Abstract

Epigenetic modifications and other chromatin features partition the genome on multiple length scales. They define chromatin domains with distinct biological functions that come in sizes ranging from single modified DNA bases to several megabases in the case of heterochromatic histone modifications. Due to chromatin folding, domains that are well separated along the linear nucleosome chain can form long-range interactions in three-dimensional space. It has now become a routine task to map epigenetic marks and chromatin structure by deep sequencing methods. However, assessing and comparing the properties of chromatin domains and their positional relationships across data sets without a priori assumptions remains challenging. Here, we introduce multiscale correlation evaluation (MCORE), which uses the fluctuation spectrum of mapped sequencing reads to quantify and compare chromatin patterns over a broad range of length scales in a model-independent manner. We applied MCORE to map the chromatin landscape in mouse embryonic stem cells and differentiated neural cells. We integrated sequencing data from chromatin immunoprecipitation, RNA expression, DNA methylation, and chromosome conformation capture experiments into network models that reflect the positional relationships among these features on different genomic scales. Furthermore, we used MCORE to compare our experimental data to models for heterochromatin reorganization during differentiation. The application of correlation functions to deep sequencing data complements current evaluation schemes and will support the development of quantitative descriptions of chromatin networks.

Introduction

Most processes in eukaryotic cells that involve interactions with the genome are controlled by the chromatin context. Accordingly, DNA replication, DNA repair, RNA expression, and RNA splicing have been found to be regulated by different combinations of DNA methylation (5mC) and histone modifications (1, 2). The genomewide distribution of these and other chromatin features, like binding sites of transcription factors, contact frequencies between genomic loci, and transcriptional activity, can routinely be assessed by deep sequencing (1). Recent methodological developments enable the analysis of low cell numbers or even single cells (3, 4, 5), the simultaneous readout of various features (6), and the measurement of site-specific binding dynamics (7). Thus, sequencing data at unprecedented resolution and throughput are becoming available, providing a rich source of information on molecular networks that shape the chromatin landscape. However, there is a gap between the widely used techniques for the qualitative analysis of sequencing data and what is needed for testing biophysical models that quantitatively describe the dynamics of chromatin states and long-range gene regulation (8). Specific objectives are, for example, to relate the size and shape of modified domains to the underlying formation mechanism; to assess the contribution of chromatin contacts to the establishment and maintenance of chromatin states; and to describe the positional relationship among different marks, which is an important step toward understanding the function of distal regulatory elements.

Currently, deep sequencing data are mostly analyzed on the basis of local enrichments of read density, with the goal to identify regions scoring positive for one or more features of interest. Most of these approaches (see Table S1 for an incomplete list) fall into two categories, namely peak calling algorithms (9, 10, 11) and probabilistic network models (12, 13, 14). Identification of enriched regions typically involves assumptions about their characteristic width and enrichment level, and regions above a certain significance level are considered positive. While this strategy is suitable for finding the most highly enriched genomic regions, it does not preserve the information content of complex patterns that involve different enrichment levels and are incompatible with binarization (Fig. S1). Furthermore, undersampling, noise, and technical bias represent complications that can change the apparent read density at individual loci, thereby introducing or masking similarities between data sets when comparing them based on sets of local enrichments (15, 16, 17). Due to these difficulties, peak calling results depend on user-defined input parameters and the specific algorithm used (18, 19). In turn, chromatin state annotations differ with respect to state number, state identity, and spatial extension of the corresponding chromatin domains (12, 13). These uncertainties are particularly critical for the study of heterochromatic regions, which contain a combination of broadly distributed histone marks, 5mC, and associated proteins (20, 21). Accordingly, quantitative comparisons between the genomewide topology of heterochromatin domains and the predictions from mechanistic models for the formation and maintenance of heterochromatin states (e.g., Müller-Ott et al. (22), Hodges and Crabtree (23), and Erdel and Greene (24) and references therein) are currently fraught with difficulties.

Here, we introduce an approach termed “multiscale correlation evaluation” (MCORE) that complements the above-mentioned repertoire of analysis methods for deep sequencing data. MCORE avoids assumptions about the shape and the amplitude of enriched regions and evaluates all mapped sequencing reads without filtering. It retrieves information from correlation functions, which are used for the discovery of patterns in noisy and possibly undersampled data sets in many fields of research (25, 26, 27, 28, 29). The use of correlation functions in the context of deep sequencing has mostly been restricted to strand cross correlation for measuring fragment lengths (18, 30) and short-range autocorrelation for comparing chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data sets to each other (31). Key advantages of correlation functions are the intrinsic removal of (white) noise, robust identification of characteristic length scales, and straightforward assessment of spatial relationships between two different features. Conveniently, correlation functions can be used to retrieve information about patterns with unknown geometry (Fig. S1). We used MCORE to analyze the chromatin landscape of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and neural cells (neural progenitor/brain cells, NCs) as their differentiated counterparts, focusing on 11 different chromatin features (Table S2). These data sets covered histone modifications, DNA methylation, RNA expression, genome folding, and binding of chromatin-associated proteins. For each feature, we identified the associated nucleosome repeat length and the characteristic domain sizes along with their relative abundance in the genome. In a pairwise analysis we determined the (anti)colocalization and positional relationship between features on different genomic scales and used the results to construct network models for chromatin signaling. We compared ESCs to NCs to retrieve information about the spatial reorganization of chromatin during differentiation and to map the global transitions that occurred at active and repressive chromatin domains. Alterations were most pronounced for heterochromatic H3K9me3/H3K27me3 regions that changed their size, their location within chromosome territories, and their positioning relative to DNA methylation and to each other.

Materials and Methods

Calculation of normalized occupancy profiles

Sequencing reads were mapped to the mouse mm9 assembly using the software Bowtie (32). Only uniquely mapping reads without mismatches were considered and duplicates were removed. Mapped reads were processed according to the following steps: Bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) data, which are used to map DNA methylation at single basepair resolution, are usually available as methylation scores calculated from the ratio of converted reads divided by the sum of converted and unconverted reads at a given position. These can be directly used for computing the correlation function as described below. For all other sequencing readouts, the coverage was initially calculated for each chromosome by extending the reads to fragment length, yielding a histogram with the genomic coordinate on the x axis and the number of reads per basepair on the y axis. For Hi-C and ChIA-PET data, only interchromosomal reads were considered to identify the surface of chromosome territories. To calculate normalized occupancy profiles, samples were processed depending on the type of experiment. In general, it is important to account for fragmentation bias, library preparation bias, and genome mappability. These multiplicative biases are also included in the input sample and should cancel out in the ratio of specific signal A and input signal I (A/I). In RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments, the input signal can be replaced by a sample of nucleosome-free, fragmented genomic DNA. For IP experiments, it is additionally important to account for nonspecific binding during sample preparation to obtain meaningful correlation functions (Fig. S2 B). This is of increasing importance for decreasing signal-to-background ratio (Fig. S2 C). The appropriate control C can be obtained from an IP with a nonspecifically binding antibody (e.g., IgG control) or from a sample that lacks the antigen of interest (e.g., a knockout cell line). We devised the following strategy to compute normalized occupancy profiles that were used in the subsequent analysis. First, the normalized coverage of the control Cnorm and of the specific IP Anorm were obtained by dividing by input signal I according to:

| (1) |

Here, denotes averaging along the genomic coordinate. For the calculation of coverage ( and ) and average values ( and ), positions with zero input coverage were neglected. Subsequently, the coverage at these positions was set to the respective average value ( or ) that was calculated for the remaining positions, thus eliminating fluctuations and corresponding contributions to the correlation coefficient from these positions. In the next step, nonspecific background signal was removed to obtain the normalized read occupancy O:

| (2) |

In Eq. 2, the parameter b quantifies the contribution of the control signal present as background in the sample (IP). To estimate b, we minimized the absolute value of the Pearson correlation coefficient r0 at zero shift distance between the normalized occupancy O and the control coverage Cnorm according to:

| (3) |

Here, n denotes the maximum genomic position considered for the calculation, which is typically the chromosome length. For the minimization procedure, b was changed between 0 and 1. Because the minimum correlation r0(b) indicates the lowest similarity between normalized occupancy profile and control, the corresponding b value was used for normalization according to Eq. 2.

Computation of correlation functions

The Pearson correlation coefficient r at shift distance Δx was calculated for the corrected data sets after shifting the two occupancy profiles O1 and O2 with respect to each other by Δx basepairs according to (similar to Eq. 3 but with a second shifted occupancy instead of the control coverage):

| (4) |

To sample the correlation function in a quasi-logarithmic manner (33), profiles were binned by a factor of two after 25 shift operations to double the step size. To preserve high resolution for small shift distances, the first binning operation was carried out at a shift of Δx = 50 bp. This calculation was done for each chromosome separately because continuous domains cannot exceed chromosomal ends. Most correlation functions shown in the article refer to chromosome 1, which is representative for all chromosomes as judged by the relatively small deviations among chromosomes (see Figs. 2, A and B, and S8 B). However, correlation functions can also be calculated for smaller genomic regions (see Fig. S1 for the correlation function for a single domain).

Figure 2.

Quantification of domain sizes for different histone marks. (A) Correlation functions for replicates in ESCs. Correlation functions calculated between replicates for chromosome 1 (black) and their fit functions (red or gray) with characteristic domain sizes obtained from the fit (vertical dotted lines) are shown. (Gray regions) Maximum variation among chromosomes. Fit residuals are plotted above the correlation curves. Domain sizes and abundances calculated from the respective fit parameters are shown below the correlation curves. (B) Same as in (A) for NCs. (C) MCORE identified broad H3K9me3 domains spanning, on average, 128 kb and 7.6 Mb in NCs, which were absent in ESCs. To annotate the genomic positions of these domains, normalized occupancy values in a sliding window of 128 kb, which corresponded to the smaller domain size, were evaluated. An example of a domain that became broader in NCs is shown (#1 and #2 denote replicates). For clarity, the occupancy profiles were smoothed with 0.2 times the window size (smooth). For window size 7.6 Mb, see Fig. S13. To see this figure in color, go online.

To compare cross-correlation functions between different features, normalization to the geometric mean of the two replicate correlation functions was conducted according to:

| (5) |

Here, rc is the cross-correlation coefficient at a given shift distance Δx, and r1 and r2 are the replicate correlation coefficients of the data sets used. This normalization step accounts for differences in the genomic distributions of the features involved. For calculating the cross-correlation functions between two different features or the same feature in two different cell types, at least two replicates for each sample were used. Accordingly, a cross-correlation function for each combination of replicates was computed, which results in n2 functions for n replicates of each sample, and the average of these correlation functions was reported.

Statistical analysis of correlation functions

Statistical analysis of data was conducted by computing standard errors (SEs) and 95% confidence intervals. To assess significance and associated errors/confidence intervals for a given correlation function, we considered several types of errors:

Statistical error of the computed correlation function

Because correlation functions are calculated from millions of regions, they typically have a very small statistical error. The sample size N for each shift distance Δx is given by the distance between the first and last position that is covered on the chromosome (Pmin and Pmax) subtracted by the shift length (Δx) according to . Based on the sample size, 95% confidence intervals can be obtained using the Fisher transformation (Fig. S8 A) (34, 35). If normalized occupancy values Oi follow a normal distribution reasonably well (Fig. S8 D), the Fisher transformation is a good way to rapidly estimate confidence intervals for correlation coefficients. An alternate nonparametric option that is compatible with arbitrary sample distributions is bootstrapping (36). In this case, occupancy profiles are resampled with replacement in pairs (O1,i, O2,i+Δx) and subsequently used for calculation of the correlation coefficient according to Eq. 4. This procedure is repeated multiple times to obtain a distribution of correlation coefficients for every pair of resampled occupancy profiles (Fig. S8 E) and every shift distance Δx. Based on the width of this distribution, estimates for confidence intervals are obtained. For the cases tested here, bootstrapping yielded moderately larger confidence intervals than those obtained using Fisher transformation, but intervals from both methods were of the same order of magnitude (Fig. S8 F).

Variation among chromosomes

An estimate for the error of genomewide domain structures or positional relationships can be obtained by comparing correlation functions calculated for different chromosomes as shown in Fig. S8 B. If the relationship is governed by the same biological mechanism on all chromosomes, this variation can be used to evaluate the error.

Reproducibility of experiments

Sample preparation might introduce a global bias into a given data set. This is generally true for deep sequencing experiments, irrespectively of which method is used for downstream analysis. Such variations among replicates might not be captured by statistical comparisons conducted on the basis of a single data set or a pair of data sets. Experimental reproducibility can be assessed with MCORE for data sets with at least three different replicates by computing the correlation function for all possible combinations of samples, i.e., n × (n − 1)/2 correlation functions for n replicates. Subsequently, average and SEs are calculated. We found this approach to be particularly useful to identify variations due to different experimental conditions. For example, we evaluated the changes of ChIP-seq results after using antibodies from different companies (Fig. S10).

Statistical comparison of two correlation functions

After correlation functions, associated errors, and confidence intervals have been computed, two functions can be compared according to standard statistical tests. An R-script that uses a t-test to assess the difference between two functions for each shift distance Δx (Fig. S8 G) is included in the Supporting Material.

Quantification of MCORE correlation functions

Correlation functions obtained by MCORE provide information on the overall degree of (anti)correlation between two deep sequencing data sets but also reflect the underlying chromatin domain structure with respect to 1) the number of chromatin domains, 2) the relative domain abundance, 3) the length of the respective domains, and 4) the nucleosome repeat length. To extract the domain size distribution of a given chromatin feature, two different strategies were implemented in MCORE, which differ in the level of complexity but yield similar information. The first approach is independent of user-defined settings and computes parameters for the domain size distribution from the inflection points of the correlation function in logarithmic representation and a Gardner transformation of the correlation function. The Gardner transformation characterizes the decay spectrum of a function in a nonparametric manner (37). This workflow represents a robust approach to evaluate genomewide features from deep sequencing data without input parameters. In particular, inflection points are completely model-independent, whereas the Gardner spectrum makes the generic assumption that the decay spectrum can be approximated by a superposition of exponential functions. The second approach can be used to quantitatively describe the domain size distribution based on a fit function. For this purpose, it is crucial to avoid overfitting of the data. Accordingly, we implemented a complementary set of four fit options that allow for an in-depth analysis of correlation functions reporting fit parameters and their errors, thus determining domain sizes and their relative abundance. The performance of the different fit approaches is described below and in the MCORE software manual. The workflow we used in this article is validated with simulated data in Fig. S7.

Least-squares spectrum fit

The exponential decay spectrum for the correlation function is optimized by conventional nonlinear least-squares fitting. The amplitudes for a given number of (logarithmically spaced) domains are optimized to obtain a good fit. The goal of the spectrum fitting process is to determine the length scales that are present in the decay spectrum of the curve. To this end, it is not always necessary to exactly describe the shape of the correlation function. For example, the initial decay of the function is frequently too steep to be adequately fitted with a superposition of exponential functions. Nevertheless, decay lengths are typically obtained in a reliable manner. The multiexponential fit described below often performs equally well in identifying length scales and provides a good description of the correlation function. Thus, the least-squares spectrum fit is only recommended if the multiexponential fit does not converge properly, i.e., if it yields length scales that are very different from those determined by the analysis of inflection points.

Maximum entropy method spectrum fit

Here, the exponential decay spectrum is fitted similar to the least-squares method. However, the entropy of the amplitude spectrum is maximized along with the fit quality. To this end, optimization is carried out in a parameter space that is spanned by the first derivative of the entropy and the first and second derivatives of the fit quality according to the approach described in Skilling and Bryan (38). This fit option is only recommended if the number of components obtained from the least-squares spectrum fit is much larger than the number of inflection points.

Multiexponential fit implemented in MCORE

For multiexponential fitting, the following equation consisting of a combination of exponential functions is used:

| (6) |

The exponential terms describe the domain structure of the correlation function, with ai, bi, and ni yielding the relative abundance, the half-width, and the fuzziness of the ith domain, respectively. Small exponents ni correspond to long-tail decays in the domain size distribution.

Multiexponential fit in R

The multiexponential fit implemented in R (39) uses a sum of exponential functions (see Eq. 6) multiplied with an additional oscillatory term to describe the correlation function:

| (7) |

The oscillatory term accounts for the nucleosomal pattern, with parameters c1 for the strength of the nucleosomal oscillation, c2 representing the nucleosomal repeat length, and c3 the scale on which regular nucleosomal spacing is lost. When using this approach, the minimal number of exponential terms that yielded uncorrelated fit residuals was chosen.

MCORE running time

Generation of normalized occupancy profiles and calculation of the respective correlation function for the entire chromosome 1 takes 15–20 min on a laptop computer with a 2.7 GHz Intel Core i5 processor and 8 GB memory. For smaller chromosomes or genomic regions of interest, the calculation is faster.

Peak calling

Peak calling was done using MACS (10) and SICER (11). Before peak calling reads were preprocessed as described above, including mapping to the mouse mm9 assembly by Bowtie (32), considering only uniquely mapping reads without mismatches and removing duplicates. Peak calling was done using default parameters and the input as control file. For H3K36me3 MACS, mfold levels 5, 10, and 30 were tested, and mfold 5 was selected. For SICER, the FDR threshold was set to 0.0001, a window size of 200 bp and a gap size of 600 bp were used for H3K9me3 and H3K36me3, and a window size of 200 bp and a gap size of 200 bp were used for H3K4me3.

Network models

Graphs for network models were created and plotted using the software Gephi (http://gephi.org). Nodes were manually prearranged, and their layout was optimized using the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm (40), which adjusts node positions based on forces that act between nodes according to the respective correlation strength.

Sample preparation for histone ChIP-seq

ESCs and neural progenitor cells from 129P2/Ola mice were cultured and differentiated as published in Teif et al. (41). ChIP-seq experiments and mapping of reads to the mm9 assembly of the mouse genome was conducted as described in Müller-Ott et al. (22). In brief, 106 cells were cross linked with 1% PFA and cell nuclei were prepared. Chromatin was sheared by sonication to mononucleosomal fragments. ChIP was carried out with antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) against H3K4me1 (ab8895), H3K4me3 (ab8580), H3K9me3 (ab8898), H3K27ac (ab4729), H3K27me3 (ab6002), H3K36me3 (ab9050), or with a nonspecific IgG antibody (RA073 or PP500P, ACRIS, Herford, Germany) (Table S5). Libraries were prepared according to Illumina standard protocols with external barcodes and were sequenced with 51 bp single-end reads on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA). After sequencing, cluster imaging and base calling were conducted with the Illumina pipeline. A quantity of 20–30 Mio reads were obtained for each sample. Reads were uniquely mapped without mismatches to the mm9 mouse genome using the software Bowtie. For RNA-seq, cells were harvested and long RNAs were isolated with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), DNA was digested by DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI) for 30 min at 37°C, and libraries were prepared using the Encore Complete RNA-Seq Library Systems (NuGEN, Manchester, UK).

Data and software

ChIP-seq data are available in the GEO database with the accession number GSE61874. An executable Java program, including a test data set and an R script for statistical testing of the difference between two correlation functions, is available in the Supporting Material and can be downloaded at http://malone.bioquant.uni-heidelberg.de/software/mcore.

Results

Comparison of MCORE to other sequencing analysis workflows

The MCORE workflow in comparison to the currently most common approaches for deep sequencing analysis is illustrated in Figs. 1 and S2 A. First, all types of data sets were transformed into normalized read occupancy profiles. Among others, this normalization step takes into account the propensity of a DNA fragment to be ligated, amplified, sequenced, and mapped. To correct for these multiplicative biases, the sample read density was divided by the input read density for IP and Hi-C experiments or by the sum of converted and unconverted read densities for BS-seq. We expect that Hi-C data that have already been normalized with other methods (42, 43) can be used for MCORE without further correction. IP experiments such as ChIP-seq yielded significant background correlation due to nonspecific binding of DNA and proteins to beads or bead-antibody complexes (44). Accordingly, these data sets were further corrected by subtraction of a weighted control IP signal obtained from an IP with nonspecific antibodies (Fig. S2 B). The weighting factor reflects the contribution of nonspecifically precipitated DNA in each sample and removes the correlation between specific IP and control IP (see Materials and Methods). As expected, the contribution of nonspecific signal depended on the quality of the antibody and on the enrichment levels of the specific IP-signal. H3K9me3 ChIP-seq data, for example, were affected more strongly by this correction than H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data (Fig. S2 C), because H3K4me3 domains were more distinct and exhibited larger enrichment levels than H3K9me3 domains. Normalized occupancy profiles can be exported and be used for other downstream analysis methods.

Figure 1.

MCORE can identify and compare patterns in deep sequencing data sets. (A) MCORE is suited for the analysis of deep sequencing data from various methods. Initially, mapped reads are used to compute occupancy profiles of two samples (black, blue or gray). In the case of MCORE, the profiles are subsequently normalized using the input sample and, if applicable, the control sample. In contrast to other methods like peak calling, hidden Markov models (HMM) or dynamic Bayesian networks (DBN), which use control and IP samples for the detection of enriched regions, MCORE does not score enriched regions. Rather, the correlation functions of normalized occupancy profiles shifted with respect to each other are computed, which contain information about chromatin patterns as illustrated in (B) and (C) and Fig. S1. To this end, it uses all sequencing reads without filtering and avoids any assumptions about the enrichment pattern. (B) Correlation functions between replicates for the same chromatin feature contain information about its domain topology. Whereas the correlation coefficient at shift distance zero quantifies the reproducibility of the experiment, the shape of the function reflects the distribution of the feature along the genomic coordinate. Continuous domains lead to a steep decay at the shift distance that coincides with half the domain size λ (top), whereas broad domains containing small highly enriched regions yield multiple decay lengths λi (center). Arrays of equally spaced domains cause an oscillating contribution in the correlation function (bottom). Mixtures of domains with different topology yield a superposition of the respective correlation functions. (C) Correlation functions between two different chromatin features reflect their spatial relationship. Colocalizing features yield monotonously decaying functions (top) that resemble those between replicates discussed in the previous panel. Correlation functions for features that are shifted with respect to each other exhibit a local maximum at the shift distance d (center). Mutually exclusive features are recognized by negative correlation amplitudes (bottom). Features that do not exhibit any particular spatial relationship with respect to each other yield no correlation for any shift distance. To see this figure in color, go online.

Peak calling or dynamic network models use occupancy profiles from mapped reads to define peaks or chromatin states based on local enrichments (Fig. 1 A). In contrast, MCORE computes correlation functions from the sequencing read occupancy without binarizing the data. To this end, normalized occupancy profiles from two different data sets were shifted with respect to each other along the genomic coordinate, and the normalized Pearson correlation coefficient for each shifting distance Δx was calculated and analyzed (Materials and Methods). In contrast to rank correlations, the Pearson correlation coefficient accounts for the enrichment values within the normalized occupancy profile and therefore preserves the biologically relevant information (Fig. S3). We computed three types of correlation functions with different biological meaning: 1) the correlation function between two replicates, yielding the domain topology for a chromatin feature (Fig. 1 B); 2) the correlation function between the same feature in two different cell types, providing information on the positional conservation of a given chromatin mark across cell types (Fig. 1 C); and 3) the correlation function between two different features in the same cell type, reflecting their genomewide positional relationship such as colocalization or shifted localization (Fig. 1 C). The use of at least two independent data sets (either two replicates or two samples interrogating different features or cell types, see Eq. 4) for the calculation of each type of correlation function suppresses spurious noise that is uncorrelated between independent experiments and does not, therefore, contribute to the correlation.

To compare colocalization values among differently distributed marks, we normalized cross-correlation functions with respect to their replicate correlation (Materials and Methods, Eq. 5). This step was required because broadly distributed marks tended to yield smaller cross- and replicate correlation coefficients than marks forming narrow and well-positioned domains. As illustrated in Fig. 1 C, positive correlation indicated colocalization at a given shift distance, whereas negative correlation reflected mutually exclusive modification or binding. Each decay length and its contribution to the correlation function encoded a domain size and its abundance, whereas superimposed oscillations reflected nucleosome spacing (31, 41). Where necessary, the correlation function can be used as a starting point to identify individual regions of interest as described below.

MCORE is complementary to peak calling, which generally aims to identify enriched regions without larger gaps. As the probability to find modified regions without spurious gaps decreases with size, broad regions are prone to get lost or fragmented in such analyses. This phenomenon is more or less pronounced depending on the settings and the algorithm used as shown for H3K9me3 in Fig. S4 B. Further, it is often challenging to identify and remove false-positive/negative peaks that are caused by the inherent properties of sequencing data sets like noise, artificial overrepresentation of particular genomic regions (45, 46), or insufficient read coverage (15). An example for H3K36me3 is shown in Fig. S4 C. MCORE retrieves information about patterns upstream of peak calling analyses and is relatively robust toward uncertainties at individual loci because correlation functions are calculated from the entire collection of sequencing reads in a large genomic region (see Figs. S5 and S6 for the influence of read coverage).

Interpretation and quantification of correlation functions

We quantified the information contained in correlation functions by first analyzing their decay spectrum in a model-independent manner and by subsequently fitting a generic model function (29) as described in the Materials and Methods. This is illustrated for a simulated data set in Fig. S7. As a first step, inflection points (in logarithmic representation) were numerically determined, yielding the decay lengths that are present in the correlation function. Depending on the type of function these decay lengths λi represent domain sizes or separation distances (Fig. 1 C). Next, the Gardner transformation was computed, which exhibited peaks at the characteristic decay lengths (37). Both approaches were independent of input parameters or model assumptions. Finally, we fitted the correlation function to quantitatively describe the domain size spectrum (Materials and Methods). Because decay lengths and nucleosome repeat length follow from the change of the correlation coefficient with shift distance, these parameters are independent of the absolute correlation amplitude, which is beneficial for the analysis of data sets that are not properly normalized, e.g., due to low sequencing depth or lack of suitable control samples.

Correlation functions can be compared to each other based on errors obtained from Fisher transformation or bootstrapping (Fig. S8, Materials and Methods). These errors reflect variations of the correlation coefficient among different positions within the genomic region of interest. If more than two replicates were available, replicate correlation functions calculated for each combination of independent samples were combined to account for differences among experiments (Fig. S8). We found these errors most meaningful because the variability among replicates can typically not be neglected and should be used as a reference when comparing different correlation functions to each other. The shape and the amplitudes of correlation functions were well reproducible when normalized according to the workflow described above. This was also true when comparing our samples with published histone modification ChIP-seq samples from other labs (Figs. S8 C and S9 A).

In summary, MCORE yields compact genomewide representations of chromatin features in the form of correlation functions that can be quantitatively evaluated and compared to each other. It can be used to 1) determine domain topologies (Fig. 1 B); 2) assess positional relationships (Fig. 1 C); 3) test the reproducibility of experiments; or 4) assess variations caused by changes in experimental conditions, e.g., the use of antibodies from different suppliers (Fig. S10). In contrast to the Pearson correlation coefficient between two data sets alone, the normalized correlation function provides insight into the similarity of the data sets on a broad range of length scales. Thus, MCORE can detect changes in domain size, amplitude, or relative genomic position and can be used to track the reorganization of the epigenome among different cell types as shown below.

Domain structure and nucleosome pattern of modified regions in ESCs and NCs

We used replicate correlation functions to dissect the domain structures and nucleosome patterns in ESCs and NCs throughout the genome (Figs. 2, A and B, and S11; Tables S3 and S4). These quantities reflect the activity of the cellular machinery that shapes the chromatin landscape and thereby regulates chromatin function. Most features studied here, such as H3K9me3, displayed complex domain size distributions with multiple characteristic decay lengths (Fig. 2, A and B). An exception was H3K4me3, which formed almost exclusively distinct peaks of roughly 1900 bp or 9–10 nucleosomes in size in both ESCs and NCs in agreement with published data (47). For H3K36me3, we found a typical domain size of 24–30 kb, which is of the same order of magnitude as the average gene length in the mouse genome (according to NCBI Build 37, mm9). The nucleosome repeat length varied among domains carrying different histone modifications, with 218 bp for H3K27me3 in NCs and 182 bp for H3K9me3 and H3K36me3 in NCs (Tables S3 and S4). This observation suggests that nucleosome spacing is differentially regulated and linked to the chromatin state, consistent with previous reports (31, 48).

The initial decay of most replicate correlation functions is caused by the reduced probability to find the same modification at the neighboring nucleosome and is therefore associated with a domain size of a single nucleosome. Notably, a prerequisite for this interpretation is that the occupancy profile is properly normalized and not heavily undersampled, which is validated for representative profiles in Figs. S5 and S6. Accordingly, homogenous domains that primarily contain equally modified nucleosomes produce a weaker initial decay than domains that contain a mixture of modified and nonmodified or differently modified nucleosomes. Whereas the subtle initial decay for H3K4me3 in ESCs and NCs (Fig. 2, A and B; Tables S3 and S4) is indicative of homogenous domains, the pronounced decay for H3K9me3 in NCs (Fig. 2 B; Table S4) suggests that this modification forms discontinuous domains with gaps. This is corroborated by the absence of isolated nucleosomes with high H3K9me3 enrichment levels outside broader domains (Fig. S12), which could also be responsible for a steep decay in the correlation function because such nucleosomes would have unmethylated neighbors.

In summary, these results reveal the link between different histone modifications and their domain sizes and frequency distributions. Based on these parameters, an assignment to specific genomic loci can be made, e.g., by evaluating the normalized occupancy profiles with a sliding window corresponding to a domain size of interest. This procedure is illustrated in Figs. 2 C and S13 for broad H3K9me3 domains, which, according to MCORE, prevailed in NCs.

Changes in chromatin patterns during stem cell differentiation

To identify changes of chromatin features during stem cell differentiation, we conducted a comparative MCORE analysis of more than 60 deep sequencing data sets from ChIP-seq (histone modifications: H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9me3, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, H3K36me3, binding sites of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II), and transcription factors TAF3, Oct4, and Otx2), BS-seq, RNA-seq, Hi-C, and RNAP II ChIA-PET experiments in ESCs and NCs (Figs. 2, 3, and S14–S17; Tables S2 and S5). Normalized correlation amplitudes at zero shift distance were assembled into a matrix (Fig. 3 A, red/blue), reflecting colocalization or mutually exclusive localization of different features. In both cell types, we found more colocalizations than mutual exclusions, which suggests that the set of chromatin features analyzed here tends to localize to the same part of the genome. In general, mutual exclusions were weaker than colocalizations as judged by the absolute values of the respective normalized correlation coefficients.

Figure 3.

MCORE reveals genomewide relationships between chromatin features. (A) Colocalization (top, red/blue) and separation distance (shift distance for the largest local maximum, bottom, green) between pairs of different features in ESCs (left) and NCs (right) are shown. (Stars) Correlation functions for which the local maximum is also the global maximum (Hi-C trans, Hi-C interchromosomal contacts; RNA, RNA-seq; RNAP II-ChIA, RNAP II ChIA-PET). (B) Correlation functions for replicates of H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and interchromosomal contacts (Hi-C trans) in ESCs (blue) and NCs (black) show the spatial extension of these features. Average cross-correlation functions (red) between ESCs and NCs quantify the colocalization of a given feature across cell types. Averages were calculated from the four possible combinations of the two replicates for each sample (Materials and Methods). Error bars, mean ± SE. (C) Cross correlations between H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 (top) or H3K9me3/H3K27me3 and interchromosomal contact sites (Hi-C trans, center/bottom) in ESCs and NCs. Repressive domains colocalize in NCs (top) and have a tendency to be depleted for interchromosomal contacts (bottom). Error bars, mean ± SE. (D) Cross correlations between H3K4me3 and H3K27ac (top) indicate colocalization of both marks in small domains, whereas cross correlations of H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 (center) reveal a relative displacement of roughly 5 kb between these two marks. Cross correlations between H3K4me1 and H3K9me3 (bottom) show that both marks are more strongly colocalized in NCs than in ESCs. The broad local maximum around 100 kb shift distance in ESCs suggests a separation of H3K4me1 from broad H3K9me3 domains. Error bars, mean ± SE. (E) Peak calling in NCs as readout for colocalization. (Red) Peaks called by MACS for H3K4me3; (blue) peaks called by SICER for H3K36me3 or by MACS for H3K27ac. The numbers of (overlapping) peaks are indicated. (F) Distribution of distances between called peaks. Distances were calculated from the center of the H3K4me3 peak to the center of the nearest peak in the second data set (H3K27ac or H3K36me3).

In ESCs, the strongest colocalizations were found among features related to actively transcribed genes (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K36me3, RNAP II, and RNAP II ChIA-PET). Notably, H3K36me3, which is known to be associated with active genes, also colocalized with H3K9me3/H3K27me3, which are traditionally considered heterochromatin marks. This might reflect 1) the presence of repressed genes not devoid of H3K36me3 (49), 2) the occurrence of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 at active genes (47), and/or 3) the presence of H3K36me3 domains outside of coding genes. Mutual exclusion was found between RNAP II and the repressive marks H3K27me3 and 5mC (but not H3K9me3) in ESCs. Furthermore, interchromosomal contact sites were depleted around H3K27me3 in ESCs, indicating that H3K27me3 domains localized preferentially inside chromosome territories.

In NCs, colocalization among features associated with active chromatin was conserved and tended to become stronger (Fig. 3 A). Most activating modifications retained their domain size structures and genomic positions on a global level (Fig. S15). In contrast, H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 redistributed during differentiation in a way that their colocalization with each other, with 5mC and with some of the activating marks like H3K4me1, increased (Figs. 3, A and D, and S16). In particular, the following changes are noteworthy: 1) Both H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 formed broader domains in NCs compared to ESCs, which led to a stretched decay in correlation functions for NCs compared to the steeper decays in correlation functions for ESCs (Figs. 2, A and B, and 3 B). 2) The normalized correlation of H3K9me3 between ESCs and NCs decreased compared to the normalized correlation between replicates from the same cell type (Fig. 3 B). The same tendency was observed for H3K27me3. These differences suggest partial relocation of H3K9me3/H3K27me3 during differentiation. Otherwise correlation functions between ESCs and NCs would resemble the correlation function calculated for the replicates from the same cell type, and all curves in each panel would essentially be identical. 3) The normalized correlation between H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 increased in NCs (Fig. 3 C), which is indicative of stronger colocalization of both marks in NCs. 4) Correlation functions for 5mC in ESCs, NCs, and between both cell types were similar (Fig. S15). Thus, global changes in the genomewide 5mC pattern were minor, consistent with previous findings (47). 5) The normalized correlation between H3K27me3 and 5mC was higher in NCs compared to ESCs (Figs. 3 A and S17 A), suggesting relocalization of H3K27me3 to 5mC domains. Normalized correlation between H3K9me3 and 5mC increased for large shift distances in NCs, implying that extended H3K9me3 domains formed in the vicinity of preexisting 5mC sites (Fig. S17 A). 6) Substantial mutual exclusion was found between H3K9me3 and interchromosomal contacts in NCs but not in ESCs, indicating that H3K9me3 was relocalized to the interior part of chromosome territories (Fig. 3 C). H3K27me3 resided preferentially inside chromosome territories already in ESCs and did not change its position in NCs (Fig. 3 C).

Differential relationships among chromatin features in ESCs and NCs

Next, we determined the characteristic genomic separation distance for each pair of features (Fig. 3 A, green color-coding). Whereas correlation functions for colocalizing features tend to decrease monotonously, correlation functions for shifted features exhibit local maxima at their characteristic separation distance (Fig. 1 C). Correlation functions for features that colocalize at some regions in the genome and are shifted with respect to each other at other places exhibit an initial decay that is followed by local maxima (Fig. 3, C and D). This type of information is lost in evaluation schemes that exclusively assess overlap (Fig. 3 E). For simple cases, such as H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 that localize side by side at promoters and bodies of active genes (Fig. S4), similar information is obtained by determining distances between adjacent peaks across data sets (compare Fig. 3, D and F).

Examples for pairs of features that are shifted with respect to each other in ESCs but overlap and colocalize in NCs are H3K4me1-H3K9me3 (Fig. 3, A and D), H3K4me3-H3K27me3, and H3K9me3-H3K27ac (Fig. 3 A). These changes are consistent with the global reorganization of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 in NCs described above.

Network models for relationships among chromatin features on multiple scales

The cross-correlation functions introduced above represent the scale-dependent relationships between pairs of chromatin features. Accordingly, we used these values to construct network models that reflect the associations among all features assessed here for a particular genomic distance (Fig. 4). Features were arranged based on their associations at zero shift distance, with positively correlated features positioned close to each other (Materials and Methods). As described above, activating histone modifications such as H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac colocalized with RNAP II and RNAP II ChIA-PET sites in both ESCs and NCs. Repressive marks including H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and 5mC were also positively associated with each other, with stronger correlations in NCs than in ESCs. This observation suggests that in NCs a larger fraction of the genome is heterochromatic. H3K36me3 exhibited positive correlations with both activating and repressive marks, indicating partial overlap of the respective domains. Associations among different features changed in a characteristic manner with genomic distance, reflecting the mechanisms that establish chromatin patterns on different scales. Activating features remained associated with the adjacent nucleosome (200 bp shift), indicative of chromatin domains that extend beyond a single nucleosome. In contrast, the cross correlation among repressive marks at neighboring nucleosomes decreased considerably compared to their correlation at the same nucleosome. This points to the presence of nucleosomes (without an equally modified neighbor) that either carry at least two repressive marks simultaneously, display a transition between two different repressive marks over time, or stably carry different repressive marks in different cells. All of these scenarios would produce positive correlation in the ensemble average. At a shift distance of ∼10 nucleosomes (2000 bp), most associations among activating histone modifications were lost, reflecting the relatively limited spatial extension of the respective domains (Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 4.

Network models for scale-dependent relationships among chromatin features. (A) Network models illustrating the relationships among different chromatin features in ESCs on different scales (blue and red in the color version of this figure denote positive and negative correlation, respectively). Features were grouped according to their correlation at zero shift distance (left), yielding a cluster of features associated with active transcription and a cluster of marks related to gene silencing, whereas H3K36me3 colocalizes with members of both groups. The correlations among features on adjacent nucleosomes (200 bp shift distance) differ from the correlations among features at the same nucleosome (0 bp shift distance), indicating that only some features form continuous domains that extend beyond a single nucleosome. For the even larger shift distance of roughly 10 nucleosomes (2000 bp), only a few long-range correlations remain, which either reflect large domains of colocalizing features or features that are shifted with respect to each other. The latter two possibilities can be distinguished based on the shape of the correlation function (Fig. 1C). (B) Same as in (A) but for NCs. (C) Network models illustrating changing relationships among different chromatin features in ESCs and NCs. In the color version of this figure, the difference NC-ESC is depicted in blue if correlations became stronger in NCs and in red if correlations became weaker in NCs. To see this figure in color, go online.

Reorganization of heterochromatin components

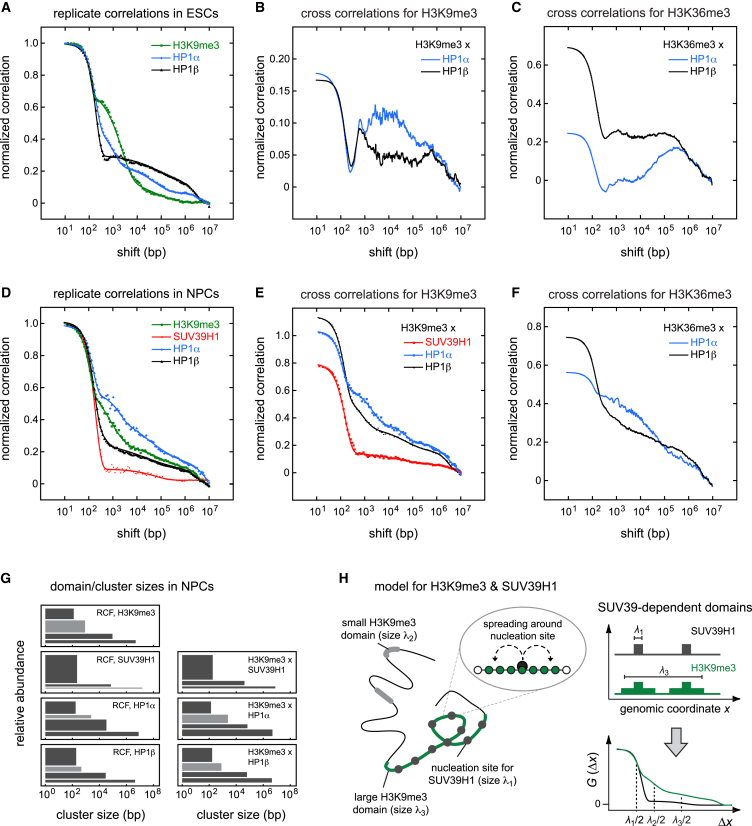

To further investigate the changes in heterochromatin organization during differentiation of ESCs into NCs inferred from the MCORE analysis above, we dissected the core part of the network around H3K9me3. To this end, we compared the distributions of the H3K9me3 mark, the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 that sets this mark in pericentric heterochromatin, and the heterochromatin protein 1 isoforms HP1α and HP1β to each other. Both SUV39H1 and HP1 contain chromodomains that recognize H3K9me3, but the contribution of these interactions to their genomewide binding profiles has not been studied comprehensively. First, we asked if the two HP1 isoforms displayed cell type-specific chromatin interaction patterns. We found that the genomic distributions of HP1α and HP1β were different from each other in both ESCs (Fig. 5, A–C) and NCs (Fig. 5, D–F). In ESCs, HP1β formed broader domains than HP1α (Fig. 5 A) that were less correlated with H3K9me3 (Fig. 5 B) but rather overlapped with H3K36me3 (Fig. 5 C). This finding supports recent work, which showed that HP1β but not HP1α is enriched in exons and essential for proper differentiation and maintenance of pluripotency in ESCs (50). The nuclear distribution of HP1β in ESCs might be related to its function in splicing (51). In NCs, HP1α and HP1β displayed moderate differences in their domain structure (Fig. 5, D and G), with a stronger preference of HP1α for broad domains. In contrast to ESCs, both isoforms strongly colocalized with H3K9me3 in NCs (Fig. 5 E), in line with their well-established role as heterochromatin components in differentiated cells (Müller-Ott et al. (22) and references therein). Colocalization with H3K36me3 was also observed (Fig. 5 F), consistent with the overlap between H3K9me3 and H3K36me3 domains in NCs found above. Next, we focused on the composition of H3K9me3 domains in NCs. Whereas H3K9me3 formed both broad and intermediately sized domains, SUV39H1 did not form intermediate domains but rather broad domains containing gaps (Fig. 5, D and G), as suggested by the fast decay of its replicate correlation function (Fig. 5 D, red). Consistently, colocalization among HP1α/β, SUV39H1, and H3K9me3 was not found in intermediate but rather in broad domains (Fig. 5 E). These findings point to the presence of SUV39H1-independent H3K9me3 domains with intermediate size in NCs, which have also been described in ESCs (52), indicating that H3K9me3 is not sufficient for stably recruiting SUV39H1 to chromatin. This is in line with a looping model in which well-separated high-affinity binding sites (nucleation sites), which reside within broad heterochromatic regions, recruit SUV39H1 to establish and maintain H3K9me3 (Fig. 5 H).

Figure 5.

Interplay among H3K9me3, SUV39H1, and HP1. (A) Replicate correlation functions of HP1α (blue or light gray), HP1β (black), and H3K9me3 (green or dark gray) in ESCs. (B) Cross-correlation functions of HP1α (blue or gray) or HP1β (black) with H3K9me3 in ESCs. (C) Cross-correlation functions of HP1α (blue or gray) or HP1β (black) with H3K36me3 in ESCs. (D) Same as in (A) but for NPCs and including SUV39H1. H3K9me3 and HP1α/β exhibit small, intermediate, and broad domains. The small domain size of one nucleosome is present in the correlation functions for all marks, suggesting that domains consist of enriched sites and gaps as explained in the text. SUV39H1 does not form intermediately sized domains. (E) Same as in (B) but for NCs and including SUV39H1. SUV39H1, HP1α, HP1β, and H3K9me3 strongly colocalized. Intermediate domains are not present in the cross-correlation function between SUV39H1and H3K9me3, indicating that both features only colocalize in short and broad domains. In contrast, HP1α and HP1β essentially follow the H3K9me3 distribution, indicating that they do not distinguish between differently sized H3K9me3 domains. (F) Same as in (C) but for NCs. (G) Domain size distribution for correlation functions in (D) and (E). (H) Schematic illustration of a nucleation-and-looping mechanism for the formation of SUV39H1-dependent H3K9me3 domains, which is consistent with the MCORE results for NPCs. To see this figure in color, go online.

Model for changes of chromatin features during differentiation

The MCORE results on domain size distributions, colocalizations, and separation distances (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4) lead us to propose the model for the reorganization of chromatin during differentiation of ESCs into NCs depicted in Fig. 6. H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 domains became larger and more strongly colocalized with sites of preexisting 5mC during the transition from ESCs to NCs (Figs. 3, B and C, and S17 A). This rearrangement leads to several alterations in the relationships between H3K9me3/H3K27me3/5mC and other chromatin features in NCs: 1) H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 colocalized stronger with active marks including H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and RNAP II as well as H3K36me3 (Figs. 3 A and 4). 2) 5mC colocalized somewhat more strongly with H3K36me3 (Figs. 3 A and S17 A). 3) Whereas 5mC and H3K27me3 were already depleted from the surface of the chromosome territory in ESCs (Figs. 3 C and S17 B), H3K9me3 moved into the interior of the territory in NCs (Fig. 3 C). The positive correlations between H3K4me1-H3K27me3 and H3K4me1-H3K9me3 remained stronger in NCs than in ESCs on larger genomic scales up to 10 nucleosomes (Figs. 3 D, 4 C, and S16), indicating that they are caused by NC-specific broad domains. In summary, these findings suggest that the main chromatin transition during differentiation from ESCs into NCs is the rearrangement of H3K9me3/H3K27me3 domains, which in NCs extend beyond repressive heterochromatin and overlap at least to some extent with chromatin regions that carry activating histone marks.

Figure 6.

Alterations of chromatin features during differentiation of ESCs into NCs. A model for the reorganization of chromatin domains during differentiation from ESCs to NCs is shown, which is based on the MCORE analysis of the data sets used in this study. Active domains mostly retained their organization, with H3K4me1 being partly separated from the smaller H3K4me3/H3K27ac domains in both cell types. The overlap between those marks and H3K36me3 increased in NCs, which might be due to the activation of genes overlapping with H3K4me1/3 or H3K27ac. Domains enriched for H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 became extended at sites of 5mC and were preferentially buried inside chromosome territories. The newly established H3K9me3/H3K27me3 domains in NCs appeared discontinuous, i.e., contained many modified nucleosomes without an equally modified neighbor. Further, they exhibited increased overlap with activating marks such as H3K4me1 and H3K4me3, which suggests that they do not exclusively contain heterochromatin but rather enclose both active and repressive chromatin domains. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Quantitative descriptions of cell-type-specific chromatin states are important for the mechanistic understanding of all processes that require access to the genetic information. While the effects of soluble enzymes can be represented by simple rate equations, the polymeric nature of chromatin introduces a spatial relationship among nucleosome states. Thus, nucleosomes are influenced by the adjacent chromatin segments and patterns that can form along the genomic coordinate. These patterns are present on different length scales and represent an extra layer of complexity, which is an essential part of the regulatory networks that control genome functions. For example, repressive histone modifications form broad domains that are relatively independent from the underlying DNA sequence and can be transmitted through at least several cell divisions (22, 53, 54, 55). Furthermore, chromosomes fold into topological domains that determine the contact frequencies between genomic loci and the proteins they are decorated with (56), thereby creating three-dimensional structural patterns that might be relevant for long-range gene regulation. Elucidating the mechanistic basis of these phenomena and the functional relationships among them requires techniques that can identify, quantitate, and compare different patterns along the genome.

Global analysis of deep sequencing data by correlation functions

The analysis of deep sequencing data on the level of individual genomic positions is complicated by noise, bias, and undersampling (15, 16, 17). It is often not straightforward to choose a threshold value for classifying enriched regions because low values lead to false-positive peaks and high values lead to false-negative results. Consequently, identifying differences in the chromatin domain landscape between samples is currently fraught with difficulties, which is evident from a comparison of 14 different software tools for differential ChIP-seq analysis that yield different results (57). These problems are especially detrimental for the analysis of broad regions with low enrichment levels that are common to heterochromatin.

The MCORE method introduced here uses correlation functions to find and quantify chromatin patterns. It computes Pearson correlation coefficients as underlying metrics, which is a convenient measure used for data comparison and statistical inference in many fields including deep sequencing analysis (18, 30, 31, 58). When calculating correlation functions, MCORE implicitly combines multiple genomic regions to gain a correlation coefficient for each shift distance, yielding statistical robustness from a large number of reads. In this manner MCORE can quickly retrieve information on the spatial distribution of chromatin features on all length scales, while avoiding assumptions or model-dependent parameter settings like significance thresholds. In contrast to aggregate plots (59, 60, 61) MCORE does not rely on any a priori knowledge about annotated genomic elements. Compared to peak calling (15), MCORE has a relatively low sensitivity to undersampling. This might be beneficial for the analysis of data sets that have low complexity, e.g., due to limitations in input material as it is the case for low input sequencing samples, or insufficient sequencing depth, which seems to be the norm for broadly distributed histone modifications (15). Domain abundances obtained from data sets with different coverage values exhibited somewhat larger changes than domain sizes. Therefore, sufficient coverage should be ensured to interpret these parameters, e.g., by applying MCORE to diluted data as shown in Figs. S5 and S6.

A crucial step in the MCORE workflow is correction for bias and background. Without this step, artificially overrepresented regions and nonspecific signals can induce similarities between data sets that are unrelated to the chromatin feature of interest. These phenomena are well known from other deep sequencing analysis methods. Because different artifacts affect the signal on different scales, their contribution and successful correction can better be assessed by multiscale methods than by techniques that operate on a single scale. Nonspecific background leads to a characteristic correlation spectrum whose removal can and should be validated using the proper controls. Based on a single correlation coefficient between data sets, this task is more difficult to accomplish. Occupancy profiles that have been normalized according to the workflow presented here might serve as a useful resource for other downstream analysis methods.

Genomewide topology of chromatin domains

MCORE extends previous techniques that assess colocalizations of chromatin features based on correlation coefficients. By evaluating entire correlation functions instead of single correlation coefficients, the spatial extension of chromatin patterns on multiple genomic scales is retrieved. With this analysis, we found predominantly small domain sizes of <2 kb for promoter/enhancer marks H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and RNAP II, intermediate domain sizes of 20–30 kb for H3K36me3 that marks the whole gene body including flanking regions, and domain sizes up to several megabases for H3K9me3/H3K27me3. This is consistent with the size of promoters, enhancers, and active genes, and with the estimates for repressive domains that were made based on visual inspection of selected genomic regions (62).

The scale-dependent relationships determined by MCORE for different histone modifications suggest that there are three types of domain topologies: 1) Short domains formed by activating marks are relatively homogenously modified, which is reflected by a large probability for finding the same or another activating modification at the next nucleosome. Accordingly, correlation functions for activating marks such as H3K4me3 displayed only a moderate initial decay (Fig. 2). 2) H3K36me3 formed domains of intermediate size that were 1–2 orders-of-magnitude broader than H3K4me3 domains. The stronger initial decay (Fig. 2) suggests the presence of single nucleosomes without an equally modified neighbor, which is consistent with the presence of more gaps in H3K36me3 domains as compared to H3K4me3 domains. 3) Especially in NCs, replicate correlation functions for H3K9me3 or H3K27me3 displayed long-range correlations that extended to shift distances of several megabases. Similar scale-dependence was also seen for correlation functions between H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 (Fig. 3 C), suggesting that these domains are intermingled. The respective correlation functions displayed a relatively fast decay at a shift distance of one nucleosome (Figs. 2 and 3), indicating that many modified nucleosomes within these broad domains localize next to an unmodified or differently modified one. Such a domain structure fits well to the experimental observation of broad domains and low enrichment levels in the cell ensemble. The experimentally determined methylation levels that are <50% even for H3K9me3 in pericentric heterochromatin (see Müller-Ott et al. (22) and references therein) are incompatible with large genomic regions containing exclusively fully H3K9me3-modified nucleosomes. Broad H3K9me3/H3K27me3 domains with gaps are consistent with a model in which methylation marks are stochastically propagated from well-positioned nucleation sites via dynamic chromatin looping (22, 63).

Comparison of chromatin domains in ESCs versus NCs

The comparative analysis of 11 different chromatin features in ESCs and NCs conducted here shows that MCORE can efficiently identify and compare chromatin domain patterns. By integrating genomewide data sets with very different readouts, MCORE is well suited to generate hypotheses that can be further validated in downstream applications.

The positive correlations we found among activating histone modifications (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K36me3), among repressive histone modifications (H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and 5mC), and between H3K36me3 and repressive marks are in qualitative agreement with previous studies conducted with ESCs and other cell types (62, 64, 65). Genomewide colocalization of marks that were originally thought to affect transcription antagonistically might reflect the additional functions of these marks that are unrelated to the regulation of gene expression. For example, H3K9me3 is not restricted to heterochromatin but is also found at some active genes (47, 66). Furthermore, H3K9me3, H3K27me3, and H3K36me3 have been linked to alternative splicing (51, 67) and large portions of H3K9me3 and H3K27me3 localize to intergenic regions where they might serve completely different functions (64). Because sequencing data reflect the average of the cell population that was analyzed, positive correlations might also arise from gene loci carrying different marks during different cell cycle stages, alleles within the same cell carrying different marks, or loci carrying different marks in different cells. The finding that correlations were generally smaller in ESCs than in NCs fits to the model of plastic and hyperactive chromatin in stem cells, which acquires distinct patterns only upon differentiation (68). The fact that most 5mC regions persisted in ESCs and NCs, were moderately depleted for interchromosomal contacts in both cell types, and gained H3K9me3 in NCs, suggests a model in which heterochromatic regions newly established in NCs are preferentially buried within chromosome territories (Fig. 6). H3K27me3 domains behaved similarly in both cell types, which fits very well to the previously reported localization of inactive domains such as the Hox cluster inside chromosome territories in differentiated cells (13, 69, 70, 71). The observation that only a subset of H3K9me3 domains is broad and enriched for SUV39H1 suggests that heterochromatin extension is not merely caused by recruitment of trans-acting enzymes to preexisting H3K9me3 but rather by site-specific recruitment of methyltransferases to domains that are to be extended during differentiation. Although further experiments are required to fully understand the underlying molecular details of heterochromatin reorganization during differentiation, these insights provide a starting point to uncover the pathways that are responsible for establishing differently sized heterochromatin domains with distinct molecular composition.

Conclusion

The MCORE method introduced here enables the quantitative retrieval and comparison of patterns and spatial relationships for different chromatin features from noisy data sets. These features make MCORE complementary to model-dependent approaches that assess the local read density at individual loci to find enriched regions. MCORE is relatively fast and yields a coarse-grained comparison of data sets without the requirement of user-defined input parameters, providing an unbiased starting point for in-depth analyses conducted downstream. We anticipate that MCORE will aid in the design and validation of mechanistic models for chromatin patterning and long-range gene regulation.

Author Contributions

F.E. and K.R. designed research; J.M. and F.E. performed the theoretical work; all authors analyzed and interpreted the data; J.M. and J.-P.M. performed the experiments; and the article was written by F.E., J.M., and K.R.

Acknowledgments

We thank Caroline Bauer for valuable assistance, the DKFZ Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility for technical support and expertise, and Anne Rademacher, Katharina Müller-Ott, and Daniel Duzdevich for comments on the article.

This work was supported by grant No. CA146 of the Cancer Research Cooperation Program between the DKFZ and the Israel Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), the projects ImmunoQuant (grant No. 0316170B) and PRECiSe (grant No. 031L0076A) of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), as well as a DKFZ intramural grant to F.E.

Editor: Tamar Schlick.

Footnotes

Seventeen figures, five tables and nine data files are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30032-2.

Contributor Information

Karsten Rippe, Email: karsten.rippe@dkfz.de.

Fabian Erdel, Email: f.erdel@dkfz.de.

Supporting Citations

References (72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Zhou V.W., Goren A., Bernstein B.E. Charting histone modifications and the functional organization of mammalian genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrg2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polo S.E., Jackson S.P. Dynamics of DNA damage response proteins at DNA breaks: a focus on protein modifications. Genes Dev. 2011;25:409–433. doi: 10.1101/gad.2021311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagano T., Lubling Y., Fraser P. Single-cell Hi-C reveals cell-to-cell variability in chromosome structure. Nature. 2013;502:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro E., Biezuner T., Linnarsson S. Single-cell sequencing-based technologies will revolutionize whole-organism science. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14:618–630. doi: 10.1038/nrg3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartzman O., Tanay A. Single-cell epigenomics: techniques and emerging applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015;16:716–726. doi: 10.1038/nrg3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chabbert C.D., Adjalley S.H., Steinmetz L.M. A high-throughput ChIP-Seq for large-scale chromatin studies. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015;11:777. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poorey K., Viswanathan R., Auble D.T. Measuring chromatin interaction dynamics on the second time scale at single-copy genes. Science. 2013;342:369–372. doi: 10.1126/science.1242369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortini R., Barbi M., Victor J.M. The physics of epigenetics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016;88:025002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barski A., Cuddapah S., Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y., Liu T., Liu X.S. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zang C., Schones D.E., Peng W. A clustering approach for identification of enriched domains from histone modification ChIP-Seq data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1952–1958. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman M.M., Ernst J., Noble W.S. Integrative annotation of chromatin elements from ENCODE data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:827–841. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bickmore W.A., van Steensel B. Genome architecture: domain organization of interphase chromosomes. Cell. 2013;152:1270–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zacher B., Lidschreiber M., Tresch A. Annotation of genomics data using bidirectional hidden Markov models unveils variations in Pol II transcription cycle. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014;10:768. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung Y.L., Luquette L.J., Park P.J. Impact of sequencing depth in ChIP-seq experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer C.A., Liu X.S. Identifying and mitigating bias in next-generation sequencing methods for chromatin biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nrg3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sims D., Sudbery I., Ponting C.P. Sequencing depth and coverage: key considerations in genomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrg3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landt S.G., Marinov G.K., Snyder M. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Res. 2012;22:1813–1831. doi: 10.1101/gr.136184.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szalkowski A.M., Schmid C.D. Rapid innovation in ChIP-seq peak-calling algorithms is outdistancing benchmarking efforts. Brief. Bioinform. 2011;12:626–633. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pauler F.M., Sloane M.A., Barlow D.P. H3K27me3 forms BLOCs over silent genes and intergenic regions and specifies a histone banding pattern on a mouse autosomal chromosome. Genome Res. 2009;19:221–233. doi: 10.1101/gr.080861.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filion G.J., van Steensel B. Reassessing the abundance of H3K9me2 chromatin domains in embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:4. doi: 10.1038/ng0110-4. author reply 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller-Ott K., Erdel F., Rippe K. Specificity, propagation, and memory of pericentric heterochromatin. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014;10:746. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodges C., Crabtree G.R. Dynamics of inherently bounded histone modification domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13296–13301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211172109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erdel F., Greene E.C. Generalized nucleation and looping model for epigenetic memory of histone modifications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E4180–E4189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605862113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wochner P., Gutt C., Dosch H. X-ray cross correlation analysis uncovers hidden local symmetries in disordered matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11511–11514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905337106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baum M., Erdel F., Rippe K. Retrieving the intracellular topology from multi-scale protein mobility mapping in living cells. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4494. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Podobnik B., Horvatic D., Stanley H.E. Cross-correlations between volume change and price change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:22079–22084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911983106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elson E.L. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: past, present, future. Biophys. J. 2011;101:2855–2870. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sengupta P., Jovanovic-Talisman T., Lippincott-Schwartz J. Probing protein heterogeneity in the plasma membrane using PALM and pair correlation analysis. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:969–975. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kharchenko P.V., Tolstorukov M.Y., Park P.J. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1351–1359. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanton K.P., Parisi F., Kluger Y. Arpeggio: harmonic compression of ChIP-seq data reveals protein-chromatin interaction signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e161. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langmead B., Trapnell C., Salzberg S.L. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schätzel K. Noise on photon correlation data: I. Autocorrelation functions. Quantum Opt. 1990;2:287–305. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher R.A. Frequency distribution of the values of the correlation coefficient in samples of an indefinitely large population. Biometrika. 1915;10:507–521. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher R.A. On the ‘probable error’ of a coefficient of correlation deduced from a small sample. Metron. 1921;1:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Efron B., Tibshirani R.J. Chapman & Hall; Boca Raton, FL: 1993. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gardner D.G., Gardner J.C., Meinke W.W. Method for the analysis of multicomponent exponential decay curves. J. Chem. Phys. 1959;31:978–986. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skilling J., Bryan R.K. Maximum entropy image reconstruction: general algorithm. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1984;211:111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Team R.C. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fruchterman T.M.J., Reingold E.M. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw. Pract. Exper. 1991;21:1129–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teif V.B., Vainshtein Y., Rippe K. Genome-wide nucleosome positioning during embryonic stem cell development. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:1185–1192. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yaffe E., Tanay A. Probabilistic modeling of Hi-C contact maps eliminates systematic biases to characterize global chromosomal architecture. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1059–1065. doi: 10.1038/ng.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Imakaev M., Fudenberg G., Mirny L.A. Iterative correction of Hi-C data reveals hallmarks of chromosome organization. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:999–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marinov G.K., Kundaje A., Wold B.J. Large-scale quality analysis of published ChIP-seq data. G3. 2014;4:209–223. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.008680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jain D., Baldi S., Becker P.B. Active promoters give rise to false positive ‘phantom peaks’ in ChIP-seq experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6959–6968. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]