Abstract

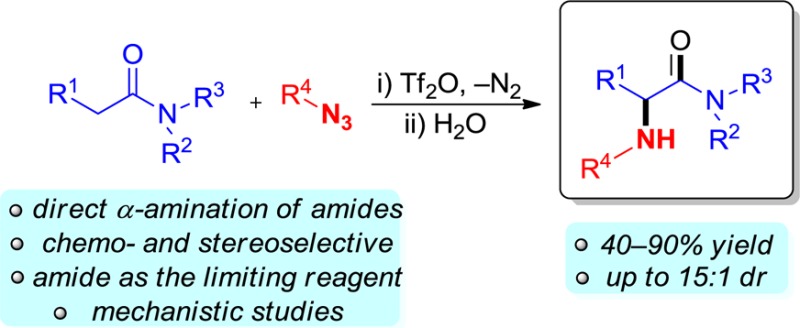

The synthesis of α-amino carbonyl/carboxyl compounds is a contemporary challenge in organic synthesis. Herein, we present a stereoselective α-amination of amides employing simple azides that proceeds under mild conditions with release of nitrogen gas. The amide is used as the limiting reagent, and through simple variation of the azide pattern, various differently substituted aminated products can be obtained. The reaction is fully chemoselective for amides even in the presence of esters or ketones and lends itself to preparation of optically enriched products.

As one of nature’s key building blocks, α-amino acids form a recurrent motif in bioactive natural products. In particular, α-amino acids and peptides are becoming an increasing subset of commercialized drugs.1 In this context, non-natural α-amino acids are especially interesting as their incorporation in peptides can modify properties to a large extent,2 and thus the synthesis of α-amino carbonyl/carboxyl compounds has attracted considerable attention from synthetic chemists.3

Direct α-amination is perhaps the most logical and flexible strategy to access α-amino carbonyl derivatives. Classical approaches are summarized in Scheme 1, and electrophilic amination features prominently among them.4,5 Due to the need for an electrophilic source of nitrogen, most of these methods actually lead to α-hydrazinyl or α-oxy-amino products that need to be further modified to get to the biologically relevant α-amino compounds. For instance, Ohshima et al. recently presented an elegant copper-catalyzed amination of carboxylic acid derivatives with a preformed iminoiodinane which requires drybox manipulation and delivers tosyl-protected amines that are not simple to deprotect.6 Another approach allows to simply couple an amine with a carbonyl under oxidative conditions, though only disubstituted amines can be employed (Scheme 1b).7

Scheme 1. Strategies for the α-Amination of Carbonyl Compounds.

Our group has recently exploited metal-free amide activation as a powerful chemoselective strategy for the functionalization of amides.8,9 Herein we report a chemo- and stereoselective α-amination of amides employing simple azides, known as good nucleophiles,10 that proceeds under mild conditions (Scheme 1c) with release of nitrogen gas.

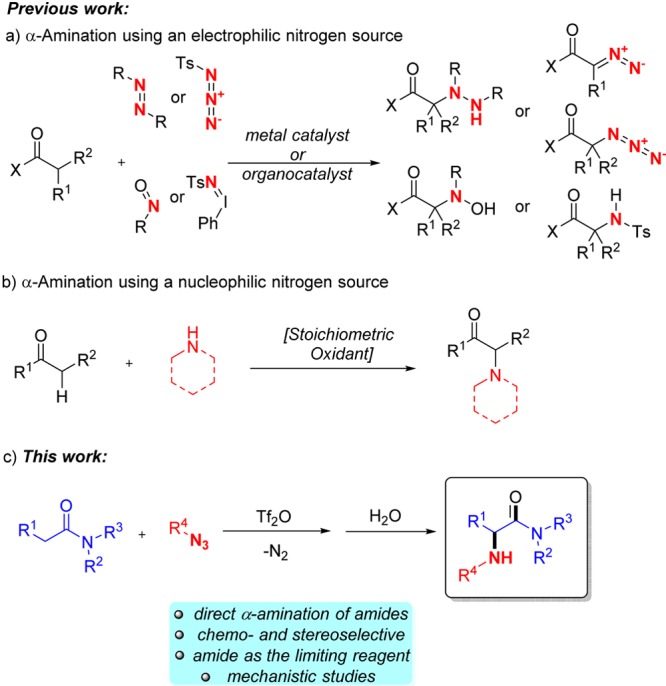

At the outset, we decided to study the reaction of the amide 1a with the azide 2a using amide activation conditions previously developed by our group.8b Pleasingly, these conditions led to the smooth formation of 3aa in 52% isolated yield. Importantly, single-crystal X-ray analysis confirmed the anticipated connectivity of 3aa (Scheme 2).11

Scheme 2. Preliminary Study.

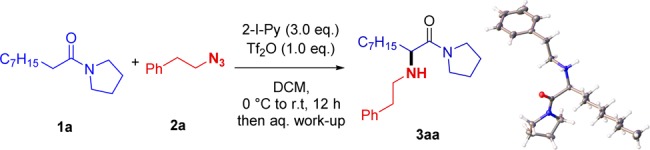

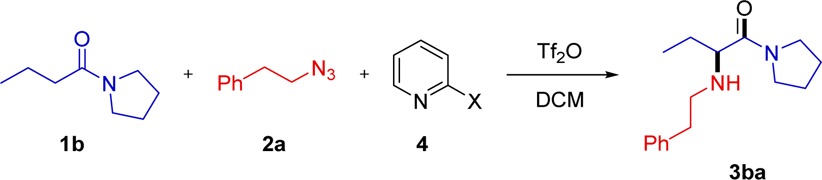

With this encouraging preliminary result, we screened different reaction conditions (employing substrate 1b), and key observations are compiled in Table 1. The use of 2-fluoropyridine was found to give a slightly increased yield (Table 1, entry 2), while simple pyridine did not afford the desired product (entry 3). Significantly, the quenching method had a noteworthy impact on the process. Quenching the reaction mixture with a saturated solution of NaHCO3 significantly improved the yield (entries 5–7), while reducing the reaction time to 30 min finally gave the best results (entry 8).11

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction Conditionsa,b.

| entry | equiv of 2a | equiv of 4 | equiv of Tf2O | X | quench | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | I | NaOH-NaCl | 56 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | F | 61 | |

| 3 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | H | 0 | |

| 4 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | OMe | 30 | |

| 5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | F | NaHCO3 | 74 |

| 6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | F | 80 | |

| 7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | F | 79 | |

| 8c | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | F | NaHCO3 (1 h) | 85 |

Reaction conditions: A mixture of amide 1b (0.3 mmol, 1 equiv) and base in DCM (1 mL) was treated with Tf2O at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 15 min, then the azide 2a was added, and the reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature for 1 h prior to quenching.

Yield determined by NMR analysis with mesitylene as the internal standard.

Reaction time of 30 min prior to quenching.

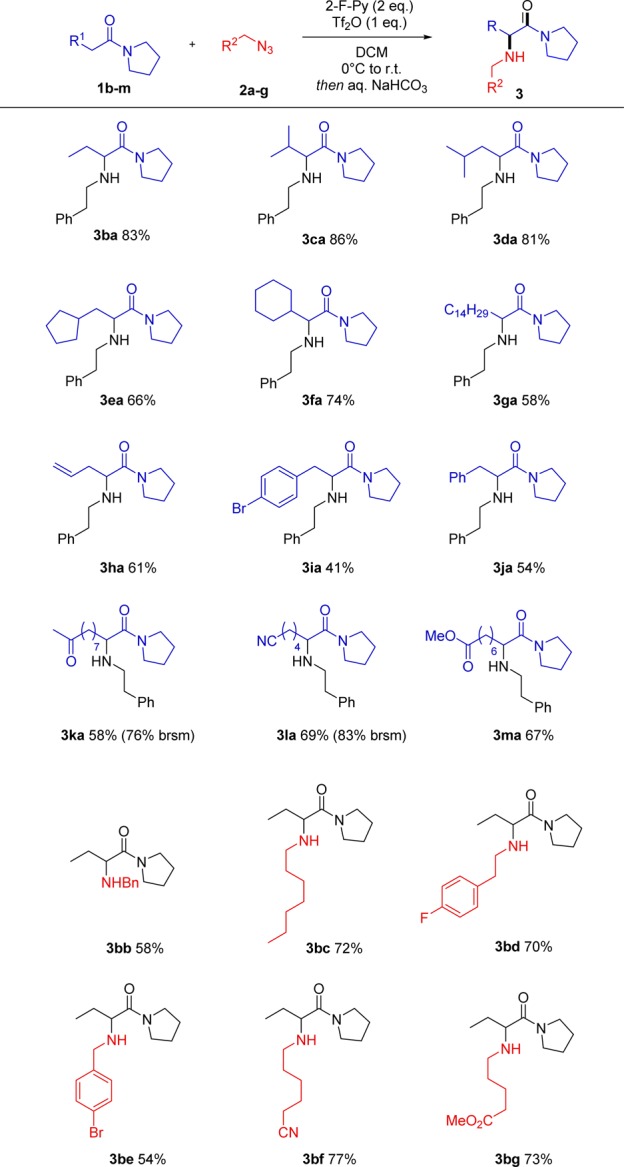

With these optimized conditions, we decided to evaluate the scope of the reaction with particular emphasis on functional group tolerance. As shown in Scheme 3, various aliphatic substituents were allowed on the amide component, giving moderate to excellent yields of products (Scheme 3, 3ba–3ga). Unsaturations were also tolerated (3ha) as well as aromatic rings on both partners (3ia–3ja). Remarkably, this metal-free reaction was chemoselective for the amide moiety in the presence of an ester group (3ma), an alkyl nitrile (3la), or even a naked methyl ketone (3ka). Similarly, the presence of halides (3bd–3be), esters (3bg), or cyano groups (3bf) on the azide did not significantly affect the yield. Of added interest is also the formation of benzyl-protected amines using benzyl azide (3bb).

Scheme 3. Substrate Scope of the Amination of Amides with Azides.

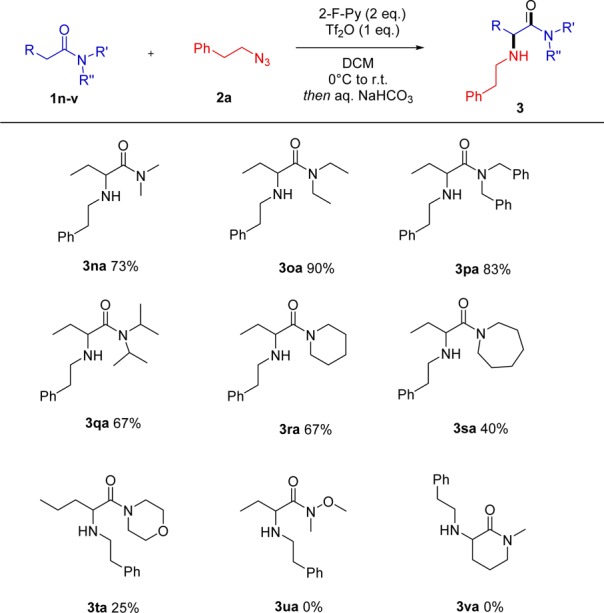

We then turned our attention to the scope on differently substituted, N-functionalized amides (Scheme 4). To our delight, both cyclic and acyclic amides gave good results, even when the nitrogen center carried hindered isopropyl- or benzyl moieties (3pa–3qa). This showcases the general applicability of this chemistry to various amide backbones, a synthetically useful trait. Interestingly, Weinreb amides proved to be unreactive under the reaction conditions, as well as lactams, offering opportunities for chemoselectivity even among different amide moieties.

Scheme 4. Direct Amination of Different Amide Backbones.

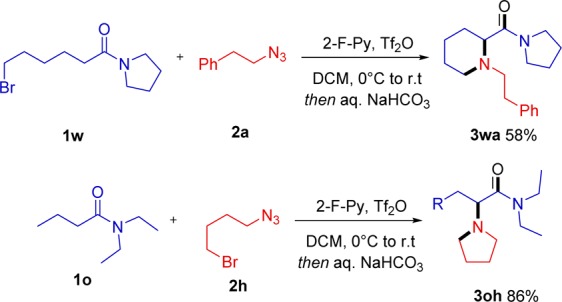

Importantly, the method can be tuned to generate tertiary amine products in at least two different manners (Scheme 5). For instance, use of an amide substrate 1w carrying a remote bromine substituent triggers a domino amination/cyclization to form a six-membered ring (Scheme 5). Alternatively, the use of a halogenated azide 2h delivers α-pyrrolidine 3oh in very good yield. The flexibility of these two approaches is yet another feature of this simple amination procedure. Indeed, few amination procedures available in the literature lend themselves to preparation of both classes of compounds depicted in Scheme 5.

Scheme 5. Tertiary Amine Formation.

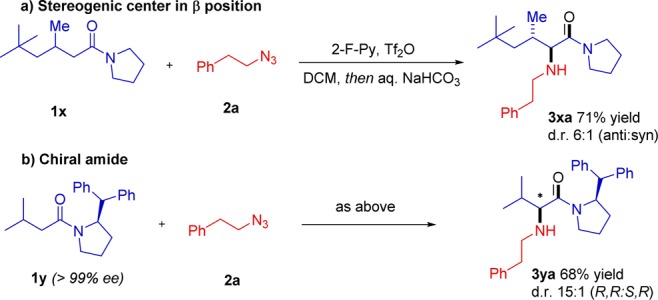

At this stage, we wished to interrogate the system with regard to stereoselectivity. Submitting racemic compound 1x, bearing a stereocenter β- to the amide carbonyl, to amination with azide 2a smoothly led to the desired product 3xa in 71% yield with 6:1 diastereoselectivity (anti:syn) (Scheme 6a).

Scheme 6. Studies on Diastereoselectivity and Asymmetric Induction.

On the other hand (Scheme 6b), the use of a chiral amide 1y led to an excellent 15:1 diastereoselectivity upon amination with azide 2a. The experiments in Scheme 6 delineate a highly stereoselective amination procedure.

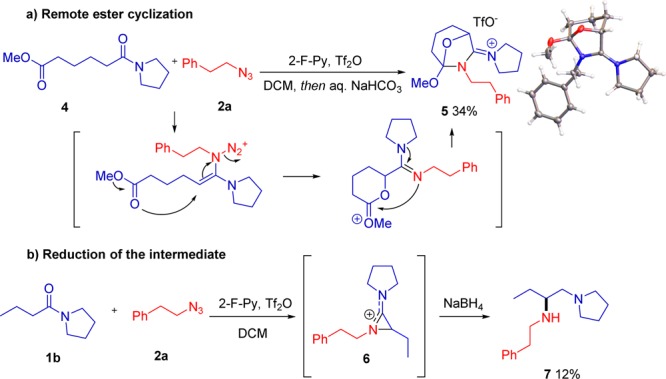

During our study of the functional group tolerance, one specific experiment led to an unexpected result with mechanistic implications. In the event, subjecting mixed adipic acid ester/amide 4 to amination with azide 2a led to the complex bicyclic product 5 (Scheme 7a), as elucidated by X-ray analysis.11 Our interest piqued, we decided to quench the reaction with NaBH4 instead of the usual aqueous workup (Scheme 7b). This afforded the diamine 7, suggesting that the intermediate prior to quench might be an azirinium species 6.12

Scheme 7. Mechanistically Relevant Observations.

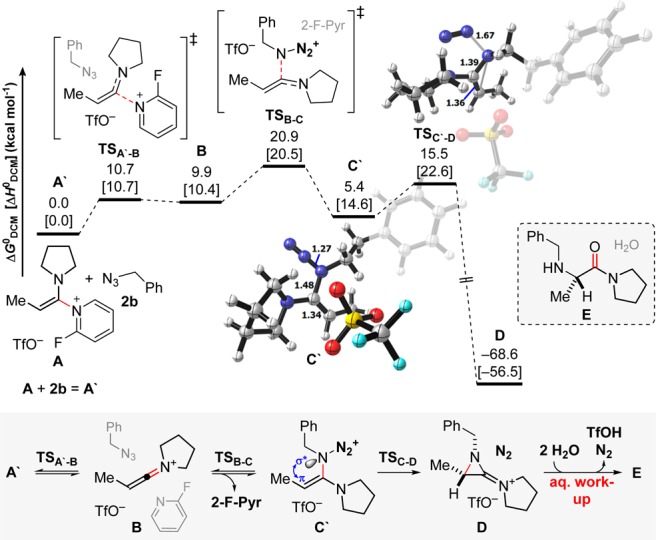

Intrigued by these observations, we undertook density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate the mechanism (Scheme 8).13 In agreement with our prior studies,8b we commenced our DFT analysis with N,N-ketene aminal A (Scheme 8), formation of which experimentally precedes addition of azide 2b.

Scheme 8. Computed Pathway for the Formation of Final Hydrolysis Precursor, Amidinium D (ref (13)).

Free energies ΔGDCMo and enthalpies ΔHDCM are given with respect to A′.

As reflected by the experiments above (in particular Scheme 7b), the reaction pathway involves two distinct parts: generation of amidinium D and hydrolytic liberation of aminated amide E (Scheme 8).11 In particular, DFT computations evidence the involvement of a discrete keteniminium species B in the process (Scheme 8) which undergoes nucleophilic addition from the azide component, forming N,N-ketene aminal C′. While the formation of C′ is endergonic (A′ ⇌ B ⇌ C′: ΔGDCMo = +5.4 kcal mol–1), the reaction is ultimately driven by the subsequent highly exergonic extrusion of dinitrogen (TSC′-D, C′ → D: ΔGDCM = −63.2 kcal mol–1).14 The extrusion of N2 is supported by a pivotal π–σ*N–N2 orbital overlap,15 and the formation of amidinium D is a direct consequence of the stereoelectronic implications thereof. Iminium D also represents the final, resting intermediate prior to aqueous workup. The latter is a facile two-step hydrolytic opening (D → E).11 These computational results neatly rationalize the observations of Scheme 7.

In summary, we developed a metal-free, direct α-amination of amides with simple azides that proceeds under mild conditions through electrophilic amide activation. This transformation is highly chemoselective for amides even in the presence of other carbonyl derivatives. Furthermore, it displays high stereoselectivity in multiple contexts, including asymmetric induction. Key mechanistic experiments and DFT analysis pinpoint the intermediacy of a pivotal azirinium/amidinium intermediate with remarkable synthetic versatility.

Acknowledgments

Generous support of this research by the University of Vienna, the ERC (StG 278872) and the FWF (P27194) is acknowledged. Invaluable assistance by Ing. A. Roller (U. Vienna) with crystallographic analysis and Dr. H. Kählig (U. Vienna) with NMR analysis is acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b04061.

Author Contributions

§ These authors contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Albericio F.; Kruger H. G. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 1527. 10.4155/fmc.12.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Newman D. J.; Cragg G. M. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For general reviews, see:; a Liu C. C.; Schultz P. G. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 413. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Young T. S.; Schultz P. G. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 11039. 10.1074/jbc.R109.091306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Maza J. C.; Jacobs T. H.; Uthappa D. M.; Young D. D. Synlett 2016, 27, e6. 10.1055/s-0035-1561855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For general reviews, see:; a Vogt H.; Bräse S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 406. 10.1039/B611091F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Perdih A.; Sollner Dolenc M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2007, 11, 801. 10.2174/138527207780831701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Stevenazzi A.; Marchini M.; Sandrone G.; Vergani B.; Lattanzio M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 5349. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For general reviews, see:; a Guillena G.; Ramón D. J. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2006, 17, 1465. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2006.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Marigo M.; Jørgensen K. A. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2001. 10.1039/B517090G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Vilaivan T.; Bhanthumnavin W. Molecules 2010, 15, 917. 10.3390/molecules15020917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Smith A. M. R.; Hii K. K. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1637. 10.1021/cr100197z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zhou F.; Lia F.-M.; Yu J.-S.; Zhou J. Synthesis 2014, 46, 2983. 10.1055/s-0034-1379255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Maji B.; Yamamoto H. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2015, 88, 753. 10.1246/bcsj.20150040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see:; a Regitz M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1967, 6, 733. 10.1002/anie.196707331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Weininger S. J.; Kohen S.; Mataka S.; Koga G.; Anselme J. P. J. Org. Chem. 1974, 39, 1591. 10.1021/jo00924a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Miura T.; Morimoto M.; Murakami M. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 5214. 10.1021/ol302331k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Scarpino Schietroma D. M.; Monaco M. R.; Bucalossi V.; Walter P. E.; Gentili P.; Bella M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 4692. 10.1039/c2ob25595b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Fu J.-Y.; Wang Q.-L.; Peng L.; Gui Y.-Y.; Wang F.; Tian F.; Xu X.-Y.; Wang L.-X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013, 2864. 10.1002/ejoc.201201701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Vita M. V.; Waser J. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3246. 10.1021/ol401229v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Shevchenko G. A.; Pupo G.; List B. Synlett 2015, 26, 1413. 10.1055/s-0034-1380680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Sandoval D.; Samoshin A. V.; Read de Alaniz J. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4514. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Ötvös S. B.; Szloszár A.; Mándity I. M.; Fülöp F. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 3671. 10.1002/adsc.201500375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Yang X.; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3205. 10.1021/jacs.5b00229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Miles D. H.; Guasch J.; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7632. 10.1021/jacs.5b04518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Ramakrishna I.; Sahoo H.; Baidya M. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3215. 10.1039/C5CC10102F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumasu K.; Yazaki R.; Ohshima T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2664. 10.1021/jacs.5b11773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected recent examples, see:; a Tian J.-S.; Ng K. W. J.; Wong J. R.; Loh T.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9105. 10.1002/anie.201204215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lamani M.; Prabhu K. R. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 14638. 10.1002/chem.201202703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Evans R. W.; Zbieg J. R.; Zhu S.; Li W.; MacMillan D. W. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16074. 10.1021/ja4096472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Jiang Q.; Xu B.; Zhao A.; Jia J.; Liu T.; Guo C. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8750. 10.1021/jo5015855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Jia W.-G.; Li D.-D.; Dai Y.-C.; Zhang H.; Yan L.-Q.; Sheng E.-H.; Wei Y.; Mu X.-L.; Huang K.-W. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 5509. 10.1039/c4ob01027b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Peng B.; Geerdink D.; Farès C.; Maulide N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14968. 10.1021/ja408856p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Peng B.; Geerdink D.; Farès C.; Maulide N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5462. 10.1002/anie.201402229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For elegant examples of metal-free amide activation, see:; a Sisti N. J.; Fowler F. W.; Grierson D. S. Synlett 1991, 1991, 816. 10.1055/s-1991-20888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Thomas E. W. Synthesis 1993, 1993, 767. 10.1055/s-1993-25934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Sisti N. J.; Zeller E.; Grierson D. S.; Fowler F. W. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 2093. 10.1021/jo961403d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Charette A. B.; Grenon M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 1677. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)00040-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Movassaghi M.; Hill M. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 14254. 10.1021/ja066405m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Movassaghi M.; Hill M. D.; Ahmad O. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 10096. 10.1021/ja073912a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Movassaghi M.; Hill M. D. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3485. 10.1021/ol801264u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Barbe G.; Charette A. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 18. 10.1021/ja077463q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Pelletier G.; Bechara W. S.; Charette A. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12817. 10.1021/ja105194s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Bechara W. S.; Pelletier G.; Charette A. B. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 228. 10.1038/nchem.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyba E. P. In Azide and Nitrenes, Reactivity and Utility; Scriven E. F. V., Ed.; Academic Press Inc.: Orlando, FL, 1984, 2–34. [Google Scholar]

- See SI for full crystallographic data, optimization of the reaction conditions, a mechanistic proposal for the formation of 5 and 8 and the DFT computations for the hydrolysis of amidinium D into 3bb.

- Rens M.; Ghosez L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970, 43, 3765. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)98583-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- All DFT computations were carried out at the SMD(DCM) M06-2X/def2-QZVP//M06-2X/6-31+G* level of theory using the Gaussian 09 software package. Frisch M. J., et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2013. For the full citation as well as the full computational details, see the SI.

- The rather long incipient N–N bond (1.67 Å) and rather short incipient C–N bond (1.39 Å) are indicative of a late transition state.

- As judged by NBO analysis, the pivotal π(C=C)→σ*(N–N) orbital interaction adds 15.1 kcal mol–1 of stabilizing energy to TSC′-D. Notably, the very same orbital interaction already adds 4.1 kcal mol–1 worth of stabilizing energy in preceding C′. The existence of a distinct orbital in the HOMO of TSC′-D connecting all three atoms (C=C-N) provides further evidence for this crucial interaction. See the SI for the illustration of the respective MO.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.