Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the perceived usefulness of publicly reported nursing home quality indicators.

Study Setting

Primary data were collected from October 2013 to August 2014 among a convenience sample of persons (or family member) recently admitted or anticipating admission to a nursing home within 75 miles of the city of Philadelphia.

Study Design

Structured interviews were conducted to assess the salience of data on the Medicare Nursing Home Compare website, including star ratings, clinical quality measures, and benchmarking of individual nursing home quality with state and national data.

Data Collection

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, independently coded by two reviewers, and agreement determined. A thematic analysis of transcripts was undertaken.

Principal Findings

Thirty‐five interviews were completed. Eighty‐three percent (n = 29) were caregivers and 17 percent (n = 6) were residents. Star ratings, clinical quality measures, and benchmarking information were salient to decision making, with preferred formats varying across participants. Participants desired additional information on the source of quality data. Confusion was evident regarding the relationship between domain‐specific and overall star quality ratings.

Conclusions

The Nursing Home Compare website provides salient content and formats for consumers. Increased awareness of this resource and clarity regarding the definition of measures could further support informed decision making regarding nursing home choice.

Keywords: Nursing home, public reporting, quality indicators

In response to concerns about low quality of U.S. nursing homes (Institute of Medicine 1986; Wunderlich and Kohler 2000), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services began publicly reporting nursing home quality in 2002 on the Nursing Home Compare (NHC) website, rating each nursing home on 10 clinical quality measures, staffing, and inspections. The goal of this initiative was to support informed decision making for consumers and, by doing so, encourage nursing homes to improve quality of care (Berwick et al. 2003; Stevenson 2006). While there is some evidence of improved nursing home performance (Mukamel et al. 2007; Werner et al. 2009), improvements were small and inconsistent. This inconsistent provider response to nursing home ratings may be in part because consumers have not often used these report cards in their decision making (Kaiser Family Foundation and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2004). Indeed, prior research has shown that public reporting in the setting of nursing homes had little impact on the nursing homes consumers chose (Grabowski and Town 2011; Werner et al. 2012).

One reason for the limited use of quality information in health care decision making is that consumers often find report card information difficult to understand, particularly when there are many individual report card measures. Although consumers generally desire as much information as possible, people have difficulty comprehending rates as well as aggregate and comparative data (Peters et al. 2007). These difficulties may be magnified with regard to nursing home choice, where consumers tend to be older, less comfortable using the Internet to search for quality information, and have declining physical and cognitive abilities. Reducing the amount of information contained in a report card may increase its saliency, reduce the cognitive burden of using the information to make decisions, and increase public trust in quality data (Hibbard and Peters 2003).

To address concerns that the information on NHC was difficult for consumers to interpret (Gerteis et al. 2007), Medicare introduced a five‐star rating system in 2008, giving each nursing home a one to five “star” rating for three domains (health inspections and complaints, staffing, and quality measures) as well as an overall rating. Some evidence suggests that consumers are more responsive to star‐based rating systems in health care, including health plan ratings for Medicare Advantage, with one study finding an association between Medicare Advantage Plan star ratings and health plan enrollment. However, this positive association did not hold true for black, low‐income, rural, and the youngest beneficiaries (Reid et al. 2013).

Data from the first 5 years (2009–2013) of the NHC five‐star rating system suggests that some domains of performance improved over this period of time (AbtAssociates 2014). In 2015, significant changes were proposed for the NHC website, including the addition of an antipsychotic use measure, the collection of staffing data directly from payroll records rather than by self‐report, and scoring system modifications that could shift the proportion of nursing homes scoring at the higher star levels (Thomas 2014).

Despite efforts to increase comprehension of quality data on the NHC website and literature suggesting an association of quality ratings with consumer choice, little is known about whether supplementing individual quality measures with composite star ratings has improved consumers' understanding or use of report card information. The objective of this study was to explore responses to the content and format of quality data conveyed on the NHC website among a socioeconomically diverse sample of consumers and caregivers.

Methods

Study Participants

We conducted structured interviews with consumers who were in the process of choosing or had recently chosen a nursing home for themselves or a family member for long‐term care. Interviews were conducted between the dates of 10/2013 and 8/2014. A purposeful sampling approach was used to include participants diverse in community of residence (urban vs. suburban) and race and ethnicity. Inclusion criteria were (1) admission to a nursing home within the prior 6 months or planned admission over the next 12 months; (2) ability to speak English or Spanish; and (3) self‐identified as the decision maker in the nursing home choice. Exclusion criteria were (1) corrected visual acuity less than 20/70 as indicated by a Rosenbaum vision card (indicating visual acuity sufficient to read print of 14‐point font or greater) and (2) cognitive impairment as indicated by a Mini Mental State Examination; a score less than 23 on this 30‐point scale is indicative of cognitive impairment (Folstein et al. 1975). We recruited participants through outreach to nursing homes, support groups for populations for whom nursing home choice may be relevant, and senior community centers within a 75‐mile radius of the Philadelphia metropolitan area. Additional recruitment was through partnerships with health care professionals at area agencies, clinics, and hospital units that refer patients to nursing homes in the target area. We provided financial incentives in the form of cash to research participants and gift cards to nursing homes that assisted in recruitment.

Study Protocol

We conducted study visits in a private location convenient for the participant. Eligibility criteria were ascertained through a brief phone interview prior to scheduling an interview, and then assessments for cognitive impairment and vision before the interview began. Informed consent was obtained from eligible participants, and an interview was conducted following a script (Appendix S1) that explored participants' awareness of the NHC website, interpretation of hypothetical nursing home report cards (modeled after the NHC website), and how such data would be used by participants in making a nursing home choice (Figure 1, Appendices S2–S4). The interview script was broadly guided by a multiattribute behavioral decision theory framework (Keeny and Raiffa 1993). We sought to determine the attributes consumers valued when choosing a nursing home and how the NHC website informed their nursing home choice. Recruitment continued until the point of saturation when no new themes were emerging in the analysis. The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

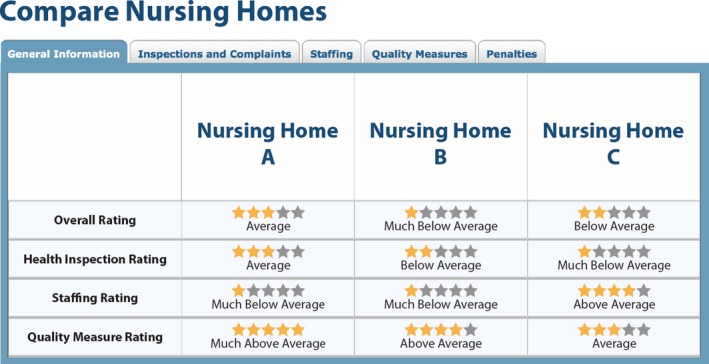

Figure 1.

Nursing Home Compare Star Ratings

Visual Aids Used in Interviews

Participants viewed and discussed four formats, displayed on posters with enlarged font size for quality indicators used on the NHC website (Figure 1, Appendices S2–S4). In screenshot 1 (Figure 1), three nursing homes were compared using five‐star ratings among three domains (health inspections and complaints, staffing, and quality measures) and an overall rating. In screenshot 2 (Appendix S2), star ratings were presented for a single nursing home followed by a list of the 13 clinical quality measures available on the NHC website for long‐stay residents. These clinical quality measures were presented as the percentage of residents with the clinical outcome of interest (e.g., pressure sores) in a tabular format. In screenshot 3 (Appendix S3), two nursing homes were compared using both star ratings and quality measure rates. In screenshot 4 (Appendix S4), star ratings and quality measure rates for one nursing home were benchmarked to state and national averages. After viewing each format, participants were asked to discuss their interpretation and how the quality data would inform their nursing home choice.

Analysis

Interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Transcripts were entered into NVivo, a qualitative software package (NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software version 10; QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). A coding scheme was developed following review by four investigators of a sample transcript and then applied to further transcripts with modifications to capture transcript content. The remaining transcripts were each coded by two independent investigators. A thematic content analysis was conducted. Coding agreement was determined by calculating the kappa statistic, based upon whether a given code was used at least once in each of the structured interviews. Agreement between codes was high. For codes for which kappa's could be calculated, the median kappa was .857, with a range from .211 to 1. We conducted stratified analysis to explore whether views of nursing home quality indicators varied by age, education level, or race. We explored responses to both the content and format of information provided on the NHC website.

Results

Study Population

Thirty‐five interviews were conducted. Eighty‐three percent (83 percent) of interviews were with caregivers and 17 percent with a nursing home resident or anticipated resident. The respondents were diverse. Fifty‐one percent (51 percent) had 4 years of college or more, 26 percent had some college, and 23 percent had a high school education or less. Sixty percent (60 percent) were female, 66 percent were white, and 29 percent black. Fifty‐one percent (51 percent) resided in urban counties and 49 percent in suburban counties (Table 1). Below we review key findings from the study. Illustrative quotations are presented with the race, education level, and interview ID noted for each quotation to demonstrate the range of backgrounds contributing to our findings.

Table 1.

Study Population

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤50 | 8 | 23 |

| 51–59 | 10 | 28 |

| ≥60 | 17 | 49 |

| Race | ||

| White | 23 | 66 |

| African American or Black | 10 | 29 |

| Asian | 1 | 3 |

| Other | 1 | 3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 1 | 3 |

| Non‐Hispanic | 34 | 97 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 14 | 40 |

| Female | 21 | 60 |

| Education | ||

| Up to high school | 8 | 23 |

| Some college | 9 | 26 |

| Four years of college or more | 18 | 51 |

| Role | ||

| Resident | 29 | 83 |

| Caregiver | 6 | 17 |

| Community | ||

| Suburban | 17 | 49 |

| Urban | 18 | 51 |

Prior Experience with the NHC Website

Few participants (<25 percent) were aware of or had prior experience with the NHC website. However, almost half sought out information about nursing homes online. Those who shared their experiences with the NHC site conveyed that it was helpful in the process of choosing a nursing home, as illustrated in the quotation below:

Well, I thought it was very important because when we first started out we really didn't know what there was in the area here, and that government website provided a lot of information. And we could—you know, as we gained more experience with different nursing homes, it's almost like we could validate that the ratings made sense. (White Male, Some College Experience, #7)

Response to the Content and Format of Five‐Star Ratings

Respondents found the content of the five‐star ratings (Figure 1) to be valuable. The overall rating was generally interpreted as a summary indicator of nursing home quality, as illustrated in the quotation below:

I would say overall (is most important) … because everything counts. Health inspections count. Staffing counts. Quality measure. All of that counts … you can't just single out one thing when you're looking at a nursing home. You've got to look at everything. (Black Female, 4 Years of College, #40)

The content provided by the health inspections, staffing, and quality measure five‐star ratings were also valued by consumers. However, participants varied in the domain most salient to their decision as illustrated below:

I would be more concerned about the health inspection … I would just be nervous that my father would catch something, like a staph infection, while he's in there. If it were not clear, I would feel that the food's bad. (White Female, 4 Years of College, #12)

This one (health inspections) … because if you go to a place where somebody inspects the place, they're gonna make sure that it's clean and everything is good to help people there. (Black Female, High School Education, #24)

(Quality measures) … because you know, my goal is for him to be in a facility that would basically give him the same, I would say quality or assistance that I would provide for him at home. And he's receiving that here. (Black Female, High School Education, #23)

Participants found the five‐star ratings format to be familiar, intuitive, and easy to understand as indicated by the following response regarding the use of this format to compare three nursing homes (Figure 1):

Well, the first thing that catches your eye is the star ratings, because we live in a society that stars—the more stars the better. (White Male, Some College Experience, #33)

A source of confusion for many (37 percent) participants was the mathematical relationship between the overall rating composite score and the three components: health inspection, staffing, and quality measure ratings. Participants expected the overall rating to be an average of the three domain‐specific ratings. However, the scoring algorithm used by CMS is more complex than a simple average and is not readily available to respondents. The quotation below illustrates the confusion participants experienced when considering this data (Figure 1):

Well, I'm not quite sure how they wound up with five stars in the quality measure rating section of this nursing home. The overall rating, they've only got three stars and the health inspections, they've only got three. … The staffing rating (is low). So I'm not sure how they would end up with a five‐star rating for overall quality. It's kind of strange. (White Female, 4 Years of College, #32)

Content and Format of Clinical Quality Measure Rates

Participants were next shown a screenshot that had both the five‐star quality measure rating and a list of 13 quality measure rates for a single nursing home (Appendix S2). The quality measure rates include both indicators of good quality (e.g., the percent of long‐stay residents given appropriately the seasonal flu vaccine) and indicators of poor quality (e.g., the percent of long‐stay residents with pressure ulcers). Participants found the content of the quality measure rates to be valuable. Although the list of quality measures was long and in a basic tabular form, most (80 percent) participants expressed interest in viewing the information, with the majority able to identify the specific quality measures salient to their decision, as indicated in the quotations below:

Well, the major injuries and falls are very interesting and important, I think. But I have personal experience with that. That's one of the reasons I moved my mom, because she fell in another facility. (White Male, Some College, #1)

My father … needs help with his daily activities. So it's good to see that the percent's low because I feel that they're helping them be independent. So I like that one. (White Female, 4 Years of College, #12)

A percent of long‐stay residents who lost too much weight (is important to me). Yeah. It sounds like maybe the food's not that hot, or they're not eating. (Black Male, High School Education, #29)

One point raised by several participants regarding the quality measure rates was whether indicators should be attributed to nursing home quality or to the underlying medical condition of the nursing home resident. This concern is illustrated in the quotations below:

I wouldn't be, I guess, quite as concerned about the number of residents who were receiving antipsychotics because, you know, they probably need it. (White Male, Some College, #7)

Well, I think the reporting of pain. I don't—I'm not sure about that one because a lot of people have pain with arthritis and there's no way of really helping that, only to a certain degree. (Black Female, Some College, #28)

One format used by NHC to present quality measures rates is a list of percentages organized in a table. In the screenshot shown to participants, two nursing homes were compared by showing the quality measure rates for 13 indicators side by side (Appendix S3). Participants conveyed that the tabular format was clear. However, one concern raised was the inconsistent direction of the quality measure rates. Higher quality could be indicated by lower values (percent of long‐stay residents experiencing one or more falls with major injury) or higher values (percent of long‐stay residents assessed and given, appropriately, the pneumococcal vaccine), a point that caused confusion in one participant as indicated in the statement below:

So, yeah, those higher numbers jump out. But then, when I read, I look at the number and then I read what they're about, then I realize that a higher number is better, so that's a good thing. (White Male, Some College, #1)

A strategy emerged regarding the integration of information from the five‐star ratings and the quality measure rates. Approximately 25 percent (n = 9) of participants described viewing the general information first, followed by consideration of the more detailed information contained in the quality measure rates as indicated in the examples below:

I would start with the two [nursing homes'] star ratings and then dive deeper. I think the star ratings, like if you're looking at a big long list, the star ratings help you to determine which ones you're going to kick out right away, and then you narrow it down to a smaller scope, and then you can do more of a deep dive. (White Female, 4 Years of College, #9)

I think I would start with the stars and, depending on how many—how the stars are, the overall rating I will probably start with that, and then would go with the quality. (Black Female, 4 Years of College, #40)

In contrast, 20 percent of participants conveyed that the quality measure rates presented too much information and preferred to focus on the general star ratings rather than the longer list of quality measure rates.

Content and Format of Comparative Information

The NHC website provides the content and format to facilitate comparisons between individual nursing homes and between a given nursing home and state and national data. A majority (54 percent) of participants conveyed that state and national comparisons would be helpful in their decision‐making process. The presentation of state and national data provided participants with standards and benchmarks against which to judge data from local nursing homes as illustrated below:

Well, it does provide some context, you know. As to maybe you're in an area that has a lot of very highly rated nursing homes, but compared against each other some might be getting lower ratings than others. This helps provide some context as to, you know, are they still really good, you know, compared to those in other cities or other states. (White Male, Some College, #7)

I think I would pay more attention to that (state comparison) simply because the state has to come in and make sure that they're following regulations and all that so I think, yeah, comparing it to the state or the national I would be more interested in that. (Black Female, Some College, #28)

Others found state and national data to be less relevant to their choice, which often was limited by geographic considerations:

Well, since I really can't pick anything that's outside the county, for example, I'm more interested in comparing the ones locally against themselves. (White Male, Some College, #7)

Three participants noted that culture, standards, and circumstances may differ across regions, limiting the relevance of state and national comparisons:

I would rather have comparisons to other (local) nursing homes … because if you have to compare the oranges and apples to the other oranges and apples, in a whole other state, I mean the sun may not shine and it may not rain more, you know. I think just general right here in the city is fine. (Black Female, High School Education, #23)

The format of side by side comparisons of quality indicators appeared to facilitate cognitive processing of quality data as illustrated in the quotations below:

… like I said, I think it gives you sort of a better understanding of looking at these numbers. Is it care, is it just—if you see the same percentages sort of across the board, you could say, well, it's because it's elderly people that are declining versus, well, I don't know. This nursing home has a lot more falls than this one. (White Female, 4 Years of College, #9)

Among this sample of consumers, comparisons between individual nursing homes were thought to be most helpful among approximately half of participants (49 percent) and comparisons to state and national averages most helpful by approximately a quarter of participants (26 percent).

Recommended Additions to the Quality Reports

Approximately 10 percent of participants recommended that additional information be added to the quality reports, including activities, outdoor space, quality of food, and ratings provided by nursing home residents and their family members, to reflect the residents' experience living in the nursing home, as illustrated in the example below:

The only other thing I might add is, if you can get ratings from family members of people that are there, because sometimes like health inspection ratings, people may not understand that, like how do they—how does state rate that, and why is it low, why is it high, is it improving, did it—you know, there's a lot of behind the health inspection rating. (White Female, 4 Years of College, #9)

I would like to see the patient's report included in some of the reports. How are these people feeling about being in nursing homes? And their opinions, I think, should be most important. (Black Female, 4 Years of College, #35)

Two participants requested greater detail about the data collection process as indicated in the statements below:

I think that this—looking at these components is really, as I said very educational, but in some ways there's still a black box because I'm looking at all of this level of detail, but I still don't have any idea why this is the way it is. (White Female, 4 Years of College, #16)

One question I had asked, who is the one that assessed the stars? Who's measuring these nursing homes? (Black Female, Some College, #13)

Differences by Group Characteristics

In stratified analyses, we found that participants who were older, with lower levels of education, or black were less likely to seek out formal quality information than the other age, education, or racial groups. Of note, 0 of the 10 black participants reported having knowledge of NHC or using it when seeking formal quality information. After reviewing examples of the information available on NHC, fewer participants reported they would have used or plan to use NHC as an information source when choosing a nursing home among those with the lowest compared to highest level of education (38 percent vs. 67 percent) or black compared to white race (40 percent vs. 74 percent). Participants in the lowest level of education (100 percent) were more likely than those in the middle (22 percent) or highest (44 percent) levels to convey that too much information was provided in the format comparing 13 quality measures of an individual nursing home to state and national averages.

Discussion

Our study is the first to explore responses to both content and format of the NHC report card from the perspective of residents, potential residents, and family members who have recently or are actively searching for a nursing home. Most participants identified one or more domains of content and quality indicator formats that were salient to their decision‐making process. With respect to content, participants valued both summary measures of quality and specific quality measure rates. Comparative information was helpful in processing the numeric information and clarifying the values and domains most important to their decision. Although some participants sought only comparisons within the market, a significant proportion valued state and national data as a benchmark of quality. Comparative data appear to support policy objectives of informed consumer decision making.

With respect to format, several approaches used by the NHC website worked well. Star rating formats were generally found to be intuitive and easy to understand. Lists of specific quality measure rates were informative and side‐by‐side comparisons were an effective way of comparing quality between either individual nursing homes or to state and national average ratings. However, our study also reports element of formats used that lead to confusion. In particular, participants struggled to reconcile seemingly conflicting quality data within a given nursing home. For example, the mathematical relationship between the overall rating and the three quality domain ratings summarized with the five‐star rating (health inspections and complaints, staffing, and quality measures) was not a simple average as expected and the relationship between scores was difficult to interpret. Studies have found that information processing becomes more difficult if data are presented in a way that goes against cognitive expectations (Peters et al. 2007). Although changes are being made to the way five‐star ratings are calculated (Thomas 2014), it is not clear that the confusion that emerged in this study is going to be addressed. While simple averages may be easier to understand, they may also have limitations, such as assuming equal weights among each element of the composite. A second approach is to better explain how composite scores are calculated. Despite this confusion, participants valued seeing the individual quality five‐star ratings that were used to develop the composite overall score. They were generally able to focus on the quality measures most important to them, even when nursing homes did well on some measures and not well on others.

Challenges in the use of comparative performance information in medical decision making include the volume of information presented, the need to make trade‐offs, and the need to integrate various factors when making a decision (Hibbard et al. 2001). If the cognitive demand of this process is too great, people will rely on heuristics, or intuitive decision processes that may not lead to an optimal decision (Kahneman and Klein 2009). Presenting the information that is most important and decreasing the cognitive demands to the degree possible are potential solutions to this problem. Composite, or summary, measures are one way to address the overwhelming amount of quality data that could be shared in public reporting (Institute of Medicine 2006; Rothberg et al. 2009). However, relying too heavily on composite measures for decision making may backfire. Our study highlights one limitation to composite measures—they require decisions about how to weight individual components, and these weights are not always congruent with those of the consumers using the composite measures. Some of this could be alleviated if consumers understand how composite measures are created. As is the case with NHC, the algorithms used are often not intuitive and can be difficult to understand. Our study indicates that this level of complexity is a barrier to comprehension of the summary measure. Additionally, composites alone may not provide detailed enough information for consumers to choose a nursing home that best suits their needs. Indeed, about 25 percent of participants noted that composites were most useful to them as part of a two‐stage process—first screening nursing homes using the star ratings and then choosing a nursing home based on the individual ratings.

Our study also highlights some of the limitations of individual measures. For example, cases where some quality measures indicate higher quality (i.e., percent of residents appropriately given the pneumococcal vaccine) and some indicate lower quality (percent of residents with pressure ulcers) can cause confusion. The mixed interpretation of higher rates is counter to cognitive expectations and can decrease comprehension (Peters et al. 2007).

Disparities exist in nursing homes choice, with one study finding that African Americans and those without a high school degree were more likely to be admitted to lower quality nursing homes (Angelelli et al. 2006). It is generally accepted that public reporting should, at a minimum, not exacerbate existing disparities and may be used to alleviate disparities (Konetzka and Werner 2009). However, public reporting could also worsen disparities by causing lower performing nursing homes located in poorer areas to close (Mor et al. 2004). Our study indicates that participants with lower education were more likely to feel that too much information was presented, which could be a barrier to report card use. Indeed, lower health numeracy, health literacy, and patient activation have been associated with poorer understanding of comparative quality information (Hibbard, Peters et al. 2007). It is essential to design report card viewing options that optimize comprehension for persons of lower education and literacy.

The study had some limitations. First, participants responded to screenshots but did not have the full NHC website experience. Navigating the website may have allowed them to select more or less information to view or seek more detailed descriptions of how the data were collected and the summary indicators calculated. Second, the sample was limited to those in Philadelphia and the surrounding area. Although our sample was diverse in age, race, and educational background, the study design did not allow an evaluation of each individual participant characteristic on the outcomes explored. Third, consumers' prior experiences with nursing homes may have affected their responses in our study. We did not collect detailed information on prior nursing home experiences and so cannot fully account for this possibility. Finally, this was a qualitative study and the findings are therefore exploratory. Despite these limitations, the study was strengthened by the use of rigorous qualitative methods and the use of subjects who were actively or recently in the process of choosing a nursing home.

In conclusion, we report that nursing home residents, potential residents, and family members were able to engage with information reflecting the content of the NHC website and found comparative information from both composite ratings and individual quality measures salient to the decision‐making process. However, a more consumer‐friendly tool that conveys a clear relationship between component and summary quality measures could make nursing home report cards a more powerful tool to assist families when choosing a nursing home, especially among those with lower levels of education and literacy. Web designers and policy makers should work together to incorporate principles of risk communication and cognitive psychology with statistical models emerging from health policy research when developing decision support tools for consumers. Studies among users who face these decisions can further inform the design and implementation of public reporting and decision support for nursing home choice.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix S1: Interview Guide.

Appendix S2: Compare Nursing Homes.

Appendix S3: Compare Nursing Homes.

Appendix S4: Nursing Home Profiles.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) R21HS02861. This study also acknowledges support for Dr. Werner from the NIA (K24‐AG047908). There was no requirement from the funder to review work prior to submission.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

References

- AbtAssociates . 2014. “Nursing Home Compare Five‐Star Quality Rating System: Year Five Report (Pubic Version)” [accessed on August 17, 2015]. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/NHC-Year-Five-Report.pdf

- Angelelli, J. , Grabowski D. C., and Mor V.. 2006. “Effect of Educational Level and Minority Status on Nursing Home Choice after Hospital Discharge.” American Journal of Public Health 96 (7): 1249–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick, D. M. , James B., and Cove M. J.. 2003. “Connections between Quality Measurement and Improvement.” Medical Care 41 (1 Suppl): I‐30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M. F. , Folstein S. E., and McHugh P. R.. 1975. “‘Mini‐Mental State.’ A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 12 (3): 189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerteis, M. , Gerteis J. S., Newman D. and Koepke C.. 2007. “Testing Consumers' Comprehension of Quality Measures Using Alternative Reporting Formats.” Health Care Financing Review 28 (3): 31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, D. C. , and Town R. J.. 2011. “Does Information Matter? Competition, Quality, and the Impact of Nursing Home Report Cards.” Health Services Research 46 (6 Pt 1): 1698–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, J. H. , and Peters E.. 2003. “Supporting Informed Consumer Health Care Decisions: Data Presentation Approaches That Facilitate the Use of Information in Choice.” Annual Review of Public Health 24: 413–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, J. H. , Peters E., Slovic P., Finucane M. L., and Tusler M.. 2001. “Making Health Care Quality Reports Easier to Use.” Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 27 (11): 591–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, J. H. , Peters E., Dixon A., and Tusler M.. 2007. “Consumer Competencies and the Use of Comparative Quality Information: It Isn't Just about Literacy.” Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR 64 (4): 379–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . 1986. Improving the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . 2006. Performance Measurement: Accelerating Improvement. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. , and Klein G.. 2009. “Conditions for Intuitive Expertise: A Failure to Disagree.” American Psychologist 64 (6): 515–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . 2004. National Survey on Consumers' Experiences with Patient Safety and Quality Information. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Keeny, R. I. , and Raiffa H.. 1993. Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Tradeoffs. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Konetzka, R. T. , and Werner R. M.. 2009. “Disparities in Long‐Term Care: Building Equity into Market‐Based Reforms.” Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR 66 (5): 491–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor, V. , Zinn J., Angelelli J., Teno J. M., and Miller S. C.. 2004. “Driven to Tiers: Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities in the Quality of Nursing Home Care.” Milbank Quarterly 82 (2): 227–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel, D. B. , Spector W. D., Zinn J. S., Huang L., Weimer D. L., and Dozier A.. 2007. “Nursing Homes' Response to the Nursing Home Compare Report Card.” Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 62 (4): S218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, E. , Dieckmann N., Dixon A., Hibbard J. H., and Mertz C. K.. 2007. “Less Is More in Presenting Quality Information to Consumers.” Medical Care Research and Review 64 (2): 169–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International . 2012. Nvivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, Version 10. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, R. O. , Deb P., Howell B. L., and Shrank W. H.. 2013. “Association between Medicare Advantage Plan Star Ratings and Enrollment.” Journal of the American Medical Association 309 (3): 267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, M. B. , Benjamin E. M., and Lindenauer P. K.. 2009. “Public Reporting of Hospital Quality: Recommendations to Benefit Patients and Hospitals.” Journal of Hospital Medicine 4 (9): 541–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, D. G. 2006. “Is a Public Reporting Approach Appropriate for Nursing Home Care?” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 31 (4): 773–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K. 2014. “Medicare Revises Nursing Home Rating System” [accessed on September 16, 2015]. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/07/business/medicare-alters-its-nursing-home-rating-system.html

- Werner, R. M. , Konetzka R. T., and Kruse G. B.. 2009. “The Impact of Public Reporting on Quality of Post‐Acute Care.” Health Services Research 44 (4): 1169–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, R. M. , Norton E. C., Konetzka R. T., and Polsky D.. 2012. “Do Consumers Respond to Publicly Reported Quality Information? Evidence from Nursing Homes.” Journal of Health Economics 31 (1): 50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich, G. S. , and Kohler P.. 2000. Improving the Quality of Long‐Term Care. Washington, DC: Division of Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix S1: Interview Guide.

Appendix S2: Compare Nursing Homes.

Appendix S3: Compare Nursing Homes.

Appendix S4: Nursing Home Profiles.