Abstract

Brugia malayi is a parasitic nematode that causes lymphatic filariasis in humans. Here the solution structure of the forkhead DNA binding domain of Brugia malayi DAF-16a, a putative ortholog of Caenorhabditis elegans DAF-16, is reported. It is believed to be the first structure of a forkhead or winged helix domain from an invertebrate. C. elegans DAF-16 is involved in the insulin/IGF-I signaling pathway and helps control metabolism, longevity, and development. Conservation of sequence and structure with human FOXO proteins suggest that B. malayi DAF-16a is a member of the FOXO family of forkhead proteins.

Keywords: Brugia malayi, forkhead box, winged helix, FOXO, FOXO1, FOXO3a, FOXO4, DAF-16, Caenorhabdtis elegans, insulin-signaling pathway, filariasis

Introduction

Filarial parasites are nematodes that cause debilitating disease in humans and domestic animals. The human parasite Brugia malayi is transmitted by mosquitoes and is one of the causative agents of lymphatic filariasis. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, transmittance of infective stage (third stage, iL3) larvae from mosquitoes to a human host triggers a molt to the fourth larval stage (L4)1. Following a final molt, adult males and females accumulate in the lymphatic system. Disease symptoms are caused primarily by the body’s immune response against the parasites and their Wolbachia endosymbionts2. The Global Programme for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis has made impressive strides towards breaking the transmission cycle through mass drug administration with ivermectin, albendazole and diethylcarbamzine3. However, evidence of drug resistance is beginning to emerge4. Understanding the development of the parasite, particularly what controls the iL3 to L4 molt when the infective stage first enters the human host, may lead to drug or vaccine targets.

The iL3 stage in parasitic nematodes is considered to be analogous to the dauer developmental stage in the well-studied free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans5. In harsh conditions (lack of food, high temperature, high crowding), C. elegans enter the dauer stage, an alternative to the normal third larval stage6. Dauer larvae have a thick, highly resistant cuticle, they do not feed, and their metabolism is altered to allow them to remain in stasis until an environmental signal triggers resumption of normal development (molting to the L4 stage)6. In addition to both being third stage larvae, both iL3 and dauer also require an environmental signal in order to molt5. Several signaling pathways are known to regulate the dauer decision, including an insulin-signaling pathway7. Specifically, CeDAF-16 proteins are phosphorylated by AKT and SGK-1 kinases when insulin signaling is active7. When phosphorylated, CeDAF-16 binds to the 14-3-3 protein FTT-2 and is localized to the cytoplasm7. Unphosphorylated CeDAF-16 is active and localized to the nucleus where it regulates target genes through binding to forkhead response elements (FREs). CeDAF-16 is active during dauer formation and is inactivated by insulin signaling during dauer recovery. Parasitic nematodes may also use the insulin-signaling pathway to molt from the infective stage to the L4 stage on entry into a mammalian host. For example, the Ancylostoma caninium DAF-16 and Strongyloides stercoralis FKTF-1 (DAF-16) were able to rescue daf-16 mutant phenotypes in C. elegans8,9 and a dominant negative form of FKTF-1 disrupted morphogenesis of infective stage larvae10.

A putative daf-16 ortholog exists in B. malayi. Bm-daf-16 encodes at least two isoforms, Bm-daf-16a and Bm-daf-16b, which are alternatively spliced at the 5’ end. Deep sequencing11 and quantitative Real Time PCR (Garland, B. and Crossgrove, K., unpublished) show that Bm-daf-16 is expressed in all life cycle stages tested (adults, microfilaria, iL3 and L4), though isoform specific assays have not been conducted. The DNA binding domain encoded by Bm-daf-16a exhibits 81% amino acid identity to the C. elegans DAF-16a protein, while the Bm-daf-16b DNA binding domain is 92% identical to C. elegans DAF-16b. While the two Bm-daf-16 isoforms, and their homologous C. elegans isoforms, differ at the N-terminus of the DNA binding domain, they share the predicted DNA recognition helix and are predicted to form functional forkhead domains. NMR and X-ray crystallography studies of forkhead box domain containing proteins, like human forkhead box-O (FOXO) proteins FOXO1, FOXO3a and FOXO4, have demonstrated each has the conserved winged helix or forkhead box DNA binding domain structure containing three to four α-helicies, a three stranded β-sheet and two unstructured wings12. Human FOXO proteins have been intensely studied due to their therapeutic potential13. However, to date no structural studies have been done on invertebrate FOXO proteins. Here we describe the solution structure of residues 342-442 of Bm-DAF-16a (Uniprot ID A8QCW6) and show that it forms a canonical forkhead box-O DNA binding domain.

Materials and Methods

Undergraduates, as a part of independent research courses, completed the majority of this work.

Protein purification

DNA coding for an SMT3-Bm-DAF-16a (residues 342-442) fusion protein was cloned into the Bam-HI and Hind-III sites of pQE30. The UniProt ID for Bm-DAF-16a is A8QCW6. Protein was expressed in Escherichia coli strain SG13009 containing pLacIRARE for expression of LacI and expression of tRNAs for overcoming codon bias. Cells were grown at 37°C in 1L of Luria broth or [U-15N/13C] M9 minimal medium to an OD600 of 0.6, at which time expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. After 5 hours, cell pellets were collected by centrifugation (4,000 × g for 30 min) and stored at −20°C until processing. Cells were resuspended and lysed by sonication in Buffer A (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 10mM imidazole, pH 8.0) containing 0.1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol and 1 mM phenylmethanylsulfonyl fluoride. The insoluble protein inclusion body containing His6-SMT3-Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) was collected by centrifugation (15,000 × g for 15 min) and dissolved in buffer AD (6 M guanidine HCl, 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 0.1% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 8.0). After clarification by centrifugation (15,000 × g for 15 min), the supernatant was loaded onto ~2 mL of His60 nickel resin for 30 min. The column was washed with 40 mL buffer AD. The His6-SMT3-Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) fusion protein was eluted using 30 mL of buffer BD (6 M guanidine HCl, 100 mM sodium acetate, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 4.5). The His6-SMT3-Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) was refolded through dialysis against 4 L of refolding buffer (20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) at 4°C. After 24 hours, 400 μg of His6-ubiquitin-like protease 1 (His6-Ulp-1) fusion was added to the dialysis bag, which was then transferred to a fresh 4 L of refolding buffer for an additional 24 hours of dialysis. To separate the His6-Ulp-1 and His6-SMT3 from the Bm-DAF-16a (342-442), the dialysate was applied to 2 mL of His60 nickel resin. The flow through and three, 10 mL buffer A washes containing Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) were collected, concentrated and buffer exchanged using ultrafiltration (MWCO 3500) into 20 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl at either pH 6.0 or 7.4. The molecular weight of Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) was confirmed using a Voyager-DE Pro MALDI-TOF spectrometer (measured 11654.77 m/z, expected 11655.9 m/z).

Forkhead response element binding

Although the DNA sequence of forkhead response elements (FREs) to which Bm-DAF-16a binds in B. malayi are not known, purified Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) was incubated with a biotin-labeled FRE for the DAF-16 transcription factor from C. elegans14 in a mobility shift assay. Mobility shift assays were performed using the Lightshift EMSA kit (Thermo Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Specifically, reactions contained 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 μg dI/dC, 2.5% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40, 5 μg purified protein and 40 fmol of biotin labeled probe. Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes, electrophoresed at 100V on prerun 6% acrylamide in 0.5X TBE and transferred to Hybond N (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in 0.5X TBE at 100V for 30 minutes. Detection followed manufacturer’s instructions for the Lightshift EMSA kit. To generate probe, primers Bm-daf-16-13: 5’ GATCAAGTAAACAACTATGTAAACAA 3’) and Bm-daf-16-14 (5’ GATCTTGTTTACATAGTTGTTTACTT 3’) were labeled using the DNA 3’ End Biotinylation Kit (Thermo Scientific). Equimolar amounts were then mixed together, heated to 95°C for 1 min and allowed to cool to room temperature for 1 hour. The same approach was used to generate a negative control probe that lacked any known FRE sequence (5’ GATCCTTTGACCTAGTGACCTAGTTG 3’ and 5’ GATCCAACTAGGTCACTAGGTCAAAG 3’).

Structure determination

All NMR measurements were acquired at 25°C at the Medical College of Wisconsin’s NMR facility on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryoprobe. The NMR sample consisted of 500 μM [U-15N/13C] Bm-DAF-16a (342-442), 20 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, 10 % D2O, 0.2 % NaN3, pH 6.0. All NMR data were processed using NMRPipe15. Standard NMR techniques were used for generating chemical shift assignments16. Assignments were 97.3% complete; unassigned protons are listed in Table I. Distance restraints were generated from three-dimensional 15N-edited NOESY-HSQC, 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC, and 13C(aromatic)-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra (τmix= 80 ms). TALOS+ was used to generate backbone dihedral angle constraints17. The torsion-angle dynamics program CYANA 3.0, including the NOEASSIGN module, was used to calculate the Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) structural ensemble18. The 20 lowest energy conformers of 100 calculated were further refined in explicit water solvent19. Table I lists the structure validation statistics from the PSVS suite20. The structure and chemical shift assignments for BmDAF-16a (342-442) were submitted to the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 2MBF) and the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB ID 19398). Heteronuclear NOE spectra were obtained using the Bruker hsqcnoef3gpsi pulse program.

Table I.

Structure statistics for 20 BmDAF-16a conformers (PDB ID 2MBF, BMRB ID 19398).

| Completeness of resonance assignments (%) a | 97.3% | |

|

| ||

| Constraints | ||

|

| ||

| Non-redundant distance constraints | ||

| Total | 2954 | |

| Intraresidue [i=j] | 1771 | |

| Sequential [ (i−j)=1] | 455 | |

| Medium [1<(i−j)≤5] | 415 | |

| Long | 313 | |

| Dihedral angle constraints (ϕ and ψ) | 114 | |

|

| ||

| Constraints per residue | ||

|

| ||

| Average number of constraints per residue | 30 | |

|

| ||

| Constraint Violations | ||

| Average number of distance constraint violations per structure | ||

| 0.1–0.2 Å | 18.15 | |

| 0.2–0.5 Å | 1.85 | |

| > 0.5 Å | 0 | |

| Average R.M.S. distance violation per constraint (Å) | 0.02 | |

| Maximum distance violation (Å) | 0.36 | |

| Average number of dihedral angle violations per structure | ||

| 1–10° | 9.55 | |

| > 10° | 0 | |

| R.M.S. dihedral angle violation per constraint (°) | 0.62 | |

| Maximum dihedral angle violation (Å) | 4.9 | |

|

| ||

| Average atomic R.M.S.D. to the mean structure (Å) | ||

|

| ||

| Residues 342–406 | ||

| Backbone ( Cα, C′, N) | 0.42 ± 0.07 | |

| Heavy atoms | 0.89 ± 0.09 | |

|

| ||

| Deviations from idealized covalent geometry b | ||

|

| ||

| Bond lengths | R.M.S.D. (Å) | 0.015 |

| Torsion angle violations | R.M.S.D. (°) | 1.2 |

|

| ||

| Lennard-Jones energy c (kJ mol−1) | −2180 ± 80 | |

|

| ||

| Ramachandran statistics (% of all residues) d | ||

|

| ||

| Most favored | 95.1 | |

| Additionally allowed | 4.9 | |

| Generously allowed | 0.1 | |

| Disallowed | 0 | |

Missing chemical shifts include: H of Asn342; Hζ of Phe 374; Hα and Qβ of Ser 386; H of Gln 387; Hδ1 and Hε1 of His 399; H, Hδ1 and Hε1 of His 400; H of Ser 405; Hε3 and Hζ3 of Trp 420; and H of Trp 421.

Final X-PLOR27 force constants were 250 (bonds), 250 (angles), 300 (impropers), 100 (chirality) and 100 (omega), 50 (NOE constraints), and 200 (torsion angle constraints). Idealized covalent geometry is from Engh and Huber28.

Nonbonded energy was calculated in XPLOR-NIH29.

Values are from PROCHECK-NMR30

Characterization of the oligomeric state of Bm-DAF-16a

A Zorbax GF-450 column operated with 200 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4 at a flow rate of 1 mL per minute was used for gel filtration.

Results and Discussion

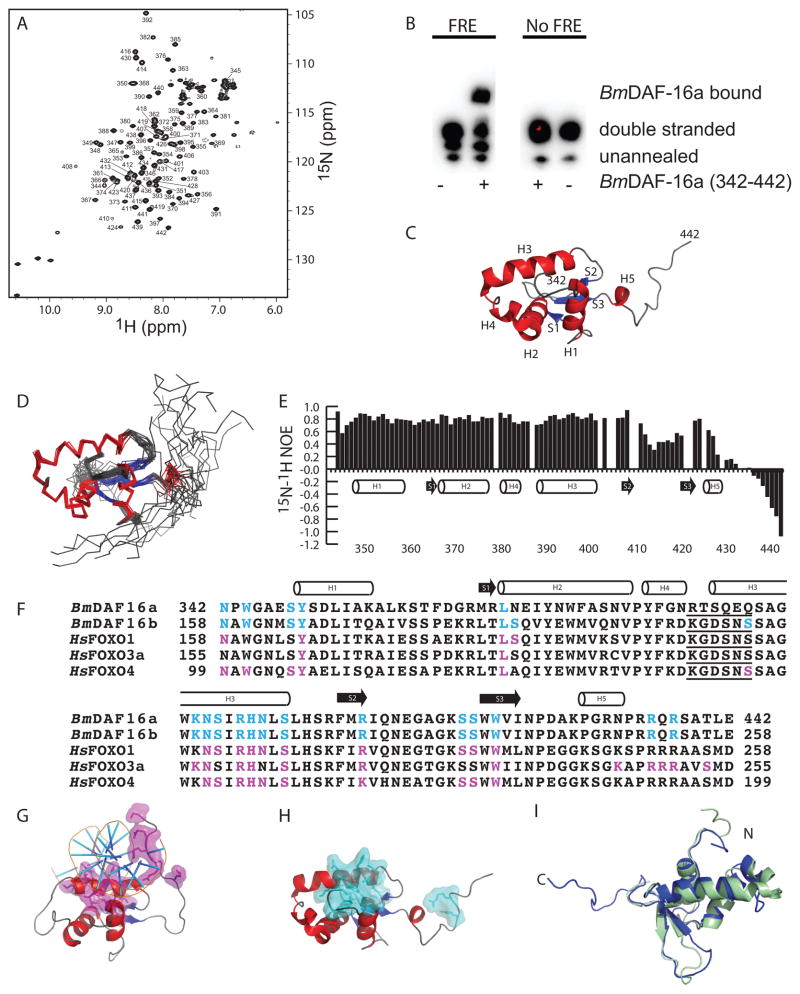

BmDAF-16a (342-442) expressed as an insoluble His6-SMT3 fusion protein and was purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography under denaturing conditions. Subsequent refolding through dialysis, incubation with His6-Ulp1, and immobilized metal affinity chromatography to remove His6-SMT3 and His6-Ulp1 isolated BmDAF-16a (342-442) (Fig. S1). After concentration and buffer exchange, a two dimensional 15N-1H HSQC spectrum of BmDAF-16a (342-442) showed a homogenous spectrum with distinct peaks throughout indicating the protein was folded (Fig. 1A). FREs in B. malayi are unknown, but BmDAF-16a (342-442) induced a mobility shift for a canonical FRE from C. elegans14, confirming folding (Fig. 1B). The solution structure of Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) has the characteristic fold of a forkhead box or winged helix domain containing three alpha helices (H1, H2 and H3), a short fourth alpha helix (H4) found between H2 and H3, a small three stranded antiparallel beta sheet and a C-terminal alpha helix (H5) (Fig. 1C)12. The ensemble of 20 lowest energy Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) structures shows good agreement (Fig. 1D and Fig. S2) except for the C-terminus, which heteronuclear NOE values indicate is unstructured (Fig. 1E). BmDAF-16a (342-442) (11.7 Daltons) and the monomeric SMT3 (11.5 kDa) had nearly identical retention times in gel filtration suggesting that BmDAF-16a (342-442) is a monomer.

Figure 1. Residues in BmDAF-16a (342-442) are identical to FRE interacting residues in human FOXO proteins.

A) 15N-1H HSQC spectra of 500 μM [U-15N/13C] BmDAF-16a (342-442) with backbone amide assignments. B) Mobility shift assay showing Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) binds to DNA containing a canonical FRE sequence from C. elegans and does not bind DNA lacking an FRE sequence. C) The lowest energy structure of BmDAF-16a (342-442). D) Ensemble of 20 BmDAF-16a (342-442) structures. E) 15N-1H heteronuclear NOE values plotted versus BmDAF-16a (342-442) residue. F) Sequence alignment of BmDAF-16a and BmDAF-16b with the DNA binding domains of human FOXO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4. FRE interacting residues in human FOXO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4 are highlighted magenta12. Residues in BmDAF-16a and BmDAF-16b that are identical to DNA interacting residues of the human FOXO proteins are highlighted in cyan. The five amino acid insert consistent with FOXO domains, but not other FOX family members, is underlined12. G) Human FOXO3a bound to an FRE (PDB ID 2UZK)21. DNA interacting residues of FOXO3a are shown in magenta. H) Solution structure of BmDAF-16a (342-442) with residues identical to DNA interacting residues from human FOXO proteins shown in cyan. I) Superimposition of the Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) (blue) and FOXO4 (green, PDB ID 1E17).

At the time of submission to the PDB, Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) was the only forkhead box or winged helix protein from an invertebrate that we could identify in the data bank. Among forkhead box structures in the PDB, Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) showed the highest sequence identity to human FOXO3a, followed closely by FOXO1 and FOXO4. Obsil and Obsilova have reviewed interactions of FOXO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4 with human FRE DNA sequences12. Figure 1F shows sequence alignment of Bm-DAF-16a and Bm-DAF-16b with the human FOXO domains of FOXO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4. Residues in FOXO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4 that bind DNA are highlighted magenta, while identical residues in Bm-DAF-16a/b are highlighted in cyan (Fig. 1F). Helix 3, which plays a large role in FRE interaction, has the characteristic N-X-X-R-H-X-X-S sequence (where X is any amino acid) of all forkhead box transcription factors12. Many of the other amino acids in FOXO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4 that interact with DNA are identical to residues in Bm-DAF-16a/b. Figure 1G shows the structure of human FOXO3a bound to an FRE21. Figure 1H highlights the similarities to Bm-DAF-16a, whose residues that are identical to DNA interacting residues of FOXO1, FOXO3a, or FOXO4 are shown in cyan. Structures of FOXO3a (PDB ID 2K86)22 and FOXO4 (PDB ID 1E17)23 in the absence of DNA were compared to Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) using FATCAT24 and were found to be substantially similar. This can be seen in the superimposition of the apo-FOXO4 structure with Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) (Fig. 1I) (Cα RMSD of 2.61 Å) along with the superimposition of FOXO3a with Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) (Fig. S3) (Cα RMSD of 3.23 Å). Most small differences between each of the structures are located in the termini or loops.

Forkhead box or FOX domains belong to different families12. Members of the FOXO family contain a KGDSNS insertion between H2 and H3 that is not found in other FOX families12. Interestingly Bm-DAF-16a contains a RTSQEQ insertion while the Bm-DAF-16b isoform contains the standard KGDSNS sequence (underlined in Fig. 1E). In the structures of human FOXO1 and FOXO3a bound to an FRE sequence, this KGDSNS insert did not bind DNA12. However, in the structure of human FOXO4 bound to DNA, this KGDSNS insert did interact with DNA12. If these insertions were to interact with DNA, similar to FOXO4, the differences in sequence may suggest a possible mechanism whereby Bm-DAF-16a and Bm-DAF-16b could distinguish between different FREs.

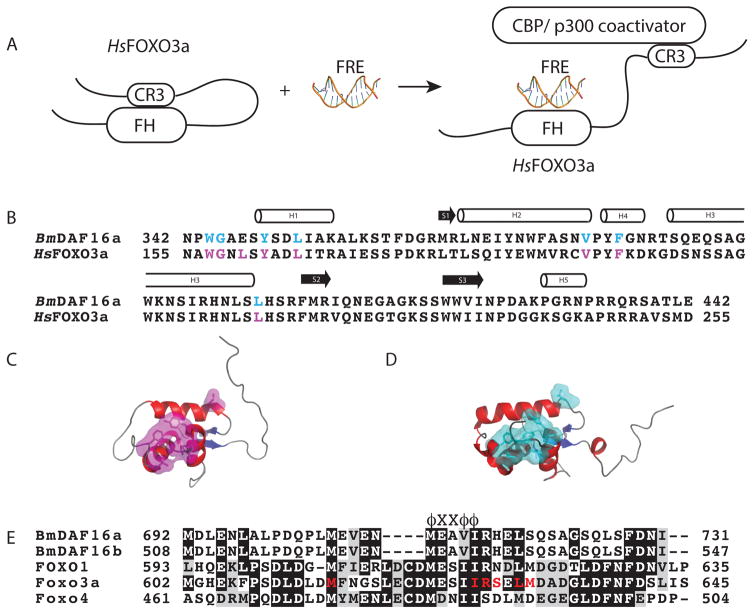

When the forkhead box-O domain of human FOXO3a is not bound to an FRE, it is reported to form an intramolecular interaction with conserved region three (CR3) of FOXO3a, which Wang et al. refers to as the closed state (Fig. 2A)25. Upon binding of the FOXO domain of human FOXO3a to an FRE, the displaced CR3 recognizes and binds to the KIX domain of the CREB binding protein(CBP)/p300 coactivator (Fig 2A)25. Figure 2A shows the model Wang et al. proposed for FOXO3a coativator recruitment25. With the exception of one residue, all CR3 interacting residues of the FOXO domain of human FOXO3a (magenta) are identical in Bm-DAF-16a (cyan) (Fig. 2B). Figure 2C shows the structure of human FOXO3a and Figure 2D shows the structure of Bm-DAF-16a (342-442). The CR3 interacting residues of FOXO3a are shown in magenta, while the identical residues in Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) are highlighted in cyan. The sequence alignment of Bm-DAF-16a/b and human FOXO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4 identified similarities in the CR3 region of these proteins (Fig. 2E). All proteins contain the conserved ϕXXϕϕ CBP/p300 coactivator binding sequence of FOXO3a and other proteins25,26, where ϕ represents any hydrophobic residue and X represents any residue. Additionally, many of the residues of the CR3 region of FOXO3a that interact with the FOXO domain of FOXO3a are identical in Bm-DAF-16a (Fig. 2E)22,25.

Figure 2. Similarities between the structures and identities in the sequences of BmDAF-16a (342-442) and human FOXO3a suggest a potential similarity in coactivator recruitment.

A) Mechanism of human FOXO3a recruitment of coactivator proteins proposed by Wang et al.25. In the absence of an FRE, human FOXO3a adopts a closed state where the DNA binding domain forms an intramolecular interaction with conserved region three (CR3)25. Binding to an FRE displaces CR3 and allows for recruitment of CREB binding protein (CBP) or p300 coactivator through the interaction with CR325. B) Sequence alignment of BmDAF-16a (342-442) with human FOXO3a. CR3 binding residues in human FOXO3a are shown in magenta while identical residues in BmDAF-16a (342-442) are shown in cyan. C) Crystal structure of human FOXO3a (PDB ID 2UZK) with CR3 binding residues highlighted in magenta. D) Solution structure of BmDAF-16a (342-442) with residues identical to CR3 interacting residues from human FOXO3a. E) Sequence alignment of the CR3 region of Bm-DAF16a/b and human FOXO1, FOXO3a and FOXO4. FOXO3a CR3 residues that are reported to interact with the forkhead DNA binding domain are colored red22. The ϕXXϕϕ label, where ϕ represents any hydrophobic residue and X represents any residue, identifies the conserved CBP/p300 coactivator binding sequence of FOXO3a25.

Based on the structural similarities and sequence identities found between Bm-DAF-16a and human FOXO3a, we hypothesize Bm-DAF-16a functions as a transcription factor and recruits coactivator proteins in a fashion that is structurally similar to the model proposed by Wang et al. for human FOXO3a (Fig. 2A)25. Our method for producing Bm-DAF-16a, the chemical shift assignments, and the structure of Bm-DAF-16a (342-442) uniquely position us to experimentally test this hypothesis in future work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

CTV is partially supported by NIH grant 1-R15CA159202-01. University of Wisconsin-Whitewater Undergraduate Research Fellowships supported TJM, AJP, PCS and DMZ. Additional support was provided from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater College of Letters and Sciences. The Medical College of Wisconsin provided NMR time.

References

- 1.Parasites - Lymphatic Filariasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [accessed on 15 July 2013]. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfarr KM, Debrah AY, Specht S, Hoerauf A. Filariasis and lymphoedema. Parasite immunology. 2009;31(11):664–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ottesen EA, Hooper PJ, Bradley M, Biswas G. The global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: health impact after 8 years. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2008;2(10):e317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCarthy J. Is anthelmintic resistance a threat to the program to eliminate lymphatic filariasis? The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2005;73(2):232–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burglin TR, Lobos E, Blaxter ML. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for parasitic nematodes. International journal for parasitology. 1998;28(3):395–411. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riddle DL, Albert PS. Genetic and Environmental Regulation of Dauer Larva Development. In: Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editors. C elegans II. 2. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukhopadhyay A, Oh SW, Tissenbaum HA. Worming pathways to and from DAF-16/FOXO. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41(10):928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massey HC, Jr, Bhopale MK, Li X, Castelletto M, Lok JB. The fork head transcription factor FKTF-1b from Strongyloides stercoralis restores DAF-16 developmental function to mutant Caenorhabditis elegans. International journal for parasitology. 2006;36(3):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelmedin V, Brodigan T, Gao X, Krause M, Wang Z, Hawdon JM. Transgenic C. elegans dauer larvae expressing hookworm phospho null DAF-16/FoxO exit dauer. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castelletto ML, Massey HC, Jr, Lok JB. Morphogenesis of Strongyloides stercoralis infective larvae requires the DAF-16 ortholog FKTF-1. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(4):e1000370. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi YJ, Ghedin E, Berriman M, McQuillan J, Holroyd N, Mayhew GF, Christensen BM, Michalski ML. A deep sequencing approach to comparatively analyze the transcriptome of lifecycle stages of the filarial worm, Brugia malayi. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2011;5(12):e1409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obsil T, Obsilova V. Structural basis for DNA recognition by FOXO proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(11):1946–1953. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC. OutFOXOing disease and disability: the therapeutic potential of targeting FoxO proteins. Trends in molecular medicine. 2008;14(5):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuyama T, Nakazawa T, Nakano I, Mori N. Identification of the differential distribution patterns of mRNAs and consensus binding sequences for mouse DAF-16 homologues. Biochem J. 2000;349(Pt 2):629–634. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6(3):277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markley JL, Ulrich EL, Westler WM, Volkman BF. Macromolecular structure determination by NMR spectroscopy. Methods Biochem Anal. 2003;44:89–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2009;44(4):213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrmann T, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J Mol Biol. 2002;319(1):209–227. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linge JP, Williams MA, Spronk CA, Bonvin AM, Nilges M. Refinement of protein structures in explicit solvent. Proteins. 2003;50(3):496–506. doi: 10.1002/prot.10299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhattacharya A, Tejero R, Montelione GT. Evaluating protein structures determined by structural genomics consortia. Proteins. 2007;66(4):778–795. doi: 10.1002/prot.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai KL, Sun YJ, Huang CY, Yang JY, Hung MC, Hsiao CD. Crystal structure of the human FOXO3a-DBD/DNA complex suggests the effects of post-translational modification. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35(20):6984–6994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang F, Marshall CB, Yamamoto K, Li GY, Plevin MJ, You H, Mak TW, Ikura M. Biochemical and structural characterization of an intramolecular interaction in FOXO3a and its binding with p53. J Mol Biol. 2008;384(3):590–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weigelt J, Climent I, Dahlman-Wright K, Wikstrom M. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of the human forkhead transcription factor AFX (FOXO4) Biochemistry. 2001;40(20):5861–5869. doi: 10.1021/bi001663w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye Y, Godzik A. Flexible structure alignment by chaining aligned fragment pairs allowing twists. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(suppl 2):ii246–ii255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang F, Marshall CB, Li GY, Yamamoto K, Mak TW, Ikura M. Synergistic interplay between promoter recognition and CBP/p300 coactivator recruitment by FOXO3a. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4(12):1017–1027. doi: 10.1021/cb900190u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang F, Marshall CB, Yamamoto K, Li GY, Gasmi-Seabrook GM, Okada H, Mak TW, Ikura M. Structures of KIX domain of CBP in complex with two FOXO3a transactivation domains reveal promiscuity and plasticity in coactivator recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(16):6078–6083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119073109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunger AT. A system for X-ray crystallography and NMR. New Haven: CT Yale University Press; 1992. X-PLOR, version 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engh RA, Huber R. Accurate bond and angle parameters for X-ray protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1991;47(4):392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Marius Clore G. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J Magn Reson. 2003;160(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8(4):477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.