Abstract

All cases of multiple myeloma (MM) are preceded by precursor states termed monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) or smoldering myeloma (SMM). Genetic analyses of MGUS cells have provided evidence that it is a genetically advanced lesion, wherein tumor cells carry many of the genetic changes found in MM cells. Intraclonal heterogeneity is also established early during the MGUS phase. Although the genetic features of MGUS or SMM cells at baseline may predict disease risk, transition to MM involves altered growth of preexisting clones. Recent advances in mouse modeling of MGUS suggest that the clinical dormancy of the clone may be regulated in part by growth controls extrinsic to the tumor cells. Interactions of MGUS cells with immune cells, bone cells, and others in the bone marrow niche may be key regulators of malignant transformation. These interactions involve a bidirectional crosstalk leading to both growth-supporting and inhibitory signals. Because MGUS is already a genetically complex lesion, application of new tools for earlier detection should allow delineation of earlier stages, which we term as pre-MGUS. Analyses of populations at increased risk of MGUS also suggest the possible existence of a polyclonal phase preceding the development of MGUS. Monoclonal gammopathy in several patients may have potential clinical significance in spite of low risk of malignancy. Understanding the entire spectrum of these disorders may have broader implications beyond prevention of clinical malignancy.

It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma; but perhaps there is the key.

Winston Churchill, 1939

Historical context and definitions

The quote above from Winston Churchill’s famous radio broadcast was meant to discuss his inability to precisely predict Russia’s actions during World War II, but may as well apply to monoclonal gammopathies. Monoclonal gammopathies were first described as a clinical entity termed essential hypergammaglobulinemia by the late Jan Gosta Waldenström in 1960.1 In 1978, seminal studies by Kyle and colleagues introduced the term monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) to illustrate the potential of some of these lesions to progress to clinical malignancy such as multiple myeloma or related disorders.2 The term smoldering myeloma (SMM) was then coined in 1980 to describe patients with continued clinical stability in the face of bone marrow plasmacytosis, similar to myeloma requiring therapy.3 With the introduction of the serum-free light-chain assay, light-chain gammopathy was described as a precursor to light-chain myeloma.4 Although the diagnostic criteria (in terms of cutoffs) for SMM differed in early reports, and many patients with MGUS in the initial studies did not undergo diagnostic bone marrow biopsies, the current definition of these disorders is well validated and based on the presence of a clonal plasma cell disorder in the absence of myeloma-related organ dysfunction or amyloidosis, and a cutoff of serum M spike ≥3 g/dL or bone marrow plasmacytosis of ≥10% for distinguishing asymptomatic multiple myeloma (AMM) vs MGUS.5 It is notable that in models evaluating disease risks, these cutoffs do not represent discrete risk inflection points,6 and quantifying percent marrow plasmacytosis can be challenging because of multifocal involvement. Nonetheless, these criteria have served the field well to harmonize clinical research, and they identify cohorts with distinct risks of progression to myeloma requiring therapy (1% per year for MGUS and 10% per year for AMM).7,8 Measures of tumor bulk (level of M spike, free light chains), nature of IgH type (IgG vs IgA), proportion of clonal plasma cells, and immune paresis have been used to create risk models.9,10 These models are again useful to guide clinical research, in spite of suboptimal concordance between them.11 Prospective and mature data sets with uniformly staged patients at baseline (such as the recently reported SWOG trial)6 are currently limited. More recently, marked elevation of serum-free light-chain ratio >100, presence of ≥2 focal lesions on magnetic resonance imaging, and extreme bone marrow plasmacytosis (>60%) were proposed as criteria for initiation of therapy.5 Long-term impact of early therapy of these lesions remains to be determined. In spite of major advances, our understanding of the pathogenesis of MGUS and MM remains incomplete. Several aspects of clinical diagnosis and management of these precursor lesions have been a subject of excellent reviews and updated guidelines.12,13 In this perspective, I will emphasize the emerging insights in the biology of these preneoplastic lesions and their transition to clinical malignancy.

All myeloma clones are preceded by corresponding precursor states but do they all take the same road?

Most human cancers are preceded by a precursor state that is more common than the cancer itself, and myeloma is no exception. It is now well appreciated that nearly all cases of MM are preceded by an asymptomatic precursor state such as MGUS or SMM. Landgren et al analyzed subjects from a large screening trial to demonstrate that MGUS could be consistently documented in the samples collected before the diagnosis of myeloma.14 Another study by Weiss et al documented the presence of preceding monoclonal gammopathy in 27 of 30 myeloma patients, using sera collected ≥2 years before the diagnosis of clinical MM.15 The concept of MGUS as a precursor state bears a striking resemblance to precursors for other hematologic malignancies characterized in recent years.16,17 MGUS/MM is an important model to study basic aspects of early human carcinogenesis, because the precursor state is not resectable and can be sampled repeatedly; both tumor cells and nonmalignant cells from the bone marrow can be readily isolated; tumor cells secrete a highly tumor-specific biomarker in the form of clonal immunoglobulin; patients with preneoplasia lack cytopenia requiring transfusions or other therapeutic interventions. Myeloma is not a single disease and can be classified into several broad genetic subtypes.18,19 Tumor in each individual patient has a unique profile of genetic and epigenetic changes and clonal architecture.18,20-22 How and whether the individual subclones compete or cooperate with each other are areas of active investigation in diverse cancers. In hematologic malignancies such as MM, tumor cells are “disseminated” even at earlier stages. At a simplistic level, the process of malignant transformation in MM could be viewed as a change in the net clonal mass, which in turn depends on the balance of birth and death rates of individual subclones, affected by the crosstalk with host factors.22-24 It will be important to test whether the mechanisms underlying malignant transformation differ between individual subtypes or even individual patients. Factors regulating tumor progression could be classified as tumor cell autonomous (or intrinsic) or microenvironment-dependent/extrinsic factors, and as we discuss later, may well differ between individual subclones. Importantly, these interactions between evolution of tumor subclones and host response are likely to be bidirectional and depend on each other.

MGUS as a genetically advanced lesion

Introduction of cytogenetics and gene-expression profiling has led to the surprising finding that the majority of cytogenetic changes detected in MM cells can also be detected in MGUS cells.18,25-30 Gene-expression profiling of purified MGUS cells revealed that purified plasma cells from MGUS are much closer to MM cells than normal plasma cells.31 Cytogenetically, the presence of specific chromosome abnormalities such as del(17p), t(4:14), 1q gains, and hyperdiploidy seem to correlate with increased risk of disease progression in SMM.32-34 All of the GEP-based subsets of MM can also be identified in the precursor cohorts, although none of these GEP-based subsets (which do correlate with some of the cytogenetic subsets) have a dramatically altered risk of progression.6 Notably, the musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma subset, which typically associates with high-risk MM, does not portend similar high risk when identified in the MGUS/AMM setting.6 Interestingly, the presence of a 70-gene gene-expression profiling signature6 (which correlates in part with chromosome 1 abnormalities and identifies high-risk MM) as well as a 4-gene signature,35 were found to be strong predictors of risk of progression to clinical MM requiring therapy. Progression to clinical MM has also been linked to the activation of c-myc21,36,37 and other signaling pathways,38 and reduced capacity for Ig secretion.39 Other important tumor-cell intrinsic regulators of malignant transformation could be changes in noncoding RNAs40 or epigenetic changes41 in tumor cells. Together these data suggest that genetic and genomic properties of MGUS cells could be strong predictors of eventual risk of malignant transformation.

Comparison of plasma cells from MGUS vs MM cohorts revealed increasing proportion of clonal plasma cells with genetic abnormalities, overall consistent with the expansion of preexisting clones at the transition of MGUS to MM.28 Genome sequencing studies have mostly focused on MM and revealed complex patterns of clonal evolution with about 4 to 5 major subclones within MM genomes.22,42 These studies are also consistent with patterns of divergent evolution possibly involving a less differentiated clonal progenitor in some cases.43 To date, only 2 small studies have described genome sequencing in paired, prospectively collected samples of precursor states compared with progression to clinical MM in the same patient.44,45 Both of these studies have shown that genomic complexity and intraclonal heterogeneity of tumor cells is established early in evolution of tumors. In these studies, progression to clinical MM in most patients did not involve new/recurrent somatic mutations, although there was some subclonal selection with progression. Besides small sample size, the studies are also limited by short time to progression in the patients studied. Interestingly, the baseline mutational spectrum in progressive lesions demonstrated greater overlap with known changes in the genomes of clinical MM than in nonprogressor lesions.45 These data (albeit preliminary particularly because of the small sample sizes) again suggest that the many of the genetic changes observed in MM are already present before clinical malignancy, and that the baseline pattern of genetic changes may correlate with the ultimate risk of malignant transformation. Larger studies to prospectively evaluate evolution of precursor states, and including modern single-cell technologies, should shed further light on this issue. Genomic analysis of MGUS in particular needs to account for the contamination of normal plasma cells in CD138-selected cells. Analysis of genomic diversity, however, needs functional validation of growth potential of the subclones, and one of the challenges in the field has been the inability to reliably grow human preneoplastic gammopathies in vivo. Recent development of humanized mouse models is permitting successful growth of MGUS lesions or their subclones in vivo in preliminary studies and may provide novel insights into the biology of these lesions.46 Initial studies from these models also illustrate the genomic complexity in MGUS, as well as the presence of minor subclones that may carry lesions (such as chromosome 1 changes) typically associated with high-risk disease.46 The realization that MGUS is a genomically complex lesion carrying many of the driver mutations seen in MM without clear evidence for recurrent new lesions at transition to MM raises several questions: What keeps MGUS lesions/subclones stable? Why do minor subclones with potentially higher-risk lesions not become dominant already at the MGUS stage? How is this complexity generated?

Is it all about the soil? The role of tumor microenvironment

The concept that most MGUS lesions exhibit clinical stability in spite of advanced genomic complexity and intraclonal evolution of the tumor clone suggests the possibility that changes in growth rate and therefore malignant transformation may depend in part on interactions of tumor cells with the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Figure 1). Recent studies have shown that MGUS cells mediate progressive growth upon xenotransplantation in humanized mice.46 In this model, genetic humanization of mice is achieved by the expression of several human genes in mice that are essential for the growth of human cells and mediate species-specific effects.46,47 This observation provides direct support to the concept that the observed clinical stability of MGUS lesions may indeed depend predominantly on tumor-extrinsic growth controls. In other words, the process of “malignant transformation” may depend more on how the tumor cells modify the host-mediated growth control. MGUS or MM cells grow primarily in the bone marrow and interact with several cells in this complex microenvironment, including immune cells, bone cells, endothelial cells, stromal cells, and non-cellular matrix.48 Because MGUS is a disorder of an immune cell infiltrating the bone marrow, I will particularly focus on the immune and bone component of the TME. Simplistically, tumor-TME interactions can be classified as those permissive or antagonistic to tumor growth. In many instances, it is the loss of normal microenvironment that creates conditions permissive for tumor growth.

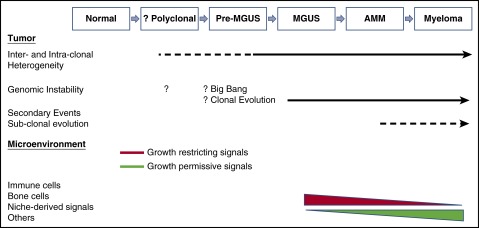

Figure 1.

Tumor and microenvironment in natural history of gammopathies. Emerging data suggest that much of the genomic complexity and intraclonal heterogeneity is already well established by MGUS stage. The mechanism underlying the origins of this instability is not clear but may involve a big bang followed by clonal evolution. Clinical dormancy of MGUS or AMM lesions depends in part on interactions with the tumor microenvironment, and alteration of these signals can promote changes in growth kinetics at the population level, manifested as malignant transformation. Genetic complexity of MGUS also points to the presence of proximate, potentially less complex lesions termed pre-MGUS. We hypothesize that these lesions emerge from an initial polyclonal response to endogenous or exogenous antigens. Tumor evolution is driven by both tumor-intrinsic and tumor-extrinsic events that may be interdependent.

Immune cells

Interaction of tumor with immune cells can mediate both pro- and antitumor effects. Several studies have shown that MM tumors are infiltrated with dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages.48 Interactions of MM cells with both myeloid or plasmacytoid DCs can promote tumor growth.49-52 Tumor-DC interactions may also promote cell fusion and formation of osteoclasts,53,54 as well as genetic instability by inducing the expression of cytidine deaminases.55 The importance of T-follicular helper (TFH) cells in the generation of long-lived plasma cells is well established.56 Although less studied directly in the context of MM, interactions with TFH cells may also promote malignant B-cell differentiation.57 Several studies have demonstrated the capacity of innate and adaptive immune cells to recognize MM/MGUS cells and potentially mediate growth control.58 Tumor-specific CD4 and CD8+ T cells can be identified in the bone marrow of MGUS patients.59 Much of this response is specific to individual tumors.59 However, search for shared antigens has identified distinct targets of immunity in MGUS, such as SOX2 embryonal stem cell antigen.60 In a recent prospective study, the presence of SOX2-specific T cells and the expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells and T cells at baseline correlated with risk of progression to clinical MM requiring therapy.61 Progression to clinical MM is associated with a loss of effector function in several immune effectors including T, natural killer (NK), and NKT cells.62,63 However even in the setting of clinical MM, the bone marrow contains antimyeloma T cells that may be harnessed for immune therapy.63,64 Several mechanisms have been proposed to help explain the loss of tumor immunity with malignant progression. These include shedding of suppressive factors such as NKG2D ligands,65 immune suppressive cytokines, as well as suppression mediated by regulatory T cells66,67 or myeloid-derived suppressor cells.68-70 It is notable that clinical MM is associated with a switch to IL17-producing Th17 cells, which correlate with MM bone disease.71-73 Several recent studies have demonstrated the expression of inhibitory immune checkpoints such as PD-L1 on tumor cells,61,74 although a role for other checkpoints such as CD22675 and induction of T-cell senescence76 has also been implicated. In addition to conventional T cells, other subsets of innate immune cells may also play a role in immune surveillance. In particular, importance of NK cells in MM control has been demonstrated in mouse models,75,77 and human NK cells can kill MM targets.78-81 Mechanisms underlying altered immune surveillance by NK and other innate immune cells may therefore also regulate myelomagenesis. Another common feature of evolution to MM appears to be an increase in biochemical features of chronic inflammation including bioactive lipids.82 Recent studies have identified subsets of human CD1d-restricted type II NKT cells against these lipids that are enriched in human MM and promote plasma cell differentiation.83,84 Altered balance of type I vs type II NKT cells may therefore also be an important immune-regulatory axis in evolution of MM82,85 and is further supported by loss of CD1d expression with disease progression of MM.86 Together these studies paint a complex picture, with a potential role for several immune cells and likely create redundancy that may affect immune-mediated growth control.87,88 They also suggest that combination approaches may be desirable for immune-based prevention or therapy of MM.

Role of bone marrow niche

An important aspect of both MGUS and MM is that the growth of tumor cells is largely restricted to the bone marrow. The tumor cells may therefore share niche with hematopoietic stem cells and/or normal long-lived plasma cells also thought to reside in the bone marrow.89 The nature and availability of the niche, the nature of niche-derived signals, and the competition or cooperation between subclones of tumor cells and their normal counterparts may all play a role in regulating the behavior of tumor cells in vivo.90,91

Bone cells

Development of lytic bone disease is a characteristic feature of MM. However alteration in bone homeostasis occurs early, and patients with MGUS can have alterations in skeletal architecture with an increased risk of fractures.92,93 Increased bone turnover is an early feature of gammopathy, and progression to clinical MM has been associated with an uncoupling of bone turnover with a decline in osteoblast function.94,95 Increased osteoclastogenesis in MM is thought to be the result of several factors including altered ratio of RANKL and OPG, as well as expression of chemokines such as macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)1α/β, IL6, and metalloproteinases.96-98 Osteoclasts and MM cells are involved in a positive feedback loop, wherein MM cells promote osteoclast differentiation/activity, and osteoclasts in turn support MM cell growth and survival.96,99 The mechanisms underlying loss of osteoblast differentiation/function in MM is an area of active investigation, but a role for IL3, wnt inhibitor Dickkopf1, and altered Notch signaling has been implicated.100-103 In a recent study, interaction with osteoblasts was implicated in inducing a dormancy signature, which was reversed by osteoclasts in a murine MM model.104 Therefore the balance of osteoclast/osteoblast interactions with tumor cells could play a direct role in regulating growth kinetics or tumor cells and thus malignant transformation. Accordingly, careful analyses of mediators or regulators of bone turnover or MM bone disease may provide important biomarkers of risk of malignancy in MGUS.96,100,105-108

Other stromal elements

Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) from MM patients promote tumor growth both in a cell-contact mediated fashion, as well as via the secretion of soluble factors.91 Secretion of growth differentiation factor 15 by BMSCs enhanced self-renewal of MM cells.109 BMSC-derived exosomes have been implicated in regulating MM cell growth through transfer of miRNAs.110 Another feature of MM marrow is increased angiogenesis, which has been postulated because of loss of an angiogenesis inhibitor.111 Recruitment of endothelial progenitors to the bone marrow niche was shown to regulate the growth of murine MM112 and may also play a similar role in human disease.

Taken together, it appears that there are several candidate players both in terms of growth-permissive and restrictive signals from the tumor microenvironment. It is likely that these signals co-evolve with the tumor. The balance of these factors is likely a key determinant of growth control of early tumors and malignant transformation.

How did we get here? The case for pre-MGUS and polyclonal phase: new insights from high-risk populations

The finding that MGUS lesions carry most of the genomic complexity found in MM suggests the need to explore the mechanisms underlying these genetic changes. Much of the genomic instability in MGUS is thought to originate in the germinal center.113 At least some of the genetic changes such as IgH translocations involve cytidine deaminases such as activation-induced cytidine deaminase, which can be induced by crosstalk between tumor cells and DCs.55,114 Analysis of mutational signatures also suggest the involvement of APOBECs in some MM lesions.115,116 Some of the genetic changes such as IgH translocations appear to be early events in myelomagenesis.18 However, the mechanisms that regulate the evolution of these early preclinical lesions are not known. Recent studies with deep sequencing of the Ig locus suggest ongoing somatic hypermutation in tumors from at least a subset of patients, which is also consistent with germinal center origin of the clone and is an area of active investigation.117 The absence of major genetic sweeps in most cases is also consistent with a “big bang” model for early origins,118 with clonal evolution subsequently shaping the overall architecture.119 As we diagnose these early lesions, it will be equally important to ascertain whether the mechanisms driving genomic instability are still active and how they could be arrested.

Current diagnosis of MGUS is based largely on the detection of clonal immunoglobulin by relatively insensitive assays such as serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation. However, the introduction of new mass spectrometry–based and other techniques may permit the detection of clonal immunoglobulin at earlier stages.120 We refer to these earlier plasma cell clones (ie, clonal plasma cells or Igs that do not meet the current criteria for MGUS) as pre-MGUS, and suggest that understanding the biology of these lesions will be important to understand the earliest events in the evolution of these tumors. As discussed earlier, recent availability of new mouse models that allow growth of precursor states will greatly facilitate these insights.121

Analysis of populations at higher risk for developing MM provides another important opportunity to gain insights into the early events in myelomagenesis, which in turn could translate into effective prevention. Gaucher disease (GD) is an inherited metabolic disorder characterized by marked accumulation of glucosphingolipids, particularly lyso-glucosylceramide (Lyso-GL1).122 GD cohorts exhibit >30-fold risk of developing MM compared with age-matched controls. Lyso-GL1 is recognized by a distinct set of type II NKT cells that provide help to B cells and promote plasma cell differentiation.84 Lipid-mediated immune activation may therefore promote the development of gammopathy in GD mice and patients.123 Consistent with this hypothesis, reduction of antigenic substrates leads to reduction in gammopathy in GD mouse models.123,124 Risk reduction was most impressive when the reduction of antigenic substrates was initiated earlier in the course of the gammopathy.124 Race is an important risk factor for the development of gammopathies, which then translates to higher risk of MM in blacks.125 Notably, both GD and African cohorts (in Ghana) also have an increased incidence of polyclonal gammopathies, suggesting that polyclonal B-cell activation may set the stage for the development of monoclonal gammopathies.122,126 This biology bears resemblance to B-cell tumors such as Epstein-Barr virus–driven lymphoproliferative disorders. In the setting of GD, both the polyclonal as well as monoclonal phases may be lipid-driven.123 However, the presence of polyclonal plasma cells or Igs of the same antigenic specificity as the clonal PCs/immunoglobulins found in MGUS remains to be shown. Two other cohorts carry an increased risk of gammopathy/MM and could also be very instructive in exploring novel approaches to prevention. Risk of gammopathy is increased in obesity127 and in cohorts of patients with a history of exposure to certain toxins such as Agent Orange.128 Obesity also creates a permissive environment for the growth of tumor cells in mice.129 These considerations implore the need to directly test whether lifestyle modifications targeting obesity will alter the natural history of gammopathy in these cohorts.

Are we underexploring the significance of MGUS?

To date, nearly all of the attention in terms of clinical care of patients with MGUS relates to the risk of development of MM. MGUS cohorts have a lower life expectancy compared with age- and sex-matched population controls, which is not entirely explained by the risk of malignant transformation.130-132 MGUS patients are also at an increased risk of morbidity related to several conditions such as skeletal morbidity, infections, other malignancies, neuropathies, thrombosis, and renal disease.12 If we were to apply emerging technologies to diagnose gammopathies earlier, we are likely to further increase the estimated prevalence of these disorders. The great majority of these early lesions would likely have low malignant potential but could still carry important clinical implications in terms of a defined morbidity. One example of such a concept is the recent appreciation of monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance.133 Further studies are therefore needed to understand the potential implication of the diagnosis of an expanded plasma cell clone in selected clinical settings wherein they might similarly affect pathogenesis and, ultimately, management. Some examples of such states may include acute osteoporosis, clinical suspicion of amyloid syndromes, neuropathies, and refractory autoimmunity (Table 1). Studying the biology of the clonal plasma cells and properties of immunoglobulins in these settings may allow us to develop simple approaches to diagnose and intervene early and eventually modify the risk of these morbidities. Early diagnosis in appropriate clinical settings may also help us identify clones that are genetically less advanced than those currently diagnosed as MGUS, and perhaps more amenable to eradiation. Although we have made great strides in the management of MM in the last decade, our best bet to eradicate this malignancy may lie in preventing it in the first place. Fully exploring the biology of MGUS may have broader implications for human health beyond MM.

Table 1.

Some examples of monoclonal gammopathies of (possible) clinical significance but low malignant potential

| Term | Organ | Clinical settings, comment |

|---|---|---|

| MGRS | Renal | Renal lesions currently incorporated under monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance, including proliferative glomerulonephritis133 |

| MGBS | Bone | Acute osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures |

| MGDS | Skin | Cryoglobulin vasculitis, Schnitzler syndrome, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, scleromyxedema, POEMS, pyoderma gangrenosum |

| MGNS | Neuropathies | Spectrum of neuropathies with MGUS |

MGBS, monoclonal gammopathy of bone significance; MGDS, monoclonal gammopathy of dermal significance; MGNS, monoclonal gammopathy of neuropathic significance; MGRS, monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance; POEMS, polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M spike, and Skin changes syndrome.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by funds from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (grants CA106802 and CA197603), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the International Waldenström Macroglobulinemia Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: M.V.D. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Madhav V. Dhodapkar, 333 Cedar St, Box 208021, New Haven, CT 06510; e-mail: madhav.dhodapkar@yale.edu.

References

- 1.Waldenstrom J. Studies on conditions associated with disturbed gamma globulin formation (gammopathies). Harvey Lect. 1960-1961;56:211-231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyle RA. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Natural history in 241 cases. Am J Med. 1978;64(5):814-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyle RA, Greipp PR. Smoldering multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1980;302(24):1347-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dispenzieri A, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, et al. . Prevalence and risk of progression of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375(9727):1721-1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. . International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538-e548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhodapkar MV, Sexton R, Waheed S, et al. . Clinical, genomic, and imaging predictors of myeloma progression from asymptomatic monoclonal gammopathies (SWOG S0120). Blood. 2014;123(1):78-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. . A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):564-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, et al. . Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(25):2582-2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Katzmann JA, et al. . Immunoglobulin free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(2):785-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pérez-Persona E, Vidriales MB, Mateo G, et al. . New criteria to identify risk of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and smoldering multiple myeloma based on multiparameter flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow plasma cells. Blood. 2007;110(7):2586-2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherry BM, Korde N, Kwok M, et al. . Modeling progression risk for smoldering multiple myeloma: results from a prospective clinical study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(10):2215-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landgren O, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. From myeloma precursor disease to multiple myeloma: new diagnostic concepts and opportunities for early intervention. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(6):1243-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Donk NW, Palumbo A, Johnsen HE, et al. ; European Myeloma Network. The clinical relevance and management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and related disorders: recommendations from the European Myeloma Network. Haematologica. 2014;99(6):984-996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. . Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood. 2009;113(22):5412-5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss BM, Abadie J, Verma P, Howard RS, Kuehl WM. A monoclonal gammopathy precedes multiple myeloma in most patients. Blood. 2009;113(22):5418-5422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganapathi KA, Pittaluga S, Odejide OO, Freedman AS, Jaffe ES. Early lymphoid lesions: conceptual, diagnostic and clinical challenges. Haematologica. 2014;99(9):1421-1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, et al. . Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2015;126(1):9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan GJ, Walker BA, Davies FE. The genetic architecture of multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(5):335-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhan F, Huang Y, Colla S, et al. . The molecular classification of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108(6):2020-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lohr JG, Stojanov P, Carter SL, et al. ; Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium. Widespread genetic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(1):91-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, et al. . Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471(7339):467-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolli N, Avet-Loiseau H, Wedge DC, et al. . Heterogeneity of genomic evolution and mutational profiles in multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. 2014;5:2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paíno T, Paiva B, Sayagués JM, et al. . Phenotypic identification of subclones in multiple myeloma with different chemoresistant, cytogenetic and clonogenic potential. Leukemia. 2015;29(5):1186-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casey SC, Tong L, Li Y, et al. . MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science. 2016;352(6282):227-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonseca R, Barlogie B, Bataille R, et al. . Genetics and cytogenetics of multiple myeloma: a workshop report. Cancer Res. 2004;64(4):1546-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fonseca R, Bailey RJ, Ahmann GJ, et al. . Genomic abnormalities in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2002;100(4):1417-1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufmann H, Ackermann J, Baldia C, et al. . Both IGH translocations and chromosome 13q deletions are early events in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and do not evolve during transition to multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2004;18(11):1879-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Corral L, Gutiérrez NC, Vidriales MB, et al. . The progression from MGUS to smoldering myeloma and eventually to multiple myeloma involves a clonal expansion of genetically abnormal plasma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(7):1692-1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Corral L, Sarasquete ME, Bea S, et al. . SNP-based mapping arrays reveal high genomic complexity in monoclonal gammopathies, from MGUS to myeloma status. Leukemia. 2012;26(12):2521-2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mikulasova A, Smetana J, Wayhelova M, et al. . Genome-wide profiling of copy-number alteration in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Eur J Haematol. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhan F, Hardin J, Kordsmeier B, et al. . Global gene expression profiling of multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, and normal bone marrow plasma cells. Blood. 2002;99(5):1745-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajkumar SV, Gupta V, Fonseca R, et al. . Impact of primary molecular cytogenetic abnormalities and risk of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2013;27(8):1738-1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanamura I, Stewart JP, Huang Y, et al. . Frequent gain of chromosome band 1q21 in plasma-cell dyscrasias detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization: incidence increases from MGUS to relapsed myeloma and is related to prognosis and disease progression following tandem stem-cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;108(5):1724-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neben K, Jauch A, Hielscher T, et al. . Progression in smoldering myeloma is independently determined by the chromosomal abnormalities del(17p), t(4;14), gain 1q, hyperdiploidy, and tumor load. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(34):4325-4332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan R, Dhodapkar M, Rosenthal A, et al. . Four genes predict high risk of progression from smoldering to symptomatic multiple myeloma (SWOG S0120). Haematologica. 2015;100(9):1214-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shou Y, Martelli ML, Gabrea A, et al. . Diverse karyotypic abnormalities of the c-myc locus associated with c-myc dysregulation and tumor progression in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(1):228-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chng WJ, Huang GF, Chung TH, et al. . Clinical and biological implications of MYC activation: a common difference between MGUS and newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2011;25(6):1026-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.López-Corral L, Corchete LA, Sarasquete ME, et al. . Transcriptome analysis reveals molecular profiles associated with evolving steps of monoclonal gammopathies. Haematologica. 2014;99(8):1365-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papanikolaou X, Rosenthal A, Dhodapkar M, et al. . Flow cytometry defined cytoplasmic immunoglobulin index is a major prognostic factor for progression of asymptomatic monoclonal gammopathies to multiple myeloma (subset analysis of SWOG S0120). Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pichiorri F, Suh SS, Rocci A, et al. . Downregulation of p53-inducible microRNAs 192, 194, and 215 impairs the p53/MDM2 autoregulatory loop in multiple myeloma development. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(4):367-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Agirre X, Castellano G, Pascual M, et al. . Whole-epigenome analysis in multiple myeloma reveals DNA hypermethylation of B cell-specific enhancers. Genome Res. 2015;25(4):478-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melchor L, Brioli A, Wardell CP, et al. . Single-cell genetic analysis reveals the composition of initiating clones and phylogenetic patterns of branching and parallel evolution in myeloma. Leukemia. 2014;28(8):1705-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green MR, Alizadeh AA. Common progenitor cells in mature B-cell malignancies: implications for therapy. Curr Opin Hematol. 2014;21(4):333-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker BA, Wardell CP, Melchor L, et al. . Intraclonal heterogeneity is a critical early event in the development of myeloma and precedes the development of clinical symptoms. Leukemia. 2014;28(2):384-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao S, Choi M, Heuck C, et al. . Serial exome analysis of disease progression in premalignant gammopathies. Leukemia. 2014;28(7):1548-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Das R, Strowig T, Verma R, et al. . Microenvironment-dependent growth of preneoplastic and malignant plasma cells in humanized mice. Nat Med. 2016;ePub Oct 10, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Rongvaux A, Takizawa H, Strowig T, et al. . Human hemato-lymphoid system mice: current use and future potential for medicine. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:635-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawano Y, Moschetta M, Manier S, et al. . Targeting the bone marrow microenvironment in multiple myeloma. Immunol Rev. 2015;263(1):160-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kukreja A, Hutchinson A, Dhodapkar K, et al. . Enhancement of clonogenicity of human multiple myeloma by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203(8):1859-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kukreja A, Hutchinson A, Mazumder A, et al. . Bortezomib disrupts tumour-dendritic cell interactions in myeloma and lymphoma: therapeutic implications. Br J Haematol. 2007;136(1):106-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chauhan D, Singh AV, Brahmandam M, et al. . Functional interaction of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with multiple myeloma cells: a therapeutic target. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(4):309-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bahlis NJ, King AM, Kolonias D, et al. . CD28-mediated regulation of multiple myeloma cell proliferation and survival. Blood. 2007;109(11):5002-5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kukreja A, Radfar S, Sun BH, Insogna K, Dhodapkar MV. Dominant role of CD47-thrombospondin-1 interactions in myeloma-induced fusion of human dendritic cells: implications for bone disease. Blood. 2009;114(16):3413-3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tucci M, Ciavarella S, Strippoli S, Brunetti O, Dammacco F, Silvestris F. Immature dendritic cells from patients with multiple myeloma are prone to osteoclast differentiation in vitro. Exp Hematol. 2011;39(7):773-783, e771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koduru S, Wong E, Strowig T, et al. . Dendritic cell-mediated activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)-dependent induction of genomic instability in human myeloma. Blood. 2012;119(10):2302-2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tangye SG, Ma CS, Brink R, Deenick EK. The good, the bad and the ugly - TFH cells in human health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):412-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rawal S, Chu F, Zhang M, et al. . Cross talk between follicular Th cells and tumor cells in human follicular lymphoma promotes immune evasion in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol. 2013;190(12):6681-6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhodapkar MV. Harnessing host immune responses to preneoplasia: promise and challenges. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54(5):409-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dhodapkar MV, Krasovsky J, Osman K, Geller MD. Vigorous premalignancy-specific effector T cell response in the bone marrow of patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2003;198(11):1753-1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spisek R, Kukreja A, Chen LC, et al. . Frequent and specific immunity to the embryonal stem cell-associated antigen SOX2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2007;204(4):831-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dhodapkar MV, Sexton R, Das R, et al. . Prospective analysis of antigen-specific immunity, stem-cell antigens, and immune checkpoints in monoclonal gammopathy. Blood. 2015;126(22):2475-2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, et al. . A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. J Exp Med. 2003;197(12):1667-1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dhodapkar MV, Krasovsky J, Olson K. T cells from the tumor microenvironment of patients with progressive myeloma can generate strong, tumor-specific cytolytic responses to autologous, tumor-loaded dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(20):13009-13013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Noonan K, Matsui W, Serafini P, et al. . Activated marrow-infiltrating lymphocytes effectively target plasma cells and their clonogenic precursors. Cancer Res. 2005;65(5):2026-2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jinushi M, Vanneman M, Munshi NC, et al. . MHC class I chain-related protein A antibodies and shedding are associated with the progression of multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(4):1285-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beyer M, Kochanek M, Giese T, et al. . In vivo peripheral expansion of naive CD4+CD25high FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107(10):3940-3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prabhala RH, Neri P, Bae JE, et al. . Dysfunctional T regulatory cells in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107(1):301-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Görgün GT, Whitehill G, Anderson JL, et al. . Tumor-promoting immune-suppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the multiple myeloma microenvironment in humans. Blood. 2013;121(15):2975-2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Serafini P, Meckel K, Kelso M, et al. . Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition augments endogenous antitumor immunity by reducing myeloid-derived suppressor cell function. J Exp Med. 2006;203(12):2691-2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brimnes MK, Vangsted AJ, Knudsen LM, et al. . Increased level of both CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and CD14+HLA-DR⁻/low myeloid-derived suppressor cells and decreased level of dendritic cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72(6):540-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prabhala RH, Pelluru D, Fulciniti M, et al. . Elevated IL-17 produced by TH17 cells promotes myeloma cell growth and inhibits immune function in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;115(26):5385-5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Noonan K, Marchionni L, Anderson J, Pardoll D, Roodman GD, Borrello I. A novel role of IL-17-producing lymphocytes in mediating lytic bone disease in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116(18):3554-3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dhodapkar KM, Barbuto S, Matthews P, et al. . Dendritic cells mediate the induction of polyfunctional human IL17-producing cells (Th17-1 cells) enriched in the bone marrow of patients with myeloma. Blood. 2008;112(7):2878-2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paiva B, Azpilikueta A, Puig N, et al. . PD-L1/PD-1 presence in the tumor microenvironment and activity of PD-1 blockade in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2015;29(10):2110-2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guillerey C, Ferrari de Andrade L, Vuckovic S, et al. . Immunosurveillance and therapy of multiple myeloma are CD226 dependent. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(5):2077-2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suen H, Brown R, Yang S, et al. . Multiple myeloma causes clonal T-cell immunosenescence: identification of potential novel targets for promoting tumour immunity and implications for checkpoint blockade. Leukemia. 2016;30(8):1716-1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ponzetta A, Benigni G, Antonangeli F, et al. . Multiple Myeloma Impairs Bone Marrow Localization of Effector Natural Killer Cells by Altering the Chemokine Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2015;75(22):4766-4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.El-Sherbiny YM, Meade JL, Holmes TD, et al. . The requirement for DNAM-1, NKG2D, and NKp46 in the natural killer cell-mediated killing of myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(18):8444-8449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carbone E, Neri P, Mesuraca M, et al. . HLA class I, NKG2D, and natural cytotoxicity receptors regulate multiple myeloma cell recognition by natural killer cells. Blood. 2005;105(1):251-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Soriani A, Zingoni A, Cerboni C, et al. . ATM-ATR-dependent up-regulation of DNAM-1 and NKG2D ligands on multiple myeloma cells by therapeutic agents results in enhanced NK-cell susceptibility and is associated with a senescent phenotype. Blood. 2009;113(15):3503-3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frohn C, Höppner M, Schlenke P, Kirchner H, Koritke P, Luhm J. Anti-myeloma activity of natural killer lymphocytes. Br J Haematol. 2002;119(3):660-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dhodapkar MV, Richter J. Harnessing natural killer T (NKT) cells in human myeloma: progress and challenges. Clin Immunol. 2011;140(2):160-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chang DH, Deng H, Matthews P, et al. . Inflammation-associated lysophospholipids as ligands for CD1d-restricted T cells in human cancer. Blood. 2008;112(4):1308-1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nair S, Boddupalli CS, Verma R, et al. . Type II NKT-TFH cells against Gaucher lipids regulate B-cell immunity and inflammation. Blood. 2015;125(8):1256-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Richter J, Neparidze N, Zhang L, et al. . Clinical regressions and broad immune activation following combination therapy targeting human NKT cells in myeloma. Blood. 2013;121(3):423-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spanoudakis E, Hu M, Naresh K, et al. . Regulation of multiple myeloma survival and progression by CD1d. Blood. 2009;113(11):2498-2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Noonan K, Borrello I. The immune microenvironment of myeloma. Cancer Microenviron. 2011;4(3):313-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guillerey C, Nakamura K, Vuckovic S, Hill GR, Smyth MJ. Immune responses in multiple myeloma: role of the natural immune surveillance and potential of immunotherapies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(8):1569-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ghobrial IM. Myeloma as a model for the process of metastasis: implications for therapy. Blood. 2012;120(1):20-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Roccaro AM, Mishima Y, Sacco A, et al. . CXCR4 Regulates Extra-Medullary Myeloma through Epithelial-Mesenchymal-Transition-like Transcriptional Activation. Cell Reports. 2015;12(4):622-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Purschke WG, et al. . SDF-1 inhibition targets the bone marrow niche for cancer therapy. Cell Reports. 2014;9(1):118-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ng AC, Khosla S, Charatcharoenwitthaya N, et al. . Bone microstructural changes revealed by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography imaging and elevated DKK1 and MIP-1α levels in patients with MGUS. Blood. 2011;118(25):6529-6534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Melton LJ III, Rajkumar SV, Khosla S, Achenbach SJ, Oberg AL, Kyle RA. Fracture risk in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(1):25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bataille R, Chappard D, Marcelli C, et al. . Recruitment of new osteoblasts and osteoclasts is the earliest critical event in the pathogenesis of human multiple myeloma. J Clin Invest. 1991;88(1):62-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bataille R, Chappard D, Basle MF. Quantifiable excess of bone resorption in monoclonal gammopathy is an early symptom of malignancy: a prospective study of 87 bone biopsies. Blood. 1996;87(11):4762-4769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Silbermann R, Roodman GD. Myeloma bone disease: Pathophysiology and management. J Bone Oncol. 2013;2(2):59-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giuliani N, Bataille R, Mancini C, Lazzaretti M, Barillé S. Myeloma cells induce imbalance in the osteoprotegerin/osteoprotegerin ligand system in the human bone marrow environment. Blood. 2001;98(13):3527-3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Han JH, Choi SJ, Kurihara N, Koide M, Oba Y, Roodman GD. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha is an osteoclastogenic factor in myeloma that is independent of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand. Blood. 2001;97(11):3349-3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yaccoby S, Wezeman MJ, Henderson A, et al. . Cancer and the microenvironment: myeloma-osteoclast interactions as a model. Cancer Res. 2004;64(6):2016-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tian E, Zhan F, Walker R, et al. . The role of the Wnt-signaling antagonist DKK1 in the development of osteolytic lesions in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(26):2483-2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ehrlich LA, Chung HY, Ghobrial I, et al. . IL-3 is a potential inhibitor of osteoblast differentiation in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;106(4):1407-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xu S, Evans H, Buckle C, et al. . Impaired osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from multiple myeloma patients is associated with a blockade in the deactivation of the Notch signaling pathway. Leukemia. 2012;26(12):2546-2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pinzone JJ, Hall BM, Thudi NK, et al. . The role of Dickkopf-1 in bone development, homeostasis, and disease. Blood. 2009;113(3):517-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lawson MA, McDonald MM, Kovacic N, et al. . Osteoclasts control reactivation of dormant myeloma cells by remodelling the endosteal niche. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Roussou M, Tasidou A, Dimopoulos MA, et al. . Increased expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha on trephine biopsies correlates with extensive bone disease, increased angiogenesis and advanced stage in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23(11):2177-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Drake MT. unveiling skeletal fragility in patients diagnosed with MGUS: no longer a condition of undetermined significance? J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(12):2529-2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pecherstorfer M, Seibel MJ, Woitge HW, et al. . Bone resorption in multiple myeloma and in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: quantification by urinary pyridinium cross-links of collagen. Blood. 1997;90(9):3743-3750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA, Sezer O, et al. ; International Myeloma Working Group. The use of biochemical markers of bone remodeling in multiple myeloma: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Leukemia. 2010;24(10):1700-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tanno T, Lim Y, Wang Q, et al. . Growth differentiating factor 15 enhances the tumor-initiating and self-renewal potential of multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2014;123(5):725-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Maiso P, et al. . BM mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitate multiple myeloma progression. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1542-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rajkumar SV, Mesa RA, Fonseca R, et al. . Bone marrow angiogenesis in 400 patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, multiple myeloma, and primary amyloidosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(7):2210-2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Moschetta M, Mishima Y, Kawano Y, et al. . Targeting vasculogenesis to prevent progression in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2016;30(5):1103-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zojer N, Ludwig H, Fiegl M, Stevenson FK, Sahota SS. Patterns of somatic mutations in VH genes reveal pathways of clonal transformation from MGUS to multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;101(10):4137-4139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Robbiani DF, Bothmer A, Callen E, et al. . AID is required for the chromosomal breaks in c-myc that lead to c-myc/IgH translocations. Cell. 2008;135(6):1028-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Walker BA, Wardell CP, Murison A, et al. . APOBEC family mutational signatures are associated with poor prognosis translocations in multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. ; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative; ICGC Breast Cancer Consortium; ICGC MMML-Seq Consortium; ICGC PedBrain. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500(7463):415-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cowan G, Weston-Bell NJ, Bryant D, et al. . Massive parallel IGHV gene sequencing reveals a germinal center pathway in origins of human multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(15):13229-13240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sottoriva A, Kang H, Ma Z, et al. . A Big Bang model of human colorectal tumor growth. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):209-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Greaves M. Evolutionary determinants of cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(8):806-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mills JR, Kohlhagen MC, Dasari S, et al. . Comprehensive Assessment of M-Proteins Using Nanobody Enrichment Coupled to MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2016;62(10):1334-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Das R, Strowig T, Verma R, et al. . Niche-dependent growth of malignant and pre-neoplastic plasma cells in humanized mice. Annual Meeting of American Soicety of Hematology Abstracts. Blood. 2015:120a. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mistry PK, Taddei T, vom Dahl S, Rosenbloom BE. Gaucher disease and malignancy: a model for cancer pathogenesis in an inborn error of metabolism. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18(3):235-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nair S, Branagan AR, Liu J, Boddupalli CS, Mistry PK, Dhodapkar MV. Clonal Immunoglobulin against Lysolipids in the Origin of Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(6):555-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pavlova EV, Archer J, Wang S, et al. . Inhibition of UDP-glucosylceramide synthase in mice prevents Gaucher disease-associated B-cell malignancy. J Pathol. 2015;235(1):113-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Landgren O, Katzmann JA, Hsing AW, et al. . Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among men in Ghana. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(12):1468-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Buadi F, Hsing AW, Katzmann JA, et al. . High prevalence of polyclonal hypergamma-globulinemia in adult males in Ghana, Africa. Am J Hematol. 2011;86(7):554-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Landgren O, Rajkumar SV, Pfeiffer RM, et al. . Obesity is associated with an increased risk of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among black and white women. Blood. 2010;116(7):1056-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Landgren O, Shim YK, Michalek J, et al. . Agent Orange Exposure and Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance: An Operation Ranch Hand Veteran Cohort Study. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(8):1061-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lwin ST, Olechnowicz SW, Fowler JA, Edwards CM. Diet-induced obesity promotes a myeloma-like condition in vivo. Leukemia. 2015;29(2):507-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. . Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1362-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kristinsson SY, Björkholm M, Andersson TM, et al. . Patterns of survival and causes of death following a diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a population-based study. Haematologica. 2009;94(12):1714-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Gregersen H, Ibsen J, Mellemkjoer L, Dahlerup J, Olsen J, Sørensen HT. Mortality and causes of death in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Br J Haematol. 2001;112(2):353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fermand JP, Bridoux F, Kyle RA, et al. ; International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group. How I treat monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS). Blood. 2013;122(22):3583-3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]