Abstract

Total internal reflection fluorescence-based single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements were previously carried out on the ankyrin repeat domain (ARD) of IκBα, the temporally regulated inhibitor of canonical NFκB signaling. Under native conditions, most of the IκBα molecules showed stable, high FRET signals consistent with distances between the fluorophores estimated from the crystal structures of the NFκB(RelA/p50)-IκBα complex. Similar high FRET efficiencies were found when the IκBα molecules were either free or in complex with NFκB(RelA/p50), and were interpreted as being consistent with the crystallographically observed ARD structure. An exception to this was observed when the donor and acceptor fluorophores were attached in AR3 (residue 166) and AR6 (residue 262). Surprisingly, the FRET efficiency was lower for the bound IκBα molecules (0.67) than for the free IκBα molecules (0.74), apparently indicating that binding of NFκB(RelA/p50) stretches the ARD of IκBα. Here, we conducted confocal-based single-molecule FRET studies to investigate this phenomenon in greater detail. The results not only recapitulated the apparent stretching of the ARD but also showed that the effect was more pronounced when the N-terminal domains (NTDs) of both RelA and p50 were present, even though the interface between NFκB(RelA/p50) and IκBα encompasses only the dimerization domains. We also performed mass spectrometry-detected amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDXMS) experiments on IκBα as well as IκBα bound to dimerization-domain-only constructs or full-length NFκB(RelA/p50). Although we expected the stretched IκBα to have regions with increased exchange, instead the HDXMS experiments showed decreases in exchange in AR3 and AR6 that were more pronounced when the NFκB NTDs were present. Simulations of the interaction recapitulated the increased distance between residues 166 and 262, and also provide a plausible mechanism for a twisting of the IκBα ARD induced by interactions of the IκBα proline-glutamate-serine-threonine-rich sequence with positively charged residues in the RelA NTD.

Introduction

The NFκB pathway is one of the central regulators of inflammatory responses in virtually every type of animal cell. Since its discovery almost 30 years ago (1), NFκB has been implicated in regulation of cell growth/proliferation, apoptosis, and various stress responses, and is misregulated in numerous disease states (2). NFκB exists in the resting cell as a panoply of homo- and heterodimers of the NFκB family of proteins (RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, p50, and p52) bound to members of a family of inhibitor proteins (IκBs) (3). The best-characterized inhibitor is IκBα, which binds preferentially to p50/RelA heterodimers with picomolar affinity (4). The full-length IκBα is composed of three major regions: an N-terminal signal response region of ∼70 amino acids, and ankyrin repeat domain (ARD) of ∼220 amino acids, and a C-terminal proline-glutamate-serine-threonine-rich sequence (PEST) that extends from residues 275–317 (5).

NFκB proteins have a common structural architecture that consists of a Rel-homology domain (RHD) and a transactivation domain. The RHD is composed of an N-terminal domain (NTD) followed by a short linker to the dimerization domain, which is responsible for dimerization of NFκB monomers and also serves as the binding domain for IκBs. The DNA-binding site is centered at the small linker connecting the NTD and dimerization domain, and DNA makes contacts with both the NTD and the dimerization domains when bound (6). Structural studies of the NFκB(RelA/p50)-IκBα interaction include x-ray crystal structures of the NFκB(RelA/p50)-IκBα complex, as determined by two independent groups (7, 8). The IκBα structure in the complex (shown schematically in Fig. 1 A) includes six stacked ankyrin repeats (ARs) and a C-terminal PEST. Each of these crystal structures captured only a portion of the entire complex, with the structure determined by Jacobs and Harrison (7) capturing (in one molecule of the two in the asymmetric unit) the interaction between the RelA nuclear localization signal (NLS) and the first ankyrin repeat of IκBα, and the structure determined by Huxford et al. (8) capturing the interaction between the PEST and the RelA DNA-binding region.

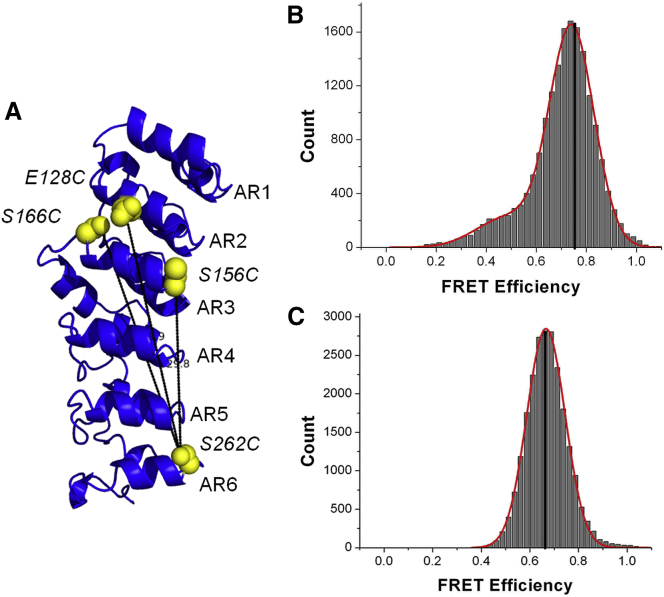

Figure 1.

(A) Model of the structure of IκBα (7, 8) showing the various sites of cysteine substitution and labeling. (B) Histogram of FRET efficiencies measured by TIRF microscopy for free IκBα labeled at positions 166 and 262. (C) Histogram of FRET efficiencies measured by TIRF microscopy for the same IκBα labeled at positions 166 and 262 but bound to the dimerization-domain-only construct of NFκB. To see this figure in color, go online.

Mass spectrometry (MS), NMR spectroscopy, and single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) studies have all revealed flexible regions in free and NFκB-bound IκBα. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange MS (HDXMS) revealed intrinsic disorder in the fifth and sixth ARs (9), and showed that this region of IκBα folds upon binding (10). NMR studies also suggested a folding-upon-binding process because although crosspeaks for AR5-AR6 were largely absent from spectra of the free protein (11), they could be observed in the bound complex despite its much larger size (12). These NMR studies also revealed that upon NFκB binding, crosspeaks in AR3 weakened, suggesting a transfer of flexibility between the AR5-AR6 region and AR3 upon complex formation (12). AR6 in free IκBα was shown by smFRET studies to fluctuate on long timescales, and these fluctuations were completely dampened by stabilizing mutations as well as upon NFκB binding (13).

By placing the donor and acceptor fluorophores at various positions, Lamboy et al. (14) were able to obtain information about the flexibility of each repeat with respect to others, and the results revealed that AR1 fluctuates in both the free and NFκB-bound states, whereas AR2 and AR4 never appear to fluctuate. Fluctuations were observed when FRET pairs were placed at AR3 and AR6, but since fluctuations were also observed when the FRET pairs were placed at AR2 and AR6, these fluctuations were attributed to fluctuation of AR6 (14).

In the initial smFRET study (14), an unexplained phenomenon was observed for IκBα molecules labeled at AR3 and AR6. The FRET efficiency of the high-FRET ensemble actually decreased from 0.74 to 0.67 upon NFκB binding (Fig. 1, B and C). This was an intriguing result because although one would have expected the increased foldedness of the NFκB-bound IκBα ARD (10) to result in a higher FRET efficiency, the opposite was observed. Assuming free rotation of the donor and acceptor fluorophore, this FRET efficiency corresponds to an increased distance of 3.3 Å between the labels upon NFκB binding. The increased distance involving AR3 is consistent with the weakening NMR peaks in AR3 upon NFκB binding, and might result from some part of AR3 cracking or becoming more dynamic in the bound state (15). On the other hand, AR3 is part of the most tightly folded segment (AR2-AR3-AR4) of the IκBα ARD, and cracking at this position would reveal a dramatic change in the folding energy distribution of the domain. To investigate this phenomenon further, we decided to perform confocal-based smFRET studies to sample shorter measurement timescales than are accessible by total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF). These studies, which used different donor and acceptor dye pairs, and were carried out in solution rather than on immobilized protein, again showed apparent ARD stretching. To investigate the role of NFκB in this phenomenon, we compared IκBα molecules in complex with either full-length NFκB or molecules containing only the dimerization domains (NFκBdd). Deletion of the NTDs results in a modest 10-fold weakening of the binding affinity from 40 to 400 pM, but still allows formation of a tightly bound complex (4). HDXMS experiments in which the effects of binding either full-length NFκB or NFκBdd were compared revealed only decreases in amide exchange throughout the ARD of IκBα. Simulations recapitulated the results of the smFRET and HDXMS experiments, suggesting that binding of NFκB induces a subtly different twist in the IκBα ARD.

Materials and Methods

IκBα purification and labeling for FRET

All seven cysteines in IκBα were replaced with serines by site-directed mutagenesis before the introduction of cysteines at positions 128 and 262 (for AR2–6), 166 and 262 (for AR3–6A), or 156 and 262 (for AR3–6B) as previously described (14). Expression and purification of the IκBα constructs were performed as described previously (9) except that expression was induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 16 h. Immediately before labeling, IκBα was passed through a size-exclusion column (S75; GE Biosciences) in labeling buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) and concentrated in a centrifugal filter unit (Vivaspin; Sartorius) to 50–100 μM. The detergent 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate was added to a 5-mM final concentration to reduce protein aggregation. Dimethyl sulfoxide was added to a 10% (v/v) final concentration to increase dye solubility during the reaction. Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine was added to a 100 μM final concentration.

In previous TIRF-based smFRET studies, the IκBα was labeled with Alexa Fluor 555 (Thermo Fisher catalog number A20346) and Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher catalog number A20347; R0 = 51 Å). For the confocal-based smFRET studies presented here, Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 dyes (Thermo Fisher catalog numbers A10254 and A10256, respectively; R0 = 60 Å) were used for compatibility with the laser and filter setup. In addition, a new sequential labeling protocol was developed to achieve higher labeling efficiencies. First, maleimide-conjugated Alexa 488 (donor fluorophore; Life Technologies) was dissolved in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide to a concentration of 1.5 mM and added to the protein solution to give a molar ratio of fluorophore/protein of 1:2. This substoichiometric labeling ratio was to minimize protein molecules with two donor fluorophores attached. The reaction mixture was protected from light and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Mono-labeled protein was separated from unlabeled and double-labeled protein on a MonoQ 5/50 GL column (GE Healthcare) using a gradient of 0–100% buffer B in 40 column volumes at a flow rate of 1 mL/min (buffer A: 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA; buffer B: 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). The mono-labeled fraction was reconcentrated to 50–100 μM and labeled as in the first reaction, but this time with maleimide-conjugated Alexa 594 (acceptor fluorophore; Life Technologies) at a fluorophore/protein ratio of 2:1. Unreacted fluorophore was removed using a PD10 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA. Fluorophore and protein concentrations were estimated by spectrophotometry at 280 nm (IκBα, εIκBα = 12950 cm−1 M−1), 488 nm (donor, εA488 = 69000 cm−1 M−1), and 594 nm (acceptor εA594 = 73000 cm−1 M−1). The absorbance at 280 nm was corrected for donor leakage of 11% and acceptor leakage of 56%. Finally, the labeled protein was purified on an S75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA to remove any aggregates that formed during labeling.

To determine whether the attached dyes were freely rotating, we performed steady-state anisotropy experiments on each IκBα protein labeled at position 128 or 262 (AR2–6), position 166 or 262 (AR3–6), or position 156 or 262 (AR3–6B) with either the donor or acceptor purified as described above. Experiments were performed on the free and NFκB-bound IκBα proteins. The average anisotropy for the Alexa Fluor 488-labeled proteins was 0.1 (ranging from 0.07 to 0.13 for the different label positions). The average anisotropy for the Alexa Fluor 594-labeled proteins was 0.18 (ranging from 0.13 to 0.19 for the different label positions). No significant differences were observed for the NFκB-bound versus free IκBαs. These values (all under 0.2) indicate free rotation of the dye under all experimental conditions. The emission intensity was also measured for the IκBα protein labeled at position 128 or 262 (AR2–6). The fluorescence intensity of the free protein did not change upon addition of either a 1.2× or 10× concentration of NFκB, indicating that the quantum yields were not affected by NFκB binding.

NFκB purification

The N-terminal hexahistidine-NFκB (His6-p5039–350/RelA19–321) full-length heterodimer was coexpressed as described previously (12) and purified by nickel affinity chromatography (Ni-NTA agarose; Qiagen, Valencia, CA), cation-exchange chromatography (Mono S column; GE Healthcare), and size-exclusion chromatography (S200; GE Healthcare). The protein concentration was determined by spectrophotometry (εNFκB = 43,760 M−1 cm−1). The N-terminal hexahistidine-NFκB (p50248–350/His6-RelA190–321) dimerization-domain heterodimer was expressed and purified in a similar manner, but with the cation-exchange chromatography omitted and the size-exclusion chromatography performed on an S75 column rather than an S200 column. The protein concentration was determined by spectrophotometry (εNFkB-dd = 22,900 M−1 cm−1).

smFRET experiments by confocal microscopy

Labeled IκBα was diluted to final concentrations of 250 pM in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA in a Tween 20-coated microscopy cuvette in the presence or absence of 2500 pM NFκB full-length or dimerization domains. Donor and acceptor fluorescence signals were recorded via simultaneous two-channel data collection with a binning time of 500 μs, using an in-house-built confocal single-molecule setup as described previously (16). The leakage of donor emission into the acceptor channel (6%) and acceptor emission due to direct excitation (4%) were taken into account. A threshold of 40 counts (the sum of signals from the two channels) was used to separate background noise from single-molecule fluorescence signals. EFRET values were calculated from the corrected donor (ID) and acceptor (IA) fluorescence intensities:

The value of γ was approximated to 1 on the basis of our previous measurements (16). FRET efficiency histograms were generated and the distributions were fitted to a Gaussian function using OriginPro 7.0 (OriginLab).

HDXMS measurements

HDXMS was performed as previously described (17, 18) with some modifications, using a Waters Synapt G2Si system with H/DX technology (Waters, Milford, MA). For initial peptide identification, the starting protein concentration was 15 μM, whereas for HDX experiments the protein concentration was 5 μM. Exchange reactions were prepared using a LEAP H/DX PAL autosampler (Leap Technologies, Carrboro, NC). The exchange reaction was initiated when 5 μL of protein (initial concentration of 5 μM) was mixed with 55 μL of deuterated buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol). For experiments in the presence of NFκBs, a 1:1 molar ratio of IκBα/NFκB dimer was used. The proteins were allowed to equilibrate at 25°C for 5 min before exchange reactions occurred (0–5 min deuteration times). Then, the exchange reactions were quenched for 2 min at 1°C using an equal volume of a solution containing 2 M GndHCl and 1% formic acid. The quenched sample was injected into a 50 μL sample loop, followed by rapid on-line pepsin digestion at 15°C using a custom-built column made with pepsin-agarose (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Rockford, IL). Peptic peptides were captured on a BEH C18 Vanguard Pre-column (Waters), separated by analytical chromatography at 1°C (ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18, 1.7 μm, 1.0 × 50 mm; Waters) with a gradient of 7–95% acetonitrile in 7 min (where both mobile phases contained 0.2% formic acid), and peptides were electrosprayed into a Synapt G2-Si quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Waters). The mass spectrometer was set to MSE-ESI+ mode for initial peptide identification and to Mobility-TOF-ESI+ mode to collect H/DX data. The mass range was set to 200–2000 (m/z), scanning every 0.4 s. Infusion and scanning every 30.0 s of leu-enkephalin (m/z = 556.277) was used for continuous lock mass correction. Peptides were identified and the MS/MS fragments were scored using PLGS 3.0 software (Waters). Peptides with a score of >7 were selected for analysis if their mass accuracy was at least 3 ppm and they were present in at least two independent runs. Deuterium uptake was determined by calculating the shift in the centroids of the mass envelopes for each peptide compared with the undeuterated controls, using DynamX 3.0 software (Waters). The amount of deuteration was corrected for back-exchange (∼34%) based on a full-deuteration control.

Molecular-dynamics simulations

All simulations were carried out using the LAMMPS simulation package (19), in which the associative memory, water-mediated, structure and energy model (AWSEM) force field, which is a transferable coarse-grained protein model, was implemented (20).

In the coarse-grained scheme of AWSEM, each amino acid residue of a protein is simplified so as to be described by three beads: Cα, Cβ, and O atoms (glycine is an exception due to its lack of a Cβ). Assuming an ideal geometry for the peptide bond, the positions of the rest of the atoms in the backbone can be calculated, so, unlike a Cα-only model, stereochemistry is quite accurate. The energy function of the standard AWSEM can be schematically written as follows:

| (1) |

In Eq. 1, Vbackbone refers to the force field that maintains backbone geometries of protein chains, and Vnonbackbone includes physically motivated potentials that reflect the protein’s chemical and/or physical properties in the context of protein secondary and/or tertiary interactions. These two energy terms are completely transferable among different proteins. The term VFM (where FM denotes fragment memory) uses the similarity in local sequence to encode local structural tendencies using structures of peptide fragments available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). In the following, we shall describe the above energy terms in more detail. Vbackbone consists of five terms (Vbackbone = Vcon + Vchain + Vχ + Vrama + Vexcl) that fix the connectivity of the chain (Vcon), the bond angles around the Cα atom (Vchain), the chirality for the correct orientations of the Cβ atoms (Vχ), the backbone dihedral angles (Vrama, Ramachandran potential), and the excluded-volume interaction (Vexcl). Note that Vcon and Vchain are functions of the distances constrained by a combination of harmonic potentials.

Vnonbackbone includes three terms (Vnonbackbone = Vcontact + Vburial + Vhelical). Vcontact refers to the contact interactions of a protein’s tertiary fold. It is defined by specifying the Cβ-Cβ distances that are far apart in sequence. The contact potential includes both direct and water (or protein)-mediated interactions between the residues. Vburial is a nonadditive potential that considers the preference of a residue to be buried inside the protein or to be exposed at the protein surface, and this preference depends on the residue type. Vhelical is associated with the propensity to form helical structure, which requires the formation of an explicit hydrogen bond between a carbonyl oxygen of residue i and an amide hydrogen of residue i+4 in the backbone. This helical propensity also depends on the residue type.

The use of VFM biases local structure to resemble the local structures of protein fragments with closely related local sequence. This term is drawn from a database of short fragments called the Fragment Memory Library. The strategy employed here has been used in various forms (21) and resembles the associative-memory Hamiltonians of neutral network models (22). The fragment memory term takes into account local steric effects of side-chain packing that are modulated by the local sequence of proteins. This form of associative memory term has been successfully combined with physically based interactions to provide de novo structure predictions of protein tertiary folds (20, 23, 24). In this study, we used only the information of the native protein itself to obtain the fragment memories, biasing/funneling the local energy landscape toward the crystal structure. Such single-memory AWSEM simulations pinpoint the effects of physical forces on the folding and binding landscapes. More detailed descriptions of all the energy terms mentioned above can be found in the original AWSEM study (20) and the supplemental information therein.

A model of the solution structure of the full-length NFκB-IκBα structure was obtained by overlaying and merging PDB files 1NFI (RelA, p50dd, and IκBα), 1IKN (RelA, p50dd, and IκBα), and 1LE9 (p50 NTD) (NFIKN). The simulation protocol was used to generate an ensemble of low-energy structures of each structure: free IκBα and two NFκB-IκBα complexes (one with only dimerization domains for RelA and p50, and one with both NTD and dimerization domains for both proteins). We adopted a micro canonical ensemble for the system, using a Langevin thermostat to control the temperature. We started from the native structure and equilibrated it at 300 K over 6 million steps. This corresponds to ∼1 μs of physical time.

Results

FRET efficiencies observed in IκBα labeled at AR3 residue 166 and AR6 residue 262 by confocal detection recapitulate TIRF measurements

We previously measured smFRET efficiencies (EFRET) in free and bound IκBα labeled at AR3 residue 166 and AR6 residue 262 (AR3–6) with Alexa Fluor 555 and Alexa Fluor 647 fluorophores. Although ∼20% of the single-molecule traces showed some fluctuation in the FRET signal, if we consider only the stable, high-FRET signal, the average EFRET in the free protein was 0.74 (Fig. 1 B; see Table 2). For the protein labeled at AR2 residue 128 and AR6 residue 262, the EFRET was 0.78 (14). Using the R0 for this dye pair of 51 Å, an EFRET of 0.74 translates to a distance of 42.8 Å, which is slightly longer than the distance between the AR3–6 cysteine sulfur atoms of 38.5 Å measured in the crystal structures of the NFκB-bound IκBα (7, 8) of the complex. This slightly longer distance is expected due to the linkers between the fluorophores and the maleimide attachment sites, which is estimated to be 5 Å based on previous modeling of similar dyes with similar linkers (25). The measured distance of 42.8 Å is therefore very close to the predicted distance for the NFκB-bound state of 43.5 Å (Table 1). The EFRET of the IκBα AR3–6 bound to NFκBdd was also measured by TIRF and found to be 0.67 (Fig. 1 C) (14), corresponding to a distance of 45.3 Å, which is ∼2.5 Å longer than in the free protein.

Table 2.

Distances from FRET Efficiencies

| Label Position (Expected FRET) | TIRF or Confocal | Observed EFRET (Free IκBα) | FREE IκBα (Å) | Observed EFRET (dd- Bound IκBα) | dd-Bound IκBα (Å) | Observed EFRET (FL-Bound IκBα) | FL-Bound IκBα (Å) | Distance dd-Bound − Free (Å) | Distance FL-Bound − Free (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR3–6 0.72 | TIRF | 0.74 | 42.8 | .67 | 45.3 | ND | ND | 2.5 | ND |

| AR3–6 0.87 | confocal | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 44.9 | .80 ± 0.05 | 47.6 | .69 ± 0.03 | 52.5 ± 2.2 | 2.7 | 7.6 |

| AR2–6 0.70 | TIRF | 0.78 | 41.7 | 0.76 | 42.1 | ND | ND | 0.4 | ND |

| AR2–6 0.86 | confocal | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 46.0 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 48.1 | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 49.5 ± 1.3 | 2.1 | 3.5 |

| AR3–6B 0.96 | confocal | 0.94 ± 0.00 | 37.9 | .95 | 36.7 | .96 | 35.3 | ND | ND |

For TIRF, Alexa Fluor 555 and Alexa Fluor 647 (R0 = 51 Å) were used. For confocal microscopy, Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594 (R0 = 60 Å) were used. Approximate distances were calculated from the EFRET, taking into consideration the different R0 values. Errors are standard errors of the mean. We performed four replicates for the free IκBα samples, two replicates for the complexes with NFκB(dd), and four replicates for the complexes with NFκB(FL). Replicates were performed on different days and prepared from different labeled proteins. The expected distance was calculated from the NFκB-bound IκBα crystal structure (PDB ID: 1IKN).

Table 1.

Distances and Expected FRET Efficiencies of Donor-Acceptor Pairs

| Label Position | Label Position | Crystallographic Distance (Å)a | Expected EFRET (TIRF) | Expected EFRET (Confocal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 166 (AR3) | 262 (AR6) | 43.5 | 0.72 | 0.87 |

| 128 (AR2) | 262 (AR6) | 44.3 | 0.70 | 0.86 |

| 156 (AR3)2 | 262 (AR6) | 34.8 | 0.91 | 0.96 |

The crystallographic distance was calculated by measuring the distance between the side-chain sulfurs and then adding 5 Å according to information from Kalinin et al. (25).

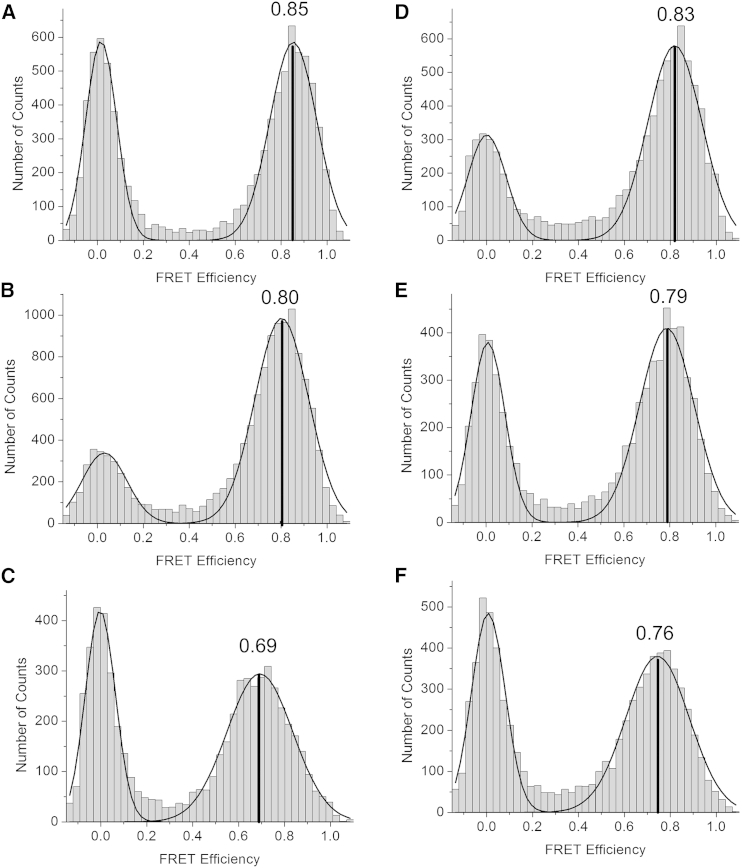

To investigate this phenomenon further and to obtain more statistically significant data, we carried out confocal studies using a different dye pair and optimizing labeling efficiencies (see Materials and Methods). Whereas several hundred molecules are typically measured using TIRF approaches, data from several thousand molecules are typically obtained in confocal-based measurements. Using the Alexa 488-Alexa 594 dye pair (R0 = 60 Å), the EFRET measured for the free IκBα labeled at the same residues as before (residue 166 in AR3 and residue 262 in AR6 (AR3–6)) was 0.85 ± 0.03, corresponding to a distance of 44.9 ± 1.7 Å (Fig. 2 A; Table 2). Upon binding of the dimerization-domain-only construct of NFκB, EFRET gradually decreased to 0.80 ± 0.05, and it further decreased to 0.69 ± 0.03 upon binding of full-length NFκB (Fig. 2, B and C; Table 2). Therefore, the distance between the FRET dye pair in IκBα (AR3–6) increased from 44.9 Å to 52.5 ± 2.2 Å, an increase of 7.6 Å upon binding of full-length NFκB.

Figure 2.

(A–F) FRET efficiency histograms determined by confocal microscopy for (A) free IκBα labeled at 166 and 262 (AR3–6), (B) IκBα (AR3–6) bound to dimerization-domain-only NFκB, (C) IκBα (AR3–6) bound to full-length NFκB, (D) Free IκBα labeled at 128 and 262 (AR2–6), (E) IκBα (AR2–6) bound to dimerization-domain-only NFκB, and (F) IκBα (AR2–6) bound to full-length NFκB.

In previous NMR experiments, we observed a weakening of crosspeaks for some residues in AR3 upon NFκB binding (12). Since residue 166 was near the region where we observed weakening crosspeaks, we made an effort to label AR3 at a different site. The only site that could be labeled resulting in stable protein was residue 156. The distance between this residue and residue 262 in AR6 was much shorter, only 29.8 Å. We completed a full confocal FRET study on this labeled protein, both bound and free; however, the observed EFRET was always 0.95. Since the distance was so short, the FRET was, as expected, insensitive to small distance changes.

Comparison of IκBα labeled at AR2 (residue 128) versus AR3 (residue 166) and AR6 (residue 262)

To determine whether this perceived stretching extended to AR2, we also measured the EFRET of bound and free IκBα labeled at AR2 (residue 128) and AR6 (residue 262). In this case, the EFRET of the free IκBα was 0.83 ± 0.01 (Fig. 2 D), corresponding to a distance of 46.0 ± 0.55 Å (Fig. 2 A; Table 2). Again, we observed a gradual decrease in EFRET (to 0.79 ± 0.01) upon binding of the dimerization-domain-only construct of NFκB, and it further decreased (to 0.76 ± 0.02) upon binding of full-length NFκB (Fig. 2, E and F). Therefore, the distance between the FRET dye pair in IκBα (AR2–6) increased from 46.0 Å to 49.5 ± 1.3 Å, an increase of 3.5 Å upon binding of full-length NFκB. Thus, an apparent stretching was also observed from AR2 to AR6, although it was not quite as pronounced as for AR3–6. We note that the TIRF measurements were only performed with the dimerization-domain-only construct of NFκB, and no significant difference in EFRET was previously reported for the AR2–6 labeled protein (13).

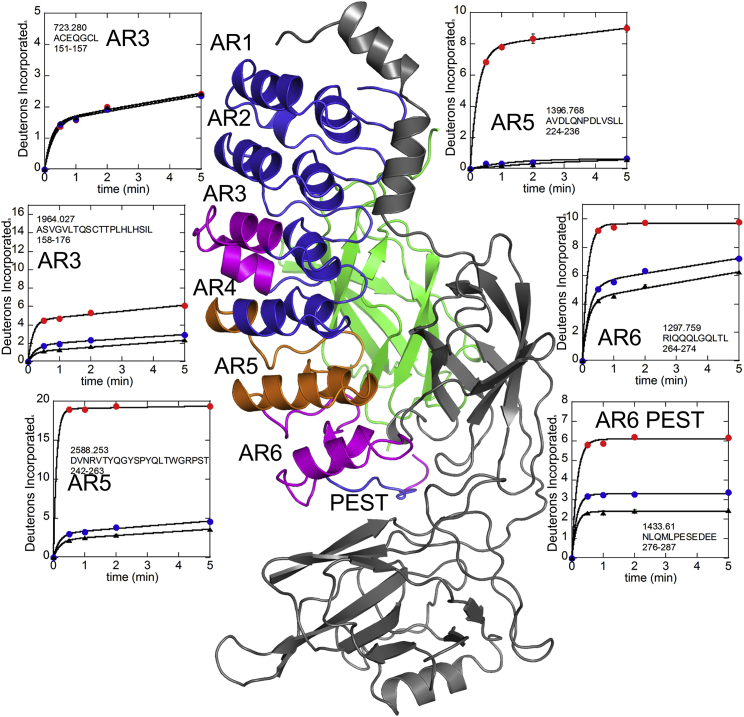

Observation by HDXMS of changes in amide exchange upon stretching of IκBα

Given the weakening crosspeaks in AR3 observed by NMR upon NFκB binding (12), we thought it likely that the perceived stretching was the result of dynamic local unfolding of some part of the IκBα ARD. To test this hypothesis, we measured amide exchange in IκBα using HDXMS. We previously reported HDXMS results for free and NFκB-bound IκBα detected by MALDI-TOF, but in those experiments we did not obtain coverage of key regions of AR3 (9, 10). Here, using a Synapt G2Si instrument run in Mobility-TOF mode, we were able to achieve nearly 100% sequence coverage (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). The data collected on the Synapt were completely consistent with previous results (Fig. S2) but also revealed subtle differences in exchange of NFκB-bound IκBα. In particular, residues 158–176 in AR3, residues 242–276 in AR6, and residues 278–287 (the PEST region) showed decreased exchange in the presence of the dimerization-domain-only constructs, but an even greater decrease in exchange in the presence of the full-length NFκB (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Deuterium-uptake plots for some regions of IκBα. Residues 151–157 showed identical uptake in free IκBα (red circles) and both NFκB-bound forms (full-length (black triangles) and dimerization-domain-only (blue circles)). Residues 158–176 showed decreased amide exchange upon NFκB binding, which was more pronounced upon binding of full-length NFκB. Residues 224–236 (in AR5) showed decreased amide exchange upon NFκB binding, which was not sensitive to the form of NFκB. Several overlapping peptides encompassing the PEST region revealed that only the very C-terminal acidic residues sensed the form of NFκB that was bound.

Molecular-dynamics simulations suggest two possible causes of the increased distance between residues 166 and 262: d166–262

To probe the structural details of the NFκB-IκBα complex, we performed coarse-grained molecular-dynamics simulations using the AWSEM energy function, which is known to accurately predict protein monomer and dimer structures (20, 26). The speed and accuracy of the coarse-grained model allow the widest exploration of conformational space, where twisting and/or stretching of the entire folded structure might not otherwise be visible due to the limited sampling available with all-atom approaches.

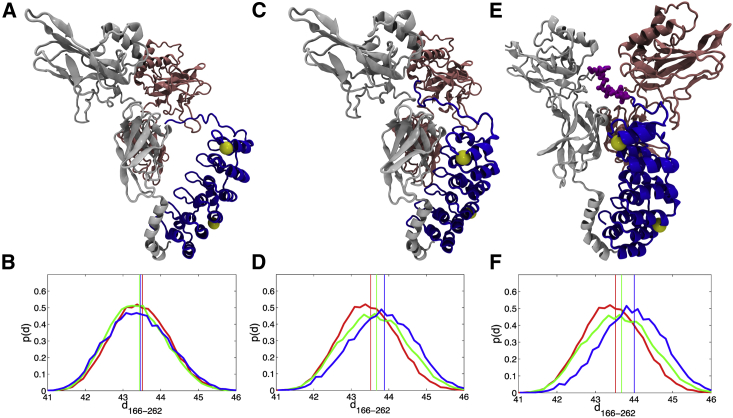

Consistent with the trend we observed in the experiments, the distance between the Cβ atoms of residues 166 and 262 (d166–262) varies when the binding partner differs. The interaction between the dimerization domain of NFκB and repeats 3–6 of IκBα contributes partly to the increase of d166–262. When IκBα is bound to the NLS region but not tightly bound to the dimerization domain, the distributions of d166–262 are almost identical to that of the free IκBα (Fig. 4, A and B). When IκBα is tightly bound to both the NLS and the dimerization domain (as assessed by Qinterface > 0.6), the mean distance between the residues to which the FRET dyes are attached becomes longer for IκBα bound to the dimerization-domain-only NFκB and even longer when it is bound to full-length NFκB (Fig. 4, C and D). This further stretch is pronounced in the subset of molecules in which the PEST region is interacting with the NFκB RelA NTD (Fig. 4, E and F).

Figure 4.

Representative structures from AWSEM simulations of the NFκB-IκBα complex. IκBα, blue; RelA, light gray; p50 pink. The yellow spheres show the location of the Cβ atoms of residues 166 and 262. (A) Structures with <60% native interfacial contacts formed compared with the crystal structure were selected. (B) The probability distributions of the distance between the Cβ atoms of residues 166 and 262 were calculated from the subset of structures in (A) for free IκBα (red), IκBα bound to dimerization-domain-only NFκB (green), and IκBα bound to full-length NFκB (blue), respectively. The vertical lines indicate the mean values of each distribution; d166–262 was calculated by adding 5 Å to the measured distance between the Cβ atoms of residues 166 and 262. (C) Structures with >60% interfacial contacts formed were selected. (D) The probability distributions of d166–262 for the subset of structures in (C) are plotted in three different colors according to the same scheme as in the previous panel. (E) Structures in which the PEST region (colored magenta) was interacting with RelA were selected. (F) The probability distributions of d166–262 for the subset of structures in (E) are plotted in three different colors according to the same scheme as in the previous panel. The probability distribution for the subset of structures in which the PEST was interacting with the p50 NTD was almost identical to the green curve shown in (D).

Discussion

Converting smFRET results into molecular distances is an inexact science, but progress is being made, particularly when the FRET dye pairs are attached to the macromolecule by relatively long linkers, and when relative distances are compared based on multiple attachment sites, as we did in this study. Here, we also compared measurements obtained by TIRF microscopy and confocal microscopy. For TIRF-based experiments, the molecules are immobilized (27) and generally fewer molecules are interrogated for longer periods of time. In confocal-based studies, the molecules remain in solution (28) and more molecules can be interrogated, but for much shorter times. Typically, better statistics can be obtained from confocal measurements (29). By comparing data from confocal and TIRF-based smFRET approaches, we were able to achieve improved confidence in our observations. Despite the use of different dye pairs, different solution conditions, and different microscopy-based approaches, a surprising decrease in EFRET values between dye pairs in IκBα labeled at AR3 and AR6, and to some extent also between AR2 and AR6, was observed upon NFκB binding in every experiment. The observed decrease in EFRET was consistent with an increased distance of >5 Å between the dye pairs upon full-length NFκB binding. It is interesting to compare the distances calculated from measured EFRET values with the distance between the labeling sites estimated from the crystal structures of the NFκB-IκBα complex (7, 8). Estimates for the average distance between the dye and the labeling site were obtained for similar dyes with similar linkers via molecular-dynamics simulations (25, 30). Surprisingly, the distance estimates obtained from the crystal structures were closer to the distances calculated from the EFRET values measured in free IκBα than to those measured in bound IκBα. The distances measured in the IκBα bound to full-length NFκB were longer than what seemed possible based on the crystal structure. Thus, it appears that the IκBα ARD adopts a structure that is more extended than that observed in the crystal structures. It is interesting to speculate that because the molecules were packed end-on-end in the crystals, crystal-packing forces may have compacted the structure. In addition, only the RelA NTD was present in the crystal structures. Indeed, molecular-dynamics simulations predicted that the most stable structure would have a different twist and bend of the ARD, resulting in a longer distance between the dye pairs than was calculated from the starting model based on crystal structures (7, 8) (Fig. 4).

To examine whether the stretching involved local unfolding of AR3, as we previously predicted (12), we measured amide exchange in free and NFκB-bound IκBα. The HDXMS results showed no evidence of local unfolding of AR3. In fact, binding of NFκB caused a decrease in amide exchange in AR3, and this decrease was more pronounced upon binding of full-length NFκB. Taken together, the results suggest that binding of NFκB subtly alters the structure of IκBα, perhaps causing a slight twisting or bending of the ARD to increase the distance between the N-terminal repeats (AR2 and AR3) and AR6. As previously reported, AR5 and AR6 showed dramatically decreased amide exchange upon binding of NFκB (10). The decrease in amide exchange within AR5 was the same regardless of whether the NFκB was full length or consisted of only the dimerization domains. In contrast, AR6 showed a larger decrease in amide exchange upon binding of full-length NFκB as compared with the dimerization-domain-only construct (Fig. 3). We previously observed that mutations within IκBα AR5 and AR6 result in chemical-shift changes in AR3 (11). Thus, it appears that the exact structure of AR3 is sensitive to the conformational state of AR5 and AR6. Indeed, our molecular-dynamics model of the lowest-energy conformation of NFκB-bound IκBα shows deviations from the starting structure mostly in AR3 and AR6.

The binding affinity of the complex between IκBα and full-length NFκB(RelA/p50) is extremely high: 40 pM at 37°C and immeasurably tight at 25°C (4). Nearly all of this binding affinity is due to interactions with the dimerization domains of the RelA/p50 heterodimer. Deletion of the NTDs weakens the binding to 400 pM (4). Even though the NTDs only contribute 10-fold to the binding affinity, they appear to contribute to the final bound structure of IκBα as assessed by HDXMS data. We previously showed that IκBα AR5 and AR6 have fully exchangeable amides in the free protein, but NFκB binding dramatically decreases amide exchange, indicative of folding on binding (10). We now show that additional decreases in amide exchange in IκBα AR3, AR5, and AR6 are observed when the NFκB NTDs are present. Thus, amide exchange appears to be a sensitive readout for optimal folding of the IκBα ARD. If we use amide exchange as a readout of protein foldedness, our results are consistent with the idea that optimal folding of the entire IκBα ARD is only achieved upon binding of full-length NFκB, which perhaps would explain why optimal binding affinity also requires full-length NFκB. The notion that optimal folding throughout the IκBα ARD is required for optimal binding is consistent with the hypothesis that the energy of folding the IκBα ARD contributes to the very high binding energy of the complex (31).

According to the simulations, the optimal twist/stretch of the IκBα ARD in the solution structure of the NFκB-IκBα complex appears to be attained upon interaction of AR3–6 with the dimerization domain, as well as upon interaction of the PEST region with the NTD of NFκB RelA. Both interactions contribute to the final tightly bound structure, which recapitulates the observations from the smFRET data. NMR evidence suggested a direct interaction between the negatively charged DEE residues in the PEST region and the positively charged residues R30 and R33 in the RelA NTD (32). The configuration of the PEST region changes dramatically between the starting model and the energy-optimized model of the NFκB-IκBα complex. It is likely that crystal-packing forces and the absence of the p50 NTD in the crystal structures both contribute to the fact that the PEST-NTD interaction was not observed crystallographically. We are pursuing a combination of molecular-dynamics simulations, cryo-electron microscopy, and small-angle x-ray scattering experiments to obtain a better understanding of the complete structure of the NFκB-IκBα complex in solution.

Acknowledgments

The Waters Synapt G2Si instrument used in these experiments was provided by the NIH through project 1S10OD016234-01. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (1PO1-GM71862), NSF (grant MCB 1121959 to A.A.D.), and the Bullard-Welch Chair at Rice University (C-0016). T.C.L. was supported by a scholarship from the Kwanjeong Educational Foundation, South Korea. M.B.T. was additionally supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation (R18-A11217) and the Carlsberg Foundation (2012_01_0369).

Editor: Elizabeth Rhoades.

Footnotes

Morten Beck Trelle’s present address is Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Two figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)00007-2.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Baeuerle P.A., Baltimore D. Activation of DNA-binding activity in an apparently cytoplasmic precursor of the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Cell. 1988;53:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar A., Takada Y., Aggarwal B.B. Nuclear factor-kappaB: its role in health and disease. J. Mol. Med. 2004;82:434–448. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0555-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann A., Baltimore D. Circuitry of nuclear factor kappaB signaling. Immunol. Rev. 2006;210:171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergqvist S., Croy C.H., Komives E.A. Thermodynamics reveal that helix four in the NLS of NF-kappaB p65 anchors IkappaBalpha, forming a very stable complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;360:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baeuerle P.A., Baltimore D. I kappa B: a specific inhibitor of the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Science. 1988;242:540–546. doi: 10.1126/science.3140380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen F.E., Huang D.B., Ghosh G. Crystal structure of p50/p65 heterodimer of transcription factor NF-kappaB bound to DNA. Nature. 1998;391:410–413. doi: 10.1038/34956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs M.D., Harrison S.C. Structure of an IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex. Cell. 1998;95:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huxford T., Huang D.B., Ghosh G. The crystal structure of the IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex reveals mechanisms of NF-kappaB inactivation. Cell. 1998;95:759–770. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croy C.H., Bergqvist S., Komives E.A. Biophysical characterization of the free IkappaBalpha ankyrin repeat domain in solution. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1767–1777. doi: 10.1110/ps.04731004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truhlar S.M., Torpey J.W., Komives E.A. Regions of IkappaBalpha that are critical for its inhibition of NF-kappaB.DNA interaction fold upon binding to NF-kappaB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18951–18956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605794103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cervantes C.F., Handley L.D., Komives E.A. Long-range effects and functional consequences of stabilizing mutations in the ankyrin repeat domain of IκBα. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:902–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sue S.C., Cervantes C., Dyson H.J. Transfer of flexibility between ankyrin repeats in IkappaB∗ upon formation of the NF-kappaB complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;380:917–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamboy J.A., Kim H., Komives E.A. Visualization of the nanospring dynamics of the IkappaBalpha ankyrin repeat domain in real time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:10178–10183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102226108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamboy J.A., Kim H., Komives E.A. Single-molecule FRET reveals the native-state dynamics of the IκBα ankyrin repeat domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:2578–2590. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreiro D.U., Walczak A.M., Wolynes P.G. The energy landscapes of repeat-containing proteins: topology, cooperativity, and the folding funnels of one-dimensional architectures. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreon A.C., Gambin Y., Deniz A.A. Interplay of alpha-synuclein binding and conformational switching probed by single-molecule fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5645–5650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809232106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wales T.E., Fadgen K.E., Engen J.R. High-speed and high-resolution UPLC separation at zero degrees Celsius. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:6815–6820. doi: 10.1021/ac8008862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dembinski H., Wismer K., Komives E.A. Predicted disorder-to-order transition mutations in IκBα disrupt function. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:6480–6485. doi: 10.1039/c3cp54427c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plimpton S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular-dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 1995;117:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davtyan A., Schafer N.P., Papoian G.A. AWSEM-MD: protein structure prediction using coarse-grained physical potentials and bioinformatically based local structure biasing. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:8494–8503. doi: 10.1021/jp212541y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedrichs M.S., Wolynes P.G. Toward protein tertiary structure recognition by means of associative memory Hamiltonians. Science. 1989;246:371–373. doi: 10.1126/science.246.4928.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopfield J.J. Neurons with graded response have collective computational properties like those of two-state neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:3088–3092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.10.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papoian G.A., Ulander J., Wolynes P.G. Water in protein structure prediction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3352–3357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307851100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegler J.A., Lätzer J., Wolynes P.G. Restriction versus guidance in protein structure prediction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15302–15307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907002106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalinin S., Peulen T., Seidel C.A. A toolkit and benchmark study for FRET-restrained high-precision structural modeling. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:1218–1225. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng W., Schafer N.P., Wolynes P.G. Predictive energy landscapes for protein-protein association. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:19244–19249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216215109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ha T., Enderle T., Weiss S. Probing the interaction between two single molecules: fluorescence resonance energy transfer between a single donor and a single acceptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:6264–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deniz A.A., Dahan M., Schultz P.G. Single-pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer on freely diffusing molecules: observation of Förster distance dependence and subpopulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:3670–3675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deniz A.A., Laurence T.A., Weiss S. Single-molecule protein folding: diffusion fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies of the denaturation of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:5179–5184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090104997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakon J.J., Weninger K.R. Detecting the conformation of individual proteins in live cells. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:203–205. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreiro D.U., Komives E.A. Molecular mechanisms of system control of NF-kappaB signaling by IkappaBalpha. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1560–1567. doi: 10.1021/bi901948j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sue S.C., Dyson H.J. Interaction of the IkappaBalpha C-terminal PEST sequence with NF-kappaB: insights into the inhibition of NF-kappaB DNA binding by IkappaBalpha. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;388:824–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.