Abstract

The expression of many genes of facultatively photosynthetic bacteria of the genus Rhodobacter is controlled by the oxygen tension. Among these are the genes of the puf and puc operons, which encode proteins of the photosynthetic apparatus. Previous results revealed that thioredoxins are involved in the regulated expression of these operons, but it remained unsolved as to the mechanisms by which thioredoxins affect puf and puc expression. Here we show that reduced TrxA of Rhodobacter capsulatus and Rhodobacter sphaeroides and oxidized TrxC of R.capsulatus interact with DNA gyrase and alter its DNA supercoiling activity. While TrxA enhances supercoiling, TrxC exerts a negative effect on this activity. Furthermore, inhibition of gyrase activity strongly reduces puf and puc expression. Our results reveal a new signaling pathway by which oxygen can affect the expression of bacterial genes.

INTRODUCTION

Thioredoxins, ubiquitous small proteins (∼12 kDa) containing an extremely reactive dithiol-disulfide in their active center, are implicated in many cellular processes. Originally discovered as electron donors for ribonucleotide reductase in Escherichia coli (1), thioredoxins were later identified as key players in keeping intracellular protein disulfides generally reduced (2). Their role in defense against oxidative stress is well established for E.coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (3). Thioredoxins are known as a subunit of T7 DNA polymerase; they are involved in phage assembly, in the light-dependent regulation of chloroplast photosynthetic enzymes and in the regulation of apoptosis (4). In mammals, thioredoxins are also implicated in a redox regulation of transcription factors such as NF-κB or AP-1 (5).

The thiol-reducing activities of thioredoxins and glutaredoxins have been best characterized in E.coli, which has two genes encoding soluble thioredoxins (trxA and trxC) and three genes encoding glutaredoxins (grxA, grxB and grxC). A trxAtrxC mutant of E.coli is viable, suggesting that the glutaredoxin system can functionally replace the thioredoxin system (6). Thioredoxin is, however, essential in other organisms such as Anacystis nidulans (7), Synechocystis sp. PC6803 (8) and Rhodobacter sphaeroides (9).

More recently, thioredoxin was also shown to be involved in the oxygen-dependent regulation of photosynthesis genes in R.sphaeroides and Rhodobacter capsulatus (10,11). Members of the genus Rhodobacter are facultatively photosynthetic bacteria that synthesize photosynthetic complexes only if the oxygen tension in the environment is low. Oxygen affects expression of photosynthesis genes at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. The genes for pigment binding proteins are organized in two polycistronic operons. The puf operon encodes the pigment binding proteins of the light harvesting (LH) I complex and of the reaction center. The puc operon encodes proteins of the LHII complex. Many proteins are involved in oxygen-dependent transcription of these operons (12,13). The two-component system PrrB/PrrA has a central role in this regulation in R.sphaeroides, and its counterpart RegB/RegA in the close relative R.capsulatus was also shown to be involved in oxygen-dependent regulation of genes for nitrogen fixation, CO2 fixation, hydrogenase synthesis (14), enzymes of the respiratory chain (15) and dimethylsulfoxide reductase (16). The sensor kinase RegB autophosphorylates in a redox-dependent manner (17,18). A highly conserved cysteine, which forms an intermolecular disulfide bond in oxidizing condition, converts the active RegB kinase to an inactive tetramer (19). RegA is phosphorylated by RegB and activates transcription under low oxygen tension after binding to the puf and puc promoter regions (20). Under high oxygen tension PpsR (CrtJ in R.capsulatus) binds to the puf and puc promoter regions and represses transcription. The activity of PpsR is regulated by the AppA protein, which not only transmits a redox signal but also functions as a blue light receptor (21–23).

R.capsulatus, like E.coli, harbors genes for thioredoxin 1 (trxA) and 2 (trxC), while R.sphaeroides lacks the trxC gene. An R.sphaeroides mutant strain which contains lower amounts of TrxA than the wild type shows lower puf and puc transcription after a transition from high to low oxygen tension (10). An R.capsulatus strain lacking the trxC gene shows elevated transcription of the puf and puc genes under the same conditions when compared to its parental wild-type strain (11). In order to elucidate the signaling pathway leading from thioredoxin to transcription of photosynthesis genes, we used the yeast two-hybrid system to search for proteins that interact with thioredoxin and are likely to be involved in oxygen-dependent regulation of photosynthesis genes. While we were unable to detect an interaction of thioredoxin to PrrA, PpsR or AppA, our results suggest an interaction to a number of other proteins, one of which is the DNA gyrase B subunit (GyrB). The bacterial type IIA enzyme DNA gyrase is the only topoisomerase capable of introducing negative supercoils into DNA. Structurally, gyrase acts as an A2B2 tetramer, encoded by the gyrA and gyrB genes, respectively (24). An earlier study suggested that DNA gyrase activity affects the expression of puf and puc genes in R.capsulatus (25). Here we show that trx mutants of R.sphaeroides and R.capsulatus show altered gyrase activity, and that oxidized TrxC and reduced TrxA can bind to gyrase thereby affecting its supercoiling activity in an opposite way. Based on these data, we present a new model for the influence of thioredoxins on gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids and growth conditions

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E.coli cultures were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C, while R.sphaeroides and R.capsulatus were grown at 32°C in a malate minimal salt medium (26). The cells were grown aerobically by incubating 100 ml of culture in 500 ml baffled flasks under vigorous shaking. The oxygen partial pressure was determined to be 20% by using a Pt/Ag oxygen electrode (Bachofer). For semiaerobic growth conditions 40 ml of culture were incubated in 50 ml flasks (oxygen partial pressure of 1–2%). For oxygen shift experiments, cells were grown aerobically to an OD660 of 0.4–0.5 and then transferred to the 50 ml flasks or vice versa. Cells were grown in screw-cap flasks filled to the top for anaerobic phototrophic growth in the light (45 W m−2). Incubation was in the dark for aerobic and semiaerobic growth.

Table 1. Bacterial strains and plasmids.

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E.coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi (lac-proAB) F′[traD36 proAB+ lacIqlacZ M15] | Stratagene |

| SM10 | RecA thi thr leu; chromosomal RP4-2 (Tc::Mu) | (30) |

| M15 (pREP4) | Host strain for protein overexpression | Qiagen |

| BL21 | Host strain for GST-fusion protein overexpression | Amersham |

| Aegis256 | wp551nadB::Tn10 | (65) |

| Aegis257 | wp551trxCnabB::Tn10 | (65) |

| Aegis262 | wp551trxAnabB::Tn10 | (65) |

| R.capsulatus | ||

| SB1003 | Wild type | (66) |

| SB1003trxC− | SB1003 ΔtrxC::Kmr | (11) |

| SB1003trxA | SB1003 ΔtrxA Tcr (lac-protrxA) | This study |

| R.sphaeroides | ||

| WS8 | Wild type | (67) |

| TK1 | WS8 trxA::Kmr(pRKSMTX1) | (10) |

| S.cerevisiae | ||

| AH109 | MATa trp1-901 leu2-3,112,ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ LYS2::GALUAS-GAL1TATA-HIS3 MEL1 GAL2UAS-GAL2TATA-ADE2 URA3::MEL1UAS-MEL1TATA-lacZ | Clontech |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript SK(+) | Cloning plasmid | Stratagene |

| pGBKT7 | GAL4(1-147) DNA-BD TRP1 kanr c-Myc epitope tag | Clontech |

| pGADT7 | GAL4(768-881) AD LEU2 ampr HA epitope tag | Clontech |

| pGBKT7-RctrxA | pGBKT7 containing trxA gene of R.capsulatus | This study |

| pGBKT7-RctrxC | pGBKT7 containing trxC gene of R.capsulatus | This study |

| pGBKT7-53 | Murine p53(72-390) in pGBKT7 TRP1 kanr control vector | Clontech |

| pGADT7-T | SV40 large T-antigen(84-708) in pGADT7 LEU2 ampr control vector | Clontech; this study |

| pGBKT7-Lam | Human lam C(66-230) in pGBKT7 TRP1 kanr control vector | Clontech |

| pVA3-1 | Murine p53(72-390) in pAS2-1 TRP1 ampr control vector | Clontech |

| pTD1-1 | SV40 large T-antigen(84-708) in pACT2 LEU2 ampr control vector | Clontech; this study |

| pLAM5′-1 | Human lam C(66-230) in pAS2-1 TRP1 ampr | Clontech |

| pAS2-1 | GAL4(1-147) DNA-BD TRP1 ampr CYHs2 | Clontech |

| pACT2 | GAL4(768-881) AD LEU2 ampr HA epitope tag | Clontech |

| pAS-RstrxA | pAS2-1 containing trxA gene of R.sphaeroides | This study |

| pGEX-4T-1 | GST-fusion expression vector | Amersham |

| pGEX-RcGyrB | 2.5 kb gyrB gene cloned into pGEX-4T-1 | This study |

| pUTC51 | 1.9 kb PstI fragment containing trxA gene of R.sphaeroides under the control of ptrc promoter and lacIq | (27) |

| pQERctrxC | pQE32 with insert thioredoxin C coding region | (11) |

| pPHU281 | Tcr, lacZ′, mob(RP4) | (68) |

| pPHURcuptrxA | DNA fragment containing the first 144 bp of the R.capsulatus trxA gene cloned into pPHU281 | This study |

| pGADT7clone29 | 388 bp of gyrB, ranging from amino acid 69–198, of R.capsulatus in pGADT7 | This study |

| pGADT7clone 280 | 136 bp of gyrB, ranging from amino acid 342–387, of R.sphaeroides in pGADT7 | This study |

| pGADT7gyr392 | 392 bp of gyrB, ranging from amino acid 290–420th, of R.capsulatus in pGADT7 | This study |

Yeast two-hybrid screening

Thioredoxin A and/or C of R.capsulatus and R.sphaeroides were cloned into pAS2-1 or pGBKT7, and the constructs were introduced into yeast strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109 as described in MATCHMAKER Two-Hybrid System 2 or 3. Retransformation was carried out with R.capsulatus and R.sphaeroides genomic libraries into strain AH109, which already contained the pAS-RstrxA or pGBKT7-RcTrxA/C plasmid. The libraries were constructed from chromosomal DNA partially digested by Sau3A I and ligated into BamHI-digested pACT2 or pGADT7. The transformants were plated onto synthetic complete medium without adenine, tryptophan, leucine and histidine, but containing 6 mM amino-triazole. After incubation for 5 days, colony lift-filter assays to determine β-galactosidase activity were performed on each plate, as described in the yeast protocols handbook (Clontech). For each positive colony, the library plasmid was isolated. Confirmation of positive interactions (secondary screening) was performed by cotransforming the library plasmid and pAS-RstrxA or pGBKT7-RcTrxA/C into strain AH109. Cotransformants which can grow on selective medium were chosen and β-galactosidase activity was measured. Library clones that tested positive were sequenced.

Mutant construction

In order to generate a trxA mutant of R.capsulatus, a DNA fragment containing the full-length trxA gene was amplified by PCR with primers: 5′-GAGAATCCCATGGCTACCGTCG-3′ and 5′-GGTAAGCTTGCCCTCCGTTTGC-3′ from genomic DNA. The PCR product (447 bp) was cloned into plasmid pUTC5 (27), replacing 421 bp of the trxA gene of R.sphaeroides. Then a 1.7 kb DNA fragment containing the first 144 bp of the trxA gene of R.capsulatus, the hybrid ptrc promoter (28) and the lacIQ element was removed from the resulting plasmid by PstI and SacI and cloned into pPHU281 (29) to generate plasmid pPHURcuptrxA (Table 1), followed by transformation into the E.coli strain SM10 (30). This plasmid was conjugated diparentally into SB1003. Candidates for single crossover recombination events were first screened for tetracycline resistance which is carried by plasmid pPHURcuptrxA. The resulting mutant has one intact trxA gene but under the control of the trc promoter. The ptrc promoter is constitutively expressed in Rhodobacter, independently of oxygen tension (10). The native trxA gene was partially deleted and inactivated in the mutant. The correct insertion was confirmed by Southern blot analysis and PCR.

Southern and northern hybridization analysis

Total RNA and genomic DNA were isolated from wild-type R.capsulatus SB1003 and trxA and trxC mutants. Southern and northern blot analyses were performed as described previously (11). To ensure that equal quantities of RNA were present in each lane of the northern blot, the membrane was stripped and reprobed with an oligo 5′-CTTAGATGTTTCAGTTCCC-3′, corresponding to the 23S rDNA positions 187–205 (E.coli numbering) of Rhodobacter as a control. Each northern analysis was performed at least 3 to 4 times.

RT–PCR

For RT–PCR analysis the RT reaction was carried out in a final volume of 25 μl containing 30 pmol of reverse primer, 2 μg of total RNA, 1 mM each of the four deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates and 1.5 U of reverse transcriptase (Promega) at 42°C for 1 h, and 99°C for 2 min to inactivate the reverse transcriptase. PCR was carried out in a final volume of 50 μl containing 5 μl of reverse transcription reaction product, 1 U of Taq polymerase (Qiagen) and 2 pmol each of the oligonucleotide primers 5′-CGGCTGTCGCAATTCACCAC-3′ and 5′-GATGAATTCGCGCCGCGGTT-3′ for gyrB. Amplification was carried out by an initial denaturation step at 96°C for 3 min followed by 28 cycles of 96°C for 1 min, 62°C for 40 s and 72°C for 30 s. A sample lacking reverse transcriptase was included for each reaction as a control for DNA contamination. Reaction products were subjected to 10% PAGE.

Bacteriochlorophyll measurements

An aliquot of 0.5 ml of culture was sedimented at 10 000 g and resuspended in 0.5 ml of acetone–methanol (7:2, v/v). The absorbance of the supernatant at 770 nm was determined after spinning in a microcentrifuge at ≥ 10 000 g for 3 min. The relative bacteriochlorophyll content of the cells is given as the absorbance at 770 nm divided by the optical density at 660 nm.

Enzyme assays

Supercoiling assays were carried out as described previously (31,32). Plasmid pBluescript SK (+) (Stratagene) was used as the substrate. Novobiocin or ciprofloxacin (Sigma) was added at a final concentration of 75 nM (50 ng/ml) or 0.3 mM (100 μg/ml), respectively. The reaction was trapped by adding 0.2% SDS and the reaction mixtures were resolved on 0.8% agarose gels in 40 mM Tris-acetate buffer containing 1 mM EDTA. For in vitro assays, purified gyrase (John Innes Enterprise Ltd) and purified E.coli thioredoxin 1 (Promega) were used. The gel was then run overnight.

In vitro GST pulldown assay

A DNA fragment carrying the complete gyrB gene of R.capsulatus was amplified by PCR with the primers 5′-CGGGATCCATGACCGAAACCCCGAAGAACAA-3′ and 5′-CGCTCGAGTCAGAAATCGAGGTTTTCCACGC-3′, and cloned into the BamHI site of pGEX-4T-1 to generate pGEX-RcGyrB, followed by transformation into E.coli strain BL21 (Amersham). Glutathione S-transferase (GST) or GST fusion proteins were purified with glutathione-conjugated agarose beads (Pharmacia) from BL21 following the manufacturer's instruction (Amersham). (His)6-tagged thioredoxin 2 of R.capsulatus was purified from E.coli M15(pREP4) as described in (11). In order to detect the interaction of GyrB with TrxA, anaerobic and aerobic cell extracts of wild-type SB1003 were prepared. An aliquot of 30 ml of fresh overnight culture were harvested and resuspended in sonication buffer I (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM DTT, 20 mM KCl, 1.5 mM ATP, 5 mM spermidine, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 μg/ml BSA). After sonication with a Bandelin SONOPULS GM 70 at a 50% duty cycle on ice for 40 s 4 times with 30 s interval break, crude cell extracts were obtained by centrifugation at 12 000 g for 15 min to remove cell debris. An aliquot of 20 μg of total proteins determined with Bradford was additionally treated with 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol or 1 mM H2O2 to reduce or oxidize TrxA, which was then added to the GST–GyrB protein. GST pulldown assays were performed as described (Amersham) for TrxC–GyrB interaction using His-tagged TrxC, for TrxA–GyrB interaction, using cell extracts. Samples were separated on reducing SDS–15% polyacrylamide gels (SDS–PAGE), followed by immunological analysis.

Immunological analysis

Samples were electrophoresed in SDS–15% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon™-P membrane (Millipore). Western blotting was performed according to the Western Exposure Chemiluminescent Detection system (Clontech). Thioredoxin antibodies (11) were used to detect GST fusion protein-associated TrxC. A monoclonal N-terminal antibody of GyrB (John Innes Enterprises Ltd) was used to detect the GyrB level in the cells.

Thiol-redox state analysis

Oxidized and/or reduced cell extracts (20 μg total protein) or TrxC protein (50 μM) were incubated at 34°C for 2 h in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.1% SDS and 15 mM 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstibene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (AMS) (Molecular Probes). The mixtures were then separated by 15% non-reducing SDS–PAGE, and TrxA or TrxC were detected by immunological analysis.

Redox states of TrxA in vivo were detected as described previously (23). Briefly, whole-cell proteins of the strain SB1003 were precipitated by direct treatment with trichloroacetic acid to give a final concentration of 10%. Protein precipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed with 500 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), and dissolved in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1% SDS and 15 mM AMS. After incubation at 34°C for >3 h, the mixture was subject to 15% SDS–PAGE and western analysis.

RESULTS

Use of the yeast two-hybrid system to identify putative interaction partners of thioredoxin

Since mutants of Rhodobacter that lack the central oxygen-responsive two-component system PrrB/PrrA (RegB/RegA) still show some residual oxygen-dependent expression of photosynthesis genes (33), we were looking for other oxygen sensors in this genus. As reported previously, trx mutant strains of R.sphaeroides or R.capsulatus show altered oxygen-dependent transcription of the puf and puc operons (10,11). Since thioredoxin is not known as a DNA binding protein, we assumed that it would act on gene transcription indirectly by affecting the DNA binding affinity or the activity of a transcription factor. Therefore, we tested the interaction of TrxA from R.sphaeroides, and TrxA or TrxC from R.capsulatus, respectively, with such candidate proteins by applying the yeast two-hybrid system. We did not detect interaction of any of the Rhodobacter thioredoxins to the R.capsulatus CrtJ protein or the R.sphaeroides PpsR (CrtJ homolog) or AppA protein. All these proteins are known to be involved in the redox regulation of the photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter (34).

We also screened libraries of the R.sphaeroides and R.capsulatus chromosome for putative interaction partners of thioredoxin by using the yeast two-hybrid system in order to unravel the pathway of signaling from thioredoxin to puf and puc transcription. Considering the numerous functions of thioredoxin, we were not surprised to isolate a number of different positive clones from this screening. One positive clone from the screen with the R.sphaeroides library was identified to carry a DNA fragment encoding part of the biotin carboxylase. Biotin carboxylase is a subunit of acetyl CoA carboxylase which is known to be affected by thioredoxin (35). Additional proteins or protein domains identified as thioredoxin targets by our two-hybrid screen and also by proteomic-based screens (36,37) are arginosuccinate synthase, malonyl CoA acyl carrier protein transacetylase, translational elongation factor Tu and sugar epimerase. These results confirmed that the yeast two-hybrid screen is a suitable system to find interaction partners for a bacterial thioredoxin.

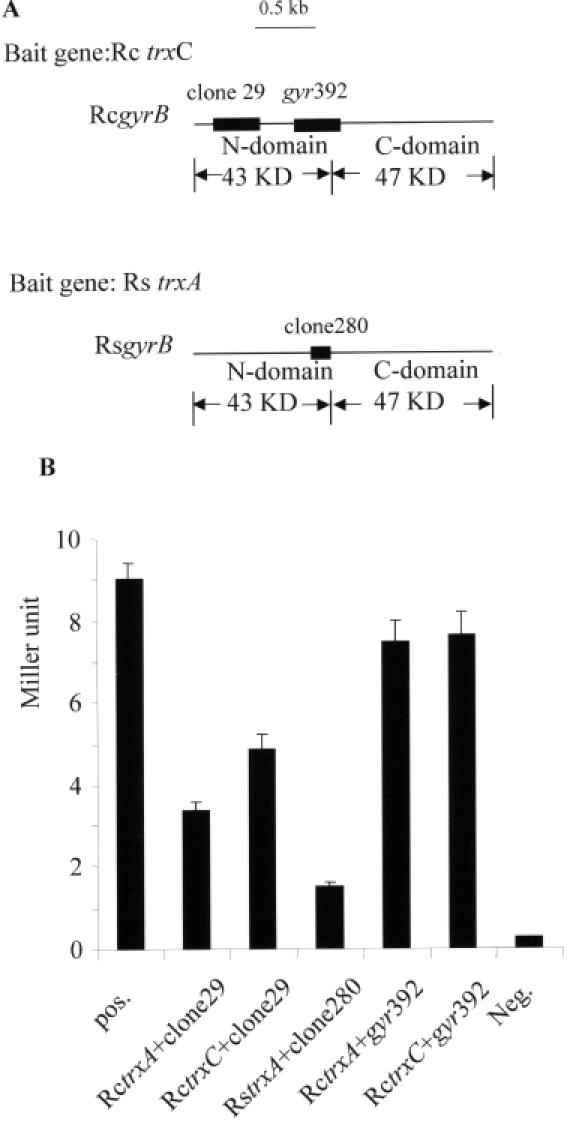

Our further interest focused on a protein that was identified as a putative interaction partner for TrxA of R.sphaeroides and the R.sphaeroides genomic library as well as for TrxC of R.capsulatus and the R.capsulatus genomic library, the DNA gyrase B subunit (GyrB). An influence of thioredoxin on gyrase activity is an attractive model to explain the effect of thioredoxin on the expression of photosynthesis genes. The plasmid isolated from the R.sphaeroides genomic library harbored a 136 nt DNA fragment (clone 280) encoding the amino acid residues 342–387 of GyrB. The plasmid isolated from the R.capsulatus genomic library contained a 388 nt DNA fragment (clone 29) encoding the amino acid residues 69–198 of GyrB (Figure 1A). This part of GyrB is also known to bind the gyrase inhibitor novobiocin (38). Yeast strains expressing only TrxA or TrxC from Rhodobacter or harboring only one of the gyrB plasmids were unable to grow on selective agar.

Figure 1.

Interaction of Trx and gyrase B subunit (GyrB) revealed by the yeast-two-hybrid system. (A) Screening results for the interaction of Trx with the GyrB. Clone 280 was screened out from the library of R.sphaeroides with trxA (Rs trxA) as a bait gene. Clone 29 was screened out from the library of R.capsulatus with trxC (Rc trxC) as a bait gene. The position and the coverage are marked by black bars within the gyrB gene. RcgyrB: gyrB of R.capsulatus; RsgyrB: gyrB of R.sphaeroides. (B) Quantification of the β-galactosidase activity. The activity was measured in yeast strain AH109 with the cotransformed plasmids containing the binding domain of GAL4 plus the cloned trx gene and the activation domain of GAL4 plus the part of gyrB gene. pos.: Positive control with pGADT7-7 and pGBKT7-53. RctrxA, RctrxC: trxA and trxC genes from R.capsulatus. RstrxA: trxA gene from R.sphaeroides. gyr392: cognate of clone 280 in R.capsulatus. Neg.: negative control with pGADT7 and pGBKT7-Lam.

When the β-galactosidase assay was used to quantify the interaction of the different Trx proteins to gyrase B, the strongest interaction was found for TrxC from R.capsulatus (Figure 1B). The interaction of TrxA from R.capsulatus with the peptide of its cognate gyrase was considerably weaker, but still stronger than the interaction between TrxA from R.sphaeroides and the peptide of its cognate GyrB (Figure 1B). Plasmid pGADT7gyr392 carries a 392 nt DNA fragment of the R.capsulatus gyrB gene. This fragment contains the DNA sequence homologous to the fragment present in clone 280, which was isolated from the R.sphaeroides genomic library. When pGADT7gyr392 was cotransformed into yeast strain AH109 with plasmid pGBKT7-TrxA or pGBKT7-TrxC, a strong interaction was observed (Figure 1B), indicating that the N-terminal domain of GyrB interacts with both thioredoxins, TrxA and TrxC, in R.capsulatus.

Confirmation of interaction between thioredoxin and gyrase

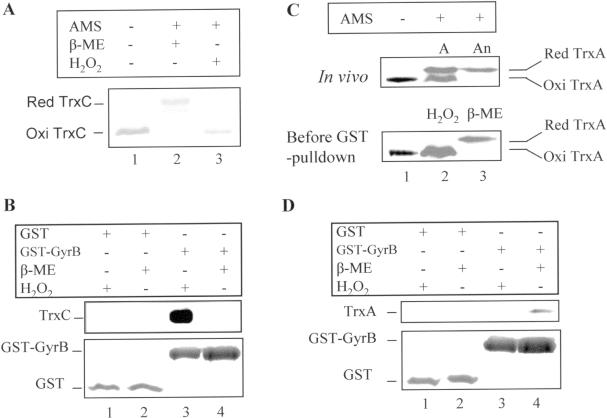

In order to confirm an interaction of thioredoxin with gyrase as suggested by the yeast two-hybrid system, protein affinity pulldown assays were performed using recombinant GST-tagged gyrase B from R.capsulatus. Since the function of thioredoxins can depend on the redox state, we monitored disulfide bond formation by covalent modification of Cys sulfhydryl groups with AMS. This modification results in retardation of the electrophoretic mobility of the proteins. The formation of a disulfide bond between the two active site cysteines of thioredoxin renders the protein resistant to AMS modification. As shown in Figure 2A (lane 2) and Figure 2C (lane 2 and 3, upper panel), treatment of reduced TrxA or TrxC with AMS resulted in slower electrophoretic migration than migration of AMS-treated oxidized TrxA (Figure 2C, lane 2, upper panel) or TrxC (Figure 2A, lane 3). There is no difference in the electrophoretic migration pattern between oxidized TrxC that was treated with AMS from that of untreated oxidized TrxC (Figure 2A, lanes 1 and 3, respectively) confirming that oxidized TrxA and TrxC have no available Cys for AMS modification.

Figure 2.

GST pulldown showing the interaction of oxidized TrxC (A and B) and reduced TrxA (C and D) with GyrB of R.capsulatus in vitro. Anaerobically (An) and aerobically (A) grown cell extracts, His-tagged TrxC protein and GST–GyrB fusion protein were prepared as described (see Materials and Methods). TrxA in cell extracts (total protein 20 μg, determined with Bradford) and His-tagged TrxC (50 μM) were reduced with 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), or oxidized with 1 mM H2O2 in 10 μl at room temperature for 30 min, then subjected to thiol-trapping by AMS (Molecular Probes) or GST pulldown. (A) Examination of disulfide bond formation of His-tagged TrxC after β-ME or H2O2 treatment by AMS modification. (B) GST pulldown to detect the interaction of GyrB with TrxC. The upper panel shows the immunological detection of TrxC; the bottom panel shows silver-stained GST and GST–GyrB proteins. (C) Examination of disulfide bond formation of TrxA in anaerobic low-light (100 mmol m−2 s−1) and aerobic dark grown cells in vivo (upper panel) and after β-ME or H2O2 treatment (lower panel) by AMS modification. (D) GST pulldown to detect the interaction of GyrB with TrxA. The upper panel shows the immunological detection of TrxA, the bottom panel, silver stained GST and GST–GyrB proteins.

When protein affinity pulldown assays were performed using recombinant GST-tagged GyrB and (His)6-tagged R.capsulatus TrxC, only oxidized TrxC showed binding (Figure 2B, lane 3, upper panel). We could not see any binding using recombinant (His)6-tagged TrxA of both Rhodobacter species to gyrase. It is conceivable that the (His)6-tag at the N-terminus of TrxA changes its local conformation. However, when we used cell extracts for the pulldown assay, native reduced TrxA of R.capsulatus showed interaction to GyrB (Figure 2D, lane 4, upper panel), as well as TrxA of R.sphaeroides (data not shown). TrxC or TrxA did not bind to the GST–sepharose (Figure 2B and D, both lanes 1 and 2, upper panel).

Generation and characterization of a trxA mutant strain from R.capsulatus

The results from the yeast two-hybrid screen and the GST pulldown demonstrate an interaction of Rhodobacter TrxA and TrxC with GyrB. If the effect of thioredoxin on the transcription of photosynthesis genes is indeed mediated by gyrase, trx mutant strains should show altered gyrase activity. To directly compare the effect of TrxA and TrxC on gyrase activity and expression of photosynthesis genes, it was necessary to generate mutants from the identical parental strain. The trxA gene of R.capsulatus could not be inactivated completely (data not shown), suggesting that it is essential as observed for R.sphaeroides (9). The trxA mutant of R.capsulatus was generated by single crossover through recombination of part of the trxA gene with one intact copy of trxA. In the final strain, the trxA gene is under the control of the trc promoter on the chromosome. Using antibodies directed against R.capsulatus TrxA, we detected very low levels of the protein in the mutant strain, independent of growth conditions (data not shown). No significant difference of the doubling times was observed under high oxygen tension (2 h ± 10 min doubling time for wild type and trxA mutant) and low oxygen tension (3 h ± 10 min for wild type, 3 h 27 min ± 10 min for trxA mutant), while a severe growth deficiency of the trxA mutant is observed under anaerobic phototrophic condition with much longer doubling time (6.0 h ± 20 min) than that of the wild-type strain (2.5 h ± 10 min).

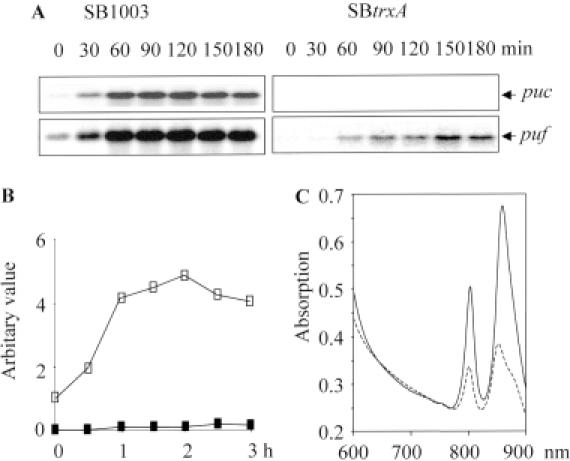

We have previously characterized the trxA mutant TK1 from R.sphaeroides, which accumulates less bacteriochlorophyll and less puf and puc mRNAs after a transition from growth under high oxygen tension to growth under low oxygen tension when compared with its parental wild-type strain (10). Similar results were observed for the trxA mutant of R.capsulatus. However, compared with strain TK1, the R.capsulatus trxA mutant accumulated much less bacteriochlorophyll (34 ± 3% of the level of wild type) due to the much lower TrxA protein level (<5% of the level of wild type) as detected by western analysis (data not shown). Intriguingly, we did not observe puc mRNA accumulation in the R.capsulatus trxA mutant after the transition from high to low oxygen tension, even though 20 μg of total RNA was loaded onto the gel for northern hybridization. Much less puf mRNA was detected in the R.capsulatus trxA mutant than in the wild-type strain (Figure 3A and B) after the transition of the culture. A very faint band for puc mRNA appeared only when the trxA mutant was constantly cultivated under low oxygen tension (data not shown). Accordingly, the reduced bacteriochlorophyll level in the trxA mutant of R.capsulatus was reflected by lower absorption peaks of photosynthetic complexes in whole-cell spectra (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Characterization of the trxA mutant of R.capsulatus. (A) Effect of TrxA on the expression of photosynthesis genes, i.e. the puf and puc operons. Cultures were grown aerobically until the optical density (OD660) reached 0.4 to 0.5, and then shifted to low oxygen tension. Total RNA was prepared and northern blot analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Quantification of the effect of TrxA on puf expression from the northern result (A). Closed square: trxA mutant; open square: wild type. (C) Absorption spectra of whole cells of wild type (solid line) and trxA mutant (dotted line). Cultures were grown semiaerobically in malate medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics overnight. Sample preparation and measurement were carried out as described in Materials and Methods.

Gyrase supercoiling activity in trx mutant strains

Gyrase catalyzes the introduction of negative supercoils into DNA (24). The protein binds to DNA as a tetramer of two A and two B subunits and wraps DNA into a positive supercoil. One region of duplex DNA is passed through another by means of DNA breakage and religation. The binding of ATP drives the supercoiling reaction, with ATP hydrolysis serving to reset the enzyme for a second round of catalysis. In the absence of ATP, gyrase also catalyzes the relaxation of negatively supercoiled DNA in an ATP-independent reaction. Since the ratio of ATP to ADP determines the final level of supercoiling (39,40), this makes gyrase activity sensitive to changes in intracellular energetics and, as a consequence, to the extracellular environment. Gyrase also facilitates the movement of the transcription complexes through DNA by introducing negative supercoils ahead of it and can influence transcription by bending and folding of DNA (41).

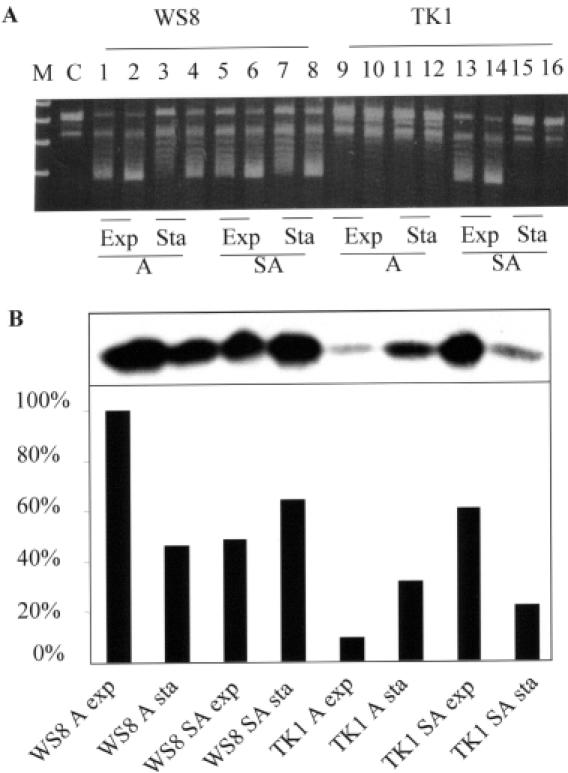

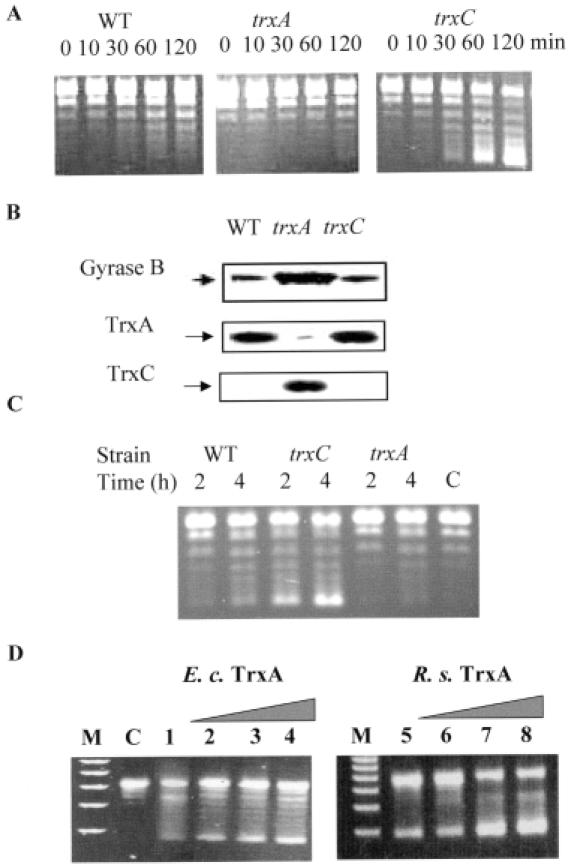

In order to study the effect of thioredoxin on gyrase activity, we investigated the gyrase supercoiling activities in vitro with cell extracts. We isolated extracts from R.capsulatus in order to study the effect of both TrxA and TrxC on supercoiling. We used R.sphaeroides extracts since this bacterium does not express TrxC and therefore allows direct conclusions on TrxA function. Aerobic extracts from R.sphaeroides strain TK1, which produces reduced amounts of TrxA, showed no significant supercoiling activity (Figure 4A). When higher amounts of cell extracts from mutant TK1 were used supercoiling was observed (data not shown), but at much lower levels than with extracts from wild type. This result was similar to that for the trxA mutant of R.capsulatus (Figure 5A and D). This suggests that strain TK1 indeed shows reduced supercoiling activity rather than increased topoisomerase I or nuclease activity. The supercoiling activity varied under different growth conditions and in different growth phases; however, the protein levels of TrxA mostly correlated well to the supercoiling activity (Figure 4B). Extracts from semiaerobically grown wild-type cells exhibited similar supercoiling activity as extracts from aerobically grown cells, despite the fact that the total amount of TrxA in semiaerobic extracts was only 50% of that in aerobic extracts. These results imply that not only the level of thioredoxin but also its redox state influences the supercoiling activity.

Figure 4.

TrxA affects gyrase supercoiling activity in R.sphaeroides. Exponential (OD660 = 0.6) or stationary (OD660 = 1.4) phase cells were harvested. Half of the cells were resuspended in sonication buffer I [25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl-fluoride (PMSF), 10% glycerol] for the supercoiling assay, and the other half in sonication buffer II (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl) for detection of TrxA protein levels. Cell extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Supercoiling activity of gyrase in cell extracts of wild-type WS8 and trxA mutant TK1. Two micrograms of total protein (cell extract) as determined by Bradford assay were incubated at room temperature in buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM DTT, 20 mM KCl, 1.5 mM ATP, 5 mM spermidine, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 μg/ml BSA) with 0.2 μg of relaxed plasmid pBluescript DNA, for 2 h or overnight at 37°C. SDS (0.2%) was added to stop the reaction, and the samples were analyzed by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. Odd numbers: 2 h incubation; even numbers: overnight incubation. A, aerobic condition; SA, semiaerobic condition; Exp, exponential phase; Sta, stationary phase. M, DNA marker; C, control without cell extract. (B) TrxA levels of WS8 and TK1 in different growth condition analyzed with western blot.

Figure 5.

TrxA and TrxC show opposing effects on the supercoiling activity of DNA gyrase. The exact method is described in the legend to Figure 4. Cell extracts used in this study are from semiaerobically grown culture in exponential phase. (A) Supercoiling activity of the cell extracts of SB1003 (WT) and trx mutants (trxA, trxC) of R.capsulatus. (B) Protein levels of GyrB, TrxA and TrxC in wild type and trx mutants of R.capsulatus analyzed by western blot. (C) Supercoiling assay with E.coli cell extracts. Wild type: Aegis256. trxC: Aegis257. trxA: Aegis262. C, relaxed pBluescript plasmid by DNA topisomerase I as a control, without cell extracts. (D) Supercoiling assays with purified gyrase from E.coli and TrxA from E.coli (E. c) and R.sphaeroides (R. s). C, relaxed plasmid without gyrase addition as in (C). To all other reactions 0.5 U of gyrase were added. Lanes 1–4: 0.0, 0.16, 0.5, 1.0 μM TrxA from E.coli; lanes 5–8: 0.0, 0.16, 0.5, 1.0 μM TrxA from R.sphaeroides.

When we tested cell-free extracts from R.capsulatus strains, the extracts from the trxC mutant strain SBtrxC showed higher supercoiling activity than extracts from the parental strain SB1003 in exponential phase under semiaerobic conditions (Figure 5A). We did not observe marked differences in supercoiling activity with extracts from the wild type and the trxC mutant strain which were cultivated under high oxygen tension (data not shown). Supercoiling activity of extracts from the trxA mutant was always lower than activities from extracts of the wild type and the trxC mutant, at high or low oxygen tension and in exponential or stationary phases (data not shown). Our results reveal that TrxC and TrxA have opposite effects on supercoiling activity. Under semiaerobic conditions TrxA enhances the supercoiling activity, while TrxC reduces gyrase activity.

The coumarin novobiocin inhibits the supercoiling activity of gyrase without affecting its ATP-independent relaxation activity by binding to the N-terminal fragment of gyrase B (42). The novobiocin binding site partially overlaps the ATP binding site and thus prevents ATP binding. The quinolone ciprofloxacin binds to DNA gyrase complexes and prevents religation of the DNA double-strand break (43). The supercoiling activity of gyrase is dependent on ATP hydrolysis. In order to verify that the supercoiling activity is from gyrase of Rhodobacter, the identical supercoiling assay was carried out without ATP or in the presence of novobiocin (75 nM) or ciprofloxacin (3 mM). No supercoiling activity was observed without ATP and the supercoiling activity was inhibited by novobiocin or ciprofloxacin (data not shown). This confirmed that the supercoiling observed after addition of cell-free extracts is catalyzed by gyrase.

To test whether the higher or lower supercoiling activity of gyrase in the cell extracts of trxC or trxA mutants arises from the higher or lower levels of gyrase protein, western blot analysis was performed with monoclonal antibodies directed against the N- or C- terminus of the gyrase A or B subunit of E.coli. The R.capsulatus trxC mutant contained a similar level of gyrase A and B subunits as the wild type, while the trxA mutant contained much higher levels of gyrase A and B subunits than the wild type or the trxC mutant (Figure 5B, gyrase A subunit not shown). The fact that the cell extracts of the trxA mutant exhibited lower supercoiling activity than that of the wild type despite higher levels of gyrase indicates that TrxA is very important for gyrase to change the DNA supercoiling status in the cells.

We also monitored the TrxA and TrxC protein levels in wild-type and mutant strains by the use of specific antibodies. In wild-type SB1003, TrxC was not detectable under any growth condition and in the different growth phases. However, TrxC was abundantly induced in the trxA mutant of R.capsulatus (Figure 5B). The higher expression of TrxC at low TrxA concentration suggests that TrxC can substitute some of the TrxA functions in R.capsulatus as previously reported for E.coli; however, no induction of TrxC is observed in a TrxA mutant of E.coli (44). This result indicates that the much lower supercoiling activity of cell extracts of trxA mutant strains may be at least partially due to the high abundance of TrxC in R.capsulatus.

In order to see whether the effect of thioredoxins on gyrase activity is a special feature in Rhodobacter or rather a general signaling pathway in bacteria, we also analyzed E.coli strains lacking either trxA or trxC. Extracts from an E.coli strain lacking trxA exhibited lower supercoiling activity than the parental wild type, while extracts from a strain lacking trxC exhibited stronger supercoiling activity (Figure 5C). These results suggest that TrxA and TrxC have the same opposite effect on gyrase activity in E.coli as observed in R.capsulatus.

In order to demonstrate that the different supercoiling activities were indeed caused by a direct effect of thioredoxins on gyrase, we performed additional assays with purified gyrase from E.coli and purified thioredoxin 1 from E.coli and R.sphaeroides. As shown in Figure 5D, an enhancement of the supercoiling activity was observed by the presence of increasing amounts of thioredoxin 1. This is in agreement with the lower supercoiling activity that we observed in the trxA mutants of Rhodobacter and E.coli, and suggests that no additional proteins are involved in the thioredoxin gyrase interaction.

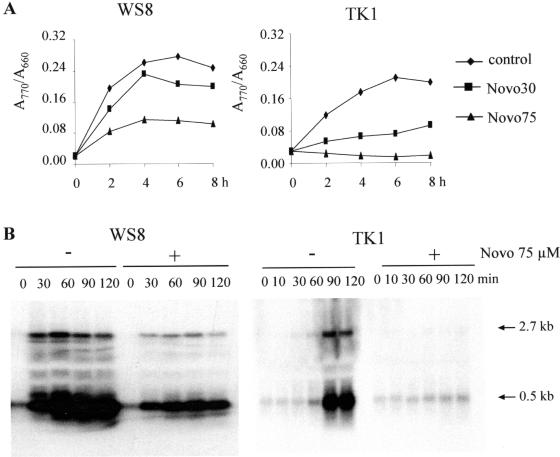

The effect of gyrase inhibitors on bacteriochlorophyll accumulation and the expression of photosynthesis genes

It was previously reported that novobiocin specifically inhibits the expression of certain photosynthesis genes in R.capsulatus (25). We tested the effect of novobiocin on bacteriochlorophyll accumulation and puf and puc mRNA levels in the different wild-type and trx mutant strains. The concentration (30 or 75 μM) of novobiocin applied did not affect the growth rate of the R.sphaeroides wild-type strain WS8 and trxA mutant TK1 after the transition of the cultures from high to low oxygen tension. However, the bacteriochlorophyll accumulation was inhibited, more severely in mutant TK1 than in WS8, even if the drug was added at the same time as the oxygen tension was reduced (Figure 6A). Quantification of mRNA levels by northern blot analysis revealed that there was still accumulation of the 0.5 kb pufBA mRNA in R.sphaeroides wild-type WS8, but not in strain TK1 in the presence of 75 μM novobiocin after lowering of oxygen tension (Figure 6B). The addition of novobiocin completely abolished the expression of puc mRNA in the wild-type WS8 and the trxA mutant TK1 (data not shown). When the oxygen tension was reduced without the addition of novobiocin, pufBA and pucBA mRNA levels increased by factors of about 35 and 75 in the wild type, and by factors of about 6–8 and 25, respectively, in the TK1 mutant (Figure 6B for puf, and figure for puc not shown).

Figure 6.

Effect of gyrase inhibitor novobiocin (Novo) on formation of the photosynthesis apparatus. Novo was added at the time point 0 as the oxygen tension in the cultures was reduced. (A) Novo inhibited accumulation of bacteriochlorophyll. Sample preparation and the measurement were described in Materials and Methods. Diamond, control without Novo; square, Novo addition (30 μM, Novo30); triangle: Novo addition (75 μM, Novo75). (B) Northern blot analysis of puf mRNA levels in wild-type and mutant strain TK1 of R.sphaeroides with or without addition of novobiocin. The 2.7 kb pufBALMX and the 0.5 kb pufBA mRNA segments are marked.

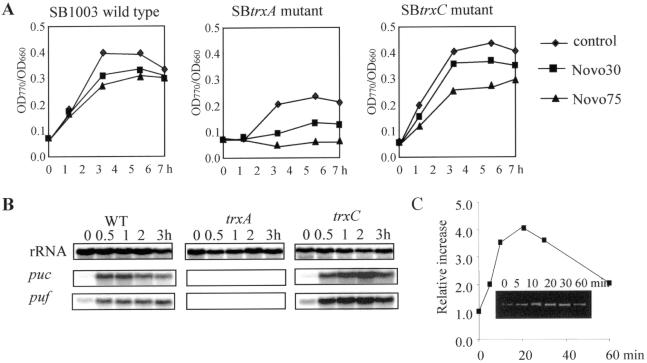

The effect of novobiocin on bacteriochlorophyll accumulation and puf and puc expression in R.capsulatus was similar as observed for R.sphaeroides. The addition of the identical concentration of novobiocin did not affect the growth of the R.capsulatus wild-type SB1003 or the trx mutants after a shift from high to low oxygen tension (data not shown). The bacteriochlorophyll accumulation was inhibited in wild-type SB1003 and the trxC mutant to the same extent, but more severely in the trxA mutant (Figure 7A), in which 75 μM of novobiocin abolished the bacteriochlorophyll accumulation. When mRNA levels of puf and puc were analyzed by northern blot after lowering the oxygen tension in the presence of novobiocin (75 μM), no expression of puf and puc was detectable in the trxA mutant (Figure 7B). puf and puc expression was still induced in the trxC mutant (3-fold induction of puf, 18.4-fold induction of puc) and in the wild type (2.9-fold induction of puf, 10-fold induction of puc) (Figure 7B), but to a much lower extent than in the control cultures without novobiocin treatment [trxC mutant: 9-fold induction of puf, 33-fold induction of puc; wild type: 6-fold induction of puf, 25-fold induction of puc (11)].

Figure 7.

Effect of gyrase inhibitor novobiocin (Novo) on bacteriochlorophyll accumulation (A), expression of puc and puf genes (B) and gyrB expression (C) of R.capsulatus. Novo was added at the time point 0 as the oxygen tension in the cultures was reduced. (A) Bacteriochlorophyll accumulation was inhibited during the Novo treatment after the oxygen tension was reduced. Bacteriochlorophyll content (A770) was normalized to the optical density of the culture. (B) Novo reduced the expression of photosynthesis genes as analyzed by northern blot. rRNA was probed as a control. For the control without Novo treatment see Figure 3 and Li et al. (11). (C) Quantification of gyrB expression during Novo treatment (30 μM) analyzed by RT–PCR. The inset shows the RT–PCR product (312 bp) of the gyrB gene.

The same effects on gene expression of puf and puc operons and the formation of photosynthetic complexes as for novobiocin were observed after addition of ciprofloxacin to a Rhodobacter culture (data not shown). The finding that growth of the strains used in this study was not affected by the presence of novobiocin (30 or 75 μM), but puf and puc expression was strongly reduced, suggests that the transcription of the puf and puc genes is very sensitive to the DNA conformation. In order to exclude the possibility that the inhibiting effect of novobiocin on gene expression is general, we monitored the mRNA level for gyrase B (gyrB) after novobiocin treatment by RT–PCR. Expression of gyrB increased 4-fold within 20 min after the addition of novobiocin (30 μM) (Figure 7C). Our inhibition studies verified that novobiocin inhibits the expression of photosynthesis genes by the action of gyrase and that TrxA and TrxC influence this inhibiting effect.

DISCUSSION

Thioredoxin influences many cellular processes by affecting the activity of other proteins by means of its thiol-redox control, as a hydrogen donor or by formation of protein complexes (45). Among its various cellular functions thioredoxin can also affect gene transcription. This effect can be mediated by a redox regulation of transcription factors as shown for NFκB or AP-1 in mammals (5). We have previously shown that thioredoxin also affects the transcription of the puf and puc genes in R.sphaeroides and in R.capsulatus which encode proteins of the photosynthetic apparatus (9,11). The signal chain from thioredoxin to puf and puc transcription, however, remained to be elucidated.

In order to unravel this signal chain we attempted to identify proteins interacting with thioredoxin. A model for an effect of thioredoxin on puf and puc transcription emerged, when we identified GyrB as a putative interaction partner of thioredoxin. Gyrase can affect transcription rates by its supercoiling or relaxation activities, since the local supercoiling of DNA can influence promoter activities (46–48). An effect of environmental factors such as temperature, oxidative stress, osmotic stress and pH changes on DNA supercoiling is well established (49). The influence of DNA supercoiling on gene expression can differ significantly for individual genes. Higher supercoiling can stimulate gene expression (e.g. topA in E.coli; ospAB promoter in Borrelia burgdorferi, osmotic stress responsive genes in E.coli, the fis gene of E.coli, ompR gene in Salmonella enterica) and can also decrease gene expression (e.g. ospC of B.burgdorferi, the sol and adc operons of Clostridium acetobutylicum, gyr expression in E.coli) (50–58). It is worth mentioning that it is difficult to accurately measure changes in the effective supercoiling density of the bacterial chromosome in vivo. This can be done by monitoring the products of the genes whose expression is correlated with the level of supercoiling. One such gene is gyrB, and the increased gyrB expression observed in R.capsulatus after addition of novobiocin (Figure 7C) and the increased levels of the GyrB protein in the trxA mutant (Figure 5B) strongly suggest that the supercoiling level in this mutant is significantly decreased. It has been reported previously that puf and puc expression depend on DNA supercoiling (25). Based on a new assay to measure supercoiling, a later study from the same group suggested that induction of anaerobic gene expression in R.capsulatus is not accompanied by local change in chromosomal supercoiling (59). However, our data using inhibitors of gyrase activity in wild-type and mutant strains of Rhodobacter strongly suggest an effect of gyrase on puf and puc expression. Whether gyrase affects puf and puc expression rather by change in superhelicity or by modulating DNA bending (60), and whether RNA polymerase activity is influenced directly or indirectly by binding of other proteins to the promoter region remains to be elucidated.

By analyzing wild-type and trx mutant strains of Rhodobacter with regard to gyrase activity and in response to gyrase inhibitors, we can demonstrate that gyrase activity is indeed influenced by thioredoxin. Considering the stimulatory effect of TrxA on gyrase activity, it is understandable that the trxA mutants, which exhibit lower gyrase activity, are more sensitive to novobiocin as observed by zone inhibition assays (data not shown), since novobiocin further reduces gyrase activity. The fact that the trxC mutant, which exhibits higher gyrase activity, shows the same sensitivity to novobiocin as the parental wild type indicates that the lack of the inhibiting TrxC cannot compensate the inhibitory effect of novobiocin. Our data demonstrate a role of thioredoxin in controlling DNA supercoiling. An effect of thioredoxin from Streptomyces aureofaciens on coiling of plasmid DNA was reported previously (61). From a number of in vitro experiments, these authors concluded that thioredoxin directly binds to the DNA randomly and introduces single-strand breaks allowing relaxation of the DNA. The correlation of TrxA levels and the supercoiling activity and the opposite effects of TrxA and TrxC on supercoiling activity as reported here argue against the application of this model for Rhodobacter.

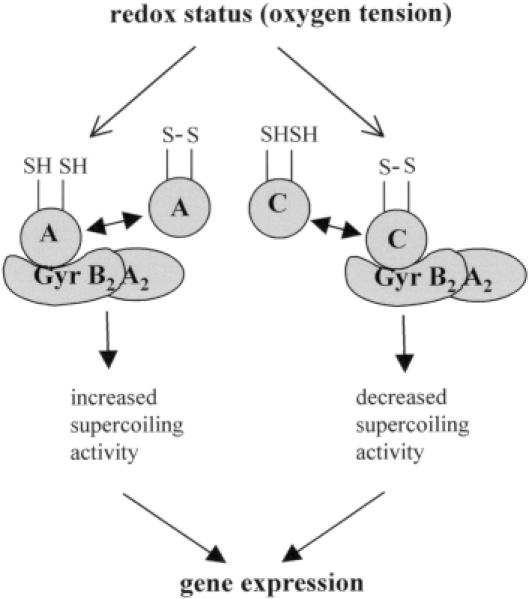

Interestingly, mutations in trxA or trxC showed opposite effects on gyrase activity. While extracts from the two trxA mutants showed lower supercoiling activity than extracts from wild-type cells, extracts from the R.capsulatus trxC mutant showed higher supercoiling activity. Even the higher levels of gyrase that we determined in the trxA mutant could not compensate the deficiency of the supercoiling activity of gyrase. Our data reveal that TrxC has an inhibiting effect on gyrase activity while TrxA has a stimulating effect. The gyrase domain encoded by the DNA fragment isolated from the Rhodobacter libraries overlaps the novobiocin and also the ATP binding site of GyrB (62). Nevertheless, the effect of thioredoxin on gyrase activity cannot be attributed to competition with ATP binding since TrxA has a stimulating effect. As also revealed by our in vitro binding studies, the thioredoxin effect on gyrase activity depends on its redox status. We present a model (Figure 8) in which a change in oxygen tension influences the redox state of thioredoxins, which consequently alters gyrase activity. Since oxidized TrxC inhibits gyrase activity while reduced TrxA stimulates gyrase activity, both thioredoxins mediate a signal leading to higher supercoiling activity at reduced redox potential. The opposite effects of TrxA and TrxC on supercoiling activity of gyrase correlate well with the opposite effect of trxA and trxC mutations on the expression of the photosynthesis genes and bacteriochlorophyll accumulation after reduction of oxygen tension in Rhodobacter (9,11). It has been reported that the redox potential in aerobically or anaerobically grown E.coli cells remains between −260 and −280 mV (63,64). Masuda and Bauer (23) demonstrated that the redox potential in aerobically or anaerobically grown cells of R.capsulatus is identical (−224 and −222 mV, respectively). Those indirect measurements of the internal ambient potential may, however, not reflect the in vivo situation since thioredoxin 1 changes its redox state in R.capsulatus grown at different oxygen tensions (Figure 2C). These data strongly suggest that cellular redox potentials are different in these two different growth conditions and that the signal chain from thioredoxin to gyrase involves a redox switch of thioredoxin.

Figure 8.

Schematic model for signal transduction from thioredoxin to gene expression in Rhodobacter. The redox switch of thioredoxins caused by a change in oxygen tension alters the supercoiling activity of gyrase, which further affects gene expression. A, TrxA; C, TrxC; GyrB2A2, gyrase tetramer with the two subunits, A and B.

Nevertheless, we have to consider that the redox-dependent influence of thioredoxins on gyrase activity is only part of the redox signal chain regulating the expression of photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter. As demonstrated before, expression of TrxA and TrxC in Rhodobacter are oppositely regulated by oxygen. In both Rhodobacter wild types, trxA expression is upregulated by oxygen, while trxC expression in R.capsulatus is downregulated (9,11). Furthermore, we observed an effect of TrxA on the gyrase level. Since we observed increased gyrase protein levels when supercoiling is decreased, this effect of TrxA on gyrase expression may also involve the thioredoxin–gyrase pathway, but other regulatory mechanisms can presently not be excluded. In Rhodobacter the thioredoxin–gyrase signaling pathway overlaps with RegB/RegA and CrtJ redox-dependent regulation.

Our data support a model in which thioredoxins of Rhodobacter act on photosynthesis gene expression by the action of gyrase. Although the expression of individual genes is differentially affected by the DNA topology, the differences in gyrase activity will certainly affect not only puf and puc expression, but also the expression of a number of Rhodobacter genes. Even the closely related species R.sphaeroides and R.capsulatus significantly differ in the composition of their thioredoxin systems, suggesting that the thioredoxin–gyrase signaling pathway may vary among individual species. We found the same effect of thioredoxins on gyrase activity in R.capsulatus and in E.coli. We, therefore, propose that the action of thioredoxins on gyrase activity is a general signaling pathway in bacterial systems.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Dr F. Katzen and Prof. J. Beckwith for E.coli strains Aegis256, 257, 262. We thank Alison Howells (John Innes Enterprises Ltd) and Lesley Mitchenall (John Innes Centre) for antibodies of GyrA and GyrB. K.L. performed part of this work as a fellow of DAAD. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Kl563/7-4, Kl563/16-1) and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. Work in A.M.'s laboratory was supported by BBSRC (UK).

REFERENCES

- 1.Laurent T.C., Moore,E.C. and Reichard,P. (1964) Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. IV. Isolation and characterization of thioredoxin, the hydrogen donor from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 239, 3436–3444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmgren A. (1984) Enzymatic reduction–oxidation of protein disulfides by thioredoxin. Methods Enzymol., 107, 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmel-Harel O. and Storz,G. (2000) Roles of the glutathione- and thioredoxin-dependent reduction systems in the Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae responses to oxidative stress. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 54, 439–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritz D. and Beckwith,J. (2001) Roles of thiol-redox pathways in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 55, 21–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulze-Osthoff K., Schenk,H. and Droge,W. (1995) Effects of thioredoxin on activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B. Methods Enzymol., 252, 253–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prinz W.A., Aslund,F., Holmgren,A. and Beckwith,J. (1997) The role of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin pathways in reducing protein disulfide bonds in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 15661–15667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller E.G. and Buchanan,B.B. (1989) Thioredoxin is essential for photosynthetic growth. The thioredoxin m gene of Anacystis nidulans. J. Biol. Chem., 264, 4008–4014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro F. and Florencio,F.J. (1996) The cyanobacterial thioredoxin gene is required for both photoautotrophic and heterotrophic growth. Plant Physiol., 111, 1067–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasternak C., Assemat,K., Clement-Metral,J.D. and Klug,G. (1997) Thioredoxin is essential for Rhodobacter sphaeroides growth by aerobic and anaerobic respiration. Microbiology, 143, 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasternak C., Haberzettl,K. and Klug,G. (1999) Thioredoxin is involved in oxygen regulated formation of the photosynthetic apparatus of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 181, 100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li K., Hartig,E. and Klug,G. (2003) Thioredoxin 2 is involved in oxidative stress defence and redox-dependent expression of photosynthesis genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Microbiology, 149, 419–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregor J. and Klug,G. (1999) Regulation of bacterial photosynthesis genes by oxygen and light. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 179, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregor J. and Klug,G. (2002) Oxygen-regulated expression of genes for pigment binding proteins in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 4, 249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi H.M. and Tabita,F.R. (1996) A global two component signal transduction system that integrates the control of photosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 14515–14520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swem L.R., Elsen,S., Bird,T.H., Swem,D.L., Koch,H.G., Myllykallio,H., Daldal,F. and Bauer,C.E. (2001) The RegB/RegA two-component regulatory system controls synthesis of photosynthesis and respiratory electron transfer components in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Biol., 309, 121–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kappler U., Huston,W.M. and McEwan,A.G. (2002) Control of dimethylsulfoxide reductase expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus: the role of carbon metabolites and the response regulators DorR and RegA. Microbiology, 148, 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosley C.S., Suzuki,J. and Bauer,C.E. (1994) Identification and molecular genetic characterization of a sensor kinase responsible for coordinately regulating light harvesting and reaction center gene expression in response to anaerobiosis. J. Bacteriol., 176, 7566–7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue K., Kouadio,J.L., Mosley,C.S. and Bauer,C.E. (1995) Isolation and in vitro phosphorylation of sensory transduction components controlling anaerobic induction of light harvesting and reaction center gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Biochemistry, 34, 391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swem L.R., Kraft,B.J., Swem,D.L., Setterdahl,A.T., Masuda,S., Knaff,D.B., Zaleski,J.M. and Bauer,C.E. (2003) Signal transduction by the global regulator RegB is mediated by a redox-active cysteine. EMBO Rep., 22, 4699–4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du S., Bird,T.H. and Bauer,C.E. (1998) DNA binding characteristics of RegA. A constitutively active anaerobic activator of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 18509–18513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomelsky M. and Kaplan,S. (1998) AppA, a redox regulator of photosystem formation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1, is a flavoprotein. Identification of a novel FAD binding domain. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 35319–35325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braatsch S., Gomelsky,M., Kuphal,S. and Klug,G. (2002) A single flavoprotein, AppA, integrates both redox and light signals in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol., 45, 827–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masuda S. and Bauer,C.E. (2002) AppA is a blue light photoreceptor that antirepresses photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Cell, 110, 613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reece R.J. and Maxwell,A. (1991) DNA gyrase: structure and function. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol., 26, 335–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Y.S. and Hearst,J.E. (1988) Transcription of oxygen-regulated photosynthetic genes requires DNA gyrase in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 4209–4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drews G. (1983) Mikrobiologisches Praktikum. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assemat K., Alzari,P.M. and Clement-Metral,J.D. (1995) Conservative substitutions in the hydrophobic core of Rhodobacter sphaeroides thioredoxin produce distinct functional effects. Protein Sci., 4, 2510–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amann E., Brosius,J. and Ptashne,M. (1983) Vectors bearing a hybrid trp-lac promoter useful for regulated expression of cloned genes in Escherichia coli. Gene, 25, 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hübner P., Masepohl,B., Klipp,W. and Bickle,T.A. (1993) nif gene expression studies in Rhodobacter capsulatus: ntrC-independent repression by high ammonium concentrations. Mol. Microbiol., 10, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon R., Priefer,U. and Puehler,A. (1983) A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Biotechnology, 1, 784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otter R. and Cozzarelli,N.R. (1983) Escherichia coli DNA gyrase. Methods Enzymol., 100, 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatterji M., Unniraman,S., Maxwell,A. and Nagaraja,V. (2000) The additional 165 amino acids in the B protein of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase have an important role in DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 22888–22894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hemschemeier S.K., Ebel,U., Jaeger,A., Bazler,A., Kirndorfer,M. and Klug,G. (2000) In vivo and in vitro analysis of RegA response regulator mutants of Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 2, 291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauer C.E., Elsen,S., Swem,L.R., Swem,D.L. and Masuda,S. (2003) Redox and light regulation of gene expression in photosynthetic prokaryotes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci., 358, 147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasaki Y., Kozaki,A. and Hatano,M. (1997) Link between light and fatty acid synthesis: thioredoxin-linked reductive activation of plastidic acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 11096–11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemaire S.D., Guillon,B., Le Marechal,P., Keryer,E., Miginiac-Maslow,M. and Decottignies,P. (2004) New thioredoxin targets in the unicellular photosynthetic eukaryote Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 7475–7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamazaki D., Motohashi,K., Kasama,T., Hara,Y. and Hisabori,T. (2004) Target proteins of the cytosolic thioredoxins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol., 45, 18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis R.J., Singh,O.M.P., Smith,C.V., Skarynski,T., Maxwell,A., Wonacott,A.J. and Wigley,D.B. (1996) The nature of inhibition of DNA gyrase by the coumarins and the cyclothialidines revealed by x-ray crystallography. EMBO Rep., 15, 1412–1420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westerhoff H.V., O'Dea,M.H., Maxwell,A. and Gellert,M. (1988) DNA supercoiling by DNA gyrase. A static head analysis. Cell Biophys., 12, 157–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drlica K. (1992) Control of bacterial supercoiling. Mol. Microbiol., 6, 425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malik M., Bensaid,A., Rouviere-Yaniv,J. and Drlica,K. (1996) Histone-like protein HU and bacterial DNA topology: suppression of an HU deficiency by gyrase mutations. J. Mol. Biol., 256, 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kampranis S.C., Gormley,N.A., Tranter,R., Orphanides,G. and Maxwell,A. (1999) Probing the binding of coumarins and cyclothialidines to DNA gyrase. Biochemistry, 38, 1967–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drlica K. and Malik,M. (2003) Fluoroquinolones: action and resistance. Curr. Top. Med. Chem., 3, 249–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miranda-Vizuete A., Damdimopoulos,A.E., Gustafsson,J.-A. and Spyrou,G. (1997) Cloning, expression, and characterization of a novel Escherichia coli thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 30841–30847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arner E.S. and Holmgren,A. (2000) Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur. J. Biochem., 267, 6102–6109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitehall S., Austin,S., Dixon,R. (1993) The function of the upstream region of the sigma 54-dependent Klebsiella pneumoniae nifL promoter is sensitive to DNA supercoiling. Mol. Microbiol, 9, 1107–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karem K. and Foster,J.W. (1993) The influence of DNA topology on the environmental regulation of a pH-regulated locus in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol., 10, 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leclerc G.J., Tartera,C. and Metcalf,E.S. (1998) Environmental regulation of Salmonella typhi invasion-defective mutants. Infect. Immun., 66, 682–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rui S. and Tse-Dinh,Y.C. (2003) Topoisomerase function during bacterial responses to environmental challenge. Front. Biosci., 8, 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tseh-Dinh Y.C. and Beran,R.K. (1988) Multiple promoters for transcription of the Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I gene and their regulation by DNA supercoiling. J. Mol. Biol., 202, 735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneider R., Travers,A. and Muskhelishvili,G. (2000) The expression of the Escherichia coli fis gene is strongly dependent on the superhelical density of DNA. Mol. Microbiol., 38, 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Celia H., Hoermann,L., Schultz,P., Lebeau,L., Mallouh,V., Wigley,D.B., Wang,J.C., Mioskowski,C. and Oudet,P. (1994) Three-dimensional model of Escherichia coli gyrase B subunit crystallized in two-dimensions on novobiocin-linked phospholipid films. J. Mol. Biol., 236, 618–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Durre P., Bohringer,M., Nakotte,S., Schaffer,S., Thormann,K. and Zickner,B. (2002) Transcriptional regulation of solventogenesis in Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 4, 295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bang I.S., Audia,J.P., Park,Y.K. and Foster,J.W. (2002) Autoinduction of the OmpR response regulator by acid shock and control of the Salmonella enterica acid tolerance response. Mol. Microbiol., 44, 1235–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheung K.J., Badarinarayana,V., Selinger,D.W., Janse,D. and Church,G.M. (2003) A microarray-based antibiotic screen identifies a regulatory role for supercoiling in the osmotic stress response of Escherichia coli. Genome Res., 13, 206–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alverson J., Bundle,S.F., Sohaskey,C.D., Lybecker,M.C. and Samuels,D.S. (2003) Transcriptional regulation of the ospAB and ospC promoters from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol., 48, 1665–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Franco R.J. and Drlica,K. (1989) Gyrase inhibitors can increase gyrA expression and DNA supercoiling. J. Bacteriol., 171, 6573–6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Straney R., Krah,R. and Menzel,R. (1994) Mutations in the -10 TATAAT sequence of the gyrA promoter affect both promoter strength and sensitivity to DNA supercoiling. J. Bacteriol., 176, 5999–6006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cook D.N., Armstrong,G.A. and Hearst,J.E. (1989) Induction of anaerobic gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus is not accompanied by a local change in chromosomal supercoiling as measured by a novel assay. J. Bacteriol., 171, 4836–4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Auner H., Buckle,M., Deufel,A., Kutateladze,T., Lazarus,L., Mavathur,R., Muskhelishvili,G., Pemberton,I., Schneider,R. and Travers,A. (2003) Mechanism of transcriptional activation by FIS: role of core promoter structure and DNA topology. J. Mol. Biol., 331, 331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Golubnitchaya-Labudova O., Horecka,T., Kapalla,M., Perecko,D., Kutejova,E. and Lubec,G. (1998) Thioredoxin from Streptomyces aureofaciens controls coiling of plasmid DNA. Life Sci., 62, 397–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maxwell A. and Lawson,D.M. (2003) The ATP-binding site of type II topoisomerases as a target for antibacterial drugs. Curr. Top. Med. Chem., 3, 283–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng M., Aslund,F. and Storz,G. (1998) Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science, 279, 1718–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aslund F., Zheng,M., Beckwith,J. and Storz,G. (1999) Regulation of the OxyR transcription factor by hydrogen peroxide and the cellular thiol-disulfide status. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 6161–6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stewart E.J., Aslund,F. and Beckwith,J. (1998) Disulfide bond formation in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm: an in vivo role reversal for the thioredoxins. EMBO Rep., 17, 5543–5550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yen H.C. and Marrs,B. (1976) Map of genes for carotenoid and bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Bacteriol., 126, 619–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sistrom W.R. (1977) Transfer of chromosoma fens mediated by plasmid R68.45 in Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol., 131, 526–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barany F. (1985) Two-codon insertion mutagenesis of plasmid genes by using single-stranded hexameric oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 82, 4202–4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]