Abstract

Viral infection is an exacerbating factor contributing to chronic airway diseases, such as asthma, via mechanisms that are still unclear. Polyinosine-polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)), a Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) agonist used as a mimetic to study viral infection, has been shown to elicit inflammatory responses in lungs and to exacerbate pulmonary allergic reactions in animal models. Previously, we have shown that poly(I:C) stimulates lung fibroblasts to accumulate an extracellular matrix (ECM), enriched in hyaluronan (HA) and its binding partner versican, which promotes monocyte adhesion. In the current study, we aimed to determine the in vivo role of versican in mediating inflammatory responses in poly(I:C)-induced lung inflammation using a tamoxifen-inducible versican-deficient mouse model (Vcan−/− mice). In C57Bl/6 mice, poly(I:C) instillation significantly increased accumulation of versican and HA, especially in the perivascular and peribronchial regions, which were enriched in infiltrating leukocytes. In contrast, versican-deficient (Vcan−/−) lungs did not exhibit increases in versican or HA in these regions and had strikingly reduced numbers of leukocytes in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and lower expression of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines. Poly(I:C) stimulation of lung fibroblasts isolated from control mice generated HA-enriched cable structures in the ECM, providing a substrate for monocytic cells in vitro, whereas lung fibroblasts from Vcan−/− mice did not. Moreover, increases in proinflammatory cytokine expression were also greatly attenuated in the Vcan−/− lung fibroblasts. These findings provide strong evidence that versican is a critical inflammatory mediator during poly(I:C)-induced acute lung injury and, in association with HA, generates an ECM that promotes leukocyte infiltration and adhesion.

Keywords: double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), extracellular matrix, hyaluronan, leukocyte, versican (VCAN), Lung inflammation, Poly(I:C)

Introduction

Viral lung infection is one of the exacerbating factors contributing to chronic lung diseases, such as asthma (1–6). During acute lung inflammation, extracellular matrix (ECM)6 around blood vessels and airways remodels to allow for infiltration of leukocytes. This “provisional” ECM involves accumulation of the hygroscopic molecules hyaluronan (HA) and the chondroitin sulfate (CS) proteoglycan (PG) versican, which together create a loose and hydrated space necessary for leukocyte ingress and additionally for migration and expansion of resident stromal cells. Versican expression, which is high in lungs during embryonic development (7–9) but low in adult lungs, is reactivated in numerous lung diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and asthma (10–18). Our published work has shown that versican and molecules that associate with versican, such as HA, are the principal ECM components that accumulate in inflamed lungs at early times following exposure to pathogens, such as LPS (19). The accumulation of a versican-enriched ECM coincides with invasion and retention of leukocytes within different compartments of the lung during these early inflammatory responses. Previous studies have shown that bronchial fibroblasts cultured from subjects with asthma have elevated production of versican (14, 20, 21), and in a recent study in a cockroach antigen-induced mouse model of asthma, we showed that versican, produced by airway epithelial cells, consistently accumulates in the subepithelial space and precedes infiltration of leukocytes, suggesting a specific immunomodulatory role for versican (22). Whether the acute lung inflammation stimulated by viral infection worsens asthma by altering the ECM microenvironment to facilitate leukocyte infiltration and accumulation is not yet known. One of the major inflammatory signaling pathways activated by virus is the Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) pathway, which recognizes double-stranded RNA, such as polyinosine-polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)), and thus is often used as a viral mimetic and a TLR3 agonist. It has been shown to generate an HA-enriched ECM in colon and in kidney, which promotes leukocyte accumulation (23–27), and has also been shown to elicit acute lung inflammation in vivo and further to exacerbate pulmonary allergic reactions (28, 29). A number of studies by our group have demonstrated that lung fibroblasts synthesize and deposit HA- and versican-enriched ECM in response to poly(I:C). This ECM is strongly adhesive for monocytes and T lymphocytes and is hyaluronidase-sensitive, indicating that HA is a necessary component of this adhesive ECM (30–33). Interfering with versican accumulation in this ECM also inhibits leukocyte adhesion in vitro, suggesting that versican and HA may form an immunomodulatory complex in response to viral lung infection (32–34). However, specific roles for versican in the regulation of pulmonary inflammatory responses are not yet well defined due to lack of versican knock-out animals, which are embryonically lethal due to defective cardiac development (35). In this study, we examine the formation of HA- and versican-enriched ECM in lungs of conditionally versican-deficient mice, developed recently in our laboratory, in response to poly(I:C) as a surrogate for viral infection. We report that global deficiency of versican perturbs both the accumulation of HA and the accumulation and infiltration of leukocytes, demonstrating that versican is a critical ECM component mediating HA-dependent leukocyte accumulation in the lungs and a potential therapeutic target.

Results

Poly(I:C) Instillation in Lungs Significantly Increases HA and Versican Accumulation Associated with Infiltrating Leukocytes

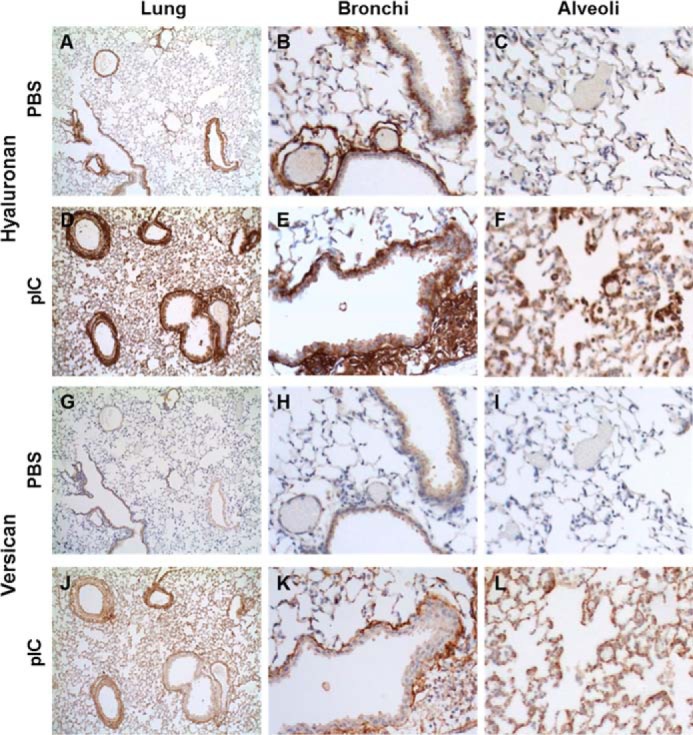

The distribution of HA and versican was initially examined in unchallenged and poly(I:C)-instilled lungs of 8–10-week-old C57Bl/6 mice. In the unchallenged animals, moderate to strong HA staining was present in the stromal connective tissues of airways but not in alveolar sacs. In the pulmonary vasculature, moderate to strong HA staining was present mostly in the adventitial and peri-adventitial regions (Fig. 1, A–C). Versican levels were low throughout the lung with weak staining in the epithelium of bronchi and bronchioles (Fig. 1 (G–I) and Table 1). HA and versican accumulation associated with infiltrating leukocytes was prominent 48 h after the second poly(I:C) instillation in the perivascular and peribroncheal spaces as well as in the alveolar septa (Fig. 1 (D–H and J–L) and Table 1). These in vivo observations support our previously published in vitro findings that poly(I:C) treatment of lung fibroblasts promotes the formation of an HA- and versican-rich ECM, which enhances monocyte binding (30–32). These findings led us to hypothesize that versican plays an intergral role in promoting leukocyte infiltration into lungs during poly(I:C)-induced pulmonary inflammation. To test this hypothesis, and because the homozygous hdf (heart defect) mouse that lacks Vcan expression (35) is embryonic lethal, we developed a novel mouse strain with conditional global versican deficiency, which enabled us to study the contribution of versican to inflammation in adult animals.

FIGURE 1.

HA and versican staining in PBS- (A–C and G–I) and poly(I:C)- (pIC) (D–F and J–L) instilled lungs. HA, which is present in areas surrounding bronchi and vasculature (B) and generally absent in alveolar spaces of unstimulated lungs (C), greatly increases in response to poly(I:C) stimulation (D), especially in areas enriched in infiltrating leukocytes (E), including the alveolar spaces (F). Versican, in contrast, is almost absent in PBS-treated lungs (G–I) but accumulates markedly in poly(I:C)-stimulated lungs (J), both in the peribronchial area (K) and in alveoli (L).

TABLE 1.

HA and versican staining in unchallenged and poly(I:C)-stimulated lungs

0, no staining; +, ++, +++, ++++, level of staining intensity.

| Control |

Poly(I:C) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | Versican | HA | Versican | |

| Airways | ||||

| Bronchi | ||||

| Epithelium | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Stroma | +++ | 0/+ | +++ | +++ |

| Bronchioles | ||||

| Epithelium | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Stroma | +++ | 0 | +++ | +++ |

| Respiratory bronchioles | ||||

| Epithelium | 0 | + | ++ | ++ |

| Stroma | ++ | 0 | +++ | +++ |

| Alveoli | ||||

| Alveolar ducts | ++ | 0/+ | +++ | +++ |

| Alveolar sacs (rims) | + | 0 | ++ | ++ |

| Alveolar walls | 0/+ | 0 | ++ | +++ |

| Vessels | ||||

| Pulmonary arteries (bronchi) | ||||

| Endothelium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/+ |

| Media | 0 | 0/+ | 0/+ | ++ |

| Adventitia | ++ | 0 | ++ | +++ |

| Peri-adventitial | +++ | 0 | ++++ | +++ |

| Pulmonary arteries (bronchioles) | ||||

| Endothelium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0/+ |

| Media | 0 | 0/+ | 0/+ | +++ |

| Adventitia | ++ | 0 | +++ | +++ |

| Peri-adventitial | +++ | 0 | ++++ | +++ |

| Pulmonary veins | ||||

| Endothelium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Media | + | 0 | +++ | +++ |

| Adventitia | ++ | 0 | +++ | +++ |

| Venules | ||||

| Endothelium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wall | + | 0 | ++++ | +++ |

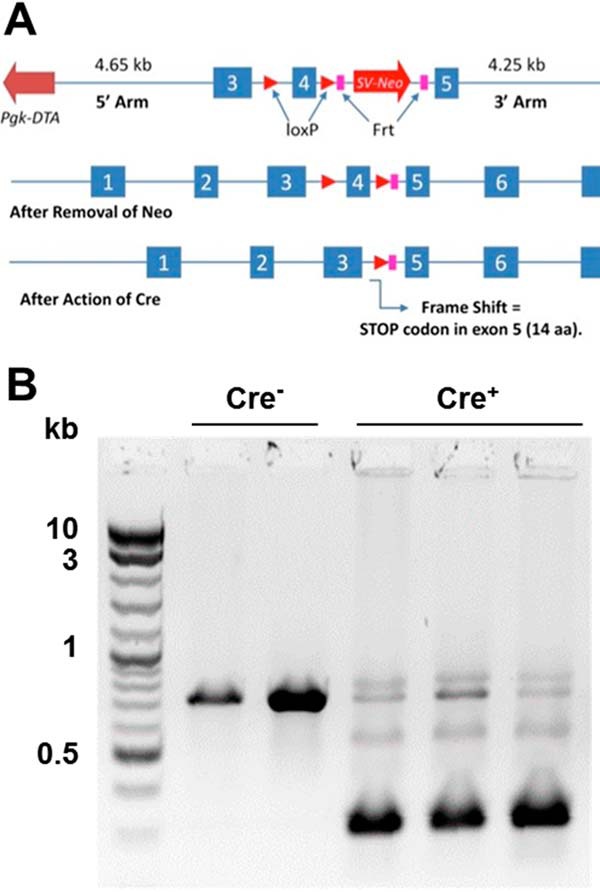

Generation of Conditional Versican-deficient Mice

Conditional versican-deficient (Vcan−/−) mice were successfully generated by inserting LoxP sites flanking exon 4 of the Vcan gene on the C57Bl/6 genetic background (Fig. 2A). When these B6.Vcan-e4fl/fl mice were crossed to Rosa26-CreERT2 mice, deletion of exon 4 was successfully achieved after treating the mice with tamoxifen (Fig. 2B). Deletion of exon 4 results in the generation of a stop codon in exon 5, preventing versican expression.

FIGURE 2.

Generation of versican conditional knock-out mice. A, LoxP sites were inserted in regions flanking versican exon 4 in C57BL6 background, targeted to create an early stop codon after the Cre recombinase induced frameshift. B, when tamoxifen was injected into these B6.Vcan-e4fl/fl mice (Cre−; control) or B6.Vcan-e4fl/fl/Rosa26-CreERT2 mice (Cre+; Vcan−/−), Cre-dependent exon 4 excision was detected, as shown by the size shift of the PCR product across exon 4 (B).

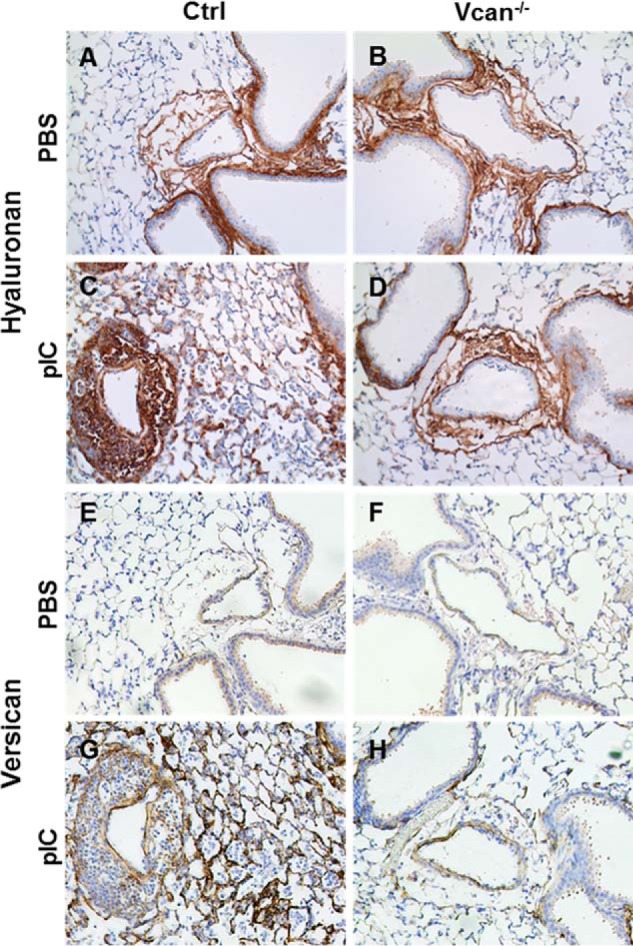

Poly(I:C)-induced Increase in Expression and Accumulation of Versican and HA Is Significantly Attenuated in Vcan−/− Mice

Vcan−/− animals and littermate controls lacking Cre were treated with poly(I:C) and observed after 48 h, when the inflammatory response was at its peak. Distribution of HA and versican accumulation in PBS-treated control and Vcan−/− animals were similar to our findings in wild type C57Bl/6 mice (Fig. 3, A and B and E and F). Poly(I:C) induced the accumulation of HA- and versican-enriched ECM in the perivascular and peribronchial spaces in the inflamed lungs of control animals (Fig. 3, C and G). This ECM accumulation was reduced in Vcan−/− mice. Both HA and versican accumulation were dramatically reduced in Vcan−/− lungs (Fig. 3, D and H).

FIGURE 3.

Vcan and HA accumulation induced by poly(I:C) (pIC) is attenuated in Vcan−/− mice. HA (A–D) and Vcan (E–H) staining on adjacent lung tissue sections of control (A, C, E, and G) and Vcan−/− (B, D, F, and H) mice treated with PBS (A, B, E, and F) and poly(I:C) (C, D, G, and H) demonstrate that Vcan and HA accumulation induced by poly(I:C) in control mice is attenuated in Vcan−/− mice.

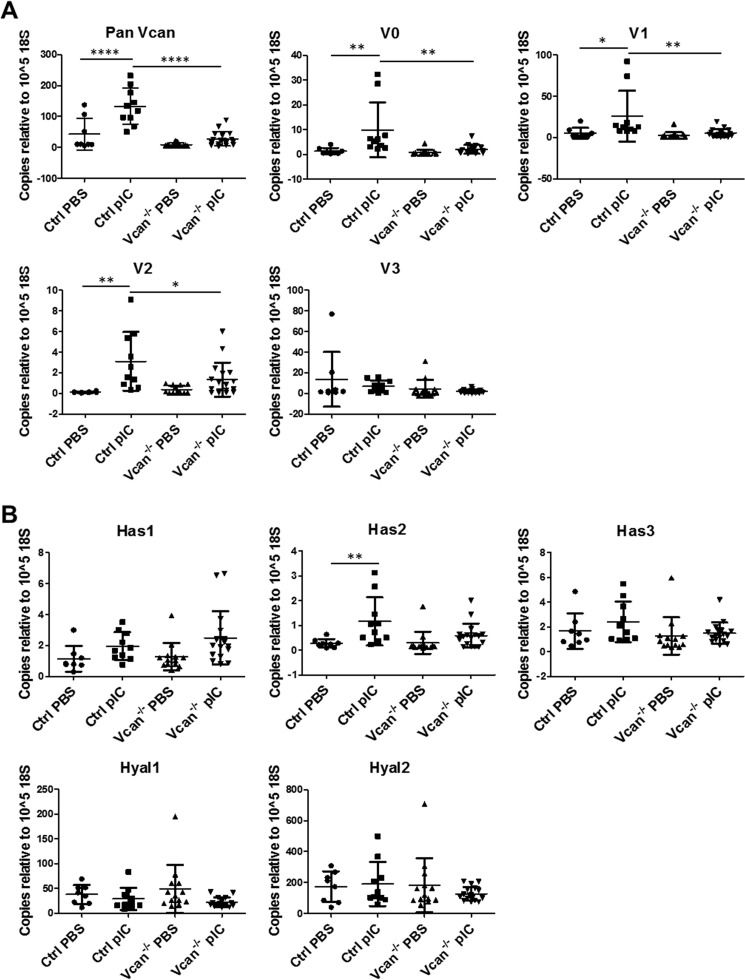

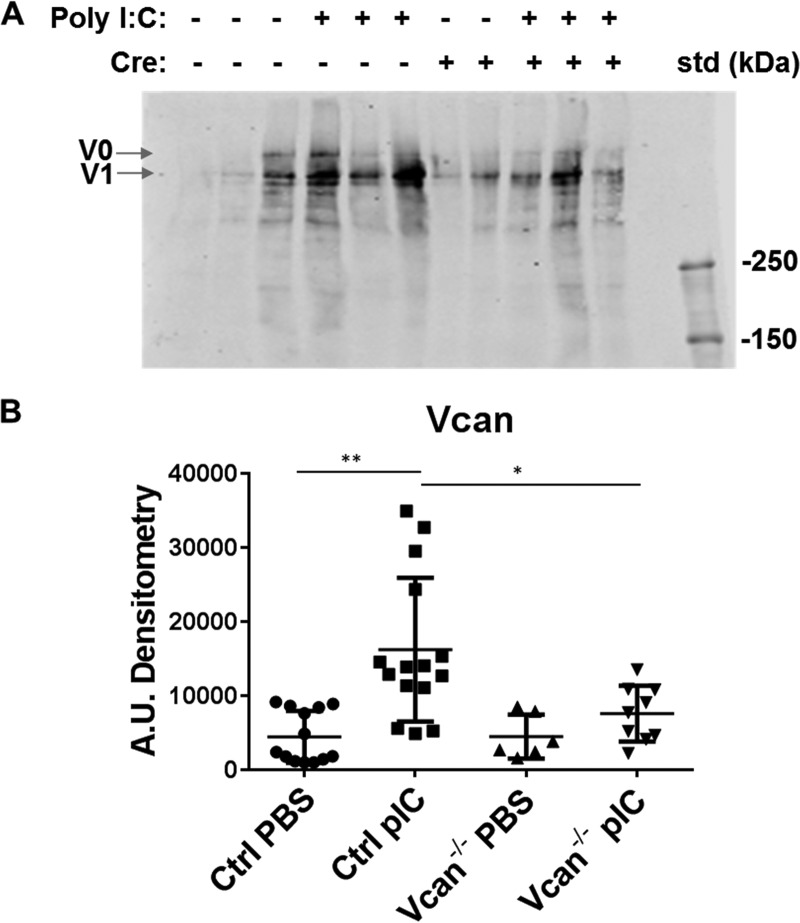

Messenger RNA levels of all isoforms of versican in unchallenged lungs were low in both control and Vcan−/− animals and not significantly different between genotypes. In response to poly(I:C) challenge, however, total versican mRNA levels significantly increased in lungs of control animals but not in Vcan−/− animals (Fig. 4A). Specifically, levels of V0, V1, and V2 versican isoforms were significantly increased in poly(I:C)-challenged lungs but showed no significant elevation in Vcan−/− animals (Fig. 4A). Hyaluronan synthase 2 (Has2) mRNA levels were also significantly increased in poly(I:C)-challenged control animals but not in Vcan−/− animals (Fig. 4B). Similarly, poly(I:C) challenge induced significant increase in protein accumulation of versican in the lungs in control animals but not in Vcan−/− animals (Fig. 5, A and B). When normalized to Vcan mRNA levels in PBS-treated control lungs, Vcan mRNA levels in poly(I:C)-treated control lungs increased to 310 ± 43%, whereas PBS- and poly(I:C)-treated Vcan−/− lungs were 20 ± 4 and 64 ± 13% of PBS-treated control lungs, respectively (supplemental Fig. 1). This represents a nearly 80% reduction in PBS- as well as poly(I:C)-induced gene expression in Vcan−/− lungs. Similarly, normalized Vcan protein levels in poly(I:C)-treated control lungs increased to 365 ± 57%, whereas PBS- and poly(I:C)-treated Vcan−/− lungs were at 100 ± 27 and 170 ± 28% of PBS-treated control lungs, respectively. This translates to no significant change in protein levels in PBS-treated lungs but a 53.4% reduction in poly(I:C)-stimulated Vcan protein in Vcan−/− lungs. When calculated as a percentage of induction above PBS-treated lungs, poly(I:C)-treated Vcan−/− lungs had 78.8% less mRNA and 73.6% less protein than poly(I:C)-treated controls.

FIGURE 4.

Gene expression levels of versican isoforms, hyaluronan synthases, and hyaluronidases in response to poly(I:C) (pIC) instillation in lungs of control and Vcan−/− mice. A, expression of total versican (Vcan) and isoforms 1 (V1) and 2 (V2), significantly elevated in response to poly(I:C) in the lungs of control mice, is attenuated in Vcan−/− mice. B, hyaluronan synthase 2 (Has2) expression is also elevated in lungs of control animals exposed to poly(I:C), which is once again attenuated in Vcan−/− mice. Gene expression levels of hyaluronidases are not affected by instillation of poly(I:C). n = 8–17 mice/group. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ****, p < 0.0001. Error bars, S.D.

FIGURE 5.

A and B, protein levels of Vcan in whole lung extracts as measured by Western blot (A) were also significantly increased by poly(I:C) (pIC) stimulation in control mice (Cre−) but not in Vcan−/− (Cre+) mice, as quantified by densitometry (B). n = 6–15 mice/group. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. Error bars, S.D.

Poly(I:C)-induced Accumulation of Leukocytes in HA- and Versican-enriched ECM Is Significantly Attenuated in Vcan−/− Mice

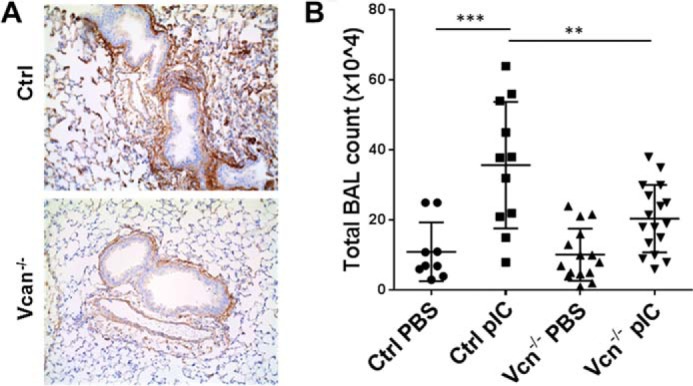

We observed that leukocyte accumulation associated with a versican- and HA-enriched ECM in poly(I:C)-challenged lungs was blunted in Vcan−/− mice (Fig. 6A). To confirm this finding, we examined whether the numbers of total cells in broncoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from poly(I:C)-challenged animals were affected by versican deficiency. Total cell counts in BALF increased in response to poly(I:C) challenge in control animals, which was significantly reduced in Vcan−/− mice (Fig. 6B). These BALF cells were further subjected to flow cytometry analysis to examine differential counts of leukocytes. The relative percentages of neutrophils, alveolar macrophages, dendritic cells, B and T lymphocytes, eosinophils, and interstitial macrophages in the BALF were not significantly affected by reduction in versican (supplemental Fig. 2, A–C).

FIGURE 6.

Leukocyte infiltration into lungs in response to poly(I:C) (pIC) instillation. A, instillation of poly(I:C)-induced leukocyte infiltration into lungs associated with regions of Vcan accumulation in control mice, which was diminished in Vcan−/− mice. B, consistently, total leukocyte numbers in BALF were significantly decreased in Vcan−/− mice. n = 9–17 mice/group. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.D.

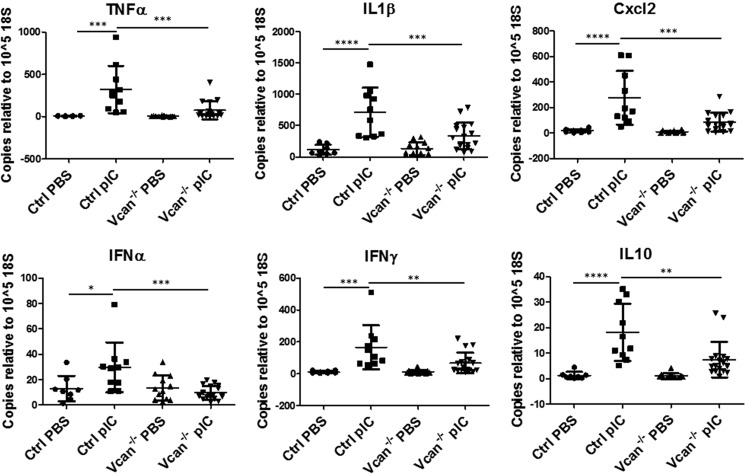

Versican Deficiency Significantly Blunts Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines Stimulated by Poly(I:C)

We further examined whether the presence of versican affects the inflammatory cytokines and chemokines induced by poly(I:C) challenge. In total lung lysates, poly(I:C) significantly increased expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including TNFα, IL1β, MIP2 (Cxcl2), IFNα, IFNγ, and IL10, in control mice. This response was attenuated or absent in Vcan−/− mice (Fig. 7). To determine whether there was a direct relationship between versican expression and cytokine levels, we performed linear regression analysis and found a significant positive relationship between versican and levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (supplemental Fig. 3).

FIGURE 7.

Expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in response to poly(I:C) (pIC) instillation in lungs. PIC instillation induced increases in inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as TNFα, IL1β, Cxcl2, IFNα, IFNγ, and IL10, in whole lungs of control mice, which were attenuated in Vcan−/− mice. n = 8–17 mice/group. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. Error bars, S.D.

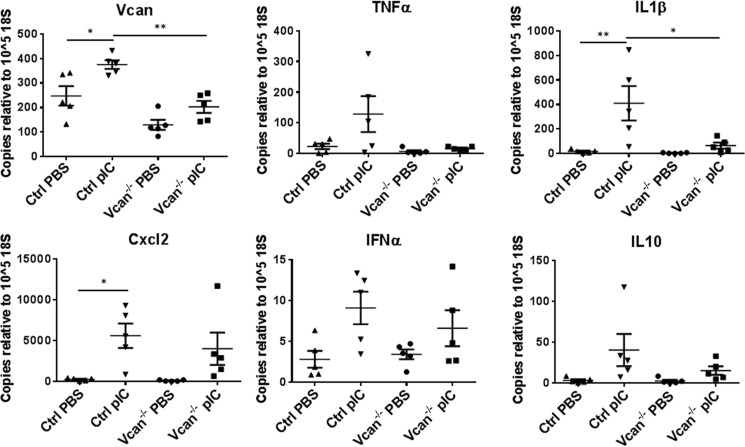

Poly(I:C)-induced Cytokine Expression Is Blunted in Cultured Lung Fibroblasts from Vcan−/− Mice

We further examined whether versican deficiency affected the expression of cytokines and chemokines in lung stromal fibroblasts in vitro. Cultured primary lung fibroblasts, isolated from control and Vcan−/− mice, were treated with PBS or poly(I:C), and expression of cytokines and chemokines was measured. Poly(I:C) stimulation induced a significant increase in transcript levels of versican as well as IL1β expressed by control lung fibroblasts, consistent with the changes shown in the poly(I:C)-instilled lungs. In contrast, lung fibroblasts isolated from Vcan−/− mice showed significantly reduced levels of IL1β as well as versican (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Gene expression of versican, inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines in cultured lung fibroblasts in response to poly(I:C) (pIC). PIC treatment induced increases in total versican as well as IL1β in primary cultured lung fibroblasts from control mice, which was significantly reduced in Vcan−/− fibroblasts. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. Results are mean values from each independent experiment run in triplicate each time. n = 5 independent experiments from lung fibroblasts established from 5 mice/group. Error bars, S.E.

Versican Significantly Enhances Monocyte Chemotaxis

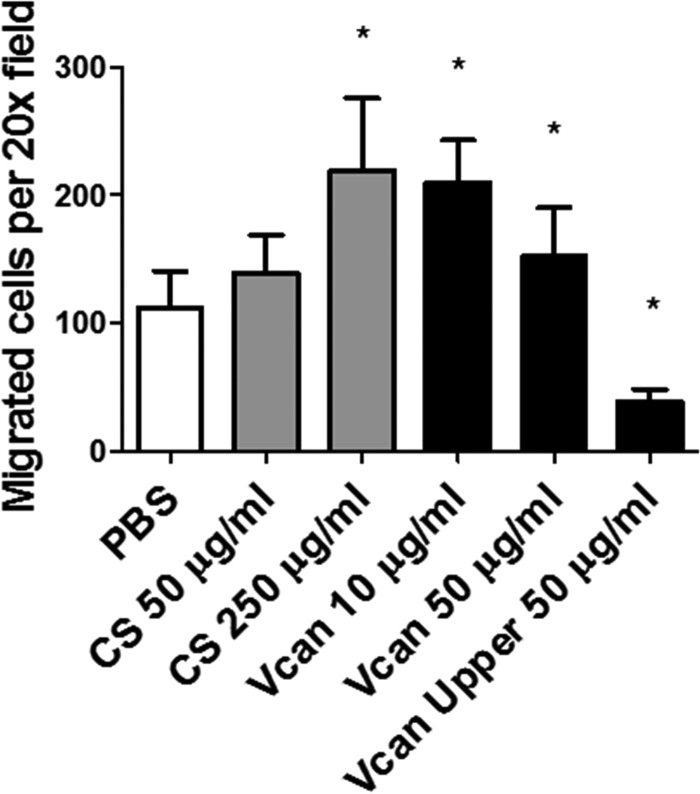

To determine whether versican has an impact on leukocyte chemotaxis, we tested chemotactic migration of monocytic U937 cells toward CCL2 in the presence or absence of versican or CS chains. The addition of purified exogenous versican to the bottom chamber, along with CCL2, significantly enhanced migration of monocytic cells toward the chemokine (Fig. 9). Similarly, the addition of CS enhanced chemotaxis in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, adding the purified versican to the monocytic cells in the filter well on the top chamber abolished this chemotactic migration, indicating that the interaction between the chemokine and versican, potentially via CS side chains, enhances leukocyte chemotaxis.

FIGURE 9.

Chemotactic migration of monocytic cells in vitro. The addition of purified chondroitin sulfate chains or purified versican protein to the chemokine Ccl2 in the bottom chamber significantly enhanced chemotactic migration of monocytic cells, whereas adding versican to the upper chamber significantly reduced the migration. *, p < 0.05. Results are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars, S.D.

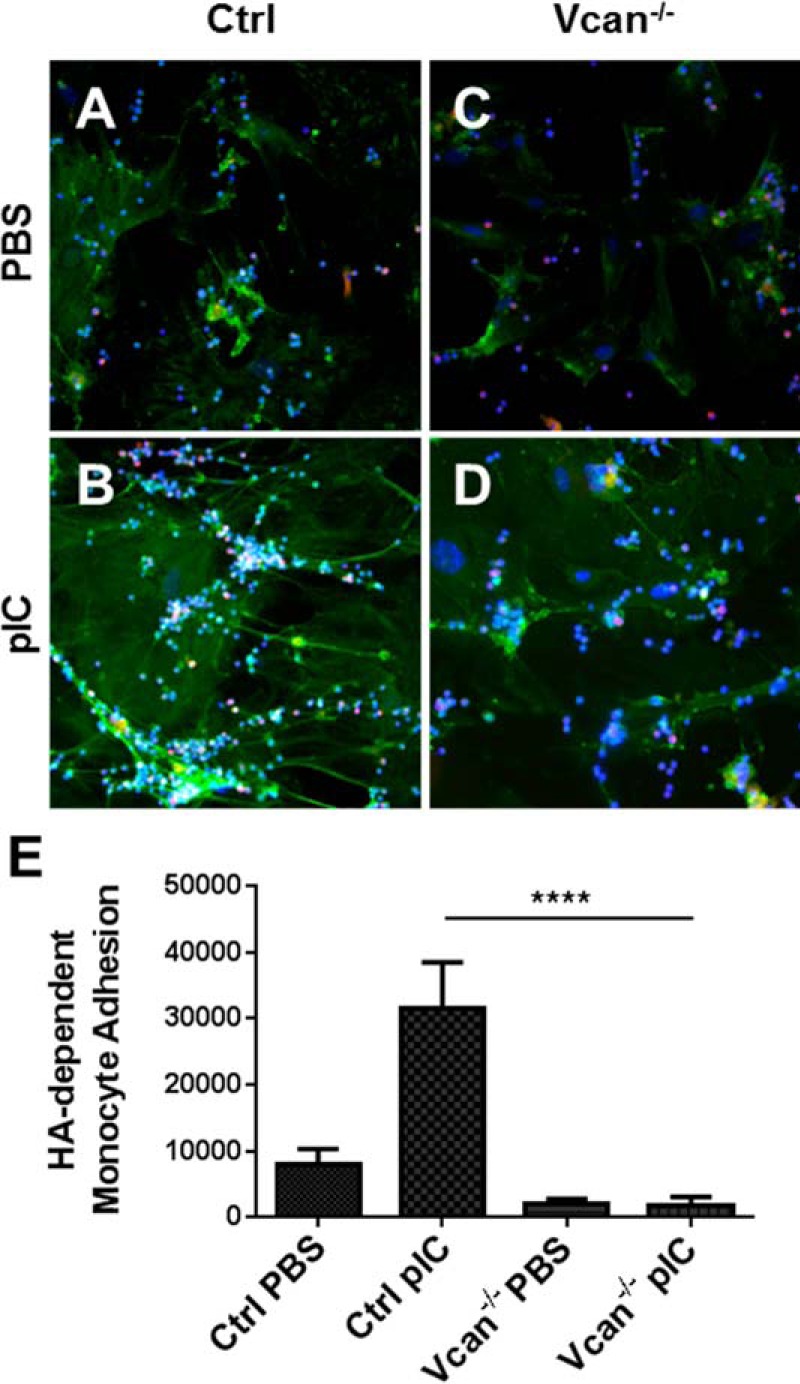

Poly(I:C)-induced HA Cable Formation and HA-dependent Monocyte Adhesion was Significantly Reduced in Cultures of Lung Fibroblasts from Vcan−/− Mice

Because we observed a relationship between HA, versican, and leukocyte accumulation in poly(I:C)-treated mouse lungs, we examined the formation of HA cables induced by poly(I:C) stimulation of lung fibroblasts in vitro, which promote leukocyte adhesion, as we have previously shown (30–32, 34). As anticipated, lung fibroblasts isolated from control animals generated HA cable structures in response to poly(I:C) (supplemental Fig. 4A). On the other hand, lung fibroblasts isolated from Vcan−/− animals did not generate these HA cable structures (supplemental Fig. 4B), suggesting that versican deficiency disrupts HA cable formation. We found that poly(I:C) treatment of control lung fibroblasts in cultures induces formation of HA cables, which allows U937 monocytic cells to adhere (Fig. 10, A and B). In contrast, fibroblasts from Vcan−/− mice showed a reduction in HA cable formation and associated adherent monocytes (Fig. 10, C and D). Control lung fibroblasts exhibited HA-dependent monocyte adhesion in response to poly(I:C), which was not present in fibroblasts from Vcan−/− mice (Fig. 10E). These findings demonstrate that versican deficiency blocks accumulation of HA cable structures that facilitate leukocyte accumulation. Thus, versican probably plays dual roles of both attracting and retaining leukocytes at sites of inflammation.

FIGURE 10.

HA-dependent monocyte adhesion to cultured lung fibroblasts in response to poly(I:C) (pIC) treatment. In both control (Ctrl) (A) and Vcan−/− (C) lung fibroblasts treated with PBS, immunohistochemistry shows little HA cable formation (HABP; green) with minimal monocyte (CD68; red) binding. Images are representative of two independent experiments. In contrast, panel B shows monocytes (CD68; red) accumulated along HA cables (HABP; green) induced by pIC in Ctrl lung fibroblasts (nuclei; DAPI; blue), whereas monocyte accumulation along HA cables was diminished in pIC-stimulated Vcan−/− lung fibroblasts (D), as quantified by a monocyte adhesion assay, which measures HA-dependent adhesion (E). **, p < 0.01. Error bars, S.E.

Discussion

In this study, we developed an inducible versican-deficient mouse strain and used this mouse model to demonstrate that versican is a critical extracellular mediator of poly(I:C)-induced acute lung and airway inflammation. In inflamed lungs, versican and HA increased throughout, but particularly at sites of leukocyte accumulation. Previous work has shown that HA accumulation in the ECM at sites of inflammation is mediated by HA-binding molecules, such as versican, inter-α-trypsin inhibitor (IαI), and tumor necrosis factor α-stimulated gene 6 (TSG-6), which cross-links HA into cable-like structures that provide a substrate for leukocyte adhesion (24, 31, 32, 36–38). Specifically, our in vitro work has demonstrated that HA-dependent monocyte binding to poly(I:C)-stimulated lung fibroblasts can be abolished by blocking antibodies against the HA-binding region of versican (32). In the present study, versican deficiency resulted in reduced Has2 expression and HA accumulation in lung tissue coupled with reduced total cell counts in BALF and an overall dampened inflammatory cytokine expression profile. These findings in an in vivo model of lung inflammation confirm that versican is critical to generating a specialized HA-enriched ECM that binds leukocytes.

The development of a conditionally versican-deficient mouse strain has been pivotal to further study the role of versican in inflammation in vivo. Total gene disruption preventing versican production (35) or production of mutant versican missing exon 3 (39) causes heart development defects that result in embryonic or neonatal lethality in homozygous animals. Recently, a mouse strain with floxed versican exon 2 (Vcan e2fl/fl) was generated by Watanabe and colleagues who used it to demonstrate the importance of versican in joint development and TGF-β-dependent chondrocyte differentiation (40) and, more recently, and in cancer progression (41). In our study, we have taken advantage of the Rosa26 CreERT2 strain to drive deletion of all isoforms of versican in response to tamoxifen treatment in all tissues of juvenile mice, thus bypassing the indispensable need for versican during development but allowing for investigation of versican in post-natal pathologies. Additional tissue-specific Cre strains are being used to further explore the role of versican in specific cell types during inflammation, such as leukocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells.

Versican also increases in a number of human lung and airway diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (42–45). A significant increase in versican accumulation occurs in the interstitial space of small and large airways of patients with asthma (11–13, 15, 46) and in animal models of asthma (17, 18). Cells isolated from diseased lungs also exhibit altered versican production. For example, bronchial fibroblasts cultured from human asthma patients exhibited elevated versican production (20, 21). Furthermore, in a study of induced sputum from patients with severe asthma, we found elevated levels of versican and HA over a 16-week period, which inversely correlated with lung forced expiratory volume (47). These observations, along with the present findings from our experimental animal model of airway inflammation induced by viral mimetics, suggest that versican may be an active driver of the inflammatory process in a variety of human lung diseases with disparate pathogeneses.

In the present study, poly(I:C) was used as a stimulant to elicit lung inflammation. Induction of immune responses by respiratory viruses involves pattern recognition receptors, such as TLRs (48). In particular, TLR3 recognizes dsRNA produced during viral infections as well as poly(I:C), a synthetic ligand mimicking viral dsRNA. This recognition induces activation of NF-κB and the production of type 1 interferons that further regulate inflammatory and antiviral mediator expression (49). Previous in vitro studies demonstrated that stimulation of lung fibroblasts with poly(I:C) or other NF-κB agonists induces synthesis and accumulation of an HA-enriched ECM serving as a substrate for leukocyte accumulation, including monocytes and T lymphocytes (30, 32, 50–52). In in vivo studies, poly(I:C) has been used to elicit acute lung inflammation and further exacerbate pulmonary allergic reactions (28, 29), which is probably mediated by generating versican-enriched ECM attracting leukocyte accumulation in the inflamed airways, as our data suggest. Further studies are ongoing to elucidate roles of versican in viral exacerbation of asthma.

The binding of chemokines to GAGs is critical for chemotactic activities (42, 43), first for the generation of solid phase gradients of chemokines in the ECM and, second, for the regulation of chemokine activity achieved by interacting with GAGs on cell surface receptors. Our findings demonstrate that versican interacts with chemokine CCL2, probably via its CS chains, generating a chemotactic gradient that promotes monocyte migration, whereas versican allowed to interact with monocytes before chemokine exposure appears to compete for CCL2 binding to cell surface receptors. Recent studies showed that mutant CCL2 with high affinity for GAG binding interferes with wild type CCL2 binding to CCR2, acting as a potent decoy against the CCL2-CCR2 chemokine axis (44, 45). These findings and our data suggest that versican as a CS PG may provide a fine tuned control mechanism for chemotactic migration of leukocytes.

Interestingly, versican-deficient lung fibroblasts exhibited attenuated expression of IL1β induced by poly(I:C) in vitro. This suggests that versican is critical not only in generating a HA-enriched ECM that attracts leukocyte accumulation in response to inflammatory stimuli, but also in activating signaling pathways involved in IL1β expression. IL1β gene expression downstream of NF-κB and TLR signaling is a critical priming step in NLRP3 (NACHT, LRR, and PYD domain-containing protein 3) inflammasome-mediated IL1β activation and secretion (53). Because other ECM molecules, such as biglycan, have been shown to regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation (54), we questioned whether versican was able to regulate this pathway in our poly(I:C)-induced lung inflammation model as well. However, levels of secreted IL1β were below detectable limits in the BALF as well as the conditioned media from primary lung fibroblasts stimulated with poly(I:C). Furthermore, no mRNA for either NLRP3 or the inflammasome adaptor protein ASC was detected in the poly(I:C)-stimulated whole lung tissue, which strongly suggests that NLRP3 inflammasome activation was not elicited under the conditions used in our experiments. This is in contrast to findings by Allen et al. (55), who detected low amounts (∼10 pg/ml) of secreted IL1β using another model of poly(I:C)- and influenza virus-induced lung inflammation in mice. This is probably due to methodological differences in our respective approaches. More work is needed to resolve this interesting question.

Several studies indicate that versican is a DAMP (danger-associated molecular pattern) molecule that interacts with TLRs, such as TLR2, to promote production of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα (56–64). Similarly, other CS PG ECM molecules, such as biglycan, activate TLR2 and TLR4 via CS chains and core protein, exacerbating acute kidney injury (54, 65, 66). Whether CS chains or versican core proteins are involved in directly activating TLR3 or indirectly via binding to TLR2 or other molecules associating with TLR, such as CD14, is not yet clear.

Whether versican induces cytokine expression by stimulating Has2-dependent HA production in response to poly(I:C) is not yet clear. Previously, our studies have demonstrated that removing CS-bearing versican, by expressing V3 (the isoform of versican that naturally lacks CS chains), prevents formation of HA-enriched ECM by blocking activation of EGFR and downstream NF-κB (34). Versican signals directly through TLRs to stimulate the NF-κB-dependent expression of inflammatory cytokines (56–64). V0/V1 versican, via CS chains, can also directly interact with CD44 (67), which can form a signaling complex with EGFR2 as well as ezrin and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) to up-regulate HA synthesis (68–72). Moreover, HA synthases have NF-κB binding regions in their promoters and are up-regulated by NF-κB agonists (50–52, 73). Overall, these findings suggest that versican may activate TLR-NF-κB and/or CD44-EGFR signaling, increasing HA production via Has2, which promotes leukocyte accumulation and helps sustain the inflammatory state. Because HA is also capable of triggering TLR- and CD44- signaling pathways, it is likely that the HA-versican complex may potentiate the binding of the molecules to the cell surface receptors in a synergistic way. Further investigation is currently ongoing in our laboratory to elucidate the impact of the HA-versican complex on downstream signaling pathways involved in immunomodulation.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that loss of versican has a direct impact on airway inflammation by reducing leukocyte accumulation associated with HA-enriched ECM and by attenuating proinflammatory cytokine expression induced by TLR activation. Our findings demonstrate that versican is a critical player in lung inflammation and may be a novel therapeutic target for treating acute lung inflammation.

Experimental Procedures

B6.Vcan e4fl/fl Construction

A mouse versican bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone AC134397 was obtained from the Whitehead Institute/MIT Center for Genome Research. Vector 4600C2,6, with cassettes for pgaDTA, HSVTK, and svNEO flanked by frt sites and a LoxP site at the 5′ end, was provided by Dr. Richard Palmiter (University of Washington). The 3′ arm was cloned by PCR from the AC134397 BAC, producing a 4.269-kb fragment encoding bp 40,242–44,511 with added 5′ XhoI and 3′ AflII sites. This fragment was cloned into TOPOXL and sequenced. After restriction digests with XhoI and AflII, the 3′ arm was ligated into compatible sites of the vector 4600C2,6.

The 5′ arm was generated by PCR amplification of the region encoding bp 35,611–40,261 of AC134397 with added 5′ MfeI and 3′ SalI sites, which was then cloned into TOPOXL and sequenced. A unique PpuMI site 1147 bp from the start of exon 4 was used to insert a matching LoxP site. The clone was resequenced and ligated into the vector 4600C2,6, which was digested with SalI and MfeI. This vector was then linearized and used for electroporation of C57/Bl6 embryonic stem cells (ESCs), which was performed by the University of Washington Transgenic Resources Program. ESC clones were screened by PCR, and recombination was identified by Southern blot analysis. ESCs were injected into Bl6 mouse blastocysts, and chimeras were obtained. Germ line transmission of intact mutation was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Generation of a Mouse Strain with a Tamoxifen-inducible Ubiquitous Deletion of Versican

We bred a mouse strain with floxed versican exon 4 (B6.Vcan e4fl/fl), which generates versican null alleles upon Cre recombinase-mediated deletion of exon 4, with a strain with tamoxifen-inducible Rosa26-driven Cre-recombinase expression (B6.129-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(cre/ERT2)Tyj/J, strain 008463; Jackson Laboratories) to create mice with an inducible global versican deficiency in the C57BL/6 background (B6.Vcan e4fl/fl:Rosa26-CreERT2).

Tamoxifen Injections

0.1 g of tamoxifen-free base (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. T5648) was dissolved in 0.5 ml of 100% ethanol, and 9.5 ml of sterile corn oil was added. The mixture was vortexed and then sonicated until completely dissolved and stored in aliquots at −20 °C. 0.1 ml of this solution (1 mg of tamoxifen) was injected intraperitoneally into mice at 6–7 weeks of age, each day for 5 days. For controls, B6.Vcan e4fl/fl mice lacking Rosa26-CreERT2 were used. To provide time for adequate versican turnover and ensure versican deficiency in lung tissues, experiments were conducted at 10–12 weeks of age.

Monitoring Vcan Exon 4 Floxing

The efficacy of Vcan floxed allele deletion was monitored in liver and lung tissue samples 4 weeks after the tamoxifen injections in control mice homozygous for floxed versican alleles and in experimental mice either hemizygous or homozygous for the Cre-recombinase. Briefly, genomic DNA was isolated using the REDExtract-N-Amp tissue PCR kit (Sigma-Aldrich), and regions around the Vcan exon 4 were amplified by PCR (forward, CAGCCTGAGCAACAGGGCACC; reverse, CCCTCTCGGGGAGCCCGTATG), using the KAPA2G HotStart ReadyMix PCR kit (KAPA Biosystems).

Preparation of Poly(I:C)

Poly(I:C), purchased from Invivogen, was prepared as directed by the manufacturer. Briefly, endotoxin-free water provided by the manufacturer was added to poly(I:C) at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml, incubated in a hot water bath (65–70 °C) for 10 min, and allowed to cool slowly to room temperature to ensure proper annealing. Poly(I:C) solution was then aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until use. Before use, poly(I:C) solution was vortexed and triturated to ensure thorough mixing.

Oropharyngeal Instillation of Poly(I:C) into Mice

Mice were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane, and 50 μg of poly(I:C) was administered into the back of the throat using a sterile pipette while the tongue was immobilized with padded forceps to prevent swallowing and ensure inhalation. Mice were given poly(I:C) on day 0 and day 1 and were sacrificed at day 3.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Collection

Animals deeply anesthetized by i.p. injection of tribromoethanol (500 mg/kg) were sacrificed by cardiac exsanguination. Bronchoalveolar lavage was carried out by administering 4 × 1 ml of PBS via the trachea into both lungs until fully inflated and then collecting the fluid (BALF). The first fraction of BALF was saved separately from the additional three fractions. BALF yields from this first fraction varied by treatment, with PBS-treated lungs achieving 750 μl, whereas poly(I:C) administration reduced the yield to 650 μl. No difference was observed between genotypes. After collecting BALF, the lungs were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for DNA, RNA, and protein purification. The BALF was spun at 250 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants from the first fraction of BALF were stored at −80 °C until analysis. The pelleted cells from the first fraction were pooled with the cells from the rest of the BALF and incubated in red blood cell lysis buffer (Roche Applied Science) for 1 min, followed by neutralization with an equal volume of RPMI medium. The cells were washed and divided into two aliquots; the first was used for flow cytometry analysis, and the second was used for counting total cell numbers using a hemocytometer.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of BALF Cells

Single cell suspensions for determination of differential cell counts in the BALF were prepared as follows. To prevent nonspecific binding of antibodies, cells were incubated with Fc blocker (1:100; anti-mouse CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2), Pharmingen/BD Biosciences), in PBS plus 0.5% BSA for 15 min at room temperature. Cell surface antigens were detected by incubating with antibodies against CD45(Ly5) (FITC (1:200), eBioscience), Ly6G/GR1 (PerCP.Cy5 or Pacific Blue (1:400), eBioscience), CD3e (BV605 (1:400), Biolegend), CD19 (BV655 (1:400), Biolegend), CD11b (FITC (1:200) or APC (1:400), eBioscience), MHC II (Alexa Fluor 700 (1:400), eBioscience), Siglec F (PE (1:400), BD Bioscience), CD11c (PE.Cy7 (1:400), eBioscience), and F4/80 (APC or PerCPCy5.5 (1:400), Biolegend) at 4 °C in the dark for 20 min. Cells were then washed in PBS plus 0.5% BSA and fixed in 10% formalin at 4 °C for 10 min, washed in PBS plus 0.5% BSA again, and stored overnight until analysis. Analysis was performed using an LSRII (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. Gating was performed as described previously (74). Because >99% of live cells were CD45-positive in initial experiments, that antibody was omitted in later analyses.

Lung Tissue Processing for Histology

Lungs from animals used for histology and immunostaining analysis were inflation-fixed by intratracheally administering 1 ml of 10% formalin to fully inflate the lungs before removal from the chest cavity. Tissues were then fixed overnight in additional formalin. Formalin-fixed lung tissues were embedded in paraffin such that each section contained regions from all four lobes of the right lung. Lung tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and versican antibody (β-GAG region of versican; EMD Millipore) and HA-binding protein. For versican immunostaining, tissue sections were pretreated with 0.2 units/ml chondroitinase ABC (Sigma) in buffer at pH 8.0 containing 18 mm Tris, 1 mm sodium acetate, and 1 mg/ml BSA for 1 h at 37 °C. After digestion, the sections were incubated for 1 h with 2.5 μg/ml rabbit anti-mouse versican β-GAG domain (Millipore) in Bond antibody diluent, and detection was performed using the Bond polymer Refine Detection Kit containing a peroxidase block, a ready-to-use secondary goat anti-rabbit conjugated to polymeric HRP, DAB chromagen, and hematoxylin counterstain (Leica Microsystems). Stained tissue sections were imaged by a Leica DMR microscope and Diagnostic Instruments Pursuit 4.0-megapixel CCD camera and Spot software.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative PCR

Lung tissues were homogenized in TRIzol (1 ml) in tubes prefilled with 1.5-mm zirconium beads for 1 min in a BeadBug microtube homogenizer (Benchmark Scientific), followed by the addition of chloroform (0.2 ml) and vigorous mixing by hand. For lung fibroblasts, cells were lysed in 0.5 ml of TRIzol, followed by the addition of 0.1 ml of chloroform and vigorous mixing. The solution was incubated at room temperature for 5 min and spun at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The aqueous phase was collected, mixed with an equal volume of 70% ethanol, and purified using EconoSpinTM columns (Epoch Life Science). cDNA was prepared from the isolated RNA with a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR was carried out with SYBR Select Master Mix or TaqMan® Gene Expression Master Mix (Life Technologies), as directed by the manufacturer, on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT fast real-time PCR system. For each sample, assays were run as technical duplicates. cDNA levels were then expressed as estimated copy numbers of mRNA using the master-template approach (75). Taqman probes (Life Technologies) were pan-Vcan (Mm01283063_m1), V1 (Mm00490173_m1), V3 (Rn01493763_m1), Has1 (Mm00468496_m1), Has2 (Mm00515089_m1), Has3 (Mm00515092_m1), TNFα (Mm00443258_m1), and 18S rRNA (4319413E-1403063). Gene-specific SYBR primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Western Blotting

Protein homogenates were prepared by extracting finely minced tissues with 4 m GuHCl buffer (4 m guanidine HCl, 100 mm sodium sulfate, 100 mm Tris base, 2.5 mm Na2EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.0) with protease inhibitors (5 mm benzamidine hydrochloride, 100 mm 6-aminohexanoic acid, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) overnight at 4 °C. Tissue extracts were then dialyzed against 8 m urea buffer (8 m urea, 2 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris base, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.5) to remove the guanidine. Protein concentration was determined by using a Coomassie protein assay kit (Pierce). For Western blotting, equal amounts of protein were isolated by DEAE-Sephacel chromatography (76). Equal volumes of isolated proteoglycans were ethanol-precipitated, digested with chondroitin ABC lyase, and electrophoresed on 4–12% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gels with 3.5% stacking gel. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose, probed with antibody against the β-GAG region of versican (0.25 μg/ml; Millipore). Results were visualized using a LI-COR Odyssey® scanner and software (LI-COR Biotechnology). Densitometry was performed using ImageJ 1.47t (National Institutes of Health) and included all bands >250 kDa to capture V0 and V1 isoforms as well as their large degradation products.

Lung Fibroblast Isolation from Mice

Tamoxifen-injected control (B6:Vcan-e4fl/fl) or Vcan−/− (B6:Vcan-e4fl/fl:Rosa26-CreERT2) mice at 10–12 weeks of age were deeply anesthetized with i.p. injection of tribromoethanol (500 mg/kg) and sacrificed by cardiac exsanguination. Lung fibroblasts were explanted from the minced lung tissues dissected from the animals in DMEM culture medium supplemented with 20% FBS, GlutaMAX, sodium pyruvate, penicillin/streptomycin, and antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific). All cells were used up to passage 4.

Poly(I:C) Stimulation of Lung Fibroblasts

Isolated lung fibroblasts from control or Vcan−/− mice were plated on tissue culture plates at 2.0 × 104/cm2 density for 24 h, growth-arrested in low serum culture medium supplemented with 0.1% FBS for 48 h, and treated with or without 40 μg/ml poly(I:C) in culture medium containing 10% FBS for 24 h.

Immunofluorescence Staining of Lung Fibroblasts

Control or Vcan−/− lung fibroblasts were stimulated with 20 μg/ml poly(I:C) and cultured with or without monocytic cells as described above. These cells were fixed with 10% formalin, 70% ethanol, and 5% acetic acid for 10 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and incubated in blocking buffer (2% BSA, 2% normal donkey serum in PBS), before staining for the monocyte marker CD68 (1:100 dilution, mouse monoclonal KP-1 antibody against human CD68, Abcam) and biotinylated HA-binding protein (2.5 μg/ml) followed by donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 546 and streptavidin Alexa Fluor 488 in PBS containing 1% BSA. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images were acquired and merged on a Leica DMIRB inverted microscope equipped with fluorescent epi-illumination, using a Diagnostic Instruments Pursuit 4.0-megapixel chilled color CCD camera and Spot software, version 4.5.9.1.

Monocyte Adhesion Assay

Quantification of monocyte adhesion to control and Vcan−/− lung fibroblasts was performed as described previously (24, 32) with some modifications. Lung fibroblasts were stimulated with poly(I:C) as described above. Some cells were treated with Streptomyces hyaluronidase (1 unit/ml; Seikagaku) at 37 °C for 30 min before adding monocytes, to determine the role of HA in monocyte binding. The human monocytic cells, U937 (ATCC), labeled with 5 μg/ml Calcein AM (Invitrogen), were added to lung fibroblasts and allowed to bind for 90 min at 4 °C. Non-bound monocytic cells were removed by washing with cold RPMI medium. Monocyte binding was measured by exciting the fluorophore at 485 nm and reading absorbance at 530 nm using a Fusion series universal microplate analyzer (Packard Bioscience Co.) (32).

Monocyte Chemotaxis Assay

As adapted from Masuda et al. (77), the bottom wells of a 24-well transwell assay system (8-μm pore size; Greiner Bio-One) were coated overnight with 200 μl of PBS alone or containing various concentrations of CS (Sigma; CSA, C8529), purified bovine versican, or HA. In some experiments, the upper membrane surface of the transwell insert was also coated with versican. The following day, the wells were rinsed with PBS and incubated with CCL2 (Invitrogen; 50 ng/ml in RPMI) for 2 h. U937 cells (3 × 105 cells in RPMI, no serum) were added to the upper well and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Cells were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin, stained with crystal violet (0.5% in water). Cells were wiped off of the upper membrane surface with a cotton swab, and the migrated cells on the underside or in the pores were counted.

Statistical Analyses

All data are expressed as the average ± S.E., unless otherwise specified. Differences were identified by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc tests for the comparison of three or more groups and were regarded as significant if p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

I. K. and I. A. H. designed and conducted experiments and wrote the paper. M. Y. C. provided technical assistance and contributed to the design of the study and the preparation of the manuscript. K. R. B., M. G. K., and C. W. F. contributed to the conception and design of the conditional versican-deficient mouse strain, conducted experiments, and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. A. S., M. P. N., P. Y. J., G. W., G. K., S. P. E., and C. K. C. provided technical assistance and conducted experiments. M. J. M. provided technical assistance and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. S. F. Z. coordinated the study and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. T. N. W. conceived, designed, and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard D. Palmiter (Howard Hughes Medical Institute and University of Washington) and Robert J. Hunter (University of Washington) for expert guidance in the development of Vcan e4fl/fl mice and Dr. Virginia M. Green for careful reading and editing of the manuscript. National Institutes of Health Grant P30 DK17047 (University of Washington Diabetes Research Center) provided Core support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P01 HL098067 (to S. F. Z., C. W. F., and T. N. W.), R01 AI068731 and U19 AI125378 (to S. F. Z.), and R21 RR030249 (to C. W. F) and the University of Auckland Faculty Development Fund (to M. J. M.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–4 and Table 1.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- HA

- hyaluronan

- CS

- chondroitin sulfate

- PG

- proteoglycan

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- poly(I:C)

- polyinosine-polycytidylic acid

- Vcan

- versican

- Vcan−/−

- versican-deficient

- Has

- hyaluronan synthase

- GAG

- glycosaminoglycan

- BALF

- broncoalveolar lavage fluid

- BAC

- bacterial artificial chromosome

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell.

References

- 1. Shibata T., Habiel D. M., Coelho A. L., Kunkel S. L., Lukacs N. W., and Hogaboam C. M. (2014) Axl receptor blockade ameliorates pulmonary pathology resulting from primary viral infection and viral exacerbation of asthma. J. Immunol. 192, 3569–3581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tan W. C. (2005) Viruses in asthma exacerbations. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 11, 21–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saraya T., Kurai D., Ishii H., Ito A., Sasaki Y., Niwa S., Kiyota N., Tsukagoshi H., Kozawa K., Goto H., and Takizawa H. (2014) Epidemiology of virus-induced asthma exacerbations: with special reference to the role of human rhinovirus. Front. Microbiol. 5, 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kurai D., Saraya T., Ishii H., and Takizawa H. (2013) Virus-induced exacerbations in asthma and COPD. Front. Microbiol. 4, 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Papadopoulos N. G., Christodoulou I., Rohde G., Agache I., Almqvist C., Bruno A., Bonini S., Bont L., Bossios A., Bousquet J., Braido F., Brusselle G., Canonica G. W., Carlsen K. H., Chanez P., et al. (2011) Viruses and bacteria in acute asthma exacerbations–a GA(2) LEN-DARE systematic review. Allergy 66, 458–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clarke D. L., Davis N. H., Majithiya J. B., Piper S. C., Lewis A., Sleeman M. A., Corkill D. J., and May R. D. (2014) Development of a mouse model mimicking key aspects of a viral asthma exacerbation. Clin. Sci. 126, 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shannon J. M., McCormick-Shannon K., Burhans M. S., Shangguan X., Srivastava K., and Hyatt B. A. (2003) Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans are required for lung growth and morphogenesis in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 285, L1323–L1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Faggian J., Fosang A. J., Zieba M., Wallace M. J., and Hooper S. B. (2007) Changes in versican and chondroitin sulphate proteoglycans during structural development of the lung. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293, R784–R792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Snyder J. M., Washington I. M., Birkland T., Chang M. Y., and Frevert C. W. (2015) Correlation of versican expression, accumulation, and degradation during embryonic development by quantitative immunohistochemistry. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 63, 952–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnson P. R. (2001) Role of human airway smooth muscle in altered extracellular matrix production in asthma. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 28, 233–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roberts C. R. (1995) Is asthma a fibrotic disease? Chest 107, 111S–117S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang J., Olivenstein R., Taha R., Hamid Q., and Ludwig M. (1999) Enhanced proteoglycan deposition in the airway wall of atopic asthmatics. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 160, 725–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Medeiros Matsushita M., da Silva L. F., dos Santos M. A., Fernezlian S., Schrumpf J. A., Roughley P., Hiemstra P. S., Saldiva P. H., Mauad T., and Dolhnikoff M. (2005) Airway proteoglycans are differentially altered in fatal asthma. J. Pathol. 207, 102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Westergren-Thorsson G., Chakir J., Lafrenière-Allard M. J., Boulet L. P., and Tremblay G. M. (2002) Correlation between airway responsiveness and proteoglycan production by bronchial fibroblasts from normal and asthmatic subjects. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34, 1256–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weitoft M., Andersson C., Andersson-Sjöland A., Tufvesson E., Bjermer L., Erjefält J., and Westergren-Thorsson G. (2014) Controlled and uncontrolled asthma display distinct alveolar tissue matrix compositions. Respir. Res. 15, 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Andersson-Sjöland A., Hallgren O., Rolandsson S., Weitoft M., Tykesson E., Larsson-Callerfelt A. K., Rydell-Törmänen K., Bjermer L., Malmström A., Karlsson J. C., and Westergren-Thorsson G. (2015) Versican in inflammation and tissue remodeling: the impact on lung disorders. Glycobiology 25, 243–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu Z., Ma B., Zheng T., Homer R. J., Lee C. G., Charo I. F., Noble P., and Elias J. A. (2002) IL-13-induced chemokine responses in the lung: role of CCR2 in the pathogenesis of IL-13-induced inflammation and remodeling. J. Immunol. 168, 2953–2962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lowry M. H., McAllister B. P., Jean J. C., Brown L. A., Hughey R. P., Cruikshank W. W., Amar S., Lucey E. C., Braun K., Johnson P., Wight T. N., and Joyce-Brady M. (2008) Lung lining fluid glutathione attenuates IL-13-induced asthma. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 38, 509–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chang M. Y., Tanino Y., Vidova V., Kinsella M. G., Chan C. K., Johnson P. Y., Wight T. N., and Frevert C. W. (2014) A rapid increase in macrophage-derived versican and hyaluronan in infectious lung disease. Matrix Biol. 34, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malmström J., Larsen K., Hansson L., Löfdahl C. G., Nörregard-Jensen O., Marko-Varga G., and Westergren-Thorsson G. (2002) Proteoglycan and proteome profiling of central human pulmonary fibrotic tissue utilizing miniaturized sample preparation: a feasibility study. Proteomics 2, 394–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ludwig M. S., Ftouhi-Paquin N., Huang W., Pagé N., Chakir J., and Hamid Q. (2004) Mechanical strain enhances proteoglycan message in fibroblasts from asthmatic subjects. Clin. Exp. Allergy 34, 926–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reeves S. R., Kaber G., Sheih A., Cheng G., Aronica M. A., Merrilees M. J., Debley J. S., Frevert C. W., Ziegler S. F., and Wight T. N. (2016) Subepithelial accumulation of versican in a cockroach antigen-induced murine model of allerigic asthma. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 64, 364–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de la Motte C., Hascall V. C., Drazba J. A., and Strong S. A. (2002) Poly I:C induces mononuclear leukocyte-adhesive hyaluronan structures on colon smooth muscle cells: IaI and versican facilitate adhesion. in Hyaluronan: Chemical, Biochemical and Biological Aspects (Kennedy J. F., Phillips G. O., Williams P. A., and Hascall V. C., eds) pp. 381–388, Woodhead Publishing Ltd., Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- 24. de la Motte C. A., Hascall V. C., Drazba J., Bandyopadhyay S. K., and Strong S. A. (2003) Mononuclear leukocytes bind to specific hyaluronan structures on colon mucosal smooth muscle cells treated with polyinosinic acid:polycytidylic acid: inter-α-trypsin inhibitor is crucial to structure and function. Am. J. Pathol. 163, 121–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lauer M. E., Fulop C., Mukhopadhyay D., Comhair S., Erzurum S. C., and Hascall V. C. (2009) Airway smooth muscle cells synthesize hyaluronan cable structures independent of inter-α-inhibitor heavy chain attachment. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5313–5323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lauer M. E., Mukhopadhyay D., Fulop C., de la Motte C. A., Majors A. K., and Hascall V. C. (2009) Primary murine airway smooth muscle cells exposed to poly(I,C) or tunicamycin synthesize a leukocyte-adhesive hyaluronan matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5299–5312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang A., and Hascall V. C. (2004) Hyaluronan structures synthesized by rat mesangial cells in response to hyperglycemia induce monocyte adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10279–10285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Torres D., Dieudonné A., Ryffel B., Vilain E., Si-Tahar M., Pichavant M., Lassalle P., Trottein F., and Gosset P. (2010) Double-stranded RNA exacerbates pulmonary allergic reaction through TLR3: implication of airway epithelium and dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 185, 451–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stowell N. C., Seideman J., Raymond H. A., Smalley K. A., Lamb R. J., Egenolf D. D., Bugelski P. J., Murray L. A., Marsters P. A., Bunting R. A., Flavell R. A., Alexopoulou L., San Mateo L. R., Griswold D. E., Sarisky R. T., et al. (2009) Long-term activation of TLR3 by poly(I:C) induces inflammation and impairs lung function in mice. Respir. Res. 10, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Evanko S. P., Potter-Perigo S., Bollyky P. L., Nepom G. T., and Wight T. N. (2012) Hyaluronan and versican in the control of human T-lymphocyte adhesion and migration. Matrix Biol. 31, 90–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Evanko S. P., Potter-Perigo S., Johnson P. Y., and Wight T. N. (2009) Organization of hyaluronan and versican in the extracellular matrix of human fibroblasts treated with the viral mimetic poly I:C. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 57, 1041–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Potter-Perigo S., Johnson P. Y., Evanko S. P., Chan C. K., Braun K. R., Wilkinson T. S., Altman L. C., and Wight T. N. (2010) Polyinosine-polycytidylic acid stimulates versican accumulation in the extracellular matrix promoting monocyte adhesion. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 43, 109–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wight T. N., Kang I., and Merrilees M. J. (2014) Versican and the control of inflammation. Matrix Biol. 35, 152–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kang I., Yoon D. W., Braun K. R., and Wight T. N. (2014) Expression of versican V3 by arterial smooth muscle cells alters TGFβ-, EGF-, and NFκB-dependent signaling pathways, creating a microenvironment that resists monocyte adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 15393–15404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mjaatvedt C. H., Yamamura H., Capehart A. A., Turner D., and Markwald R. R. (1998) The Cspg2 gene, disrupted in the hdf mutant, is required for right cardiac chamber and endocardial cushion formation. Dev. Biol. 202, 56–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Selbi W., de la Motte C. A., Hascall V. C., Day A. J., Bowen T., and Phillips A. O. (2006) Characterization of hyaluronan cable structure and function in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 70, 1287–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jokela T. A., Lindgren A., Rilla K., Maytin E., Hascall V. C., Tammi R. H., and Tammi M. I. (2008) Induction of hyaluronan cables and monocyte adherence in epidermal keratinocytes. Connect. Tissue Res. 49, 115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lauer M. E., Cheng G., Swaidani S., Aronica M. A., Weigel P. H., and Hascall V. C. (2013) Tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 (TSG-6) amplifies hyaluronan synthesis by airway smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 423–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hatano S., Kimata K., Hiraiwa N., Kusakabe M., Isogai Z., Adachi E., Shinomura T., and Watanabe H. (2012) Versican/PG-M is essential for ventricular septal formation subsequent to cardiac atrioventricular cushion development. Glycobiology 22, 1268–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Choocheep K., Hatano S., Takagi H., Watanabe H., Kimata K., Kongtawelert P., and Watanabe H. (2010) Versican facilitates chondrocyte differentiation and regulates joint morphogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21114–21125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fanhchaksai K., Okada F., Nagai N., Pothacharoen P., Kongtawelert P., Hatano S., Makino S., Nakamura T., and Watanabe H. (2016) Host stromal versican is essential for cancer-associated fibroblast function to inhibit cancer growth. Int. J. Cancer 138, 630–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Merrilees M. J., Ching P. S. T., Beaumont B., Hinek A., Wight T. N., and Black P. N. (2008) Changes in elastin, elastin binding protein and versican in alveoli in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Res. 9, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bensadoun E. S., Burke A. K., Hogg J. C., and Roberts C. R. (1996) Proteoglycan deposition in pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 154, 1819–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Merrilees M. J., Hankin E. J., Black J. L., and Beaumont B. (2004) Matrix proteoglycans and remodelling of interstitial lung tissue in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J. Pathol. 203, 653–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morales M. M., Pires-Neto R. C., Inforsato N., Lanças T., da Silva L. F., Saldiva P. H., Mauad T., Carvalho C. R., Amato M. B., and Dolhnikoff M. (2011) Small airway remodeling in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a study in autopsy lung tissue. Crit. Care 15, R4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Araujo B. B., Dolhnikoff M., Silva L. F., Elliot J., Lindeman J. H., Ferreira D. S., Mulder A., Gomes H. A., Fernezlian S. M., James A., and Mauad T. (2008) Extracellular matrix components and regulators in the airway smooth muscle in asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 32, 61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ayars A. G., Altman L. C., Potter-Perigo S., Radford K., Wight T. N., and Nair P. (2013) Sputum hyaluronan and versican in severe eosinophilic asthma. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 161, 65–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gordon S. (2002) Pattern recognition receptors: doubling up for the innate immune response. Cell 111, 927–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alexopoulou L., Holt A. C., Medzhitov R., and Flavell R. A. (2001) Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413, 732–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vigetti D., Genasetti A., Karousou E., Viola M., Moretto P., Clerici M., Deleonibus S., De Luca G., Hascall V. C., and Passi A. (2010) Proinflammatory cytokines induce hyaluronan synthesis and monocyte adhesion in human endothelial cells through hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS2) and the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24639–24645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilkinson T. S., Potter-Perigo S., Tsoi C., Altman L. C., and Wight T. N. (2004) Pro- and anti-inflammatory factors cooperate to control hyaluronan synthesis in lung fibroblasts. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 31, 92–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mohamadzadeh M., DeGrendele H., Arizpe H., Estess P., and Siegelman M. (1998) Proinflammatory stimuli regulate endothelial hyaluronan expression and CD44/HA-dependent primary adhesion. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 97–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bauernfeind F. G., Horvath G., Stutz A., Alnemri E. S., MacDonald K., Speert D., Fernandes-Alnemri T., Wu J., Monks B. G., Fitzgerald K. A., Hornung V., and Latz E. (2009) Cutting edge: NF-κB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J. Immunol. 183, 787–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Babelova A., Moreth K., Tsalastra-Greul W., Zeng-Brouwers J., Eickelberg O., Young M. F., Bruckner P., Pfeilschifter J., Schaefer R. M., Gröne H. J., and Schaefer L. (2009) Biglycan, a danger signal that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via Toll-like and P2X receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24035–24048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Allen I. C., Scull M. A., Moore C. B., Holl E. K., McElvania-TeKippe E., Taxman D. J., Guthrie E. H., Pickles R. J., and Ting J. P. (2009) The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity 30, 556–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kim S., Takahashi H., Lin W. W., Descargues P., Grivennikov S., Kim Y., Luo J. L., and Karin M. (2009) Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature 457, 102–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang W., Xu G. L., Jia W. D., Ma J. L., Li J. S., Ge Y. S., Ren W. H., Yu J. H., and Liu W. B. (2009) Ligation of TLR2 by versican: a link between inflammation and metastasis. Arch. Med. Res. 40, 321–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bögels M., Braster R., Nijland P. G., Gül N., van de Luijtgaarden W., Fijneman R. J., Meijer G. A., Jimenez C. R., Beelen R. H., and van Egmond M. (2012) Carcinoma origin dictates differential skewing of monocyte function. Oncoimmunology 1, 798–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Li D., Wang X., Wu J. L., Quan W. Q., Ma L., Yang F., Wu K. Y., and Wan H. Y. (2013) Tumor-produced versican V1 enhances hCAP18/LL-37 expression in macrophages through activation of TLR2 and vitamin D3 signaling to promote ovarian cancer progression in vitro. PLoS One 8, e56616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Said N., Sanchez-Carbayo M., Smith S. C., and Theodorescu D. (2012) RhoGDI2 suppresses lung metastasis in mice by reducing tumor versican expression and macrophage infiltration. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1503–1518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Said N., and Theodorescu D. (2012) RhoGDI2 suppresses bladder cancer metastasis via reduction of inflammation in the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology 1, 1175–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang Z., Miao L., and Wang L. (2012) Inflammation amplification by versican: the first mediator. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 6873–6882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hope C., Ollar S. J., Heninger E., Hebron E., Jensen J. L., Kim J., Maroulakou I., Miyamoto S., Leith C., Yang D. T., Callander N., Hematti P., Chesi M., Bergsagel P. L., and Asimakopoulos F. (2014) TPL2 kinase regulates the inflammatory milieu of the myeloma niche. Blood 123, 3305–3315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tang M., Diao J., Gu H., Khatri I., Zhao J., and Cattral M. S. (2015) Toll-like receptor 2 activation promotes tumor dendritic cell dysfunction by regulating IL-6 and IL-10 receptor signaling. Cell Rep. 13, 2851–2864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schaefer L., Babelova A., Kiss E., Hausser H. J., Baliova M., Krzyzankova M., Marsche G., Young M. F., Mihalik D., Götte M., Malle E., Schaefer R. M., and Gröne H. J. (2005) The matrix component biglycan is proinflammatory and signals through Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2223–2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Moreth K., Frey H., Hubo M., Zeng-Brouwers J., Nastase M. V., Hsieh L. T., Haceni R., Pfeilschifter J., Iozzo R. V., and Schaefer L. (2014) Biglycan-triggered TLR-2- and TLR-4-signaling exacerbates the pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. Matrix Biol. 35, 143–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kawashima H., Hirose M., Hirose J., Nagakubo D., Plaas A. H., and Miyasaka M. (2000) Binding of a large chondroitin sulfate/dermatan sulfate proteoglycan, versican, to L-selectin, P-selectin, and CD44. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35448–35456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Misra S., Toole B. P., and Ghatak S. (2006) Hyaluronan constitutively regulates activation of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases in epithelial and carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34936–34941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Misra S., Ghatak S., and Toole B. P. (2005) Regulation of MDR1 expression and drug resistance by a positive feedback loop involving hyaluronan, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and ErbB2. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20310–20315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ghatak S., Misra S., and Toole B. P. (2005) Hyaluronan constitutively regulates ErbB2 phosphorylation and signaling complex formation in carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8875–8883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ghatak S., Misra S., and Toole B. P. (2002) Hyaluronan oligosaccharides inhibit anchorage-independent growth of tumor cells by suppressing the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt cell survival pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38013–38020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bourguignon L. Y., Gilad E., and Peyrollier K. (2007) Heregulin-mediated ErbB2-ERK signaling activates hyaluronan synthases leading to CD44-dependent ovarian tumor cell growth and migration. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 19426–19441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ohkawa T., Ueki N., Taguchi T., Shindo Y., Adachi M., Amuro Y., Hada T., and Higashino K. (1999) Stimulation of hyaluronan synthesis by tumor necrosis factor-α is mediated by the p50/p65 NF-κB complex in MRC-5 myofibroblasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1448, 416–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Han H., and Ziegler S. F. (2013) Bronchoalveolar lavage and lung tissue digestion. Bio. Protoc. 3, e859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shih S. C., and Smith L. E. (2005) Quantitative multi-gene transcriptional profiling using real-time PCR with a master template. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 79, 14–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Schönherr E., Kinsella M. G., and Wight T. N. (1997) Genistein selectively inhibits platelet-derived growth factor stimulated versican biosynthesis in monkey arterial smooth muscle cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 339, 353–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Masuda A., Yasuoka H., Satoh T., Okazaki Y., Yamaguchi Y., and Kuwana M. (2013) Versican is upregulated in circulating monocytes in patients with systemic sclerosis and amplifies a CCL2-mediated pathogenic loop. Arthritis Res. Ther. 15, R74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.