Abstract

The deregulation of serine protease activity is a common feature of neurological injury, but little is known regarding their mechanisms of action or whether they can be targeted to facilitate repair. In this study we demonstrate that the thrombin receptor (Protease Activated Receptor 1, (PAR1)) serves as a critical translator of the spinal cord injury (SCI) proteolytic microenvironment into a cascade of pro-inflammatory events that contribute to astrogliosis and functional decline. PAR1 knockout mice displayed improved locomotor recovery after SCI and reduced signatures of inflammation and astrogliosis, including expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), vimentin, and STAT3 signaling. SCI-associated elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 were also reduced in PAR1−/− mice and co-ordinate improvements in tissue sparing and preservation of NeuN-positive ventral horn neurons, and PKCγ corticospinal axons, were observed. PAR1 and its agonist’s thrombin and neurosin were expressed by perilesional astrocytes and each agonist increased the production of IL-6 and STAT3 signaling in primary astrocyte cultures in a PAR1-dependent manner. In turn, IL-6-stimulated astrocytes increased expression of PAR1, thrombin, and neurosin, pointing to a model in which PAR1 activation contributes to increased astrogliosis by feedforward- and feedback-signaling dynamics. Collectively, these findings identify the thrombin receptor as a key mediator of inflammation and astrogliosis in the aftermath of SCI that can be targeted to reduce neurodegeneration and improve neurobehavioral recovery.

Keywords: Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury, Astrogliosis, Inflammation, Cytokine, GPCR, Serine Protease, Astrocyte, Microglia, Interleukin 6

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The aberrant activity of serine proteases, including thrombin is a fundamental feature of many neurological conditions, including hemorrhagic, hypoxic, oncogenic, traumatic and infectious injuries. Elevations can occur due to protease leakage across a damaged blood brain barrier or as a consequence of up regulation by CNS endogenous cells (Cunningham et al., 1993; Scarisbrick et al., 1997; Gingrich and Traynelis, 2000; Scarisbrick et al., 2002; Suo et al., 2002; Junge et al., 2003; Scarisbrick et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2012; Drucker et al., 2013). Thrombin is known well for its ability to cleave soluble fibrinogen releasing fibrin monomers that support hemostasis. In addition, thrombin is a high affinity agonist for Protease Activated Receptor 1 (PAR1), also known as the thrombin receptor (Vu et al., 1991). PAR1 is a seven transmembrane guanosine nucleotide-binding protein (G-protein-coupled) receptor that is activated by protease-mediated hydrolysis within its extracellular N-terminus. While PAR1 has highest affinity for thrombin, it is also activated by plasmin, activated protein C, granzyme A, MMP-1 (Adams et al., 2011), and at least a subset of kallikreins (Vandell et al., 2008; Burda et al., 2013; Yoon et al., 2013). Signaling at PAR1 is emerging as an important translator of the extracellular proteolytic microenvironment into cellular responses that contribute to tissue injury, remodeling and regeneration.

PAR1 over activation is linked to vascular disruption (Chen et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010), neurotoxicity (Smith-Swintosky et al., 1995; Smirnova et al., 1998; Citron et al., 2000; Festoff et al., 2000b; Striggow et al., 2000; Olson et al., 2004; Acharjee et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2013), microglial activation (Nishino et al., 1993; Taoka et al., 2000; Xue and Del Bigio, 2001; Suo et al., 2002), astrogliosis (Nishino et al., 1993; Wang et al., 2002b; Sorensen et al., 2003; Olson et al., 2004; Nicole et al., 2005; Vandell et al., 2008), and in the myelination (Yoon et al., 2015) demyelination (Burda et al., 2013) continuum. The thrombin signaling pathway along with PAR1 were identified as among the top pathways activated in primary astrocytes treated with lipopolysaccharide (Zamanian et al., 2012). PAR1 is therefore well positioned to be a central mediator of the complex and coordinated multicellular responses that unfold in the framework of spinal cord injury (SCI).

There are 4 PARs and each is expressed in the CNS (Striggow et al., 2000). PAR1 is by far the most abundant family member in both the brain and spinal cord (Junge et al., 2004; Vandell et al., 2008). Functional PAR1 expression has been demonstrated in neurons (Niclou et al., 1998; Smirnova et al., 2001; Hamill et al., 2009; Han et al., 2011; Yoon et al., 2013), as well as astrocytes (Junge et al., 2004; Hamill et al., 2005; Nicole et al., 2005; Vandell et al., 2008; Scarisbrick et al., 2012a), and hence our interests in further evaluation of its roles in neurological injury and utility as a target for CNS repair. Excessive PAR1 activation has been implicated in ischemia related pathogenesis (Striggow et al., 2001; Junge et al., 2003; Olson et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Rajput et al., 2014), in HIV- (Boven et al., 2003), and experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) (Kim et al., 2015), in neurodegenerative processes, including tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation (Suo et al., 2003b), in retrograde amnesia following minimal traumatic brain injury (Itsekson-Hayosh et al., 2015), and in traumatic injury to the spinal cord (Citron et al., 2000), the focus of the current study.

Given the abundance of PAR1 activators at sites of CNS injury (Scarisbrick, 2008) taken with their activities in neuropathogenesis we sought to establish whether global targeting of PAR1 would result in improved neurobehavioral outcomes after experimental traumatic SCI. This was accomplished by comparing cellular, molecular and sensorimotor outcomes after contusion compression SCI in PAR1 knockout compared to wild type mice. In addition, primary astrocyte cultures were used to define the potential molecular mechanisms involved. Results show PAR1 is a crucial mediator of inflammation and astrogliosis after SCI and highlight both thrombin and neurosin as key agonists driving astrocyte IL-6 production and STAT3 signaling. Since PAR1 knockout mice also exhibited superior locomotor recovery after SCI results collectively point to PAR1 as a new target for therapy aimed at improving SCI-associated functional outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Experimental contusion-compression SCI

The regulatory role of PAR1 in neurobehavioral recovery after SCI, was examined in twelve-week old (19–23 g) adult female PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− (B6.129S4-F2rtm1Ajc/J) mice. Traumatic SCI was induced by application of a modified aneurysm clip (FEJOTA™ mouse clip, 8g closing force) (Joshi and Fehlings, 2002; Radulovic et al., 2013; Radulovic et al., 2015). This model produces a severe injury with an initial contusion in addition to a persistent dorsoventral compression resulting in robust inflammation and astrogliosis in addition to axon degeneration (Joshi and Fehlings, 2002; Radulovic et al., 2015). PAR1−/− mice were initially obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), and backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for more than 40 generations (Yoon et al., 2015). Uninjured PAR+/+ littermates served as controls. Both acute and more chronic endpoints post-injury were examined including 3, 7 or 30 days after SCI (dpi).

All mice were deeply anesthetized with Xylazine (0.125 mg/kg, Akom, Inc., Decatur, IL) and Ketaset (1 mg/kg, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) prior to spinal cord compression injury. After laminectomy injury induced at the level of L1/L3 by extradural application of the FEJOTA clip for a period of exactly 1 min as recently described in detail (Radulovic et al., 2015). Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) delivered subcutaneously every 12 h for 96 h post-surgery was used to minimize pain. Baytril (10mg/kg, Bayer Health Care, Shawnee Mission, KS) was administered intraperitoneally for the first 72 h post-surgery to prevent infection. Bladders were voided twice daily until the endpoint of each experiment. Any moribund mice were immediately euthanized and excluded from the study. For all studies, mice were randomized with respect to genotype prior to surgery and all investigators blinded to genotype throughout the duration of the experiment. All experiments were carried out with strict adherence to NIH Guidelines for animal care and safety and were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Expression of PAR1 in experimental SCI

To address the significance of PAR1 to SCI pathogenesis, we determined the abundance of PAR1 RNA expression, and that of its main agonists, thrombin and neurosin in RNA isolated from the uninjured spinal cord, or in the 3 mm of spinal cord at the level of the injury epicenter, or in the 3 mm of spinal cord above or below the site of injury site, at 7 or 30 dpi (n = 4 per time point). Each of these specific levels of injury represents a unique microenvironment and therefore we chose to evaluate each individually across the histopathological and molecular outcomes evaluated. Such analysis is consistent with prior histopathological studies (Donnelly et al., 2011). Neurosin is also commonly referred to as kallikrein 6 (Klk6) as well as Zyme, Protease M, or myelencephalon specific protease (MSP) (Scarisbrick and Blaber, 2012). Given the low yield of RNA from sites of injury, particularly at the injury epicenter at 30 dpi, samples from individual mice at a given endpoint and injury level were pooled prior to RNA isolation (Kendziorski et al., 2005; Radulovic et al., 2013; Radulovic et al., 2015). RNA was purified using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) and stored at −70 C until analysis. Amplification of the housekeeping gene 18S in the same RNA samples was used to control for loading. Real-time PCR amplification was accomplished using primers obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA), or Applied Biosystems (Grand Island, NY) on an iCycler iQ5 system (BioRad, Hercules, CA) (Table 1).

Table 1. Primers used for quantitative real-time PCR.

Real time PCR assays used to quantify molecular changes in gene transcription in response to experimental contusion-compression SCI. Unless otherwise indicated, all primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. (AB, Applied Biosystems).

| Gene | Accession Number |

Primer Sequence Forward/Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| BIM | NM_207680 | Probe Assay ID: Mm.PT.56a.8950841.g |

| GFAP | NM_010277.2 | GCAGATGAAGCCACCCTGG/ GAGGTCTGGCTTGGCCAC |

| IL-6 | NM_031168.1 | Probe Assay ID: Mm00446190_m1 (AB) |

| IL-10 | NM_010548.2 | Probe Assay ID: Mm00439614_m1 (AB) |

| IL-1β | NM_008361.3 | Probe Assay ID: Mm.PT.51.17212823 |

| Neurocan | NM_007789.3 | Probe Assay ID: Mm.PT.56a.10993411 |

| Neurosin (Klk6) |

NM_011177.2 | CCTACCCTGGCAAGATCAC/ GGATCCATCTGATATGAGTGC |

| PAR1 | NM_010169.3 | CTTGCTGATCGTCGCCC/ TTCACCGTAGCATCTGTCCT |

| Rn18s | NR_003278.3 | Probe Assay ID: Mm03928990_g1 (AB) |

| TGF-β1 | NM_011577.1 | Probe Assay ID: Mm01178820_m1 (AB) |

| Thrombin | NM_010168.2 | CTGAACCTGCCCATTGTA/ TTCACAAGCATCTCCTCG |

| TNF | NM_013693.2 | Probe Assay ID: Mm00443258_m1 (AB) |

| VIM | NM_011701.4 | Probe Assay ID: Mm.PT.53a.8720419 |

Neurobehavioral outcome measures

Mice were trained in the open field, ladder walk and incline plane test prior to surgery and a baseline for each mouse collected (0 dpi). The open field was used to evaluate seven categories of locomotor recovery using the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS), the day after surgery, and weekly thereafter until 30 dpi generating a maximum score of 9 and a subscore of 0 to 11 (Basso et al., 2006). The ladder walk was used to evaluate sensorimotor coordination. Mice were videotaped crossing a horizontal ladder fitted with an angled mirror to view/record footfalls prior to surgery and on day 8, 15, 22 and 31 after injury. 4 mm rungs of the ladder were spaced between 7.5 to 16 mm apart creating “easy” or “hard” levels of difficulty that included the possibility of 51 or 30 positive events (correctly placed steps), respectively. The left and right hind limbs were scored for positive stepping events (plantar grasping, toe, skip), or foot-faults (miss, drag, spasm) and averaged to determine the total number of positive events for each mouse. The incline plane test evaluates hind limb strength needed to maintain horizontal positioning on an inclining plane, with larger angles associated with better recovery. The last angle each mouse maintained a stance for 5 s before turning was recorded (Joshi and Fehlings, 2002). Incline plane testing occurred after open field-testing weekly post-surgery starting 7 dpi.

Evaluation of histopathological recovery

Histopathological outcomes were quantified at the 32d endpoint of each experiment. Mice were deeply anesthetized (100 mg/kg Nembutal, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL), transcardially perfused with 4% paraformalydehyde (pH 7.2) and dissected spinal cords cut into 3 mm transverse segments. Blocks of spinal cord encompassing the lesion epicenter, in addition to 2 segments above and 2 below, were embedded in a single paraffin block. 6 µm sections were hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained to evaluate spinal cord gray or white matter areas. In addition, the expression of the intermediate filament protein glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, Z0334 Dako, Carpenteria, CA), or the abundance of macrophages/microglia (Isolectin-B, Vector Laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA) (Scarisbrick et al., 2002; Scarisbrick et al., 2006; Scarisbrick et al., 2012b; Radulovic et al., 2015) were quantified using immunoperoxidase techniques. The functional status of corticospinal axons was evaluated using an antibody recognizing the gamma subunit of protein kinase C (PKCγ sc-211 Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) (Bradbury et al., 2002; Lieu et al., 2013). Any impact on ventral horn neurons was evaluated by counts of NeuN-positive neurons (MAB377, Millipore, Billerica, MA) as previously described (Dibaj et al., 2012). Antigen staining in each case was carried out in parallel across genotypes using standard immunoperoxidase methodology as previously described (Scarisbrick et al., 2002; Blaber et al., 2004; Scarisbrick et al., 2006; Radulovic et al., 2013; Radulovic et al., 2015).

Quantification of spinal cord tissue areas and the relative optical density (ROD) of antigen staining was accomplished using KS-400 image analysis software (Carl Zeiss Vision, Hallbermoss, Germany) (Scarisbrick et al., 1999). Stained tissue sections including the SCI epicenter and 2 segments above and below, were captured digitally at 5X (Olympus BX51 microscope and DP72 camera equipped with CellSens software 1.9 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA)), under constant illumination. Area measurements were made from H&E stained sections. ROD readings of immunoreactivity were determined for each antigen at a given segmental level and expressed as a percent of the total area. Since ROD values determined in each of the 2, 3 mm spinal segments examined above or below the injury epicenter were similar the mean in each case was combined for preparation of histograms and statistical analysis. A total of 9 spinal cords from PAR1+/+ and 8 spinal cords from PAR1−/− mice with SCI were stained and quantified. Four PAR1+/+ and 4 PAR1−/− uninjured controls were examined in parallel. Statistical differences between groups were compared using One Way ANOVA and the NK post hoc test, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Immunofluorescence techniques were used to evaluate the association of PAR1, thrombin or neurosin with astrocytes or activated microglia/monocytes in the intact spinal cord or at 30 dpi. PAR1 was localized using a goat polyclonal antibody (H-111, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz CA), thrombin with a rabbit polyclonal (LS-C118750, Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA), and neurosin using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Rb008) (Scarisbrick et al., 2012a; Radulovic et al., 2013). Any co-localization with GFAP was determined using anti-chicken GFAP (ab4676, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), or with microglia/monocytes using anti-rat Isolectin B (IsoB, B1205, Vector Laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA). In each case, antibody binding was visualized using a species appropriate fluorochrome conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). All sections were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and imaged at 80× using an inverted confocal microscope (LSM 780, Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC., Thornwood, NY).

Evaluation of molecular signatures of injury and repair

Protein expression

The impact of PAR1 gene knockout astroglial scar formation at 3 and 30 dpi was determined by quantifying changes in expression of the astroglial intermediate filament proteins, GFAP and vimentin (Wilhelmsson et al., 2004). Changes in expression were quantified at the level of the injury epicenter as well as above and below. In addition, since STAT3 plays an essential role of STAT3 in SCI-induced astrogliosis (Herrmann et al., 2008; Wanner et al., 2013), we examined its activation status in parallel to gain insight into the potential signaling pathways involved. Protein isolation was facilitated by combining the 3 mm of spinal cord at a given segmental level (Above, Epicenter or Below), from 3 to 4 mice at either 3 or 30 dpi prior to collective homogenization in radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer. Protein samples (25 µg) from PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− mice were resolved on 10% to 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels in parallel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose. Multiple membranes were sequentially probed for antigens of interest, including GFAP (ab7260, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), vimentin (10366-1-AP, Proteintech, Chicago, IL) and the phosphorylated or total protein forms of STAT3 (sc-8059, sc-8019, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA,). All Western blots were re-probed with an antibody recognizing β-actin (NB600-501, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) to control for loading. Signal for each protein of interest in samples derived from PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− mice were detected on the same film using species appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshier, UK) and chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The ROD of bands in each case was quantified with Image Lab 2.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The ROD of each protein of interest was normalized to that of actin and the mean and s.e. of these raw values across 3 to 4 separate Western blots used for analysis of the significance of the changes observed and for preparation of histograms.

RNA transcription

The potential impact of PAR1 gene deletion on molecular signatures of SCI and repair was determined at the level of gene transcription using real time PCR. We specifically examined changes in cytokine, structural protein and apoptosis marker levels in spinal segments at the injury epicenter, above, or below at 7 or 30 dpi. The specific probes and primers used to evaluate astrogliosis (GFAP, vimentin or neurocan), cytokines (TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, TGF-β or IL-10), and the pro-apoptotic marker BCL2-interacting mediator of cell death (BIM), are provided in Table 1. In the case of each gene of interest, samples from uninjured PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− mice at a given segmental level, were amplified in parallel. Statistical comparisons of changes in RNA transcription observed at the injury epicenter, above or below, were made relative to that in the spinal cord of uninjured genotyped matched controls. In addition, potential differences in the baseline levels of each gene in the uninjured spinal cord between PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/− mice were examined. To facilitate interpretation of the data, histograms presented show injury-related changes in transcription expressed as a percent of the uninjured genotype control. However, to visualize any specific differences between PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/− at baseline, gene transcript levels in the spinal cord of PAR1−/− uninjured mice are presented as a percent of that observed in their PAR1+/+ counterparts.

Astroglial cultures

Primary astrocyte cultures derived from PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− mice were used to determine the role of PAR1 in regulating the expression of key hallmarks of astrogliosis and whether STAT3 signaling may be involved. Primary astrocytes were purified from mixed glial cultures prepared from the cortices of postnatal day 1 mice as previously detailed (Scarisbrick et al., 2012a; Burda et al., 2013; Yoon et al., 2013). Mixed glial cultures were grown in DMEM, 2 mM Glutamax, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 20 mM HEPES, and 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA). After 10 days in vitro contaminating oligodendrocyte progenitor cells were removed by overnight shaking and microglia subsequently removed by sequential panning on non-tissue culture treated plastic. Remaining astrocytes were 97.8% pure based on immunoreactivity for aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member L1 (ALDH1L1, ab87117, Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Immunofluorescence was used to verify expression of PAR1 by cultured astrocytes by co-labeling cells with PAR1 (SC8202, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) and ALDH1L1, or GFAP (C9205, Sigma, St. Louis, MO. Astrocytes were plated across poly-L-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) coated 6 well plates in the serum containing media at a density of 4.5 × 105 cells per well. After 24 h, media was replaced with defined Neurobasal A media containing 1% N2, 2% B27, 50 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mM Glutamax, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.45% glucose, and 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma Aldrich, USA). All cells were maintained at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2, and all cell culture experiments were repeated independently at least 3 times.

Purified PAR1+/+ astrocytes were used to determine the impact of the PAR1 agonists thrombin (135 nM, Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) or neurosin (Klk6, 150 nM) on the expression of GFAP, vimentin or IL-6 using real time PCR. Neurosin was expressed, purified and activated as previously described (Scarisbrick et al., 2011; Scarisbrick et al., 2012a). In addition, to gain insight into potential regulatory networks, we examined the ability of each PAR1 agonist to regulate PAR1 RNA, or the transcription of their own, or each other’s gene. Any impact of the astrocyte-related pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 (20 ng/ml, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD) was examined in parallel (Table 1). In addition, astrocyte culture supernatants were collected and used to determine any impact on IL-6 secretion using Enzyme Linked Immunosorbant Assay (ELISA) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). All astrocyte cultures were treated in triplicate for 24 h.

Since both thrombin and neurosin were found to robustly stimulate astrocyte IL-6 secretion, we sought to clarify the extent to which this was dependent on intact PAR1 and whether STAT3 activation also occurred. For this purpose, primary astrocyte cultures from PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− mice were treated with thrombin (135 nM), or neurosin (150 nM), for 24 h as described above. Cell culture supernatants were collected for quantification of IL-6, in addition to TNF and IL-1β by ELISA and astrocytes harvested into radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer for quantification of STAT3 activation by Western blot.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of histological and molecular outcomes across multiple groups was determined using One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with the NK post-hoc test or non-parametric ANOVA on RANKS with Dunn’s test. Statistical differences between two groups were determined with Students t-test or Mann-Whitney U for non-parametric data. To evaluate the impact of genotype on sensorimotor outcomes after injury over time, BMS scores and subscores, ladder walk and incline plane test results were analyzed using a Two-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA with fixed effects and the Newman Keuls (NK) post-hoc. All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.). In each case, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Regulation of PAR1 and its agonists after SCI

To determine the contribution of PAR1 to the pathogenesis of traumatic SCI, we quantified changes in PAR1 RNA within the injury epicenter and in segments above and below at acute (7 dpi) and chronic (30 dpi) time points (Figure 1, A–B). At 7 dpi, PAR1 RNA expression was increased by 1.7-fold in spinal segments below the level of injury (P < 0.001, NK). By 30 dpi, PAR1 RNA expression was increased by 1.4- to 1.5-fold at the injury epicenter and above (P = 0.04, NK). The PAR1 agonists, thrombin and neurosin were also up regulated at acute and more chronic time points after SCI. The largest increases in thrombin were seen acutely when 6-fold increases were observed in the injury epicenter (P < 0.001). Thrombin remained elevated at 30 dpi by as much as 2-fold and similar 2-fold elevations were also observed in neurosin at 7 and 30 dpi (Figure 1, C-F, (P ≤ 0.03, NK). By contrast, in PAR1−/− SCI did not elicit changes in neurosin expression at any time point and those in thrombin were restricted to the more acute period of injury examined (P < 0.001, NK).

Figure 1. The expression of PAR1, thrombin and neurosin (Klk6) are elevated in response to contusion-compression SCI.

Histograms show transcriptional changes in RNA encoding PAR1, thrombin or neurosin in the spinal cord of uninjured control (C) PAR1+/+ mice, or at the level of the injury epicenter (E), above (A), or below (B), at 7 and 30 dpi (A – F). Transcriptional changes after injury are expressed as a percent of the uninjured genotype control and these data were used for statistical comparisons. Injury induced elevations in thrombin (C, D) or neurosin (E, F) were reduced or absent in mice lacking the PAR1 gene. Expression levels of thrombin and neurosin in uninjured PAR1−/− spinal cord are expressed as a percent of that seen in PAR1+/+ mice and no significant differences were observed. (*P < 0.03; **P = 0.009, ***P ≤ 0.001 NK; ND, not detected).

Cellular co-localization of PAR1 and its agonists in astrocytes and microglia/monocytes after SCI

To begin to address the possible cellular mechanism(s) by which PAR1 contributes to inflammation and astrogliosis we assessed co-localization between PAR1 and its agonists (thrombin and neurosin) with astrocytes or microglia/monocytes in the intact spinal cord or at 30 dpi (Figure 2). Mirroring transcriptional elevations (Figure 1), immunoreactivity for PAR1, thrombin and neurosin were each increased within the SCI epicenter at 30 dpi. Before SCI, GFAP+-astrocytes expressed low levels of PAR1, thrombin and neurosin. By 30 dpi, we observed the expected increase in the number of GFAP+-astrocytes and demonstrate a subset of these cells were co-labeled for PAR1, thrombin or neurosin. Immunoreactivity for IsoB+ microglia/monocytes was essentially absent in the uninjured spinal cord. While IsoB is also present on endothelial cells such labeling was not prominent in our preparations. At 30 dpi, there was a massive increase in the field of IsoB+-cells, and a subset of these was also co-labeled with PAR1 or neurosin.

Figure 2. The expression of PAR1, thrombin and neurosin increase differentially in astrocytes and microglia/monocytes in response to SCI.

Photomicrographs show co-localization of PAR1 (A, B), Thrombin (C, D) and Neurosin (E, F) with GFAP+ astrocytes or IsoB+ microglia/monocytes, in the uninjured spinal cord (Control) or within the injury epicenter at 30 dpi. Immunoreactivity for PAR1, thrombin, neurosin, GFAP and IsoB were all increased in the SCI epicenter at 30 dpi. PAR1, thrombin and neurosin were each localized to astrocytes in the uninjured spinal cord with an increase in co-colonization after injury. IsoB+ microglia/monocytes were also co-labeled for PAR1 and neurosin but not thrombin. Examples of double labeled cells in each case are shown at arrowheads (Scale bar = 20 um).

PAR1 gene deletion results in improved motor recovery after SCI

Before injury, wild type and PAR1−/− mice displayed identical patterns of motor activity in the open field test, on ladder walk, and in the incline plane test (Figure 3, A–E). The day following contusion-compression injury, both groups were equally impaired in the open field test with a mean BMS score of 1.5 ± 0.5 in PAR1+/+ and 1.7 ± 0.6 in PAR1−/− mice. Across both groups mice began to show significant improvements in BMS scores by 7 dpi, with progressive increases thereafter. Recovery in BMS scores in PAR1−/− mice was significantly higher than PAR1+/+ mice at 14 dpi through 30 dpi (P ≤ 0.005, NK). At the 30d endpoint, BMS scores in PAR1−/− were an average of 2.1 points higher than their wild type littermates. Improvements in BMS subscores were first observed in both groups by 14 dpi, with those in PAR1−/− significantly higher than those in PAR1+/+ mice from 14 dpi onward (P ≤ 0.008, NK). At the 30 d endpoint, BMS subscores in PAR1−/−−/− were an average of 3.2 points higher than their wild type littermates.

Figure 3. PAR1 gene deficient mice show improved locomotor recovery after experimental contusion-compression SCI.

(A) Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) scores evaluated in PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/− mice from 0 to 31 d after SCI, demonstrate significant improvements in over-ground locomotion. Significantly higher levels of recovery on the BMS were observed in PAR1−/− mice at 14 dpi (P = 0.005) and at each time point thereafter (P < 0.001). (B) BMS subscores were significantly higher in PAR1−/− compared to PAR1+/+ mice starting on 14 dpi (P = 0.008) and continuing through the last time point examined (P < 0.001). (C, D) Improvements in stepping accuracy in the easy and hard rung spacing ladder walk tests were observed at 31 dpi (P ≤ 0.01). Improvements in ladder walk accuracy were also observed at 22 dpi in PAR2−/− relative to PAR2+/+ mice in the hard set up (P = 0.04). (E) PAR2−/− mice showed significantly better motor strength in the incline plane test at 14, 21 and 30 dpi relative to that observed in PAR2+/+ mice (P ≤ 0.02). Data shown represents the mean and standard error of results obtained across two independent experiments, PAR1+/+, n=16; PAR1−/− n=9. (Two Way Repeated Measures ANOVA, NK *P ≤ 0.04, **P ≤ 0.008, ***P < 0.001).

Significant improvements in the easy ladder walk test were observed by 22 dpi, with PAR1−/− mice showing significantly higher levels of recovery at this time, and at 31 dpi (P ≤ 0.04, NK, Figure 3C). Significant improvements in the number of positive events achieved by PAR1−/− relative to PAR1+/+ mice was also observed on the hard ladder walk test by 22 dpi and at the 31 day endpoint (P = 0.01, NK, Figure 3D). Significant improvements in the Incline plane test (over those observed at 7 dpi) were observed in PAR1−/− (P = 0.03) but not PAR1+/+ mice by 14 dpi (Figure 3E). PAR1+/+ showed improvements in the incline plane test by 21 and at 30 dpi relative to that observed at 7 dpi (P ≤ 0.02). Notably, higher mean maximal angles were achieved by PAR1−/− compared to wild type mice at 14, 21 and 30 dpi (P ≤ 0.02, NK).

PAR1 gene deletion is associated with improvements in neuropathological outcomes

Spinal cord areas in intact mice and after SCI were quantified in H&E stained sections at the level of the injury epicenter, above and below at the 32 day endpoint of each experiment (Figure 4A). As expected, compression injury resulted in a significant reduction in spinal cord area at the level of the injury epicenter and below in both PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/− mice (P < 0.001, NK). No significant changes in spinal cord area were observed after compression SCI in spinal segments above the epicenter. Tissue preservation at the injury epicenter was improved in mice lacking PAR1 in which the decrease in area relative to control was 35% compared to 57% seen in wild type mice (P < 0.3, NK). There were no significant differences in spinal cord tissue loss below the injury epicenter across the genotypes examined.

Figure 4. PAR1 gene deletion is associated with reductions in inflammation, astrogliosis and improvements in neural preservation after experimental contusion-compression SCI.

Photomicrographs and associated histograms show measurements of spinal cord areas taken from H&E stained sections (A), or the percent of spinal cord area immunoreactive for GFAP (B), or Isolectin B-IR (IsoB) microglia/macrophages (C), at the 32d endpoint of each experiment. The % area at the base of the dorsal column white matter stained for PKCγ, as a measure of corticospinal axon function (D), and counts of NeuN positive neurons in the ventral horn (E), were also evaluated. In each case, measurements were made in spinal cord sections taken from the level of the injury epicenter (E), above (A), or below (B). Arrows B to E indicate an example of immunostaining in each case. In mice lacking PAR1 there was a significant increase in tissue sparring at the level of the injury epicenter (A), reductions in GFAP-IR at the injury epicenter and above (B), and reductions in IsoB-IR at the level of injury (C). In addition, PAR1−/− mice also showed significant increases in preservation of PKCγ-IR in spinal segments below the level of injury (D) and in NeuN positive ventral horn neurons above the level of injury (E) (for PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/−, n=3 uninjured and n=8 compression SCI); *P < 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 NK). Scale Bar A = 250 µm; B to D = 100 µm and E = 20 µm.

To begin to address whether the absence of PAR1 impacted inflammation and astrogliosis after SCI, we quantified immunoreactivity (IR) for GFAP or for Isolectin B, at 32 dpi (Figure 4B and C). As expected, GFAP-IR in wild type mice was increased 1.5 to 3-fold in response to compression SCI in the injury epicenter, above and below (P < 0.03, NK). Significant elevations in GFAP-IR were also observed in PAR1−/− mice at each level of injury, but that in the injury epicenter and above were attenuated (P ≤ 0.002). In addition, elevations in immunoreactivity for Isolectin B that persisted in the injury epicenter at 32 dpi, were substantially lower in mice lacking PAR1 (P = 0.002). The functional status of the corticospinal tract was assessed using immunoreactivity for PKCγ (Figure 4D) (Mori et al., 1990; Bradbury et al., 2002; Lieu et al., 2013). Significant reductions in PKCγ-IR were observed in the injury epicenter and below (P < 0.001, NK). The injury-associated-reductions in PKCγ observed below the level of injury were reduced in PAR1−/− mice (P ≤ 0.001, NK). The potential impact of PAR1 gene deletion on neuron preservation after SCI was evaluated by making counts of NeuN-positive neurons in the ventral horn (Figure 4E). A significant loss of NeuN-positive neurons was observed after SCI at all segmental levels examined (P < 0.001, NK). The loss of NeuN neurons was significantly attenuated above the level of injury in mice lacking the PAR1 gene (21.8 ± 1.4% loss) relative to PAR1+/+ mice (38.2 ± 0.9% loss) (P = 0.002, NK).

PAR1 gene deletion reduces hallmarks of SCI-driven astrogliosis in vivo

Quantitative Western blot was used to further document the impact of PAR1 gene deletion on molecular hallmarks of astrogliosis commonly seen after SCI, including GFAP and vimentin (Lepekhin et al., 2001; Pekny and Pekna, 2004; Wilhelmsson et al., 2004) and the potential signaling pathways involved (Figure 5A). Substantial elevations in GFAP protein were observed after SCI at both acute stages (3 dpi) and more chronic (30 dpi) time points (P ≤ 0.02, NK). The substantial elevations in GFAP in the injury epicenter and below at 3 dpi in PAR1+/+ mice were completely absent in PAR1−/− (P ≤ 0.001, NK). Vimentin protein levels, another intermediate filament protein involved in astrogliosis, were below the detection limit of the Western before injury and at 3 dpi (Figure 5C). Large elevations in vimentin protein were evident by 30 dpi when significant increases were observed in the injury epicenter (67-fold) and below (15-fold) in wild type mice (P ≤ 0.001, NK). Injury-induced elevations in vimentin were absent in mice lacking PAR1 (P < 0.001).

Figure 5. Spinal cord injury-associated elevations in GFAP, vimentin and STAT3 signaling were reduced in PAR1 gene deficient mice.

Western blots and corresponding histograms show differential expression of GFAP, vimentin (VIM), pSTAT3 and STAT3 in the uninjured (C, Control) or injured PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− spinal cord at 3 or 30 dpi. Protein samples isolated from the injury epicenter (E), above (A), or below (B) from PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− mice were examined in parallel with uninjured samples in each case and results developed on the same film. SCI-induced elevations in GFAP, vimentin and pSTAT3 were all significantly reduced in mice lacking the PAR1 gene. In some cases, multiple bands for GFAP or vimentin were detected after SCI and the band used for quantification is shown at the arrowhead in each case. Histograms show the mean and standard error of ROD readings across multiple membranes (n = 3 to 4) normalized to Actin as loading control. (*P < 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 NK).

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a signal transduction pathway participating in the response of the CNS to injury, including inflammation (Kim et al., 2002; Dominguez et al., 2010) and astrogliosis (Okada et al., 2006; Herrmann et al., 2008). Given that the absence of PAR1 reduced both inflammation and astrogliosis seen after SCI we assessed whether STAT3 signaling was impacted in parallel. As expected based on prior studies involving experimental SCI (Herrmann et al., 2008; Wanner et al., 2013), activated STAT3 levels were increased in PAR1+/+ mice at 3 and 30 dpi (P ≤ 0.02, NK, Figure 5D). Notably, levels of activated STAT3 seen below the injury epicenter at 3 dpi, and at the epicenter 30 dpi, were significantly reduced in mice lacking PAR1 (P ≤ 0.001 NK).

PAR1 agonists promote STAT3 signaling in primary astrocytes

Primary astrocyte cultures were used to critically evaluate the extent to which reductions in STAT3 signaling observed after SCI in PAR1−/− reflect changes occurring at the level of the astrocyte (Figures 6 and 7). First, we used the pan astrocyte marker ALDH1L1 to demonstrate that astrocyte cultures were 97.8 ± 0.6% pure and 96.2 ± 1.0% PAR1-immunoreactive. Of interest only 74.1 ± 4.9% of cells in these cultures were immunopositive for GFAP, underscoring the concept that GFAP, a marker of astroglial reactivity, incompletely identifies all astrocyte phenotypes in cell culture.

Figure 6. Primary astrocytes express PAR1 in vitro.

Photomicrographs show PAR1 expression by (A) ALDH1L1-, or (B) GFAP-immunoreactive astrocytes in cell culture. (C) Histogram shows the percent of total DAPI+ cells in each case. 98.5% of all of the DAPI+ cells were positive for the pan astrocyte marker ALDH1L1, indicating that astrocyte cultures are of high purity. 74% of all of the DAPI+ cells were positive for the marker of astrocyte reactivity, GFAP. PAR1 immunoreactivity was localized to 96% of the DAPI+ cells. Examples of doubly labeled cells are provided at arrow and singly labeled cells at arrow head. (*P < 0.05, NK). Scale bars A, B = 50 µm.

Figure 7. Thrombin and neurosin increase astrocyte STAT3 signaling in a PAR1-dependent manner.

Treatment of astrocytes with (A) thrombin or (C) neurosin (150 ng/ml) for 24 h resulted in a significant increase in pSTAT3 in PAR1+/+, but not PAR1−/− astrocytes (B and D show corresponding signal for total STAT3 in each case). (*P < 0.05, Students t-test).

Treatment of PAR1+/+ astrocyte cultures with either neurosin or thrombin for 24 h each elicited activation of STAT3 in the range of 2 to 10-fold respectively (P ≤ 0.04, Students t-test). STAT3 activation by thrombin and neurosin was completely blocked in primary astrocytes lacking PAR1 (Figure 7).

PAR1 regulates molecular signatures of inflammatory-astrogliosis and apoptosis in experimental traumatic SCI

Astroglia-associated RNA transcription

The impact of PAR1 gene deletion on SCI-associated astrogliosis was further evaluated by determining changes in GFAP, vimentin and neurocan gene transcription at acute (7 dpi) and more chronic (30 dpi) time points after injury (Figure 8 A–H). Among the key indices examined, the intermediate filament protein vimentin was transcriptionally most dynamic reaching levels 30 to 48-fold higher than uninjured controls in the injury epicenter at 7 and 30 dpi, respectively (P ≤ 0.001 NK, Figure 8C–D). Parallel, albeit lower elevations in vimentin transcription were seen at the same time points above and below the injury epicenter, where increases were 5- to 14-fold that seen in the intact spinal cord. At both acute and more chronic time points after injury, mice lacking PAR1 showed significantly reduced elevations in vimentin RNA within the injured spinal cord relative to PAR1+/+ mice (P ≤ 0.05, NK). Vimentin RNA levels were slightly higher in PAR1−/− compared to PAR1+/+ spinal cords at baseline (P = 0.01, NK).

Figure 8. Spinal cord injury-induced elevations in markers of astrogliosis and apoptosis were reduced in mice lacking the PAR1 gene.

Histograms show transcriptional changes in RNA encoding GFAP (A, B), vimentin (VIM, (C, D)), neurocan (NCAN, (E, F)), and BIM (G, H) in the spinal cord of PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− uninjured controls (C), or in the 3 mm of spinal cord surrounding the injury epicenter (E), or that above (A), or below (B), at 7 and 30 dpi. The RNA expression levels shown are expressed as a percent of the uninjured genotype control and these data were used for statistical comparisons. In addition, to facilitate interpretation of any impact of PAR1 gene deletion on gene expression in the uninjured spinal cord, and to permit statistical comparisons, expression levels shown for uninjured control PAR1−/− mice are expressed as a percent of uninjured PAR1+/+ controls. Baseline levels of GFAP, neurocan and BIM were higher in PAR1−/− compared to PAR1+/+ mice. (*P < 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 NK).

As expected, in wild type mice GFAP RNA was elevated in response to SCI at both 7 and 30 dpi; with significant increases across all injury levels reaching 2- to 3-fold that seen in the intact spinal cord (P ≤ 0.001 NK, Figure 8A–B). In PAR1−/− mice, elevations in GFAP at 30 dpi were absent at all segmental levels of injury except below the injury epicenter (P = 0.002). At 7 dpi, increases in GFAP in the injury epicenter and above were slightly higher in PAR1−/− compared to PAR1+/+ mice (P < 0.001, NK). Also, GFAP RNA levels were slightly higher in PAR1−/− compared to PAR1+/+ spinal cords at baseline (P = 0.02, NK).

At 7 and 30 dpi, 1.8- and 1.2-fold elevations in neurocan RNA were observed above the SCI epicenter in PAR1+/+ (P = 0.04, NK), but not PAR1−/− mice (P = 0.005, NK, Figure 8 E–F). By contrast, no change or reductions in neurocan RNA were observed in the injury epicenter and below at the same time points in PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/− mice (P < 0.001, NK). Neurocan expression levels in the intact spinal cord were approximately 1.5-fold higher in PAR1−/− compared to PAR1+/+ mice (P < 0.001, NK).

Apoptosis-associated RNA transcription and Protein Expression

Substantial elevations in RNA for the pro-apoptotic signaling protein BIM were observed at 7 and 30 dpi (Figure 8 G–H). The greatest increases in BIM RNA expression after injury occurred in the injury epicenter where levels were 5- to 8-fold that seen in the intact spinal cord at 7 and 30 dpi, respectively (P ≤ 0.001 NK, Figure 7D). By contrast, PAR1−/− mice showed substantially lower levels of BIM induction at acute and chronic time points (P ≤ 0.02, NK). Levels of BIM RNA expression were slightly higher (1.3-fold) in the spinal cord in mice lacking the PAR1 (P ≤ 0.02).

Cytokine RNA transcription

The possible contributions of changes in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines to the improvements in neurobehavioral recovery observed in PAR1−/− mice after SCI was examined using quantitative real time PCR at acute (7 dpi) and more chronic (30 dpi) time points after SCI (Figure 9). Across the cytokines examined, which included 3 different pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-1β and IL-6), and 2 generally anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β and IL-10), the greatest increases in expression generally occurred at the injury epicenter with smaller elevations above and below. In wild type mice, all cytokines were elevated at acute and more chronic time points after injury with TNF and IL-1β being equally elevated at each time point, but elevations in IL-6 and IL-10 predominated acutely, and TGF-β more chronically. Overall, mice lacking PAR1 demonstrated substantially reduced SCI-related cytokine elevations.

Figure 9. Spinal cord injury-induced elevations in pro-inflammatory cytokines were reduced in mice lacking the PAR1 gene.

Histograms show transcriptional changes in RNA encoding pro-inflammatory (TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, A–F), or anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10, G–J), in the spinal cord of PAR1+/+ or PAR1−/− uninjured controls (C), or in the 3 mm of spinal cord surrounding the injury epicenter (E), or that above (A), or below (B), at 7 and 30 dpi. The RNA expression levels shown are expressed as a percent of the uninjured genotype control and these data were used for statistical comparisons. In addition, to facilitate interpretation of any impact of PAR1 gene deletion on cytokine expression in the uninjured spinal cord, and to permit statistical comparisons, expression levels shown for uninjured control PAR1−/− mice are expressed as a percent of uninjured PAR1+/+ controls. No significant differences in cytokine RNA expression were observed in the uninjured spinal cord between PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/− mice. (*P < 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 NK).

Of the cytokines examined, IL-1β expression was most robustly elevated across 7 to 30 dpi (51- to 59-fold, respectively) and these changes were reduced by greater than half in PAR1−/− mice (P < 0.001, NK, Figure 9 C–D). SCI-associated increases in TNF RNA observed in wild type mice were also substantially reduced in PAR1−/− mice lacking PAR1 at 7 dpi (P < 0.001, NK). Interestingly, although TNF RNA levels were also reduced above the injury epicenter and below at 30 dpi in mice lacking PAR1 relative to the increases observed in PAR1+/+ mice, they were slightly elevated (20%) within the injury epicenter (Figure 9 A–B, P < 0.001, NK). SCI-related elevations in IL-6 and TGF-β were also significantly reduced or absent in mice lacking PAR1 (Figure 9 E–H, P ≤ 0.01, NK, Figure 9D). In wild type mice, IL-6 RNA exhibited the greatest increases at 7 dpi when levels in the injury epicenter were increased by 25-fold compared to the more moderate 4- to 2-fold increases seen at the same level 30 dpi. In each case, elevations were reduced to less than 2-fold in mice lacking PAR1. Increases in IL-10 RNA expression were also observed after SCI reaching 30-fold at 7 dpi and 6.2-fold at 30 dpi in the injury epicenter (Figure 9 I–J). Increases in IL-10 were not observed after SCI in PAR1−/− mice at 7 dpi. At 30 dpi, the increases in IL-10 observed in wild type mice were more than 2-fold lower above and below the injury epicenter in mice lacking PAR1 (P ≤ 0.01, NK), although were slightly elevated (18%) at the site of injury (P<0.001, NK).

IL-6 promotes expression of PAR1, its agonists and markers of astrogliosis in primary astrocytes in vitro

Thrombin and neurosin were each a significant driver of IL-6 secretion in primary astrocytes with 4 to 6-fold increases observed over vehicle alone (P < 0.001, NK). Thrombin and neurosin driven increases in IL-6 were significantly reduced in astrocytes derived from PAR1 knockout mice (P < 0.001, NK, Figure 10 C). Each agonist also promoted small increases in secretion of TNF by primary astrocytes (approximately 10% increase over control, P < 0.001, NK), while any changes in IL-1β secretion were not statistically significant. Thrombin induced elevations in TNF were blocked in astrocytes lacking PAR1 (P < 0.001, NK). Interestingly, astrocyte secretion of TNF and IL-1β were each higher at baseline in primary astrocyte cultures lacking PAR1 (P < 0.04, NK, Figure 10 A and B).

Figure 10. IL-6 links PAR signaling to increases in markers of astrogliosis.

(A–H) Thrombin and neurosin (150 ng/ml) promoted significant increases in the secretion of IL-6 (C) in PAR1+/+ astrocytes and these effects were attenuated in astrocytes lacking PAR1. These PAR agonists also promoted small increases in secretion of TNF (A) while changes in IL-1β (B) were not statistically significant. Recombinant IL-6 (20 ng/ml) was a powerful driver of expression of PAR1 (D), thrombin (E) and neurosin (F) in primary astrocytes. Also, IL-6, but not thrombin or neurosin (150 ng/ml), elicited significant increases in expression of the key hallmarks of astrogliosis GFAP (G) and VIM (H, P < 0.001). (*P < 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 NK).

Given the reductions in markers of astrogliosis and in pro-inflammatory cytokines observed in the spinal cord of PAR1−/− mice after SCI (Figures 4, 5, 8 and 9), we sought to investigate possible regulatory relationships. We focused efforts here on thrombin, neurosin and IL-6, since these agonists were found to robustly drive IL-6 secretion in primary astrocyte cultures in a PAR1 dependent manner (Figure 10). First we demonstrated that treatment of astrocytes with recombinant IL-6 for 24 h was a potent activator of astrocyte PAR1 (2-fold, P < 0.001), thrombin (3-fold, P = 0.004) and neurosin (2-fold, P = 0.004, NK) expression (Figure 10 D–F). As reported in our prior studies (Radulovic et al., 2015), recombinant IL-6 also promoted increases in the expression of GFAP and vimentin (2–3-fold, P < 0.001, Figure 10 G and H). Although neither thrombin nor neurosin alone consistently altered the expression of astrocyte intermediate filament proteins, each was a significant driver of IL-6 secretion (4 to 6-fold, P < 0.001, NK, Figure 10 C).

Discussion

The findings presented demonstrate that the thrombin receptor serves as a crucial regulator of the cascade of inflammation and astrogliosis occurring after traumatic SCI and that it can be targeted genetically to improve neurobehavioral outcomes. In the absence of PAR1 we observed substantial reductions in cellular and molecular signatures of inflammation and astrogliosis after SCI and improved preservation of corticospinal axons and recovery of locomotor activity. Complementary studies in primary astrocytes support a model in which PAR1 is an integrator of the actions of multiple serine proteases altered in the SCI microenvironment, including thrombin and neurosin. Activation of PAR1 increased the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL- 6 and the activity of its signaling partner STAT3. In turn, IL-6 drove increases in PAR1 and its agonists, thereby establishing a positive feedback mechanism that may promote IL-6-STAT3 signaling to levels sufficient to elicit fulminant astrogliosis, including increases in the astroglial intermediate filament proteins GFAP and vimentin. Thus PAR1 is identified as a tangible target for therapies aimed at modulating inflammation and astrogliosis to enhance recovery of locomotor function after SCI.

PAR1 is an essential mediator of neural injury after SCI

Using PAR1 knockout mice we present several lines of evidence that PAR1 is an integral mediator of inflammation, astrogliosis and functional decline after SCI and that this densely expressed receptor signaling system can be targeted to improve recovery of locomotor function. For example, SCI-associated increases in signatures of astrogliosis, including the intermediate filament proteins GFAP and vimentin (Middeldorp and Hol, 2011) and the inhibitory proteoglycan neurocan, were each substantially attenuated in mice-lacking PAR1. GFAP and vimentin are required for astrocyte scar formation (Pekny and Pekna, 2004) and neurocan can block neurite outgrowth (Laabs et al., 2007). In addition, the injured spinal cord of mice lacking PAR1 also showed reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and IL-6, together with decreases in the abundance of monocytes/microglia. Data presented suggest that the attenuated astroglial and inflammatory responses occurring as a consequence of targeting PAR1 globally were also associated with reductions in apoptosis, increased tissue sparing and preservation of NeuN-positive ventral horn neurons and PKCγ- positive corticospinal axons (Lieu et al., 2013). Significantly, all of the improvements in spinal cord pathophysiology observed in PAR1−/− mice were associated with better locomotor outcomes. The current findings based on direct gene targeting of PAR1 support conclusions of prior studies demonstrating that targeting the activity of thrombin using recombinant thrombomodulin (Taoka et al., 2000; Festoff et al., 2004) likewise reduces inflammation and apoptosis after experimental SCI leading to improvements in functional outcomes. These findings also harmonize with reported beneficial effects of targeting PAR1 or thrombin in other neurological conditions, including experimental stroke. For example, mice lacking PAR1 (Junge et al., 2003; Olson et al., 2004), or with PAR1 knockdown (Zhang et al., 2012; Rajput et al., 2014) show increased resistance to ischemic injury. Finally, the thrombin inhibitor argatroban alleviates neurovascular injury and prevents cognitive dysfunction in acute experimental focal ischemia (Chen et al., 2012; Lyden et al., 2014).

PAR1 modulates inflammation and astrogliosis

The coordinate attenuation of both astrogliosis and inflammation by global targeting of PAR1 is significant since compelling evidence indicates that a productive glial scar is an essential element of successful CNS wound healing (Sofroniew and Vinters, 2010). Although the astroglial scar is often portrayed in terms of its negative influence, particularly as a barrier to nerve regeneration (Menet et al., 2003; Silver and Miller, 2004), a gradated astroglial response contributes to wound closure, neuron protection, repair of the blood brain barrier, and restriction of cytotoxic inflammation (Bush et al., 1999; Liberto et al., 2004; Wanner et al., 2013). The beneficial effects of astrogliosis appear of central importance being documented in SCI (Faulkner et al., 2004; Herrmann et al., 2008), and other disorders including stroke (Li et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2014), EAE (Liedtke et al., 1998; Voskuhl et al., 2009; Toft-Hansen et al., 2011), Alzheimers (Kraft et al., 2013) and Parkinsons (Shao et al., 2013). For example, in the absence of GFAP or vimentin there is an exacerbation of inflammation and pathology in autoimmune (Liedtke et al., 1998), ischemic (Li et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2014), and neurodegenerative conditions (Macauley et al., 2011; Kraft et al., 2013). Similarly, disruption of glial scar formation by deletion of astrocyte STAT3 exacerbates SCI-associated inflammation, results in increased lesion size, and decreased recovery of motor function (Herrmann et al., 2008; Wanner et al., 2013). The current findings demonstrate that interruption of PAR1 signaling effectively moderates astrogliosis and inflammation at acute and chronic time points to a level compatible with enhanced locomotor recovery.

The elevations we document in PAR1 and its agonists in the aftermath of SCI position this receptor to be an essential player in communicating changes in the extracellular proteolytic microenvironment into key cellular responses at acute and chronic time points. Thrombin is a high affinity agonist for PAR1 and can rapidly extravasate across a damaged blood brain barrier. In addition, quantitative PCR demonstrated substantial elevations in thrombin and PAR1 within the SCI epicenter. Complementary immunohistochemical approaches demonstrated thrombin expression associated with astrocytes in the perilesional area, while PAR1 was localized to astrocytes and monocytes/microglia. Prior studies support the idea that thrombin can be produced by CNS cells endogenously (Dihanich et al., 1991) with elevations after injury, including SCI (Citron et al., 2000; Yoon et al., 2013), ischemia (Riek-Burchardt et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2012; Rajput et al., 2014), and in Alzheimers (Arai et al., 2006). Furthermore, the expression of another PAR1 agonist, neurosin (Vandell et al., 2008), was also significantly elevated after SCI with expression not only by astrocytes, but also activated monocytes/microglia as we have previously reported in other models of experimental SCI (Scarisbrick et al., 1997; Scarisbrick et al., 2002; Blaber et al., 2004; Scarisbrick et al., 2006; Scarisbrick et al., 2012b; Yoon et al., 2013; Panos et al., 2014) and in cases of human SCI as long as 5 years after the initial insult (Radulovic et al., 2013). While elevations in thrombin, neurosin and PAR1 occurred across the injury continuum, thrombin levels were maximal acutely pointing to key roles in the early injury response. Results further suggest that PAR1 activation regulates the expression of its own agonists after SCI, since mice lacking PAR1 showed very limited increases in thrombin and neurosin at 7 dpi and any changes were completely absent 30 dpi. As this line of research moves forward it will be important to consider the roles of other SCI relevant serine proteases, including additional kallikreins (Scarisbrick et al., 2006; Radulovic et al., 2013), to determine whether their actions likewise occur by activation of PAR(s), and whether they can be dynamically modulated to foster neurobehavioral recovery as the spinal cord lesion evolves from an acute to a chronic injury.

Results suggest the need for additional efforts to determine the range of injury and repair parameters influenced by protease-signaling at PAR1. Since PAR1 is expressed by neurons, astrocytes and monocytes/microglia, a more complete understanding of the mechanism(s) by which the absence of PAR1 improves reduces neural injury; astrogliosis and inflammation will await examination of responses in mice where PAR1 is targeted in a cell specific manner. Given the tight regulatory relationships between astrocytes and inflammation (Bush et al., 1999; Faulkner et al., 2004; Voskuhl et al., 2009; Wanner et al., 2013), it is possible that targeting PAR1 on both astrocytes and microglia was necessary for the moderations in neural injury and the improvements in neurobehavioral recovery observed. Improvements in the preservation of corticospinal tract axons and spinal cord neurons observed in mice lacking PAR1 may also have contributed to the improvements in locomotor outcomes observed. Neurons express high levels of PAR1 (Niclou et al., 1994; Junge et al., 2003; Olson et al., 2004; Vandell et al., 2008) and over activation of PAR1 can result in neurotoxicity (Smirnova et al., 1998; Turgeon et al., 1998; Festoff et al., 2000a; Yoon et al., 2013). In addition, we recently demonstrated that there is more myelin basic protein and thickened myelin sheaths in the spinal cord of PAR1−/− adult mice (Yoon et al., 2015) and therefore differences in myelin preservation or repair after SCI in mice lacking PAR1 will be an important avenue for future investigation. Taken together the current data suggest that PAR1 represents a key biological signaling node that can be targeted genetically to modulate the SCI microenvironment limiting but not blocking inflammatory-astrogliosis in a manner that fosters wound healing, neural preservation and functional recovery.

PAR1 agonists regulate IL-6-mediated STAT3 signaling and astrogliosis

A systematic investigation of the molecular profile of the site of SCI in PAR1+/+ and PAR1−/− mice, combined with in vitro approaches, points to a mechanistic link between PAR1, IL-6 and STAT3-signaling in SCI-driven astrogliosis. As discussed, mice lacking PAR1 showed tandem reductions in signatures of astrogliosis, including expression of the intermediate filament proteins GFAP and vimentin, as well as IL-6 and its signaling partner STAT3. Therefore, we critically evaluated the ability of the PAR1 agonists thrombin and neurosin to alter these parameters in primary astrocyte cultures. While neither PAR1 agonist was a consistent driver of astroglial intermediate filaments in astrocyte cultures, each reliably increased IL-6 and STAT3 signaling. Thrombin and neurosin elicited increases in astrocyte IL-6 and STAT3 were dependent in part on PAR1 since responses were reduced or absent in PAR1−/− astrocytes. IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine up regulated in reactive astrocytes (Hariri et al., 1994). Blockade of IL-6 reduces astrogliosis, inflammation and connective tissue scarring and improves behavioral outcomes after experimental SCI (Okada et al., 2004). Accordingly, recombinant IL-6 promoted expression of both GFAP and vimentin in the astrocyte cultures examined here. STAT3 is a transcriptional activator regulated by a variety of cytokines and growth factors, and is a well-established mediator of IL-6-driven astrogliosis (Okada et al., 2006; Yamauchi et al., 2006; Herrmann et al., 2008; Wanner et al., 2013) and CNS microglial inflammatory responses (Kim et al., 2002). Taken together these findings suggest that at least some of the reductions in IL-6 and STAT3 signaling observed in PAR1−/− mice after SCI are likely to occur at the level of the astrocyte and relate to a reduction in the capacity of SCI-related serine proteases such as thrombin and neurosin, to exert their hormone like actions.

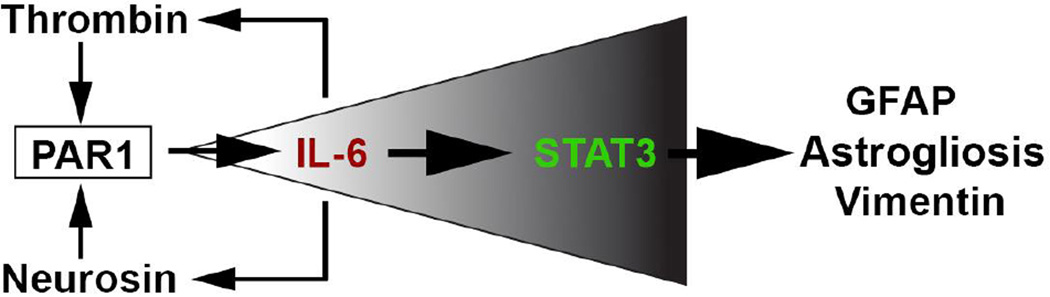

While our findings point to an essential role for PAR1 in STAT3 activation there is little evidence supporting a direct activation pathway (Chung et al., 1997; Sengupta et al., 1998). In this case, it is possible that PAR1-mediated increases IL-6 expression and secretion link PAR1 activation indirectly to the STAT3 signaling observed. In this suggested model (Figure 10), activation of PAR1 elicits IL-6 secretion that in turn activates STAT3 by conventional IL-6 receptor signaling. Our data further suggest that the PAR1-IL-6 signaling system is reciprocal since recombinant IL-6 also promoted increases in expression of PAR1 and its agonists, thrombin and neurosin. We propose that by way of this feedforward and feedback signaling circuit centered in part on PAR1, that sufficient levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and STAT3 signaling are ultimately achieved to drive the production of cytoskeletal proteins associated with fulminant astrogliosis, such as GFAP.

The ability of both thrombin and neurosin to activate other PARs, taken with the fact that astrocytes express each of the 4 identified PARs (Wang et al., 2002a; Vandell et al., 2008), likely accounts for the ability of these proteases to continue to elicit increases in IL-6 even in the absence of PAR1. While thrombin has highest affinity for PAR1, it also activates PAR3 and PAR4 and activity at these receptors should be investigated as an additional route by which thrombin may regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6. PAR4 is known to participate in pro-inflammatory microglial responses (Suo et al., 2003a). In a recent study, we demonstrated that neurosin also activates PAR2 to promote astrocyte IL-6-STAT3 signaling (Vandell et al., 2008; Radulovic et al., 2015). Moreover, genetic targeting of PAR2 alone similarly attenuated inflammation and astrogliosis resulting in improved neurobehavioral outcomes in experimental SCI (Radulovic et al., 2015). While co-ordinate targeting of multiple PARs should be considered, it is unclear whether this would necessarily be beneficial since at least a limited astroglial response appears essential for constraining inflammation and wound healing in the aftermath of SCI (Herrmann et al., 2008; Wanner et al., 2013).

Conclusion

PAR1 sits at the interface of the proteolytic microenvironment and cellular responses contributing to astrogliosis, pro-inflammatory events and neurodegeneration accompanying traumatic SCI. Given the large number of proteases deregulated after CNS trauma, targeting select PARs as final common mediators of their cellular effects becomes an attractive target for therapy. This conclusion has strong clinical implications, since small molecule inhibitors of PAR1 have recently entered the market for the treatment of thrombolytic disease (French et al., 2015). The current results regarding the benefits of targeting PAR1 in the case of SCI provide a clear rationale to continue efforts to determine the efficacy of targeting this receptor to improve outcomes after neurological injury.

Figure 11. Hypothetical model by which activation of PAR1 may contribute to astrogliosis.

Thrombin and neurosin are increased in the spinal cord in the context of traumatic injury and activate astrocyte PAR1 to promote expression and secretion of IL- 6. IL-6 in turn activates STAT3 signaling and feeds back to increase the expression of PAR1 activators (thrombin and neurosin), driving the canonical IL-6-STAT3 signaling cascade and fulminant astrogliosis forward. While this simplified model suggests a mechanism for PAR1 signaling in driving astrogliosis after SCI it does not exclude PAR1 signaling in neurons, myelinating cells and microglia as additional significant contributors to SCI pathogenesis.

Highlights.

PAR1 is an essential regulator of the pro-inflammatory microenvironment after traumatic SCI.

PAR1 drives interleukin 6 secretion by astrocytes which feeds back to increase expression of both PAR1 and its agonists.

PAR1 is a novel activator of STAT3 signaling after SCI.

Targeting PAR1 reduces inflammation, astrogliosis and neurodegeneration after SCI.

PAR1 represents a key target to improve locomotor recovery after SCI.

Acknowledgments

Studies were supported by the National Institutes of Health 5R01NS052741, Pilot Project PP2009 and a Collaborative MS Research Center Award CA1060A11 from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and an Accelerated Regenerative Medicine Award from the Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Studies regarding the impact of PAR1 gene deletion on recovery of function after SCI were performed in conjunction with a study regarding the impact of genetic targeting of PAR2 the results of which were recently published (Radulovic et al., 2015 Neurobiology of Disease 83: 75–89). The PCR and Western blots for PAR+/+, PAR1−/− and PAR2−/− experimental samples were performed in parallel using the same PAR+/+ mice as controls. Therefore the wild type control PAR+/+ (data) that was used in the Figures regarding PCR or Western blots is the same as that shown Radulovic et al., 2015 in our comparisons of responses between WT and PAR2−/− mice. Specifically, data for Neurosin RNA in PAR+/+ Figure 1E and F; Western blot data for PAR1+/+ at 3 and 30 dpi (Figure 5); PCR expression data for PAR+/+ at 30 dpi in Figure 8 and 9; and the RNA data for control, neurosin and IL-6 treated astrocytes in Figure 10 F, G and H.

References

- Acharjee S, Zhu Y, Maingat F, Pardo C, Ballanyi K, Hollenberg MD, Power C. Proteinase-activated receptor-1 mediates dorsal root ganglion neuronal degeneration in HIV/AIDS. Brain. 2012;134:3209–3221. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MN, Ramachandran R, Yau MK, Suen JY, Fairlie DP, Hollenberg MD, Hooper JD. Structure, function and pathophysiology of protease activated receptors. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2011;130:248–282. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T, Miklossy J, Klegeris A, Guo JP, McGeer PL. Thrombin and prothrombin are expressed by neurons and glial cells and accumulate in neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer disease brain. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2006;65:19–25. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000196133.74087.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso DM, Fisher LC, Anderson AJ, Jakeman LB, McTigue DM, Popovich PG. Basso mouse scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:635–659. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber SI, Ciric B, Christophi GP, Bernett MJ, Blaber M, Rodriguez M, Scarisbrick IA. Targeting kallikrein 6-proteolysis attenuates CNS inflammatory disease. FASEB J. 2004;19:920–922. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1212fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boven LA, Vergnolle N, Henry SD, Silva C, Imai Y, Holden J, Warren K, Hollenberg MD, Power C. Up-regulation of proteinase-activated receptor 1 expression in astrocytes during HIV encephalitis. J Immunol. 2003;170:2638–2646. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury EJ, Moon LD, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, Fawcett JW, McMahon SB. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002;416:636–640. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda JE, Radulovic M, Yoon H, Scarisbrick IA. Critical role for PAR1 in kallikrein 6-mediated oligodendrogliopathy. Glia. 2013;61:1456–1470. doi: 10.1002/glia.22534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush TG, Puvanachandra N, Horner CH, Polito A, Ostenfeld T, Svendsen CN, Mucke L, Johnson MH, Sofroniew MW. Leukocyte infiltration, neuronal degeneration, and neurite outgrowth after ablation of scar-forming, reactive astrocytes in adult transgenic mice. Neuron. 1999;23:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Cheng Q, Yang K, Lyden PD. Thrombin mediates severe neurovascular injury during ischemia. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2010;41:2348–2352. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Friedman B, Whitney MA, Winkle JA, Lei IF, Olson ES, Cheng Q, Pereira B, Zhao L, Tsien RY, Lyden PD. Thrombin activity associated with neuronal damage during acute focal ischemia. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:7622–7631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0369-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Uchida E, Grammer TC, Blenis J. STAT3 serine phosphorylation by ERK-dependent and -independent pathways negatively modulates its tyrosine phosphorylation. Molecular and cellular biology. 1997;17:6508–6516. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron BA, Smirnova IV, Arnold PM, Festoff BW. Upregulation of neurotoxic serine proteases, prothrombin, and protease- activated receptor 1 early after spinal cord injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 2000;17:1191–1203. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham DD, Pulliam L, Vaughan PJ. Protease nexin-1 and thrombin: injury-related processes in the brain. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:168–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibaj P, Zschuntzsch J, Steffens H, Scheffel J, Goricke B, Weishaupt JH, Le Meur K, Kirchhoff F, Hanisch UK, Schomburg ED, Neusch C. Influence of methylene blue on microglia-induced inflammation and motor neuron degeneration in the SOD1(G93A) model for ALS. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dihanich M, Kaser M, Reinhard E, Cunningham D, Monard D. Prothrombin mRNA is expressed by cells of the nervous system. Neuron. 1991;6:575–581. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90060-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez E, Mauborgne A, Mallet J, Desclaux M, Pohl M. SOCS3-mediated blockade of JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway reveals its major contribution to spinal cord neuroinflammation and mechanical allodynia after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5754–5766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5007-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly DJ, Longbrake EE, Shawler TM, Kigerl KA, Lai W, Tovar CA, Ransohoff RM, Popovich PG. Deficient CX3CR1 signaling promotes recovery after mouse spinal cord injury by limiting the recruitment and activation of Ly6Clo/iNOS+ macrophages. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9910–9922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2114-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker KD, Paulsen AP, Giannini C, Decker PA, Blaber IS, Blaber M, Uhm J, O'Neill BP, Jenkins R, Scarisbrick IA. Clinical Significance and Novel Mechanism of Action of Kallikrein 6 in Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(3):305–318. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner JR, Herrmann JE, Woo MJ, Tansey KE, Doan NB, Sofroniew MV. Reactive astrocytes protect tissue and preserve function after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2143–2155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festoff BW, D'Andrea MR, Citron BA, Salcedo RM, Smirnova IV, Andrade-Gordon P. Motor neuron cell death in wobbler mutant mice follows overexpression of the G-protein-coupled, protease-activated receptor for thrombin. Molecular medicine. 2000a;6:410–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festoff BW, D'Andrea MR, Citron BA, Salcedo RM, Smirnova IV, Andrade-Gordon P. Motor neuron cell death in wobbler mutant mice follows overexpression of the G-protein-coupled, protease-activated receptor for thrombin. Mol Med. 2000b;6:410–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festoff BW, Ameenuddin S, Santacruz K, Morser J, Suo Z, Arnold PM, Stricker KE, Citron BA. Neuroprotective effects of recombinant thrombomodulin in controlled contusion spinal cord injury implicates thrombin signaling. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:907–922. doi: 10.1089/0897715041526168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SL, Arthur JF, Tran HA, Hamilton JR. Approval of the first protease-activated receptor antagonist: Rationale, development, significance, and considerations of a novel anti-platelet agent. Blood Rev. 2015;29:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich MB, Traynelis SF. Serine proteases and brain damage - is there a link? Trends in Neuroscience. 2000;23:399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01617-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill CE, Goldshmidt A, Nicole O, McKeon RJ, Brat DJ, Traynelis SF. Special lecture: glial reactivity after damage: implications for scar formation and neuronal recovery. Clin Neurosurg. 2005;52:29–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill CE, Mannaioni G, Lyuboslavsky P, Sastre AA, Traynelis SF. Protease-activated receptor 1-dependent neuronal damage involves NMDA receptor function. Exp Neurol. 2009;217:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han KS, Mannaioni G, Hamill CE, Lee J, Junge CE, Lee CJ, Traynelis SF. Activation of protease activated receptor 1 increases the excitability of the dentate granule neurons of hippocampus. Mol Brain. 2011;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri RJ, Chang VA, Barie PS, Wang RS, Sharif SF, Ghajar JB. Traumatic injury induces interleukin-6 production by human astrocytes. Brain research. 1994;636:139–142. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann JE, Imura T, Song B, Qi J, Ao Y, Nguyen TK, Korsak RA, Takeda K, Akira S, Sofroniew MV. STAT3 is a critical regulator of astrogliosis and scar formation after spinal cord injury. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:7231–7243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itsekson-Hayosh Z, Shavit-Stein E, Katzav A, Rubovitch V, Maggio N, Chapman J, Harnof S, Pick CG. Minimal traumatic brain injury in mice - PAR-1 and thrombin related changes. Journal of neurotrauma. 2015 doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi M, Fehlings M. Development and characterization of a novel, graded model of clip compressive spinal cord injury in the mouse: Part 2. Quantitative neuroanatomical assessment and analysis of the relationships between axonal tracts, residual tissue, and locomotor recovery. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:191–203. doi: 10.1089/08977150252806956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge CE, Sugawara T, Mannaioni G, Alagarsamy S, Conn PJ, Brat DJ, Chan PH, Traynelis SF. The contribution of protease-activated receptor 1 to neuronal damage caused by transient focal cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13019–13024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235594100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge CE, Lee CJ, Hubbard KB, Ahoabin A, Olson JJ, Hepler JR, Brat DJ, Traynelis SF. Protease-activated receptor-1 in human brain: localization and functional expression in astrocytes. Exp Neurol. 2004;1888:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendziorski C, Irizarry RA, Chen KS, Haag JD, Gould MN. On the utility of pooling biological samples in microarray experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4252–4257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500607102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HN, Kim YR, Ahn SM, Lee SK, Shin HK, Choi BT. Protease activated receptor-1 antagonist ameliorates the clinical symptoms of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis via inhibiting breakdown of blood-brain barrier. Journal of neurochemistry. 2015;135:577–588. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim OS, Park EJ, Joe EH, Jou I. JAK-STAT signaling mediates gangliosides-induced inflammatory responses in brain microglial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40594–40601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft AW, Hu X, Yoon H, Yan P, Xiao Q, Wang Y, Gil SC, Brown J, Wilhelmsson U, Restivo JL, Cirrito JR, Holtzman DM, Kim J, Pekny M, Lee JM. Attenuating astrocyte activation accelerates plaque pathogenesis in APP/PS1 mice. Faseb J. 2013;27:187–198. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-208660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laabs TL, Wang H, Katagiri Y, McCann T, Fawcett JW, Geller HM. Inhibiting glycosaminoglycan chain polymerization decreases the inhibitory activity of astrocyte-derived chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14494–14501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2807-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]