Significance

It is highly informative to actively manipulate the conformations of an enzyme molecule by an external force and simultaneously observing the responses of the enzymatic activity changes. However, one of the challenges for a conventional approach is that an enzyme cannot be denatured under an enzymatic reaction condition, which prevents a simultaneous conformational manipulation and activity measurements. Using our single-molecule total internal reflection (TIRF)-magnetic tweezers microscopic approach to manipulate the conformations of enzymes and simultaneously probing the enzymatic reactivity changes under enzymatic reaction conditions, we identified that enzymatic activity can be manipulated by external pulling force and that enzyme molecules with deformed conformation are still capable of showing significant activities, involving the enzymatic active site conformational fluctuations and substrate binding-induced folding-binding conformational changes.

Keywords: enzyme, single molecule TIRF-magnetic tweezers microscopy, manipulate the conformation, enzymatic conformational dynamics, conformational fluctuation

Abstract

Characterizing the impact of fluctuating enzyme conformation on enzymatic activity is critical in understanding the structure–function relationship and enzymatic reaction dynamics. Different from studying enzyme conformations under a denaturing condition, it is highly informative to manipulate the conformation of an enzyme under an enzymatic reaction condition while monitoring the real-time enzymatic activity changes simultaneously. By perturbing conformation of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) molecules using our home-developed single-molecule total internal reflection magnetic tweezers, we successfully manipulated the enzymatic conformation and probed the enzymatic activity changes of HRP in a catalyzed H2O2–amplex red reaction. We also observed a significant tolerance of the enzyme activity to the enzyme conformational perturbation. Our results provide a further understanding of the relation between enzyme behavior and enzymatic conformational fluctuation, enzyme–substrate interactions, enzyme–substrate active complex formation, and protein folding–binding interactions.

One of the central focuses in protein study is the structure–function relationship, the impact of different conformations on the properties of protein molecules. It has been widely reported that protein molecules with their tertiary structure perturbed or even partially unfolded may be related to protein malfunction or human diseases, because changing protein conformations typically leads to significant differences in their affinity, selectivity, and reactivity (1–17). In modern enzymology, it has extensively been explored that the enzymatic conformation–dynamics–function relationship, especially the dynamic rather than the static perspectives, plays a critical role in the understanding of enzyme mechanisms at the molecular level (18–21). For example, in an enzymatic reaction, formation of the enzyme–substrate complex often involves significant enzymatic active site conformational changes (22–25).

Traditional enzymology focused on studying enzymatic reactions at conditions in which the enzymes are fully folded or in their natural states. For example, the studies of enzymatic stability focused on ensemble level activity of enzymes at different physical conditions or chemical environment without probing corresponding change in conformation of enzyme molecules under the same conditions (11, 12, 18–28). In recent years, a number of technical approaches on single-molecule protein conformational manipulation, such as atomic force microscopy (AFM), magnetic tweezers, and optical tweezers, have been developed (29–34). Furthermore, more research has focused on studying enzymatic activity under denaturing conditions, in which enzymes are denatured or are under nonphysiological enzymatic reaction conditions (8, 13, 35–38).

Nevertheless, it remains a challenge to characterize the impact of conformational changes of enzyme molecules on their activity under enzymatic conditions while simultaneously probing the enzymatic reactivity changes. Understanding such impacts provides a profound understanding of the enzymatic activity, enzyme–substrate complex formation dynamics, enzymatic product releasing dynamics, and enzymatic reaction energy landscape (14, 39). For example, it has been theoretically studied that the enzymatic activity can be manipulated by an external mechanical force through perturbing the conformation changes of the enzyme molecules (19, 39, 40).

It is significant that a single-molecule enzymatic reactivity study, under conformational perturbation and enzymatic reaction conditions, reveals the dependence of enzymatic reactivity on the conformational changes and stability of the enzyme. Key questions of how the enzymatic conformations impact the enzymatic activity and functions are still not clear. For example, can the substrate–enzyme interaction affinity be affected by perturbing enzyme conformation via mechanical force manipulation? Does a conformation-perturbed or even partially unfolded enzyme molecule still have measurable enzymatic reactivity? If so, how much activity will be left at various degrees of external force perturbation? How much can an enzyme molecule tolerate a conformational change under an enzymatic reaction condition? Here we report our work toward obtaining the answers to these questions.

In our previous single-molecule FRET magnetic tweezers study, we demonstrated that when a single protein molecule is stretched by magnetic tweezers, a significant change in the conformation, a deformed protein, can be observed (30). Furthermore, we observed that the enzyme–substrate interaction can induce the change of enzymatic active site conformation fluctuation dynamics and conformational flexibility (30).

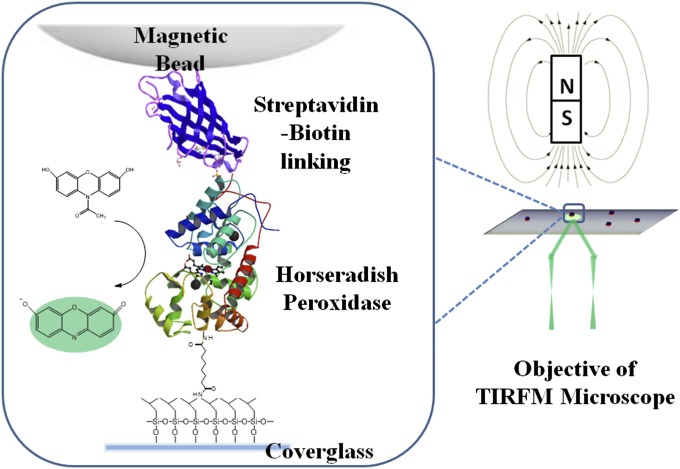

Here we report our work on manipulating single-molecule enzymatic activity using magnetic tweezers to deform the conformations of single-molecule horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzymes and simultaneously recording the single-molecule fluorogenic enzymatic turnovers by total internal reflection (TIRF) microscopic imaging (Fig. 1). There are specific advantages of using magnetic tweezers to provide an external mechanical force to manipulate single molecule enzyme, including (i) having a force range less than the hydrogen bonding force to protein rupture force (pN to nN); (ii) having no photo-damage and optical cross-talk to single-molecule spectroscopic measurements of enzymatic activity and enzyme conformational changes; and (iii) being capable of simultaneously applying force on a large number of single molecules under the same experimental conditions (41). Combined with TIRF microscopy as a spectroscopic imaging measurement, our single-molecule TIRF-magnetic tweezers provides us a unique capability and opportunity to interrogate the conformation–function relationship of enzyme molecules under enzymatic reaction conditions to specifically study the impact of deforming protein conformation on protein function at a single-molecule level.

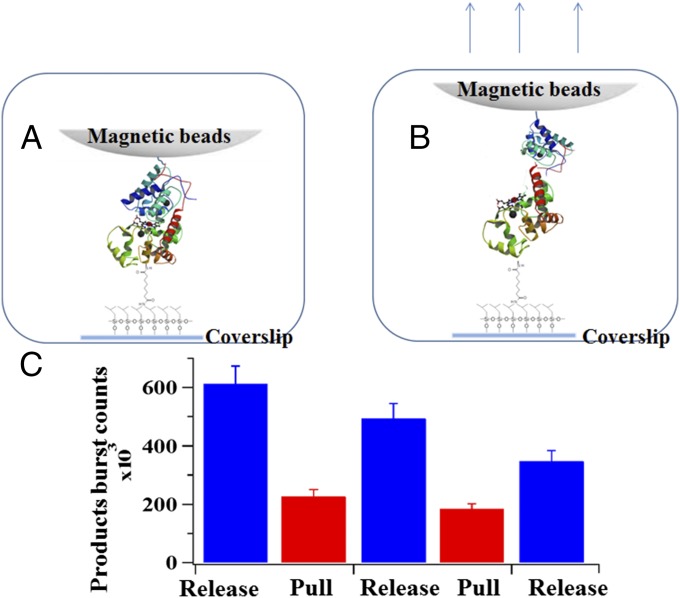

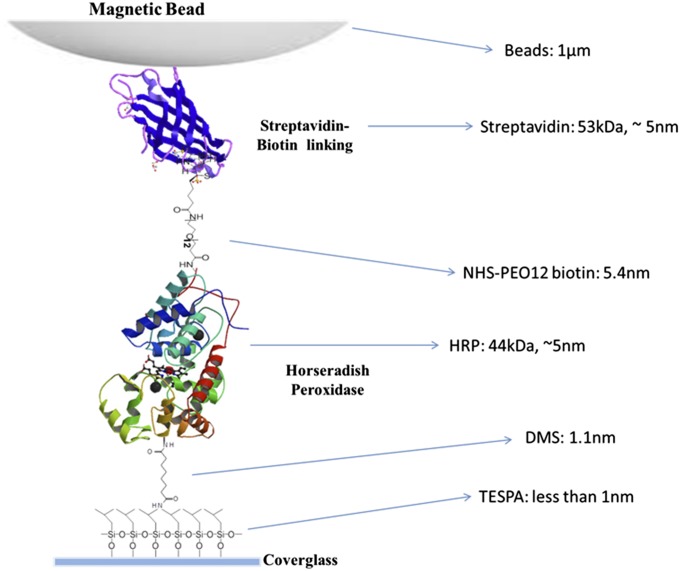

Fig. 1.

A conceptual scheme of our experimental system. HRP molecules are tethered at one end to a modified glass coverslip, and the immobilized HRP molecules are tethered at the other end to magnetic beads through biotin-streptavidin linking. The magnetic tip of 1,100-Gauss magnetic field at ∼4 mm above the sample glass surface is applied to 1-μm-diameter paramagnetic beads to generate 1- to 2-pN mechanical pulling force on the beads and to the enzyme molecules (SI Text).

Results

Single-Molecule TIRF Imaging Measurement of HRP Activity.

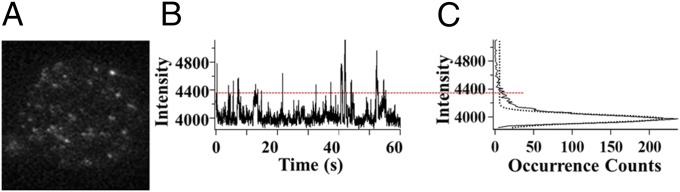

Fig. 2 A and B shows one of the recorded TIRF imaging and fluorescence intensity time trajectories of a single HRP molecule under a fluorogenic enzymatic assay condition. The time resolution of our TIRF imaging measurement is 20-ms exposure time and 10-ms data readout time for each imaging frame, whereas each measurement lasts 90 s to accumulate 3,000 image frames. We take the photon bursts that are above the threshold of the trajectory into account as the enzymatic turnover events. The threshold is set three times the SD larger than the distribution mean value of the histogram deduced from the trajectory (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Single-turnover detection of HRP enzyme catalysis. (A) One frame of the TIRF imaging of resorufin that is released as product from the HRP catalyzed reaction. (B) Exemplary fluorescence time trajectory of a single HRP molecule observed from TIRF measurement. (C) Time distribution of the TIRF trajectory. On time domain, signals above threshold are taken into account as turnover events.

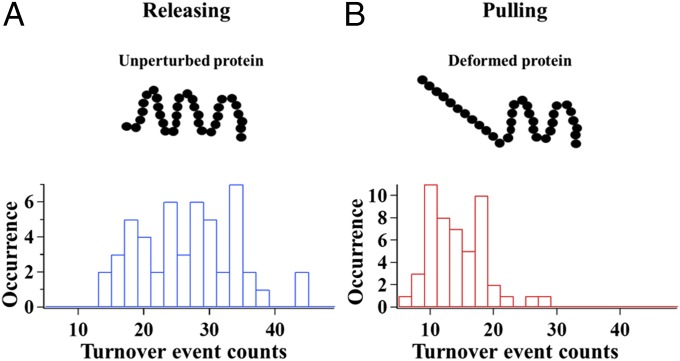

Analysis of Single-Molecule Activity Trajectories Measured Under Force Pulling and Releasing Conditions.

In our experiments, the HRP enzyme molecules were tethered to a cover glass surface at a density of 1 molecule/μm2, and in 50 mM PBS buffer solution (pH = 7.4) with Amplex red (100 nM) and H2O2 (100 nM) as substrates. We applied ∼1- to 2-pN external magnetic force for pulling, whereas there was no applied force field for releasing. Fig. 3 shows that when being pulled by external magnetic force, the number of turnover events per single-molecule trajectory recorded on the manipulated single HRP molecules decreases, indicating a decrease in catalytic activity of the HRP enzyme molecules.

Fig. 3.

Histogram results of turnover events from 50 individual HRP molecules. (A) Turnover events histogram when no force is applied on HRP molecules, the “releasing” group of HRP. (B) Turnover events histogram when the HRP molecules are pulled by applied force from magnetic tweezers, the “pulling” group of HRP.

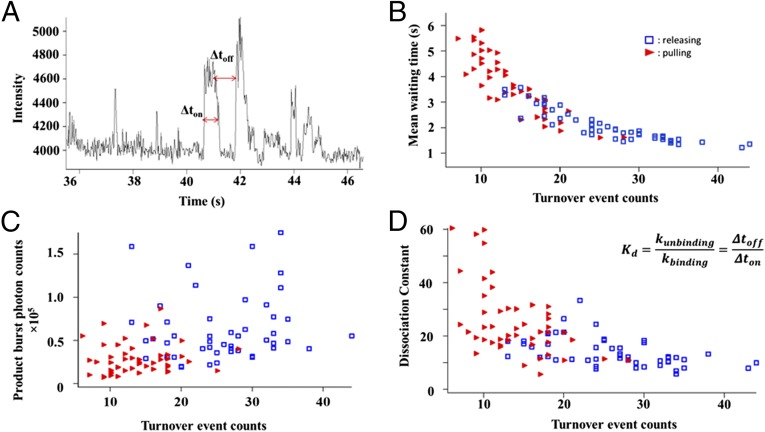

To further quantitatively characterize the impact of conformational distortions on the enzymatic activity of HRP molecules by using mechanical force manipulation, we analyzed both the distribution of the turnover waiting time and distribution of detected photon from released products based on the single-molecule fluorogenic trajectories recorded. As shown in Fig. 4A, the turnover waiting time, Δtoff, was the time interval between two consecutive detected fluorogenic turnover events, above-threshold fluorescence signal intensity bursts. The turnover waiting time, the time needed for actual events of catalytic product (resorufin) formation, is negatively proportional to the enzymatic reactivity. In an enzymatic reaction E + S → ES → EP → E + P, where E, S, and P represent enzyme, substrate, and product, respectively, the overall enzymatic turnover rate is determined by the rate of substrate diffusion and enzyme–substrate complex formation, S + E → ES, as well as the catalytic reaction ES → EP, and releasing products, EP → E + P. Although, individual waiting time values are stochastic, the mean waiting time, <Δtoff>, and its distributions are defined by enzymatic turnover rate. In our experiments, we analyze the mean waiting time <Δtoff> over the turnover trajectories from each HRP enzyme molecule. When under pulling force via magnetic tweezers, deformation of the HRP enzyme occurs, and the <Δtoff> accordingly increases due to the decrease of the single-molecule HRP enzymatic reaction rates (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of the relationship between turnover event counts, mean waiting time, and product burst of single HRP molecules. The data in red and blue are measured from the single-molecule enzyme under force pulling and releasing conditions, respectively. (A) Correlation plots between turnover event counts and mean waiting time of each single HRP molecules with and without magnetic pulling force applied. (B) Correlation plots between turnover event counts and photon burst counts from released products of each single HRP molecules with and without magnetic pulling force applied. (C) Correlation plots between turnover event counts and photon burst counts from released products of each single HRP molecules with and without magnetic pulling force applied. (D) Enzyme–substrate dissociation constant of each single HRP molecules with and without magnetic pulling force applied. The data in red and blue are from the HRP enzyme molecules under external force pulling and no force applied conditions, respectively.

Fig. 4C shows the distribution of the total photon counts from the fluorogenic product turnover events for the single-molecule HRP under both force pulling and non–force pulling conditions. The total photon counts of enzymatic turnover photon burst events are calculated by counting all of the photons above the threshold with and without magnetic pulling force for each single HRP molecule. Under the force pulling, the product burst photon counts decrease significantly, consistent with the decreased number of turnover events, presumably associated with significant enzyme conformation deformation. This result of the enzymatic reaction activity decreases with the increase of the enzyme conformation deformation by force manipulation is consistent with the results of <Δtoff> analysis (Figs. 3 and 4).

To reveal whehter the reduced activity is the result of change in substrate binding, we further studied the change in enzyme-substrate binding affinity by calculating the equilibrium dissociation constant, Kd, which is defined in Eqs. 1 and 2.

| [1] |

| [2] |

The rates of binding and dissociation of the enzyme–substrate complex are characterized by kbinding and kunbinding, respectively. Waiting-time Δtoff and on-time Δton are defined as shown in Fig. 4A. The result of the Kd calculation (Fig. 4D) shows that the stretched and deformed enzyme molecules under external pulling force have larger dissociation constant Kd, indicating a weaker ligand–substrate binding ability compared with that of the native enzyme molecules under no external force pulling. The external pulling force decreases the enzymatic ligand–substrate binding affinity by deforming the enzymatic active site conformation to be less flexible, consistent with our previously reported result (30).

Repetitive Force Pulling-Releasing Manipulation of Enzyme Conformation for Impacting Enzymatic Activity.

We also measured the response of HRP enzymatic activity to a repetitive force manipulation, toggling between pulling and releasing force applications to demonstrate the reproducibility and effectiveness of the force manipulation via magnetic tweezers-correlated single-molecule TIRF spectroscopy to the protein function (Fig. 5). In this experiment, the reaction system is first observed by TIRF microscopy without any pulling force from the magnetic field for 100 s, which is the release state; the pulling force is then applied for the next 100 s, which is the pull state; and the cycle including the release and pull processes is repeated a few times for the next 300 s. Fig. 5C shows that the total photon counts from the product turnover events of a single HRP molecule toggles between two different levels, reflecting the single-molecule enzymatic activity changes due to the conformational manipulation by the external force pulling and releasing. Such a response demonstrates the reproducible impact of the external force on the single enzyme catalytic function by affecting the substrate binding process via deforming conformation.

Fig. 5.

Response of HRP enzymatic activity to repetitive magnetic pulling force. Under the pull condition, external pulling force is applied to deform the enzyme conformation, whereas under the release condition, there is no external force being applied. Conceptual scheme of HRP molecule at released (A) and pulled (B) state, respectively. (C) Product counts from 20 different HRP molecules with and without being pulled. Errors are conservatively estimated as 10% considering the possible inaccuracies involved in the setting threshold method in our data analysis.

Steered Molecular Dynamic Simulation of the HRP Enzyme Under Conformational Manipulation.

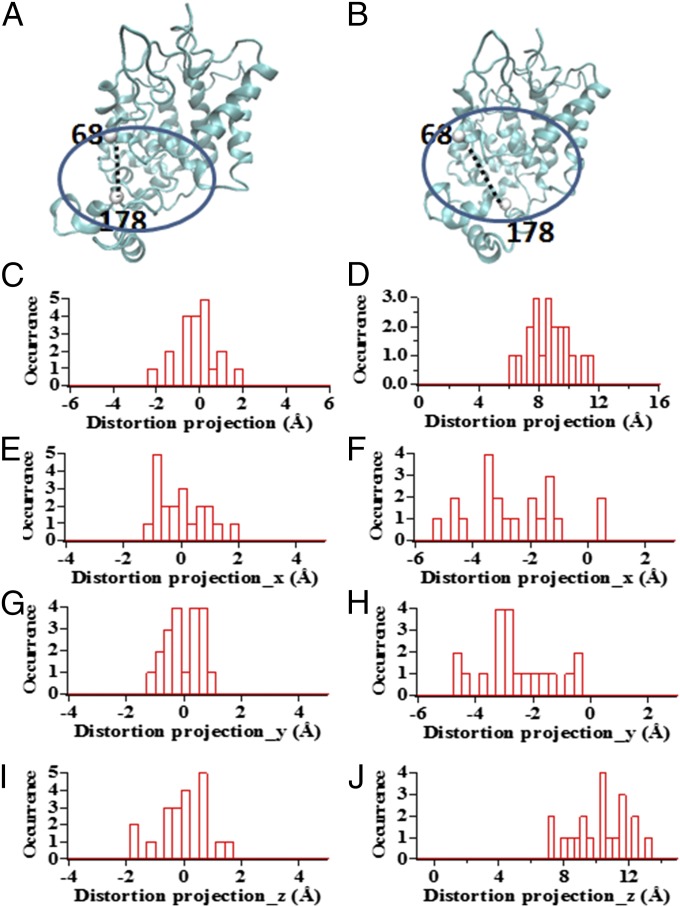

We performed a steered molecular dynamic (SMD) simulation to help our understanding of how the conformational manipulation by magnetic tweezers affects the enzymatic active site conformations on the enzyme molecule (42–45).* In our SMD simulation, we set lysine residue 65 and lysine residue 174 on the HRP protein molecule to be stretched up to 17 Å as an example to discover the corresponding active site conformational change. We used the distance between residue 68 and residue 178 to characterize the conformational deformation of the active site of the HRP protein molecule (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

SMD simulation results show the scheme of the distortion of active site when the protein is pulling by magnetic tweezers. (A) Natural HRP protein molecule. (B) HRP protein molecule being pulled by magnetic tweezers. (C) Distortion of distance between residues 68 and 178 induced by thermal fluctuation of the HRP protein molecule. (D) Distortion of distance between residues 68 and 178 induced by pulling force applied on the HRP protein molecule. (E, G, and I) Projection on Cartesian coordinate of the distance distortion between residue 68 and residue 178 for HRP protein induced by thermal fluctuation in unperturbed condition. (F, H, and J) Projection on Cartesian coordinate of distance distortion between residue 68 and residue 178 for HRP protein in stretched condition.

The initial condition of the HRP protein molecule is in its equilibrium conformation in an aqueous environment without the force pulling perturbation applied (Fig. 6A), which is the initial state, and then force is pulled to a deformed conformation, which is the final state (Fig. 6B). In 20 independent simulation events, the distance between residue 68 and residue 178 was observed to have a fluctuation within 2 Å (Fig. 6 C, E, G, and I) due to conformational thermal fluctuation of the HRP protein, whereas the corresponding projections on the spatial Cartesian coordinate are shown in Fig. 6 E, G, and I. Fig. 6B illustrates how the distance of the residue pair 68–178 gets distorted when the HRP molecule is stretched in the experiment with magnetic tweezers, indicating a deformation of the HRP active site conformation. Fig. 6D shows the statistical results from 20 simulation events: the distance extension of residue 68 and residue 178 is extended for about 8–10 Å (Fig. 6 D, F, H, and J) when the tethered lysine residue 65 and residue 174 on the protein molecule are stretched up to 17 Å. The corresponding projections on the spatial Cartesian coordinate are shown in Fig. 6 F, H, and J. Such responses from SMD simulation conceptually reveal that, in our experimental condition, when being stretched by magnetic tweezers, the active site on the HRP protein molecule is distorted to an extent significantly beyond its thermal conformational fluctuation.

We also note here that the HRP protein in the experiment is linking to the coverslip and magnetic bead via a connection with the -NH2 group on the lysine residue. Therefore, there are multiple possible tethering conditions of the protein molecule to the coverslip or magnetic beads, leading to multiple possible stretching types for different HRP protein molecules. The active site distortion response shown in Fig. 6 is from one possible pattern to stretch HRP molecules. We simulated the stretching experiments for all of the possible pulling configurations for HRP protein molecules to reveal that the conformational distortion beyond the thermal fluctuation range of the active site occurs for most stretching types for the HRP molecule, as shown in SI Text.

Discussion

In our previous work, we specifically analyzed an enzyme conformational change under the same experimental configuration and same magnetic field strength, we reported that the 1- to 2-pN external pulling force can result in an enzyme unfolding or deformation by 30–100%, and the enzyme–substrate binding interaction can be significantly weakened, although not completely diminished (30). We note that, although the applied pulling force on the enzyme protein molecules are weaker than the hydrogen bonding force of 6–9 pN, the directional and constant forces are capable of deforming the enzyme conformations under the thermal fluctuating local environment. Figs. 4 and 5 show that when such external pulling force is applied to deform an enzyme molecule, its enzymatic fluorogenic product turnover event counts have a significant decrease, indicating the decreasing catalytic activity of the HRP enzyme molecule that is deformed or partially unfolded by the external pulling force. The SMD simulation also shows a supporting result, illustrating the deformation of the HRP active site of conformation under force pulling. In the literature, there are studies on enzyme folding and unfolding under the overall denature solutions, where the enzymes present either in the denatured condition with unfolded conformation or in the enzymatic reaction condition with fully folded conformation (46–49). It is a challenge to study how the enzymatic conformation affects the enzymatic activity in the enzymatic physiological condition. In our experiment, we achieved actively manipulating single enzyme molecules to the deformed conformation under a physiological enzymatic reaction condition. To the best of our knowledge, our results present, for the first time, active perturbations of single-molecule enzyme reactivity function by conformational manipulation applying and controlling pulling force on single HRP molecules under physiological enzymatic reaction conditions with the existence of substrates.

Revealing Significant Tolerance of Enzymatic Activity to Protein Conformational Deformations.

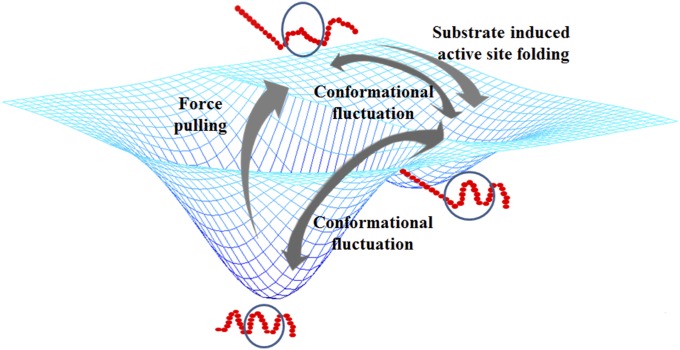

It is also interesting that the HRP enzyme molecules are not totally deprived of their catalytic activity when their conformations are stretched by an external force, although this is less active than that of the enzyme molecules under their unperturbed natural conformations (Figs. 4 and 5). The SMD simulation results also show a noticeable deformation of the active site in a HRP molecule when the molecule is pulled by magnetic tweezers, yet the chemical process in the enzymatic reaction function of electron transfer and proton transfer requires precision of angstroms in the molecular structure and configuration (50). The critical factor is the conformational fluctuation of the enzymatic active site. When being deformed by an external constant pulling force, the enzyme molecules are still capable of temporarily coming back through conformational fluctuation to its substrate-binding accessible conformational subset states, although with a lower possibility compared with enzymes without a pulling force applied. For enzyme molecules in enzymatic reaction conditions, such fluctuating comebacks of the enzymatic active site states are most likely further facilitated by enzyme–substrate interactions. In enzymatic reactions, the enzyme–substrate interaction plays a key role by regulating the enzymatic active site conformation and inducing the active site conformational fluctuation toward folded into active-favored subsets from folding–unfolding conformational fluctuation of enzyme molecules. The enzyme–substrate complex formation can regulate both static and dynamic conformations of the enzyme. In other words, the substrate-binding process induces the partially unfolded or deformed enzyme active site conformation to be refolded to the active and nature conformation to produce the enzymatic reaction turnovers. A conceptual picture of this explanation is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Conceptual scheme of conformational fluctuation of single enzyme protein when being deformed by external force. The circled part conceptually represents the active site on a single enzyme molecule. When the conformation of an enzyme molecule is deformed by external force, substrate binding-induced conformational changes allow the enzymatic active site to come back to its active conformation, leading to occurrence of reaction events.

Such an understanding of the chronic conformational fluctuation of protein molecules is also in accordance with recent research of intrinsically disordered proteins or intrinsically unstructured proteins. An intrinsically disordered protein typically does not fold in a well-defined 3D structure under near-physiological conditions (51). Such phenomena have been the focus of extensive studies in recent years (52–55). Significantly different conformations can be detected for the same type of protein molecules in solution (55). Although being observed as lacking stable tertiary and/or secondary structure, intrinsically disordered proteins are capable to maintain specific functions. Our results here provide a possible mechanism for the existence of the intrinsically disordered protein by revealing conformational fluctuation of enzyme protein molecules and identifying that such conformational fluctuation can be regulated by the ligand-binding process. By substrate-induced enzyme–substrate interaction, deformed enzyme molecules can fluctuate from the unstructured back to the structured state and can still be capable of maintaining their function. Similarly, it is possible for intrinsically disordered protein molecules to fluctuate among different conformations to keep or stop certain functions.

Conclusion

In this work, we demonstrated that, using the single-molecule TIRF-magnetic tweezers correlated imaging spectroscopy, the conformational perturbations from a pulling force can manipulate enzyme function: structural deformation of enzyme molecules leads to corresponding changes in their activity. Such an influence reveals that the enzyme has a remarkable countenance and tolerance toward conformational distortion, i.e., the enzyme can still possess significant activity even if the enzyme conformation is deformed. Our experimental approach provides a unique capability: actively manipulating an enzyme to a partially unfolded conformation under a physiological enzymatic reaction condition. In this work, we were able to interrogate the enzymatic reactivity in the context of the protein structure–function relationship in a unique experiment, and this repetitive manipulation of enzymatic activity reveals the capability of manipulating biological and chemical functions by applying mechanical force perturbation on the enzyme molecules.

Methods

Materials.

HRP is a 34-kDa 306-residue monomeric enzyme. The HRP-catalyzed reaction converts hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and nonfluorescent N-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine (APR) into fluorescent resorufin. The released product molecules emit fluorescence that is detectable by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. In our experiment, superparamagnetic beads (Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1; Invitrogen; 1.05 µm in diameter) were covalently linked to the HRP molecules through a biotin-streptavidin link. The HRP enzyme molecules were in a 50 mM PBS buffer solution (pH = 7.4), containing 100 nM APR (Amplex Red) and 100 nM H2O2.

TIRF Measurement.

TIRF measurements were carried out using an inverted microscope (Olympus IX 71 with a 60× objective) with a 532-nm CW laser (Crystalaser) generating evanescent waves for total internal excitation. The emitted signal was filtered with a long-pass filter and collected with an Electron Multiplying Charge Coupled Device (EMCCD: ProEM 512B, PI co.). We conducted the single-molecule TIRF optical measurements and pulling manipulation via magnetic tweezers simultaneously. Magnetic force was applied through superparamagnetic beads attached to HRP molecules. The essential component of our magnetic tweezers device is a permanent magnet that was settled on a specially made stage, making the magnet probe capable of moving in any direction and distance. The sample chamber was put on an x-y stage capable of applying an in-plane adjustment. The distance between the magnet and the sample cover glass is 4 mm, implying an 1,100-Gauss magnetic field to the sample.

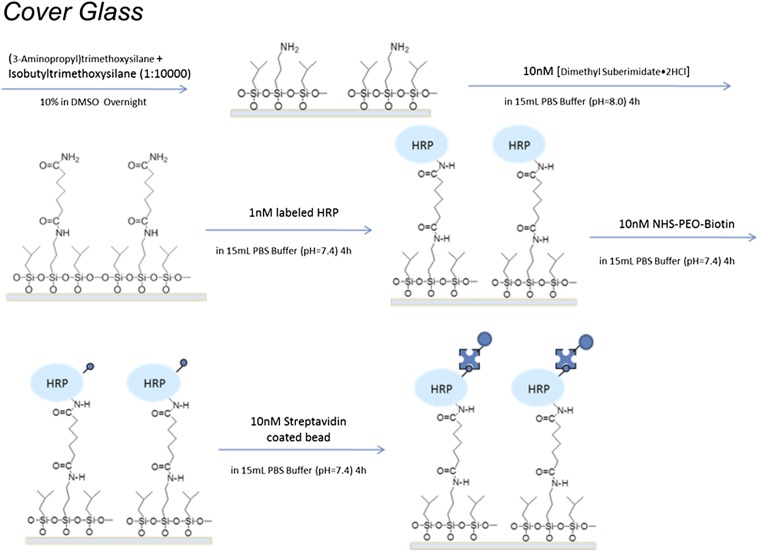

Sample Preparation.

As shown in Fig. 1, the HRP molecules were bound to the glass coverslip at one end by 3-aminopropyltriethoxy-silane (TESPA)–dimethyl suberimidate⋅2 HCl (DMS) linkers and linked to a streptavidin-coated superparamagnetic bead (Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1; Invitrogen) at the other end via a biotin–streptavidin bond.† Protein immobilization was carried out as below (for details, see SI Text). First, a clean glass coverslip was immersed overnight in an NaOH-ethanol solution, and the coverslip was next washed by distilled water, blow-dried by airflow, and incubated with a DMSO solution containing a 10% (vol/vol) concentration mixture consisting of TESPA and isobutyltrimethoxysilane in a 1:10,000 ratio overnight. The coverslip was then washed by distilled water and consecutively transferred and incubated for 4 h in each system below: 15 mL PBS buffer solution, pH = 8.0, containing 10 nM DMS⋅2 HCl; 15 mL PBS buffer solution, pH = 7.4, containing 10 nM HRP; 15 mL PBS buffer solution, pH = 7.4, containing 10 nM NHS-PEO12-biotin; 15 mL PBS solution, pH = 7.4, containing 1-µL magnetic beads stock solution, which is commercially available. The low concentration of each solution was to make sure that the distribution of the individual enzyme molecules on the cover glass was adequately separated so that one bead does not attach to multiple enzyme molecules. Meanwhile, low concentrations of TESPA were used to ensure that immobilized protein molecules are distributed from each other to obtain single-molecule TIRF images.

Molecular Dynamic Simulation.

In the SMD simulation, we did constant speed pulling simulations to illustrate the conformational distortion of the HRP protein molecule responding to an external stretching force. There are two reasons for this choice: (i) the force we apply in the experiment is at such a fine scale that the calculation time would be too long for constant force simulation, and (ii) in our previous paper, we demonstrated the capability of using magnetic tweezers to stretch the conformation of a single protein molecule. Here, the HRP protein molecules are stretched in the same pulling condition by the same single-molecule fluorescence magnetic tweezers microscopic approach. The goal of this simulation was to characterize the distortion scale of the active site of a HRP protein once the HRP protein molecules are in the same stretching condition via our magnetic tweezers compared with the results from our previous published work (30). The initial coordinate of the HRP protein molecule is taken from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID code 1W4Y). The MD simulation is performed using the program NAMD, version 2.9. The protein molecule is set in a water solvation condition under a Chemistry at Harvard Molecular Mechanics (CHARMM) force field. A boundary condition was applied for a time step of 1 fs. Considering the computation time, we set the pulling speed at 0.5 Å/ps (42–44). A constant temperature of 293 K during the simulation was maintained by a Langevin thermostat, with the Langevin damping coefficient set at 1 ps−1. Constant pressure was maintained at 1 atm using a Langevin piston. The nonbond interaction was calculated using particle mesh Ewald (PME) full electrostatics; the cutoff of the van der Waals energy was set at 12.0 Å, with a switch distance at 10.0 Å and pair-list distance set at 13.5 Å. The PME grid spacing was set at 1.0 Å.

SI Text

Chemistry Details in Sample Preparation.

Chemicals.

HRP was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company (P8375), and the EZ-Link NHS-PEG12-Biotin (or named as EZ-Link NHS-PEO12-Biotin) was purchased from Thermal Scientific Company. The -NHS end of the linker is reactive with the -NH2 group of lysine residues on the HRP enzyme surface and linked to the HRP enzyme; the other end, biotin, can bind with streptavidin that is coated on the paramagnetic beads. The magnetic beads, coated with streptavidin on the surface (Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1), were purchased from Invitrogen. All of the other chemicals are bought from Sigma-Aldrich.

Procedure of sample preparation.

We tethered one end of the HRP enzyme molecules onto the coverslip surface with low-density distributed -NH2 group with dimethyl suberimidate-2HCl (DMS-2HCl), and the other end of the HRP enzyme molecule to a 1-µm size paramagnetic bead coated with biotin-streptavidin with the NHS-PEG12-Biotin linker. Details of the procedure are shown in Fig. S1.

Fig. S1.

Procedure for sample preparation.

The structure of the single-molecule sample.

A conceptual scheme (Fig. S2) shows the detail of a single immobilized HRP enzyme molecule with a tethered magnetic bead, which is the sample used in our experiments. The distance between the magnetic bead and the coverslip was ∼20 nm; in contrast, the diameter of the magnetic bead was 1 µm. As a result, the Brownian motion of the magnetic bead was highly confined within a scale of 20 nm.

Fig. S2.

A scheme of the single molecule sample: immobilized HRP enzyme molecule with tethered magnetic bead.

We note that both NHS-PEG12-biotin and DMS can only be linked to a HRP molecule via connection with the -NH2 group in the residue lysine on the surface of an enzyme molecule, and there are six lysine residues in an HRP molecule: residues 65, 84, 149, 174, 232, and 241. Therefore, in our sample preparation process, each HRP molecule can be linked to any two of the six lysine residues. There are 15 possible lysine combinations in total, leading to 15 possible tethering conditions. We performed SMD simulation for all 15 possible tethering conditions, showing that the active site of HRP molecule can be deformed beyond the scale of its normal fluctuation in most of the possible conditions as a 1- to 2-pN external force is applied to the magnetic beads. The details of the SMD simulation is discussed below.

Estimating Conformational Deformation of HPPK by MD Simulation.

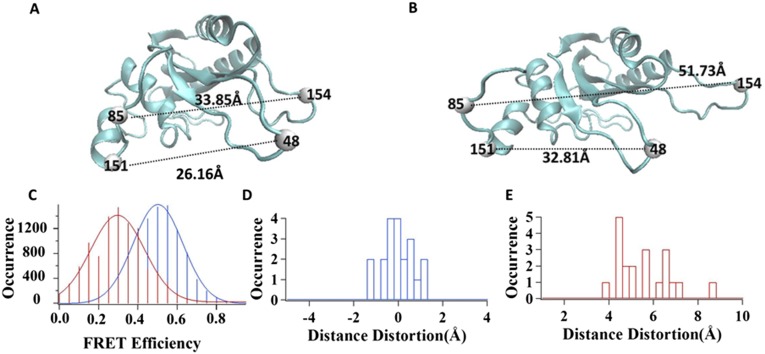

We evaluated how an HRP molecule is deformed under an external force pulling in our experiment, based on our previous experimental results from correlated magnetic tweezers-FRET measurements, where we applied the same external force of 1–2 pN as in this HRP. In our previous magnetic tweezers-FRET experiments, the FRET dye molecules Cy3 and Cy5 were labeled on residue 48 and residue 151 of the HPPK protein molecule, respectively, as shown in Fig. S3 A and B (30). We applied the external pulling force to manipulate the single HPPK molecule conformation by magnetic tweezers. Simultaneously, we used FRET spectroscopy to monitor the correlated change in conformation. As shown in Fig. S3C, the mean value of FRET efficiency shifted from 0.5 to 0.3 when a 1- to 2-pN external pulling force was applied to the single Cy3-Cy5–labeled HPPK molecules, indicating that the single HPPK molecules are stretched out in conformation, leading to an extension of about 4–6 Å between the Cy3 and Cy5 residue positions (30). To find out how much the HPPK protein molecule is stretched by magnetic tweezers, we performed an SMD simulation of the HPPK protein molecule. The initial coordinate of HPPK is obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB ID code 1HKA), set in an aqueous environment during simulation, with periodic boundary conditions set for a rectangular-shaped water box with 67.9 Å in length, 54.7 Å in width, and 67.3 Å in height. Force field file, temperature, pressure, and PME parameters are all set the same as the simulation procedure for the HRP molecule.

Fig. S3.

SMD simulation of HPPK molecule pulling by magnetic tweezers. The magnetic tweezers pulling experiment is described in our previous publication (1). (A) Structure of a WT HPPK protein molecule (PDB ID code 1HKA). (B) HPPK protein molecule being pulled by magnetic tweezers. (C) FRET efficiency distributions of single HPPK molecules under pulling (red) and releasing (blue) manipulation. (D) Distortion of distance between residues 48 and 151 induced by thermal fluctuation of HPPK protein molecule. (E) Distortion of distance between residues 48 and 151 induced by pulling force applied on HPPK protein molecule.

Fig. S3D shows that for a single HPPK molecule in an aqueous environment without an external force applied to it, the distance between residues 48 and 151 shows a thermal fluctuation within 2 Å. Fig. S3E shows that the distance is stretched about 4–6 Å under a 1- to 2-pN external pulling force, applied based on our previous FRET measurement (30).

There are five lysine residues in an HPPK protein molecule as possible tethering positions: residues 23, 85, 119, 154, and 157. Thus, in the magnetic tweezers pulling experiment, the HPPK molecule was stretched through two of these five lysine residues. For residue pair 85–154, it is necessary to be stretched to about 17 Å to make the distance between Cy3-Cy5–labeled residues 48–151 extend to 4–Å, whereas stretching through any other possible lysine residue pair on the HPPK molecule requires significantly larger distortion to achieve a similar result. In other words, the HPPK protein is stretched no less than 17 Å when the FRET shift from 0.5 to 0.3 is observed. Therefore, in the HRP simulation, we also assumed that our HRP molecule was stretched up to ∼17 Å when being pulled by magnetic tweezers.

SMD Study on All Possible Stretching Types of the HRP Protein Molecule.

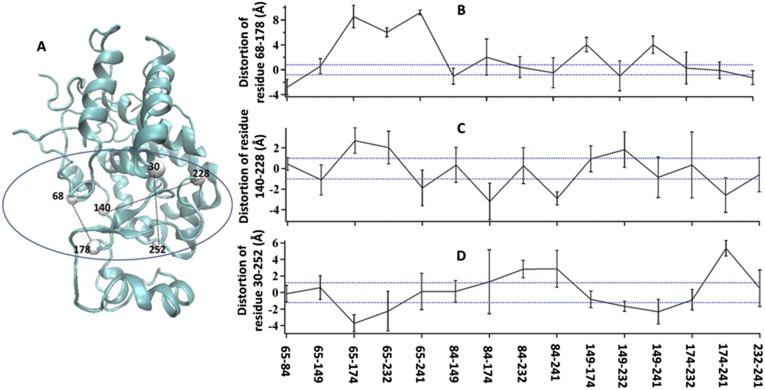

There are six lysine residues in the HRP amino acid sequence. As discussed above, an HRP molecule can only be linked to modified glass or tethered to magnetic beads through lysine residues. In our experiments, the HRP protein can only be stretched through the direction formed by two of these lysine residues. There are 15 possible lysine pair combinations, leading to 15 different possible stretching configurations for HRP protein molecules. We studied all 15 possible stretching configurations by SMD simulation (Fig. S4). We set three residue pairs to illustrate the conformational deformation on the enzymatic active site of HRP molecules: residue pair 68–178, residue pair 140–228, and residue pair 30–252 (Fig. S4A). The SMD environment parameters are all of the same as described in Materials and Methods. From the simulation results shown in Fig. S4 B–D, we find that when an HRP molecule is stretched by magnetic tweezers, its active site domain has a deformation significantly greater than the amplitudes of the thermal conformational fluctuation.

Fig. S4.

Three residue pairs to illustrate deformation on the active domain when an HRP molecule is stretched by magnetic tweezers. All of the black dashed line are thermal fluctuation range of selected residue pairs, obtained from statistical result from 20 simulation events of HRP protein in aqueous equilibrium condition. Blue dashed lines are doubled range of black ones, set as stricter threshold. (A) Scheme of the three selected residue pairs. (B) Distortion of distance between residue 68 and residue 178 in all 15 possible stretching conditions for HRP molecule. (C) Distortion of distance between residue 140 and residue 228 in all 15 possible stretching conditions for HRP molecule. (D) Distortion of distance between residue 30 and residue 252 in all 15 possible stretching conditions for HRP molecule.

HRP Conformational Deformation.

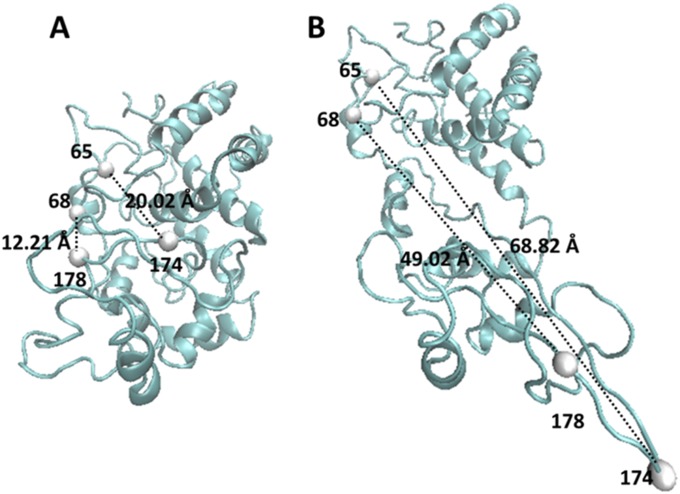

We simulated the deformation of the active site conformation to quantitatively compare different impact on the active domain between the conformational deformation in our experiment and the unfolding condition of the HRP protein molecule. We selected three residue pairs to characterize the active site conformational changes of HRP protein: residue pairs 68–178, 140–228, and 30–252, all of which are located in the active site. As shown in Fig. S5 A and B, the scale of the active site deformations is significantly larger in the scale of a complete protein unfolding compared with the deformation in our magnetic tweezers experiment (30).

Fig. S5.

Active site conformational distortion in larger unfolding situation. (A) Equilibrium conformation of HRP protein in aqueous solution. (B) Conformation of HRP protein when its lysine residues 65 and 174 are stretched for 48.8 Å: as a result, the distance between residues 68 and 178 is extended to 38 Å, the distance between residues 140 and 228 is extended to14 Å, and the distance between residues 30 and 252 is decreased for 1 Å.

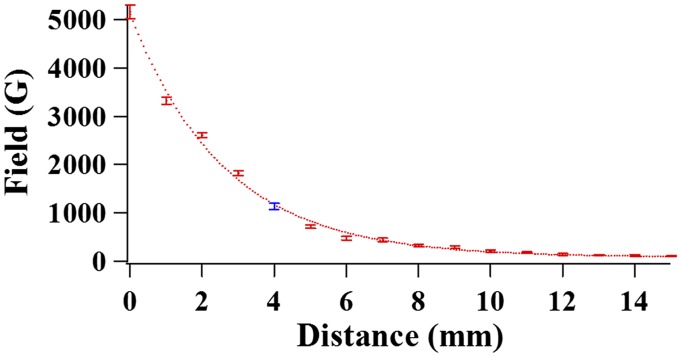

Calculation of the Force Applied by the Magnetic Tweezers.

There are a number of specific approaches to estimate the mechanical forces being applied through a magnetic field on a paramagnetic bead, such as (i) measuring and model analyzing the Brownian motions of a tethered paramagnetic bead; (ii) monitoring the dragging motion of a small number of magnetic beads in a liquid environment with known viscosity; and (iii) observing the displacement of a micropipette with a magnetic bead attached at its end (33).* Nevertheless, each of the approaches bears a specific merit of estimation with certain error bars. In our experiments, because the Brownian motions of the magnetic beads are highly confined due to the short molecular linking groups to the paramagnetic beads, we calculated the mechanical force on a single protein molecules through a tethered paramagnetic bead applied by the magnetic field based on a model analysis using the measured magnetic field strength curve as a function of the distance between the magnetic tip and the sample surface, as shown in Fig. S6. Our calculation shows that a pulling force roughly at 1–2 pN can be applied on the targeted single HRP protein molecules using our magnetic tweezers setup. Although the force is weaker than hydrogen bonding force, which is typically 6–9 pN, we demonstrated that force at this scale is sufficient to trigger conformational changes and response (30).

Fig. S6.

Magnetic field–distance curve of the magnet used in the experiment. The blue data point indicates the position of the magnet in our experiments: the magnet is set 4 mm above the sample plane to generate a magnetic field of ∼1,100 Gauss.

We calibrate the applied force by estimating the magnetic field gradient to get the magnetic moment of the beads tethered on the single protein molecule. For a magnetic bead in an externally produced magnetic field B, noting its magnetic moment as m, then the potential energy U is

| [S1] |

For a given magnetic bead, its magnetic moment m is the product of the volume magnetization M and volume V of the bead. Therefore, the force F that is applied on the magnetic bead can be calculated as

| [S2] |

In our experiments, the magnetic field applied is ∼1,100 Gauss. As an approximation, we only consider the magnetic field gradient in one direction perpendicular to the sample plane. Thus, the field gradient can be estimated from the curve shown in Fig. S6. In this way, the value of the field gradient is calculated to be 55 ± 15 T/m. When calculating the field gradient, position error up to 1 mm is taken into consideration as uncertainty of the distance between the magnet and the sample plane. The volume V of the paramagnetic bead is 0.6 × 10−18 m3, and the volume of magnetization M is 43 × 103 A/m.‡ In our calculation, we considered here that the factor M is the saturation magnetization, an approximation that may bring error less than 25%. Hence, the force is calculated as 1.4 ± 0.4 pN from Eq. S2. The typical force applied to the targeted single-molecule HPPK proteins is roughly 1–2 pN, which is weaker than a typical hydrogen bonding force of 6–9 pN.

Acknowledgments

We thank Massimo Olivucci for stimulating discussions on steered molecular dynamic simulation. This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medicine Science and the Ohio Eminent Scholar Endowment. Our MD simulation was carried out by using the computational facility of the Ohio Supercomputer Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*NAMD was developed by the Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group in the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

†We note that on a given HRP molecule, biotin or DMS is able to covalently link to lysine residue in the amino acid sequence, resulting in protein immobilization complexity that a few different tethering conditions are possible for HRP protein molecules when linking to coverslip or magnetic beads (details in SI Text). However, in our single-molecule TIRF measurement, we compare activity change of each HRP molecules individually under different conditions that with and without magnetic pulling force applied. Thus, although we did not pinpoint one specific lysine residue pair on protein molecules for tethering, our observation of different enzymatic activity associated with various enzyme conformational manipulation conditions are systematic and well defined.

‡Note: The value is according to the product specification from Invitrogen.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1506405112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Anand U, Mukherjee S. Reversibility in protein folding: Effect of β-cyclodextrin on bovine serum albumin unfolded by sodium dodecyl sulphate. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2013;15(23):9375–9383. doi: 10.1039/c3cp50207d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao JS. Event-averaged measurements of single-molecule kinetics. Chem Phys Lett. 2000;327(1-2):38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu X, Gan L, Wang E, Wang J. Quantifying the topography of the intrinsic energy landscape of flexible biomolecular recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(26):E2342–E2351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220699110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson RM, Cubitt AB, Tsien RY, Moerner WE. On/off blinking and switching behaviour of single molecules of green fluorescent protein. Nature. 1997;388(6640):355–358. doi: 10.1038/41048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.English BP, et al. Ever-fluctuating single enzyme molecules: Michaelis-Menten equation revisited. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(2):87–94. doi: 10.1038/nchembio759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Viloca M, Gao J, Karplus M, Truhlar DG. How enzymes work: Analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science. 2004;303(5655):186–195. doi: 10.1126/science.1088172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guha S, et al. Slow solvation dynamics at the active site of an enzyme: Implications for catalysis. Biochemistry. 2005;44(25):8940–8947. doi: 10.1021/bi0473915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gumpp H, et al. Triggering enzymatic activity with force. Nano Lett. 2009;9(9):3290–3295. doi: 10.1021/nl9015705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammes GG. Multiple conformational changes in enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry. 2002;41(26):8221–8228. doi: 10.1021/bi0260839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipman EA, Schuler B, Bakajin O, Eaton WA. Single-molecule measurement of protein folding kinetics. Science. 2003;301(5637):1233–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1085399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu HP, Xun L, Xie XS. Single-molecule enzymatic dynamics. Science. 1998;282(5395):1877–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margolin G, Barkai E. Single-molecule chemical reactions: Reexamination of the Kramers approach. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2005;72(2 Pt 2):025101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.025101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pisliakov AV, Cao J, Kamerlin SCL, Warshel A. Enzyme millisecond conformational dynamics do not catalyze the chemical step. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(41):17359–17364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909150106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puchner EM, Gaub HE. Single-molecule mechanoenzymatics. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:497–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stirnemann G, Kang SG, Zhou R, Berne BJ. How force unfolding differs from chemical denaturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(9):3413–3418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400752111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang SL, Cao JS. Direct measurements of memory effects in single-molecule kinetics. J Chem Phys. 2002;117(24):10996–11009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha T, et al. Single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy of enzyme conformational dynamics and cleavage mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(3):893–898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lomholt MA, Urbakh M, Metzler R, Klafter J. Manipulating single enzymes by an external harmonic force. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98(16):168302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.168302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu HP. Probing single-molecule protein conformational dynamics. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38(7):557–565. doi: 10.1021/ar0401451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svoboda K, Mitra PP, Block SM. Fluctuation analysis of motor protein movement and single enzyme kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(25):11782–11786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barkai E, Brown FLH, Orrit M, Yang H, editors. Theory and Evaluation of Single-Molecule Signals. World Scientific Publishing; Toh Tuck, Singapore: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gräslund A, Rigler R, Widengren J, editors. Single Molecule Spectroscopy in Chemistry, Physics and Biology (Nobel Symposium), Springer Series in Chemical Physics. Springer–Verlag; Berlin: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu HP. Revealing time bunching effect in single-molecule enzyme conformational dynamics. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13(15):6734–6749. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02860f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu HP. Sizing up single-molecule enzymatic conformational dynamics. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43(4):1118–1143. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60191a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fersht A. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science: A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding. 1st Ed W. H. Freeman; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorris HH, Walt DR. Mechanistic aspects of horseradish peroxidase elucidated through single-molecule studies. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(17):6277–6282. doi: 10.1021/ja9008858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassler K, et al. Dynamic disorder in horseradish peroxidase observed with total internal reflection fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Opt Express. 2007;15(9):5366–5375. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.005366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez JM, Li H. Force-clamp spectroscopy monitors the folding trajectory of a single protein. Science. 2004;303(5664):1674–1678. doi: 10.1126/science.1092497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo Q, He Y, Lu HP. Manipulating and probing enzymatic conformational fluctuations and enzyme-substrate interactions by single-molecule FRET-magnetic tweezers microscopy. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16(26):13052–13058. doi: 10.1039/c4cp01454e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu R, Garcia-Manyes S, Sarkar A, Badilla CL, Fernández JM. Mechanical characterization of protein L in the low-force regime by electromagnetic tweezers/evanescent nanometry. Biophys J. 2009;96(9):3810–3821. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nevo R, et al. A molecular switch between alternative conformational states in the complex of Ran and importin beta1. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10(7):553–557. doi: 10.1038/nsb940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SB, Finzi L, Bustamante C. Direct mechanical measurements of the elasticity of single DNA molecules by using magnetic beads. Science. 1992;258(5085):1122–1126. doi: 10.1126/science.1439819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stigler J, Rief M. Calcium-dependent folding of single calmodulin molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(44):17814–17819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201801109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.del Rio A, et al. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science. 2009;323(5914):638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1162912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanson JA, et al. Illuminating the mechanistic roles of enzyme conformational dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(46):18055–18060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou HX, Wlodek ST, McCammon JA. Conformation gating as a mechanism for enzyme specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(16):9280–9283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prakash MK, Marcus RA. An interpretation of fluctuations in enzyme catalysis rate, spectral diffusion, and radiative component of lifetimes in terms of electric field fluctuations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(41):15982–15987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707859104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bier M, Astumian RD. Matching a diffusive and a kinetic approach for escape over a fluctuating barrier. Phys Rev Lett. 1993;71(10):1649–1652. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strick TR, Allemand JF, Bensimon D, Bensimon A, Croquette V. The elasticity of a single supercoiled DNA molecule. Science. 1996;271(5257):1835–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu H, Isralewitz B, Krammer A, Vogel V, Schulten K. Unfolding of titin immunoglobulin domains by steered molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys J. 1998;75(2):662–671. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77556-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao M, Wilmanns M, Schulten K. Steered molecular dynamics studies of titin I1 domain unfolding. Biophys J. 2002;83(6):3435–3445. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75343-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gräter F, Shen J, Jiang H, Gautel M, Grubmüller H. Mechanically induced titin kinase activation studied by force-probe molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J. 2005;88(2):790–804. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips JC, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16):1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siuti P, Retterer ST, Choi CK, Doktycz MJ. Enzyme reactions in nanoporous, picoliter volume containers. Anal Chem. 2012;84(2):1092–1097. doi: 10.1021/ac202726n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan CJ, Venkataraman S, Retterer ST, Allison DP, Doktycz MJ. Comparison of the indentation and elasticity of E. coli and its spheroplasts by AFM. Ultramicroscopy. 2007;107(10-11):934–942. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanase M, Biais N, Sheetz MP. In: Cell Mechanics, Methods in Cell Biology. 1st Ed. Wang YL, Discher DE, editors. Vol 83. Academic Press; San Diego: 2007. pp. 473–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yanagida T, Ishii Y, editors. Single Molecule Dynamics in Life Science. Wiley; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berglund GI, et al. The catalytic pathway of horseradish peroxidase at high resolution. Nature. 2002;417(6887):463–468. doi: 10.1038/417463a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(3):197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferreon ACM, Gambin Y, Lemke EA, Deniz AA. Interplay of alpha-synuclein binding and conformational switching probed by single-molecule fluorescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(14):5645–5650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809232106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: Introducing the D2 concept. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Venkitakrishnan RP, et al. Conformational changes in the active site loops of dihydrofolate reductase during the catalytic cycle. Biochemistry. 2004;43(51):16046–16055. doi: 10.1021/bi048119y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alenghat FJ, Fabry B, Tsai KY, Goldmann WH, Ingber DE. Analysis of cell mechanics in single vinculin-deficient cells using a magnetic tweezer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277(1):93–99. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]