Abstract

Three major sources of financial support for the research undertaken by Edwards, Steptoe and Purdy between 1969 and 1978 are identified: the Ford Foundation, Oldham and District General Hospital (ODGH) Management Committee, and Miss Lillian Lincoln Howell via the American Friends of Cambridge University. Significant possible financial support from the World Health Organization was also identified. In addition, evidence of support in kind from GD Searle and Co. plus staff at ODGH was found. Expenditure on salaries of staff at Oldham was negligible, as most volunteered their time outside of their official paid duties. Work in Cambridge was evidently funded largely from Ford Foundation grants, as was Edwards' salary and probably that of Purdy. Clinical costs seem to have been largely borne by ODGH. The funds from Lillian Lincoln Howell supported travel and accommodation costs plus office costs. Overall, Edwards, Steptoe and Purdy achieved reasonable support for the programme of research, despite the initial rejection of funding by the Medical Research Council. However, this was at the expense of considerable inconvenience to Purdy and Edwards, and depended upon the good will of staff led by Muriel Harris in Oldham, who donated their time and expertise. As a result of our research, we conclude that, to Edwards, Steptoe and Purdy, should be added the names of two other hitherto neglected people who were essential to the success of this pioneering research: namely Muriel Harris and Lillian Lincoln Howell.

Keywords: Ford Foundation, IVF expenditure and grants, Lillian Lincoln Howell, Muriel Harris, Oldham and District General Hospital

Introduction

The birth of Louise Brown represented the outcome of nearly 10 years of work by Robert Edwards, Jean Purdy and Patrick Steptoe in Oldham and Cambridge (Elder and Johnson, 2015a, Elder and Johnson, 2015b, Elder and Johnson, 2015c, Johnson and Elder, 2015a, Johnson and Elder, 2015b). This work was attacked in the media (NF, Suppl. Material 1, pp. 6-7 in Johnson and Elder, 2015a) and by many eminent scientists and doctors (Perrutz in Anon, 1971a, Anon, 1971b; Watson in Anon, 1971c; Short in Johnson et al., 2010, p.2165–6) and indeed was considered to be so controversial medically, socially and ethically as to be denied funding by the Medical Research Council (MRC) of the UK for 10 years from 1972 (Johnson et al., 2010). In this paper, we examine the cost of this research and describe our investigations into the funding sources that covered these costs.

Materials and methods

The data were abstracted from notebooks and loose paper sheets and scraps, anonymized and analysed as described in Elder and Johnson (2015a), which also describes the archival sources used. Briefly, these include archives at Cambridge University (CUA) and at the National Archive (NA) plus papers among the possessions of the late Edwards and his late wife, Ruth Fowler Edwards, which have been kindly made available to us by their family (RGE). In-text references are indicated by the archive initials plus a reference number, and the details for each reference are recorded in the reference list. In addition, scientific papers and the volume A Matter of Life (Edwards and Steptoe, 1980) have been consulted, as described in Elder and Johnson (2015a).

We have also drawn on interviews with Grace McDonald (GM; for transcript see Suppl. Material 1 in Elder and Johnson, 2015b), John Webster [JW] and Noni Fallows [NF], and Sandra Corbett [SC] (transcripts of these interviews are provided as Supplementary Material 1, Supplementary Material 2 in Johnson and Elder, 2015a). In addition, we have used excerpts with permission from email exchanges with Virginia Papaioannou, Carol Readhead and Caroline Blackwell.

For comparison of monetary values of historic sums with today’s values, the web site http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/bills/article-1633409/Historic-inflation-calculator-value-money-changed-1900.html was consulted. Where comparisons are made over a period of 3–5 years, the average equivalent is given; for longer periods the start and finish range is given. For period dollar/pound conversions, http://www.measuringworth.com/ was used.

Results and discussion

After first exploring the sources of funding that supported the research, we then consider how this income was spent.

Funding

Unsuccessful applications for funding

We already know that the MRC refused funding in 1971 (Johnson et al., 2010), but papers in the Edwards archive add some information to that published earlier (Suppl. Material 1). In addition to the MRC’s refusal, letters to Dr Hannington of the the Wellcome Trust dated 27 October and 10 December 1970 also drew a blank and “no reasons were given” (RGE4, 1970).

Minor funding sources

Patients did not pay for treatment at Oldham, only for their transport to and from Oldham and any accommodation costs when not in the clinic (GM, p.19). However, some patients wished to contribute financial support for the work and this was paid into the Edwards and Steptoe Research Trust Fund, which was set up and registered as a charity in 1974 for this purpose. Edwards and Steptoe also donated fees earned from lectures etc. into this trust. The fund may have contributed some modest funds up to 1978, but the accounts are only available from 1985 (RGE5, 1974). Examination of the Cambridge University Reporter for the expenditure records listed under Physiology on external grants for the period 1961 to 1974 (after which such records no longer appear) reveals the presence of reproductive grants from various sources to the department. Although the names of the grant holders are not specified, it is possible for most grants to find this information from other sources (see names in Suppl. Material 2). Those to Edwards included three grants from the Wellcome Trust. Grant number 1234, (1970/1971 – 1973/1974), totalled £2,518 (= £31,378 at current values) supported his American graduate student, CWS Howe, who was working on the immunology of pregnancy (CUA1, 1972). A second grant, number 1563 (1972/73 – 1973/74) totalled £2827 (= £34,367 at current values) is likely to have been for Edwards, possibly jointly with RL Gardner, as VE Papaioannou is recorded as being paid from it (CUA1, 1972). The third grant, number 1509 (1972/73 – 1974/75) totalling £33,093 (= £354,808 at current values), employed C Readhead, then working on animal follicle development under Edwards (CUA1, 1972). None of these grants involved the human work, as likewise two other grants identified as being to H Pratt and to D Whittingham (CUA1, 1972 and Suppl. Material 2). Examination of the acknowledgements pages for papers published during and shortly after 1974 reveals one from 1976 that thanks the MRC (Faddy et al., 1976), probably referring to one of the two MRC project grants awarded to Edwards in the 1970s, entitled ‘The growth and differentiation of Graafian follicles in the ovary (rodents)’ (1975), although a request ‘to extend the study to human follicles was declined’ (the second being that awarded in 1976 to ‘Dr Edwards and [Azim] Surani for work on the cellular and molecular aspects of blastocyst–uterine interactions at implantation [rodents]’; NA1, 1978). The only grant listed that was likely to have been for Edwards and possibly involving human work, is from the World Health Organization (WHO), grant number 63 (1969/70-1972/73) totalling £15,018 (= £200,268 at current values) for ‘Studies on the genetics and embryology of early mammalian and human development’. However, the WHO is not thanked in any of Edwards’ papers, and we have not been able to find other references to it, so its possible use in the IVF work remains conjectural. Beyond these funding sources, only perhaps the last of which might have directly funded the human work, three major sources of support for that work have been identified.

Oldham and District General Hospital

Oldham and District General Hospital (ODGH) and/or the staff within it were supportive of the work, as is evident from the willingness of clinical staff to work for free at often very unsocial hours and on top of their daily routines (see below). The willingness of staff to ‘absorb’ many of the hormonal assay costs and to undertake all the necessary tasks involved in adapting Kershaw’s to its new role also indicates broad support within the hospital for their endeavour. It is clear from the interviews that much of this support came from a deep respect and affection among the staff for Steptoe himself. How ‘official’ the support was is unclear from documentary evidence, possibly because the MRC had put pressure on some hospitals to cease supporting the work (Johnson et al., 2010 p. 2167), although we have no direct evidence that such pressure was applied to ODGH. However, documentary evidence of financial support is available for 1978 (RGE6, 1978 – see below), which suggests that such a source had been made available for some time. It is clear that without this local support the work would have ceased. Indeed, Edwards and Steptoe thank the hospital and its staff as well as local regional boards for their support in 17 of the 23 (74%) papers published between 1969 and 1983 (shown in green in Suppl. Material 3).

The Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation support was crucial for the research effort. Thus, it provided a salary for Edwards first as a Ford Foundation research fellow from 1963 to 1969 (RGE7, 1967), then by an endowment of $240,000 made in 1968 (= £100,000) as the ad hominem Ford Foundation Reader in Physiology from 1969 – 1985 (CUA1, 1968). This endowment initially returned about £7000/year, sufficient to cover the cost of Edwards’ salary and overheads and to leave a surplus of about £2000 per year (RGE7, 1967). Edwards’ promotion resulted largely from the initiative of CR 'Bunny' Austin, according to a Cambridge University report, dated 21 May 1968 in which a paragraph reads:

The explanation of this item is that, with the encouragement of the Vice-Chancellor, Professor Matthews [then head of physiology] and Professor Austin applied to the Foundation for funds to support a Readership. They had no great expectation of success, but fortunately the Foundation have looked with favour on the application. (CUA2, 1968)

It also seems (CUA3, 1988) that the Ford Foundation endowment funded the ad hominem Chair in Human Reproduction, to which Edwards was appointed by the University between 1985 and 1989.

In addition to funding Edwards’ salary for up to 26 years, the Ford Foundation also provided a series of grants, the actual values of which are difficult to disentangle from the three sets of accounts available to us (Table 1a, Table 1b, Table 1c). Of these, the Cambridge University Reporter accounts (to 1974 only; Table 1a) and the Annual Reports of the Ford Foundation (Table 1b) are the most informative. An initial grant was awarded to Parkes for ‘Immunological approaches to fertility control’ totalling $130,000 (see Table 1b). This grant is recorded in the Reporter as being grant 28 for ‘Research in Reproductive Physiology’ (= £47,000 then, Table 1a; or £851,680 at current values) from the 18 July 1963 until 17 July 1967, the year in which Parkes retired and was replaced as head of the laboratory by Austin (Johnson, 2011). This grant was extended through an under-spend to 1968 (RGE7, 1967), and a new grant for the study of the ‘Early development of mammalian embryos’ of $313,000 (Table 1b) was awarded to Austin from 1968 to 1974. This grant comprised two components: (i) $73,000 to cover costs of equipment, supplies, travel, publication, and staff (we have evidence that in 1973 both Bavister and Gardner were supported by the Ford grant; CUA1, 1972), and (ii) $240,000 to endow the readership for Edwards (CUA2, 1968). This grant was evidently topped up with a further $245,000 for research expenses in 1970 (Table 1b). Thus the total equivalent in pounds sterling then of the two research components would be £29,000 + £98,200 = £127,200 (or a total of £1,758,880 at current values). Examination of Table 1a reveals expenditure from two grants over this period: number 58 (later renumbered 0784) for ‘Reproductive physiology’ totalling £30,051, and number 0791 for ‘Studies on embryonic development’ totalling £99,959. Thus, these two grants seem to represent the two tranches of dollar allocations recorded in the Ford Foundation Annual Reports (see above and Table 1b). The endowment income would not feature in the Reporter expenditure accounts.

Table 1a.

Data published in the Cambridge University Reporter on expenditure from Ford Foundation grants in physiology from 1962 to 1975, found under the index item ‘Research wholly or partly supported by funds from outside bodies’. No data was published in a suitable form after 1975.

| Academic financial year | Cambridge University Reporter reference (date, page) | Amount (£) | Grant title | Grant no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962–63 | 21 Oct 1964, 341 | 1836 | Reproductive physiology (1 person) | 28 |

| 1963–64 | 21 Jul 1965, 2225 | 10,320 | Reproductive physiology (3 persons) | 28 |

| 1964–65 | 3 Aug 1966, 2389 | 10,028 | Reproductive physiology (4 persons) | 28 |

| 1965–66 | 17 Aug 1967, 2127 | 8964 | Reproductive physiology (3 persons) | 28 |

| 1966–67 | 12 Jun 1968, 2212 | 10,734 | Reproductive physiology (2 persons) | 28 |

| 1967–68 | 13 Aug 1969, 2379 | 4970 | Reproductive physiology (2 research workers) | 28 |

| 1968–69 | 12 Aug 1970, 2474 | 850 | Reproductive physiology (2 research workers) | 28 |

| 13,100 |

Total for Grant 28 = £47,702 Reproductive physiology |

58 |

||

| 1969–70 | 11 Aug 1971, 1188–9 | 3838 | Reproductive physiology Total for Grant 58 = £16,938 |

58 |

| 1970–71 | 6 Dec 1972, 425–6 | 8065 | Reproductive physiology (2 assistants S) | 0784 |

| 10,639 | Studies on embryonic development (3 assistants: 1xS, 1xCBl, 1xHT) | 0791 | ||

| 1971–72 | 24 Oct 1973, 31 | 3140 | Reproductive physiology | 0784 |

| 22,975 | Studies on embryonic development | 0791 | ||

| 1972–73 | 7 Aug 1974, 31–2 | 1904 | Reproductive physiology Total for Grant 0784 = £13,113 |

0784 |

| 29,176 | Studies on embryonic development | 0791 | ||

| 1973–74 | 11 Nov 1975, 32–2 | 29,669 | Studies on embryonic development | 0791 |

| 1974-75 | 10 Nov 1976, 34–5 | 4 | Reproductive physiology | 0784 |

| 7500 | Studies on embryonic development Total for Grant 0791 = £99,959 |

0791 | ||

| 18,571 | Initiation and control of embryonic development Total for Grant 2188 = £18,571 |

2188 |

Table 1b.

Data published in the Ford Foundation annual reports on the value of grant allocations approved and the amount claimed as spent.

| Ford Foundation annual report reference (year; page) | Allocation approved ($) | Amount claimed in each year ($) |

Title of grant (where recorded) [Under- or over-spend] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963: 21, 27 1964:136 1965: 136 1966: 92 1967: 131 |

130,000 | 50,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 Total = 130,000 |

Immunological approaches to fertility control |

| 1968: 62, 136 | 313,000 | 0 | Early development of mammalian embryos |

| 1969: 150 1970: 76 1971: 82 1972: 78 1973: 78 1974: 58 |

245,000 |

278,209a 0 68,792 17,000 39,000 135,704 Total = 538,705 |

[19,295 remaining] |

| 1975–1976: 58, 59; 51 | 200,000 | 19,295 163,773 Total = 183,068 |

[16,932 remaining] |

| 1977: 45 | 45,000 | 36,337 | [8663 remaining] |

| 1978: 47, 54 | 223, 084 | 45,000 | [178,084 remaining] |

| 1979–1980: 54; 51 | 20,000 32,000 Total = 52,000 |

223,084 14,000 Total = 237,084 |

[185,084 overspent] Balance = 238,470 – 200,580 = 37,890 |

Includes $240.00 as an endowment to fund Edwards’ salary.

Table 1c.

Data from Ford Foundation archive reports on the grants awarded.

| Date | Amount ($) | Grant title | Grant no./reel no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 Jul 1963 –17 Jul 1968 | 30,000 | Research in reproductive physiology | 06300446/1280 |

| 17 Jan 1963 – 30 Sep 1981 | 928,000 | Center support for personnel | 06300110/5448 |

| 01 Apr 1978 – 31 Mar 1979 | 19,000 | Support to study an alternate pathway of formation of steroids in reproductive tissues | 07800352/4638 |

| 01 Oct 1978 – 30 Sep 1981 | 15,091 | Support of study for features of the fertilizing capacity of spermatozoa | 07800353/4648 |

| 01 Oct 1978 – 31 Dec 1984 | 92,540 | Support to analyze the nature of interactions between tissue components of the uterus/blastocyst during implantation in mice | 07800354/5148 |

| 01 Sep 1978 –31 Aug 1981 | 71,453 | Control mechanisms underlying embryonic differentiation in mouse embryos at time of implantationa | 07800355/4691 |

| 01 Oct 1979 – 30 Sep 1981 | 47,628 | Support of research on the surface antigens of human trophoblast | 07900664/5016 |

Awarded to MH Johnson in Anatomy, 1978–1981 for "Experimental Mammalian Embryology" ($75,000).

Inspection of the Ford Foundation Annual Reports indicates that further renewals of the grant took the support to 1980 (Table 1b) with further allocations totalling $520,084 (= £298,000), but evidence of this is not forthcoming from the Reporter, which ceased recording the grants from external sources from 1974 (Table 1b). The funding ceased after 1980, but evidently there was sufficient remaining from an under-spend of $37,890 to extend support from the grant to 1981 (Table 1b). Overall, the total amount provided by the Ford Foundation for the research amounted to $1,170,194 (= approximately £474,000 then, or £3,663,435–£5,155,111 at current values).

Thus the two sets of accounts recorded in Table 1a, Table 1b correspond reasonably where they are comparable, in contrast to the archives of the Ford Foundation (Table 1c), which use a system of grant numbers and names that do not correspond with either of the above sources and only give broad dollar allocations. However, the grants listed do total $1,203,712, which is only $33,518 more than the total of $1,170,194 recorded in the Annual Reports. Given that one grant (07800354) listed ran until 1984, it is possible that this was given additional funding perhaps via an allocation routed through the Population Council (Ford, 1980). Given this generous support, Edwards thanks the Ford Foundation in papers from 1964 to 1983 (shown in red in Suppl. Material 3).

On 13 August 1970, when Edwards and Steptoe were involved in their ultimately unsuccessful bid for MRC support (Johnson et al., 2010), Edwards wrote to Anna Southam at the Ford Foundation asking whether it might be prepared to support the clinical work in Cambridge (RGE8, 1970). Southam replied on 21 August saying “I do not believe that we could provide full support for Dr Steptoe” and saying that at a recent meeting of granting agencies at the WHO “Dr Malcolm Godfrey of MRC expressed great interest in improving departments of obstetrics and gynecology in Great Britain. Your first approach should be to him”. A reply from Edwards dated 30 August says that he is in contact with Sheila Howarth at MRC [Godfrey’s deputy, and less sympathetic to Edwards than Godfrey: Johnson et al., 2010], but that it seems unlikely that the MRC would cover any building costs, and is followed by a letter dated 23 October again asking about infrastructural support. No replies have been found.

It has been suggested that the Ford Foundation curtailed its support for research involving human embryo transfers, if not their creation, from 1973/4. Thus, a series of letters dated 12 and 26 May 1972 and January 1973 exchanged between Edwards and Richard Mahoney of the Ford Foundation (RGE9, 1972) indicate increasing alarm in New York about the ethics of the embryo transfer work, possibly triggered by the rejection of the MRC grant in 1971 (Johnson et al., 2010) and/or the increasingly hostile reaction to his work in the USA (Kass and Glass, 1971; Watson in Anon, 1971c). Thus, in a letter dated 12 May 1972, Mahoney expresses concern about reimplanting embryos and the impact that “the birth of a child who is not completely normal” would have “on both the child and on research in reproduction in general”. Then, probably in 1973/1974, there was a visit from the Ford Foundation head office, which elicited strong memories from those who were involved. Thus Readhead, then a graduate student in the laboratory, recalled:

One day, somewhere between 1972 and before I left for my PhD year in the States in 1974/1975, at least two and maybe three men in gray suits came to see Bob. They walked in to his office in an aggressive way and shut the door firmly. I remember this because I was sitting at my little table just outside his door and I had never seen men in suits in the lab before and also because no one ever shut Bob’s door. People popped in and out of his office all day long and there was always laughter. After what seemed like hours the men stalked out and left, and Bob emerged looking ashen. He said that things were not good, but was not explicit as he always sheltered his staff and students. Later we learned that the men were from the Ford Foundation and that they had stripped him of his funding right then and there. But this information was only via the grapevine. Whatever it was, it was not good and it must have been fairly precipitate otherwise why would they send men in suits?

And Papaioannou, then a post-doctoral worker in the laboratory, recalled:

It made me think back on a dinner with Bob and the lab … at the Garden House in Cambridge when the Ford Foundation came on a site visit and then said they were no longer funding us. We were all pretty tense at the dinner because we knew what was coming down. The date of the site visit and dinner I remember must have been 1974 or possibly early ‘75, before I moved to Oxford in '75. I only recall the dinner with Bob … but the rest is all guess work.

However, in correspondence with Mahoney (email to MHJ, 4 October 2010), he denies any memory of funding cuts on ethical grounds, but did say that at about that time the Foundation had to make savings. This assertion is confirmed by consultation of the Annual Report for 1974 (Ford, 1974), in which the President’s Review says:

In 1974 the Ford Foundation decided that a drastic reduction in its annual spending was necessary in order to conserve its long-term strength. We are now in the process of reducing our annual program budgets by about 50 per cent, to a level of $100 million a year. We want the reasons for this decision and the planned shape of our future programs to be clearly understood by all who are interested in our work.

Moreover, Ford Foundation support did continue beyond 1974 (with an allocation of $200,000 over the 2 years 1975 to 1976 and another of $45,000 in 1977; Table 1b), despite the Annual Report of 1975 (p.58) recording that “because of its own budget limitations”, the Foundation was scaling down support for reproductive physiology to focus on quality foreign centres including “research at University of Cambridge on the early development of mammalian embryos”. This support was renewed in 1978 (with allocations totalling approximately $255,00 to the year 1980; Table 1b), again despite further evidence of competitively based severe cuts to budgets (Ford, 1978):

Twenty-five grants totaling $1.5 million for research and training in the reproductive sciences went to universities and research laboratories in six countries (Argentina, Canada, England, Ireland, Thailand, and the United States). The awards, the latest in an international research competition that began in 1975, are supporting research on such subjects as the male reproductive system and the factors operating during pregnancy that prevent rejection of the fetus by the mother. Outside the United States funds for research in reproduction are relatively meager. This year, however, the medical research councils of several European countries issued a report urging increased attention to the reproductive sciences. They based their recommendations in part on a Foundation-commissioned review (Greep et al., 1976) of the state of reproductive and contraceptive knowledge.

However, no allocations were made from 1981 onwards, reflecting a change in policy announced in 1980 (Ford, 1980):

We continued to be active in almost all of the overseas settings in which we were operating before retrenchment. Now we need to complete the work of retrenchment by concentrating more selectively on needs and problems where we can expect to make a significant impact. (p. v)

and

A number of areas in which we have been strongly engaged are not now designated as major themes. Among these, three deserve brief comment: Population … we have decided to phase out a discrete program in population after some two decades of extensive support in this once neglected field. The decision comes at a time when other major funders have picked up responsibility for many large-scale projects. (p. x).

Finally, although a comparison of the funding levels before and after 1974 does reveal a fall from $668,705 to $501,489, in terms of pounds sterling it was broadly neutral, given the relative devaluation that the pound experienced over that time. Thus, the financial data offer little support for the belief that the Ford Foundation stopped funding the work after 1974. However, the possibility that it made clear to Edwards its unease about support for work involving transfer of embryos may be reflected in the reduced incidence of acknowledgements of the Foundation by Edwards post-1974 (5/11 or 45%; compared with pre-1975 citations of 20/20 or 100%), of which the only one that includes discussion of implantation of transferred embryos is Edwards and Steptoe (1983) by which time the technique had been ‘proved’ (Suppl. Material 3).

The American benefactress

Edwards thanked this unidentified benefactor in a paper in 1986 (Edwards, 1986, p.12), saying “The work would not have been possible without the generous benefaction of an American millionairess, who herself had suffered problems similar to those of the patients now being treated”. It is unclear from this reference whether the problem was hers or of a family member and whether it was one of infertility or of a genetic nature, although in the last pages (V and VI) of an undated letter from her to Edwards, reference is made to Edwards’ help in unspecified genetic matters (personal communication from CB).

However, the identity of this benefactress has been hitherto wreathed in mystery. This is curious because Edwards himself thanks her in the acknowledgements to 12/19 papers between 1971 and 1983, either indirectly as ‘the American Friends of Cambridge University’, or from 1974 onwards by name as ‘Lillian Howell’ or ‘Miss L Howells’ or ‘Miss Lillian Howells’ (in blue in Suppl. Material 3). This donor is further identified in papers from the University of Cambridge archives. Thus, between 1969 and 1970 (CUA4, 1969), a series of letters between variously Edwards, and RE Macpherson or TC Gardner of the Financial Board, and Professor Rhinelander and Dr Vining, the treasurers of the American Friends of Cambridge University refer to a grant (number 10-68) with an initial payment of $8000 (£3350 = £50,734 at current values) paid on 4 February 1969, and also recorded in the Treasurer’s report for 1968 (CUA5, 1968), plus a second of $17,000 paid on 2 February 1970; converted to £7,062, 6 shillings and 2 pence (letter of 24 February 1970: = £101,476 at current rates). These grants are described as being for “research activities concerning the alleviation of infertility and the control of fertility in animals and men: (i) travel connected with this research; (ii) training of medical personnel; (iii) purchase of research equipment; and (iv) hiring of additional research and clerical staff.”(Letter dated 10 February 1969). Letters dated 10 and 11 June 1969 authorise the employment of a part-time secretary from the grant (see also RGE10, 1969).

The origin of these funds is made clear in a letter from Edwards to Gardner (CUA4, 1969) dated 2 January 1970 referring to a phone conversation between himself and ‘Miss Howells’, which also indicates by 1970 they were in contact with each other. Then on 14 July 1970 (CUA6, 1970), a letter from Edwards to Gardner sets out the progress made in their work on IVF so far but says that before they move to embryo transfer they want to establish Steptoe in Cambridge. He then sets out their needs and the state of the (ultimately unsuccessful) negotiations with the hospital in Cambridge, and asks whether the American Friends of Cambridge University might be able to help? This letter evidently followed a visit to Cambridge by Dr Vining, to whom on the 15 July Gardner sent a copy of Edwards’ letter, which he was ‘expecting’. A letter, dated 20 July 1970, from Dr Vining to a Mr Berlin identifies the latter as representing Miss Howell and asks for her support for the work through a further $50,000, given that “she has been most generous in response to solicitations for our previous grant and has made it possible for Dr Edwards to make progress to the point where he is today”. Later that year, on 27 October 1970, Edwards wrote directly to Lillian Howell in California, saying that she has been supporting him in the past, and asks for continuing support, enclosing estimates for work required for conversions in Cambridge, and includes the comment “when your lawyer was here, I could not provide details of costs” (RGE11, 1970). On 27 April 1971, Edwards is informed by Gardner of a grant of $20,000 (£8180 = £110,465 at current values) from the American Friends of Cambridge University, acknowledged by Edwards on the 19 May, saying that he “will certainly write to Miss Howell to thank her personally” (CUA6, 1970). This grant is also referred to in the annual report of the American Friends of Cambridge University as Grant 71-2 (CUA7, 1971). A letter dated 18 January 1974 from Gardner to Edwards (RGE12, 1974) summarizes the Lillian Lincoln Foundation accounts as follows: 1972/73 – received $25,000 = £10,588, interest earned = £579; 1973/74 – received $25,000 = £11,445, interest earned = £1,205.00 [i.e. a total income over 2 years of £23,837 = £361,001 at current values]. In addition, we have evidence of expenditure from the grant (RGE13, 1978) as follows: 1974/1975 – £645.06; 1975/1976 – £2,336.72; 1976/1978 – 13,087.43 [i.e. a total of £16,169.21 = £129,233 at current values]. Interest earned was recorded as being £4,863.93.

It is unclear whether this expenditure reflects further payments or is paid from pre-existing funds. However, at the beginning of the 1976 period a total sum of £27,222.79 was recorded as being available, so it is probable that further donations had been received prior to 1976. Thus we have evidence that the Lillian Lincoln Foundation paid a minimum of $95,000 in total between 1969 and 1978 (= £39,700–£49,500). These various references, in addition to a direct reference to Lillian Lincoln in General Board papers relating to the Physiology Department (CUA8, 1972), allow the identification of the donor as Miss Lillian Lincoln Howell of California, an identity confirmed subsequently by Edwards’ two secretaries, Barbara Rankin and Caroline Blackwell, as well as by the late Ruth Edwards. An email from Miss Howell’s son (to MHJ from Lincoln C Howell, 2012) says “Mom's Foundation's charter directs funds toward video production [see below]. I believe she gave from her personal funds towards Dr Robert Edward's research.’, suggesting that the Foundation may have simply been the route through which her personal funds were channeled.

There is no evidence to indicate how Miss Howell came to know of Edwards’ work. However, given that the first grant was set up in 1968, and the first tranche of money from it arrived in the UK on the 4 February 1969, some 10 days before the Nature paper that first announced successful IVF, clearly, she was alerted to his work on oocyte maturation (Edwards, 1965) and/or his early proof of principle for PGD, which was published in 1967 and 1968 (Edwards and Gardner, 1967, Gardner and Edwards, 1968). Neither do we know how or when they first met. The letter from Edwards to TC Gardner of the Financial Board (CUA4, 1969) dated 2 January 1970 that refers to a phone conversation between himself and ‘Miss Howells’ indicates that by 1970 they were in contact with each other. According to his two secretaries and to the late Ruth Edwards, Edwards met her several times in the USA and the UK (including a visit to Bourn Hall), during which her son accompanied her on some visits as he recalls: “I saw a Jaguar [car] today that reminded me of the one he [Edwards] had while giving us tours.”(email to MHJ from Lincoln C Howell, March 2012). However, the only recorded contact, of which we have documentary evidence, was in two messages sent by fax in 2004: on the 11 August to arrange a meeting with her when in Washington DC on the 18 or 19 September and a second on the 3 September saying (Personal communication from Caroline Blackwell):

Dear Lillian

It was lovely speaking with you over the telephone and I look forward to our meeting again. I will bring some documents of interest.

I am writing to confirm our breakfast meeting on Thursday, 16 September at 9.00am at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel [McLean, Virginia, USA]. I will be waiting for you at Reception. …

Looking forward to seeing you there.

With my best wishes

Bob Edwards

Finally, Miss Howell shunned any publicity for her support, and both Edwards and his wife Ruth were adamant that this wish should be respected in her lifetime. However, her death on 31 August 2014 now legitimately allows us to reveal her identity.

Expenditure

The expenditure may be broken down into capital expenditure involved in setting up the facilities at Dr Kershaw’s Hospital; the labour costs for doctors and nurses; the salaries for the three principal investigators; the clinical costs of drugs, sterilization, hormone assays etc; the laboratory costs of making and testing media etc; office costs such as secretarial pay, telephones, and photo-copying; and the costs of travel between Cambridge and Oldham.

Set-up costs of the facilities at Dr Kershaw’s Hospital

We have found no documentary evidence relating directly to setup costs, but we do have evidence from the interview with Noni Fallows and John Webster (JW/NF, p.14):

| NF: | Back in 1969 £250 was a lot of money and that’s how much Patrick gave Muriel to set Kershaw’s up …. And I’m sure it was £250. It certainly wasn’t £500. And it certainly wasn’t in the thousands. It was £250 because I nearly fell off my chair when Muriel [Harris] told me. |

| JW: | What did she buy with that? |

| NF: | Well, this is where Fred Baxter [the hospital senior administrator] comes in. Fred Baxter had some old equipment in storage, not too old, usable, but we didn’t use it in main theatres … And, so, he had lights and a few trolleys, and patients’ trolleys, but Muriel was on something called the National Association of Theatre Nurses, and she was Chairperson of it. So all she had to do was get her feelers out and said, right, girls, I need a theatre table, and she bought one from Bolton. The theatre table came from Bolton …. And she had it serviced. Cracking. Just what we needed. And other bits and bobs used to surreptitiously find their way up to Kershaw’s. She got the joiner in to put the shelves in. But there was a small theatre at Kershaw’s anyway, and I think the GPs used it for minor ops, didn’t they? |

| JW: | I would imagine so, on occasion, but usually Kershaw’s was mainly used for respite care, wasn’t it, and people who were not seriously ill … bad chests and maybe just needed a bit of rest. |

| NF: | But there was a room there, all tiled, ready to go. All we needed is all the equipment. And that’s what’s happened. |

| JW: | I think she bought … the anaesthetic machine as well, didn’t she? |

| NF: | Yes. She bought the anaesthetic machine. Where that came from, I don’t know, but Muriel sorted all that out. |

| MJ: | So that was the setting up for £250? (= £3376 at current values) |

Clearly, Muriel Harris was committed to the project, as is emphasized even more in the following section.

Costs of doctors and nurses

Likewise, we have found no documentary evidence relating to these costs, for reasons that became clear in the interviews; thus Noni Fallows and John Webster (JW/NF, p.15; corroborated by Sandra Corbett – SC, p.7):

| MJ: | And then the running costs? I mean how were you paid and so on? |

| NF: | We weren’t paid. |

| MJ: | You weren’t paid? |

| NF: | No. |

| MJ: | You did it all voluntarily? |

| NF: | Yes. |

| MJ: | All of you? |

| NF: | All… yes. |

| MJ: | And you as well [to John Webster]? |

| JW: | Promises, but no money … [to NF] I think you used to get a fiver now and again, didn’t you? |

| NF: | Well, that’s what I’m just coming to. When we started doing egg collections without the drugs, without the hormones, it was lunacy. And, anyway, as per usual Saturday morning with Muriel, Sandra and myself, and we finished the magic egg collection, I mean we’d been at it all week, two and three cases a day, but, you know yourself it comes up 11 o’clock at night, 2 o’clock in the morning. We had to be back at work for 8 o’clock in the morning, so we could have finished Kershaw’s at two in the morning and we were back on duty again at eight in the morning. It was lunacy, but we enjoyed it. And this particular Saturday morning Muriel comes up to me and gives me £10. And I said, what’s that for? She said, oh, Father [Steptoe] just given it me for you. I said, what for? She said, the work. I said, there’s no money. She… I said, give it to him back. She said, I can’t give it to him back. I… there’s no money. She said, I can’t give it to him. Take it. For God’s sake, take it. Yes. Right. Okay. So every now and then on a Saturday morning we had £10 (circa £60 at current values). |

Salaries for Purdy, Edwards and Steptoe

Edwards was paid by Cambridge University from grants from the Ford Foundation (see above). Thus, Edwards was appointed Ford Foundation Research Fellow from 1963 on a grant initially to Professor Sir Alan Parkes (Polge, 2006), who had been appointed to the Mary Marshall and Arthur Walton chair of reproductive physiology in 1961, having previously recruited Edwards to work at the MRC National Institute for Medical Research, Mill Hill (Johnson, 2011). Purdy was also presumably employed on this grant, although no record has been found of her employment contract. Steptoe was a salaried NHS consultant who also had a private practice. Both Edwards and Steptoe also undertook lectures for which they sometimes received fees, and in 1974 they set up the charitable trust fund into which they put these fees as well as donations from patients. However, we lack the accounts for that period and so do not know what was paid out from this fund.

Clinical costs

Urinary oestrogen assays, and possibly some other hormonal assays, were evidently performed by Searle Scientific services free of charge, as evidenced by the thanks in the Acknowledgements sections in many papers from 1970 to 1980 (purple in Suppl. Material 3). However, most of the clinical costs were evidently covered by Oldham Area Health Authority. This information was only uncovered obliquely via a set of handwritten accounts for the Lillian Lincoln Foundation grant made to Edwards via the American Friends of Cambridge University. Thus, these accounts for the period 14 September 1976 to midsummer 1978 record a total expenditure of £13,087.43 (= £83,472 at current values), of which £1,993 (= £12,711 at current values) is on clinical supplies. However, a set of handwritten calculations and typed costings (RGE6, 1978), the latter dated 20 June 1978, records expenditure on clinical costs between 1 January 1977 and some time after March 1978, which totals £1263.41 (= £7,942 at current values). This sum, having been paid from the ‘research fund, Cambr. Univ.’ (presumptively the Lillian Lincoln Howell money), is being reclaimed from Oldham Area Health Authority. The accompanying correspondence (RGE5, 1978) indicates that all or most of clinical costs had usually been borne locally in the same way.

Laboratory costs

The basic laboratory costs in Cambridge were evidently covered from Ford Foundation grants.

Office costs

Such evidence as is available suggests that the office costs were borne from the Lillian Lincoln Howell funds. Thus permission was given for the employment of Edwards’ part-time secretary, Barbara Rankin, on this fund in 1969 (RGE10, 1969), and these funds were used to cover office costs of £2350.52 (= £14,998 at current values) incurred in Oldham between 1976 and 1978 (RGE6, 1978).

Costs of travel between Cambridge and Oldham

Examples of the actual costs of travelling between Cambridge and Oldham, and of staying in Oldham, in the 1970s, show that on 27 June 1975, three single train fares are costed at £5.58 (= £50.77 at current values), and claims are made for 58 coffees totalling £1.16 (= £10.55 at current values), 48 lunches totalling £9.60 (= £87.35 at current values), 38 teas totalling £1.14 (= £10.37 at current values), two dinners totalling 40p (= £3.64 at current values), and 29 nights’ accommodation totalling £15.10 (= £137.39 at current values). Likewise, for September 1976, the claim is for a per diem charge of £4.00 each (= £29.30 at current values). For many of the trips by road, cars were hired from Godfrey Davis or Hertz (which charged £2 extra for delivery). Suppl. Material 4 summarizes the notes recorded on the travel information described in Johnson and Elder (2015b).

Table 2 includes summaries of the claims for various classes of expenditure related to travel for the period 1976–1978. Most of these latter travel costs appear to have been met from the Lillian Lincoln Howell grant. Thus, statements of expenditure from this account between 14 September 1976 and mid-1978 list Godfrey Davis and travel expenses for Purdy and Edwards amounting to £11,094.27 (= £141,520 at current values).

Table 2.

Summary of the record of expenditure on the Lillian Lincoln Fund grant to Edwards, September 1976 to mid-1978.

| Category of expenditure | No. of items listed | Amount (£) | Items included |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical supplies | 63 | 1993.24 | Gases, culture media components, surgical needles, paraffin oil, Millipore filters, irradiated products (for sterilization), tissue culture dishes, Pasteur pipettes, aspirator parts, Hi-Gonavis kits, laminar flow hood maintenance |

| Office materials | 16 | 2350.52 | Telephone and photocopier charges, postage |

| Travel Edwards | 12 | 1570.31 | |

| Travel Purdy | 9 | 619.21 | |

| Expenses others | 2 | 76.98 | FB Baillie and Ester Jones |

| Car hire | 24 | 3069.42 | Mostly Godfrey Davies, but also Willhire, and Cambridge Car and Van Hire |

| Board and accommodation | 4 | 3407.83 | |

| Total = 13,087.51 |

General discussion

It is possible through the incomplete documentation discovered to demonstrate that Edwards and Steptoe, despite not being funded by the MRC, did manage to cover the costs of their research through a patchwork of funds combined with a lot of goodwill from GD Searle and from the local hospital boards and staff. In total, over the period from 1969 to mid-1978 we have calculated a range of £130,000–£245,000 (or £13,690–£25,871 per year) available to Edwards, Steptoe and Purdy (Table 3). This compares with Edwards and Steptoe’s bid to the MRC in 1971 for a five-year programme at £50,000 (or £10,000 per year; Johnson et al., 2010, p. 2167). Thus, even though the MRC grant was probably an underestimate and working in Oldham imposed additional costs, the funding achieved was reasonable. Undoubtedly, the three main sources of support were the local hospital boards, the Ford Foundation and Miss Lillian Lincoln Howell.

Table 3.

Total value of research funds identified as being available to Edwards, Steptoe and Purdy between 1969 and mid-1978 at contemporary rates.

| Source | Minimum amount available (£) | Notes | Estimated maximum amount available (£) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Foundation | 94,800 | 20% of grant expenditure | 189,600 | 40% of grant expenditure |

| WHO | 0 | 15,018 | ||

| Lillian Lincoln Howell | 34,000 | From $95,000 | 34,000 | |

| ODGH | 1,263 | Supplies for 1.5 years | 7,157 | Extrapolated over 8.5 years |

| Total | 130,063 | 245,775 | ||

| Average/year | 13,690 | 25,871 |

ODGH = Oldham and District General Hospital; WHO = World Health Organisation.

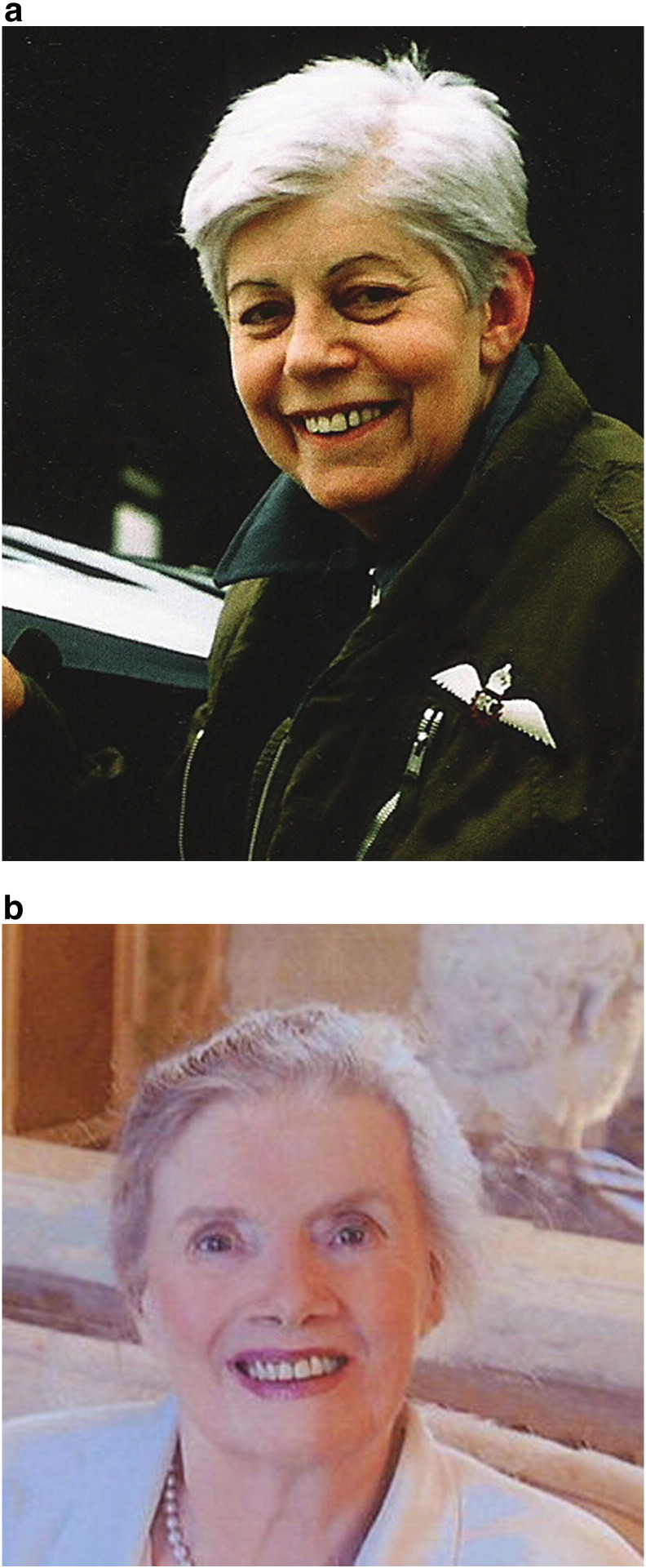

The moral and financial support of the local Oldham hospital boards and staff was clearly essential for the successful completion of the project. It took particular courage for the administrative staff in Oldham to support the work when the views of both the MRC, and by inference the DHSS, were so negative. It is an indication of the high regard in which Patrick Steptoe was held that the boards were prepared to stick with him for the 9 years. Special mention must be made of the dedicated work of Muriel Harris and her team, which like Purdy’s role (Johnson and Elder, 2015b), has been under-appreciated. Muriel Harris (Figure 1a) was born in Swinton on 4 June 1923, educated at Pendleton High School for Girls, and studied at Manchester University, where she gained a BSc in Physics, Chemistry and Biology. She then studied from 1942 at the London Hospital during the London ‘blitz’ of World War II to become a State Registered Nurse. In 1968 she joined Steptoe as operating theatre superintendant at Oldham, where she equipped the Kershaw’s operating theatre on a shoe-string budget and raised and organized a team of ‘volunteer’ nursing staff in Oldham. In 1980, she moved to Bourn Hall as Matron in Charge. There she was instrumental in setting up the successful clinical programme by establishing operating theatre facilities and wards in portakabin units. After retiring from the Clinic, she gained her Private Pilot License and helped to establish the flying school at Bourn, and flew light planes until she was 80 years of age. She died on 14 December 2007 aged 84 and was cremated in Cambridge followed by a service at Bourn Church (where Steptoe is buried) at which Edwards gave the eulogy.

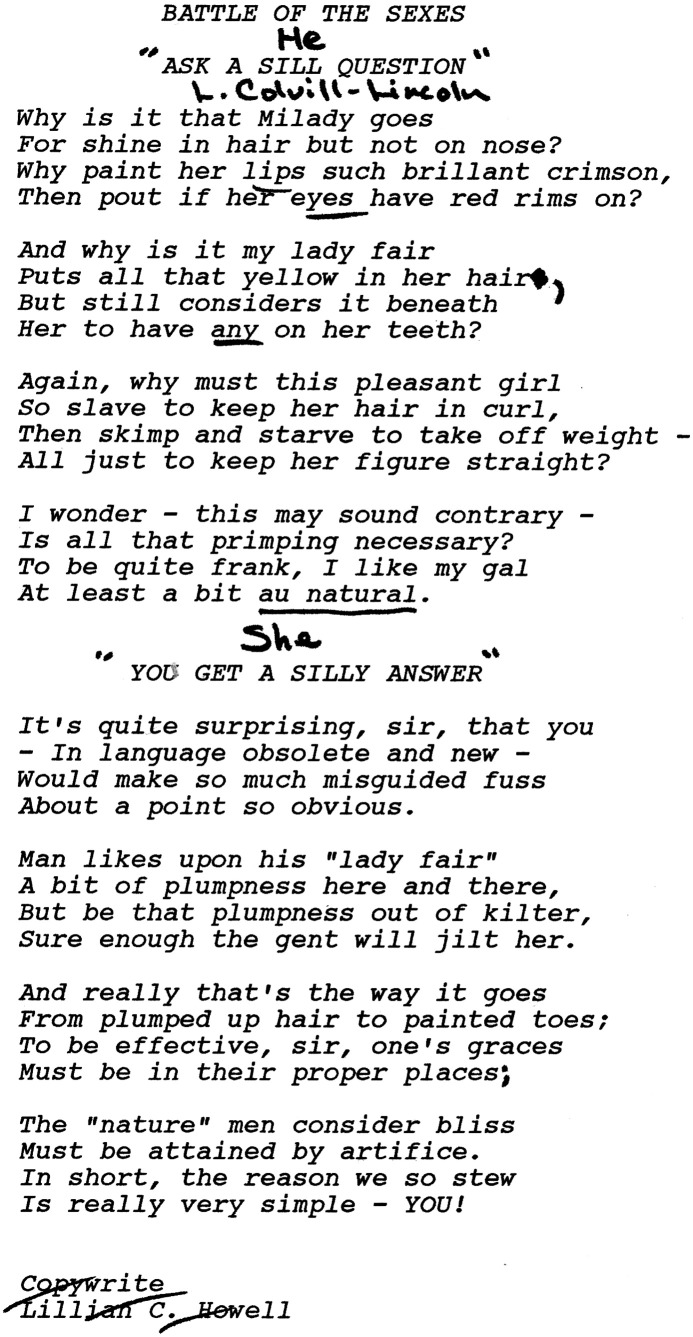

Figure 1.

(a) Muriel Harris (courtesy of John Fallows, who has copyright), and (b) Lillian Lincoln Howell (from her obituary at http://hosting-19478.tributes.com/obituary/show/Lillian-Lincoln-Howell-101686506).

The role of the Ford Foundation in financially supporting efforts to control fertility is well known, although more usually associated with the development and application of contraceptive methods for controlling population growth than the treatment of infertility (Connelly, 2008, Greep et al., 1976). However, aside from anecdotal evidence of a serious ‘wobble’ in 1974, understandable in light of the adverse press that the work had generated in the USA, the Ford Foundation did stand by Edwards to the end, again a tribute to their vision.

The novel information we have uncovered relates to Lillian Lincoln Howell (1921–2014; Obituaries, 2014; Figure 1b), on whom we provide some background. Miss Howell was born in 1921 in Cleveland Ohio, the eldest of three children with younger brothers Joseph (b. 1923) and David (b. 1926). Her parents were John C (1867–1959) and Helen C (1892–1994) Lincoln. Her father, John Cromwell Lincoln, also the eldest of three, was a self-made man, born of an itinerant pastor originally from England (Love, 2011). In Cleveland, he set up a garage business and founded the Lincoln Electric Company of Cleveland, Ohio in 1895, eventually acquiring 54 patents ranging from electric brakes for street-railway cars to variable-speed electric motors. His arc-welding innovations (http://www.lincolnelectric.com/en-us/Pages/default.aspx) are described as having transformed many industries and were critical to America's war efforts. In 1931, her mother, Helen (1892–1994), who was formerly a schoolteacher, had developed such severe tuberculosis that the family moved to the drier air of Arizona, where she raised a herd of prize goats, living to the age of 103. There her husband became affiliated with Arizona copper interests and founded the Bagdad Copper Co. (Love, 2011). He was also a real estate investor and the author of several monographs and books, particularly on land and land taxation. These interests led him to found the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, which focuses on smart growth and community planning, and of which in 2011 Lillian was an emeritus board member (http://www.lincolninst.edu/aboutlincoln/board_directors.asp). In Arizona, he also founded the John C Lincoln Hospitals (which developed from his support for the Desert Mission, an organisation that cared for families moving to Phoenix for relief of their respiratory conditions: http://www.desertmission.com/about/), funded in large part the Phoenix YMCA building, as well as founding the Camelback Inn Resort and Spa in Scottsdale Arizona (Hua, 2006), and set up a charitable trust, the Lincoln Foundation, “for the purpose of teaching, expounding and propagating the ideas of Henry George” (a nineteenth-century American economist and social philosopher who propounded a “Single Tax” theory that proposes that all taxes be abolished except a tax on the community produced ground rent of land; http://www.henrygeorgefoundation.org/).

Lillian Lincoln attended Pomona College, California, between 1939 and 1943, where she studied science and philosophy and enrolled in a variety of courses, including psychology. After graduating, she taught preschool in California, worked as a recreational director in a disabled children's home in Phoenix, and married her first husband, Carl Howell, with whom she had her only son, Lincoln C Howell, in South Pasadena. The couple separated in 1957, and she later married Deane De Vere Banta, a media executive: together they bought the license for KTSF TV, and after their divorce, she kept the station as part of the settlement.

Lillian Lincoln Howell continued the philanthropic tradition of her father. Thus, in 1965, she was awarded a license to operate channel 26 in San Francisco, but it was 11 years before broadcasts began on 4 September 1976 as KTSF TV, and this formed one of her main business and philanthropic interests. KTSF, which is owned by the Lincoln Broadcasting Company, was one of the nation’s first multi-ethnic stations, broadcasting news and entertainment in 12 languages to an audience of about 1.4 million. Initially broadcasting in Cantonese and Japanese, Filipino transmission was added in 1982, Vietnamese in 1985, Mandarin in 1991, and Hindi by the late 1990s. The business has a strong charitable aspect to it, and did not return a profit until 1986. Thus, throughout its history, KTSF has promoted Asian community activities, providing airtime for fund-raising and providing funds itself. In June of 2010, KTSF 26 Chinese News was one of three awardees of the Consumer Action award “to honor organizations and who have made significant achievements on behalf of consumer rights and protections” (Sherry, 2010). Lillian Lincoln Howell said in September 2006 (Hua, 2006): "My motto at the time was to serve the underserved. I really wanted to do something that would help the community. I wasn't interested in the money it might generate. We worked hard to keep the station alive, and I've never been sorry for the effort."

In an additional act of generosity in 2005 she donated $10 million towards the total construction cost of $40 million to her alma mater for two new academic buildings to house a range of programmes involving the study of the mind and brain (Anon, 2005). One building is named the Lincoln Building, to honor Howells’ family, including her father and her son. The other building is named the Edmunds Building in honor of Charles K Edmunds, the fifth president of Pomona College, as gratitude for his support during her first years at College. She is quoted as saying (Anon, 2005): “Over the years, new fields of study have emerged, including neuroscience and cognitive science, that are of immense interest to me. With the new buildings, all programs at Pomona involving the science of the mind will be located together. It will be very exciting.” The buildings opened in January 2007, and provide 92,000 square feet of space, housing Computer Science, Environmental Analysis, Linguistics and Cognitive Science, Geology, Neuroscience, Psychology, and three intercollegiate departments — Asian American Studies, Black Studies and Chicano Studies.

In 1985, she established the Lillian Lincoln Charitable Foundation, which is registered in Arizona and which was IRS-approved as a private tax-exempt organization, and which filed a tax return indicating assets of $3,127,253.00 on 28 February 2012. In this return, Howell is described as Chief Executive Officer and one of three directors with brother David and son Lincoln (http://990s.foundationcenter.org/990pf_pdf_archive/942/942943599/942943599_201202_990PF.pdf). The Foundation funds documentaries on topics of interest to Lillian Lincoln, including agricultural land reform in Taiwan, and ombudsmen. Films copyrighted to the Foundation include: A Dream in Hanoi, a documentary film by Tom Weidlinger that follows a cross-cultural theatre project in Vietnam; Heart of the Congo by Bullfrog Films, described as being "A clear-eyed examination of humanitarian aid in action"; Videos on Ageing, and Children as the Peacemakers.

David, her youngest brother, described her as: "a very gentle person. But she can also be a bit stubborn. She likes to promote women's rights, but she's not out pounding the pavement." She is described by work colleagues as having “an open mind about a lot of things. Racy was one thing, but if there was abusiveness to women [in the movies], she went ballistic…”, and as being “thrifty, with no flashy car, no fancy clothes” (Hua, 2006). Community activist Rosalyn Koo described (in Hua, 2006) how she first met Howell at a political fundraiser in Chinatown.

"I asked, what do you do, and she said something about the station," says Koo, 78. "Do you work in the programming department?' I asked, and she kind of smiled. She didn't say she owned the station. She's a very modest person. The two of us are kindred spirits, because we value the same kind of things … We don't take anything for granted, and we don't suffer any nonsense."

She also wrote verse displaying a gentle sense of humour (Figure 2) and collected eighteenth-century European antiques for her 1914 mansion in Hillsborough with its extensive rose gardens (Hua, 2006).

Figure 2.

Verses penned by Lillian Lincoln Howell.

In addition to supporting Edwards’ work, she also supported the research by Dr Emmet Lamb (lately an emeritus member of Stanford’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology; email to MHJ from Lincoln C Howell, March 2011), as well as actively supporting the state legislation bills (SB322, SB771 and SB778) that would set up a specific framework for enhancing stem-cell research in the state of California: “The benefits of stem-cell research have recently been articulated in a variety of rational forums and symposiums. Distinguished American medical researchers … suggest that, simply put, generating new sources of human stem cells will assist us in determining if the bad cells causing Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, type-1 diabetes, spinal cord injuries and breast cancer can be replaced by healthy ones. How can we not pursue the possible cures for illnesses that have so troubled humankind? If we had followed the argument of some, we would not have sought the cures for tuberculosis, smallpox and cancer plaguing our population for generations.” (Howell, 2003).

It is of interest that two of the major breakthroughs in reproductive medicine in the twentieth century were both facilitated by enlightened financial support from wealthy strong-minded women: IVF by Lillian Lincoln Howell and the contraceptive pill by Katherine McCormick (Connelly, 2008, p.174–5). Indeed, our research leads us to propose that to the names of Edwards and Steptoe should now be added the names of three hitherto under-appreciated, and now alas also deceased, women, who were crucial to the success of IVF namely: Jean Purdy, Muriel Harris and Lillian Lincoln Howell.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Some additional information concerning the unsuccessful application for funding to the Medical Research Council (Johnson et al., 2010).

Cambridge University Reporter data for yearly expenditure on grants to the Department of Physiology found under index item ‘Research wholly or partly supported by funds from outside bodies’ between 1961 and 1974 (excluding those from the Ford Foundation - see Table 1a).

Copies of informative acknowledgements from papers by Edwards (1964 – 1983), colour-coded according to the funding body thanked.

Summary of the notes recorded on the travel information described in Johnson and Elder (2015b).

Acknowledgements

We thank Barbara Rankin, Ginny Papaioannou, Carol Readhead, Lincoln C Howell, Noni Fallows and Caroline Blackwell for their advice and help; Dmitriy Myelnikov for his research assistance; and the Syndics of Cambridge University Library for permission to cite the University of Cambridge Archives held in the University library. The research was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (088708, 094985 and 100606), which otherwise had no involvement in the research or its publication.

Biography

Martin H Johnson FRCOG, FMedSci, FRS is Emeritus University Professor of Reproductive Sciences and fellow of Christ’s College, Cambridge, and Honorary Academic Fellow of St Paul's College, Sydney University. In 2014 he was awarded the Marshall medal by the Society for Reproduction and Fertility, and was elected an Honorary Member of the Physiological Society. He is author of Essential Reproduction (seventh edition, Wiley Blackwell, January 2013), co-editor of Sexuality Repositioned (2004), Death Rites and Rights (2007) and Birth Rites and Rights (2011), and has authored over 300 papers on reproductive and developmental science, history, ethics, law and medical education.

Contributor Information

Martin H. Johnson, Email: mhj21@cam.ac.uk.

Kay Elder, Email: kay.elder@bourn-hall.com.

References

- Anon, 1971a. Scientist warns on test-tube babies research. Cambridge Evening News, 19th October, pp. 11.

- Anon, 1971b. Deformity fears over test-tube babies. The Times, 20th October, pp. 2.

- Anon, 1971c. Test-tube baby work likely to go on despite U.S. criticisms. Cambridge Evening News 18th October, pp. 10.

- Anon, 2005. Alumna Donates Largest Single Gift of $10 Million. Pomona Online, Spring 2005 volume 41, no. 2 at http://www.pomona.edu/Magazine/PCMsp05/DEtommorrow3.shtml.

- Connelly M. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, USA: 2008. Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population. [Google Scholar]

- CUA1, 1972. Records of amounts paid to: CWS Howe from Wellcome Trust grant no. 1234; to VE Papaioannou from Wellcome Trust grant no. 1563; to CW Readhead from Wellcome Trust grant no. 1509; to H Pratt from the Sybil Eastwood Memorial Trust grant no.1506; to BD Bavister and RL Gardner from Ford Foundation grant no. 0791; and to DG Whittingham from MRC grant no. 1054. GB 502 Box 702. Research assistant stipends 1968-75.

- CUA2, 1968. Letter to D Kellaway (Secretary of the Faculty Board of Biology B) from RF Holmes (senior Assistant at the Registrary) refers to Fac Biol B meeting minute of 12 Feb 1968 and a successful application to Ford Foundation for a five-year grant from CR Austin. Grant awarded totaled $313,000 made up of Technical salaries $14,835; Equipment including maintenance $18,165; Supplies $30,000; Travel $5,000; Publication costs $5,000; Endowment $240,000. Various General Board minutes dated 23rd October, 20th November, 15th January, and 12th February refer to the setting up of the readership. GB 731.020. Box 1264. Physiology (inc. Rockefeller and Ford) 1928-1988.

- CUA3, 1988. Letters dated 6th and 7th September between PCN Vaugon (Deputy Secretary General) and Jeremy F Howe (Deputy Treasurer) concerning a deficit of £36,470 on Ford Physiology Fund, enquiring whether it was OK to incur a rising deficit until RGE retires (due 1992) and then recoup, and asking whether Keynes [then head of Physiology] had approached the Ford Foundation about obtaining additional capital, as he had been intending to? GB 731.020: Box 1264. Physiology (inc. Rockefeller and Ford) 1928-1988.

- CUA4 . 1969. Letters dated 4th, 10th February and 10th, 11th June 1969, and 2nd January, 2nd, 11th, 13th, 24th February, 4th March 1970 concerning funding of Edwards’ work by the American Friends of Cambridge University. (FB 40/O-P) [Google Scholar]

- CUA5 . 1968. The Treasurer’s report of the American Friends of Cambridge University for period ending December 31 1968. “Statements of Grants”. (UA DEVT. D1/5) [Google Scholar]

- CUA6 . 1970. Letters dated 14th, 15th, 21st July 1970 and 27th April, 19th May 1971 concerning renewal of funding of Edwards’ work by the American Friends of Cambridge University. (FB 40/O-P) [Google Scholar]

- CUA7 . Funded grants, 1971”. (72) 149. 1971. The Treasurer’s fourth report of the American Friends of Cambridge University for 1971; p. 4. (FB). (UA DEVT. D1/5) [Google Scholar]

- CUA8 . 1972. General Board reference to Lillian Lincoln in papers on the Physiology Department. (GB 501.080 Box 1264) [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R.G. Maturation in vitro of human ovarian oocytes. Lancet. 1965;ii:926. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(65)92903-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R.G. Royal Society symposium: ethical limits of scientific research. Royal Society and the American Philosophical Society; 1986. Ethics of human conception in vitro. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R.G., Gardner R.L. Sexing of live rabbit blastocysts. Nature. 1967;214:576–577. doi: 10.1038/214576a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R.G., Steptoe P.C. Hutchinson; London: 1980. A Matter of Life. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R.G., Steptoe P.C. Current status of in-vitro fertilization and implantation of human embryos. Lancet. 1983;322:1265–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder K., Johnson M.H. The Oldham Notebooks: an analysis of the development of IVF 1969-1978. I. Introduction, Materials and Methods. Reprod. BioMed. Soc. 2015;1:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder K., Johnson M.H. The Oldham Notebooks: an analysis of the development of IVF 1969-1978. I!. The treatment cycles and their outcomes. Reprod. BioMed. Soc. 2015;1:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder K., Johnson M.H. The Oldham Notebooks: an analysis of the development of IVF 1969-1978. III. Variations in procedures. Reprod. BioMed. Soc. 2015;1:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faddy M.J., Jones E.C., Edwards R.G. An analytical model for ovarian follicle dynamics. J. Exp. Zool. 1976;197:173–185. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401970203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford . President’s Review. 1974. Ford Foundation Annual Report for 1974; p. i. [Google Scholar]

- Ford . Reproductive Science. 1978. Ford Foundation Annual Report for 1978; p. p.48. [Google Scholar]

- Ford . President’s Review. 1980. Ford Foundation Annual Report for 1980. (pps. v and x) [Google Scholar]

- Gardner R.L., Edwards R.G. Control of the sex ratio at full term in the rabbit by transferring sexed blastocysts. Nature. 1968;218:346–348. doi: 10.1038/218346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greep R.O., Koblinsky M.A., Jaffe F.S. MIT Press; Cambridge. Mass: 1976. Reproduction and Human Welfare: A Challenge to Research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, L.L., 2003. Legislative Priorities California can send a message on stem cells. San Francisco Chronicle, Page A-23 April 22nd, and at http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2003/04/22/ED137939.DTL.

- Hua V. In SFgate September 2nd 2006. 2006. http://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/KTSF-celebrates-30-years-serving-Asian-melting-pot-2470270.php at.

- Johnson M.H. Robert Edwards: the path to IVF. Reprod. BioMed. Online. 2011;23:245–262. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.H., Elder K. The Oldham Notebooks: an analysis of the development of IVF 1969-1978. IV. Ethical aspects. Reprod. BioMed. Soc. 2015;1:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.H., Elder K. The Oldham Notebooks: an analysis of the development of IVF 1969-1978. V. The role of Jean Purdy reassessed. Reprod. BioMed. Soc. 2015;1:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.H., Franklin S.B., Cottingham M., Hopwood N. Why the Medical Research Council refused Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe support for research on human conception in 1971. Hum. Reprod. 2010;25:2157–2174. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass L.R., Glass B. What price the perfect baby? Science. 1971;173:103–104. doi: 10.1126/science.173.3992.103-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love S. David and Joan Lincoln and Lilllian Lincoln Howell donate $4 million. 2011. http://www.arizonafoothillsmagazine.com/features/health/2729-david-and-joan-lincoln-and-lillian-lincoln-howell-donate-4-million.html at.

- NA1 . 1978. Grants to Edwards in S. Ramaswamy, summary of Council policy on IVF, 28 July 1978. (FD 10/161) [Google Scholar]

- Obituaries Lillian Lincoln Howell. 2014. http://www.tvnewscheck.com/article/78994/ktsf-owner-lillian-lincoln-howell-dies-at-93http://www.sfexaminer.com/sanfrancisco/ktsf-owner-lillian-lincoln-howell-who-steered-programming-toward-diverse-languages-dies/Content?oid=2896805http://hosting-19478.tributes.com/obituary/show/Lillian-Lincoln-Howell-101686506

- Polge C. Sir Alan Sterling Parkes 10 September 1900–17 July 1990. Biogr. Mems Fell. R. Soc. 2006;52:263–283. doi: 10.1098/rsbm.2006.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RGE4 . 1970. Letters from Edwards to Dr Hannington of the Wellcome Trust dated 27th October and 10th December 1970 asking about support. (Not yet filed) [Google Scholar]

- RGE5 . 1974. Papers from the Edwards and Steptoe Trust fund, including the original deeds and accounts from 1985. (Not yet filed) [Google Scholar]

- RGE6, 1978. Materials involved in reclaiming, from Oldham Area Health Authority, clinical expenses from the Lillian Lincoln Fund grant to Edwards, including correspondence between Edwards and TC Gardner of Financial Board (12th May), TF Harrison, Area Treasurer at Oldham Area Health Authority and Mrs Havercamp, accountant at Physiology (9th June, reply on 29th June), and a letter of thanks from Edwards to Harrison for their support (8th August). Patient Matters Box 3 and General letters, Folder 75.

- RGE7, 1967. Letter dated 3rd November 1967 from Dr AL Southam (Ford Foundation) to AS Parkes explaining that permission must be requested to use the money left in the grant to AS Parkes to extend Edwards’ fellowship to the summer of 1968, and a reply on 8th November 1967 from Edwards saying that the grant application from CR Austin had been submitted, and requesting permission. Plus a letter dated 20th December 1968 to Edwards from GS Hankinson at the Old Schools explaining the likely investment return of the Ford endowment. Not yet filed.

- RGE8 . 1970. Exchange of letters between Anna Southam of Ford Foundation and Edwards dated 13th, 21st and 30th August and 23rd October concerning support for Steptoe in Cambridge. (Not yet filed) [Google Scholar]

- RGE9 . 1972. Letters between Edwards and R.T. Mahoney, 12 and 26 May 1972, 8 January 1973. (Not yet filed) [Google Scholar]

- RGE10 . General letters Folder 38. 1969. 10th June letters re funding for part time secretary from American Friends. [Google Scholar]

- RGE11 . 1970. Letter from Edwards to Miss Lillian Howells dated 27 October 1970. [Google Scholar]

- RGE12 . 1974. Letter from CU Treasurer Mr TC Gardner to Edwards dated 18th January 1974. (Not yet filed) [Google Scholar]

- RGE13 . Patient Matters Box 3. 1978. Hand written accounts recording expenditure on the Lillian Lincoln Fund grant to Edwards from 14th September 1976 to mid-1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sherry L. Consumer Action Anniversary and Awards. 2010. http://www.consumeraction.org/press/articles/consumer_action_anniversary_and_awards/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Some additional information concerning the unsuccessful application for funding to the Medical Research Council (Johnson et al., 2010).

Cambridge University Reporter data for yearly expenditure on grants to the Department of Physiology found under index item ‘Research wholly or partly supported by funds from outside bodies’ between 1961 and 1974 (excluding those from the Ford Foundation - see Table 1a).

Copies of informative acknowledgements from papers by Edwards (1964 – 1983), colour-coded according to the funding body thanked.

Summary of the notes recorded on the travel information described in Johnson and Elder (2015b).