Abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is generally progressive and associated with reduced physical activity. Both pharmacological therapy and exercise training can improve exercise capacity; however, these are often not sufficient to change the amount of daily physical activity a patient undertakes. Behaviour-change self-management programmes are designed to address this, including setting motivational goals and providing social support. We present and discuss the necessary methodological considerations when integrating behaviour-change interventions into a multicentre study.

Methods and analysis

PHYSACTO is a 12-week phase IIIb study assessing the effects on exercise capacity and physical activity of once-daily tiotropium+olodaterol 5/5 µg with exercise training, tiotropium+olodaterol 5/5 µg without exercise training, tiotropium 5 µg or placebo, with all pharmacological interventions administered via the Respimat inhaler. Patients in all intervention arms receive a behaviour-change self-management programme to provide an optimal environment for translating improvements in exercise capacity into increases in daily physical activity. To maximise the likelihood of success, special attention is given in the programme to: (1) the Site Case Manager, with careful monitoring of programme delivery; (2) the patient, incorporating patient-evaluation/programme-evaluation measures to guide the Site Case Manager in the self-management intervention; and (3) quality assurance, to help identify and correct any problems or shortcomings in programme delivery and ensure the effectiveness of any corrective steps. This paper documents the comprehensive methods used to optimise and standardise the behaviour-change self-management programme used in the study to facilitate dialogue on the inclusion of this type of programme in multicentre studies.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards, Independent Ethics Committee and Competent Authority according to national and international regulations. The results of this study will be disseminated through relevant, peer-reviewed journals and international conference presentations.

Trial registration number

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Behaviour-modification interventions performed by Site Case Managers who have recognised expertise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Site Case Managers received formal training prior to study initiation and are supported throughout the study with educational opportunities and performance feedback.

Behavioural intervention is well defined including new methods for quality assurance.

The main limitation is the design of the trial, since there is no group that does not receive the behaviour-change intervention. Inclusion of this group would allow the impact of the behaviour-change intervention to be evaluated.

Another limitation is that due to budget constraints, there is no long-term follow-up to assess whether changes in patient behaviour are sustained.

Introduction

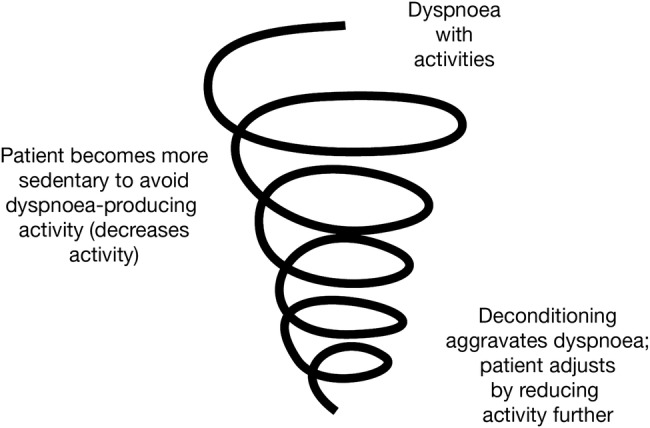

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a common and treatable disease,1 have reduced walking time, standing time and movement intensity in daily life.2 3 Reduced physical activity has been suggested to lead to a downward spiral of symptom-induced inactivity (figure 1),4 which could directly impact on hospital readmission as well as patient outcomes, quality of life and mortality.5–7 Recently, the European Respiratory Society reviewed the evidence for increasing physical activity as part of an integrated programme of COPD management, finding a relationship between low levels of physical activity and magnitude of decline in lung function.8

Figure 1.

Decline in lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with inactivity and avoiding exercise, leading to a spiral of declining patient condition. Reprinted from The American Journal of Medicine, Vol 119 (10A), Reardon et al.4 Functional status and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, S32–37, Copyright 2006, with permission from Elsevier.

While both pharmacological therapy and exercise training can improve exercise capacity,9–12 evidence suggests that supervised exercise training (ie, pulmonary rehabilitation) without modification of patient behaviour is unlikely to be sufficient to change the actual amount of daily physical activity that a patient engages in, regardless of improvements in exercise capacity.13 Behaviour-change interventions, such as evidence-based self-management training and support, including setting patient goals, are designed with this in mind14 and may be more effective when delivered in a structured manner, specific to the health problem of interest.15 16

Several studies have included behaviour-targeted programmes with the aim of increasing physical activity in adults with chronic diseases, including COPD, diabetes, heart failure and obesity.17 Across these studies, programmes were performed in conjunction with exercise training and included education, training, counselling, behaviour-change support and/or follow-up sessions.17 In studies of coronary heart disease, psychosocial interventions including cognitive behavioural therapy, stress management and antidepressant treatment have been shown to reduce cardiac events, while cardiac rehabilitation, including exercise training, reduced mortality.18

There are many design issues to take into consideration when implementing behavioural interventions in a study.19 These interventions are complex, involving multiple inter-related components, and must be standardised but personalised and administered consistently to all patients to show a treatment effect. Programme variations, together with the level of care providers' expertise (eg, the case manager), can have a profound impact on treatment outcomes. Published studies provide little guidance, lacking the necessary details (eg, type, quantity, timing and method of delivery; tools used; quality-assurance methods) to replicate or inform adaptations of the intervention.

This paper presents and discusses new approaches for the implementation of a behaviour-change self-management programme into a multicentre study in COPD, with special attention paid to methodological issues (intervention design, delivery and surveillance/quality control). This is illustrated with the PHYSACTO study, a phase IIIb study designed to assess the effect of a new COPD maintenance bronchodilator therapy and supervised exercise training on exercise capacity (primary outcome as measured by the endurance shuttle walk test) and physical activity (secondary outcomes including the amount of physical activity (measured using the PROactive tool) and perceived difficulties). The inclusion of the behaviour-change self-management programme in all intervention arms (including placebo) provides an optimal environment for translation of improvements in exercise tolerance into increases in physical activity. The objectives with respect to the behaviour-modification programme are to explore the extent to which potential moderating variables (eg, motivation, self-efficacy, cognitive function, anxiety and depression, and external and internal barriers) could influence the increase in physical activity during everyday tasks. A self-management programme such as this, based on complex interactions, is associated with several specific challenges, which we will describe, including how to ensure the intervention is delivered consistently ‘per protocol’ by intervention providers across this multicentre study.

Methods

Study design

PHYSACTO is a 12-week, randomised, partially double-blind, placebo-controlled, multisite, international, four-parallel group study (NCT02085161) in patients with a diagnosis of COPD. The purpose of the study is to evaluate the effects on exercise capacity and physical activity of administration of COPD maintenance pharmacotherapy alone or in combination with supervised exercise training. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed elsewhere20 and will not be discussed here. The study is being conducted in 11 countries at 34 study sites, each contributing and managing an average of eight patients. Overall, the PHYSACTO study plans to continue until 300 patients have been randomised.

Interventions and incorporation of a behaviour-change programme into the study

Following a 4-week washout period, patients are randomised to once-daily tiotropium+olodaterol 5/5 μg combined maintenance treatment with exercise training, tiotropium+olodaterol 5/5 µg combined maintenance treatment without exercise training, tiotropium 5 µg or placebo, with all pharmaceutical treatments administered via the Respimat inhaler (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) and a behaviour-change programme included in all intervention groups.

Study outcomes

The primary aim is to assess the effects on exercise capacity of tiotropium+olodaterol or tiotropium alone or in conjunction with supervised exercise training. The secondary aim is to assess the extent to which pharmacotherapy and exercise training can enhance the effects of the behaviour-change programme on the amount and perceived difficulty of physical activity.

Study outcome measures are described in the companion paper.20 Briefly, the primary outcome of the study is endurance time during an endurance shuttle walk test to symptom limitation after 8 weeks of therapy. Secondary outcomes include assessments of patients' levels of physical activity using an activity monitor,8 patients' reports of the ease or difficulty with which they perform daily activities quantified by the Functional Performance Inventory—Short Form,21 22 a daily activity diary completed on the days patients wear the activity monitor, and lung function.

Exploratory end points are included to examine the extent to which certain patient variables moderate the relationship between exercise capacity and physical activity. These patient-reported measures and questionnaires include cognitive function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment),23 anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale)24 and the presence of major depressive disorder (Brief Patient Health Questionnaire-mood).25 26

The behaviour-change self-management programme

A 12-week behaviour-change programme is included in all arms of the PHYSACTO study to provide an optimal environment for translation of improvements in exercise capacity into long-term increases in daily physical activity. Most exercise-intervention studies in chronic diseases published to date have focused on targeting the patient via educational programmes, counselling or exercise programmes, in order to achieve changes in daily physical activity.17 Our approach is designed to effect changes in patient behaviour by: building on the experience, training and effectiveness of case managers; standardising the content of the programme across sites; helping case managers adjust the programme based on patient responses using a standardised feedback process; and including quality-assurance steps throughout the programme. Because PHYSACTO is a multicentre study, we have to ensure that delivery of the behaviour-change self-management programme can be standardised across different locations, while also ensuring that individual patient needs, preferences and personal goals inform the intervention.

The Site Case Manager: selection and training

The Site Case Manager (SCM) is required to have a minimum of 2 years' experience working with patients with COPD and recognised expertise in the area. To optimise the quality and impact of the behaviour-change intervention, we provide 3 days of standardised training to the SCMs in evidence-based behaviour-change techniques (eg, motivational communication, goal setting, reinforcement and problem solving) that is supplemented by online tutorials (training reviews, case studies) and systematic feedback from the behaviour-modification team if performance is judged to be unsatisfactory. This training is based on the self-management educational programme ‘Living Well with COPD’,27 which is designed to help patients with COPD and their families cope with their disease on a daily basis, while a reference guide can assist the healthcare professionals in engaging with their patients and facilitating improved disease self-management.

The programme has been adapted for the current study by focusing on improving patient engagement in, and maintenance of, exercise and physical activity. An important element of the educational programme is training in the principles of behaviour change and methods to engage, motivate and build patient confidence. Basic training in motivational communication skills includes using open questions and building motivation to engage patients in more physical activity, using reflective listening to manage and overcome resistance, and providing information by offering, sharing and asking patients for feedback.28

The educational programme

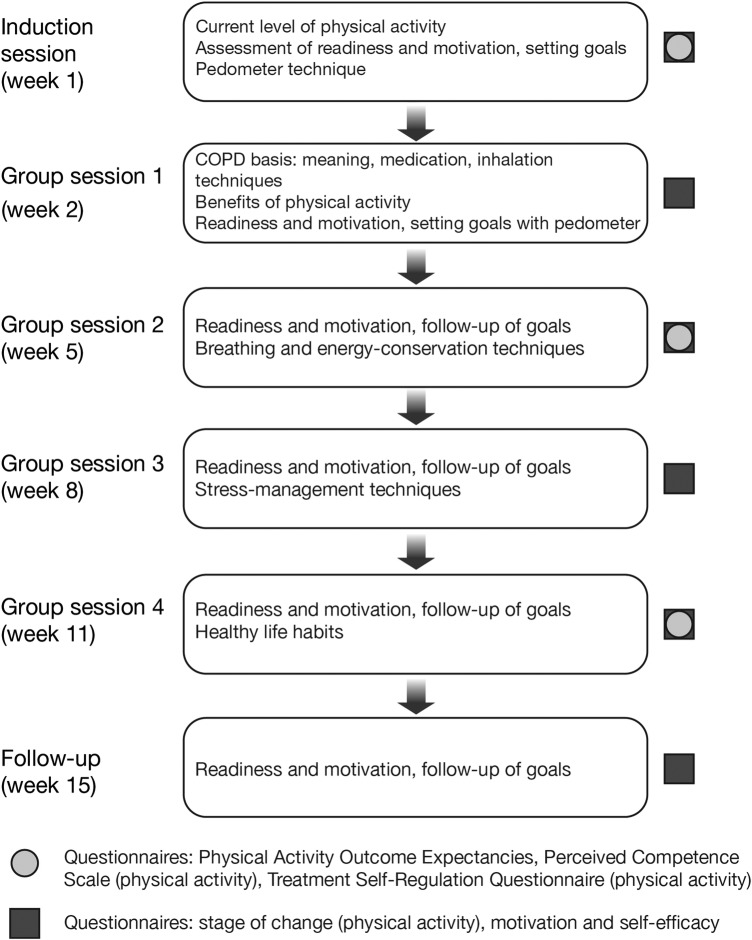

The educational programme schedule for patients starts with an individual induction session at the beginning of the intervention period, followed by group sessions at weeks 2, 5, 8 and 11, with another individual session at follow-up (figure 2). The sessions are led by the SCM, who guides the patient in self-management behaviours that aid in achieving physical activity goals, while improving daily COPD management.

Figure 2.

Overview of the behaviour-change programme. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Individual induction session: During the individual induction session, the SCM performs an assessment to determine the patient's current level of physical activity, functional limitations and any clinical barriers to physical activity (including motivation). The patient is also given a printed booklet from the ‘Living Well with COPD’ programme, described further below. The patient's ultimate goal is defined at this stage as their desired achievements in work, home and leisure by the end of the programme. The SCM coaches the patient to define and reach their ultimate physical-activity goal (eg, what they will be able to do at the end of the programme, such as being able to play in the park with their grandchildren). This ensures that the patient remains engaged and motivated in the pursuit of their physical activity goals. This is followed by instructions on the use of the pedometer (including a demonstration by the patient to test competency), which is subsequently used during the study for setting intermediate goals (eg, number of daily steps before the next session). The educational materials provided to the patient specify an example of an objective for patients. These materials state: “Your first objective will be to add 1000 steps to your daily average. Maintain this level over a 1-month period. If you reach your goal, add another 1000 steps and maintain this for 1 month. Keep increasing your objective in this way until you have reached 5000 to 6000 steps per day. If your condition allows it, you can keep increasing up to 10,000 steps per day.” The SCM records the patient's progress throughout the study using a patient worksheet (see online supplementary appendix 1). For each session, there is also an itemised session evaluation that is completed by the SCM (see online supplementary appendix 2). Patient worksheets, session-evaluation forms and patient-evaluation/programme-evaluation questionnaires remain with the SCM throughout the study in order to track patient progress.

bmjopen-2015-010109supp_appendix1.pdf (102.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010109supp_appendix2.pdf (131.6KB, pdf)

Group sessions: At the 90–120 min group sessions (figure 2), the SCM explains the benefits of physical activity and setting physical-activity goals. Patients select and review their own personal goals and sign a ‘learning contract’ as a symbolic gesture to formalise these goals (group session 2, week 5). Patients also receive education on their disease, healthy life habits, stress management, breathing techniques, exercise planning and how to distinguish normal from abnormal physical symptoms. In order to respond to the changing needs of individual patients, the educational programme is designed to allow for adjustment of the programme components, as required.

Group sessions are also used to identify any barriers that may have prevented patients from reaching their physical-activity goals, with patients regularly reflecting on their progress and reviewing their goals on paper. These sessions are supplemented with the ‘Living Well with COPD’ programme booklet, which contains topics on promotion of physical activity, COPD and medication, breathing and energy-conservation techniques, stress and anxiety management, and improving health behaviours. Patients are assigned sections to read after each session, and each topic concludes with a series of questions to test understanding.

Patients' comprehension, attitudes and skills are assessed throughout the intervention to determine if they have met pre-established goals and objectives. Several methods are used to supplement information and correct misunderstandings in a constructive way, as well as reinforce newly acquired skills and behaviours. These methods include direct open questioning, problem-solving exercises, simulations (patients demonstrate a proposed technique, such as using an inhaler) and direct observation. Throughout the intervention, patients are asked to repeat key instructions and summarise in their own words what they have learned and understood. When patients do not achieve their goals and objectives, the educational plan is revised and other methods are used for education and building skills.

Follow-up session: The inclusion of a follow-up session as part of the behaviour-change programme allows the SCM to review with the participants their motivation to continue to pursue their physical-activity goals. Barriers and facilitators to continuing physical activity and possible solutions are discussed. Finally, patients are thanked for their participation and encouraged to continue to apply the skills learned throughout the programme.

Individualised interventions: In order to respond to the changing needs of individual patients with COPD as they progress through the study, the behaviour-change programme is designed to allow for adjustments. These adjustments are based on feedback from the participants to the SCM during the group sessions and analysis of the results of the change-programme process-evaluation tools completed by study participants at each intervention visit. These measures are described below.

Behaviour-change process measures

An important note in terms of patient evaluation is the difference between outcome measures and process measures (table 1).29–34 In clinical studies, outcome measures are used to test the effects of the intervention on the patient; in this case, exercise capacity, the difficulty and amount of daily activity, and other study end points described above. The SCMs are blinded to the outcome measures during the study. For behavioural interventions, process measures are an important part of the delivery of the intervention, permitting the therapist to evaluate each participant's progress and make adjustments to the programme where needed. These measures may also be useful during the interpretation of study results (outcomes).

Table 1.

Study outcome measures and process measures*

| Measure | Aspect being measured/assessed |

|---|---|

| Study outcome measures | |

| Endurance shuttle walk test | Exercise capacity |

| 6 min walk test29 | Exercise capacity |

| Activity monitoring | Physical activity |

| Functional Performance Inventory—Short Form | Perceived ease or difficulty with daily activities |

| PROactive | Amount and difficulty of daily activity |

| Spirometry | Lung function |

| Modified Borg Scale | Intensity of breathing discomfort |

| St George's Respiratory Questionnaire32 | Health status |

| Heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, adverse events | Safety assessments |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment23 | Cognitive function |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale24 | Anxiety and depression |

| Brief Patient Health Questionnaire-mood25 26 | Major depressive disorder |

| Behaviour-change self-management programme process measures | |

| Physical Activity Outcome Expectancies questionnaire30 | Patient expectancies of physical activity |

| Perceived Competence Scale34 | Feelings of competence about engaging in healthier behaviour |

| Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire33 | Degree to which a patient's motivation for a specific behaviour is self-determined |

| Stage of change31 | Readiness for change |

| Self-efficacy and motivation questions related to specific programme contents | Levels of motivation for change and confidence to change |

*Outcome measures provide data on the effects of the self-management intervention. Process measures inform the Site Case Manager to help direct the self-management intervention.

This behaviour-intervention programme includes a series of questionnaires completed by patients during the course of the intervention to assess the process of change and permit the SCM to evaluate individual patient needs and progress, and make adaptations to the programme as needed over time. Questionnaires that have been adapted for this study are completed during the individual induction session with the SCM, and again at weeks 5 and 11, and include the Physical Activity Outcome Expectancies questionnaire, which assesses patients' expectations regarding outcomes of the study,30 the Perceived Competence Scale (for physical activity), which assesses patients' confidence in their ability to engage in physical activity,34 and the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (for physical activity), which assesses different motivators or reasons for engaging in physical activity.33 Three additional questionnaires are administered by the SCM at all sessions (figure 2). They include the stage of change (for physical activity) visual analogue scale, which assesses readiness to engage in physical activity,31 and two, 0–10 Likert-type scales assessing motivation (on a scale of ‘not at all important’ to ‘very important’) and self-efficacy or confidence (on a scale of ‘not at all confident’ to ‘very confident’) to engage in physical activity. To assess motivation, we asked ‘How important do you think it is to maintain regular physical activity, at least 30 min per day or x number of steps?’. To assess confidence, we asked ‘How confident are you in your ability to (1) use your pedometer to track your progress, (2) maintain regular physical activity, at least 30 min per day or x number of steps?’. These three additional questionnaires are completed to enable the SCM to monitor patients' motivation, confidence and movement through the stages of change and to intervene onsite if patients are not responding to the intervention in the desired or expected direction.

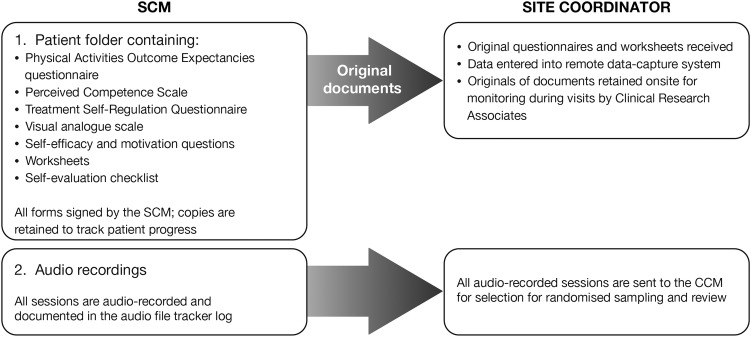

The study coordinator at each study site receives the original questionnaires and worksheets completed by the SCM. These data are then entered into the remote data-capture system; an overview of this process is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Data flow between SCMs and site coordinators. CCM, Country Case Manager; SCM, Site Case Manager.

Quality assurance

To ensure a standardised delivery of the behaviour-change interventions, the programme is overseen by a Global Behavioural Change (GBC) training team, which provides 3 days of face-to-face training to SCMs. SCMs receive a ‘reference guide’ describing the objectives, interventions, suggested questions, expected results and available resources for each intervention. SCMs also review their own performance by completing self-evaluation forms after each session. Additionally, recordings of the sessions are assessed by random sampling to ensure all the educational topics have been covered and that they are delivered by the SCM using the behaviour-change strategies (eg, motivational communication skills) outlined in the protocol. Audio files are sent for review by the SCM to the Country Case Manager (CCM), who also acts as a country-specific cultural and language liaison between the GBC team and SCMs. The CCM completes a data-extraction form (see online supplementary appendix 3), verifies that all educational topics are covered and provides counts of the number of times each motivational communication skill has been used to deliver each topic. The CCM then provides constructive, corrective feedback to the SCM when necessary, including positive feedback on good performance.

bmjopen-2015-010109supp_appendix3.pdf (136.4KB, pdf)

The GBC team reviews all the data-extraction forms for quality assurance and provides feedback to the CCM. This team will also lead eight additional web conferences with CCMs to provide training support and performance feedback for each site during the conduct of the study. Feedback is provided to the SCM via the CCM as required. Additional sessions may be sampled to ensure quality is maintained. Reports are produced by Local Clinical Monitors/Clinical Research Associates or Clinical Quality Assurance Auditors and are submitted to the global managers, who also provide feedback to the SCM indirectly via the CCM. Finalised reports are ultimately filed with the sponsor's Study Master File. Table 2 presents an overview of the study design elements and quality-control process of the behaviour intervention.

Table 2.

Study design elements from PHYSACTO for the standardisation and sustainability of the behaviour-change intervention

| Level | Action |

|---|---|

| SCM and patient | Audio-record sessions Clearly label tapes and provide to the site coordinator |

| Site coordinator | Review identification and control log Carry out session sampling (two random induction sessions per cohort, two random group sessions and two random follow-up sessions) Send to the CCM Destroy records |

| CCM | Assess tapes Complete data-extraction forms and send to the GBC team Provide immediate feedback to the SCM as needed |

| GBC team | Review data extractions Provide feedback to the CCM |

CCM, Country Case Manager; GBC, Global Behaviour Change; SCM, Site Case Manager.

Further details relating to the design of the PHYSACTO study are reported in our companion paper20 according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines35 and a completed SPIRIT checklist is available online.

Ethics and data dissemination

The studies are to be carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and written informed consent will be obtained from each patient.

Discussion

This is the first multicentre study of maintenance therapy in COPD in which all intervention arms included a behaviour-change self-management programme to facilitate increased physical activity during daily life, with special attention to methodological issues such as quality control. Particular focus is directed towards the SCM, the patient (including patient evaluation), and defining and implementing quality-assurance activities. The incorporation of a behaviour-change self-management programme in this clinical trial aims to demonstrate that, with the use of long-acting bronchodilators and behavioural self-motivation interventions, there is potential to not only influence exercise capacity but also improve the amount and effort of physical-activity performance in patients with COPD. Self-management programmes have been proposed as the best way to assist patients in acquiring and practising the necessary skills to control their disease symptoms on a daily basis and to implement healthy behaviours.36 37 The premise is that if patients receive effective self-management support, they can be empowered to adopt the behaviours needed to cope optimally with their disease, so that many of the poor outcomes related to chronic disease can be averted. However, studies have not been consistent in demonstrating benefits. From a recent literature review,17 significant improvements in physical activity in patients with COPD were shown in five out of eight evaluable studies. The five successful studies were based on theoretical models of behaviour change and included exercise interventions of approximately 30 min, 3–5 times a week. Behavioural interventions ranged from counselling and personal contact to educational pamphlets.17 This study builds on this insight by including and documenting a comprehensive, well-defined behavioural self-management intervention programme designed specifically to effect change in patients' physical activity.

The effectiveness of any complex intervention, such as self-management in patients with COPD, crucially depends on the healthcare professionals and the delivery of the intervention to the patient. Most studies published to date give little attention to personnel and processes. In our study, SCMs are required to have recognised expertise in COPD and at least 2 years' experience in order to participate. In addition, SCMs are provided with 3 days' training based on the self-management educational programme ‘Living Well with COPD’. SCMs are also supported through educational opportunities and feedback during the study by the CCMs and the GBC team.

There is still no accepted best practice for the level of qualification and training required for the SCM, and no evidence that training is effective. However, it is generally accepted that training in behaviour-change and self-management skills is needed. SCMs are likely to benefit from having at least basic training in the principles of behaviour change, as well as basic training in motivational communication skills, including methods to engage, motivate and build confidence in patients. However, one of the most important challenges to overcome is the gap between how the intervention is designed to be delivered and how the SCM actually delivers it. This gap is clearly underestimated or underevaluated in most behavioural studies, as well as in practice. Furthermore, being able to assess and provide feedback to the SCM is necessary to ensure best practice.

In our study, we planned and implemented several quality-assurance assessments to reduce the potential of failing to deliver the intervention in the way it was intended. All sessions between patients and SCMs are audio-recorded and randomly assessed for quality assessment and feedback, the programme delivery is assessed in a standardised way (including careful monitoring and recording of the use of motivational communication skills with patients) and feedback on SCM performance is provided and followed up to assess the effectiveness of any corrective steps. Evaluating whether the SCM intervention is delivered as intended is the most important part of quality assurance, and a crucial and novel methodological consideration in this study.38

The international, multisite design of this study is a significant challenge. Audio files of SCMs' performances have to be reviewed using a standardised data-extraction sheet by a CCM who acts as a country-specific cultural and language liaison. Finally, we have in place a GBC team that reviews all the data-extraction forms and provides systematic and timely feedback to the CCM.

Another very important methodological aspect of this study is the attention we give to relevant ‘enablers’ for behaviour modification in attempting to effect change in patients' levels of physical activity, while acknowledging that physical activity is itself a behaviour. It is well recognised that it is important to equip patients with the proper techniques and skills (eg, knowledge and confidence) required to effectively self-manage their condition. Furthermore, enhancing patients' motivation to change and overcome ambivalence is crucial. This is best achieved using patient-centred, motivational communication techniques that encourage participants to express their intrinsic motivations to adopt certain health behaviours (eg, consistent with their values or life goals). Questionnaires to assess the process of change have been adapted for this study and are completed by the patient (with the SCM) at multiple time points to evaluate progress. These questionnaires assess motivation, perceived competency (confidence), readiness to change and expectancies of physical activity. The main purpose of these process measures is to inform the SCM of a patient's progress and to help direct and individualise the self-management intervention.

The results of these questionnaires inform the personalised delivery of the behavioural intervention to patients based on their readiness to change and progress in the programme. To date, most studies have limited assessments to trial outcome measures. By including process measures, the intent is to not only intervene more effectively during the course of the intervention but also gather information that could facilitate the interpretation of study outcomes.

To date, most published randomised clinical studies with behaviour interventions have not described the specific components of the intervention, nor have they included or described process measures to track changes in patients' behaviour and make individualised adjustments to enhance the effects of this therapy. As such, evidence of established processes and procedures for the implementation and monitoring of behavioural studies is lacking. Being able to better define and implement such a programme, and making it accessible in practice, would be highly valuable. However, this can only be accomplished by raising the standards and quality of evidence-based behaviour interventions and programmes. This multicentre study is a first step towards integrating a more coherent and careful plan at the patient, provider (health professional/case manager) and system or organisational levels.

Conclusions

This is the first study to use a multifactorial intervention to improve exercise capacity and physical activity in patients with COPD, incorporating pharmacotherapy, exercise training and behaviour change. This paper documents the comprehensive methods being used to optimise and standardise the behaviour-change self-management programme used in the study to facilitate dialogue on the inclusion of this type of programme in multicentre studies.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Laura George, PhD, of Complete HealthVizion, which was contracted and compensated by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma Inc.

Footnotes

Contributors: TT and JB are the principal investigators in the PHYSACTO trial. FM and NL are part of the protocol steering committee. KLL, JB and MS provided guidance for the design of the behaviour modification programme. FM and TT provided insight into the exercise training programmes and TT provided guidance on the implementation of the PROactive tool. NL was involved in the protocol design and specifically provided expertise in the patient-reported outcomes and perception scales. DE, DDS and AH were involved in the design of the study and are involved in the implementation of the study. All authors were involved in reviewing and criticising this paper.

Funding: The PROactive project is funded by the IMI-JU grant number #115011. The PHYSACTO trial is an in-kind contribution of the sponsor Boehringer Ingelheim to the PROactive project.

Competing interests: JB has received grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research R&D collaborative programme (AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Nycomed, Novartis), the Canadian Respiratory Research Network, the Respiratory Health Network of the FRQS and the Research Institute of the MUHC. KLL reports personal fees from the study sponsor for personnel training, as well as a grant from AbbVie and personal fees from Bayer, Janssen, Novartis, AbbVie, Mundipharma and Almirall. MS is employed by Respiplus, a non-profit organisation that was contracted by the study sponsor to develop the educational component of the training programme. DDS, DE and AH are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. FM has received grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Nycomed and Pfizer, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, and other financial support from GlaxoSmithKline. TT has received grants from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking and speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline. NL is employed by Evidera, a healthcare research firm that provides consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical and other organisations including the study sponsor. The authors meet the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. They take full responsibility for the scope, direction, content of, and editorial decisions relating to the manuscript, were involved in reviewing and revising the manuscript at all stages of development, and have approved the submitted manuscript.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The protocol was approved on 19/02/2014 by the Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee (11.14HREC/14/SAC/19). All other participating centres subsequently approved the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The findings of the trial will be disseminated through relevant peer-reviewed journals and international conference presentations.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Updated 2015 2015. http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2015_Feb18.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2015).

- 2.Pitta F, Troosters T, Spruit MA et al. Characteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:972–7. 10.1164/rccm.200407-855OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Troosters T, Sciurba F, Battaglia S et al. Physical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-study. Respir Med 2010;104:1005–11. 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reardon JZ, Lareau SC, ZuWallack R. Functional status and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 2006;119:32–7. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS et al. Physical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPD. Chest 2006;129:536–44. 10.1378/chest.129.3.536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Aymerich J, Serra I, Gómez FP et al. Physical activity and clinical and functional status in COPD. Chest 2009;136:62–70. 10.1378/chest.08-2532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaes AW, Garcia-Aymerich J, Marott JL et al. Changes in physical activity and all-cause mortality in COPD. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1199–209. 10.1183/09031936.00023214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL et al. An official European Respiratory Society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1521–37. 10.1183/09031936.00046814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maltais F, Mahler DA, Pepin V et al. Effect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol plus tiotropium versus tiotropium on walking endurance in COPD. Eur Respir J 2013;42:539–41. 10.1183/09031936.00074113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maltais F, Gáldiz Iturri JB, Kirsten A et al. Effects of 12 weeks of once-daily tiotropium and olodaterol fixed-dose combination on exercise endurance in patients with COPD [abstract]. Eur Respir J 2014;44(Suppl 58):abs P283 10.1183/09031936.00024314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maltais F, Singh S, Donald A et al. Effects of a combination of vilanterol and umeclidinium on exercise endurance in subjects with COPD: two randomised clinical trials [abstract]. Eur Respir J 2013;42(Suppl 57):abs P761 10.1183/09031936.00074113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maltais F, Kirsten A-M, Hamilton A et al. Evaluation of the effects of olodaterol on exercise endurance in patients with COPD: results from two 6-week studies [abstract]. Chest 2013;144(No.4 Meeting Abstracts):abs 748A 10.1378/chest.1701949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS et al. Are patients with COPD more active after pulmonary rehabilitation? Chest 2008;134:273–80. 10.1378/chest.07-2655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourbeau J, Nault D, Dang-Tan T. Self-management and behaviour modification in COPD. Patient Educ Couns 2004;52:271–7. 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00102-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health behavior and health education. Theory, research, and practice. 4th edn San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouleau CR, Lavoie KL, Bacon SL et al. Training healthcare providers in motivational communication for promoting physical activity and exercise in cardiometabolic health settings: do we know what we are doing? Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2015;9:29 10.1007/s12170-015-0457-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leidy NK, Kimel M, Ajagbe L et al. Designing trials of behavioral interventions to increase physical activity in patients with COPD: insights from the chronic disease literature. Respir Med 2014;108:472–81. 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutledge T, Redwine LS, Linke SE et al. A meta-analysis of mental health treatments and cardiac rehabilitation for improving clinical outcomes and depression among patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 2013;75:335–49. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318291d798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavoie KL, Campbell TS, Bacon SL. Behavioral medicine trial design: time for a change. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1350–1. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Troosters T, Bourbeau J, Maltais F et al. Enhancing exercise tolerance and physical activity in COPD with combined pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions: PHYSACTO randomised, placebo-controlled study design. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010106 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leidy NK, Knebel A. In search of parsimony: reliability and validity of the Functional Performance Inventory-Short Form. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010;5:415–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leidy NK, Hamilton A, Becker K. Assessing patient report of function: content validity of the Functional Performance Inventory-Short Form (FPI-SF) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2012;7:543–54. 10.2147/COPD.S32032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW et al. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA 1999;282:1737–44. 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K et al. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:759–69. 10.1067/mob.2000.106580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Living Well with COPD™ 2015. http://www.livingwellwithcopd.com/en/home.html (accessed 12 Jan 2015).

- 28.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care. Helping patients change behavior. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Thoracic Society. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–17. 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2000;31:73–86. 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garber CE, Allsworth JE, Marcus BH et al. Correlates of the stages of change for physical activity in a population survey. Am J Public Health 2008;98:897–904. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM et al. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:1321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levesque CS, Williams GC, Elliot D et al. Validating the theoretical structure of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ) across three different health behaviors. Health Educ Res 2007;22:691–702. 10.1093/her/cyl148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care 1998;21:1644–51. 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bourbeau J. Making pulmonary rehabilitation a success in COPD. Swiss Med Wkly 2010;140:w13067 10.4414/smw.2010.13067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bourbeau J. The role of collaborative self-management in pulmonary rehabilitation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2009;30:700–7. 10.1055/s-0029-1242639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacon SL, Lavoie KL, Ninot G et al. An international perspective on improving the quality and potential of behavioral clinical trials. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2015;9:427 10.1007/s12170-014-0427-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010109supp_appendix1.pdf (102.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010109supp_appendix2.pdf (131.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010109supp_appendix3.pdf (136.4KB, pdf)