Abstract

Background

As bacterial cells enter stationary phase, they adjust their growth rate to comply with nutrient restriction and acquire increased resistance to several stresses. These events are regulated by controlling gene expression at this phase, changing the mode of exponential growth into that of growth arrest, and increasing the expression of proteins involved in stress resistance. The two-component system SpdR/SpdS is required for the activation of transcription of the Caulobacter crescentus cspD gene at the onset of stationary phase.

Results

In this work, we showed that both SpdR and SpdS are also induced upon entry into stationary phase, and this induction is partly mediated by ppGpp and it is not auto-regulated. Global transcriptional analysis at early stationary phase of a spdR null mutant strain compared to the wild type strain was carried out by DNA microarray. Twenty-three genes showed at least twofold decreased expression in the spdR deletion mutant strain relative to its parental strain, including cspD, while five genes showed increased expression in the mutant. The expression of a set of nine genes was evaluated by quantitative real time PCR, validating the microarray data, and indicating an important role for SpdR at stationary phase. Several of the differentially expressed genes can be involved in modulating gene expression, including four transcriptional regulators, and the RNA regulatory protein Hfq. The ribosomal proteins NusE and NusG, which also have additional regulatory functions in transcription and translation, were also downregulated in the spdR mutant, as well as the ParE1 toxin. The purified SpdR protein was shown to bind to the regulatory region of CC0517 by Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay, and the SpdR-regulated gene CC0731 was shown to be expressed at a lower level in the null cspD mutant, suggesting that at least part of the effect of SpdR on the expression of this gene is indirect.

Conclusions

The results indicate that SpdR regulates several genes encoding proteins of regulatory function, which in turn may be required for the expression of other genes important for the transition to stationary phase.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12866-016-0682-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Stationary phase, Transcriptional regulation, Two-component system, Caulobacter

Background

The fundamental characteristic of bacterial cells is the ability to regulate their growth in response to environmental changes. The stationary phase in bacteria is characterized by growth arrest in response to several external factors, such as nutrient starvation, accumulation of toxic compounds and environmental stresses. Bacteria utilize varied mechanisms for coping with these situations, but the main effect is the decrease of ribosome activity, resulting in a great reduction in protein synthesis. In order to maintain viability during growth arrest, cells need to reorganize their metabolism, using several regulatory factors to define new protein expression profiles. Proteins produced by cells at the onset of stationary phase are involved in their survival through long periods of nutrient starvation, maintaining only essential cellular functions [1, 2]. In addition, cells acquire greater resistance to stress conditions, including cold shock, oxidative stress and osmotic variations [3].

Changes in gene expression during the transition from exponential to stationary phase respond primarily to the nutritional status of the cell. In Enterobacteria, where response to stationary phase has been well characterized, the major global regulator of this response is the alternative sigma factor σS, which directs transcription of genes involved in stress response, as well as metabolic functions and uptake and metabolism of amino acids, sugars and metals [4]. Transcriptional response to stationary phase is also mediated by the signaling molecule guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp), which binds to RNA polymerase core, destabilizing its association to strong promoters of rDNA genes and therefore releasing the core enzyme for transcription of specific genes [5].

Caulobacter crescentus is an alphaproteobacterium that grows in low-nutrient aquatic environments [6]. After entry into stationary phase, the majority of C. crescentus cells stays in the predivisional-stage and gradually acquires a helicoidal, elongated morphology, with increased stress resistance compared to exponentially growing cells [7]. Transcriptional response and gene regulation during stationary phase is still poorly documented in C. crescentus. Currently, three alternative extracytoplasmic function sigma factors, namely σF, σT, and σU, are known to mediate the bacterial response to stationary phase [8, 9]. Noticeably, σT has been proposed to be the master regulator of general stress response in C. crescentus, therefore playing analogous function of E. coli σS [9, 10]. Furthermore, some small regulatory RNAs are induced in stationary phase by nutrient starvation, suggesting that the regulatory network that controls gene expression in this phase is much more complex [11]. Likewise, the contribution of specific stationary phase-induced genes for C. crescentus adaptation to this growth phase is largely unknown, being mostly limited to katG, which encodes a catalase-peroxidase, cspC and cspD, coding for cold shock proteins [12–16]. cspD encodes a protein of the Cold Shock family containing two Cold Shock Domains, which is induced upon entry into stationary phase [14]. The Cold Shock Domain is composed of two RNP1 sequence motifs that were demonstrated to bind nucleic acids [17]. The CspD protein was implicated in repressing DNA replication in E. coli [18] and it is regulated both transcriptionally [19] and by proteolysis [20] in this bacterium.

Previously, the response regulator SpdR belonging to the two-component system SpdR/SpdS was characterized in C. crescentus by its ability to directly bind the promoter region of the cspD gene and activate its transcription at stationary phase [21]. A conserved aspartic acid residue at position 64 of SpdR is essential for SpdR binding to the cspD promoter, and it was proposed to be the site of phosphorylation by its cognate histidine kinase SpdS. SpdS possesses a transmembrane segment that separates an extracytoplasmic sensor domain from the cytoplasmic autophosphorylation/phosphate transfer domain. In this work, we have characterized the SpdR regulon, providing a start point for understanding how this regulator mediates the adaptation to stationary phase in C. crescentus. We demonstrate that SpdR and SpdS are induced upon entry into stationary phase, and that several genes regulated by this two-component system are involved in adjusting the overall gene expression rate to ensure adaptation to this phase.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

C. crescentus and E. coli strains, as well as the plasmids utilized in this work, are listed in Table S1 (Additional file 1). C. crescentus NA1000 and derived strains were grown at 30 °C in PYE or M2 medium [22]. The media were supplemented with tetracycline (1 μg/ml) for growing strains harboring pRKlacZ290 and kanamycin (5 μg/ml) for strains harboring pNPTS138. Escherichia coli DH5α and BL-21 were used for cloning procedures and protein expression, respectively, and were grown at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani medium [23] supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), tetracycline (12.5 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml) as needed. None of the bacterial strains used in this study required ethical approval to use.

Heterologous expression of His-SpdR and mouse immunization

The coding region (558 bp) of the spdR gene was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides REG-1 and REG-2. The resulting fragment was cloned in vector pET28a in order to express the SpdR protein with a histidine tag (His6-SpdR) in E. coli BL-21, and protein expression was induced at 37 °C in the presence of 300 μM IPTG. Purification of His6-SpdR was carried out using a Ni-affinity column chromatography according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen).

Ten 6-week-old male SPF Balb/c mice were kept five animals/isolator in a free water and food regimen, in a 12 h light/dark cycle, with room temperature at 22 °C. The mice were immunized with four weekly injections of 20 μg purified His6-SpdR and 50 μl Freund’s adjuvant in a total of 100 μl each injection, during 4 weeks. The first immunization was subcutaneous and contained Freund’s complete adjuvant, and the subsequent immunizations were intraperitoneal and contained Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. One week after the last immunization, animals were anesthetized with 80 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xilazin (União Química Farmacêutica, Brazil), and blood was collected by cardiac puncture. Immune sera of 10/10 animals were combined, and tested for specificity in immunoblots. All procedures were approved by the Biomedical Sciences Institute Ethics Committee (Protocol Register 037), and follow the Ethical Principles for Animal Experimentation of the Brazilian Society of Laboratory Animals Science. This work adheres to ARRIVE guidelines (Additional file 2).

Immunoblots

C. crescentus strains NA1000 and ∆spdR were grown at 30 °C in PYE medium and proteins were extracted both at exponential (OD600 = 0.5) and stationary (24 h) phases. Aliquots (1 ml) were centrifuged for 5 min and cells were suspended in Laemmli’s sample buffer. The volume of buffer was calculated according to the optical density of cultures to ensure similar protein concentrations. Proteins were separated in 15 % SDS-polyacrylamide gels, using PAGE Ruler Prestained Protein Ladder (Fermentas) as molecular weight marker. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose filters and immunoblots were carried out as previously described [24]. Briefly, nitrocellulose filters were incubated with mild agitation for 1 h in TBS (10 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) containing 5 % nonfat milk, and then incubated for approximately 16 h with diluted anti-serum (1:50) in TBSTT (TBS with 0.03 % Tween 20, 0.02 % Triton X-100). Filters were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with anti-mouse antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (Sigma), diluted 1:5000 in TBS, followed by color development with 0.5 mg/ml NBT and 0.15 mg/ml BCIP in alkaline phosphate buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl pH 9.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl).

Construction of vector pCA60 and analysis of spdS promoter activity

A PCR using oligonucleotides AUTO-1 and HIST-1 was carried out to amplify a 400 bp fragment (from −1 to −400 relative to the annotated translational start site of spdS). The fragment was cloned into vector pRKlacZ290 previously digested with enzymes EcoRI and BamHI and the resulting construction (pCA60) was introduced into E. coli S17-1 by electroporation, and transferred by conjugation to C. crescentus strains NA1000, ΔspdR and ΔspoT.

Cultures containing plasmid pCA60 were diluted to an OD600 = 0.1 and promoter activity was assessed by β-galactosidase activity assays [25] in both exponential (OD600 = 0.5) and stationary phases (OD600 = 1.2–1.3, 24 h after dilution). All experiments were performed in duplicates from three biological replicates.

DNA microarrays

Cultures of both the parental NA1000 and ΔspdR strains were grown up to early stationary phase (24 h growth, OD600 = 1.2–1.3) in PYE medium. Total RNA was extracted from 10 ml-cultures with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) as instructed by the manufacturer. RNA was quantified with NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific) and 50 μg of each sample were treated with 25 units of DNAse I (Fermentas). Absence of DNA was confirmed by PCR. cDNA was generated with the FairPlay III Microarray Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies), and 24 μg of each sample were purified and precipitated. The Cy3 (Q13108, GE Healthcare) and Cy5 (Q15108, GE Healthcare) Monofunctional Reactive Dyes were used to label NA1000 and ΔspdR samples, respectively. Fluorophores coupling to cDNA was performed in the buffer supplied by the manufacturer, and labeled and purified cDNAs were quantified with NanoDrop 2000.

Each hybridization reaction (NA1000 x ΔspdR) was mounted on 4x44K microarray slides customized for Caulobacter (Agilent Technologies), with the same amount of cDNA for each sample, and slides were incubated for 24 h at 65 °C and 10 rpm. Fluorescence on slides was scanned using the SureScan Microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies), and values of relative expression were obtained through the Feature Extraction Software (Agilent Technologies). The customized slides for Caulobacter include oligonucleotides that hybridize with non-coding regions of the genome; since only coding regions were of our interest in this work, we analyzed only the four last oligonucleotides of a given ORF, which mapped inside the open reading frame. In order to be considered down- or upregulated, a gene must have displayed at least three out of the four last oligonucleotides with Cy5/Cy3 ratio values (mutant/NA1000) below 0.5 (downregulated) or above 2 (upregulated) in at least three out of the four biological replicates. Cy5/Cy3 ratio values from the last four oligonucleotides of all replicates were averaged.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Stationary phase RNA samples (12 μg) of strains NA1000 and ΔspdR were treated with six units of DNAse I (Fermentas), and approximately 3 μg were used as template for cDNA synthesis. Real-time PCR was performed using 50 ng cDNA, 0.1 μM oligonucleotides specific for each gene, and the Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas). Fluorescence emitted was analyzed with the 7500 System SDS Software v.1.2.2 (Applied Biosystems). All oligonucleotides used for this analysis (Additional file 1: Table S1) were designed with the Primer-BLAST software [26] and displayed equivalent amplification efficiency. The 2-ΔΔCT method [27, 28] was utilized to calculate relative expression of genes, with ORF CC3098 as normalizer.

Identification of possible regulatory sequences

Genes identified in the microarray experiments were analyzed in a search for a putative SpdR-binding motif using the “DNA-pattern” module of RSAT (Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools, available at http://www.rsat.eu/) [29]. The sequence CTGCGAC-N5-GTCGCGG, previously found to be directly recognized by SpdR [21], and the sequences better matching to a perfect palindromic motif (CTGCGAC-N5-GTCGCAG and CCGCGAC-N5-GTCGCGG) were utilized as template and up to two substitutions were allowed.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSA)

Promoter regions of genes CC0517 and CC1746 were amplified by PCR with the oligonucleotide pairs SHIFT CC0517 Forward/Reverse and SHIFT CC1746 Forward/Reverse respectively. Probes were end-labeled with 20 μCi [γ-32P] ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen), and DNA-binding reactions were performed in a volume of 30 μl containing 0, 25, 50, 100, 250 or 500 nM purified SpdR protein. In competition assays, a 30x excess of unlabeled specific fragment (specific competitor) was added to the labeled specific fragment; in another reaction, a 30x excess of an unlabeled fragment containing the cspD coding region (non-specific competitor) was used together with the labeled specific fragment. Both reactions were carried out with 50 nM purified SpdR. After incubation at 30 °C for 30 min, samples were run in a 5 % polyacrylamide gel in 0.5X TBE buffer, the gel was subsequently dried and exposed to an X-ray film.

Construction of the mutant strains

For obtaining a ΔCC0517 mutant strain, the flanking regions of gene CC0517 were amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotide pairs HIP-1/HIP-2 and HIP-3/HIP-4, and for the ΔspdR mutant, the flanking regions of gene CC0247 were amplified by PCR using pairs RR1/RR2 and RR3/RR4. The respective fragments were cloned in tandem into pNPTS138, a suicide vector in C. crescentus, and the resulting recombinant plasmids were introduced into E. coli S17-1 and subsequently in C. crescentus NA1000 by conjugation, generating strains MM80 (ΔCC0517) and MM85 (ΔspdR) after double recombination.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using Students’ T-test, and p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results and discussion

SpdR and SpdS induction at stationary phase

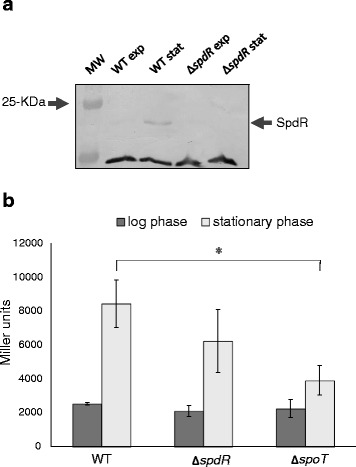

As the SpdR-regulated gene cspD is induced following C. crescentus entry into stationary phase [21], we firstly investigated whether this induction is consequence of an increase in expression of its regulatory protein SpdR at the same growth phase. A polyclonal antiserum raised in mice against His-SpdR was able to recognize the protein in immunoblots. According to immunoblotting assays with the anti-SpdR serum, the levels of SpdR in exponentially growing cells are virtually undetected, but increase dramatically at stationary phase (Fig. 1a). The control lanes show that the protein was absent in the spdR deletion strain. As spdR and its cognate histidine kinase gene spdS were described as not belonging to the same transcriptional unit [30], we further measured spdS expression by assaying the promoter activity of the region upstream of spdS in a lacZ transcriptional fusion. According to this analysis, spdS expression also increases during stationary phase, and this induction was found to be independent of SpdR, since the difference observed was not statistically significant (Fig. 1b). Nonetheless, spdS induction is partially compromised in a spoT null mutant relative to the parental strain, indicating that ppGpp plays a role in regulating this gene, as observed previously for the spdR gene [21].

Fig. 1.

Analysis of SpdR and SpdS expression at stationary phase. a Total proteins from NA1000 and spdR mutant strains were extracted in exponential phase (exp) and stationary phase (stat) in PYE medium and separated by a 12 % SDS-PAGE. Following protein transfer to a nitrocellulose filter, an immunoblot assay was carried out with anti-SpdR anti-serum (1:500), identifying the 21-kDa band corresponding to SpdR. The 25-kDa band of the prestained Molecular Weight marker (MW) is indicated. A non-specific band recognized by the antiserum is shown to allow assessment of the protein concentration in each lane. b The expression driven by the spdS promoter cloned upstream of the lacZ reporter gene was assessed by β-galactosidase activity assays, both in logarithmic and stationary phases. The reporter plasmid was introduced into the C. crescentus strains NA1000, MM85 (ΔspdR) and SP0200 (ΔspoT). Results are the means of three experiments, and bars indicate the respective standard errors. Asterisk indicates a statistical difference between the parental strain and ∆spoT strain at stationary phase (p < 0.01) as determined by Students’ T-test

Previous cDNA microarray studies revealed that SpdR expression varies in response to distinct cultivation conditions. Expression of spdR was higher in M2 medium supplemented with xylose in relation to PYE medium (2.33 fold higher) and M2 containing glucose (1.66 fold higher) [31]. It has also been observed that spdR is induced under conditions of carbon starvation [32] and that the SpdR/SpdS two-component system was induced under chromate and dichromate stress [33]. These reports and the results from this work suggest that C. crescentus SpdR acts on the regulation of target genes to respond to environmental clues that indicate nutrient starvation and stress.

The results indicate that spdS and spdR expression at stationary phase is a result of transcriptional regulation partly mediated by ppGpp, and spdS induction is not dependent on SpdR. Since this transduction system probably works by conveying a signal that results in the phosphorylation of SpdR and its activation, the increase in the concentration of these proteins should amplify the resulting effect on gene regulation.

Determination of the SpdR regulon

With the aim of identifying additional genes to cspD under the control of SpdR, we compared the transcriptional profile of the wild type strain with that of the spdR deletion mutant by DNA microarray experiments. As SpdR is induced at stationary phase and is also necessary for the increase of expression of cspD that happens at this phase, the comparison was carried out with early stationary phase RNA samples. According to this analysis, expression of spdR itself, cspD and 22 additional genes were at least twofold lower in the spdR deletion mutant strain relative to its parental strain (Table 1). Additionally, this comparison showed that an spdR deletion increased the transcript levels of five genes, which have been predicted to encode mostly proteins of unknown function. Interestingly, among these genes, seven were predicted to be essential (CC0653, CC0035, CC0260, CC1247, CC1745, CC2912 were downregulated and CC3655 was upregulated) [34].

Table 1.

Genes differentially expressed in the ΔspdR mutant relative to the wild type strain

| Genea | Fold changeb | Putative functionc |

|---|---|---|

| Downregulated | ||

| CC0035 | 0.229 | Small subunit ribosomal protein S15 |

| CC0247 | 0.163 | Two-component system, response regulator SpdR |

| CC0260 | 0.483 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase beta chain |

| CC0445 | 0.366 | GntR family transcriptional regulator NagR |

| CC0446 | 0.231 | TonB-dependent receptor NagA |

| CC0482 | 0.327 | 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate/homocysteine S-methyltransferase |

| CC0517 | 0.289 | Protein of unknown function |

| CC0583 | 0.380 | Succinylarginine dihydrolase |

| CC0653 | 0.331 | CarD_CdnL_TRCF family transcriptional regulator |

| CC0679 | 0.380 | Abi-domain protein |

| CC0731 | 0.340 | Protein of unknown function |

| CC0873 | 0.385 | Toxin ParE1 from a toxin-antitoxin system |

| CC1005 | 0.354 | Protein of unknown function |

| CC1247 | 0.317 | Small subunit ribosomal protein S10/NusE |

| CC1363 | 0.456 | Membrane-bound proton translocating pyrophosphatase |

| CC1387 | 0.344 | Cold-shock protein CspD |

| CC1745 | 0.291 | RNA-binding protein Hfq |

| CC1746 | 0.312 | GTP-binding protein HflX |

| CC1991 | 0.470 | Preprotein translocase subunit SecD |

| CC2912 | 0.350 | Quinolinate synthetase |

| CC3164 | 0.389 | Cro/CI family transcriptional regulator |

| CC3205 | 0.456 | Transcription antitermination protein NusG |

| CC3268 | 0.455 | Protein of unknown function |

| CC3270 | 0.394 | Cro/CI family transcriptional regulator |

| Upregulated | ||

| CC2114 | 2.331 | Methyltransferase of unknown specificity |

| CC2234 | 2.924 | Protein of unknown function |

| CC3404 | 2.740 | Protein of unknown function |

| CC3654 | 29.412 | Protein of unknown function |

| CC3655 | 17.857 | Malate dehydrogenase |

aAccording to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database for the C. crescentus CB15 genome

bValues are the ∆spdR/WT ratio determined by microarray hybridization of RNA samples isolated from cells at the stationary growth phase (24 h after dilution of culture to OD600 = 0.1). Genes with M value of < 0.5 or > 2.0 were assumed as differentially expressed between strains analyzed. Results shown are the average of four independent biological experiments

cAccording to a reanalysis of the deduced protein sequences by using Pfam [61] and BLASTP [62] to search for conserved domains and proteins with predicted function, respectively

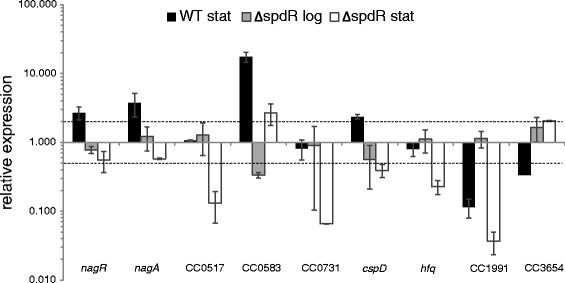

A total of nine genes (eight downregulated genes, and one upregulated gene) were selected for expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (Fig. 2). Accordingly, all the genes analyzed displayed altered expression in the spdR mutant with respect to the wild type when expression was monitored in cells at stationary phase, thus validating the global approach employed to identify SpdR target genes. When the comparison was performed with samples taken from exponentially growing cells, only expression of CC0583 was changed in the absence of spdR. Nonetheless, the fold change in CC0583 expression was still more pronounced at stationary phase. Together, these results are in agreement with the induction of both SpdR and SpdS in the wild type strain at stationary phase, and suggest that regulatory system(s) other than SpdS-SpdR contribute(s) to expression of genes identified in our transcriptome analysis, mainly at exponential phase.

Fig. 2.

Relative expression of SpdR-regulated genes. Expression of the indicated genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR using total RNA samples obtained from the wild type NA1000 and the ∆spdR strain at both exponential and stationary phases. Results represent the expression of each gene in the corresponding strain and growth phase relative to exponentially growing wild type cells. Data represent mean values from two biological replicates, with bars indicating the standard errors

Among those genes downregulated in the spdR mutant, four had their expression increased in the wild type strain after entry into stationary phase (CC0445, CC0446, CC0583, and cspD) (Fig. 2), revealing a crucial role of SpdR in these growth phase inductions. The CC0583 and cspD genes were also previously shown to be induced at stationary phase in a DNA microarray assay [16]. Conversely, the other four downregulated genes either displayed no change in expression in the wild type strain at stationary phase (CC0517, CC0731 and hfq) or had the corresponding transcript levels decreased (CC1991). SpdR also plays a major contribution in regulating these genes at stationary phase, as judged by the lower expression in the spdR mutant relative to the wild type strain. Therefore, the relative importance of other regulatory system(s) for expression of these four genes seems to be reduced when wild type cells enter into stationary phase under the conditions examined. In regards to the gene upregulated in the absence of spdR (CC3654), the expression analysis showed that this effect occurs due to reduction in the transcript levels in the wild type strain at stationary phase, whereas no change is observed in the spdR mutant. Thus, this result suggests that SpdR is required for decreasing CC3654 expression at stationary phase.

A closer inspection of the newly identified SpdR-regulated genes revealed that a substantial percentage of these genes are predicted to encode proteins playing important roles in modulating gene expression. Among the regulatory genes, there are three (CC0445, CC3164 and CC3270) predicted to encode transcriptional regulators, two belonging to the GntR family, whose members act on diverse biological processes, and one to the Cro/CI family [35]. Most if not all transcriptional regulators from these families function as repressors, so it is conceivable to assume that downregulation of these genes in the spdR mutant could lead to increased expression of the five genes in the same strain according to microarray experiments. The GntR-type regulator encoded by CC0445 was previously characterized as NagR, and is located at the nag gene cluster that contains genes required for GlcNAc transport and metabolism [36], probably regulating the utilization of this carbon source.

The downregulated gene CC0653 is predicted to encode a CdnL ortholog, belonging to the large CarD_CdnL_TRCF family of bacterial RNA polymerase-interacting proteins. In contrast to CarD and TRCF from the same family, CdnL lacks a detectable DNA-binding domain [37]. CdnL proteins that had their function investigated were found to promote the formation of the open transcriptional complex, therefore stimulating transcription [38, 39]. All functionally characterized CdnL homologs proved to be essential for bacterial viability [40–42]. Furthermore, CdnL has been implicated in stress resistance, as depletion of the protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to sensitivity to oxidative stress, nutrient starvation and DNA damage [41], and the homologue in Borrelia burgdorferi is expressed exclusively at low temperature, a condition mimicking the bacteria within its arthropod vector [42]. Although no functional data is currently available for C. crescentus CC0653, the presumption that this gene is also required for viability of the bacterium [34] is in accordance to the role reported for other CdnL homologs. CC0653 was previously identified in a DNA microarray analysis as being 2-fold upregulated under iron limitation in a Fur-independent manner [43], indicating to have a role in response to nutrient limitation. Therefore, SpdR could indirectly activate transcription of a subset of genes in starvation conditions by means of the product of CC0653.

CC0035 and CC1247 are predicted to encode the ribosomal proteins S15 and S10, respectively, which are part of the smaller ribosome subunit. Although these genes belong to large operons, only these two genes were differentially expressed, indicating an additional level of regulation. Ribosomal protein S10, also called NusE, has a dual role in the cell, being also involved in transcriptional antitermination [44]. Interestingly, CC3205, predicted to encode NusG, another transcription antiterminator, also had its transcription altered. NusG is necessary for most Rho-mediated termination events in vivo [45, 46] and together with NusA, NusB and NusE promotes readthrough of terminators [44]. The C-terminal domain of NusG binds alternatively the transcriptional terminator Rho or NusE, coupling transcription to translation, so that transcription rates follow those of translation, adjusting the whole system to the nutritional needs of the cell [47–49]. This is particularly important if we consider that the rate of translation is also affected by the presence of secondary structures on mRNA [50]. The fact that both nusE and nusG were differentially expressed could indicate that SpdR mediates the control of transcription and translation rates at stationary phase. This idea agrees with the fact that it also activates expression of CspD, a protein with two putative RNA-binding domains that could have a role in preventing the formation of secondary structures on the mRNA.

The SpdR-dependent gene CC1745 is predicted to encode Hfq, a protein that helps small regulatory RNA to identify and anneal to their target mRNAs, and therefore is an important factor for global gene regulation. It was previously described for E. coli that the cold-shock proteins CspC and CspE, and Hfq positively regulate translation of the stationary sigma factor RpoS [51, 52], indicating that these RNA binding proteins can work in the same pathway of adaptation to stationary phase. Also downregulated in the absence of spdR and in the same transcriptional unit with CC1745, CC1746 is predicted to encode the protein HflX, one of the few members of the P-loop family of GTPases that are distributed throughout all domains of life [53]. Although its exact role remains undisclosed, HflX is currently regarded as a ribosome-associating protein [54–56]. This interaction stimulates GTP binding, GTPase activity and conformational change of HflX [57], all properties expected for a nucleotide-dependent molecular switch with a role in protein synthesis. Interestingly, hflX was not found to be an essential gene in C. crescentus [34], suggesting that the protein plays a more specialized function, and could have a role in responding and adapting to particular adverse conditions such as stationary growth phase. In this regard, HflX could be involved in the translation of a particular set of mRNAs or it may improve the efficiency of the protein synthesis machinery.

Also downregulated in the spdR mutant, CC0873 encodes toxin ParE1 of the toxin-antitoxin system ParD-ParE [58, 59]. The ParE toxin from E. coli plasmid RK2 has been described to inhibit DNA gyrase and thereby block DNA replication [60]. Crystallization studies of the ParD/ParE system encoded by the C. crescentus genes CC0873 and CC0874 showed that system forms an α2β2 heterotetramer in which ParD antitoxin helices bind to a conserved groove on the ParE toxin [58]. Expression of parDE1 was shown to be induced by heat shock, but not in other stress conditions such as heavy metals, nitric oxide-induced oxidative stress or hypoxia [59]. Although the exact function of C. crescentus ParE1 remains to be investigated, it was demonstrated that overexpression of a C-terminal truncated ParE1 allele (ParE1(1–92)) caused loss of viability by inhibiting cell division, but did not affect cell growth [59]. Therefore, the finding that ParE1 expression is dependent on SpdR agrees with the role of toxins on bacterial adaptation to stationary phase. Interestingly, only the parE toxin gene was downregulated in the spdR mutant, although this gene is co-transcribed with parD [30], suggesting an additional regulatory mechanism to overcome the neutralizing effect of ParD1 antitoxin.

Identification of direct targets of SpdR

This overrepresentation of genes encoding regulatory proteins in the SpdR regulon suggests that SpdR might not directly control expression of all genes identified by DNA microarray experiments. Instead, alteration in expression of at least some genes in the spdR mutant could be a consequence of downregulation of one or more SpdR-dependent transcriptional regulators.

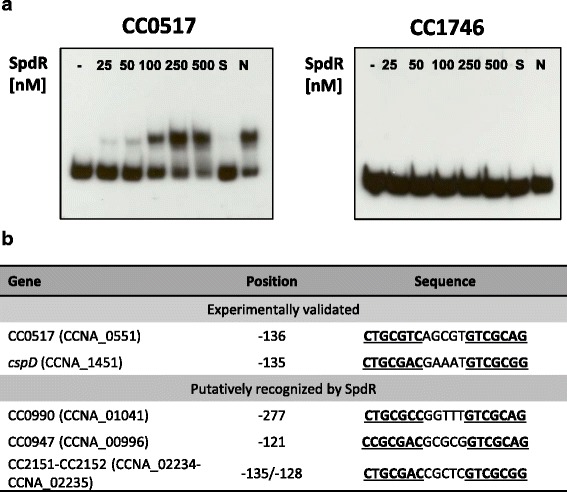

In order to verify whether the SpdR protein directly regulates the expression of the genes identified in the transcriptome analysis, a search for regulatory sequences recognized by SpdR was performed using the RSAT platform (Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools) [29]. The region from −300 to +200 relative to the putative translation start codon of each gene downregulated in the spdR mutant was screened for a sequence similar to that previously identified as the SpdR-binding motif of the cspD promoter region (CTGCGAC-N5-GTCGCGG) [21], allowing for up to two substitutions. This analysis revealed a putative sequence upstream of only two genes in addition to cspD, namely CC0517 and CC1746 (hflX). The sequence upstream of hflX is actually within the coding region of hfq, which is in the same transcriptional unit [30]. Interestingly, when a similar search was performed using a sequence better matching to a perfect palindromic motif (CTGCGAC-N5-GTCGCAG; A instead of G in the position underlined), the sequence upstream of hflX no longer fulfills the cutoff criteria, as three substitutions are needed with respect to the input motif. Using the other possibility to make the sequence upstream of cspD a perfect palindromic motif (CCGCGAC-N5-GTCGCGG; C instead of T in the position underlined), neither CC0517 nor CC1746 would have a SpdR-binding motif.

To establish whether any of the newly identified sequences is truly a recognition motif of SpdR, EMSAs were performed using the purified recombinant His6-SpdR protein. Decreased mobility due to His6-SpdR binding was evident only for the fragment composed of the regulatory region of CC0517, but not for hflX (Fig. 3a). This finding therefore prompted us to suppose that the perfect palindromic motif CTGCGAC-N5-GTCGCAG is the best recognition sequence for SpdR, which deviates in one position in both CC0517 and cspD (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, when a search for the perfect palindromic SpdR-binding motif was carried out in the region from −300 to +200 relative to the putative translation start codon of all C. crescentus NA1000 genes (those not differentially expressed in the absence of spdR according to the transcriptome analysis), only three additional sequences deviating from the input motif in one position were identified (upstream of CC0947, CC0990, CC2151 and CC2152; the latter two genes are divergent from the same sequence) (Fig. 3b). This observation indicates that the SpdR-binding sequence is just occasionally found in the genome of C. crescentus. Therefore, these genes represent candidates to be SpdR-regulated, probably under a distinct condition from the one used in our assays that affects expression and/or activity of this regulatory protein. In fact, both CC0947 and CC2151 were upregulated 3.5-fold at stationary phase in a DNA microarray assay of stationary x exponential phase in PYE [16], and CC0990 also showed increased expression, but it did not fall within our cutoff criteria.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of SpdR binding motifs. a SpdR-binding assays to CC0517 and CC1746. DNA fragments containing the regions upstream of genes CC0517 and CC1746 were 32P-labeled and incubated with increasing concentrations of His6-SpdR (25, 50, 100, 250 and 500 nM) in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). As negative control, a reaction was carried out without His6-SpdR (−). In a competition assay, His6-SpdR was utilized at a 250 nM concentration and a 30x excess of unlabeled competitor fragment was added as follows: S, unlabeled specific fragment; N, unlabeled non-specific fragment. b Sequences recognized by the SpdR protein. An in silico search in C. crescentus NA1000 genome was performed with the consensus CTGCGAC-N5-GTCGCAG derived by the EMSA experiments. The ‘DNA pattern’ tool of RSA website [29] was used in the search, and one substitution was allowed. The position indicated refers to the first nucleotide of the sequence shown relative to the putative start codon in the NA1000 strain (+1). The same sequence is proposed to control expression of CC2151 and CC2152, which are divergently transcribed. The position of this sequence with respect to each gene is shown; for CC2152, the position refers to the nucleotide at the position 3’ of the sequence shown, which corresponds to the 5’ end of the reverse complementary sequence. Gene numbers refer to the CB15 strain (CC) and the correspondent number in NA1000 strain (CCNA)

There is a possibility that SpdR may require additional factor(s) for binding to less conserved sites or even half-sites. However, a whole genome search for half the consensus sequence (CTGCGNC or CNGCGAC) was carried out, and produced too high a percentage of matches to be significant, probably due to the high GC content of the genome. These findings suggest that the probable SpdR-binding site requires a palindromic motif very similar to that found in cspD and CC0517.

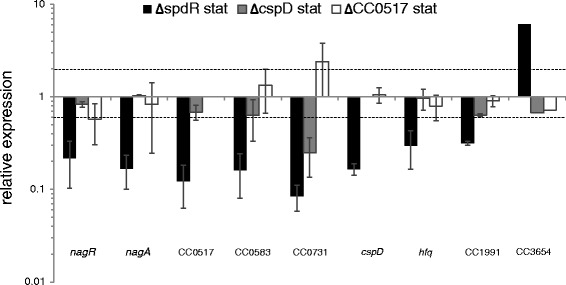

Effect of cspD and CC0517 on expression of SpdR-dependent genes

The restricted number of genes directly regulated by SpdR (cspD and CC0517) identified in this work is in agreement with the overrepresentation of regulatory proteins among the genes dependent on SpdR. The CspD protein has two Cold Shock Domains [14], suggesting it is a putative nucleic acid-binding protein, so it is reasonable to rationalize that it could affect the expression of some SpdR-dependent genes, especially those lacking an obvious motif for SpdR binding. Likewise, even though the function of CC0517 cannot be easily predicted from its deduced amino acid sequence, it could have some relevance for the expression of SpdR-regulated genes. In order to investigate this, a ∆CC0517 strain (MM80) was constructed and analyzed along with a cspD mutant [14] with respect to the expression of several SpdR-dependent genes at both exponential and stationary phases. The MM80 strain showed no obvious phenotype, presenting normal growth rate and showing no alterations in morphology or viability at stationary phase (Additional file 3: Figure S2). This is in agreement with the fact that neither the spdR nor the cspD mutants have a stationary phase phenotype [12, 14, 21].

No differential expression of the SpdR-dependent genes analyzed was observed by comparing ∆CC0517 and ΔcspD to wild type at exponential growth phase (Additional file 4: Figure S1). However, CC0731 was found to be downregulated in the absence of cspD at stationary phase (Fig. 4). This result suggests that CspD is important for CC0731 expression at stationary phase, when SpdR and CspD are expected to play the greatest impact on gene expression. However, the magnitude of the decrease in CC0731 expression is lower when compared to that observed in cells lacking spdR, suggesting that another component in the SpdR network also contributes to the expression of this gene.

Fig. 4.

Expression of SpdR-regulated genes in cspD and CC0517 mutant strains. Expression of the indicated genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR using total RNA samples obtained from the wild type NA1000, ∆spdR, ∆cspD and ∆CC0517 strains at stationary growth phase. Results represent the expression of the corresponding gene in each mutant strain relative to wild type cells. Data represent mean values from two biological replicates, with bars indicating the standard errors

Conclusion

This work has identified genes under control of the response regulator SpdR at stationary phase. The analysis of the putative roles of these genes suggests that the major aspects under SpdR regulation are transcription (mediated by regulators of the GntR, Cro and CdnL families, and NusE/NusG), the coupling of transcription and translation rates (mediated by NusE/NusG) and RNA metabolism (regulatory aspects mediated by Hfq, secondary structures putatively mediated by CspD). Interestingly, only two SpdR-dependent genes contained a sequence motif that is directly recognized by the response regulator. While it is uncertain whether one such gene (CC0517) contributes to the expression of SpdR targets, the involvement of cspD in the downstream effects of SpdR was demonstrated. Together, data presented here provide important insights into the regulatory network involving the response regulator SpdR and identified possible functions under its control, which are expected to contribute to the adaptation of C. crescentus to stationary phase.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, under accession number GSE71337 [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE71337].

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Michael T. Laub for making the C. crescentus DNA microarray slides available, Carla Rosenberg and Andrea Fogaça for assistance with the microarray experiments, and Julian Munoz for assistance with antiserum production. This work was supported by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, grants 2012/10563-0 and 2014/04046-8). During the course of this work, CAPTS, RFL and RRM were supported by postdoctoral fellowship grants 2011/17513-5, 2011/50604-4 and 2011/18847-4 from FAPESP, respectively. RAR was supported by undergraduate fellowship grant 145213/2014-5 and MVM was partially supported by a fellowship grant 306558/2013-0, both from CNPq-Brasil.

Abbreviations

- BCIP

5-bromo-4-chloro-3'-indolyphosphate

- cDNA

complementary DNA synthesized from RNA

- Ct

cycle threshold

- Cy3

Cyanine Dyes orange-fluorescent

- Cy5

Cyanine Dyes far-red-fluorescent

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- His6

Hexahistidine tag

- IPTG

isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- NBT

nitro-blue tetrazolium

- OD600

optical density at 600 nm

- ORF

open reading frame

- PAGE

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ROX

Dye designed to normalize the fluorescent reporter signal in real-time

- rpm

rotations per minute

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SDS

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate

- SYBR Green

asymmetrical cyanine dye

- TBE

Tris/Borate/EDTA

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- WT

wild type

Additional files

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this work. (PDF 296 kb)

The ARRIVE guidelines checklist. (PDF 471 kb)

Phenotypic analysis of the MM80 (ΔCC0517) strain. (PDF 369 kb)

Expression of SpdR-regulated genes in cspD and CC0517 mutant strains at exponential phase. (PDF 302 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

MVM, CAPTS and RFL planned the experiments; CAPTS and RFL, performed and analyzed the microarray and qRT-PCR experiments, RRM performed the DNA-protein binding assays, and RAR conducted the qRT-PCR experiments; MVM, CAPTS, RFL, RRM and RAR analyzed as well as interpreted the data. MVM, CAPTS, and RFL prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Carolina A. P. T. da Silva, Email: croltav@usp.br

Rogério F. Lourenço, Email: lourenco@iq.usp.br

Ricardo R. Mazzon, Email: ricardo.mazzon@ufsc.br

Rodolfo A. Ribeiro, Email: rodolfo.alvarenga.ribeiro@usp.br

Marilis V. Marques, Phone: 55-11-3091-7299, Email: mvmarque@usp.br

References

- 1.Nyström T. Stationary-phase physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:161–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albertson NH, Nystrom T, Kjelleberg S. Macromolecular synthesis during recovery of the marine Vibrio sp. S14 from starvation. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2201–7. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-11-2201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolter R, Siegele DA, Tormo A. The stationary phase of the bacterial life cycle. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:855–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.004231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loewen PC, Hu B, Strutinsky J, Sparling R. Regulation in the rpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44(8):707–17. doi: 10.1139/cjm-44-8-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivatsan A, Wang JD. Control of bacterial transcription, translation and replication by (p)ppGpp. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11(2):100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poindexter JS. Biological Properties and Classification of the Caulobacter Group. Bacteriol Rev. 1964;28:231–95. doi: 10.1128/br.28.3.231-295.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wortinger MA, Quardokus EM, Brun YV. Morphological adaptation and inhibition of cell division during stationary phase in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29(4):963–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez-Martinez CE, Baldini RL, Gomes SL. A Caulobacter crescentus extracytoplasmic function sigma factor mediating the response to oxidative stress in stationary phase. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(5):1835–46. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1835-1846.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lourenco RF, Kohler C, Gomes SL. A two-component system, an anti-sigma factor and two paralogous ECF sigma factors are involved in the control of general stress response in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80(6):1598–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrou J, Rotskoff G, Luo Y, Roux B, Crosson S. Structural basis of a protein partner switch that regulates the general stress response of α-proteobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(21):E1415–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116887109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landt SG, Abeliuk E, McGrath PT, Lesley JA, McAdams HH, Shapiro L. Small non-coding RNAs in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68(3):600–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balhesteros H, Mazzon RR, da Silva CA, Lang EA, Marques MV. CspC and CspD are essential for Caulobacter crescentus stationary phase survival. Arch Microbiol. 2010;192(9):747–58. doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Italiani VC, da Silva Neto JF, Braz VS, Marques MV. Regulation of catalase-peroxidase KatG is OxyR dependent and Fur independent in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(7):1734–44. doi: 10.1128/JB.01339-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang EA, Marques MV. Identification and transcriptional control of Caulobacter crescentus genes encoding proteins containing a cold shock domain. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(17):5603–13. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5603-5613.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rava PS, Somma L, Steinman HM. Identification of a regulator that controls stationary-phase expression of catalase-peroxidase in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(19):6152–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6152-6159.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos JS, da Silva CA, Balhesteros H, Lourenco RF, Marques MV. CspC regulates the expression of the glyoxylate cycle genes at stationary phase in Caulobacter. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:638. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1845-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schindelin H, Marahiel MA, Heinemann U. Universal nucleic acid-binding domain revealed by crystal structure of the B. subtilis major cold-shock protein. Nature. 1993;364(6433):164–8. doi: 10.1038/364164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamanaka K, Zheng W, Crooke E, Wang YH, Inouye M. CspD, a novel DNA replication inhibitor induced during the stationary phase in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39(6):1572–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uppal S, Shetty DM, Jawali N. Cyclic AMP receptor protein regulates cspD, a bacterial toxin gene, in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2014;196(8):1569–77. doi: 10.1128/JB.01476-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langklotz S, Narberhaus F. The Escherichia coli replication inhibitor CspD is subject to growth-regulated degradation by the Lon protease. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80(5):1313–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Silva CA, Balhesteros H, Mazzon RR, Marques MV. SpdR, a response regulator required for stationary-phase induction of Caulobacter crescentus cspD. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(22):5991–6000. doi: 10.1128/JB.00440-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ely B. Genetics of Caulobacter crescentus. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:372–84. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04019-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76(9):4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller JH. Experiments in molecular genetics: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden TL. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmittgen TD. Real-time quantitative PCR. Methods. 2001;25(4):383–5. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Helden J. Regulatory sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3593–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrader JM, Zhou B, Li GW, Lasker K, Childers WS, Williams B, et al. The coding and noncoding architecture of the Caulobacter crescentus genome. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hottes AK, Meewan M, Yang D, Arana N, Romero P, McAdams HH, et al. Transcriptional profiling of Caulobacter crescentus during growth on complex and minimal media. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(5):1448–61. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1448-1461.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Britos L, Abeliuk E, Taverner T, Lipton M, McAdams H, Shapiro L. Regulatory response to carbon starvation in Caulobacter crescentus. PLoS One. 2011;6(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu P, Brodie EL, Suzuki Y, McAdams HH, Andersen GL. Whole-genome transcriptional analysis of heavy metal stresses in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(24):8437–49. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8437-8449.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christen B, Abeliuk E, Collier JM, Kalogeraki VS, Passarelli B, Coller JA, et al. The essential genome of a bacterium. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:528. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigali S, Derouaux A, Giannotta F, Dusart J. Subdivision of the helix-turn-helix GntR family of bacterial regulators in the FadR, HutC, MocR, and YtrA subfamilies. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(15):12507–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenbeis S, Lohmiller S, Valdebenito M, Leicht S, Braun V. NagA-dependent uptake of N-acetyl-glucosamine and N-acetyl-chitin oligosaccharides across the outer membrane of Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(15):5230–8. doi: 10.1128/JB.00194-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallego-Garcia A, Mirassou Y, Garcia-Moreno D, Elias-Arnanz M, Jimenez MA, Padmanabhan S. Structural insights into RNA polymerase recognition and essential function of Myxococcus xanthus CdnL. PLoS One. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rammohan J, Ruiz Manzano A, Garner AL, Stallings CL, Galburt EA. CarD stabilizes mycobacterial open complexes via a two-tiered kinetic mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(6):3272–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srivastava DB, Leon K, Osmundson J, Garner AL, Weiss LA, Westblade LF, et al. Structure and function of CarD, an essential mycobacterial transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(31):12619–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308270110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Moreno D, Abellon-Ruiz J, Garcia-Heras F, Murillo FJ, Padmanabhan S, Elias-Arnanz M. CdnL, a member of the large CarD-like family of bacterial proteins, is vital for Myxococcus xanthus and differs functionally from the global transcriptional regulator CarD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(14):4586–98. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stallings CL, Stephanou NC, Chu L, Hochschild A, Nickels BE, Glickman MS. CarD is an essential regulator of rRNA transcription required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence. Cell. 2009;138(1):146–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang XF, Goldberg MS, He M, Xu H, Blevins JS, Norgard MV. Differential expression of a putative CarD-like transcriptional regulator, LtpA, in Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2008;76(10):4439–44. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00740-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.da Silva Neto JF, Lourenco RF, Marques MV. Global transcriptional response of Caulobacter crescentus to iron availability. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:549. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mason SW, Greenblatt J. Assembly of transcription elongation complexes containing the N protein of phage lambda and the Escherichia coli elongation factors NusA, NusB, NusG, and S10. Genes Dev. 1991;5(8):1504–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cardinale CJ, Washburn RS, Tadigotla VR, Brown LM, Gottesman ME, Nudler E. Termination factor Rho and its cofactors NusA and NusG silence foreign DNA in E. coli. Science. 2008;320(5878):935–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1152763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belogurov GA, Mooney RA, Svetlov V, Landick R, Artsimovitch I. Functional specialization of transcription elongation factors. EMBO J. 2009;28(2):112–22. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burmann BM, Schweimer K, Luo X, Wahl MC, Stitt BL, Gottesman ME, et al. A NusE:NusG complex links transcription and translation. Science. 2010;328(5977):501–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1184953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Proshkin S, Rahmouni AR, Mironov A, Nudler E. Cooperation between translating ribosomes and RNA polymerase in transcription elongation. Science. 2010;328(5977):504–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1184939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGary K, Nudler E. RNA polymerase and the ribosome: the close relationship. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16(2):112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giedroc DP, Cornish PV. Frameshifting RNA pseudoknots: structure and mechanism. Virus Res. 2009;139(2):193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phadtare S, Inouye M. Role of CspC and CspE in regulation of expression of RpoS and UspA, the stress response proteins in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(4):1205–14. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1205-1214.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soper T, Mandin P, Majdalani N, Gottesman S, Woodson SA. Positive regulation by small RNAs and the role of Hfq. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(21):9602–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004435107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caldon CE, March PE. Function of the universally conserved bacterial GTPases. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6(2):135–9. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jain N, Dhimole N, Khan AR, De D, Tomar SK, Sajish M, et al. E. coli HflX interacts with 50S ribosomal subunits in presence of nucleotides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379(2):201–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.12.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polkinghorne A, Ziegler U, Gonzalez-Hernandez Y, Pospischil A, Timms P, Vaughan L. Chlamydophila pneumoniae HflX belongs to an uncharacterized family of conserved GTPases and associates with the Escherichia coli 50S large ribosomal subunit. Microbiology. 2008;154(Pt 11):3537–46. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blombach F, Launay H, Zorraquino V, Swarts DC, Cabrita LD, Benelli D, et al. An HflX-type GTPase from Sulfolobus solfataricus binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit in all nucleotide-bound states. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(11):2861–7. doi: 10.1128/JB.01552-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fischer JJ, Coatham ML, Bear SE, Brandon HE, De Laurentiis EI, Shields MJ, et al. The ribosome modulates the structural dynamics of the conserved GTPase HflX and triggers tight nucleotide binding. Biochimie. 2012;94(8):1647–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dalton KM, Crosson S. A conserved mode of protein recognition and binding in a ParD-ParE toxin-antitoxin complex. Biochemistry. 2010;49(10):2205–15. doi: 10.1021/bi902133s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fiebig A, Castro Rojas CM, Siegal-Gaskins D, Crosson S. Interaction specificity, toxicity and regulation of a paralogous set of ParE/RelE-family toxin-antitoxin systems. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77(1):236–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang Y, Pogliano J, Helinski DR, Konieczny I. ParE toxin encoded by the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 is an inhibitor of Escherichia coli gyrase. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44(4):971–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D222–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evinger M, Agabian N. Envelope-associated nucleoid from Caulobacter crescentus stalked and swarmer cells. J Bacteriol. 1977;132(1):294–301. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.1.294-301.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166(4):557–80. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1983;1:784–91. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gober JW, Shapiro L. A developmentally regulated Caulobacter flagellar promoter is activated by 3' enhancer and IHF binding elements. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3(8):913–26. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.8.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]