlapping genetic and environmental influences on nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation: different outcomes, same etiology? JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):699–705. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durkheim E. Le suicide: etude de sociologie. 2nd ed. Presses Universitaires de France; Paris: 1967. (1st ed., 1897) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai AC, Lucas M, Sania A, Kim D, Kawachi I. Social integration and suicide mortality among men: 24-year cohort study of U.S. health professionals. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(2):85–95. doi: 10.7326/M13-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry. 1976;39(1):28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. J Abnorm Psychol. 1976;85(2):186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):868–876. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gove W, Hughes M. Possible causes of the apparent sex differences in physical health: an empirical investigation. Am Sociol Rev. 1979;44(1):126–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umberson D, Chen MD, House JS, Hopkins K, Slaten E. The effect of social relationships on psychological well-being: are men and women really so different? Am Sociol Rev. 1996;61(5):837–857. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, McLeod JD. Sex differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. Am Sociol Rev. 1984;49(5):620–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kposowa AJ. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(4):254–261. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.4.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008:30133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleiman EM, Liu RT. Prospective prediction of suicide in a nationally representative sample: religious service attendance as a protective factor. Br J Psychiatry. 2014:204262–266. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gravseth HM, Mehlum L, Bjerkedal T, Kristensen P. Suicide in young Norwegians in a life course perspective: population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(5):407–412. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.083485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bearman PS, Moody J. Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):89–95. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunnell D, Hawton K, Ho D, Evans J, O’Connor S, Potokar J, et al. Hospital admissions for self harm after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care: cohort study. BMJ. 2008:337a2278. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holma KM, Melartin TK, Haukka J, Holma IA, Sokero TP, Isometsa ET. Incidence and predictors of suicide attempts in DSM-IV major depressive disorder: a five-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):801–808. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tidemalm D, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P, Runeson B. Risk of suicide after suicide attempt according to coexisting psychiatric disorder: Swedish cohort study with long term follow-up. BMJ. 2008:337a2205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Runeson B, Tidemalm D, Dahlin M, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N. Method of attempted suicide as predictor of subsequent successful suicide: national long term cohort study. BMJ. 2010:341c3222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler RC, Warner CH, Ivany C, Petukhova MV, Rose S, Bromet EJ, et al. Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US Army soldiers: the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):49–57. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belanger C, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH, Rosner B, Willett W, Bain C. The nurses’ health study: current findings. Am J Nurs. 1980;80(7):1333. doi: 10.1097/00000446-198007000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belanger CF, Hennekens CH, Rosner B, Speizer FE. The nurses’ health study. Am J Nurs. 1978;78(6):1039–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Dysert DC, Lipnick R, Rosner B, et al. Test of the National Death Index. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119(5):837–839. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the National Death Index and Equifax Nationwide Death Search. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(11):1016–1019. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkman LF. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a follow-up study of Alameda County residents [dissertation] University of California at Berkeley; Berkeley: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berkman LF, Breslow L. Health and ways of living. Oxford University Press; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaefer C, Coyne JC, Lazarus RS. The health-related functions of social support. J Behav Med. 1981;4(4):381–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00846149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodenow C, Reisine ST, Grady KE. Quality of social support and associated social and psychological functioning in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Health Psychol. 1990;9(3):266–284. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gray RJ. A class of k-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Statist. 1988;16(3):1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of survival data. Chapman and Hall; London: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. Springer-Verlag New York, Inc.; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis G, Sloggett A. Suicide, deprivation, and unemployment: record linkage study. BMJ. 1998;317(7168):1283–1286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mukamal KJ, Miller M. Invited commentary: Body mass index and suicide--untangling an unlikely association. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(8):900–904. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq278. discussion 905-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukamal KJ, Rimm EB, Kawachi I, O’Reilly EJ, Calle EE, Miller M. Body mass index and risk of suicide among one million US adults. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):82–86. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1fa2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinto Pereira SM, Geoffroy MC, Power C. Depressive symptoms and physical activity during 3 decades in adult life: bidirectional associations in a prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12):1373–1380. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: an empirical review of cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(SupplS):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawachi I, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE. A prospective study of coffee drinking and suicide in women. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(5):521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lucas M, Mirzaei F, Pan A, Okereke OI, Willett WC, O’Reilly EJ, et al. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of depression among women. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1571–1578. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lucas M, O’Reilly EJ, Pan A, Mirzaei F, Willett WC, Okereke OI, et al. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of completed suicide: results from three prospective cohorts of American adults. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2014;15(5):377–386. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2013.795243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lucas M, O’Reilly EJ, Mirzaei F, Okereke OI, Unger L, Miller M, et al. Cigarette smoking and completed suicide: results from 3 prospective cohorts of American adults. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):1053–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Colditz GA, Martin P, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Sampson L, Rosner B, et al. Validation of questionnaire information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123(5):894–900. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Druss B, Pincus H. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in general medical illnesses. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(10):1522–1526. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cerhan JR, Wallace RB. Predictors of decline in social relationships in the rural elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(8):870–880. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA, Sparen P, Ye W, Adami HO, et al. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(14):1310–1318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stenager EN, Madsen C, Stenager E, Boldsen J. Suicide in patients with stroke: epidemiological study. BMJ. 1998;316(7139):1206. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Larsen KK, Agerbo E, Christensen B, Sondergaard J, Vestergaard M. Myocardial infarction and risk of suicide: a population-based case-control study. Circulation. 2010;122(23):2388–2393. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.956136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cornwell B. Good health and the bridging of structural holes. Soc Networks. 2009;31(1):92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schafer MH. Structural advantages of good health in old age: investigating the health-begets-position hypothesis with a full social network. Res Aging. 2013;35(3):348–370. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE, Jr., Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care. 1991;29(2):169–176. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weinstein MC, Berwick DM, Goldman PA, Murphy JM, Barsky AJ. A comparison of three psychiatric screening tests using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Med Care. 1989;27(6):593–607. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Stason WB, Rosner B, Hennekens CH, et al. Reproducibility and validity of self-reported menopausal status in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126(2):319–325. doi: 10.1093/aje/126.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barr RG, Herbstman J, Speizer FE, Camargo CA., Jr. Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort study of nurses. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(10):965–971. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berkman LF. Assessing the physical health effects of social networks and social support. Annu Rev Public Health. 1984:5413–432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.05.050184.002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berkman LF. Social networks, support, and health: taking the next step forward. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123(4):559–562. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berkman LF. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom Med. 1995;57(3):245–254. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsai AC, Papachristos AV. From social networks to health: Durkheim after the turn of the millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2015;125(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.House JS, Umberson D, Landis KR. Structures and processes of social support. Annu Rev Sociol. 1988;14(1):293–318. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Belle DE. The impact of poverty on social networks and supports. Marr Fam Rev. 1983;5(4):89–103. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kessler RC, McLeod JD, Wethington E. The costs of caring: a perspective on the relationship between sex and psychological distress. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: theory, research and applications. Martinus Mijhoff Publishers; The Hague: 1985. pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rook KS. The negative side of social interaction: impact on psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984;46(5):1097–1108. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Antonucci TC, Akiyama H, Lansford JE. Negative effects of close social relations. Fam Relations. 1998;47(4):379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(4):472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morriss R, Kapur N, Byng R. Assessing risk of suicide or self harm in adults. BMJ. 2013:347f4572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O’Connell H, Chin AV, Cunningham C, Lawlor BA. Recent developments: suicide in older people. BMJ. 2004;329(7471):895–899. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7471.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.LeFevre ML, Force USPST Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(10):719–726. doi: 10.7326/M14-0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O’Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, Soh C, Whitlock EP. Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(10):741–754. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Knox KL, Conwell Y, Caine ED. If suicide is a public health problem, what are we doing to prevent it? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):37–45. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Knox K. Approaching suicide as a public health issue. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(2):151–152. doi: 10.7326/M14-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282(6279):1847–1851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(SupplS):54–66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rose G. The strategy of preventive medicine. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1992. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.