ABSTRACT

Erythrocytes are reservoirs of important epoxide-containing lipid signaling molecules, including epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs). EETs function as vasodilators and anti-inflammatory modulators in the bloodstream. Bioactive EETs are hydrolyzed to less active diols (dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids) by epoxide hydrolases (EHs). The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum infects host red blood cells (RBCs) and exports hundreds of proteins into the RBC compartment. In this study, we show that two parasite epoxide hydrolases, P. falciparum epoxide hydrolases 1 (PfEH1) and 2 (PfEH2), both with noncanonical serine nucleophiles, are exported to the periphery of infected RBCs. PfEH1 and PfEH2 were successfully expressed in Escherichia coli, and they hydrolyzed physiologically relevant erythrocyte EETs. Mutations in active site residues of PfEH1 ablated the ability of the enzyme to hydrolyze an epoxide substrate. Overexpression of PfEH1 or PfEH2 in parasite-infected RBCs resulted in a significant alteration in the epoxide fatty acids stored in RBC phospholipids. We hypothesize that the parasite disruption of epoxide-containing signaling lipids leads to perturbed vascular function, creating favorable conditions for binding and sequestration of infected RBCs to the microvascular endothelium.

IMPORTANCE

The malaria parasite exports hundreds of proteins into the erythrocyte compartment. However, for most of these proteins, their physiological function is unknown. In this study, we investigate two “hypothetical” proteins of the α/β-hydrolase fold family that share sequence similarity with epoxide hydrolases (EHs)—enzymes that destroy bioactive epoxides. Altering EH expression in parasite-infected erythrocytes resulted in a significant change in the epoxide fatty acids stored in the host cell. We propose that these EH enzymes may help the parasite to manipulate host blood vessel opening and inflame the vessel walls as they pass through the circulation system. Understanding how the malaria parasite interacts with its host RBCs will aid in our ability to combat this deadly disease.

INTRODUCTION

Asexual replication of the malaria parasite occurs within the host red blood cell (RBC). After RBC invasion, the parasite exports several hundred proteins beyond the parasite plasma membrane and parasitophorous vacuolar membrane (surrounding the parasite) into the RBC compartment (1, 2). Exported proteins can alter the flexibility of the RBC cytoskeletal network, resulting in increased cell rigidity compared to uninfected RBCs (3). Additionally, several exported proteins are displayed as surface adhesins resulting in cytoadherence of infected erythrocytes to endothelial cell ligands, including intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) (3, 4). This cytoadherence allows infected RBCs to avoid premature clearance by the spleen, before the 48-h life cycle of the parasite is completed. A pentameric signal sequence, called the Plasmodium export element (PEXEL; also known as the host targeting signal) (5, 6), is essential for delivery of most exported proteins. On the basis of identification of this PEXEL sequence, the “exportome” of Plasmodium falciparum has been predicted (7–9). Additionally, PEXEL-negative exported proteins have been identified (10), and these proteins add to the number of parasite proteins exported into the RBC. Despite our ability to predict and localize exported proteins, their functions, particularly how they interact/interfere with RBC physiology, remain largely uncharacterized.

RBCs are important regulators of vascular tone. While in circulation, in response to low oxygen content, RBCs release ATP, which interacts with purinergic P2Y receptors on endothelial cells to promote nitric oxide (NO) synthesis (11). Subsequent NO release into the bloodstream inhibits further ATP release from erythrocytes in a negative-feedback loop. The ATP released from erythrocytes also acts in an autocrine manner, activating RBC purinergic P2X7 receptors, which in turn activate cytosolic phospholipase A2 (11). RBCs contain significant pools of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) (12–15), which are epoxide-containing signaling lipids, released from RBCs in a phospholipase A-dependent manner (16, 17). EETs interact with smooth muscle cells, resulting in activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels, hyperpolarization, and subsequent relaxation/vasodilation (18). EETs (like NO) are anti-inflammatory (19, 20), inhibiting activation of the NF-κB transcription factor in endothelial cells, preventing transcription of endothelium surface receptors, such as ICAM-1 (19).

In healthy individuals, NO and prostacyclins are the main regulators of vasodilation (18); however, in cardiovascular disease states (18), or when NO/prostacyclin biosynthesis is inhibited (21), EETs increase in importance. It is well established that during malaria infection, plasma levels of NO are severely diminished by multiple mechanisms (22–25). The reduction in the bioavailability of NO contributes to the disruption of basal vasoregulation and, thereby, to the cerebral and pulmonary hypertension and reduced blood flow observed in malaria patients (26). When the concentration of NO is reduced, NF-κB-mediated transcription of adhesin ligands is enhanced, promoting infected-erythrocyte sequestration in the microvasculature. Given the decrease in available NO during malaria, we hypothesized that host EET signaling may become more important during malaria infection. If the anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory properties of the EETs could compensate for the decrease in NO, this would be potentially disadvantageous to the parasite (as an “activated” endothelium is beneficial for cytoadherence).

EETs (20-carbon metabolites derived from arachidonic acid), and other anti-inflammatory omega-3 and omega-6 epoxygenated fatty acids, including epoxyoctadecenoic acids (EpOMEs; 18 carbon equivalents derived from linoleic acid) are metabolized by epoxide hydrolases (EHs), converting the active epoxide fatty acids into much less active diols (27, 28). EHs are α/β hydrolases that function both in the detoxification of exogenous epoxides (including toxins/drug metabolites) and in the regulation of lipid signaling epoxides.

P. falciparum carries genes that encode four α/β-hydrolases containing PEXEL motifs (5, 8), and all four α/β-hydrolases are present only in the Laverania subgenus (P. falciparum and Plasmodium reichenowi), with no identifiable syntenic orthologues in other Plasmodium species (29). In this study, we demonstrate that all four α/β-hydrolases are exported. Two of the α/β-hydrolases share sequence homology with EHs, and our results suggest that, despite having atypical catalytic serine residues, they are capable of hydrolyzing bioactive erythrocyte epoxides to less active 1,2-diols. These enzymes are able to deplete the host erythrocyte of vasoactive epoxides and therefore may play an important role in the vascular biology of malaria infection.

RESULTS

Four PEXEL-containing α/β-hydrolases are grouped in two families with different predicted activities.

P. falciparum carries genes that encode four α/β-hydrolases containing PEXEL motifs, grouped into two families: α/β-hydrolase group A (PF3D7_0301300 and PF3D7_1401300) and α/β-hydrolase group B (PF3D7_1001400 and PF3D7_1001600) (5, 8). Using a local pairwise alignment algorithm, the two members of α/β-hydrolase family A are 41.4% identical (61.4% similar), and the two members of α/β-hydrolase family B are 53.3% identical (72.5% similar). However, comparisons between family A and B protein sequences reveal less than ~19% identity between the two families.

α/β-Hydrolase fold proteins are a diverse superfamily of enzymes, and despite low sequence similarity at the amino acid level, some distinguishing motifs can aid in the classification of various α/β-hydrolase families. To gain insight into the potential functions of the exported α/β-hydrolases, a PSI-BLAST pseudo-multiple-sequence alignment (comparing the protein of interest to the nonredundant protein data bank) was generated using the online Phyre2 server (30). The top five, unique, non-Apicomplexan hits (with lowest E values) for the P. falciparum α/β-hydrolase family A members have the highest similarity to proteins of the epoxide hydrolase family (Interpro IPRO00639; hereafter we refer to PF3D7_0301300 as PfEH1 [P. falciparum epoxide hydrolase 1] and PF3D7_1401300 as PfEH2), whereas α/β-hydrolase family B members had the highest similarity to the lysophospholipase/serine aminopeptidase family (Interpro IPRO22742; hereafter we refer to PF3D7_1001400 as PfXL1 [for P. falciparum exported lipase 1] and PF3D7_1001600 as PfXL2) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

PfEH1 and PfEH2 are exported from the parasite and are tethered to the erythrocyte cytoskeleton.

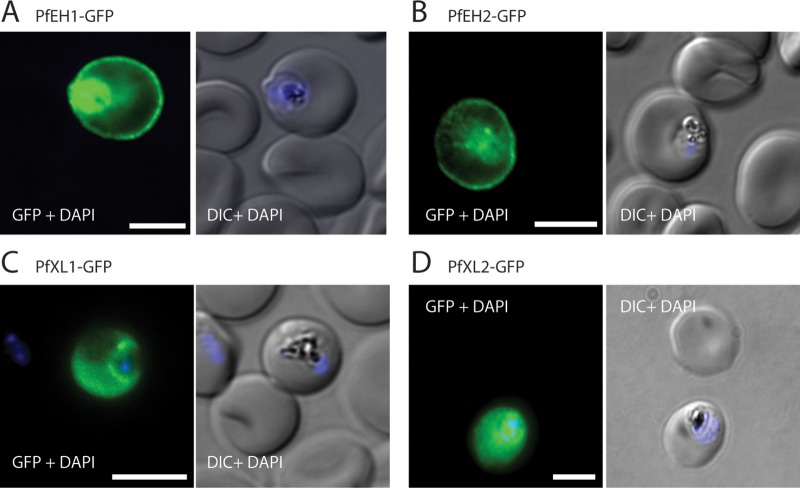

To investigate the export of the four PEXEL-containing α/β-hydrolases, we generated parasites ectopically expressing a C-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion of each α/β-hydrolase (see Fig. S1A and S1B in the supplemental material). For the two α/β-hydrolase family A members, fluorescence was observed at the periphery of the infected erythrocyte and within the parasite (Fig. 1A and B). In contrast, for the two family B members, fluorescence was diffuse throughout the cytosol of the infected RBC (Fig. 1C and D).

FIG 1 .

Four α/β-hydrolases are exported into the erythrocyte compartment. Immunofluorescence assay (IFA) of trophozoite/early schizont-stage parasites overexpressing GFP-tagged α/β-hydrolases. Parasites were fixed with paraformaldehyde/glutaraldehyde and stained with anti-GFP (green). The nuclei were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). (A) PfEH1-GFP, (B) PfEH2-GFP, (C) PfXL1-GFP, and (D) PfXL2-GFP. Expression was under control of the constitutive HSP86 promoter (see Fig. S1A and S1B in the supplemental material). The images are representative of at least three independent experiments. Bars = 5 µm. DIC, differential interference contrast.

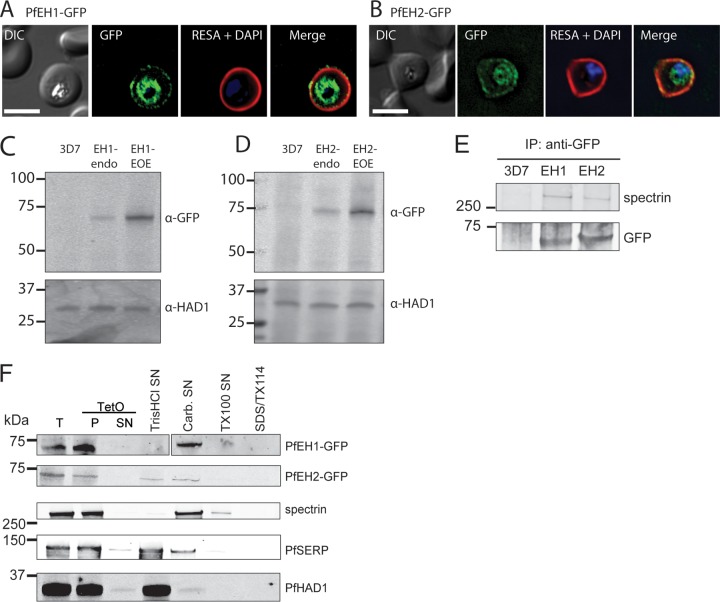

We chose to focus our study on the two putative epoxide hydrolases. We generated parasite integrants expressing the putative EH of interest fused to GFP, under control of the endogenous promoter (see Fig. S1C to S1F in the supplemental material). In asexual parasites, anti-GFP antibody detected PfEH1 and PfEH2 at the periphery of the infected erythrocyte and within the parasite (Fig. 2A and B). The fluorescence at the periphery colocalized with ring-exported surface antigen (RESA) (PF3D7_0102200), an exported protein that interacts with host spectrin at the RBC cytoskeleton (31). Expression from the endogenous locus was low, and by Western blotting, the endogenously tagged PfEH1-GFP or PfEH2-GFP parasites had fusion protein levels that were ~17 ± 5-fold (n = 4) and ~6 ± 2-fold (n = 4) lower than in the overexpression parasites used in Fig. 1 (Fig. 2C and D).

FIG 2 .

PfEH1 and PfEH2 interact with the erythrocyte cytoskeleton. IFA of paraformaldehyde/glutaraldehyde-fixed, trophozoite/early schizont-stage parasites expressing PfEH1-GFP (A) or PfEH2-GFP (B) under control of the respective endogenous promoter. The GFP-expressing parasites were costained with anti-RESA (red). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Bars = 5 µm. DIC, differential interference contrast. (C and D) Western blots of PfEH expression in trophozoite-stage parasites. PfEH proteins are not detected in 3D7 parent parasites, barely detected when GFP tagged at the endogenous locus (endo), and highly expressed in the episomal overexpression (EOE) lines. P. falciparum haloacid dehalogenase 1 (PfHAD1) is used as a loading control. α-GFP, anti-GFP antibody. (E) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of RBCs infected with the 3D7 parent line, PfEH1-GFP or PfEH2-GFP (EOE lines). Complexes were isolated with anti-GFP antibodies, and the final eluate was probed with anti-GFP antibody to confirm pulldown of the PfEH proteins and with human antispectrin antibody. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown to the left of the blots in panels C to E. (F) Sequential fractionation of the 3D7 parent line, PfEH1-GFP, or PfEH2-GFP (EOE lines). The RBC plasma membrane was permeabilized with tetanolysin O (TetO). The total (T) fraction, pellet (P) fraction, and supernatant (SN) fractions are shown in the three leftmost portion of the blots. The pellet fraction was then subjected, sequentially, to hypotonic lysis (Tris HCl) to release soluble parasitophorous vacuole (PV)/parasite/Maurer’s cleft contents, carbonate (Carb.) to release membrane fraction-associated contents, Triton X-100 (TX100) to release membrane contents, and the final pellet was solubilized in Triton X-114 (TX114)/SDS. P. falciparum serine-rich protein (PfSERP) is a soluble parasitophorous vacuole integrity marker, and PfHAD1 is a soluble parasite integrity marker.

The PfEH1/2-GFP parasites were used to detect potential interacting partners, which were isolated by pulldown using anti-GFP antibodies and identified using mass spectrometry (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). An enrichment of peptides was observed for α/β spectrin. A similar enrichment for spectrin was not observed in the 3D7 parent, or when PfXL-GFP proteins were used as bait, suggesting that the immunoprecipitation procedure was not nonspecifically pulling down cytoskeletal contents. Chaperones commonly isolated as contaminants (e.g., HSP70) were pulled down equally in all samples, while components of the export machinery (e.g., HSP101) were immunoprecipitated only in the α/β-hydrolase-GFP parasites.

The interaction of the PfEHs with spectrin was confirmed by Western blotting, whereby the GFP-tagged PfEH1/2 were pulled down with anti-GFP antibodies, and the resulting fraction was probed with an antispectrin antibody. Spectrin was present in the immunoprecipitate from GFP-tagged PfEH1/2 lines, but not in the 3D7 parent (Fig. 2E). Consistent with a cytoskeletal interaction, PfEH1 and PfEH2 were both present in the carbonate fraction of a differential solubility assay (Fig. 2F), along with spectrin. In both the immunoprecipitation and fractionation experiments, the size of the GFP-tagged PfEH1/2 protein corresponded to the processed form, after cleavage at the PEXEL motif. The results of the localization and fractionation experiments indicate that PfEH1 and PfEH2 are in close proximity to the erythrocyte cytoskeleton and membrane phospholipids.

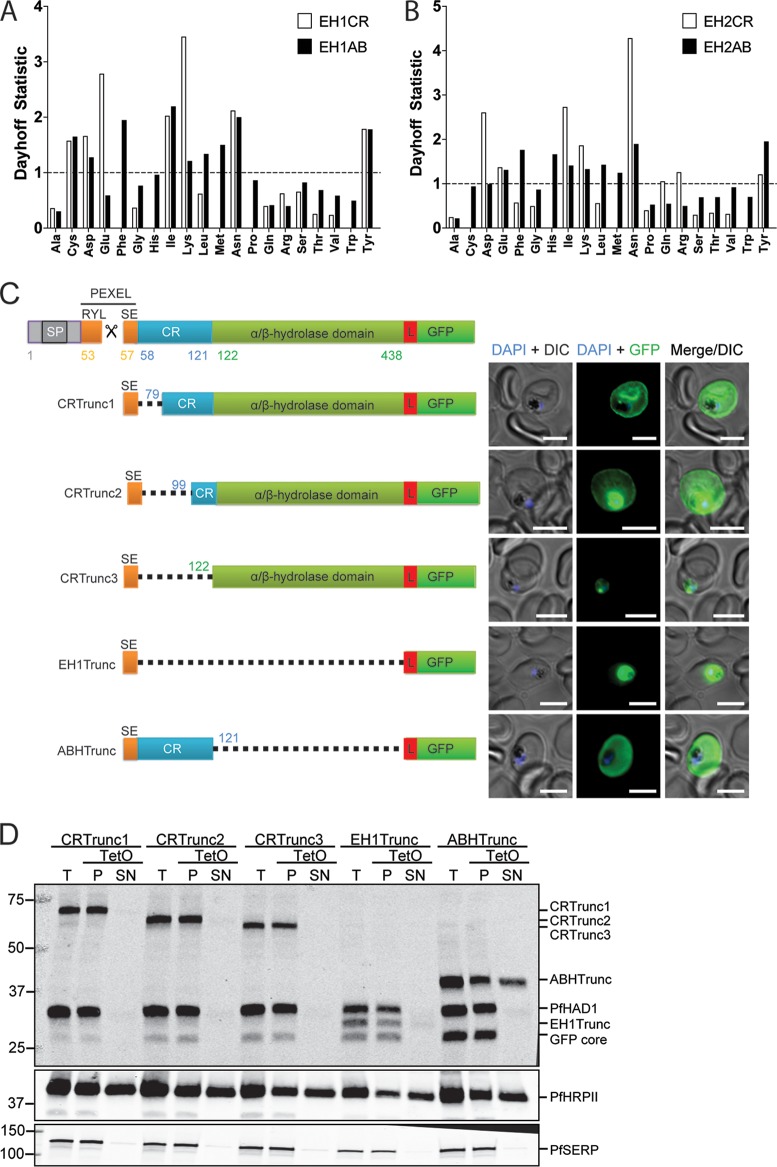

Spectrin has previously been identified as a major hub for localization of exported proteins (32), including P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) (33), PfEMP3 (34, 35), RESA (31), and knob-associated histidine-rich protein (KAHRP) (36). Spectrin is known to interact with other RBC cytoskeleton members, and also lipids, via charged regions (37–39). We examined the amino acid content of the PfEH proteins and identified a highly charged region in the N terminus of the mature protein dominated by charged Lys and Glu residues in PfEH1 and Asp (and neutral Asn) residues in PfEH2 (Fig. 3A and B). We hypothesized that this charged region (CR) may be important for cytoskeletal tethering, so for PfEH1, this region was truncated to assess the role of the CR in PfEH1 localization (Fig. 3C). Each construct contains the hydrophobic signal peptide and PEXEL sequence fused to the protein domains of interest, followed by a 10-amino-acid linker sequence (PRPGAAHYAA; used previously [40]), and the GFP reporter. When the 64-amino-acid CR was truncated by 22 and 42 amino acids, the reporter was still seen to be exported to the RBC periphery (by both microscopy and tetanolysin O fractionation; Fig. 3C and D), similar to what has been seen with full-length reporter (Fig. 1A and 2D). However, complete truncation of the CR abolished export (Fig. 3C and D), suggesting that the CR contains export-relevant information. Fusing the signal peptide/PEXEL directly to the GFP reporter did not permit export (although as seen previously, the linker sequence may not be sufficient to spatially separate the PEXEL and tightly folded GFP [41–43]). Additionally, when the α/β-hydrolase domain was truncated, the CR region was sufficient to promote export of the reporter construct (Fig. 3C). However, the protein was no longer tethered at the RBC periphery and was found in the tetanolysin O-soluble fraction (Fig. 3D). This indicates that the α/β-hydrolase domain contains information relevant for the tethering of PfEH1 to the cytoskeleton.

FIG 3 .

The charged region (CR) of PfEH1 is required for export, and the α/β-hydrolase region is required for cytoskeletal tethering. (A) The amino acid composition of the first 66 residues of mature PfEH1 (EH1CR) was compared to the last 315 residues (EH1AB) using PEPSTATS. The Dayhoff statistic compares the relative occurrence of the amino acid per 1,000 residues to the theoretical Dayhoff statistic for protein composition. A value of 1.0 represents typical frequency. (B) The amino acid composition of the first 49 residues of mature PfEH2 (EH2CR) was compared to the last 333 residues (EH2AB). (C) Schematic representing the PfEH1 truncation (Trunc) constructs. Each construct contains the N-terminal signal sequence and PEXEL motif, as well as a linker region (L) before the reporter GFP. SP, signal peptide. ABH, α/β-hydrolase. (Right) Images from IFA of paraformaldehyde/glutaraldehyde-fixed, trophozoite/early schizont-stage parasites expressing the truncated PfEH1 under control of the HSP86 promoter. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Bars = 5 µm. DIC, differential interference contrast. (D) Fractionation of the PfEH1-GFP truncation lines with tetanolysin O (TetO). The top blot is probed with both anti-GFP and anti-PfHAD1, a soluble parasite integrity marker. P. falciparum histidine-rich protein II (PfHRPII) is a soluble exported protein, and PfSERP is a soluble parasitophorous vacuole integrity marker. Lanes: T, total; P, pellet; SN, supernatant. The blots are representative of two or three independent fractionations for each cell line.

PfEH1 and PfEH2 hydrolyze epoxides, including physiologically relevant signaling lipids.

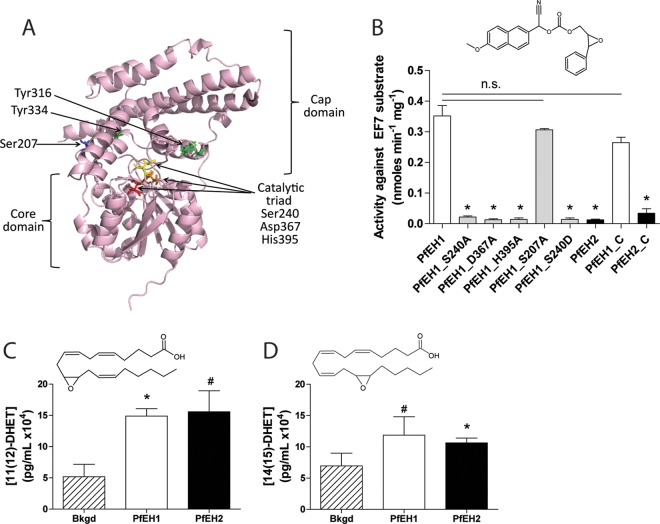

EHs are distinguished from other α/β-hydrolase fold proteins on the basis of several key motifs (44, 45)—an HGXP motif (part of the oxyanion hole), two tyrosines in the cap domain (functioning in substrate recognition and positioning for the ring-opening reaction), and a GXSmXS/T motif (unknown function) (46). EHs also have a well-studied catalytic triad (nucleophile-acid-base) (44, 45). Amino acid alignments, comparing the sequences of PfEH1/2, PfXL1/2, and the four human EHs, revealed that for PfEH1 and PfEH2, the oxyanion hole motif and GXSmXS/T motif are mostly conserved, and the ring-opening tyrosines (potentially Y316/Y334 in PfEH1 and Y318/Y343 in PfEH2) and catalytic triad are easily identifiable (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). A major difference is that PfEH1 and PfEH2 contain a serine (S240 in PfEH1 and S249 in PfEH2) in the position where other EHs contain a catalytic aspartate (44, 45).

To inform recombinant protein experiments, a model of PfEH1 was generated. The cap domain and core α/β-hydrolase fold domains are identifiable, and the active site residues are clustered near several putative ring-opening tyrosines (Fig. 4A). Robust expression of N-terminal poly(His)-tagged PfEH1 and PfEH2, and of several PfEH1 mutants, was achieved in E. coli. The activity of the recombinant enzymes was investigated using the EH reporter substrate epoxy fluor 7 (EF7 [47]). Purified PfEH1 hydrolyzed EF7; however, PfEH2 had very low activity against this substrate (Fig. 4B). PfEH1 activity was significantly diminished when mutations were made in the active site (S240A, D367A, and H395A), but not when a serine distal to the active site (in the cap domain) was mutated (S207A) (Fig. 4B). We attempted to make the PfEH1 active site more closely resemble the active site of human EHs by mutating the catalytic serine to an aspartate (S240D). However, this mutation also significantly reduced the ability of the recombinant enzyme to hydrolyze the EF7 substrate (Fig. 4B). C-terminal poly(His)-tagged PfEH1 and PfEH2 were also expressed and purified, and these enzymes displayed activity that was not significantly different from the activity of the N-terminally tagged proteins.

FIG 4 .

Activity of recombinantly expressed PfEH1 and PfEH2 in in vitro epoxide hydrolysis assays and identification of key catalytic residues in PfEH1. (A) Model of PfEH1 (created in Robetta [88], using the structures of Pseudomonas putida α/β-hydrolase [PDB accession no. 1ZOI] and human soluble epoxide hydrolase [HsEH2] [PDB accession no. 1S8O]). The variable cap domain and conserved α/β-hydrolase domains are annotated, and key residues are highlighted in contrasting color and shown in stick format. (B) PfEH1, PfEH2, and several PfEH1 mutants were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). The PfEH proteins were purified by affinity and size exclusion chromatography (two to nine independent inductions/purifications for each condition). Measurement of the fluorescent product (6-methoxy-2-napthaldehyde) generated after hydrolysis of the substrate epoxy fluor 7 (EF7) (structure shown above the graph). All proteins were N-terminally His tagged, except for PfEH1_C and PfEH2_C, which are C-terminally His tagged. Values are means plus SEMs (error bars). Values that are statistically significantly different from the value for PfEH1 (P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posttest) are indicated with an asterisk. Values that are not statistically significantly different (n.s.) are also indicated by bars. (C and D) Recombinant PfEH1 and PfEH2 proteins were incubated with 11(12)-EET (structure shown above the graph in panel C) or 14(15)-EET (structure shown above the graph in panel D). Production of the respective diol was measured using ELISA (n = 2 to 4, using protein purified from two independent inductions). Values that are statistically significantly different from background (Bkgd) hydrolysis by unpaired t test are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; #, P < 0.08. For the 11(12)-EET substrate, the increase in hydrolysis was significant for PfEH1 (P = 0.027; n = 4) but did not reach significance for PfEH2 (P = 0.064; n = 4). For the 14(15)-EET substrate, the increase in hydrolysis was significant for PfEH2 (P = 0.043; n = 3) but did not reach significance for PfEH2 (P = 0.077; n = 3).

To examine the ability of the recombinant enzyme to hydrolyze physiological substrates, we incubated the recombinant PfEH1 or PfEH2 with 14(15)-EET or 11(12)-EET and used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect formation of the respective diol products 14(15)-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid [14(15)DHET] or 11(12)-DHET. Both recombinant PfEH1 and PfEH2 enzymes increased the formation of the diol product above levels generated by spontaneous hydrolysis (Fig. 4C and D).

PfEH1 and PfEH2 can be disrupted in vitro.

To assess the in vitro importance of PfEH1 and PfEH2, parasite lines were generated in which either individual locus was disrupted by double-crossover recombination, with insertion of the yeast dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (yDHODH) selection cassette (strategy in Fig. S3A to S3D in the supplemental material). Neither single-knockout parasite line displayed any obvious morphological changes or significant alteration of growth rate compared to the 3D7 parental line (Fig. S3E). A double-knockout line was created by knocking out PfEH1 and -2 sequentially using orthogonal drug selection cassettes. Southern blotting confirmed the successful generation of PfEH1/2 double-knockout clones (Fig. 5A and B). As was the case for the single knockouts, the double knockout also had no observable morphological changes or alteration in growth rate (Fig. 5C). PfEH1 and -2 do not appear to be required for growth in culture.

FIG 5 .

PfEH1 and PfEH2 can be knocked out in cultured parasites. (A and B) Southern blots of digested genomic DNA from the parent 3D7 line, vector, and double-knockout clones. Analysis at both the PfEH1 (A) and PfEH2 (B) loci demonstrate the simultaneous disruption of both genes in clones 3G and 11C, but not in clone 1E. The black arrows to the right of the blots indicate the expected size for correct integration, and the asterisk indicates a band of unknown origin. In panel B, the pUF-TK_PfEH2 vector [Vector (#)] was used instead of pCC1_PfEH2 (called pABH-DKO in reference 89). The schematic representations of the integration events are outlined in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. (C) Growth of the 3D7 parent line and the two double-knockout (DKO) clones over 4 days. No differences were observed in growth between these three cell lines, with this graph representative of data from three independent experiments. The doubling times are 1.14 ± 0.12 days for the 3D7 parent, 1.16 ± 0.10 days for double-knockout clone 3G, and 1.26 ± 0.12 days for double-knockout clone 11C (not significantly different [P > 0.53] using pairwise t tests; n = 3 for each). The smooth curve is the fitted exponential growth equation. (D) Transcript levels of PfEH1 and PfEH2 in unsynchronized 3D7 laboratory strain compared to field isolates from malaria-infected pregnant women or malaria-infected children. The data shown were taken from Vignali et al. (48). (E) Normalized expression of PfEH1 or PfEH2 in two laboratory strains (Saint Louis STL-3D7 or MRA-3D7) and three laboratory-adapted field isolates from Cambodia (MRA-1237, MRA-1238, and MRA-1241). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using probes against PfEH1 and PfEH2, with actin as a reference gene. Values are normalized to the average expression in STL-3D7 and MRA-3D7. Data were calculated from three independent RNA preparations (means plus SEMs [error bars]) and are not significantly different using a two-way ANOVA (P > 0.05).

Previously reported expression profiling revealed that field isolates (with minimal in vitro culturing) have increased expression levels of PfEH1 and PfEH2 genes (5- to 10-fold; data from genome-wide RNA analysis in Vignali et al. [48]) (Fig. 5D). This suggested that expression of PfEH1/2 may be beneficial in vivo. We examined three field isolates that had been adapted to in vitro culture through cryopreservation/thawing three times before analysis (49, 50). After a limited number of additional cryopreservation/thawing steps in our laboratory, we isolated RNA from these parasites and examined the relative expression of PfEH1 and PfEH2 in these culture-adapted field isolates compared to two 3D7 laboratory lines. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) demonstrated that there was no significant difference in expression of either PfEH gene in these field lines adapted to in vitro culture (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that the ectopic overexpression constructs of PfEH1/2 (Fig. 1A and B) may be more representative of in vivo expression levels (i.e., high expression), whereas laboratory-adapted lines have reduced requirement to express PfEH1/2 (i.e., low expression).

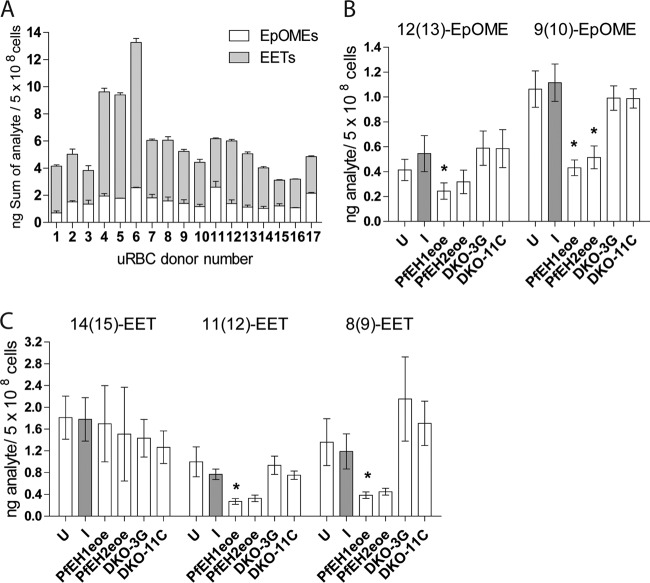

Overexpression of PfEH1 or PfEH2 results in a reduction in erythrocyte epoxide signaling lipids.

To explore the effect of altering PfEH1 or PfEH2 expression on the composition of erythrocyte epoxide signaling lipids, fatty acid preparations were isolated from the phospholipid fraction of erythrocytes infected with the PfEH1/2 double-knockout clones (from Fig. 5) or the PfEH1- or PfEH2-overexpressing lines (from Fig. 1). These lipid preparations were analyzed using a targeted liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) approach to measure three EET regioisomers [14(15)-EET, 11(12)-EET, and 8(9)-EET] and two EpOME regioisomers [12(13)-EpOME and 9(10)-EpOME]. It has been previously reported that the concentration of EETs in erythrocytes varies significantly between individual blood donors (by 2- to 3-fold) (14). We also observed a 2- to 3-fold variation in RBC epoxy fatty acid content between blood donors used over the course of this study (Fig. 6A). Therefore, it was essential to pair all analyses and use blood from the same donor/donor pool for culture of a parasite line within an experiment. When RBCs were infected with the 3D7 parasite line, there were no significant differences in any of the five analytes measured compared to the control uninfected RBCs (Fig. 6B and C). There were also no significant differences in epoxy fatty acid content comparing infection with the 3D7 parent to infection with the PfEH1/2 double-knockout clones (Fig. 6B and C). However, in the PfEH1- or PfEH2-overexpressing lines, compared to the 3D7 parent line, there was a substantial reduction of several epoxy signaling lipids. These results are consistent with PfEH1 and PfEH2 altering the concentration of epoxy signaling lipids within the infected erythrocytes.

FIG 6 .

LC/MS/MS measurement of epoxide-containing fatty acids in phospholipid preparations from parasitized RBCs. Internal standards 5(6)-EET-d11, 8(9)-EET-d11, 11(12)-EET-d11, 14(15)-EET-d11, and 9(10)-EpOME-d4 were added to each sample, phospholipids were extracted with 2:1 CHCl3−CH3OH plus 0.1 mM triphenylphosphine, and fatty acids were released using phospholipase A2. Four-point calibration curves were generated using the deuterated standards to quantify the epoxide analytes. (A) Sum of 8(9)-EET, 11(12)-EET, 14(15)-EET, 9(10)-EpOME, and 12(13)-EpOME in uninfected RBCs (uRBC). Samples were run twice, and the error bars depict range/2. (B and C) 9(10)-EpOME and 12(13)-EpOME (B) and 8(9)-EET, 11(12)-EET, and 14(15)-EET (C) concentrations in phospholipids of uninfected RBCs (U) and RBCs infected with 3D7 parent (I), PfEH1-GFP (PfEH1eoe), PfEH2-GFP (PfEH2eoe), and PfEH1 PfEH2 double-knockout (DKO) clones 3G and 11C. The values shown are calculated from 3 to 9 independent phospholipid preparations per condition (mean ± SEM). Values that are statistically significantly different from the value for infected RBCs (P < 0.05 by paired t tests) are indicated by an asterisk. For PfEH1, there was a significant reduction in 12(13)-EpOME (P = 0.049; n = 4), 9(10)-EpOME (P = 0.043; n = 4), 11(12)-EET (P = 0.0154; n = 4), and 8(9)-EET (P = 0.034; n = 4), while for PfEH2, several compounds showed reductions, but the decrease reached statistical significance only for the 9(10)-EpOME analyte (P = 0.028; n = 4).

DISCUSSION

The physiological functions of the several hundred P. falciparum proteins exported into the host cell remain poorly characterized. In this study, we show that four α/β-hydrolases are exported into the RBC and that two of these, PfEH1 and PfEH2, have epoxide hydrolase activity and are capable of hydrolyzing bioactive RBC lipid epoxides to less active diols. We propose that the malaria parasite can reduce lipid epoxide signaling of the host RBC, a disruption that may lead to perturbed vascular signaling and inflammation.

In circulating RBCs, stimuli, such as shear stress or stimulation of the purinergic P2X7 receptors by ATP, activate phospholipase A2, which releases EETs from their esterified form in membrane phospholipids into a soluble free fatty acid form in the cytosol (16, 17). Following de-esterification, the soluble EETs are then released from the RBCs in a process requiring the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), pannexin-1, and the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) (17, 51). Infection with P. falciparum is known to activate several RBC ATP release pathways, including VDAC (52–54). Therefore, it is possible that EET de-esterification and release is activated during P. falciparum infection. The observed localization of PfEH1 and PfEH2 at the periphery of the infected RBC would facilitate the rapid metabolism of released epoxy fatty acids.

Aside from proximity to substrate, the functional significance of the observed interaction of the PfEHs with the RBC cytoskeleton is unknown. Further work is necessary to demonstrate a direct interaction between the PfEHs and spectrin (or another cytoskeletal component) and to investigate whether the PfEHs interact with other malarial proteins at the cytoskeleton. Our analyses of truncation mutants of PfEH1 suggested that the α/β-hydrolase domain, and not the highly charged mature N-terminal region, is essential for the cytoskeletal interaction. Other exported proteins, where there is direct evidence for their interaction with the cytoskeleton, also contain charged regions or charged repeats, including KAHRP (32, 33, 36) and lysine-rich membrane-associated PHISTb protein (LYMP) (55, 56); however, the function of their charged regions is unstudied. The highly charged N-terminal region in PfEH1 was necessary to facilitate export. Three different charged PfEH1 mature N termini (full-length/ABHTrunc, CRTrunc1, and CRTrunc2) permitted export into the RBC, but the two truncations without the charged N termini (CRTrunc3 and EH1Trunc) did not. Charge differences between the N and C termini of exported proteins were previously proposed to contribute to the export process (57, 58); however, it was subsequently shown that scrambling the N-terminal charged regions reduces export (42), suggesting that the sequence was also a driving factor. It is also possible that for the two truncations that were not exported, there was a steric block along the secretory pathway. The requirement to separate the PEXEL motif from the tightly folded GFP core, in a sequence-independent manner, has been described (41), with the hypothesis being that if the N-terminal signal is too short, it cannot be efficiently recognized and/or unfolded by chaperones/export machinery in the parasitophorous vacuole. It is possible that the export signal is too tightly associated with GFP (for EH1Trunc) or with the structured α/β-hydrolase domain (for CRTrunc3) to be recognized for successful export. Further dissection of the PfEH1 (and PfEH2) protein is necessary to clarify the requirements for export and the requirements for cytoskeletal interaction in more detail.

In this study, we demonstrate that PfEHs were able to hydrolyze epoxides in in vitro experiments with recombinantly expressed PfEHs and also in parasite-infected RBCs. In the assays reported here, PfEH1 and PfEH2 behaved similarly (the exception being that PfEH2 did not hydrolyze the EF7 fluorescent reporter substrate, though EHs with poor activity against nonphysiological fluorescent reporters but higher activity against endogenous substrates have been reported [59]). If the localization and ability to hydrolyze EETs/EpOMEs are similar, then it is unclear why P. falciparum would express two EHs. One possibility is that the two enzymes are not redundant, as they have different substrate selectivities. Alternatively, they may be important at different stages of the intraerythrocytic life cycle. Consistent with this hypothesis, previous studies indicated that PfEH2 may be upregulated in the gametocyte (sexual) stage (5, 60). PfEHs may also be important in the parasite mosquito stages as EETs and EpOMEs are taken up in the mosquito blood meal. Mosquito EHs can reduce EET/EpOME levels (61, 62), and modulating EH activity alters the mosquito immune response, which may alter parasite viability (63). Both PfEH1 and PfEH2 are upregulated in field isolates (48) (Fig. 5D); therefore, the PfEH-overexpressing lines created in this study may be more physiologically relevant to study EH function compared to laboratory-adapted lines, such as 3D7, which expresses very low levels of EH enzymes and behaved like our PfEH1 double-knockout line.

One challenge in studying epoxide-containing signaling lipids is the instability of these metabolites. The level of epoxy fatty acids in our cultured RBCs (~10 ng EETs/109 RBCs) was lower than previously reported for “fresh” RBCs (~33 ng EETs/109 RBCs) (14). Goulitquer and colleagues reported EET levels to be quite unstable, with a rapid loss of approximately 20 to 30% in the first hour after the blood draw, though the decrease is slower at 4°C (14). Our parasites are cultured at 37°C for several days, likely leading to the decreased level of the epoxy fatty acids reported here. Examination of epoxy fatty acid profiles in freshly drawn blood from healthy individuals compared to patients infected with P. falciparum would provide further evidence of the significance of PfEHs in altering RBC physiology. A previous report examined the vasoactivity of RBCs from P. falciparum malaria-infected patients in Benin and found increased contractile responses in the malaria-infected RBCs compared to uninfected samples (64). This result is consistent with a decrease in vasodilatory signals (e.g., EETs) upon malaria infection. Interestingly, the four α/β-hydrolases are part of a “greatly expanded exportome” found in P. falciparum (and P. reichenowi) (8). These species-specific exported proteins are thought to be involved in the trafficking and display of the virulence ligand PfEMP1 (8). It is possible that the PfEHs contribute to the vascular inflammation and display of PfEMP1-compatible adhesins, although this hypothesis requires experimental investigation.

P. falciparum is not the only pathogen to use an EH to alter host function. EH activity has been extensively studied in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium that causes opportunistic pulmonary infections, particularly in some cystic fibrosis cases. P. aeruginosa secretes the “CFTR inhibitory factor,” or Cif EH (65), and the Cif EH enters into the airway epithelial cells. Although Cif has classical EH activity (66, 67), it also inhibits CFTR endocytic recycling (66, 68), leading to a decrease in apical CFTR levels, exacerbating cystic fibrosis symptoms. The Cif EH has a noncanonical active site, including having a glycine instead of a proline in the HGxP motif (69). Differences in reaction mechanism (compared to the well-studied human soluble EH [sEH]) may be necessary to facilitate the non-EH Cif activities. The PfEHs also have a noncanonical active site, as they lack the aspartate nucleophile found in characterized EHs. It has previously been hypothesized that an EH using a serine nucleophile would result in an “overly stable reaction intermediate” (70); however, the nucleophile alone is not the sole residue driving EH activity (71). Solving the crystal structure of PfEH1 or PfEH2 would allow an examination of the active site features. The full range of PfEH substrates and functions requires further characterization.

It is possible that the PfEHs, like Cif, may have other non-EH activities and that these activities may require a serine nucleophile (a residue facilitating an incredibly diverse array of at least 17 α/β-hydrolase enzymatic activities [72]). Consistent with this, it was recently described that PfEH2 also possesses an S33 class proline aminopeptidase activity (73). The peptidase activity of PfEH2 is low (reported Km of 403 µM and kcat/Km of ~28 M−1 s−1 [73]) compared to other characterized proline aminopeptidases (74, 75). The physiological substrate(s) and relevance of this activity are yet to be determined. Epoxide hydrolases are common nonpeptidase homologues of the S33 class peptidases (76, 77), due to the broad hidden Markov matrices used to identify peptidase members (78). Functional promiscuity in the α/β-hydrolase family has been reported (79), and investigation into whether the PfEHs possess multiple activities requires further study. Interestingly, in the study on the proline aminopeptidase of PfEH2, the infected RBC (iRBC) membrane of the PfEH2 knockout parasites was more elastic than that of the parent parasites (73), which may reflect a change in the phospholipid composition of these parasites.

Pharmacological inhibition of PfEHs in vivo merits further investigation. Promoting a “quiescent” endothelium and normal vasoreactivity would be disadvantageous to the parasite, as fewer endothelial adhesins displayed would result in less cytoadherence and increased splenic clearance of parasitized RBCs. Multiple EH inhibitors are in development (67, 80, 81), with several currently in clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier [ID] NCT00847899, NCT01762774, and NCT02006537). If epoxy signaling lipids are important for reducing P. falciparum virulence in vivo, there is also a possibility that these inhibitors may be repurposed as antimalarials. Aside from modulating the host EH enzymes, it may also be possible to directly target the PfEHs, and work in this area is ongoing. Understanding the regulation of RBC epoxide-containing signaling lipids by parasite EHs will pave the way for the identification and validation of new drug targets within this pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

See supplemental material for full details.

P. falciparum culture.

P. falciparum line 3D7 was cultured at 2% hematocrit in O+ erythrocytes in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) Albumax II (40). Cultures were grown statically in 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2. As required, cultures were synchronized with 5% (wt/vol) sorbitol (82). Parasites generated in this study include C-terminal GFP-tagged PfEH1 or PfEH2 (expression under control of the endogenous or heat shock protein 86 [HSP86] promoters; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), C-terminal GFP-tagged PfXL1 or PfXL2 (under control of the HSP86 promoter; Fig. S1), and single- or double-knockout parasites of PfEH1 and PfEH2 (Fig. S3). Infected erythrocytes (mid-stage trophozoites) were enriched to >95% parasitemia using LD columns on a QuadroMACS separator.

Immunofluorescence assay, cell fractionation, immunoprecipitation, mass spectrometry, and Western blotting.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) (83, 84) and sequential permeabilization of enriched, infected erythrocyte compartments (42) was performed as previously described. For immunoprecipitation, parasite lysates were incubated with protein A Dynabeads (Molecular Probes) and nutated with rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (ab6556; Abcam) (2 to 5 µg) for 16 h (4°C).

Epoxide hydrolase activity assays.

Epoxy fluor 7 (EF7), EETs, and EpOMEs were from Cayman Chemicals. Fluorescence/absorbance was monitored using an EnVision Multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer). EH activity was measured using the EF7 substrate (47) in a 200-µl reaction mixture containing 5 µM EF7 and 10-µg recombinant enzyme in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (expressed in E. coli as previously described [85]). Diol formation (measuring 6-methoxy-2-naphthaldehyde production) was quantified by measuring fluorescence (excitation at 340 nm and emission at 450 nm). Calculation of the initial (linear) rates of substrate hydrolysis was determined using GraphPad Prism software (v5). EH activity against the 11(12)-EET and 14(15)-EET regioisomers was measured using the 11(12)- or 14(15)-DHET ELISA kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Detroit R&D), with some modifications. Reaction mixtures (100 µl) contained 6 or 12 µM EET and 100 µg EH recombinant enzyme in PBS and were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h. Sample buffer (900 µl) was added to the reaction mixture, and 100 µl was loaded onto the ELISA wells in duplicate. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Gene expression by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Strains used were P. falciparum (“Saint Louis” 3D7 [86] or “MRA-102” 3D7 [obtained through BEI Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH: contributed by D. J. Carucci/A. Craig]) and Cambodian field isolates (49, 50) (MRA-1237, -1238, and -1241 [strains IPC 3663, 4884, and 4912, respectively, obtained through BEI Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH: contributed by D. Menard]). Tightly synchronized parasites were saponin isolated (0.05% saponin in PBS; 5 min, room temperature) and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase treatment (15 min, room temperature). One-step RT-PCR was performed using the TaqMan fast virus one-step RT-PCR master mix (Life Technologies) using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast real-time PCR system. Primer sets and probes were designed (IDT PrimeTime quantitative PCR [qPCR] assay) for PfEH1, PfEH2, and actin (PF3D7_1246200) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The relative expression levels of PfEH1 and PfEH2 were calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method (87) using actin as a reference control gene. Normalized gene expression was calculated as 2−ΔΔCT where ΔCT = CT (actin) − CT (PfEH) where CT (actin) is the threshold cycle of actin and ΔΔCT = ΔCT (average STL/MRA 3D7) − ΔCT (Cambodian isolate).

Analysis of EET and EpOME metabolites by LC/MS/MS.

Lipid mass spectrometry was performed at the Metabolomics Facility at Washington University (P30 DK020579). Enriched (>95% parasitemia, QuadroMACS), trophozoite-stage infected RBCs (5 × 108 cells) were washed three times in PBS, resuspended in 200-µl water, and internal standards were added [5 ng each of 5(6)-EET-d11, 8(9)-EET-d11, 11(12)-EET-d11, 14(15)-EET-d11, and 9(10)-EpOME-d4]. Phospholipids were extracted twice using 2:1 CHCl3-CH3OH with 0.1 mM triphenylphosphine, hydrolyzed using phospholipase A2, and extracted twice with ethyl acetate as described previously (13). The dried extract was stored at −80°C until analysis, when it was suspended in 100 µl of methanol. After removing particulates, 10 µl of the supernatant were injected onto an online trapping liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) system. This system consists of a Leap PAL autosampler, four Shimadzu high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) 20AD pumps, and an API-4000 quadrupole mass spectrometer. Two types of Thermo-Keystone C18 betasil trapping column (2 by 10 mm; 5 µm) and C18 betasil analytical column (2 by 100 mm; 3 µm) were used for the analyses. The mobile phases were 1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile for the trapping column and 10 mM ammonium formate in water and acetonitrile for the analytical column. Solvent gradient programs were used for trapping and analytical runs. Negative ion multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was used to detect all analyte signals. For quantification of all analytes, four point calibration standards of all analytes were prepared in the presence of the deuterated internal standards and were injected onto the system for calibration curves. Analyst 1.5.2 version software was used for operation and quantification.

Statistical analyses.

Data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEMs). Statistical comparisons were made using a t test (paired/unpaired as indicated), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s posttest. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism v 5.01.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Generation of the GFP-tagged lines. (A) Schematic representation of the pEOE construct used to overexpress the protein of interest. The vector contains the human dihydrofolate reductase (hDHFR) positive-selection cassette, with selected parasites expressing the gene of interest under the strong, constitutive hsp86 promoter. (B) Schematic representation of the pTEOE construct used to overexpress the protein of interest via transposase-mediated integration. The vector contains the piggyBac element containing inverted terminal repeats (ITR) (90) and the hDHFR positive-selection cassette. The pHTH vector contains a cassette for transient expression of the piggyBac transposase (90), facilitating genomic integration of the pTEOE sequence, leading to stable expression of the gene of interest under the strong, constitutive hsp86 promoter. (C and E) Schema outlining the strategy for replacement of the 3′ region of the gene of interest by single-crossover homologous recombination. The pPM2GT vector (40) was used to append GFP to the 3′ end of the gene of interest, with positive selection mediated by the hDHFR selection cassette. The restriction digestion sites and the resulting expected sizes of DNA fragments that were utilized to characterize the locus by Southern blot analysis are labeled, with the probe represented by an orange bar. (D and F) Southern blots of digested genomic DNA from the 3D7 parent parasite line, vector, and tagged clones, showing correct integration of the GFP tag. Arrows indicate the expected size for correct integration, and asterisks indicate bands of unknown origin. In both PfEH1- and PfEH2-GFP lines, the plasmid band remains present, indicating integration of a concatemerized plasmid. Download

Amino acid alignment of PfEH1 and PfEH2 compared to known EH enzymes. Clustal Omega alignment of PfEH1, PfEH2, PfXL1, and PfXL2 with the equivalent regions in the four human EHs (Homo sapiens EHs [HsEHs]) (HsEH1, GenBank accession no. NP_001970.2; HsEH2, GenBank accession no. AAC41694.1; HsEH3,GenBank accession no. AAI15003.1; HsEH4, GenBank accession no.NP_775838.3). HsEH1 is the microsomal EH (HsEHm), and HsEH2 is the soluble EH (HsEhs). Identical residues are colored black, and functionally conserved residues are colored gray. The regions aligned represent the putative (i) oxyanion hole motif, (ii) GxGxS/T motif of unknown function, (iii) catalytic nucleophile, (iv) catalytic acid residue, and (v) catalytic base residue. Download

Generation of PfEH1 and PfEH2 single-knockout lines. (A, C, and F) Schema outlining the strategy for disruption of the gene of interest by double-crossover homologous recombination. The pUF-TK vector contains the yDHODH cassette for positive selection and the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (TK) cassette for negative selection. The pCC-1 vector contains the hDHFR cassette for positive selection and the yeast cytosine deaminase and uridyl phosphoribosyl transferase cassette for negative selection. The restriction digestion sites and the resulting expected sizes of DNA fragments that were utilized to characterize the locus by Southern blot analysis are labeled, with the probe represented by an orange bar. (B, D, and G) Southern blots (from panels A, D, and F, respectively) of digested genomic DNA from the 3D7 parent parasite line, vector, and knockout clones, showing correct disruption of PfEH1 or PfEH2. Arrows indicate the expected size for correct integration, and asterisks indicate bands of unknown origin. (E and H) Growth of the relevant 3D7 parent and the single-knockout clones over 6 days. No differences were observed in growth between these knockout lines and 3D7 parents, with graphs representative of data from three independent experiments. The smooth curve is the fitted exponential growth equation. Panels F to H show data for a preliminary knockout of PfEH2 (at the stage of a nonclonal pool subjected once to positive and negative selection; provided by M. Klemba) which was previously published (89), generated using a vector containing the human dihydrofolate reductase cassette. This population was used to complete the generation of a second PfEH2 clonal knockout. To create the double-knockout line, the PfEH2 knockout (clone 11F) was transfected with the PfEH1 knockout vector containing the yDHODH selection cassette. Download

InterPro domain information for the top five non-Apicomplexan hits from a PSI-BLAST pseudo-multiple-sequence alignment (comparing the P. falciparum [Pf] α/β-hydrolase sequence to a nonredundant protein data bank) generated using Phyre2 (30).

Putative interacting partners of PfEH1 and PfEH2 identified using mass spectrometry. GFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated (using anti-GFP polyclonal antibody) from PfEH1-, PfEH2-, PfXL1-, PfXL2-GFP-tagged cultures or the 3D7 parent line, and the resulting proteins analyzed by mass spectrometry. Values are the numbers of unique peptide hits. The peptide counts for spectrin are shown in bold type. ND, no peptides detected.

Oligonucleotides used in this study. Restriction sites are underlined, InFusion overhangs are italicized, stop codons are shown in bold type, and mutations are shown in lowercase type. All oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies.

Supplemental Materials and Methods. Download

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Anders (La Trobe University) for anti-RESA antibody, D. Taylor (University of Hawaii) for the anti-PfHRPII antibody, A. Odom (Washington University School of Medicine) for the anti-PfHAD1 antibody, J. Przyborski and K. Lingelbach (University of Marburg) for anti-SERP antibody, M. Klemba (Virginia Tech) for the ABH-DKO parasite pool, A. Vaidya (Drexel University College of Medicine) for DSM-1 and Jacobus Pharmaceutical Company Inc. for WR-92210. We thank H. Fujiwara and D. Scherrer for mass spectrometry performed in the Metabolomics Facility at Washington University. We thank the ‘FingerPrints’ Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Facility at the University of Dundee. We thank B. Vaupel, A. Oksman, and M. Lai for technical assistance and E. Istvan, P. Sigala, J. Beck, P. Pal, and J. Mallari for advice and suggestions.

N.J.S. and V.K.D. performed experiments. N.J.S. and D.E.G. designed and interpreted experiments. N.J.S. and D.E.G. wrote the manuscript.

N.J.S. acknowledges funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Overseas Biomedical Fellowship 1072217). D.E.G. acknowledges funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The Metabolomics Facility at Washington University is supported by P30 DK020579.

Footnotes

Citation Spillman NJ, Dalmia VK, Goldberg DE. 2016. Exported epoxide hydrolases modulate erythrocyte vasoactive lipids during Plasmodium falciparum infection. mBio 7(5):e01538-16. doi:10.1128/mBio.01538-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boddey JA, Cowman AF. 2013. Plasmodium nesting: remaking the erythrocyte from the inside out. Annu Rev Microbiol 67:243–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillman NJ, Beck JR, Goldberg DE. 2015. Protein export into malaria parasite-infected erythrocytes: mechanisms and functional consequences. Annu Rev Biochem 84:813–841. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maier AG, Rug M, O’Neill MT, Brown M, Chakravorty S, Szestak T, Chesson J, Wu Y, Hughes K, Coppel RL, Newbold C, Beeson JG, Craig A, Crabb BS, Cowman AF. 2008. Exported proteins required for virulence and rigidity of Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes. Cell 134:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baruch DI, Gormely JA, Ma C, Howard RJ, Pasloske BL. 1996. Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 is a parasitized erythrocyte receptor for adherence to CD36, thrombospondin, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:3497–3502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marti M, Good RT, Rug M, Knuepfer E, Cowman AF. 2004. Targeting malaria virulence and remodeling proteins to the host erythrocyte. Science 306:1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1102452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiller NL, Bhattacharjee S, van Ooij C, Liolios K, Harrison T, Lopez-Estraño C, Haldar K. 2004. A host-targeting signal in virulence proteins reveals a secretome in malarial infection. Science 306:1934–1937. doi: 10.1126/science.1102737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Ooij C, Tamez P, Bhattacharjee S, Hiller NL, Harrison T, Liolios K, Kooij T, Ramesar J, Balu B, Adams J, Waters A, Janse CJ, Haldar K. 2008. The malaria secretome: from algorithms to essential function in blood stage infection. PLoS Pathog 4:e01538-16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sargeant TJ, Marti M, Caler E, Carlton JM, Simpson K, Speed TP, Cowman AF. 2006. Lineage-specific expansion of proteins exported to erythrocytes in malaria parasites. Genome Biol 7:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boddey JA, Carvalho TG, Hodder AN, Sargeant TJ, Sleebs BE, Marapana D, Lopaticki S, Nebl T, Cowman AF. 2013. Role of plasmepsin V in export of diverse protein families from the Plasmodium falciparum exportome. Traffic 14:532–550. doi: 10.1111/tra.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiber A, Kruse F, Pick C, Grüring C, Flemming S, Oberli A, Schoeler H, Retzlaff S, Mesén-Ramírez P, Hiss JA, Kadekoppala M, Hecht L, Holder AA, Gilberger TW, Spielmann T. 2013. Identification of new PNEPs indicates a substantial non-PEXEL exportome and underpins common features in Plasmodium falciparum protein export. PLoS Pathog 9:e01538-16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellsworth ML, Ellis CG, Goldman D, Stephenson AH, Dietrich HH, Sprague RS. 2009. Erythrocytes: oxygen sensors and modulators of vascular tone. Physiology (Bethesda) 24:107–116. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00038.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang H, McGiff JC, Fava C, Amen G, Nesta E, Zanconato G, Quilley J, Minuz P. 2013. Maternal and fetal epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in normotensive and preeclamptic pregnancies. Am J Hypertens 26:271–278. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hps011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang H, Quilley J, Reddy LM, Falck JR, Wong PY, McGiff JC. 2005. Red blood cells: reservoirs of cis- and trans-epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 75:65–78. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goulitquer S, Dréano Y, Berthou F, Corcos L, Lucas D. 2008. Determination of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in human red blood cells and plasma by GC/MS in the NICI mode. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 876:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang H, Anderson GD, McGiff JC. 2012. The red blood cell participates in regulation of the circulation by producing and releasing epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 98:91–93. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spector AA, Fang X, Snyder GD, Weintraub NL. 2004. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs): metabolism and biochemical function. Prog Lipid Res 43:55–90. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(03)00049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang H, Zhu AG, Mamczur M, Falck JR, Lerea KM, McGiff JC. 2007. Stimulation of rat erythrocyte P2X7 receptor induces the release of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Br J Pharmacol 151:1033–1040. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen BT, Gutterman DD, Hatoum OA. 2006. Emerging role of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in coronary vascular function. Eur J Clin Invest 36:293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Node K, Huo Y, Ruan X, Yang B, Spiecker M, Ley K, Zeldin DC, Liao JK. 1999. Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science 285:1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomson SJ, Askari A, Bishop-Bailey D. 2012. Anti-inflammatory effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Int J Vasc Med 2012:e01538-16. doi: 10.1155/2012/605101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng Y, Theken KN, Lee CR. 2010. Cytochrome P450 epoxygenases, soluble epoxide hydrolase, and the regulation of cardiovascular inflammation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chertow JH, Alkaitis MS, Nardone G, Ikeda AK, Cunnington AJ, Okebe J, Ebonyi AO, Njie M, Correa S, Jayasooriya S, Casals-Pascual C, Billker O, Conway DJ, Walther M, Ackerman H. 2015. Plasmodium infection is associated with impaired hepatic dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase activity and disruption of nitric oxide synthase inhibitor/substrate homeostasis. PLoS Pathog 11:e01538-16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenhut M. 2015. The evidence for a role of vasospasm in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Malar J 14:405. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0928-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carvalho LJ, Moreira ADS, Daniel-Ribeiro CT, Martins YC. 2014. Vascular dysfunction as a target for adjuvant therapy in cerebral malaria. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 109:577–588. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276140061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller LH, Ackerman HC, Su XZ, Wellems TE. 2013. Malaria biology and disease pathogenesis: insights for new treatments. Nat Med 19:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nm.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janka JJ, Koita OA, Traoré B, Traoré JM, Mzayek F, Sachdev V, Wang X, Sanogo K, Sangaré L, Mendelsohn L, Masur H, Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Krogstad DJ. 2010. Increased pulmonary pressures and myocardial wall stress in children with severe malaria. J Infect Dis 202:791–800. doi: 10.1086/655225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris TR, Hammock BD. 2013. Soluble epoxide hydrolase: gene structure, expression and deletion. Gene 526:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imig JD. 2016. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid on endothelial and vascular function. Adv Pharmacol 77:105–141. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, Gao X, Gingle A, Grant G, Harb OS, Heiges M, Innamorato F, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Kraemer E, Li W, Miller JA, Nayak V, Pennington C, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Ross C, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Treatman C, Wang H. 2009. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D539–D543. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. 2015. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pei X, Guo X, Coppel R, Bhattacharjee S, Haldar K, Gratzer W, Mohandas N, An X. 2007. The ring-infected erythrocyte surface antigen (RESA) of Plasmodium falciparum stabilizes spectrin tetramers and suppresses further invasion. Blood 110:1036–1042. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-076919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weng H, Guo X, Papoin J, Wang J, Coppel R, Mohandas N, An X. 2014. Interaction of Plasmodium falciparum knob-associated histidine-rich protein (KAHRP) with erythrocyte ankyrin R is required for its attachment to the erythrocyte membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta 1838:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh SS, Voigt S, Fisher D, Yi SJ, LeRoy PJ, Derick LH, Liu S, Chishti AH. 2000. Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 is anchored to the actin-spectrin junction and knob-associated histidine-rich protein in the erythrocyte skeleton. Mol Biochem Parasitol 108:237–247. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(00)00227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waller KL, Stubberfield LM, Dubljevic V, Nunomura W, An X, Mason AJ, Mohandas N, Cooke BM, Coppel RL. 2007. Interactions of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 3 with the red blood cell membrane skeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768:2145–2156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pei X, Guo X, Coppel R, Mohandas N, An X. 2007. Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 3 (PfEMP3) destabilizes erythrocyte membrane skeleton. J Biol Chem 282:26754–26758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pei X, An X, Guo X, Tarnawski M, Coppel R, Mohandas N. 2005. Structural and functional studies of interaction between Plasmodium falciparum knob-associated histidine-rich protein (KAHRP) and erythrocyte spectrin. J Biol Chem 280:31166–31171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Toole PJ, Morrison IE, Cherry RJ. 2000. Investigations of spectrin-lipid interactions using fluoresceinphosphatidylethanolamine as a membrane probe. Biochim Biophys Acta 1466:39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(00)00168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ipsaro JJ, Huang L, Mondragón A. 2009. Structures of the spectrin-ankyrin interaction binding domains. Blood 113:5385–5393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu CJ, Lemay A, Eshdat Y, Marchesi VT. 1979. Substructure of human erythrocyte spectrin. J Supramol Struct 10:227–239. doi: 10.1002/jss.400100212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klemba M, Beatty W, Gluzman I, Goldberg DE. 2004. Trafficking of plasmepsin II to the food vacuole of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Cell Biol 164:47–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb200307147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knuepfer E, Rug M, Cowman AF. 2005. Function of the plasmodium export element can be blocked by green fluorescent protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol 142:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grüring C, Heiber A, Kruse F, Flemming S, Franci G, Colombo SF, Fasana E, Schoeler H, Borgese N, Stunnenberg HG, Przyborski JM, Gilberger TW, Spielmann T. 2012. Uncovering common principles in protein export of malaria parasites. Cell Host Microbe 12:717–729. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Przyborski JM, Miller SK, Pfahler JM, Henrich PP, Rohrbach P, Crabb BS, Lanzer M. 2005. Trafficking of STEVOR to the Maurer’s clefts in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. EMBO J 24:2306–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Decker M, Adamska M, Cronin A, Di Giallonardo F, Burgener J, Marowsky A, Falck JR, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Gruzdev A, Zeldin DC, Arand M. 2012. EH3 (ABHD9): the first member of a new epoxide hydrolase family with high activity for fatty acid epoxides. J Lipid Res 53:2038–2045. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M024448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Loo B, Kingma J, Arand M, Wubbolts MG, Janssen DB. 2006. Diversity and biocatalytic potential of epoxide hydrolases identified by genome analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:2905–2917. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2905-2917.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arand M, Grant DF, Beetham JK, Friedberg T, Oesch F, Hammock BD. 1994. Sequence similarity of mammalian epoxide hydrolases to the bacterial haloalkane dehalogenase and other related proteins. Implication for the potential catalytic mechanism of enzymatic epoxide hydrolysis. FEBS Lett 338:251–256. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones PD, Wolf NM, Morisseau C, Whetstone P, Hock B, Hammock BD. 2005. Fluorescent substrates for soluble epoxide hydrolase and application to inhibition studies. Anal Biochem 343:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vignali M, Armour CD, Chen J, Morrison R, Castle JC, Biery MC, Bouzek H, Moon W, Babak T, Fried M, Raymond CK, Duffy PE. 2011. NSR-seq transcriptional profiling enables identification of a gene signature of Plasmodium falciparum parasites infecting children. J Clin Invest 121:1119–1129. doi: 10.1172/JCI43457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Khim N, Sreng S, Chim P, Kim S, Lim P, Mao S, Sopha C, Sam B, Anderson JM, Duong S, Chuor CM, Taylor WR, Suon S, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Fairhurst RM, Menard D. 2013. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: in-vitro and ex-vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis 13:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70252-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Witkowski B, Khim N, Chim P, Kim S, Ke S, Kloeung N, Chy S, Duong S, Leang R, Ringwald P, Dondorp AM, Tripura R, Benoit-Vical F, Berry A, Gorgette O, Ariey F, Barale JC, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Menard D. 2013. Reduced artemisinin susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum ring stages in western Cambodia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:914–923. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01868-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sridharan M, Bowles EA, Richards JP, Krantic M, Davis KL, Dietrich KA, Stephenson AH, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS. 2012. Prostacyclin receptor-mediated ATP release from erythrocytes requires the voltage-dependent anion channel. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302:H553–H559. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00998.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akkaya C, Shumilina E, Bobballa D, Brand VB, Mahmud H, Lang F, Huber SM. 2009. The Plasmodium falciparum-induced anion channel of human erythrocytes is an ATP-release pathway. Pflugers Arch 457:1035–1047. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bouyer G, Cueff A, Egée S, Kmiecik J, Maksimova Y, Glogowska E, Gallagher PG, Thomas SL. 2011. Erythrocyte peripheral type benzodiazepine receptor/voltage-dependent anion channels are upregulated by Plasmodium falciparum. Blood 118:2305–2312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramdani G, Langsley G. 2014. ATP, an extracellular signaling molecule in red blood cells: a messenger for malaria? Biol Med J 37:284–292. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.132910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Proellocks NI, Herrmann S, Buckingham DW, Hanssen E, Hodges EK, Elsworth B, Morahan BJ, Coppel RL, Cooke BM. 2014. A lysine-rich membrane-associated PHISTb protein involved in alteration of the cytoadhesive properties of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells. FASEB J 28:3103–3113. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-250399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oberli A, Slater LM, Cutts E, Brand F, Mundwiler-Pachlatko E, Rusch S, Masik MF, Erat MC, Beck HP, Vakonakis I. 2014. A Plasmodium falciparum PHIST protein binds the virulence factor PfEMP1 and comigrates to knobs on the host cell surface. FASEB J 28:4420–4433. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-256057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spycher C, Rug M, Klonis N, Ferguson DJ, Cowman AF, Beck HP, Tilley L. 2006. Genesis of and trafficking to the Maurer’s clefts of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Mol Cell Biol 26:4074–4085. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00095-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saridaki T, Fröhlich KS, Braun-Breton C, Lanzer M. 2009. Export of PfSBP1 to the Plasmodium falciparum Maurer’s clefts. Traffic 10:137–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biswal BK, Morisseau C, Garen G, Cherney MM, Garen C, Niu C, Hammock BD, James MN. 2008. The molecular structure of epoxide hydrolase B from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its complex with a urea-based inhibitor. J Mol Biol 381:897–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pelle KG, Oh K, Buchholz K, Narasimhan V, Joice R, Milner DA, Brancucci NM, Ma S, Voss TS, Ketman K, Seydel KB, Taylor TE, Barteneva NS, Huttenhower C, Marti M. 2015. Transcriptional profiling defines dynamics of parasite tissue sequestration during malaria infection. Genome Med 7:19. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu J, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. 2014. Expression and characterization of an epoxide hydrolase from Anopheles gambiae with high activity on epoxy fatty acids. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 54:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu J, Morisseau C, Yang J, Mamatha DM, Hammock BD. 2015. Epoxide hydrolase activities and epoxy fatty acids in the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 59:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu J, Morisseau C, Yang J, Lee KS, Kamita SG, Hammock BD. 2016. Ingestion of the epoxide hydrolase inhibitor AUDA modulates immune responses of the mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus during blood feeding. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 76:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nwokocha CR, Ajayi IO, Ebeigbe AB. 2011. Altered vascular reactivity induced by malaria parasites. West Indian Med J 60:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swiatecka-Urban A, Moreau-Marquis S, Maceachran DP, Connolly JP, Stanton CR, Su JR, Barnaby R, O’Toole GA, Stanton BA. 2006. Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits endocytic recycling of CFTR in polarized human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290:C862–C872. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00108.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.MacEachran DP, Ye S, Bomberger JM, Hogan DA, Swiatecka-Urban A, Stanton BA, O’Toole GA. 2007. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa secreted protein PA2934 decreases apical membrane expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Infect Immun 75:3902–3912. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00338-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bahl CD, Hvorecny KL, Bomberger JM, Stanton BA, Hammock BD, Morisseau C, Madden DR. 2015. Inhibiting an epoxide hydrolase virulence factor from Pseudomonas aeruginosa protects CFTR. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 54:9881–9885. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bomberger JM, Ye S, Maceachran DP, Koeppen K, Barnaby RL, O’Toole GA, Stanton BA. 2011. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxin that hijacks the host ubiquitin proteolytic system. PLoS Pathog 7:e01538-16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bahl CD, Morisseau C, Bomberger JM, Stanton BA, Hammock BD, O’Toole GA, Madden DR. 2010. Crystal structure of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator inhibitory factor Cif reveals novel active-site features of an epoxide hydrolase virulence factor. J Bacteriol 192:1785–1795. doi: 10.1128/JB.01348-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zou J, Hallberg BM, Bergfors T, Oesch F, Arand M, Mowbray SL, Jones TA. 2000. Structure of Aspergillus niger epoxide hydrolase at 1.8-A resolution: implications for the structure and function of the mammalian microsomal class of epoxide hydrolases. Structure 8:111–122. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jochens H, Stiba K, Savile C, Fujii R, Yu JG, Gerassenkov T, Kazlauskas RJ, Bornscheuer UT. 2009. Converting an esterase into an epoxide hydrolase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 48:3532–3535. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rauwerdink A, Kazlauskas RJ. 2015. How the same core catalytic machinery catalyzes 17 different reactions: the serine-histidine-aspartate catalytic triad of α/β-hydrolase fold enzymes. ACS Catal 5:6153–6176. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b01539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.da Silva FL, Dixon MW, Stack CM, Teuscher F, Taran E, Jones MK, Lovas E, Tilley L, Brown CL, Trenholme KR, Dalton JP, Gardiner DL, Skinner-Adams TS. 2016. A Plasmodium falciparum S33 proline aminopeptidase is associated with changes in erythrocyte deformability. Exp Parasitol 169:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mahon CS, O’Donoghue AJ, Goetz DH, Murray PG, Craik CS, Tuohy MG. 2009. Characterization of a multimeric, eukaryotic prolyl aminopeptidase: an inducible and highly specific intracellular peptidase from the non-pathogenic fungus Talaromyces emersonii. Microbiology 155:3673–3682. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.030940-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bolumar T, Sanz Y, Aristoy MC, Toldrá F. 2003. Purification and characterization of a prolyl aminopeptidase from Debaryomyces hansenii. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:227–232. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.227-232.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Page MJ, Di Cera E. 2008. Evolution of peptidase diversity. J Biol Chem 283:30010–30014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804650200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reynolds SL, Fischer K. 2015. Pseudoproteases: mechanisms and function. Biochem J 468:17–24. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rawlings ND, Morton FR. 2008. The MEROPS batch BLAST: a tool to detect peptidases and their non-peptidase homologues in a genome. Biochimie 90:243–259. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marchot P, Chatonnet A. 2012. Enzymatic activity and protein interactions in alpha/beta hydrolase fold proteins: moonlighting versus promiscuity. Protein Pept Lett 19:132–143. doi: 10.2174/092986612799080284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bellien J, Joannides R. 2013. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid pathway in human health and diseases. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 61:188–196. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318273b007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Waltenberger B, Garscha U, Temml V, Liers J, Werz O, Schuster D, Stuppner H. 2016. Discovery of potent soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) inhibitors by pharmacophore-based virtual screening. J Chem Inf Model 56:747–762. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. 1979. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J Parasitol 65:418–420. doi: 10.2307/3280287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beck JR, Muralidharan V, Oksman A, Goldberg DE. 2014. PTEX component HSP101 mediates export of diverse malaria effectors into host erythrocytes. Nature 511:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature13574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tonkin CJ, van Dooren GG, Spurck TP, Struck NS, Good RT, Handman E, Cowman AF, McFadden GI. 2004. Localization of organellar proteins in Plasmodium falciparum using a novel set of transfection vectors and a new immunofluorescence fixation method. Mol Biochem Parasitol 137:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sigala PA, Crowley JR, Hsieh S, Henderson JP, Goldberg DE. 2012. Direct tests of enzymatic heme degradation by the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem 287:37793–37807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.414078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bopp SE, Manary MJ, Bright AT, Johnston GL, Dharia NV, Luna FL, McCormack S, Plouffe D, McNamara CW, Walker JR, Fidock DA, Denchi EL, Winzeler EA. 2013. Mitotic evolution of Plasmodium falciparum shows a stable core genome but recombination in antigen families. PLoS Genet 9:e01538-16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim DE, Chivian D, Baker D. 2004. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res 32:W526–W531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]