A growth-inhibiting protein boosts the action of the defense-related plant hormones salicylic acid and jasmonic acid, rendering rice plants more resistant to pathogen attack.

Abstract

Gibberellins are a class of tetracyclic plant hormones that are well known to promote plant growth by inducing the degradation of a class of nuclear growth-repressing proteins, called DELLAs. In recent years, GA and DELLAs are also increasingly implicated in plant responses to pathogen attack, although our understanding of the underlying mechanisms is still limited, especially in monocotyledonous crop plants. Aiming to further decipher the molecular underpinnings of GA- and DELLA-modulated plant immunity, we studied the dynamics and impact of GA and DELLA during infection of the model crop rice (Oryza sativa) with four different pathogens exhibiting distinct lifestyles and infection strategies. Opposite to previous findings in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), our findings reveal a prominent role of the DELLA protein Slender Rice1 (SLR1) in the resistance toward (hemi)biotrophic but not necrotrophic rice pathogens. Moreover, contrary to the differential effect of DELLA on the archetypal defense hormones salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) in Arabidopsis, we demonstrate that the resistance-promoting effect of SLR1 is due at least in part to its ability to boost both SA- and JA-mediated rice defenses. In a reciprocal manner, we found JA and SA treatment to interfere with GA metabolism and stabilize SLR1. Together, these findings favor a model whereby SLR1 acts as a positive regulator of hemibiotroph resistance in rice by integrating and amplifying SA- and JA-dependent defense signaling. Our results highlight the differences in hormone defense networking between rice and Arabidopsis and underscore the importance of GA and DELLA in molding disease outcomes.

Throughout their lifespan, plants are continuously subjected to attack by a wide variety of microbial pathogens, including fungi, bacteria, viruses, and oomycetes. Based on their lifestyles and infection strategies, plant pathogens are broadly divided into three classes: biotrophs, hemibiotrophs, and necrotrophs. Biotrophs establish a long-term feeding relationship with their host, deriving nutrients from living cells, whereas necrotrophs kill host cells by secreting toxins or enzymes and then feed on the remains. However, many pathogens can behave as both biotrophs and necrotrophs depending on the stage of their life cycle and are thus termed hemibiotrophs (Pieterse et al., 2009).

To defend themselves against these different types of attackers, plants have evolved a two-tiered immune system comprising several strategic layers of constitutive and inducible defenses (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Preformed physical and chemical barriers constitute the first line of defense and ward off the majority of pathogens. Moreover, those few pathogens able to breach the plant’s constitutive defenses are confronted with an array of inducible immune responses, including a burst of oxidative metabolism, the production of antimicrobial metabolites, and defense-related proteins and local strengthening of the cell wall by callose and lignin deposits (Macho and Zipfel, 2014). The activation and regulation of these inducible defenses is controlled by a matrix of intertwined signal transduction pathways within which phytohormones play central roles (Pieterse et al., 2012).

Salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) are the archetypal immunity hormones, and their importance in the hard wiring of the plant defense signaling network is well established (Pieterse et al., 2009). Upon infection, plants produce specific blends of these hormones, with the exact combination seemingly depending on the pathogen’s lifestyle. In the dicotyledonous model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), SA signaling generally confers resistance against (hemi)biotrophic pathogens, whereas JA/ET signaling most often deter necrotrophic pathogens (Robert-Seilaniantz et al., 2011). More recently, other hormones such as abscisic acid, brassinosteroids (BRs), cytokinins, gibberellic acid (GA), and auxins, emerged as critical regulators of plant-microbe interactions as well. Moreover, evidence is accumulating that these hormones influence disease outcomes by interfering with the SA-JA/ET backbone of the plant immune system, a phenomenon often referred to as hormone crosstalk (Robert-Seilaniantz et al., 2011). Such crosstalk among individual hormone pathways is thought to provide the plant with a powerful regulatory potential to flexibly tailor its immune response to the type of attacker encountered. Moreover, considering that activation of defense responses requires substantial amounts of energy and generally comes at the expense of growth and development, hormone crosstalk also enables plants to use their limited resources in a cost-efficient manner (Bolton, 2009; Pieterse et al., 2012). In compliance with this concept, recent work has underscored the importance of JA and GA crosstalk mechanisms in orchestrating the plant’s growth-versus-defense conflict (Wild et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012; Huot et al., 2014).

GAs are a large family of tetracyclic diterpene phytohormones that are essential for plant growth and development. GA controls major growth processes such as cell expansion and division within different plant organs, flower and seed development, as well as germination (Hauvermale et al., 2012). Over the past decade, significant progress has been made toward unraveling the mechanism of GA perception and signal transduction in rice (Oryza sativa) and Arabidopsis. In these plant species, GA is well known to promote plant growth by inducing the degradation of a class of nuclear growth-repressing proteins called DELLAs (Schwechheimer, 2011; Claeys et al., 2014). Although much remains to be discovered about the underpinning mechanisms, DELLAs are thought to act as transcriptional repressors by sequestering and inhibiting the action of GA-responsive transcription factors (TFs). In rice, binding of bioactive GA to the soluble GA receptor GID1 (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2005) promotes interaction with the single DELLA protein SLR1 (Itoh et al., 2002; Murase et al., 2008). The stabilized trimeric complex consisting of GA, GID1, and SLR1 is then targeted for polyubiquitination by the F-box protein GID2, leading to rapid degradation of SLR1 by the 26S proteasome and resultant relief of the SLR1-imposed growth restraint (Sasaki et al., 2003). A similar yet more complicated pathway is operative in Arabidopsis with three GA receptors (GIDa, GIDb, and GIDc), five DELLA proteins (RGA, GAI, RGL1, RLG2, and RLG3), and the F-box protein SLY1 (Hauvermale et al., 2012).

Despite being first discovered in the plant pathogenic fungus Gibberella fujikuroi, GA was only recently implicated in plant responses to pathogen attack (for review, see De Bruyne et al., 2014). Most notably, three groups independently demonstrated that DELLAs promote JA-dependent defense signaling via competitive binding to JA ZIM-domain (JAZ) proteins (Hou et al., 2010; Wild et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012). JAZs bind and inhibit the activity of numerous TFs, key among which is the JA transcriptional activator MYC2 (Kazan and Manners, 2012). Without GA, stabilized DELLAs compete with MYC2 for binding to JAZs, thereby releasing free MYC2 to activate JA-responsive gene expression. In contrast, under conditions favorable to growth, GA rapidly degrades DELLA proteins, enabling JAZs to sequester MYC2 and disrupt JA signaling. Consistent with this so-called “relief of repression” model, Navarro et al. (2008) previously reported that DELLA modulates immunity in Arabidopsis by promoting JA perception and/or signaling and antagonizing SA, thus enhancing resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Alternaria brassicicola and susceptibility to the hemibiotrophic leaf spot pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. However, it remains to be tested whether the conceptual framework emerging from these studies can be translated to other plant pathosystems.

Although Arabidopsis has proven to be an excellent model for studying hormone defense networking, recent studies using alternative model systems such as rice are starting to provide important new insights. Consumed daily by more than 3 billion people worldwide and accounting for up to 50% of the daily caloric uptake of the world’s poor, rice is arguably the world’s most important staple food. Moreover, due to its relatively small and fully sequenced genome, its ease of transformation, accumulated wealth of genetic and molecular resources, and extensive synteny and collinearity with other cereals, rice is an excellent model for molecular genetic studies in monocots (Jung et al., 2008). Intriguingly, recent findings propose a conceptually different model for rice defense signaling that challenges the widely accepted dichotomy between the effectiveness of the SA and JA pathways and the overall infection biology of the invading pathogen (Yamada et al., 2012; De Vleesschauwer et al., 2013, 2014; Riemann et al., 2013; Taniguchi et al., 2014). Perhaps most conspicuously, synergistic SA-JA interactions seem to prevail in rice and the two hormones are hypothesized to feed into a common defense pathway that can be effective against both hemibiotrophic and necrotrophic rice pathogens (De Vleesschauwer et al., 2013, 2014; Tamaoki et al., 2013).

Given these apparent differences in defense signaling between rice and Arabidopsis and aiming to further decipher the immune-regulatory potential of DELLAs, we analyzed the role and function of GA and the rice DELLA protein SLR1 in molding disease and resistance against various types of rice pathogens. Contrary to the proposed role of DELLA in promoting necrotroph resistance in Arabidopsis, we found that SLR1 conditions strong levels of resistance against the hemibiotrophic rice pathogens Magnaporthe oryzae and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae while being largely ineffective against the necrotrophs Rhizoctonia solani and Cochliobolus miyabeanus. Moreover, our results support a scenario whereby SLR1 integrates and amplifies both SA and JA defense signaling pathways, further highlighting the unique complexities associated with hormone defense networking in rice.

RESULTS

The Rice DELLA Protein SLR1 Enhances Resistance to Hemibiotrophic Rice Pathogens

Previous work revealed that opposite to the situation in Arabidopsis, GA signaling in rice enhances susceptibility to the hemibiotrophic pathogens X. oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) and M. oryzae, causal agents of bacterial leaf blight and rice blast diseases, respectively (Tanaka et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008; Qin et al., 2013). However, no studies to date have addressed the importance of SLR1, the only DELLA protein in rice, in the resistance against these pathogens. In a first attempt to decipher the immune-regulatory role of DELLA in rice, we performed a series of bioassays with several GA-deficient and/or insensitive rice mutants, all of which are known to overaccumulate SLR1 (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2008).

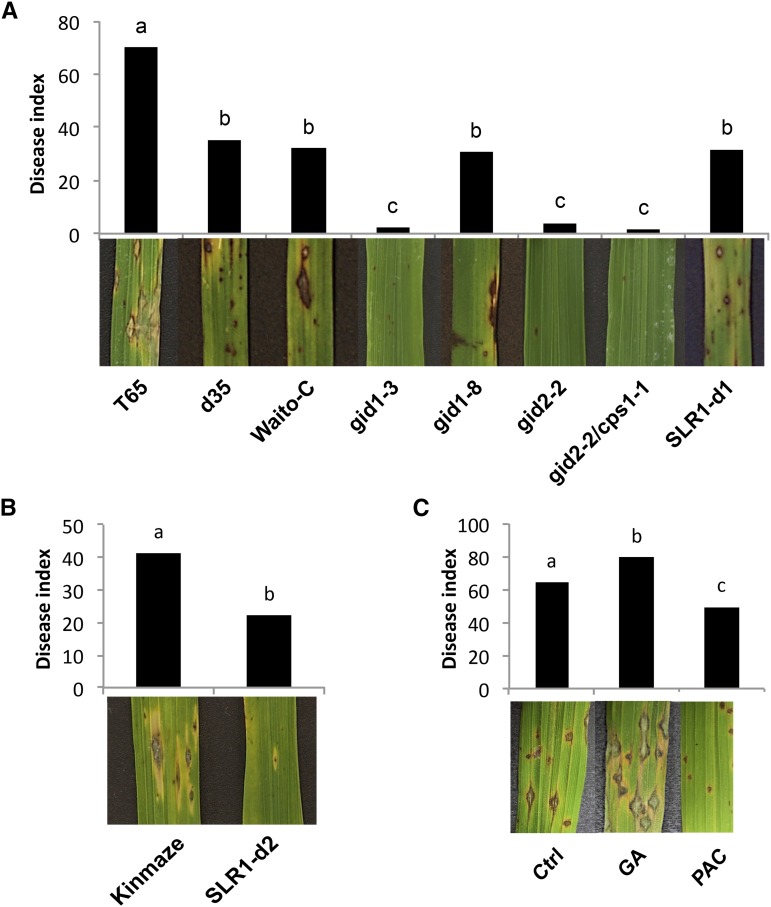

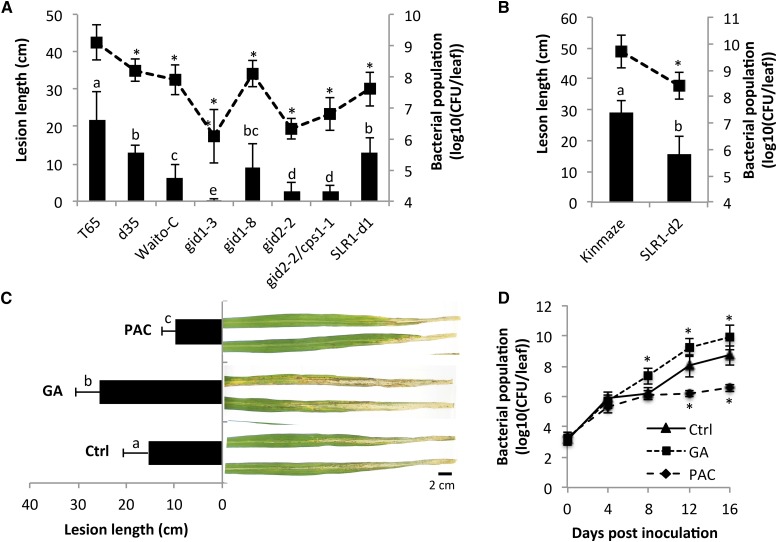

As shown in Figure 1A, all rice mutants tested, either impaired in GA biosynthesis (Waito-C and d35), insensitive to GA (gid1-8, gid1-3, and gid2-2), or both (gid2-2/cps1-1), were significantly more resistant to infection with the highly virulent M. oryzae strain VT7 compared to T65 wild-type plants. Within 4 to 5 d postinoculation (dpi), T65 leaves developed large, spindle-shaped lesions with a gray center, indicative of sporulation of the fungus. In contrast, all GA mutants exhibited a marked reduction in the number of these susceptible-type lesions, producing a resistance phenotype characterized by either the occurrence of nonsporulating necrotic spots (d35, Waito-C, and gid1-8) or the almost complete lack of visible disease symptoms (gid1-3, gid2-2, and gid2-2/cps1-1). Enhanced resistance to blast disease was also observed in two independent SLR1 gain-of-function mutants, SLR1-d1 and SLR1-d2 (Fig. 1, A and B). Interestingly, similar results were obtained upon infection with Xoo strain PXO99, with all mutants tested displaying a strong reduction in both lesion lengths and bacterial densities compared to control T65 plants (Fig. 2, A and B).

Figure 1.

GA and the DELLA protein SLR1 mount susceptibility and resistance, respectively, against the rice blast pathogen M. oryzae. A, Rice mutants impaired in GA biosynthesis (Waito-C and d35), insensitive to GA (gid1-3, gid1-8, and gid2-2), or both (cps1-1/gid2-2) and the SLR1 gain-of-function allele SLR1-d1 display enhanced resistance compared to wild-type T65 plants. Plants were challenged when 4 weeks old (five-leaf stage) by spraying a spore suspension of virulent M. oryzae strain VT7 at 2 × 104 spores⋅mL−1. Photographs depicting representative symptoms were taken at 7 d after inoculation. B, Effect of the SLR1 gain-of-function mutation SLR1-d2 on basal blast resistance in cultivar Kinmaze. C, Exogenously administered GA3 (50 µm) and the GA biosynthesis inhibitor PAC (500 µm) differentially affect blast resistance in cultivar T65. Plants were treated with both chemicals 3 d prior to challenge inoculation. Control (Ctrl) plants were treated with water only. In all graphs, data presented are from a representative experiment that was repeated at least twice with similar results. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Mann-Whitney, n ≥ 6, α = 0.05).

Figure 2.

SLR1 positively regulates resistance to the rice leaf blight pathogen Xoo. A, Rice mutants impaired in GA biosynthesis (Waito-C and d35), insensitive to GA (gid1-3, gid1-8, and gid2-2), or both (cps1-1/gid2-2) and the SLR1 gain-of-function allele SLR1-d1 all display enhanced resistance compared to wild-type T65 plants. Fifth and sixth stage leaves were inoculated with Xoo strain PXO99 using the standard leaf-clipping method. Fourteen days after inoculation, disease was evaluated by measuring the length of the water-soaked leaf blight lesions and assessing bacterial growth in planta. B, Effect of the SLR1 gain-of-function mutation SLR1-d2 on leaf blight development and PXO99 titers in cultivar Kinmaze. C and D, Effect of pretreatment with GA3 (50 µm) and the GA biosynthesis inhibitor PAC (500 µm) on leaf blight development and PXO99 titers in T65 plants. Lesion length data are means ± sd. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Mann-Whitney, n ≥ 14, α = 0.05). Bacterial population data are means ± se of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to control treatments (LSD; α = 0.05). All experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

In an alternative approach to study the immunity-associated role of GA and SLR1, we tested the impact of artificially manipulating in planta GA and SLR1 levels by treating wild-type T65 plants with either GA3, one of the most bioactive GA species, or the GA biosynthesis inhibitor paclobutrazole (PAC). As shown in Figure 1C, spraying plants with 100 µm GA3 3 d prior to challenge with M. oryzae significantly increased symptom development, whereas 50 µm PAC treatment (which restricts GA biosynthesis and increases SLR1 levels) led to a substantial reduction in disease severity. Moreover, treating T65 with GA3 or PAC also resulted in significantly enhanced susceptibility and resistance against Xoo, respectively (Fig. 2C). Importantly, bacterial growth analyses correlated well with lesion length developments (Fig. 2D). At 16 dpi, PXO99 titers reached approximately 9 × 109 colony forming units/leaf in GA-pretreated leaves, a greater than 10-fold increase compared to nontreated control T65. In PAC-treated T65, however, PXO99 grew 100-fold less than in the controls with populations leveling off to fewer than 6 × 106 colony forming units/leaf. Neither GA3 nor PAC had a significant impact on the in vitro growth of M. oryzae and Xoo (data not shown). In conjunction with abovementioned mutant data, these findings strongly suggest that GA and SLR1 act as negative and positive regulators of hemibiotroph resistance in rice, respectively.

SLR1-Mediated Resistance Is Ineffective against Necrotrophic Rice Pathogens

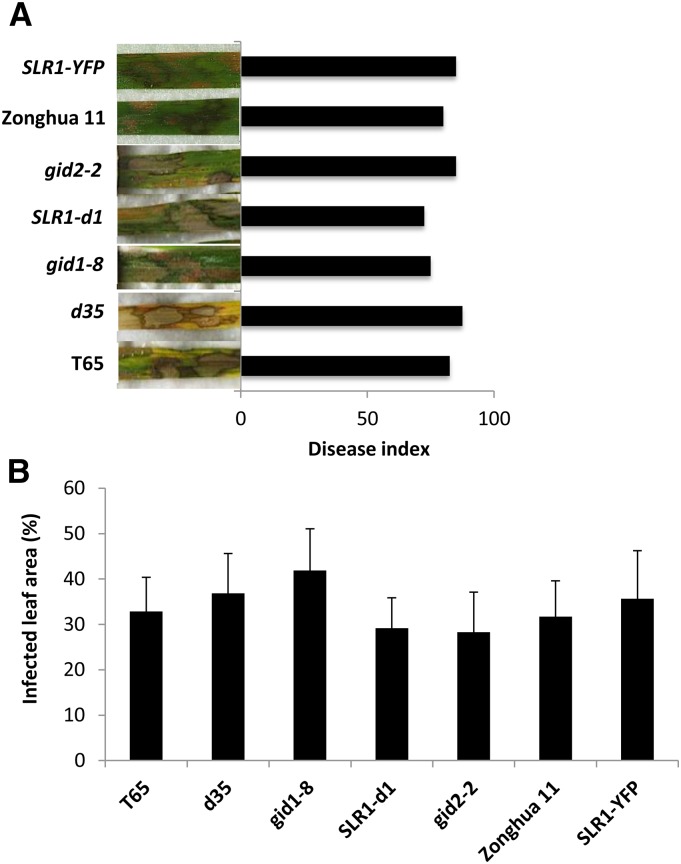

To test whether SLR1 also conditions resistance against other types of rice pathogens, additional bioassays were performed with the sheath blight pathogen R. solani and the brown spot fungus C. miyabeanus. In contrast to M. oryzae and Xoo, which invade living rice cells, R. solani and C. miyabeanus kill host cells at very early stages in the infection and are considered necrotrophic pathogens (De Vleesschauwer et al., 2013). Six rice cultivars including the GA mutants d35, gid1-8, and gid2-2, the SLR1 gain-of-function mutant SLR1-d1, and a transgenic line overexpressing an SLR1-YFP fusion protein were challenged with R. solani AG1-1A strain16 and C. miyabeanus strain Cm988. However, in contrast to the results obtained with M. oryzae and Xoo, inoculations with R. solani did not reveal any significant differences in disease severity between wild-type T65 plants and any of the mutant and transgenic lines (Fig. 3A). Similarly, all mutants displayed wild-type levels of susceptibility toward C. miyabeanus (Fig. 3B). Pretreatment of wild-type T65 plants with either GA3 or PAC also failed to alter subsequent disease development (data not shown), further suggesting that the effect of SLR1 on resistance to R. solani and C. miyabeanus is limited at best. Opposite to the situation in Arabidopsis where DELLA proteins promote resistance to necrotrophs and susceptibility to biotrophs (Navarro et al., 2008), SLR1 thus seems to function mainly as a positive regulator of (hemi)biotroph resistance in rice.

Figure 3.

SLR1 is no major player in resistance or susceptibility against the necrotrophic rice pathogens R. solani and C. miyabeanus. A, Detached leaf assays revealed no significant differences in disease severity caused by R. solani AG1-1A strain16 between wild-type T65 plants, GA-deficient (d35) or GA-insensitive (gid1-8 and gid2-2) mutants, and the SLR1 gain-of-function allele SLR1-d1. Similar results were obtained for wild-type Zonghua plants and a transgenic line overexpressing an SLR1-YFP fusion protein. B, Above-mentioned genotypes also show wild-type levels of susceptibility against virulent C. miyabeanus strain Cm988. Data are means ± sd (Tukey, n ≥ 36, α = 0.05). Repetition of experiments led to results similar to those shown.

Rice SA and JA Signaling Antagonize GA-Induced Growth Promotion

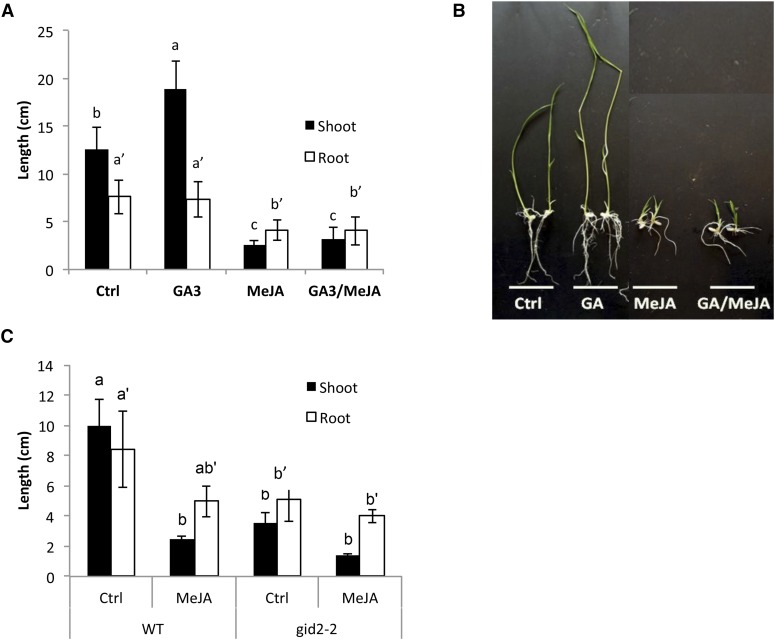

Previous work by Navarro et al. (2008) showed that in Arabidopsis, DELLAs regulate immunity by modulating the balance between the archetypal defense hormones SA and JA in favor of JA. Moreover, accumulating evidence indicates that reciprocal antagonism between the JA and GA pathways is a key mechanism enabling plants to balance growth and defense (Yang et al., 2012; Huot et al., 2014; De Bruyne et al., 2014). To confirm and extend these findings in rice and gain further insight into the molecular underpinnings of GA- and SLR1-mediated immunity, we first sought to assess the effect of single and combined JA and GA applications on the growth phenotype of young rice seedlings. To this end, rice seeds (cultivar T65) were grown on Gamborg’s B5 (GB5) agar plates containing 100 µm methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and/or 100 µm GA3. One week after imbibition, the shoot and root lengths were measured.

According to our expectations, treatment with GA promoted shoot length, while MeJA application significantly reduced shoot and root length (Fig. 4, A and B). Moreover, addition of GA had no significant impact on the MeJA-induced growth restriction, which is suggestive of negative crosstalk in the direction of JA damping rice GA action (Fig. 4, A and B). To confirm these observations, we next tested the effect of 100 µm MeJA on the growth phenotype of GA-insensitive gid2-2 mutants. These mutant plants, which contain a loss-of-function mutation in the F-box protein GID2 and, hence, overaccumulate SLR1, show a severe dwarf phenotype with wide leaf blades and dark green leaves. As shown in Figure 4C, treatment with MeJA reduced shoot and root length in wild-type plants, while being comparatively less effective in the gid2-2 background. In addition, no significant differences could be observed between MeJA-treated wild-type plants and gid2-2 mutants grown in the presence or absence of MeJA, further suggesting that JA inhibits rice growth through repressing GA signaling (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Rice JA signaling restricts GA-induced growth promotion. A and B, Effect of exogenous GA and JA treatment on shoot and root development in rice. T65 plants were grown for 7 d on GB5 medium containing GA3 (100 μm) and/or MeJA (100 μm). Pictures shown in B were taken 10 d after imbibition. C, Effect of exogenous MeJA treatment on shoot and root development in wild-type T65 and GA-insensitive gid2-2 mutant plants. All data shown are means ± sd of representative experiments that were repeated at least once with similar results. Statistically significant differences between treatments are labeled with different letters (Tukey, n ≥ 7, α = 0.05).

Rice SA and JA Signaling Antagonize GA-Induced Disease Susceptibility

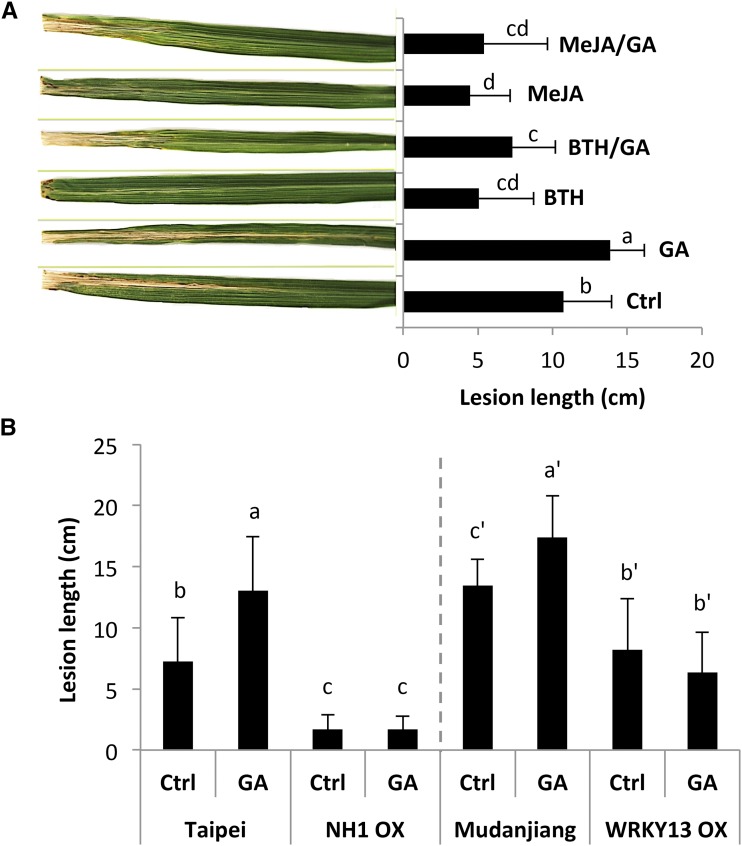

Having shown that JA signaling attenuates GA-triggered growth promotion, we next turned our attention to the possible involvement and significance of GA-JA and GA-SA interplay in regulating resistance against Xoo. To this end, we first examined the effect of exogenous hormone application on subsequent pathogen inoculation in wild-type T65 plants. Leaves of 6-week-old plants were sprayed until runoff with 100 µm GA3 and/or 100 µm MeJA and 500 µm benzothiadiazole (BTH), a synthetic SA analog, and 3 d later, inoculated with Xoo using the leaf-clipping method. As shown in Figure 5A and consistent with previous findings (Yang et al., 2008; Yamada et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2013), BTH and MeJA pretreatment significantly increased basal leaf blight resistance compared to control, nontreated plants, whereas GA3 application resulted in enhanced disease susceptibility (Fig. 5A). Moreover, coapplication of BTH or MeJA and GA3 showed no significant differences compared to single SA- and JA-treatments, indicating that turning on SA and JA signaling suppresses GA-mediated susceptibility against Xoo.

Figure 5.

Rice SA and JA signaling attenuate GA-induced susceptibility against the leaf blight pathogen Xoo. A, Effect of single and combined hormone treatments on leaf blight development in rice. Six-week-old T65 plants were sprayed with GA3 (100 µm) in combination or not with MeJA (100 µm) or BTH (500 µm) and, 3 d later, inoculated with Xoo strain PXO99 using the leaf-clipping method. Pictures showing representative disease development were taken 14 d after inoculation (Mann-Whitney, n ≥ 12, α = 0.05). B, Overexpression of OsNH1 but not OsWRKY13 blocks GA3-induced Xoo susceptibility. All genotypes (OsNH1 OX, OsWRKY13 OX, and the respective wild-types Taipei and Mudanjiang) were sprayed with 100 µm GA3 3 d prior to challenge inoculation. Data are means ± sd and statistically significant differences between treatments are labeled with different letters (Mann-Whitney, n ≥ 12, α = 0.05). Both experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

To further characterize the effect of GA-SA interplay on Xoo immunity, additional experiments were performed using transgenic rice lines overexpressing OsNH1 (NH1 OX) and OsWRKY13 (WRKY13 OX). OsNH1 is the closest rice ortholog of the master SA regulatory protein NPR1 (Yuan et al., 2007), while OsWRKY13 is a well-characterized transcription factor functioning upstream of OsNH1 (Qiu et al., 2007, 2008). As shown in Figure 5B, both OX lines were significantly more resistant to bacterial inoculation compared to the corresponding wild-types, confirming the importance of SA signaling in basal Xoo resistance (Qiu et al., 2007; Yuan et al., 2007). Moreover, whereas GA3-treated wild-type lines showed a higher susceptibility toward Xoo compared to control plants, no significant differences in disease severity could be observed between control and GA3-treated OX lines. Together with aforementioned results, these finding suggest that SA may attenuate GA-mediated susceptibility toward Xoo at least in part through OsNH1 and OsWRKY13.

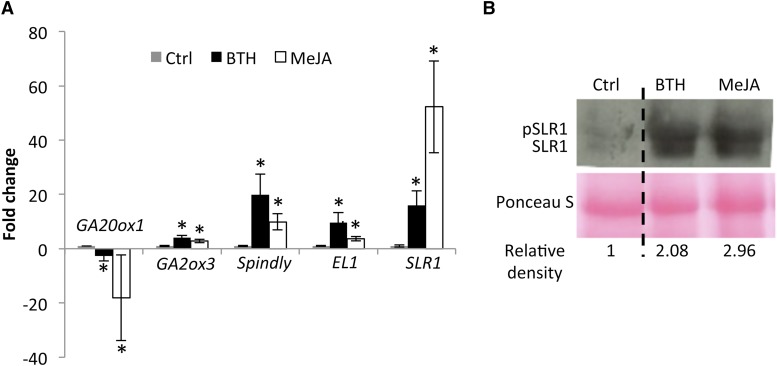

SA and JA Interfere with GA Metabolism and Stabilize SLR1

Crosstalk between hormone pathways may occur at the level of biosynthesis regulation, signal transduction, and/or gene expression. To gain further insight into the molecular mechanisms of SA-GA and JA-GA interplay, we measured the transcript levels of several GA biosynthetic and regulatory genes in 6-week-old T65 plants treated for 8 h with either 500 µm BTH or 100 µm MeJA. As shown in Figure 6A, BTH and MeJA treatment significantly induced expression of the GA-degrading gene gibberellin 2-β-dioxygenase3 (OsGA2ox3). Furthermore, the GA biosynthesis gene gibberellin 20-β-oxidase1 (OsGA20ox1), which catalyzes consecutive steps of oxidation during late stages of the GA biosynthetic pathway, was severely down-regulated following hormone treatment, suggesting that SA and JA antagonize GA by impinging on the rice GA biosynthesis machinery. However, besides interfering with GA metabolism, SA and JA also may reduce GA action through transcriptional activation of GA repressor genes. Over the last few years, several rice proteins with an inhibitory function in GA signaling have been characterized. These include the O-linked GlcNAc (O-GlcNAc) transferase SPINDLY and the casein kinase early flowering 1 (EL1). Phosphorylation by EL1 has been found to be crucial for SLR1 stability (Dai and Xue, 2010), while SPINDLY-mediated O-GlcNAcylation is thought to enhance SLR1 protein activity (Shimada et al., 2006). As shown in Figure 6A, both SPINDLY and EL1 were severalfold upregulated after treatment with BTH and MeJA, suggesting that SA and JA trigger the expression of GA repressor proteins as yet another mechanism to inhibit GA action. Previously, Yang et al. (2012) reported a positive effect of MeJA treatment on SLR1 stability in young rice seedlings. Accordingly, we found MeJA to strongly induce expression of the DELLA-encoding gene SLR1 (Fig. 6A) and significantly increase SLR1 protein levels in transgenic plants overexpressing an SLR1-YFP fusion protein (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, similar results were obtained in response to BTH application. These findings suggest that JA and SA may target multiple regulatory modules of the rice GA pathway.

Figure 6.

Multilevel interactions mediate SA/JA-GA crosstalk in rice. A, Effect of BTH (500 µm) and MeJA (100 µm) treatment on expression of GA biosynthesis and GA regulatory genes. Samples were taken 8 h after treatment. Transcript levels were normalized using actin as an internal reference and expressed relative to the normalized expression levels in water-treated control (Ctrl) plants. Data are means ± sd of two technical and two biological replicates from a representative experiment, with each biological replicate representing a pooled sample from at least six individual plants. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to control samples (t test, α = 0.05). B, Immunoblot analysis of SLR1 protein accumulation 24 h after MeJA and BTH treatment in 3-week-old SLR1-YFP plants. To facilitate detection of SLR1-YFP, all plants were grown on GB5 medium containing 50 μm PAC. Protein levels were analyzed by western blotting using a polyclonal anti-YFP antibody. Membranes were stained with Ponceau S as loading control. SLR1 migrates as two bands, with the upper one representing the phosphorylated protein. Relative band densities were analyzed using ImageJ software. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

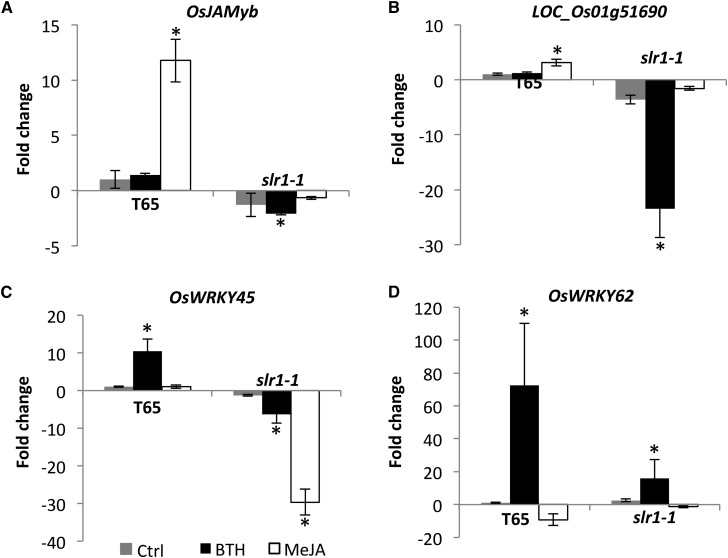

SLR1 Integrates and Amplifies SA- and JA-Dependent Defense Signaling

The observation that SA and JA treatment increases SLR1 stability and the reported role of Arabidopsis DELLA proteins in modulating the signaling, perception or biosynthesis of SA and JA (Navarro et al., 2008) prompted us to ask whether SLR1 orchestrates SA and JA signaling in rice. To answer this question, we initially tested the effect of an SLR1 loss-of-function mutation on the expression of SA- and JA-responsive marker genes. Carrying a single recessive mutation in SLR1, slr1-1 mutant plants display a constitutive GA response phenotype characterized by extensive shoot elongation (Ikeda et al., 2001). In wild-type seedlings, expression of the JA marker genes OsJAMyb and LOC_Os01g51690 and the SA-responsive genes OsWRKY45 and OsWRKY62 was strongly activated in response to 100 μm MeJA and 500 μm BTH, respectively (Fig. 7). LOC_Os01g51690 and OsJAMyb are two JA-inducible proteins that are involved in downstream JA signaling, while OsWRKY45 and its target OsWRKY62 are SA master regulatory proteins that function parallel to OsNH1 in the BTH-inducible defense program in rice (Shimono et al., 2007; Sugano et al., 2010). Intriguingly, expression of both JA and SA marker genes was severely inhibited in the slr1-1 background, suggesting a positive role of SLR1 in both JA- and SA-mediated defense signaling. Moreover, SLR1 also appears to be involved in regulating JA-SA antagonism as BTH-induced down-regulation of OsJAMyb and LOC_Os01g51690 as well as MeJA-induced repression of OsWRKY45 were evident in slr1-1 plants only.

Figure 7.

SLR1 boosts SA and JA signaling in rice. A to D, Effect of BTH (500 µm) and MeJA (100 µm) treatment on the expression of SA and JA marker genes in 3-week-old wild-type T65 and the SLR1 loss-of-function mutant slr1-1. Samples were taken 8 h after treatment. Transcript levels were normalized using actin as an internal reference and expressed relative to the normalized expression levels in water-treated control (Ctrl) plants. Data are means ± sd of two technical and two biological replicates from a representative experiment, with each biological replicate representing a pooled sample from at least six individual plants. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to control-treated T65 plants (t test, α = 0.05).

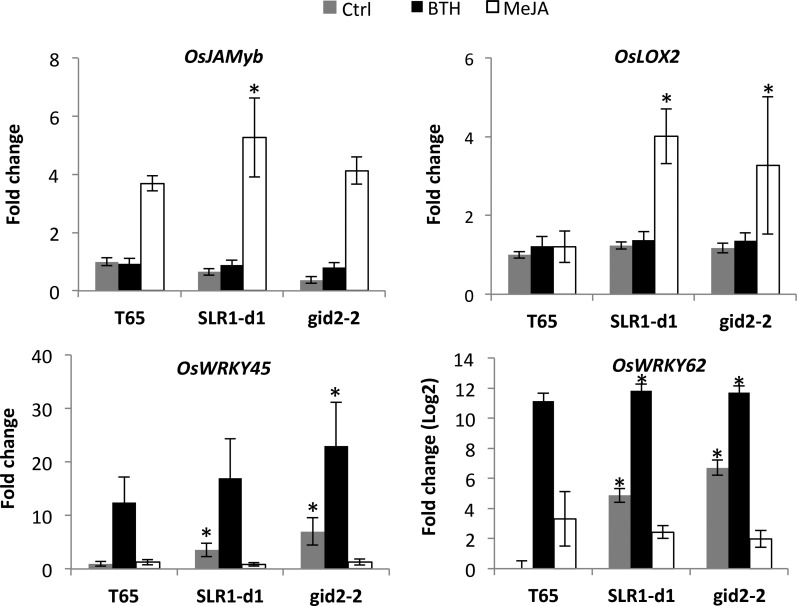

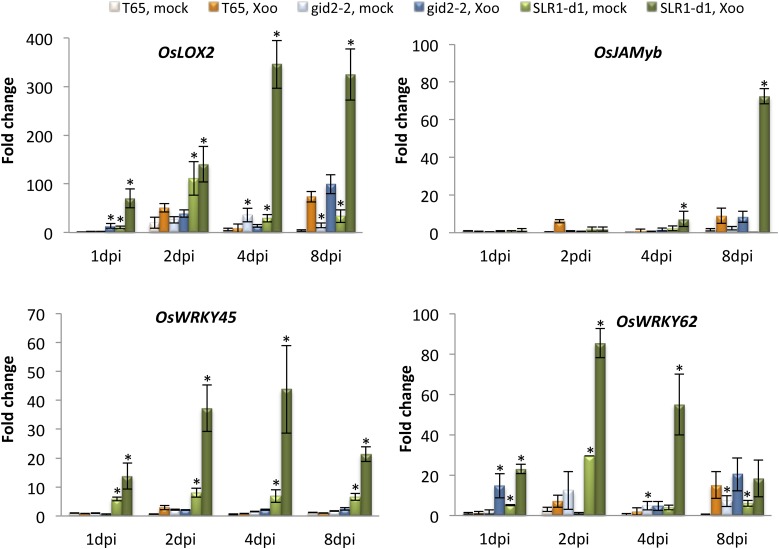

Additional evidence supporting positive SLR1-SA/JA crosstalk came from evaluating the impact of increased SLR1 action on SA- and JA-responsive gene expression. First, enhancing SLR1 protein levels by supplying plants with 50 μm PAC significantly increased the ability of BTH and MeJA to induce marker gene expression (Supplemental Fig. S1). In a similar vein, we found BTH- and MeJA-inducible gene expression to be boosted in GA-insensitive gid2-2 and SLR1 gain-of-function SLR1-d1 mutant plants (Fig. 8). Although less evident in case of the JA response gene OsJAMyb, a strong stimulating effect of SLR1 was noticed for the JA biosynthetic gene OsLOX2, with MeJA treatment up-regulating gene expression in the mutant backgrounds only. In a similar vein, basal and BTH-inducible transcription of the SA-responsive genes OsWRKY45 and OsWRKY62 was significantly higher in SLR1-d1 and/or gid2-2 compared to the wild type, further suggesting that SLR1 amplifies SA and JA signaling (Fig. 5).

Figure 8.

Effect of BTH (500 µm) and MeJA (100 µm) treatment on the expression of SA and JA marker genes in wild-type T65, SLR1 gain-of-function SLR1-d1, and GA-insensitive gid2-2 plants. Samples were taken 8 h after treatment. Control (Ctrl) plants were treated with water only. Transcript levels were normalized using actin as an internal reference and expressed relative to the normalized expression levels in Ctrl-treated T65. Data are means ± sd of three technical replicates of a pooled sample from at least six individual plants. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences per treatment (Ctrl, BTH, and MeJA) between SLR1 mutant plants and T65 (t test, α = 0.05).

SLR1-Triggered Hemibiotroph Resistance Is Associated with Activation of SA- and JA-Dependent Defenses

The observation that SLR1 confers resistance to (hemi)biotrophic pathogens, the previously reported role of both SA and JA signaling in basal immunity to Xoo (for review, see De Vleesschauwer et al., 2013, and references herein), and the stimulative effect of SLR1 on SA/JA-responsive gene expression strongly suggested that SLR1 promotes (hemi)biotroph resistance in rice by integrating and amplifying SA- and JA-controlled defenses. To verify this hypothesis, we tested the expression of several JA- and SA-responsive genes and quantified SA and JA titers at various time points after inoculation with Xoo in wild-type T65, GA-insensitive gid2-2, and SLR1 gain-of-function SLR1-d1 plants. As shown in Figure 9, expression of the JA marker gene OsJAMyb responded strongly to Xoo infection and peaked at 8 dpi for all the rice lines. At this time point, pathogen-induced transcription of OsJAMyb was most pronounced in SLR1-d1 plants, with mRNA levels peaking at 7 times the levels found in the other inoculated lines. In a similar vein, Xoo inoculation entailed a strong up-regulation of the JA biosynthetic genes OsLOX2 and OsAOS2 in both wild-type and SLR1 mutant plants throughout the course of infection (Fig. 9; Supplemental Fig. S2). In SLR1 mutant plants, however, both genes were generally induced earlier and/or to higher extent compared to wild-type plants. Accordingly, hormone measurements in pathogen-inoculated leaves revealed significantly higher JA levels in gid2-2 versus the wild type at 1 and 8 dpi (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Figure 9.

Effect of Xoo inoculation on SA- and JA-responsive genes in wild-type T65, SLR1 gain-of-function SLR1-d1, and GA-insensitive gid2-2 plants. Transcript levels were normalized using actin as an internal reference and expressed relative to the normalized expression levels in mock-inoculated T65 plants at 1 dpi. Data are means ± sd of two technical and two biological replicates, with each replicate representing a pooled sample from at least six individual plants. Within each time point, asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between mock or Xoo-inoculated SLR1 mutant plants and similarly treated T65 (t test, α = 0.05).

In contrast but consistent with earlier findings (Silverman et al., 1995; Xu et al., 2015), neither the wild type nor gid2-2 showed significant changes in SA content, except for a moderate 2-fold increase at 8 dpi (Supplemental Fig. S3). Nevertheless, SA-signaling appears to contribute to the SLR1-conferred resistance as evidenced by the transcriptional reprogramming of the SA-responsive marker genes OsWRKY45 and OsWRKY62 in the mutant backgrounds. For instance, OsWRKY45 mRNA levels in SLR1-d1 plants responded strongly to pathogen infection and peaked at 4 dpi, whereas in control plants, transcription of OsWRKY45 remained static throughout the course of infection (Fig. 9). A fairly similar scenario was observed for OsWRKY62, with both Xoo inoculation and SLR1 overaccumulation causing extensive gene activation throughout the course of infection (Fig. 9). Given the well-established role of SA and JA as positive signals in the activation of basal immunity to Xoo, these data strengthen the hypothesis that hyperactivation of SA- and JA-dependent defense signaling is an important mechanism contributing to SLR1-conferred Xoo resistance.

In support of this concept, western-blot experiments using SLR1-YFP-overexpressing lines revealed a strong rise in SLR1 accumulation upon Xoo inoculation, with the levels of immunologically detectable SLR1 being about four times higher at 24 h after infection compared to noninoculated controls (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Considering that SLR1-YFP OX plants exhibit moderate levels of resistance to Xoo inoculation (Supplemental Fig. S4B), these data may draw important inferences connecting rice basal Xoo resistance to increased SLR1 protein stability and resultant activation of SA- and JA-dependent immunity.

DISCUSSION

Recent advances in plant hormone research have provided fascinating insights into how the plant hormone GA is perceived and its signal transduced to modulate numerous plant growth and developmental processes. Current concepts suggest that GA promotes plant growth by inducing the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of a class of nuclear growth-repressing proteins, called DELLAs (Hauvermale et al., 2012; Schwechheimer et al., 2011). Contrary to this relative wealth of knowledge, our understanding of the role of GA and DELLAs in plant immunity is still limited. Studies in the dicot model plant Arabidopsis and in the monocotyledonous crop wheat (Triticum aestivum) revealed that DELLAs promote resistance to necrotrophs and susceptibility to biotrophs, partly by modulating the SA:JA balance in favor of JA (Navarro et al., 2008; Saville et al., 2012). In an effort to broaden our knowledge of DELLA-mediated immunity, we studied the role of the rice DELLA protein SLR1 in disease and resistance against different pathogens exhibiting distinct parasitic habits. Challenging the prevailing view that DELLAs stimulate necrotroph resistance, we show that SLR1 enhances rice defenses against the hemibiotrophic pathogens Xoo and M. oryzae while being largely ineffective against the necrotrophs R. solani and C. miyabeanus. Moreover, our results favor a scenario where SLR1 boosts basal rice immunity by integrating and amplifying the rice SA and JA signaling pathways.

While the deployment of defense mechanisms is imperative for plant survival, defense activation generally comes at the expense of plant growth. This so-called growth versus defense conflict is based on the premise that plants possess a limited pool of resources, which demand prioritization toward either growth or defense depending on external and internal factors (Huot et al., 2014). Although much remains to be discovered about the underpinning molecular processes, recent findings revealed that reciprocal JA-GA antagonism is an important regulatory mechanism enabling plants to effectively balance growth and defense (Yang et al., 2012; Huot et al., 2014). Corroborating this concept, our results show that JA restricts GA-induced growth promotion in young rice seedlings and prevents GA from inducing susceptibility toward Xoo (Figs. 4 and 5). More surprisingly, however, GA-triggered Xoo susceptibility was also strongly alleviated following coapplication of BTH or upon overexpression of the SA master regulatory proteins OsNH1 and OsWRKY13 (Fig. 5), indicating that in rice not only JA but also SA can antagonize GA. Moreover, the enhanced expression of GA-degrading (OsGA2ox3) and GA-repressor genes (SLR1, SPINDLY, and EL1), the increased levels of SLR1, and the down-regulation of the GA-biosynthesis gene OsGA20ox1 in response to BTH and MeJA treatment (Fig. 6) strongly suggest that both JA and SA affect the GA pathway at various regulatory steps. It should be noted, however, that our findings do not rule out the contribution of indirect hormone interactions. Indeed, although recent studies have highlighted the importance of JAZ-DELLA protein-protein interactions in orchestrating JA-GA interplay in various plant species (Hou et al., 2010; Wild et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012), molecular understanding of SA-GA signal interactions is still rudimentary. In light of previous reports showing positive interactions between GA and auxin and the well-documented ability of SA to suppress auxin signaling (Wang et al., 2007; Kazan and Manners, 2009), SA-GA antagonism could well be explained by an indirect effect based on the SA suppression of auxin signaling. The combinatorial application of time-resolved hormone measurements, sensitive genetic screens, and bioassays with rice mutants affected in multiple hormone pathways promise to further uncover the molecular basis of SA-GA crosstalk.

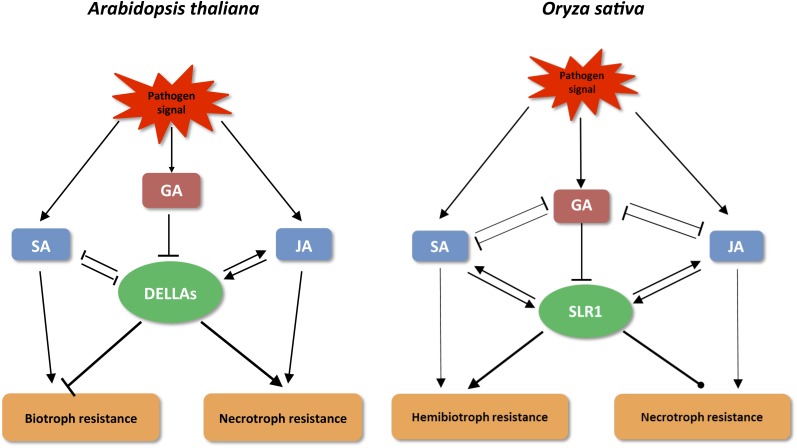

Besides the negative effect of JA and SA on GA, our results also revealed reciprocal antagonism with GA biosynthesis and signaling antagonizing SA and JA responses (Figs. 7–9; Supplemental Figs. S1–S3). Contrary to the binary Arabidopsis model with GA promoting SA action but inhibiting JA (Navarro et al., 2008), GA thus seems to interact antagonistically with both JA and SA pathways in rice (Fig. 10). Supporting this concept, mounting evidence suggests that although SA-JA antagonism is conserved in rice, positive relationships between both pathways might prevail (De Vleesschauwer et al., 2013, 2014). Most conspicuously, recent microarray studies showed that unlike in Arabidopsis, more than half of all BTH- or SA-upregulated rice genes are also induced by JA (Garg et al., 2012; Tamaoki et al., 2013). Moreover, many rice mutant and transgenic lines display simultaneously enhanced SA and JA signaling. For instance, rice plants mutated in the hydroperoxide lyase OsHPL3 display strongly enhanced JA levels concomitant with increases in SA production and heightened expression of SA-responsive PR genes (Liu et al., 2012; Tong et al., 2012). Activation of JA synthesis was also found to prime herbivore-induced SA synthesis in rice plants silenced for the phospholipase D genes OsPLDα3 and OsPLDα4, while transgenic rice lines overexpressing the ET-inducible JERF1 transcription factor showed activation of both SA and JA biosynthesis genes (Qi et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2014). Together, these findings bring a new twist to the classical crosstalk model and support the notion that although hyperactivation of one has the ability to override the other, rice SA and JA pathways may feed into a common rice defense system that is effective against different types of attackers.

Figure 10.

Model illustrating the role of DELLA in molding pathological outcomes in the model plants Arabidopsis (left) and rice (right). Although there are exceptions, defense signaling in Arabidopsis most often follows a binary model with SA and JA controlling resistance to biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens, respectively. DELLA proteins influence plant immune responses by positively interacting with JA but antagonizing SA, thereby promoting resistance to necrotrophs and susceptibility to biotrophs. In rice, however, SA and JA signaling both contribute to resistance against hemibiotrophic pathogens. In this species, SA and JA both interfere with GA signaling and stabilize the DELLA protein SLR1, with resultant amplification of SA- and JA-dependent defense responses. Contrary to the strong effects of SLR1 on hemibiotroph resistance, the impact on resistance against the necrotrophic pathogens R. solani and C. miyabeanus appears to be limited. Sharp, black lines represent positive effects, blunted lines depict antagonistic interactions, and round-ended lines indicate neutral effects.

Interestingly, the ability of both BTH and MeJA to increase SLR1 stability (Fig. 6) as well as the tight correlation between SLR1 expression levels and the strength of SA and JA-inducible gene expression in both native and Xoo-inoculated leaves (Figs. 7–9; Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2) strongly suggests that such cooperative SA/JA action is orchestrated at least in part by SLR1. Additional support for this notion comes from the observation that SA-induced down-regulation of JA marker genes and vice versa was evident in slr1 mutant plants only (Fig. 7). Although the molecular mechanisms underpinning SA-JA crosstalk are still poorly understood, recent work has pointed toward a central role of the APETALA2/ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR ORA59, which acts as a transcriptional activator in the JA pathway (Van der Does et al., 2013). In this study, it was shown that SA antagonizes JA signaling downstream of the SCFCOI1-JAZ complex by targeting GCC-box motifs in JA-responsive promoters through a negative effect on ORA59. In contrast, DELLAs reportedly enhance ORA59 activity by sequestering JAZ1 (Zhou, 2014), thus providing a mechanistic framework for how DELLA may affect SA-JA cross-communication by targeting ORA59. In view of our recent data showing the ability of SLR1 to interact with various rice JAZ proteins (D. De Vleesschauwer, H.S. Seif, S.N. Huu, M. Hofte, unpublished data), it will be highly interesting to assess whether a similar mechanism is operative in rice.

In keeping with our findings that SLR1 is positioned at the apex of SA and JA signaling in rice, DELLA proteins have been shown previously to act at the interface of developmental, physiological, and stress signaling. Although first identified as key repressors of GA signaling, a large body of data indicates that DELLAs lie at the node of multiple hormone signaling pathways. Auxin, for instance, is well known to promote root growth by stimulating GA-induced DELLA proteolysis, whereas JA, BR, cytokinin, and ET all enhance DELLA stabilization and delay its degradation by GA (Fu and Harberd, 2003; Vriezen et al., 2004; Brenner et al., 2005; Achard et al., 2007; De Vleesschauwer et al., 2012; Wild et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012). Also, DELLAs may serve as a point of integration of hormone and sugar signaling (Li et al., 2014) and are increasingly implicated in regulation of light responses (Arana et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2014). Moreover, other than harmonizing signals from multiple upstream effectors, DELLAs physically interact with a variety of downstream TFs, thus controlling the expression of a multitude of genes functioning in myriad cellular activities and biological processes (de Lucas et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2008; Hou et al., 2010; Bai et al., 2012; Gallego-Bartolomé et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Wild et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012). Together these findings are compatible with the view that DELLAs act as molecular hubs for pathway crosstalk and signal integration, permitting flexible modulation of plant growth and defense in response to various exogenous and endogenous cues.

Although our understanding of SLR1 action is still in its infancy, a similar model may hold for rice in that the impact of various hormones on resistance to M. oryzae and Xoo can be explained through their effects on SLR1 protein stability and/or signal output. For instance, both BR and flooding-induced ET are reported to enhance blast and leaf blight resistance (Nakashita et al., 2003; Singh et al., 2004) and increase SLR1 levels (Fukao and Bailey-Serres, 2008; De Vleesschauwer et al., 2012; Schmitz et al., 2013). Moreover, auxin, which functions as an important virulence factor of both pathogens (Ding et al., 2008; Domingo et al., 2009; Fu et al., 2011), is well known to promote GID2-mediated degradation of DELLA (Vriezen et al., 2004). In conjunction with our data showing the rapid increase in SLR1 levels in incompatible rice-Xoo interactions (Supplemental Fig. S4A) and considering the ability of SLR1 to integrate and amplify SA- and JA-mediated signaling, these studies favor a scenario whereby SLR1 acts as a central command element in the rice defense signaling network that molds hemibiotroph resistance by coordinating and adjusting interplay between environmental and phytohormonal signals.

Considering the vital role of DELLAs in integrating myriad cellular, developmental, and physiological processes (Sun et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2011), manipulating host DELLA signaling and hijacking GA hormone crosstalk mechanisms may represent a powerful pathogen virulence strategy. In their seminal work, Navarro et al. (2008) already demonstrated that the bacterial flagellin peptide flg22 inhibits plant growth by delaying GA-induced degradation of RGA, one of five DELLA proteins in Arabidopsis. Yet, flg22 is a conserved microbial signature that induces plant immune responses upon perception by the pattern recognition receptor FLS2 (Zipfel et al., 2004). More recently, however, it was shown that the Xanthomonas campestris effector protein XopDXcc8004 likewise targets and stabilizes RGA in the nucleus (Tan et al., 2014). Moreover, XopDXcc8004 attenuates PAMP-induced production of reactive oxygen species and suppresses disease symptoms in infected Arabidopsis and radish (Raphanus sativus) leaves (Tan et al., 2014). In this context, assessing whether Xoo or Mo similarly employ effector-mediated SLR1 intervention strategies to cause disease is an important challenge ahead.

One of the most conspicuous results in this study was the observation that despite triggering high levels of resistance against the hemibiotrophs M. oryzae and Xoo, SLR1 failed to exert any significant impact on disease severity caused by the necrotrophic leaf pathogens R. solani and C. miyabeanus (Fig. 3). These results are particularly interesting in light of the reported role of DELLAs in stimulating necrotroph resistance in other plant species and the ability of SLR1 to induce susceptibility against the necrotrophic rice root pathogen Pythium graminicola (De Vleesschauwer et al., 2012). There are several possible explanations for these apparently conflicting observations. First, it could be reasoned that the R. solani and C. miyabeanus strains used during our experiments were overly virulent and therefore may have masked possible minor effects of SLR1 on necrotroph resistance. On the other hand, it should be considered that hormone defense signaling may differ considerably between rice roots and leaves, possibly explaining the differential effects of SLR1 on disease resistance in these tissues. Most tellingly in this regard, SA levels in rice roots are about two orders of magnitude lower than in leaves (Silverman et al., 1995). Considering the central importance of SA in configuring the plant’s defense signaling network, such major differences in basal SA levels likely impact the complex hormone dynamics controlling plant innate immunity. Finally, previous studies already demonstrated that SA and JA are no major signals for the activation of defenses against C. miyabeanus (De Vleesschauwer et al., 2010; Van Bockhaven et al., 2015). Moreover, in case of R. solani, SA-mediated defenses are considered ineffective, while there is little evidence supporting a strong effect of JA (Taheri and Tarighi, 2010; Peng et al., 2012; De Vleesschauwer et al., 2013). Therefore, it is not inconceivable that the effect of SLR1 in promoting SA- and JA-dependent defense signaling and subsequent activation of (hemi)biotroph resistance simply does not lead to activation of those immune responses required for resistance toward R. solani and C. miyabeanus.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we have shown that the DELLA protein SLR1 promotes resistance against the hemibiotrophic rice pathogens M. oryzae and Xoo. Moreover, our findings favor a scenario wherein SLR1 amplifies and integrates the action of the rice SA and JA signaling pathways. While challenging the common assumption that DELLA proteins promote necrotroph resistance by stimulating JA and antagonizing SA, these data highlight the differences in hormone defense networking between rice and Arabidopsis and underscore the importance of DELLA and GA in molding disease and resistance in various plant pathosystems.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Rice (Oryza sativa) lines used in this work included the japonica cultivars T65 and Kinmaze as well as the OsWRKY13- (Qiu et al., 2008) and OsNH1-overexpression lines (Yuan et al., 2007) and their respective wild-type lines Mudanjiang and Taipei. The GA mutants d35 (ent-kaurene oxidase mutant; Itoh et al., 2004), Waito-C (GA3ox2 mutant; Itoh et al., 2001), gid1-8 (GA receptor GID1 mutant; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2008), gid2-2 (F-box protein GID2 mutant; Sasaki et al., 2003), and cps1-1/gid2-2 (ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase mutant crossed with gid2-2; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2008) and the SLR1 loss- and gain-of-function alleles slr1- 1 (Ikeda et al., 2001) and SLR1-d1, (Asano et al., 2009), respectively, all are in the T65 background, whereas SLR1-d2, another SLR1 gain-of-function allele, is in the Kinmaze background. Western-blot experiments were performed with a transgenic rice line (background Zonghua 11) overexpressing an SLR1-YFP fusion protein (Dai and Xue, 2010).

All rice seeds were routinely dehulled and surface sterilized by agitation in 2% sodium hypochlorite for 30 min, rinsed three times with sterile demineralized water, and germinated for 3 d at 28°C on wet filter paper. Germinated seedlings were placed either in potting soil (Structural; Snebbout) or in square petri dishes containing Gamborg’s 5/0.8% plant agar medium and grown under growth chamber conditions (26°C day/28°C night, 12/12 light regimen, and 70% relative humidity). Soil-grown plants were fertilized weekly until flowering with a solution containing 0.1% iron sulfate and 0.2% ammonium sulfate.

Chemical Treatments

Stock solutions of GA3 (Sigma-Aldrich), BTH (BION 50 WG; Syngenta), and MeJA (Sigma-Aldrich) were prepared in water, whereas paclobutrazole was dissolved in a few drops of ethanol. All chemicals were added to autoclaved media after cooling to approximately 60°C, with equivalent volumes of ethanol solvent being added to separate control treatments. For experiments with soil-grown rice plants, the two youngest fully developed leaves from at least six individual plants were detached, cut into 2-cm pieces, and incubated overnight on sterilized distilled water to remove any residual wounding stress. Hormone treatment was carried out in six-well plates by floating detached leaf pieces on aqueous solutions containing the respective hormones. Unless noted otherwise, soil-grown plants used for chemical treatments were 6 weeks old.

Pathogen Culture and Inoculation Assays

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae

Bacterial inoculations were performed with X. oryzae pv. oryzae strain PXO99 using the leaf-clipping method as described by Xu et al. (2013). Before inoculation. the pathogen was grown on Suc peptone agar and incubated at 28°C. For inoculation experiments, single colonies were transferred to liquid SP medium and grown for 24 to 48 h at 28°C, until the OD600 had reached 0.5. Six-week-old plants were inoculated by clipping the fifth and sixth stage leaves with scissors dipped in the Xoo suspension. Inoculated plants were kept in a dew chamber (≥92% relative humidity; 28 ± 2°C) for 24 h and thereafter transferred to growth chamber conditions for disease development. Fourteen days after inoculation, disease severity was assessed by measuring the length of the water-soaked lesions. For bacterial growth analysis, inoculated leaves from three plants were pooled, ground up thoroughly using mortar and pestle, and resuspended in 5 to 10 mL water. The leaf suspensions were diluted accordingly and plated on Suc peptone agar. Plates were incubated at 28°C in the dark and colonies were counted within 2 to 3 d.

Magnaporthe oryzae

M. oryzae isolate VT7, a field isolate from rice in Vietnam, was grown at 28°C on half-strength oatmeal agar (Difco). Seven-day-old mycelium was flattened onto the medium using a sterile spoon and exposed to blue light (combination of Philips TLD 18W/08 and Philips TLD 18W/33) for 7 d to induce sporulation. Intact plants were inoculated at the five-leaf stage by spraying a final concentration of 2 × 104 spores per milliliter in 0.5% gelatin (type B bovine skin) until run-off. Inoculated plants were kept in a dew chamber (≥92% relative humidity; 28 ± 2°C) for 24 h and thereafter transferred to growth chamber conditions for disease development. Disease symptoms were scored 7 dpi using the standard disease evaluation scale of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI, 1996): 0 = no lesions; 1 = small, brown, specks of pinhead size; 3 = small, roundish to slightly elongated, necrotic, gray spots about 1 to 2 mm in diameter; 5 = typical blast lesions infecting < 10% of the leaf area; 7 = typical blast lesions infecting 26 to 50% of the leaf area; 9 = typical blast lesions infecting > 51% leaf area and many dead leaves. Disease index (DI) values were calculated according to the following formula: DI = ∑(class × number of plants in class × 100)/total number of plants × 9.

Cochliobolus miyabeanus

C. miyabeanus strain Cm988, obtained from diseased rice in field plots at the International Rice Research Institute (Manila, Philippines), was grown for sporulation at 28°C on potato dextrose agar (PDA). Seven-day-old mycelium was flattened onto the medium using a sterile spoon and exposed to blue light for 3 d under the same conditions mentioned above. Upon sporulation, conidia were harvested exactly as stated by De Vleesschauwer et al. (2010) and resuspended in 0.5% gelatin to a final density of 1 × 104 conidia mL−1. For inoculation, sixth-stage leaves of 5-week-old rice plants were excised, cut into 7-cm segments and immediately placed onto a glass slide in 14.5 × 14.5-cm petri dishes lined with moist filter paper. Detached leaves were next inoculated with four 12 µL-droplets of spore suspension and incubated under growth chamber conditions (26°C day/28°C night, 12/12 light regimen, and 70% relative humidity). Disease development was assessed 96 h postinoculation using digital image analysis (APS assess software; Lakhdar Lamari) for quantification of symptomatic leaf areas.

Rhizoctonia solani

R. solani AG1-1A strain16 was maintained on PDA (Difco Laboratories). Detached leaves of 6-week-old plants were inoculated by carefully placing 0.6-cm-diameter agar plugs taken from 5-d-old PDA cultures on the adaxial side of the leaves. Five days after incubation under growth chamber conditions, disease symptoms were visually graded into five classes based on the leaf area affected: 1 = no infection, 2 = 1 to 10%, 3 = 11 to 25%, 4 = 26 to 50%, and 5 = more than 50% of leaf area affected. Disease index values were calculated as described above.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total leaf RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen) and subsequently treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion) to remove genomic DNA contamination. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 mg of total RNA using Multiscribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems) and random primers following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR amplifications were conducted in optical 96-well plates with the Mx3005P real-time PCR detection system (Stratagene), using Sybr Green master mix (Fermentas) to monitor double-stranded DNA synthesis. The expression of each gene was assayed in duplicate in a total volume of 25 μL including a passive reference dye (ROX) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Fermentas). The thermal profile used consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 59°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. To verify amplification of one specific target cDNA, a melting-curve analysis was included according to the thermal profile suggested by the manufacturer (Stratagene). The amount of plant RNA in each sample was normalized using OsACTIN1 (LOC_Os03g50885) as internal control and samples collected from control plants at 0 dpi or without hormone treatment were selected as calibrator. The data were analyzed using Stratagene’s Mx3005P software. Nucleotide sequences of all primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Western-Blot Analysis

Total protein samples were extracted from 3-week-old SLR1-YFP OX lines using plant protein extraction buffer (pH 8, 1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 7 mm β-mercapto-ethanol, 100 mm NaF, 1 mm NaVO3, 1 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm Na4P2O7, and 10 mm N-ethylmaleimide) with 1% protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). Following quantification using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), protein extracts were mixed with a reducing (1/5 [v/v]) sample buffer (150 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% [w/v] SDS, 10% [w/v] glycerol, 0.01% [w/v] bromophenol blue, and 0.1 m [w/v] DTT), and boiled for 5 min. Protein samples were separated in 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to Hybond ECL membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Immunodetection of SLR1-YFP was performed by using a polyclonal anti-YFP antibody and goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Dako). Peroxidase activity was detected using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fischer Scientific).

Hormone Measurements

Collected leaf samples were homogenized using liquid N2 and extracted at −80°C using the modified Bieleski solvent. After filtration and evaporation, chromatographic separation was performed on a U-HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a Nucleodur C18 column (50 × 2 mm; 1.8 µm dp) and using a mobile phase gradient consisting of acidified methanol and water. Mass spectrometric analysis was carried out in selected-ion monitoring mode with a Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), operating in both positive and negative electrospray ionization mode at a resolution of 70,000 full width at half maximum. The detailed procedure will be described elsewhere (A. Haeck and K. Demeestere, unpublished data).

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the software package SPSS Statistics v22. Normality of the data were verified by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (α = 0.05). Homoscedasticity of the data was verified by means of the modified Levene test (α = 0.05). When conditions of normality and homoscedasticity were fulfilled, data were compared by means of a Tukey test (one-way ANOVA). In case these conditions were not met, nonparametric tests were used. The latter consisted of the Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum test to examine the equality of treatment means and, in the case of significant results, the Mann-Whitney test for pairwise comparisons between any two individual treatments.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Effect of Xoo-inoculation on expression of the JA biosynthesis gene OsAOS2 in wild-type T65, SLR1 gain-of-funcion SLR1-d1 and GA-insensitive gid2-2 plants.

Supplemental Figure S2. Effect of Xoo-inoculation on expression of the JA biosynthesis gene OsAOS2 in wild-type T65, SLR1 gain-of-funcion SLR1-d1 and GA-insensitive gid2-2 plants.

Supplemental Figure S3. Quantification of endogenous JA and SA levels in T65 and gid2-2. Two youngest leaves of five-week old plants were inoculated with Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) strain PXO99 using the standard leaf-clipping method.

Supplemental Figure S4. Immunoblot analysis of SLR1 protein accumulation in leaves of 6-week-olds SLR1-YFP plants inoculated with Xoo.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences used in quantitative RT-PCR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Miyako Ueguchi-Tanaka (Nagoya University, Japan), Makoto Matsuoko (Nagoya University, Japan), Motoyuki Ashikari (Nagoya University, Japan), Hiroshi Takatsuji (NIAS, Japan), Zuhua He (National Key Laboratory of Plant Molecular Genetics, China), and Yinong Yang (Penn State University) for providing GA, SA mutant, and transgenic rice lines. We acknowledge the financial support (AUGE/11/016) from the Hercules Foundation of the Flemish Government for the UHPLC-Q-Exactive mass spectrometry equipment available at the EnVOC research group and used for hormone analysis. We also thank Lies Harinck for technical support.

Glossary

- SA

salicylic acid

- JA

jasmonic acid

- ET

ethylene

- BR

brassinosteroid

- GA

gibberellic acid

- TF

transcription factor

- dpi

days postinoculation

- PAC

paclobutrazole

- MeJA

methyl jasmonate

- BTH

benzothiadiazole

- PDA

potato dextrose agar

References

- Achard P, Baghour M, Chapple A, Hedden P, Van Der Straeten D, Genschik P, Moritz T, Harberd NP (2007) The plant stress hormone ethylene controls floral transition via DELLA-dependent regulation of floral meristem-identity genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 6484–6489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arana MV, Marín-de la Rosa N, Maloof JN, Blázquez MA, Alabadí D (2011) Circadian oscillation of gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 9292–9297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano K, Hirano K, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Angeles-Shim RB, Komura T, Satoh H, Kitano H, Matsuoka M, Ashikari M (2009) Isolation and characterization of dominant dwarf mutants, Slr1-d, in rice. Mol Genet Genomics 281: 223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai M-Y, Shang J-X, Oh E, Fan M, Bai Y, Zentella R, Sun T-P, Wang Z-Y (2012) Brassinosteroid, gibberellin and phytochrome impinge on a common transcription module in Arabidopsis. Nat Cell Biol 14: 810–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton MD. (2009) Primary metabolism and plant defense--fuel for the fire. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22: 487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner WG, Romanov GA, Köllmer I, Bürkle L, Schmülling T (2005) Immediate-early and delayed cytokinin response genes of Arabidopsis thaliana identified by genome-wide expression profiling reveal novel cytokinin-sensitive processes and suggest cytokinin action through transcriptional cascades. Plant J 44: 314–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys H, De Bodt S, Inzé D (2014) Gibberellins and DELLAs: central nodes in growth regulatory networks. Trends Plant Sci 19: 231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Xue HW (2010) Rice early flowering1, a CKI, phosphorylates DELLA protein SLR1 to negatively regulate gibberellin signalling. EMBO J 29: 1916–1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruyne L, Höfte M, De Vleesschauwer D (2014) Connecting growth and defense: the emerging roles of brassinosteroids and gibberellins in plant innate immunity. Mol Plant 7: 943–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lucas M, Davière J-M, Rodríguez-Falcón M, Pontin M, Iglesias-Pedraz JM, Lorrain S, Fankhauser C, Blázquez MA, Titarenko E, Prat S (2008) A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 451: 480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleesschauwer D, Gheysen G, Höfte M (2013) Hormone defense networking in rice: tales from a different world. Trends Plant Sci 18: 555–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleesschauwer D, Van Buyten E, Satoh K, Balidion J, Mauleon R, Choi I-R, Vera-Cruz C, Kikuchi S, Höfte M (2012) Brassinosteroids antagonize gibberellin- and salicylate-mediated root immunity in rice. Plant Physiol 158: 1833–1846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleesschauwer D, Xu J, Höfte M (2014) Making sense of hormone-mediated defense networking: from rice to Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 5: 611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleesschauwer D, Yang Y, Cruz CV, Höfte M (2010) Abscisic acid-induced resistance against the brown spot pathogen Cochliobolus miyabeanus in rice involves MAP kinase-mediated repression of ethylene signaling. Plant Physiol 152: 2036–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Cao Y, Huang L, Zhao J, Xu C, Li X, Wang S (2008) Activation of the indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase GH3-8 suppresses expansin expression and promotes salicylate- and jasmonate-independent basal immunity in rice. Plant Cell 20: 228–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo C, Andrés F, Tharreau D, Iglesias DJ, Talón M (2009) Constitutive expression of OsGH3.1 reduces auxin content and enhances defense response and resistance to a fungal pathogen in rice. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22: 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Martinez C, Gusmaroli G, Wang Y, Zhou J, Wang F, Chen L, Yu L, Iglesias-Pedraz JM, Kircher S, et al. (2008) Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451: 475–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Liu H, Li Y, Yu H, Li X, Xiao J, Wang S (2011) Manipulating broad-spectrum disease resistance by suppressing pathogen-induced auxin accumulation in rice. Plant Physiol 155: 589–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Harberd NP (2003) Auxin promotes Arabidopsis root growth by modulating gibberellin response. Nature 421: 740–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T, Bailey-Serres J (2008) Submergence tolerance conferred by Sub1A is mediated by SLR1 and SLRL1 restriction of gibberellin responses in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 16814–16819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Bartolomé J, Minguet EG, Grau-Enguix F, Abbas M, Locascio A, Thomas SG, Alabadí D, Blázquez MA (2012) Molecular mechanism for the interaction between gibberellin and brassinosteroid signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 13446–13451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R, Tyagi AK, Jain M (2012) Microarray analysis reveals overlapping and specific transcriptional responses to different plant hormones in rice. Plant Signal Behav 7: 951–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauvermale AL, Ariizumi T, Steber CM (2012) Gibberellin signaling: a theme and variations on DELLA repression. Plant Physiol 160: 83–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X, Lee LYC, Xia K, Yan Y, Yu H (2010) DELLAs modulate jasmonate signaling via competitive binding to JAZs. Dev Cell 19: 884–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot B, Yao J, Montgomery BL, He SY (2014) Growth-defense tradeoffs in plants: a balancing act to optimize fitness. Mol Plant 7: 1267–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda A, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Sonoda Y, Kitano H, Koshioka M, Futsuhara Y, Matsuoka M, Yamaguchi J (2001) slender rice, a constitutive gibberellin response mutant, is caused by a null mutation of the SLR1 gene, an ortholog of the height-regulating gene GAI/RGA/RHT/D8. Plant Cell 13: 999–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRRI (1996) Standard Evaluation System for Rice, Ed 4. International Rice Research Institute, Manila, Philippines [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Tatsumi T, Sakamoto T, Otomo K, Toyomasu T, Kitano H, Ashikari M, Ichihara S, Matsuoka M (2004) A rice semi-dwarf gene, Tan-Ginbozu (D35), encodes the gibberellin biosynthesis enzyme, ent-kaurene oxidase. Plant Mol Biol 54: 533–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Sato Y, Ashikari M, Matsuoka M (2002) The gibberellin signaling pathway is regulated by the appearance and disappearance of SLENDER RICE1 in nuclei. Plant Cell 14: 57–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Sentoku N, Kitano H, Matsuoka M, Kobayashi M (2001) Cloning and functional analysis of two gibberellin 3 beta -hydroxylase genes that are differently expressed during the growth of rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 8909–8914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JDG, Dangl JL (2006) The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, An G, Ronald PC (2008) Towards a better bowl of rice: assigning function to tens of thousands of rice genes. Nat Rev Genet 9: 91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan K, Manners JM (2012) JAZ repressors and the orchestration of phytohormone crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci 17: 22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan K, Manners JM (2009) Linking development to defense: auxin in plant-pathogen interactions. Trends Plant Sci 14: 373–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q-F, Wang C, Jiang L, Li S, Sun SSM, He J-X (2012) An interaction between BZR1 and DELLAs mediates direct signaling crosstalk between brassinosteroids and gibberellins in Arabidopsis. Sci Signal 5: ra72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Van den Ende W, Rolland F (2014) Sucrose induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis is mediated by DELLA. Mol Plant 7: 570–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li F, Tang J, Wang W, Zhang F, Wang G, Chu J, Yan C, Wang T, Chu C, Li C (2012) Activation of the jasmonic acid pathway by depletion of the hydroperoxide lyase OsHPL3 reveals crosstalk between the HPL and AOS branches of the oxylipin pathway in rice. PLoS One 7: e50089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho AP, Zipfel C (2014) Plant PRRs and the activation of innate immune signaling. Mol Cell 54: 263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase K, Hirano Y, Sun TP, Hakoshima T (2008) Gibberellin-induced DELLA recognition by the gibberellin receptor GID1. Nature 456: 459–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashita H, Yasuda M, Nitta T, Asami T, Fujioka S, Arai Y, Sekimata K, Takatsuto S, Yamaguchi I, Yoshida S (2003) Brassinosteroid functions in a broad range of disease resistance in tobacco and rice. Plant J 33: 887–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro L, Bari R, Achard P, Lisón P, Nemri A, Harberd NP, Jones JDG (2008) DELLAs control plant immune responses by modulating the balance of jasmonic acid and salicylic acid signaling. Curr Biol 18: 650–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Li Y, Zhang H, Huang R, Liu W, Ming J, Liu S, Li X (2014) Expression of signalling and defence-related genes mediated by over-expression of JERF1, and increased resistance to sheath blight in rice. Plant Pathol 63: 109–116 [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Hu Y, Tang X, Zhou P, Deng X, Wang H, Guo Z (2012) Constitutive expression of rice WRKY30 gene increases the endogenous jasmonic acid accumulation, PR gene expression and resistance to fungal pathogens in rice. Planta 236: 1485–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse CM, Van der Does D, Zamioudis C, Leon-Reyes A, Van Wees SC (2012) Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 28: 489–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse CMJ, Leon-Reyes A, Van der Ent S, Van Wees SCM (2009) Networking by small-molecule hormones in plant immunity. Nat Chem Biol 5: 308–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi J, Zhou G, Yang L, Erb M, Lu Y, Sun X, Cheng J, Lou Y (2011) The chloroplast-localized phospholipases D α4 and α5 regulate herbivore-induced direct and indirect defenses in rice. Plant Physiol 157: 1987–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Liu JH, Zhao WS, Chen XJ, Guo ZJ, Peng YL (2013) Gibberellin 20-oxidase gene OsGA20ox3 regulates plant stature and disease development in rice. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 26: 227–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D, Xiao J, Ding X, Xiong M, Cai M, Cao Y, Li X, Xu C, Wang S (2007) OsWRKY13 mediates rice disease resistance by regulating defense-related genes in salicylate- and jasmonate-dependent signaling. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20: 492–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D, Xiao J, Xie W, Liu H, Li X, Xiong L, Wang S (2008) Rice gene network inferred from expression profiling of plants overexpressing OsWRKY13, a positive regulator of disease resistance. Mol Plant 1: 538–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann M, Haga K, Shimizu T, Okada K, Ando S, Mochizuki S, Nishizawa Y, Yamanouchi U, Nick P, Yano M, et al. (2013) Identification of rice Allene Oxide Cyclase mutants and the function of jasmonate for defence against Magnaporthe oryzae. Plant J 74: 226–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Seilaniantz A, Grant MR, Jones JDG (2011) Hormone crosstalk in plant disease and defense: more than just jasmonate-salicylate antagonism. Annu Rev Phytopathol 49: 26.21–26.27 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sasaki A, Itoh H, Gomi K, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Ishiyama K, Kobayashi M, Jeong DH, An G, Kitano H, Ashikari M, Matsuoka M (2003) Accumulation of phosphorylated repressor for gibberellin signaling in an F-box mutant. Science 299: 1896–1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saville RJ, Gosman N, Burt CJ, Makepeace J, Steed A, Corbitt M, Chandler E, Brown JKM, Boulton MI, Nicholson P (2012) The ‘Green Revolution’ dwarfing genes play a role in disease resistance in Triticum aestivum and Hordeum vulgare. J Exp Bot 63: 1271–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz AJ, Folsom JJ, Jikamaru Y, Ronald P, Walia H (2013) SUB1A-mediated submergence tolerance response in rice involves differential regulation of the brassinosteroid pathway. New Phytol 198: 1060–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwechheimer C. (2011) Gibberellin signaling in plants - the extended version. Front Plant Sci 2: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada A, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Sakamoto T, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Yoshida S, Sazuka T, Ashikari M, Matsuoka M (2006) The rice SPINDLY gene functions as a negative regulator of gibberellin signaling by controlling the suppressive function of the DELLA protein, SLR1, and modulating brassinosteroid synthesis. Plant J 48: 390–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono M, Sugano S, Nakayama A, Jiang C-J, Ono K, Toki S, Takatsuji H (2007) Rice WRKY45 plays a crucial role in benzothiadiazole-inducible blast resistance. Plant Cell 19: 2064–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman P, Seskar M, Kanter D, Schweizer P, Metraux JP, Raskin I (1995) Salicylic acid in rice: biosynthesis, conjugation, and possible role. Plant Physiol 108: 633–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh MP, Lee FN, Counce PA, Gibbons JH (2004) Mediation of partial resistance to rice blast through anaerobic induction of ethylene. Phytopathology 94: 819–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugano S, Jiang C-J, Miyazawa S, Masumoto C, Yazawa K, Hayashi N, Shimono M, Nakayama A, Miyao M, Takatsuji H (2010) Role of OsNPR1 in rice defense program as revealed by genome-wide expression analysis. Plant Mol Biol 74: 549–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Fan X-Y, Cao D-M, Tang W, He K, Zhu J-Y, He J-X, Bai M-Y, Zhu S, Oh E, et al. (2010) Integration of brassinosteroid signal transduction with the transcription network for plant growth regulation in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell 19: 765–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri P, Tarighi S (2010) Riboflavin induces resistance in rice against Rhizoctonia solani via jasmonate-mediated priming of phenylpropanoid pathway. J Plant Physiol 167: 201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki D, Seo S, Yamada S, Kano A, Miyamoto A, Shishido H, Miyoshi S, Taniguchi S, Akimitsu K, Gomi K (2013) Jasmonic acid and salicylic acid activate a common defense system in rice. Plant Signal Behav 8: e24260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Rong W, Luo H, Chen Y, He C (2014) The Xanthomonas campestris effector protein XopDXcc8004 triggers plant disease tolerance by targeting DELLA proteins. New Phytol 204: 595–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Matsuoka M, Kitano H, Asano T, Kaku H, Komatsu S (2006) gid1, a gibberellin-insensitive dwarf mutant, shows altered regulation of probenazole-inducible protein (PBZ1) in response to cold stress and pathogen attack. Plant Cell Environ 29: 619–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]