Abstract

Background

Coal mine dust exposure causes chronic airflow limitation in coal miners resulting in dyspnea, fatigue, and eventually chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Yoga can alleviate dyspnea in COPD by improving ventilatory mechanics, reducing central neural drive, and partially restoring neuromechanical coupling of the respiratory system.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of Integrated Approach of Yoga Therapy (IAYT) in the management of dyspnea and fatigue in coal miners with COPD.

Materials and methods

Randomized, waitlist controlled, single-blind clinical trial. Eighty-one coal miners (36–60 years) with stable Stages II and III COPD were recruited. The yoga group received an IAYT module for COPD that included asanas, loosening exercises, breathing practices, pranayama, cyclic meditation, yogic counseling and lectures 90 min/day, 6 days/week for 12 weeks. Measurements of dyspnea and fatigue on the Borg scale, exercise capacity by the 6 min walk test, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2%), and pulse rate (PR) using pulse oximetry were made before and after the intervention.

Results

Statistically significant within group reductions in dyspnea (P < 0.001), fatigue (P < 0.001) scores, PR (P < 0.001), and significant improvements in SpO2% (P < 0.001) and 6 min walk distance (P < 0.001) were observed in the yoga group; all except the last were significant compared to controls (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Findings indicate that IAYT benefits coal miners with COPD, reducing dyspnea; fatigue and PR, and improving functional performance and peripheral capillary SpO2%. Yoga can now be included as an adjunct to conventional therapy for pulmonary rehabilitation programs for COPD patients.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Dyspnea, Exercise capacity, Fatigue, Yoga

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by progressive airflow obstruction, which is mainly irreversible [1]. Evidence shows that coal miners suffer increased risk of coal mine dust lung disease including COPD as a respiratory hazard of coal mining [2]. Cumulative exposure to coal dust is associated with increased risk of airway limitation [3] resulting in dyspnea and fatigue on exertion limiting physical activity [4], adversely affecting daily living [5] and quality of life [6]. Although dyspnea, “subjective experience breathing discomfort” [7] is considered the primary activity-limiting symptom in coal miners [8], other symptoms like fatigue the “subjective perception of mental or physical exhaustion due to exertion” [9] is a common feature in coal miners with COPD. It is one of the most frequently reported, distressing side effects reported by COPD patients, often having significant long-term consequences.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a comprehensive intervention that includes exercise training, education, and behavior modification, designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with COPD [10]. The evidence is increasing for the efficacy of several kinds of exercise training as part of pulmonary rehabilitation aimed at reducing dyspnea and fatigue, as well as improving health-related quality of life and exercise capacity in individuals with COPD [11]. Yoga has been included as a component of exercises prescribed for many pulmonary rehabilitation programs [12]. It has also been included as an adjunct to physical therapy treatment in industrial rehabilitation programs and proven to enhance mind-body coordination [13]. Studies of short-term yoga practices have reported improved lung function parameters [14], increased diffusion capacity [15], decreased dyspnea-related distress [16], and improved health-related quality of life [17]. Yoga would show efficacy for coal miners with COPD, a topic on which no previous study appears to have been done.

The IAYT is a program which was first applied to asthma some 30 years ago [18]. Other than respiratory problems, benefits have been demonstrated for various disorders such as cancer [19], [20], coronary artery bypass graft [21], hypertension [22], asthma [23], diabetes mellitus [24], osteoarthritis of knee [25], low back pain [26], anxiety and depression [27], autism spectrum disorder [28], and schizophrenia [29]. It includes asanas; pranayama; relaxation techniques; meditation; yogic counseling for stress management; chanting; and lectures on yogic lifestyle and philosophy [30].

Limited studies on COPD using other yoga systems have assessed its efficacy in an adjunctive role [14], [15], [16], [17]. Here we report a randomized controlled study of coal miners with COPD, evaluating the effects of IAYT on dyspnea, fatigue, exercise tolerance, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2%), and pulse rate (PR). We hypothesized that these parameters would improve in yoga group as compared to a control group, at least partly for reasons similar to its efficacy to asthma [18], [23], [31].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

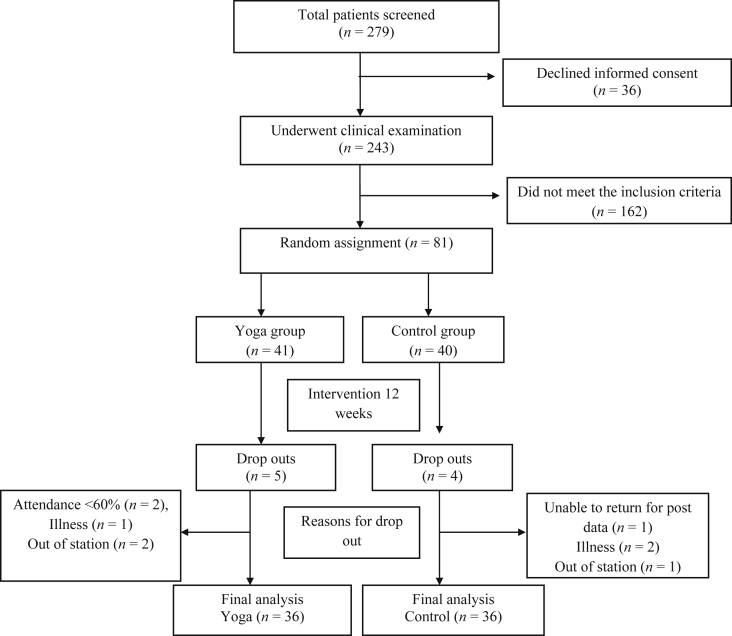

The coal miners of Rampur Colliery, Odisha, India were recruited as study participants. The study sample consisted of 81 non-smoking male coal miners in the age range 36–60 years. Of 279 coal miners screened, 162 failed at least one exclusion criterion; another 36 refused informed consent for the investigation; 81 signed up for the trial, but after nine further dropouts, final data were only available for 72 participants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Participant's flow chart

2.2. Inclusion criteria

Non-smoker male coal miners, aged 36–60 years, with moderate to severe stable physician-confirmed COPD satisfying Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, those with forced expiratory volume 1 (FEV1)/forced vital capacity ratio < 0.7 and postbronchodilator FEV1 < 80% predicted, clinically stable for at least 3 months prior to enrollment, able to walk without aid, willing to complete all study assessments and provide informed consent were included in the study.

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Patients with recent COPD exacerbation, unstable angina, respiratory tract infection within 1 month of the start of the study, myocardial infarction, angioplasty, heart surgery in the previous 3 months, basal blood pressure > 180/100 mmHg, resting PR > 120 bpm, body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m2, injury-free, no history of hospitalization, previous involvement in yoga rehabilitation programs, neuromuscular conditions interfering with exercise tests, present and ex-smokers (smoking is a confounding variable) were excluded.

2.4. Ethical clearance and informed consent

The study protocol was passed by S-VYASA's Institutional Ethical Committee. All procedures were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki research ethics. Each participant received detailed information about the study and provided written informed consent before the trial commenced.

2.5. Study design

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) on coal miners with COPD comparing add-on effect of IAYT to usual conventional care. Participants were randomized to yoga or waitlist control groups. The yoga group received IAYT for 90 min 6 days a week for 12 weeks.

2.6. Blinding and masking

Participants in yoga intervention group could not be blinded to treatment allocation arm due to the nature of the intervention. The team involved in assessments and the statistician who performed the randomization and final analysis were not involved in administering the intervention.

2.7. Intervention

Included a combination of asanas, loosening exercises, breathing exercises, pranayama, cyclic meditation, and yogic counseling and lectures (Table 1). IAYT aims to give a holistic treatment correcting imbalances at physical, mental, emotional, and intellectual levels using various components like those listed above [30]. For COPD special techniques were selected aiming for:

-

1.

Deeply relax various different muscle groups

-

2.

Slow the breath through breathing practices

-

3.

Strengthen respiratory muscles

-

4.

Calm the mind

-

5.

Balance emotions - equipoise

-

6.

Develop internal awareness and bliss in action.

Table 1.

Integrated approach of yoga therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease used in this study.

| Name of the practices | Duration (min) | Methodology | Benefits | Layer/Kosa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breathing practices | 10 | |||

| Standing | The movement of hands, legs, abdominal, or thoracic muscles as needed in each exercise is synchronized with the breathing For inhalation and exhalation, “in” and “out” instructions of the mind (or that of teacher) is used Effort should be made to slow down the breathing gradually Eyes will remain closed retaining the awareness throughout the practice [32] |

Strengthen the respiratory muscles, develop the awareness of expansion and contraction of the airways, make breathing uniform, continuous and rhythmic, oxygenate all parts of the lung, opens out blocked air passages, stabilize effect on bronchial reactivity, and improve respiratory function [18], [32], [33], [34] | Pranamaya Kosa (sheath of vital energy) [30], [35], [36] | |

| Hands in and out breathing | 1 | |||

| Hands stretch breathing | 1 | |||

| Ankle stretch breathing | 1 | |||

| Sitting | ||||

| Dog breathing | 1 | |||

| Rabbit breathing | 1 | |||

| Tiger breathing | 1 | |||

| Shashankasana breathing (moon pose) | 1 | |||

| Prone | ||||

| Bhujangasana breathing | 1 | |||

| Shalabhasana breathing | 1 | |||

| Supine | 1 | |||

| Straight leg raising breathing | ||||

| Loosening practices | 10 | These are performed stepwise with speed and repetitions which involve loosening of the joints, flexing of the spine. Attention during the practice is emphasized. The speed and number of repetitions should be increased depending on individual's capacity [32] | Improve stamina in all muscles, flexibility, and tolerance to exercise, clears CO2, improve pulmonary function, respiratory pressures, and overall cardiorespiratory fitness [32], [37], [38] | Annamaya Kosa (sheath of physical awareness) [30], [35], [36] |

| Forward and backward bending Side bending Twisting Pavanamuktasana kriya (alternate leg) Rocking and rolling Surya Namaskara × 3 rounds |

1 | |||

| 1 | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| 1 × 2 | ||||

| 1 × 2 | ||||

| 1 × 3 | ||||

| Yogasanas (physical postures) | 20 |

Sthiram sukham asanam//P.Y.S.2/46 Yogasanas are firm and comfortable postures. The key aspects are relaxation of the body, slowness of mind and of awareness of breathing [30] |

Yogah chitta vritti nirodhah//P.Y.S.1/2 Mastery over the modifications of the mind, release mental tensions by dealing with physical level, revitalize and relax the body, calm down the mind [32], [39], [40] |

Annamaya Kosa (sheath of physical awareness) [30], [35], [36] |

| Standing Ardhakati chakrasana (lateral arc pose) Padahastasana (forward bend pose) Ardha chakrasana (half wheel pose) |

Starting posture: Tadasana Relaxation: Shithila Tadasana |

Open up chest, improves stamina, increase confidence [32], [39], [40] | ||

| 2 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| Sitting Vakrasana (twisting posture) Ardhamatsyendrasana (half spinal twist posture) Paschimottanasana (sleeping thunderbolt posture) |

Starting posture: Dandasana Relaxation: Shithila Dandasana |

Improve flexibility of spine and strengthens thoracic, abdominal, and limb muscles [32], [39], [40] | ||

| 2 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| Prone Bhujangasana (serpent pose) Shalabhasana (locust pose) |

Starting posture: Makarasana Relaxation: Makarasana |

Improve shoulder flexibility, stamina in thigh muscles, release stiffness, increase lung capacity, and promote expansion of rib cage [32], [39], [40] | ||

| 2 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| Supine Sarvangasana (shoulder stand pose) Matsyasana (fish pose) |

2 2 |

Starting posture: Savasana Relaxation: Savasana |

Invigorate all parts of the body, improve metabolic rate [32], [39], [40] | |

| Yoga chair breathing | 10 | This is a special eight stepped breathing technique developed by SVYASA found on the knowledge base to help in breaking the vicious cycles of anxiety and bronchospasm during acute attacks by deconditioning autonomic arousal [32], [33], [41]. The participants were asked to resort to this technique using a chair as a props | Deep relaxation of respiratory muscles, opens up airway obstruction, overcomes the bronchospasm effectively, minimizes the acute episodes, improves confidence, and reduces panic anxiety [32], [33], [41] | Pranamaya Kosa (sheath of vital energy) [30], [35], [36] |

| Instant relaxation technique Neck muscle relaxation with chair support Neck movements in Vajrasana Shashankasana movement Relaxation in Tadasana Neck movements in Tadasana Ardha chakrasana - Padahastasana Quick relaxation technique |

1 | |||

| 1 | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| 1 | ||||

| Pranayama | 10 |

Tasmin sati svasa prasvasayor gati vicchedah pranayamah|P.Y.S. 2/49 After perfection of posture is attained, the movements of inhalation and exhalation are regulated by consciously breathing long, subtly and with counts while having attention on different parts of the body [42] |

Pranayamenayuktena sarvarogakshayo bhavet| |H.Y.P. 2/16 Improves balance of body-mind complex, brings emotional stability through slowing down the mental and physical processes, decreases metabolic activity, activates parasympathetic state, and improves lung function parameters [30], [39], [43], [44] |

Pranamaya Kosa (sheath of vital energy) [30], [35], [36] |

| Kapalabhati (frontal brain cleansing) (high-frequency yoga breathing technique) | 2 |

Kapalabhati consists of a series of fast successive bursts of exhalations followed by automatic passive inhalations [39], [45] It is performed rapidly like the bellows of a blacksmith [40] |

Kapalabhatirvikhyata kaphadosavisosani|H.Y.P 2/35 Strengthens diaphragm, cleanses lungs and entire respiratory tract, improves lung capacity, and increases tolerance of brain cells to acid–base imbalances in blood stream [39], [40], [45] |

|

| Vibhagiya pranayama (sectional breathing) | 2 | Preparatory practice having three sections: Abdominal Thoracic Clavicular breathing [39], [45] |

Increases vital capacity of the lungs, slows down the breath, strengthens of all three groups of muscles of respiration [39], [45] | |

| Nadishodhana pranayama (alternate nostril breathing) | 2 | Sitting in padmasana, air should be inhaled through the left nostril after having retained the breath as long as possible, it should be exhaled through the right nostril, and again inhaled through right after performing kumbhaka and exhaled through the left nostril [39], [40], [45] | Opens up nostrils, clears the nasal passages, calms down the mind, helps in bronchial asthma, nasal allergy, bronchitis, brings reduction in stress and autonomic balance, increases PEFR, PP, decreases PR, RR, BP, increases parasympathetic activity [39], [40], [45], [46] | |

| Ujjayi pranayama (diaphragmatic breathing) | 2 | With closed mouth, air should be inhaled deeply until the breath fills all the space between the throat down to the lungs with a hissing sound, after kumbhaka, the air should be exhaled through the left nostril [39], [40], [45] | This removes phlegm in the throat and helps in diseases due to kapha like tonsillitis, sore throat, chronic cold, cough and bronchial asthma, lowers the oxygen consumption and metabolic rate [39], [40], [45], [47] | |

| Bhramari pranayama (bee breathing) | 2 | After quick inhalation air is exhaled slowly producing a soft humming sound [39], [40], [45] | Relieves stress and cerebral tension, harmonize the mind, deals problems of a sore throat, tonsils, etc. [39], [40], [45] | |

| Meditation | 10 | Meditation should be done in any comfortable meditative posture with spine erect and eyes closed. Consciously breath is slowed down allowing the mind to calm down [30], [42] | Improves information processing in brain, reduces stress, decreases metabolic and RR, calms down the mind [30], [42], [48] | Manomaya Kosa (sheath of mental activities) [30], [35], [36] |

| Nadaanusandhana (alternate day) | 10 | Different sounds like A,U,M and AUM are chanted loudly so that they generate fine resonance all over the body [30], [40] | Improves emotional equipoise, higher creativity, freshness, lightness, awareness and expansion [30], [40] | |

| Om meditation (alternate day) | 10 | Sitting in any meditative posture “Om” is chanted mentally, not giving chance for distractions [30] | Achieves calmness, peace, serene, bliss, silence state of mind, improves concentration, memory, attention span [30], [49], [50] | |

| DRT in Savasana (corpse pose) | 10 | DRT is an eight step method developed by SVYASA DRT is an eight step method developed by SVYASA, practiced preferably lying down in savasana with eyes closed. This is done by taking a trip to different parts of the body from toes to head gradually with visualization, awareness and deeper feeling of relaxation [30] | Invigorates deep rest, decreases metabolic rate, reduces demand and stress, PR, RR, BP, muscle tension, oxygen consumption [30], [51], [52] | Annamaya Kosa (sheath of physical awareness) [30], [35], [36] |

| Yogic counseling/lectures | 10 | Yoga counseling, lectures, and interactions through questions and answers were essential for awareness of one's problems. It was conducted in a group and later one to one basis [30] | Helps to diagnose and remove the psychological conflicts of the individuals, enhances positive thinking and facilitates stress management [30] | Vijnanamaya Kosa (sheath of self-knowledge) [30], [35], [36] |

| Yoga philosophy and health, basis and applications of yoga, Panchakosa viveka (five layers of existence), Lifestyle modification, emotion and coping, diet and exercise, COPD causes, complications and lifestyle factors, Stress reaction and its management | ||||

| Kriya (once a week) | 90 | To cleanse the inner tracts, thereby developing involuntary control over voluntary reflexes [32] | Develops inner awareness; desensitizes hypersensitive reactions in the pathways [32], [33] | Annamaya Kosa (sheath of physical awareness) [30], [35], [36] |

| Theory on kriya | 10 | The procedure is explained with the help of diagrams prior to the practice | Provides knowledge on procedure, benefits, and limitations of each kriya | |

| Jala Neti | 20 | Lukewarm saline water is inserted through one nostril with a special neti pot and allowed to flow through the other nostril [32] |

Kaphadosa vinashyanti|G.S 1/51 Destroys the disorders of phlegm. Clears nasal passages, hypersensitivity, sinusitis and bronchitis [32] |

|

| Sutra Neti | 20 | Blunt soft rubber catheter is gently pushed through nose and pulled out through mouth massaging the nasal passage [32] | Clears nose and pharynx, mastery over involuntary reflexes of sneezing and cough, desensitize to dust and pollution, relieves in nasal allergy [32] | |

| Vamana Dhouti | 25 | Stomach is filled with warm saline water until one feels like vomiting. By pressing middle three fingers of the right hand on the root of the tongue vomiting sensation is stimulated until all water comes out [32] |

Kasasvasaplihakustham kapharogaschavimsatih Dhautikarmaprabhavena prayantyeva na samshayah H.Y.P.2/25 Clears the air passages through reflex stimulation, useful for asthma and bronchitis [32] |

|

| DRT | 15 | DRT was given by eight-step method of SVYASA [30] | Invigorates deep rest, decreases HR, RR, BP, muscle tension, oxygen consumption [30], [52] |

COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DRT = Deep relaxation technique, HR = Heart rate, BP = Blood pressure, RR = Respiration rate, PR = Pulse rate.

Participants in the yoga group were given yoga training sessions for 90 min, 6 days a week for 12 weeks by trained yoga instructors. They were instructed to perform asanas in a relaxed state of mind, without superfluous power, in a smooth, harmonized, steadily controlled manner, being fully cognizant of the physical movements with well-coordinated breathing pattern. Pranayamas included both slow and fast breathing practices. Waitlist controls were offered the 12 weeks yoga program after the intervention period and post-testing were complete.

2.8. Assessments

Six minute walk distance (6MWD), dyspnea, and fatigue were measured in both groups pre- and post-intervention. Participants were first administered the 6 minute walk test (6MWT), noting their distance walked in meters. Dyspnea and fatigue symptoms (on the Borg scale) and physiological data (SpO2, PR) were then recorded.

2.9. Six minute walk test

This was performed according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines [53]. As an objective measurement of true functional capacity, the 6MWT is usually better than self-reports or questionnaires to overcome over- or under-estimation. For patients with COPD it is a good indicator of exercise capacity and also reflects an individual's submaximal level of functional capacity to perform activities of daily living. In clinical practice, it is commonly used after a therapeutic intervention to evaluate improvement of responses, both symptomatic (dyspnea and fatigue) and physiological (distance walked, peripheral capillary SpO2%, and PR).

Participants were asked to walk back and forth at their own pace in a flat, straight, hard surfaced 35 m corridor, and to try and cover as much distance as possible in the time allotted. Rest stops were permitted during the test, but they were instructed to resume walking as soon as possible. Standardized phrases were used at each minute (e.g., “You are doing fine. Five minutes to go,” “Keep up the rhythm. Four minutes to go,” “You are doing fine. You are halfway to the end,” “Keep up the rhythm. Only 2 min to go,” “You are doing fine. Only 1 min to go”). Total distance covered was recorded.

2.10. Dyspnea

Participants were asked to rate their subjective scores of “shortness of breath” on cessation of the 6MWT using the modified Borg scale on a score of 0–10. This consists of a vertical number scale ranging from 0 (none) to 10 (maximal), with corresponding verbal expressions of the magnitude of breathing difficulty. Higher scores indicate worse dyspnea.

2.11. Fatigue

Participants were asked to rate their degree of fatigue on a vertical modified Borg's scale labeled 0–10, with 0 at the top indicating “nil” fatigue and “10” at the bottom representing “worst possible experience of fatigue.” The scores were noted before and after the intervention.

2.12. Pulse oximetry

Pulse oximetry is a non-invasive method affording a rapid measurement of oxygenation of hemoglobin in the peripheral capillary [54]. Post-exercise peripheral capillary SpO2% and PR were assessed for every participant using a portable pulse-oximetry device (Nonin 9570 light emitting diode pulse oximeter, USA). Percentage of peripheral capillary SpO2% was measured after connecting the optical diodes on the patients' fingers by transcutaneous pulse oximetry. Each experiment was performed thrice, and mean values were recorded. None had a baseline SpO2 < 88% or received domiciliary oxygen therapy.

2.13. Data collection

Demographic and vital clinical data (Table 2) including personal, job, family, and stress history were obtained by semistructured interviews at the time of enrollment. Participants underwent physical examinations, anthropometric measurements, and assessment of lung function. BMI was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Dyspnea and fatigue were assessed by modified Borg scale. Peripheral capillary SpO2% and PR were measured by pulse oximetry as described above.

Table 2.

Homogeneity test for age, life stress, duration of disease, and anthropometric measures between the yoga and control group.

| Variable | Yoga | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 36 | 36 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 53.69 ± 5.66 | 54.41 ± 5.40 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Asthmatic bronchitis | 9 | 7 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 12 | 18 |

| Emphysema | 15 | 11 |

| Duration of employment in coal mines (mean ± SD) | 28.36 ± 4.62 | 27.72 ± 4.23 |

| Duration of disease since diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 9.92 ± 3.25 | 10.69 ± 2.54 |

| Stress history n (%) | ||

| Family | 8 (22.2) | 6 (16.7) |

| Financial | 7 (19.4) | 9 (25.0) |

| Health | 12 (33.3) | 14 (38.9) |

| Job | 6 (16.7) | 5 (13.9) |

| Nil | 3 (8.3) | 2 (5.6) |

| GOLD COPD severity, n (%) | ||

| GOLD II – moderate | 19 (52.8) | 21 (58.3) |

| GOLD III – severe | 17 (47.2) | 15 (41.7) |

| Height (cm) | 161.17 | 158.75 |

| Weight (kg) | 62.73 | 59.38 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.15 | 23.57 |

GOLD = Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease, BMI = Body mass index, SD = Standard deviation, COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

2.14. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 18 (IBM Corporation, USA). After ascertaining normality of data, paired t-tests were used to determine the significance of variable differences before and after the intervention. Means of the both groups were compared for all variables using Student's t-test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic data

Of the 81 coal miners who were recruited, 72 (36 in each group) completed all assessments. Fig. 1 shows the study profile. There were five dropouts from the yoga and four from the control group. Table 2 compares the demographic details, clinical and functional characteristics, and stress history of the study population. No significant differences were found in this comparison. The mean age of the yoga group was 53.69 ± 5.66 years (range: 36–60 years) and in the control group, 54.36 ± 5.40 years (range: 37–60 years). The number of participants with GOLD Stage II and GOLD Stage III was 19 and 17 in yoga; and 21 and 15 in the control group. The mean duration of disease was 9.92 ± 3.25 years in yoga group and 10.69 ± 2.54 years in the control group. Differences between mean ages, severity, and duration of disease in the two groups were not significant.

3.2. Changes in the variables after yoga intervention

For the majority of patients, the intensity of dyspnea and fatigue decreased after the yoga intervention; they were also able to walk further in the stipulated 6 min time. Similar improvements were also observed between pre- and post-intervention testing in their physiological responses (SpO2 and PR) after the 6MWT (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes of participants before intervention (baseline), at end of therapy.

| Variables | Yoga (n = 36) |

Control (n = 36) |

Between groups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre |

Post |

Pre |

Post |

||||||||

| Mean ± SD | CI (LB to UB) | Mean ± SD | CI (LB to UB) | Mean ± SD | CI (LB to UB) | Mean ± SD | CI (LB to UB) | Pre versus pre | Post versus post | Group*time interaction | |

| Borg - dyspnea | 5.08 ± 1.40 | 4.61–5.56 | 3.84 ± 1.75*** | 3.25–4.44 | 5.25 ± 1.61 | 4.71–5.79 | 4.93 ± 2.02 | 4.24–5.62 | 0.641 | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| Borg - fatigue | 4.91 ± 1.34 | 4.46–5.37 | 3.64 ± 1.64*** | 3.08–4.19 | 4.78 ± 1.69 | 4.21–5.35 | 4.51 ± 1.68 | 3.95–5.08 | 0.701 | 0.028 | <0.001 |

| 6MWD (m) | 298.36 ± 65.20 | 276.30–320.42 | 357.81 ± 73.45*** | 332.95–382.66 | 304.67 ± 67.59 | 281.80–327.53 | 321.08 ± 80.17*** | 293.96–348.21 | 0.688 | 0.047 | <0.001 |

| SpO2% | 92.47 ± 1.87 | 91.84–93.11 | 93.69 ± 2.47*** | 92.86–94.53 | 92.36 ± 1.58 | 91.82–92.90 | 92.58 ± 1.71 | 92.00–93.16 | 0.787 | 0.030 | <0.001 |

| PR | 104.27 ± 8.37 | 101.45–107.11 | 99.80 ± 7.41*** | 97.30–102.31 | 103.08 ± 8.38 | 100.25–105.92 | 104.17 ± 8.38 | 101.33–107.00 | 0.547 | 0.022 | <0.001 |

***P < 0.001. 6MWT = 6 min walk test, SpO2 = Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation, PR = Pulse rate, SD = Standard deviation, CI = Confidence interval, LB = Lower bound, UB = Upper bound, 6MWD = 6 min walk distance.

3.3. Dyspnea and fatigue

Paired sample t-test showed a small but insignificant decrease in dyspnea score of 6.09% (P = 0.127) and in fatigue score of 5.65% (P = 0.226) in the control group. In contrast, the observed reductions in mean dyspnea score of 24.41% and in mean fatigue score of 25.86% in the yoga group after the intervention were both highly significant (P < 0.001). These suggest definite improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness levels. Statistically, there was a significant difference between the postvalues of the two groups (P = 0.018, independent sample t-test).

3.4. Six minute walk test

The post intervention changes in the 6MWD in both the groups were statistically significant (P < 0.001). But the magnitude of change was higher (19.93%) for the yoga group than the control group (5.39%). In addition, significant group mean differences were observed between yoga and control group's post intervention scores (P = 0.047, independent sample t-test).

3.5. Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation and pulse rate

Paired sample t-test showed a significant change in peripheral capillary SpO2% and PR after yoga training sessions in the yoga group, but no change in controls. Peripheral capillary SpO2% increased by 1.32% (P < 0.001) in yoga group but remained almost unchanged (0.24%, P = 0.173) in control group with a significant difference between the groups (P = 0.030). In the yoga group PR decreased by 4.28% (P < 0.001), whereas it increased by 1.05% (P = 0.054) in controls. There was a significant difference between the postvalues of groups (independent samples t-test, P = 0.022).

4. Discussion

The study evaluated add-on effects of 12 weeks integrated yoga therapy on dyspnea, fatigue, functional exercise capacity, SpO2, and PR in coal miners with COPD as an adjunct to conventional care. No adverse effects were observed. Patients in yoga and control groups were statistically similar across all parameters at baseline (P > 0.05). The two groups were comparable. Results showed statistically significant declines in dyspnea and fatigue and increase in functional performance in coal miners with COPD after the yoga intervention, leading to some plausibly concrete conclusions. Significant, firm, and progressive improvement in the key objective variables; functional exercise capacity, SpO2 and PR in the yoga group but not controls indicate yoga's effectiveness.

The encouraging effect of yoga on COPD is consistent with conclusions of previous studies [14], [15], [16], [17]. In this study, 6MWD increased by 59.45 m in the yoga group and 16.41 m in controls; a clinically significant difference in participants' exercise performance, similar to Donesky's 2009 pilot study (improved 21.5 ± 7.0 m for yoga, 8.3 ± 10.9 m for usual care) after yoga training. A meta-analysis of five RCTs involving 233 patients [55] concluding that yoga training has a positive effect on functional exercise capacity in patients with COPD also supports these findings. Another study on severe COPD, 54 m (95% confidence interval, 37–71 m) was identified as the minimum difference in a COPD patient to perceive improvements between one test and another as clinically significant [56]. Another study observed a mean increase of 50 m (20%) in 6MWD for COPD patients after exercise and diaphragmatic strength training [57]. Mahler et al. [58] showed a comparable small decrease in dyspnea intensity, regardless of improved exercise capacity after six weeks exercise training in COPD patients. An earlier study has reported yoga breathing exercise induced greater resting SpO2 in patients with COPD [59].

Differences in the sampling, study design, characteristics of participants, type of yoga training and duration of yoga may account for differences in findings to some extent. Our population comprised mild to severe COPD sufferers attending an outpatient clinic. Our findings may differ from those of hospital-based studies. To meet exacting demands of methodology, some recent studies may have overlooked basic features of yoga, which is much more than breathing exercises. Including all components of yoga together as in IAYT used in this study has more beneficial effects. However, none of the previous trials have gone into the possible mechanisms by which yoga might help COPD and did not provide adequate data or sufficient clinical evidence to support the beneficial effects of yoga training on these relevant findings.

Mechanisms to account for the favorable effects of yoga training are complex and yet to be elucidated. Several factors may contribute to the beneficial effects observed in this study. Yoga represents a form of mind-body fitness. IAYT includes a combination of asanas, pranayama, meditation and relaxation, and internally directed mental focus on awareness of self, breathing, and energy. Regular practice tones up general body systems, calms the mind, improves blood circulation, enhances energy levels, expands the lungs, relaxes chest muscles, and increases the strength of respiratory muscles [30]. It has been found that slow comfortable breaths help patients breathe more deeply by efficiency of the shoulder, thoracic, and abdominal muscles; lead to an increase in parasympathetic modulation and regulating chemoreceptive sensitivity [60].

Observed improvements in perception of dyspnea may result from a decrease in sympathetic reactivity achieved by yogic training, promoting broncho-dilatation by correcting abnormal breathing patterns and reducing muscle tension in inspiratory and expiratory muscles [32]. Improved breathing patterns may widen bronchioles so that larger numbers of alveoli can be efficiently perfused [15]. Pranayama practices stretch lung tissue, alleviating dyspnea by decreasing dynamic hyperinflation of the rib cage and recuperating gas exchange, enhancing respiratory muscles' strength and endurance, and optimizing thoracoabdominal patterns of motion [61]. Modifications in efferent vagal activity affect the caliber of airways reducing dyspnea.

Observed improvements in fatigue scores can be explained by various interrelated factors. First, in asanas, muscles are toned, energy conserved and sympathetic activity balanced, while mental relaxation and greater parasympathetic function affect cardiorespiratory activity, relax the vasomotor center, and reduce PR, ultimately leading to reduced feelings of fatigue. Pranayama helps in the full utilization of the lungs, enhancing ventilatory function, reducing oxygen debt, improving gas exchange, and thus preventing exhaustion.

Observed improvements in 6MWD are due to yoga's beneficial effects on musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory systems, improving cardiovascular efficiency and homeostatic control of the body. Muscle conditioning during yoga's intense stretching postures helps by improving oxidative capacity and strength of skeletal muscles, flexibility, endurance, coordination, power, static and dynamic stability, decreasing glycogen utilization, in turn improving physical performance and increasing walking pace and stride length [62].Yoga relaxation techniques have shown to improve cardiopulmonary endurance through body-and-breath control, which manifest clinically as improved lung capacity, increased oxygen delivery and decreased PR, resulting in overall improved exercise capacity. Improvements in 6MWD in the control group were statistically but not clinically significant (< 54 m). Changes in score may also be due to ordinary performance (no intervention), improved coordination, finding optimal stride length, or overcoming anxiety [53].

Improvements in blood SpO2% may be associated with the practice of pranayama, which engage normally unventilated lungs and help circulation, ventilation, and perfusion better, increasing oxygen delivery to muscles. Pranayama increases strength of respiratory muscles, reduces sympathetic reactivity, probably through improved oxygen delivery to tissues, possibly supplemented by acquired “tolerance” to hypoxia produced by changes in chemoreflex threshold and decreased dyspnea.

Deep relaxation technique, an important component of IAYT showed significant reductions in the yoga group's PR, possibly due to modulation of cardiac autonomic function and cardiorespiratory efficiency. It may also synchronize neural elements in the brain, leading to ANS changes, resulting parasympathetic dominance and blunted sympathetic activity leading to reduced PR [3]. Pranayama modifies various inflatory and deflatory lung reflexes and interacts with central neural elements to improve homeostatic control [63]. In this study, yoga may have reduced ventilator requirements at the end of 6MWT, thereby decreasing PR.

4.1. Scope and limitations of the study

This is the first randomized controlled study of yoga for coal miners with moderate to severe COPD. It used IAYT, and its reasonable sample size offers good evidence for the benefits of yoga-based rehabilitation. Having additional subgroups stratified as mild, moderate, severe, and very severe would have made the study more vigorous. In addition, we did not measure arterial blood gas components, such as PaO2, which would have produced more detailed results, providing a fuller picture of subject's physiology. If the measures of PR monitoring and heart rate variability had been used during the exercise test, effects would have been assessed more objectively. Similarly, assessments of biochemical variables involved would throw light on mechanisms. We would recommend a multicenter RCT to confirm results of the study, with a longer follow-up of 12 months or more to evaluate long-term efficacy.

5. Conclusions

The study's promising results, reducing dyspnea and fatigue, and improving functional exercise capacity in COPD patients, indicate the value of using yoga in programs of pulmonary rehabilitation as an adjunct to conventional care. More rigorously designed, larger scale research with longer follow-up should be conducted, particularly as that would also expand yoga's evidence base.

Source of support

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Mr Rajeev Lochan for technical assistance; the teachers of the yoga classes, Mrs. Sumati Badhai, and Mr. Kunja Bihari Badhai for providing individualized and continual support for the participants; Mr. Arjun Biswal for coordinating the program and Dr. Balaram Pradhan, Ph.D. for statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Transdisciplinary University, Bangalore.

References

- 1.Rabe K.F., Hurd S., Anzueto A., Barnes P.J., Buist S.A., Calverley P. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laney A.S., Weissman D.N. Respiratory diseases caused by coal mine dust. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(Suppl. 10):S18–S22. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santo Tomas L.H. Emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in coal miners. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:123–125. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283431674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waschki B., Kirsten A., Holz O., Müller K.C., Meyer T., Watz H. Physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort study. Chest. 2011;140:331–342. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabinovich R.A., Vilaró J., Roca J. Evaluation exercise tolerance in COPD patients: the 6-minute walking test. Arch Bronconeumol. 2004;40:80–85. doi: 10.1016/s1579-2129(06)60199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman G.J. Improving the quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: focus on indacaterol. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:89–96. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S31209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parshall M.B., Schwartzstein R.M., Adams L., Banzett R.B., Manning H.L., Bourbeau J. An official American thoracic society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:435–452. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer T.T., Schultze-Werninghaus G., Kollmeier J., Weber A., Eibel R., Lemke B. Functional variables associated with the clinical grade of dyspnea in coal miners with pneumoconiosis and mild bronchial obstruction. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:794–799. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.12.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theander K., Unosson M. Fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:172–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spruit M.A., Singh S.J., Garvey C., ZuWallack R., Nici L., Rochester C. An official American thoracic society/European respiratory society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:e13–e64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy B., Casey D., Devane D., Murphy K., Murphy E., Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD003793. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodgkin J., Celli B., Connors G. 4th ed. American Association of Cardiovascular & Pulmonary Rehabilitation; Chicago: 2009. Guidelines for pulmonary rehabilitation programs. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rachiwong S., Panasiriwong P., Saosomphop J., Widjaja W., Ajjimaporn A. Effects of modified hatha yoga in industrial rehabilitation on physical fitness and stress of injured workers. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25:669–674. doi: 10.1007/s10926-015-9574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fulambarker A., Farooki B., Kheir F., Copur A.S., Srinivasan L., Schultz S. Effect of yoga in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Ther. 2012;19:96–100. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181f2ab86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soni R., Munish K., Singh K., Singh S. Study of the effect of yoga training on diffusion capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a controlled trial. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:123–127. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.98230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donesky-Cuenco D.A., Nguyen H.Q., Paul S., Carrieri-Kohlman V. Yoga therapy decreases dyspnea-related distress and improves functional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:225–234. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santana M.J., S-Parrilla J., Mirus J., Loadman M., Lien D.C., Feeny D. An assessment of the effects of Iyengar yoga practice on the health-related quality of life of patients with chronic respiratory diseases: a pilot study. Can Respir J. 2013;20:e17–e23. doi: 10.1155/2013/265406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. Yoga for bronchial asthma: a controlled study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:1077–1079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6502.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandwani K.D., Perkins G., Nagendra H.R., Raghuram N.V., Spelman A., Nagarathna R. Randomized, controlled trial of yoga in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1058–1065. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vadiraja R., Raghavendra H.S., Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R., Rekha M., Vanitha N. Effects of a yoga program on cortisol rhythm and mood states in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8:37–46. doi: 10.1177/1534735409331456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raghuram N., Parachuri V.R., Swarnagowri M.V., Babu S., Chaku R., Kulkarni R. Yoga based cardiac rehabilitation after coronary artery bypass surgery: one-year results on LVEF, lipid profile and psychological states – a randomized controlled study. Indian Heart J. 2014;66:490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mashyal P., Bhargav H., Raghuram N. Safety and usefulness of laghu shankha prakshalana in patients with essential hypertension: a self controlled clinical study. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2014;5:227–235. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.131724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao Y.C., Kadam A., Jagannathan A., Babina N., Rao R., Nagendra H.R. Efficacy of naturopathy and yoga in bronchial asthma. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;58:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDermott K.A., Rao M.R., Nagarathna R., Murphy E.J., Burke A., Nagendra R.H. A yoga intervention for type 2 diabetes risk reduction: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:212. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebnezar J., Nagarathna R., Yogitha B., Nagendra H.R. Effect of integrated yoga therapy on pain, morning stiffness and anxiety in osteoarthritis of the knee joint: a randomized control study. Int J Yoga. 2012;5:28–36. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.91708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tekur P., Nagarathna R., Chametcha S., Hankey A., Nagendra H.R. A comprehensive yoga programs improves pain, anxiety and depression in chronic low back pain patients more than exercise: an RCT. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Satyapriya M., Nagarathna R., Padmalatha V., Nagendra H.R. Effect of integrated yoga on anxiety, depression & well-being in normal pregnancy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radhakrishna S., Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. Integrated approach to yoga therapy and autism spectrum disorders. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2010;1:120–124. doi: 10.4103/0975-9476.65089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duraiswamy G., Thirthalli J., Nagendra H.R., Gangadhar B.N. Yoga therapy as an add-on treatment in the management of patients with schizophrenia – a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. 2nd ed. Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashan; Bangalore: 2013. Integrated approach of yoga therapy for positive health. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagendra H.R., Nagarathna R. An integrated approach of yoga therapy for bronchial asthma: a 3-54-month prospective study. J Asthma. 1986;23:123–137. doi: 10.3109/02770908609077486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. 1st ed. Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashan; Bangalore: 2012. Yoga for bronchial asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. 2nd ed. Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashan; Bangalore: 2003. Yoga for common ailments; pp. 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santaella D.F., Devesa C.R., Rojo M.R., Amato M.B., Drager L.F., Casali K.R. Yoga respiratory training improves respiratory function and cardiac sympathovagal balance in elderly subjects: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000085. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lokeswarananda S. 1st ed. The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture; Kolkata: 2005. Taittiriya upanisad; pp. 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagendra H.R. Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust; Kanyakumari: 1980. The basis for an integrated approach in yoga therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mody B.S. Acute effects of Surya Namaskar on the cardiovascular & metabolic system. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2011;15:343–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhavanani A.B., Udupa K., Madanmohan, Ravindra P.N. A comparative study of slow and fast suryanamaskar on physiological function. Int J Yoga. 2011;4:71–76. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.85489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saraswati S.S. 4th ed. Yoga Publications Trust; Munger: 2012. Asana, pranayama, mudra bandha. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muktibodhananda S. 2nd ed. Yoga Publications Trust; Munger: 2004. Hatha yoga pradipika. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R., Seethalakshmi R. Yoga – chair breathing for acute episodes of bronchial asthma. Lung India. 1991;9:141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saraswati S.S. 1st ed. Yoga Publications Trust; Munger: 2008. Four chapters on freedom. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jerath R., Edry J.W., Barnes V.A., Jerath V. Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: neural respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dinesh T., Gaur G., Sharma V., Madanmohan T., Harichandra Kumar K., Bhavanani A. Comparative effect of 12 weeks of slow and fast pranayama training on pulmonary function in young, healthy volunteers: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Yoga. 2015;8:22–26. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.146051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagendra H.R. 3rd ed. Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashan; Bangalore: 2007. Pranayama the art and science. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Upadhyay Dhungel K., Malhotra V., Sarkar D., Prajapati R. Effect of alternate nostril breathing exercise on cardiorespiratory functions. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008;10:25–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Telles S., Desiraju T. Oxygen consumption during pranayamic type of very slow-rate breathing. Indian J Med Res. 1991;94:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Telles S., Raghavendra B.R., Naveen K.V., Manjunath N.K., Kumar S., Subramanya P. Changes in autonomic variables following two meditative states described in yoga texts. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:35–42. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Telles S., Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. Autonomic changes while mentally repeating two syllables – one meaningful and the other neutral. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;42:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Telles S., Nagarathna R., Nagendra H.R. Autonomic changes during “OM” meditation. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;39:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vempati R.P., Telles S. Yoga-based guided relaxation reduces sympathetic activity judged from baseline levels. Psychol Rep. 2002;90:487–494. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.2.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Telles S., Reddy S.K., Nagendra H.R. Oxygen consumption and respiration following two yoga relaxation techniques. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2000;25:221–227. doi: 10.1023/a:1026454804927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crapo R.O., Casaburi R., Coates A.L., Enright P.L., MacIntyre N.R., McKay R.T. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schermer T., Leenders J., in 't Veen H., van den Bosch W., Wissink A., Smeele I. Pulse oximetry in family practice: indications and clinical observations in patients with COPD. Fam Pract. 2009;26:524–531. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu X.C., Pan L., Hu Q., Dong W.P., Yan J.H., Dong L. Effects of yoga training in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:795–802. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.06.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Redelmeier D.A., Bayoumi A.M., Goldstein R.S., Guyatt G.H. Interpreting small differences in functional status: the six minute walk test in chronic lung disease patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1278–1282. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.4.9105067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiner P., Magadle R., Berar-Yanay N., Davidovich A., Weiner M. The cumulative effect of long-acting bronchodilators, exercise, and inspiratory muscle training on the perception of dyspnea in patients with advanced COPD. Chest. 2000;118:672–678. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahler D.A., Fierro-Carrion G., Mejia-Alfaro R., Ward J., Baird J.C. Responsiveness of continuous ratings of dyspnea during exercise in patients with COPD. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:529–535. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000158188.90833.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pomidori L., Campigotto F., Amatya T.M., Bernardi L., Cogo A. Efficacy and tolerability of yoga breathing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29:133–137. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31819a0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bernardi L., Sleight P., Bandinelli G., Cencetti S., Fattorini L., Wdowczyc-Szulc J. Effect of rosary prayer and yoga mantras on autonomic cardiovascular rhythms: comparative study. BMJ. 2001;323:1446–1449. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gosselink R. Controlled breathing and dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(5 Suppl. 2):25–33. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.10.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katiyar S.K., Bihari S. Role of pranayama in rehabilitation of COPD patients – a randomized controlled study. Indian J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;20:98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tandon O.P., Tripathi Y., editors. Best and Taylor's physiological basis of medical practice. 13th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins Publishers; Gurgaon: 2012. [Google Scholar]