Abstract

Nuclear receptors are transcription factors which sense changing environmental or hormonal signals and effect transcriptional changes to regulate core life functions including growth, development, and reproduction. To support this function, following ligand-activation by xenobiotics, members of subfamily 1 nuclear receptors (NR1s) may heterodimerize with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to regulate transcription of genes involved in energy and xenobiotic metabolism and inflammation. Several of these receptors including the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), the pregnane and xenobiotic receptor (PXR), the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), the liver X receptor (LXR) and the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) are key regulators of the gut:liver:adipose axis and serve to coordinate metabolic responses across organ systems between the fed and fasting states. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease and may progress to cirrhosis and even hepatocellular carcinoma. NAFLD is associated with inappropriate nuclear receptor function and perturbations along the gut:liver:adipose axis including obesity, increased intestinal permeability with systemic inflammation, abnormal hepatic lipid metabolism, and insulin resistance. Environmental chemicals may compound the problem by directly interacting with nuclear receptors leading to metabolic confusion and the inability to differentiate fed from fasting conditions. This review focuses on the impact of nuclear receptors in the pathogenesis and treatment of NAFLD. Clinical trials including PIVENS and FLINT demonstrate that nuclear receptor targeted therapies may lead to the paradoxical dissociation of steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and obesity. Novel strategies currently under development (including tissue-specific ligands and dual receptor agonists) may be required to separate the beneficial effects of nuclear receptor activation from unwanted metabolic side effects. The impact of nuclear receptor crosstalk in NAFLD is likely to be profound, but requires further elucidation. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: Xenobiotic nuclear receptors: New Tricks for An Old Dog, edited by Dr. Wen Xie.

Keywords: NAFLD, NASH, TAFLD, TASH, PCBs, PXR, LXR, FXR, CAR, PPAR

1. Introduction

The liver is the largest solid organ in the body, and it is the central location for energy and xenobiotic metabolism. While the regulation of xenobiotic metabolism by nuclear receptors has been described, important roles for nuclear receptors in glucose and lipid metabolism have more recently been determined. Thus, nuclear receptors are critical for normal liver function. Liver disease may be both a cause and a result of metabolic derangements. Fatty liver disease refers to a pathological spectrum of physiological disorders ranging from lipid accumulation in hepatocytes (steatosis) to the development of superimposed inflammation (steatohepatitis) and fibrosis leading to cirrhosis and, potentially, hepatocellular carcinoma. Fatty liver disease is typically caused by exposures to external agents. While disease mechanisms may vary according to the type of exposure, the resulting liver pathology is indistinguishable across etiologies. Thus, fatty liver diseases are named according to their etiology. Common etiologies were recently reviewed [1,2], and include: alcohol (alcoholic liver disease and steatohepatitis —ALD/ASH); diet-induced obesity (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis — NAFLD/NASH); occupational/environmental chemical exposures (toxicant associated fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis —TAFLD/TASH); and chemotherapy associated steatohepatitis (CASH). Of these, NAFLD is the most prevalent, and the primary objective of this review article. However, the impact of xenobiotic environmental chemicals on nuclear receptors in fatty liver disease will be discussed.

The term, NASH, was initially coined in 1980 to describe a steatotic and inflammatory liver condition of non-drinking, moderately obese patients which was histologically similar to alcoholic steatohepatitis [3]. NAFLD is now recognized as a widespread and costly problem, affecting up to 25.24% of the global population and 7.6% of children [4, 5]. NAFLD is associated with obesity, diabetes, and systemic inflammation and represents the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome [2]. Diabetes is associated with more severe NAFLD. However, this association is complex, as NAFLD, in turn, worsens diabetes and drives systemic inflammation. A ‘two-hit’ model has been proposed to explain why some, but not all, individuals with steatosis develop progressive liver disease and NASH [6]. In addition to diabetes, other second hit mechanisms (oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, etc.) have been extensively reviewed [1,2], but surprisingly few groups have reviewed the emerging role of nuclear receptors in NASH pathogenesis [7–10]. More recently, the adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework has been used to contextualize the role of nuclear receptors in hepatic steatosis [11,12]. Likewise, the importance of other organs on NASH (e.g., the gut:liver:adipose axis) has recently been recognized, and the systemic impact of nuclear receptors on NAFLD will be reviewed.

In humans, there are 48 nuclear receptors categorized into 7 subfamilies designated as NR0–NR6 [10]. In general, nuclear receptors are ligand-dependent transcription factors that regulate cellular machinery impacting/effecting epigenetic changes to control transcription. Of particular importance in NAFLD are specific members of the NR1 subfamily which are generally retained in the nucleus and heterodimerize with the retinoid X receptor (RXRα, β, γ — NR2B1, NR3B2, NR2B3) [7–12]. These transcription factors include NR1C1–3 (the peroxisome proliferator activated receptors α, β, γ — PPAR); NR1H2–3 (the liver X receptors α, β — LXR); NR1H4 (the farnesoid X receptor α — FXR); NR1I2 (the constitutive androstane receptor — CAR); and NR1I3 (the pregnane X receptor — PXR). In general, these receptors bind with low affinity to hydrophobic dietary ligands to coordinate nutrient homeostasis [10]. These permissive receptors recruit co-activators if either they or their RXR binding partner are liganded. However, the transcriptional signal is amplified when both binding partners are liganded. The boosting effect of liganded RXR allows these NR1 receptors to exert significant transcriptional changes following even low-level dietary exposures [10]. However, when unliganded, NR1 receptors may also ‘switch off’ transcription by recruiting co-repressors. Nuclear receptor cistromes are complex and vary by tissue and disease state [10]. A typical nuclear receptor cistrome may consist of 10,000–25,000 binding sites within 250–1000 genes in a cell [10]. Illustrating the plasticity of hepatic NR1 binding sites, stellate cell binding sites for the vitamin D receptor (VDR)/RXR heterodimer increased from 6281 to 24,984 following activation from a quiescent state [13]. Other nuclear receptors not discussed in this review are potentially important in NASH pathogenesis and therapy. These include the Rev-Erbs (NR1D1–D2) and the retinoic acid receptor-related receptors (ROR, NR1F1–3) receptors, whose roles in hepatic metabolism and inflammation were recently reviewed [14].

The PIVENS and FLINT studies investigated nuclear receptor agonist therapies for biopsy-proven NASH, and clearly demonstrated the importance of NR1 receptors in this disease state [15,16]. In the PIVENS trial, NASH patients treated with the PPARγ agonist, pioglitazone, achieved improvements in steatosis, hepatic lobular inflammation and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) even though obesity worsened. In the more recently published FLINT study, NASH patients were treated with obeticholic acid (OCA), a selective FXR agonist [15]. While obesity, steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis improved, hypercholesterolemia worsened. Importantly, these studies demonstrate that nuclear receptor targeted therapies may lead to the paradoxical dissociation of steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and obesity in NAFLD.

Recently, Evans and Mangelsdorf described how the RXR-partnered nuclear receptors coordinate the “energy vector” of nutrient homeostasis along the gut:liver:adipose axis between the fed and fasting states [10]. In the fed state, FXR, LXR, and PPARβ/δ,γ are primarily involved in nutrient acquisition from the gut and distribution through the liver to peripheral tissues including adipose and muscle. After meals, FXR activation by bile acids promotes nutrient absorption, which is an energy vector facilitating transfer of nutrients from the intestinal lumen to the liver while maintaining a barrier to the gut microbiome. Energy in the form of triacylglycerol is then exported from the liver to peripheral tissues and excess cholesterol is removed from the body by reverse cholesterol transport under the regulation of FXR-stimulated fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) and/or activation of hepatic LXR by oxysterols. In peripheral tissues, excess nutrients are either consumed by muscle or stored by adipose tissue under the regulation of PPARδ,γ. Post-prandial hepatic activation of PXR and CAR promotes the clearance of toxic dietary metabolites, drugs, and endobiotics through phase I, II, and III xenobiotic metabolism. In the fasting state, the energy vector is reversed, as stored energy is metabolized from the adipose tissue. Hepatic PPARα activation results in the production of ketone bodies and production of the hepatokine, fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), which serves as a stress signal to prepare other sites in the body for energy-deprivation. Because the gut:liver:adipose axis is central to NAFLD pathogenesis, the “Energy Vector” hypothesis provides a framework to understand how nuclear receptor dysregulation contributes to steatohepatitis (Table 1). This manuscript reviews the roles of key NR1 receptors including PPAR, PXR, CAR, LXR, and FXR in NAFLD.

Table 1.

Mechanistic impact of selected nuclear receptors in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

| Receptor | Primary tissue | Natural agonists | Hepatic steatosis | Hepatic inflammation | Hepatic fibrosis | Insulin resistance | Obesity | Cholesterol | Gut permeability | Associated hormones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPARα | Liver | Free fatty acids Eicosanoids | ↓ [58] | ↓ [19,58] | ↓ [239]* | ↓ [240] | ↓ [240] | ↓ [241] | ↓ [242]* | ↑ FGF21 [25] |

| PPARβ/δ | Muscle | Free fatty acids Eicosanoids | ↓ [58] | ↓ [19,58] | ↑ [243]* | ↓ [36,37] | ↓ [36,37] | ↓ [241] | ↓ [244,245]* | |

| PPARγ | Adipose | Prostaglandins Eicosanoids | ↓ [16,58] | ↓ [16,19,58] | ↔ [16,61]* | ↓ [16,61] | ↑ [16] | ↔ [241] | ↓ [246] | ↑ Adiponectin [32] |

| PXR | Liver Intestine | Xenobiotics Steroids | ↑ [79–81]* | ↓ [98] | ↓ [68]* | ↑ [80,96]* | ↑ [80,81] | ↑ [80] | ↓ [97] | ↑ FGF19 [99] |

| CAR | Liver | Xenobiotics Steroids | ↓ [137] | ↓ [145] | ↔ [150]* | ↓ [138,140,143] | ↓ [138] | ↓ [141] | ↓ [247]* | |

| LXRα,β | Liver | Oxysterols | ↑ [248] | ↓ [178] | ↑ [182]* | ↓ [177] | ↑ [168] | ↓ [171] | ↓ [249,250]* | ↓ FGF21 [172] |

| FXRα | Liver Intestine | Bile acids | ↓ [15] | ↓ [15] | ↓ [15] | ↓ [206]* | ↓ [200] | ↑ [15] | ↓ [218] | ↑ FGF19 [190–192] ↑ FGF21 [193] ↑ Adiponectin [194] |

Abbreviations: CAR, constitutive androstane receptor (NR1I3); FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FXRα, farnesoid X receptor α (NR1H4); LXRα,β, liver X receptor α,β (NR1H2,3); PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (NR1C1); PPARδ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ (NR1C2); PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (NR1C3); PXR, pregnane X receptor (NR1I2).

denotes controversial or more limited data.

↔ denotes no effect. Blank cell denotes no characterized associated hormones.

2. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α, β/δ, and γ

2.1. PPAR overview

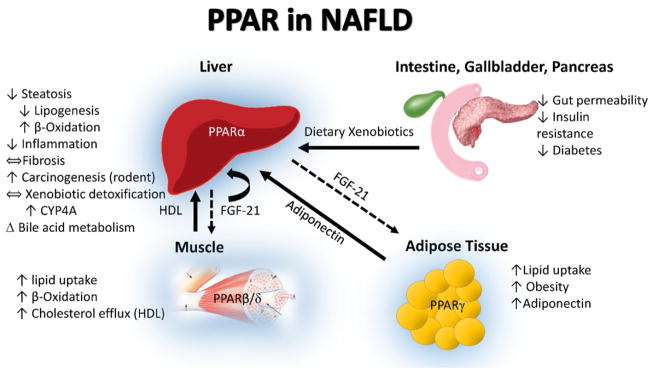

The peroxisome proliferator activated receptor subfamily members act as major regulators of lipid metabolism in many cell types. The receptor subfamily is named after the discovery of Issemann & Green [17] who cloned the first PPAR gene and demonstrated that the receptor was activated by a set of ligands, such as the drugs nafenopin and WY-14643, which were known to cause peroxisome proliferation (PP) in rodent liver. The PP linked to PPARα activation was subsequently characterized by chemically-induced hepatomegaly, increased size and number of peroxisomal bodies in liver, and increased expression of genes of fatty acid oxidation [18]. The subfamily of NRC1 receptors contains three distinct forms in humans and rodents: PPARα (NR1C1, ubiquitous tissue localization but high in liver), PPARβ/δ (NR1C2, ubiquitous including muscle, adipose tissue, and liver), and PPARγ (NR1C3) [10]. PPARγ has three splice variant isoforms (γ1, γ2, and γ3) that display differences in tissue localization for each isoform; γ1 (ubiquitous tissue localization), γ2 (localized principally to adipose tissue), and γ3 (localized to macrophages, colon, and adipose tissue). PPARs are heavily involved in the gut:liver:adipose axis by serving in liver (PPARα) to upregulate β-oxidation and cholesterol elimination during the fasted state, or the state in which lipid mobilization is activated by foreign chemicals in peripheral tissues such as adipose and muscle (Fig. 1, Table 1) [10]. Hepatic PPARα expression is low in NAFLD, but increases in parallel with histologic improvement following diet/exercise therapy [19,20]. This decrease in PPARα mRNA protein levels during high fat diet-feeding leading to steatosis was also observed in a murine model of steatosis and is accompanied by an increase in PPARδ mRNA and protein [21]. These changes diminish fatty acid oxidation while stimulating lipogenesis. Studies of the molecular regulation of these phenomena in humans and mice are needed. PPARβ/δ activation in the muscle/adipose during the fed state or exercise leads to increased fuel consumption in muscle, again via β-oxidation, while its hepatic activation may increase nutrient delivery from the liver to peripheral tissues [10]. Likewise, peripheral PPARγ activation during the fed state leads to increased fuel storage primarily in adipose tissue [10]. In addition, PPARs suppress inflammation in the obese state, through action on nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) and activator protein 1 (AP1) transcription factors, and coordinate metabolism via transcription of the adipokine, adiponectin (by PPARγ), and the hepatokine, FGF21 (by PPARα and FXR). In general, PPAR activation is thought to be beneficial in NASH, and clinical trials of single/dual receptor agonists are underway. The impact of PPAR in NAFLD is summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PPAR in NAFLD. The peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPAR) are activated by free fatty acids, specific eicosanoids, and dietary xenobiotics. The principle role of hepatic PPARα is to upregulate lipid oxidation in the fasting state, while inducing fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21). In the fed state, PPARβ/δ promotes lipid uptake and oxidation in skeletal muscle; while PPARγ promotes lipid uptake and storage in adipose tissue, while inducing adiponectin expression. The blue highlight around the liver, muscle and adipose is indicative of the tissues in which PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ are highly expressed.

2.2. PPAR molecular function

The optimal response elements for PPARs normally are direct repeats of AGGTCA separated by a single nucleotide, termed a direct repeat 1 (DR1). Free fatty acids and eicosanoids (including 15-hydroxy-eicosanoids [22] and leukotriene B4 [23]) have been shown to be the major endogenous activating ligands for PPARα and PPARβ/δ, while PPARγ is specifically activated by the prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2) and members of the 5-hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE) family of arachidonic acid metabolites including 5-oxo-15(S)-HETE and 5-oxo-ETE. Many exogenous PPARα ligands exist, both pharmaceutical and environmental. A series of fibric acid derivatives was developed as pharmaceutical agents capable of lowering levels of free fatty acids, triglycerides and cholesterol in the plasma of humans. Extensive study of the fibrate class of drugs in rodents led to some understanding of the role of PPARs in lipid metabolism [18], and many PP agents have since been shown to lower insulin resistance and the dyslipidemia associated with the metabolic syndrome. In a similar manner, PP agents have been shown to provide protection against the development of NAFLD, most likely by increasing the rate of catabolism of fatty acids and inducing enzyme systems protective against oxidative stress, in part via PPARα-dependent mechanisms [24]. PPARα upregulates several genes involved in oxidative lipid metabolism, including the classic examples of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1), pyruvate dehydrogenase lipoamide kinase isozyme 4 mitochondrial (PDK4), CYP4A, and acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (ACOX1). These actions allow PPARα to function as a major regulator in the hepatic processes of fatty acid uptake, mitochondrial and peroxisomal β-oxidation, ketogenesis, triglyceride turnover and bile acid synthesis while coordinating these processes with peripheral tissues via FGF21 [25]. Several environmental PPARα agonists have been identified including pesticides (diclofap-methyl, pyrethins, and imazalil), phthalate esters (diethylhexyl phthalate, DEHP), and aldehyde metabolites of chlorinated solvents including perchloroethylene (PCE) and trichloroethylene (TCE) [26–29]. Important species-specific differences exist concerning the effects of these environmental chemicals on hepatic steatosis [29].

The ubiquitous nature of the PPARs in many tissues has led to some ambiguity as to which receptor regulates key target genes in liver, adipocytes, myocytes, and immune cells. PPARγ isoforms are less well characterized in their function, except in the adipocyte, where they are highly expressed and serve as key regulatory transcription factors for adipocyte development and adipogenesis [30]. Yet, there also appears to be a role for PPARα in the adipocyte and in atherosclerosis as well [31]. An important effector hormone of adipocyte PPARγ activation is the insulin sensitizing adipokine, adiponectin, which has been shown to be hepatoprotective in NASH [32]. Exogenous PPARγ ligands include thiazolidinediones and the obesogens tributyltin and bisphenol A [33].

PPARβ/δ has been shown to have roles in muscle, liver, skin and adipose, including decreasing apoptosis, down-regulation of genes encoding AhR-dependent foreign compound metabolism during oxidative stress [34], and decreasing adiposity. The levels of PPARβ/δ are far higher in muscle than the other two forms of the receptor in both rodents and humans [35]. In obese monkeys, it has been shown that treatment with the PPARβ/δ agonist GW1516 for 4 weeks resulted in normalization of insulin and triacylglycerol blood levels, increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and decreased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Similar results have been observed in diet-induced and genetically obese mice, resulting in increased insulin sensitivity and decreased adiposity [36,37].

Studies in mice with NAFLD suggest that a specific PPARα,δ dual agonist, GFT505, protects against progression of the disease. A phase IIb clinical trial (GOLDEN 505) of this agent for NASH was recently completed, although the results are yet to be published. The actions of all three PPARs suggest similar regulatory control in many tissues, but their function may be regulated by secondary cell- and tissue-specific co-activating transcription factors, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) and CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBP) [31]. Development of receptor-specific chemical inhibitors and activators, as well as PPARα and PPARβ/δ null transgenic mice [38], has recently allowed some discrimination between PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ independent actions in various tissue compartments.

2.3. Role of PPAR in hepatic steatosis and metabolism

Because PPARα is known to be activated as a gene-specific transcription factor by free fatty acids and other lipids to enhance lipid clearance in the liver, it is not surprising that PPARα may play a role in blunting the effects of high fat diet and other conditions leading to steatosis [18]. Animals treated with PPARα activators have long been known to display lower weight gain than their controls, and many other health improvements, such as prevention of atherosclerosis, beneficial enhanced coat and skin coloring, and lower levels of fat stored in the epididymal fat pads [31,39]. Although PPARγ is expressed in white adipose tissue in higher levels than PPARα [40], studies have shown that adipocytes from PPARα ablated mice display abnormal triacylglycerol storage [41,42]. A number of animal models have been developed utilizing dietary deficiencies in methionine and choline content, or high fat diets as models for steatosis [18,43,44] and steatohepatitis [44]. In these studies, the measures of steatosis and steatohepatitis in mice models are strikingly ameliorated via PPARα activation by therapeutic agents [45,46], and this protective effect is lost in PPAR knockouts. Several studies in mice support the possibility that both PPARβ/δ and PPARγ attenuate the severity of steatosis in mice [47–50]. To date, the use of fibrates or other PPARα agonists in the treatment of steatosis in humans has proven relatively ineffective against NAFLD [19,51]. Steatosis, however, was significantly improved by the PPARγ agonist, pioglitazone, in the PIVENS study [16]. With the advent of pharmaceutical agents with mixed agonist activity toward both PPARα and PPARβ/δ, some promise of an effective therapy against steatohepatitis and steatosis seems possible [52,53], and clinical trials are underway.

2.4. Role of PPAR in hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer

Steatohepatitis is characterized by the development of inflammation and fibrosis. PPARα has been shown to suppress inflammation caused by cytokine production in the liver. For example, the activation of NFκB, leading to nuclear translocation and subsequent DNA binding of this inflammatory transcription factor, is blunted by the action of PPARα [31,54,55]. Activation or expression of c-Jun or p65 and their nuclear translocation are also prevented by the action of PPARα [54–57]. PPARα activation leads to a reduction in the formation of nuclear C/EBP/p50-NFκB complexes, and thereby reduces C-reactive protein promoter activation [58]. Fibrinogen-β, a pro-coagulant factor, is repressed by fibrates, acting via PPARα, which interferes with the C/EBPβ pathway through promoter-specific titration of the coactivator glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein-1/transcriptional intermediary factor 2 (GRIP1/TIF2). Moreover, PPARα increases NFκB inhibitor alpha (IκBα) expression, thus preventing nuclear p50/p65 NFκB translocation and ameliorating its nuclear transcriptional activity. Chronic treatment with fibrates decreases hepatic C/EBPβ and p50-NFκB protein expression in mice in a PPARα-dependent manner [59]. This latter effect likely contributes to the generalized anti-inflammatory effects of peroxisome proliferators on the expression of a wide range of acute phase response genes containing response elements for these transcription factors. In a similar manner, the activity of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor, C/EBPα, is decreased by PPARγ activation [60], because it sequesters GRIP1/TIF2.

PPAR activation may also attenuate fibrosis. Human subjects with NASH who were treated with pioglitazone (PPARγ agonist) had dramatically improved fibrosis biomarkers [61], although histological fibrosis was not improved in the PIVENS study. Prolonged PPARα activation leads to hepatocellular carcinoma in mice and rats [62], but not in humans. This phenomenon has been shown to be due to murine PPARα-specific negative regulation of Let7-c microRNA function eventually leading to inactivation of cMyc [63]. This negative miRNA regulation was not observed in mice humanized with hPPARα, which is known not to regulate Let7-c expression [64]. Thus, there is a subset of genes in mice that are regulated by murine PPARα leading to hepatocellular carcinoma formation, yet these targets are not regulated by human PPARα activated by peroxisome proliferating agents. In addition, the levels of PPARα protein and its action are slightly attenuated in human liver [65], relative to mouse or rat liver, presumably causing differences in PP in humans vs. rodents.

3. Pregnane X receptor

3.1. PXR overview

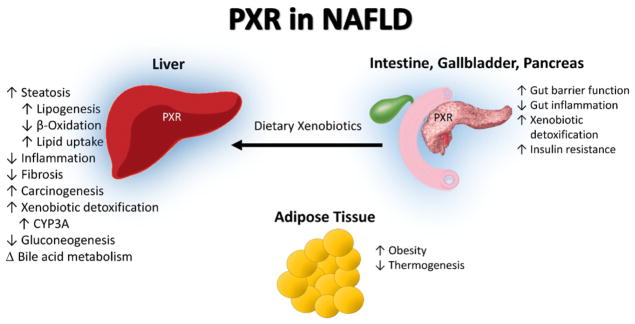

The pregnane X receptor is also known as the steroid and xenobiotic sensing nuclear receptor (SXR). PXR is encoded by the NR1I2 gene which, in humans, is located at 3q12–q13.3. This gene spans 35 kb and consists of 9 exons, exons 2–9 of which encode the 434 amino acid protein [66]. Though it is most abundant in the liver and gut, PXR is expressed in many tissues, including human breast, intestine, adrenal gland, bone marrow, and brain [67]. Within the liver, PXR is expressed not only in hepatocytes, but also in stellate and Kupffer cells [68,69]. Numerous variants of the NR1I2 gene have been described in humans, and at least two NRL1I2 polymorphisms, rs7643645/G and rs2461823, have been associated with increased severity of NAFLD [70]. Another variant has been reported which encodes a short (37 kDa) dominant negative PXR isoform which represses the function of full-length PXR, likely through competition for cofactors such as steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC-1) [71]. PXR functions as a sensor for a vast array of exogenous chemical toxicants, coupling cellular metabolic and detoxification programs to respond to an ever-changing environment [72,73]. In keeping with this classically understood role, the first discovered and prototypical PXR target was the cytochrome p450 oxygenase CYP3A4 [74]. More recently, the spectrum of known PXR transcriptional targets has expanded to include those involved in energy homeostasis. In the fed state, PXR affects lipid and xenobiotic transporter expression to maintain selective barriers, and simultaneously coordinates phase I and II enzymes to metabolize both toxic and nutritive molecules in the gut and liver [75–78]. The role of PXR in the gut:liver:adipose axis in NAFLD (Fig. 2, Table 1) is complex. In vitro models have shown that both PXR activation and knockout may lead to hepatic steatosis, presumably due to opposing effects of liganded PXR on its transcriptional targets and unliganded PXR on other metabolic effector proteins [79]. However, the impact of PXR knockout on hepatic steatosis is controversial because knockouts generated in some laboratories demonstrated protection against HFD-induced hepatic lipid accumulation [80], while others showed increased hepatic triglyceride accumulation with control diet and no differences between genotypes with HFD [81]. Nonetheless, PXR is anti-inflammatory and may reduce hepatic fibrogenesis, but PXR activation has been associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and hypercholesterolemia.

Fig. 2.

PXR in NAFLD. The pregnane X receptor (PXR) is activated in the intestine by dietary intake of exogenous ligands and commensal bacterial production of indoles and other activating compounds. The principle role of PXR in the intestine is to maintain barrier function and reduce inflammation, as well as to regulate intestinal transcription of metabolic enzymes. Hepatic PXR activation regulates phase I–III xenobiotic detoxification as well as modulating glucose and fatty acid metabolism. The weight of evidence indicates that PXR activation worsens obesity, steatosis, and insulin resistance while decreasing hepatic inflammation and fibrosis, even though PXR is not expressed in adipose tissue. The blue highlight around the liver, intestine, gall bladder, and pancreas is indicative of the tissues PXR is highly expressed in.

3.2. PXR molecular function

Ligands for human PXR are legion and include both xenobiotics (medications such as rifampicin and environmental pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls — PCBs) and endobiotics (bile acids, steroids, and other cholesterol derivatives) [82–85]. Consistent with the diversity of PXR ligands, PXR’s ligand binding domain is unusually large and flexible. The ligand binding domains of related nuclear receptors are comprised of 7α-helices arranged into three layers and a stranded β-sheet. In PXR, a 60-residue insertion yields an additional 2 β-strands in the binding pocket which, along with a disordered region immediately adjacent to the binding domain, contributes to the extraordinary ligand diversity of this receptor. The binding pocket of PXR is also relatively hydrophobic, with a small number of polar residues spaced throughout. Variations in these residues appear to underlie the species-specific response of PXR to prototypical ligands [82], while van der Waals forces contribute to ligand potency [86].

In general, PXR recognizes DR3 and DR4 sequences as well as everted repeats separated by 6 or 8 base pairs (ER6 and ER8, respectively) [87]. In addition to the classic P450 targets, gene targets of PXR include: lipogenic enzymes such as stearoyl CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), fatty acid elongase, the fatty acid transporter CD36 [88,89]; and the mono- and di-carboxylate transporter solute carrier family 13 member 5 (SLC13A5), which regulates hepatocellular influx of citrate (an important precursor of fatty acids), isoprenoid and cholesterol [90]. In many cases, PXR also regulates other transcription factors involved in metabolic homeostasis, such as sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP1) and PPARα itself, providing both direct and indirect transcriptional influence over PPAR targets [88]. PXR participates in protein–protein interactions with other transcriptional regulators of metabolism [91] and competes for common cofactors [92]. Recently, Biswas et al. reported that the transcriptional and phenotypic effects of rifampicin (a known PXR ligand) are ablated by compounds which inhibit sirtuin-1 (SIRT1)-driven deacetylation of PXR, suggesting that post-translational modification of PXR is required for its ligand response [93]. Other post-translational modifications of PXR, such as sumoylation and ubiquitination, are proposed to be related to PXR’s repression of β-oxidation, inhibition of gluconeogenesis and reduction of inflammation.

3.3. Role of PXR in hepatic steatosis and metabolism

Although there is some evidence to the contrary, the weight of evidence suggests that PXR activation worsens steatosis, obesity, insulin resistance, and hypercholesterolemia. Generally speaking, activation of PXR has been associated with increased hepatic fatty acid and fatty acid precursor uptake, lipogenesis, and decreased β-oxidation [76,81, 90]. In human tumor-derived HepG2 cells, both ligand activation and knockdown of PXR led to increased lipid accumulation [79]. In whole-animal models, the role of PXR in steatosis becomes even more complex. PXR knockout animals generated in different laboratories have distinct phenotypes with regard to steatosis, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction. In one such study, deletion of exons 2 and 3 of the murine PXR, corresponding to amino acid residues 63–170 of the DNA-binding domain, resulted in complete loss of ligand-inducible PXR transactivation of the Cyp3A target gene [94]. In a mouse model of diet-induced obesity, this knockout strategy reduced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance by increasing oxygen consumption and mitochondrial β-oxidation, by inhibiting hepatic lipogenesis, and by sensitizing hepatic insulin signaling [80]. The same PXR deletion introduced into a model of genetic obesity (ob/ob mice) also increased metabolic expenditure and decreased gluconeogenesis [80]. An independently-generated PXR knockout model was reported to exhibit decreased weight gain on a high-fat diet as well; however, these mice were characterized by impaired glucose tolerance, hypoadiponectinemia, and hyperleptinemia. Examination of these mouse livers showed increased microvesicular steatosis and decreased macrovesicular steatosis, with no net change in hepatic triglycerides [81]. Neither mouse model showed evidence of increased hepatic inflammation with high fat feeding [80,81]. However, humanized PXR mice more consistently exhibit obesity and glucose intolerance when compared to wild-type mice fed a high fat diet [81,95]; and a clinical study reported insulin resistance in volunteers treated with the PXR agonist rifampin [96].

3.4. Role of PXR in hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer

PXR activation is generally anti-inflammatory across many tissues. Intestinal PXR activation by bacterially-produced indoles protects against inflammation-induced gut barrier dysfunction, myeloperoxidase activity, and histologic damage by inhibiting downstream toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-activated kinase activation [97]. Indeed, PXR agonists such as rifampicin have been proposed as therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Although chronic PXR activation induces small increases in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in primary hepatocyte culture, the more immediate and dramatic effect of PXR activation is to block the production of many pro-inflammatory NFκB target genes and to upregulate the production of secreted interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA). This dampens the effects of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation by decreasing production of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and by blocking the effects of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) at the cell surface [98]. PXR also induces the anti-inflammatory enterokine, FGF19 [99]. The inverse relation between PXR and NFκB, may also contribute to PXR’s anti-fibrotic activity. Mouse studies demonstrated that the PXR agonist, pregnenolone 16α-carbonitrile (PCN), attenuated carbon tetrachloride induced liver fibrosis. This likely involved PXR-mediated inhibition of proliferation and trans-differentiation of stellate cells as well as inhibition of transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1)-mediated collagen production [68].

The role of PXR in carcinogenesis, particularly in hepatocellular carcinoma, has been classically explored as a corollary to its role in xenobiotic metabolism. In the case of CYP3A4-mediated activation of the pro-carcinogen aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), conditions which increase the transcriptional activity of PXR and therefore the transcription of its target P450s increase the production of carcinogenic epoxide. The synergistic effects of hepatitis B virus and AFB1 on hepatocarcinogenesis may be explained by PXR-dependent mechanisms as well. Because the HBx protein of the hepatitis B virus interacts with the ligand binding domain of PXR and other nuclear receptors, and increases the transcriptional activity of PXR at the Cyp3A4 promoter [100], it may effectively prime hepatocytes for AFB1 bioactivation and hepatocarcinogenesis. However, the role of PXR in hepatocarcinogenesis resulting from NASH requires further elucidation.

4. Constitutive androstane receptor

4.1. CAR overview

The constitutive androstane receptor (NR1I3) is a single gene, which exists in up to 25 splice variants in a species-specific manner [101]. For example, the three most commonly expressed variants in humans are CAR1–3, but only a single functional isoform exists in mice [102–104]. CAR is unique among the nuclear receptors reviewed in this article because it may be active even in the absence of ligand binding. It has been observed in vitro that CAR1 is a constitutively active receptor while CAR2–3 are ligand-activated [101,105]. The structural variance between these transcripts is due to additional sequences included close to the ligand binding domain that result in ligand-dependent or independent transcriptional activity. Human CAR1–3 are highly expressed in the liver and intestine with lower levels of expression being observed in the heart, muscle, kidneys, and lung [102,103]. Other human variants have been shown to be expressed at very low levels in specific organs. While the ligand-specificity of CAR variants has been demonstrated, the potential effect on target gene expression requires further clarification [106,107].

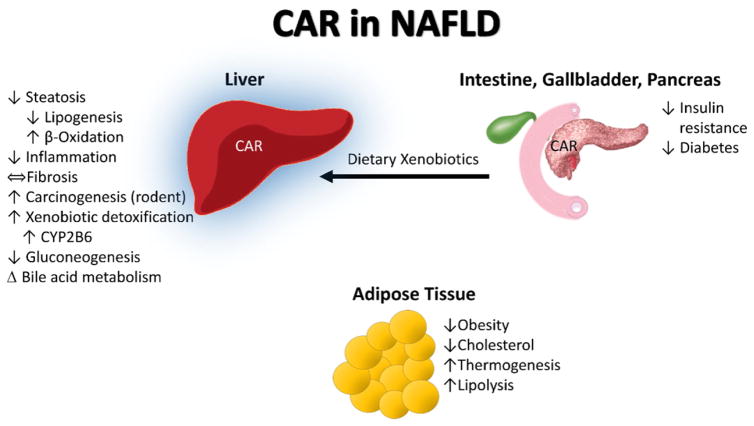

The evolutionary role ascribed to CAR has been protection against toxic dietary contaminants or food metabolites [108,109]. Interestingly, CAR activity has been observed to follow a circadian rhythm in mice. During the day CAR is less active but during the night, when mice eat, CAR is highly active. This demonstrates CAR’s evolutionary role in xenobiotic and energy metabolism in the fed state [110]. Because CAR regulates Phase I–III xenobiotic metabolism, this receptor has become an important determinant of drug–drug interactions in pharmacology [111–114]. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that xenobiotic metabolism and energy metabolism are inter-related. Thus, it is not surprising that new roles have been identified for CAR in carbohydrate/lipid metabolism and even inflammation in NAFLD [115]. CAR has been shown to be more active with increasing NAFLD severity [116,117]. In this case, CAR is believed to be serving a protective role during metabolic stress. More specifically, CAR impacts the liver in the fed state and decreases hepatic steatosis and inflammation while also reducing obesity, insulin resistance, and hypercholesterolemia (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Fig. 3.

CAR in NAFLD. The constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) is activated by dietary xenobiotics in the post-prandial state. The principle role of CAR activation is to upregulate detoxification pathways in the liver to protect the organism against toxic ingestions or dietary metabolites. More recently, CAR activation has also been shown to impact NAFLD as well as energy metabolism in the liver, pancreas, and adipose tissue. CAR activation decreased hepatic steatosis and inflammation while decreasing obesity and diabetes. CAR is highly expressed in the liver (blue highlight).

4.2. CAR molecular function

CAR is constitutively active but its activity can be modified directly through ligand binding or indirectly through changes to CAR’s phosphorylation state [118–120]. CAR is a phosphoprotein, which forms a large cytosolic protein complex with heat shock protein 90 and the cytoplasmic CAR retention protein (CCRP) in the absence of a ligand [121]. Upon dephosphorylation, CAR translocates to the nucleus where it forms a heterodimeric protein complex with RXR that binds canonical responsive elements to transcriptionally regulate multiple xenobiotic metabolizing genes and drug transporters including: CYP2B6, uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosltransferase (UGT), sulfotransferase (SULT), and multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) [112–114,122]. CAR activity is determined by its phosphorylation state which is regulated, in part, by protein kinase C (PKC), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and protein phosphatase 2 (PP2A) [123,124]. While multiple phosphorylation sites exist, threonine-38 is the most well-established [120]. Phenobarbital, is a classically described indirect CAR activator, and it works by modulating the threonine-38 phosphorylation site downstream of its direct interaction with the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [125]. Cytoplasmic CAR retention protein (CCRP) is speculated to have an alternate role as a co-activator of CAR in the nucleus, and CCRP−/− mice develop steatosis which implies that CAR activity may prevent steatosis [126].

The major response element for CAR is the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module (PBREM) which has two DR4 motifs separated by 6 nucleotides [127,128]. The well characterized endogenous ligands of CAR include bilirubin, bile acids, and androstanes [129–132]. Exogenous CAR activators include medications (such as phenobarbital), environmental pollutants (PCBs) and pesticides/pesticide metabolites (methoxychlor, dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene — DDE), and pyrene [84,133–135]. CAR ligands are species-specific which can be attributed to limited conservation of CAR’s ligand binding domain. For example the ligand binding domains of human and murine CAR are only 75% conserved [136].

4.3. Role of CAR in hepatic steatosis and metabolism

CAR activation appears to be beneficial during times of caloric excess. Treatment with CAR agonist TCPOBOP attenuated diet-induced obesity, diabetes, and hepatic steatosis in animal models [137,138]. CAR activation reduced obesity and improved diabetes through diminished liver gluconeogenesis and improved insulin sensitivity [137, 138]. Forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) can be physically inhibited by CAR binding which prevents expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase-1 (PEPCK1) and glucose 6-phosphatase, thus impacting insulin receptor signaling and preventing gluconeogenesis [139]. Suppressed hepatic gluconeogenesis can also be attributed to CAR facilitated ubiquitination and degradation of PGC-1α [140]. Interestingly, murine CAR target gene Cyp2b10 expression was decreased with increasing insulin concentrations [139]. CAR activation decreased plasma cholesterol and triglycerides in low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) knockout mice [141]. Consistent with these effects, CAR activation improved hepatic steatosis by diminishing lipogenesis and inducing β-oxidation in a mouse model [137]. CAR activation was found to upregulate insulin-induced gene 1 protein (INSIG1) which is an anti-lipogenic protein [142]. However, the role of CAR in hepatic steatosis is complex because when CCRP is knocked out, mice developed hepatic steatosis. This effect is speculated to be due to CCRP also being a nuclear co-activator of CAR required for its binding to its target response elements; however, it could be CAR-independent [126]. Interestingly, the generally protective effects of CAR activation against the metabolic syndrome may cross generations. Increased CAR activation in (diet-induced) obese pregnant mice led to decreased insulin resistance and hypertriglyceridemia in offspring while increasing the adiponectin:leptin ratio [143]. While a majority of the studies dealing with CAR agonism in steatosis have shown a beneficial role, there are some conflicting studies demonstrating increased serum lipids and decreased liver β-oxidation with CAR activation in mice [144]. These conflicting studies can be attributed to the various models and CAR activators used.

4.4. Role of CAR in hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer

CAR has anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties in NAFLD, although its potential role in fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis are unclear. In the MCD mouse model of diet-induced NASH, administration of a CAR agonist reduced inflammation and hepatocellular apoptosis, supporting the notion that CAR activation may be beneficial in reducing steatohepatitis [145]. Inflammation has long been known to reduce CYP induction and it is believed to be mediated through NFκB [146]. CAR antagonism increased NFκB target genes in primary hepatocytes [147]. Not only is CAR anti-inflammatory, it also inhibits TNFα-induced apoptosis by increasing expression of the anti-apoptotic protein, growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible beta (GADD45β) [148]. More data are needed to determine the impact of CAR on hepatic fibrosis. While CAR activation attenuated Fas-induced liver injury and hepatic fibrosis [149], it worsened lipid peroxidation and hepatic fibrosis in the MCD NASH mouse model [150].

Similar to PPARα, CAR activation may promote hepatocarcinogenesis in mice [151], although this effect has not been observed in humans. In fact, CAR activation in humans may be anti-proliferative. In the HepaRG human liver cancer cell line, loss of CAR function increased expression of proliferative genes through an uncharacterized mechanism [152]. Indirect CAR activation through EGFR antagonism (e.g. phenobarbital) is likely to be anti-carcinogenic in humans, and may also impact fibrosis via interacting with protein phosphorylation cascades. Interestingly, humanized CAR mice still produce tumors with CAR agonism demonstrating that the tumorigenic effect of CAR activation isn’t solely due to CAR structure but could be due to the genome organization variance between mice and humans [153].

5. Liver X receptor

5.1. LXR overview

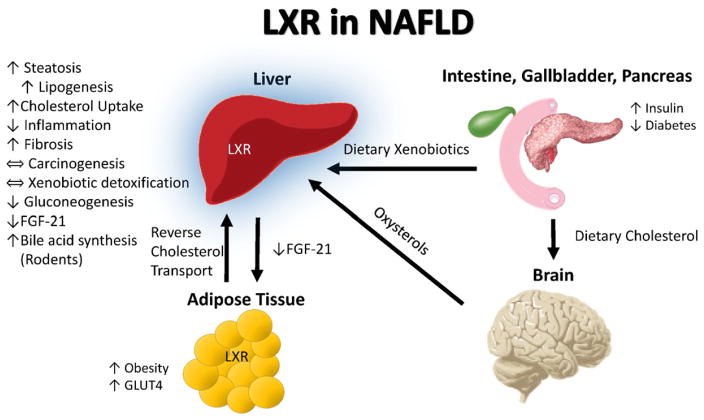

The liver X receptor exists as two variants in humans, namely LXRα (NR1H3) and LXRβ (NR1H2). LXR regulates hepatic triglyceride and cholesterol metabolism in both humans and mice, and regulates bile acid metabolism in mice. Oxysterols are the endogenous LXR ligands. The major sites for oxysterol production are the brain in response to total body cholesterol load and, to a lesser extent, the liver and lung [154]. As both dietary and hepatic biosynthesis of cholesterol contribute to the total serum cholesterol levels, LXR activation may be considered a fed-state phenomenon, although it is a consequence of long-term sufficiency rather than acute excess. LXR signaling alters energy storage by activating hepatic triglyceride synthesis and transport to peripheral tissues, while simultaneously activating reverse cholesterol transport to protect extrahepatic tissues against toxicity from excess dietary cholesterol [155]. In addition to the liver, LXRα is highly expressed in the intestine, kidney and adipose tissue [156], while LXRβ is expressed ubiquitously [157]. In humans, it has been reported that hepatic LXR expression increases with increasing severity of NAFLD [158]. Interestingly, however, the expression of some of the LXR target genes was only very modestly up-regulated, suggesting that the natural ligands were not present in sufficient quantities to activate the receptor. LXR has a dual role in NAFLD. While its activation promotes the development of obesity and steatosis, it may also suppress inflammation and improve hypercholesterolemia (Fig. 4, Table 1) [159]. There are attempts to develop LXR agonists that are not absorbed by the liver for the treatment of atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s diseases, and potentially an LXR antagonist could be used in the treatment of NASH.

Fig. 4.

LXR in NAFLD. Increased cholesterol in the post-prandial state is sensed by the brain which synthesizes oxysterols to provide feedback via liver X receptor (LXR) activation to up-regulate reverse cholesterol transport and inhibit inflammation to attenuate systemic cholesterol toxicity. In rodents but not humans, hepatic LXR activation increases bile acid synthesis as a compensatory mechanism for handling the liver’s increased cholesterol load. Hepatic LXR activation also facilitates fatty acid synthesis from dietary nutrients (via increased SREBP-C and FAS) and decreases hepatic FGF-21 production. In this way, excess dietary nutrients may be stored as fat. LXR is highly expressed in the liver (blue highlight).

5.2. LXR molecular function

Classically, LXR in its unliganded form is found in the nucleus bound to its response element. In this configuration LXR recruits co-repressors, silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) and nuclear receptor co-repressor 1 (NCoR1) [160], which recruit histone deacetylases (HDACs) making the gene less permissive for transcriptional activation. When ligand-bound, the receptor undergoes a conformation change that causes a loss of co-repressors and the gain of coactivators that in turn recruit histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and transcription machinery to induce gene expression. LXRs bind to an imperfect DR4 called an LXR response element [156]. The core of this element is identical to the sequences to which both CAR and PXR bind, and therefore considerable overlap in the sets of responsive genes between these receptors is expected [161–163].

The endogenous ligands for LXR are oxysterols. Oxysterols can be generated either non-enzymatically through a free radical-dependent reaction or enzymatically [164]. Free radical-dependent non-enzymatic oxysterols tend to be ring hydroxylations, often in the 7 position, while the best ligands for LXR are hydroxylated species in the side chain, most notably 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol, 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol, and 22(S)-hydroxycholesterol. These ligands are predominately enzymatically-generated and their concentration is thought to be physiologically relevant in tissues with high cholesterol metabolic rates and high LXR concentrations, such as liver or brain. In addition to the natural ligands for LXR, several synthetic ligands are also used to study LXR function. The two most commonly used are the LXRα and LXRβ dual agonist GW3965 and the selective LXRα agonist, T0901317. In addition to being an LXRα agonist, T0901317 is also a potent PXR agonist, therefore caution must be taken in assuming that responses to this agonist are purely LXRα-dependent [165]. Interestingly, the steatosis that forms when T0901317 is administered is worse than when GW3965 is administered, even though the expression of many of the LXR target genes is similar [166]. This suggests that PXR target gene activation is also important in the development of steatosis associated with prototypical LXR ligands. Recently, environmental chemicals including bisphenol A, phthalates, and organophosphates were found to interact directly with LXRα [167]. The potential role of environmental exposures to these and other industrial chemicals which activate LXR in human fatty liver disease warrants further study.

5.3. Role of LXR in hepatic steatosis and metabolism

LXR targets include genes involved in both cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism, and LXR activation worsens obesity [168] and steatosis while improving hypercholesterolemia. Activation of the LXR response element has been proposed to be a key molecular initiating event in steatosis AOP models [11,12]. The direct responsive genes include SREBP-1c, which is a proteolytically-activated transcription factor that is responsible for the transcriptional activation of a wide range of genes involved with triglyceride synthesis. The promoter of SREBP-1c contains two closely separated DR4 response elements [169]. SREBP-1c is also an insulin-inducible gene which is activated post transcriptionally by proteolytic cleavage allowing for tight regulation of targets such as ATP-citrate lyase, acetyl Co-A synthetase, fatty acid synthase, acetyl Co-A carboxylase and stearoyl-CoA desaturase. Thus, SREBP-1c is often considered to be a master regulator of lipid synthesis. Fatty acid synthase (FAS) is also a direct target of LXR signaling, having a DR4 LXR response element as its promoter [170]. FAS is a multi-subunit protein that catalyzes the formation of predominately palmitate from the carbohydrate-derived intermediates acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA and NADPH. It is the rate-limiting step in triglyceride synthesis. Other direct targets of LXR include acetyl-CoA carboxylase [171], while FGF21 is negatively regulated by LXR [172].

A second major regulatory category is reverse cholesterol metabolism. In this process, LXR induces expression of the ATP binding cassette transporters (ABC), ABCA1 [173] and ABCG1 [174], which causes cholesterol mobilization from the plasma membrane of non-hepatocyte cell types such as macrophages, and induces the formation of high density lipoprotein (HDL) or apolipoproteins such as apoA-1 and ApoE. This reduction in plasma membrane cholesterol reduces foam cell formation. Thus, LXR agonists have been proposed as potential therapies in the treatment of arthrosclerosis by enhancing reverse cholesterol transport; however the resulting hepatic steatosis has limited their full development. In mice, there is an LXR response element in the promoter of Cyp7a1 [175] and treatment with LXR agonists increases the synthesis of bile acids. The element is not present in the human CYP7A1 promoter. The consequence of this is observed to its full effect in LXR-knock out mice fed a high cholesterol diet which develop a cholesterol-laden steatosis [171]. Studies with LXR knockout mice demonstrate increased expression of SREBP-2 target genes [176]. SREBP-2 is a key regulator of cholesterol biosynthesis, targeting genes such as 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) synthase and reductase, farnesylpyrophosphate synthase, and squalene synthase. An important consideration, however, is that oxysterols directly affect SREBP-2 activity by inhibiting SREBP-2 proteolytic cleavage, and thus can also act in an LXR independent manner. The mechanism of LXR-dependent suppression of SREBP-2 activity is not well characterized and is likely to be highly dependent of cell type and cellular cholesterol status. LXR’s emerging role in carbohydrate metabolism has been recently reviewed [177]. LXR appears to improve diabetes by decreasing hepatic gluconeogenesis (via downregulation of PEPCK), increasing glucose-stimulated pancreatic insulin secretion, and by upregulating adipose glucose transporters including glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4).

5.4. Role of LXR in hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer

LXR tends to suppress inflammation. Several mechanisms have been suggested including the direct influence of SUMOylated LXR in inhibiting gene transcription from pro-inflammatory cytokine genes, namely TNFα, IL-6 and IL-1β [178]. In this model, ligand binding to LXR allows for SUMOylation and the SUMOylated receptor is capable of transrepression of NFκB by a tethering mechanism. Another potentially important anti-inflammatory mechanism involves the expression of the ABCA1 gene. The levels of cholesterol in the plasma membrane affect the function of Toll-like receptors such as TLR4, and higher levels of expression of ABCA1 reduces plasma membrane cholesterol and the ability to activate TLRs [179]. The net result is an inhibition of the downstream phosphorylation cascade and a reduction in the activation of effector targets including NFκB. Thus, both direct mechanisms of tethering and indirect mechanisms of action have been proposed as mechanisms in the inhibition of inflammation by LXR. An interesting recent observation is that some of the steatotic effects of LXR agonists are modulated in part by the Il-6 responsive gene product, C/EBP-β, and animals with a C/EBPβ deletion exhibit lower levels of steatosis in response to LXR agonists [180]. Therefore, LXR increases steatosis but decreases inflammation, and thus the progression of steatosis to steatohepatitis. Animal studies with the LXR antagonist, SR9238, suggest both anti-steatotic [181] and anti-fibrotic effects [182]. These studies show a dramatic decrease in steatosis, inflammation and collagen disposition. The inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine production is interesting as LXR agonists tend to have an anti-inflammatory role, and suggests that the ligand specificity for this process, presumably via SUMOylated-tethering mechanisms, may be different from the ligand specificity for direct binding and transactivation (meaning antagonists may function as agonists in this response). Relatively less is known about LXR and hepatocarcinogenesis. While some carcinogenic environmental chemicals activate LXR, they may simultaneously activate other class II nuclear receptors as well, making it difficult to determine the exact role of LXR in tumor development [183].

6. Farnesoid X receptor

6.1. FXR overview

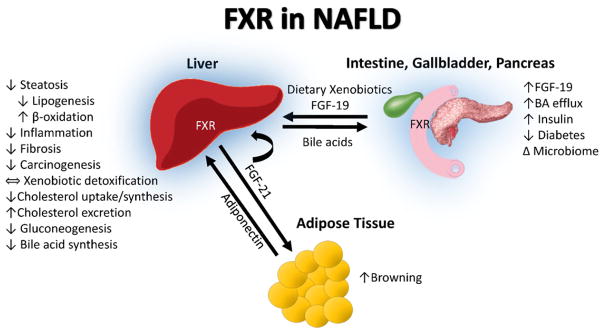

The farnesoid X receptor exists as two variants in humans, FXRα (NR1H4) and FXRβ (NR1H5), although the latter is a pseudogene [10, 184]. FXR was classically described to be the master regulator of bile acid synthesis. More recently, its role has been expanded to include regulation of the gut:liver axis in the fed state [10]. In addition to liver and intestine, FXR is abundantly expressed in adipose tissue, the adrenal glands, and kidney [185]. The role of FXR in lipid metabolism in the fed state has been elegantly described by Evans and Mangelsdorf in the “energy vector” hypothesis [10]. FXR activation creates the energy vector by inducing nutrient absorption in the intestine and by activating post-prandial hepatic energy metabolism. This effect is mediated, in part, by the production of FGF19 in the intestine through post-prandial bile acid activation of FXR. Importantly, hepatic FXR expression is decreased in NAFLD patients [186]. Activation of FXR by natural and synthetic ligands improves hepatic steatosis, inflammation and fibrogenesis in NAFLD involving several mechanisms including gut barrier integrity, hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism, and bile acid and cholesterol regulation (Fig. 5, Table 1). The recently published FLINT clinical trial demonstrated in NASH patients that therapy with the FXR agonist, 6-ethylchenodeoxycholic acid (OCA), for 72 weeks improved histological hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis vs. placebo [15]. However, cholesterol, pruritus, and HOMA-IR worsened. The benefits of FXR activation by synthetic ligands require further investigation, and a phase III clinical trial of OCA (REGENERATE) is underway. Organ-specific modulation of FXR activity is an emerging strategy to maintain clinical benefit while reducing side effects.

Fig. 5.

FXR in NAFLD. The farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is activated in the intestine by bile acids released from gallbladder in response to post-prandial event. The principle role of FXR in the intestine is to upregulate FGF-19, which travels via portal circulation to the liver where it binds FGFR4 to inhibit CYP7A1 activation and subsequently bile acid synthesis. Intestinal FXR activation leads to efflux of bile acids to circulation and elimination by renal excretion. Hepatic FXR activation plays a critical role in cholesterol, fatty acid, and glucose metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis, insulin resistance and carcinogenesis in NAFLD. Hepatic FXR activation also upregulates FGF-21 expression that acts as autocrine, paracrine and endocrine factors to regulate adipose browning and hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism. The blue highlight around the liver, intestine, gall bladder, and pancreas demonstrates tissues with high FXR expression.

6.2. FXR molecular function

Upon ligand activation, FXR binds transcriptional responsive elements as either monomers or heterodimers with RXR to bind an inverted repeat sequence [187]. Bile acids are believed to be the principal endogenous FXR ligands, although others, such as androsterone, exist. A recent study using a β-lactamase reporter gene assay identified new xenobiotic compounds interacting with FXR in the Tox21 10K compound collection including: anthracyclines, benximidazoles, dihydropyridines, pyrethroids, retinoic acids, and vinca alkaloids [188]. The pharmaceutical agonist, OCA, is a synthetic variant of the natural bile acid chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), and has approximately 100-fold higher potency than CDCA for activation of FXR. Other agonists such as GW4064 and XL335 have been used experimentally in animal models.

FXR serves as a sensor to regulate bile acid metabolism at the level of the enterohepatic axis. In the intestine, FXR is activated by bile acids in sensing the post-prandial events to facilitate lipid absorption [189]. Intestinal FXR activation induces intestinal epithelial expression of FGF19 (in rodents — FGF15), which is transported via portal circulation to the liver, where it binds fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 (FGFR4) and β-klotho and suppresses bile acid synthesis by inhibiting cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), the rate limiting enzyme of the bile acid synthesis [190–192]. In NAFLD, the hepatic response to FGF19 is impaired while the production of FGF19 in the intestine is not affected. This reduced response may result in further derangement of hepatic lipid metabolism in NAFLD. In the liver, activation of FXR also affects bile acid homeostasis by upregulating small heterodimer partner (SHP) that inhibits the expression of CYP7A1 [189]. The hepatokine, FGF21, is also a transcriptional target of hepatic FXR [193]. FGF21 potently regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism via increasing glucose uptake in adipose tissue and decreasing lipid synthesis and increasing fatty acid β-oxidation in the liver. A recent study also demonstrated that FGF21 exerted its beneficial effect in the liver through upregulation of the adipokine, adiponectin [194].

6.3. Role of FXR in hepatic steatosis and metabolism

Apart from its central role in bile acid metabolism, FXR activation regulates the expression of various genes crucial for lipid, glucose, and lipoprotein metabolism important in NAFLD [195–198]. In rodents, FXR is indispensable as a deficiency of FXR resulted in hepatic steatosis, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia and bile acid dysregulation [195–198]. These deleterious effects were reversed by genetic activation of FXR. In NAFLD patients, decreased hepatic expression of FXR was associated with increased expression of LXR and hepatic triglyceride synthesis [186]. FXR activation by OCA attenuated both steatosis and obesity in animal models [199] as well as in human subjects [15] with NAFLD. Hepatic FXR regulates lipid homeostasis by multiple mechanisms including decreased fatty acid synthesis, increased β-oxidation, and decreased fatty acid uptake. FXR activation also reduces lipogenesis by inhibiting SREBP-1 while upregulating PPARα and hepatic β-oxidation [197]. In mice fed a high fat and high cholesterol diet, treatment with the FXR agonist, GW4064, decreased hepatic steatosis by markedly reducing expression of hepatic lipid transporter CD36, and attenuated weight gain [200].

FXR regulates hepatic cholesterol metabolism, and hypercholesterolemia was observed with OCA treatment in the FLINT study [15]. FXR activation inhibits cholesterol uptake and conversion to bile acids, but also impacts cholesterol synthesis and excretion. In addition, FXR activation also promotes the expression of hepatic scavenger receptors leading to the enhanced reverse cholesterol transport. Not only was low density lipoprotein (LDL) increased by OCA in the FLINT study, but HDL was also decreased [15]. These data are supported by animal models demonstrating that GW4064 and XL335 also reduced HDL [201,202]. In contrast, FXR antagonism had a beneficial effect on hypercholesterolemia [203–205]. More data are required to better understand cholesterol metabolism in human subjects with NASH treated with selective FXR agonists and the potential role of statins to attenuate this adverse effect.

NAFLD is characterized by insulin resistance. Although controversy exists in the literature, the most rigorous study [206] indicates that FXR activation by OCA improved insulin sensitivity in human subjects with NASH. Likewise, OCA reversed insulin resistance in the Zucker fa/fa rat [199], while GW4064 suppressed hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia in mice fed high fat and high cholesterol diet [200]. In randomized, placebo-controlled studies in patients with NAFLD and type II diabetes, the safety and efficacy of OCA on insulin sensitivity were investigated [206]. Treatment with OCA significantly improved liver enzymes and insulin sensitivity compared to the placebo group using a 2-stage hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic clamp. However, in the subsequent FLINT study, OCA treatment was associated with worsened HOMA-IR [15]. These conflicting results could be due to differences between FXR activation in the fed and fasting states. However, in some studies, FXR activation has been shown to exacerbate weight gain and glucose intolerance [207,208].

In addition to insulin resistance, diabetes in NAFLD is also characterized by the dysregulation of gluconeogenesis and glyceroneogenesis. The regulation of gluconeogenesis and glyceroneogenesis through PEPCK by FXR activation has been proposed. FXR activation by CDCA increased PEPCK expression and glucose production in primary rat hepatocytes and in mice [209], while other investigators demonstrated that CDCA reduces PEPCK expression in mice and HepG2 cells [210].

Intestinal activation of FXR reduces diet-induced weight gain, hepatic glucose production and steatosis. Activation of FXR by a synthetic agonist, GW4064, strongly induces FGF19 expression in the intestine and further inhibits CYP7A1 gene expression leading to an inhibition of bile acid synthesis in the liver. Pharmacological administration of FGF19 increased the metabolic rate and reversed high fat-induced diabetes while decreasing adiposity [211,212]. Intestine-specific activation of FXR by fexaramine in mice reduced diet-induced weight gain, steatosis, and hepatic glucose production without activating FXR target genes in the liver [213]. This effect was believed to be mediated via FGF15 signaling. Thus, tissue-specific FXR activation may be a new approach to treating NAFLD.

6.4. Role of FXR in hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer

Intestinal FXR plays a crucial role in maintaining small intestine bacterial homeostasis and intestinal barrier function to protect against bacterial translocation [214,215] which should attenuate hepatic TLR activation and inflammation in NASH. Activation of FXR is dependent on bile acid species and the conjugation status of the individual bile acid [216]. Clinical studies demonstrate that patients with NASH have higher fasting and postprandial exposure to increased hydrophobic and cytotoxic secondary bile acid species [217]. Gut bacteria are involved in the biotransformation of bile acids through deconjugation, dihydroxylation and re-conjugation. Hepatic bile acid conjugation and microbiome-modulated bile acid dihydroxylation and deconjugation alter the bile acid species, thereby affecting postprandial bile acid-dependent FXR signaling in NAFLD/NASH. In turn, bile acids inhibit certain bacterial overgrowth.

The effects of FXR in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis have been demonstrated in mice lacking FXR and by activation with synthetic FXR agonists. FXR-null mice fed a high-fat diet had bacterial overgrowth with increased intestinal permeability [218] and higher levels of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic factors including: TNFα, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP), TGFβ and type 1 collagen [219]. FXR activation by GW4064 and CDCA promoted the expression of several genes that have antimicrobial properties and inhibited NFκB expression to reduce inflammatory cytokines in primary hepatocytes [214]. Activation of FXR by GW4064 improved hepatic inflammation and NASH induced by a high fat/high cholesterol diet [200]. Likewise, another synthetic FXR agonist, WAY-362450, attenuated MCD diet-induced hepatic inflammation, injury, fibrosis and NASH [206,220]. These studies suggest that FXR has a crucial role in controlling the intestinal microbiome, intestinal epithelial permeability, hepatic inflammation, and fibrogenesis.

Compelling evidence suggests that FXR may regulate hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development. FXR-null mice develop bile acid overload and spontaneous HCC by the age of 12–16 months [221–223]. A recent study [224] demonstrated that intestinal specific reactivation in FXR-null mice relieves these mice from bile acid overload and prevents HCC development via the intestinal FXR–FGF19 axis control of bile acid homeostasis. This finding is important because a potential therapeutic strategy could be targeting the intestinal specific FXR/FGF19 pathway to prevent HCC.

7. Nuclear receptor cross talk

This review article has highlighted the roles of PPAR, PXR, CAR, LXR, and FXR in controlling carbohydrate and lipid homeostasis within the gut:liver:adipose axis by regulating target gene expression in tissue-and nutrient-dependent manners. The focus on these nuclear receptors as potential drug targets for lipid dysregulation associated with NAFLD/NASH holds promise, yet a recognized challenge is defining potential side effects due to cross-talk between the pathways controlled by these nuclear receptors. All type II nuclear receptors heterodimerize with RXR and bind to DNA elements that share the same AGGTCA heptad repeat. This presents the potential for multiple nuclear receptor–RXR partners recognizing the same DNA motifs and for competition for RXR. This is particularly true in the liver where CAR, PPARα, LXR, PXR, and FXR are all expressed at high levels. It is well established that PXR and CAR bind the same DNA elements, and this can lead to drug–drug interactions [87]. Considering the “Energy Vector” hypothesis [10], it is important to pay attention to the cross-talk between the nuclear receptor signaling controlling metabolism in the fed (FXR, LXR, CAR and PXR) and fasting states (PPARα), recognizing that receptor function and crosstalk may vary with nutritional status. There is evidence that CAR directly activates a classic PPARα target gene, enoyl-CoA hydratase/3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, by binding a DR2 element within a complex PPAR responsive element [225]. Studies using LXR, CAR, and PXR knock-out mice revealed that LXR target gene expression is repressed by CAR, and CAR target gene expression is repressed by LXR [226]. The repressive effects of CAR on LXR action are predicted to be through competition for RXR binding. These studies indicate mechanisms by which cross talk may impact NAFLD. More data are needed on the role of nuclear receptor cross-talk in NASH.

8. Nuclear receptors in ASH, CASH, and TASH

This manuscript has focused on the role of nuclear receptors on NAFLD/NASH. However, nuclear receptors are also important in ASH, CASH, and TASH. PPAR [227], PXR [228], CAR [229], LXR [230], and FXR [231] are implicated in the pathogenesis or therapy of alcoholic liver disease. Nuclear receptor activation may also be involved in the steatohepatitis associated with atypical antipsychotic medications [232]. Interactions between environmental pollutants and nuclear receptors have been proposed to be initiating events in the development of steatosis [11,12], as well as a ‘second hit’ in the transition of steatosis to steatohepatitis [233]. Table 2 provides selected occupational and environmental chemicals which have been shown to interact with nuclear receptors. Several of these chemicals have previously been associated with fatty liver disease and TASH. These include metabolites of the solvents PCE and TCE [29]; the plasticizers DEHP [234] and bisphenol A (BPA) [235]; and the persistent organic pollutants PCBs [233], perfluorooctanoic acid [236], and some organochlorine insecticides [237]. Polymorphisms in nuclear receptors including PXR [70] and PPAR [238] have previously been associated with fatty liver disease. Interactions between genes and environmental chemicals are likely to impact steatohepatitis, but more data are needed.

Table 2.

Selected occupational and environmental chemicals which interact with nuclear receptors.

| Nuclear receptor | Selected environmental chemicals interacting with nuclear receptors |

|---|---|

| PPARα | Dichloroactic acid (solvent metabolite), diclofap-methyl (herbicide), diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), imazalil (fungicide), pyrethroid insecticides, trichloroacetic acid (solvent metabolite) [26–29] |

| PPARγ | Bisphenol A (BPA), tributyltin [33] |

| PXR | BPA, chloroacetanilide herbicides, DEHP, organochlorine insecticides, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), pyrethroid insecticides [251] |

| CAR | BPA, chloroacetanilide herbicides, DEHP, organochlorine insecticides, perfluorooctanoic acid, pyrethroid insecticides, PCBs [251] |

| LXRα | BPA, phthalates, organophosphate insecticides [167] |

| FXR | pyrethroid insecticides [188] |

Abbreviations: BPA, bisphenol A; CAR, constitutive androstane receptor (NR1I3); DEHP, diethylhexyl phthalate, FXRα, farnesoid X receptor α (NR1H4); LXRα, liver X receptor α (NR1H2); PCBs, polychlorinated biphenyls; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (NR1C1); PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (NR1C3); PXR, pregnane X receptor (NR1I2).

9. Conclusions

Nuclear receptor dysregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of NAFLD by impacting the integrated control of energy metabolism by the gut:liver:adipose axis. Environmental chemicals may compound the problem by directly interacting with nuclear receptors leading to metabolic confusion and the inability to differentiate fed from fasting conditions. The impact of PPAR, PXR, CAR, LXR, and FXR on selected NAFLD features and mechanisms are given in Table 1. Obesity is increased by activation of PPARγ, PXR, and LXR, but is decreased by the other receptors. Activation of FXR, PXR, or PPARγ decreases intestinal permeability, a key pathogenic mechanism in NAFLD. The impact of nuclear receptors on diabetes is complex as insulin resistance, gluconeogenesis, and pancreatic insulin production may all be affected, sometimes in discordant ways. While steatosis is increased by activation of LXR and PXR, it is decreased by PPAR, FXR and CAR. Interestingly, hepatic inflammation is down-regulated by activation of any of these receptors. This could potentially be a protective mechanism to attenuate TLR4 activation by dietary or adipose-derived fatty acids mimicking lipopolysaccharide. While FXR appears to be antifibrotic, more data are needed on the role of the other receptors in fibrosis in human NASH. Clinical trials including the PIVENS and FLINT studies demonstrate that nuclear receptor targeted therapies may lead to the paradoxical dissociation of steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and obesity in NASH. Novel strategies may be required to provide the beneficial effects of nuclear receptor activation while minimizing adverse metabolic effects. Such strategies currently under development include dual receptor agonists, tissue-specific agonists/antagonists, and administration of FGF21. The impact of nuclear receptor crosstalk in NAFLD is likely to be profound, but requires further elucidation.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [1R01ES021375, 1R13ES024661, F30ES025099, 5T35ES14559], the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [K23AA18399, R21AA022416, R01AA023190, 1U01AA021901, 1R01AA023681] and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry [200-2013-M-57311].

Abbreviations

- 5-HETE

5-hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- ACOX1

acyl-CoA oxidase 1

- AFB1

aflatoxin B1

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- AOP

adverse outcomes pathway

- AP1

activator protein 1

- ASH

alcoholic steatohepatitis

- BPA

bisphenol A

- CAR

constitutive androstane receptor

- CASH

chemotherapy associated steatohepatitis

- C/EBP

CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein

- CCRP

cytoplasmic CAR retention protein

- CD36

fatty acid translocase

- CDCA

chenodeoxycholic acid

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase 2

- CPT1

carnitine palmitoyltransferase I

- CYP3A4

cytochrome p450 oxidase 3A4

- CYP7A1

cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase

- DDE

dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene

- DEHP

diethylhexyl phalate

- DR

direct repeat

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- ER

everted repeat

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FAS

fatty acid synthase

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FGFR4

fibroblast growth factor receptor 4

- FOXO1

forkhead box protein O1

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- GADD45β

growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible beta

- GLUT4

glucose transporter type 4

- GRIP1/TIF2

glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein-1/transcriptional intermediary factor 2

- HATs

histone acetyltransferases

- HBx

hepatitis B viral protein X

- HDACs

histone deacetylases

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA

- HOMA-IR

homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- IκBα

NFκB inhibitor alpha

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IL-1β

interleukin-1beta

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- IL-1RA

interleukin-1 receptor antagonist

- INSIG1

insulin-induced gene 1 protein

- IR

inverted repeat

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- LDLR

low density lipoprotein receptor

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LXR

liver X receptor

- MCD

methionine–choline deficient diet

- MDR1

multidrug resistance protein 1

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NCOR1

nuclear receptor co-repressor, 1

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- OCA

obeticholic acid

- PBREM

phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module

- PCB

polychlorinated biphenyl

- PCE

perchloroethylene

- PCN

pregnenolone 16 α-carbonitrile

- PDK4

pyruvate dehydrogenase lipoamide kinase isozyme 4, mitochondrial

- PEPCK

phosphoenol pyruvate carboxylase

- PGC-1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha

- PGJ2

prostaglandin J2 (5Z,13E,15S)-15-Hydroxy-11-oxoprosta-5,9,13-trien-1-oic acid)

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PP

peroxisome proliferation

- PPA2

protein phosphatase 2

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- ROR

retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- SCD1

stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1

- SIRT1

sirtuin 1

- SLC13A5

solute carrier 13A5

- SMRT

silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor

- STAT

signal transducers and activators of transcription

- SRC-1

steroid receptor coactivator 1

- SREBP

sterol regulatory element binding protein

- SULT

sulfotransferase

- SXR

steroid and xenobiotic sensing nuclear receptor

- TAFLD

toxicant associated fatty liver disease

- TASH

toxicant associated steatohepatitis

- TCE

trichloroethylene

- TGFβ1

transforming growth factor beta1

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TR

thyroid hormone receptor