Abstract

Regulation of the immune response is a multifaceted process involving lymphocytes that function to maintain both self tolerance as well as homeostasis following productive immunity against microbes. There are 2 broad categories of Tregs that function in different immunological settings depending upon the context of antigen exposure and the nature of the inflammatory response. During massive inflammatory conditions such as microbial exposure in the gut or tissue transplantation, regulatory CD4+CD25+ Tregs broadly suppress priming and/or expansion of polyclonal autoreactive responses nonspecifically. In other immune settings where initially a limited repertoire of antigen-reactive T cells is activated and expanded, TCR-specific negative feedback mechanisms are able to achieve a fine homeostatic balance. Here I will describe experimental evidence for the existence of a Treg population specific for determinants that are derived from the TCR and are expressed by expanding myelin basic protein–reactive T cells mediating experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, an animal prototype for multiple sclerosis. These mechanisms ensure induction of effective but appropriately limited responses against foreign antigens while preventing autoreactivity from inflicting escalating damage. In contrast to CD25+ Tregs, which are most efficient at suppressing priming or activation, these specific Tregs are most efficient in controlling T cells following their activation.

A historical perspective on specific Tregs in feedback regulation

Feedback inhibition in macromolecular synthetic pathways has been described as the mechanism by which the end product either inhibits formation of or suppresses enzymes in its biosynthetic pathway, thus specifically limiting the accumulation of that end product. The idea proposed by Neils Jerne (1) that specialized lymphocytes might inhibit immune responses gave rise to the description of suppressor T cells in vitro in the 1960s and 1970s (2–5). Some of the initial indications of the existence of Tregs in vivo came from studies in the mid-1970s involving alloresponses wherein vaccination with polyclonal T lymphoblasts from a parental strain into F1 hybrid rats abrogated anti-alloresponse and graft rejection (6, 7). These findings were followed by the demonstration that vaccination with an attenuated myelin basic protein–reactive (MBP-reactive) but not a purified protein derivative of mycobacterium–reactive cloned T cell line prevented MBP-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in Lewis rats, further suggesting the induction of immunity against the antigen receptors on autoimmune lymphocytes (8). Cytotoxic CD8+ T cell lines capable of responding to T cells were induced in rats recovering from graft-versus-host disease or from T cell–mediated EAE (9, 10). Thus, killing of encephalitogenic CD4+ T cell lines in vitro by cytotoxic CD8+ as well as neutralization of their capacity in vivo to cause EAE clearly indicated that CD8+ Tregs recognizing some cell surface molecules on vaccinating CD4+ can be induced. Moreover in human studies, CD8+ T cells, which were isolated from CD4+ T cell–vaccinated subjects, specifically lysed the inciting CD4+ T cells in vitro, and accordingly vaccination resulted in a decrease in the frequency of MBP-reactive T cells in peripheral blood lymphocytes (11). Consistent with the role of CD8+ Tregs, mice functionally deficient in CD8+ T cells, either by gene targeting or by antibody depletion, were shown to develop a higher frequency of relapses and lost resistance to reinduction of EAE upon secondary immunization (12, 13). These data suggest a negative feedback regulatory mechanism involving a regulatory T cell population that is induced by a pathogenic T cell itself (“suicidal induction”) and may be specific for molecules on the aggressive T cells. These molecules are either activation “ergotypic” markers or antigen receptors (TCRs) on T cells (14, 15). Recent data further suggest that these Tregs are also present in naive animals and can be further expanded in response to antigen-activated T cells (ref. 16; Madakamutil and Kumar, unpublished data).

Specificity for regulation is provided by the recognition of TCR peptide/MHC complexes

Most work on the characterization of the specific Tregs comes from studies of the regulation of the anti-MBP response mediating EAE in Lewis rats or in B10.PL or PL/J mice. There are 3 critical features in these model systems that allow examination of whether TCR peptides are part of the target structures recognized by Tregs: (a) initially, the immune response to MBP is primarily targeted to a single immunodominant determinant (17, 18); (b) pathogenic T cells recognizing this immunodominant peptide predominantly express the TCR Vβ8.2 chain (19–22); and (c) the clinical disease is largely monophasic, and most animals spontaneously recover and are resistant to reinduction of EAE. Thus, in both the Lewis rat and murine models of EAE, immunization with peptides derived from the TCR Vβ8.2 chain resulted in the induction of CD4+ and CD8+ Treg responses that lead to protection from EAE; this suggests that the TCR or peptides derived from the TCR of autoimmune T cells can be targeted for recognition by Tregs (23–29). It is not yet known whether the mechanisms or the phenotype of Tregs following the T cell–vaccination protocol or following TCR-peptide vaccination are the same.

TCR peptides derived mostly from the conserved complementarity determining region (CDR) and framework (Fr) regions of the TCR Vβ-chains have been found to be immunogenic in both animals and in humans (23–35). Although the phenotype or the MHC restriction of Tregs has not been defined in most cases, it is clear that peptides from 2 distinct conserved regions, namely the Fr3 and CDR1/2 regions on the TCR Vβ8.2 chain, can induce regulation and protection from antigen-induced EAE in both rats and B10.PL mice (15, 26, 27, 29, 30, 36–40). It is noteworthy that in humans, both the CDR2 and Fr3 regions have been found to be immunogenic and can potentially induce Treg activity (34, 35, 41).

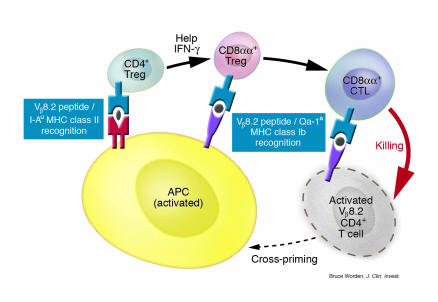

A better understanding of the antigen specificity and MHC restriction of Tregs at the clonal level comes from studies of regulation of the anti-MBP response in B10.PL mice (see Figure 1). Two distinct populations of Tregs that collaborate to control EAE have been characterized. CD4+ Tregs are specific for a determinant from the Fr3 region (peptide B5, AAs 76–101) that binds to the MHC class II molecule I-Au. The CD4+ Tregs are predominantly Vβ14+ and help in the recruitment or activation of CD8+ Tregs, which ultimately deplete activated MBP-reactive pathogenic Vβ8.2+ CD4+ Th1 cells. CD8+ Tregs recognize a different determinant from the CDR1/2 region (p42–50, AAs 42–50 of the Vβ8.2 chain) in the context of a nonclassical MHC class Ib molecule, Qa-1a (Tang and Kumar, unpublished data). Nonclassical class I molecules are less polymorphic in comparison to the classical class I molecules. CD8+ T cell hybridomas reactive to Vβ8.2+ T cells isolated from T cell–vaccinated mice have been shown to be restricted by the Qa-1 MHC class Ib molecules (42–44). Evidence that Qa-1–restricted CD8+ Tregs are actually involved in the regulation of autoimmune disease comes from experiments in which adoptive transfer of Qa-1a–restricted CD8+ T cell clones reactive to the p42–50 peptide from the Vβ8.2 TCR prevents MBP-induced EAE in syngeneic recipients (Tang et al., unpublished data). These functional CD8+ Tregs are Qa-1a restricted despite the ability of some TCR peptides to induce class Ia–restricted CD8+ T cells (45). They also express CD8αα homodimers (Tang and Kumar, unpublished data), a characteristic of intraepithelial lymphocytes in the intestinal mucosa (46). Recognition of TCR/Qa-1 complexes on T cells raises a number of important issues: for example, have T cells developed specialized processing and loading machinery for a preferential surface display of TCR peptide/Qa-1 complexes following activation; and are activation, differentiation, or amplification of Qa-1–restricted CD8+ Tregs more dependent upon help provided by CD4+ Tregs than class Ia–restricted CD8+ T cells?

Figure 1.

A negative-feedback regulatory mechanism involving CD4+ and CD8+ Tregs recognizing TCR peptide/MHC complexes. During normal peripheral turnover or following the expansion/contraction phase, MBP-reactive, Vβ8.2+ CD4+ T cells are captured by professional APCs. These APCs process and present distinct TCR Vβ8.2 peptides in the context of I-Au MHC class II and Qa-1a MHC class Ib molecules for the induction of CD4+ and CD8+ Tregs, respectively, a process commonly referred to as cross-priming. CD4+ Tregs predominantly utilize the TCR Vβ14 gene segment, recognize an Fr3 region TCR peptide, and secrete type 1 proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, for effective recruitment or activation of CD8+ Tregs. CD8+ Tregs recognize CDR1/2 region TCR peptide/Qa-1a complexes on the surface of activated and pathogenic Vβ8.2+ Th1 cells, resulting in their apoptotic death. Low avidity, slower-reacting Th2 cells that are relatively less susceptible to apoptosis can then eventually expand, resulting in immune deviation of the anti-MBP response at the population level. At this stage, Th2 cell secretion of cytokines such as IL-4 or IL-10 can further enhance the downregulation of the anti-MBP response (41).

Two sets of experiments clearly suggested that TCR peptide–reactive Tregs are naturally involved in the negative feedback regulation of the anti-MBP response and mediate recovery from EAE: (a) Tregs expand naturally during the course of EAE, and recovery from disease can be rapidly accelerated by immunization with either the Fr3 or CDR1/2 TCR peptide in both rats and mice (26–28, 38, 47); and (b) since CD4+ Tregs expressed limited TCR Vβ gene segments, antibodies against these Vβ chains were used to specifically deplete regulatory T cells. Depletion of Tregs resulted in poor recovery and increased severity of relapsing paralysis (28, 39). These studies were complemented by experiments demonstrating that the adoptive transfer of CD4+ Treg clones into WT but not into CD8+ T cell–knockout mice result in significant protection from antigen-induced EAE (26).

Specific regulation is mediated by depletion of activated MBP-reactive CD4+ lymphocytes by CD8+ Tregs

Self antigen–reactive T cells can be downregulated by several mechanisms, including the induction of anergy, which is a loss of the ability to respond to a particular antigen; and cellular depletion or deviation toward a type 2 cytokine secretion phenotype (48–50). Although in vivo studies using TCR-peptide vaccination suggested induction of anergy (51) in the target Vβ8.2+ T cell population, CD8+ Treg lines and hybridomas generated following T cell vaccination show in vitro killing of these cells (10, 42). Recent studies examining the fate of MBP-reactive Vβ8.2+ T cells using CFSE labeling as well as immunoscope analysis clearly demonstrate that the target Vβ8.2+ T cells undergo apoptotic depletion in vivo following expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ Tregs in B10.PL mice (16) (Figure 1). These in vivo findings are consistent with in vitro data showing specific killing of Vβ8.2+ but not Vβ8.2– T cell targets by TCR peptide–reactive CD8+ T cell clones (Tang and Kumar, unpublished data) as well as by CD8+ hybridomas generated from T cell–vaccinated mice (42). Significantly, only activated Vβ8.2+ T cells, but not naive Vβ8.2+ or activated Vβ13+ T cells, are depleted following regulation (16). Consistent with the requirement for CD8+ Tregs in depletion of the dominant pathogenic Vβ8.2+ T cells, expansion of MBP-reactive Vβ8.2+ T cell clones occurs in CD8+ T cell–depleted animals (52). Therefore, the regulation mediated by Tregs does not influence the majority of the Vβ8.2+ T cells (which are nonactivated) but only those that are activated by MBP. It is significant that CD8+ Tregs appear to modulate only Th1 cells and not Th2 cells both in vitro as well as in vivo (53, 54). This does not appear to be due to a difference in the TCR or Qa-1 expression but may involve either differential TCR processing or different recognition motifs. Furthermore, Th1 cells are considerably more sensitive to apoptosis than Th2 cells.

CD4+ Tregs provide crucial help for the recruitment of CD8+ Tregs, which are the ultimate effectors of regulation (Figure 1). Interestingly, Fr3 peptide–reactive CD4+ Treg clones secrete large amounts of IL-2 and IFN-γ, but barely detectable levels of IL-4 and IL-5, and do not secrete IL-10 or TGF-β (26, 54). Accordingly, a CD4+ Treg response of the type 1 sort is required in vivo for effective regulation and prevention of disease. If these CD4+ Tregs are forced to deviate in a type 2 direction, mice contract exacerbated EAE, and most die from paralysis without recovery (54, 55). Recent experiments using CD4+ Tregs from IFN-γ–knockout mice further suggest that secretion of IFN-γ by CD4+ Tregs is absolutely required for this regulation (Pedersen and Kumar, unpublished data).

The depletion of high-avidity activated Th1 cells by CD8+ Tregs enables a relatively slower reacting compartment of low-avidity, MBP-reactive Th2 cells (which may or may not express Vβ8.2) to expand, resulting in immune deviation of the anti-MBP response (40, 54, 56, 57). Thus, the eventual outcome of TCR-based regulation is the deviation of MBP-reactive T cells at the bulk population level in a Th2 direction. This may explain why TCR-based regulation directed to a single Vβ chain is able to control disease-inducing T cells that use other TCR Vβ chains, thereby providing a suppressive environment for responses to other determinants from the same protein as well as from other myelin components that may arise as a result of determinant spreading during chronic demyelination (58). Consistent with this, Th2 deviation of antigen-specific T cells using an altered peptide ligand has been shown to result in the disappearance of the bulk of the T cell infiltrate from the CNS and reversal of EAE (59). Therefore targeting of only a few dominant autoreactive T cells can abort autoimmune pathology.

TCR peptide/MHC complex recognition is crucial for the induction and function of Tregs

How are TCR-reactive Tregs naturally primed in vivo? In light of recent studies (ref. 44; Tang and Kumar, unpublished data), it is reasonable to predict that the cell-surface display of TCR peptide/Qa-1 complexes on the activated target CD4+ T cells is required for their specific recognition and eventual killing by CD8+ Tregs (Figure 1). Although it has been suggested that Qa-1+–activated T cells themselves can prime CD8+ Tregs directly (44), there is little in vivo evidence demonstrating priming of naive CD4+ or CD8+ T cells by lymphocytes in the absence of professional APCs. Therefore, I would like to propose that presentation of TCR peptides by professional APCs such as dendritic cells, macrophages, or B cells, is essential for the cross-priming of both CD4+ and CD8+ Treg. The same APC could present TCR determinants in MHC class Ib and class II contexts to effectively prime both CD8+ Tregs and CD4+ Tregs, respectively. A critical aspect in TCR-centered regulation might be the presence of suitable processing sites in the TCR Vβ framework or in the CDR1/2 regions. Examination of these determinants in the Fr3 and CDR2 regions of the Vβ8.2 chain suggests that they may be particularly available for processing, since they possess endopeptidase target residues that would permit their cleavage.

How general is the mechanism of feedback regulation based on the recognition of TCR peptide/MHC complexes? Can peptides derived from other TCR Vβ chains be processed and presented in sufficient quantity to generate specific Tregs? Is display of TCR peptides on APCs limited to particular Vβ families with a high frequency in the periphery? Since Vβ8-expressing T cells in most mice constitute almost 20–30% of the total peripheral T cell repertoire, it is possible that professional APCs can capture apoptotic T cells during normal peripheral turnover and process and present TCR determinants in both MHC class Ib and class II contexts. A similar situation occurs during antiviral immune response, where viral determinant–reactive T cells using certain TCR Vβ chains expand rapidly and can occupy up to 50% of the peripheral repertoire (60). Antigen-induced cell death of the large number of these activated T cells may result in cross-priming of anti-TCR CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses. It is possible that the depletion of activated viral antigen–reactive T cells in the contraction phase of the response that is followed by a successful anti-viral response may be augmented by TCR peptide–reactive CD8+ Tregs. Therefore, this regulation may be a generalized mechanism involved in the establishment of homeostasis following infections, transplantation, and an autoimmune response.

Use of TCR delivery systems can be exploited for specific intervention in T cell–mediated immune pathologies

Priming of TCR peptide–reactive Tregs following vaccination with disease-related T cells or their TCRs has been demonstrated both to prevent and to ameliorate autoimmune disease in experimental animals, which has led to clinical trials of TCR-based vaccinations in MS and RA in humans (41, 61–63). Clinical trials of T cell vaccination in MS patients are currently ongoing (L. Weiner, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA, and J. Zhang, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA; personal communication). Success of these trials will depend upon the identification of dominant pathogenic T cell clones as well as relevant TCR peptides for use in vaccination. Although class Ib molecules, for example, Qa-1 in mouse and its equivalent HLA-E in humans, are highly conserved, it is likely that in different haplotypes, different TCR peptides might be targeted by the MHC class II–restricted CD4+ Treg population. Therefore, therapeutic delivery of an entire TCR Vβ chain may be more broadly effective and less cumbersome than the individual peptides. This is especially true for those situations where response to an antigen consists of T cells that utilize several predominant TCR Vβ regions. In fact, delivery of multiple TCR Vβ chains has been shown to be more effective than a single Vβ chain in modulating autoimmune myocarditis mediated by a polyclonal T cell response (64). We and others have used different approaches in trying to determine the most efficient means of presentation of the TCR for modulation of autoimmune responses, including TCR peptides, recombinant single-chain Vβ8.2 proteins, Vβ8.2 plasmid DNA, and a Vβ8.2 adenovirus or vaccinia delivery system (38, 55–57, 65, 66).

One can predict that future investigations will reveal a detailed description of this specific regulatory process. Therefore in contrast to the generalized suppression mediated by CD25+CD4+ Tregs, a detailed knowledge of TCR-based regulation as well as the identification of pathogenic lymphocytes in different clinical settings will enable a search for sophisticated ways of modulating immune responses in a more targeted fashion. This will involve the engagement of naturally occurring pathways inherent in the immune system at appropriate times to obtain a desired control of the immune response. If display of the TCR peptide/MHC complex can be appropriately manipulated, TCR-based regulation should be able to be exploited for modulating a wide variety of immune responses, including those involved in transplantation, infection, tumors, and autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my colleagues, especially Eli Sercarz, for their help, and Randle Ware for critical reading of the manuscript. These studies were supported by grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG 2765B3) and the NIH (R21 CA091140 and R01 AI052227) to V. Kumar.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: CDR, complementarity determining region; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; Fr, framework; MBP, myelin basic protein.

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Jerne NK. Idiotypic networks and other preconceived ideas. Immunol. Rev. 1984;79:5–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1984.tb00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gershon RK, Kondo K. Cell interactions in the induction of tolerance: the role of thymic lymphocytes. Immunology. 1970;18:723–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantor H, Boyse EA. Functional subclasses of T lymphocytes bearing different Ly antigens. II. Cooperation between subclasses of Ly+ cells in the generation of killer activity. J. Exp. Med. 1975;141:1390–1399. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.6.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantor H, Gershon RK. Immunological circuits: cellular composition. Fed. Proc. 1979;38:2058–2064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eardley DD, Gershon RK. Feedback induction of suppressor T-cell activity. J. Exp. Med. 1975;142:524–529. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.2.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binz H, Wigzell H. Specific transplantation tolerance induced by autoimmunization against the individual’s own, naturally occurring idiotypic, antigen-binding receptors. J. Exp. Med. 1976;144:1438–1457. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.6.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellgrau D, Wilson DB. Immunological studies of T-cell receptors. I. Specifically induced resistance to graft-versus-host disease in rats mediated by host T-cell immunity to alloreactive parental T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1978;148:103–114. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Nun A, Wekerle H, Cohen IR. Vaccination against autoimmune encephalomyelitis with T-lymphocyte line cells reactive against myelin basic protein. Nature. 1981;292:60–61. doi: 10.1038/292060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura H, Wilson DB. Anti-idiotypic cytotoxic T cells in rats with graft-versus-host disease. Nature. 1984;308:463–464. doi: 10.1038/308463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun D, Qin Y, Chluba J, Epplen JT, Wekerle H. Suppression of experimentally induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis by cytolytic T-T cell interactions. Nature. 1988;332:843–845. doi: 10.1038/332843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Medaer R, Stinissen P, Hafler D, Raus J. MHC-restricted depletion of human myelin basic protein-reactive T cells by T cell vaccination. Science. 1993;261:1451–1454. doi: 10.1126/science.7690157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koh D-R, et al. Less mortality but more relapses in experimental allergic encephalomyeltis in CD8–/– mice. Science. 1992;256:1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang H, Zhang SI, Pernis B. Role of CD8+ T cells in murine experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Science. 1992;256:1213–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohse AW, et al. Induction of the anti-ergotypic response. Int. Immunol. 1993;5:533–539. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar V, Sercarz E. T cell regulatory circuitry: antigen-specific and TCR-idiopeptide- specific T cell interactions in EAE. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1993;9:287–297. doi: 10.3109/08830189309051212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madakamutil LT, Maricic I, Sercarz E, Kumar V. Regulatory T cells control autoimmunity in vivo by inducing apoptotic depletion of activated pathogenic lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2003;170:2985–2992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kibler RF, et al. Immune response of Lewis rats to peptide C1 (residues 68–88) of guinea pig and rat myelin basic proteins. J. Exp. Med. 1977;146:1323–1331. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.5.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zamvil SS, et al. T-cell epitope of the autoantigen myelin basic protein that induces encephalomyelitis. Nature. 1986;324:258–260. doi: 10.1038/324258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urban JL, et al. Restricted use of T cell receptor V genes in murine autoimmune encephalomyelitis raises possibilities for antibody therapy. Cell. 1988;54:577–592. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acha-Orbea H, et al. Limited heterogeneity of T cell receptors from lymphocytes mediating autoimmune encephalomyelitis allows specific immune intervention. Cell. 1988;54:263–273. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90558-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar V, Kono DH, Urban JL, Hood L. The T-cell receptor repertoire and autoimmune diseases. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1989;7:657–682. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burns FR, et al. Both rat and mouse T cell receptors specific for the encephalitogenic determinant of myelin basic protein use similar V and V chain genes. J. Exp. Med. 1989;169:27–39. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howell MD, et al. Vaccination against experimental allergic encephalomyelitis with T cell receptor peptides. Science. 1989;246:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.2814489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandenbark AA, Hashim G, Offner H. Immunization with a synthetic T-cell receptor V-region peptide protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature. 1989;341:541–544. doi: 10.1038/341541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karpus WJ, Gould KE, Swanborg RH. CD4+ suppressor cells of autoimmune encephalomyelitis respond to T cell receptor-associated determinants on effector cells by interleukin-4 secretion. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:1757–1763. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar V, Sercarz E. The involvement of TCR-peptide-specific regulator CD4+ T cells in recovery from antigen-induced autoimmune disease. J. Exp. Med. 1993;178:909–916. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar V, Tabibiazar R, Geysen HM, Sercarz E. Immunodominant framework region 3 peptide from TCR V beta 8.2 chain controls murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 1995;154:1941–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar V, Stellrecht K, Sercarz E. Inactivation of T cell receptor peptide-specific CD4 regulatory T cells induces chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1609–1617. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar V, Aziz F, Sercarz E, Miller A. Regulatory T cells specific for the same framework 3 region of the Vbeta8.2 chain are involved in the control of collagen II-induced arthritis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1725–1733. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vainiene M, et al. Neonatal injection of Lewis rats with recombinant V beta 8.2 induces T cell but not B cell tolerance and increased severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996;45:475–486. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960815)45:4<475::AID-JNR18>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacNeil D, Fraga E, Singh B. Characterization of murine T cell responses to peptides of the variable region of self T cell receptor beta-chains. J. Immunol. 1993;151:4045–4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jesson MI, et al. The immune response to soluble D10 TCR: analysis of antibody and T cell responses. Int. Immunol. 1998;10:27–35. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falcioni F, et al. Self tolerance to T cell receptor V beta sequences. J. Exp. Med. 1995;182:249–254. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saruhan-Direskeneli G, et al. Human T cell autoimmunity against myelin basic protein: CD4+ cells recognizing epitopes of the T cell receptor beta chain from a myelin basic protein-specific T cell clone. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993;23:530–536. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zang YC, Hong J, Rivera VM, Killian J, Zhang JZ. Preferential recognition of TCR hypervariable regions by human anti- idiotypic T cells induced by T cell vaccination. J. Immunol. 2000;164:4011–4017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vandenbark AA, Hashim GA, Offner H. T cell receptor peptides in treatment of autoimmune disease: rationale and potential. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996;43:391–402. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960215)43:4<391::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar V, Sercarz E. Dysregulation of potentially pathogenic self reactivity is crucial for the manifestation of clinical autoimmunity. J. Neurosci. Res. 1996;45:334–339. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960815)45:4<334::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar V, et al. Recombinant T cell receptor molecules can prevent and reverse experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: dose effects and involvement of both CD4 and CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 1997;159:5150–5156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar V. TCR peptide-reactive T cells and peripheral tolerance to myelin basic protein. Res. Immunol. 1998;149:827–834; discussion 852–854, 855–860. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(99)80011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar V, Sercarz E. An integrative model of regulation centered on recognition of TCR peptide/MHC complexes. Immunol. Rev. 2001;182:113–121. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandenbark AA, et al. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with T-cell receptor peptides: results of a double-blind pilot trial. Nat. Med. 1996;2:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang H, et al. Murine CD8+ T cells that specifically delete autologous CD4+ T cells expressing V beta 8 TCR: a role of the Qa-1 molecule. Immunity. 1995;2:185–194. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(95)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang H, et al. T cell vaccination induces T cell receptor Vbeta-specific Qa-1- restricted regulatory CD8(+) T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:4533–4537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang H, Chess L. The specific regulation of immune responses by CD8+ T cells restricted by the MHC class Ib molecule, Qa-1. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:185–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuhrober A, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J. Vaccination with T cell receptor peptides primes anti-receptor cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and anergizes T cells specifically recognized by these CTL. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:1172–1180. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gapin L, Cheroutre H, Kronenberg M. Cutting edge: TCR alpha beta+ CD8 alpha alpha+ T cells are found in intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes of mice that lack classical MHC class I molecules. J. Immunol. 1999;163:4100–4104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Offner H, Hashim GA, Vandenbark AA. T cell receptor peptide therapy triggers autoregulation of experimental encephalomyelitis. Science. 1991;251:430–432. doi: 10.1126/science.1989076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mueller DL, Jenkins MK, Schwartz RH. Clonal expansion versus functional clonal inactivation: a costimulatory signalling pathway determines the outcome of T cell antigen receptor occupancy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1989;7:445–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kappler JW, Roehm N, Marrack P. T cell tolerance by clonal elimination in the thymus. Cell. 1987;49:273–280. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coffman RL, Varkila K, Scott P, Chatelain R. Role of cytokines in the differentiation of CD4+ T-cell subsets in vivo. Immunol. Rev. 1991;123:189–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaur A, Ruberti G, Haspel R, Mayer JP, Fathman CG. Requirement for CD8+ cells in T cell receptor peptide-induced clonal unresponsiveness. Science. 1993;259:91–94. doi: 10.1126/science.8418501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang H, et al. Regulatory CD8+ T cells fine-tune the myelin basic protein-reactive T cell receptor V beta repertoire during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:8378–8383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432871100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang H, Braunstein NS, Yu B, Winchester R, Chess L. CD8+ T cells control the TH phenotype of MBP-reactive CD4+ T cells in EAE mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:6301–6306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101123098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar V, Sercarz E. Induction or protection from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis depends on the cytokine secretion profile of TCR peptide-specific regulatory CD4 T cells. J. Immunol. 1998;161:6585–6591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braciak TA, et al. Protection against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis generated by a recombinant adenovirus vector expressing the V beta 8.2 TCR is disrupted by coadministration with vectors expressing either IL-4 or -10. J. Immunol. 2003;170:765–774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waisman A, et al. Suppressive vaccination with DNA encoding a variable region gene of the T-cell receptor prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis and activates Th2 immunity. Nat. Med. 1996;2:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar V, et al. Induction of a type 1 regulatory CD4 T cell response following V(beta)8.2 DNA vaccination results in immune deviation and protection from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Int. Immunol. 2001;13:835–841. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lehmann PV, Forsthuber T, Miller A, Sercarz EE. Spreading of T-cell autoimmunity to cryptic determinants of an autoantigen. Nature. 1992;358:155–157. doi: 10.1038/358155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brocke S, et al. Treatment of experimental encephalomyelitis with a peptide analogue of myelin basic protein. Nature. 1996;379:343–346. doi: 10.1038/379343a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murali-Krishna K, et al. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gold DP, et al. Results of a phase I clinical trial of a T-cell receptor vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. II. Comparative analysis of TCR utilization in CSF T-cell populations before and after vaccination with a TCRV beta 6 CDR2 peptide. J. Neuroimmunol. 1997;76:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang I, Raus J. T cell vaccination in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 1996;1:353–356. doi: 10.1177/135245859600100615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar V, Sercarz E, Zhang J, Cohen I. T-cell vaccination: from basics to the clinic. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:539–540. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsumoto Y, Jee Y, Sugisaki M. Successful TCR-based immunotherapy for autoimmune myocarditis with DNA vaccines after rapid identification of pathogenic TCR. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2248–2254. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumar V, Sercarz E. Genetic vaccination: the advantages of going naked. Nat. Med. 1996;2:857–859. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chunduru SK, Sutherland RM, Stewart GA, Doms RW, Paterson Y. Exploitation of the Vbeta8.2 T cell receptor in protection against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis using a live vaccinia virus vector. J. Immunol. 1996;156:4940–4945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]