Abstract

Microsporidia, which belong to the kingdom Fungi, are important opportunistic pathogens in HIV-infected populations and organ transplant recipients that are often associated with a broad range of symptoms, such as diarrhea, nephritis, and encephalitis. Natural infection occurs via the oral route, and as a consequence, gut immunity plays an important role in restricting the dissemination of these pathogens. Studies from our laboratory have reported that the pathogens induce a rapid intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) response important for host protection. Although mucosal dendritic cells (DC) are likely involved in triggering an antigen-specific IEL response, the specific subset(s) responsible has yet to be identified. Toward this goal, we demonstrate a very important role for mucosal CD11b− CD8+ DC in the initiation of an antigen-specific IEL in vivo. Effectively, after Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection, CD11b− CD8+ DC were activated in the lamina propria (LP) and acquired the ability to process retinoic acid (RA). However, this subset did not produce interleukin 12 (IL-12) but upregulated CD103, which is essential for migration to the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN). Interestingly, CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ DC in the MLN, in addition to processing RA, also secreted IL-12 and were responsible for gut imprinting specificity on mucosal CD8 T cells. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the importance of MLN CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ DC isolated from infected animals in the generation of an IEL response against a live pathogen.

INTRODUCTION

Human microsporidiosis is an opportunistic infection caused by a spore-forming unicellular eukaryote related to fungi, most specifically zygomycetes (1). Of the 14 species infecting humans, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Encephalitozoon intestinalis, Encephalitozoon cuniculi, and Encephalitozoon hellem are the most common (2). The incidence of microsporidia in HIV patients remains very high, especially in places such as Russia, Venezuela, and Thailand, where microsporidium prevalence ranges from 13 to 80% (3–5). Lately, it has been reported that microsporidial infections can cause complications in non-HIV populations, especially those receiving organ transplants (6–9). In a very recent study, Kotkova et al. demonstrated that microsporidiosis was probably a latent infection, which could reactivate in an immunocompromised situation, further highlighting the importance of studying the immune response against this ubiquitous pathogen (10).

An experimental murine model using E. cuniculi mimics the human infection and has commonly been used to investigate the host immune response (11). Most microsporidial species are acquired by ingesting contaminated water or food, and the gut immunity to this pathogen still remains cryptic. Intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) form one of the first lines of immune defense in the gut tissue (12), and their protective role against various pathogens has been reported (13–16). Previous studies from our laboratory demonstrated early and rapid induction of the IEL response after microsporidial infection (17). This response, characterized by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) expression and perforin-mediated cytotoxic activity, was able to confer partial protection on an immunosuppressed host (17, 18). The role of dendritic cells (DC) in priming the adaptive immune response is well established (19), but the complex composition of the DC population in the gut has made the task of identifying the subset(s) involved in eliciting the IEL response against oral pathogens challenging. Recently, CD103 expression by gut mucosal DC identified a subset with migratory capability (20), and due to their ability to process retinoic acid (RA), these cells induce selective imprinting of T cells with gut-homing receptors α4β7 and CCR9 (21). Also, studies from our laboratory suggested that the IEL response is very likely dependent on IFN-γ-producing DC, since in vitro stimulation of naïve splenic CD8 T cells by DC from the Peyer's patches (PP) of IFN-γ−/− mice failed to upregulate IFN-γ and CCR9 expression, and cells did not traffic efficiently to the intestinal epithelium (18). In this report, for the first time, in vivo studies demonstrate that CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ mucosal DC originating in the lamina propria (LP) are critical for priming an IEL response against E. cuniculi infection in vivo. This DC subset was activated in the intestinal LP after E. cuniculi infection and subsequently migrated to the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN). While the CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ DC in the LP upregulated retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH), this subset could produce interleukin 12 (IL-12), essential for CD8 IEL priming, only after migrating to the MLN. Finally, we demonstrate that while all mucosal DC subsets have the ability to acquire antigen in vivo, the CD103+ RALDH+ IL-12+ CD11b− CD8+ subset exclusively triggers an antigen-specific IEL response in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and parasites.

C57BL/6 mice (National Cancer Institute), IL-12p40 YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) reporter mice, CD11c DTR (diphtheria toxin receptor) EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) mice, and YFP IFN-γ reporter (great) mice (Jackson Laboratory) were housed at the Animal Research Facility at The George Washington University (Washington, DC) under conditions approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. For in vivo treatment with FTY720, the animals received 30 μg of FTY720 by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection 6 h before infection and had ad libitum access to drinking water complemented with FTY720 (3.3 μg/ml) until the termination of the experiment. CD11c DTR conditional knockout mice were depleted of DC by intraperitoneal injection of diphtheria toxin (100 ng/mouse) 6 h prior to infection.

E. cuniculi (genotype III) was provided by L. Weiss (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY). Unless otherwise specified, animals were infected orally or intraperitoneally with 2 × 107 spores/mouse.

An antigenic extract was prepared by mechanical disruption of freshly harvested E. cuniculi spores with 0.5-mm zirconia/silica beads in a Mini-Beadbeater (BioSpec Products Inc.). Insoluble antigens were removed by centrifugation before sterile filtration.

Flow cytometry.

Unless otherwise specified, LIVE/DEAD Aqua staining (Invitrogen) was systematically performed prior to any flow cytometry analysis. Cells were acquired with a FACSCalibur cytometer with a Cytek upgrade (Becton Dickinson [BD], Cytek Development Inc.). Cell sorting was carried out with a BD FACSAria cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar). Fluorescence Minus One controls were performed for most of the experiments.

In some experiments, RALDH was detected by a flow cytometry assay using Aldefluor (Stemcell Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In the presence of RALDH, the substrate is retained in the cells, and the amount of fluorescent product detected is proportional to the RALDH activity in the cells. Diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB), a specific inhibitor of RALDH, was used as a control for background fluorescence.

Parasite burden.

Guts, livers, and spleens were harvested from infected animals, and DNA was extracted with a DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with primers specific for the E. cuniculi small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene (5′-TGTGAGACCCTTTGACGGTGTTCT-3′ and 5′-ACATTCAAAGCAGCTTCGTCAGCC-3′) and SsoAdvanced SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad) on a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ thermal cycler under the following conditions: 5 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 45 s at 95°C and 50 s at 58.5°C. Parasite DNA equivalents were amplified concomitantly to generate a standard curve. The limit of detection of the assay was 5 spores.

For the detection of parasites in stools, fecal samples were collected every other day, and DNA was isolated by using a QIAamp DNA stool minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's specifications. Samples were analyzed by real-time PCR as described above.

Preparation of LP and MLN cell suspensions for flow cytometry.

MLN were harvested, and a single-cell suspension was obtained as described previously (22). An intestinal LP cell suspension was prepared according to a published protocol (23) with some modifications. Briefly, small intestines were collected and were flushed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and Peyer's patches were excised. Epithelial cells were removed by incubation in RPMI medium with 10% bovine serum, 5 mM EDTA, and 15 mM HEPES. Subsequently, a single-cell suspension was prepared by digestion with a combination of collagenase D and DNase I before labeling for flow cytometry analysis or cell sorting.

Isolation of LP and MLN DC.

Cell suspensions obtained as described above were further enriched using a Nycodenz gradient, followed by negative selection for CD3, CD19, and NK1.1 with an EasySep biotin selection kit (Stemcell Technologies) as recommended by the manufacturer. Live CD11b+ CD8− and CD11b− CD8+ DC from both the MLN and the LP were sorted after live/dead staining with Sytox Blue (Invitrogen).

Assay for splenic CD8+ T cell restimulation by mucosal DC subsets.

Splenic immune CD8+ T cells were isolated from mice infected with 2 × 107 irradiated E. cuniculi spores (300 kilorads) and subsequently challenged twice (5 × 106 irradiated spores) at 3-week intervals. Bone marrow-derived DC (BMDC) prepared as described previously were used as a negative control (24). Animals were sacrificed 3 weeks after the last challenge, and splenic CD8+ T cells were purified using a biotinylated anti-CD8β antibody and an EasySep biotin selection kit (purity, ≥85%). A total of 2.5 × 104 DC were incubated with 106 CD8+ T cells overnight before the addition of monensin for 4 h, after which intracellular staining was performed.

IEL response after adoptive transfer of mucosal DC subsets.

CD11b+ CD8− or CD11b− CD8+ DC subsets (25,000 cells/mouse) were adoptively transferred via tail vein injection. Seven days later, IEL were isolated according to a protocol adapted from the work of Montufar-Solis and Klein (25).

For the in vitro functional assay, freshly isolated IEL were restimulated overnight with an antigenic extract (20 μg/ml) in the presence of an equal number of splenocytes from congenically marked CD45.1 mice. After incubation with CD107a and monensin, cells were labeled for flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± standard deviations. Comparisons between two groups were performed by Student's t test throughout the study.

RESULTS

Dissemination of E. cuniculi during oral versus intraperitoneal infection.

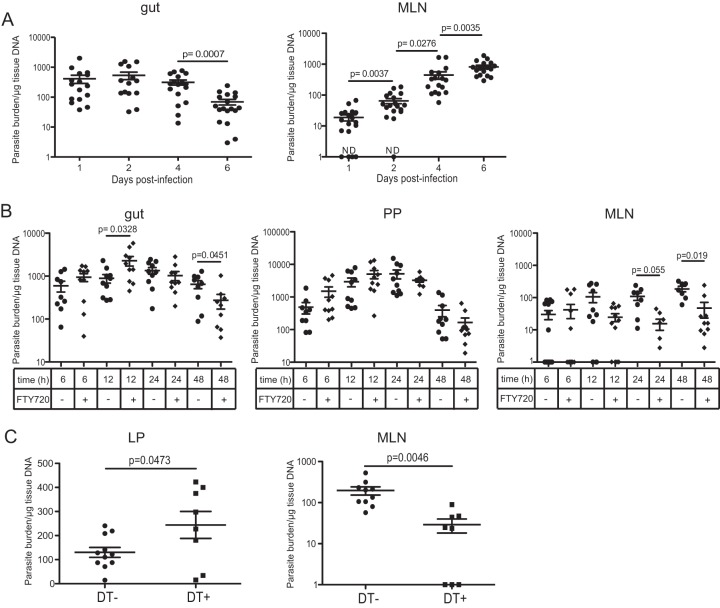

E. cuniculi is believed to be acquired primarily via the oral route and is characterized by the dissemination of spores to different organs, including, but not restricted to, the brain, liver, and kidneys (26). However, the early stages of propagation after oral infection have yet to be elucidated. We wanted to determine if the pattern of parasite dissemination was dependent on the route of infection. As expected, animals that received the pathogen via the oral route exhibited lower parasite burdens in the spleen and liver than mice receiving a similar infective dose via intraperitoneal (i.p.) challenge, suggesting an important role for the gut innate immune response in early control of the infection (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Interestingly, the levels of shedding of E. cuniculi spores in the stools were comparable irrespective of the route of infection (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material). To better analyze the early steps involved in the propagation of the pathogen, orally infected animals were sacrificed at different time points postinfection (p.i.), and the parasite burdens in the tissues (gut and MLN) were quantified by real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 1A, the number of E. cuniculi spores detected in the gut started to decrease at day 4 p.i., while concomitantly the number detected in the MLN increased steadily from day 1 until day 6 p.i., when the assay was terminated.

FIG 1.

Rapid dissemination of E. cuniculi after oral infection. C57BL/6 mice were orally infected with 2 × 107 E. cuniculi spores. (A) Parasite burdens in the gut and MLN were measured by real-time PCR. ND, not detectable. (B) Some of the animals were treated with FTY720 prior to infection, and parasite burdens in the gut, PP, and MLN were assessed. Data represent results of 2 to 3 pooled experiments with at least 4 mice/group. (C) CD11c DTR mice were either treated with diphtheria toxin (DT+) or left untreated (DT−) prior to oral infection with 2 × 107 E. cuniculi spores, and parasite burdens in the gut and MLN were determined at day 2 p.i. Data represent results of at least 2 experiments with 3 to 4 mice/group.

Previous studies have demonstrated that DC in the intestinal mucosa constantly migrate from the gut to the MLN, where they can initiate either immunity or tolerance (27). Moreover, these cells have been reported to be involved in the dissemination of various intracellular pathogens, such as Toxoplasma gondii, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (28–30). Studies were performed to determine if intestinal DC played a role in the transport of E. cuniculi spores to the peripheral tissues. For this purpose, mice were administered FTY720, a sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P) analog known to inhibit the egress of lymphocytes from lymphoid organs (31) and to modulate DC trafficking from the mucosa to the draining lymph nodes (32, 33). Treatment of the animals with FTY720 caused a significant rise in gut parasite burdens at 12 h (Fig. 1B), while levels in the MLN were reduced at 24 and 48 h p.i., suggesting that early dissemination of the parasite may be dependent on migration of DC, since they represent the primary subset emigrating from the gut mucosa (34). Importantly, treatment of E. cuniculi cultures with FTY720 in vitro had no adverse effect on their ability to infect or proliferate, ruling out the possibility of any toxic effect on the pathogen (data not shown).

To further establish the involvement of DC in the dissemination of the parasite, CD11c DTR (diphtheria toxin receptor) mice were utilized, because the injection of DT (diphtheria toxin) into these transgenic animals allows the conditional depletion of CD11c+ cells. As shown in Fig. 1C, treatment of CD11c DTR mice with DT significantly lowered the parasite burden in the MLN compared to that in untreated controls, while the number of spores in the lamina propria was increased. Therefore, depletion of CD11c+ cells compromised the dissemination of the parasite from the gut mucosa.

DC response to E. cuniculi infection.

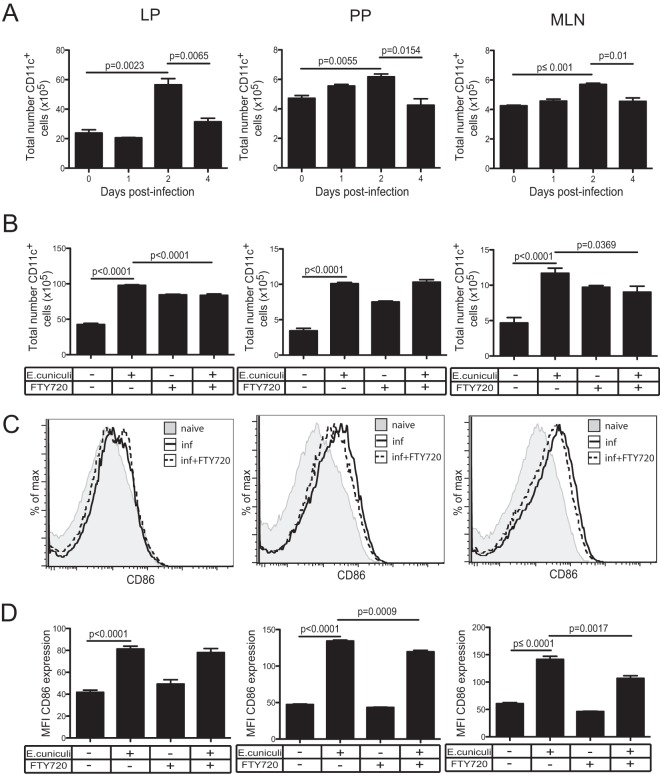

DC are known to be an essential component of the innate immune process and have the ability to present antigens to naïve T cells (19). As expected, phenotypic analysis shows significant increases in major histocompatibility complex class II-positive (MHC-II+) CD11c+ cell populations in the LP, MLN, and PP at day 2 p.i., which subsequently subside in all the tissues by day 4 p.i. (Fig. 2A). Treatment with FTY720 reduced the recruitment of these cells in both the MLN and the LP, even though DC egress from the tissue was diminished in the absence of infection (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the significant upregulation of CD86 on mucosal DC observed at day 2 p.i. was partially reversed by FTY720 treatment in the MLN and PP (Fig. 2C). It should be noted that the splenic CD11c response did not increase after oral infection and that these cells showed only a nominal increase in MHC-II expression, substantiating the absence of DC response in this organ at day 2 p.i. (see Fig. S2A to C in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

DC activation at different mucosal sites. (A) The total numbers of MHC-II+ CD11c+ cells in the LP, PP, and MLN of C57BL/6 mice were determined at different time points after oral E. cuniculi infection. (B) Mice were either left untreated or treated with FTY720, and the numbers of CD11c+ cells in the LP, PP, and MLN were assessed at day 2 p.i. (C) The expression of CD86 by CD11c+ cells was measured in the LP, PP, and MLN at day 2 p.i. Histograms are gated on total CD11c+ cells. inf, infected. (D) Graphs depict the average MFI of CD86 for CD11c+ DC in each respective organ. The experiment was performed twice, and the data represent results of one experiment.

Roles of CD11b+ CD8− and CD11b− CD8+ subsets after E. cuniculi infection.

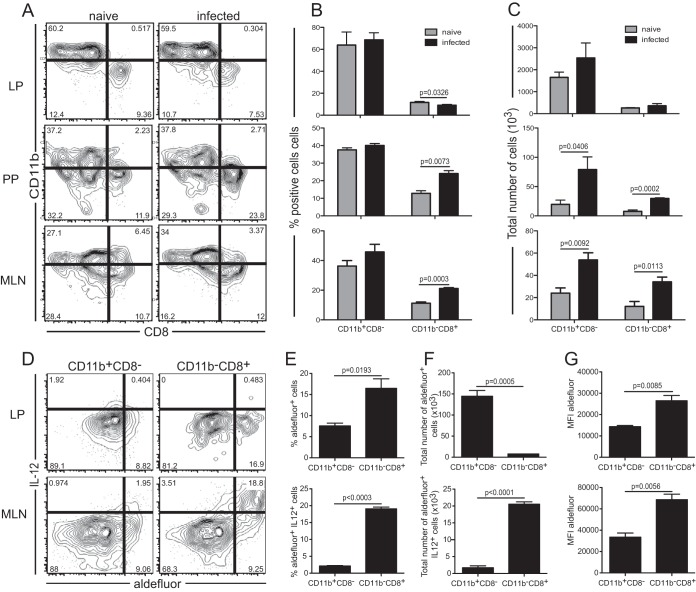

DC are a heterogeneous population that consists of two main subsets derived from distinct precursors, myeloid and lymphoid, based on the respective expression of the CD11b or CD8α marker (35). However, subsets in the gut mucosa are very complex, and the CD11c marker can be expressed by different cell types, including resident macrophages and eosinophils (36). Nonetheless, these cells do not have the ability to prime naïve T cells (37). The role of the systemic CD11b− CD8α+ DC subset in the production of IL-12, a cytokine important for the priming of effector T cell immunity (38), and in effective antigen presentation in response to intracellular pathogens is well established (39, 40). However, the function of this subset in the intestinal LP is not well defined, and these cells may induce regulatory T cell or Th1 differentiation (41, 42). To determine the potential roles of the various subsets in the gut tissue, MHC-II+ CD11c+ cells from the different intestinal draining organs were assayed for the expression of CD8α and CD11b at day 2 p.i. (Fig. 3A to C). The frequency of CD11b+ CD8− cells was not significantly elevated in response to infection in any of the tissues tested (Fig. 3A and B). However, increases in the absolute numbers for this subset were noted in both the MLN and the LP (Fig. 3C). Conspicuously, infection led to increases in both the frequency and the absolute number of the CD11b− CD8+ subset (Fig. 3B and C). This increase in the CD11b− CD8+ population in the MLN and PP was associated with the decline in the LP, suggesting that these cells might originate in the gut mucosa before trafficking to the PP and MLN.

FIG 3.

Responses of mucosal dendritic cell subsets. (A) IL-12p40 YFP mice were orally infected with 2 × 107 E. cuniculi spores, and phenotypic analysis of CD11b+ CD8− and CD11b− CD8+ subsets from the LP, PP, and MLN was conducted at day 2 p.i. Dot plots are gated on MHC-II+ CD11c+ DC. (B and C) Frequency (B) and total number (C) of cells for each DC subset. (D) RALDH activity and IL-12 expression in the CD11b+ CD8− and CD11b− CD8+ subsets from the LP and MLN. Dot plots are gated on the CD11b+ CD8− or CD11b− CD8+ subset from E. cuniculi-infected IL-12p40 YFP mice at day 2 p.i. (E and F) Average frequency (E) or total number (F) of IL-12+ Aldefluor-positive (MLN) or Aldefluor-positive (LP) cells for both the CD11b+ CD8− and CD11b− CD8+ DC subsets (n, 3 to 4 mice/group). (G) MFI of Aldefluor fluorescence for both DC subsets. Data represent results of at least 2 experiments with 3 mice/group.

One of the important functions of mature DC is IL-12 production, which has long been associated with optimal CD8+ T cell priming (38, 43). In addition, recent studies have reported that the gut mucosal DC play an essential role in the induction of preferential intestinal homing receptors α4β7 and CCR9 on T cells (44, 45). The imprinting of these receptors by intestinal DC is mediated by RA, which is produced by RALDH (20, 46). Therefore, in subsequent studies, we measured both IL-12 production, by using reporter mice, and RALDH expression, by Aldefluor fluorescence (37), in mucosal DC populations after E. cuniculi infection. In comparison to the CD11b+ CD8− population, a greater frequency of the CD11b− CD8+ subset in the LP exhibited RA-generating enzymes (Fig. 3D and E). However, the CD11b+ CD8− and CD11b− CD8+ subsets from the LP did not upregulate IL-12 expression in response to infection. On the other hand, in the MLN from infected animals, Aldefluor-positive IL-12+ cells were observed almost exclusively within the CD11b− CD8+ subset. Furthermore, based on the evaluation of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), the level of RALDH expression was greater in the MLN CD11b− CD8+ population than in the same subset from the LP (Fig. 3G). Administration of FTY720 to infected animals led to the accumulation of these cells in the LP, while both the number and the frequency of this subset were significantly reduced in the MLN (see Fig. S3A to C in the supplemental material). Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that a significant fraction of the MLN CD11b− CD8+ subset originates from the LP and that these cells acquire the ability to secrete IL-12 upon migrating from the intestinal mucosa to the MLN.

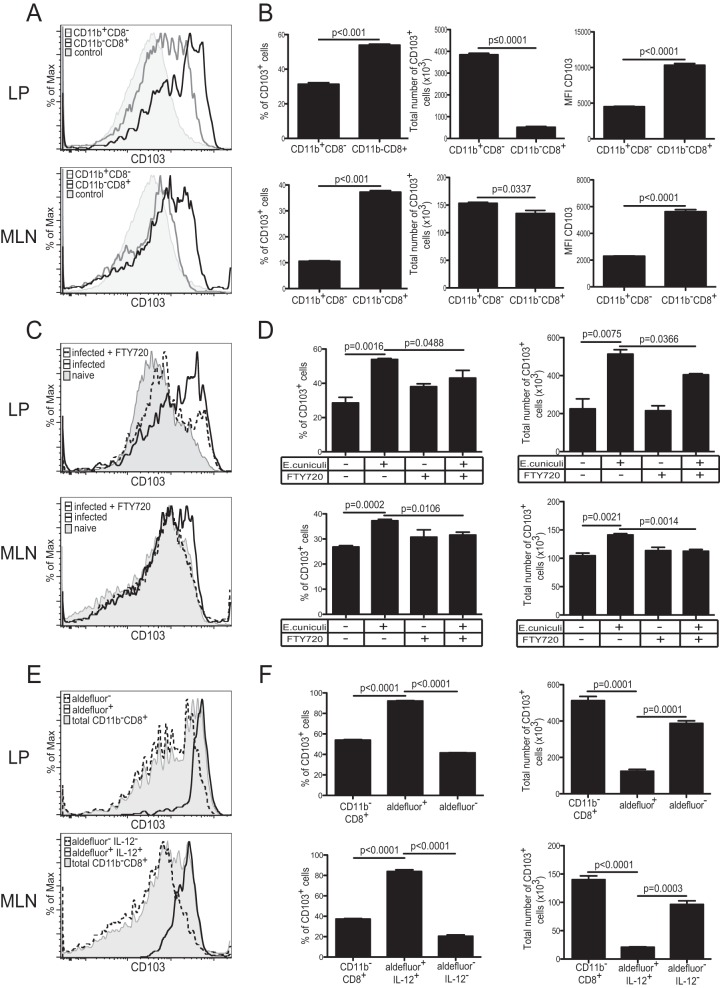

CD11b− CD8+ LP DC have enhanced migratory properties after infection.

Recent studies have demonstrated that CD103+ DC can migrate from the intestinal LP to the MLN under both steady-state and inflammatory conditions (37). Furthermore, CD103-expressing gut mucosal DC are believed to metabolize retinol exclusively (37) and consequently have been shown to play a critical role in the induction of homing receptors α4β7 and CCR9 on activated T cells (20). On the other hand, sessile macrophages are unable to upregulate CD103, allowing us to discriminate between CD11b+ CD8− CD11c+ DC and the macrophage population (37). Therefore, CD103 expression by the different DC subsets was assayed in the LP and MLN of infected animals. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, higher frequencies of CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ DC than of CD103+ CD11b+ CD8− DC were detected in both the LP and the MLN in response to E. cuniculi infection. Since CD11b− CD8+ DC constitute a minor population in both the MLN and the LP compared to the CD11b+ CD8− subset, the total number of CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ cells observed in both organs was significantly lower than that of CD103+ CD11b+ CD8− DC. However, the MFI for CD103 was notably higher in the CD11b− CD8+ population in both the MLN and the LP. Treatment of animals with FTY720 selectively inhibited the trafficking of the CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ DC from the LP to the MLN (Fig. 4C and D). As expected, CD103 expression by CD11b− CD8+ DC is strongly correlated with RALDH expression alone in the LP or with RALDH and IL-12 expression in the MLN (Fig. 4E and F). These findings strongly suggest that CD103-expressing LP CD11b− CD8+ DC migrate to the MLN after E. cuniculi infection. Also, if DC in the LP are generally hyporesponsive, as is commonly believed, their hyporesponsiveness may explain the lack of IL-12 expression by LP CD11b− CD8+ DC and likely impairs their ability to stimulate a robust CD8+ T cell response.

FIG 4.

CD103 expression by different DC subsets. (A) CD103 expression in CD11b+ CD8− (gray lines) and CD11b− CD8+ (black lines) DC in the LP and MLN of IL-12p40 YFP mice was measured at day 2 p.i. The negative control for CD103 expression is fluorescence minus one for the CD103 marker (shaded histograms). (B) Graphs represent the frequency or total number of CD103+ cells for each subset. The MFI for CD103 is also presented. (C) CD103 expression by the CD11b− CD8+ DC population from the LP and MLN of infected mice treated with FTY720 (dashed lines) or from those of infected nontreated mice (solid lines). CD103 expression by CD11b− CD8+ DC from naïve animals (shaded histograms) is presented as a control. (D) Graphs show the frequency or total number of CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ DC in the LP and MLN. (E) At day 2 p.i., CD103 expression in different DC subsets was compared in both the LP (total CD11b− CD8+ [shaded histogram], CD11b− CD8+ Aldefluor-positive [solid line], and CD11b− CD8+ Aldefluor-negative [dashed line] DC) and the MLN (total CD11b− CD8+ [shaded histogram], CD11b− CD8+ Aldefluor-positive IL-12+ [solid line], and CD11b− CD8+ Aldefluor-negative IL-12− [dashed line] DC). (F) Graphs depict frequencies or total numbers of CD103+ cells for the same DC subsets in the MLN and LP of E. cuniculi-infected mice. Data represent results of at least 2 experiments with 3 mice/group.

Role of CD11b− CD8+ DC in eliciting an IEL response.

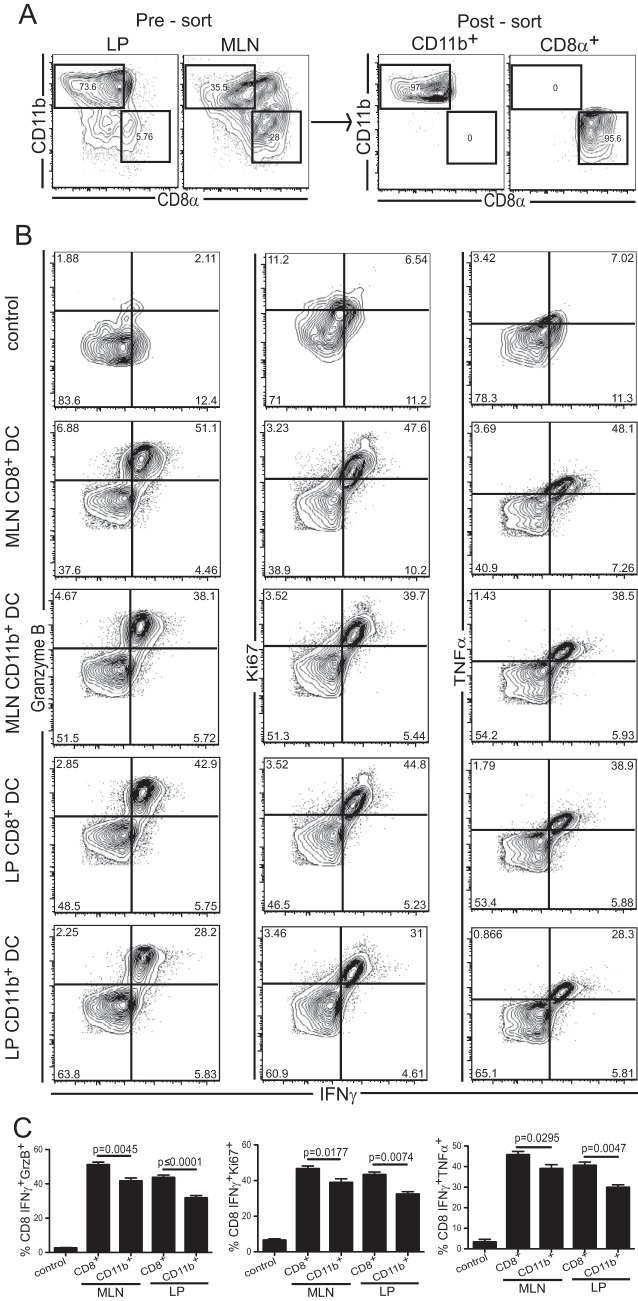

The data presented above suggest a major role for the CD11b− CD8+ DC subset in priming the T cell response during oral E. cuniculi infection. Next, experiments were performed to establish if this population was involved in triggering a mucosal T cell response against the pathogen. For this purpose, DC subsets (CD11b+ CD8− and CD11b− CD8+) from the MLN and LP were isolated from infected animals. In order to obtain a sufficient number from the LP, the cells were extracted from infected animals that received FTY720 (Fig. 5A). The purified DC subsets were cultured separately with CD8+ T cells isolated from infected IFN-γ reporter mice. Although both DC subsets were able to stimulate CD8+ T cells (as measured by upregulation of IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], and Ki67) in vitro, the CD11b− CD8+ subset from either the LP or the MLN elicited a better response than CD11b+ CD8− cells (Fig. 5B and C). In conclusion, all DC subsets from infected animals were able to present in vivo-acquired antigens to purified immune T cells.

FIG 5.

In vitro stimulation of immune CD8 T cells by mucosal DC subsets. CD11b+ CD8− or CD11b− CD8+ DC subsets were isolated at day 2 p.i. from the MLN of infected C57BL/6 mice or the LP of infected C57BL/6 mice treated with FTY720. (A) Cell suspensions from the LP and MLN before (left) and after (right) sorting are shown after gating on live CD11c+ cells. (B) Magnetically enriched CD8+ T lymphocytes from infected IFN-γ great mice were stimulated overnight with CD11b+ CD8− or CD11b− CD8+ DC from either the LP or the MLN. Dot plots showing IFN-γ, granzyme B (GrzB), TNF-α, and Ki67 expression are gated on live CD8αβ cells. The negative control corresponds to nonstimulated BMDC (no antigen) incubated with immune CD8+ T cells. (C) Graphs represent the frequencies of double-positive CD8+ T cells (IFN-γ+ GrzB+, IFN-γ+ Ki67+, and IFN-γ+ TNF-α+) for the corresponding subsets. Data represent results of at least 2 experiments with 3 mice/group.

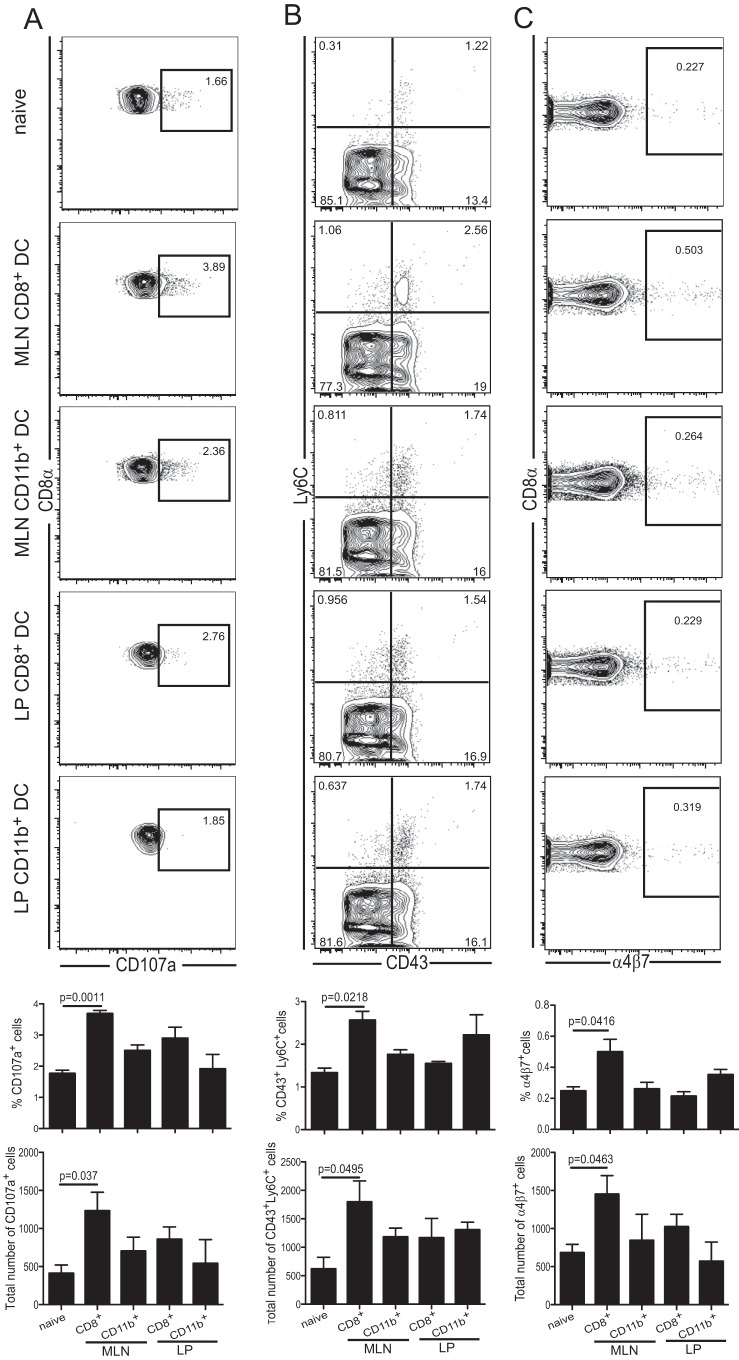

Finally, to address the abilities of the different DC populations to prime the naïve CD8 T subset, cells were isolated from infected mice as described above. Subsequently, they were adoptively transferred to naïve mice (2.5 × 104 cells/mouse), and the IEL response was evaluated at 7 days posttransfer. As shown in Fig. 6A, the frequency of the cytotoxic IEL response (based on CD107a expression) was significantly higher in the recipients that received the MLN CD11b− CD8+ DC than in those treated with any of the other subsets. The failure of LP CD11b− CD8+ DC to induce an antigen-specific IEL response could be attributed to their inability to upregulate IL-12 in the gut mucosa. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 6B, IEL from animals treated with MLN CD11b− CD8+ DC displayed a significant increase in the frequency of both IEL-specific activation markers CD43 and Ly6C (47). Similarly, the frequency of gut IEL expressing the homing receptor α4β7 (48) was also increased in these recipients (Fig. 6C). These observations demonstrate that although all the mucosal DC subsets isolated from infected animals have the ability to present E. cuniculi antigens and thereby stimulate the splenic immune CD8+ T cells in vitro, the IEL response triggered in vivo relies exclusively on the MLN CD11b− CD8+ DC. This strongly underscores their importance in the generation of mucosal immunity against this significant pathogen. Overall, our findings strongly suggest that due to their ability to secrete RA and IL-12, CD11b− CD8+ DC facilitate the development of antigen-specific mucosal CD8+ IEL immunity against E. cuniculi infection.

FIG 6.

The MLN CD11b− CD8+ DC subset isolated from infected mice elicits a significant IEL response. LP or MLN DC subsets (CD11b+ CD8− or CD11b− CD8+ DC) from mice treated as described above were sorted and adoptively transferred via tail vein injection (2.5 × 104 cells/mouse). (A) Gut IEL cytotoxic responses from recipients were assessed 7 days later via expression of CD107a. (B) Activation of the IEL was measured after transfer with CD43 and Ly6C. (C) α4β7 expression by CD8αβ IEL showing newly recruited cells. Graphs depict the frequencies or total numbers of CD8αβ IEL that are CD107a+, CD43+ Ly6C+, or α4β7+ cells. All dot plots (A to C) are gated on live CD8αβ IEL. CD8+ and CD11b+ labels on graphs correspond to CD11b− CD8+ and CD11b+ CD8− DC, respectively. Data represent results of at least 2 experiments with 3 mice/group.

DISCUSSION

Information regarding the role of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) in the initiation of the immune response against oral pathogens, although beginning to evolve, is still limited. Even though the role of IEL in protection against other orally acquired viral and parasitic infections has been demonstrated (13–16), the mechanism involved in eliciting this immune population has not been completely elucidated in an infectious model. In the current study, we identify the subset of DC responsible for triggering the mucosal response against an oral pathogen, Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Both CD11b+ CD8− and CD11b− CD8+ DC can present antigen and stimulate immune CD8+ T cells, but our in vivo studies demonstrate that only CD11b− CD8+ DC are capable of priming naïve cells. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that although LP CD11b− CD8+ DC have the ability to process retinoic acid, they are unable to produce IL-12 and, as a result, cannot elicit a CD8+ T cell response. However, once this subset migrates to the MLN, it acquires the ability to produce this cytokine, which is critical for the development of a robust CD8+ T cell response.

The role of DC in priming a T cell response is well established (19), and the subset expressing CD8α is a critical source of IL-12 during acute infection (39). But as shown in the current report, this population is very underrepresented in the LP. The importance of CD8α+ DC in the mucosal T cell response was demonstrated in Batf3-deficient mice (49), which lack both conventional CD8α+ DC and CD11b− DC in mucosal tissues and displayed a suboptimal CD8+ T cell response to pulmonary infection with Sendai virus. Moreover, Fujimoto et al. reported that LP CD8α+ DC (42) can express different Toll-like receptors (TLR) and produce IL-12 in response to ex vivo treatment with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN). These cells induced a Th1 as well as a cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response when stimulated with OVA (ovalbumin) antigen but failed to express any of the isoforms of RALDH (42). In contrast to these findings, our study, for the first time, demonstrates that CD11b− CD8+ DC from the LP express RALDH, while the same subset in the MLN produce both RALDH and IL-12, in response to an infection. Studies have shown that RA processing by DC from the gut mucosa induces the expression of the mucosal homing receptors α4β7 and CCR9 on effector T cells, allowing them to traffic back to the tissue (44–46). In the present study, MLN CD11b− CD8+ DC, which are responsible for triggering the IEL response, were the only subset to upregulate both RALDH and IL-12 in response to infection. On the other hand, LP CD11b− CD8+ DC can process RA but are unable to elicit a significant mucosal response, highlighting the critical role of IL-12 in this process. Similar to our findings, Lantier et al. demonstrated that DC from the LP produced only moderate amounts of IL-12 after Cryptosporidium parvum infection (50). The suboptimal IL-12 response by LP CD11b− CD8+ DC can be explained by the environmental conditions in the gut, which is continuously exposed to a large array of foreign antigens. To discriminate between harmless commensals, food antigens, and invasive pathogens, LP DC may need to play an anti-inflammatory role by upregulating IL-10 and type I IFN, as reported in an OVA model (51). As stated above and in support of our findings, IL-12 production by LP CD11b− CD8+ DC was not detectable in this study.

LP CD103+ DC migrate to the MLN under both steady-state and inflammatory conditions and represent a major conventional population (20). Schulz et al. have reported that intestinal CD103+ DC loaded with OVA can exhibit a classical DC function and initiate a significant immune response in the MLN (37). The importance of CD103+ DC in the mucosal immune response against an oral pathogen is further emphasized by a very recent study using a neonate model of C. parvum infection (50). In agreement with these observations, we demonstrate in this study that LP CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ DC are able to traffic to the MLN and that S1P blockade inhibits this process. Once in the MLN, CD103+ CD11b− CD8+ DC upregulate RALDH and IL-12 and initiate an IEL response against infection.

Based on our current study and earlier reports, CD11b+ CD8− CD11c+ cells represent a major population of the gut mucosa (52). Although the number of these cells was increased in response to the infection, and a fraction of them expressed CD103 and therefore represented bona fide dendritic cells, they were unable to prime an IEL response in vivo. Our findings are different from those of Cerovic et al., who showed that intestinal CD103− CD11b+ DC were able to migrate to the MLN and prime OT-I and OT-II T cells (27). The differences between our observations and those of Cerovic et al. may be attributed to the requirement for different DC subsets to prime T cell responses against a live infection versus an inert antigen. Furthermore, distinct DC subsets may be programmed for different functions depending on the nature of the stimulus.

Overall, the data presented in this article, for the first time, report that MLN CD11b− CD8+ DC express both IL-12 and RALDH, while LP CD11b− CD8+ DC express only RALDH, which could be due to their incomplete maturation. Interestingly, the lack of IL-12 production and RALDH expression does not seem to affect the abilities of the various DC subsets to stimulate immune CD8+ T cells in vitro, suggesting that both CD11b− CD8+ and CD11b+ CD8− DC from the gut have the ability to process and present antigens. Nevertheless, our findings differ from a previous report showing that both CD8+ and CD8− MLN DC support antigen-dependent generation of CCR9+ α4β7+ OT-1 T cells in vitro (44), further emphasizing the differences in the requirements for mucosal T cell priming against a live pathogen.

The data obtained in the present study are critical in that they underline a very important role for the mucosal CD11b− CD8+ DC subset in eliciting an intestinal IEL response against E. cuniculi infection. However, they raise the following questions, which require further investigation. (i) The CD11b+ CD8− cell population is increased in response to the infection but appears to play only a minimal role in the elicitation of the IEL (adaptive) immune response. The phenotypic distribution of the monocytes after E. cuniculi infection is still unknown, and the importance of sessile macrophages in parasite clearance needs to be studied, as they might be important for control of the initial infection before the initiation of adaptive immunity. (ii) The inability of CD11b− CD8+ DC from the LP to produce IL-12 needs further attention. One of the reasons could be a downregulatory environment in the gut, possibly caused by this pathogen. (iii) The nature of the stimulus triggering IL-12 production by the DC subset in the MLN needs to be evaluated. Future studies in our laboratory will attempt to address these very important issues.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants AI-096978 and AI-102711 to I.A.K.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00820-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee SC, Corradi N, Doan S, Dietrich FS, Keeling PJ, Heitman J. 2010. Evolution of the sex-related locus and genomic features shared in microsporidia and fungi. PLoS One 5:e10539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Didier ES, Weiss LM. 2006. Microsporidiosis: current status. Curr Opin Infect Dis 19:485–492. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000244055.46382.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chacin-Bonilla L, Panunzio AP, Monsalve-Castillo FM, Parra-Cepeda IE, Martinez R. 2006. Microsporidiosis in Venezuela: prevalence of intestinal microsporidiosis and its contribution to diarrhea in a group of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients from Zulia State. Am J Trop Med Hyg 74:482–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokolova OI, Demyanov AV, Bowers LC, Didier ES, Yakovlev AV, Skarlato SO, Sokolova YY. 2011. Emerging microsporidian infections in Russian HIV-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol 49:2102–2108. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02624-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viriyavejakul P, Nintasen R, Punsawad C, Chaisri U, Punpoowong B, Riganti M. 2009. High prevalence of Microsporidium infection in HIV-infected patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 40:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orenstein JM, Russo P, Didier ES, Bowers C, Bunin N, Teachey DT. 2005. Fatal pulmonary microsporidiosis due to Encephalitozoon cuniculi following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Ultrastruct Pathol 29:269–276. doi: 10.1080/01913120590951257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sıvgın S, Eser B, Kaynar L, Kurnaz F, Sıvgın H, Yazar S, Cetin M, Unal A. 2013. Encephalitozoon intestinalis: a rare cause of diarrhea in an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) recipient complicated by albendazole-related hepatotoxicity. Turk J Haematol 30:204–208. doi: 10.4274/Tjh.90692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kicia M, Wesolowska M, Jakuszko K, Kopacz Z, Sak B, Kvetonova D, Krajewska M, Kvac M. 2014. Concurrent infection of the urinary tract with Encephalitozoon cuniculi and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in a renal transplant recipient. J Clin Microbiol 52:1780–1782. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03328-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hocevar SN, Paddock CD, Spak CW, Rosenblatt R, Diaz-Luna H, Castillo I, Luna S, Friedman GC, Antony S, Stoddard RA, Tiller RV, Peterson T, Blau DM, Sriram RR, da Silva A, de Almeida M, Benedict T, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Visvesvara GS, Kuehnert MJ. 2014. Microsporidiosis acquired through solid organ transplantation: a public health investigation. Ann Intern Med 160:213–220. doi: 10.7326/M13-2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotkova M, Sak B, Kvetonova D, Kvac M. 2013. Latent microsporidiosis caused by Encephalitozoon cuniculi in immunocompetent hosts: a murine model demonstrating the ineffectiveness of the immune system and treatment with albendazole. PLoS One 8:e60941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snowden KF, Didier ES, Orenstein JM, Shadduck JA. 1998. Animal models of human microsporidial infections. Lab Anim Sci 48:589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayday A, Theodoridis E, Ramsburg E, Shires J. 2001. Intraepithelial lymphocytes: exploring the third way in immunology. Nat Immunol 2:997–1003. doi: 10.1038/ni1101-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z, Zhang C, Zhou Z, Zhang J, Tian Z. 2012. Small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes expressing CD8 and T cell receptor γδ are involved in bacterial clearance during Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect Immun 80:565–574. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05078-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culshaw RJ, Bancroft GJ, McDonald V. 1997. Gut intraepithelial lymphocytes induce immunity against Cryptosporidium infection through a mechanism involving gamma interferon production. Infect Immun 65:3074–3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buzoni-Gatel D, Lepage AC, Dimier-Poisson IH, Bout DT, Kasper LH. 1997. Adoptive transfer of gut intraepithelial lymphocytes protects against murine infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol 158:5883–5889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller S, Buhler-Jungo M, Mueller C. 2000. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes exert potent protective cytotoxic activity during an acute virus infection. J Immunol 164:1986–1994. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moretto M, Weiss LM, Khan IA. 2004. Induction of a rapid and strong antigen-specific intraepithelial lymphocyte response during oral Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection. J Immunol 172:4402–4409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moretto MM, Weiss LM, Combe CL, Khan IA. 2007. IFN-γ-producing dendritic cells are important for priming of gut intraepithelial lymphocyte response against intracellular parasitic infection. J Immunol 179:2485–2492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellman I, Steinman RM. 2001. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell 106:255–258. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Pabst O, Palmqvist C, Marquez G, Forster R, Agace WW. 2005. Functional specialization of gut CD103+ dendritic cells in the regulation of tissue-selective T cell homing. J Exp Med 202:1063–1073. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. 2007. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-β and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med 204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan H, Moretto M, Bzik DJ, Gigley J, Khan IA. 2007. NK cells enhance dendritic cell response against parasite antigens via NKG2D pathway. J Immunol 179:590–596. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefrançois L, Lycke N. 2001. Isolation of mouse small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, Peyer's patch, and lamina propria cells. Curr Protoc Immunol Chapter 3:Unit 3.19. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0319s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rossner S, Koch F, Romani N, Schuler G. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods 223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(98)00204-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montufar-Solis D, Klein JR. 2006. An improved method for isolating intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) from the murine small intestine with consistently high purity. J Immunol Methods 308:251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orenstein JM, Gaetz HP, Yachnis AT, Frankel SS, Mertens RB, Didier ES. 1997. Disseminated microsporidiosis in AIDS: are any organs spared? AIDS 11:385–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cerovic V, Houston SA, Scott CL, Aumeunier A, Yrlid U, Mowat AM, Milling SW. 2013. Intestinal CD103− dendritic cells migrate in lymph and prime effector T cells. Mucosal Immunol 6:104–113. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farache J, Koren I, Milo I, Gurevich I, Kim KW, Zigmond E, Furtado GC, Lira SA, Shakhar G. 2013. Luminal bacteria recruit CD103+ dendritic cells into the intestinal epithelium to sample bacterial antigens for presentation. Immunity 38:581–595. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courret N, Darche S, Sonigo P, Milon G, Buzoni-Gatel D, Tardieux I. 2006. CD11c- and CD11b-expressing mouse leukocytes transport single Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites to the brain. Blood 107:309–316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pron B, Boumaila C, Jaubert F, Berche P, Milon G, Geissmann F, Gaillard JL. 2001. Dendritic cells are early cellular targets of Listeria monocytogenes after intestinal delivery and are involved in bacterial spread in the host. Cell Microbiol 3:331–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. 2004. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature 427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czeloth N, Bernhardt G, Hofmann F, Genth H, Forster R. 2005. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mediates migration of mature dendritic cells. J Immunol 175:2960–2967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lan YY, De Creus A, Colvin BL, Abe M, Brinkmann V, Coates PT, Thomson AW. 2005. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist FTY720 modulates dendritic cell trafficking in vivo. Am J Transplant 5:2649–2659. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothkötter HJ, Pabst R, Bailey M. 1999. Lymphocyte migration in the intestinal mucosa: entry, transit and emigration of lymphoid cells and the influence of antigen. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 72:157–165. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(99)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shortman K, Caux C. 1997. Dendritic cell development: multiple pathways to nature's adjuvants. Stem Cells 15:409–419. doi: 10.1002/stem.150409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pabst O, Bernhardt G. 2010. The puzzle of intestinal lamina propria dendritic cells and macrophages. Eur J Immunol 40:2107–2111. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz O, Jaensson E, Persson EK, Liu X, Worbs T, Agace WW, Pabst O. 2009. Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions. J Exp Med 206:3101–3114. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trinchieri G. 1998. Interleukin-12: a cytokine at the interface of inflammation and immunity. Adv Immunol 70:83–243. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu CH, Fan YT, Dias A, Esper L, Corn RA, Bafica A, Machado FS, Aliberti J. 2006. Dendritic cells are essential for in vivo IL-12 production and development of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii infection in mice. J Immunol 177:31–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berberich C, Ramirez-Pineda JR, Hambrecht C, Alber G, Skeiky YA, Moll H. 2003. Dendritic cell (DC)-based protection against an intracellular pathogen is dependent upon DC-derived IL-12 and can be induced by molecularly defined antigens. J Immunol 170:3171–3179. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bilsborough J, George TC, Norment A, Viney JL. 2003. Mucosal CD8α+ DC, with a plasmacytoid phenotype, induce differentiation and support function of T cells with regulatory properties. Immunology 108:481–492. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujimoto K, Karuppuchamy T, Takemura N, Shimohigoshi M, Machida T, Haseda Y, Aoshi T, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Uematsu S. 2011. A new subset of CD103+ CD8α+ dendritic cells in the small intestine expresses TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 and induces Th1 response and CTL activity. J Immunol 186:6287–6295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gately MK, Wolitzky AG, Quinn PM, Chizzonite R. 1992. Regulation of human cytolytic lymphocyte responses by interleukin-12. Cell Immunol 143:127–142. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90011-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Wurbel MA, Malissen B, Marquez G, Agace W. 2003. Selective generation of gut tropic T cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT): requirement for GALT dendritic cells and adjuvant. J Exp Med 198:963–969. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mora JR, Bono MR, Manjunath N, Weninger W, Cavanagh LL, Rosemblatt M, Von Andrian UH. 2003. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer's patch dendritic cells. Nature 424:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, Song SY. 2004. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity 21:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montufar-Solis D, Garza T, Klein JR. 2007. T-cell activation in the intestinal mucosa. Immunol Rev 215:189–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lefrançois L, Parker CM, Olson S, Muller W, Wagner N, Schon MP, Puddington L. 1999. The role of β7 integrins in CD8 T cell trafficking during an antiviral immune response. J Exp Med 189:1631–1638. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edelson BT, Wumesh KC, Juang R, Kohyama M, Benoit LA, Klekotka PA, Moon C, Albring JC, Ise W, Michael DG, Bhattacharya D, Stappenbeck TS, Holtzman MJ, Sung SS, Murphy TL, Hildner K, Murphy KM. 2010. Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8α+ conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med 207:823–836. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lantier L, Lacroix-Lamande S, Potiron L, Metton C, Drouet F, Guesdon W, Gnahoui-David A, Le Vern Y, Deriaud E, Fenis A, Rabot S, Descamps A, Werts C, Laurent F. 2013. Intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells are key players in the innate immune control of Cryptosporidium parvum infection in neonatal mice. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003801. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chirdo FG, Millington OR, Beacock-Sharp H, Mowat AM. 2005. Immunomodulatory dendritic cells in intestinal lamina propria. Eur J Immunol 35:1831–1840. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Helft J, Shang L, Hashimoto D, Greter M, Liu K, Jakubzick C, Ingersoll MA, Leboeuf M, Stanley ER, Nussenzweig M, Lira SA, Randolph GJ, Merad M. 2009. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity 31:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.