Abstract

Background and aims Many fruits soften during ripening, which is important commercially and in rendering the fruit attractive to seed-dispersing animals. Cell-wall polysaccharide hydrolases may contribute to softening, but sometimes appear to be absent. An alternative hypothesis is that hydroxyl radicals (•OH) non-enzymically cleave wall polysaccharides. We evaluated this hypothesis by using a new fluorescent labelling procedure to ‘fingerprint’ •OH-attacked polysaccharides.

Methods We tagged fruit polysaccharides with 2-(isopropylamino)-acridone (pAMAC) groups to detect (a) any mid-chain glycosulose residues formed in vivo during •OH action and (b) the conventional reducing termini. The pAMAC-labelled pectins were digested with Driselase, and the products resolved by high-voltage electrophoresis and high-pressure liquid chromatography.

Key Results Strawberry, pear, mango, banana, apple, avocado, Arbutus unedo, plum and nectarine pectins all yielded several pAMAC-labelled products. GalA–pAMAC (monomeric galacturonate, labelled with pAMAC at carbon-1) was produced in all species, usually increasing during fruit softening. The six true fruits also gave pAMAC·UA-GalA disaccharides (where pAMAC·UA is an unspecified uronate, labelled at a position other than carbon-1), with yields increasing during softening. Among false fruits, apple and strawberry gave little pAMAC·UA-GalA; pear produced it transiently.

Conclusions GalA–pAMAC arises from pectic reducing termini, formed by any of three proposed chain-cleaving agents (•OH, endopolygalacturonase and pectate lyase), any of which could cause its ripening-related increase. In contrast, pAMAC·UA-GalA conjugates are diagnostic of mid-chain oxidation of pectins by •OH. The evidence shows that •OH radicals do indeed attack fruit cell wall polysaccharides non-enzymically during softening in vivo. This applies much more prominently to drupes and berries (true fruits) than to false fruits (swollen receptacles). •OH radical attack on polysaccharides is thus predominantly a feature of ovary-wall tissue.

Keywords: Fruit, ripening, cell wall, pectic polysaccharides, hydroxyl radicals, non-enzymic scission, fluorescent labelling, fingerprint compounds

INTRODUCTION

Ripening: hydrolytic vs. oxidative

Fruit ripening is often accompanied by changes in flavour, odour, colour and texture which are attractive to the animals that will disperse the seeds. In particular, many berries, drupes and pomes soften during ripening owing to changes in cell wall organization. Plant cell walls are complex networks based on cellulose microfibrils, partly tethered by hemicelluloses, with pectic polysaccharides infiltrating the rest of the wall matrix (Albersheim et al., 2010; Fry, 2011a). During fruit softening, the matrix polysaccharides, especially the pectins, often become more readily extractable and/or decrease in molecular weight, indicating depolymerization, e.g. in avocado, plum, mango, banana and tomato (Huber and O’Donoghue, 1993; Prasanna et al., 2003; Ali et al., 2004; Ponce et al., 2010; Basanta et al., 2014). The importance of pectic depolymerization has led to the widely held view that ripening can be regarded as principally a ‘hydrolytic’ process.

Earlier, however, Blackman and Parija (1928) had suggested that ripening involves a loss of ‘organisational resistance’, i.e. fruit cells lose the ability to maintain separate compartments owing to cellular (membrane) degeneration. Although this concept lost popularity, some workers continued to interpret ripening as a form of senescence attributable to oxidation reactions (Brennan and Frenkel, 1977) and more recently to emphasize the (possibly related) decrease in water content that occurs near the onset of ripening (Frenkel and Hartman, 2012). There are indeed similarities between physiological changes (e.g. chlorophyll loss and membrane permeabilization) occurring in a ripening fruit and in a leaf or petal approaching abscission. Lipoxygenases, which often increase during ripening (Ealing, 1994; de Gregorio et al., 2000), generate hydroperoxide groups (>CH–OOH) in unsaturated fatty acid residues, accompanied by the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Such lipid oxidation may permeabilize membranes, resulting in the release of certain metabolites, e.g. ascorbate (Dumville and Fry, 2003), into the apoplast (the aqueous solution that bathes the cell wall), and ROS by-products may drive other oxidative reactions.

Viewing fruit ripening as an ‘oxidative’ process is supported by evidence from several quarters. For example, in avocado (Lauraceae; Meir et al., 1991) and serviceberry (Rosaceae; Rogiers et al., 1998), lipid peroxidation was the earliest symptom of ripening, and tomato (Solanaceae) fruit ripening was accompanied by elevated H2O2 and the oxidation of lipids and proteins (Jimenez et al., 2002). In the present study, we propose a link between oxidative agents (especially the hydroxyl radical, •OH) and pectic polysaccharide degradation in softening fruit.

Wall turnover and enzymes

Primary cell walls control the texture of fruit tissues. Although strong enough to withstand turgor pressure, walls are dynamic structures in which the polymers can be remodelled or degraded, resulting in wall loosening. Many enzymes and expansins have been described that act on cell-wall polymers, and the expression of these proteins has been correlated with fruit softening as well as cell expansion and abscission (reviewed by Franková and Fry, 2013). For example, glycanases and transglycanases cleave cell wall polysaccharides in mid-chain (Taylor et al., 1993; Bewley, 1997; Lazan et al., 2004; Fry et al., 2008; Schröder et al., 2009; Franková and Fry, 2011; Derba-Maceluch et al., 2014), glycosidases release mono- or disaccharides from non-reducing termini (Fanutti et al., 1991; de Veau et al. 1993; Hrmová et al., 1998; de Alcântara et al., 2006; Franková and Fry, 2012), and expansins interfere in polysaccharide–polysaccharide hydrogen bonding (Cosgrove, 2000; Harada et al., 2011; Sasayama et al., 2011).

Several polymer-hydrolysing enzymes have been studied in relation to fruit softening, with tomato as the most extensively studied system (Matas et al., 2009; reviewed by Fry, 2017). Several wall polysaccharide-modifying enzyme activities increase, especially endo-polygalacturonase (endo-PG), cellulase, xyloglucan endotransglucosylase, β-galactosidase, pectin-methylesterase and pectate lyase. Although the link between wall-hydrolysing enzymes and fruit softening seems intuitive, tests of this as a functional relationship have often yielded contradictory evidence. A major focus has been endo-PG in tomato. This enzyme is abundant in ripe tomato fruit (Tucker and Grierson, 1982), and suppression of its expression resulted in reduced depolymerization of pectin (Smith et al., 1990). Also, expression of endo-PG in the rin (ripening inhibitor) mutant caused an increased degradation of fruit pectins (Giovannoni et al., 1989). However, both these studies failed to show a related change in tomato fruit softening; no inhibition of softening was observed in endo-PG antisense fruit, and no effect on softening was induced by the expression of endo-PG in the rin mutant. Moreover, other fruits, e.g. strawberry (Pose et al., 2013), persimmon (Cutillas-Iturralde et al., 1993) and kiwifruit (Redgwell et al., 1991), show extensive pectin solubilization and/or a decrease in molecular weight even though they possess very low levels of endo-PG (e.g. Nogata et al., 1993). These observations reinforce the idea that endo-PG is not necessary for fruit softening. The proposed relationship between pectin depolymerization and fruit softening was thus not strongly supported by data, although the excessive softening associated with over-ripening can be prevented by knocking out endo-PG (in the ‘Flavr Savr’ tomato; reviewed by Krieger et al., 2008). Ripening is a robust phenomenon: knocking out any individual player (e.g. endo-PG) often fails to prevent normal softening.

•OH cleaves polysaccharides in vitro

In addition to proteins that remodel the wall, the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (•OH) can cause polysaccharide chain scission non-enzymically. This phenomenon is readily demonstrated in solutions of purified cell wall polysaccharides upon treatment with ascorbate in the presence of O2 plus traces of Cu2+ or Fe3+ (Fry, 1998; Yamazaki et al., 2003; Schweikert et al., 2000, 2002) and in food-related systems (Fauré et al., 2012; Mäkinen et al., 2012; Iurlaro et al., 2014).

•OH can also cleave insoluble polysaccharides that are present in situ as structural components of the cell wall: for example, when •OH was generated within the cell walls of a frozen/thawed maize coleoptile that was being held under tension, the coleoptile extended in a fashion similar to that induced by certain wall-acting proteins or in response to in-vivo auxin treatment (Schopfer, 2002). Likewise, in-vitro •OH treatment of fruit cell walls of tomato (Dumville and Fry, 2003), banana (Cheng et al., 2008b) and longan (Duan et al., 2011) promoted pectin solubilization and depolymerization.

Proposed beneficial roles of •OH

These results indicate that •OH, if formed in the cell wall in vivo, could potentially cleave polysaccharides and thereby exert physiological effects. Indeed, it has been suggested that wall loosening induced by ROS (especially •OH) contributes to fruit ripening (Brennan and Frenkel, 1977; Fry, 1998; Fry et al., 2001; Dumville and Fry, 2003; Cheng et al., 2008a; Yang et al., 2008; Duan et al., 2011), germination (Müller et al., 2009), cell expansion (Schopfer, 2001, 2002; Rodríguez et al., 2002; Liszkay et al., 2004) and abscission (Sakamoto et al., 2008; Cohen et al., 2014). It is sometimes asserted that •OH, as a highly reactive ROS, must be biologically detrimental – for example causing mutations, membrane damage and protein denaturation – and that it would be advantageous for cells to prevent •OH formation or to scavenge it. However, the half-life of •OH within a cellular environment such as a cell wall is estimated at approx. 1 ns, allowing it to diffuse no more than approx. 1 nm (the length of two glucose residues in a cellulose chain) before reacting with some organic molecule (Griffiths and Lunec, 1996): a very short distance in the context of a primary cell wall, which is typically >80 nm thick. Therefore, if produced at an appropriate site (within the cell wall matrix or middle lamella), •OH may have little effect on the protoplast. Moreover, in the case of a softening fruit pericarp, the cells involved are shortly destined to die in an animal’s gut, fulfilling their role in promoting seed dispersal. Therefore, any cellular damage caused to the ripe pericarp by •OH is irrelevant; likewise in other short-lived tissues such as a lysing abscission zone or a rapidly expanding coleoptile.

How could apoplastic •OH be made in vivo?

The production of •OH in plant cell walls most probably involves a Fenton-like reaction, whereby a transition metal ion in the reduced state reacts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2):

Two proposals have been considered: (1) the transition metal is the Fe of the haem group in peroxidase, which can be reduced by superoxide in a Haber–Weiss cycle (Chen and Schopfer, 1999; Liszkay et al., 2003); and (2) a wall-bound transition metal (Cu and/or Fe) ion is reduced by apoplastic electron donors such as ascorbate (Fry, 1998; Vreeburg and Fry, 2005; Green and Fry, 2005; Kärkönen and Fry, 2006; Lindsay and Fry, 2007; Padu et al., 2005). The H2O2 may be generated by wall-bound oxidases (Lane et al., 1993; Asthir et al., 2002; Kärkönen et al., 2009) or superoxide dismutase (Yim et al., 1990; Ogawa et al., 1996; Kukavica et al., 2009), or by non-enzymic reduction of O2 by ascorbate (Fry, 1998). Indeed, Dumville and Fry (2003) showed that the ability of cells in a tomato fruit to secrete ascorbate, and also the tissue’s Cu content, increased during ripening: effects that would be expected to favour in-vivo •OH production.

Is apoplastic •OH made in vivo?

Cheng et al. (2008a) showed that, when homogenates of frozen banana pulp harvested at different stages of ripening were incubated for 12 h in phosphate buffer containing deoxyribose, in-situ generated •OH (detected by its ability to oxidize the deoxyribose to dialdehyde products) increased in parallel with softening, suggesting that ripening may be associated with •OH production in banana. Yang et al. (2008), who applied a similar method but with a shorter incubation period, also suggested that •OH production increases prior to the initiation of banana fruit softening. However, in both these studies, the source of the •OH in pulp was not clear and it could have been an artefact due to the homogenization, not reflecting reactions that occur in vivo.

•OH can cleave wall polysaccharides in vitro, but the question of whether •OH is produced in the apoplast of living tissue and actually acts in vivo on wall polysaccharides in the manner proposed is still open, a major challenge being to detect such a short-lived free radical as •OH in the walls of living cells. There are two possible experimental approaches: (1) infiltration into the apoplast of a membrane-impermeant ‘reporter’ compound that reacts with •OH to give recognizable products (Kuchitsu et al., 1995; Fry et al., 2002; Schopfer et al., 2002; Miller and Fry, 2004; Müller et al., 2009; for a review, see Vreeburg and Fry, 2005); and (2) detection of the ‘collateral damage’ done to wall polysaccharides in vivo when attacked by apoplastic •OH.

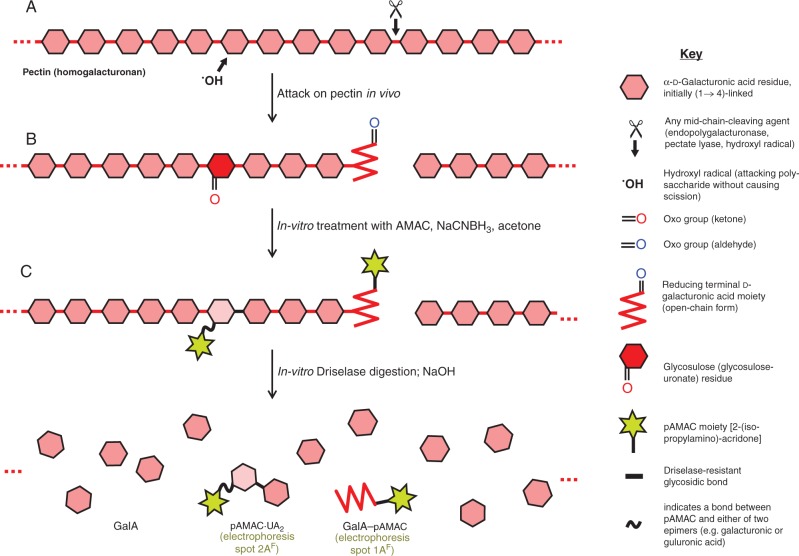

The second approach is based on the fact that the •OH radical cleaves polysaccharides by rather indiscriminate oxidative reactions. •OH-driven polysaccharide scission, proposed to contribute to fruit softening, is accompanied by concurrent reactions that introduce relatively stable oxo groups into the polysaccharide (‘collateral damage’; Fig. 1A) without necessarily cleaving it (Zegota and von Sonntag, 1977; von Sonntag 1980; Vreeburg and Fry, 2005; Vreeburg et al., 2014). Such oxo groups can serve as a chemical ‘fingerprint’ revealing recent •OH attack in the cell walls of living cells. A polysaccharide usually has only a single oxo group (its reducing terminus), but •OH attack generates oxo groups in mid-chain sugar residues, converting them to glycosulose residues (Vreeburg et al., 2014). The proportion of such glycosulose residues (non-terminal oxo groups) per 1000 sugar residues would be a valuable measure of the extent of •OH attack in vivo. Two methods are currently available for their detection:

Fig. 1.

Schematic view of in-vivo attack on pectins and strategies used to detect it. (A) Part of a pectin (homogalacturonan) chain in the wall of a living fruit cell may be attacked either non-enzymically by a hydroxyl radical (•OH) or enzymically by endo-polygalacturonase or pectate lyase. Any of these three agents can cleave the backbone (e.g. at ✂), creating a new reducing terminus (shown in its non-cyclic form, and thus possessing an oxo group). In addition, •OH can non-enzymically abstract an H atom (e.g. from C-2 or C-3 of a GalA residue) without causing chain scission; in an aerobic environment, this initial reaction leads to the formation of a relatively stable glycosulose residue possessing a mid-chain oxo group. (B) Wall material (AIR) is treated in vitro with AMAC, NaCNBH3 and acetone; oxo groups are reductively aminated to form yellow–green-fluorescing pAMAC conjugates. (C) The pAMAC-labelled homogalacturonan is then digested with Driselase, which hydrolyses all glycosidic bonds except any whose sugar residue carries a pAMAC group. The products tend to lactonize and are therefore briefly de-lactonized with NaOH before being fractionated. Further details of the reactions are given in figs 1 and 2 of Vreeburg et al. (2014).

Radiolabelling to detect glycosulose residues.

We have used reductive tritiation with NaB3H4 to detect oxo group formation in Fenton-treated soluble polysaccharides in vitro and in presumptively •OH-exposed cell walls in vivo in ripening pears, germinating cress seeds and elongating maize coleoptiles (Fry et al., 2001, 2002; Miller and Fry, 2001; Müller et al., 2009; Iurlaro et al., 2014). In this approach, each mid-chain glycosulose residue, formed by •OH action, is reduced to yield a tritium-labelled simple sugar (aldose) residue – in some cases an aldose that does not frequently occur naturally. For example, •OH attack at carbon-3 of a xylose residue in xyloglucan will introduce an oxo group which, when treated with NaB3H4 and then acid-hydrolysed, yields a mixture of [3H]xylose and [3H]ribose (the 3-epimer of xylose); the latter is not a natural constituent of xyloglucan and is therefore a highly diagnostic fingerprint (Miller and Fry, 2001).

Fluorescent labelling to detect glycosulose residues.

As an alternative to radiolabelling, we recently developed a method for fluorescently labelling mid-chain (•OH generated) oxo groups present in polysaccharides by reductive amination with 2-aminoacridone (AMAC) plus NaCNBH3, followed by N-isopropylation, to introduce fluorescent 2-isopropylaminoacridone (pAMAC) groups into the polysaccharide (Fig. 1B). The method was developed by model experiments on soluble pectic polysaccharides in vitro (Vreeburg et al., 2014). Upon subsequent Driselase digestion (Fig. 1C), the mid-chain glycosulose residues, indicative of recent •OH attack, were released as various products, of particular diagnostic value being pAMAC·disaccharide conjugates. [Note on nomenclature: The designation ‘sugar–pAMAC’ implies that the pAMAC group is linked to the former reducing group (carbon-1 in the case of an aldose) of the sugar, whereas ‘pAMAC·sugar’ indicates that the pAMAC group is attached to a different carbon of the sugar, whose C-1 remains unlabelled.] In contrast, the single reducing terminal oxo group of a poly- or oligosaccharide was released as a monosaccharide–pAMAC product. We now report the application of the pAMAC/Driselase method to demonstrate the changing abundance of •OH-attacked polysaccharides in the cell walls of various contrasting fruits during ripening to give an indication of the involvement of hydroxyl radical attack in fruit softening.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

2-Aminoacridone was from Fluka (Dorset, UK). Driselase, from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK), was purified by ammonium sulphate precipitation and gel-permeation chromatography (Fry, 2000). The Luna C18 high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) column [250 × 4·6 mm, 5 μm C18(2) 100 Å] was from Phenomenex (Cheshire, UK). The HPLC eluents were from VWR (Leicestershire, UK) or Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, UK). All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Chemicals. The PCE-PTR 200 penetrometer was from PCE Instruments UK Ltd (Southampton, UK).

Pear (Pyrus communis L.), mango (Mangifera indica L.), banana (hybrid based on Musa acuminata Colla), apple (Malus pumila Mill.), avocado (Persea americana Mill.), plum (Prunus domestica L.) and nectarine [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] were from Sainsbury’s supermarket, Edinburgh; in each case, hard fruit not yet ready for eating were selected. Strawberry [Fragaria × ananassa (Weston) Duchesne ex Rosier (pro sp.)] was from Belhaven Fruit Farm, Dunbar, UK, and strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) berries were generously provided by Sheffield Botanical Garden, UK. Fragaria and Arbutus fruit at three stages of ripening, distinguished by colour, were picked on the same day.

Preparation of authentic sugar–pAMAC markers

Fluorescent markers for high-voltage paper electrophoresis (HVPE) and HPLC were prepared as before (Vreeburg et al., 2014). In brief, a reducing sugar (0·4 μmol of dry glucose, GalA, GalA2, GalA3 or GalA4) was suspended in 40 μL of 0·1 m AMAC in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO)/acetic acid/pyridine (17:2:1, by vol.) followed immediately by 40 μL of fresh aqueous 1 m NaCNBH3. After incubation of the mixture at 20 °C for 16 h, 2 μL of acetone and 40 μL of fresh 1 m NaCNBH3 were added and the mixture was incubated for another 1 h at 20 °C. The mixture was diluted with 5 vols of H2O and centrifuged (14 000 rpm, 10 min). The sugar–pAMAC product in the supernatant was purified on a C18 cartridge.

Characterization of fruit softening and preparation of fruit AIR

Except for strawberry and Arbutus, freshly purchased hard fruits were stored in the dark in a wooden cupboard at room temperature in the laboratory. On selected days after purchase (when the fruits were hard, medium and soft, respectively), firmness was measured.

For firmness measurements, three individual fruit from each stage were randomly selected. Except with strawberry, the ‘skin’ was peeled. A 6 mm diameter penetrometer probe was positioned perpendicular to the peeled fruit surface, and the sensor was pressed down until it penetrated to the sensor’s indicator mark; the force shown on the display (in Newtons) was recorded.

A portion (10 g f. wt) of the edible part of each fruit was diced with a razor blade, immediately frozen with liquid N2 in a mortar, and ground to a fine powder with a pestle. Pre-cooled extractant (50 mL; ethanol/pyridine/acetic acid/water, 75:2:2:21 by vol., containing 10 mm Na2S2O3 to prevent Cu- or Fe-dependent •OH production by Fenton reactions; Fry, 1998) was added and the mixture was ground again in the mortar for another 5 min. Finally, the whole homogenate was dispensed as 50 aliquots (each approx. 1·1–1·2 mL, equivalent to 200 mg f. wt of fruit tissue), which were stored at –80 °C.

Arbutus berries at different stages of ripening (orange, red and red–black) were immediately frozen at –80 °C and later homogenized as described above.

pAMAC labelling of fruit AIR

All AMAC work was done under subdued red light; ice-cold solvents were used for the washing and precipitation steps. A portion of fruit AIR (alcohol-insoluble residue) suspension (≡200 mg fresh fruit tissue) was thawed and centrifuged. The pellet was washed twice with 75 % ethanol, blotted to remove free ethanol, and resuspended in 261 μL of a mixture comprising 45 μL of 0·5 % aqueous chlorobutanol, 5 μL of pyridine/acetic acid/water (2:2:1 by vol.; final pH approx. 4·0), 89 μL of DMSO containing 8·9 μmol AMAC and 61 μL of water containing 122 μmol freshly dissolved NaCNBH3; and the mixture was left for 20 h at 20 °C. Acetone (136 μmol) and an additional 122 μmol of fresh NaCNBH3 (61 μL of a 2 m aqueous solution) were added and the incubation was repeated for 16 h at 20 °C. To remove low molecular weight reagents and by-products, we added 1 mL of 96 % ethanol (to precipitate any water-soluble polysaccharides), pelleted the total polymers (at 12 000 g for 5 min), and washed the pellet twice with 1 mL of 75 % ethanol. The pellet was then re-suspended by shaking in 250 μL of pyridine/acetic acid/water (1:1:98 by vol.) for 10 min at 20 °C. The treatments with 96 and 75 % ethanol were repeated, and the final ethanolic pellet of pAMAC-labelled AIR was blotted to semi-dryness.

Driselase digestion

The blotted pellet of pAMAC-labelled AIR was de-lactonized with 100 μL of 0·5 m NaOH (50 μmol) for 5 h at 20 °C, then buffered to pH 4·7 with two molar equivalents (5·75 μL) of acetic acid, washed with ice-cold 80 % ethanol, pelleted at 12 000 g for 5 min, blotted with filter paper and immediately treated with Driselase. [The de-lactonization step facilitated subsequent Driselase digestion.] The blotted, de-lactonized pellet of pAMAC-labelled AIR (equivalent to 200 mg of fresh weight fruit) was digested in 500 μL of 1 % partially purified Driselase in pyridine/acetic acid/0·5 % chlorobutanol, 1:1:98, by vol.) at 37 °C for 14 d, after which the solution was frozen at –20 °C.

Purification of pAMAC-labelled products on a C18 column

A C18-silica cartridge (500 mg Supelco column; Sigma-Aldrich) was pre-conditioned with 2 vols of methanol then 2 vols of H2O. The soluble components of a whole Driselase digest (approx. 500 μL) were then loaded and the column was washed with 2 × 2 mL of H2O, after which bound solutes were eluted with 2 × 2 mL each of 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 % (v/v) methanol. Each fraction was dried, redissolved in 50 μL of pyridine/acetic acid/water (1:1:98, by vol., pH approx. 4·7, containing 0·5 % chlorobutanol), and stored at –20 °C. Fractions exhibiting the characteristic yellow–green fluorescence of pAMAC groups were pooled for further analysis. Immediately before analysis by HVPE or HPLC, a portion was dried, de-lactonized in dilute NaOH (pH >11) at 20 °C for 10 min, and neutralized with acetic acid.

High-voltage paper electrophoresis

Electrophoresis was conducted on Whatman No. 1 or No. 3 paper in a pH 6.5 buffer (pyridine/acetic acid/water, 33:1:300 by vol.) at 4·0 kV for 45–50 min. The papers were cooled with toluene. Methods and apparatus are described by Fry (2011b). After electrophoresis, the papers were dried and viewed under a 254 nm UV lamp and fluorescence was recorded photographically (Camlab DocIt system with LabWorks 4·6 software). Fluorescent spots on paper electrophoretograms were quantified with Image J (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) as described in the Supplementary Data Fig. S3.

High-pressure liquid chromatography

The HPLC was conducted with a solvent flow rate of 1 mL min–1 at room temperature on a Luna C18 silica column with solvent A (500 mm acetic acid, adjusted to pH 5·0 with NaOH) and acetonitrile. All solvent compositions are given as percentage acetonitrile in solvent A, by vol. The column was pre-equilibrated for 30 min with 10 % acetonitrile. The injected sample (20 μL) was eluted with: 0–5 min, 10 % acetonitrile, isocratic; 5–15 min: 10–12·5 % acetonitrile, linear gradient; 15–30 min: 12·5 % acetonitrile, isocratic; 30–35 min, 12·5–15 % acetonitrile, linear gradient; 35–40 min, 15 % acetonitrile, isocratic; 40–50 min, 15–25% acetonitrile, linear gradient; 50–60 min, 25–10 % acetonitrile, linear gradient; 60–65 min, 10 % acetonitrile, isocratic. A fluorescence detector (RF 2000, Dionex) used excitation and emission wavelengths of 442 and 520 nm, respectively.

RESULTS

Application of pAMAC labelling to ripening fruit

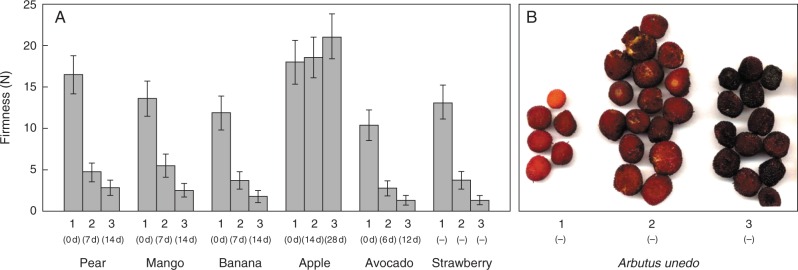

Fruit firmness at three empirically defined stages of softening (hard, medium and soft) was measured – in most cases with a penetrometer (Fig. 2). The apples did not soften perceptibly within 1 month. All other species softened considerably between the three stages selected, although we did not quantify this for Arbutus.

Fig. 2.

Softening of fruits at three stages of ripening. (A) Firmness data were obtained by penetrometer at three stages of ripening (1–3). Values are means (n = 3) ± s.e. Stages of softening were at various days after purchase as stated in parentheses. Strawberry and Arbutus fruit were chosen based on their colour, the different stages being picked on the same day. (B) No firmness readings for the Arbutus berries are available as they were frozen immediately after picking; their appearance is illustrated here.

Our approach for detecting •OH attack on fruit cell walls at different stages of softening in vivo was based on the methodology developed for characterizing authentic •OH-treated polysaccharides in vitro (Vreeburg et al., 2014). AIR (cell wall-rich material) of unripe and ripe fruits was labelled with pAMAC, then exhaustively digested with Driselase. Fluorescent conjugates of negatively charged (mainly pectic) cell wall fragments, such as pAMAC·UA2 (dimer), would be strong evidence for •OH-attacked pectins (Fig. 1). In contrast, GalA–pAMAC (monomer) would be derived from the pectins’ reducing terminus, and could be generated by any of three proposed agents (Fig. 1).

Analysis of total Driselase digestion products of pAMAC-labelled fruit cell walls

Electrophoresis.

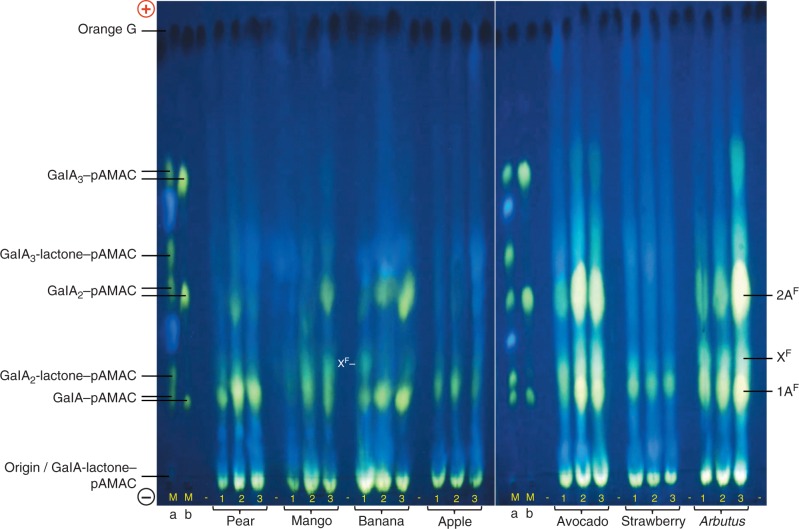

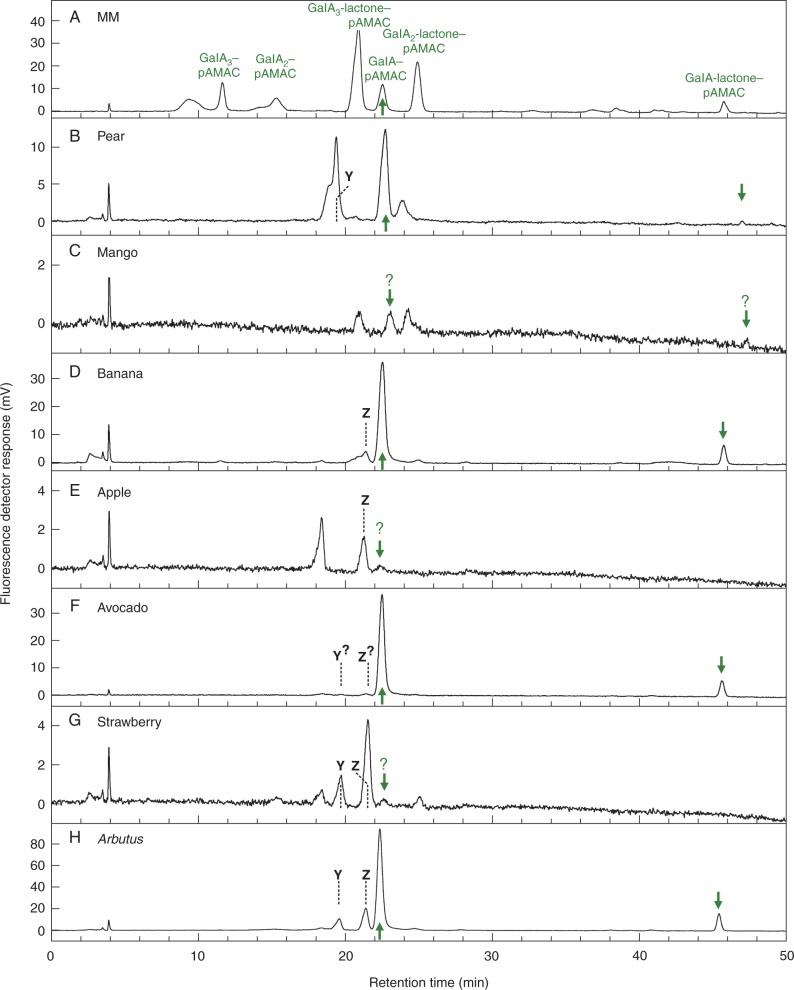

Electrophoresis of the Driselase digestion products of pAMAC-labelled AIR (after de-lactonization) revealed at least two interesting, yellow–green-fluorescing, negatively charged spots (Fig. 3): 1AF, co-migrating with the labelled monomer GalA–pAMAC; and 2AF, approximately co-migrating with the labelled dimer GalA2–pAMAC. The anionic nature of 1AF and 2AF indicates that they were based on Driselase-digestible acidic sugar residues of the fruit cell walls, likely to be mainly GalA. Smaller amounts of putative acidic trimers were sometimes also observed, e.g. in avocado and Arbutus. An additional spot (XF), which fluoresced a less yellowish green, was seen in some species, especially in unripe banana.

Fig. 3.

HVPE resolution of total Driselase digests of pAMAC-labelled AIR samples from seven fruit species. Fruit AIRs, each harvested at three stages of ripening (1–3; see Fig. 2), were successively treated with AMAC, acetone and Driselase (14 d); the pAMAC-labelled oligosaccharides generated were partially purified on a Supelco C18 cartridge column and de-lactonized in NaOH before electrophoresis. Each electrophoretogram loading was the products obtained from 20 mg f. wt of fruit tissue. Markers Ma and Mb are identical mixtures of acidic sugar–pAMAC conjugates before and after de-lactonization. Electrophoresis was at pH 6·5 and 4·0 kV for 45 min on Whatman No. 1 paper. Fluorescent spots were photographed under a 254-nm UV lamp. Orange G, loaded as a tracker between each fruit sample, shows up as a dark spot under UV. (+), anode; (–), cathode; –, blank loading.

In addition, strongly yellow–green-fluorescing neutral spots were present in all species; these spots could be based on any neutral, Driselase-releasable cell wall sugar residues. They showed no obvious changes in intensity throughout ripening.

Confirmatory replicate and additional studies, based on essentially the same technique as used for Fig. 3, are shown in Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S2.

Despite the approximate co-electrophoresis of 2AF with GalA2–pAMAC, spot 2AF cannot have contained GalA2–pAMAC itself since this compound is completely digested by Driselase under the conditions used. Instead, it is likely to have a constitution of the type pAMAC·UA-GalA (Fig. 1), a Driselase-resistant ‘fingerprint’ spot diagnostic of •OH attack (Vreeburg et al., 2014).

In pear, mango, banana, avocado and Arbutus, spot 1AF appreciably increased in intensity (Fig. 3; Table 1), especially when stage 3 and stage 2 (soft and medium soft fruits) are compared with stage 1 (hard fruit). It also increased during softening in plum and nectarine (Table 1; Supplementary Data Fig. S1). On the other hand, the apple and strawberry AIR samples did not show any clear evidence of an increase in 1AF at any stage.

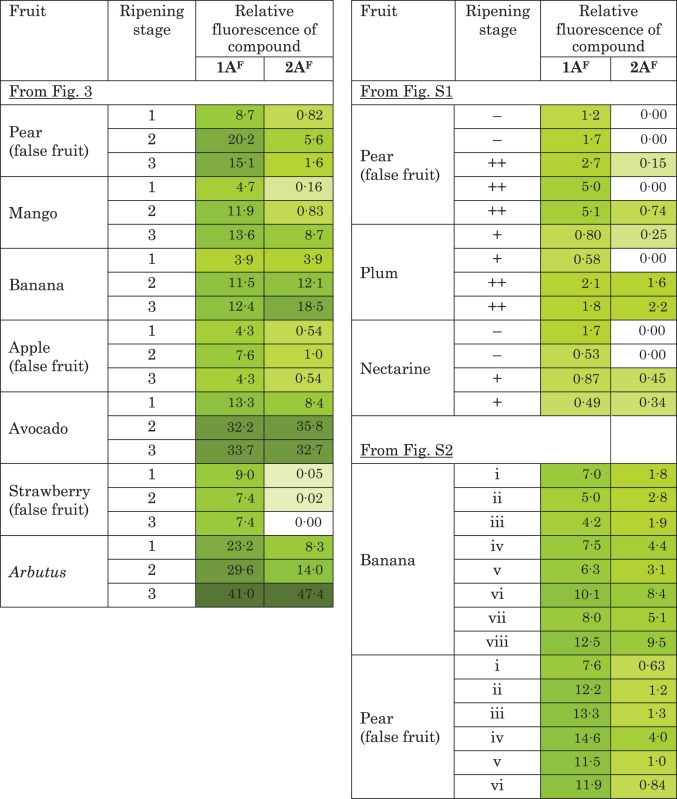

Table 1.

Relative abundance of the two major pAMAC-labelled anionic cell wall products at different stages of fruit softening

|

Intensities were quantified on the electrophoretograms of de-lactonized samples as shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S2.

Relative fluorescence is quoted in arbitrary units of area, as quantified in ImageJ by the method illustrated in Fig. S3.

The putative ‘fingerprint’ spot, 2AF, was detected in all species, but was very weak in apple and strawberry. The yield of 2AF increased during softening in mango, banana, avocado, Arbutus, plum and nectarine, and was always much fainter in hard, unripe fruit (Fig. 3; Table 1; Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S2). In pear, it was detected only at stage 2. The transient appearance of 2AF in pear was confirmed in one repeat experiment (Fig. S2); it is possible that a brief period of high 2AF yield was missed in an additional experiment (Fig. S1).

Some samples, e.g. of pear and mango, revealed a weak spot that approximately co-migrated with GalA3-lactone–pAMAC (Fig. 3); however, HPLC showed that this specific compound was absent (Fig. 4; see below), as expected because it is Driselase digestible.

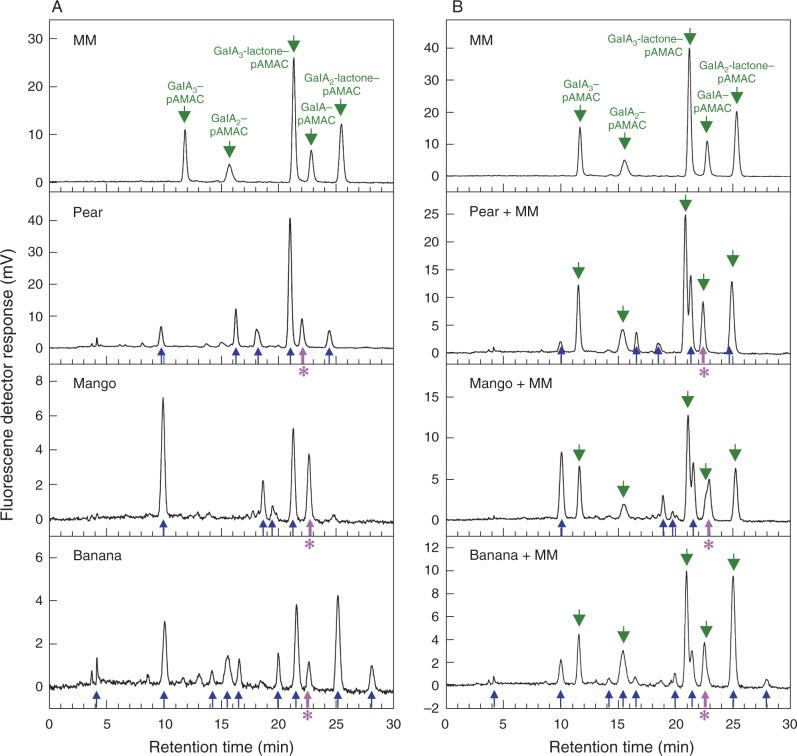

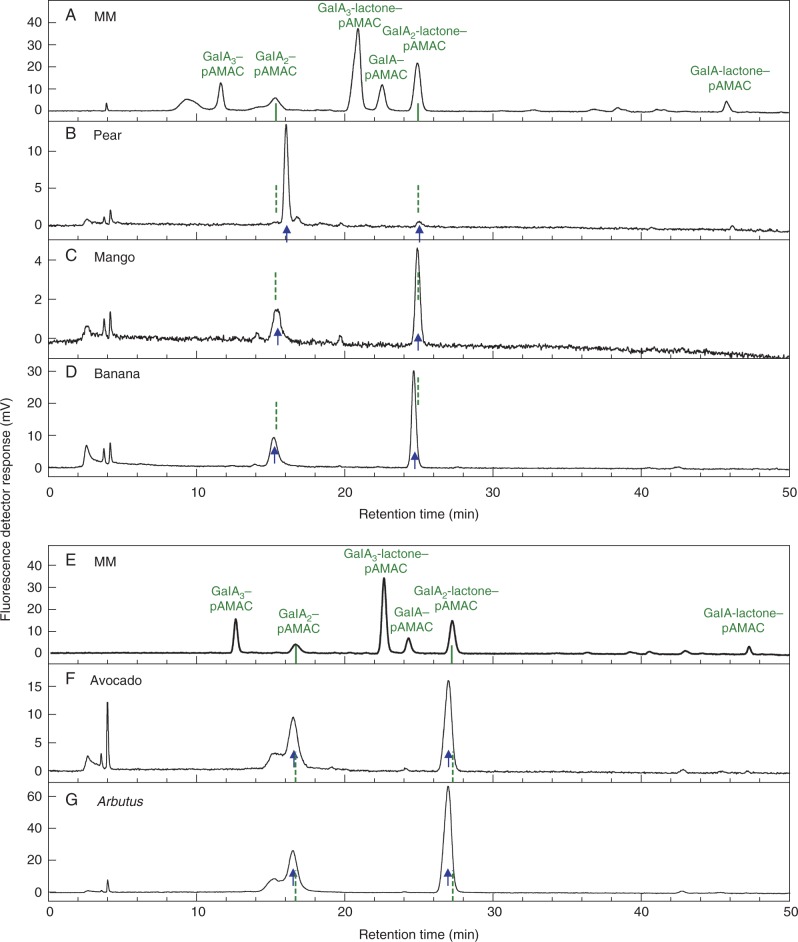

Fig. 4.

HPLC of total Driselase digests of pAMAC-labelled cell walls from three fruit species. AIRs from pear, mango and banana fruit (stages 3, 1 and 1, respectively) were treated with AMAC, acetone, Driselase, Supelco C18 and NaOH, all as in Fig. 3. Total fluorescent products (which will include conjugates of both neutral and acidic carbohydrates) were analysed by HPLC (A) before and (B) after addition of a marker mixture containing acidic sugar–pAMAC conjugates. Fluorescence detection was with excitation at 442 nm and emission at 520 nm. MM, marker mixture containing authentic acidic sugar–pAMAC conjugates. Green arrows, authentic sugar–pAMACs (including those added as a ‘spike’); blue arrows, unidentified peaks from fruit cell wall digests; thick purple arrows with asterisk, putative GalA–pAMAC from fruit cell wall digests.

HPLC.

The presence of the reducing-end-labelled monomer, GalA–pAMAC, in the digests was supported by HPLC, which we performed on representative pear, mango and banana digests (stages 3, 1 and 1, respectively; without de-lactonization) both before and after spiking with a mixture of authentic sugar–pAMACs (Fig. 4). About 5–9 fluorescent peaks were detected by HPLC, with some differences between fruit species. In pear and banana, a compound was found (Fig. 4, thick purple arrow) which co-eluted with an internal marker of authentic GalA–pAMAC, supporting the idea that this was its identity. In mango, GalA–pAMAC partially overlapped with a compound of similar retention time (Fig. 4), which remains unidentified. Thus, in these fruit species, GalA–pAMAC was present, accounting for the 1AF spot seen on electrophoretograms.

Concerning the labelled acidic dimers, HPLC of the pear and mango samples gave no peak exactly co-eluting with authentic internal marker GalA2–pAMAC. The pear sample gave a peak that eluted 1·2 min later than this marker. A small unidentified peak that did approximately co-elute with GalA2–pAMAC was found in the banana digest; however, this cannot have been GalA2–pAMAC itself because this substance is completely digested by Driselase under the conditions used (Vreeburg et al., 2014).

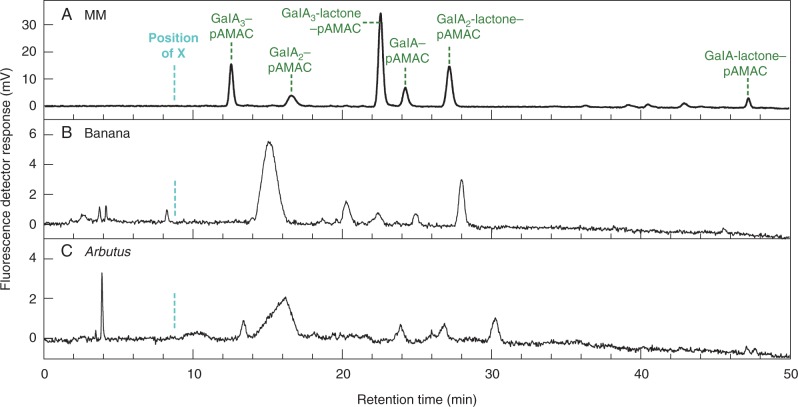

Further characterization of individual fluorescent spots by HPLC

Samples of the material in the 1AF zone were eluted from electrophoretograms and submitted to HPLC analysis, typically giving 2–4 peaks (Fig. 5). In at least four fruits (pear, banana, avocado and Arbutus), a major peak co-eluting with GalA–pAMAC was again detected, whereas in mango, apple and strawberry (the three species which showed the faintest 1AF spots on the electrophoretogram), the corresponding peak was extremely minor. A small peak of GalA-lactone–pAMAC accompanied the GalA–pAMAC in pear, banana, avocado and Arbutus, supporting its identity since lactonization/de-lactonization is reversible and would be expected to occur between the electrophoresis step and the HPLC. Spot 1AF from the electrophoretogram yielded in addition HPLC peaks other than GalA-lactone–pAMAC and GalA–pAMAC (Fig. 5), with some differences between fruit species. In particular, unidentified peaks Y and Z (see Fig. 5) were observed: Y in pear, Z in banana and apple, and both in Arbutus, strawberry and possibly avocado.

Fig. 5.

HPLC of the acidic monomer (1AF) spots from Driselase-digested pAMAC-labelled cell walls of seven fruit species. Each 1AF spot (pooled for all three stages of development for each fruit; de-lactonized) shown in Fig. 3 was eluted from the electrophoretogram and analysed by HPLC. MM, marker mixture containing authentic acidic sugar–pAMAC conjugates. Arrows, putative GalA–pAMAC (and its lactone, which partially re-formed during elution from the electrophoretogram) from fruit cell wall digests. Dashed lines, compounds Y and Z, discussed in the text.

Spot 2AF, deduced to be pAMAC·UA-GalA, which co-electrophoresed with authentic GalA2–pAMAC but was Driselase-stable, yielded HPLC peaks that only approximately co-eluted with authentic GalA2–pAMAC and GalA2-lactone–pAMAC in all species tested (Fig. 6). Both the acidic and lactone forms of the proposed pAMAC·UA-GalA were present in these eluates because of their interconversion, which is more rapid than in the case of the GalA2–pAMAC ↔ GalA2-lactone–pAMAC interconversion (Vreeburg et al., 2014).

Fig. 6.

HPLC of the acidic dimer (2AF) spots from Driselase-digested pAMAC-labelled cell walls of five fruit species. 2AF spots were eluted from a paper electrophoretogram (similar to that shown in Fig. 3 but derived from non-de-lactonized samples; all three ripening stages combined) and analysed by HPLC. MM, marker mixture containing authentic acidic sugar–pAMAC conjugates. Arrows, the proposed fingerprints for •OH attack: pAMAC·UA-GalA and its lactone (rapidly re-formed during elution from the electrophoretogram) from fruit cell wall digests. Dashed lines, predicted position of authentic GalA2–pAMAC and GalA2-lactone–pAMAC, deduced from the marker run. The samples in the upper and lower graphs were run on different days, accounting for the slight discrepancy in marker retention times. Strawberry and apple were not included because they did not show any appreciable 2AF spot in Fig. 3.

Electrophoretogram spot XF, a greenish-fluorescing compound migrating slightly faster than authentic GalA2-lactone–pAMAC and observed in banana (and possibly Arbutus), was resolved by HPLC into several small peaks (Fig. 7). These peaks, however, did not match the HPLC peak ‘X’ found after pAMAC labelling of in-vitro •OH-treated pectin (Vreeburg et al., 2014), even though both have similar migration and fluorescence properties on the electrophoretogram. Both X and XF remain to be identified.

Fig. 7.

HPLC of the acidic unknown (XF) spots from Driselase-digested pAMAC-labelled cell walls of banana and Arbutus. The XF spot (similar to that shown in Fig. 3 but from a non-de-lactonized sample) for stage-1 banana and Arbutus was eluted from an electrophoretogram and analysed by HPLC. MM, marker mixture containing authentic acidic sugar–pAMAC conjugates. The cyan dashed line indicates the approximate retention time of unknown ‘X’ (relative to the GalA3–pAMAC peak) seen in the products obtained from in-vitro •OH-treated pectin (Vreeburg et al., 2014). Green dashed lines indicate the authentic markers.

DISCUSSION

A fluorescent fingerprinting method, recently developed for demonstrating hydroxyl radical attack on polysaccharides in vitro (Vreeburg et al., 2014), has now been applied to the cell wall polysaccharides of several fruit species at different stages of softening, providing useful information on •OH attack in vivo. The fluorescent labelling procedure can yield information comparable with a radiolabelling approach used earlier (Fry et al., 2001, 2002; Müller et al., 2009; Iurlaro et al., 2014), and the two approaches are largely interchangeable. However, the fluorescent pAMAC group introduced into the polysaccharides in the new method provides a means of further characterization of these cell wall components by means of a wide variety of accessible chromatography and electrophoresis techniques, including fluorophore-assisted electrophoresis (Goubet et al., 2002). Specifically, pAMAC introduces a pH-dependent charge into the •OH-attacked, plant-derived polymer residue, which facilitates further characterization of the products. Radiolabelling is generally more sensitive and is very straightforward to quantify, but not all laboratories are authorized to use it.

At least two informative fluorescent spots (1AF and 2AF) were visualized on electrophoretograms (Fig. 3). Spot 1AF, including predominantly GalA–pAMAC (Fig. 1), increased in intensity between stages 1 and 3 of softening in most fruits (Table 1). This would correspond to an increasing number of d-GalA reducing termini during fruit ripening, which could be caused by the pectic polysaccharide-cleaving actions of not only •OH (as a result of attack at C-1 or C-4 of homogalacturonan – see fig. 1 of Vreeburg et al., 2014) but also endo-PG and/or pectate lyase. Both endo-PG and pectate lyase, proposed fruit softening agents, can attack a homogalacturonan chain, creating one new reducing terminus per cleavage event and this reducing terminus would become pAMAC labelled. Several studies have reported increases in endo-PG activity (though seldom definitively distinguished from pectate lyase activity) in pear (Pressey and Avants, 1976), banana (Pathak and Sanwall, 1998; Ali et al., 2004) and avocado (Huber and O’Donoghue, 1993). Increasing pectate lyase activity has been measured during ripening in banana (Payasi and Sanwal, 2003; Payasi et al., 2006). In addition, pectate lyase mRNA accumulation was reported in several ripening fruits including banana (Dominquez-Puigjaner et al., 1997; Marín-Rodríguez et al., 2003) and mango (Chourasia et al., 2006). Therefore, spot 1AF obtained from fruit AIR was not exclusive evidence of •OH attack, but may offer a valuable fingerprint indicating the total pectic chain scission occurring in vivo.

Spot 2AF was concluded to be a Driselase limit digestion product of the type pAMAC·UA-GalA (Fig. 1), i.e. a ‘fingerprint’ indicating recent in-vivo mid-chain •OH attack. The precise chemical identity of the compound(s) present in spot 2AF has not been established. 2AF clearly did not include the reducing-terminus-labelled disaccharide, GalA2–pAMAC, since this compound does not withstand 14 d of Driselase treatment (Vreeburg et al., 2014), and GalA2–pAMAC was not observed in pear and mango by HPLC analysis (Fig. 4). It probably includes pAMAC·GalA-GalA and/or its 2-, 3- and 4-epimers (pAMAC·taluronate-GalA, pAMAC·guluronate-GalA and pAMAC·glucuronate-GalA, respectively). We would expect all these structures to be Driselase resistant because the range of activities present in Driselase probably does not include α-taluronidase, α-guluronidase and α-glucuronidase, and because the pAMAC group would block the action of α-galacturonidase.

The intensity of spot 2AF increased appreciably as hard fruit (stage 1) matured into softer fruit (stages 2 and 3) in mango, banana, avocado and Arbutus. The observation in banana may possibly be related to the ripening-dependent increase in the reported ability of banana fruit homogenates to generate ‘endogenous’ •OH post-mortem (Cheng et al., 2008a; Yang et al., 2008). In pear, the increase in spot 2AF was transient, peaking in stage 2; this suggests that the glycosulose residues from which 2AF is generated (Fig. 1) were unstable in vivo. A related observation in pear (increase in 3H-labelled products released when fruit cell walls were NaB3H4 labelled and then Driselase digested) was reported by Fry et al. (2001), where the unidentified 3H-labelled products were proposed to be ‘fingerprints’ of •OH attack.

The increase in yield of 2AF during softening depended on the type of fruit under consideration. In true fruits (those whose edible portion is derived from the ovary wall; including mango, banana, avocado, Arbutus, plum and nectarine), there was an increase in 2AF that correlated with softening. In contrast, it showed little if any increase in apple or strawberry and increased only transiently in pear, which are all false fruits. In false fruits, the edible tissue is derived from the receptacle, not the ovary wall. Therefore, differences in developmental origin of the edible tissue may dictate the mechanism adopted for cell wall modification during ‘fruit’ softening.

Conclusions

It was reported nearly 40 years ago that in pear fruit, endogenous peroxides (and thus potentially also •OH generated from them) correlate with softening (Brennan and Frenkel, 1977). Later it was found that the polysaccharides of softening pears exhibit radiochemical ‘fingerprints’ diagnostic of recent •OH attack (Fry et al., 2001). Furthermore, of two investigated cultivars of muskmelon, the one whose microsomal membranes produced less •OH in vitro had a longer shelf-life (Lacan and Baccou, 1998). Taken together, the available evidence supports the view that fruit softening, often viewed as broadly a ‘hydrolytic’ phenomenon, is at least partly ‘oxidative’ – a suggestion raised by Brennan and Frenkel (1977) but often ignored. We hope that interest in this concept will be revived by the present study and explored in greater depth. Although several of the fluorescent ‘fingerprint’ compounds were not fully identified in the present study and deserve further analysis, our new fluorescent labelling method will provide useful information and can be used in conjunction with other approaches to add to our knowledge and understanding of the occurrence and rate of •OH attack relative to endo-PG and pectate lyase action in fruit cell walls.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org and consist of the following. Figure S1: electrophoretic resolution of total Driselase digests of pAMAC-labelled cell walls from three fruit species. Figure S2: electrophoretic resolution of total Driselase digests of pAMAC-labelled cell walls from banana and pear. Figure S3: method for quantification of fluorescent spots on paper electrophoretograms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mrs Janice Miller and Mr Tim Gregson for excellent technical assistance, and the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council for a grant (ref. 15/D19626) in support of this work. O.B.A. thanks the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia, for a studentship, and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia for a grant to continue the work (ref. GGPM-2013-032).

LITERATURE CITED

- Albersheim P, Darvill A, Roberts K, Sederoff R, Staehelin A. 2010. Plant cell walls. From chemistry to biology. New York: Garland Science. [Google Scholar]

- de Alcântara PH, Martim L, Silva CO, Dietrich SM, Buckeridge MS. 2006. Purification of a β-galactosidase from cotyledons of Hymenaea courbaril L. (Leguminosae). Enzyme properties and biological function. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 44: 619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali ZM, Chin LH, Lazan H. 2004. A comparative study on wall degrading enzymes, pectin modifications and softening during ripening of selected tropical fruits. Plant Science 167: 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Asthir B, Duffus CM, Smith RC, Spoor W. 2002. Diamine oxidase is involved in H2O2 production in the chalazal cells during barley grain filling. Journal of Experimental Botany 53: 677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basanta MF, Ponce NM, Salum ML, et al. 2014. Compositional changes in cell wall polysaccharides from five sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) cultivars during on-tree ripening. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 62: 12418–12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley JD. 1997. Breaking down the walls – a role for endo-β-mannanase in release from seed dormancy? Trends in Plant Science 2: 464–469. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman FF, Parija P. 1928. Analytic studies in plant respiration. I. The respiration of a population of senescent ripening apples. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 103: 412–445. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan T, Frenkel C. 1977. Involvement of hydrogen peroxide in the regulation of senescence in pear. Plant Physiology 59: 411–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SX, Schopfer P. 1999. Hydroxyl-radical production in physiological reactions – a novel function of peroxidase. European Journal of Biochemistry 260: 726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng GP, Duan XW, Yang B, et al. 2008a. Effect of hydroxyl radical on the scission of cellular wall polysaccharides in vitro of banana fruit at various ripening stages. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 30: 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng GP, Duan XW, Shi J, Lu WJ, Luo YB, Jiang WB. 2008b. Effects of reactive oxygen species on cellular wall disassembly of banana fruit during ripening. Food Chemistry 109: 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chourasia A, Sane VA, Nath P. 2006. Differential expression of pectate lyase during ethylene-induced postharvest softening of mango (Mangifera indica var. Dashehari). Plant Physiology 128: 546–555. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MF, Gurung S, Fukuto JM, Yamasaki H. 2014. Controlled free radical attack in the apoplast: a hypothesis for roles of O, N and S species in regulatory and polysaccharide cleavage events during rapid abscission by Azolla. Plant Science 217: 120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. 2000. Expansive growth of plant cell walls. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 38: 109–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutillas-Iturralde A, Zarra I, Lorences EP. 1993. Metabolism of cell-wall polysaccharides from persimmon fruit – pectin solubilization during fruit ripening occurs in apparent absence of polygalacturonase activity. Physiologia Plantarum 89: 369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Derba-Maceluch M, Awano T, Takahashi J, et al. 2014. Suppression of xylan endotransglycosylase PtxtXyn10A affects cellulose microfibril angle in secondary wall in aspen wood. New Phytologist 205: 666–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Puigjaner E, Llop I, Vendrell M, Prat S. 1997. A cDNA clone highly expressed in ripe banana fruit shows homology to pectate lyases. Plant Physiology 114: 1071–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Zhang H, Zhang D, Sheng J, Lin H, Jiang Y. 2011. Role of hydroxyl radical in modification of cell wall polysaccharides and aril breakdown during senescence of harvested longan fruit. Food Chemistry 128: 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumville JC, Fry SC. 2003. Solubilisation of tomato fruit pectins by ascorbate: a possible non-enzymic mechanism of fruit softening. Planta 217: 951–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealing PM. 1994. Lipoxygenase activity in ripening tomato fruit pericarp tissue. Phytochemistry 36: 547–552. [Google Scholar]

- Fanutti C, Gidley MJ, Reid JSG. 1991. A xyloglucan-oligosaccharide-specific α-d-xylosidase or exo-oligoxyloglucan-α-xylohydrolase from germinated nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus L.) seeds – purification, properties and its interaction with a xyloglucan-specific endo-(1→4)-β-d-glucanase and other hydrolases during storage-xyloglucan mobilization. Planta 184: 137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauré AM, Andersen ML, Nyström L. 2012. Ascorbic acid induced degradation of β-glucan: hydroxyl radicals as intermediates studied by spin trapping and electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Carbohydrate Polymers 87: 2160–2168. [Google Scholar]

- Franková L, Fry SC. 2011. Phylogenetic variation in glycosidases and glycanases acting on plant cell wall polysaccharides, and the detection of transglycosidase and trans-β-xylanase activities. The Plant Journal 67: 662–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franková L, Fry SC. 2012. Trans-α-xylosidase and trans-β-galactosidase activities, widespread in plants, modify and stabilise xyloglucan structures. The Plant Journal 71: 45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franková L, Fry SC. 2013. Biochemistry and physiological roles of enzymes that ‘cut and paste’ plant cell-wall polysaccharides (Darwin review). Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 3519–3550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel C, Hartman TG. 2012. Decrease in fruit moisture content heralds and might launch the onset of ripening processes. Journal of Food Science 77: S365–S376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC. 1998. Oxidative scission of plant cell wall polysaccharides by ascorbate-induced hydroxyl radicals. Biochemical Journal 332: 507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC. 2011a. Cell wall polysaccharide composition and covalent crosslinking. Annual Plant Reviews 41: 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC. 2011b. High-voltage paper electrophoresis (HVPE) of cell-wall building blocks and their metabolic precursors. Methods in Molecular Biology 715: 55–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC. 2017. Ripening. In: Encyclopedia of applied plant sciences. Elsevier (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC, Dumville JC, Miller JG. 2001. Fingerprinting of polysaccharides attacked by hydroxyl radicals in vitro and in the cell walls of ripening pear fruit. Biochemical Journal 357: 729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC, Miller JG, Dumville JC. 2002. A proposed role for copper ions in cell wall loosening. Plant and Soil 247: 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC, Mohler KE, Nesselrode BHWA, Franková L. 2008. Mixed-linkage β-glucan: xyloglucan endotransglucosylase, a novel wall-remodelling enzyme from Equisetum (horsetails) and charophytic algae. The Plant Journal 55: 240–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubet F, Jackson P, Deery MJ, Dupree P. 2002. Polysaccharide analysis using carbohydrate gel electrophoresis: a method to study plant cell wall polysaccharides and polysaccharide hydrolases. Analytical Biochemistry 300: 53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MA, Fry SC. 2005. Vitamin C degradation in plant cells via enzymatic hydrolysis of 4-O-oxalyl-l-threonate. Nature 433: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gregorio A, Dugo G, Arena N. 2000. Lipoxygenase activities in ripening olive fruit tissue. Journal of Food Biochemistry 24: 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni JJ, Della Penna D, Bennett AB, Fischer RL. 1989. Expression of a chimeric polygalacturonase gene in transgenic rin (ripening inhibitor) tomato fruit results in polyuronide degradation but not fruit softening. The Plant Cell 1: 53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths HR, Lunec J. 1996. Investigating the effects of oxygen free radicals on carbohydrates in biological systems. In: Punchard NA, Kelly FJ, eds. Free radicals: a practical approach. Oxford: IRL Press, 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Torii Y, Morita S, et al. 2011. Cloning, characterization, and expression of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase and expansin genes associated with petal growth and development during carnation flower opening. Journal of Experimental Botany 62: 815–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrmova M, MacGregor EA, Biely P, Stewart RJ, Fincher GB. 1998. Substrate binding and catalytic mechanism of a barley β-d-glucosidase/(1,4)-β-d-glucan exohydrolase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 273: 11134–11143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber DJ, O’Donoghue EM. 1993. Polyuronides in avocado (Persea americana) and tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) fruits exhibit markedly different patterns of molecular weight downshifts during ripening. Plant Physiology 102: 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iurlaro A, Dalessandro G, Piro G, Miller JG, Fry SC, Lenucci MS. 2014. Evaluation of glycosidic bond cleavage and formation of oxo groups in oxidized barley mixed-linkage β-glucans using tritium labelling. Food Research International 66: 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez A, Creissen G, Kular B, et al. 2002. Changes in oxidative processes and components of the antioxidant system during tomato fruit ripening. Planta 214: 751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärkönen A, Fry SC. 2006. Effect of ascorbate and its oxidation-products on H2O2 production in cell-suspension cultures of Picea abies and in the absence of cells. Journal of Experimental Botany 57: 1633–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärkönen A, Warinowski T, Teeri TH, Simola LK, Fry SC. 2009. On the mechanism of apoplastic H2O2 production during lignin formation and elicitation in cultured spruce cells – peroxidases after elicitation. Planta 230: 553–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger EK, Allen E, Gilbertson LA, Roberts JK, Hiatt W, Sanders RA. 2008. The Flavr Savr tomato, an early example of RNAi technology. Hortscience 43: 962–964 [Google Scholar]

- Kuchitsu K, Kosaka T, Shiga T, Shibuya N. 1995. EPR evidence for generation of hydroxyl radical triggered by N-acetylchitooligosaccharide elicitor and a protein phosphatase inhibitor in suspension-cultured rice cells. Protoplasma 188: 138–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kukavica B, Mojović M, Vučinić Ž, Maksimović V, Takahama U, Jovanović SV. 2009. Generation of hydroxyl radical in isolated pea root cell wall, and the role of cell wall-bound peroxidase, Mn-SOD and phenolics in their production. Plant and Cell Physiology 50: 304–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacan D, Baccou J-C. 1998. High levels of antioxidant enzymes correlate with delayed senescence in nonnetted muskmelon fruits. Planta 204: 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Lane BG, Dunwell JM, Ray JA, Schmitt MR, Cuming AC. 1993. Germin, a protein marker of early plant development, is an oxalate oxidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 268: 12239–12242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazan H, Ng SY, Goh LY, Ali ZM. 2004. Papaya β-galactosidase/galactanase isoforms in differential cell wall hydrolysis and fruit softening during ripening. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 42: 847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay SE, Fry SC. 2007. Redox and wall-restructuring. In: Verbelen J-P, Vissenberg K, eds. The expanding cell. Berlin: Springer, 159–190. [Google Scholar]

- Liszkay A, Kenk B, Schopfer P. 2003. Evidence for the involvement of cell wall peroxidase in the generation of hydroxyl radicals mediating extension growth. Planta 217: 658–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liszkay A, van der Zalm E, Schopfer P. 2004. Production of reactive oxygen intermediates (O2−, H2O2, and OH) by maize roots and their role in wall loosening and elongation growth. Plant Physiology 136: 3114–3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen OE, Kivelä R, Nyström L, Andersen ML, Sontag-Strohm T. 2012. Formation of oxidising species and their role in the viscosity loss of cereal β-glucan extracts. Food Chemistry 132: 2007–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Rodríguez MC, Smith DL, Manning K, Orchard J, Seymour GB. 2003. Pectate lyase gene expression and enzyme activity in ripening banana fruit. Plant Molecular Biology 51: 851–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matas AJ, Gapper NE, Chung M-Y, Giovannoni JJ, Rose JKC. 2009. Biology and genetic engineering of fruit maturation for enhanced quality and shelf-life. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 20: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir S, Philosophhadas S, Zauberman G, Fuchs Y, Akerman M, Aharoni N. 1991. Increased formation of fluorescent lipid-peroxidation products in avocado peels precedes other signs of ripening. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 116: 823–826. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JG, Fry SC. 2001. Characteristics of xyloglucan after attack by hydroxyl radicals. Carbohydrate Research 332: 389–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JG, Fry SC. 2004. N-[3H]Benzoylglycylglycylglycine as a probe for hydroxyl radicals. Analytical Biochemistry 335: 126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K, Linkies A, Vreeburg RAM, Fry SC, Krieger-Liszkay A, Leubner-Metzger G. 2009. In vivo cell wall loosening by hydroxyl radicals during cress seed germination and elongation growth. Plant Physiology 150: 1855–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogata Y, Ohta H, Voragen AGJ. 1993. Polygalacturonase in strawberry fruit. Phytochemistry 34: 617–620. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Kanematsu S, Asada K. 1996. Intra- and extra-cellular localization of ‘cytosolic’ CuZn-superoxide dismutase in spinach leaf and hypocotyl. Plant and Cell Physiology 37: 790–799. [Google Scholar]

- Padu E, Kollist H, Tulva I, Oksanen E, Moldau H. 2005. Components of apoplastic ascorbate use in Betula pendula leaves exposed to CO2 and O3 enrichment. New Phytologist 165: 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak N, Sanwal GG. 1998. Multiple forms of polygalacturonase from banana fruits. Phytochemistry 48: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payasi A, Sanwal GG. 2003. Pectate lyase activity during ripening of banana fruit. Phytochemistry 63: 243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payasi A, Misra PC, Sanwal GG. 2006. Purification and characterization of pectate lyase from banana (Musa acuminata) fruits. Phytochemistry 67: 861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce NMA, Ziegler VH, Stortz CA, Sozzi GO. 2010. Compositional changes in cell wall polysaccharides from Japanese plum (Prunus salicina Lindl.) during growth and on-tree ripening. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 58: 2562–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pose S, Paniagua C, Cifuentes M, Blanco-Portales R, Quesada MA, Mercado JA. 2013. Insights into the effects of polygalacturonase FaPG1 gene silencing on pectin matrix disassembly, enhanced tissue integrity, and firmness in ripe strawberry fruits. Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 3803–3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna V, Yashoda HM, Prabha TN, Tharanathan R. 2003. Pectic polysaccharides during ripening of mango (Mangifera indica L.). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 83: 1182–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Pressey R, Avants JK. 1976. Pear polygalacturonases. Phytochemistry 15: 1349–1351. [Google Scholar]

- Redgwell RJ, Melton LD, Brasch DJ. 1991. Cell-wall polysaccharides of kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa): effect of ripening on the structural features of cell-wall materials. Carbohydrate Research 209: 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez AA, Grunberg KA, Taleisnik EL. 2002. Reactive oxygen species in the elongation zone of maize leaves are necessary for leaf extension. Plant Physiology 129: 1627–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogiers SY, Kumar GNM, Knowles NR. 1998. Maturation and ripening of fruit of Amelanchier alnifolia Nutt. are accompanied by increasing oxidative stress. Annals of Botany 81: 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M, Munemura I, Tomita R, Kobayashi K. 2008. Involvement of hydrogen peroxide in leaf abscission signaling, revealed by analysis with an in vitro abscission system in Capsicum plants. The Plant Journal 56: 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasayama D, Azuma T, Itoh K. 2011. Involvement of cell wall-bound phenolic acids in decrease in cell wall susceptibility to expansins during the cessation of rapid growth in internodes of floating rice. Journal of Plant Physiology 168: 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer P. 2001. Hydroxyl radical-induced cell-wall loosening in vitro and in vivo: implications for the control of elongation growth. The Plant Journal 28: 679–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer P. 2002. Evidence that hydroxyl radicals mediate auxin-induced extension growth. Planta 214: 821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder R, Atkinson RG, Redgwell RJ. 2009. Re-interpreting the role of endo-β-mannanases as mannan endotransglycosylase/hydrolases in the plant cell wall. Annals of Botany 104: 197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweikert C, Liszkay L, Schopfer P. 2000. Scission of polysaccharides by peroxidase-generated hydroxyl radicals. Phytochemistry 53: 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweikert C, Liszkay L, Schopfer P. 2002. Polysaccharide degradation by Fenton reaction- or peroxidase-generated hydroxyl radicals in isolated plant cell walls. Phytochemistry 61: 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJS, Watson CF, Morris PC, et al. 1990. Inheritance and effect on ripening of antisense polygalacturonase genes in transgenic tomatoes. Plant Molecular Biology 14: 369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Sonntag C. 1980. Free radical reactions of carbohydrates as studied by radiation techniques. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry 37: 7–77. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JE, Webb STJ, Coupe SA, Tucker GA, Roberts JA. 1993. Changes in polygalacturonase activity and solubility of polyuronides during ethylene-stimulated leaf abscission in Sambucus nigra. Journal of Experimental Botany 44: 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker GA, Grierson D. 1982. Synthesis of polygalacturonase during tomato fruit ripening. Planta 155: 64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Veau IEJ, Gross KC, Huber DJ, Watada AE. 1993. Degradation and solubilisation of pectin by β-galactosidases purified from avocado mesocarp. Physiologia Plantarum 87: 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Vreeburg RAM, Fry SC. 2005. Reactive oxygen species in cell walls. In: Smirnoff N, ed. Antioxidants and reactive oxygen species in plants. Oxford: Blackwell, 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Vreeburg RAM, Airianah OB, Fry SC. 2014. Fingerprinting of hydroxyl radical-attacked polysaccharides by N-isopropyl 2-aminoacridone labelling. Biochemical Journal 463: 225–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Fukuda K, Matsukawa M, et al. 2003. Reactive oxygen species depolymerize hyaluronan: involvement of the hydroxyl radical. Pathophysiology 9: 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SY, Su XG, Prasad KN, Yang B, Cheng GP, Chen YL. 2008. Oxidation and peroxidation of postharvest banana fruit during softening. Pakistan Journal of Botany 40: 2023–2029. [Google Scholar]

- Yim MB, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. 1990. Copper, zinc superoxide dismutase catalyzes hydroxyl radical production from hydrogen peroxide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 87: 5006–5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegota H, von Sonntag C. 1977. Radiation chemistry of carbohydrates, XV OH Radical induced scission of the glycosidic bond in disaccharides. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung 32b: 1060–1067. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.