Abstract

Purpose of review

There are today 11 mega-countries with more than 100 million inhabitants. Together these countries represent more than 60% of the world's population. All are facing noncommunicable chronic disease (NCD) epidemic where high cholesterol, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases are becoming the main public health concerns. Most of these countries are facing the double burden of malnutrition where undernutrition and obesity coexist, increasing the complexity for policy design and implementation. The purpose of this study is to describe diverse sociodemographic characteristics of these countries and the challenges for prevention and control in the context of the nutrition transition.

Recent findings

Mega-countries are mostly low or middle-income and are facing important epidemiologic, nutrition, and physical activity transitions because of changes in food systems and unhealthy lifestyles. NCDs are responsible of two-thirds of the 57 million global deaths annually. Approximately, 80% of these are in low and middle-income countries. Only developed countries have been able to reduce mortality rates attributable to recognized risk factors for NCDs, in particular high cholesterol and blood pressure.

Summary

Mega-countries share common characteristics such as complex bureaucracies, internal ethnic, cultural and socioeconomic heterogeneity, and complexities to implement effective health promotion and education policies across population. Priorities for action must be identified and successful lessons and experiences should be carefully analyzed and replicated.

Keywords: dyslipidemias, mega-countries, nutrition transition, obesity, physical activity

INTRODUCTION

Mega-countries are defined as countries with a population of at least 100 million inhabitants. Currently, there are 11 nations with this condition: China, India, USA, Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Russia, Japan, and Mexico (in descending order). In addition, for this study we included three countries with population above 90 million inhabitants that might become eventually mega-countries; Philippines, Ethiopia, and Vietnam [1–3]. This group of highly populated countries is experiencing different stages of the epidemiologic, physical activity, and nutrition transitions and has heterogeneous sociodemographic, economic, and cultural conditions [4▪▪]. However, they have also some common characteristics that make this classification useful for analysis from the health policy perspective to identify opportunities for prevention and control of noncommunicable chronic disease (NCDs). Among these, some of the most obvious are: large populations in which even small increases in the prevalence of diseases, have a major impact on thousands of inhabitants, the health system and the national economy, complex bureaucracies which make difficult the coordination of multisectorial policy efforts, big markets, making them a priority target of multinational companies selling tobacco, alcohol, sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), ultra-processed food, motorized vehicles, TVs, and other products associated with unhealthy lifestyles, overall poor regulatory actions to reduce the impact of the obesogenic environment in health, strong marketing and lobbying of junk food and SSB companies to promote their products and protect their business from regulation and taxation, and participation in trade agreements which are usually decided without considering health implications [2,3,5–10].

During the last 3 decades, a number of factors such as economic growth, urbanization, trade agreements, and improvements in technology have resulted in an epidemiologic physical activity and nutrition transition, which is occurring at a different pace in mega-countries [11–14,15▪▪,16,17]. On the one hand, there are countries at a stage of transition in which a small percentage of urbanization is observed and where undernutrition, high infant mortality rates, low life expectancy, and infections are still major public health problems. However, because of the size of their population, the relatively small but increasing prevalence of NCDs, including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and diabetes, are a major health and economic burden, countries in which obesity and NCDs are the main health problem, and countries facing an important double burden of both undernutrition and obesity and NCDs. Although some middle-income countries are experiencing a transition with important progress reducing the undernutrition prevalence, in the mega-country group there are more countries who will transition first to higher prevalences of obesity before controlling undernutrition [18–21]. Recently, low and middle-income countries have experienced an important shift reaching obesity prevalences similar to those of developed countries [22–24,25▪] and while the increase in obesity has slowed down in the latter, there are no success stories on efforts to reduce the prevalence of this disease until now [26▪▪]. Developed countries have been able to decrease mortality attributable to some risk factors such as high cholesterol, glucose, and blood pressure (BP), but low and middle-income countries are showing alarming increases [25▪,27▪▪,28]. A number of factors have contributed to the success in more developed countries, including the combined effect of decreased exposure to tobacco and alcohol consumption, improvements in diet (such as reductions in sodium, fat, and sugar intake), effective investments in preventive programs, physical activity promotion, increased availability of clean potable water, better detection of high-risk populations, improved treatment of CVD and risk factors, and diverse technological developments such as statins, antihypertensive and other drugs, and cardiovascular surgery procedures [14,29,30▪▪,31,32▪,33,34,35▪,36–38]. However, these improvements have only been able to reduce cardiovascular mortality in Central and Western Europe; during the last decades, an absolute increase has been observed in the global rates of cardiovascular mortality [27▪▪].

The purpose of this study is to describe some socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of this heterogeneous group of countries, the current status of the epidemiologic, physical activity, and nutrition transition, the double burden of disease and the challenges to control the rising NCD epidemic.

Box 1.

no caption available

METHODS

For the current analysis, we considered the 11 mega-countries (countries with a population of at least 100 million inhabitants), which are in descending order: China, India, USA, Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Russia, Japan, and Mexico. In addition, we included three countries with population above 90 million inhabitants that might eventually become mega-countries: Philippines, Ethiopia, and Vietnam [39].

Socioeconomic and demographic information

We obtained from the World Bank data site, the most recent international socioeconomic indicators available to characterize this group of countries [1]. We included gross domestic product (GDP) ‘per capita’ (2014), Gini index [a proxy measure of distribution of income within a country where 0 represents perfect equality whereas 100 implies perfect inequality (2010), except Brazil, India, and Philippines (2009) and Japan (2008)], annual population growth percentage (2014), life expectancy at birth (2013), urban population percentage (2014), physicians per 1000 inhabitants (2010), and percentage of literacy rate among population older than 15 years of age (2007–2011). We included some indicators of health and education infrastructure; health expenditure expressed as percentage the GDP (2014), health expenditure per capita (2014) and pupil/teacher ratio (2012–2013) except for Nigeria (2010) and Bangladesh (2011).

Human development index

The index was developed by the United Nations Development Programme more than 25 years ago. It is considered a better measure of development than monetary measures such as the GDP per capita [40,41]. It evaluates three dimensions: health and longevity through life expectancy; access to education through average school years, and standard of living through per capita income (Gross National Income per capita). The most recent human development index (HDI) information was used to classify the mega-countries in four levels of development according to United Nations Development Programme: very high (scores ≥0.8); high (scores ≥0.70 and <0.8); medium (scores ≥0.55 and <0.7); and low (scores <0.55) [42,43]. We later consolidated them in two groups: low and middle-HDI, and high and very high-HDI.

Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors

Standardized prevalences of overweight and obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) in adults and stunting (< −2 SD of height for age), a chronic undernutrition indicator in children under 5 years of age, were obtained from the WHO Global Health Observatory. In addition, prevalences of high cholesterol (≥5.0 mmol/l; 2008), high BP (SBP ≥ 140 and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg; 2014), and fasting blood glucose (≥7.0 mmol/l, 2014), alcohol (2010) and tobacco (2014) consumption (stratified by sex), and physical inactivity (2010) were obtained from the same source [44]. We used the estimated age-standardized sodium consumption (g per day) (2010) [45] and the estimated SSB consumption (servings/day; stratified by sex) in adults 30–40 years [46▪▪].

Noncommunicable chronic diseases mortality and policy efforts

We used Global Burden of Disease data on percentage of age-adjusted mortality per 100 000 inhabitants during 2013, and the annual percentage change of age-standardized mortality from 1990 to 2013 to evaluate its association to country HDI. Finally, we described policy efforts to curve the NCD epidemic among mega-countries using available systematic reviews from the World Health Organization Global Health Observatory [44], the Global Observatory for Physical Activity [47] and the World Cancer Research Fund Nourishing framework site [48,49], in addition to a number of global and local country reports [50,51▪,52–60].

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the basic economic and sociodemographic information of 14 countries included in this analysis (the 11 mega-countries plus three countries with population above 90 million inhabitants). All analyzed countries belong to three continents, Asia (9), America (3) and Africa (2). There is a very wide range of gross domestic product per capita (GDPc) from $46 405.2 in the USA to $315.8 in Ethiopia (2014). Similarly, the range of HDI goes from the highest in the USA (0.91) to the lowest in Ethiopia (0.44). Using the United Nations Development Programme HDI categories there were three countries with low HDI (Pakistan, Nigeria and Ethiopia), five countries with medium HDI (Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, India, and Bangladesh), four countries with high HDI (Russia, Brazil, Mexico, and China) and two with very high HDI (USA and Japan). Once the HDI is adjusted for inequality, all country scores are lower, being Brazil, Nigeria, India, Mexico, and Bangladesh the ones in which the HDI reduction is higher. The Gini index, a proxy of income distribution, shows in ascending order that Brazil, Mexico, Philippines, Vietnam, and Nigeria are the countries with the highest income inequality. The percentage annual population growth was negative or less than one digit in five countries: Japan, Russia, China, USA, and Brazil whereas three countries (Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Pakistan), had an annual population growth of more than 2%. The highest life expectancy at birth was observed in Japan (83.3 years), followed by USA (78.8 years), and Mexico (76.5 years), the lowest one was observed in Nigeria (52.4 years), followed by Ethiopia (63.4 years) and Pakistan (66.0 years). Among these countries there are three with more than 80% urban population (Japan, USA, and Brazil), whereas there are five in which urban population is less than 40% (Ethiopia, India, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Pakistan). USA, Japan and Brazil had the highest health expenditure; USA, Indonesia, and Japan had the lowest pupil/teacher ratio.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic characteristics of mega-countries

| Low middle HDI | High very high HDI | |||||||||||||

| Indicator | Ethiopia | Nigeria | Pakistan | Bangladesh | India | Philippines | Vietnam | Indonesia | China | Brazil | Mexico | Russia | Japan | USA |

| Human Development Index, 2014 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| Category Human Development Index | Low | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | High | High | High | High | Very high | Very High |

| Population (million), 2014 | 96.9 | 177.5 | 185.0 | 159.1 | 1,295.3 | 99.1 | 90.9 | 254.5 | 1,364.3 | 206.1 | 125.4 | 143.8 | 127.1 | 318.9 |

| GDPc (2014) (constant USD 2005) | 315.8 | 1,098.0 | 813.7 | 747.4 | 1,233.9 | 1,662.1 | 1,077.9 | 1,853.8 | 3,862.9 | 5,880.6 | 8,521.9 | 6,843.9 | 37,595.2 | 46,405.2 |

| Gini Index (2010)a | 33.2 | 43.0 | 29.6 | 32.0 | 35.6 | 42.9 | 42.7 | 33.9 | 42.1 | 53.9 | 48.1 | 40.9 | 32.1 | 40.5 |

| Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index, 2014 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.56 | – | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| Annual population growth (%), 2014 | 2.51 | 2.66 | 2.10 | 1.21 | 1.23 | 1.59 | 1.07 | 1.26 | 0.51 | 0.89 | 1.32 | 0.22 | −0.16 | 0.74 |

| Life expectancy at birth 2013 (years) | 63.4 | 52.4 | 66.0 | 71.3 | 67.7 | 68.1 | 75.8 | 68.7 | 75.4 | 74.1 | 76.5 | 71.1 | 83.3 | 78.8 |

| Urban population (%), 2014 | 19.0 | 46.9 | 38.3 | 33.5 | 32.4 | 44.5 | 33.0 | 53.0 | 54.4 | 85.4 | 79.0 | 73.9 | 93.0 | 81.5 |

| Physician (per 1000 people), 2010 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.83 | 0.30 | 0.65 | – | 1.22 | 0.29 | 1.80 | 1.76 | 1.96 | 4.31 | 2.30 | 2.42 |

| Adult literacy rate population 15+ years, 2007–2011 | 39.0 | 51.1 | 55.4 | 59.7 | 69.3 | 95.4 | 93.5 | 92.8 | 95.1 | 90.4 | 93.1 | 99.7 | – | – |

| Health expenditure per capita (current USD$), 2014 | 26.6 | 117.5 | 36.2 | 30.8 | 75.0 | 135.2 | 142.4 | 99.4 | 419.7 | 947.4 | 677.2 | 892.9 | 3,703.0 | 9,402.5 |

| Health expenditure (% GDP), 2014 | 4.9 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 7.1 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 8.3 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 10.2 | 17.1 |

| Pupil/teacher ratio (2010-2013)b | 53.7 | 37.6 (2010) | 42.5 | 40.2 (2011) | 32.3 | 31.4 | 18.9 | 16.1 | 16.9 | 21.2 | 28.0 | 19.6 | 16.7 | 14.5 |

GDPc, gross domestic product per capita.

Data obtained by World Bank (2016).

aBrazil, India, Nigeria, and Philippines: Gini index 2009; Japan: Gini Index 2008.

bNigeria: pupil/teacher ratio 2010; Bangladesh: pupil/teacher ratio 2010.

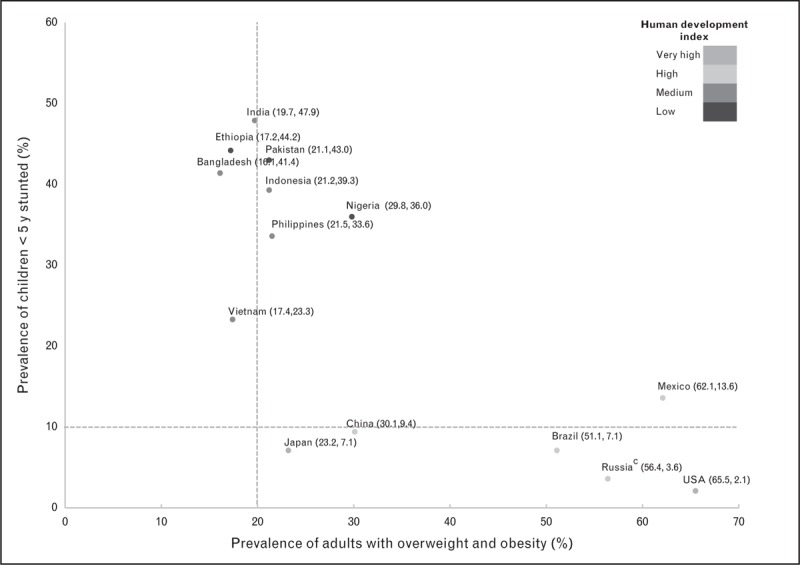

To explore the level of coexistence of less than 5-year children stunting and adult overweight and obesity by country, a proxy of a phenomenon known as the double burden of malnutrition, a plot was constructed with the intersection between the national prevalence of both conditions (Fig. 1). All low/middle-HDI countries had stunting prevalences more than 20%; within this group India, Ethiopia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Indonesia had prevalences more than 40%. Only four mega-countries have stunting prevalences less than 10%: USA, Brazil, China, and Japan and four mega-countries have overweight/obesity prevalence under 20%: Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and India. Among the countries with the highest prevalence of overweight/obesity, Mexico has the highest prevalence of stunting. Similarly, among the countries with the highest prevalence of stunting, Nigeria has the highest prevalence of overweight/obesity being these countries the ones with higher double burden of malnutrition. China and Japan had the lowest combined prevalences of stunting and overweight.

FIGURE 1.

Double burden of malnutrition in mega-countries: coexistence of stuntinga and overweight/obesityb. aStunting prevalence: height-for-age z scores less than 2 SD, obtained by the Global Health Observatory of the WHO, 2010-2011, except for India (2005–2006) and Brazil (2006–2007). bOverweight and Obesity prevalence: BMI at least 25 hg/m2, obtained by the Global Health Observatory of the WHO, 2010. cRussia prevalence of stunting is not national representative of the under 5-year population.

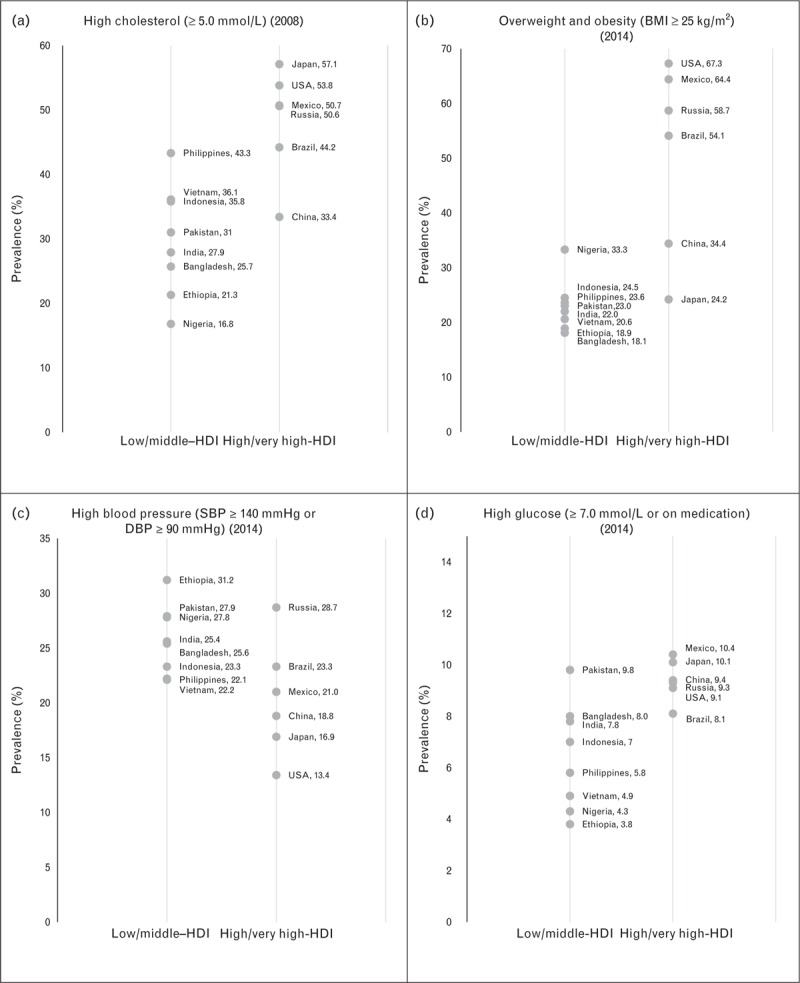

Figure 2 groups the prevalences of high total cholesterol, overweight and obesity, high BP, and elevated fasting blood glucose by country divided in two groups by HDI classification (low/middle and high/very high HDI). In Japan, USA, Mexico, and Russia more than 50% of the population had high cholesterol levels, whereas in India, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Nigeria the prevalences were less than 30%. Overall, the prevalence of cholesterol and overweight/obesity is higher in countries in the high/very high HDI group. The three countries from the American continent (USA, Mexico, and Brazil), together with Russia are the ones with the highest prevalence of overweight and obesity with prevalences more than 50%, whereas the rest of the countries were less than 35%. On the other hand, the prevalences of high BP were higher in the low and middle-HDI group of countries whereas three countries had prevalences less than 20%; USA, Japan, and China. Finally, most of the countries had a prevalence of high blood glucose between 7 and 10%; Mexico and Japan were more than 10% whereas Vietnam, Nigeria, and Ethiopia had prevalences less than 5%.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in mega countries by HDI category. HDI, human development index. Data obtained by the Global Health Observatory of the WHO.

When comparing risk factors for NCDs among mega-countries, the ones with the highest alcohol consumption were Russia, Japan, and USA with prevalences more than 15%. Five out of six countries in the high/very high-HDI group had prevalences more than 10%, only China had prevalence less than 10%. In contrast, with the exception of Nigeria (7%), all other low/middle-HDI mega-countries had prevalences less than 3%. Japan and USA had a physical inactivity prevalence above 30% whereas in India and Russia it was less than 15%. Tobacco is consumed more by men than by women. The highest tobacco consumption prevalence in men was observed in Indonesia (76.2%) and Russia (59.0%), whereas in women it was observed in Russia (22.8%), USA (15.0%), and Brazil (11.3%). Sodium intake appears to be higher in Asian mega-countries such as Japan, China, Vietnam, Philippines, and Russia. SSB servings per day were higher in Mexico followed by the USA in men and women, and were more consumed among high/very high-HDI countries (Table 2).

Table 2.

Major risk factors for the development of noncommunicable diseases in mega-countries

| Heavy drinking past 30 daysa,b % (95%CI) | Insufficiently active adultsa,b % (95%CI) | Use of tobacco products in population at least 15 yearsa % (95%CI) | Estimated sodium intake (g/day)b % (95%CI) | Estimated SSB (servings/day) (30–40 years old) % (95%CI) [46▪▪] | |||

| Year | 2010 | 2010 | 2015 | 2010 [45] | 2010 | ||

| Low/middle HDI | Women | Men | Women | Men | |||

| Ethiopia | 0.6 (0.0–1.2) | 18.9 (4.9–50.1) | 0.5 (0.2–0.8) | 8.9 (6.0–12.1) | 2.27 (1.95–2.67) | 0.26 (0.14–0.43) | 0.28 (0.15–0.47) |

| Nigeria | 7.0 (0.1–8.9) | 22.3 (8.5–66.3) | 1.1 (0.4–2.0) | 17.4 (8.0–28.9) | 2.82 (2.51–3.17) | 0.37 (0.20–0.61) | 0.41 (0.23–0.66) |

| Pakistan | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | 26 (7.2–62) | 3.0 (1.8–4.2) | 41.9 (29.7–57.3) | 3.91 (3.32–4.66) | 0.66 (0.35–1.44) | 0.73 (0.40–1.20) |

| Bangladesh | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) | 26.8 (25.9–27.8) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 39.8 (30.6–50.1) | 3.54 (2.98–4.21) | 0.19 (0.10–0.39) | 0.21 (0.11–0.37) |

| India | 1.6 (0.7–2.6) | 13.4 (12.2–14.8) | 1.9 (1.4–2.5) | 20.4 (14.5–27.3) | 3.72 (3.63–3.82) | 0.42 (0.22–0.72) | 0.47 (0.26–0.77) |

| Philippines | 1.6 (0.7–2.6) | 15.8 (3.6–44.2) | 8.5 (6.6–10.8) | 43.0 (34.6–53.5) | 4.29 (3.65–5.10) | 0.56 (0.31–0.94) | 0.62 (0.34–1.05) |

| Vietnam | 1.3 (0.4–2.1) | 23.9 (16.6–32.9) | 1.3 (0.9–1.6) | 47.1 (35.7–58.5) | 4.59 (3.81–5.46) | 0.32 (0.18–0.54) | 0.35 (0.20–0.57) |

| Indonesia | 2.4 (1.2–3.6) | 23.7 (19–29.1) | 3.6 (2.6–4.5) | 76.2 (59.5–95.5) | 3.36 (3.02–3.76) | 0.35 (0.19–0.57) | 0.37 (0.21–0.64) |

| High/very high HDI | |||||||

| China | 7.5 (5.5–9.5) | 24.1 (21.7–26.5) | 1.8 (1.3–2.2) | 47.6 (36.7–58.6) | 4.83 (4.62–5.05) | 0.07 (0.06–0.08) | 0.08 (0.06–0.09) |

| Brazil | 12.2 (9.7–14.6) | 27.8 (8–3.9) | 11.3 (8.2–14.6) | 19.3 (14.6–24.4) | 4.11 (4.01–4.22) | 0.60 (0.53–0.68) | 0.66 (0.58–0.75) |

| Mexico | 10.9 (8.6–13.3) | 26 (20.5–32.1) | 6.6 (5.2–8.2) | 20.8 (16.4–25.3) | 2.76 (2.57–2.94) | 1.87 (1.36–1.48) | 2.03 (1.46–2.72) |

| Russian Federation | 19.3 (16.3–22.3) | 9.5 (6.8–12.8) | 22.8 (17.6–29.3) | 59.0 (46.6–72.5) | 4.17 (3.95–4.40) | 0.56 (0.32–0.90) | 0.62 (0.34–1.01) |

| Japan | 18.4 (15.4–21.3) | 33.8 (11.1–71.6) | 10.6 (8.0–13.4) | 33.7 (25.9–41.6) | 4.89 (4.71–5.08) | 0.38 (0.32–0.44) | 0.45 (0.38–0.51) |

| USA | 16.2 (13.4–19.0) | 32.4 (29.8–35) | 15.0 (12.1–18.1) | 19.5 (15.7–23.6) | 3.60 (3.50–3.70) | 1.43 (1.25–1.62) | 1.65 (1.44–1.88) |

aWHO Global Health Observatory (2016).

bAge-standardized estimates.

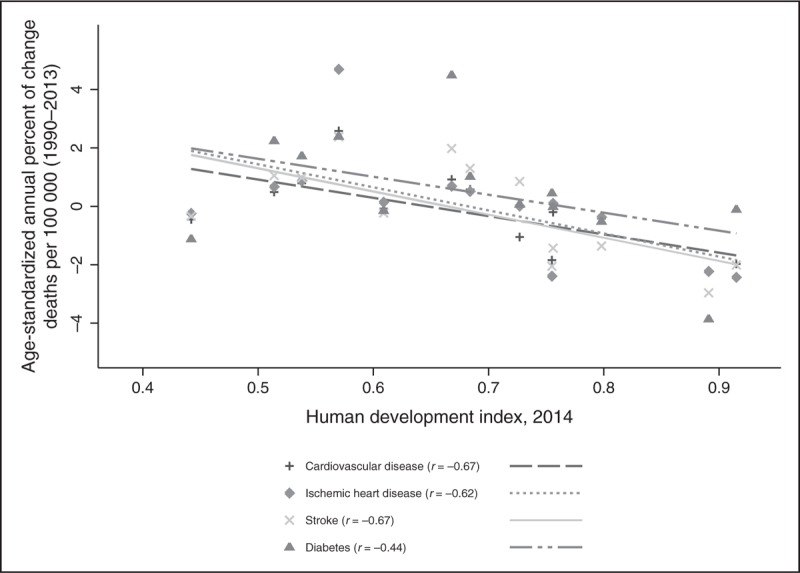

In Fig. 3, we present the annual percentage change of CVD, ischemic heart disease, ischemic stroke, and diabetes mellitus deaths 1990–2013. The four mortality causes show significant negative correlations to the HDI by megacountry.

FIGURE 3.

Annual percentage of change of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, ischemic stroke and diabetes mortality per 100 000 inhabitants (1990–2013) by human development index (2014). Data obtained by Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2016. r, correlation coefficient.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis describes characteristics of 14 mega-countries in which 64.8% of the global cardiovascular mortality occurs. This represents more than 11.2 million deaths per year. These countries have a heterogeneous development and are experiencing different stages of the epidemiologic, physical activity, and nutrition transition. Most of them are middle-income and have a low and middle-HDI. In these countries, the transition to an epidemiologic panorama dominated by NCDs is taking place, whereas high rates of undernutrition are still occurring. This double burden should be addressed with well coordinated intersectorial policies that allow access to traditional diets of better quality without shifting to diets rich in caloric-beverages, ultra-processed foods and high in sugar, fat, and salt [61–63]. Special attention to the promotion of breast-feeding and healthy weaning practices must be in place not only to protect from undernutrition but also from obesity later in life [64]. Some lessons from past experiences in developed countries can be helpful, in particular those of USA and Japan that share the complexities of large populations [14,65]. The recent emphasis on active living and healthier diets using mostly basic foods, avoiding junk food, fast food, and SSBs observed in these countries can be seen as an important step toward healthier lives and could be imported or reinforced in other mega-countries in which the nutrition transition to unhealthy diets is not yet generalized [66,67]. Also, early detection, adequate treatment and other interventions to control risk factors such as high BP, cholesterol, and sugar must be analyzed, implemented with adequate monitoring and evaluation systems. Primary prevention using statins, antihypertensive drugs, or a polypill have showed promising results, and investments on exploring this option should be a priority in countries in which NCDs are increasing and large segments of the population have poor or no access to primary healthcare services [68▪,69▪,70,71▪▪,72–74]. Most mega-countries have developed efforts to reduce consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and salt, and to promote appropriate breast-feeding practices and physical activity (Table 3) [13,14,15▪▪,16,47–49,51▪,52–55,57–60,75–77]. Among the most effective, taxes to tobacco, alcohol, and SSBs have demonstrated to reduce consumption of these unhealthy products and to be a powerful public health tool to complement other strategies to reduce NCDs [4▪▪,51▪,52–54,78,79▪▪,80–90]. Important evidence has been disseminated in the last years on the benefits of salt reduction to reduce CVDs [75,91–95]. In addition, regulation to decrease the use of other unhealthy ingredients such as sugar and saturated/trans fats, to improve food labels to help consumers do healthy choices, to control marketing to children, and to promote physical activity has been recognized as part of the necessary interventions to maximize the opportunity of people adopting healthy lifestyles [10,96–100,101▪,102,103,104▪▪,105–119].

Table 3.

Current policy efforts to curve the non-communicable diseases epidemic among mega-countries

| Country | Tobaccoa | Alcoholb | Salt (SI/SR)c | SSBsd | Breastfeedinge | National plan to promote physical activity |

| Low/middle HDI | ||||||

| Bangladesh | T: 76%, AVE: 61%, VAT: 15% | LMA: No, VAT: 15%, ET: N/A | Yes/Yes | – | EB: 97.8%, EBF < 6m: 42.9%, BFP: yes | Yes |

| Ethiopia | T: 18.77%, AVE: 13.9%, VAT: 4.87% | LMA: 18y, VAT: 15%, ET: b50%, w50%, s100% | Yes/– | – | EB: 96%, EBF < 6m: 49%, BFP: yes | N/A |

| Nigeria | T: 20.63%, AVE: 15.87%, VAT: 4.76% | LMA: 18y, VAT: 5%, ET: b2%, w2%, s2% | Yes/– | – | EB: 97.3%, EBF < 6m: 13.1%, BFP: yes | No |

| Pakistan | T: 60.70%, SE: 46.17%, VAT: 14.53% | LMA: 21y, VAT: No, ET: N/A | Yes/– | – | EB: 94.3%, EBF < 6m: 37.1%, BFP: – | N/A |

| India | T: 60.39%, SE: 42.45%, AVE: 1.27%, VAT: 16.67% | LMA: subnational, VAT: No, ET: N/A | Yes/– | Considering tax MUFB | EB: 95.7%, EBF < 6m: 46.4%, BFP: yes | Yes |

| Indonesia | T: 53.40%, SE: 40.91%, AVE: 4.09%, VAT: 8.40% | LMA: 21y, VAT: 10%, ET: N/A | Yes/Yes | Considering tax | EB: 95.2%, EBF < 6m: 32.4%, BFP: – | Yes |

| Philippines | T: 74.27%, SE: 63.55% VAT: 10.71% | LMA: 18y, VAT: 12%, ET: N/A | Yes/Yes | Considering tax | EB: 87.7%, EBF < 6m: 34%, BFP: yes | N/A |

| Vietnam | T: 41.59%, AVE: 32.50% VAT: 9.09% | LMA: 18y, VAT: 10%, ET: b45%, w45%, s45% | Yes/Yes | – | EB: 97.7%, EBF < 6m: 16.9%, BFP: yes | Yes |

| High/very high HDI | ||||||

| Brazil | T: 64.94%, SE: 20.87%, AVE: 8.10%, VAT: 25%, OT: 10.97% | LMA: 18y, VAT: N/A, ET: b6%, w6%, s5% | –/Yes | Considering tax MUFB | EB: 96.4%, EBF < 6m: 39.8%, BFP: yes | Yes |

| China | T: 44.43%, SE: 0.60%, AVE: 29.30%, VAT: 14.53% | LMA: No, VAT: 17%, ET: bN/A, w1%, s2% | Yes/Yes | MUFB | EB: –, EBF < 6m: –, BFP: yes | Yes |

| Mexico | T: 65.87%, SE: 15.56%, AVE: 36.52%, VAT: 13.79% | LMA: 18y, VAT: 16%, ET: b25%, w25%, s50% | Yes/Yes | Approved tax MUFB | EB: 92.3%, EBF < 6m: 20.3%, BFP: yes | Yes |

| Russian Federation | T: 47.63%, SE: 23.88%, AVE: 8.50%, VAT: 15.25% | LMA: 18y, VAT: 18%, ET: N/A | Yes/– | – | EB: –, EBF < 6m: –, BFP: yes | No |

| Japan | T: 64.36%, SE: 56.95%, VAT: 7.41% | LMA: 20y, VAT: 5%, ET: b5%, w5%, s5% | –/Yes | – | EB: –, EBF < 6m: 21% BFP: yes | Yes |

| United States | T: 42.54%, SE: 37.38% VAT: 5.16% | LMA: 21y, VAT: No, ET: b$3.75, w$0.72%, l$0.2a | Yes/Yes | Approved tax in 1 city. Considering tax in other states MUFB | EB: 73.9%, EBF < 6m: 13.6%, BFP: yes | Yes |

HDI, human development index; N/A, not available; NCD, noncommunicable diseases.

aTobacco: (taxes on the most sold brand of cigarettes (% of retail price)), (T – total, ADE – Ad valorem excise, SE – Specific excise, VAT – value added tax, OT – Other taxes).

bAlcohol (LMA – legal minimum age, ET – excise tax as a percent of the retail price of alcoholic beverages. B – beer, w – wine, s – spirits, l – liquor) *$ per gallon.

cSalt (SI – salt iodization, SR – salt reduction).

dMUFB – Marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children.

eBreastfeeding (EB – ever breastfed, EBF < 6m – exclusive < 6 months breastfeeding, BFP – breastfeeding promotion).

These options are particularly important in middle-income countries, where the burden of NCDs is very high and there is an urgent need to identify complementary policies to achieve positive results whereas education, dissemination, promotion and other healthy behavior-oriented efforts, and longer term policies start to generate positive results too (Table 3 summarizes some of the main policy efforts to curve the NCDs epidemic in mega-countries).

Overall, it is possible to organize the mega-countries in three groups by transition stage. These stages are much correlated to diverse measurements of development: Group 1. The low/middle-HDI group has low GDPc, is mostly rural, and has a high prevalence of chronic undernutrition and very low prevalences of overweight and obesity. Group 2. The high HDI group is composed by four middle-income emerging economies. These countries have an epidemiologic panorama dominated by NCDs and have experienced rapid transitions in the last 3 decades in which most of them went from closed to open economies with international free trade agreements, rapid urbanization, and dramatic changes in lifestyles and food systems. Finally, Group 3 is composed by the two developed mega-countries with very high-HDI, which are still facing important NCDs but show important progress in a number of indicators. These countries have more than four times the GDPc of any country in Group 2, the highest health expenditure per capita, are almost completely urban with very low rates of undernutrition. However, these nations are also in an important need of alternative models to accelerate the prevention and control of NCDs.

Although low/middle-HDI countries in general will have a transition similar to the one experienced by high/very high countries, some characteristics might differ. For example, a number of countries such as Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Indonesia have a predominant Islam religion where the practice of alcohol consumption is forbidden and therefore cirrhosis because of alcohol use is very low. The poor regulation in low and middle-HDI countries has allowed an important rise in tobacco consumption that has migrated to these nations when more developed ones installed strong regulations on marketing, labeling as well as tobacco taxes. Special attention must be placed in the generalized tobacco consumption in Indonesia where in addition 90% of active smokers report so in the house exposing other family members to secondhand smoke. International experiences could allow this country to overcome this unhealthy practice. All mega-countries report tobacco taxation, however, the total amount of tax is remarkably low in Ethiopia and Nigeria (<21%). Seven mega-countries have a total tax more than 60%; Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, and Philippines in the low/middle HDI group and Brazil, Mexico, and Japan in the high/very high HDI group. In addition, taxes are common in alcoholic beverages. Other policies and regulations such as legal minimum age for tobacco and alcohol, or designated areas for consumption have been implemented. Similarly a number of mega-countries are considering soda taxes as a potential option to decrease consumption. Mexico has adopted a 10% excise tax and a similar measure has been approved in some cities of USA [54,79▪▪].

Although most low/middle-income mega-countries have a relatively low prevalence of overweight and obesity, the WHO recommends the use of lower BMI cut points for Asian population as there is evidence of higher prevalences of diabetes and CVD at lower BMI levels [120]. Japan, with low obesity levels, has a high prevalence of hypercholesterolemia. It has increased with the epidemiologic/nutrition transition since the 1960s and currently the highest among the mega-countries. Similarly, the prevalence of high blood glucose in this country is the second highest. This reflects the need to intensify actions to prevent and control emerging risk factors while maintaining successful efforts to decrease others such as high BP [121].

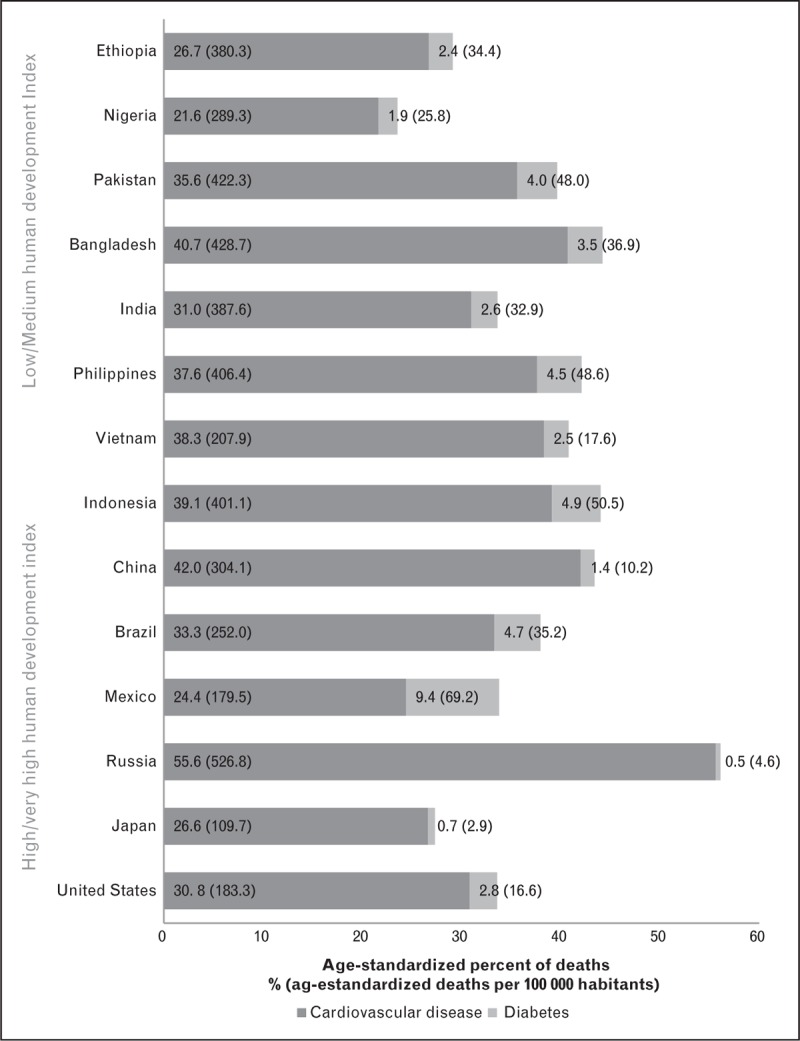

The highest prevalence of overweight and obesity in the world is located in the American continent [26▪▪]. The two most obese mega-countries are also the ones with the highest SSBs number of servings per day [46▪▪]. SSBs are not only associated with obesity but also with diabetes, dyslipidemias, metabolic syndrome, CVDs, and dental health among other health problems [29,122–128]. Russia and Mexico are the mega-countries with the largest percentage of mortality because of CVD and diabetes, respectively. Bangladesh has the highest CVD and diabetes-aggregated mortality among the low/middle-HDI group (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of deaths attributable to cardiovascular disease and diabetes in mega-countries (2013). Data obtained by Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare. Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2016.

Finally, it is important in large economies to consider the implications of trade and other macro policies on individual behavior. Shifts in the food system, including prices, distribution, accessibility and quality occur, as consequences of macro policies such as trade, subsidies/incentives and agricultural policies. This in turn, tends to have effects on population health that must be considered by policy makers as one of the components of the decision analysis [7,8,129,130].

CONCLUSION

The annual percentage change (1990–2013) of CVD, ischemic heart disease, ischemic stroke, and diabetes mortality shows a significant negative trend by HDI of the mega-countries, suggesting that lower HDI mega-countries are shifting to higher mortality by these causes whereas higher HDI are stabilizing. The characteristics of the transition has been described and analyzed and the available information must allow the health and policy-planning sector to identify priorities to diminish the burden of disease. Table 4 summarizes characteristics, expected epidemiological panorama and priorities for low/middle, high/very high-HDI mega-countries.

Table 4.

Stages of the nutrition transition and challenges for mega-countries to address the burden of non-communicable chronic diseasesa

| Country group | Characteristics | What could be expected in the next decades? | What priorities must be addressed to diminish the burden of NCDs? |

| Low-Middle HDI | Mostly rural/labor-intensive work low sedentarism | Increasing urbanization trend. Decrease in physical activity associated with shifts to lower labor-intensive occupations and active transportation. | Raise priority of NCDs in development of national policies |

| Pattern 3 of the nutrition transition (receding famine) Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam | Epidemiologic panorama dominated by under nutrition, but even low prevalence of NCDs represent a significant burden | Decreasing prevalence of stunting. Increasing prevalence of NCDs associated to national growth, trade and shifts in the food systems with low priority and resources from the governments and health sector to respond. | Improve/develop surveillance and monitoring systems for NCDs |

| Increasing prevalence trends of NCDs (obesity, high blood cholesterol, blood pressure and blood sugar) | Higher prevalence of CVD at lower BMI levels than in higher HDI megacountries | Implement policies to promote adequate urban planning focused on active communities, active transportation and public transportation | |

| Elevated population growth | Tobacco consumption becoming major public health problem in particular among males | Disincentives for use of cars. Promotion of physical activity to compensate for increasingly sedentary jobs | |

| Starchy, high fiber, hydration mostly with water | Increasing consumption of processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages and fast food | Reinforcement/Implementation of taxes and strict regulation to disincentive tobacco consumption | |

| Increasing consumption of tobacco | Alcohol consumption not expected to increase in most of these countries due to Muslim religion practices | Promotion and incentives to reinforce/maintain adequate breast-feeding practices | |

| Policies and incentives to maintain and value traditional foods and diets as the key to adequate nutrition. Guidelines for healthy hydration and disincentives to the development of SSBs industry. | |||

| Introducing/improving nutrition education with emphasis on the unhealthy effects of high added sugar, salt and saturated/trans fats intake | |||

| High HDI | Mostly urban/physical activity very low | Increasing urbanization, often without proper urban planning. Decrease in physical activity (due mostly to shifts in labor) and active transportation | Raise priority of NCDs in design of national policies with a multisectoral approach. Develop monitoring systems to evaluate progress in NCDs prevention and control at global, regional and national levels |

| Pattern 4 of the nutrition transition (rise of noncommunicable diseases) Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia | Epidemiologic panorama dominated by NCDs (obesity, high blood cholesterol, blood pressure and blood sugar) | Decreasing prevalence of stunting. NCDs recognized as the main public health problem, however lack of comprehensive policies to tackle the epidemic | Promote a strong focus on urban planning considering active transportation, walkability and active living. Disincentives such as taxes and regulation for the use of cars and incentives for use of public transportation |

| High tobacco, SSBs, fast foods and processed foods consumption. Poor potable water availability | Tobacco consumption remains a major public health problem with increases in consumption by vulnerable groups (young adults, women, low-income, ethnic minorities) | Continuing/improving efforts to reduce tobacco, SSBs and alcohol consumption: taxation, marketing and labeling regulations. Avoid subsidies on unhealthy ingredients/avoid policies that increase availability of sugar, high fructose and other caloric sweeteners, salt and saturated fats | |

| Poor public transportation, inadequate/insufficient public parks | Increasing consumption of processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, fast food | Improve health care response to the rapid rise in NCDs: review and update health care curricula and training, massive education campaigns, early detection, and effective treatment and control | |

| Lack of adequate regulations to protect children from unhealthy food and beverage marketing | Imported low-cost solutions to control CVD risk factors such as statins, antihypertensive drugs and aspirin will become more available | Develop creative solutions to address de NCDs burden such as: national soda taxation programs, strong healthy lifestyles programs, labeling and marketing regulations, polypill interventions in populations with poor access to health care, etc. Import effective initiatives and technology | |

| Transnational food companies lobbing against health policy attempts to modify food environment | Trends on implementation of creative national policies to improve food environment (soda tax, ultra processed food marketing and labeling regulation, physical activity promotion) | Develop international trade agreements that include healthy lifestyle considerations | |

| Very High HDI | Mostly urban/physical activity very low however increasing, particularly on higher socioeconomic segments | Urban planning improving, with emphasis on walkability, active living, sustainability and environment. | Strengthen national policies and plans for the prevention and control of NCDs |

| Pattern 5 of the Nutrition Transition (desired societal/ behavioral change) Japan, USA | Epidemiologic panorama dominated by obesity and NCDs, however, reductions in smoking, SSBs and other risk factors | Stabilization/ saturation equilibrium/ slow reduction of obesity and NCDs | Promote research for the prevention and control of NCDs at global and national levels |

| Relatively good public transportation, public parks, and potable water availability. Trends toward the practice of active transportation | Vulnerable groups such as low socio economic sectors, women, adolescents and minorities with higher exposure to unhealthy lifestyles: tobacco consumption, ultra processed foods, SSBs, fast foods, inactive transportation, poor access to incentives for physical activity | Continued improvement of environments to promote healthy lifestyles with emphasis on vulnerable groups (such as low-income population, disadvantaged ethnic groups, women and adolescents), to reduce inequalities in health | |

| Increasing trend to local, traditional unprocessed foods and healthy hydration | Effective solutions to control some CVD risk factors such as statins, antihypertensive drugs and aspirin widely available at low cost to the vast majority of population | Import effective national policies implemented in High HDI countries such as soda tax, ultra processed front-of-pack labeling, cycling paths, nation wide physical fitness programs, etc. | |

| Decreasing trend in consumption of processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages and fast food franchises in particular on higher socioeconomic segments of the population | Control of emerging risk factors must be emphasized (high cholesterol and glucose in Japan; high tobacco consumption and sugar-sweetened beverages consumption in USA). | ||

| Unhealthy products migrating to emerging, less regulated markets in other countries | Priority to low-income population and other disadvantaged minorities and vulnerable groups | ||

| Promote social responsibility and fair trade of companies attempting to sell unhealthy products overseas |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDI, human development index; NCD, noncommunicable chronic disease; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage.

aPatterns of the nutrition transition according to Popkin (2015).

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

The work was carried out with support from the International Development Research Centre (INFORMAS project no. 107–731-001). Additional funding was provided by NIH-Fogarty RO3 project no. TW009061 and an unrestricted research grant from Sanofi-Aventis to the National Institute of Public Health.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.The World Bank. World Bank Open Data: The World Bank Group; 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/ [Accessed 4 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douglas KA, Yang G, McQueen DV, Puska P. McQueen DV, Puska P. Mega country health promotion network surveillance initiative. Global behavioral risk factor surveillance. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2003. 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Noncommunicable Disease Prevention and Health Promotion WHOW. Mega Country Health Promotion Network Meeting on Diet, Physical Activity and Tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO) 2003. Contract No.: WHO/NMH/NPH/NCP/03.05. [Google Scholar]

- 4▪▪.Popkin BM. Nutrition transition and the global diabetes epidemic. Curr Diab Rep 2015; 15:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The reference has an updated description of the epidemiologic transition theory and interpretation.

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO), World Health Organization Department of NCD, Prevention, Health Promotion. Mega country health promotion network behavioural risk factor surveillance guide. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barquera S. Respuesta de la Organización Mundial de la Salud al rápido crecimiento de las enfermedades crónicas: reunión de la red de los megapaíses. Salud publica de Mexico 2002; 44:79–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collier R. Liberal trade laws linked to obesity. CMAJ 2014; 186:414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friel S, Hattersley L, Snowdon W, et al. Monitoring the impacts of trade agreements on food environments. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 1:120–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sacks G, Swinburn B, Kraak V, et al. A proposed approach to monitor private-sector policies and practices related to food environments, obesity and noncommunicable disease prevention. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 1:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popkin BM. Bellagio Meeting g. Bellagio Declaration 2013: countering Big Food's undermining of healthy food policies. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 2:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.BM Popkin. Understanding the nutrition transition. Urbanisation and health newsletter 1996:3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popkin BM. Nutrition in transition: the changing global nutrition challenge. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2001; 10 (Suppl):S13–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng SW, Popkin BM. Time use and physical activity: a shift away from movement across the globe. Obes Rev 2012; 13:659–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Freedman G, Engell RE, et al. Prevalence of physical activity and obesity in US counties, 2001-2011: a road map for action. Popul Health Metr 2013; 11:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15▪▪.Ng SW, Howard AG, Wang HJ, et al. The physical activity transition among adults in China: 1991-2011. Obes Rev 2014; 15 suppl 1:27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The study describes aspects of the physical activity transition in one of the largest megacountries in the world.

- 16.Hallal PC, Cordeira K, Knuth AG, et al. Ten-year trends in total physical activity practice in Brazilian adults: 2002-2012. J Phys Act Health 2014; 11:1525–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medina C, Janssen I, Campos I, Barquera S. Physical inactivity prevalence and trends among Mexican adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT) 2006 and 2012. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doak CM, Adair LS, Bentley M, et al. The dual burden household and the nutrition transition paradox. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005; 29:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popkin BM. The shift in stages of the nutrition transition in the developing world differs from past experiences!. Public Health Nutr 2002; 5:205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84:289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barquera S, Peterson KE, Must A, et al. Coexistence of maternal central adiposity and child stunting in Mexico. Int J Obes 2007; 31:601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popkin BM, Slining MM. New dynamics in global obesity facing low- and middle-income countries. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 2:11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. The nutrition transition: worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004; 28 suppl 3:S2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popkin BM. The nutrition transition in low-income countries: an emerging crisis. Nutr Rev 1994; 52:285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25▪.Barquera S, Pedroza-Tobias A, Medina C, et al. Global overview of the epidemiology of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Arch Med Res 2015; 46:328–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The study describes characteristics of CVD mortality by gross domestic product per capita with averages by income group using all countries in the world.

- 26▪▪.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384:766–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The most updated and complete reference for epidemiology of obesity in the world until today.

- 27▪▪.Roth GA, Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic drivers of global cardiovascular mortality. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1333–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Using data from the latest GBD this article discusses the main drivers in global CVD mortality.

- 28.Moran AE, Roth GA, Narula J, Mensah GA. 1990–2010 global cardiovascular disease atlas. Glob Heart 2014; 9:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levenson JW, Skerrett PJ, Gaziano JM. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease: the role of risk factors. Prev Cardiol 2002; 5:188–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30▪▪.Moran AE, Odden MC, Thanataveerat A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hypertension therapy according to 2014 guidelines. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The article presents cost-effectiveness of hypertension therapy, this must support bold policies to reduce CVD mortality around the globe.

- 31.Wang YC, Cheung AM, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of blood pressure screening in adolescents in the United States. J Pediatr 2011; 158:257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32▪.Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis DP. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ 2014; 349:g4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Important meta-analysis of RCT on the effect of HDL drug treatments on risk.

- 33.Nordestgaard BG, Varbo A. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease. Lancet 2014; 384:626–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vale N, Nordmann AJ, Schwartz GG, et al. Statins for acute coronary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 9:CD006870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35▪.Robinson JG. Starting primary prevention earlier with statins. Am J Cardiol 2014; 114:1437–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Discussion on primary prevention with statins. An important reference to consider this policy.

- 36.Opie LH. Present status of statin therapy. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2015; 25:216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dombrowski SU, Avenell A, Sniehott FF. Behavioural interventions for obese adults with additional risk factors for morbidity: systematic review of effects on behaviour, weight and disease risk factors. Obes Facts 2010; 3:377–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebrahim S, Taylor F, Ward K, et al. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001561.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kennedy E. Healthy lifestyles… healthy people: the mega country health promotion network. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2002; 11:S738–S739. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sen A. The ends and means of development. Development as Freedom: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart F. Capabilities and human development: beyond the individual: the critical role of social institutions and social competencies. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Reports New York, NY: UNDP; 2016. http://hdr.undp.org/en/humandev [Accessed 4 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jahan S, Mukherjee S, Kovacevic M, et al. Human development report 2015: work for human development. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Observatory 2016. http://www.who.int/gho/countries/en/ [Accessed 4 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 2013; 3:e003733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46▪▪.Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, et al. Global, regional, and national consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices, and milk: a systematic assessment of beverage intake in 187 countries. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0124845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Evidence in 187 countries of high consumption of SSBs, a major driver of the NCD epidemic around the globe.

- 47.(WHO) WHO. Global Observatory for Physical Activity: World Health Organization; 2016. http://www.globalphysicalactivityobservatory.com/country-cards/ [Accessed 4 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Cancer Research Fund international. NOURISHING framework 2016. http://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-framework/improve-food-supply [Accessed 4 April 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hawkes C, Jewell J, Allen K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related noncommunicable diseases: the NOURISHING framework. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 2:159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lachat C, Otchere S, Roberfroid D, et al. Diet and physical activity for the prevention of noncommunicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic policy review. PLoS Med 2013; 10:e1001465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51▪.Basu S, Vellakkal S, Agrawal S, et al. Averting obesity and type 2 diabetes in India through sugar-sweetened beverage taxation: an economic-epidemiologic modeling study. PLoS Med 2014; 11:e1001582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A modeling study in India that shows the potential effects to prevent diabetes of a SSB tax.

- 52.Jou J, Techakehakij W. International application of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxation in obesity reduction: factors that may influence policy effectiveness in country-specific contexts. Health Policy 2012; 107:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Claro RM, Levy RB, Popkin BM, Monteiro CA. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes in Brazil. Am J Public Health 2012; 102:178–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Falbe J, Rojas N, Grummon AH, Madsen KA. Higher retail prices of sugar-sweetened beverages 3 months after implementation of an excise tax in Berkeley, California. Am J Public Health 2015; 105:2194–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malta DC, Barbosa da Silva J. Policies to promote physical activity in Brazil. Lancet 2012; 380:195–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barquera S, Rivera J, Campos-Nonato I, et al. Bases técnicas del Acuerdo Nacional para la Salud Alimentaria. Estrategia contra el sobrepeso y la obesidad. México, DF: Secretaría de salud; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization, Harper C. Vietnam noncommunicable disease prevention and control programme 2002–2010 implementation review. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Selvaraj S, Srivastava S, Karan A. Price elasticity of tobacco products among economic classes in India, 2011-2012. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e008180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.National Physical Activity Plan Alliance. National Physical Activity Plan. National Physical Activity Plan Alliance, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nahar Q, Choudhury S, Faruque O, Sultana S, Siddiquee M. Dietary Guidelines for Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (BIRDEM), 2013 June 2013. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monteiro CA, Moubarac JC, Cannon G, et al. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 2:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Popkin B, Monteiro C, Swinburn B. Overview: bellagio conference on program and policy options for preventing obesity in the low- and middle-income countries. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 2:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brinsden H, Lobstein T, Landon J, et al. Monitoring policy and actions on food environments: rationale and outline of the INFORMAS policy engagement and communication strategies. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 1:13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jebb SA, Aveyard PN, Hawkes C. The evolution of policy and actions to tackle obesity in England. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 2:42–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohira T, Iso H. Cardiovascular disease epidemiology in Asia: an overview. Circ J 2013; 77:1646–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major noncommunicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012; 380:219–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heath GW, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, et al. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet 2012; 380:272–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68▪.McCarthy M. US panel recommends statins for adults aged 40 to 75 at 10% or greater risk of cardiovascular disease. BMJ 2015; 351:h7008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Discussion on the potential use of statins to prevent CVD in adults that must be considered on national policies.

- 69▪.Mortensen MB, Afzal S, Nordestgaard BG, Falk E. Primary prevention with statins: acc/aha risk-based approach versus trial-based approaches to guide statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66:2699–2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Disussion on primary prevention using statins.

- 70.Fletcher K, Mant J, McManus R, Hobbs R. Programme Grants for Applied Research. The Stroke Prevention Programme: a programme of research to inform optimal stroke prevention in primary care. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library Copyright (c) Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Fletcher et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 71▪▪.Selak V, Harwood M, Raina Elley C, et al. Polypill-based therapy likely to reduce ethnic inequities in use of cardiovascular preventive medications: Findings from a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016; doi: 10.1177/2047487316637196. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Discussion on the value of polypill as an alternative to reduce CVD in vulnerable populations.

- 72.Chrysant SG, Chrysant GS. Usefulness of the polypill for the prevention of cardiovascular disease and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 2016; 18:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wald NJ, Luteijn JM, Morris JK, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of the polypill in the primary prevention of myocardial infarction and stroke. Eur J Epidemiol 2016; 31:415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lafeber M, Spiering W, Visseren FL, Grobbee DE. Multifactorial prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with hypertension: the cardiovascular polypill. Curr Hypertens Rep 2016; 18:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cappuccio FP, Capewell S, Lincoln P, McPherson K. Policy options to reduce population salt intake. BMJ 2011; 343:d4995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Misra A, Nigam P, Hills AP, et al. Consensus physical activity guidelines for Asian Indians. Diabetes Technol Ther 2012; 14:83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hidayat B, Thabrany H. Cigarette smoking in Indonesia: examination of a myopic model of addictive behaviour. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010; 7:2473–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brownell KD, Farley T, Willett WC, et al. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1599–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79▪▪.Colchero MA, Popkin BM, Rivera JA, Ng SW. Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: observational study. BMJ 2016; 352:h6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First national evaluation of a SSB tax (soda tax) demonstrating that consumption can be reduced with these policies.

- 80.Lee JM, Chen MG, Hwang TC, Yeh CY. Effect of cigarette taxes on the consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, tea and coffee in Taiwan. Public Health 2010; 124:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bond ME, Williams MJ, Crammond B, Loff B. Taxing junk food: applying the logic of the Henry tax review to food. Med J Aust 2010; 193:472–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martire KA, Mattick RP, Doran CM, Hall WD. Cigarette tax and public health: what are the implications of financially stressed smokers for the effects of price increases on smoking prevalence? Addiction 2011; 106:622–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chaloupka FJ. Maximizing the public health impact of alcohol and tobacco taxes. Am J Prev Med 2013; 44:561–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Young-Wolff KC, Kasza KA, Hyland AJ, McKee SA. Increased cigarette tax is associated with reductions in alcohol consumption in a longitudinal U.S. sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014; 38:241–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gigliotti A, Figueiredo VC, Madruga CS, et al. How smokers may react to cigarette taxes and price increases in Brazil: data from a national survey. BMC Public Health 2014; 14:327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krauss MJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Plunk AD, et al. Effects of state cigarette excise taxes and smoke-free air policies on state per capita alcohol consumption in the United States, 1980 to 2009. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014; 38:2630–2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roehr B. Soda tax’ could help tackle obesity, says US director of public health. BMJ 2009; 339:b3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Powell LM, Chriqui J, Chaloupka FJ. Associations between state-level soda taxes and adolescent body mass index. J Adolesc Health 2009; 45 (3 Suppl):S57–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sturm R, Powell LM, Chriqui JF, Chaloupka FJ. Soda taxes, soft drink consumption, and children's body mass index. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010; 29:1052–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cecchini M, Sassi F, Lauer JA, et al. Tackling of unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and obesity: health effects and cost-effectiveness. Lancet 2010; 376:1775–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:590–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Coxson PG, Cook NR, Joffres M, et al. Mortality benefits from US population-wide reduction in sodium consumption: projections from 3 modeling approaches. Hypertension 2013; 61:564–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Coxson PG, Bibbins-Domingo K, Cook NR, et al. Response to mortality benefits from U.S. population-wide reduction in sodium consumption: projections from 3 modeling approaches. Hypertension 2013; 61:e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bibbins-Domingo K. The institute of medicine report sodium intake in populations: assessment of evidence: summary of primary findings and implications for clinicians. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:136–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Barquera S, Appel LJ. Reduction of sodium intake in the Americas: a public health imperative. Rev Panam Calud Publica 2012; 32:251–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 2013; 346:e7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Saturated fat and cardiometabolic risk factors, coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes: a fresh look at the evidence. Lipids 2010; 45:893–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, et al. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:624–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Recommendations from a Pan American Health Organization Expert Consultation on the Marketing of Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children in the Americas. Washington, DC: 2011 Contract No.: ISBN: 978-92-75-11638-8. [Google Scholar]

- 100.World Health Organization (WHO). Set of recommendations on the marketing of foods and nonalcoholic beverages to children. Washington DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 101▪.Theodore FL, Tolentino-Mayo L, Hernandez-Zenil E, et al. Pitfalls of the self-regulation of advertisements directed at children on Mexican television. Pediatr Obes 2016; doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12144. PubMed PMID: 27135300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Recent evidence of lack of usefulness of self-regulatory programs to control marketing of food and beverages to children.

- 102.Sacks G, Rayner M, Swinburn B. Impact of front-of-pack ’traffic-light’ nutrition labelling on consumer food purchases in the UK. Health Promot Int 2009; 24:344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Galbraith-Emami S, Lobstein T. The impact of initiatives to limit the advertising of food and beverage products to children: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2013; 14:960–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104▪▪.Barrera LH, Rothenberg SJ, Barquera S, Cifuentes E. The toxic food environment around elementary schools and childhood obesity in Mexican cities. Am J Prev Med 2016; Epub 2016/04/07. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.021. PubMed PMID: 27050412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Evidence of the importance of the enrivonment around schools to improve healthy nutrition in developing populations.

- 105.Gosliner W, Madsen KA. Marketing foods and beverages: why licensed commercial characters should not be used to sell healthy products to children. Pediatrics 2007; 119:1255–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Swinburn B, Sacks G, Lobstein T, et al. The 'Sydney Principles’ for reducing the commercial promotion of foods and beverages to children. Public Health Nutr 2008; 11:881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sharma LL, Teret SP, Brownell KD. The food industry and self-regulation: standards to promote success and to avoid public health failures. Am J Public Health 2010; 100:240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Potvin Kent M, Dubois L, Wanless A. Self-regulation by industry of food marketing is having little impact during children's preferred television. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011; 6:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dutton DJ, Campbell NR, Elliott C, McLaren L. A ban on marketing of foods/beverages to children: the who, why, what and how of a population health intervention. Can J Public Health 2012; 103:100–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cairns G, Angus K, Hastings G, Caraher M. Systematic reviews of the evidence on the nature, extent and effects of food marketing to children. A retrospective summary. Appetite 2013; 62:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lobstein T. Research needs on food marketing to children. Report of the StanMark project. Appetite 2013; 62:185–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Carter MA, Signal L, Edwards R, et al. Food, fizzy, and football: promoting unhealthy food and beverages through sport: a New Zealand case study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bragg MA, Yanamadala S, Roberto CA, et al. Athlete endorsements in food marketing. Pediatrics 2013; 132:805–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kelly B, King L, Baur L, et al. Monitoring food and nonalcoholic beverage promotions to children. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 1:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jenkin G, Madhvani N, Signal L, Bowers S. A systematic review of persuasive marketing techniques to promote food to children on television. Obes Rev 2014; 15:281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mallarino C, Gomez LF, Gonzalez-Zapata L, et al. Advertising of ultra-processed foods and beverages: children as a vulnerable population. Rev Saude Publica 2013; 47:1006–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Standing Committee on Childhood Obesity Prevention; Food and Nutrition Board; Institute of Medicine. Challenges and opportunities for change in food marketing to children and youth: workshop summary. Washington DC: The National Academy of Sciences; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kelly B, Hebden L, King L, et al. Children's exposure to food advertising on free-to-air television: an Asia-Pacific perspective. Health Promot Int 2014; 31:144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rayner M, Wood A, Lawrence M, et al. Monitoring the health-related labelling of foods and nonalcoholic beverages in retail settings. Obes Rev 2013; 14 suppl 1:70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004; 363:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ueshima H, et al. Executive summary of Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guideline for diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases for Japanese. J Atheroscler Thromb 2007; 14:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bomback AS, Derebail VK, Shoham DA, et al. Sugar-sweetened soda consumption, hyperuricemia, and kidney disease. Kidney Int 2010; 77:609–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bernstein AM, de Koning L, Flint AJ, et al. Soda consumption and the risk of stroke in men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 95:1190–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pereira MA. Diet beverages and the risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease: a review of the evidence. Nutr Rev 2013; 71:433–440.doi: 10.1111/nure.12038. PubMed PMID: 23815142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hu FB, Malik VS. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiol Behav 2010; 100:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 2010; 121:1356–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Huang C, Huang J, Tian Y, et al. Sugar sweetened beverages consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Atherosclerosis 2014; 234:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Siervo M, Montagnese C, Mathers JC, et al. Sugar consumption and global prevalence of obesity and hypertension: an ecological analysis. Public Health Nutr 2014; 17:587–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.De Vogli R, Kouvonen A, Gimeno D. ‘Globesization’: ecological evidence on the relationship between fast food outlets and obesity among 26 advanced economies. Crit Public Health 2011; 21:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- 130.De Vogli R, Kouvonen A, Gimeno D. The influence of market deregulation on fast food consumption and body mass index: a cross-national time series analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2014; 92:99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]