Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of trigeminal parasympathetic pathway (TPP) stimulation in the treatment of dry eye. A comprehensive search for randomized clinical trials was performed in seven databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, etc.) up to 28 February 2023. After screening the suitable studies, the data were extracted and transformed as necessary. Data synthesis and analysis were performed using Review Manager 5.4, and the risk of bias and quality of evidence were evaluated with the recommended tools. Fourteen studies enrolling 1714 patients with two methods (electrical and chemical) of TPP stimulation were included. Overall findings indicate that TPP stimulation was effective in reducing subjective symptom score (standardized mean difference [SMD], -0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.63 to -0.28), corneal fluorescence staining (mean difference [MD], -0.78; 95% CI, -1.39 to -0.18), goblet cell area (MD, -32.10; 95% CI, -54.58 to -9.62) and perimeter (MD, -5.90; 95% CI, -10.27 to -1.53), and increasing Schirmer's test score (SMD, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.65 to 1.31) and tear film break-up time (SMD, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.95). Compared to inactive or low-activity stimulation controls, it has a higher incidence of adverse events. Therefore, TPP stimulation may be an effective treatment for dry eye, whether electrical or chemical. Adverse events are relatively mild and tolerable. Due to the high heterogeneity and low level of evidence, the current conclusions require to be further verified.

Keywords: Dry eye, neuromodulation, neurostimulation, trigeminal parasympathetic pathway

Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface[1] that has developed into one of the most common diseases in ophthalmology clinics, affecting approximately 5% to 50% of the global population, with a prevalence of up to 75% in some specific populations.[2] A loss of homeostasis of the tear film is the main characteristic of dry eye, which is often manifested as eye dryness, foreign body sensation, tingling, itching, redness, tearing, light sensitivity, etc.[3] The hyperosmolarity of tears and the inflammatory event cascade lead to a vicious cycle, which makes dry eye progressive and self-perpetuate,[4] seriously reducing the quality of life and productivity,[2] and even posing a risk of blindness.[5,6] There is no known cure for dry eye, nor is there a universally effective treatment.[7]

The lacrimal functional unit consists of the ocular surface, the main lacrimal gland, and the interconnected innervation,[8] which regulates tear secretion through feedback from the oculolacrimal reflex, the nasolacrimal reflex, and the blink reflex,[4] and plays an important role in maintaining the homeostasis of the ocular surface, and normal function of the eyes and visual system.[9] The oculolacrimal reflex and nasolacrimal reflex transmit nerve impulses from the ocular surface and nasal mucosa to the superior salivatory nucleus region of the brain that controls tear secretion through different terminal branches of the trigeminal nerve and then transmits and innervates the lacrimal gland to secrete tears through the same parasympathetic nerve of the facial nerve.[4,10,11] This pathway, which is afferent from the trigeminal nerve and efferent from the parasympathetic nerve to stimulate tear secretion, is called the trigeminal parasympathetic pathway (TPP).[12] Current research on TPP stimulation focused on the latter, the nasolacrimal reflex. This reflex was first described in detail by Wernoe in 1927 and refers to the stimulation of the nasal mucosa resulting in bilateral lacrimation.[11,13] This pathway is considered to be an important part in both reflex tear and basal tear secretion, contributing about one-third of resting basal secretion through nasal respiration in addition to reflex bolus tearing.[7,14] Hitherto, several clinical trials on TPP stimulation for dry eye have been conducted and have shown that the composition of all three layers (lipid layer, aqueous layer, and mucin layer) of the tear film is increased after stimulation, but the relevant meta-analysis has not yet been reported, which is the significance of this study.

Methods

This meta-analysis strictly followed the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [Supplemental Table S1].[15] In addition, the primary protocol was preregistered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) website under the registration number CRD42023397236.

Supplemental Table S1.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist

PRISMA 2009 Checklist

| Section/topic | # | Checklist item | Reported on page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | 1-2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS). | 2 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (e.g., Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number. | 2 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (e.g., PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (e.g., years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. | 2 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (e.g., databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched. | 2 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | Table S2 |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (i.e., screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis). | 2 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (e.g., piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 2 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (e.g., PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 2 |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | 2 |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (e.g., risk ratio, difference in means). | 2 |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (e.g., I2)for each meta-analysis. | 2 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (e.g., publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | 2 |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | 2 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | 2 |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (e.g., study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations. | 2-3, Table 1 |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment (see item 12). | 3 |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (a) simple summary data for each intervention group (b) effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot. | 3,6-8 |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence intervals and measures of consistency. | 3.6-8 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see Item 15). | 3 |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression [see Item 16]). | 3,7,8 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (e.g., healthcare providers, users, and policy makers). | 8 |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (e.g., risk of bias), and at review-level (e.g., incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias). | 10 |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research. | 10 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (e.g., supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review. | 10 |

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

For more information, visit: www.prisma-statement.orq.

Literature search and study selection

A comprehensive search for potentially eligible randomized clinical trials (RCTs) was performed in seven databases (Ovid Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, Web of Science, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and ClinicalTrials.gov) from database inception until February 28, 2023. No language or other restrictions were set. The main search terms used are as follows: “dry eye,” “xerophthalmia,” “Sjogren’s Syndrome,” and “meibomian gland” were combined with “neuromodulation,” “neurostimulation,” “nerve stimulation,” “nasolacrimal pathway,” and “trigeminal parasympathetic pathway.” The search strategy for Ovid Embase and Ovid MEDLINE is summarized in Supplemental Table S2.

Supplemental Table S2.

Search strategy for Ovid Embase and Ovid MEDLINE

| EMBASE (OVID) search strategy 1. exp randomized controlled trial/ 2. exp randomization/ 3. exp double blind procedure/ 4. exp single blind procedure/ 5. random*.tw. 6. or/1-5 7. (animal or animal experiment).sh. 8. human.sh. 9. 7 and 8 10. 7 not 9 11. 6 not 10 12. exp clinical trial/ 13. (clin* adj3 trial*).tw. 14. ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj3 (blind* or mask*)).tw. 15. exp placebo/ 16. placebo*.tw. 17. random*.tw. 18. exp experimental design/ 19. exp crossover procedure/ 20. exp control group/ 21. exp latin square design/ 22. or/12-21 23. 22 not 10 24. 23 not 11 25. exp comparative study/ 26. exp evaluation/ 27. exp prospective study/ 28. (control* or propspectiv* or volunteer*).tw. 29. or/25-28 30. 29 not 10 31. 11 or 23 32. 30 not 31 33. 11 or 24 or 32 34. exp dry eye/ 35. (dry* adj2 (ocular or eye*)).tw. 36. exp xerophthalmia/ 37. xerophthalmi*.tw. 38. exp keratoconjunctivitis sicca/ 39. (keratoconjunctiv* or 'kerato conjunctivitis').tw. 40. exp sjoegren syndrome/ 41. ((sjogren* or sjoegren*) adj2 (syndrom* or disease*)).tw. 42. (sicca adj1 syndrom*).tw. 43. exp stevens johnson syndrome/ 44. (steven* and johnson and (syndrom* or disease*)).tw. 45. exp mucous membrane pemphigoid/ 46. (benign and muco* and pemphigoid*).tw. 47. cicatricial pemphigoid*.tw. 48. blepharoconjunctiviti*.tw. 49. exp meibomian gland/ 50. ((meibomian or ocular) adj3 gland*).tw. 51. (meibomian or tarsal).tw. 52. exp lacrimal gland disease/ 53. (lacrima* or epiphora).tw. 54. or/34-53 55. (neuromodulation or neurostimulation or 'nerve stimulation').tw. 56. ((lacrimal or tear) adj2 (stimulation or neurostimulation or production or secretion)).tw. 57. ('nasolacrimal reflex' or 'nasolacrimal pathway' or 'NLR' or trigeminal parasympathetic pathway or 'TPP').tw. 58. exp Physical Stimulation/ 59. (physical adj3 stimulation*).tw. 60. exp Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation/ 61. ('TENS' or 'TNS' or 'ENS' or 'TES').tw. 62. ('transcutaneous electric* nerve stimulation' or 'transcutaneous nerve stimulation').tw. 63. ('electric* nerve stimulation' or 'electrostimulation therap*' or 'electro-stimulation therap*').tw. 64. ('transcutaneous electric* stimulation' or 'transcutaneous electrostimulation').tw. 65. exp Electric Stimulation/ 66. (electric* adj3 stimulation*).tw. 67. exp Implantable Neurostimulators/ 68. (implant* adj3 neurostimulator).tw. 69. implanted nerve stimulation electrodes.tw. 70. ((intranasal or extranasal or nasal or external) adj3 (stimulation or neurostimulation or lacrimal or tear)).tw. 71. ('ITN' or 'iTEAR*' or TrueTear).tw. 72. exp Stimulation, Chemical/ 73. (chemical adj3 stimulation*).tw. 74. exp Varenicline/ 75. Vareniclin*.tw. 76. ('6,7,8,9-Tetrahydro-6,10-methano-6H-pyrazino*benzazepine' or Chantix or Champix).tw. 77. ('varenicline solution nasal spray' or 'varenicline nasal spray' or 'VNS').tw. 78. ('OC-01' or 'OC-02' or 'SNS' or Tyrvaya or Simpinicline).tw. 79. or/55-78 80. 54 and 79 81. 33 and 80 MEDLINE (OVID) search strategy 1. Randomized Controlled Trial.pt. 2. Controlled Clinical Trial.pt. 3. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 4. placebo.ab,ti. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab,ti. 7. trial.ab,ti. 8. groups.ab,ti. 9. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 11. 9 not 10 12. exp dry eye syndromes/ 13. (dry* adj2 (ocular or eye*)).tw. 14. exp xerophthalmia/ 15. xerophthalmi*.tw. 16. exp keratoconjunctivitis sicca/ 17. (Keratoconjunctiv* or kerato conjunctivitis).tw. 18. exp Keratoconjunctivitis/ 19. limit 18 to yr="1966 - 1985" 20. exp Sjogren's syndrome/ 21. ((Sjogren* or Sjoegren*) adj (syndrom* or disease*)).tw. 22. sicca syndrom*.tw. 23. exp Stevens Johnson syndrome/ 24. (Steven* and Johnson and (syndrom* or disease*)).tw. 25. exp Pemphigoid, Benign Mucous Membrane/ 26. Benign Muco* Pemphigoid*.tw. 27. Cicatricial Pemphigoid*.tw. 28. blepharoconjunctiviti*.tw. 29. exp meibomian glands/ 30. ((meibomian or ocular) adj3 gland*).tw. 31. (meibomian or tarsal).tw. 32. exp lacrimal apparatus diseases/ 33. (lacrima* or tear* or epiphora).tw. 34. or/12-17,19-33 35. (Neuromodulation or neurostimulation or "nerve stimulation").tw. 36. ((lacrimal or tear) adj2 (stimulation or neurostimulation or production or secretion)).tw. 37. ("nasolacrimal reflex" or "nasolacrimal pathway" or "NLR" or trigeminal parasympathetic pathway or "TPP").tw. 38. exp Physical Stimulation/ 39. (physical adj3 stimulation*).tw. 40. exp Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation/ 41. ("TENS" or "TNS" or "ENS" or "TES").tw. 42. ("transcutaneous electric* nerve stimulation" or "transcutaneous nerve stimulation").tw. 43. ("electric* nerve stimulation" or "electrostimulation therap*" or "electro-stimulation therap*").tw. 44. ("transcutaneous electric* stimulation" or "transcutaneous electrostimulation").tw. 45. exp Electric Stimulation/ 46. (electric* adj3 stimulation*).tw. 47. exp Implantable Neurostimulators/ 48. (implant* adj3 neurostimulator).tw. 49. implanted nerve stimulation electrodes.tw. 50. ((intranasal or extranasal or nasal or external) adj3 (stimulation or neurostimulation or lacrimal or tear)).tw. 51. ("ITN" or "iTEAR*" or TrueTear).tw. 52. exp Stimulation, Chemical/ 53. (chemical adj3 stimulation*).tw. 54. exp Varenicline/ 55. Vareniclin*.tw. 56. ("6,7,8,9-Tetrahydro-6,10-methano-6H-pyrazino(2,3-h)benzazepine" or Chantix or Champix).tw. 57. ("varenicline solution nasal spray" or "varenicline nasal spray" or "VNS").tw. 58. ("OC-01" or "OC-02" or "SNS" or Tyrvaya or Simpinicline).tw. 59. or/35-58 60. 34 and 59 61. 11 and 60 |

The inclusion criteria were as follows: study design: RCT; participants: adults (≥18 years of age) diagnosed with dry eye. Some conditions that may interfere with treatment or efficacy assessment were excluded, including but not limited to recent surgeries, injuries, or active infections in the eyes or nose; any form of punctal or intracanalicular plugs; vascularized nasal polyp; severely deviated septum; severe obstruction in the nasal airway; chronic recurrent epistaxis; nasal continuous positive airway pressure; receiving dry eye treatment other than artificial tears; and allergy to study equipment or drugs. Interventions include studies that compared TPP stimulation (whether by electrical, chemical, or other forms) with conventional treatment (e.g., artificial tears), inactive (sham/placebo), or low-activity stimulation (e.g., applying the intranasal tear neurostimulator (TrueTear™) to extranasal stimulation, which is inconsistent with its original design) controls. One or more of the following outcomes are reported: subjective symptoms scores, Schirmer’s test score, tear film break-up time, secretory function of goblet cell, adverse events, etc. Two independent reviewers identified eligible studies in three steps: eliminating all duplicates; screening titles and abstracts for potential studies; and reading the full text as necessary for a comprehensive evaluation.

Data management and risk-of-bias assessment

A predesigned table was used to extract the following information, including details of the first author, year of publication, country, study design, participant characteristics, intervention methods employed, and changes in outcome measures observed from baseline. For outcome measures that did not elucidate changes from baseline, standard deviations[16] were estimated according to the recommended methodology, while for multi-arm group studies, combined group[17] calculations were performed. Information extraction and data entry were performed by two independent reviewers, with another reviewer checking for accuracy. The risk of bias was assessed and mapped using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.[18]

Data analysis and quality of evidence assessment

In accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,[19] the study employed mean difference (MD) and their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) to summarize the data gathered from continuous outcome measures and as risk ratio (RR) and their corresponding 95% CI for dichotomous outcome measures. In cases where various scales or methods were used to measure the same continuous outcome, standardized mean difference (SMD) were employed as a more suitable approach. The number of included studies and the statistical value of heterogeneity (I2) determined the selection of the effect model, with a random-effects model used when there were >3 studies or I2 ≥50%. Once there was significant heterogeneity (I2 ≥70%) in statistical analysis, in addition to subgroup analysis based on study design, participant characteristics, disease type, intervention (stimulation), and follow-up time, sensitivity analysis was also conducted by excluding each study individually to explore the sources of clinical and methodological heterogeneity. As a consequence of the limited scope of included studies, reporting bias was not assessed.

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system was utilized to evaluate the quality of evidence, which was categorized as high, moderate, low, or very low.[20]

Results

A total of 3592 records were retrieved through a comprehensive search, among which fourteen RCTs[12,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] were included in this meta-analysis [Fig. 1]. NCT03920215[29] was a continuation of the OPP-002 study (Multicenter, randomized, controlled, double-masked clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of OC-01 nasal spray on signs and symptoms of dry eye disease (The ONSET-1 Study) Phase 2b),[12] which evaluated the safety of OC-01 (varenicline solution) nasal spray for up to 6 to 12 months after application.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the fourteen studies. The studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 1),[26] Australia and New Zealand (n = 1),[22] China (n = 1),[21] Mexico (n = 1),[31] and United States (n = 10),[12,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,32,33,34] which were all published between 2017 and 2022. Participants with at least mild dry eye (ocular surface disease index (OSDI) ≥13) were recruited for the studies, and eight studies[12,22,23,24,26,29,30,33,34] specified moderate-to-severe dry eye (OSDI ≥23) as inclusion criteria. Almost all studies had a requirement for basal Schirmer’s test (with or without topical anesthesia) score ≤10–12 mm/5 min and an increase of at least 7 mm in the same eye after swab stimulation compared with pre-stimulation. The number of participants included in the study varied widely, from a minimum of 10[24,26] to a maximum of 758,[34] with an average age ranging from the mid-40s to the mid-60s. Almost all the studies had a higher proportion of females.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study ID Study design | Country Study site (s) | Unit of randomization | Condition (s) included | Treatment group included |

Length of follow-up | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | Intervention |

No. of patients | Control |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Methods | Age (Yr) mean (sd) | Gender (M/F) | Methods | Age (Yr) mean (sd) | Gender (M/F) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Cai MM 2020 parallel group | China single center | Participant | Dry eye | 26 | TES 5 sessions/week + artificial tears 4 times/day, for 4 weeks | 41.2 (14.2) (22 analyzed) | 9/13 (22 analyzed) | 26 | Artificial tears 4 times/day, for 4 weeks | 42.9 (15.1) (23 analyzed) | 10/13 (23 analyzed) | 4 weeks | ||||||||||||

| Cohn GS 2019 parallel group | Australia and New Zealand multicenter (9 sites) | Participant | Dry eye | 32 | ITN (4–8 times/day, 30 s–3 min, for 3 months) | 58.8 (37,79)* | 5/27 | 29 | Sham ITN (4–8 times/day, 30s–3 min, for 3 months) | 66.8 (47, 82)* | 8/21 | 3 months | ||||||||||||

| Dieckmann GM 2022 parallel group | US single center | Participant | Dry eye | 12 | 50 μl single dose of 0.2% OC-01 (varenicline solution) nasal spray in each nostril | 60.5 (13.79) | 1/11 | 6 | 50 μl single dose of placebo (vehicle) nasal spray in each nostril | 63.3 (13.46) | 3/3 | 1 day | ||||||||||||

| Gumus K 2017 crossover | US multicenter (2 sites) | Participant | Dry eye (non-/Sjogren’s syndrome, meibomian gland dysfunction) | Total: 10 | ITN single application for 3 min | Total: 47.9 (8.6) | Total: 1/9 | Total: 10 | Extranasal ITN single application for 3 min | Total: 47.9 (8.6) | Total: 1/9 | ≤44 days | ||||||||||||

| Lilley J 2021 crossover | US single center | Participant | Sjogren’s syndrome | 35 | ITN single application for approximately 3 min | Total: 57 (11.4) | Total: 0/35 | 35 | Extranasal ITN single application for approximately 3 min | Total: 57 (11.4) | Total: 0/35 | 1 day | ||||||||||||

| NCT03274999 2021 crossover | UK single center | Participant | Dry eye | Total: 10 | ITN single application for 3 min | Total: 52.4 (10.1) | Total: 6/4 | Total: 10 | Extranasal ITN single application for 3 min | Total: 52.4 (10.1) | Total: 6/4 | 2 weeks | ||||||||||||

| NCT03633461 2022 parallel group | US multicenter (2 sites) | Participant | Dry eye | 34 | 50 μl 2.0% OC-02 (simpinicline solution) nasal spray in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 63.2 (13.5) | 7/27 | 19 | 50 μl placebo (vehicle) nasal spray in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 64.7 (11.5) | 4/15 | 4 weeks | ||||||||||||

| NCT03827564 2021 parallel group | US single center | Participant | Dry eye | 9 | ITN single application for 3 min | 55.2 (15.4) | 2/7 | 5 | Extranasal ITN single application for 3 min | 46.8 (10.4) | 2/3 | 3 months | ||||||||||||

| Pattar GR 2020 crossover | US multicenter (3 sites) | Participant | Dry eye | Total: 185 | ITN single application for approximately 3 min | Total: 59.0 (12.2) | Total: 47/138 | Total: 185 | Extranasal ITN single application for approximately 3 min | Total: 59.0 (12.2) |

Total: 47/138 | 1 day | ||||||||||||

| Quiroz-Mercado H 2022 parallel group | Mexico single center | Participant | Dry eye | 41 | 50 μl 0.1% OC-01 nasal spray (0.6 mg/ml) in each nostril BID, for 12 weeks | 51.4 (13.2) | 9/32 | 41 | 50 μl placebo (vehicle) nasal spray in each nostril BID, for 12 weeks | 55.8 (13.2) | 8/33 | 3 months | ||||||||||||

| 41 | 50 μl 0.2% OC-01 nasal spray (1.2 mg/ml) in each nostril BID, for 12 weeks | 54.2 (11.8) | 6/35 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sheppard JD 2019 crossover | US multicenter (2 sites) | Participant | Dry eye | Total: 48 | ITN single application for 3 min | 56.9 (13.2) | 9/39 | Total: 48 | Extranasal ITN single application for 3 min | 56.9 (13.2) | 9/39 | 1 day | ||||||||||||

| total: 48 | Sham ITN single application for 3 min | 56.9 (13.2) | 9/39 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Torkildsen GL 2022 parallel group | US multicenter (3 sites) | Participant | Dry eye | 41 | 100 μl single-dose 0.2% OC-02 nasal spray (1.1 mg/ml) in each nostril | 64.4 (11.80) | 17/24 | 42 | 100 μl single-dose placebo (vehicle) nasal spray in each nostril | 64.4 (11.76) | 8/34 | 2 weeks | ||||||||||||

| 41 | 100 μl single-dose 0.2% OC-02 nasal spray (1.1 mg/ml) in each nostril | 64.0 (11.15) | 12/29 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 41 | 100 μl single-dose 2.0% OC-02 nasal spray (11.1 mg/ml) in each nostril | 62.7 (9.30) | 10/31 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wirta D 2022a parallel group | US multicenter (3 sites) | Participant | Dry eye | 47 | 50 μl OC-01 nasal spray (0.12 mg/ml) in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 64.2 (12.7) | 11/36 | 43 | 50 μl placebo (vehicle) nasal spray in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 64.0 (10.3) | 11/32 | 4 weeks | ||||||||||||

| 48 | 50 μl OC-01 nasal spray (0.6 mg/ml) in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 66.5 (9.4) | 14/34 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | 50 μl OC-01 nasal spray (1.2 mg/ml) in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 67.4 (10.6) | 9/35 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Wirta D 2022b parallel group | US multicenter (22 sites) | Participant | Dry eye | 260 | 50 μl 0.1% OC-01 nasal spray (0.6 mg/ml) in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 59.6 (12.8) | 66/194 | 252 | 50 μl placebo (vehicle) nasal spray in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 58.4 (13.3) | 51/201 | 12 months | ||||||||||||

| 246 | 50 μl 0.2% OC-01 nasal spray (1.2 mg/ml) in each nostril BID, for 4 weeks | 58.4 (13.0) | 65/181 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Yr, years; sd, standard deviation; M/F, male or female; TES, transcutaneous electrical stimulation; ITN, intranasal tear neurostimulator; s, second; min, minute; *, mean (range); US, United States; UK, United Kingdom; BID, twice daily.

The included studies described two modalities of activating TPP, namely electrical and chemical stimulation. There were eight studies on electrical stimulation, of which seven were intranasal tear neurostimulators (TrueTear™)[22,24,25,26,28,30,32] acting on the nasal mucosa and one was transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TES)[21] acting on the periorbital area. There were six studies for chemical stimulation, of which four were OC-01 nasal spray[12,23,29,31,34] and two were OC-02 (simpinicline solution) nasal spray.[27,33] The control group consisted of conventional treatment (e.g., artificial tears), inactive (e.g., sham stimulation or placebo), and low-activity (extranasal application with intranasal tear neurostimulator) stimulation. The follow-up period varied from 1 day to 12 months.

Risk-of-bias assessment

The evaluation of potential bias is summarized in Fig. 2. All studies were assessed as low risk or unclear risk in terms of selection bias. Only seven studies[12,22,23,27,31,33,34] were likely to be double-blind, and four studies[24,28,30,31] were rated high risk at attrition bias, mainly due to a high dropout rate or failure to describe adverse events, etc. Two studies were rated as high risk for reporting bias[24,27] and other potential sources of bias,[24,25] respectively. The main reasons for rating are as follows: reported outcome indicators were inconsistent with the protocol, or studies with crossover designs had no washout period and results were not reported separately for each phase, or errors in units of analysis (unequal equal units of analysis and randomization). Considering that almost all of the studies were sponsored by research-related companies and that some of the authors even hold positions in companies, it is considered that there is at least an unclear risk in terms of other potential sources of bias.

Figure 2.

Risk-of-bias summary

Outcome measures

Patient-reported symptom scores

Three scales were used to assess patients’ dry eye symptoms in the included studies, including ocular surface disease index (OSDI), eye dryness score, and ocular discomfort score, with higher scores meaning more severe symptoms and more severe dry eye. Compared with the control group, TPP stimulation therapy reduced the overall symptom score reported by patients (SMD, -0.45; 95% CI, -0.63 to -0.28; I2 = 63%) [Fig. 3]. When subgroup analysis was performed according to the symptom scale [Supplemental Fig. S1 (1.8MB, tif) ], these two groups showed significant differences in the reduction in OSDI score (MD, -5.90; 95% CI, -10.10 to -1.70) and eye dryness score (MD, -9.36; 95% CI, -13.43 to -5.28; I2 = 54%), although there was no difference in the reduction in ocular discomfort score (MD, -0.40; 95% CI, -0.81 to 0.01; I2 = 76%).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of patient-reported symptom scores

Tear film quality and quantity

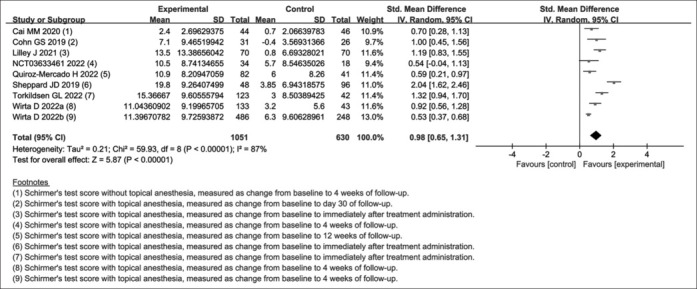

Compared with the control group, the TPP stimulation group increased the Schirmer’s test score (SMD, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.65 to 1.31; I2 = 87%) [Fig. 4] and tear film break-up time (SMD, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.95; I2 = 0%) [Supplemental Fig. S2 (690.6KB, tif) ] and decreased the corneal fluorescein staining score (MD, -0.78; 95% CI, -1.39 to -0.18; I2 = 0%) [Supplemental Fig. S3 (659.9KB, tif) ]. No significant differences were found in tear film protective index (MD, 1.20; 95% CI, -2.11 to 4.51) and exposed area (MD, -0.03; 95% CI, -0.08 to 0.02), tear meniscus height (eye-opening, MD, -0.01; 95% CI, -0.12 to 0.09; eyeblink, MD, 0.01; 95% CI, -0.10 to 0.12) and tear lipid layer thickness (eye-opening, MD, 5.53; 95% CI, -5.12 to 16.18; eyeblink, MD, -1.13; 95% CI, -14.31 to 12.05).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of Schirmer’s test score

To identify the source of the significant heterogeneity in Schirmer’s test score (I2 = 87%), subgroup analysis [Table 2] was conducted from multiple aspects, such as study design (parallel group and crossover), study site (single center and multicenter), study region (America, Oceania, and Asia), type of dry eye (Sjogren’s syndrome and other), severity of dry eye (OSDI ≥23 and other), average age of participants (experimental <control and experimental ≥ control), method of stimulation (electrical and chemical), site of stimulation (periorbital area and nasal mucosa), method of testing (with or without topical anesthesia), and length of follow-up (1 day and ≥2 weeks). Unfortunately, the main source of heterogeneity remains unidentified through multiple subgroup analyses, and it may be caused by multiple factors together. Furthermore, this was confirmed by sensitivity analysis, where the I2 values were all greater than 70% when either study was removed. Only when the two studies by Sheppard JD[32] and Wirta D[34] were removed simultaneously did the I2 values decrease from 87% to 50%. If the study by Torkildsen GL[33] was removed on this basis, the I2 value would decrease further to 30%.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of Schirmer's test score

| Subgroup | No. of Trials | SMD/MD | 95% CI | Heterogeneity |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | I 2 | |||||||||

| Study design | ||||||||||

| parallel-group | 7[12,21,22,27,31,33,34] | 0.79 | (0.55, 1.03) | 0.006 | 67% | |||||

| cross-over | 2[25,32] | 1.61 | (0.78, 2.43) | 0.003 | 89% | |||||

| Study site | ||||||||||

| single center | 3[21,25,31] | 0.84 | (0.46, 1.22) | 0.06 | 65% | |||||

| multi-center | 6[12,22,27,32,33,34] | 1.06 | (0.58, 1.54) | <0.00001 | 91% | |||||

| Study region | ||||||||||

| America | 7[12,25,27,31,32,33,34] | 9.11 | (5.78, 12.45) | <0.00001 | 90% | |||||

| Oceania | 1[22] | 7.5 | (3.90, 11.1) | Not applicable | ||||||

| Asia | 1[21] | 1.7 | (0.7, 2.7) | Not applicable | ||||||

| Type of dry eye | ||||||||||

| Sjogren's syndrome | 1[25] | 1.19 | (0.83, 1.55) | Not applicable | ||||||

| other | 8[12,21,22,27,31,32,33,34] | 0.95 | (0.59, 1.31) | <0.00001 | 87% | |||||

| Severity of dry eye | ||||||||||

| ocular surface disease index ≥23 | 4[12,22,33,34] | 0.92 | (0.51, 1.32) | 0.0005 | 83% | |||||

| other | 5[21,25,27,31,32] | 1.02 | (0.48, 1.57) | <0.00001 | 88% | |||||

| Average age of participantsa | ||||||||||

| experimental < control | 5[21,22,27,31,33] | 0.84 | (0.53, 1.16) | 0.05 | 57% | |||||

| experimental ≥ control | 4[12,25,32,34] | 1.15 | (0.53, 1.77) | <0.00001 | 94% | |||||

| Method of stimulation | ||||||||||

| electrical | 4[21,22,25,32] | 1.24 | (0.67, 1.81) | 0.0001 | 85% | |||||

| chemical | 5[12,27,31,33,34] | 0.78 | (0.47, 1.09) | 0.002 | 76% | |||||

| Site of stimulation | ||||||||||

| periorbital area | 1[21] | 1.7 | (0.7, 2.7) | Not applicable | ||||||

| nasal mucosa | 8[12,22,25,27,31,32,33,34] | 8.92 | (5.95, 11.89) | <0.00001 | 89% | |||||

| Method of testing | ||||||||||

| without topical anesthesia | 1[21] | 1.7 | (0.7, 2.7) | Not applicable | ||||||

| with topical anesthesia | 8[12,22,25,27,31,32,33,34] | 8.92 | (5.95, 11.89) | <0.00001 | 89% | |||||

| Length of follow-up | ||||||||||

| 1 day | 2[25,32] | 1.61 | (0.78, 2.43) | 0.003 | 89% | |||||

| ≥2 weeks | 7[12,21,22,27,31,33,34] | 0.79 | (0.55, 1.03) | 0.006 | 67% | |||||

Indirect assessment of secretory function

The outcome measures for indirect evaluation of tear secretion function include changes in the area or perimeter of conjunctival goblet cell or meibomian gland before and after stimulation and the ratio of degranulated goblet cells. One study[23] evaluated changes in the area or perimeter of conjunctival goblet cell and meibomian gland, which showed a significant decrease in both area (MD, -32.10; 95% CI, -54.58 to -9.62) and perimeter (MD, -5.90; 95% CI, -10.27 to -1.53) of the conjunctival goblet cell after TPP stimulation, while meibomian glands (area, MD, 59.70; 95% CI, -107.88 to 227.28; perimeter, MD, 8.00; 95% CI, -24.86 to 40.85) did not show similar differences. Two other studies[24,28] evaluated the degranulation ratio of goblet cell, and the combined results were not significantly different (SMD, 0.37; 95% CI, -1.77 to 2.51; I2 = 89%) between the two groups. As the outcome measure included only two studies, subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis were not performed.

Adverse events

The incidence of other (not including serious) adverse events (risk ratio (RR), 2.13; 95% CI, 1.47 to 3.09; I2 = 63%) [Fig. 5] related to TPP stimulation was relatively higher compared with controls, with no significant difference in the incidence of serious adverse events (RR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.47 to 2.01; I2 = 0%) [Fig. 5]. Common adverse events included nose discomfort (sneezing, sore, irritation), nosebleed, throat irritation, and eye discomfort (pain, redness, swelling). Generally, these adverse events were mild, transient, and did not require specific treatment.

Figure 5.

Forest plot of adverse events

Quality of the evidence

All outcome measures were of low or moderate quality except for Schirmer’s test score and the goblet cell density ratio, which were of very low quality. These outcome measures were mainly downgraded in terms of risk of bias (at least one study with a high risk of bias found in one or more domains), or inconsistency (e.g., significant heterogeneity or variations in evaluation methodologies), or imprecision (e.g., data came from small sample size studies, and/or 95% CI containing no-effect lines, and/or incorrect units of analysis). Supplemental Table S3 shows a summary of the findings.

Supplemental Table S3.

A summary of the findings

| Trigeminal parasympathetic pathway (TPP) stimulation compared to conventional treatment (e.g., artificial tears), inactive (sham/placebo), or low-activity stimulation for dry eye | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient or population: patients with dry eye Settings: Intervention: TPP stimulation Comparison: conventional treatment (e.g., artificial tears), inactive (sham/placebo), or low-activity stimulation | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Outcomes |

Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI)

|

Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |||||||

|

Assumed risk

Control |

Corresponding risk

TPP stimulation |

|||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Schirmer’s test score | The mean Schirmer’s test score in the intervention groups was 0.98 standard deviations higher (0.65 to 1.31 higher) |

1681 (9 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

SMD 0.98 (0.65 to 1.31) | ||||||||

| Subjective symptom assessment | The mean subjective symptom assessment in the intervention groups was 0.45 standard deviations lower (0.63 to 0.28 lower) |

1860 (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

SMD -0.45 (-0.63 to -0.28) | ||||||||

| Tear film break-up time | The mean tear film break-up time in the intervention groups was 0.57 standard deviations higher (0.19 to 0.95 higher) |

110 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

SMD 0.57 (0.19 to 0.95) | ||||||||

| Corneal fluorescein staining | The mean corneal fluorescein staining in the intervention groups was 0.78 lower (1.39 to 0.18 lower) |

186 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

|||||||||

| Protective index | The mean protective index in the intervention groups was 1.2 higher (2.11 lower to 4.51 higher) |

20 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

|||||||||

| Exposed area | The mean exposed area in the intervention groups was 0.03 lower (0.08 lower to 0.02 higher) |

20 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

|||||||||

| Tear lipid layer thickness (eye-opening) | The mean tear lipid layer thickness (eye-opening) in the intervention groups was 5.53 higher (5.12 lower to 16.18 higher) |

20 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

|||||||||

| Tear lipid layer thickness (eye-blink) | The mean tear lipid layer thickness (eye-blink) in the intervention groups was 1.13 lower (14.31 lower to 12.05 higher) |

20 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

|||||||||

| Tear meniscus height (eye-opening) | The mean tear meniscus height (eye-opening) in the intervention groups was 0.01 lower (0.12 lower to 0.09 higher) |

20 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

|||||||||

| Tear meniscus height (eye-blink) | The mean tear meniscus height (eye-blink) in the intervention groups was 0.01 higher (0.1 lower to 0.12 higher) |

20 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

|||||||||

| Changes in goblet cell - goblet cell area | The mean changes in goblet cell - goblet cell area in the intervention groups was 32.1 lower (54.58 to 9.62 lower) |

10 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

|||||||||

| Changes in goblet cell - goblet cell perimeter | The mean changes in goblet cell - goblet cell perimeter in the intervention groups was 5.9 lower (10.27 to 1.53 lower) |

10 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 |

|||||||||

| Changes in goblet cell - goblet cell density ratio | The mean changes in goblet cell - goblet cell density ratio in the intervention groups was 1.91 higher (2.26 lower to 6.07 higher) |

51 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

|||||||||

| Changes in meibomian gland - meibomian gland area | The mean changes in meibomian gland - meibomian gland area in the intervention groups was 59.7 higher (107.88 lower to 227.28 higher) |

31 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3 |

|||||||||

| Changes in meibomian gland - meibomian gland perimeter | The mean changes in meibomian gland - meibomian gland perimeter in the intervention groups was 8 higher (24.86 lower to 40.85 higher) |

31 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 |

|||||||||

| Adverse events - serious adverse events | Study population | RR 0.93 (0.46 to 1.86) |

1327 (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 |

||||||||

| 25 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 (11 to 46) |

|||||||||||

| Moderate | ||||||||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

|||||||||||

| Adverse events - other (not including serious) adverse events | Study population | RR 1.94 (1.37 to 2.76) |

1994 (11 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

||||||||

| 272 per 1000 | 689 per 1000 (456 to 855) |

|||||||||||

| Moderate | ||||||||||||

| 167 per 1000 | 543 per 1000 (310 to 759) |

|||||||||||

*The basis for the assumed risk (e.g., the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. 1Downgraded one level for risk of bias (one or more studies were high risk of bias in one or more domain). 2Downgraded one level for inconsistency, as significant heterogeneity (I2>70%) or differences in evaluation methods and/or examination position. 3Downgraded one level for imprecision, as data came from studies with small sample sizes, and/or 95% CI includes line of no effect, and/or a unit-of-analysis error

Discussion

Although there are many treatments available for dry eye, unfortunately, a majority of them only provide temporary relief of disease symptoms without addressing the underlying cause or increasing tear production.[22] Too much attention has been paid to additionally supplement or retain tears on the ocular surface, such as various kinds of artificial tears and punctal or intracanalicular plugs, or focused on eliminating inflammation with topical cyclosporine A (CsA), lifitegrast, glucocorticoids, etc.[35] However, the importance of producing endogenous tears to treat dry eye is ignored. Supplemental artificial tears lack the various active ingredients found in endogenous tears (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, immunomodulatory, and growth factors)[31,36,37] and therefore do not perform as well as endogenous tears in maintaining ocular surface homeostasis. This is also the reason why most dry eye patients complain of poor efficacy after using artificial tears. Punctal and intracanalicular plugs are also palliatives, with a loss rate of up to 60%.[35] It is also not advisable to focus primarily on addressing the downstream sequelae of inflammation,[23] as this cannot solve the problem of tear deficiency from the root course. Due to the frequent adverse reactions of these drugs, their widespread application is limited.

Neuromodulation refers to the use of electrical, electromagnetic, chemical, or optogenetic methods to alter and/or modulate neural activity with the goal of correcting physical dysfunction and alleviating disease symptoms.[7,10,35] It has displayed excellent effectiveness in the treatment of movement disorders, psychiatric disorders, chronic pain, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, idiopathic tremor, epilepsy, urinary and fecal incontinence, urinary retention, and obesity.[7,10,38] Since 2009, Kossler et al.[39] found that stimulating the lacrimal gland nerves of Dutch Belted rabbits with implanted nerve stimulators can effectively promote tear secretion (100% more than the baseline),[13] thus unveiling the prolog of neuromodulation therapy for dry eye. It has been reported that the tear flow can be amplified more than one hundred times when stimulated,[40] which offers great potential for neuromodulation to treat dry eye. Hitherto, there has been significant progress in neuromodulation focusing on dry eye, with stimulation modalities ranging from intranasal to extranasal and from electrical to chemical stimulation. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three devices or drugs for the treatment of dry eye, namely the intranasal tear neurostimulator (ITN, TrueTear™), iTEAR, and OC-01 nasal spray. They activate the TPP by intranasal or extranasal electrical stimulation, or by binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on the terminal branches of the trigeminal nerve located in the nasal mucosa, respectively. Unfortunately, the ITN device has recently been discontinued.[25] However, current studies invariably suggest that TPP stimulation is an effective and promising means of treating dry eye, whether by electrical or chemical stimulation.

After an exhaustive search, it can be confirmed that this should be the first meta-analysis to combine different forms of stimulation (electrical or chemical) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TTP stimulation for dry eye. Based on the premise that both promote tear secretion by activating the TPP, this method of combining studies should be reasonable. All included studies activated TPP by stimulating the nasal mucosa (nasolacrimal reflex), except for this study by Cai MM,[21] who used transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TES) to stimulate the skin in the periorbital region (above the temporal area and near the lower eyelid), which is mainly the area innervated by the ophthalmic (V1) and maxillary (V2) branches of the trigeminal nerve. According to Heigle et al.,[41] stimulation of the lacrimal gland is considered a joint effect of sensory inputs from different sources, including the ipsilateral accessory skin, cornea, nasal mucosa, contralateral eye, and even central stimulation.[4] Based on this viewpoint and the specificity of the location of electrical stimulation in this study (where the trigeminal nerve is distributed), this study by Cai MM[21] was also included, and subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis were performed when necessary. The results showed that TES of the periorbital region did improve subjective symptoms and Schirmer’s test scores and promoted tear secretion. Therefore, it can be speculated that TES of the periorbital area should successfully activate the TPP.

A recent meta-analysis[42] showed that electrical stimulation of TPP with an intranasal tear neurostimulator (ITN, TrueTear™) was effective in increasing Schirmer II test score (MD, 14.12; 95% CI, 8.93 to 19.31; I2 = 95%) and reducing meibomian gland area (MD, -251.79; 95% CI, -348.34 to -155.23; I2 = 0%) in dry eye. However, as the authors pointed out, their meta-analysis included a large number of single-arm, open-label, and non-randomized controlled trials, which undoubtedly introduced new risk bias and thus reduced the credibility of this meta-analysis. The current meta-analysis of Schirmer’s test scores did not show such a significant increase (0.98 vs 14.12), which may be related to the method of summary statistics. Because the included studies used different Schirmer’s tests (with or without anesthesia), SMD was used in this summary statistics rather than MD.

Although no direct comparisons have been made between TPP stimulation and treatments such as lifitegrast and CsA, the results of the matching-adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC) showed that the improvement in Schirmer’s test score with the OC-01 nasal spray is much higher than 5% lifitegrast[43] and 0.05% CsA,[44] even several times higher, which is very valuable. Several post hoc studies on OC-01 nasal spray have shown consistent treatment effectiveness in a wide range of dry eye patients, regardless of age, race, ethnicity, artificial tear use,[45] severity (mild, moderate, or severe),[46,47] risk factors (e.g., menopause[48] and use of systemic anticholinergics or antidepressants or anxiolytics),[49] and demonstrated efficacy in both eyes.[47] The treatment benefit results of these subgroups are consistent with the overall trial results of ONSET-1 and ONSET-2.[48,49] However, a premise that should not be overlooked is that the inclusion criteria for almost all studies required Schirmer’s test score to increase by at least 7 mm after swab stimulation compared with pre-stimulation in the same eye. This suggests that TPP stimulation may be more appropriate for patients with mild-to-moderate dry eye or those with good lacrimal gland secretion potential and may have limited efficacy in patients with poor secretion potential (basal Schirmer’s test scores less than 3–4 mm). A randomized controlled trial comparing the relative bioavailability of intranasal and oral varenicline showed that systemic exposure with the highest single intranasal dose (twice the standard dose) of OC-01 varenicline was still lower than the currently approved oral dose for smoking cessation,[50] thus ensuring the safety of intranasal varenicline spray. At the same time, a high concentration of varenicline at the target site (nasal cavity) can bind to more nicotinic acetylcholine receptors located on the terminal branch of the trigeminal nerve[50] and activate the TPP to induce tear secretion. In addition, varenicline is not metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, and the risk of racial differences is low.[51]

TPP (mainly referring to nasolacrimal reflex) stimulation provides a new non-ocular surface contact drug delivery method for dry eye, which has a number of advantages: (1) bypassing the inherent shortcomings of traditional ocular administration, namely low bioavailability (only about 20%),[52] to maximize the consistency of each dose;[31] (2) having lower requirements for fine hand movements and being very friendly for patients with tremor, neck deformity, and difficulty in eye drops;[31] (3) bypassing the afferent pathways of the cornea and conjunctiva to stimulate tear secretion, which is often damaged when the eye suffers from disease and/or pathology.[7,12] The ocular surface is the primary location where the inflammation, tear hypertonicity, and vicious cycle of the dry eye occur, and TPP stimulation skillfully avoids this battlefield. (4) Other advantages are increasing the secretion of tears and improving the symptoms immediately after treatment, and the improvement effect is not reduced after long-term use. This advantage of short-term rapid effect and long-term sustained improvement can undoubtedly improve patient compliance and continuous use.[31]

The meta-analysis shows that TPP stimulation can significantly increase tear secretion and improve dry eye symptoms; however, there are some issues that deserve consideration and further research. Currently, it is believed that the main deficiency in dry eye is the secretion of basic tears.[37] However, the tears produced by TPP stimulation are reflex tears. It is known that the type and concentration of tear proteins are not identical between reflex tears and basal tears.[37,53] Will the differences in tear composition have an impact on the restoration of ocular surface homeostasis? Studies focusing on TPP stimulation have not yet provided a detailed analysis of tear composition. Besides, the longest follow-up period in studies of TPP stimulation is 1 year, mainly with the application of OC-01 intranasal spray.[34] Is there a risk that repeated stimulation over time will reduce the sensitivity of this nerve reflex, thus requiring a greater intensity or dose or higher frequency of stimulation to be effective? Further, when the intranasal tear neurostimulator was administered externally as an active stimulation, it did not produce the same effect on tear secretion as intranasal stimulation.[24,25,26,28,30,32] Nevertheless, a study of the extranasal tear stimulator (iTEAR100) showed significant improvement in both Schirmer’s test score and OSDI score after stimulation.[54] Although both used electrical currents to stimulate the external nasal skin, the results are completely different. Is it caused by the difference in the magnitude of the current, the intensity of stimulation, or the subtle difference in the contact site of the extranasal skin?

Acupuncture in traditional Chinese medicine has a unique therapeutic effect on dry eye, and the acupoints are taken mainly around the periorbital area, such as Jingming, Chengqi, and Sibai, which are all areas of trigeminal nerve distribution. A randomized controlled trial comparing standard acupuncture with sham acupuncture (the sham acupoints are taken near the standard acupoints) for dry eye showed that signs and symptoms improved significantly in both groups, but the difference was not statistically significant.[55] This implies that specific acupoints may not be the only reason for the actual efficacy, and stimulation of their adjacent positions may also be equally effective. Therefore, is the mechanism of acupuncture in treating dry eye related to the activation of TPP?

This meta-analysis has the following limitations and requires caution in its interpretation and application. Firstly, although fourteen studies were included, less than half of the studies had large sample sizes (n >100), and the statistical values of most outcome indicators were obtained by combining one to two studies. Secondly, the quality, baseline levels, and testing methods of the included studies were not identical, and the use of standard deviation estimates, merging of multi-arm group studies, and analysis of change from baseline may have introduced new biases or heterogeneity.[16,19] Thirdly, the effects of different stimulus intensities, frequencies, compositions (varenicline or simpinicline solution), and concentration levels of nasal sprays on TPP activation were not explored and analyzed, which requires further study.

Although there are still some unanswered questions about TPP stimulation, this does not prevent it from being a potentially effective treatment for dry eye. TPP stimulation can increase tear secretion and improve patient symptoms, with either electrical stimulation or chemical stimulation. It has outstanding advantages over the conventional ocular route of administration, with mild and tolerable adverse events that are mostly transient in nature. However, due to the high heterogeneity of the merged results and the relatively low level of evidence, the current conclusion still requires further verification.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Forest plot of subgroup analysis of patient-reported symptom scores

Forest plot of tear film break-up time

Forest plot of corneal fluorescence staining

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Huan Ying for her suggestions and revisions.

References

- 1.Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:276–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, Jalbert I, Lekhanont K, Malet F, et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:334–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan DA, Rocha EM, Aragona P, Clayton JA, Ding J, Golebiowski B, et al. TFOS DEWS II sex, gender, and hormones report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:284–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, Bonini S, Gabison EE, Jain S, et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:438–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Annan J, Chauhan SK, Ecoiffier T, Zhang Q, Saban DR, Dana R. Characterization of effector T cells in dry eye disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3802–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratay ML, Bellotti E, Gottardi R, Little SR. Modern therapeutic approaches for noninfectious ocular diseases involving inflammation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700733. 10.1002/adhm.201700733. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman NJ, Butron K, Robledo N, Loudin J, Baba SN, Chayet A. A nonrandomized, open-label study to evaluate the effect of nasal stimulation on tear production in subjects with dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:795–804. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S101716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern ME, Gao J, Siemasko KF, Beuerman RW, Pflugfelder SC. The role of the lacrimal functional unit in the pathophysiology of dry eye. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:409–16. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barabino S, Chen Y, Chauhan S, Dana R. Ocular surface immunity: Homeostatic mechanisms and their disruption in dry eye disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieckmann G, Fregni F, Hamrah P. Neurostimulation in dry eye disease-past, present, and future. Ocul Surf. 2019;17:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JK, Cremers S, Kossler AL. Neurostimulation for tear production. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019;30:386–94. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wirta D, Torkildsen GL, Boehmer B, Hollander DA, Bendert E, Zeng LJ, et al. ONSET-1 Phase 2b randomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of OC-01 (Varenicline Solution) nasal spray on signs and symptoms of dry eye disease. Cornea. 2022;41:1207–16. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu MD, Park JK, Kossler AL. Stimulating tear production: Spotlight on neurostimulation. Clin Ophthalmol (Auckland, NZ) 2021;15:4219–26. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S284622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta A, Heigle T, Pflugfelder SC. Nasolacrimal stimulation of aqueous tear production. Cornea. 1997;16:645–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Chapter 16: Special topics in statistics. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version (updated March 2011) Cochrane; 2011. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ. Chapter 7: Selecting studies and collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version (updated March 2011) Cochrane; 2011. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 510 (updated March 2011) Cochrane; 2011. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman DG. Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 510 (updated March 2011) Cochrane; 2011. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai MM, Zhang J. Effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical stimulation combined with artificial tears for the treatment of dry eye: A randomized controlled trial. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:175. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohn GS, Corbett D, Tenen A, Coroneo M, McAlister J, Craig JP, et al. Randomized, controlled, double-masked, multicenter, pilot study evaluating safety and efficacy of intranasal neurostimulation for dry eye disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:147–53. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-23984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dieckmann GM, Cox SM, Lopez MJ, Ozmen MC, Yavuz Saricay L, Bayrakutar BN, et al. A Single Administration of OC-01 (Varenicline Solution) nasal spray induces short-term alterations in conjunctival goblet cells in patients with dry eye disease. Ophthalmol Ther. 2022;11:1551–61. doi: 10.1007/s40123-022-00530-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gumus K, Schuetzle KL, Pflugfelder SC. Randomized controlled crossover trial comparing the impact of sham or intranasal tear neurostimulation on conjunctival goblet cell degranulation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;177:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lilley J, O’Neil EC, Bunya VY, Johnson K, Ying GS, Hua P, et al. Efficacy of an intranasal tear neurostimulator in sjögren syndrome patients. Clin Ophthalmol (Auckland, NZ) 2021;15:4291–6. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nct03274999 Clinical Study to Evaluate Tear Characteristics Following Acute TrueTear™ Use. 2017 Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?cond=Nct03274999 . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nct03633461 Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of OC-02 Nasal Spray on Signs and Symptoms of Dry Eye Disease (The RAINIER Study) 2018 Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?cond=Nct03633461 . [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nct03827564 Goblet cell degranulation produced by intranasal tear neurostimulator (ITN) in dry eye disease. 2019 Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?cond=Nct03827564 . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nct03920215 Clinical trial to evaluate the long term follow up of the efficacy of OC-01 nasal spray on signs and symptoms of dry eye disease (The ONSET Study) 2019 Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/search?cond=Nct03920215 . [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pattar GR, Jerkins G, Evans DG, Torkildsen GL, Ousler GW, Hollander DA, et al. Symptom improvement in dry eye subjects following intranasal tear neurostimulation: Results of two studies utilizing a controlled adverse environment. Ocul Surf. 2020;18:249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quiroz-Mercado H, Hernandez-Quintela E, Chiu KH, Henry E, Nau JA. A phase II randomized trial to evaluate the long-term (12-week) efficacy and safety of OC-01 (varenicline solution) nasal spray for dry eye disease: The MYSTIC study. Ocul Surf. 2022;24:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheppard JD, Torkildsen GL, Geffin JA, Dao J, Evans DG, Ousler GW, et al. Characterization of tear production in subjects with dry eye disease during intranasal tear neurostimulation: Results from two pivotal clinical trials. Ocul Surf. 2019;17:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torkildsen GL, Pattar GR, Jerkins G, Striffler K, Nau J. Efficacy and safety of single-dose OC-02 (Simpinicline Solution) nasal spray on signs and symptoms of dry eye disease: The PEARL phase II randomized trial. Clin Ther. 2022;44:1178–86. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2022.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wirta D, Vollmer P, Paauw J, Chiu K-H, Henry E, Striffler K, et al. Efficacy and Safety of OC-01 (Varenicline Solution) nasal spray on signs and symptoms of dry eye disease The ONSET-2 Phase 3 randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2022;129:379–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, Benitez-Del-Castillo JM, Dana R, Deng SX, et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:575–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pflugfelder SC, Stern ME. Biological functions of tear film. Exp Eye Res. 2020;197:108115. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willcox MDP, Argüeso P, Georgiev GA, Holopainen JM, Laurie GW, Millar TJ, et al. TFOS DEWS II tear film report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:366–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson MD, Lim HH, Netoff TI, Connolly AT, Johnson N, Roy A, et al. Neuromodulation for brain disorders: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2013;60:610–24. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2013.2244890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lora A, Wang J, Parel JM, Tse DT. Lacrimal nerve stimulation by a neurostimulator for tear production. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:4244. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bron AJ. Eyelid secretions and the prevention and production of disease. Eye (London, England) 1988;2:164–71. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heigle TJ, Pflugfelder SC. Aqueous tear production in patients with neurotrophic keratitis. Cornea. 1996;15:135–8. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199603000-00005. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Z, Wang X, Li X. Effectiveness of intranasal tear neurostimulation for treatment of dry eye disease: A meta-analysis. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023;12:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s40123-022-00616-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White DE, Hendrix LH, Sun L, Tam I, Macsai M, Gibson AA. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of phase 3 clinical trial outcomes of OC-01 (varenicline solution) nasal spray and lifitegrast 5% ophthalmic solution for the treatment of dry eye disease. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2023;29:69–79. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2022.22208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visco DM, Hendrix LH, Sun L, Tam I, Macsai M, Gibson AA. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of phase 3 clinical trial outcomes: OC–01 (varenicline solution) nasal spray and cyclosporine a 0.05% ophthalmic emulsion for the treatment of dry eye disease. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28:892–902. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2022.22005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Epitropoulos AT, Daya SM, Matossian C, Kabat AG, Blemker G, Striffler K, et al. OC-01 (Varenicline Solution) nasal spray demonstrates consistency of effect regardless of age, race, ethnicity, and artificial tear use. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022;16:3405–13. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S383091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheppard JD, O’Dell LE, Karpecki PM, Raizman MB, Whitley WO, Blemker G, et al. Does dry eye disease severity impact efficacy of varenicline solution nasal spray on sign and symptom treatment outcomes? Optom Vis Sci. 2023;100:164–9. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katz J, Periman LM, Maiti S, Sarnicola E, Hemphill M, Kabat AG, et al. Bilateral Effect of OC-01 (Varenicline Solution) nasal spray for treatment of signs and symptoms in individuals with mild, moderate, and severe dry eye disease. Clin Ther. 2022;44:1463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2022.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nijm LM, Zhu D, Hemphill M, Blemker GL, Hendrix LH, Kabat AG, et al. Does menopausal status affect dry eye disease treatment outcomes with OC-01 (Varenicline Solution) nasal spray? A post hoc analysis of ONSET-1 and ONSET-2 clinical trials. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023;12:355–64. doi: 10.1007/s40123-022-00607-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kabat A, Gibson A, Blemker G, Hendrix L, Macsai M. Analyses of population subgroups with OC-01 (varenicline solution) nasal spray for dry eye disease: Menopause, systemic anticholinergic medication, and systemic antidepressant/anxiolytic medication use. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(10 A-Supplement):S80. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nau J, Wyatt DJ, Rollema H, Crean CS. A Phase I, open-label, randomized, 2-way crossover study to evaluate the relative bioavailability of intranasal and oral varenicline. Clin Ther. 2021;43:1595–607. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu X, Zhang F, Yu M, Ding F, Luo J, Liu B, et al. Semi-PBPK modeling and simulation to evaluate the local and systemic pharmacokinetics of OC-01(Varenicline) nasal spray. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:910629. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.910629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Souto EB, Dias-Ferreira J, López-Machado A, Ettcheto M, Cano A, Camins Espuny A, et al. Advanced formulation approaches for ocular drug delivery: State-of-the-art and recent patents. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11:460. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11090460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Craig JP, Willcox MD, Argüeso P, Maissa C, Stahl U, Tomlinson A, et al. The TFOS International workshop on contact lens discomfort: Report of the contact lens interactions with the tear film subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:TFOS123–56. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13235. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ji MH, Moshfeghi DM, Periman L, Kading D, Matossian C, Walman G, et al. Novel extranasal tear stimulation: Pivotal study results. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9:1–11. doi: 10.1167/tvst.9.12.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shin MS, Kim JI, Lee MS, Kim KH, Choi JY, Kang KW, et al. Acupuncture for treating dry eye: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:e328–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Forest plot of subgroup analysis of patient-reported symptom scores

Forest plot of tear film break-up time

Forest plot of corneal fluorescence staining