Abstract

Resistance mechanisms to Verticillium wilt are well-studied in tomato, cotton, and Arabidopsis, but much less in legume plants. Because legume plants establish nitrogen-fixing symbioses in their roots, resistance to root-attacking pathogens merits particular attention. The interaction between the soil-borne pathogen Verticillium alfalfae and the model legume Medicago truncatula was investigated using a resistant (A17) and a susceptible (F83005.5) line. As shown by histological analyses, colonization by the pathogen was initiated similarly in both lines. Later on, the resistant line A17 eliminated the fungus, whereas the susceptible F83005.5 became heavily colonized. Resistance in line A17 does not involve homologs of the well-characterized tomato Ve1 and V. dahliae Ave1 genes. A transcriptomic study of early root responses during initial colonization (i.e., until 24 h post-inoculation) similarly was performed. Compared to the susceptible line, line A17 displayed already a significantly higher basal expression of defense-related genes prior to inoculation, and responded to infection with up-regulation of only a small number of genes. Although fungal colonization was still low at this stage, the susceptible line F83005.5 exhibited a disorganized response involving a large number of genes from different functional classes. The involvement of distinct phytohormone signaling pathways in resistance as suggested by gene expression patterns was supported by experiments with plant hormone pretreatment before fungal inoculation. Gene co-expression network analysis highlighted five main modules in the resistant line, whereas no structured gene expression was found in the susceptible line. One module was particularly associated to the inoculation response in A17. It contains the majority of differentially expressed genes, genes associated with PAMP perception and hormone signaling, and transcription factors. An in silico analysis showed that a high number of these genes also respond to other soil-borne pathogens in M. truncatula, suggesting a core of transcriptional response to root pathogens. Taken together, the results suggest that resistance in M. truncatula line A17 might be due to innate immunity combining preformed defense and PAMP-triggered defense mechanisms, and putative involvement of abscisic acid.

Keywords: gene co-expression analysis, hormone signaling, legumes, PAMP-triggered immunity, quantitative disease resistance, root disease, soil-borne pathogens, transcriptomics

Introduction

Plants continuously have to cope with attacks from pathogens or pests. Although in most cases these attacks are efficiently encountered by the plants' natural defense mechanisms, plant disease is still a major constraint in agricultural productivity. Breeding for pathogen resistance to answer a growing demand for food supply while reducing pesticide use, needs in-depth understanding of plant disease resistance mechanisms.

Plant innate immunity is an active defense system taking place after a pathogen had overcome preformed defenses. The perception of conserved microbial molecular signatures (pathogen-associated molecular patterns, PAMPs) by plant receptors then initiates signaling cascades and transcription reprogramming leading to the so-called PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI; Zipfel, 2014). Main responses driven by PTI are the synthesis of antimicrobial compounds and pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins. However, this innate immunity can be inactivated by adapted pathogens which secrete effector molecules which interrupt the signal transduction leading to PTI. A co-evolutionary arms race between host plants and pathogens has led to a second layer of plant defense called effector-triggered immunity (ETI), which relies on direct or indirect recognition of pathogen effectors by plant intracellular resistance (R) proteins (Dangl et al., 2013). ETI, which is conditioned by a single R gene typically yields complete (qualitative) disease resistance against pathogens containing the recognized effector. It is thus specific to pathogen race and easily overcome by the evolution of new races (Dangl et al., 2013).

In contrast to qualitative resistance, quantitative disease resistance (QDR) is characterized by a continuous range of phenotypes within segregating or natural populations (Poland et al., 2009). It is conditioned by multiple genes of sometimes small effect (Quantitative Trait Loci, QTL) which may further interact with the environment (Roux et al., 2014) and may lead to total absence of symptoms in genotypes gathering all favorable alleles. QDR is not specific of pathogen race offering thus a broader spectrum, and due to its polygenic inheritance it is presumably more durable (Roumen, 1994). Genes controlling QDR have been cloned in several species. Only a few resemble classical Nucleotide-Binding Site Leucine Rich Repeat (NBS-LRR) R-genes; most were previously unidentified genes, with biological functions not formerly associated with disease resistance (reviewed in Roux et al., 2014; Hurni et al., 2015; Debieu et al., 2016). These first insights highlight the diversity of molecular mechanisms triggering QDR which integrates multiple perception pathways, each contributing to the overall resistance phenotype. Better understanding of its cellular and molecular regulation networks is required to develop strategies for long-term broad-spectrum control of plant diseases.

Verticillium wilt disease, caused by soil-borne fungi of the genus Verticillium is a major constraint for production of important crops, such as tomato or cotton (Fradin and Thomma, 2006; Klosterman et al., 2009). After entering the root through wounds or cracks at the site of lateral root emergence, the fungus colonizes the xylem vessels, which, together with gum formation by plant cells, induces vessel clogging and results in the typical wilting symptoms (Agrios, 2004). Due to survival structures viable for many years in the soil and to the protected localization in infected plants, Verticillium wilt is difficult to control. So far the most efficient way is by breeding resistant varieties.

Examples of polygenic and monogenic Verticillium resistance have been described and resistance loci have been identified (e.g., Simko et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008; Yang C. et al., 2008; Häffner et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012; Jakse et al., 2013). Notably the Ve locus in tomato which confers resistance to race 1 of V. dahliae and V. albo-atrum (Fradin and Thomma, 2006) has been characterized in detail. It contains two genes encoding receptor-like proteins with NBS-LRR domains, Ve1 and Ve2, which are each able to confer resistance to susceptible potato (Kawchuk et al., 2001). In Arabidopsis, the tomato Ve1 gene confered resistance to V. dahliae and V. albo-atrum but not to V. longisporum (Fradin et al., 2011). Homologs of the Ve genes have been reported in other species as well (Fradin and Thomma, 2006).

Defense mechanisms against Verticillium spp. and their control by phytohormones and other signaling pathways have been studied in several hosts, such as tomato, cotton, or Arabidopsis (Gayoso et al., 2010; Zhang Y. et al., 2013; Köenig et al., 2014). In most cases, resistant plants are characterized by a rapid increase in phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) activity, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of lignin and phenylpropanoids and in synthesis of salicylic acid (SA), an important signaling compound in resistance (Mauch-Mani and Slusarenko, 1996). Data on the role of most phytohormones in resistance to Verticillium are however contradictory. A given hormone might be linked either to resistance (Hu et al., 2005; Johansson et al., 2006; Fradin et al., 2009, 2011) or to symptom development (Tjamos et al., 2005; Ratzinger et al., 2009; Häffner et al., 2014; Roos et al., 2014), depending on plant species and experimental approaches.

Legume plants have an essential role in sustainable agriculture, due to their symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing rhizobacteria and the high protein content of their seeds. Their roots are thus a site of sometimes simultaneous responses to symbiotic and pathogenic microbes. Verticillium wilt, caused by V. alfalfae (Va), is a serious threat to the forage legume crop alfalfa, notably in Europe. Although tolerant alfalfa cultivars are available, the bases of resistance or tolerance in this autotetraploid and allogamous species are not well-understood (Molinéro-Demilly et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2016). The closely related wild species Medicago truncatula is a model for legume plants and particularly attractive for the study of plant-microbe interactions (Samac and Graham, 2007; Rose, 2008; Young and Udvardi, 2009; Gentzbittel et al., 2015). Knowledge obtained with M. truncatula can be transferred to alfalfa and other legumes. For example, the RCT1 gene responsible for resistance against C. trifolii race 1 in M. truncatula, conferred resistance against several races of the fungus in alfalfa (Yang S. et al., 2008). M. truncatula is also prone to Verticillium wilt and exhibits a high biodiversity in the response to this pathogen (Ben et al., 2013; Negahi et al., 2013). Genetic analyses performed on different crosses revealed that Verticillium wilt response in M. truncatula is a QDR, regulated by QTL that differ across resistant accessions and according to the fungus strains (Ben et al., 2013; Negahi et al., 2014). None of these QTL are co-localized with putative Ve homologs. The highly contrasted phenotypes of resistant line A17 and susceptible F83005.5 as well as the fact that resistance in A17 is controlled by one major QTL makes this couple a good model to explore resistance and defense mechanisms against Verticillium wilt, and more generally to gain knowledge on molecular mechanisms involved in QDR. Hence, these two lines were used to characterize the resistance response by microscopy and a transcriptomics-based approach.

Materials and methods

Plants

M. truncatula A17 and F83005.5 plants were grown in hydroponic culture on Farhaeus medium as described by Ben et al. (2013), with 16 h of light (170 μmol m−2 s−1) at 25°C and 8 h of darkness at 23°C.

Fungal isolates

V. alfalfae V31-2 (formerly V. albo-atrum), its GFP-expressing transformant Va-A1b2 (Ben et al., 2013), V. albo-atrum LPP0323 (provided by A. v. Tiedemann, Germany), and V. dahliae JR2 (provided by B. Thomma, Netherlands) were grown on PDA medium at 24°C in the dark. Spore suspensions were obtained as described in Ben et al. (2013).

Inoculation and symptom scoring

Ten day old plants were inoculated after cutting the root apex by root-dipping in a conidial suspension (106 sp/ml) for 60 min. Then roots were kept in sterile water for 10 min, transferred back to nutritive solution and incubated in a growth chamber at 20°C with 16 h photoperiod. Symptoms were scored on a scale from 0 (healthy) to 4 (dead plant) (Supplementary Figure S1B). Area Under the Disease Progress Curves (AUDPC, Shaner and Finney, 1977) were computed using the “agricolae” package of the R system for statistical computing and graphing (R Core Team, 2012). All data were analyzed with ANOVA using the appropriate model depending on the experimental designs used. When required, data transformations were applied to achieve normality and homoscedasticity of ANOVA residuals. Pairwise treatment differences were determined by a Tukey's test or Newman-Keuls test using the “agricolae” package.

Microscopic observations

M. truncatula roots were rinsed briefly in water and 1 cm fragments were embedded in 5% low melting point agarose. Longitudinal sections of 45 μm were prepared on a vibratom (Leica VT 1000S) and mounted in distilled water. Confocal images were acquired with a spectral confocal laser scanning system (SP2 SE, Leica) equipped with an upright microscope (DM 6000, Leica, Germany). Phenolic compounds were observed using an inverted microscope (Leica DM IRBE, Leica) under UV light. Images were acquired with a CCD camera (Color Coolview; Photonic Science) using an objective with 40 × magnification.

Gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. After treatment with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega) cDNA was synthesized using the ImProm-II™Reverse Transcription System (Promega). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out with standard protocol (see protocol details in Supplementary Figure S4) using 3 μl of cDNA (3 ng/μl).

Data analysis was performed with the SDS 2.3 software (Applied Biosystems). CT-values were normalized against the harmonic mean of four reference genes Medtr2g099090.1, Medtr2g033910.1, Medtr3g085850.1, and TC117750 (encoding Glyoxalase 2, Phosphatase 2C, G3PDH, and H3L, respectively). Primers are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Fold change in gene expression was determined with the ΔΔCT method, using the mock-inoculated condition as the reference (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Transcriptomic analysis by massive analysis of cDNA ends (MACE)

Six roots of Va- and mock-inoculated A17 and F83005.5 plants were harvested at t0, 4, 8, and 24 hpi, and shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Samples from 4, 8, and 24 hpi were equimolarily pooled for mock-inoculated or Va-inoculated plants. Twenty μg RNA were processed for Massive Analysis of cDNA Ends.

MACE was conducted by GenXPro GmbH as described in Behringer et al. (2015). Tag assembly and annotation were conducted by GenXPro GmbH. After sequencing, each 93 nt tag was mapped allowing only 1 mismatch to sequences in databases including M. truncatula genome version 3.5v5 and M. truncatula ESTs of MtGI Release 11.0.

Gene expression profiling

Differential expression analysis was conducted using “edgeR” package of the R/Bioconductor statistical language (Robinson et al., 2010). Reads non-uniquely aligned and in incorrect orientation with respect to genome annotation were discarded. Genes with ≥5 reads were retained.

Normalized read counts were obtained by Trimmed Mean of M-values (TMM) normalization and were modeled by a negative binomial distribution, which allows over-dispersion of counts, and fitted using generalized linear models to test for differential abundances (i) between A17 and F83005.5 “t0” libraries to characterize putative genotype effect on gene expression before inoculation (ii) between mock- and Va-inoculated libraries to detect genes responding to inoculation in each genotype. Biological replicate was fitted as an effect. Differential expression was tested in “tag-wise” mode, where the dispersion is set to the observed dispersion for the transcripts. Logistic regression of the transcript proportions was also used (Collett, 2002). P-values were adjusted to control the false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Construction of co-regulated gene networks using WGCNA and LegumeGRN software

Weighted gene co-expression networks were constructed using the “WGCNA” R package (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008). Transcripts with a coefficient of variation (CV) ≥ 0.35 for normalized read counts across the six libraries from the A17 resistant line were selected. This CV threshold was chosen to include all A17 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) responsive to inoculation in the resulting trimmed dataset. WGCNA was performed using similar settings as in Formey et al. (2014) except a beta power of 20. Eigengene value was calculated for each identified module and used to test for association with different contrasts of biological interest (i.e., “mock-inoculated vs. Va-inoculated roots”) and contrasts accounting for the effect of the biological replicates. The five modules most correlated to inoculation response were visualized using Cytoscape v3.0.1 (Smoot et al., 2011).

Genes from the Greenyellow module possessing Affymetrix probes were analyzed using the legumeGRN gene regulatory network prediction server (http://legumegrn.noble.org/, Wang M. et al., 2013). Unweighted Gene Co-expression Network was predicted using compiled data from the M. truncatula Gene Expression Atlas (MtGea) regarding different pathogenic root interactions. A Pearson's correlation threshold of |0.7| was applied.

In silico functional analyses

GO-term enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) terms were generated using standard settings of Blast2GO (Conesa et al., 2005; http://www.blast2go.com). GO term enrichment analysis was performed with the Singular Enrichment Analysis (SEA) tool of agriGo (Du et al., 2010) using the “complete GO” set, Blast2GO-customized annotation for the test sample and “M. truncatula genome locus v3.5” as background reference. Statistical tests were done with Fisher's exact test and p-values were adjusted with Yekutieli (FDR under dependency) multi-test correction.

MapMan analysis

To create the mapping files necessary to visualize MACE data using MapMan software (Thimm et al., 2004), M. truncatula transcripts were first assigned to their respective MapMan BIN from the existing pathway mapping file for M. truncatula genome v3.5 sequences (Mt_Mt3.5_v3_0411.m02). Remaining genes were annotated using InterProscan 4.8 for accurate annotation then classified manually according to their respective TIGR annotation (TAIR 7.0) on The GABI Primary Database (http://www.gabipd.org/).

Results

Medicago truncatula line A17 eliminates V. alfalfae from roots after initial colonization

A hydroponic culture which allows easy access to roots as described by Ben et al. (2013) was used in this work. After inoculation with V. alfalfae (Va) strain V31-2, the susceptible line F83005.5 developed disease symptoms and aerial fresh biomass was reduced at the end of the experiment, whereas the resistant line A17 was not affected (Supplementary Figure S1). To assess if this difference was correlated to root colonization, both lines were inoculated with Va-A1b2, a GFP-expressing strain, and root sections were observed at different times after inoculation using confocal laser scanning microscopy.

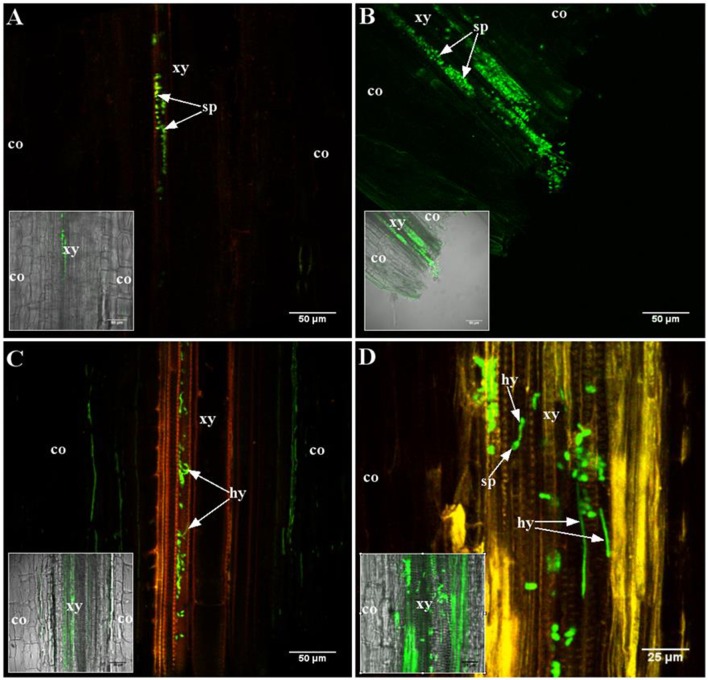

During initial stages of root colonization, no difference between the two genotypes was observed (Figure 1). Conidia were sucked into the xylem vessels at the cut root ends by the transpiration stream, in resistant and susceptible line, as observed 2 h after inoculation (Figures 1A,B). Germination of conidia occurred in both lines, within 24 h (Figures 1C,D). Hyphae developed afterwards and colonized the vessels in both lines similarly (data not shown), as already described for the susceptible line F83005.5 (Ben et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Early stages of root colonization of A17 (resistant) and F83005.5 (susceptible) by a GFP-expressing strain of Va V31-2. Observations were made on 45 μm thick longitudinal root sections embedded in 5% agarose. Confocal images were acquired with a spectral confocal laser scanning system (SP2 SE, Leica, Germany) equipped with an upright microscope (DM 6000, Leica, Germany). Observations were made using 10 × (HC PL Fluotar, N.A. 0.3) and 40 × (HCX PL APO, N.A. 0.8) dry and water immersion objectives, respectively. The 488 nm ray line of an argon laser was used to detect the GFP fluorescence emission collected in the range between 490 and 540 nm. Three plants per line per time point were observed. (A,C) A17 line; (B,D) F83005.5 line. (A,B) 2 h after inoculation, conidia (sp) are observed in the xylem vessels of both lines. (C,D) 24 h after inoculation, conidia are germinating in the xylem vessel of both lines. Co, cortex; hy, hypha; sp, conidia; xy, xylem elements.

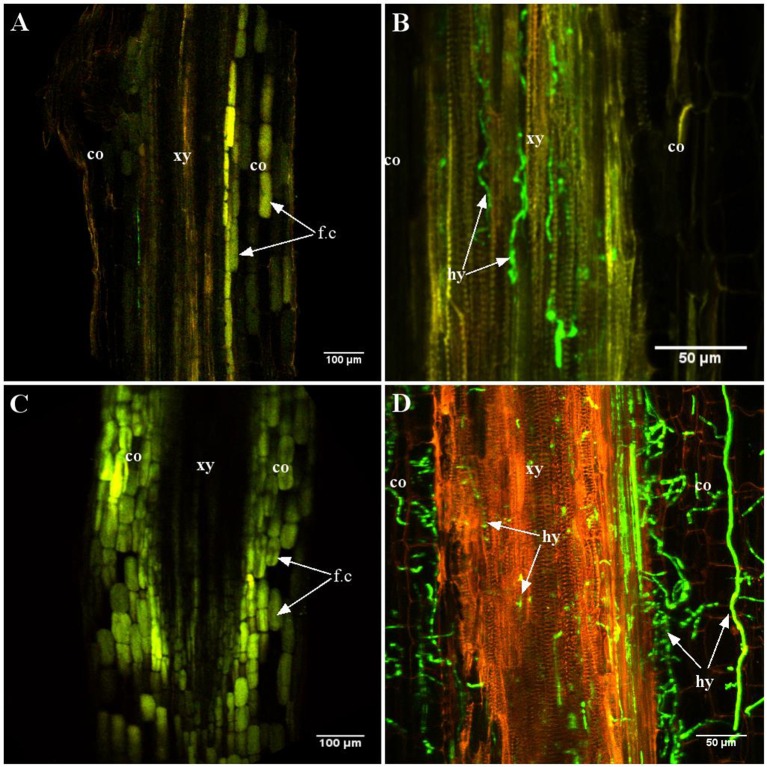

Differences became apparent at intermediate stages [4–7 days post-inoculation (dpi)] (Figure 2). Indeed, at 7 dpi, A17 roots were devoid of Va (Figure 2A) while in roots of the susceptible line, hyphae were abundant in the central cylinder (Figure 2B). Typical for vascular diseases, colonization at this stage was strictly limited to the xylem vessels. At latest stages, the roots of susceptible plants were highly colonized and hyphae were also growing in the cortex (Figure 2D). In contrast, cortical cells of the resistant line showed intensive auto-fluorescence suggesting the accumulation of soluble phenolic compounds (Figures 2A,C; Supplementary Figure S2). Staining with the chitin-binding lectin WGA-FITC did not reveal any hyphae in roots of line A17 at 10 dpi, demonstrating that absence of GFP fluorescence was not due to metabolic inactivity of Va (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Late stages of root colonization of A17 (resistant) and F83005.5 (susceptible) by a GFP-expressing strain of Va V31-2. Observations were made on 45 μm thick longitudinal root sections embedded in 5% agarose. Confocal images were acquired with a spectral confocal laser scanning system (SP2 SE, Leica, Germany) equipped with an upright microscope (DM 6000, Leica, Germany). Observations were made using 10 × (HC PL Fluotar, N.A. 0.3) and 40 × (HCX PL APO, N.A. 0.8) dry and water immersion objectives, respectively. The 488 nm ray line of an argon laser was used to detect the GFP fluorescence emission collected in the range between 490 and 540 nm. Three plants per line per time point were observed. (A,C) line A17; (B,D) line F83005.5. (A,B) 7 days after inoculation, the presence of the pathogen is not observed in the resistant line (A) while hyphae are observed in the xylem vessels of the susceptible line (B). (C,D) 12 days after inoculation, the pathogen is observed only in the susceptible line (D). In roots of the resistant line, numerous cells contain auto-fluorescent compounds (C). co, cortex; hy, hypha; xy, xylem elements; fc, soluble fluorescent compounds.

The disappearance of Va in line A17 as observed by microscopy, was confirmed by quantification of fungal DNA in M. truncatula roots and aerial parts by qPCR using Va-specific primers (Supplementary Figure S4). It can be concluded that the fungus was eliminated from roots of the resistant line A17 plants after initial colonization of the vessels.

V. alfalfae strain V31-2 does not contain avirulence gene Ave1

Strain V31-2, together with strains V. albo-atrum LPP0323 and V. dahliae JR2 used in previous studies (Negahi et al., 2013), was characterized by PCR with species-specific primers (Inderbitzin et al., 2013; Supplementary Figure S5). The results confirmed that the alfalfa isolate V31-2 belongs to the newly formed species V. alfalfae, and incidentally showed that strain LPP0323 belongs to V. nonalfalfae. PCR with Ave1-specific primers (de Jonge et al., 2012) conducted on these 3 strains showed that neither V31-2 nor LPP0323 contained an Ave1 homolog, in contrast to the positive control Vd JR2. In Ve1 tomato, resistance to race 1 V. dahliae and V. albo-atrum is mediated through recognition of the fungal Ave1 gene. The absence of Ave1 in V31-2 suggests that resistance in M. truncatula toward this strain is different from the Ve1-Ave1 interaction described in tomato.

Resistant and susceptible lines exhibit specific transcriptional reprogramming early after inoculation with V. alfalfae

To get more insight into resistance mechanisms which eliminate Va from roots in line A17, a transcriptomic study was undertaken. Based on root colonization pattern, the period between 0 and 24 hpi was considered as decisive, preceding the accumulation of putative defense compounds, and elimination of the pathogen. Two independent experiments with lines A17 and F83005.5 (mock-inoculated, Va-inoculated) exhibiting similar time course of infection were conducted (Supplementary Figure S6). cDNA libraries prepared from RNA extracted from roots at t0 (before inoculation) and from roots at 4, 8, and 24 hpi pooled thereafter (named “Early” pools) were constructed. Between 13 and 29 million reads were obtained for each of the 12 libraries by MACE sequencing (Supplementary Table S2).

Sequence mapping on the M. truncatula genome gave a total number of 58,186 putative genes. This was reduced to less than half when only genes with ≥5 reads in at least two libraries were considered, with 17,978 sequences for A17 and 18,089 for F83005.5. Among them, 1261 genes were differentially expressed between the two lines at t0, with 735 (58%) over-expressed in A17, establishing a strong genotype effect on basal gene expression (Supplementary Table S3). Interestingly, analysis of GO term enrichment showed that functions associated to “response to stimulus” and to secondary metabolism were strongly enriched for the transcripts with higher expression level in resistant line A17. More strikingly, the category “defense response” was only found in this set of differentially expressed genes (DEGs; Table 1). Line F83005.5 exhibited higher expression of genes involved in primary metabolism, and in categories “biological regulation and signaling,” “localization,” “cellular component organization and process,” and “developmental process.” These strong and large differences in gene expression before inoculation suggest that the resistant line might possess preformed defenses or might be better prepared to induce a fast and efficient response.

Table 1.

Enriched Gene Ontology (GO) categories of differentially expressed genes in M. truncatula lines A17 and F83005.5 before Verticillium inoculation (i.e., at t0).

| GO ID | GO term definition | O | U | FDR O | FDR U |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| METABOLIC PROCESS | |||||

| GO:0006006 | Glucose metabolic process | ns | 0.00016 | ||

| GO:0006081 | Cellular aldehyde metabolic process | ns | 0.0018 | ||

| GO:0044275 | Cellular carbohydrate catabolic process | ns | 0.0076 | ||

| GO:0042398 | Cellular amino acid derivative biosynthetic process | 2.7e-13 | 0.00075 | ||

| GO:0000097 | Sulfur amino acid biosynthetic process | ns | 0.00013 | ||

| GO:0009065 | Glutamine family amino acid catabolic process | ns | 0.00031 | ||

| GO:0009084 | Glutamine family amino acid biosynthetic process | ns | 0.0071 | ||

| GO:0009081 | Branched chain family amino acid metabolic process | ns | 0.0079 | ||

| GO:0009095 | Aromatic amino acid family biosynthetic process, prephenate pathway | 0.0048 | ns | ||

| GO:0032787 | Monocarboxylic acid metabolic process | 2e-06 | 1.8e-12 | ||

| GO:0046395 | Carboxylic acid catabolic process | 0.00061 | 0.0017 | ||

| GO:0006099 | Tricarboxylic acid cycle | ns | 0.0036 | ||

| GO:0006631 | Fatty acid metabolic process | ns | 0.0021 | ||

| GO:0006184 | GTP catabolic process | ns | 0.009 | ||

| GO:0019748 | Secondary metabolic process | 9.4e-18 | 2.7e-05 | ||

| GO:0019438 | Aromatic compound biosynthetic process | 4.7e-21 | 0.00026 | ||

| GO:0018130 | Heterocycle biosynthetic process | ns | 0.0027 | ||

| GO:0055114 | oxidation reduction | 7.2e-05 | ns | ||

| GO:0006032 | Chitin catabolic process | 0.009 | ns | ||

| GO:0046165 | Alcohol biosynthetic process | ns | 5.8e-06 | ||

| GO:0009108 | Coenzyme biosynthetic process | ns | 0.0056 | ||

| RESPONSE TO STIMULUS | |||||

| GO:0009607 | Response to biotic stimulus | 1.4e-29 | 2.4e-06 | ||

| GO:0006952 | Defense response | 1.6e-13 | ns | ||

| GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 7.4e-08 | 1.1e-23 | ||

| GO:0009416 | Response to light stimulus | 7.4e-08 | ns | ||

| GO:0006979 | Response to oxidative stress | 2.5e-05 | 0.0019 | ||

| GO:0010038 | Response to metal ion | 0.00014 | 3.1e-07 | ||

| GO:0009605 | Response to external stimulus | 0.00028 | ns | ||

| GO:0009725 | Response to hormone stimulus | ns | 1.9e-10 | ||

| GO:0009415 | Response to water | ns | 0.0023 | ||

| GO:0051716 | Cellular response to stimulus | ns | 0.0036 | ||

| BIOLOGICAL REGULATION, SIGNALING | |||||

| GO:0043086 | Negative regulation of catalytic activity | 0.0011 | ns | ||

| GO:0048523 | Negative regulation of cellular process | ns | 0.0036 | ||

| GO:0044092 | Negative regulation of molecular function | 0.0011 | 0.0075 | ||

| GO:0010557 | Positive regulation of macromolecule biosynthetic process | ns | 0.00085 | ||

| GO:0031328 | Positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic process | ns | 5.8e-06 | ||

| GO:0032268 | Regulation of cellular protein metabolic process | ns | 0.0023 | ||

| GO:0007242 | Intracellular signaling cascade | ns | 0.0095 | ||

| GO:0032259 | Methylation | 0.0041 | 1.3e-06 | ||

| GO:0001510 | RNA methylation | ns | 0.00038 | ||

| GO:0006412 | Translation | ns | 5e-09 | ||

| LOCALIZATION AND TRANSPORT | |||||

| GO:0006605 | Protein targeting | 0.00069 | 1.1e-06 | ||

| GO:0006839 | Mitochondrial transport | ns | 0.0025 | ||

| DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESS | |||||

| GO:0048869 | Cellular developmental process | ns | 2.6e-05 | ||

| GO:0007275 | Multicellular organismal development | ns | 0.0045 | ||

| CELLULAR PROCESS | |||||

| GO:0044085 | Cellular component biogenesis | ns | 0.00026 | ||

| GO:0051128 | Regulation of cellular component organization | ns | 0.0013 | ||

| GO:0051276 | Chromosome organization | ns | 0.0065 | ||

| GO:0034621 | Cellular macromolecular complex subunit organization | ns | 0.0036 | ||

| OTHER | |||||

| GO:0009405 | Pathogenesis | 0.00094 | ns | ||

| GO:0022414 | Reproductive process | ns | 0.0033 | ||

340 (46%) over-expressed and 484 (92%) under-expressed genes in line A17 compared to line F83005.5 at t0 were annotated with GO terms using BLAST2GO, respectively. Over-represented GO terms for biological process (adjusted P = 0.01) were identified using agriGO. To clarify the overview, only the significantly enriched GO terms of deeper level in the hierarchical tree graph are mentioned herein and labeled by their GO ID, term definition and statistical information. The degree of color saturation is positively correlated to the enrichment level of the term. O, Over-expressed genes in A17 compared to F83005.5; U, Under-expressed genes in A17 compared to F83005.5; FDR, FDR under dependency computed with the Yekutieli's multi-test correction method; ns, not significantly enriched.

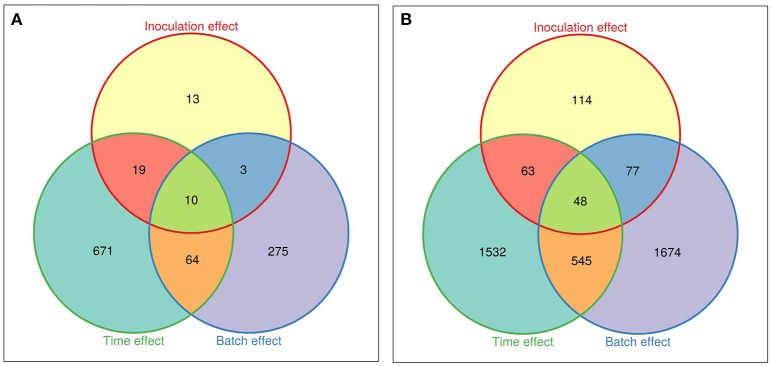

Due to the strong genotype effect, independent data analyses were performed for each M. truncatula line. Three groups of DEGs were distinguished, corresponding to genes regulated by time/development (Early-Mock vs. t0), by inoculation (Early-inoculated vs. Early-Mock), or by experimental batch factors (Experiment 1 vs. Experiment 2; Figures 3A,B). In total, 1055 and 4053 DEGs were identified in A17 and F83005.5, respectively, evidencing a stronger transcriptional response in the susceptible line, although colonization at this stage was still very low and not much different from that in the resistant line (Figure 1). Among the 45 DEGs responding to inoculation in the resistant line A17 (0.3% of the 17,978 genes), 13 responded specifically to Va, 29 responded also to development; most genes (72%) were induced (Supplementary Table S4). Among the 302 DEGs responsive to inoculation in the susceptible line F83005.5 1.7% of the 18,089 genes), 114 (37.7%) responded specifically to Va and 111 (36.7%) responded also to development; here, up- and down-regulated genes accounted each for roughly half (45 and 55%) of the DEGs (Supplementary Table S5). The gene expression profiles revealed by MACE were validated by qRT-PCR for 24 DEGs which appeared up- or down-regulated in inoculated A17 and/or F83005.5 (Supplementary Table S6). Gene expression levels were highly similar with both methods (Pearson's correlation coefficient, r = 0.86) supporting the reliability of MACE results.

Figure 3.

Venn diagrams of the differentially expressed genes in roots of M. truncatula lines. (A) Differentially expressed genes in the resistant line A17. (B) Differentially expressed genes in the susceptible line F83005.5. “Inoculation effect” represents the comparison between Va-inoculated and mock-inoculated samples, “Time effect” shows the comparison of mock-inoculated at t0 and in pool early, and “Batch effect” corresponds to a comparison between the two experiments (biological repeats). A gene is differentially expressed if the False Discovery Rate (FDR) is <0.05. Venn diagrams were generated with the Vennerable R package (http://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/vennerable).

Twenty DEGs showed similar expression patterns in both lines. Nineteen were functionally annotated, including genes involved in secondary metabolism, oxidation-reduction process, response to stress, and regulation of cellular process (Table 2). Both A17 and F83005.5 showed increased expression of three chalcone synthase genes after inoculation with Va, but induction was stronger in line A17.

Table 2.

Genes responding similarly to inoculation in the resistant (A17) and susceptible (F83005.5) M. truncatula lines.

| ID Mt v3.5 | ID Mt v4 | Annotation | FC A17 | FC F83005.5 | Biological process GO terms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UP-REGULATED GENES | |||||

| Contig_64564_1.1 | Medtr7g103390.1 | Myb sant-like dna-binding domain protein | 7,3 | 4,5 | Regulation of cellular process |

| Medtr7g086320.1 | Medtr7g086320.1 | Hypothetical protein MTR_7g086320 | 5,8 | 5,6 | – |

| Medtr5g022390.1 | Medtr5g022380.1 | Rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase | 4,7 | 2,7 | Transferase activity |

| Medtr1g097910.1 | Medtr1g097910.1 | Chalcone synthase | 4,3 | 1,7 | Flavonoid biosynthetic process |

| TC187179 | Medtr3g089940.2 | Alcohol dehydrogenase | 4,2 | 2,3 | Oxidation-reduction process |

| Contig_240964_1.1 | Medtr2g089835.1 | Wound-responsive family protein | 3,9 | 4,7 | – |

| Medtr1g098140.1 | Medtr1g098140.1 | Chalcone synthase | 3,7 | 1,9 | Flavonoid biosynthetic process |

| Medtr1g083950.1 | Medtr1g083950.1 | Universal stress protein a-like protein | 3,6 | 2,7 | – |

| TC194155 | Medtr1g097935.1 | Chalcone synthase | 3,2 | 2,0 | Flavonoid biosynthetic process |

| Medtr7g055630.1 | Medtr7g055630.1 | Ankyrin repeat protein | 2,7 | 1,7 | – |

| Medtr5g022380.1 | Medtr5g018720.1 | nodulin family protein | 2,5 | 3,0 | Response to karrikin |

| TC196800 | Medtr2g016650.1 | Hypothetical protein | 2,4 | 2,3 | Anaerobic respiration |

| Contig_7825 | – | – | 2,4 | 2,4 | – |

| DOWN-REGULATED GENES | |||||

| Medtr8g078170.1 | Medtr8g078170.1 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein | −2,3 | −1,6 | – |

| Medtr8g022300.1 | Medtr8g022300.1 | Dormancy auxin associated protein | −2,6 | −2,5 | – |

| Contig_167649_1.1 | Medtr3g088845.1 | 2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase subunit alpha | −2,7 | −4,9 | Oxidation-reduction process |

| Medtr2g096120.1 | Medtr2g082050.1 | Uncharacterized loc101218723 | −2,7 | −3,6 | – |

| TC176640 | Medtr1g083440.1 | Dormancy auxin associated protein | −3,8 | −3,4 | Response to brassinosteroid stimulus |

| TC191486 | Medtr1g029500.1 | f-box protein skp2a | −4,1 | −4,1 | – |

| Contig_70372_1.1 | Medtr8g012795.1 | Defensin-like protein | −5,4 | −3,5 | Response to stress |

ID Mt v3.5 and ID Mt v4 correspond, respectively to gene IDs in versions v3.5 and v4 of M. truncatula genome. FC A17 (respectively, FC F83005.5) values correspond to log2 of the ratio [mean of normalized counts in Va-inoculated condition/ mean of normalized counts in control condition]; Va, Verticillium alfalfae.

In silico functional analysis indicates induction of a targeted defense response in the resistant line

To get further insights into the biological pathways involved in the response to Va infection, GO term enrichment analyses were performed for the DEGs responding to fungal inoculation in each line. Regarding line A17, all significantly enriched functional categories contained only up-regulated DEGs and concerned a limited number of biological processes (Table 3). The category “response to stimulus” included notably “response to biotic stimulus,” “defense response,” and “response to organic substance,” and the category “metabolic process” included “aromatic compound,” “amino acid derivative,” and “secondary metabolism.” This picture suggests a targeted and organized biological response of the resistant line early after pathogen inoculation. In contrast, the response to Va in the susceptible line F83005.5 appeared more complex and disordered. Processes related to “response to stimulus” as well as “metabolism process” including very diverse biological pathways were highly affected (Table 4). Among those, single functional categories such as “cellular catabolic process” or “response to biotic stimulus” were both significantly induced and repressed. A majority of cellular pathways such as “response to oxidative stress” and “response to hormone stimuli” appeared to be down-regulated, and all genes of the category “biological regulation,” among them notably “ion homeostasis” were consistently repressed. Strikingly, the GO term associated with “defense response” was not significantly enriched in the susceptible line.

Table 3.

Comparison of enriched GO terms in up- and down-regulated genes in the resistant line A17 in response to V. alfalfae inoculation.

| GO ID | GO term definition | U | D | FDR U | FDR D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| METABOLIC PROCESS | |||||

| GO:0019438 | Aromatic compound biosynthetic process | 0.0012 | ns | ||

| GO:0042398 | Cellular amino acid derivative biosynthetic process | 0.0012 | ns | ||

| GO:0019748 | Secondary metabolic process | 0.0012 | ns | ||

| RESPONSE TO STIMULUS | |||||

| GO:0009607 | Response to biotic stimulus | 0.0012 | ns | ||

| GO:0006952 | Defense response | 0.025 | ns | ||

| GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 0.027 | ns | ||

20 (61%) up-regulated and 6 (50%) down-regulated genes in response to V. alfalfae in line A17 compared to control condition were annotated with GO terms using BLAST2GO, respectively. Over-represented GO terms for biological process (adjusted P = 0.05) were identified using agriGO. To clarify the overview, only the significantly enriched GO terms of deeper level in the hierarchical tree graph are mentioned herein and labeled by their GO ID, term definition and statistical information. The degree of color saturation is positively correlated to the enrichment level of the term. U, Up-regulated genes in Va-inoculated condition compared to control; D, Down-regulated genes in Va-inoculated condition compared to control; FDR, FDR under dependency computed with the Yekutieli's multi-test correction method; ns, not significantly enriched; Va, Verticillium alfalfae.

Table 4.

Comparison of enriched GO terms in up- and down-regulated genes in the susceptible line F83005.5 in response to V. alfalfae inoculation.

| GO ID | GO term definition | U | D | FDR U | FDR D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| METABOLIC PROCESS | |||||

| GO:0005985 | Sucrose metabolic process | 0.003 | ns | ||

| GO:0006012 | Galactose metabolic process | ns | 0.022 | ||

| GO:0019319 | Hexose biosynthetic process | ns | 0.022 | ||

| GO:0006081 | Cellular aldehyde metabolic process | 0.047 | 0.003 | ||

| GO:0006090 | Pyruvate metabolic process | ns | 0.022 | ||

| GO:0042398 | Cellular amino acid derivative biosynthetic process | 1.2e-09 | ns | ||

| GO:0009063 | Cellular amino acid catabolic process | ns | 0.0041 | ||

| GO:0006551 | Leucine metabolic process | ns | 0.0094 | ||

| GO:0006558 | L-phenylalanine metabolic process | 0.016 | ns | ||

| GO:0008654 | Phospholipid biosynthetic process | ns | 0.024 | ||

| GO:0009247 | Glycolipid biosynthetic process | ns | 0.027 | ||

| GO:0019748 | Secondary metabolic process | 9.5e-11 | ns | ||

| GO:0019438 | Aromatic compound biosynthetic process | 2.2e-09 | ns | ||

| GO:0032787 | Monocarboxylic acid metabolic process | 0.0085 | ns | ||

| GO:0046700 | Heterocycle catabolic process | ns | 0.013 | ||

| GO:0016117 | Carotenoid biosynthetic process | ns | 0.032 | ||

| GO:0006800 | Oxygen and reactive oxygen species metabolic process | 4.4e-06 | ns | ||

| GO:0015979 | Photosynthesis | ns | 0.036 | ||

| GO:0015994 | Chlorophyll metabolic process | ns | 0.00009 | ||

| GO:0044248 | Cellular catabolic process | 0.0087 | 0.00018 | ||

| GO:0051187 | Cofactor catabolic process | ns | 0.0012 | ||

| RESPONSE TO STIMULUS | |||||

| GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 0.00004 | 3.1e-21 | ||

| GO:0009607 | Response to biotic stimulus | 4.9e-05 | 0.00027 | ||

| GO:0009719 | Response to endogenous stimulus | 0.017 | 5.7e-07 | ||

| GO:0009725 | Response to hormone stimulus | ns | 5.7e-07 | ||

| GO:0010035 | Response to inorganic substance | ns | 0.0041 | ||

| GO:0006979 | Response to oxidative stress | ns | 0.029 | ||

| GO:0009267 | Cellular response to starvation | ns | 0.022 | ||

| GO:0009415 | Response to water | ns | 0.019 | ||

| BIOLOGICAL REGULATION, SIGNALING, AND LOCALIZATION | |||||

| GO:0006826 | Iron ion transport | ns | 0.00071 | ||

| GO:0006879 | Cellular iron ion homeostasis | ns | 0.00092 | ||

| GO:0048519 | Negative regulation of biological process | 0.00065 | 0.0012 | ||

| GO:0045892 | Negative regulation of transcription DNA-dependent | ns | 0.019 | ||

| GO:0023033 | Signaling pathway | ns | 0.02 | ||

70 (52%) up-regulated and 112 (67%) down-regulated genes in response to V. alfalfae in F83005.5 line compared to control condition were annotated with GO terms using BLAST2GO, respectively. Over-represented GO terms for biological process (adjusted P = 0.05) were identified using agriGO. To clarify the overview, only the significantly enriched GO terms of deeper level in the hierarchical tree graph are mentioned herein and labeled by their GO ID, term definition, and statistical information. The degree of color saturation is positively correlated to the enrichment level of the term. U, Up-regulated genes in Va-inoculated condition compared to control; D, Down-regulated genes in Va-inoculated condition compared to control; FDR, FDR under dependency computed with the Yekutieli's multi-test correction method; ns, not significantly enriched; Va, Verticillium alfalfae.

To get a more focused vision into specific cellular processes, we overlaid DEGs responding to Va inoculation onto metabolic networks related to biotic stress response using MapMan (Usadel et al., 2005; Supplementary Figure S7). The response of the resistant line A17 was characterized by induction of a few metabolic pathways putatively involved in pathogenic interactions. In particular “plant secondary metabolism” accounted for eight of the significantly induced genes in A17 (Supplementary Figure S7A), with genes involved in metabolism of lignins and lignans, phenylpropanoids, and flavonoids (including chalcones and isoflavonoids; Supplementary Figure S8A). Genes involved in secondary metabolic process were induced in the susceptible line as well, but with lower expression levels (Supplementary Figure S8B). In addition, many cellular functions were modified (induced and/or repressed) in line F83005.5 in response to Verticillium, including genes participating to cell wall and proteolysis, to defense (mostly PR proteins), to oxidative stress, signaling, and transcription factors. Notably, expression of genes involved in phytohormone signaling was strongly affected in this line: genes related to ethylene (ET), jasmonate (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), and auxin signaling were induced whereas genes of salicylic acid (SA) signaling were repressed (Supplementary Figure S7B).

Experiments where plants were pre-treated with ET, MeJA, ABA, auxin, and SA showed that ABA, SA, and auxin protected against symptoms and fungal colonization and ET delayed disease symptoms whereas MeJA had no effect (Supplementary Figures S9, S10). None of these hormones had a direct effect on the fungus (Supplementary Table S7). Hence, the induction of these genes in line F83005.5 does not seem sufficient to fully trigger defenses regulated by the respective hormone signaling pathways.

Incidentally “Response to abiotic stress” showed a similar contrasted pattern in the two lines: induction of genes in A17 and simultaneous induction and repression of genes in F83005.5.

On the whole, GO enrichment and MapMan analyses suggest a structured molecular response in the resistant line A17 leading to the onset of defense mechanisms early after Va inoculation. In contrast, the susceptible line F83005.5 suffered a complete transcriptional dysregulation of plant metabolism and defense pathways which probably favors disease development.

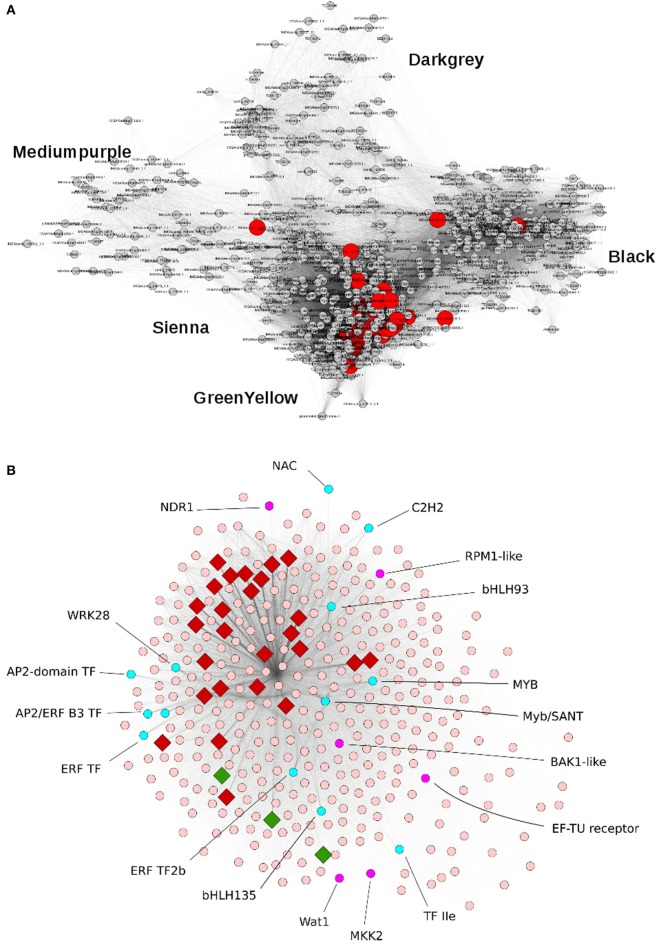

Gene co-expression network analysis identifies five functional modules and transcriptional factors underlying resistance against V. alfalfae

We further investigated the transcriptome organization in resistant line A17 by applying weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) to 2083 sequences exhibiting a coefficient of variation of at least 0.35 across the six libraries (t0, Early-Mock, Early-inoculated, two repetitions). This dataset comprised all 45 inoculation-responsive DEGs identified above. Complementary to the analyses described above which considered only DEGs with a FDR of <0.05, this approach will further reveal subtle effects and show the degree of relationship between genes expression patterns by nodes distance in the graphical presentation. We identified five modules associated to inoculation response which gathered 794 genes (35 to 369 genes per module; Figure 4A, Table 5). This structure points out a coordinated transcriptional response in the incompatible interaction between M. truncatula and V. alfalfae. In contrast, WGCNA on data from line F83005.5 provided only a blurred picture without any distinct co-expression module, suggesting the absence of a structured transcriptional regulation in the susceptible line after inoculation (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Principal modules of the gene co-expression network associated to inoculation response in the resistant M. truncatula line A17. (A) Representation of the Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network of 794 genes in the resistant line A17. Five modules can be distinguished and are named by color codes. Module Greenyellow contains 369 genes, Black 243 genes, Darkgray 82 genes, Mediumpurple 65 genes, and Sienna 35 genes. Genes differentially expressed after Va V31-2 inoculation are shown in red. (B) Representation of co-expression module Greenyellow which contains 369 genes. A rhombus indicates that the gene is differentially expressed after Va V31-2 inoculation. In red: induced genes, in green: repressed genes, in cyan: transcription factors.

Table 5.

GO term functional enrichment analysis of the five WGCNA regulatory modules associated with M. truncatula root response to V. alfalfae inoculation.

| Module | Number of transcripts | GO ID | GO term definition | FDR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenyellow | 369 | Metabolism | |||

| GO:0005985 | Sucrose metabolic process | 9.6e-06 | |||

| GO:0000272 | Polysaccharide catabolic process | 4.2e-05 | |||

| GO:0006096 | Glycolysis | 0.00057 | |||

| GO:0042398 | Cellular amino acid derivative biosynthetic process | 3.3e-19 | |||

| GO:0009081 | Branched chain family amino acid metabolic process | 3.5e-08 | |||

| GO:0009063 | Cellular amino acid catabolic process | 0.0001 | |||

| GO:0006555 | Methionine metabolic process | 0.00019 | |||

| GO:0032787 | Monocarboxylic acid metabolic process | 0.0071 | |||

| GO:0019748 | Secondary metabolic process | 4.3e-23 | |||

| GO:0019438 | Aromatic compound biosynthetic process | 4e-17 | |||

| GO:0055114 | Oxidation reduction | 8.2e-14 | |||

| Response to Stimulus | |||||

| GO:0009607 | Response to biotic stimulus | 7.1e-25 | |||

| GO:0006952 | Defense response | 2.7e-07 | |||

| GO:0009725 | Response to hormone stimulus | 9.3e-09 | |||

| GO:0009416 | Response to light stimulus | 2e-06 | |||

| GO:0010038 | Response to metal ion | 5e-06 | |||

| GO:0051716 | Cellular response to stimulus | 1.7e-05 | |||

| Biological Regulation, Signaling | |||||

| GO:0032259 | Methylation | 1.5e-07 | |||

| GO:0065008 | Regulation of biological quality | 2e-06 | |||

| GO:0043086 | Negative regulation of catalytic activity | 0.0041 | |||

| GO:0048523 | Negative regulation of cellular process | 0.0042 | |||

| GO:0007242 | Intracellular signaling cascade | 0.0035 | |||

| Localization and Transport | |||||

| GO:0006605 | Protein targeting | 0.00024 | |||

| GO:0008643 | Carbohydrate transport | 0.00019 | |||

| GO:0015671 | Oxygen transport | 0.0017 | |||

| GO:0006865 | Amino acid transport | 0.0031 | |||

| Developmental, Cellular, and Reproductive Process | |||||

| GO:0007275 | Multicellular organismal development | 7.8e-06 | |||

| GO:0051704 | Multi-organism process | 5.2e-05 | |||

| GO:0071554 | Cell wall organization or biogenesis | 0.0039 | |||

| GO:0032989 | Cellular component morphogenesis | 0.0093 | |||

| GO:0000003 | Reproduction | 0.0028 | |||

| Black | 243 | Metabolism | |||

| GO:0006730 | One-carbon metabolic process | 0.004 | |||

| GO:0044275 | Cellular carbohydrate catabolic process | 0.0051 | |||

| GO:0006066 | Alcohol metabolic process | 0.0026 | |||

| GO:0022904 | Respiratory electron transport chain | 0.0061 | |||

| Response to Stimulus | |||||

| GO:0006950 | Response to stress | 1.8e-06 | |||

| GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 1.5e-05 | |||

| Biological Regulation, Signaling | |||||

| GO:0048523 | Negative regulation of cellular process | 0.0003 | |||

| Localization and Transport | |||||

| GO:0006810 | Transport | 0.0051 | |||

| Developmental, Cellular and Reproductive Process | |||||

| GO:0016043 | Cellular component organization | 0.0026 | |||

| Darkgray | 82 | Metabolism | |||

| GO:0009207 | Purine ribonucleoside triphosphate catabolic process | 7.4e-05 | |||

| GO:0009231 | Riboflavin biosynthetic process | 0.00041 | |||

| GO:0019748 | Secondary metabolic process | 0.0082 | |||

| GO:0019438 | Aromatic compound biosynthetic process | 0.0095 | |||

| GO:0046034 | ATP metabolic process | 0.0043 | |||

| Response to Stimulus | |||||

| GO:0010035 | Response to inorganic substance | 0.0008 | |||

| Localization and Transport | |||||

| GO:0006812 | Cation transport | 0.002 | |||

| Mediumpurple | 65 | Metabolism | |||

| GO:0005975 | Carbohydrate metabolic process | 0.0013 | |||

| GO:0015979 | Photosynthesis | 0.0074 | |||

| GO:0019344 | Cysteine biosynthetic process | 0.0074 | |||

| GO:0006364 | rRNA processing | 0.0074 | |||

| Response to Stimulus | |||||

| GO:0009416 | Response to light stimulus | 3.3e-05 | |||

| GO:0006950 | Response to stress | 0.0059 | |||

| Biological Regulation, Signaling | |||||

| GO:0048519 | negative regulation of biological process | 0.00084 | |||

| Developmental, Cellular, and Reproductive Process | |||||

| GO:0061024 | Membrane organization | 0.0059 | |||

| Other | |||||

| GO:0009405 | Pathogenesis | 0.0072 | |||

| Sienna | 35 | Metabolism | |||

| GO:0006081 | Cellular aldehyde metabolic process | 0.0064 | |||

| GO:0006090 | Pyruvate metabolic process | 0.0045 | |||

| GO:0015995 | Chlorophyll biosynthetic process | 0.0059 | |||

| GO:0006546 | Glycine catabolic process | 0.0045 | |||

| GO:0019344 | Cysteine biosynthetic process | 0.0045 | |||

| GO:0009117 | Nucleotide metabolic process | 0.0063 | |||

| GO:0019438 | Aromatic compound biosynthetic process | 0.0045 | |||

| GO:0016117 | Carotenoid biosynthetic process | 0.0059 | |||

| GO:0006733 | Oxidoreduction coenzyme metabolic process | 0.0045 | |||

| GO:0006364 | rRNA processing | 0.0045 | |||

| Response to Stimulus | |||||

| GO:0009416 | Response to light stimulus | 0.0045 | |||

| GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 0.0045 | |||

| GO:0010035 | Response to inorganic substance | 0.0082 | |||

| Biological Regulation, Signaling | |||||

| GO:0045893 | Positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | 0.0045 | |||

| Localization and Transport | |||||

| GO:0015931 | Nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid transport | 0.0045 | |||

221 (60%) transcripts from Greenyellow module, 146 (60%) from Black module, 55 (68%) from Darkgray module, 48 (74%) from Mediumpurple module, and 28 (80%) from Sienna module were annotated with GO terms using BLAST2GO, respectively. Over-represented GO terms for biological process (adjusted P ≤ 0.01) were identified using agriGO. To clarify the overview, only the significantly enriched GO terms of deeper level in the hierarchical tree graph are mentioned herein and labeled by their GO ID, term definition and statistical information. The degree of color saturation is positively correlated to the enrichment level of the term. FDR: FDR under dependency computed with the Yekutieli's multi-test correction method; ns: not significantly enriched; WGCNA: Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis.

Statistical analysis of GO term enrichment revealed distinct functional assignments for the different co-expression modules (Table 5). Biological processes involved in response to various biotic and abiotic stimuli were significantly over-represented in all modules, and three of them (Greenyellow, Black, and Darkgray) appeared to be related to specific regulatory pathways such as “negative regulation of biological process” or to different metabolic activities, with some involved in defense against pathogens (e.g., “secondary metabolic process”).

The Greenyellow module is highly enriched in biological functions related to plant defense and encompasses genes exhibiting expression profiles the most correlated to inoculation response. Notably, it contains 29 (64%) of the previously identified DEGs responding to Va inoculation in line A17, together with non-differentially expressed genes (Figure 4B). Hence it appeared to be of major importance for resistance against Va. Detailed examination of this resistance-associated module led to the identification of genes known to play key roles in plant-pathogen interactions, such as genes involved in plant defense (e.g., encoding chitinases, disease resistance RPM1-like proteins, pathogenesis-related protein PR10 or PR5-like receptor kinase (PRK5), LRR protein, …), in ROS metabolism (e.g., peroxidases…), and in secondary metabolism (e.g., PAL, chalcone synthases,…; Supplementary Table S8). Phytohormone-responsive genes, most of them related to ET, ABA, and auxin signaling, are also present in this module, together with genes encoding receptor-like kinases and protein kinases and 21 putative transcription factors (TFs) from different gene families (namely, AP2/ERF and B3, ethylene responsive, MYB and MYB/SANT, NAC, bHLH, WRKY, TIFY, LOB, Trihelix family protein, and C2H2-type zinc finger protein families). Homologs of several genes involved in PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) were identified, such as BAK1 (FM886833.1), MKK2 (Medtr1g113960.1), EF-Tu Receptor (EFR, Medtr5g026090.1), NDR1 (contig_99115_1.1), and Wat1 (walls are thin 1; Medtr3g072500). A KEGG analysis revealed the presence of additional homologs of genes related to PTI, namely CNGC10 (cyclic nucleotide gated channel 10), HSP90 (heat shock protein 90), and CERK1 (chitin elicitor receptor kinase 1). These genes may play a crucial role in the perception of Va and in signal transduction in M. truncatula roots as well as in the subsequent transcriptional regulation leading to resistance.

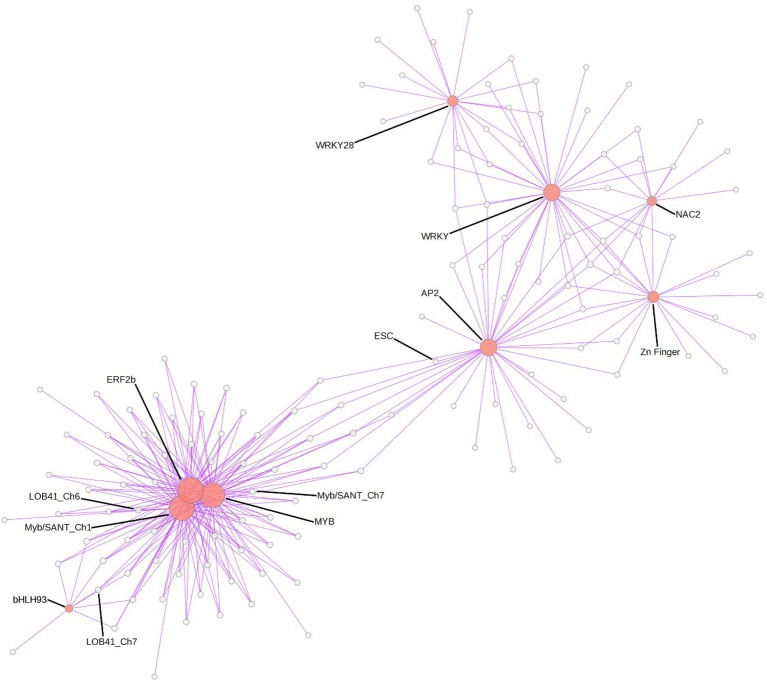

Finally, to address the question if the Greenyellow co-regulatory module was specific for M. truncatula resistance toward Verticillium or potentially involved in the response to other root pathogens, we used the LegumeGRN prediction server (Wang M. et al., 2013). An in silico analysis of co-expression patterns of the 333 (90%) genes from the Greenyellow module which possess Affymetrix probes on transcriptional data of M. truncatula roots inoculated with Aphanomyces euteiches, Macrophomina phaseolina, Phymatotrichopsis omnivore, and Ralstonia solanacearum led us to identify a stringent co-expression network gathering 186 genes (Figure 5). This highlights a substantial level of conservation in the transcriptional response of M. truncatula toward various root pathogens. Indeed, a high proportion (56%) of the genes with Affymetrix probes from the Greenyellow module are also co-regulated in response to other root pathogens (either fungi, bacteria, or oomycetes). A core of 15 TFs holds central positions within this co-regulatory module. Hence, not only defense mechanisms but also important regulators of gene expression are conserved among the responses of M. truncatula to different root pathogens.

Figure 5.

Gene co-expression network in response to various root pathogens predicted using LegumeGRN. Affymetrix probes of the Greenyellow module genes were identified by BLAST Search on Medicago truncatula Gene Expression Atlas. At least one probe was identified for 333 (/369) genes. A predicted co-expression network for 186 genes (http://legumegrn.noble.org/) using a stringent Pearson correlation threshold (Pearson correlation coefficient >±0.8) was identified according to the Medicago truncatula Gene Expression Atlas expression data of A17 roots inoculated with Aphanomyces euteiches, Ralstonia solanacearum, Phymatotrichopsis omnivore, and Macrophomina phaseolina. AP2 (AP2 domain class transcription factor, Mtr.42129.1.S1_at), bHLH93 (Transcription factor bHLH93; Mtr.44005.1.S1_at), ERF2b (Ethylene responsive transcription factor 2b; Mtr.43313.1.S1_at), ESC (DNA-binding protein escarola-like; Mtr.41053.1.S1_at), LOB41_Ch6 and LOB41_Ch7 (LOB domain-containing protein 41-like; Mtr.50046.1.S1_at and Mtr.40344.1.S1_at, respectively), MYB (MYB-like transcription factor family protein; Mtr.22332.1.S1_at), Myb/SANT_Ch1 and Myb/SANT_Ch7 (Myb/SANT-like DNA-binding domain protein; Mtr.32196.1.S1_at and Mtr.11595.1.S1_at, respectively); NAC2 (NAC domain-containing protein 2-like; Mtr.37370.1.S1_at), WRKY (WRKY family transcription factor; Mtr.44416.1.S1_at) and WRKY28 (probable WRKY transcription factor 28-like; Mtr.38202.1.S1_at), Zn Finger (zinc finger protein zat11-like; Mtr.41238.1.S1_at).

Discussion

An undescribed root resistance against Verticillium wilt in M. truncatula

The response against V. alfalfae in resistant M. truncatula is different from the well-characterized Ve1 dependent resistance against V. dahliae and V. albo-atrum in host plants such as tomato, cotton, or Solanum torvum (Fradin et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). Homologs of Ve1 were detected in the M. truncatula genome but were not localized under the resistance QTLs against Va V31-2 (Ben et al., 2013) and are not expressed at important early stages of the interaction, since they were not detected in our MACE libraries. Ve1 recognizes Ave1, the Verticillium effector of race1 strains (Fradin et al., 2011). Ave1 homologs were found in three fungal and many plant species; the Fusarium and Cercospora homologs were both recognized by tomato Ve1, supporting the hypothesis that Ve1—Ave1 mediated resistance had traits of PAMP-triggered immunity (de Jonge et al., 2012). Va strain V31-2 does not possess Ave1 homologs although they were reported in the alfalfa strain VaMS102 (de Jonge et al., 2012).

The study of root colonization showed that after initial colonization of the stele, the fungus was eliminated from roots of the resistant line A17. In other plants, resistance takes place in the shoot. V. dahliae and V. longisporum were shown to infect roots of resistant and susceptible hosts but resistant hosts inhibited pathogen development in the shoot (Heinz et al., 1998; Eynck et al., 2009; Zhang W. W. et al., 2013). The destruction of the fungus by the plant, and the absence of both Ave1 in Va strain V31-2 and of Ve1 in line A17 suggest that resistance to Verticillium wilt in M. truncatula A17 is novel and different from that described in other plants.

The transcriptional response of susceptible and resistant lines to Verticillium involves some shared genes, but with different expression levels

A common transcriptional response involving a few genes related to flavonoid biosynthesis and stress response was found in both M. truncatula lines. However, cytological studies showed that only line A17 accumulated autofluorescent soluble compounds, probably flavonoids, in inoculated roots. Such autofluorescent phenolic compounds were also induced by A. euteiches in roots of the resistant line A17 and to a lesser degree in the susceptible line F83005.5 (Djébali et al., 2009). Induction of genes involved in phenylpropanoid, terpenoid, and flavonoid biosynthesis is the most common response to Verticillium infection in resistant and in susceptible plants (Pegg and Brady, 2002; Fradin and Thomma, 2006). Accumulation of medicarpin, the major isoflavonoid phytoalexin in Medicago spp. (Naoumkina et al., 2010), has been observed in alfalfa callus inoculated with V. albo-atrum (Latunde-Dada and Lucas, 1986). The antifungal properties of phenolics known to be involved in defense against Verticillium wilt (Beckman, 2000; Báidez et al., 2007; Eynck et al., 2009). The phenolics-storing parenchyma cells may release these compounds into the xylem vessels to inhibit pathogen growth.

The resistant line A17 exhibited a higher level of gene expression for the functional category “secondary metabolism” at t0, compared to line F83005.5. This might indicate a state of “preparedness” and allow for a more efficient induction of phenolics after inoculation with Va (this study) or A. euteiches (Djébali et al., 2009). It has been reported that Va and other alfalfa pathogenic fungi are able to metabolize medicarpin (Soby et al., 1996) which might explain that phenolic compounds were not observed in the heavily colonized susceptible line.

Defense genes are induced in the resistant line after inoculation with V. alfalfae whereas the susceptible line suffers profound reprogramming of primary functions

Analysis of the response to Va inoculation by GO term enrichment showed that resistant line A17, in addition to genes of secondary metabolism, induced genes related to stress response, and notably to defense such as genes for PR4 protein and BetV1 proteins belonging to the PR10 family (Breiteneder et al., 1989).

In contrast, the susceptible line F83005.5 was severely affected in response to stress, defense mechanisms and in several metabolic pathways. Such a strong effect at early infection stages when only a very small part of the root is colonized, suggests that V31-2 is able to repress defense mechanisms and dysregulate plant metabolism by secreted effectors or toxins. Verticillium is described to produce several toxins which induce wilting symptoms but may also act as elicitors of defense, depending on their concentration and/or the plant genotype (Meyer et al., 1994; Wang et al., 2004; Palmer et al., 2005). Preliminary experiments showed that culture filtrate of strain Va V31-2 induces wilting symptoms and necrosis in M. truncatula (data not shown). SA has been reported to protect cotton callus against Verticillium toxin (Zhen and Li, 2004). The SA pathway was down-regulated in the susceptible M. truncatula line, notably genes encoding the SA receptor SABP2 (Kumar and Klessig, 2003) and the SA-regulated glutathione S-transferase (Uquillas et al., 2004), which might lead to enhanced susceptibility to toxins putatively produced by Va during infection.

Co-expression analysis identified a resistance-associated module and suggests that resistance to V. alfalfae involves PAMP-triggered immunity

By applying WGCNA using the MACE data of resistant line A17 we identified one module (called Greenyellow) of the co-expression network which was highly related to inoculation response and contained genes encoding LRR-RLKs, NB-LRRs or regulatory elements including transcription factors.

Various gene homologs encoding proteins involved in PAMP perception were detected, including BAK1, EFR, the chitin receptor CERK1, and PRK5 (Miya et al., 2007). Chitinases which release chitin fragments from fungal cell walls (Adams, 2004) were also present in the module. PRK5 encodes a protein kinase receptor with a PR5 family extracellular ligand binding domain (Wang et al., 1996). PR5 specifically binds and hydrolyzes β-1,3-glucans, components of fungi, and oomycete cell walls (Osmond et al., 2001). PRK5 probably fixes the same ligands as PR5. The receptor kinase BAK1 is required for the function of certain Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRR) lacking cytoplasmic signaling domain such as Ve1 (Heese et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010; Fradin et al., 2014). BAK1 has been shown to be involved in Arabidopsis resistance to V. longisporum (Roos et al., 2014), together with the brassinolide, JA and ABA signaling pathways. BAK1 interacts with the receptor EFR (Heese et al., 2007), which recognizes the bacterial PAMP EF-Tu (Zipfel et al., 2006). Surprisingly, BAK1 was also shown to be involved in the susceptibility of Arabidopsis Col-0 to V. dahliae (Gkizi et al., 2016).

Several homologs of genes involved in PTI signaling, such as NDR1, EDR1, and MKK2 (or MEK2) were also present in the resistance-associated module Greenyellow. NDR1 which is required for the activity of several CC-NB-LRR R proteins such as RPM1 (Aarts et al., 1998), participates in ETI and in PTI (Knepper et al., 2011), while EDR1 is a MAP kinase which exerts negative feedback on the activation of MAPK cascades and plays a key role in regulating defense mechanisms (Zhao et al., 2014).

The whole picture suggests that the M. truncatula response may resemble innate immunity and PTI rather than the more specific ETI, similar to the situation in resistant tomato and cotton. Indeed, NDR1, BAK1, and MEK2 were found to be required in tomato (Fradin et al., 2009), and FLS2, EFR, CERK1, BAK1, RPM1, PRS2, and MKK2 were found to be induced in resistant cotton G. raimondii after inoculation with V. dahliae (Chen et al., 2015). However, in M. truncatula the response is triggered without implication of a Ve1 homolog, suggesting a different mechanism of recognition of Verticillium and possibly of signaling.

Genes in the resistance-associated co-expression module indicate regulation by auxin and abscisic acid

In addition to genes involved in PAMP perception and signal transduction, the Greenyellow module contains genes related to hormone signaling. Although MapMan and GO term enrichment did not show significant induction of these genes in response to inoculation or over-expression at t0 in the resistant line, their co-regulation suggests their involvement in the resistance response. We identified the nodulin MtN21 (a homolog of Wat1), and mlo2 (mildew resistance locus 2 O) in this co-expression module. MLO proteins are involved in resistance against downy mildew in barley but also in dicot plants and prevent pathogen penetration (Consonni et al., 2006; Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2014). MtN21/WAT1 involved in secondary cell wall formation The Arabidopsis Wat1 mutant is more resistant to several vascular pathogens, probably due to constitutive activation of the SA pathway and inhibition of the auxin pathway (Denancé et al., 2013). Such effects on SA and auxin pathways were also observed in the mlo2 mutant (Consonni et al., 2006). The expression of these homologs in M. truncatula indirectly suggests activation of the auxin pathway in response to V. alfalfae.

WGCNA showed that the resistance-related response of line A17 was associated with induction of 21 putative TFs, most of them (71%) being also co-expressed in response to other pathogens of M. truncatula. Four among them are involved in ET signaling (Medtr1g069960.1, Medtr1g087920.1, Medtr1g093600.1, Medtr6g037610.1). In addition, genes encoding for ACC oxidases and genes with GO annotations “response to ethylene stimulus” like EBF1 (EIN3-binding F-box protein 1; Medtr4g114640.1) were identified. This indicates that ET signaling is activated in response to V. alfalfae. However, since ET signaling genes were also induced in the susceptible line and ACC pretreatment did only delay disease symptoms, ET does probably not contribute significantly to resistance.

Some TFs of the Greenyellow module belong to the MYB, NAC, bHLH, WRKY, and ERF TFs families that are also the most represented in the cotton transcriptome in response to V. dahliae (Zhang Y. et al., 2013). WRKY TFs play a crucial role in defense mechanisms (Pandey and Somssich, 2009), NAC TFs are involved in the response to abiotic stress and pathogens (Nuruzzaman et al., 2013) and bHLH93 is implicated in flowering in A. thaliana. Interestingly, flowering time and symptom severity were linked in V. longisporum—inoculated Arabidopsis (Häffner et al., 2010). These particular TFs were also found to participate in some ABA responses (Cutler et al., 2010; Wang Y. et al., 2013), and among the five genes encoding for PR10 proteins in this module, three encode for ABA-responsive protein ABR17 with a BetV1 domain. These results together with efficient protection by ABA pretreatment give some indication that the ABA pathway might be involved in M. truncatula resistance against V. alfalfae.

Co-expression analysis suggests that Verticillium resistance in Medicago truncatula may encompass a more general response to pathogens

A large number of genes identified in the resistance-associated Greenyellow module was also found to be co-expressed during the interaction of M. truncatula line A17 with four other root pathogens, among them 15 TFs (Figure 5). Because line A17 is susceptible toward three of these other pathogens, co-expression of these genes does not suggest, at first glance, a straightforward and decisive role uniquely in disease resistance. However, the experimental conditions were differing between the pathosystems and the data analyzed usually represent only a snapshot of the whole infection process. As a consequence, differences in intensities and/or timing of gene expression in this composite dataset might still not be sufficient to explain resistance to one given pathogen and susceptibility to others. We advocate that there is probably not one ultimate master switch responsible for the phenotype in QDR, but rather a collaboration of several regulatory genes which contribute to the final result. The core pathogen-responsive genes identified in our study might thus still participate in basal defense of M. truncatula against root pathogens.

Conclusion

Quantitative resistance of M. truncatula to V. alfalfae V31-2 involves the PTI signature elements NDR1, BAK1, and MKK2, as also reported in tomato and cotton, but does not rely on Ve1 or Ave1 homologs. The overlapping gene co-expression pattern in M. truncatula line A17 in response to V. alfalfae and to other root pathogens supports the view that A17 resistance to Verticillium presents major traits of PTI. Hence the interaction between M. truncatula A17 and V. alfalfae V31.2 provides an excellent model to investigate the relationship between PTI and quantitative resistance in a legume plant. Because of the quantitative nature of Verticillium resistance in M. truncatula and of the high number of putative regulatory and signaling genes with probably subtle and combined effects, a whole-genome approach based on the biodiversity in this plant species seems to be the most appropriate to address this question.

Author contributions

MT performed most experiments and GO term and MapMan analysis. CB contributed to the experimental design, statistical, and data analysis. AL participated in the microscopy study. LG contributed to the experimental design and performed statistical analysis of the MACE libraries sequencing data and WCGNA. MR contributed to the experimental design and data analysis. MT, CB, LG, and MR wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sebastien Rouanet for help with DNA extractions and PCR during his internship, and the GeT-PlaGe and Toulouse Réseau Imagerie, Genotoul platforms for the use of their facilities. MT was supported by a Ph.D. grant from the French Department of Mayotte.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DEG

Differentially expressed gene

- dpi

days post-inoculation

- GO term

Gene ontology term

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- qRT-PCR

quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR

- TF

Transcription factor

- Va

Verticillium alfalfa.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01431

References

- Aarts N., Metz M., Holub E., Staskawicz B. J., Daniels M. J., Parker J. E. (1998). Different requirements for EDS1 and NDR1 by disease resistance genes define at least two R gene-mediated signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 10306–10311. 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia J., Kusch S., Panstruga R. (2014). Macigal mystery tour: MLO proteins in plant immunity and beyond. New Phytol. 204, 273–281. 10.1111/nph.12889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D. J. (2004). Fungal cell wall chitinases and glucanases. Microbiology 150, 2029–2035. 10.1099/mic.0.26980-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrios G. N. (2004). Plant Pathology. Amsterdam; Boston, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Báidez A. G., Gómez P., Del Río J. A., Ortuño A. (2007). Dysfunctionality of the xylem in Olea europaea L. plants associated with the infection process by Verticillium dahliae kleb. Role of phenolic compounds in plant defense mechanism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 3373–3377. 10.1021/jf063166d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman C. H. (2000). Phenolic-storing cells: keys to programmed cell death and periderm formation in wilt disease resistance and in general defence responses in plants? Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 57, 101–110. 10.1006/pmpp.2000.0287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer D., Zimmermann H., Ziegenhagen B., Liepelt S. (2015). Differential gene expression reveals candidate genes for drought stress response in Abies alba (Pinaceae). PLoS ONE 10:e0124564. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben C., Toueni M., Montanari S., Tardin M. C., Fervel M., Negahi A., et al. (2013). Natural diversity in the model legume Medicago truncatula allows identifying distinct genetic mechanisms conferring partial resistance to Verticillium wilt. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 317–332. 10.1093/jxb/ers337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiteneder H., Pettenburger K., Bito A., Valenta R., Kraft D., Rumpold H., et al. (1989). The gene coding for the major birch pollen allergen Betv1, is highly homologous to a pea disease resistance response gene. EMBO J. 8, 1935–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. Y., Huang J. Q., Li N. Y., Ma X. F., Wang J. L., Liu C., et al. (2015). Genome-wide analysis of the gene families of resistance gene analogues in cotton and their response to Verticillium wilt. BMC Plant Biol. 15:148. 10.1186/s12870-015-0508-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collett D. (2002). Modelling Binary Data, 2nd Edn. London: Chapman and Hall, C. R. C. [Google Scholar]

- Conesa A., Götz S., García-Gómez J. M., Terol J., Talon M., Robles M. (2005). Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consonni C., Humphry M. E., Hartmann H. A., Livaja M., Durner J., Westpha L., et al. (2006). Conserved requirement for a plant host cell protein in powdery mildew pathogenesis. Nature Genet. 38, 716–720. 10.1038/ng1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S. R., Rodriguez P. L., Finkelstein R. R., Abrams S. R. (2010). Abscisic acid: emergence of a core signaling network. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 651–679. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl J. L., Horvath D. M., Staskawizc B. J. (2013). Pivoting the plant immune system from dissection to deployment. Science 341, 746–751. 10.1126/science.1236011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debieu M., Huard-Chauveau C., Genissel A., Roux F., Roby D. (2016). Quantitative disease resistance to the bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas campestris involves an Arabidopsis immune receptor pair and a gene of unknown function. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 510–520. 10.1111/mpp.12298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge R., van Esse H. P., Maruthachalam K., Bolton M. D., Santhanam P., Saber M. K., et al. (2012). Tomato immune receptor Ve1 recognizes effector of multiple fungal pathogens uncovered by genome and RNA sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5110–5115. 10.1073/pnas.1119623109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denancé N., Ranocha P., Oria N., Barlet X., Rivière M. P., Yadeta K. A., et al. (2013). Arabidopsis wat1 (walls are thin1)-mediated resistance to the bacterial vascular pathogen, Ralstonia solanacearum, is accompanied by cross-regulation of salicylic acid and tryptophan metabolism. Plant J. 73, 225–239. 10.1111/tpj.12027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djébali N., Jauneau A., Ameline-Torregrosa C., Chardon F., Jaulneau V., Mathé C., et al. (2009). Partial resistance of Medicago truncatula to Aphanomyces euteiches is associated with protection of the root stele and is controlled by a major QTL rich in proteasome-related genes. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22, 1043–1055. 10.1094/MPMI-22-9-1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z., Zhou X., Ling Y., Zhang Z., Su Z. (2010). agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucl. Acids Res. 38, W64–W70. 10.1093/nar/gkq310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eynck C., Koopmann B., Karlovsky P., Von Tiedemann A. (2009). Internal resistance in winter oilseed rape inhibits systemic spread of the vascular pathogen Verticillium longisporum. Phytopathology 99, 802–811. 10.1094/PHYTO-99-7-0802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]