The cognitive limit for reading a metropolitan map was estimated to be on the order of 8 bits—a limit already exceeded by some large cities.

Keywords: networks, mutlilayer networks, transportation, urban navigation

Abstract

Cities and their transportation systems become increasingly complex and multimodal as they grow, and it is natural to wonder whether it is possible to quantitatively characterize our difficulty navigating in them and whether such navigation exceeds our cognitive limits. A transition between different search strategies for navigating in metropolitan maps has been observed for large, complex metropolitan networks. This evidence suggests the existence of a limit associated with cognitive overload and caused by a large amount of information that needs to be processed. In this light, we analyzed the world’s 15 largest metropolitan networks and estimated the information limit for determining a trip in a transportation system to be on the order of 8 bits. Similar to the “Dunbar number,” which represents a limit to the size of an individual’s friendship circle, our cognitive limit suggests that maps should not consist of more than 250 connection points to be easily readable. We also show that including connections with other transportation modes dramatically increases the information needed to navigate in multilayer transportation networks. In large cities such as New York, Paris, and Tokyo, more than 80% of the trips are above the 8-bit limit. Multimodal transportation systems in large cities have thus already exceeded human cognitive limits and, consequently, the traditional view of navigation in cities has to be revised substantially.

INTRODUCTION

The number of “megacities”—urban areas in which the human population is larger than 10 million—has tripled since 1990 (1). New York City (NYC), one of the first megacities, reached that level in the 1950s, and the world now has almost 30 megacities, which together include roughly half a billion inhabitants. The growth of such large urban areas usually also includes the development of transportation infrastructure and an increase in the number and use of different transportation modes (2, 3). For example, about 80% of the cities with human populations larger than 5 million have a subway system (4). This leads to a natural question: Is navigating transportation systems in very large cities too difficult for humans (5)? Moreover, how does one quantitatively characterize this difficulty?

It has long been recognized that humans have intrinsic cognitive limits for processing information (6). In particular, it has been suggested that an individual can maintain relationships only on the order of 150 stable relationships (7, 8). This “Dunbar number” was first proposed in the 1990s by the British anthropologist Robin Dunbar by extrapolating results about the correlations of brain sizes with the typical sizes of social groups for various primates. Although it is still controversial, these results have been supported by subsequent studies of, for example, traditional human societies (9) and microblogging (10).

When navigating for the first time between two unfamiliar places and having a transportation map as one’s only support, a traveler has to compare different path options to find an optimal route. In contrast to the schematization of partially familiar routes (11), here a traveler does not need to simultaneously visualize the whole route; it is sufficient to identify and keep track of the position of the connecting stations on a map. Therefore, a first important point to consider is that humans can track information for a maximum of about four objects in their visual working memory (12). This implies that a person can easily keep in mind the key locations (origin, destination, and connection points) for trips with no more than two connections (which corresponds exactly to four different points). In addition, recent studies on visual search strategies (13, 14) have shown a transition in search strategies between the simple cases of the Stuttgart and Hong Kong metropolitan networks and the case of Paris, which has one of the most complicated transportation networks in the world. The time needed to find a route in a transportation network grows with the complexity of its map, and the pattern of eye fixations also changes from following metro lines to a random scattering of eye focus all over the map (13). A similar transition from directional to isotropic random search has been observed for the visual search of hidden objects with an increasing number of distractors (15). The ability to manage complex “mental maps” is thus limited, and only extensive training on spatial navigation can push this limit with morphological changes in the hippocampus (16). Human-constructed environments have far exceeded these limits, and it is interesting to ask whether there is a navigation analog for the Dunbar number and whether there exists a cognitive limit to human navigation ability such that it becomes necessary to rely on artificial systems to navigate in transportation systems in large cities. If such a cognitive limit exists, what is it? In this paper, we answer this question using an information-processing perspective (6) to characterize the difficulty of navigating in urban transportation networks. We use a measure of “information search” associated with a trip that goes from one route to another (17). In most networks, many different paths connect a pair of nodes, and one generally seeks a fastest available path (which is not necessarily unique) that minimizes the total time to reach a destination. However, it tends to be more natural for most individuals to instead consider a “simplest path,” which has the minimal number of connections (see Fig. 1) (18).

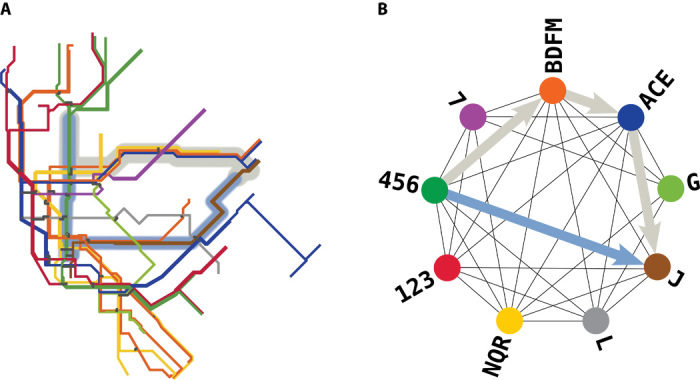

Fig. 1. Fastest and simplest paths in primal and dual networks.

(A) In the primal network of the New York City (NYC) metropolitan system, a simplest path (light blue) from 125th Street on line 5 (dark green) to 121st Street on line J (brown) differs significantly from a fastest path (gray). There is only one connection for the above simplest path (Brooklyn Bridge–City Hall/Chambers Street) in Lower Manhattan. In contrast, the above fastest path needs three connections (5→F→E→J). We compute the duration of this path using travel times from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Data Feeds (see Materials and Methods). We neglect walking and waiting times. (B) In the dual space, nodes represent routes [where ACE, BDFM, and NQR are service names (49)], and edges represent connections. A “simplest path” in the primal space is defined as a shortest path with the minimal number of edges in the dual space (light-blue arrow). It has a length of C = 1 and occurs along the direct connection between line 5 (dark-green node) and line J (brown node). The above fastest path in the primal space has a length of C = 3 (gray arrows) in the dual space, as one has to change lines three times. [We extracted the schematic of the NYC metropolitan system from a map that is publicly available on Wikimedia Commons (45).]

Rosvall et al. (17) proposed a measure for the information needed to encode a shortest path from a route s to another route t. However, the amount of necessary information can depend strongly on the initial and final nodes, and we consider a trip from an origin node i in route s to a destination node j in route t. This trip is embedded in real space; among all of the possible simplest paths (17), we pick a fastest path p(i, s; j, t), which can differ from an actual fastest path between i and j (see Fig. 1A). In computing the travel time of a trip, we neglect the contribution of walking and waiting times (2). However, the choice of a simplest path already tends toward the minimization of such transfer costs, which strongly influence a traveler’s decisions (19).

The total information needed for determining a fastest simplest path is

| (1) |

where p(i, s; j, t) is the sequence of routes needed for connecting i in route s to j in route t. The term ks is the number of routes connected to s. At each node along a path, n ∈ p(i, s; j; t), with n ≠ t, and one has a choice between kn − 1 routes. The idea behind Eq. 1 is that when tracking a trip along a map (with the eyes or a finger), the connections that one has to exclude represent—similarly to the number of distractors in visual search tasks (15)—the information that has to be processed and thus temporarily stored in working memory (20). One can therefore construct the measure of entropy (Eq. 1) as a proxy for the accumulated cognitive load that is associated with a trip, and it is analogous to the total amount of load experienced during a task (21). For this reason, this measure of entropy seems to be appropriate for estimating the information limit associated with the observed transition in the visual search strategy (13, 15).

From a map user’s perspective, the existence of several alternative simplest paths is not necessarily a significant factor, as one only needs a single simplest path for successful transportation from the origin to the destination. Consequently, we use the entropy in Eq. 1 rather than the one proposed by Rosvall et al. (17). (See Materials and Methods for further discussion.) To produce a single summary statistic for a path, we average S(i, s; j, t) over all nodes i ∈ s and j ∈ t (we denote this mean using brackets 〈 · 〉) to obtain

| (2) |

which is the main quantity that we use to describe the complexity of a trip (see fig. S1) and which will allow us to extract an empirical upper limit to the information that humans are able to process for navigating.

RESULTS

We use the measure to characterize the complexity of the 15 largest urban metropolitan systems in the world. From these results, we extract an empirical upper limit (about 8 bits) to the information that humans are able to process for navigating. We then apply this threshold in calculations for multimodal transportation networks and demonstrate that most trips in large cities exceed human cognitive limits.

Information threshold

The values of in a network tend to grow with the number C of connections that appear in a simplest path, as well as with the mean degree 〈k〉 of the nodes in the dual space (see figs. S2 and S3). Note that the latter is related to the total number of connections in a network. Adding new routes can thus have a negative impact from the perspective of information. Although new routes can be useful for shortening the simplest paths for some (s,t) pairs, new connections simultaneously increase the mean degree of a network and can make it more difficult to navigate in a network. We thus want to estimate the maximal possible information that an individual can reasonably process to navigate in a transportation system. For that purpose, we consider the 15 largest metropolitan networks in the world (with respect to having the most stations). The characteristics of metropolitan networks were examined in previous papers (4, 22–27), and navigation strategies have been considered in transportation networks (28–30). For each network, we consider the shortest simplest paths with C = 2 connections. This corresponds to paths that use three different lines: such a path starts from a source route s, connects to an intermediate route r, and then connects to a destination route t. There are two distinct reasons for this choice: (i) visual working memory has a limit of four objects (12), and (ii) in most of the 15 cities, two connections correspond to the diameter of the dual network. From a map user’s perspective, after having checked that each pair of consecutive stations is connected by a direct line, the locations to keep in mind are the origin, the destination, and the connecting stations. These nodes correspond to the places that one has to “highlight” on a map to record the trajectory. The capacity of visual working memory thus allows one to easily keep in mind only trajectories with two connections, leading to a total of four stations. The value 2 is also the diameter of the dual network in most of the metropolitan systems. In such situations, all pairs of nodes can be connected by paths with at most two connections, staying below the working memory limit of humans.

In Fig. 2A, we show the cumulative distribution of entropies for these two-connection paths. We find that the NYC metropolitan system is the largest and most complex metropolitan system in the world; it has a maximal value of Smax ≈ 8.1 ≈ log2(274) bits. The Paris transportation system reaches a similar value when one takes into account the light rail and tramway system in the multilayer metro-rail-tramway (MRT) network displayed in the official metro map (31).

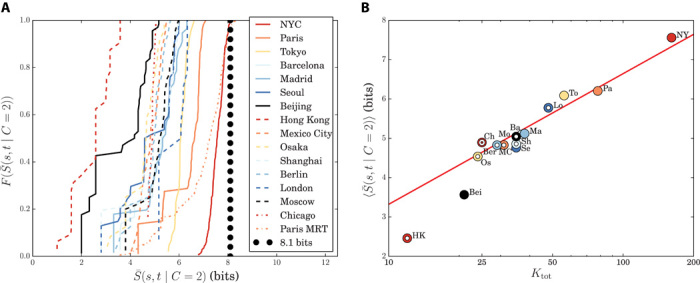

Fig. 2. Information threshold.

(A) Cumulative distribution of the information needed to encode trips with two connections in the 15 largest metropolitan networks. The largest value occurs for the NYC metropolitan system (red solid curve), which has trips with a maximum of Smax ≈ 8.1 bits. Among the 15 networks, the Hong Kong (red dashed curve) and Beijing (black solid curve) metropolitan networks have the smallest number of total connections and need the smallest amount of information for navigation. The Paris MRT (Metropolitan, Light Rail, and Tramway) network (orange dashed-dotted curve) from the official metro map (33) includes three transportation modes (which are managed by two different companies) and reaches values that are similar to those for the (larger) NYC metropolitan system. (B) Information threshold versus total number of connections in the dual space. This plot illustrates that the average amount of information needed to encode trips with two connections is strongly correlated with the total number of connections in the dual network, as can be predicted for a square lattice (see Materials and Methods). See table S1 for the definitions of the abbreviations. The color code is the same as in (A), and the red solid line represents the square-lattice result . This relationship permits one to associate the information threshold Smax with the cognitive threshold , which one can interpret as the maximum number T of intraroute connections that can be represented on a map.

Navigation in such large networks is not trivial (14), and an eye-movement behavioral transition has been observed in systems that are too large (that is, when there are too many connections) (13). The value Smax for trips with two connections thus provides a natural limit above which human cognitive capabilities are challenged and for which it becomes extremely difficult to find a simplest path. We thus make the reasonable choice to take Smax as the cognitive limit for public transportation: humans need an information entropy of to be able to navigate in a network successfully without assistance from information-technology tools.

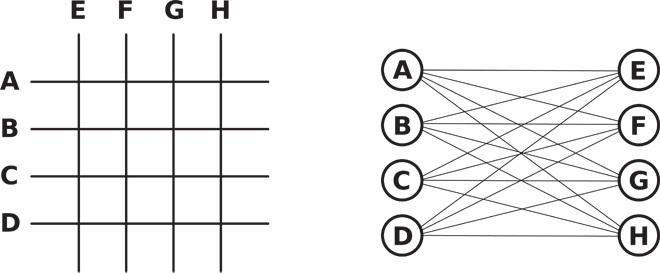

To gain a physical understanding of the cognitive limit Smax, we estimate for a regular lattice (similar to the one in Fig. 3) with N lines that are each connected with N/2 other lines (that is, kr = N/2 for all r). This choice of a lattice is justified by the results presented by Roth et al. (4), indicating that most large metropolitan transportation networks consist of a core set of nodes with branches radiating from it. The core is rather dense and has a peaked degree distribution, so it is reasonable to use a regular lattice for comparison. In the dual space of the regular lattice, the degree ks of route s is equal to N/2. For a path from route s through route r to route t, we thus obtain

| (3) |

where 〈k〉 denotes the mean degree. The last equality in Eq. 3 comes from the relation for the total degree of a regular lattice: . The key quantity for understanding Smax is therefore the total number of undirected connections in the dual space (see table S1). As we indicated in Eq. 3, this is identical to the square of the mean degree 〈k〉2 in a lattice. For Paris, for example, we obtain 〈k〉 ≈ 9.75, which leads to 9.752 ≈ 95 connections for the corresponding lattice. The actual Paris metropolitan network has a total of 78 connections, and the difference comes from the fact that the real network is not a perfectly regular lattice. At this stage, it is important to make two remarks. First, the apparently paradoxical fact that the total information grows with size for regular lattices while, intuitively, the complexity of finding a path stays constant is specific to the case in which there is an “algorithm” to find the route. Indeed, in perfectly regular rectangular (that is, Cartesian) grids, one needs to make at most two turns to find a desired route. Second, drawing a parallel with an individual navigating a bifurcating tree from the root to a terminal node while traversing eight bifurcation points (and thus 255 internal nodes), the value of 8 bits as a limit appears to be consistent with Miller’s “magic number” (6, 32). This “Miller law” also limits the number of binary decisions that can be memorized in sequence to a value that has been observed to be about 7 ± 2.

Fig. 3. Primal (left) and dual (right) networks for a square lattice.

In this example, the lattice has N = 8 routes. Each route has k = N/2 = 4 connections, so the total number of connections is Ktot = k2 = 16. In the dual network, the four east–west routes (A to D) and the four north–south routes (E to H) yield a graph with a diameter of 2.

In Fig. 2B, we test Eq. 3 with the 15 largest metropolitan networks. Our calculation shows that the total degree in the dual space, which is related to the total number of connections in a network, is the main factor for understanding the information entropy of these systems. We also test this relation for the temporal evolution of the Paris metropolitan network, and we show that the number of connections scales as (N/2)2 for the historical growth from N = 1 to N = 14 routes (see fig. S4). Equation 3 allows us to translate the information limit of 8 bits into a limit on the number T of intraroute connections S = log2(T). The value of T also corresponds to the number of distractors to be excluded for the most complex trips (with C(s,t) = 2). This process of exclusion thus demands progressive information integration, which causes cognitive overload. Evidence for the existence of such a cognitive threshold is the change in search strategy observed in eye-tracking experiments (13, 15). The value T ≈ 250 represents the worst-case scenario in the world’s largest metropolitan network (i.e., in NYC). It thus overestimates the values at which the transition occurs. Indeed, the Paris MRT network, for which the strategy change was observed in Burch et al. (13), has Ktot ≈ 162. The quantity T has a similar order of magnitude as the Dunbar number, an extensively studied cognitive limit for the size of a friendship circle and which seems to lie in the range between 100 and 200. See Gonçalves et al. (10) for a recent discussion of this topic.

Effects of multimodal couplings on the information

In our discussion above, we estimated the cognitive threshold for the most complex paths in the 15 largest metropolitan networks. We now consider the effects of including other transportation modes (for example, buses and trams). The effects of intermodal coupling are significant (2, 33), and the natural framework is a multilayer network (34, 35), which associates each transportation mode with a different “layer” in a network and where interchanges (that is, connection points) between different modes are represented by interlayer edges. As we discussed in Materials and Methods, a major difficulty is obtaining data for different modes for a given city, as this type of data is not easily available. However, we were able to combine multiple data sources for large cities on three different continents: NYC, Paris, and Tokyo (see table S2).

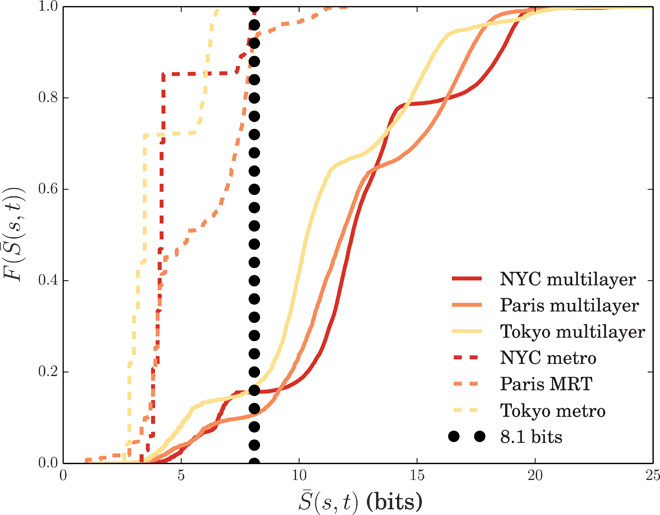

The distribution of is a superposition of peaks associated with different values of C (see fig. S2). By comparing the distribution of for the (monolayer) bus network and the full multilayer transportation network, we can distinguish two competing effects of multimodality: (i) it tends to reduce the number C of connections and thereby reduces , and (ii) it increases because new routes increase the node degrees in the dual space (see fig. S3). However, these two contributions do not compensate for each other. In Fig. 4, we show the cumulative distribution of information entropy values for the NYC, Paris, and Tokyo multimodal (that is, multilayer) transportation systems. We present the corresponding probability densities in fig. S5.

Fig. 4. Information entropy of multilayer networks.

The solid curves represent the cumulative distributions of for multilayer networks that include a metro layer for NYC, Paris, and Tokyo. (We associate one layer with bus routes and another layer with metro lines.) Most of the trips require more information than the cognitive limit Smax ≈ 8.1. The fractions of trips under this threshold are as follows: 15.6% for NYC, 10.7% for Paris, and 16.6% for Tokyo. The dashed curves are associated with all possible paths in a metro layer. In this case, the amount of information is always under the threshold, except for Paris, which includes trips with C = 3 (see table S3). Note that the threshold value lies in a relatively stable part of all three cumulative distributions, suggesting that our results are robust with respect to small variations of the threshold.

We find that fewer than approximately 17% (we obtain this maximum value for Tokyo) of the trips are below the threshold Smax. These results imply that more than 80% of the trajectories in the complete public transportation networks of these major cities require more information than the most complicated trajectory in the largest metropolitan networks. As shown in the Supplementary Materials, the other 20% corresponds to pairs of nodes for which a trip has essentially one connection (for NYC) or at most two connections (for Paris and Tokyo), as the simplest paths that carry a small amount of information are those that avoid traversing too many major hubs (see table S4 and fig. S6). The number of connections acting as distractors in the case of the Paris MRT is already so large that it has a crucial impact on route search [it takes roughly 30 s, on average, for such a search (14)], and the complexity of the bus layer (and therefore of the coupled metropolitan and bus system) will therefore exceed human cognitive capacity. Consequently, traditional maps that represent all existing bus routes have a very limited utility. This result thus calls for a user-friendly way to present and use bus routes. For example, unwiring some bus-bus connections lowers the information and leads to the idea that a design centered around the metro layer could be efficient. However, further work is needed to reach an efficient, “optimal” design from a user’s perspective.

Finally, someone can choose to take a simplest path that is not necessarily also a shortest path. When extracting information from a map, an individual is performing a task based on a heuristic. Such a heuristic could limit the set of objects and details that receive focused attention. This, in turn, limits the set that is perceived and remembered (36). For example, one can try to find an optimal path by separately considering different transportation modes. This approach may be cognitively easier than considering all modes, though the price to pay for such a strategy includes a greater chance of settling for a suboptimal trajectory (which is neither simplest nor shortest), as an optimal trajectory is, by definition, computed on a full multilayer transportation network.

DISCUSSION

Human cognitive capacity is limited, and cities and their transportation networks have grown to a point that they have reached a level of complexity that is beyond humans’ processing capability to navigate in them. In particular, the search for a simplest path becomes inefficient when multimodality is important and when a transportation system has too many interconnections. This occurs because interconnections play two crucial roles in the search for a path: they are both targets and distractors. The identification of possible interchange points is a key and extremely time-consuming process in a route-finding task (13). As with the case of hidden objects (15), one can represent the difficulty of the search using the number of distractors, which for a map are all possible interchanges. We have found that, in the largest cities, the addition of bus routes with maps that are already too complicated to be used easily by travelers implies that the cognitive limit to urban navigation is exceeded for multimodal transportation systems.

We have estimated the cognitive threshold value to be on the order of T ≈ 250 connections (that is, approximately 8 bits), which represents the worst-case scenario for the most complex trips in the largest metropolitan networks. This exceeds the behavioral transition, beyond which humans have difficulty navigating on their own (15). This result has some experimental support (13, 14), and we hope that our paper will encourage more experimental investigations to achieve a better understanding of how the complex content of multilayer networks limits the unassisted use of available information.

The quantity T has a similar interpretation and a similar order of magnitude as the Dunbar number, and our results can thus be construed as evidence to suggest the existence of a “transportation Dunbar number” for processing complex maps. Although the value of T represents an upper bound, it allows us to demonstrate the existence of a huge gap between the amount of information that humans can easily process (Ktot ≲ 250) and the actual amount of information on multimodal transportation networks in large cities (Ktot ≳ 1800; see table S2). Indeed, the growth of transportation systems has yielded networks that are so entangled with each other and so complicated that a visual representation on a map becomes too complex and ultimately useless. Our results imply that maximizing the number of intersections between lines, which minimizes transfers, is contrary to the goal of having an easily usable transportation system. The information-technology tools provided by companies and transportation agencies to help people navigate in transportation systems will soon become necessary in all large cities. Our analysis highlights the fact that humans need to integrate an excessive amount of information for urban navigation, and we therefore need to seek new solutions that will help them navigate in megacities. Redesigning maps and representations of transportation networks (37), as well as improving information-technology tools (38) that help to decrease the amount of information to a level below the human processing threshold, thus appears to be crucial for an efficient use of services provided by transportation agencies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data for the world’s 15 largest metropolitan transportation networks

The data that we used were extracted from Wikipedia and can be found online (39). The data describe the lines in the metropolitan networks as they were in 2009 and were used in a previous publication (4). The data for each metropolitan system yield a spatial network (40). Each station has geographical coordinates, and the edges connect consecutive stations on a metro line. The diagnostic that we used to determine a shortest simplest path is the sum of the traveling times between stops.

Paris

The data that we used to construct the Paris multilayer transportation network (34, 35) were obtained from the Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens (RATP) (41) and the Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Français (SNCF) (42). Both data sets are in GTFS (General Transit Feed Specification) format. We extracted the bus layer from RATP data. To reproduce all of the information available in the Paris Metro map (31), we merged the metro and tramway data from the RATP with the light rail and tramway data from the SNCF. This aggregation yielded what we call the “MRT” layer, which we used as a single metro layer. We distinguished services that went in opposite directions or toward different branches, and we were able to identify them as a particular route because they shared the same short name. We used the services that were available on 26 May 2014 (a Monday), and we excluded any bus route that was completely subsumed by another route.

The RATP data provide extremely detailed transfer times between stops. We used this information to reconstruct connections between routes. With the exception of connections in the central station Châtelet–Les Halles, we ignored transfers that take longer than 8 min and considered the two corresponding nodes as different entities. By studying the cumulative distribution for the walking distances in these connections data, we found that the 99th percentile corresponds roughly to dw = 250 m. More precisely, F(250 m) ≈ 0.986. Motivated by this calculation, we allowed a maximum walking distance of dw = 250 m for the coarse-graining procedure that we needed to construct the multilayer networks in NYC and Tokyo.

The transfer data for Paris allow a more accurate method than the data for NYC and Tokyo. We constructed a transfer network in which (i) a transfer is defined between two stops and (ii) two stops are located in the same geographical position. We associated a single node with each connected component of the transfer network, and each isolated stop constitutes a single node. We weighted the edges using travel times. Relatively large connection areas emerged from our choices. They correctly reflect possible choices on the Paris Metro map that are suggested to travelers (31). Intrastation walking paths are represented as white edges.

Finally, we also coupled nodes if they were closer than dw = 250 m to each other and either (i) they both came from the RATP data and were labeled with the same name or (ii) at least one node came from the SNCF data (where transfer times between lines were not provided). Intraroute connections are possible if routes share the same node. A trip length is equal to the sum of the mean travel times between consecutive stops.

New York City

We constructed the NYC multilayer network with data from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Data Feeds (43), which provide a snapshot of their services on different days using the GTFS format (44). We used the services that were available on 1 December 2014 (a Monday). For the metro layer, we excluded six routes [which correspond to services (45)] that represent shuttles or other special services.

For the bus layer, we integrated the data from the five NYC boroughs with the multiborough data from the subsidiary MTA Bus Company. We performed a coarse-graining procedure in which (i) we coupled bus stops to metro locations if they lie within a walking distance of dw = 250 m and then (ii) combined bus stops into a single entity if the distance between them is less than dw. We therefore allowed intraroute connections if two routes share the same stop (where coupled stops count as a single stop). As with Paris, a trip length is given by the sum of the mean travel times between consecutive stops. We extracted the NYC metro schematic of Fig. 1 from a map that is publicly available in Wikimedia Commons (46).

Tokyo

The Tokyo metro data set, which we extracted from Wikipedia and can be found online (39), allowed us to study another of the world’s largest metropolitan networks. The bus data for Tokyo (for 2010) are provided freely by the Japanese Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism (47). We used only the Toei bus lines (48), which serve central Tokyo.

This data set associates stops with bus routes but gives no information on the topology of the line. We reconstructed an approximate topology by generating a minimal spanning tree (49) among all stops of a route. We defined the intraroute connections using the same coarse-graining procedure as for NYC. We again combined nodes that are within a walking distance of dw = 250 m from each other. We had no information on the travel times along the edges, so we estimated them from the trip length and used typical transportation speeds from the bus and metropolitan systems in the Paris data. Because one can approximate each layer’s speed using a log-normal distribution, we used the log average as the typical speed associated with each mode of transportation. The values that we found were vB ≈ 14.0 km/hour for the bus layer and vM ≈ 23.4 km/hour for the metro layer.

Definitions of paths and information entropy

From the perspective of information processing, one can quantify the difficulty of navigating in an urban transportation network using a measure of “search information” S (17). This measure represents the amount of information that is needed to encode a path from a route s to a route t that follows a simplest path. We defined “simplest path” as a shortest path in the dual space of a transportation network. In the present context, “dual space” [which is also sometimes called an “information network” (17)] is the network in which the nodes represent routes and the edges represent possible intersections (or connections between different lines) among those routes. There can be many degenerate simplest paths between two routes, and one can define the information entropy computed on these paths to be (17)

| (4) |

where the set {p(s,t)} includes all D(s,t) degenerate simplest paths between a route s and a route t. The quantity ks indicates the total number of connections that emanate from a route s. On a path, one has a choice between kn − 1 routes (that is, excluding the route from which the path emanates).

When one is seeking an optimal trajectory, degeneracy is not necessarily a significant factor, and we focused on a trip from a node i to another node j in real space. Among all of the degenerate simplest paths, we picked a shortest one p(s, t, i, j) and considered its entropy

| (5) |

Averaging over all nodes i ∈ s and j ∈ t yields the main quantity that we used in the main text

| (6) |

In theory, it is also possible to weight this mean using real flows. Unfortunately, for this particular case, traditional data sources are insufficient, as they tend to describe the mobility of commuters, who do not necessarily rely on maps for their daily journeys.

If we assume that all of the degenerate paths contribute equally to the entropy, then we obtain the following approximate relation between the entropies

| (7) |

Deviations from the (approximate) equality (7) indicate differences between the various degenerate paths (see fig. S7).

From a map user’s perspective, the existence of several alternative simplest paths is not necessarily a significant factor, as one only needs a single simplest path for successful transportation from an origin to a destination. The natural choice is a fastest simplest path, which is generally unique for real values of travel times. Consequently, we used the entropy in Eq. 1 rather than the one proposed by Rosvall et al. (17).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Kivelä for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We thank P. Brodersen, F. Corradi, A. Solé Ribalta, and the anonymous reviewers for useful comments. R.G. thanks L. Alessandretti for suggesting the use of SNCF data. M.B. thanks Y. Shibata for helping to find and process the Tokyo data. Funding: All authors were supported by the European Commission FET-Proactive project PLEXMATH (grant 317614). Author contributions: R.G., M.A.P., and M.B. performed and designed the research. R.G. wrote the codes for data analysis and prepared the figures. R.G., M.A.P., and M.B. wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2/2/e1500445/DC1

Table S1. Network characteristics of the largest connected component for the 15 largest metropolitan systems in the world.

Table S2. Network characteristics of the Bus-Metro multilayer networks.

Table S3. Structure of the simplest paths in three metropolitan systems.

Table S4. Percentages of paths with with C = 1 and C = 2 connections.

Fig. S1. Examples of paths with growing .

Fig. S2. Entropy distribution for MRT layer, bus layer, and complete multilayer transportation network in Paris.

Fig. S3. Effects of multiplexity.

Fig. S4. Growth of the Paris metropolitan network.

Fig. S5. Information entropy of multilayer transportation networks.

Fig. S6. Dual-space degree of low-information starting points for paths with C = 2 in the Tokyo multilayer network.

Fig. S7. Empirical validation of Eq. 7.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.United Nations World Urbanization Prospects, www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/population/world-urbanization-prospects-2014.html [accessed 10 January 2015].

- 2.Gallotti R., Barthelemy M., Anatomy and efficiency of urban multimodal mobility. Sci. Rep. 4, 6911 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.L. Alessandretti, M. Karsai, L. Gauvin, User-based representation of time-resolved multimodal public transportation networks. ArXiv:1509.08095 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Roth C., Kang S. M., Batty M., Barthelemy M., A long-time limit for world subway networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 2540–2550 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts M. J., Newton E. J., Lagattolla F. D., Hughes S., Hasler M. C., Objective versus subjective measures of Paris Metro map usability: Investigating traditional octolinear versus all-curves schematics. Int. J. Hum. Comput. St. 71, 363–386 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller G. A., The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol. Rev. 101, 343–352 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunbar R. I. M., Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. J. Hum. Evol. 22, 469–493 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saramäki J., Leicht E. A., López E., Roberts S. G. B., Reed-Tsochas F., Dunbar R. I. M., Persistence of social signatures in human communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 942–947 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunbar R. I. M., Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behav. Brain Sci. 16, 681–694 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonçalves B., Perra N., Vespignani A., Modeling users’ activity on Twitter networks: Validation of Dunbar’s number. PLOS One 6, e22656 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.S. Srinivas, S. C. Hirtle, Knowledge based schematization of route directions, Spatial Cognition V—Reasoning, Action, Interaction (Springer, Berlin, 2007), pp. 346–364. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luck S. J., Vogel E. K., The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature 390, 279–281 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.M. Burch, K. Kurzhals, M. Raschke, T. Blascheck, D. Weiskopf, How do people read metro maps? An eye tracking study. Proceedings of First Workshop on Schematic Mapping, https://sites.google.com/site/schematicmapping/Burch-EyeTracking.pdf (2014).

- 14.M. Burch, K. Kurzhals, D. Weiskopf, Visual task solution strategies in public transport maps, Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Eye Tracking for Spatial Research, Vienna, Austria, 23 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Credidio H. F., Teixeira E. N., Reis S. D. S., Moreira A. A., Andrade J. S. Jr, Statistical patterns of visual search for hidden objects. Sci. Rep. 2, 920 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maguire E. A., Gadian D. G., Johnsrude I. S., Good C. D., Ashburner J., Frackowiak R. S. J., Frith C. D., Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4398–4403 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosvall M., Trusina A., Minnhagen P., Sneppen K., Networks and cities: An information perspective. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 028701 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viana M. P., Strano E., Bordin P., Barthelemy M., The simplicity of planar networks. Sci. Rep. 3, 3495 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wardman M., Public transport values of time. Transp. Policy 11, 363–377 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baddeley A., Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 829–839 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paas F., Tuovinen J. E., Tabbers H., Van Gerven P. W. M., Cognitive load measurement as a means to advance cognitive load theory. Educ. Psychol. 38, 63–71 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latora V., Marchiori M., Is the Boston subway a small-world network? Physica A 314, 109–113 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angeloudis P., Fisk D., Large subway systems as complex networks. Physica A 367, 553–558 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee K., Jung W.-S., Park J. S., Choi M. Y., Statistical analysis of the Metropolitan Seoul Subway System: Network structure and passenger flows. Physica A 387, 6231–6234 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derrible S., Kennedy C., The complexity and robustness of metro networks. Physica A 389, 3678–3691 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rombach M. P., Porter M. A., Fowler J. H., Mucha P. J., Core-periphery structure in networks. SIAM J. App. Math. 74, 167–190 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louf R., Roth C., Barthelemy M., Scaling in transportation networks. PLOS One 9, e102007 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S. H., Holme P., Exploring maps with greedy navigators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 128701 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann T., Lambiotte R., Porter M. A., Decentralized routing on spatial networks with stochastic edge weights, Phys. Rev. E 88, 022815 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Domenico M., Solé-Ribalta A., Gómez S., Arenas A., Navigability of interconnected networks under random failures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 8351–8356 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.RATP, www.ratp.fr/informer/pdf/orienter/f_plan.php [accessed 14 January 2015].

- 32.Baddeley A., The magical number seven: Still magic after all these years? Psychol. Rev. 101, 353–356 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris R. G., Barthelemy M., Transport on coupled spatial networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 128703 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kivelä M., Arenas A., Barthelemy M., Gleeson J. P., Moreno Y., Porter M. A., Multilayer networks. J. Complex Netw. 2, 203–271 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boccaletti S., Bianconi G., Criado R., del Genio C. I., Gómez-Gardeñes J., Romance M., Sendiña-Nadal I., Wang Z., Zanin M., The structure and dynamics of multilayer networks. Phys. Rep. 544, 1–122 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simons D. J., Chabris C. F., Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception 28, 1059–1074 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Transport For London, Bus Spider Maps, https://tfl.gov.uk/maps_/bus-spider-maps [accessed 4 June 2015].

- 38.De Domenico M., Lima A., González M. C., Arenas A., Personalized routing for multitudes in smart cities. EPJ Data Sci. 4, 1 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39.QuantUrb, www.quanturb.com/data.html [accessed 19 June 2015].

- 40.Barthélemy M., Spatial networks. Phys. Rep. 499, 1–101 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 41.RATP, http://data.ratp.fr/ [accessed 20 January 2016].

- 42.SNCF, http://files.transilien.com/horaires/gtfs/ [accessed 1 October 2014].

- 43.MTA, http://web.mta.info/ [accessed 29 November 2014].

- 44.Google Developers, https://developers.google.com/transit/gtfs/ [accessed 15 January 2014].

- 45.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_New_York_City_Subway_stations_in_Manhattan#Lines_and_services (see the table “Lines and services”) [accessed 22 January 2016].

- 46.Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NYC_subway-4D.svg [accessed 30 January 2015].

- 47.GIS, http://nlftp.mlit.go.jp/ksj-e/gml/datalist/KsjTmplt-P11.html [accessed 1 October 2014].

- 48.Toei, www.kotsu.metro.tokyo.jp/eng/ [accessed 15 January 2014].

- 49.J. Clark, D.A. Holton, A First Look at Graph Theory (Vol. 1) (World Scientific, Teaneck, NJ, 1991), 348 pp. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2/2/e1500445/DC1

Table S1. Network characteristics of the largest connected component for the 15 largest metropolitan systems in the world.

Table S2. Network characteristics of the Bus-Metro multilayer networks.

Table S3. Structure of the simplest paths in three metropolitan systems.

Table S4. Percentages of paths with with C = 1 and C = 2 connections.

Fig. S1. Examples of paths with growing .

Fig. S2. Entropy distribution for MRT layer, bus layer, and complete multilayer transportation network in Paris.

Fig. S3. Effects of multiplexity.

Fig. S4. Growth of the Paris metropolitan network.

Fig. S5. Information entropy of multilayer transportation networks.

Fig. S6. Dual-space degree of low-information starting points for paths with C = 2 in the Tokyo multilayer network.

Fig. S7. Empirical validation of Eq. 7.