Abstract

Aims

To identify promising intervention components that help smokers attain and maintain abstinence during a quit attempt.

Design

A 2×2×2×2×2 randomized factorial experiment.

Setting

Eleven primary care clinics in Wisconsin, USA.

Participants

544 smokers (59% women, 86% White) recruited during primary care visits and motivated to quit.

Interventions

Five intervention components designed to help smokers attain and maintain abstinence: 1) extended medication (26 vs. 8 weeks of nicotine patch + nicotine gum); 2) maintenance (phone) counseling versus none; 3) medication adherence counseling versus none; 4) automated (medication) adherence calls versus none; and 5) electronic medication monitoring with feedback and counseling versus electronic medication monitoring alone.

Measurements

The primary outcome was 7-day self-reported point-prevalence abstinence 1 year after the target quit day.

Findings

Only extended medication produced a main effect. Twenty-six versus eight weeks of medication improved point-prevalence abstinence rates (43% vs. 34% at 6 months; 34% versus 27% at 1 year; p =.01 for both). There were four interaction effects at 1 year, showing that an intervention component’s effectiveness depended upon the components with which it was combined.

Conclusions

Twenty-six weeks of nicotine patch + nicotine gum (versus 8 weeks) and maintenance counseling provided by phone are promising intervention components for the cessation and maintenance phases of smoking treatment.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST), Phase-Based Model of smoking treatment, tobacco dependence, medication adherence, electronic medication monitoring, nicotine replacement therapy, chronic care smoking treatment, relapse prevention, comparative effectiveness, primary care, factorial experiment

INTRODUCTION

Most smokers would like to quit [1]. Of those who try to quit without evidence-based treatment, however, only around 5% succeed in maintaining long-term abstinence [2]. Even with evidence-based treatment, only around 15% to 35% succeed long-term [3]. The majority of smokers relapse early in their quit attempts [4], but even those who achieve abstinence face a meaningful risk of relapse for many months (e.g., [5]). While current cessation treatments quite effectively increase initial abstinence, there is a need for treatments that more effectively maintain it [6–8]. As per the Phase-Based Model of smoking treatment [8, 9] the identification of intervention components that maintain abstinence is critical to effectively treat smokers in the Maintenance phase: the phase of smoking treatment that follows establishment of initial abstinence in the Cessation phase and extends from about 2–4 weeks postquit and onward as needed, and whose goal is maintaining abstinence [9, 10]. Typical challenges to this goal include medication discontinuation or nonadherence, and failure to use coping skills and support.

This research evaluated three promising approaches to increasing long-term abstinence: extended medication, interventions to increase medication adherence, and extended counseling involving coping skill training. This is one of four linked articles. One [10] reviews the theory and methods behind this research; the others report factorial experiments of intervention components for the Motivation [11], and Preparation/Cessation [12] phases of smoking treatment. This experiment evaluated components for the Cessation and Maintenance phases.

Clinical trials comparing extended versus briefer medication have produced mixed results [13–17]. However, research does suggest that providing extended versus briefer medication helps smokers regain abstinence if they lapse [15, 18–20]. Research on cessation medication [3] may not reflect its full potential benefit because only around half or fewer smokers adhere to their prescribed dose and duration of medication [21–24]. Increasing adherence could potentially boost long-term abstinence because medication adherence typically decreases markedly over time (e.g., [25, 26]). However, while medication adherence is positively correlated with abstinence [24, 27–31], the directionality of the causal relation is unclear [21, 23, 27, 29], although cf. [32]. Potential adherence approaches include addressing negative beliefs about medications (e.g., [33]; although [34]), and monitoring, prompting, and providing feedback regarding medication use [23, 34].

Counseling involving coping skill training and support [35, 36] is the most studied approach to increasing long-term abstinence. Such counseling boosts initial cessation, but it is less clear it reliably increases long-term abstinence (cf. [3, 6, 13, 37–39]). Findings are also mixed concerning the benefit of extending such counseling [14, 40–42], illustrating a need for further research.

This experiment evaluated five promising intervention components designed to increase long-term abstinence by addressing challenges patients face during the Cessation and Maintenance phases of smoking treatment. The five components were: Extended Medication, Maintenance Counseling, and three components designed to increase medication adherence (Medication Adherence Counseling, Automated Adherence Calls, and Electronic Medication Monitoring with Feedback and Counseling). Consistent with pragmatic research principles [43], all components and delivery systems were designed for application in real-world healthcare settings. Additionally, this research was guided by the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST: [44–46]) which advocates the use of efficient factorial screening experiments to evaluate multiple intervention components simultaneously. Promising components identified in screening experiments can then be combined into a treatment package to be subsequently evaluated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT [10]).

METHODS

Procedure

This experiment was conducted from June, 2010 through November, 2013. Participants were recruited from 11 primary care clinics in two healthcare systems in southern Wisconsin. Existing clinical care staff (i.e., medical assistants)—prompted by electronic health record technology—invited identified smokers during clinic visits to participate in a research program to help them quit smoking [47, 48]. Patients interested in quitting were randomly assigned to either this experiment or the other cessation experiment described in this issue [12]. It should be noted that although there were three related experiments (this experiment, [11, and 12]), each used an independent, non-overlapping sample.

Interested patients were electronically referred to research staff who then called patients to assess their eligibility. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥18 years; ≥5 cigarettes/day for the previous 6 months; being motivated to quit; able to read, write, and speak English; agreeing to complete assessments; planning to remain in the area for ≥12 months; not currently taking bupropion or varenicline; agreeing to use only study cessation medication during treatment (e.g., discontinuing on-going nicotine replacement therapy [NRT] use); no medical contraindications to NRT; and, for women of childbearing potential, agreeing to use an approved birth control method during treatment.

Eligible patients were invited to return to their primary care clinic to learn about the study and provide informed consent. A research database created intervention and assessment schedules based on participants’ randomly assigned treatment conditions. Clinic-based case managers (bachelor’s level research staff supervised by licensed clinical psychologists) provided study treatment.

Experimental Design

This 2×2×2×2×2 factorial experiment evaluated the effects of five experimental, 2-level factors. Participants were randomized to 1 of 32 unique experimental conditions (see Supplemental Materials Table 1) via a database that used stratified, computer-generated, permuted block randomization, with stratification by gender and clinic, and with a fixed block size of 32 (conditions were randomized within each block). Thus, all 32 conditions were available in each clinic. Staff could not view the allocation sequence. The database did not reveal participants’ treatment condition to staff until participants’ eligibility was confirmed; participants were blinded to treatment condition until they provided consent.

The Five Experimental Factors

All participants received a standard cessation intervention: 8 weeks of nicotine patch + nicotine gum, and 50 minutes of counseling delivered over 4 sessions (in visits 1 week before and 1 week after the target quit day [TQD], and in calls on the TQD and at Week 2). In addition, they were randomized to receive one of two levels of each factor: either an “on” (or more intense) level or an “off” (or less intense) level. (See Supplemental Materials for outlines of counseling protocols and how counseling fidelity was monitored.) The 5 factors were:

Extended Medication

All participants were asked to use Nicotine Patch + Nicotine Gum starting on their TQD. Half were assigned to 8 weeks of patches (>9 cigarettes/day=4 weeks of 21-mg, 2 weeks of 14-mg, and 2 weeks of 7-mg patches; 5–9 cigarettes/day=4 weeks of 14-mg and 4 weeks of 7-mg patches) and gum (smoke within 30 minutes of waking=4 mg; smoke >30 minutes after waking=2 mg), and half were assigned to 26 weeks of patches (>9 cigarettes/day=22 weeks of 21-mg, 2 weeks of 14-mg, and 2 weeks of 7-mg; 5–9 cigarettes/day=22 weeks of 14-mg and 4 weeks of 7-mg) and gum (dosed as above). Participants were advised to use the gum every 1–2 hours and at least 5 pieces/day barring adverse effects.

Maintenance Counseling

Half of participants were assigned to receive Maintenance Counseling consisting of eight 15-minute phone sessions at Weeks 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 14, 18 and 22 after the TQD. The counseling was designed to provide support and encourage continued use of coping skills. Participants who relapsed received counseling aimed at motivating and planning a renewed quit attempt, which has been shown to be effective when delivered via phone [49, 50]. The remaining participants received no Maintenance Counseling.

Medication Adherence Counseling (MAC)

Half of participants received two 10-minute MAC sessions (at visits 1 week pre-TQD and 1 week post-TQD), tailored to correct misconceptions about NRT that might interfere with adherent use [51]. The remaining participants received no MAC.

Automated Adherence Calls

Half of participants received automated medication reminder calls (8 week medication group=7 calls on Days 1, 3, 10, 17, 24, 31, and 45; 26 week medication group=11 calls with the additional calls on Days 73, 101, 129, and 157). The calls included strategies for remembering to use the medication, and brief motivational, supportive, and educational messages to encourage medication compliance [52, 53]. The remaining participants received no Adherence Calls.

Helping Hand (HH) with Feedback and Counseling

All participants carried an HH [54]—a medication dispenser that electronically recorded when the nicotine gum placard was removed from the container. Half of participants received a printout showing how much gum they used daily (as recorded by the HH) plus 10-minute adherence counseling sessions based on the printout (8 week medication group=3 in-person and 2 phone sessions; 26 week medication group=5 in-person and 4 phone sessions). The remaining participants received no HH feedback or related counseling.

Assessments

Participants completed baseline assessments at 1 week pre-TQD including: exhaled carbon monoxide using the Bedfont Smokerlyzer (Bedfont Scientific, Rochester, England), demographics, smoking history, and tobacco dependence (Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence; FTND [55]). Participants completed assessments during visits at Weeks 1, 4, and 8 (plus Week 16 if receiving Extended Medication) with case managers, and during follow-up calls at Weeks 16, 26, 39, and 52 with assessors. Medication adverse events were assessed where relevant. Automated calls assessed medication use and occurred periodically from 9 days pre-TQD through 6 months post-TQD.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was self-reported 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 52 weeks, with a secondary outcome at 26 weeks.1 During all post-TQD visits with case managers and during follow-up calls (including those at 26 and 52 weeks) with assessors not involved in treatment (but not blind to treatment assignment), participants reported cigarettes per day on each of the last 7 days and whether they smoked on each day since last contact in a timeline follow-back interview [56]. Week 52 was primary because this experiment’s chief goal was to increase long-term abstinence. Week 26 was selected because its proximity to treatment delivery might enhance its sensitivity to treatment effects [9] and because it permits comparison with other treatment research.

Analytic Plan

Logistic regression (computed with SPSS [57]) was used to examine point-prevalence abstinence at 26 and 52 weeks. Initial models included all five main effects and all interactions. The logistic regression used effect coding [10] where the “off” level of a factor was coded as −1 and the “on” level was coded as +1. At Week 52, the full logistic regression model could not be fitted (due to a null value cell) so the 5-way interaction was omitted from that model. Analyses were conducted with and without adjustment for a predetermined set of demographic and tobacco dependence covariates: gender, race (White vs. non-White), age, education (up to high school diploma/GED vs. at least some college), the Heaviness of Smoking Index [58], baseline exhaled carbon monoxide, and healthcare system (A vs. B).

All models were intent-to-treat analyses assuming missing=smoking. Primary outcome analyses were supplemented with sensitivity analyses using multiple imputation for missing data [59], which assumed only 80% of dropouts returned to smoking, and that the likelihood of a smoking outcome was related to baseline smoker covariates. Results of the missing=smoking and sensitivity/multiple imputation analyses were highly similar so we present the missing=smoking results only (see Supplemental Materials for sensitivity analyses).

RESULTS

Participants

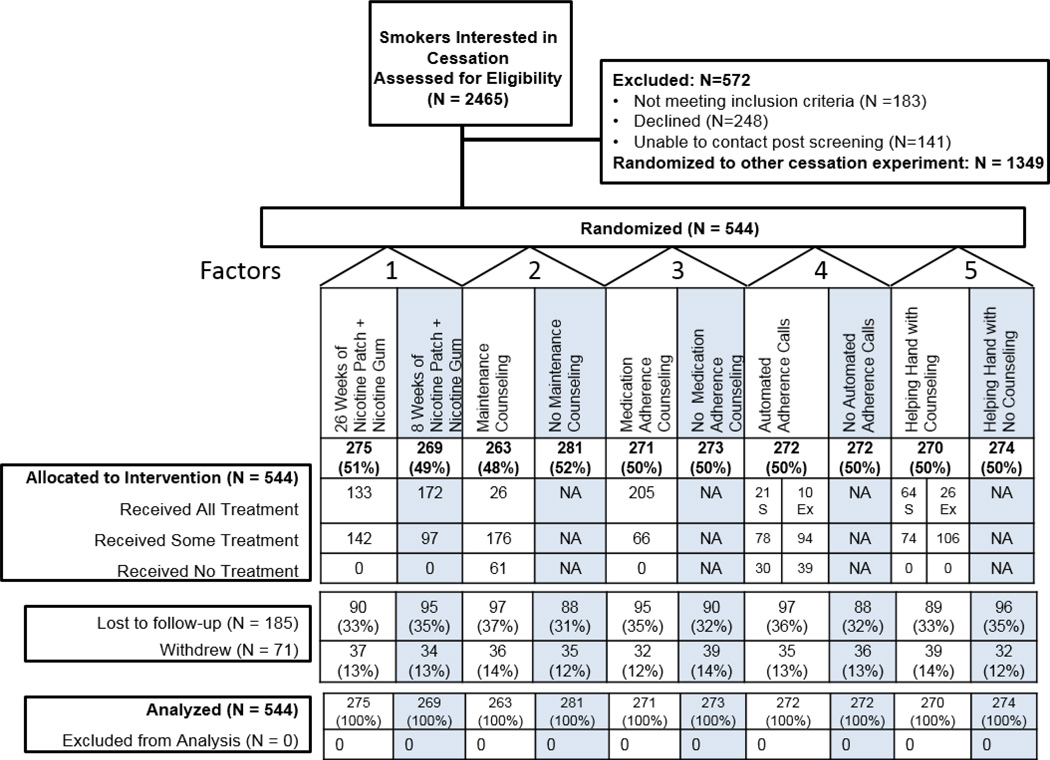

Of smokers recruited during a clinic visit and interested in quitting, 1116 were referred to this experiment, and 544 consented (Figure 1; see Supplemental Materials for sample size justification). See Table 1 for the sample’s demographic and tobacco dependence characteristics. Each of the 11 clinics recruited between 28 and 87 participants.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Note: S = Randomized to Standard 8 Weeks of Nicotine Patch + Nicotine Gum; Ex = Randomized to Extended 26 Weeks of Nicotine Patch + Nicotine Gum. See Supplemental Materials for reasons participants withdrew from the study

Table 1.

Demographic and smoking history characteristics

| Total Sample |

Extended Medication (Nicotine Patch + Nicotine Gum) |

Maintenance (Phone) Counseling |

Medication Adherence Counseling (MAC) |

Automated (Medication) Adherence Calls |

Helping Hand (HH) with Counseling |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 Weeks | 8 Weeks | Maintenance Counseling |

No Maintenance Counseling |

MAC | No MAC | Calls | No Calls | HH Counseling |

No HH Counseling |

||

| Women (%) | 59.0% | 58.9 | 59.1 | 60.1 | 58.0 | 57.2 | 60.8 | 59.6 | 58.5 | 58.5 | 59.5 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 46.2 (12.8) |

46.9 (12.2) |

45.4 (13.3) |

46.4 (12.6) |

46.0 (12.9) |

45.7 (12.5) |

46.7 (13.0) |

46.6 (12.6) |

45.8 (13.0) |

46.1 (13.4) |

46.2 (12.1) |

|

High School diploma or GED only (%) |

33.6 | 31.0 | 36.3 | 38.7 | 28.9 | 33.1 | 34.2 | 34.8 | 32.5 | 31.6 | 35.7 |

| At least some college (%) | 56.9 | 58.4 | 55.4 | 54.4 | 59.2 | 57.2 | 56.6 | 55.2 | 58.6 | 57.7 | 56.3 |

| White (%) | 87.4 | 84.7 | 86.2 | 85.2 | 85.8 | 86.0 | 85.0 | 87.5 | 83.5 | 87.4 | 83.6 |

| African-American (%) | 9.6 | 10.5 | 7.8 | 9.9 | 8.5 | 7.7 | 10.6 | 8.5 | 9.9 | 8.9 | 9.5 |

| Hispanic (%) | 4.2 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 5.2 |

| Healthcare System A* (%) | 59.0 | 64.7 | 53.2 | 58.2 | 59.8 | 58.7 | 59.3 | 57.4 | 60.7 | 58.5 | 59.5 |

| Cigarettes/day (mean, SD) | 18.6 (8.8) |

19.0 (9.0) |

18.2 (8.5) |

18.5 (9.2) |

18.8 (8.4) |

18.6 (8.8) |

18.6 (8.7) |

18.4 (8.4) |

18.9 (9.1) |

18.2 (8.4) |

19.1 (9.1) |

|

Baseline carbon monoxide (mean, SD) |

18.5 (9.9) |

19.1 (10.0) |

18.0 (9.7) |

18.8 (9.7) |

18.3 (10.0) |

18.6 (9.6) |

18.5 (10.1) |

18.2 (9.4) |

18.9 (10.3) |

18.3 (9.6) |

18.8 (10.1) |

| FTND (mean, SD) | 4.9 (2.3) |

4.9 (2.3) |

4.8 (2.2) |

4.8 (2.3) |

4.9 (2.2) |

4.9 (2.3) |

4.9 (2.2) |

4.9 (2.3) |

4.9 (2.2) |

4.8 (2.3) |

4.9 (2.2) |

|

Heaviness of Smoking Index (mean, SD) |

3.2 (1.5) |

3.3 (1.5) |

3.2 (1.5) |

3.2 (1.5) |

3.3 (1.4) |

3.2 (1.5) |

3.2 (1.4) |

3.3 (1.4) |

3.2 (1.5) |

3.2 (1.5) |

3.2 (1.4) |

Note. *The study was conducted in two healthcare systems (A and B). FTND = Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence.

Treatment Engagement

Participants completed a mean of 3.55 (SD=2.83) of 8 Maintenance Counseling sessions and a mean of 1.76 (SD=0.43) of 2 MAC sessions. Participants in the 8-week medication condition completed a mean of 3.67 (SD=1.53) of 5 HH sessions and answered a mean of 3.59 (SD=2.56) of 7 adherence calls. Those in the 26-week medication condition completed a mean of 5.65 (SD=2.74) of 9 HH sessions and answered a mean of 4.85 (SD=3.95) of 11 adherence calls.

Patch and gum use were calculated based on the first 6 or 16 weeks of medication use for the 8- and 26-week medication conditions, respectively. Those assigned 8 versus 26 weeks of medication used the patch a mean of 86.7% and 83.8% of days, respectively (assessed via answered automated calls), and used a mean of 2.67 (SD=2.08) and 2.37 (SD=1.97) pieces of gum/day respectively (assessed via the HH). More extensive medication adherence analyses will be reported in a subsequent paper.

Safety

There were no serious adverse events related to study participation. The most common adverse events for 8 versus 26 Weeks of Nicotine Patch + Nicotine Gum were, respectively: vivid dreams (19% vs. 16%), skin rash (19% vs. 23%), nausea (14% vs. 15%), and insomnia (12% vs. 11%).

Missing Data

The percentage of participants missing abstinence outcome data was 20.4% at Week 26 and 30.0% at Week 52, with no differences observed in missingness across the two levels (on vs. off) of any of the factors.

Smoking Status Outcomes

Table 2 shows the self-reported 7-day point-prevalence abstinence rates for each main effect at Weeks 26 and 52. Table 3 presents the logistic regression results for the unadjusted (primary) and covariate adjusted Week 26 and 52 outcomes. We discuss data from the unadjusted models except where noted; patterns of statistical significance were generally consistent with the adjusted models.

Table 2.

Main Effects for Self-Reported Point-Prevalence Abstinence Rates at 26 and 52 Weeks after the Target Quit Day (N = 544)

| Percent Abstinent at 26 Weeks |

Percent Abstinent at 52 Weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | On | Off | On | Off |

| Extended Medication (Nicotine Patch + Nicotine Gum) |

42.9 | 33.5 | 34.2 | 26.8 |

| Maintenance (Phone) Counseling | 39.2 | 37.4 | 33.1 | 28.1 |

| Medication Adherence Counseling | 37.3 | 39.2 | 28.4 | 32.6 |

| Automated (Medication) Adherence Calls | 39.7 | 36.8 | 29.4 | 31.6 |

| Helping Hand with Counseling | 37.8 | 38.7 | 33.3 | 27.7 |

Note. On = Factor was present or at the longest duration (e.g., 26 weeks of medication). Off = Factor was not present or was at the shortest duration (e.g., 8 weeks of medication).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models for 26 and 52 Week Point-Prevalence Abstinence

| 26 Weeks Post-Target Quit Day | 52 Weeks Post-Target Quit Day | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted** | Unadjusted | Adjusted** | |||||

| Variable | b | p-value | b | p-value | b | p-value | b | p-value |

| Intercept | −.55 | <.001 | −.19 | .72 | −1.01 | <.001 | −1.30 | .02 |

| Extended Medication | .25 | .01 | .28 | .01 | .34 | .01 | .35 | .01 |

| Maintenance Counseling | −.01 | .96 | .01 | .92 | .01 | .96 | −.01 | .94 |

| Medication Adherence Counseling (MAC) |

−.04 | .70 | −.05 | .60 | .02 | .89 | .04 | .78 |

| Automated Adherence Calls | .06 | .58 | .06 | .57 | −.16 | .21 | −.18 | .18 |

| Helping Hand (HH) Counseling | −.01 | .94 | −.05 | .61 | .09 | .51 | .07 | .62 |

| Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling |

.07 | .46 | .04 | .70 | .06 | .68 | .06 | .68 |

| Extended Medication × MAC | −.13 | .20 | −.10 | .35 | −.25 | .046 | −.24 | .06 |

| Extended Medication × Adherence Calls |

.02 | .82 | −.03 | .80 | .18 | .15 | .16 | .21 |

| Extended Medication × HH Counseling |

.04 | .73 | .03 | .76 | .03 | .82 | .03 | .84 |

| Maintenance Counseling × MAC | −.02 | .87 | −.05 | .67 | .12 | .36 | .11 | .42 |

| Maintenance Counseling × Adherence Calls |

.02 | .85 | −.01 | .93 | .15 | .26 | .11 | .40 |

| Maintenance Counseling × HH Counseling |

−.01 | .93 | −.04 | .71 | −.18 | .15 | −.21 | .10 |

| MAC × Adherence Calls | .23 | .02 | .21 | .047 | .44 | .001 | .43 | <.01 |

| MAC × HH Counseling | .09 | .38 | .07 | .50 | .17 | .21 | .18 | .20 |

| Adherence Calls × HH Counseling | −.18 | .07 | −.21 | .047 | −.31 | .03 | −.33 | .02 |

| Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × MAC |

−.13 | .20 | −.13 | .23 | −.20 | .12 | −.20 | .14 |

| Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × Adherence Calls |

.00 | .97 | −.02 | .87 | .08 | .56 | .09 | .50 |

| Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × HH Counseling |

−.08 | .41 | −.19 | .07 | .16 | .20 | .12 | .34 |

| Extended Medication × MAC × Adherence Calls |

−.19 | .050 | −.23 | .03 | −.35 | <.01 | −.38 | <.01 |

| Extended Medication × MAC × HH Counseling |

−.01 | .96 | .01 | .92 | −.13 | .34 | −.14 | .35 |

| Extended Medication × Adherence Calls × HH Counseling |

.15 | .12 | .13 | .22 | .26 | .06 | .24 | .10 |

| Maintenance Counseling × MAC × Adherence Calls |

.16 | .11 | .17 | .11 | .17 | .23 | .18 | .22 |

| Maintenance Counseling × MAC × HH Counseling |

.32 | .001 | .36 | .001 | .35 | <.01 | .37 | <.01 |

| Maintenance Counseling × Adherence Calls × HH Counseling |

−.14 | .17 | −.15 | .16 | −.24 | .08 | −.24 | .08 |

| MAC × Adherence Calls × HH Counseling |

−.22 | .03 | −.25 | .02 | .02 | .87 | .00 | .97 |

| Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × MAC × Adherence Calls |

−.17 | .08 | −.15 | .15 | −.13 | .37 | −.10 | .51 |

| Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × MAC × HH Counseling |

−.18 | .07 | −.20 | .06 | −.26 | .053 | −.27 | .053 |

| Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × Adherence Calls × HH Counseling |

.12 | .23 | .12 | .26 | .18 | .18 | .19 | .18 |

| Extended Medication × MAC × Adherence Calls × HH Counseling |

−.13 | .19 | −.13 | .23 | −.20 | .14 | −.20 | .14 |

| Maintenance Counseling × MAC × Adherence Calls × HH Counseling |

.06 | .54 | .06 | .54 | .13 | .29 | .12 | .33 |

| Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × MAC × Adherence Calls × HH Counseling*** |

.12 | .22 | .13 | .21 | - | - | - | - |

Note. Bold indicates p < .05.

Adjusted model controlled for gender, race (White vs. non-White), age, education (up to high school diploma vs. at least some college), the Heaviness of Smoking Index, baseline exhaled carbon monoxide, and healthcare system (A vs. B); (N = 539 due to missing covariates).

At Week 52, the full logistic regression model could not be fitted (due to a null value cell) so the 5-way interaction was omitted from that model.

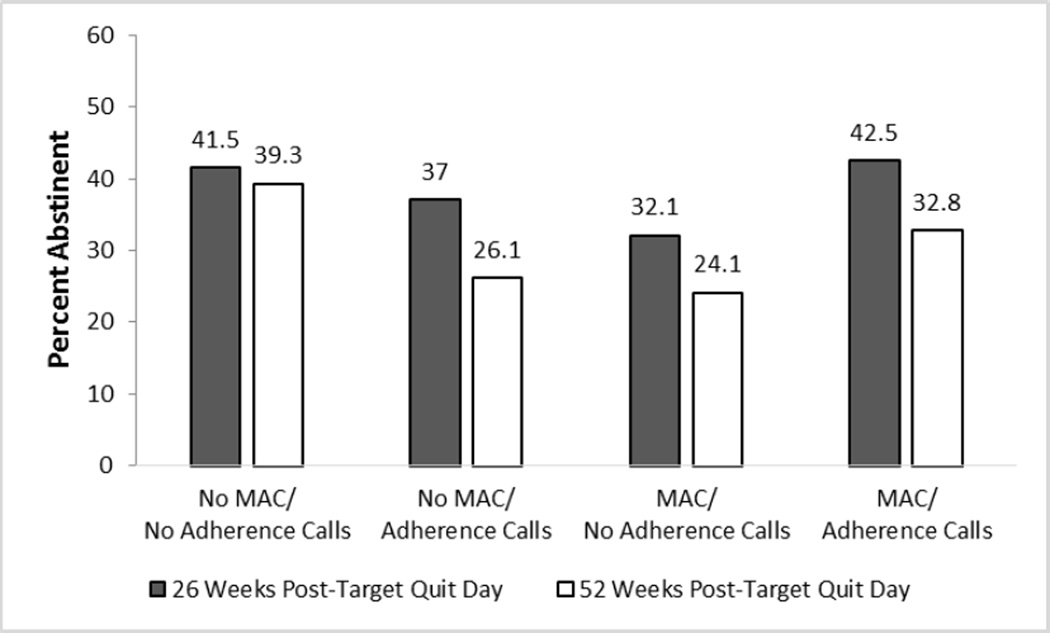

Only one factor produced a significant main effect: 26 versus 8 Weeks of Medication increased abstinence rates (43% vs. 34% at Week 26; 34% versus 27% at Week 52). At Week 52, there was an Extended Medication × MAC interaction showing that amongst participants who received 26 Weeks of Medication, those who received No MAC had a higher mean abstinence rate at Week 52 than those who received MAC (39% vs. 29%; Supplemental Figure 1). There were two 2-way antagonistic interactions (i.e., the effects of two or more components when combined were less than would be expected based on their summed main effects). In the MAC × Adherence Calls interaction (Figure 2), those receiving No MAC and No Adherence Calls had disproportionately higher abstinence rates than those receiving one or both of these adherence interventions. In the Adherence Calls × HH Counseling interaction (Figure 3), HH Counseling without Adherence Calls (Week 52), and Adherence Calls without HH Counseling (Week 26 unadjusted model p=.07; adjusted model p=.047) resulted in the highest abstinence rates, but the combination did not improve abstinence further.

Figure 2.

A Significant Interaction from the 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Outcome Models: Medication Adherence Counseling (MAC) × Automated Adherence Calls Interaction (Significant at Week 26 and Week 52)

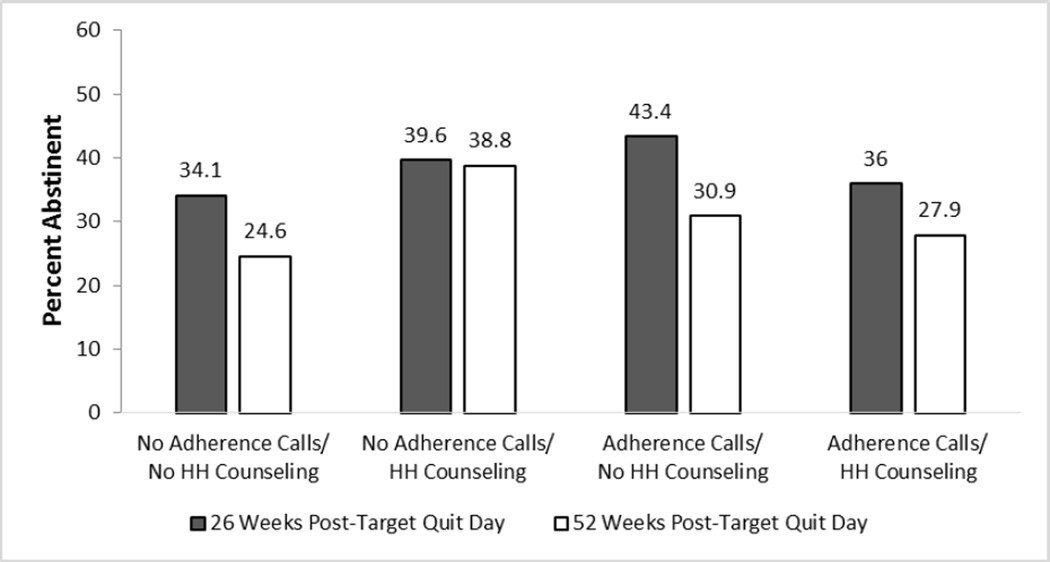

Figure 3.

An Interaction from the 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Outcome Models: Automated Adherence Calls × Helping Hand (HH) Counseling (Week 26 Unadjusted Model p=.07 and Adjusted Model p=.047; Significant at Week 52 in Both the Unadjusted and Adjusted Models)

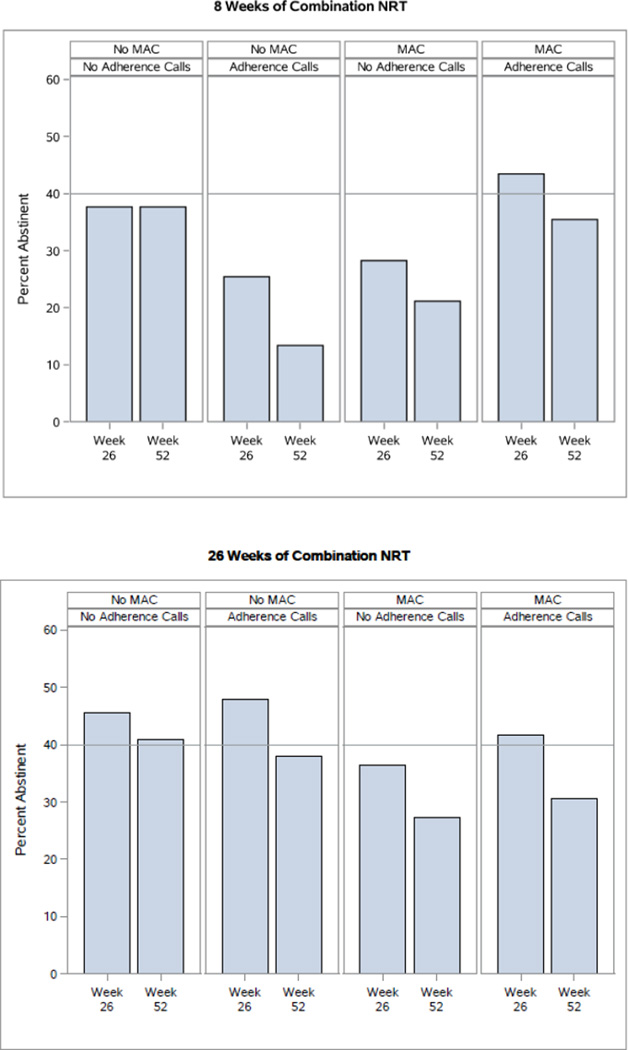

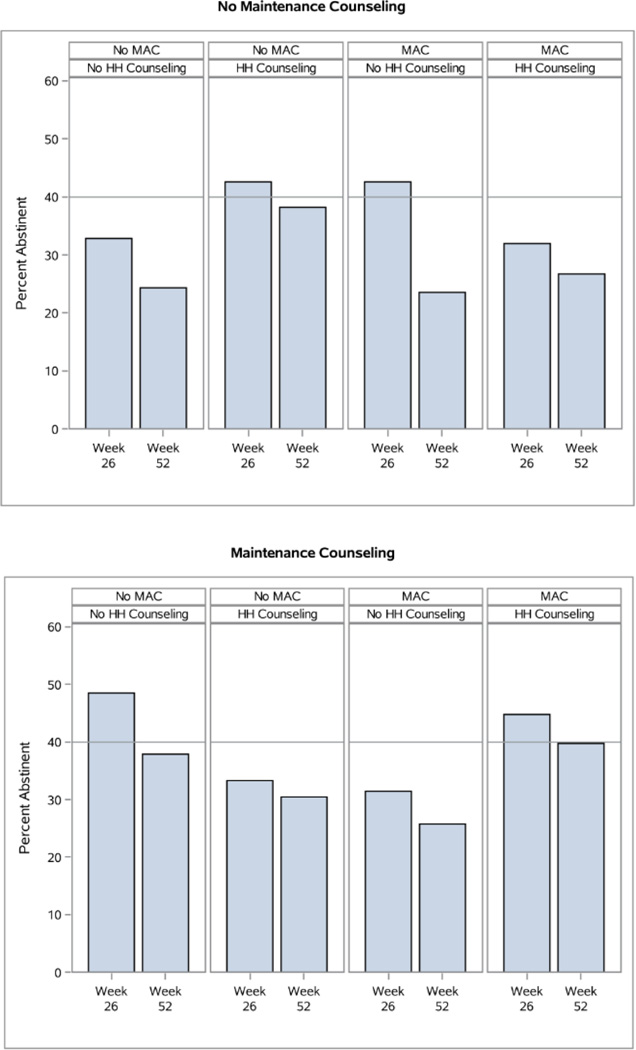

There were two 3-way interactions at Week 52. The Extended Medication × MAC × Adherence Calls interaction (Figure 4) revealed that Extended Medication produced superior results with No Adherence Calls and No MAC (Week 52) or with Adherence Calls but No MAC (Week 26 unadjusted model p=.050; adjusted model p=.03). The Maintenance Counseling × MAC × HH Counseling interaction at Weeks 26 and 52 (Figure 5) revealed that amongst participants receiving neither MAC nor HH Counseling, those receiving Maintenance Counseling showed substantially higher abstinence rates than those not receiving Maintenance Counseling (38% vs. 24% at Week 52). Also, HH Counseling (with No MAC) appeared to interact antagonistically with Maintenance Counseling at Weeks 26 and 52, yielding higher abstinence rates without Maintenance Counseling than with it.

Figure 4.

An Interaction from the 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Outcome Models: Extended Medication (26 vs. 8 Weeks of Combination NRT [Nicotine Replacement Therapy]) × Medication Adherence Counseling (MAC) × Adherence Calls Interaction (Week 26 Unadjusted Model p=.050 and Adjusted Model p=.03; Significant at Week 52 in Both the Unadjusted and Adjusted Models)

Figure 5.

A Significant Interaction from the 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Outcome Models: Maintenance Counseling × Medication Adherence Counseling (MAC) × Helping Hand (HH) Counseling (Significant at Week 26 and Week 52)

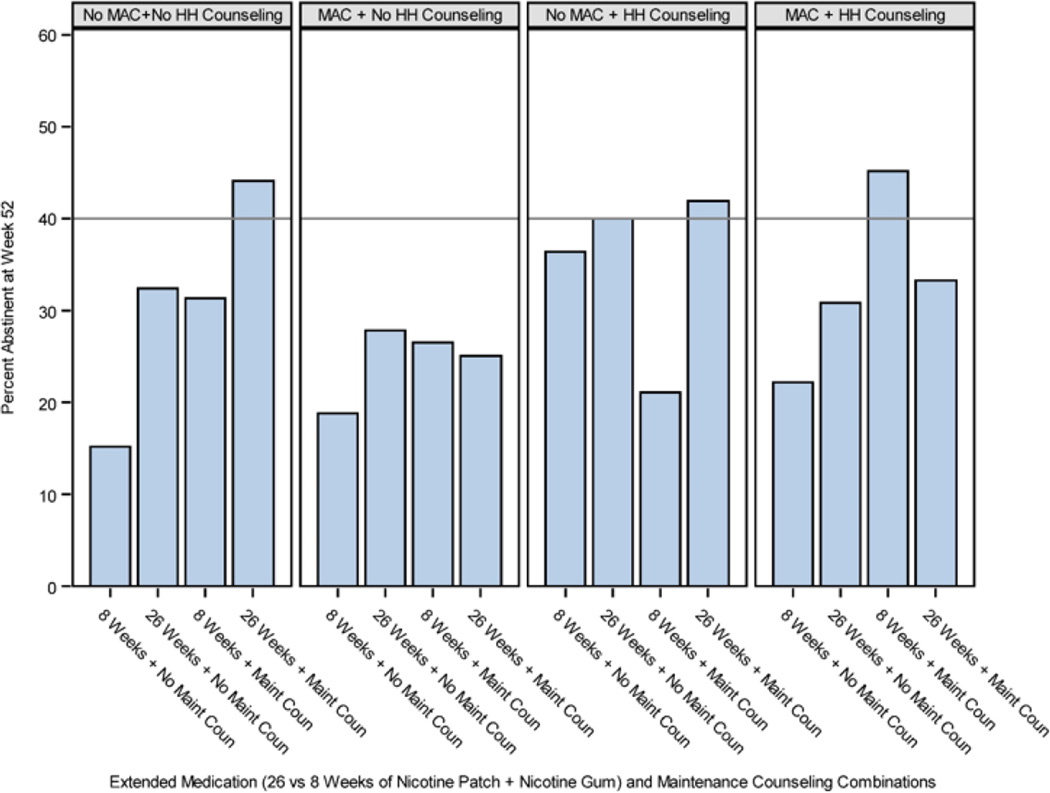

Finally, there was a 4-way interaction at Week 52 at p=.053 involving Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × MAC × HH Counseling (Figure 6). Unpackaging this nonsignificant interaction further informs hypotheses concerning the component interrelations. Amongst those receiving No MAC and No HH Counseling, 8 Weeks of Medication with No Maintenance Counseling resulted in the lowest abstinence rates (15%); 8 Weeks of Medication with Maintenance Counseling, or 26 Weeks of Medication with No Maintenance Counseling, resulted in intermediate quit rates (31% and 32% respectively), and 26 Weeks of Medication with Maintenance Counseling resulted in the highest quit rates (44% at Week 52). Amongst those receiving No MAC, HH Counseling appeared to compensate for an absence of Maintenance Counseling, bringing abstinence rates to approximately the same level as those who received Maintenance Counseling and No HH Counseling. Receiving HH Counseling in addition to Maintenance Counseling did not, however, appear to improve abstinence rates.

Figure 6.

A Non-Significant Interaction from the 7-Day Point-Prevalence Abstinence Outcome Model at Week 52: Extended Medication × Maintenance Counseling × Medication Adherence Counseling (MAC) × Helping Hand (HH) Counseling (p=.053).

Early Abstainer Outcomes

We conducted exploratory analyses to examine results in just those who established early abstinence because such analyses should reflect effects on maintenance of abstinence per se. All full sample analyses were repeated using the 266 participants (49% of the full sample) who established initial abstinence (being smoke-free for at least 5 of the first 7 days of the quit attempt and smoke-free on the 7th day). (This subsample was selected because early abstinence is predictive of long-term outcome (4, 60).) Long-term abstinence rates in this abstainer sample were ~15–20 percentage points higher than in the full sample, but the pattern of abstinence levels was quite similar (albeit p-values were higher due to the smaller sample size; see Supplemental Tables 3–4).

DISCUSSION

This factorial screening experiment demonstrated that execution of a 5-factor factorial design was feasible, and revealed a single main effect (Extended Medication) and multiple interaction effects. This experiment identified intervention components that exerted especially promising effects on long-term abstinence (Extended Medication and Maintenance Counseling). Extended Medication significantly increased abstinence rates at both 26 and 52 weeks post-TQD. Interaction effects suggested that Maintenance Counseling also meaningfully increased abstinence rates depending on the components with which it was combined; i.e., Maintenance Counseling (when not combined with MAC or HH Counseling) generally produced relatively high abstinence rates that were not significantly incremented by other components (Figures 5 and 6). Amongst the medication adherence factors, Adherence Calls and HH Counseling showed modest and mixed evidence of effectiveness, while MAC produced little or no benefit.

The interpretation of the interactions obtained is challenging due to their complexity. To simplify interpretation, we focus on what we see as the strongest signals amongst the interacting components. There was evidence that either Adherence Calls or HH Counseling by themselves were beneficial, relative to receiving neither of those components (Figure 3). The combination of these two components did not further boost abstinence rates, however. HH Counseling showed some promise when offered with No MAC and No Maintenance Counseling (Figure 5). However, HH Counseling and Maintenance Counseling appeared to play similar roles (both offered regular contact and social support), and offering them together did not appear more effective than offering Maintenance Counseling without HH Counseling (Figures 5 and 6). Moreover, Maintenance Counseling and Extended Medication appeared to be the strongest combination, all things considered (Figure 6).

None of the three adherence factors (MAC, Adherence Calls, HH Counseling) produced meaningful long-term benefit beyond what Extended Medication and Maintenance Counseling produced. In addition, matching previous findings with MAC [51], none of the adherence factors produced a significant main effect (if anything, MAC lowered abstinence somewhat). These findings suggest that reminding people to take their medication, and tracking and providing feedback on medication use, produced only modest and inconsistent increases in abstinence, and attempting to assess and then correct beliefs about cessation medication may have actually been counterproductive. Further research on cessation medication adherence is clearly needed [32].

Interaction effects amongst components were common, and many were antagonistic [10]. For example, Maintenance Counseling generally produced better results when used with neither HH Counseling nor MAC (Figures 5 and 6). Thus, combining components into treatments without a comprehensive analysis of interactions could result in treatment packages comprising inert or suboptimal components. Antagonistic interactions may be caused by several factors. In some cases an added component might increase distraction or burden, interfering with the effectiveness of the component with which it is paired (see [14, 40, 61, 62] for other cases where adding intervention components appears to reduce benefit). In addition, components may activate mechanisms that are antagonistic to one another. For instance, the provision of a very directive behavioral intervention that stresses avoidance of smoking cues and urges might produce attentional effects that interfere with the effects of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which emphasizes non-suppressive processing and acceptance of such stimuli (e.g., [63]). Finally, it is important to note that in some cases intervention components may produce an antagonistic interaction, but the effect of the component combination is still greater than is the effect of each component by itself (the joint effects are only partially additive). Such combinations might, therefore, be considered for possible inclusion in a treatment package.

This research highlights the value of the MOST approach [44]. In particular, the factorial design allowed for the screening of five unique intervention components in a single experiment. However, one limitation of this research is that it only suggests which components might work well together; a definitive test requires an RCT. Also, consistent with this screening experiment’s goal of hypothesis generation, this experiment was not powered for simple effects (i.e., conditional main effects) tests; therefore, interactions were interpreted via an appraisal of consistent patterns of effects (see [10]) and require replication to support strong inference. Further, the effects obtained in this experiment reflect effects on both initial abstinence attainment and maintenance (relapse prevention, late re-quitting). When we examined treatment effects in just those who had attained initial abstinence (to test maintenance effects per se), we obtained a similar pattern of findings as in the full sample, but few findings were significant, reflecting in part, a lack of power due to the reduced sample. Compliance with the intervention components was adequate considering the pragmatic nature of the research; future analyses will address the effects of the medication adherence components on compliance. Clearly, future research is needed to: replicate these findings, evaluate a broader range and intensity of components, and provide additional insight into the complex interactions.

CONCLUSION

The goal of this research was to use the MOST approach to identify Cessation- and Maintenance-phase intervention components that increase long-term abstinence amongst smokers. This research demonstrated the feasibility of executing factorial designs that test multiple intervention components, and it identified components that enhanced long-term abstinence from smoking. In particular, Extended Medication (26 Weeks of Combination NRT) and Maintenance Counseling yielded promising effects and appeared to work well together. While these components are good candidates for possible inclusion in a comprehensive, chronic care treatment for smoking, additional research is needed in the form of an RCT to determine how well they work as an integrated treatment package [44]. Finally, this research showed that components often interacted with one another, and such interactions sometimes reflected a component’s diminished effect when paired with other components. These findings raise questions about the relation between treatment intensity and benefit and underscore the importance of evaluating both intervention component main and interaction effects, as this research did, prior to combining promising components into a smoking treatment package.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration of Interest: This research was supported by grants 9P50CA143188 and 1K05CA139871 from the National Cancer Institute to the University of Wisconsin Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention and by the Wisconsin Partnership Program. This work was carried out in part while Dr. Schlam was a Primary Care Research Fellow supported by a National Research Service Award (T32HP10010) from the Health Resources and Services Administration to the University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine. Dr. Loh is also supported by National Science Foundation grant DMS-1305725. Dr. Collins is also supported by NIH grants P50DA10075 and R01DK097364. Dr. Cook is supported by Merit Review Award 101CX00056 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors have received no direct or indirect funding from, nor do they have a connection with, the tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical or gaming industries or anybody substantially funded by one of these organizations. Dr. Loh is partially supported by a grant from Eli Lilly and Company for research that is unrelated to smoking or tobacco dependence treatment.

We would like to acknowledge the staff at Aurora Health Care, Deancare, and Epic Systems Corporation for their collaboration in this research. We are very grateful to the staff and students at the Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention in the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health for their help with this research.

Footnotes

Based upon reviewer recommendations, the designation of primary and secondary outcomes was altered from what was listed in trial registration materials.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01120704

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults - United States 2001–2010. MMWR. 2011;60:1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, Curry SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenford SL, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Wetter D, Baker TB. Predicting smoking cessation. Who will quit with and without the nicotine patch. JAMA. 1994;271:589–594. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.8.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B, Gilsenan AW, Coste F, West R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict Behav. 2009;34:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandon TH, Vidrine JI, Litvin EB. Relapse and relapse prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:257–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, McCarthy DE, Baker TB. Have we lost our way? The need for dynamic formulations of smoking relapse proneness. Addiction. 2002;97:1093–1108. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlam TR, Baker TB. Interventions for tobacco smoking. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:675–702. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker TB, Mermelstein R, Collins LM, Piper ME, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, et al. New methods for tobacco dependence treatment research. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:192–207. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker TB, Collins LM, Mermelstein R, Piper ME, Schlam TR, Cook JW, et al. Enhancing the effectiveness of smoking treatment research: conceptual bases and progress. Addiction. doi: 10.1111/add.13154. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook JW, Baker TB, Fiore MC, Smith SS, Fraser D, Bolt DM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of motivation phase intervention components for use with smokers unwilling to quit: a factorial screening experiment. Addiction. doi: 10.1111/add.13161. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piper ME, Fiore MC, Smith SS, Fraser D, Bolt DM, Collins LM, et al. Identifying effective intervention components for smoking cessation: a factorial screening experiment. Addiction. doi: 10.1111/add.13162. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajek P, Stead LF, West R, Jarvis M, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD003999. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003999.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Munoz RF, Reus VI, Robbins JA, Prochaska JJ. Extended treatment of older cigarette smokers. Addiction. 2009;104:1043–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Wileyto EP, Heitjan DF, Shields AE, Asch DA, et al. Effectiveness of extended-duration transdermal nicotine therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:144–151. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-3-201002020-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonstad S, Tonnesen P, Hajek P, Williams KE, Billing CB, Reeves KR. Effect of maintenance therapy with varenicline on smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:64–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnoll RA, Goelz PM, Veluz-Wilkins A, Blazekovic S, Powers L, Leone FT, et al. Long-term nicotine replacement therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:504–511. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson SG, Gitchell JG, Shiffman S. Continuing to wear nicotine patches after smoking lapses promotes recovery of abstinence. Addiction. 2012;107:1349–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japuntich SJ, Piper ME, Leventhal AM, Bolt DM, Baker TB. The effect of five smoking cessation pharmacotherapies on smoking cessation milestones. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:34–42. doi: 10.1037/a0022154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiffman S, Scharf DM, Shadel WG, Gwaltney CJ, Dang Q, Paton SM, et al. Analyzing milestones in smoking cessation: illustration in a nicotine patch trial in adult smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balmford J, Borland R, Hammond D, Cummings KM. Adherence to and reasons for premature discontinuation from stop-smoking medications: data from the ITC Four-Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:94–102. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam TH, Abdullah AS, Chan SS, Hedley AJ. Adherence to nicotine replacement therapy versus quitting smoking among Chinese smokers: a preliminary investigation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;177:400–408. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1971-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmitz JM, Sayre SL, Stotts AL, Rothfleisch J, Mooney ME. Medication compliance during a smoking cessation clinical trial: a brief intervention using MEMS feedback. J Behav Med. 2005;28:139–147. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-3663-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catz SL, Jack LM, McClure JB, Javitz HS, Deprey M, Zbikowski SM, et al. Adherence to varenicline in the COMPASS smoking cessation intervention trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:361–368. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stapleton JA, Russell MA, Feyerabend C, Wiseman SM, Gustavsson G, Sawe U, et al. Dose effects and predictors of outcome in a randomized trial of transdermal nicotine patches in general practice. Addiction. 1995;90:31–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiggers LC, Smets EM, Oort FJ, Storm-Versloot MN, Vermeulen H, van Loenen LB, et al. Adherence to nicotine replacement patch therapy in cardiovascular patients. Int J Behav Med. 2006;13:79–88. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1301_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hays JT, Leischow SJ, Lawrence D, Lee TC. Adherence to treatment for tobacco dependence: association with smoking abstinence and predictors of adherence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:574–581. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Killen JD, Robinson TN, Ammerman S, Hayward C, Rogers J, Stone C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of bupropion combined with nicotine patch in the treatment of adolescent smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:729–735. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raupach T, Brown J, Herbec A, Brose L, West R. A systematic review of studies assessing the association between adherence to smoking cessation medication and treatment success. Addiction. 2014;109:35–43. doi: 10.1111/add.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiffman S. Use of more nicotine lozenges leads to better success in quitting smoking. Addiction. 2007;102:809–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shiffman S, Sweeney CT, Ferguson SG, Sembower MA, Gitchell JG. Relationship between adherence to daily nicotine patch use and treatment efficacy: secondary analysis of a 10-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial simulating over-the-counter use in adult smokers. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1852–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollands GJ, McDermott MS, Lindson-Hawley N, Vogt F, Farley A, Aveyard P. Interventions to increase adherence to medications for tobacco dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD009164. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009164.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fucito LM, Toll BA, Salovey P, O’Malley SS. Beliefs and attitudes about bupropion: implications for medication adherence and smoking cessation treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:373–379. doi: 10.1037/a0015695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mooney ME, Sayre SL, Hokanson PS, Stotts AL, Schmitz JM. Adding MEMS feedback to behavioral smoking cessation therapy increases compliance with bupropion: a replication and extension study. Addict Behav. 2007;32:875–880. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Individualized behavior therapy for alcoholics. Behav Ther. 1973;4:49–72. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agboola S, McNeill A, Coleman T, Leonardi Bee J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smoking relapse prevention interventions for abstinent smokers. Addiction. 2010;105:1362–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carroll KM. Relapse prevention as a psychosocial treatment: A review of controlled clinical trials. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;4:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, Wang MC. Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:563–570. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Munoz RF, Cullen J. Extended nortriptyline and psychological treatment for cigarette smoking. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2100–2107. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lancaster T, Stead LF. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001292. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Behavioural interventions as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD009670. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009670.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glasgow RE. What does it mean to be pragmatic? Pragmatic methods, measures, and models to facilitate research translation. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40:257–265. doi: 10.1177/1090198113486805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins LM, Baker TB, Mermelstein RJ, Piper ME, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, et al. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy for engineering effective tobacco use interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:208–226. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9253-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Nair VN, Strecher VJ. A strategy for optimizing and evaluating behavioral interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:65–73. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5 Suppl):S112–S118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fraser D, Christiansen BA, Adsit R, Baker TB, Fiore MC. Electronic health records as a tool for recruitment of participants’ clinical effectiveness research: lessons learned from tobacco cessation. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3:244–252. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0143-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piper ME, Baker TB, Mermelstein R, Collins LM, Fraser DL, Jorenby DE, et al. Recruiting and engaging smokers in treatment in a primary care setting: developing a chronic care model implemented through a modified electronic health record. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3:253–263. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lando HA, Pirie PL, Roski J, McGovern PG, Schmid LA. Promoting abstinence among relapsed chronic smokers: The effect of telephone support. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1786–1790. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.12.1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lichtenstein E, Glasgow RE, Lando HA, Ossip-Klein DJ, Boles SM. Telephone counseling for smoking cessation: rationales and meta-analytic review of evidence. Health Educ Res. 1996;11:243–257. doi: 10.1093/her/11.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith SS, Keller PA, Kobinsky KH, Baker TB, Fraser DL, Bush T, et al. Enhancing tobacco quitline effectiveness: identifying a superior pharmacotherapy adjuvant. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:718–728. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.May S, West R, Hajek P, Nilsson F, Foulds J, Meadow A. The use of videos to inform smokers about different nicotine replacement products. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:143–147. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.World Health Organization. Disease-specific reviews: Tobacco smoking cessation. In: World Health Organization, editor. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva: 2003. pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Bleser L, Vincke B, Dobbels F, Happ MB, Maes B, Vanhaecke J, et al. A new electronic monitoring device to measure medication adherence: usability of the Helping Hand. Sensors (Basel) 2010;10:1535–1552. doi: 10.3390/s100301535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28:154–162. doi: 10.1037/a0030992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict. 1989;84:791–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ, Demirtas H. Analysis of binary outcomes with missing data: missing = smoking, last observation carried forward, and a little multiple imputation. Addiction. 2007;102:1564–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garvey AJ, Bliss RE, Hitchcock JL, Heinold JW, Rosner B. Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: A report from the Normative Aging Study. Addict Behav. 1992;17:367–377. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90042-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baker TB, Hawkins R, Pingree S, Roberts LJ, McDowell HE, Shaw BR, et al. Optimizing eHealth breast cancer interventions: which types of eHealth services are effective? Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:134–145. doi: 10.1007/s13142-010-0004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fraser D, Kobinsky K, Smith SS, Kramer J, Theobald WE, Baker TB. Five population-based interventions for smoking cessation: a MOST trial. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4:382–390. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hernandez-Lopez M, Luciano MC, Bricker JB, Roales-Nieto JG, Montesinos F. Acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation: a preliminary study of its effectiveness in comparison with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:723–730. doi: 10.1037/a0017632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.